Findings from the Field: Medicaid Delivery Systems and Access to Care in Four States in Year Three of the ACA

Executive Summary

With three years of expanded coverage under the ACA in place, many states have shifted focus from outreach and enrollment to strengthening delivery systems and enhancing access to care to meet the needs of their growing covered populations. Based on case studies and focus groups, this brief reviews delivery systems and access to care for Medicaid enrollees in Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, and Washington as of Spring 2016. Each of these states expanded Medicaid and experienced large gains in Medicaid enrollment. The findings provide an on-the-ground view of Medicaid delivery systems and enrollees’ experiences accessing care three years after implementation of the Medicaid expansion. This brief builds on previous reports that examined states’ preparation for implementation prior to the initial ACA open enrollment period and their experiences after completion of the first and second open enrollment periods. Together, this work provides an in-depth understanding of ACA implementation from multiple perspectives, tracking and documenting experiences that may help shape efforts moving forward. Key findings from this brief include the following:

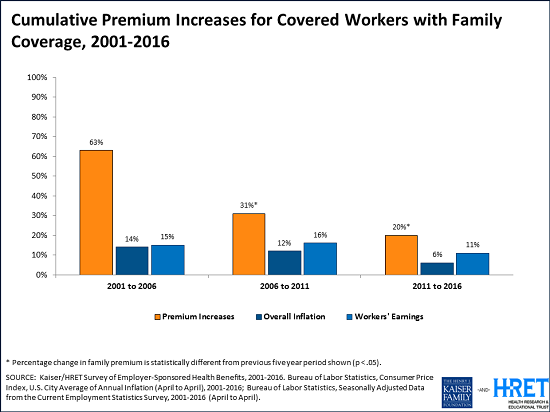

The study states use varied models to deliver care to Medicaid enrollees. Kentucky and Washington provide care through Medicaid managed care plans, while Connecticut and Colorado rely on fee-for-service models. Connecticut administers services through four administrative services organizations (ASOs) for medical services, behavioral health, dental care, and non-emergency transportation.

While the Medicaid delivery systems vary across the study states, they all have features to coordinate care and provide targeted case management to high-risk individuals. These include connecting individuals to medical homes, linking individuals to other services to address their broad needs, and utilizing care managers to help reduce emergency department use. Colorado and Washington are using regional approaches to coordinate care. In Colorado, most enrollees receive care on a fee-for-service basis, but enroll in one of seven Regional Care Collaborative Organizations (RCCOs). The RCCOs are designed to connect enrollees to Medicaid providers, including a primary care provider to serve as their medical home, and social services and to coordinate their care. In Washington, regional Accountable Communities of Health (ACHs) work in tandem with the managed care plans to identify regional priorities, coordinate activities, and distribute funds to help integrate health care and social services and improve population health.

Overall, stakeholders and focus group respondents report Medicaid enrollees in the study states have generally good access to primary and specialty care, although there are some access challenges. Stakeholders, focus group respondents, and state data suggest that enrollees generally are accessing needed services, including primary and preventive care as well as most specialty services and prescription drugs. Stakeholders also indicated that Medicaid expansion has significantly increased individuals’ access to specialty care, since many individuals were unable to access specialty services while uninsured. However, they also point to some access challenges, including limited availability of providers and inaccurate provider directories. Some of these challenges reflect limited provider participation in Medicaid, while others are access challenges that extend beyond Medicaid, such as overall provider shortages in rural areas. Stakeholders also pointed to the importance of being able to measure and monitor access over time.

Enrollees appear to face particular challenges accessing dental and behavioral health services. All four study states provide adult dental benefits. Focus group respondents indicated that they highly value this coverage and many had obtained services, including cleanings, fillings, and extractions. However, respondents and stakeholders identified some challenges accessing dental care, including limited availability of dentists accepting Medicaid patients and long waits for appointments. Focus group respondents and stakeholders also pointed to challenges accessing behavioral health services. Stakeholders indicated a need for additional behavioral health providers, particularly addiction treatment providers given the current heroin and opioid addiction crisis.

The study states have pursued initiatives to increase provider participation in Medicaid. Connecticut moved to streamlined, statewide policies, including a statewide fee schedule and drug formulary, and bi-weekly provider payments, which state officials believe helped increase provider participation. It also extended the temporary increase in primary care rates established under the ACA. Colorado also maintained the temporary primary care rate increase, and state officials noted that they are conducting a broader review of provider rates. Colorado is also working to expand capacity in rural areas by enabling primary care providers to consult electronically with specialists. In 2014, Kentucky expanded access to behavioral health providers by allowing Medicaid to contract with individual providers (rather than through community mental health centers), creating additional provider types (such as licensed drug and alcohol counselors), and adding coverage of additional behavioral health services to Medicaid. Washington has sought to ensure provider participation by adopting strong network adequacy standards for managed care plans.

Community health centers (CHCs) in the study states reported they have made a variety of investments to expand access to care, in part, due to enhanced revenues from the Medicaid expansion. However, some respondents cited challenges to meeting increased demands for care and continued growth, including increasing competitive pressures for clinical staff and a need for funding to support capital development.

Looking ahead, the states are pursuing changes to their Medicaid delivery systems. The Governor in Kentucky is seeking to make changes to its Medicaid program under a waiver, which may affect enrollment and access to care moving forward. Connecticut, Colorado, and Washington are pursing initiatives to transform their health care delivery systems, including Medicaid, with a focus on integrating physical and behavioral health care, adopting new payment models, and addressing social determinants of health. A growing set of initiatives at the federal level are helping to facilitate these state efforts through both technical assistance and funding. These delivery system reform efforts are broad-based efforts that are still in early stages of implementation. It will take time for the states to fully implement these initiatives and for impacts on health outcomes to materialize. Continued monitoring of these initiatives over time will be important to assess their effects on access to care.

Issue Brief

Introduction

As of Spring 2016, states had completed the third open enrollment period (OE3) for the Health Insurance Marketplaces and most of the 32 states, including DC, that had adopted the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults were well into their third year of implementation. With three years of expanded coverage in place, many states have increasingly shifted focus from outreach and enrollment to strengthening delivery systems and enhancing access to care to meet the needs of their growing covered populations.

This brief provides an on-the-ground view of Medicaid delivery systems and access to care in four states—Connecticut, Colorado, Kentucky, and Washington—three years into implementation of the ACA and highlights specific strategies the states are utilizing to enhance access and strengthen their delivery systems. These states implemented the Medicaid expansion in 2014 and have had successful implementation experiences with large increases in Medicaid enrollment. As such, their experiences may help inform other state efforts moving forward. A separate brief reviews these states’ experiences with outreach and enrollment during OE3.

This brief is based on case studies conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU) during Spring 2016. Working with PerryUndem Research/Communication, the Foundation conducted 28 in-person and phone interviews with a range of stakeholders in each state, including Medicaid and Marketplace officials, consumer advocates, assisters, and hospital and community health center (CHC) representatives. In addition, focus groups were conducted with Medicaid and Marketplace enrollees in each state. This work builds on previous analyses that examined states’ preparation for implementation prior to the initial ACA open enrollment period in October 2013 and subsequent reports examining state experiences after completion of the first and second open enrollment periods. Together, this work provides an in-depth understanding of ACA implementation from multiple perspectives, tracking and documenting experiences that may help shape efforts moving forward.

Key Findings

Study State’s Medicaid Delivery Systems

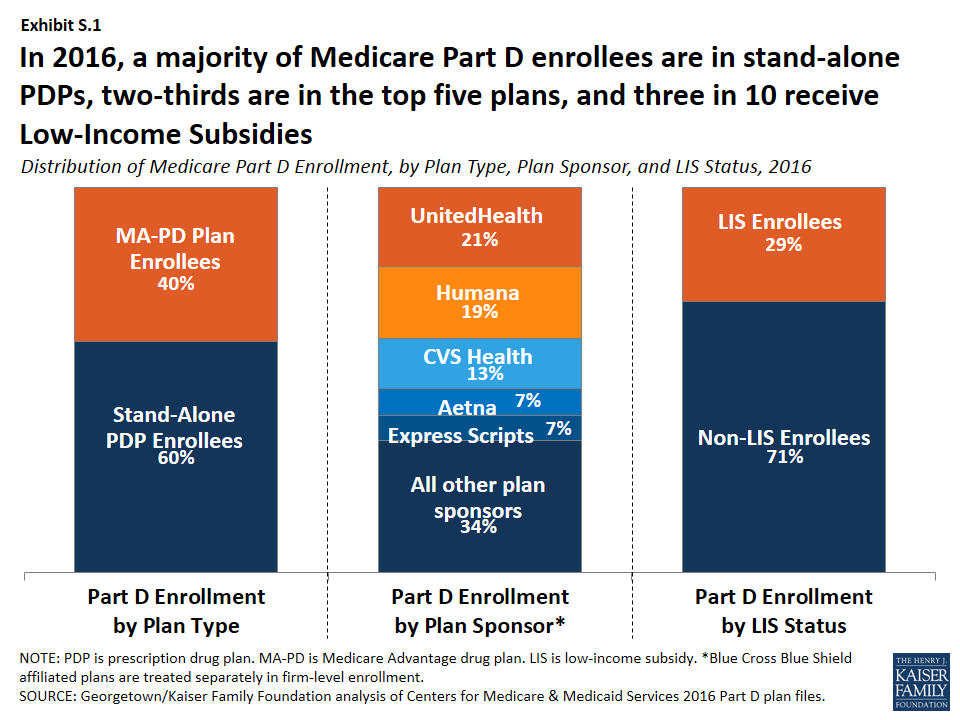

The study states are using varied models to deliver care to Medicaid enrollees (Figure 1). Kentucky and Washington provide care through Medicaid managed care plans. In contrast, beginning in 2012, Connecticut terminated its managed care contracts and now utilizes a managed fee-for-service system that is administered through four administrative service organizations (ASOs) for medical services, behavioral health, dental care, and non-emergency transportation. Colorado has traditionally relied on a fee-for-service model to deliver care. In 2011, it implemented its Accountable Care Collaborative (ACC). Under the ACC, most enrollees continue to receive care on a fee-for-service basis, but enroll in one of seven Regional Care Collaborative Organizations (RCCOs) across the state, which are intended to connect enrollees to Medicaid providers and social services and help coordinate care.

While the Medicaid delivery systems vary across the study states, they have features designed to coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees. In Colorado and Washington, care is coordinated through a regional approach.

- Connecticut implemented a primary care medical home (PCMH) initiative and has connected about 40% of enrollees to PCMHs, which have extended hours, coordinate care, and use electronic health records (higher shares of enrollees have a primary care doctor but may not be attributed to a PCMH). Connecticut pays enhanced fees and performance bonuses to PCMHs and withholds a percentage of the fees paid to ASOs, which they can earn back based on measures of quality and patient care experience. The state reports that under this model, per member per month costs have declined, including a 6% decline last year, and measures point to improvements in care.

- Colorado connects Medicaid enrollees with a RCCO and a primary care medical provider (PCMP) to serve as their medical home. The model intends for the PCMP to be the primary source of most medical services for the enrollee and for the PCMP to connect individuals to specialty services and provide health education. As of June 2015, about 70% of Medicaid enrollees were in a RCCO, and about 75% of RCCO enrollees had a PCMP.1 The state provides enhanced payments to PCMPs and RCCOs that meet specific performance targets and other goals. However, most focus group respondents did not have a primary care provider and a number reported challenges managing their care. They also did not know whom to contact for assistance navigating the health system. Consistent with these experiences, a 2015 evaluation of the ACC found inconsistent contact between primary care providers and enrollees and the need for patient education on the role of the PCMP.2

- Washington and Kentucky rely on managed care plans to coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees. In Washington, Accountable Communities of Health (ACHs) work in tandem with the managed care plans to identify regional priorities, coordinate activities, and distribute funds in efforts to integrate the delivery of health care and social services and improve population health. However, the ACHs are not risk-bearing entities, do not deliver services, and will not replace the role of managed care plans.

The states also provide targeted care management for high-risk individuals. Connecticut uses Medicaid claims data and predictive modeling to identify high-utilizers and high-risk enrollees for whom the ASOs provide care coordination and intensive care management. This care management includes addressing social determinants of health, such as housing stability and physical safety. The medical and behavioral health ASOs embed care managers in many health centers and include them in hospital discharge processes. Stakeholders in Connecticut reported that the care management has helped to reduce emergency department use. In Washington, the managed care plans connect Medicaid enrollees with chronic conditions to a care manager who is responsible for managing all aspects of their care. The plans also embed care managers in health centers to ensure care is coordinated within the health centers and across providers outside the health center. Kentucky also has efforts focused on increasing care management for Medicaid enrollees who are high-utilizers of emergency department care.

Access to Care for Medicaid Enrollees

Overall, stakeholders and focus group respondents report Medicaid enrollees in the study states have generally good access to primary and specialty care. Focus group respondents indicated that they generally are accessing needed services including primary and preventive care. Stakeholders and focus group respondents also reported that Medicaid enrollees are able to access most specialty services, including care for chronic conditions, surgeries, imaging, and lab tests, as well as prescription drugs. Stakeholders also indicated that Medicaid expansion has significantly increased individuals’ access to specialty services. They noted that, while individuals could access primary care through clinics while uninsured, it was very difficult for them to obtain specialty care. With Medicaid coverage, individuals are able to access specialty care more easily and quickly. Other data also point to good access to care for Medicaid enrollees in these states. For example, one study shows that the share of Medicaid enrollees in Colorado who visited a health professional, had a preventive care visit, visited a specialist, or had a usual source of care was comparable to or better than those with private coverage and much better than the uninsured.3 Studies also show that the Medicaid expansion in Kentucky was associated with significant reductions in skipping medications because of cost, decreases in trouble paying medical bills among low-income adults, and reductions in unmet medical need.4

However, some access challenges remain. Some focus group respondents indicated that some providers they reached out to were not accepting Medicaid patients. In Colorado, statewide data also show that one in five Medicaid enrollees did not get needed care because the doctor’s office was not accepting their insurance, double the rate for the total population. However, this rate has remained around 20% since 2009, despite the large growth in Medicaid enrollment post-ACA.5 Other access challenges were associated with managed care plan provider networks and formularies. For example, in Kentucky and Washington, some focus group respondents noted that their health plan provider directories were inaccurate and out-of-date. Some respondents in Kentucky also indicated that they needed to switch providers because their provider was not participating with their health plan. One stakeholder in Kentucky noted that one of the large managed care plans in Lexington did not include the University of Kentucky in its provider network, which significantly limited access to specialists for enrollees in that plan. A few respondents indicated they had challenges obtaining medications or had to switch to a different medication because it was not included on their plan’s formulary. These plan-related challenges were not limited to Medicaid, as focus group respondents enrolled in Marketplace plans reported similar issues. Other access challenges, such as provider shortages and transportation issues in rural areas, also extended beyond Medicaid.

I couldn’t find a doctor and I checked all the books that they sent me. Most of the information was outdated.

-Davita, Kentucky Medicaid enrollee

All four study states provide adult dental benefits, which Medicaid enrollees highly value, but enrollees and other stakeholders pointed to challenges accessing dental care in three of the four states. Washington and Connecticut provide comprehensive adult dental benefits, while the adult benefits in Colorado and Kentucky are more limited.6 Focus group respondents indicated that they highly value this coverage and many had obtained dental services, including cleanings, fillings, and extractions. Stakeholders and respondents indicated that health centers, in particular, are a key source of dental care for Medicaid enrollees. However, respondents and stakeholders identified some challenges accessing dental care, including limited availability of dentists accepting Medicaid patients and long waits for appointments. Stakeholders recognized that dentist participation and access generally is better for children compared to adults, and that access is often more challenging in rural areas. In Kentucky, stakeholders reported that there is better access in Louisville compared to other areas due to its proximity to a dental school. In contrast to the other study states, state officials in Connecticut noted that they have some of the best dental care access in the country and that enrollees generally can access services within a five-mile radius in about a day. Consistent with these reports, focus group respondents in Connecticut reported good access to dental care. Officials indicated that several factors contribute to this access, including close engagement with the dental Administrative Services Organization (ASO), a strong partnership with the state dental association, a previous lawsuit that found inadequate access, increased rates, and enhanced focus on provider engagement.

Since I’ve had Husky we’ve been able to get a lot of my dental stuff done, myself as well as my son.

-Pam, Connecticut Medicaid enrollee

I think it’s because there were so many people enrolling and there weren’t enough dentists taking Apple Health …It’s pretty much like whenever you can get in because there are so few [dentists] that take it.

-Nicholas, Washington Medicaid enrollee

Focus group respondents and stakeholders also pointed to challenges accessing behavioral health services. Some focus group participants in Kentucky and Colorado noted long waits and difficulty finding mental health providers. Two participants in Colorado also reported difficulty and delays obtaining medication to address their behavioral health needs. Across the study states, stakeholders indicated a need for additional behavioral health providers to address mental health and substance use disorder needs. Stakeholders in Washington and Connecticut indicated that the limited supply of addiction treatment providers is particularly challenging in light of the current heroin and opioid addiction crisis. Washington has an initiative to divert people with substance use disorders from jail into treatment, but there are insufficient Medicaid providers to treat all who need care. Stakeholders in Washington also noted that lack of reimbursement to behavioral health organizations for activities such as home visits as well as separate electronic health records for physical and behavioral health present barriers to fully addressing patients’ needs. Stakeholders across the study states also pointed to growing populations of non-English-speaking and ethnically and culturally diverse enrollees as an emerging challenge related to behavioral health access and utilization.

…I couldn’t find a mental health professional to fill my prescriptions

-Eileen, Colorado Medicaid enrollee

Provider Capacity

The study states have pursued initiatives to increase provider participation in Medicaid.

- In Connecticut, state officials noted that under its previous managed care model, providers faced challenges that limited participation, including administrative hurdles, slow payments, and variation in utilization management tools and rate schedules across plans. As the state moved away from the managed care model to its current fee-for-service model with ASOs, it worked to increase physician participation by implementing streamlined and uniform provider requirements, a statewide fee schedule and drug formulary, and bi-weekly provider payments. Officials indicate that this streamlined approach has increased participation among primary care providers and specialists. Connecticut also extended the temporary increase in primary care rates established under the ACA, but officials suggest that the other factors had a larger influence on provider participation than the rate increase.

- Colorado also maintained the primary care rate increase, and state officials noted that, as part of efforts to ensure access, they are conducting a broader review of provider rates. Colorado is also working to expand physician capacity in rural areas through a recently adopted approach that enables primary care providers to consult electronically with specialists. Stakeholders also pointed to the importance of being able to measure and monitor access. One initiative in the state, the Access to Care Index, provides regional-level data on utilization and access barriers (Box 1).

- In 2014, Kentucky expanded access to behavioral health providers by allowing Medicaid to contract with individual providers (rather than through community mental health centers), creating additional provider types (such as licensed drug and alcohol counselors), and adding coverage of services to Medicaid (such as additional services for substance use disorder treatment). State officials noted that adding new providers required Medicaid certification, new licensure categories, changes in state regulations, and coordination with the plans to integrate these new providers. One study shows that more than 300 new behavioral health providers enrolled in Kentucky Medicaid and at least 13,000 individuals with a substance use disorder received related treatment services during the first year of expansion.7

- Washington has sought to ensure adequate provider participation by adopting strong network adequacy standards for managed care plans. State officials noted that they work with plans to resolve identified access issues. The state is also considering options for increasing participation of dentists, including examining the fee schedule for adult dental care and contracting dental care to a third-party administrator.

Community health centers (CHCs) have expanded capacity following Medicaid expansion. CHCs in the study states reported they have made a variety of investments to expand access to care, in part, due to enhanced revenues from the Medicaid expansion. Examples of enhancements include adding clinical staff, including behavioral health providers; building dental clinics and expanding dental service capacity; providing intensive care management; addressing social determinants of health (e.g., housing); and adding case managers. However, some health centers cited challenges to meeting increased demands for care and continued growth, including increasing competitive pressures for clinical staff. For example, stakeholders in Kentucky indicated that health centers have to compete for primary care providers because hospitals are increasingly purchasing family medicine practices. Similarly, in Colorado, stakeholders indicated that provider recruitment and retention challenges hinder continued growth since health center salaries are not competitive with the private market. A stakeholder in Connecticut also noted that funds for capital development are key for supporting increased capacity among health centers moving forward.

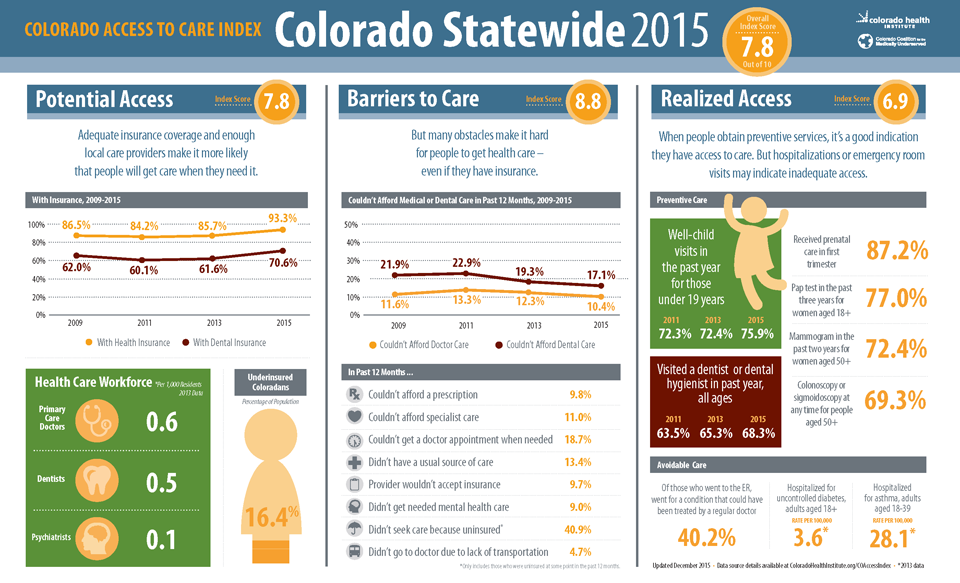

Box 1: Colorado Access to Care Index8

The Colorado Access to Care Index is designed to measure whether the increase in Coloradans with health coverage following the implementation of the ACA is translating into a change in the ability to access care, help communities across Colorado better understand access to care challenges, and guide conversations about how to address these challenges. The statewide index score increased to 7.8 in 2015 from 7.7 in 2013, both out of a possible 10 points, showing that access to care is trending upward.

The Colorado Access to Care Index is based on about 30 measures that primarily come from the Colorado Health Access Survey, which is a survey of over 10,000 households in Colorado fielded by the Colorado Health Institute. The Colorado Index is produced biennially and tracks health access changes among the 21 regions within the state, by income-level (0-138% FPL, 139-400% FPL, and over 400% FPL), and for two racial/ethnic groups (Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Coloradans).9 Measures are divided into three categories: potential access, barriers to care, and realized access.

A comparison of the 2013 and 2015 Index scores for the three income-level groups suggests that although access remains more limited for low-income compared to higher income populations in Colorado, access disparities between the income groups appear to be narrowing. The overall access score for the Medicaid-eligible population (below 138% FPL) increased from 6.5 in 2013 to 7.2 (out of 10) in 2015 and the overall access score for the population eligible for Marketplace subsidies (139-400% FPL) increased from 7.7 in 2013 to 8.0 in 2015. However, the scores for both of these populations remain below the overall access scores for the population above 400% FPL, which decreased slightly from 8.8 in 2013 to 8.7 in 2015. The disparity between income groups is greatest for the potential access category scores, suggesting that addressing potential access barriers (e.g. insurance coverage rates and provider availability) for low-income populations might be an efficient approach to reducing access disparities more broadly.10

Key Issues Looking Ahead

In Kentucky, the governor is pursuing a waiver to make changes to coverage under the state’s existing Medicaid expansion program.11 On June 22, 2016, Governor Bevin released his proposed Section 1115 demonstration waiver application called Kentucky HEALTH (Helping to Engage and Achieve Long Term Health) as an alternative to the current Medicaid expansion. The proposed waiver includes many provisions similar to those in Indiana’s Medicaid expansion waiver (including a high deductible account and premiums), but also includes provisions not approved to date in other states, such as a work requirement and graduated premiums based on length of time in the program that will exceed Marketplace levels for those above 100% FPL. The proposal includes a number of changes that would affect Medicaid expansion enrollees as well as traditional non-disabled Medicaid enrollees. Kentucky estimates that projected Medicaid enrollment will decrease over the 5-year waiver period. The proposed waiver was open for public comment at the state level through July 22, 2016, during which the state received over 1,400 comments. The state submitted the waiver proposal to CMS on August 24, 2016.

Integrating physical and behavioral health care is a key focus in the states. In Kentucky, managed care plans provide both physical and behavioral health services to Medicaid enrollees. The state integrated these services when it launched its managed care program in 2011. In contrast, Connecticut, Colorado, and Washington currently provide physical and behavioral health services to Medicaid enrollees through separate entities, but each has efforts underway to integrate this care.

- In Washington, managed care plans provide physical care services while regionally operated Behavioral Health Organizations (BHOs) provide behavioral health services. Medicaid managed care plans in Washington are working with the BHOs to place behavioral health providers in primary care settings, with the goal of increasing identification of substance use disorders and access to treatment. The state launched a fully integrated managed care pilot program in two counties on April 1, 2016, and plans to integrate services statewide by 2020. State officials reported that the pilot program transition has gone smoothly so far, and credited efforts by the local ACH to bring together key stakeholders and help garner provider support.

- In Colorado, the RCCOs currently are responsible for physical care, while separate Behavioral Health Organizations (BHOs) provide behavioral health care. In 2018, Colorado plans to reorganize its system to integrate physical and behavioral health. Under the new model, Regional Accountable Entities (RAEs) will replace the RCCOs and BHOs and provide both physical and behavioral health care. The state also plans to increase accountability of the RAEs for improved health outcomes and cost efficiencies by tying a greater proportion of administrative payments to value.

- Connecticut has separate ASOs for medical and behavioral health care. However, through a collaboration between Medicaid and the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, the state implemented a behavioral health home program for people with a diagnosed mental illness and high Medicaid spending that coordinates and integrates physical and behavioral health care as well as referrals for community-based services. Most of the behavioral health homes are local mental health authorities. Connecticut also is one of eight states participating in a federal demonstration of certified community behavioral health clinics that aims to expand access to high quality integrated physical and behavioral health care.

Connecticut, Colorado, and Washington also have broader initiatives underway to transform delivery systems, including efforts to move to value based payments and address social determinants of health.

- Connecticut plans to move to a value-based payment strategy in Medicaid under which it will offer shared savings to community health centers and other entities that meet a set of care coordination standards that build on the patient centered medical home and include new standards for behavioral health integration and links to community supports. The state plans to move about one-third of Medicaid enrollees to this value-based payment program with implementation slated to begin January 1, 2017. Connecticut also has an inter-agency, public/private Supportive Housing Initiative to develop long-term solutions to the housing and other needs of individuals with behavioral health needs and/or substance use disorders.

- Washington has a waiver pending with CMS that would use Delivery System Reform Incentive Payments (DSRIPs) to fund Medicaid delivery system transformation projects led by the ACHs that focus on health systems capacity building, care delivery redesign, and population health improvement. In addition, the waiver seeks to provide supportive housing and supported employment services to certain Medicaid beneficiaries. The state expects these initiatives to improve health outcomes, reduce costs, build better linkages to non-health sectors, affect the social determinants of health, and foster a health system that supports wellness and recovery.

- Colorado, Connecticut, and Washington have received State Innovation Model (SIM) grants to support broader transformation of state health care systems that will include Medicaid and other payers. Under its SIM model, Colorado is seeking to provide access to integrated primary and behavioral health services, with value-based payments structures, for 80% of state residents by 2019. In addition to integrating physical and behavioral health services by 2020, the Healthier Washington Plan aims to shift to an outcomes-based system for paying providers and adopt a collaborative, regional approach to building healthier communities. Toward the goal of payment system reform, the state has implemented an Accountable Care Organization for public employees; launched the Practice Transformation Support Hub to provide training and tools to providers to help reorient physician practices; and developed 55 common measures to track health system performance and inform public and private health care purchasing. Connecticut has similar goals to transform the health care delivery system through movement toward value-based payment and adoption of an advanced medical home model; enhanced coordination among community organizations, providers, schools, and other local entities to improve population health; and increased consumer engagement in making informed health care decisions and managing their own health.

Conclusion

As of the end of the third open enrollment period, these four states have had significant enrollment growth in their Medicaid programs through the Medicaid expansion. With this growth, they have increasingly turned attention to delivery of and access to care for the increasing population covered by the program. The case study states vary in how they deliver care through their Medicaid programs, but all include elements to coordinate care for enrollees. Overall, these case study and focus group findings suggest that, despite the large enrollment growth since implementing the ACA, Medicaid enrollees generally are able to access the preventive, primary, and specialty care they need. However, they do face some access challenges. Some of these challenges reflect limited provider participation in Medicaid, while others are access challenges that extend beyond Medicaid, such as overall provider shortages in rural areas. Enrollees appear to face particular challenges accessing dental and behavioral health services. The study states have undertaken efforts to increase provider participation and expand provider capacity and are continuing work to address remaining access gaps.

Looking ahead, the Governor in Kentucky is seeking to make changes to its Medicaid program under a waiver, which may affect enrollment and access to care moving forward. Connecticut, Colorado, and Washington are pursing initiatives to transform their broad health care delivery systems, including Medicaid, with a focus on integrating physical and behavioral health care, adopting new payment models, and addressing social determinants of health in an effort to improve overall population health. A growing set of initiatives at the federal level are helping to facilitate these state efforts through both technical assistance and funding. These delivery system reform efforts are broad-based efforts that are still in early stages of implementation. It will take time for the states to fully implement these initiatives for impacts on health outcomes to materialize. Continued monitoring of these initiatives over time will be important to assess their impacts on access to care.

Methods

The findings in this brief are based on structured interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with Medicaid and Marketplace enrollees conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and PerryUndem Research/Communications in four states, Colorado, Connecticut, Kentucky, and Washington, in May 2016. In total, we conducted 28 in-person and phone interviews with a range of stakeholders in each state, including Medicaid and Marketplace officials, consumer advocates, assisters, and hospital and community health center (CHC) representatives. Two focus groups were held in each state, one with individuals enrolled in Medicaid coverage and the other with individuals with income less than 300% of the federal poverty level ($35,640 for an individual in 2016) enrolled in coverage through the Marketplace. The focus groups were held in Denver, Colorado; Hartford, Connecticut; Lexington, Kentucky; and Seattle, Washington. Each focus group consisted of 8 participants with a total of 64 participants, including 32 enrolled in Medicaid and 32 enrolled in Marketplace coverage. Focus group participants were selected to provide a mix of demographic characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, and health status. Most individuals had used services since obtaining their current coverage.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Michael Perry, Sean Dryden, and Naomi Mulligan Kolb with PerryUndem Research/Communication for their work managing the fieldwork logistics, conducting the interviews, and moderating the focus groups. They also extend their deep appreciation to all the participants for sharing their perspectives and experiences to inform this project.

Endnotes

- Richard Lindrooth PhD, Gregory Tung PhD, Tatiane Santos PhD, and Sean O’Leary MD, Evaluation of the Accountable Care Collaborative: Year 1 Report, (Colorado School of Public Health, November 30, 2015), https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/Supporting%20a%20Culture%20of%20Coverage%20Accountable%20Care%20Collaborative%202014-15%20Annual%20Report.pdf ↩︎

- Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, Supporting a Culture of Change: Accountable Care Collaborative 2015 Annual Report, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/ACC%20Evaluation_Year%201%20Final%20Report_Final%2012%207%2015%20(1).pdf ↩︎

- Use of Health Care, Percentage of Coloradans Using Health Services, by Coverage, 2015, http://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/key-issues/detail/health-coverage-and-the-uninsured/colorado-health-access-survey-1 ↩︎

- Benjamin Sommers, Robert Blendon, and E. John Orav, “Both the ‘Private Option’ And Traditional Medicaid Expansions Improved Access To Care For Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs 35, no. 1 (January 2016): 96-105, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/1/96.abstract; and Joseph Benitez, Liza Creel, and J’Aime Jennings, Kentucky’s Medicaid Expansion Showing Early Promise on Coverage and Access to Care, Health Affairs (February 2016), http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2016/02/16/hlthaff. 2015.1294 ↩︎

- Natalie Triedman (Ed.), A New Day in Colorado, Health Insurance Reaches Record High: Findings from the 2015 Colorado Health Access Survey, (Denver, CO: Colorado Health Institute, September 2015), http://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/uploads/downloads/2015_CHAS_for_Web_.pdf ↩︎

- Defined as fewer than 100 diagnostic, preventive, and minor restorative procedures recognized by the American Dental Association (ADA) and per-person annual expenditure for care is $1,000 or less. http://www.chcs.org/media/Adult-Oral-Health-Fact-Sheet_020816.pdf ↩︎

- Deloitte Development LLC, Commonwealth of Kentucky Medicaid Expansion Report, (Deloitte Development LLC, February 2015), http://jointhehealthjourney.com/i mages/uploads/channelfiles/Kentucky_Medicaid_Expansio n_One-Year_Study_FINAL.pdf ↩︎

- Colorado Access to Care Index, http://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/key-issues/detail/new-models-of-health-care/colorado-access-to-care-index ↩︎

- There is insufficient data for indices specific to other racial/ethnic groups ↩︎

- Colorado Health Institute, Access to Care Improving in Colorado, Updated December 2015, http://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/uploads/downloads/Access_to_Care_4_pager-_Dec2015.pdf ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Proposed Changes to Medicaid Expansion in Kentucky, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, July 2016), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/proposed-changes-to-medicaid-expansion-in-kentucky/ ↩︎