Section 1332 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) authorizes states to waive key requirements under the law in order to experiment with different health coverage models. As Republicans in Congress debate repeal and replacement of the ACA, renewed attention is being paid to these waivers as a mechanism for giving states flexibility to restructure their health care markets. The waiver authority is generally broad, though certain process and outcome standards must be satisfied. State interest in 1332 waivers to date has been limited; however, changes to the statutory waiver requirements included in the Senate Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA) or other signals from the Trump administration could spark increased state action. This brief describes current 1332 waiver activity and raises questions regarding the future of these waivers, particularly in the context of proposed changes under discussion.

What Does Section 1332 Allow?

Beginning in 2017, states can request 5-year waivers of certain ACA provisions through Section 1332. States may seeks waivers of requirements related to the essential health benefits (EHBs) and metal tiers of coverage (bronze, silver, gold, and platinum) along with the associated limits on cost sharing for covered benefits. They may alter the premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions, including requesting an aggregate payment of what residents would otherwise have received in premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions. States may also modify or replace the marketplaces and change or eliminate the individual and/or employer mandates (See Appendix A for more detail on these provisions).

The ACA includes guardrails limiting how 1332 waivers can be used by states. The current statutory language requires that state waiver applications must demonstrate that the innovation plan will:

- Provide coverage that is at least as comprehensive in covered benefits;

- Provide coverage that is at least as affordable (taking into account premiums and excessive cost sharing);

- Provide coverage to at least a comparable number of state residents; and

- Not increase the federal deficit.

Additionally, while states can submit ACA innovation waivers in conjunction with Medicaid waivers (under Sec. 1115 of the Social Security Act), innovation waivers cannot be used to change Medicaid program requirements.

In 2012, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued final regulations outlining the procedures for state innovation waiver applications. In 2015, HHS and the Treasury Department issued guidance on how they would interpret the law’s requirements for waivers to provide for comparable coverage, comprehensiveness, affordability, and budget neutrality. Unlike regulations and statutes, guidance is not legally-binding, and therefore, can be more easily changed by subsequent administrations.1 On his first day in office, President Trump issued an executive order suggesting that states would be given increased flexibility with regard to ACA implementation.

The 2015 guidance offered a fairly strict interpretation of the statutory guardrails for 1332 waivers. It emphasized the need to protect access to care and affordability for vulnerable populations, including the poor, the elderly, and those with high health needs and risks, noting that impacts on these populations would be considered in assessing whether any waiver met the statutory guidelines. The guidance also specified that coverage and affordability would be measured annually as well as over the life of the waiver and that comprehensiveness of coverage would evaluate coverage under all ten essential health benefit (EHB) categories and under any one EHB category. In calculating deficit neutrality, states cannot use savings from a separate 1115 waiver to offset spending under a 1332 waiver, and any changes in the cost of Medicaid that might result from a waiver would also be measured. Finally, with respect to waiver administration, the guidance noted that to the extent waiver programs envision new methods for determining eligibility for or delivering subsidies, states would need to build their own systems and could not rely on IRS or HHS to customize operations of healthcare.gov or the federal tax system to accommodate individual state programs.

State Innovation Waiver Activity

To date, 1332 waiver activity has been somewhat limited. Six states (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Iowa, Minnesota, and Vermont) have submitted waiver applications, and only Hawaii’s waiver has been approved. Waivers submitted by Hawaii and Vermont are fairly narrow in scope focusing on maintaining existing coverage requirements or enrollment procedures in the small group market. California’s proposal, which sought to expand coverage options for undocumented immigrants by allowing them to purchase coverage through the state’s marketplace without premium subsidies, was withdrawn following the November election. More notable are the waiver applications submitted by Alaska, Iowa, and Minnesota. Although they take different approaches, all three states are seeking to stabilize fragile individual markets. The Alaska waiver proposal is currently under review, but has received initial support from both the Obama and Trump administrations. Minnesota passed legislation to implement a market stabilization approach similar to Alaska’s, and submitted its waiver application at the end of May. Iowa’s waiver proposal includes a reinsurance program similar to the program adopted in Alaska, but also proposes broader changes to the individual market. Both Iowa and Minnesota have requested expedited review by the Trump administration to implement the proposed changes for 2018.

Below is a description of submitted waivers (Table 1).

| Table 1: Submitted 1332 Waivers |

| State | Description | Status |

| Alaska | Allow federal pass through funding to partially finance the state’s reinsurance program. The waiver requests that funds the federal government would have paid in premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions to eligible marketplace enrollees had the reinsurance program not been in place be provided directly to the state to be used to finance the program. | Under review |

| California | Allow undocumented immigrants to purchase coverage through the state’s marketplace, Covered California, without premium subsidies. | Withdrawn |

| Hawaii | Retain the employer coverage provisions currently in place through the state’s Prepaid Health Care Act, which was enacted in 1974. The law requires employers to provide more generous coverage than is required under the ACA. The state also sought to waive the requirement that the small business tax credits only be available through the SHOP. | Approved 12/30/16 |

| Iowa | Create a Proposed Stopgap Measure plan that would be the only plan offered in the marketplace; replace advanced premium tax credits with flat premium subsidies based on age and income and eliminate cost-sharing subsidies; and establish a reinsurance program. Federal pass through funds would finance the new premium subsidies and the reinsurance program. | Submitted 6/12/17 |

| Minnesota | Create a new state reinsurance program to be funded with a combination of federal pass through funds and state appropriations. The waiver requests that funds the federal government would have paid in premium tax credits and cost sharing reductions to eligible marketplace enrollees had the reinsurance program not been in place be provided directly to the state to be used to finance the program. | Submitted 5/30/17 |

| Vermont | Continue to allow small employers to enroll directly with health insurance carriers rather than through an online SHOP web portal. The state had adopted the direct enrollment approach for small businesses after the SHOP portal developed by the state failed to launch in 2014. Recent guidance from CMS delaying the required implementation of the SHOP portal until 2019 puts off for now the need for Vermont’s waiver. | On hold |

Looking Ahead

Many uncertainties remain over the future of 1332 waivers—whether the waiver authority will be changed legislatively, how the Trump administration will interpret the requirements, as well as how states will seek to use 1332 waivers to redesign their health coverage systems. Questions include:

How would the BCRA change 1332 waiver authority?

The BCRA would make several consequential changes to the requirements for 1332 waivers and the process for submitting and approving state waiver applications. While the BCRA does not change the ACA provisions that states may seek to waive, it eliminates three of the four current law requirements that states must meet in order to receive approval. These include the requirements that the waivers cover as many people, provide coverage that is at least as comprehensive and provide coverage that is at least as affordable. In place of these requirements, states would need only to include in their waiver applications a description of how the proposal would provide alternative ways to address these issues. At the same time, the BCRA would remove the Secretary’s discretion to deny waivers. Instead, the Secretary would be required to approve any waiver as long as it did not increase the federal deficit. The BCRA would also require the Secretary to establish an expedited review process and would extend the waiver period from five years to eight years and permit unlimited renewals.

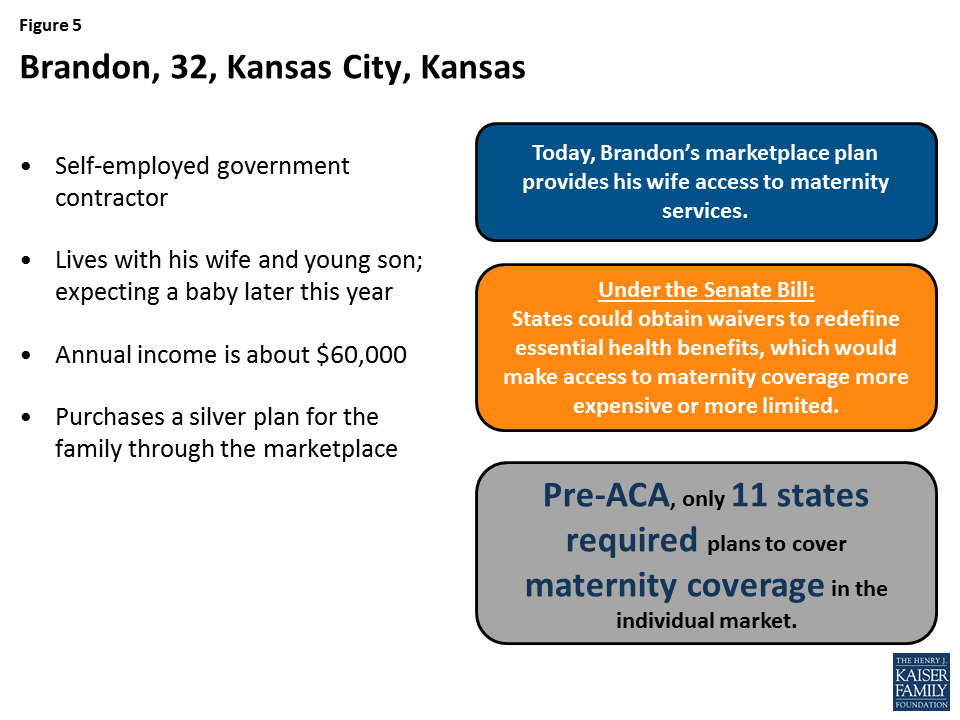

These changes, if adopted, would have far-reaching consequences. Given the increased flexibility afforded states and the continued ability to receive pass through funding of any federal payments that would have been paid to state residents if the waiver had not been in place, it is expected more states would seeks waivers than under current law. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that by 2026 about half the population would be in states receiving waivers and most states receiving waivers would use the waiver authority to reduce the scope of the EHBs. The impact of these waivers would vary from state to state, and would depend on many factors, including how the EHBs are redefined, whether pass through funds are used to lower premiums or cost sharing, and whether other measures are put in place to improve market stability. The CBO projects that, in general, premiums would be lower and out-of-pocket costs would be higher in states adopting waivers due to the narrowing of the scope of EHBs. While the CBO estimates little impact overall on the number of people with health insurance, it notes that some states may adopt policies that reduce the number of people with insurance. This situation would result if states provided more assistance to those who would have purchased coverage in the absence of any subsidies or if states reduced subsidies then used pass through funds for purposes unrelated to health coverage.

Earlier this year, the American Health Care Act (AHCA), passed by the House of Representatives on May 4, 2017, included a provision granting additional waiver authority to states to opt out of ACA market reforms, including the requirement to provide the ten EHBs and the prohibition on insurers charging people based on pre-existing conditions. While the requirement to cover EHBs can be waived under current 1332 authority, waiving the community rating provision is not permitted. Notably, the BCRA does not allow waivers of community rating. The House provision would have created a new waiver authority separate from the 1332 waiver authority and without the statutory conditions that now have to be met.

how Will the current administration interpret 1332 waiver authority?

Even if statutory changes to 1332 waivers are ultimately not adopted, the Trump administration can interpret 1332 waiver authority in ways that differ from the Obama administration. Although the nonbinding 2015 guidance remains in place, the administration can issue new guidance signaling a new direction in how 1332 waivers will be evaluated. Prior to the latest legislative developments, in March 2017, Secretary Price issued a letter to states reiterating the law’s key requirements for 1332 waivers and offering states assistance in the development and implementation of innovation programs. The March letter especially encouraged states to design proposals that include high-risk pools or state-operated reinsurance programs as a strategy to lower health insurance premiums and promote market stability, and specifically highlighted the reinsurance program established in Alaska as a potential model for other states.

Notably, the March 2017 HHS letter reiterated the current statutory guardrails for 1332 waivers, but did not signal how the administration would interpret those guardrails. A more accommodating approach to assessing whether waivers meet the statutory requirements could provide states with more flexibility to make changes using the 1332 authority. As an example, the ACA requirement to maintain coverage for a comparable number of state residents, could be achieved if some residents with high-cost conditions lose coverage at the same time a larger, offsetting number of lower-cost residents gain coverage.

The Iowa waiver may pose a unique challenge for the Administration. Although Iowa is using the Section 1332 waiver process, it notes several times in the application that it is seeking “emergency regulatory relief” to respond to the current market situation. Citing the Trump administration’s executive order, the state requests an expedited review of the proposal and an exemption from compliance with the process requirements related to submission of 1332 waiver applications, including required data and analysis showing the 10-year budget impact and public process requirements, among others. While the BCRA would establish an expedited review process, current regulations do not provide for such a process. How the administration responds to this request may signal whether it views 1332 waivers as an appropriate mechanism for responding to the urgent situation a number of states are facing.

How will states use 1332 waivers in the future?

Few states have, to date, signaled an interest in using 1332 waivers to make broader changes to their health care markets. In response to a letter from Republican leaders in the House of Representatives sent to governors and insurance commissioners last December requesting their views on changes to the ACA broadly, and plans related to 1332 waivers specifically, only seven respondents out of 35 indicated they are or would consider pursuing a 1332 waiver. Among these seven states, Kentucky, Minnesota, and Oklahoma, have authorizing legislation supporting the development of a 1332 waiver.2 However, recent insurer exits from several state marketplaces along with ongoing uncertainty over the future of the marketplaces may compel more states to turn to 1332 waivers to stabilize these markets.

The Alaska approach to stabilizing its individual insurance market may serve as a model to other states. The 1332 waiver proposal requests federal pass through funding to finance the state’s Alaska Reinsurance Program (ARP), established in 2017 in response to expected premium increases of 42% by the state’s single marketplace insurer. Due to lower premium increases (the actual premium increase in 2017 was 7%), the state estimates future savings to the federal government in reduced advanced premium tax credit payments (APTC). It proposes to use the federal savings, paid to the state in the form of pass through funding, to finance in part the ARP.

Following announcement of the Alaska waiver proposal, the Minnesota legislature enacted legislation to establish a reinsurance program, the Minnesota Premium Security Plan (MPSP), using Section 1332 authority. In its waiver proposal, Minnesota requests federal pass through funding from APTC savings to finance the reinsurance program. The state targets $271 million in funding for the MPSP in 2018 and anticipates a 20% reduction in average premiums.

In contrast to Alaska and Minnesota, which would continue to deliver coverage and subsidies as outlined in the ACA, Iowa is seeking to alter several ACA requirements in more substantive ways. Facing the possibility of having no insurers participate in the marketplace in 2018, the state proposes several changes to the insurance marketplace, including:

- Creating a single Proposed Stopgap Measure (PSM) plan that would be the only plan offered by insurers in the marketplace; the PSM would provide coverage similar to that offered under the standard silver marketplace plan today;

- Replacing the existing APTCs with flat premium subsidies based on age and income and eliminating the cost-sharing reductions; and

- Establishing a reinsurance program to protect insurers from high-cost cases.

The state is requesting federal pass through funding equal to what the federal government would have paid in APTCs and cost-sharing reductions in 2018. It estimates the cost of the premium subsidies to be $220 million, leaving $80 million to fund the reinsurance program.

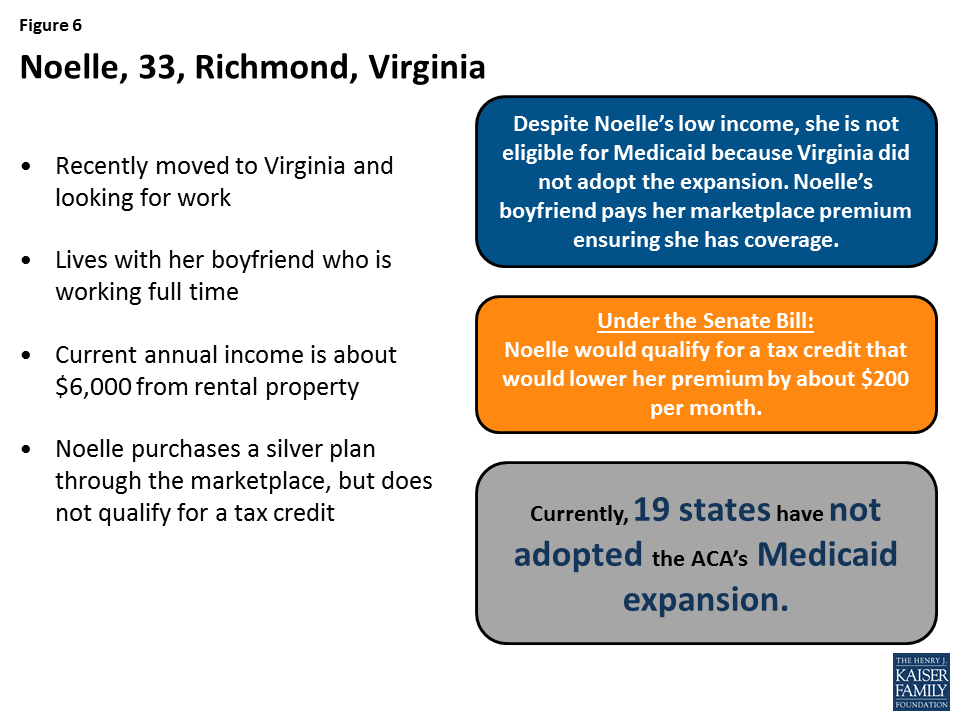

Looking further down the road, task forces in Minnesota and Oklahoma have issued reports providing recommendations for using 1332 waivers to develop alternative approaches to ACA coverage requirements. The Minnesota Task Force recommends broadening the state’s Basic Health Program, MinnesotaCare, to serve as a public option in the state’s marketplace. The Oklahoma 1332 Waiver Task Force report envisions using waiver authority to achieve greater state control over the determination of essential health benefits, health plan design, and enrollment procedures as well as changes to the eligibility for and structure of premium subsidies. Beyond these specific proposals, states might seek waivers to deliver coverage through products or programs, such as short term, non-renewable policies, or health sharing ministries that are not subject to ACA requirements on insurers to guarantee issue coverage, community rate premiums, and cover pre-existing conditions. While these types of sweeping changes would still need to meet the conditions for 1332 waivers laid out in current law, a looser interpretation of these guardrails may permit approval of some of these changes.

As discussed above, passage of the BCRA would likely lead to more states developing waiver proposals. In addition, under the BCRA, states with submitted waivers under consideration as of the date of enactment could choose to have their waivers evaluated under the new BCRA rules. However, aside from the expectation that more states would seek to use 1332 waivers to redefine the EHBs, it is difficult to anticipate what other changes they might pursue.

Will states be granted more flexibility to use 1332 and 1115 waivers in combination?

The 2015 guidance from the Obama administration clearly stated that while a state could submit a coordinated 1332 and 1115 waiver application, the two waivers would be evaluated independently. However, the Trump administration could relax these standards and permit the waivers to be considered in concert. Joint review of 1332 and 1115 waivers would likely provide states with enhanced flexibility around deficit neutrality, allowing savings in one program to offset spending on another. The extent to which states may be interested in developing combined 1332 and 1115 “super waivers” remains to be seen. However, a recent letter from Secretary Price to state Governors signaling support for using 1115 waivers to “align Medicaid and private insurance policies for non-disabled adults” may encourage states to pursue combined waivers to achieve broader changes in their health coverage systems. Passage of the BCRA may further encourage states to consider developing combined waivers.