How the Senate Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) Could Affect Coverage and Premiums for Older Adults

Issue Brief

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), adults in their 50s and early 60s were arguably most at risk in the private health insurance market. They were more likely than younger adults to be diagnosed with certain conditions, like cancer and diabetes, for which insurers denied coverage. They were also more likely to face unaffordable premiums because insurers had broad latitude (in nearly all states) to set high premiums for older and sicker enrollees.

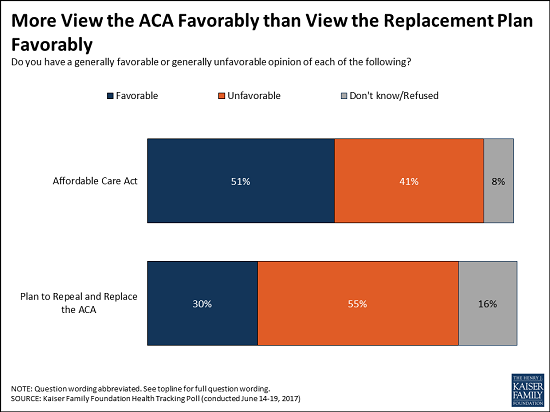

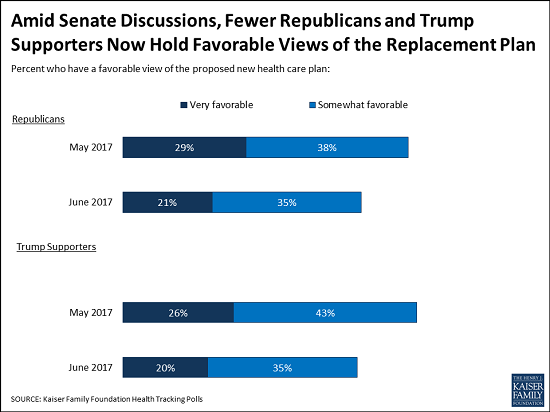

The ACA included several provisions that aimed to address problems older adults faced in finding more affordable health insurance coverage, including guaranteed access to insurance, limits on age rating, and a prohibition on premium surcharges for people with pre-existing conditions. Following passage of a bill to repeal and replace the ACA in the House of Representatives on May 4, 2017, the Senate has released a discussion draft of its proposal, called the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) on June 26, 2017, that follows a somewhat different approach.

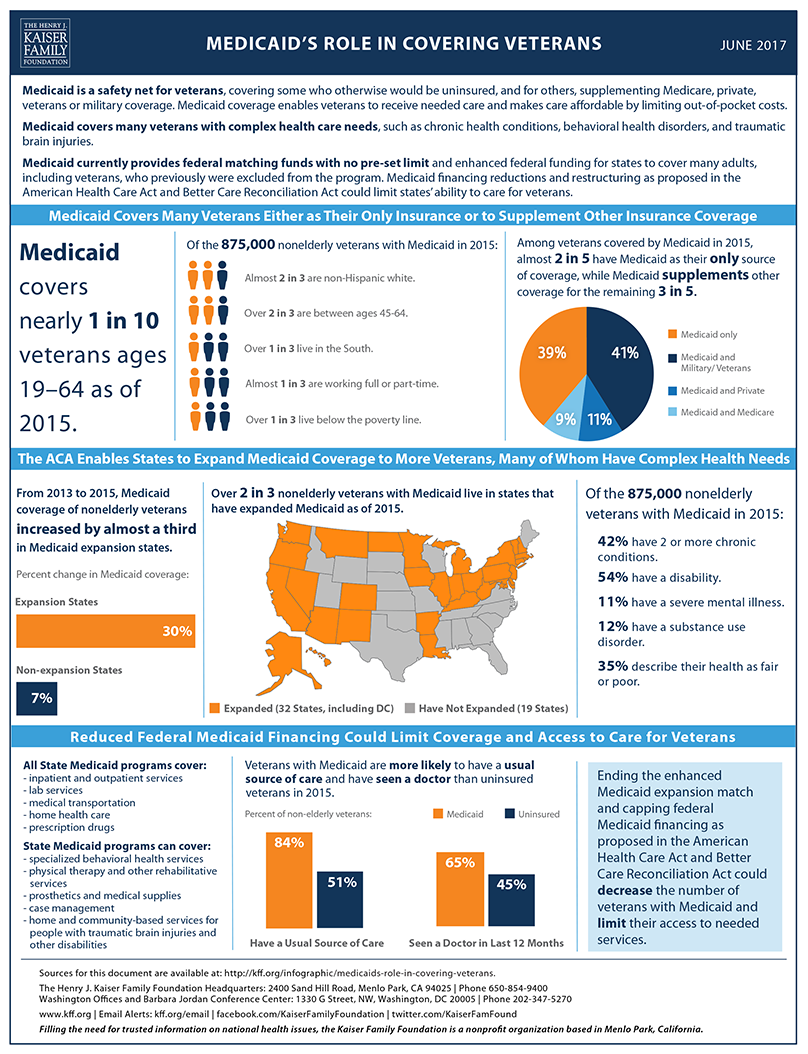

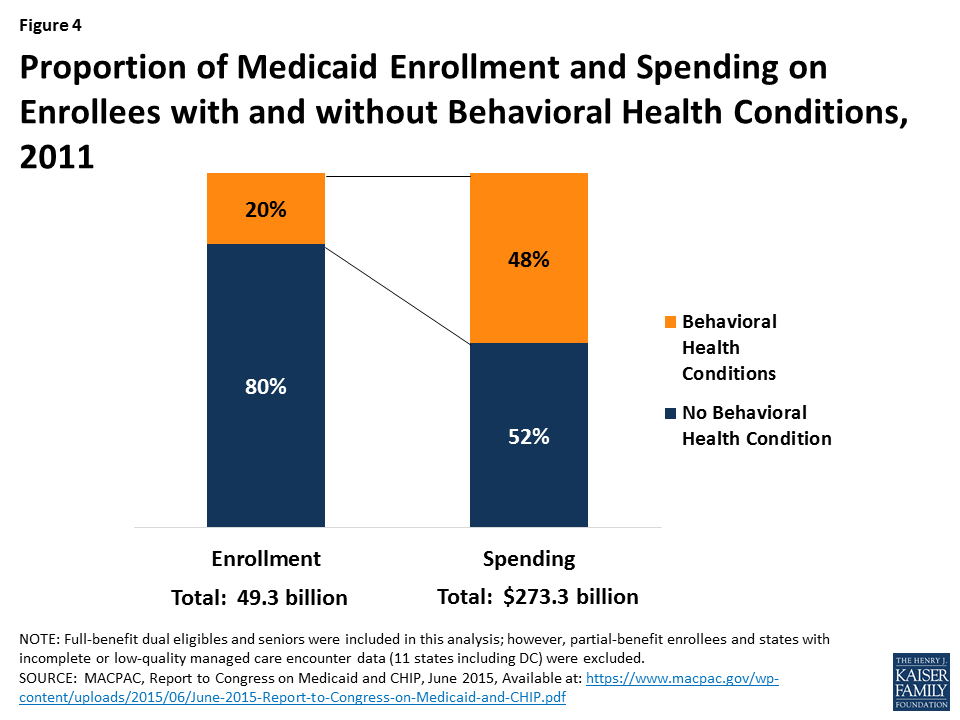

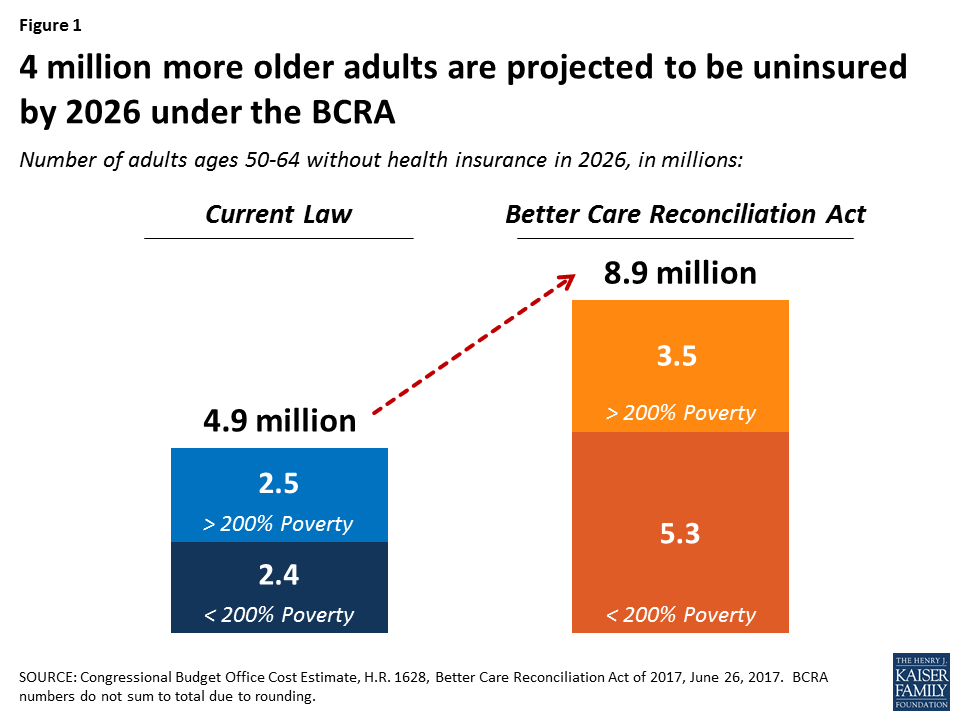

The Senate BCRA discussion draft would make a number of changes to current law that would result in an increase of four million 50-64-year-olds without health insurance in 2026, according to CBO’s analysis (Figure 1).

The Senate proposal would disproportionately affect low-income older adults with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL): three of the four million 50-64-year-olds projected to lose health insurance in 2026 would be low-income. CBO projects the uninsured rate for low-income older adults would rise from 11% under current law to 26% under the BCRA by 2026.

The increase in the number and share of uninsured older adults would be due to several changes made by the BCRA to private health insurance market rules and subsidies, as well as changes to the Medicaid program.

Changes affecting Private Health Insurance

Age Bands. Under current law, insurers are prohibited from charging older adults more than 3-times the premium amount for younger adults. The Senate bill would allow insurers to charge older adults five-times more than younger adults, beginning in 2019. States would have flexibility to establish different age bands (broader or narrower). CBO estimates that age rating would increase premiums significantly for plans at all metal levels for older adults. The impact of age rating would be such that, for a 64-year-old, the national average premium for an unsubsidized bronze plan in 2026 would increase from $12,900 (current law) to $16,000 (BCRA). The wider age bands permitted under the BCRA would result in higher premiums for an unsubsidized bronze plan than the premium for an unsubsidized silver plan under the current law age-rating standard (Table 1).

| Table 1: Estimated National Average Unsubsidized Premiums for Bronze and Silver Health Plans for a 64-year-old, 2026 | ||

| National Avg. Premium, Unsubsidized | ACA Age Bands (3:1) | BCRA Age Bands (5:1) |

| Bronze | $12,900 | $16,000 |

| Silver | $15,300 | $20,500 |

Tax Credits. The Senate’s BCRA makes three key changes affecting premium tax credits for people in the non-group insurance market. First, it changes the income eligibility for tax credits, extending eligibility to people with income below the FPL but capping eligibility at income of 350% FPL. Under current law, income eligibility for tax credits is 100%-400% FPL. This change has the effect of reducing premiums for people with incomes below poverty in the marketplace who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid (discussed further below) while increasing premiums for people with incomes between 350%-400% FPL.

Second, BCRA changes the level of subsidy for people based on age. Under both current law and the BCRA, individuals must pay a required contribution amount, based on income, toward the cost of a benchmark plan; the premium tax credit equals the difference between the cost of the benchmark plan and the required individual contribution. Under current law, the required contribution rate is the same for all people at the same income level regardless of age. However, under the BCRA, the required contribution amount would increase with age for people with an income above 150% FPL. For example, under current law, at 350% FPL, individuals are required to contribute the same percentage of income toward the benchmark plan, regardless of age (9.69% in 2017). Under the BCRA, starting in 2020, a 24-year-old would contribute about 6.4% of income, while a 60-year-old would have to contribute 16.2% of income.1

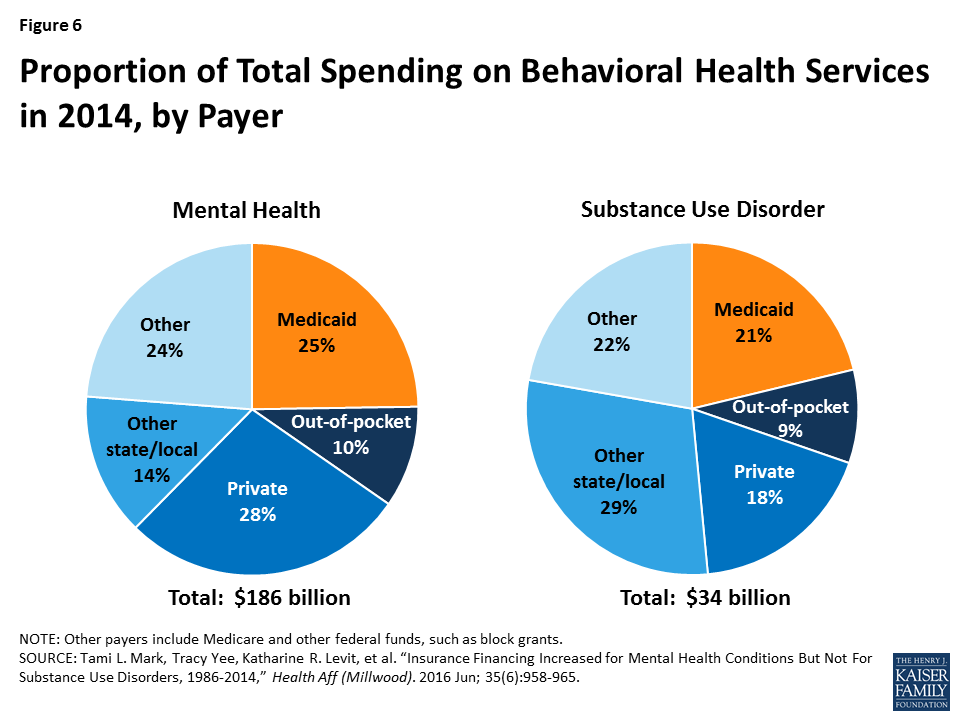

Third, the Senate proposal reduces the value of the benchmark plan used to determine premium tax credits from a more generous silver-level plan (under current law) to the equivalent of a bronze plan (under BCRA). Deductibles under bronze plans are much higher than under silver plans (in 2017, on average, $6,105 for bronze plans vs. $3,609 for silver plans). Under current law, silver plan deductibles are further reduced by cost-sharing subsidies for eligible individuals with incomes below 250% FPL (on average to $255, $809, or $2,904, depending on income). The BCRA eliminates cost-sharing subsidies starting in 2020. As a result, people using tax credits to buy a “benchmark” bronze plan would face significantly higher deductibles under the Senate proposal than under current law.

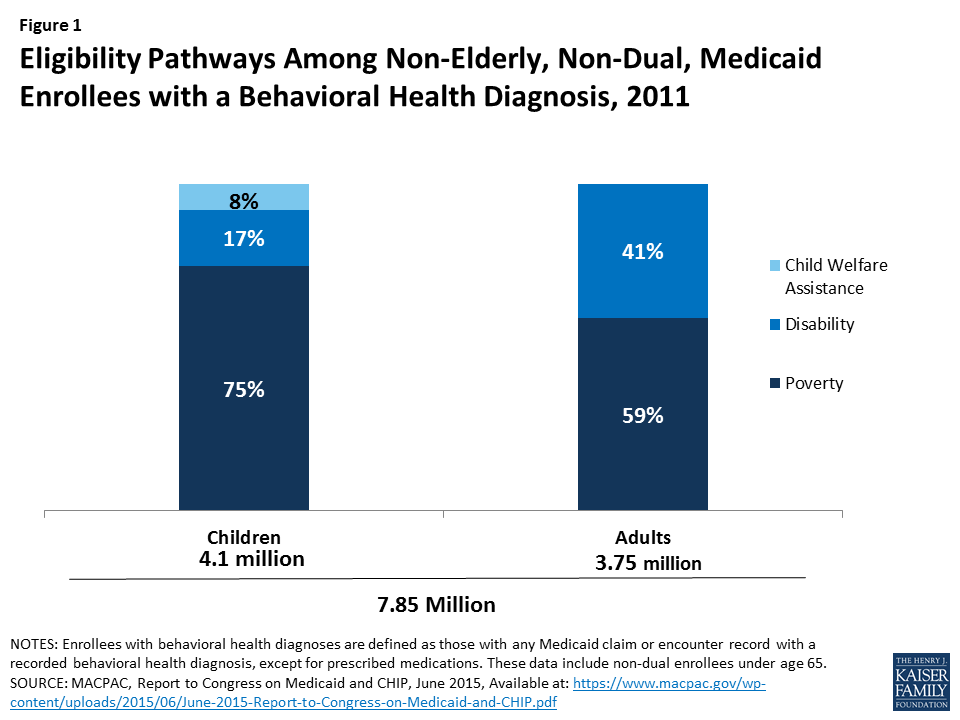

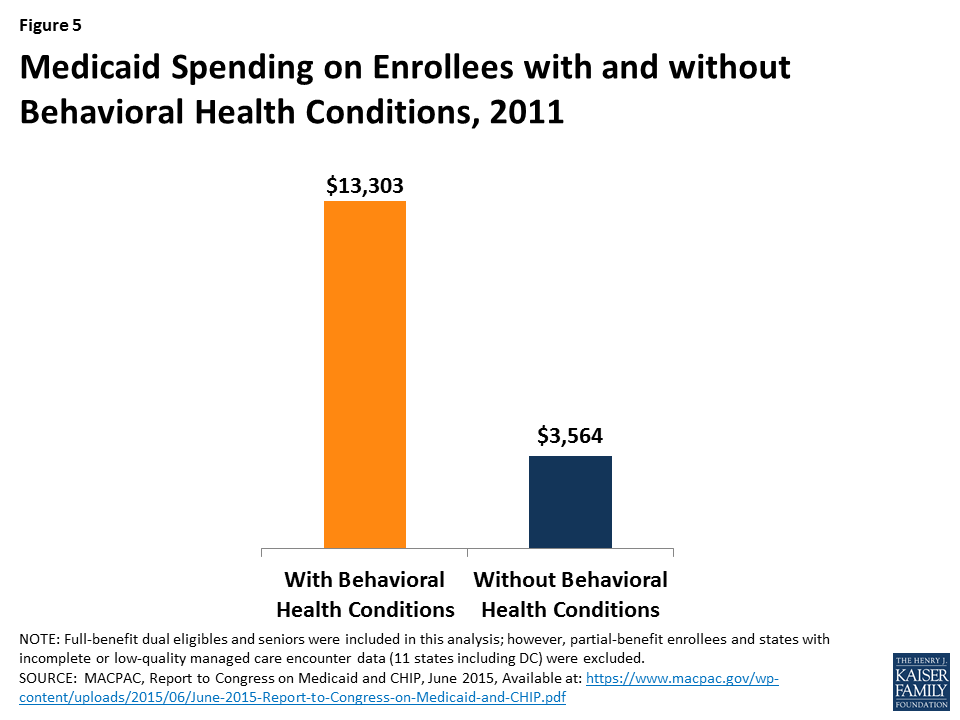

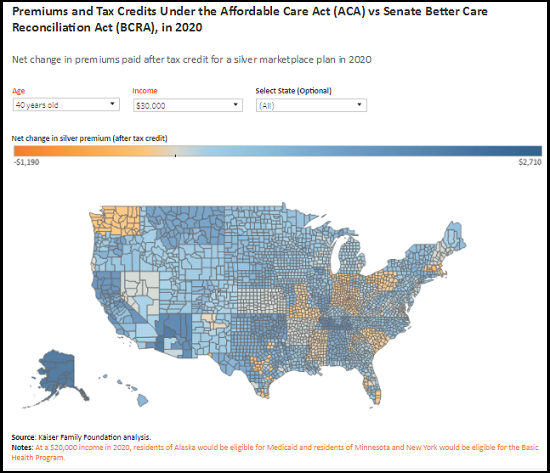

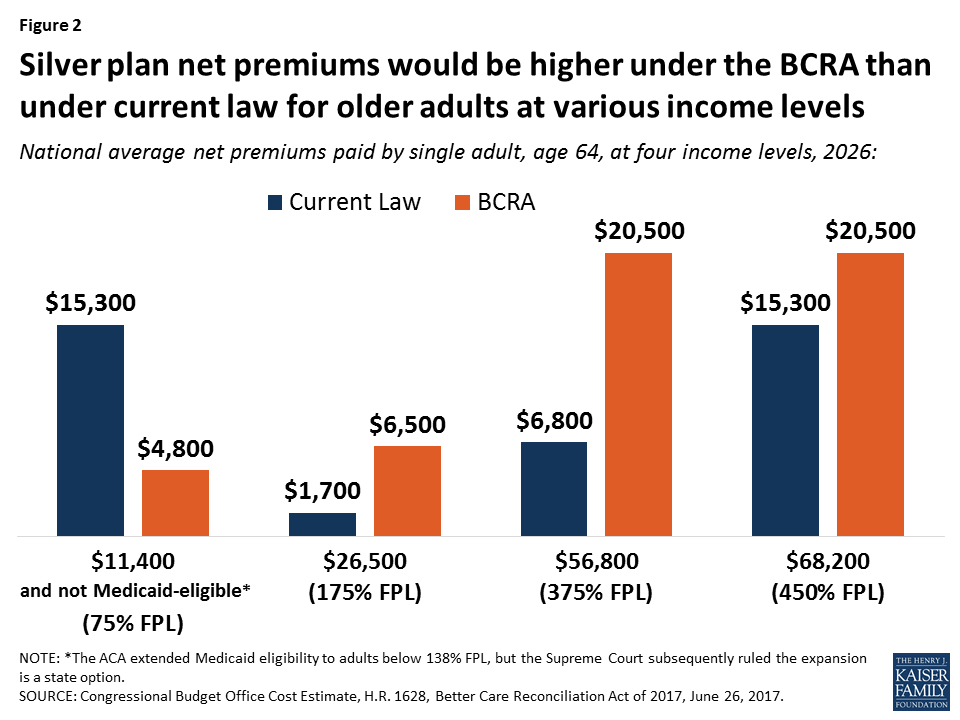

For older adults with income above the poverty level, the combined impact of these changes would be to increase the out-of-pocket cost for premiums at all income levels. For example, a 64-year old with an income of $26,500 would see premiums increase by $4,800 on average for a silver plan in 2026; a 64-year old with an income of $56,800 could see premiums increase of $13,700 in 2026, according to CBO. (Figure 2).

Premium tax credits under the BCRA would continue to be based on the cost of a local benchmark policy, so results would vary geographically. Older adults living in higher cost areas could see greater dollar increases, while people living in lower cost areas could see lower increases.

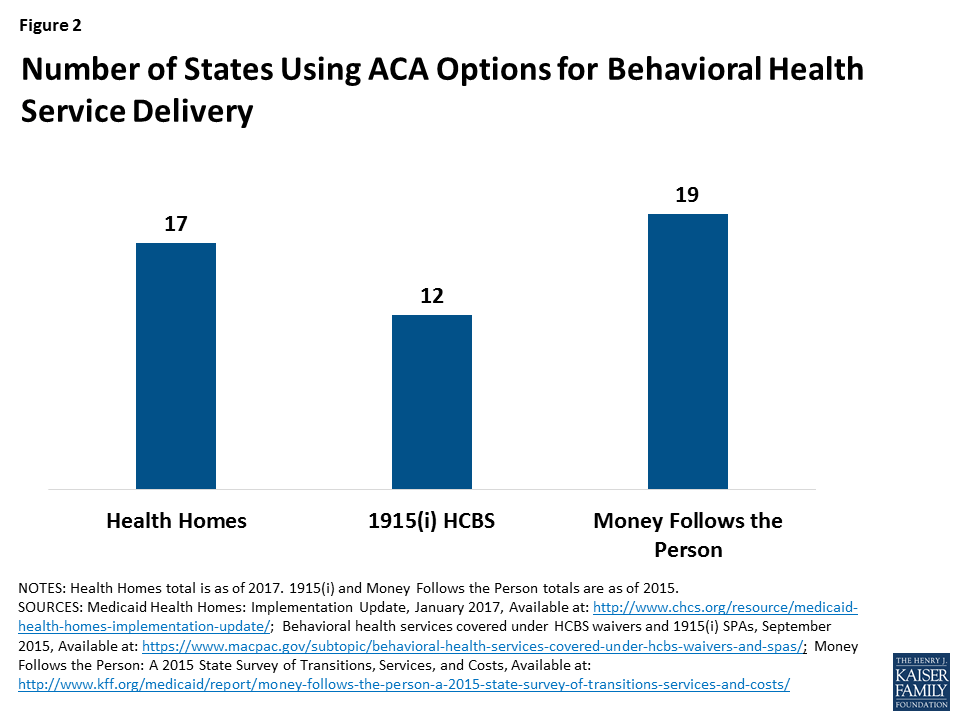

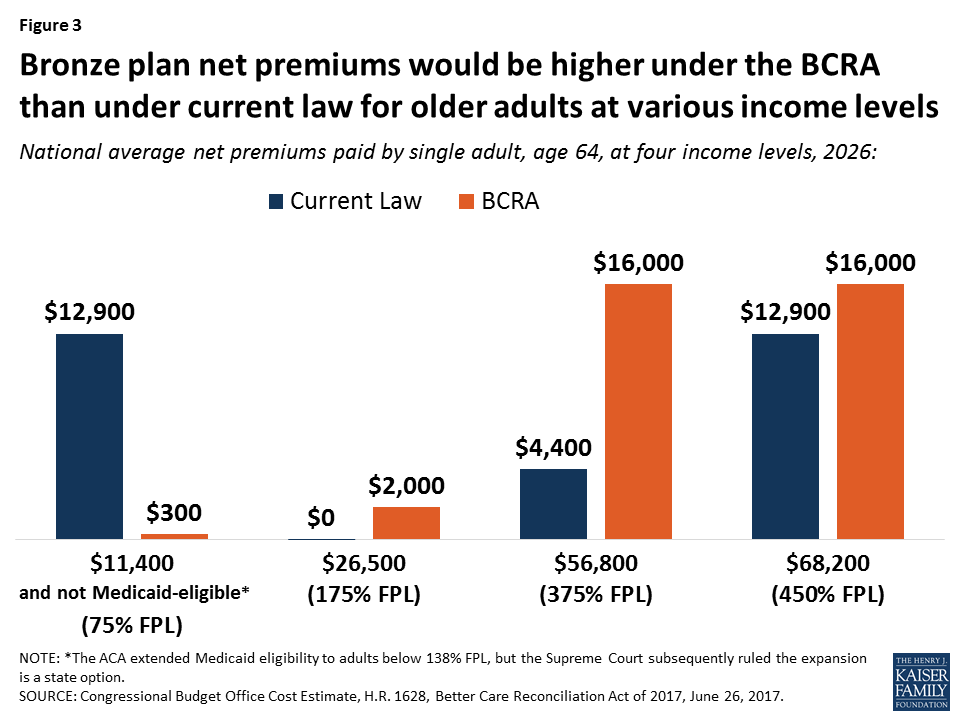

For a bronze plan, the national average premium expense for a 64-year old could increase by $2,000 for an individual with an income of $26,500 in 2026 and by as much as $11,600 for an older adult with $56,800 in income (Figure 3).

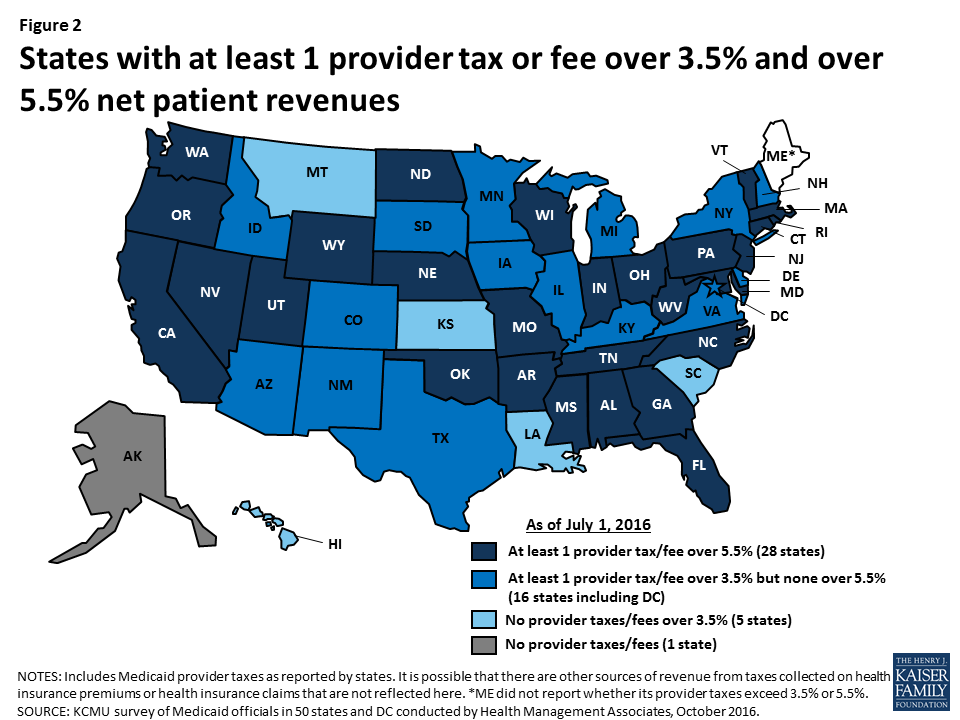

Under current law, people with income below 100% FPL generally are not eligible for premium tax credits. The ACA extended Medicaid eligibility to adults below 138% FPL, but the Supreme Court subsequently ruled the expansion is a state option. To date 19 states have not elected the Medicaid expansion, leaving 2.6 million uninsured low-income adults in this coverage gap.

For older adults with income below 100% FPL who are not eligible for Medicaid, CBO estimates the extension of premium tax credit eligibility will significantly reduce the net premium expense for a 64-year-old in 2026 relative to current law (e.g., by more than $12,000 for an individual at 75% FPL).

However, CBO estimates that few low-income people would purchase any plan. Even with relatively low premiums, older adults with very low incomes may choose to go without coverage due to relatively high, unaffordable deductibles. For example, an individual with an income of $11,400 (75% FPL) who is not eligible for Medicaid, would pay $300 in premiums in 2026 under BCRA but face a deductible in excess of $6,000 – which amounts to more than half of his or her income that year.

On average, 55-64 year-olds would pay 115% higher premiums for a silver plan in 2020 under the BCRA after taking tax credits into account. Low-income 55-64-year-olds would pay 294% higher premiums relative to current law.

Changes to Medicaid

Changes to Medicaid proposed in the Senate bill also contribute to the increase in the projected increase in the number of uninsured older adults nationwide. The BCRA would limit federal funds for states that have elected to expand coverage under Medicaid for low-income adults, phasing down the higher federal match for these expansion states over three years (2021-2023). This provision, coupled with a new cap on the growth in federal Medicaid funding over time on a per capita basis, would result in an estimated 15 million people losing Medicaid coverage by 2026 according to CBO, some of whom are counted among the four million older adults projected to lose health insurance under the BCRA, shown in Figure 1. In 2013, about 6.5 million 50-64-year-olds relied on Medicaid for their health insurance coverage, a number that has likely increased due to the Medicaid expansion.2 Since 2013, Medicaid enrollment overall has grown by nearly 30%.

Impact on Older Adults on Medicare

The loss of coverage for adults in their 50s and early 60s could have ripple effects for Medicare, a possibility that has received little attention. If the BCRA results in a loss of health insurance for a meaningful number of people in their late 50s and early 60s, as CBO projects, there is good reason to believe that people who lose insurance will delay care, if they can, until they turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare, and then use more services once on Medicare. This could cause Medicare spending to increase, which would lead to increases in Medicare premiums and cost-sharing requirements.3

The proposed BCRA changes to Medicaid are also expected to affect benefits and coverage for older, low-income adults on Medicare. Today, 11 million low-income people on Medicare have supplemental coverage under Medicaid that helps cover the cost of Medicare’s premiums and cost-sharing requirements, and the cost of services not covered by Medicare, such as nursing home and home- and community-based long-term services and supports. The BCRA reduces the trajectory of Medicaid spending, with new caps on the growth of benefit spending per person; these constraints are expected to put new fiscal pressure on states to control costs that could ultimately affect coverage and benefits available to low-income people on Medicare. Under the BCRA, the growth in Medicaid per capita spending for elderly and disabled beneficiaries is dialed down to a slower growth rate, from CPI-M+1 to CPI-U beginning in 2025, below currently projected growth rates, just as the first of the Boomer generation reaches their 80s and is more likely to need Medicaid-funded long-term services and supports.

Discussion

The Senate bill to repeal and replace the ACA, known as the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA), if enacted, would be expected to result in an increase of four million uninsured 50-64-year olds in 2026, relative to current law. The increase is due to a number of factors, including higher premiums at virtually all income levels for older adults, potentially unaffordable deductibles for older adults with very low incomes, , and reductions in coverage under Medicaid. Reductions in coverage could have unanticipated spillover effects for Medicare in the form of higher premiums and cost sharing, if pre-65 adults need more services when they age on to Medicare as a result of being uninsured beforehand. The BCRA would also impose new, permanent caps on Medicaid spending which could affect coverage and costs for low-income people on Medicare.

Other changes in BCRA will affect Medicare directly. The BCRA would repeal the Medicare payroll tax imposed on high earners included in the ACA. This provision, according to CMS, will accelerate the insolvency of the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and put the financing of future Medicare benefits at greater risk for current and future generations of older adults – another factor to consider as this debate moves forward.

This issue brief was funded in part by The Retirement Research Foundation.

Endnotes

- The actual applicable percentages would be somewhat higher. The language in the BCRA amends the 2014 required contribution rates outlined in current law. Each year, these percentages have been increased by an inflation factor and would continue to be indexed in the future. By 2020, the actual percentage amounts would be more than the 2014 amounts. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of MSIS data, 2013. ↩︎

- A 2007 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine that looked at previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries helps explain this dynamic. It showed a direct relationship between lack of insurance (pre-65) to higher service use and spending (post-65). Previously uninsured adults were more likely than those with insurance to report a decline in health, and a decline in health (pre-65) was associated with 23.4% more doctor visits and 37% more hospitalizations after age 65. Depending on the number of people who lose coverage and how long they remain uninsured, the impact for Medicare may initially be modest, but could compound with time. ↩︎