Health Plan Enrollment in the Capitated Financial Alignment Demonstrations for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries

As of July 2017, nearly 400,000 beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were enrolled and receiving services from health plans in 10 states with capitated financial alignment demonstrations. These demonstrations, jointly managed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the participating states, seek to maintain or decrease costs while maintaining or improving health outcomes for this vulnerable population of seniors and non-elderly people with disabilities. This fact sheet provides a snapshot of enrollment in the demonstrations by state, as of July 2017. Key facts include the following:

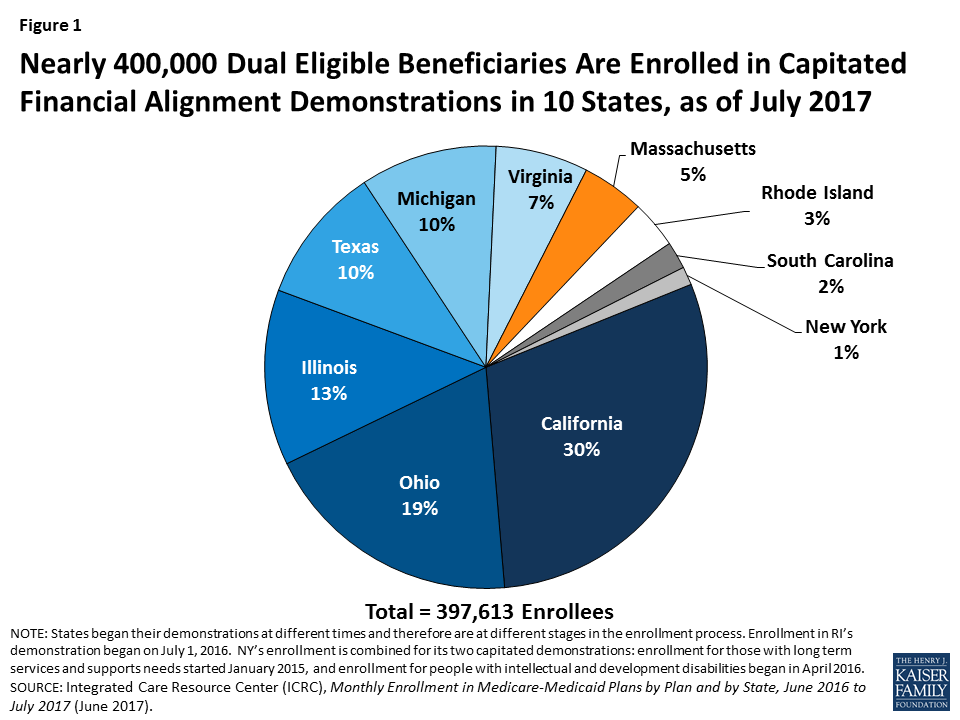

There were nearly 400,000 dual eligible beneficiaries enrolled in capitated financial alignment demonstrations in 10 states as of July 2017 (Figure 1). These states include California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia. All states that currently have demonstrations approved by CMS have enrolled beneficiaries. The final state, Rhode Island, began enrollment in its capitated demonstration on July 1, 2016. In addition, Colorado and Washington have beneficiaries enrolled in managed fee-for-service (FFS) demonstrations, and Minnesota is implementing an administrative alignment demonstration using Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries.

At least two states (Colorado and Virginia) are planning to discontinue their demonstrations at the end of 2017. Colorado beneficiaries will transition from the demonstration to the state’s managed FFS accountable care collaborative program without any changes in benefits. Virginia beneficiaries will transition to mandatory Medicaid capitated managed long-term care health plans and have the option to receive their Medicare benefits through a Medicare Advantage health plan or Medicare fee-for-service.

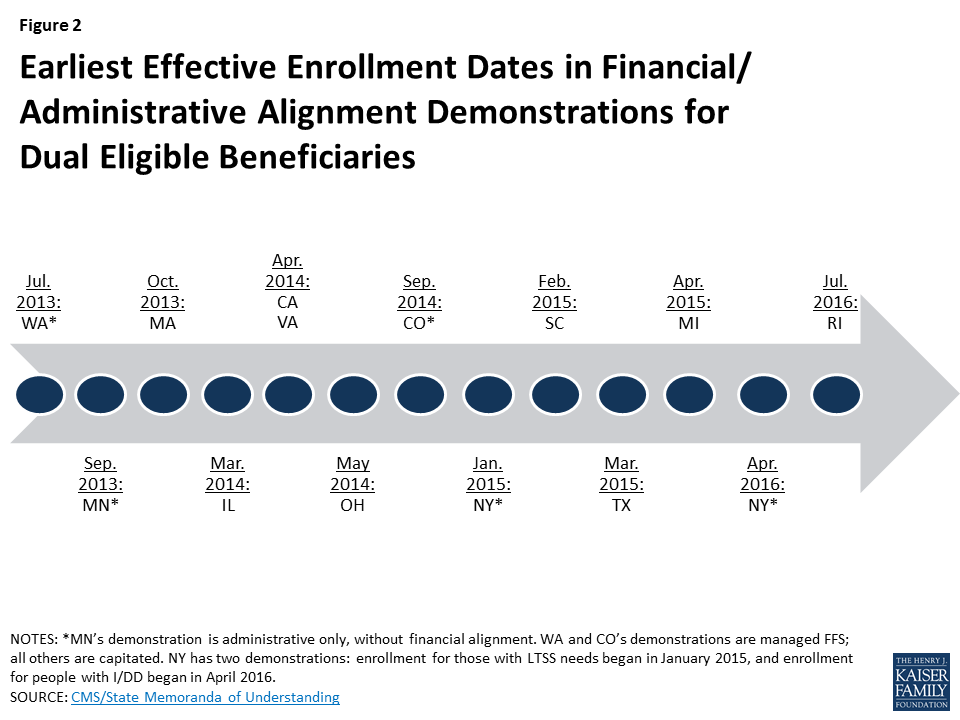

As of July 2017, California’s demonstration had the largest enrollment, comprising nearly one-third (over 118,000) of current enrollees, followed by Ohio, Illinois, Texas, Michigan, Virginia, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and New York (Figure 1). These states’ demonstrations have been in effect for different lengths of time, with Massachusetts first enrolling beneficiaries in October 2013 and Rhode Island beginning voluntary enrollment in July 2016 (Figure 2). The states also vary in the number of waves of passive enrollment and the methods used to phase-in enrollment.

As of July 2017, out of 63 health plans participating in the demonstrations, nine plans (or their parent companies) were enrolling beneficiaries in more than one state’s demonstration (Table 1). These nine are Aetna, Anthem, Centene, Cigna, Humana, Independence Health Group, Meridian, Molina, and UnitedHealth Group. Among these companies, Molina has the most enrollees (54,000 beneficiaries in six states), followed by Anthem (33,000 beneficiaries in three states), Centene (32,000 beneficiaries in five states), Aetna (31,000 beneficiaries in four states), UnitedHealth Group (19,000 beneficiaries in two states), Humana (16,000 beneficiaries in two states), Meridian (13,000 beneficiaries in two states), Independence Health Group (7,000 beneficiaries in two states), and Cigna (6,000 beneficiaries in two states), as of July 2017. The number of health plans from which beneficiaries can choose varies by county or region in each state’s demonstration. In addition, whether all health plans are participating in all the demonstration regions/counties within each state or only in selected geographic areas also varies by state.

Looking Ahead

As some states begin winding down their demonstrations, other states may opt to extend their models. The demonstrations initially were approved for three years, but CMS subsequently offered states two year extensions to provide additional time and data for the demonstrations’ evaluations. Some early federal evaluation results have been released, including reports on the initial six months of implementation; the demonstrations’ impact on special populations such as people who use long-term services and supports, those with behavioral health needs, and linguistic, ethnic, and racial minorities; care coordination; and beneficiary experience, along with reports specific to Massachusetts and Washington. Delays in the availability of data required to fully understand the impact of the demonstrations led CMS to offer an additional two year extension to Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Washington, the first three states to have implemented a demonstration in 2013; these extensions would change the demonstration end date from December 2018 to December 2020. As additional information becomes available, CMS, states, beneficiaries, health plans, providers, and other stakeholders will be interested to learn whether the demonstrations have improved health outcomes, how the demonstrations have affected state and federal costs, and whether the models will be expanded.

| Table 1: Enrollment in Health Plans Participating in More Than One State’s Financial Alignment Demonstration, as of July 2017 | |||||||||||

| Health Plan/ Parent Company | CA | IL | MA | MI | NY | OH | RI | SC | TX | VA | Totalenrollment |

| Aetna | 7,100 | 7,700 | 100 | 16,200 | 31,000 | ||||||

| Anthem | 7,000 | 13,600 | 12,200 | 33,000 | |||||||

| Centene | 6,500 | 2,400 | 12,400 | 2,200 | 8,500 | 32,000 | |||||

| Cigna | 4,400 | 1,300 | 6,000 | ||||||||

| Humana | 6,400 | 9,200 | 16,000 | ||||||||

| Independence Health Group | 3,400 | 3,800 | 7,000 | ||||||||

| Meridian | 6,800 | 5,800 | 13,000 | ||||||||

| Molina | 12,300 | 3,800 | 11,000 | 13,200 | 1,900 | 12,200 | 54,000 | ||||

| UnitedHealth Group | 14,400 | 4,500 | 19,000 | ||||||||

| Other health plans | 99,100 | 16,000 | 18,200 | 9,500 | 5,300 | 20,100 | 13,800 | 5,500 | 187,000 | ||

| Total enrollment by state | 118,000 | 51,000 | 18,000 | 40,000 | 5,000 | 76,000 | 14,000 | 8,000 | 40,000 | 27,000 | 398,000 |

| NOTES: Health plans may operate under different names in individual states. Blank cells indicate that selected health plans are not participating in the demonstration in that state. All data have been rounded, and totals may not sum due to rounding.SOURCE: Integrated Care Resource Center (ICRC), Monthly Enrollment in Medicare-Medicaid Plans by Plan and by State, June 2016 to July 2017 (June 2017), http://www.integratedcareresourcecenter.com/PDFs/MMP_Enroll_by_State_July_2017.pdf. | |||||||||||