Introduction

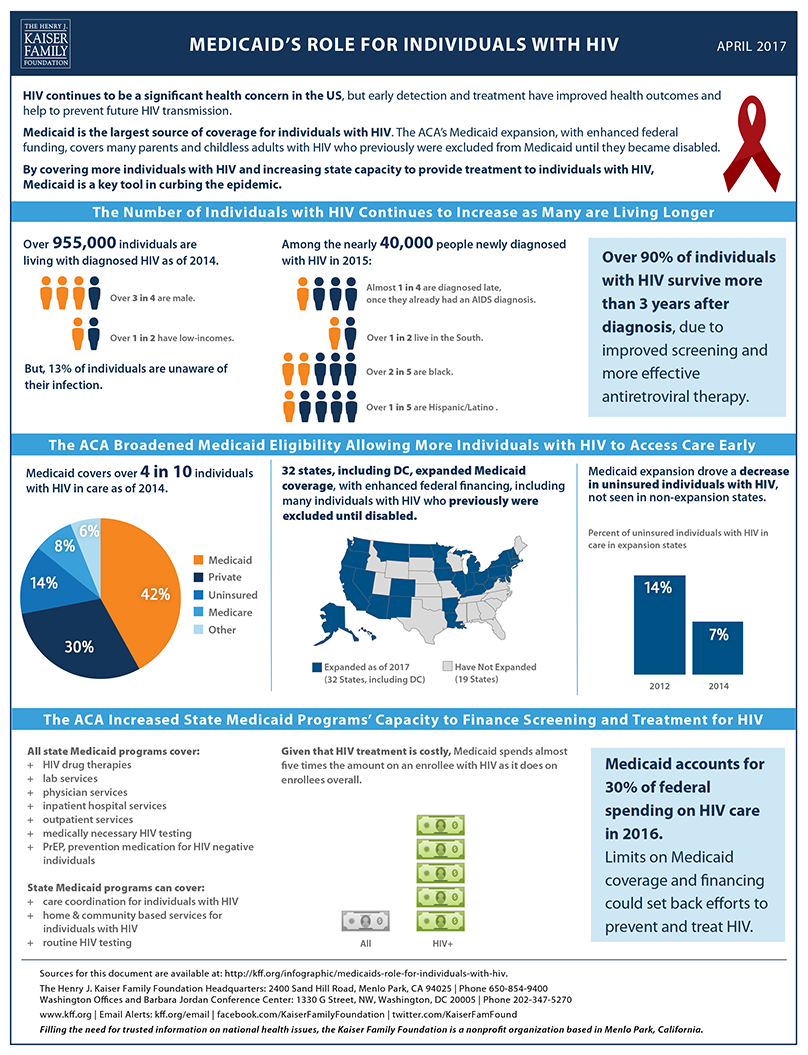

Medicaid now provides health insurance coverage to more than one in five Americans, and accounts for nearly one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.4 Medicaid is jointly financed by the states and the federal government. In FY 2015, Medicaid accounted for 28.2 percent of total state spending (including state and federal funding) for all items in the state budget, but 15.6 percent of all state spending (from general fund and other state funds), a far second to state spending on K-12 education (24.8%). Medicaid is the largest single source of federal funds for states, accounting for more than half (56.8%) of all federally supported spending by states in SFY 2015, according to data from the National Association of State Budget Officers. Increases in Medicaid as a share of overall state budgets have been driven by coverage expansions resulting from the Affordable Care Act (ACA), especially for the 32 states (including DC) that have thus far taken advantage of the ACA Medicaid expansion for adults up to 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). That expansion included an enhanced federal match rate (known as the federal medical assistance percentage, or “FMAP”) for expansion populations which began at 100 percent in 2014, but phases down (starting at 95 percent in January 2017) to 90 percent in 2020 and future years.

While the federal government continues to bear almost the entire cost for ACA Medicaid expansion populations, many states currently face budget challenges in an environment of relatively weak state revenue growth. After seven straight quarters of growth, total state tax revenues fell by 2.1 percent in the second quarter of 2016 (compared to the second quarter of 2015) with tax collections falling in about half the states.5 Modest growth (1.2 percent) resumed in the third quarter of 2016 with even weaker growth (0.04 percent) projected for the fourth quarter leading to a gloomy state budget outlook for the remainder of FY 2017 for some states.6 At the time that states adopted their budgets for FY 2017, the state share of Medicaid spending, on average, was budgeted to grow by 4.4 percent representing an increase over FY 2016 (2.9%) largely due to the FMAP reduction for ACA expansion enrollees that took effect in January 2017.7

As state policymakers in most states approach the task of adopting a state budget for FY 2018, they do so against the backdrop of great uncertainty at the federal level regarding health care and federal tax policy. President Trump and other GOP leaders have called for the repeal and replacement of the ACA as well as fundamental changes regarding the structure and financing of Medicaid generally. At the same time, GOP leaders have expressed the goal of enacting federal tax reform legislation which could have significant impacts on state economies and state revenue collections. Further, other federal budget proposals, from federal hiring freezes and discretionary program cuts on the negative side to potential new infrastructure funding and defense spending increases on the positive side, could have widely disparate impacts across the states that are currently impossible to predict.

Methods

This report provides Medicaid highlights from governors’ proposed budgets for state fiscal year (FY) 2018, which runs from July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018 in most states.8 The analysis is based on a review of state budget documents, news reports, and other relevant documents. Links to proposed budget documents can be found in Appendix Table 3. In total, 47 states will enact a new budget for FY 2018 while three states (Kentucky, Virginia, and Wyoming) have previously enacted budgets that cover FYs 2017 and 2018. We reviewed 48 state budgets (including proposed supplemental changes to the 2017-2018 biennium budgets for Virginia and Wyoming). Generally, proposed budgets were released late in 2016 and early in 2017. Also, Arkansas and the District of Columbia had not released proposed budgets for FY 2018 at the time of this analysis (DC’s budget year does not begin until October 1, 2017).

This analysis is not comprehensive but is designed to capture major new proposals and changes included in the proposed budgets (also see Appendix Table 1 for Medicaid policy action counts by state). The level of detail presented in governors’ proposed budget documents varies significantly and in most cases does not capture all of the activity in a given state. Governors’ budgets commonly include both funding for state initiatives that are already in place or approved by the state legislature as well as proposals for new policies or initiatives that have not yet been adopted. Often proposed budgets are very different than what is ultimately approved by the state legislature. In addition, some proposed budgets include proposals that would also need to be approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) before a state could implement the policy. In the summer of 2017, the Kaiser Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured with Health Management Associates will conduct a more comprehensive review of Medicaid changes that were adopted in state budgets for FY 2018. As in previous years, this annual 50-state Medicaid budget survey report should be available in the fall.

Key Findings

Budget Message

While a number of states have improving economies and stable state finances, half are facing budget challenges for FY 2018. Recovery from the Great Recession has been slow and uneven across the states with 32 states spending less in FY 2016 than the pre-recession peak in FY 2008 after adjusting for inflation.9 Individual state results vary widely due, in part, to economic differences and state specific changes in state tax policy. For example, state budgets that rely most heavily on oil and mineral severance taxes (i.e., Alaska, Louisiana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming) have been hard hit by falling gas and coal prices which have led to cuts in production and employment.10 Other states, however, have also experienced declining state revenues in recent quarters including Alabama, Arkansas, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania in the third quarter of 2016 and, in the fourth quarter of 2016, projected declines for California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, and Vermont.11 A few states are also dealing with significant structural imbalances. Examples include the following:

- Connecticut is facing a $1.5 billion deficit for FY 2018 requiring deep cuts to agency budgets. Pennsylvania is facing a $3 billion deficit leading the governor to call for $2 billion in cuts and savings measures for FY 2018. West Virginia is proposing a combination of cuts and revenue enhancements and a reduction in the size of state government to address the FY 2018 state budget forecast that the governor called the “worst we’ve seen since the Great Depression.”

- Illinois has $11 billion in unpaid bills, a $130 billion unfunded pension liability, and has not had a full year budget since FY 2015. Kentucky’s governor has called on the Kentucky legislature to address underfunding of the state’s pension system which he called “a crisis.”

- Kansas is working to achieve a structural balance by FY 2019 after several years of imbalance exacerbated by tax cuts passed in 2012.

- Maryland’s proposed budget for FY 2018 addresses a $544 million shortfall by spending less in General Funds in FY 2018 than in FY 2017 and by holding Total Fund growth to 1.1 percent—the second-lowest year-over-year percentage increase since at least 1970.

Overall, at least 12 governors are proposing broad-based state budget cuts for FY 2018. For example, of the 55 executive agencies that receive General Fund appropriations in New Mexico, 49 of them took a 5.5 percent reduction for FY 2017 which is proposed to remain in place in FY 2018. In North Dakota, all agencies were asked to identify budget savings of 10 percent of this biennium’s ongoing appropriations.

A few governors reported more positive economic and state budget outlooks. For example, the Idaho governor reported that finances are secure, revenues are exceeding expectations, and economic growth is outpacing the overall growth of government; the Tennessee governor stated that “the state of our state has never been better,” with economic growth outpacing the national economy, a triple-A credit rating, and a Rainy Day Fund that is projected to reach an all-time high in FY 2018; and the Minnesota governor reported on six years of improvement in the state’s budget outlook moving from deficits to surpluses.

Proposed budgets prioritize K-12 and higher education funding and fostering a strong economy. Education accounts for the largest share of state General Fund budgets and continues to be the highest budget priority in most states. Many governors also proposed initiatives to foster a stronger economy including tax modernization efforts, workforce training initiatives, and infrastructure investments including transportation-related infrastructure, but also broadband expansions to rural areas. Other priorities that spanned multiple governors’ budgets included increased investments in public safety and law enforcement, criminal justice and corrections-related initiatives, efforts to improve the child protection and foster care systems, and health care improvement or expansion efforts, including efforts to address mental health and addiction issues. A few governors are also proposing environmental efforts to improve water and air quality.

Governors proposing tax cuts significantly outnumbered those proposing tax increases. Despite significant budget challenges in many states, most governors proposed FY 2018 budgets that include no new taxes. Proposed budgets in at least 17 states included various tax cut proposals (although four of these states – Maine, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – also proposed tax increases in other areas). A wide variety of tax cuts were proposed including to income taxes, sales taxes (such as eliminating the sales tax on groceries), and business taxes as well as efforts to provide property tax relief at the local level. For example, Florida’s proposed budget cuts business income taxes; provides sales tax holidays for back-to-school sales, disaster preparedness purchases, and veterans’ sales as well as a one-day camping and fishing sales tax holiday; and exempts seniors and veterans from certain fees. South Carolina’s governor is proposing a 1 percent rate reduction over ten years in the personal income tax and a 2.5 percent rate reduction over ten years to all corporate income tax.

At least 10 governors are proposing tax increases including several proposing to expand the sales tax base to professional services or on-line sales (Maine, Oklahoma, West Virginia, Utah, and Washington); two proposing to increase motor fuels taxes (Alaska and Tennessee); four proposing to increase tobacco taxes (Delaware, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Oregon), and three proposing increases to alcoholic beverage taxes (Kansas, Oregon, and West Virginia). Additional proposed tax increases include:

- Delaware’s governor proposed increases to personal income and corporate franchise taxes.

- Kansas’ governor proposed increasing taxes on passive income.

- Washington’s governor proposed a new capital gains tax, increasing the business and occupation tax rate that is applied to a broad range of personal and professional services, and enacting a new tax on carbon pollution associated with the production and consumption of fossil fuels.

- Oklahoma’s governor proposed a number of revenue changes with the goal of diversifying and strengthening state revenues and generating $1.5 billion in recurring revenue. Changes proposed include sales tax modernization, elimination of corporate income tax, transportation-related taxes and fees, a cigarette tax increase, a wind production tax, and an increase in the excise tax for commercial trucks.

Medicaid Policy Actions

Provider Payment Rates and Taxes

State actions on provider rate changes are generally tied to state fiscal conditions. During economic downturns, states tend to cut rates and when economic conditions improve states are less likely to cut rates and more likely to restore rate cuts or increase rates. Governors proposing provider rate increases for FY 2018 outnumber the governors proposing cuts or freezes. Of the 21 governors proposing increases, three governors proposed across the board increases for most provider types and five governors targeted nursing facilities for increases or restoration of inflationary adjustments (Table 1). Nevada (Adult Day Health, Assisted Living and Swing Beds) and Wisconsin (ICF/DDs) also proposed increases for other long term care providers, Hawaii and Ohio proposed to adjust waiver rates, and North Dakota proposed restoring a 10 percent rate cut for homemaker services. Also, seven governors proposed wage increases or overtime for home care workers, nursing home workers, or mental health direct care workers (Table 1).

Of the 16 governors proposing provider rate cuts, two governors proposed across the board cuts for most providers: 3 percent in Nebraska and 3.3 percent in Wyoming (excluding ID/DD waivers). Wyoming’s governor also proposed reimbursement reductions for Medicare cross-over claims.

| Table 1: Governors Proposing Selected Provider Rate Changes |

| Provider payment increases | Provider payment freezes/cuts |

| Across the board rate changes for most providers | KS, MD, SD | NE, WY |

| Hospital payment changes | NJ, NC, TN | CT, IN, FL, NH, OH, RI, VT |

| Nursing facility payment changes | HI, NV, ND, VA, WI | CT, IN, NY, OH, RI |

| Wage changes or overtime for home care workers, nursing home staff, or mental health direct care workers | AZ, MI, RI, TN, VA, WA, WI | |

| Managed care organization rate changes | UT | FL, LA, OR |

Other examples of governors proposing rate increases or freezes/cuts not listed above include:

- Targeted increases for primary care providers and OB/GYNs in Georgia, transportation providers in Missouri, and pediatric surgeons in Nevada.

- Proposed reductions in Kansas and Nevada for laboratory services and in Nevada for ambulatory surgery centers.

- Proposed elimination of facility fees for hospital-based physicians in Maine and Massachusetts and removal of inflationary adjustments for ICFs/DD in Connecticut.

- Proposed 14 percent dental rate cut in Delaware.

- Proposed extension of a 3 percent cut (that would otherwise have expired) for home health services in Indiana.

- New York’s governor would reduce the state’s pharmacy costs by establishing requirements for manufacturers to pay an additional rebate for certain high priced drugs and imposing a surcharge on these drugs when they are sold into the state.

- Oregon’s governor would reduce inflationary adjustments in the state’s FFS delivery system.

Eight governors are also proposing to impose new or increased provider taxes to help finance Medicaid spending growth including five governors (Georgia, Maine, Kansas, Oregon, and Texas) renewing or increasing a hospital tax, three governors imposing or increasing a managed care tax (Kansas, Ohio, and Oregon), one governor imposing a new nursing facility tax (North Dakota) and one governor reinstating a pharmacy tax (Alabama). Other types of Medicaid financing initiatives proposed include a faculty supplemental payment program in Colorado, increased use of tobacco tax revenues in Georgia and North Dakota, increased Medicaid claiming by schools in Connecticut, and increased federal funding for services provided for Native Americans in Kansas and New Mexico.

Eligibility Changes

Only a few governors are proposing changes to Medicaid eligibility policies. Some of these changes assume the continuation of the ACA status quo including proposed budgets in two states that recommend adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion (North Carolina and Virginia) and a proposal in Connecticut to reduce income eligibility for parents and relative caregivers to 138 percent FPL (to align with current Marketplace coverage). Two other governors are proposing eligibility expansions: using a Medicaid waiver, Idaho’s governor is proposing to expand Medicaid coverage to children with a serious emotional disturbance with family incomes below 300 percent FPL to meet the terms of a litigation settlement agreement, and North Dakota’s governor is proposing to increase the age limit for its Autism waiver. Five governors are proposing eligibility restrictions:

- Connecticut’s governor proposes to reduce income eligibility levels for the Medicare Buy-in program to those in effect prior to FY 2010 (but the asset test that was in place at that time would not be re-instituted).

- Kentucky’s governor would add a requirement for certain “able-bodied” adults to perform at least 20 hours of community engagement or employment activities each week.12

- New York’s governor would require legally responsible spouses/relatives to support the cost of caring for an institutionalized family member receiving Medicaid.

- Wisconsin’s governor would impose a requirement on childless adults that are not employed or who are underemployed to participate in employment and training services.

- Maine’s governor would end Medicaid eligibility for “able-bodied” parents with incomes above 40 percent FPL.

Benefits, Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Benefit actions are influenced by economic trends. Changes to dental coverage as well as other optional benefits are particularly affected by economic conditions. Nine governors are proposing benefit enhancements while only four governors are proposing benefit reductions. Five governors are proposing changes to adult dental benefits: three would add or restore benefits (Arizona, Hawaii, and Utah) while two governors would impose or reduce a dental benefit cap (Connecticut and Nebraska). Four governors (California, Georgia, Maryland, and Washington) are proposing new or expanded behavioral health services, governors in Oregon and Washington are proposing expanded coverage of Hepatitis C treatment, and Nevada’s governor would expand podiatry coverage. Nevada’s governor is also proposing to reduce the number of case management hours allowed per month for certain enrollees and New York’s governor is proposing to eliminate coverage of some over-the-counter (OTC) pharmacy products.

Given that Medicaid serves low-income populations, copayments and premiums in the program are generally limited. States may charge premiums for enrollees with incomes above 150 percent FPL.13 States also may charge cost sharing, but allowable charges vary by income.14 Four governors are proposing new cost-sharing requirements: Ohio’s governor is proposing to impose a premium requirement on childless adults, Wisconsin’s governor would expand the current premium requirement to all disabled adults in its Medicaid Purchase Plan program, New Mexico’s governor is proposing to impose copayment requirements on higher income enrollees, and New York’s governor is proposing to increase copayments amounts for OTC pharmacy products.

Managed care has become the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states, as Medicaid programs have increasingly turned to managed care as a means to help ensure access, improve quality, and achieve budget certainty. A growing number of states are focusing on integration of physical health, behavioral health, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) under the umbrella of managed care. States are also adopting other payment and delivery reforms including patient-centered medical homes, health homes accountable care organizations among others. At least 11 states are proposing new or expanded delivery system or managed care reforms:

- Managed Care. Mississippi (expanding the number of plans), Missouri (expanding statewide) and Pennsylvania (regional expansion) are expanding capitated managed care programs. Oklahoma is implementing a new capitated managed care program.

- MLTSS. New Hampshire is proposing to implement Managed Long Term Services and Supports (MLTSS) and also move 50 percent of Medicaid provider payments to alternative payment models by 2020.

- Behavioral Health. Ohio is proposing to carve-in behavioral health services into managed care. Washington is continuing to invest in behavioral health integration.

- Other. Alaska is implementing a new primary care case management (PCCM) program. Colorado is expanding enrollment in its Accountable Care Collaborative. California is planning to expand its Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System pilot program to additional counties. Oklahoma is updating its Patient Centered Medical Home payment structure to meet the requirements of CMS’ Comprehensive Primary Care Plus Initiative.

One state is reversing a managed care expansion: North Dakota is planning to transition Medicaid expansion adults from capitated managed care back to a fee for service delivery system. Also, California is delaying the transition of California Children’s Services into managed care until July 1, 2018.

Community-Based Long Term Services and Supports

At least 19 governors are proposing to expand the availability of Medicaid community-based long term services and supports (LTSS), continuing a long term trend over the past more than two decades to rebalance services away from institutional care towards care in home and community-based settings. A majority of these governors were specifically targeting home and community-based services (HCBS) expansions for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) (Table 2), including one governor (Alaska) who is proposing to use the 1915(i) State Plan option to refinance services currently provided through the state’s Community Developmental Disabilities Grant program to 969 consumers. Six governors are proposing to expand the number of seniors and persons with disabilities receiving HCBS (Table 2). South Carolina’s governor is proposing to expand HCBS to persons with traumatic brain injuries, and Wisconsin’s governor is proposing to eliminate an HCBS waiting list of 2,200 children with IDD, physical disabilities, and Severe Emotional Disturbances. Washington is planning to implement its recently approved Section 1115 waiver that includes new services and supports for family caregivers who help people stay at home and avoid the need for more intensive services.

Two governors are proposing additional funding for Money Follows the Person initiatives (that help persons return to the community from an institutional placement) (Table 2). One governor (Oklahoma) is proposing continuing a Money Follows the Person program for tribal partners that is working to design an effective and culturally sensitive package of Medicaid community-based LTSS that responds to the unique needs of tribal communities.

| Table 2: Proposed Actions to Expand Community-Based LTSS |

| Expand home and community-based services (HCBS) for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) | AK, CO, CT, FL, GA, MD, MT, NE, NJ, TN, WI |

| Expand the number of seniors and persons with disabilities receiving HCBS | FL, GA, KS, MT, NJ, UT |

| Additional funding for Money Follows the Person initiatives | CO, ND |

Medicaid Administration

A number of states are also proposing a wide array of initiatives to improve or enhance the administration of the Medicaid program. At least four governors are proposing funding for or new eligibility-related enhancements:

- Nebraska and Nevada are implementing new Asset Verification Systems, and Nevada is automating the Medicare Part B Buy-in process (to ensure Medicaid remains the payer of last resort).

- Oregon is proposing eligibility system enhancements to further automate and streamline the determination process.

- Tennessee’s governor is proposing to fund a new eligibility system and expand the number of eligibility determination state workers.

Three states (Colorado, Nebraska, and Oklahoma) are proposing changes to their utilization management (UM) functions. In addition, Nevada’s governor is funding Phase III of its Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS) replacement project, Nebraska is planning to merge the Medicaid and CHIP programs and appropriations to achieve efficiencies, and Pennsylvania is planning to merge multiple departments into one Department of Health and Human Services with the goals of saving money, eliminating duplication, and streamlining delivery of services to seniors, people with IDD, and people battling addictions.

Other proposed administrative improvements include: streamlining accreditation of home health and hospice agencies by recognizing accreditation from CMS approved organizations as evidence for state licensure (Wisconsin); providing school-based claiming assistance to schools (Idaho), implementing a broker contract for non-emergency medical transportation (Michigan), program integrity enhancements (Massachusetts and Oregon), and increasing the reimbursement rate for lead investigations (Wisconsin). Also, California is proposing additional funding to implement the new Medicaid managed care regulations, Virginia is proposing funding to enhance its estate recovery efforts and comply with the recent federal regulation requiring periodic access analyses, and South Carolina is proposing to defund and repeal its Certificate of Need program.

As state policymakers debate state budget priorities and decisions for FY 2018, federal lawmakers are considering major changes to much of the ACA as well as fundamental reforms to the structure and funding of the Medicaid program. With the outcome of the federal debate still uncertain, the proposed state budgets reviewed do not reflect or assume a particular outcome and only a few propose ACA-related changes or reforms:

- The governors’ proposed budgets in North Carolina and Virginia recommend the ACA Medicaid expansion. In Virginia, the proposed budget provides authority for the governor to implement the expansion if enhanced FMAP is available after October 1, 2017.

- Conversely, the governor of Wyoming is not proposing the ACA Medicaid expansion for FY 2018 (despite recommending the expansion in the past), indicating that it would be more prudent to wait and see what actions are taken at the federal level.

- California’s Newly Qualified Immigrant Benefits and Affordability Program would transition coverage of eligible adults without children from state-only Medi‑Cal to a Qualified Health Plan in the Health Benefit Exchange, with Department of Health Care Services providing premium and out‑of‑pocket payment assistance and wraparound benefits not covered by the Exchange plan. California’s governor is proposing that all new qualified adults be included in the wrap program effective January 1, 2018 to ensure that their coverage meets the minimum essential coverage requirements under the ACA.

- Minnesota’s governor is proposing to offer a public option in the Minnesota Marketplace. Governor Dayton’s plan would allow Minnesotans who earn more than 200 percent FPL the opportunity to purchase MinnesotaCare coverage through MNsure.15

- Vermont’s governor is proposing to implement direct enrollment for non-Medicaid clients in Marketplace plans, removing the state as a middle-man between health insurance companies and Vermonters who do not qualify for subsidies.

While not recommending specific actions, governors in Connecticut and Washington referenced potential adverse consequences of ACA repeal and other Medicaid reform proposals. Connecticut Governor Malloy indicated the reductions in federal support would “likely force Connecticut to limit services, to drastically cut coverage to thousands, and as a result, could shift health care provision to inappropriate and more costly venues such as hospital emergency rooms, shelters, and prisons.” Washington Governor Inslee pledged that he would “fight and keep fighting to protect the 750,000 Washingtonians who finally have health insurance, thanks to the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion.” Many Governors have also responded to Congressional requests for input about Medicaid and the ACA.16

Addressing broader public health issues

Initiatives to Fight the Opioid Epidemic

With overdose deaths from prescription opioid pain medications and other narcotics rapidly increasing across the country, many governors are proposing new and expanded Medicaid and non-Medicaid substance use disorder treatment and prevention efforts along with other prescriber monitoring and criminal justice-related initiatives. Over half of the governors’ budgets reviewed cited at least one new priority in this area (Appendix Table 2). Examples include the following:

| Table 3: Examples of Proposed Initiatives to Fight the Opioid Epidemic |

| Alaska | Improve provider access to the state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) by integrating it with the state’s Health Information Exchange. |

| Arizona | Fund five new Medicaid staff positions dedicated to using data analytics to identify needs for member interventions related to opioid misuse or improper opioid prescribing. |

| Indiana | Create the role of Executive Director of Drug Treatment, Prevention & Enforcement to direct all efforts across state government and address the drug epidemic in a targeted and comprehensive manner. |

| Massachusetts | Continue a multi-pronged approach including increased spending for prevention and treatment, funding to investigate fraudulent prescribing practices, expanding heroin and fentanyl trafficking enforcement, funding a statewide campaign to raise awareness of the Good Samaritan law, and funding for student drug diversion and education programs. |

| Minnesota | Proposed $4 million in FY 2018 for prevention grants to reduce the number of opioid overdoses in Minnesota’s American Indian communities. |

| Nevada | Introduce the “Controlled Substance Abuse Prevention Act” to provide more training and reporting and heightened protocols for medical professionals. |

| New Jersey | Multiple proposed initiatives include: create a one-stop website and hotline to access treatment, increase treatment funding, develop curriculum for schools on opioids, and fund college housing for students in recovery. |

| Oklahoma | Enhance public and internal educational opportunities, develop an opioid/heroin task force to address the growing presence and abuse of these drugs, increase inspections of Narcotics Treatment Programs (NTP’s), register 100 percent of all practitioners for the new Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) system who administer, prescribe, or dispense controlled substances, upgrade the security requirements within the new PMP to ensure appropriate use and auditing of the accounts for users of the PMP, implement an initiative to help identify “at risk” persons for prescription drug abuse and provide those persons education and/or drug treatment opportunities, and increase the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Control’s presence in the rural communities of Oklahoma, especially in those areas that are lacking the necessary resources to combat their specific drug issues. |

Initiatives to Enhance Behavioral Health Services

The ACA has dramatically expanded coverage for mental health and substance use disorder services in the United States. In addition to the ACA Medicaid and Marketplace coverage expansions, the ACA also requires all new small group and individual Marketplace plans to cover ten Essential Health Benefit categories, including mental health and substance use disorder services, and requires coverage parity with medical and surgical benefits. These requirements build on the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA, or the federal parity law), which requires group health plans and insurers that offer mental health and substance use disorder benefits to provide coverage that is comparable to coverage for general medical and surgical care.

Proposed state budgets for FY 2018 reflect the growing national focus on behavioral health prevention, treatment, and recovery. In addition to the opioid-related initiatives described above, many states are proposing enhancements to inpatient and outpatient behavioral health delivery systems, including Medicaid-related initiatives as well as enhancements to state and locally-funded programs and facilities (Appendix Table 2). Examples include the following:

| Table 4: Examples of Proposed Initiatives to Enhance Behavioral Health Services |

| Arkansas | New funding for crisis intervention training to help the law enforcement community and others identify mental illness and the help that is needed. |

| Michigan | Proposed budget includes new funding to provide wage increases to support direct care workers who provide critical hands-on supports and services (e.g., personal care services, mobility support) to residents served through Michigan’s community mental health system with the goal or reducing turnover and improving quality. |

| Rhode Island | Proposed $9.9 million to provide low cost housing for people with mental illness. |

| South Carolina | Additional funding to expand school based mental health services for children. |

Other governors proposing initiatives to enhance behavioral health services include:

- Governors in Georgia, Washington, and Wisconsin are proposing new funding for crisis centers: Georgia’s governor would establish a behavioral health crisis center to address emergency crisis needs for individuals with mental illnesses; Washington’s governor would create two new community crisis walk-in centers that allow individuals in mental health crisis to stay up to 23 hours under observation, and Wisconsin’s governor would create an eight bed Crisis Treatment and Stabilization Facility for children to improve outcomes of children in crisis.

- Idaho’s governor is proposing to build an adolescent mental health facility in the Treasure Valley.

- Missouri’s governor is proposing new funding to participate in a federal demonstration program – the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Prospective Payment System Demonstration. The project will develop a system to serve individuals with serious mental illness and substance use disorders while promoting the delivery of efficient and effective care.

- New Hampshire’s governor proposes to increase funding for behavioral health workers by $3 million to strengthen New Hampshire’s community mental health safety net.

- Washington’s proposed budget would overhaul the state’s mental health system and continue investments in behavioral health integration. In addition to short-term investments to address challenges at a state hospital, the state would significantly expand resources to serve people in community settings.

The ACA coverage expansions and mental health parity requirements have also led many states to implement new initiatives targeting persons involved with the criminal justice system with the goal of saving money and reducing recidivism through improved health care coverage and treatment. Proposed budgets in a number of states include new or expanded initiatives in this area (Appendix Table 2). Examples include the following:

| Table 5: Examples of Proposed Health-Related Corrections and Criminal Justice Initiatives |

| Missouri | Create specialty courts focused on nonviolent offenders with mental health or addiction issues with the goal of reducing recidivism rates through treatment (also proposed in Michigan and Nevada), create specialty courts for veterans struggling with mental health and substance use issues. |

| New Mexico | Increased funding in both FY 2017 and FY 2018 to cover a variety of costs including costs associated with the treatment of prisoners with Hepatitis C, transitional living services medical and pharmaceutical contracts, and provision of behavioral health services. |

| Oklahoma | Create bonding authority to build wings on a men’s and a women’s prison for substance abuse offenders and rehabilitation. |

| Rhode Island | Fund new clinical social workers and improve discharge planning for prisoners with behavioral health issues. |

Proposed state budgets also included other health-related proposals, a few of which are described below.

| Table 6: Examples of Other Proposed Health-Related Initiatives |

| Iowa | Create a state-run family planning program while ending taxpayer funding of abortion providers. |

| Ohio | Through a partnership between the Department of Medicaid and the Department of Health, create a new lead abatement program using CHIP funding. |

| Oregon | Provide state-funded health care coverage for children who do not qualify Medicaid solely due to federal citizenship and immigration status requirements. |

| Texas | End Medicaid participation of Planned Parenthood affiliates in the state while maintaining state grant funding for women’s health services at an all-time high ($18 million). |

| Washington | Proposed nearly $120 million to combat homelessness. Budget would increase support services — such as health care and housing assistance — for chronically homeless individuals and families and for youth at risk of becoming homeless. Capital budget would provide funding for more than 1,700 new affordable housing units and to preserve housing. |

Outlook

As state policymakers in most states approach the task of adopting a state budget for FY 2018, they do so against the backdrop of great uncertainty at the federal level regarding health care and federal tax policy. While the AHCA failed to pass in the House, discussions on the ACA and efforts to change the structure and financing of Medicaid are likely to continue at the federal level. Changes to Medicaid as well as other proposed budget and tax changes could have significant implications for state budgets. Without changes to the ACA, Medicaid financing, or tax reform at the federal level, half of states are already facing budget challenges for FY 2018.

Reductions to Medicaid financing would mean states may need to consider raising revenues or reducing spending in other program areas to offset federal reductions or turn to Medicaid program cuts to eligibility, benefits, and reimbursement to providers. Restrictions to Medicaid financing could also have implications for state budgets, providers, and beneficiaries. In addition, these restrictions could limit state efforts to address a variety of public health issues including fighting the opioid epidemic, enhancing behavioral health services, and improving health coverage and treatment for persons involved with the criminal justice system, as the Medicaid program (and the Medicaid expansion) play a key role in all of these areas.