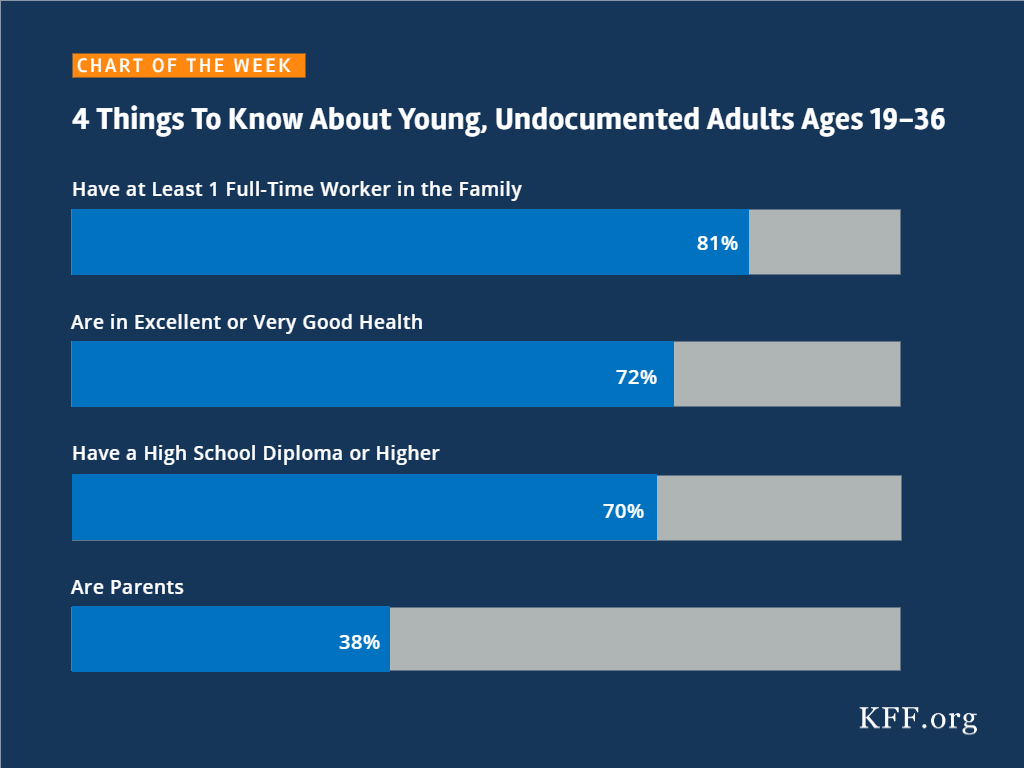

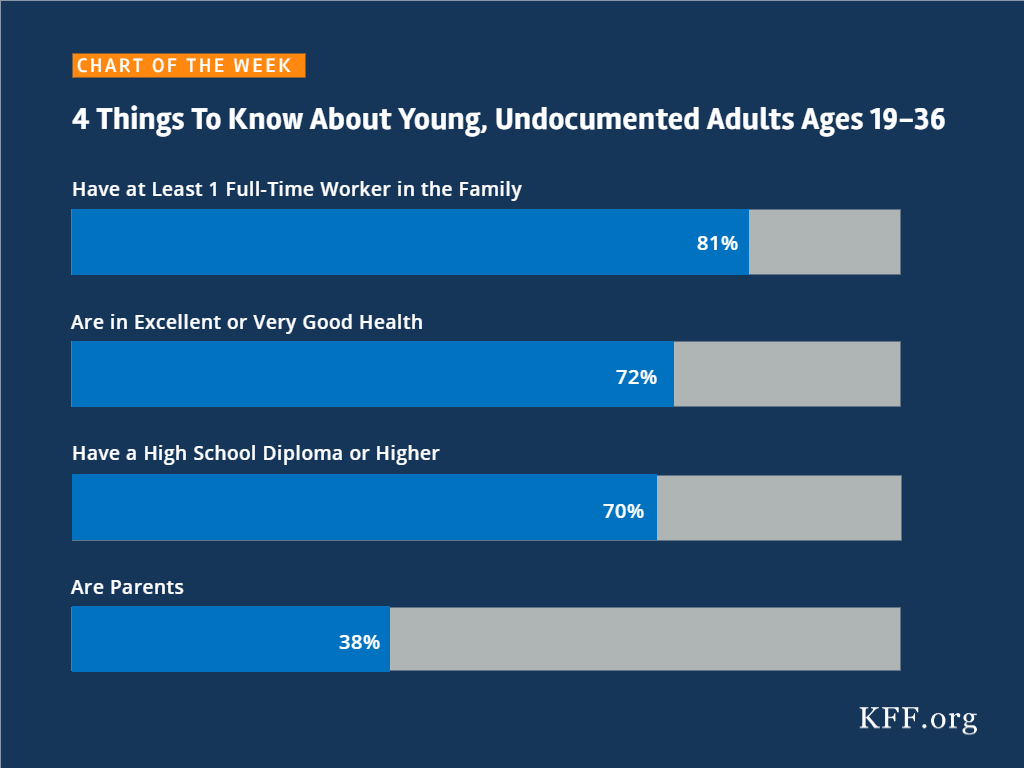

4 Things To Know About Young, Undocumented Adults Ages 19-36

Source

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2017 Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2017 Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement

On January 22, 2018, Congress passed a six-year extension of CHIP funding as part of a broader continuing resolution to fund the federal government. Federal funding for CHIP had expired on September 30, 2017. Without additional funding available, states operated their CHIP programs using remaining funds from previous years. However, some states came close to exhausting funding, leading them to make contingency plans to reduce coverage and notify families of potential coverage reductions. In late December 2017, Congress provided some short-term funding for early 2018, but some states still expected to exhaust funds by March 2018. The six-year funding extension provides stable funding for states to continue their CHIP coverage. This fact sheetprovides a summary of key provisions of the CHIP funding extension (Table 1). In sum, it:

What’s in the #CHIP funding extension passed by #Congress?

| Table 1: Key Provisions of the HEALTHY KIDS Act (H.R. 195, Division C) | |

| CHIP Funding | Extends federal CHIP funding for 6 years, from FY2018 through FY2023. Makes some adjustments to avoid duplicate payments given the short-term federal funding provided for the first quarter of FY2018. Extends Child Enrollment Contingency Fund payments for states with a funding shortfall and CHIP enrollment exceeding a state-specific target level. Extends the qualifying states option that allows states that expanded Medicaid before CHIP was created in 1997 to receive CHIP matching funds for some children enrolled in Medicaid. |

| Federal Match Rate | Continues the 23 percentage point CHIP enhanced federal match rate established by the Affordable Care Act for FY2018 and FY2019, decreases it to 11.5 percentage points in FY2020, and returns to the regular CHIP match rate for FY2021through FY2023. |

| Express Lane Eligibility | Extends authority for states to rely on findings from agencies such as those that administer TANF or SNAP for initial Medicaid/CHIP eligibility determinations and renewals through FY2023. |

| Maintenance of Effort | Extends states’ maintenance of effort requirements to maintain coverage for children from FY2019 through FY2023. After October 1, 2019, the maintenance of effort requirement would only apply to children in families with incomes at or below 300% FPL. |

| Demonstration Project Funding | Extends federal funding for the childhood obesity demonstration project and pediatric quality measures program for FY2018 through FY2023. |

| Outreach and Enrollment Funding | Extends federal funding for CHIP outreach and enrollment grants from FY2018 through FY2023. Specifies that organizations that utilize parent mentors are able to receive grant funding and that any income or stipend a parent receives through this grant funding should not be considered in Medicaid eligibility determinations. |

| CHIP Risk Pools | Allows states to include CHIP children and those in look-alike programs in the same risk pool and specifies that CHIP look-alike programs qualify as minimum essential coverage. Look-alike programs are for children under 18 who are ineligible for Medicaid and CHIP and purchase coverage through the state that provides benefits at least identical to CHIP funded through non-Federal funds including premiums. |

| Medicaid Improvement Fund | Adds $980 million to the fund to reduce state costs associated with claims systems beginning in FY2023. |

For most people, the fifth open enrollment period under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will close at the end of the day on Friday, December 15, 2017. However, depending on where they live and other circumstances, certain individuals will have additional time to sign up for 2018 health coverage. Individuals in certain states are eligible for additional time based on where they live. Other individuals in any state are eligible if their 2017 health plan will be discontinued for 2018.

State-based Marketplaces (SBMs) have flexibility to set their own dates for open enrollment and this year, 10 of the 12 SBMs have done so: California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington.

This year, healthcare.gov will offer a special extension of open enrollment to people who live in, or who moved from, designated areas affected this fall by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria, and Nate. These individuals have until December 31 to sign up for 2018 health coverage through healthcare.gov. However, as of January 17, 2018, CMS has extended the deadline until March 31, 2018 for individuals affected by the 2017 hurricanes in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands; affected residents of Puerto Rico or the Virgin Islands who have since relocated to healthcare.gov states are eligible for this extension.

Areas designated eligible for Individual or Public Assistance Benefits from the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) include the entire states of Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama, and parts of Texas (53 counties), Louisiana (20 parishes), and Mississippi (7 counties). In addition, all of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands have been designated.

In Texas, according to FEMA, the designated areas include the following counties: Aransas, Austin, Bastrop, Bee, Bexar, Brazoria, Burleson, Caldwell, Calhoun, Chambers, Colorado, Comal, Dallas, DeWitt, Fayette, Fort Bend, Galveston, Goliad, Gonzales, Grimes, Guadalupe, Hardin, Harris, Jackson, Jasper, Jefferson, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kleberg, Lavaca, Lee, Liberty, Madison, Matagorda, Milam, Montgomery, Newton, Nueces, Orange, Polk, Refugio, Sabine, San Augustine, San Jacinto, San Patricio, Travis, Tarrant, Tyler, Victoria, Washington, Walker, Waller, and Wharton.

In Louisiana, according to FEMA, the designated areas include the following parishes: Acadia, Allen, Assumption, Beauregard, Calcasieu, Cameron, De Soto, Iberia, Jefferson Davis, Lafayette, Lafourche, Natchitoches, Plaquemines, Rapides, Red River, Sabine, St. Charles, St. Mary, Vermilion, and Vernon.

In Mississippi, according to FEMA, the designated areas include the following counties: George, Greene, Hancock, Harrison, Jackson, Pearl River, and Stone.

To use this hurricane extension, individuals should contact the healthcare.gov call center.

Finally, according to CMS, Maine residents who were unable to enroll in coverage by December 15 due to the impacts of the severe windstorms and resulting power outages across that state should also qualify for more time to enroll. Affected individuals should contact the healthcare.gov call center and provide detailed information about their situation so the Marketplace representative can appropriately assist them.

Finally, no matter where they live, consumers who received discontinuation notices that their 2017 non-group health plan is not being offered in 2018 (for example, because the insurer exited the marketplace or will no longer offer any ACA compliant non-group plans starting in 2018), are eligible for a “coverage loss” special enrollment period (SEP). These individuals have up to 60 days to sign up for new coverage after their 2017 plan ends (January 1-March 1, 2018); people can also apply for the coverage loss SEP in advance of the coverage loss (e.g., before January 1, 2018).

To apply, consumers should log into their marketplace account and indicate they need a SEP due to loss of other minimum essential coverage (MEC).

In federal marketplace states, individuals might need to provide proof of coverage loss before the SEP will be approved. Individuals should have received a discontinuation notice from their insurer stating that their plan will not be offered again in 2018. They should save this notice in case they are asked to verify eligibility for the coverage loss SEP. Consumers in healthcare.gov states can apply for the coverage loss SEP online and select a new plan for 2018. Consumers should act as quickly as possible to avoid/minimize any gap in coverage:

For those who make their plan selection between December 16 and December 31, new 2018 coverage will begin on January 1, 2018

For those who make their plan selection between January 1 and January 15, new 2018 coverage will begin on February 1, 2018

For those who make their plan selection between January 16 and February 15, new 2018 coverage will begin on March 1, 2018

For those who make their plan selection between February 16 and March 1, new 2018 coverage will begin on April 1, 2018

The marketplace may have automatically assigned consumers to a different health plan for 2018 coverage if they did not actively select another plan by December 15. However, the auto-enrollment does not affect consumers’ eligibility for the coverage loss SEP. They can still apply for the SEP to change plans for 2018.

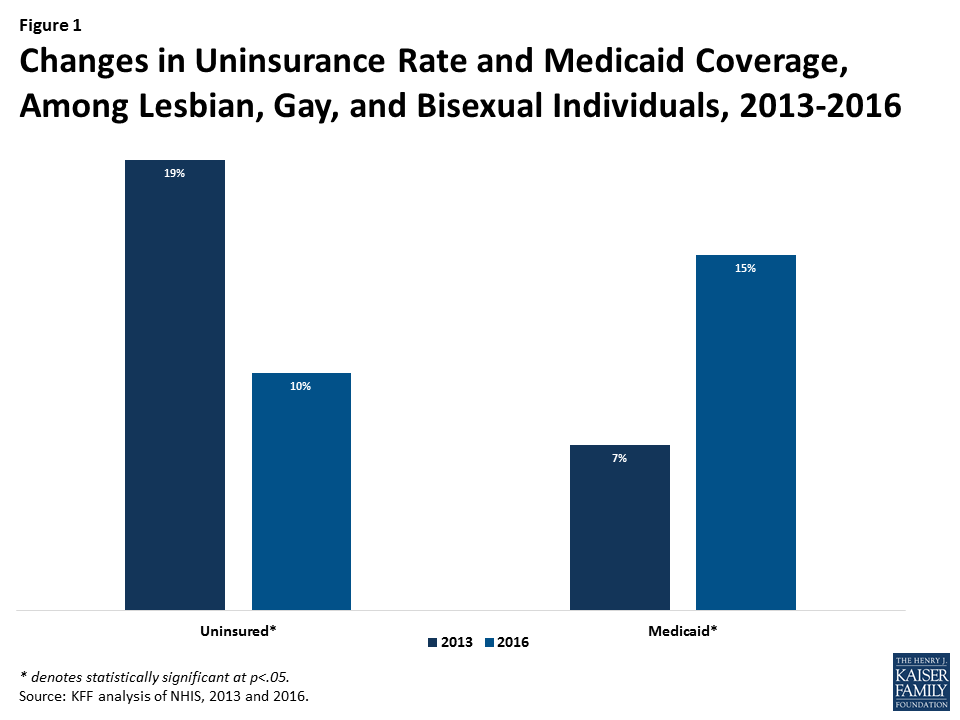

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has provided millions of Americans with new access to insurance coverage, in some cases for the first time. While a significant body of research has explored how the law has affected different populations, limited information has been available on insurance coverage changes by sexual orientation, in part due to the dearth of available nationally representative data about lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals and insurance status.1

This data note provides the most up to date nationally representative estimates of insurance coverage changes among self-identified lesbian, gay and bisexual adults (LGB) under the ACA. It compares survey responses of nonelderly adults using the Sample Adult component from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 2013 and 2016 cycles.2 We find that rates of uninsurance decreased significantly among LGB adults after the implementation of the ACA’s major coverage changes. There was also a significant increase in Medicaid coverage. We were unable to examine changes in private insurance coverage due to sample size limitations.

Historically, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals have faced barriers in accessing healthcare.3 Challenges result from stigma and discrimination, inequality in the workplace, refusal of care, and denial of coverage related to sexual orientation or gender identity. Prior to the ACA, insurance companies could deny LGBT individuals insurance coverage, exclude certain services (e.g. those related to gender transition), or charge higher rates based on sexual orientation or gender identity. Issuers were also able to deny insurance coverage or charge higher rates to people with health conditions that disproportionally affect LGBT individuals such as HIV, mental illness, and substance use disorders.4

Under the ACA, insurers are no longer permitted to consider health status when setting rates or issuing coverage. Further, issuers are prohibited from discriminating on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity in coverage subject to the Essential Health Benefits, including plans sold on the health insurance marketplaces. (The law and implementing regulations also include additional protections that prohibit discrimination based on sex, defined to include gender identity and sex stereotypes, in any health program receiving federal funds, including: Medicaid, Medicare, the marketplaces, and providers who receive federal funds. However, as part of an ongoing lawsuit, a federal court has issued an injunction halting enforcement of this provision’s protections around gender identity.5 )

In addition to non-discrimination protections, the ACA introduced two main coverage pathways. The first is the Medicaid expansion, which provides Medicaid coverage to eligible individuals below 138% of FPL, basing eligibility on income and residency status alone rather than categorical eligibility (e.g. requiring disability or pregnancy in addition to being low-income). As a result of a Supreme Court decision, Medicaid expansion is effectively a state option and to date, 33 states (including DC) have expanded their programs.6 Second, legal US residents are now able to purchase private coverage through insurance Marketplaces with subsidies available to most between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL).

In order to assess changes in coverage among LGB individuals under the ACA, we analyzed data for non-elderly adults from the NHIS, a nationally representative survey conducted by CDC on health and health behaviors. We compared data from 2013, prior to the implementation of major ACA insurance expansions to 2016, after implementation. We were not able to examine coverage among transgender individuals as the NHIS instrument category does not include transgender as a stand-alone category.

Using the 2013 and 2016 NHIS cycles, we estimate that there were 4.8 million U.S. adults between the ages of 18-64 who identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual in 2013, and 5.5 million in 2016. Based on both cycles, we estimate that LGB individuals in this age group make up about 3% of the US population. This is similar to estimates found in other research.7 Uninsurance declined and Medicaid coverage increased significantly for this population after the implementation of the ACA, as follows. (We are unable provide private insurance due to sample size limitations.):

During the early years of ACA implementation, the rate of uninsurance among LGB individuals fell by almost half (from 19% in 2013 to 10% in 2016), representing an estimated 369,000 fewer uninsured LGB individuals in 2016 compared to 2013. The drop in the uninsurance rate experienced by LGB groups was similar to that seen among heterosexuals over this period.8

LGB individuals saw significant gains in Medicaid coverage between 2013 and 2016 (increasing from 7% to 15%), likely due to Medicaid expansion.9 This increase represents an estimated 511,000 more LGB individuals with Medicaid coverage in 2016 compared to 2013. Increases in Medicaid coverage over this period were not significantly different when comparing LGB individuals to heterosexual individuals.10

The ACA has played a significant role in increasing insurance coverage and reducing the rate of uninsurance for people in the United States and many of these gains have translated to the LGB population. Under the ACA, LGB people experienced reductions in the uninsurance rate between 2013 and 2016. Gains in Medicaid coverage have driven this trend, though it is also likely that some uptick in private insurance coverage contributed to declines in the share uninsured as well. As the Administration, Congress, and states, continue to make changes to the health landscape, including to protections for LGBT individuals, it will be important to monitor these trends in future years.

Lindsey Dawson and Jennifer Kates are with the Kaiser Family Foundation. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

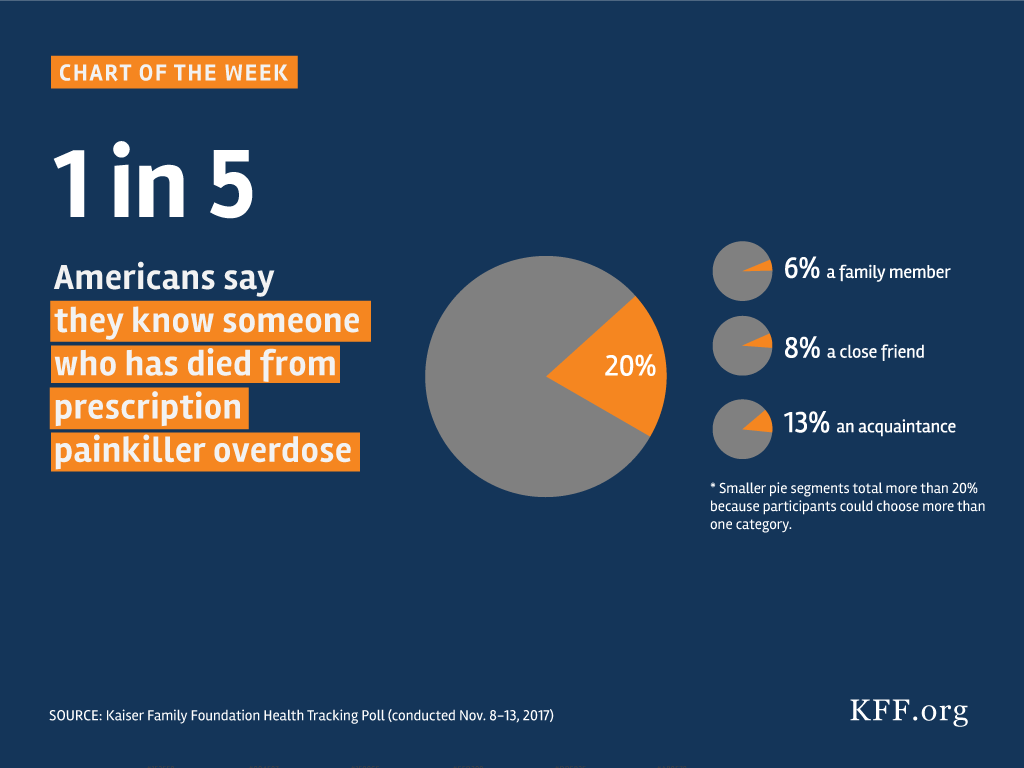

Kaiser Family Foundation Health Tracking Poll (conducted November 8-13, 2017)

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage for about one in five Americans and is the largest payer for long-term care services in the community and nursing homes. Efforts in 2017 to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and cap federal financing for Medicaid were unsuccessful but help to set the stage for 2018. As 2018 begins, there is a focus on administrative actions using Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waivers, state actions on Medicaid expansion, and funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and other federal health care priorities. Medicaid in 2018 is also likely to continue to be part of both federal and state budget deliberations. Pressures to control the federal deficit may reignite efforts to reduce or cap federal Medicaid spending. In addition, Governors will soon release proposed budgets for state FY 2019 that will need to account for uncertainty around CHIP and Medicaid, changes in the economy and the effects of the recent tax legislation as well as funding for rising prescription drugs and initiatives to combat the opioid epidemic. This brief examines these issues.

All indications are that the prospect of significant changes to #Medicaid will remain in state and federal policymakers’ sights – and in the news – during 2018. Here is what to watch in 2018.

Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers provide states an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid not otherwise allowed under current law, provided the demonstrations meet the objectives of the program. As of January 2018, there are 35 states with 43 approved waivers and 21 states with 22 pending waivers. The focus of 1115 waivers has changed over time reflecting changing priorities for states and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). On November 7, 2017, the CMS posted revised criteria for evaluating whether Section 1115 waiver applications further Medicaid program objectives; most notably, the revised criteria no longer cite expanding coverage of low-income individuals as a key criterion. On January 11, 2018, CMS released additional guidance for states pursuing waivers to impose work requirements in Medicaid. This guidance was followed by the approval of the Kentucky waiver on January 12, the first state to receive approval to implement work requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility.

What to Watch:

As of January 2018, 33 states had adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. Finding from over 150 studies about the Medicaid expansion point to increased coverage, increased access to and utilization of care, as well as positive effects on multiple economic outcomes. A number of states had previously considered expansion but efforts were put on hold during the repeal and replace debates in 2017. In November 2017, Maine voters adopted the Medicaid expansion through a ballot initiative.

What to Watch:

On December 21, 2017, Congress provided $2.85 billion in federal CHIP funding as part of its continuing resolution (CR) to keep the federal government operational through January 19, 2018. These CHIP funds are for the period October 1, 2017 through March 31, 2018; however, it is unclear if there is sufficient funding for all states to continue CHIP program through March 31, 2018. Early in 2018, Congress will need to act on the expiring CR and CHIP funding.

On January 5, 2018, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a new score for extending CHIP funding for five years of $800 million over ten years, much lower than its previous estimate of $8.2 billion.1 It noted that the federal costs of extending CHIP decreased because the repeal of the individual mandate in the 2017 tax legislation and other regulatory changes affecting Marketplace premiums made federal costs for Marketplace coverage more expensive. Therefore, extending CHIP, which would increase CHIP coverage and decrease Marketplace coverage reduces the federal budget impact of funding CHIP. Media accounts and statements indicate that CBO also projects that a ten-year extension of CHIP funding would result in net savings to the federal government of $6.0 billion.

The CR also included short-term funding for Community Health Centers for the first and second quarters of FY 2018 at levels below FY 2017. The House passed an $81 billion disaster aid bill for recovery from hurricanes and wildfires in California, Florida, Puerto Rico, Texas and the Virgin Islands, but the Senate did not act. CHC funding and disaster relief are issues that will require additional Congressional action in 2018.

What to Watch:

While Congress, including Speaker Paul Ryan, said that broader entitlement reform proposals are unlikely to emerge in 2018, it is still possible that pressure to reduce the deficit federal could lead to legislative proposals to restrict funding for Medicaid and/or transition the program to a block grant or per capita cap. The 2017 debate over the structure and funding of Medicaid revealed that Medicaid has broad general support and intense support from special populations served by the program. In addition, the proposed changes would have different implications for states given the program variation across states, including whether a state implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as well as other health status, demographic and state fiscal circumstances.

At the state level, debate in 2017 to repeal and replace the ACA created a lot of uncertainty about Medicaid funding and the effects on coverage. Despite the uncertainty, many states continued efforts to expand managed care, move ahead with payment and delivery system reforms, develop initiatives to address the opioid epidemic and expand benefits as well as community-based long-term services and supports. At the end of 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that included a repeal of the penalty for the individual mandate in the ACA and limits on deductions for state and local taxes. These provisions will have a varied effect on state budgets and coverage around the country.

What to Watch:

All indications are that the prospect of significant changes to #Medicaid will remain in state and federal policymakers’ sights – and in the news – during 2018. Here’s what to watch this year.

On January 12, 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved a Section 1115 demonstration waiver in Kentucky, entitled “Kentucky Helping to Engage and Achieve Long Term Health” or KY HEALTH. The overall demonstration includes 2 major components: (1) a program called Kentucky HEALTH that modifies the state’s existing Medicaid expansion and applies new policies to the current Medicaid expansion population, as well as most other adults covered by Medicaid; and (2) a Substance Use Disorder (SUD) program available to all Medicaid enrollees. Kentucky implemented a traditional Medicaid expansion, according to the terms set out in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), in January 2014. Subsequently, Governor Bevin, who ran on a platform to end the Medicaid expansion and dismantle the State-Based Marketplace, was elected in December, 2015. Post-election, the Governor instead decided to seek a Section 1115 waiver to change the state’s traditional Medicaid expansion. On the same day that CMS approved Kentucky’s waiver, Governor Bevin issued an executive order directing the state to terminate the Medicaid expansion if a court decides that one or more of the waiver provisions are illegal and cannot be implemented. This fact sheet summarizes key provisions of Kentucky’s approved waiver. Specific details are included in Table 1.

Kentucky’s Medicaid waiver includes provisions never before approved by CMS, including: a work requirement as a condition of eligibility; premiums of up to 4% of income; multiple coverage “lock-out periods” of up to six months, two of which are new.

Kentucky’s waiver includes a number of provisions never before approved by CMS. For example:

Key provisions in the Kentucky HEALTH portion of the waiver applicable to most adults, including expansion adults and low-income parents, are:

Key provisions in the SUD waiver program available to all Medicaid enrollees include:

Years of research and experience implementing Medicaid and CHIP point to coverage gains realized by simplified and streamlined processes and reductions in enrollment and retention of people who remain eligible for coverage when processes are complicated or require additional documentation or verification. Kentucky’s waiver proposal anticipated that the demonstration would result in about 95,000 fewer Medicaid enrollees after implementation, as a result of beneficiary non-compliance with waiver policies, such as premiums and the work requirement, and, in later years, due to shifts to commercial coverage.

Separate from the provisions that apply to people who are determined “medically frail,” Kentucky’s waiver also requires the state to comply with the rights of people with disabilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and Section 1557 of the ACA. For example, the state must exempt people with disabilities from losing coverage if they cannot comply due to a disability-related reason and must offer reasonable modifications to program policies to enable them to comply.

Research points to gains in coverage and reductions in the uninsured, increases in access and health care utilization, and positive fiscal impacts as a result of the Medicaid expansion in Kentucky and other expansion states. Since implementing the ACA, Kentucky’s nonelderly adult uninsured rate fell from 16.3% in 2013, to 7.2% in 2016, one of the largest reductions in the country, and nearly 462,000 adults are enrolled in Medicaid expansion coverage as of FY 2016.

The Kentucky waiver does not include any specific evaluation hypotheses or metrics related to the Kentucky HEALTH provisions, including those like the work requirement that have never before been approved and are likely to have significant implications for beneficiaries’ ability to retain coverage for which they are eligible. While the waiver includes a multitude of exemptions for certain individuals and good cause exceptions (the details of which differ among specific waiver policies), as well as “state assurances” about implementation, these provisions are complex and will require administrative staff time and resources and sophisticated systems to implement. Despite the substantial consequences for beneficiaries and the administrative complexities of operationalizing new policies, submission and CMS approval of detailed operational protocols are not required and amendments or changes to the waiver terms may not be subject to full public notice and comment. Implementation of the Kentucky HEALTH provisions will begin in April, 2018, with full implementation by July, 2018. The implementation processes, whether there are adequate resources available, and the waiver’s impact on eligible people and state administrative procedures and costs will be important areas to watch.

| Table 1: Kentucky’s Section 1115 Medicaid Expansion Demonstration Waiver | |

Element | Kentucky Waiver |

| Overview: | The overall demonstration, called KY HEALTH, includes 2 major components:

|

| Duration: | 1/12/18 through 9/30/23. Partial implementation of Kentucky HEALTH begins 4/1/18 (for accrual of incentive account dollars, described below), with full implementation by 7/1/18. |

| Coverage Groups: | Kentucky HEALTH includes the adult expansion group, low-income parent/caretakers, those receiving Transitional Medical Assistance (TMA), pregnant women, and former foster care youth. Exemptions from specific policies are noted below. |

| Medical Frailty Determination: | People who are determined to be medically frail are exempt from several waiver provisions (noted below). The state will apply the federal definition of medical frailty, including people with disabling mental disorders; chronic SUD; serious and complex medical conditions; physical, intellectual, or developmental disabilities that significantly impact the ability to perform one or more activities of daily living; and those who meet Social Security disability criteria. The waiver also refers to the process in the state’s alternative benefit plan (ABP). The ABP for low-income parents and other traditional populations currently specifies that individuals can self-identify as medically frail. However, no further detail about this process is provided in the waiver terms and conditions, which also provide that any operational protocol would be optional for the state to submit to CMS for approval and incorporation into the waiver (as described below). (The ABP for expansion adults is silent about medical frailty.) |

| Coverage Renewals and Lock-Out: | Most adults (expansion, low-income parents and TMA) who fail to timely complete the annual eligibility renewal process (by not providing any required documentation after a 90-day grace period) will be disenrolled and locked out of coverage for up to six months, unless they verify good cause or cure the lock out as described below. Pregnant women, former foster care youth, and beneficiaries determined medically frail are exempt from this lock-out. In addition, people with disabilities cannot be disenrolled for failure to submit renewal paperwork if they needed but were not provided with reasonable modifications, under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and Section 1557 of the ACA, necessary to complete the process. The state shall use pre-populated forms and timely process applications to avoid further coverage delays once the lock-out period ends. The state also shall achieve successful ex parte renewal for at least 75% of Kentucky HEALTH adults, excluding those whose eligibility is suspended at renewal. |

| Lock-out for Failure to Timely Report Changes Affecting Eligibility: | Most adults (expansion adults, low-income parents, and TMA) who fail to report a change in circumstances that would have resulted in ineligibility within 10 days will be disenrolled and locked out of coverage for up to six months. Disenrolled individuals can cure the lock-out and re-enroll prior to six months (as described below) and receive pre-disenrollment safeguards (as described below). Pregnant women, former foster care youth, and beneficiaries determined medically frail are exempt from this lock-out. |

| Premiums: | Most adults (expansion adults, low-income parents, TMA, and those receiving Medicaid premium assistance for ESI) must pay monthly premiums. People who are medically frail, pregnant women, and former foster care youth are exempt from premiums, although former foster care youth and people who are medically frail can choose to pay premiums to access an incentive account (described below). Premiums shall not exceed 4% of household income, except that all non-exempt beneficiaries must pay a minimum of $1.00/month. The state may vary premium amounts on factors including, but not limited to, household income or length of time enrolled in Kentucky HEALTH, subject to the 4% household limit. Other bases for varying premiums should be consistent with how premiums vary in the state’s commercial insurance market. Beneficiaries who meet the 5% aggregate household cap on premiums and cost sharing will pay $1.00 monthly premiums for the remainder of the calendar quarter. The state will determine premium amounts based on income at the eligibility determination and notify the beneficiary and health plan. The state must redetermine monthly premium amounts annually at renewal and any time the state is made aware of a change in household income, with new amounts effective on the 1st of the next month. The state may reduce a premium amount at any time. The state will annually evaluate the premium rates and amounts, and reserves the right to increase premium amounts up to the 4% of income limit in response to evaluation results. The state will notify CMS of upcoming premium changes through the demonstration annual report (described below) and will notify beneficiaries at least 60 days prior to implementing a premium change. Third parties (except health plans), such as non-profit organizations and providers, may pay premiums on a beneficiary’s behalf. Provider or related entities must have criteria for making premium payments that are not based on whether beneficiaries will receive services from the provider. Health plans will send monthly invoices and collect premiums. Health plans can attempt to collect unpaid amounts, but may not report to credit agencies, place a lien on the enrollee’s home, refer to debt collectors, file a lawsuit, or seek a court order to garnish wages. The state will not sell any unpaid obligations for collection by a third party. Unpaid amounts are collectible by the state, but re-enrollment is not conditioned on repayment except when curing a lockout (described below). Enrollees shall have an opportunity to review and seek correction of payment history. Enrollees will not be charged a higher premium due to nonpayment or underpayment in a prior month, although past due amounts will be separately reflected on subsequent invoices. Overpayments resulting from a change in circumstances will reduce the next month’s premium. The state shall have a process to refund any premiums paid for a month during which the person was ineligible for Medicaid. The state must suspend monthly invoices to enrollees whose eligibility is suspended for failure to meet the work requirement (described below) and send written notice to prevent overpayments. |

| Limitation on Changing Health Plans: | Beneficiaries may only change health plans for cause once the initial premium is paid or the 60-day payment period expires, until the beneficiary’s next annual enrollment period (waives 90-day change period after initial plan enrollment; applies to all groups except pregnant women and former foster care youth). Individuals can select a health plan when applying or the state will auto-assign them to a plan. |

| Effective Coverage Date: | Waives 3-month retroactive coverage for most adults (expansion adults, low-income parents, and TMA), including people who are medically frail. Pregnant women and former foster care youth remain eligible for retroactive coverage. Requires most adults (expansion adults, low-income parents and TMA) to pay their first month’s premium prior to the start of coverage unless they have been determined medically frail or presumptively eligible. Coverage begins on the first day of the month in which payment is received. Individuals below 100% FPL who are not medically frail, pregnant or former foster care youth and do not pay a premium within 60 days of the invoice have coverage effective on the first of the month in which the 60 day payment period expires. They also must make point of service copayments and do not have access to the My Rewards incentive account (described below). Those above 100% FPL who are not medically frail, pregnant or former foster care youth cannot enroll in coverage without a premium payment and must re-apply if the initial payment is not made within 60 days of the invoice. People exempt from premiums (those known to be medically frail at the time of application, pregnant women, former foster care youth) have coverage effective on the first of the month of application once determined eligible. Individuals (other than those determined presumptively eligible) can choose to make an initial premium prepayment (at an amount determined by the state, up to the maximum premium amount for those at 138% FPL) as part of the electronic application to expedite coverage. Once the individual is determined eligible for Medicaid, coverage will begin on the first of the month in which the initial premium pre-payment was made. However, once a premium pre-payment is made, the beneficiary may not change health plans except for cause prior to their next annual open enrollment period (waives 90-day period to change health plans after initial enrollment as described above). Premium prepayments can be refunded for those determined ineligible or for whom premium payments are not required, at the individual’s request. Overpayments of the initial premium are credited to amounts due for the remainder of the benefit period, with any remaining amount refunded to the beneficiary. Anyone determined presumptively eligible continues coverage without a break as of the first of the month after the full Medicaid eligibility determination without having to first pay a premium. Instead, these enrollees have copays at state plan amounts and then have 60 days from their first premium invoice to make a payment. (Those over 100% FPL who are not medically frail, pregnant or former foster care youth and do not pay a premium within 60 days will be disenrolled and locked out for up to 6 months as described below.) |

| Consequences for Non-Payment of Premiums, including Disenrollment and Lock-Out or Copays: | As described above, premiums are a condition of eligibility for expansion adults, parents, TMA, and those receiving ESI premium assistance from 101-138% FPL unless medically frail. These groups will be disenrolled from coverage for non-payment of a premium after 60-days from the monthly invoice and not allowed to re-enroll for six months unless they cure the lockout (described below) or verify good cause (described below). People who are disenrolled for non-payment also will have dollars deducted from their incentive account (described below). They also are subject to safeguards prior to disenrollment (described below). People re-enrolling after a lock-out will not be required to pay past due premiums as a condition of eligibility. People subject to premiums at or below 100% FPL (unless medically frail or former foster care youth) will not be disenrolled for nonpayment but will be charged copays at state plan amounts, have dollars deducted from their incentive account (described below), and have their incentive account suspended (unable to accrue or use funds) up to 6 months. These individuals can return to paying premiums instead of copays and reactivate their incentive account before 6 months if they comply with the same requirements as are required to cure a lockout (see below); payment of past-due premiums is not required to reactivate incentive accounts. Those determined to have good cause for non-payment will be eligible to resume premium payments instead of copays and access their incentive account in the first administratively feasible month. |

| Deductible Account: | Most adults (expansion adults, low-income parents, TMA, and former foster care youth) will have an account to which the state will contribute a $1,000 annual deductible to cover non-preventive healthcare services. Beneficiaries will receive monthly statements with the cost of utilized services and their account balance. If the deductible is exhausted before the end of the benefit year, enrollees will have access to covered services without unreasonable delay. If funds remain in the deductible account at the end of the year, enrollees can transfer up to 50% of the prorated balance (for months in which the person was enrolled and eligibility was not suspended) to their My Rewards incentive account (described below). Pregnant women and people receiving Medicaid as premium assistance for ESI will not have a deductible account. |

| Incentive (My Rewards) Account: | All adults (expansion adults, low-income parents, TMA, former foster care youth, and those receiving ESI premium assistance) will have a My Rewards incentive account if they are paying monthly premiums of at least $1.00. Pregnant women can have a My Rewards account without having to pay premiums. The incentive account may be used to access additional, prior authorized, benefits not otherwise covered once sufficient funds are accrued. These benefits include dental, vision, over the counter (OTC) medications, and limited reimbursement for the purchase of a gym membership for non-medically frail expansion adults, and only gym membership for all other adults (who instead continue to receive dental, vision and OTC medication in the state plan benefit package as described below). Vision, dental, and OTC medications are charged to the incentive account at the Medicaid fee-for-service rate and to the extent these services would have been covered under the state plan. For services that do not have a state plan rate, CMS must determine that the rate is cost effective and efficient. Expenditures for items and services covered under the incentive account must be determined by the Secretary to meet the federal definition of medical assistance. Enrollees can start accumulating dollars in their incentive account in April, 2018, (prior to full Kentucky HEALTH implementation in July, 2018). Account funds are not subject to an annual limit and can have a negative balance of up to $150, although beneficiaries will not have to make a monetary payment to the state for a negative account balance. Funds accrue, or are subject to deductions, as long as Medicaid eligibility is not suspended or disenrolled. Enrollees can earn incentive account funds by:

Enrollees will have incentive account funds deducted for:

|

| Work Requirement and Lock-Out: | Requires monthly documentation of 80 hours of work activities per month as a condition of eligibility for most adults ages 19-64. Beneficiaries cannot apply excess hours to future months. Beneficiaries who have not been subject to the work requirement in the past five years will have a three month period before being required to comply. The work requirement will be implemented on a regional basis. Documentation is pursuant to the state’s verification plan which currently does not directly address verification for the work requirement and prohibits self-attestation for verification of income. The only people exempt from “active” monthly documentation of meeting the work requirement are those who are meeting or exempt from TANF or SNAP work requirements, those enrolled in ESI premium assistance, and those who work at least 120 hours/month. Former foster care youth, pregnant women, one primary caregiver of a dependent minor child or adult who is disabled per household, people who are medically frail, those with an acute medical condition validated by a medical professional that would prevent them from complying, and full-time students are exempt from the work requirement. People with disabilities under the ADA/504/1557 also are exempt from the work requirement if unable to participate due to disability-related reasons (more detail below). Qualifying work activities include but are not limited to any combination of employment, job search, job training, education (related to employment, high school, college, graduate, ESL, vocational, etc.), volunteer work (community work experience, community service), caring for a non-dependent relative or other person with a disabling chronic condition, or participation in substance use disorder treatment. The state must make good faith efforts to connect enrollees to existing community supports that are available to assist in meeting the work requirement, including available non-Medicaid assistance with transportation, child care, language access services and other supports, and make good faith efforts to connect people with disabilities with services and supports necessary to enable them to comply. According to CMS guidance, Medicaid funds cannot be spent on employment support services. Those who fail to meet the required work hours for a month will have one month to cure their noncompliance (as described below). They also can request (at least 10 days before suspension) and verify good cause (as described below) or appeal the suspension before it takes effect. Otherwise, eligibility is suspended on the 1st of the month following the one month opportunity to cure, and the suspension lasts until the first of the month after the person cures the suspension (described below). Those with suspended eligibility at the time of annual renewal will be disenrolled unless they can show they meet the work requirement or are exempt in the renewal month. The state must assess areas that experience high rates of unemployment, areas with limited economies and/or educational opportunities, and areas that lack public transportation to determine whether there should be further exemptions from the work requirement and/or additional mitigation strategies, so that the work requirement will not be impossible or unreasonably burdensome for beneficiaries to meet. The state shall provide timely written notice about when the work requirement begins, whether an enrollee is exempt and under what conditions the exemption would end, the specific work activities to satisfy and to cure noncompliance, information about resources that help connect beneficiaries to opportunities for activities that would meet the work requirement, community supports available to assist beneficiaries in meeting the requirement, how hours will be counted and documented, what gives rise to a suspension and how it could affect renewal, how to apply for good cause, how to appeal a suspension or good cause denial, and the explanation for good cause decisions. |

| Notice and Appeal Rights Required for All Lock-Outs/Eligibility Suspension: | The state shall provide advance notice and appeal rights prior to any disenrollment/eligibility suspension and lock-out, including the right to apply for Medicaid on a basis other than an expansion adult or low-income parent, the impact on the ability to access Marketplace coverage and premium tax credits, what to do if circumstances change creating eligibility for Medicaid on another basis, and implications for minimum essential coverage. During appeal hearings, individuals must have the opportunity to raise additional issues, including whether they should be subject to the lock-out, and to provide additional documentation during the appeals process. The state also shall provide written notice of the specific activities that qualify individuals for early re-enrollment during a lock-out period; the groups that are exempt from lock-outs; and the good cause exceptions to lock-outs (listed below). |

| Outreach and Education: | The state shall provide beneficiary education and outreach that supports compliance with renewals, such as through communications or coordination with state-sanctioned assisters, providers, health plans or other stakeholders. The state also must conduct outreach and education to inform beneficiaries about how premiums should be paid, the potential impact of a change in income; the fact that premiums are determined based on monthly income; the deadline to report a change in circumstances affecting eligibility and the consequences for failing to do so; and how to re-enroll if disenrolled for non-payment. Health plan invoices also must contain this information. |

| Good Cause Exemptions to Lock Outs/Eligibility Suspension: | Enrollees have good cause and can re-enroll in coverage after an eligibility suspension due to failure to meet the work requirement or without waiting six months or completing the activities otherwise required to cure a lock-out (described below) for failure to timely renew eligibility, failure to timely report a change in circumstances leading to ineligibility, or failing to pay premiums if they can verify that they:

This is a list of minimum good cause criteria. |

| Curing a Lock-Out/Eligibility Suspension to Re-enroll in Coverage: | Individuals who have been disenrolled and locked out of coverage for failing to pay premiums, renew eligibility, or report changes (and those under 100% FPL who lose access to their incentive accounts for failing to pay premiums) can cure the lock-out without waiting six months if they both (1) pay the premium for the 1st month of coverage to restart benefits; (2) if locked out (or lost access to incentive account) due to premium nonpayment, also make a one-time payment equaling premiums owed for each month in which they received healthcare coverage in the 60 days prior to the lockout; and (3) attend a state-certified health literacy or financial literacy educational course. However, the opportunity to cure a lockout (or reactivate incentive account) is limited to once per year per consequence type. Individuals who fail to meet the work requirement can avoid eligibility suspension by, in the month immediately following the month of noncompliance, (1) meeting the work requirement for the current month; and either (2) making up missing hours from the prior month, or (3) completing a state-approved health or financial literacy course (this option is available once/year). Individuals who go on to have eligibility suspended for failing to meet the work requirement can then cure the suspension by completing 80 hours of work activities in a 30-day period or a state-approved health or financial literacy course, The state shall ensure that the specific activities that qualify individuals to cure a lockout or eligibility suspension are available during a range of times and through a variety of means (e.g., online, in person) and at no cost to the individual. |

| Safeguards for Lockouts/Eligibility Suspensions: | Before disenrollment and lock-out for failing to report a change in circumstances or to pay premiums, and before eligibility suspension for failing to comply with the work requirement, the state must determine the beneficiary ineligible for all other Medicaid pathways and review eligibility for other insurance affordability programs. In addition, the state must offer an opportunity to provide additional clarifying information that an enrollee did report a change or had good cause before disenrollment and lockout for failure to report a change in circumstances affecting eligibility. Prior to disenrollment and lockout for nonpayment of premiums, the state also must notify the individual that they are able to request a medical frailty review, and the health plan must send at least 2 notices about the delinquent payment, the due date to avoid disenrollment, and the option for a medical frailty screening. Those who become pregnant or medically frail or eligible for Medicaid under another coverage pathway during the lockout period for nonpayment of premiums can re-enroll on that basis. While eligibility is suspended for failure to comply with the work requirement, those who become pregnant, meet an exemption from the work requirement (listed above), or become eligible for Medicaid through another pathway can re-enroll. |

| Benefits: | Expansion adults receive an alternative benefit package (ABP) as defined in a state plan amendment. Pregnant women, former foster care youth, people who are medically frail, low-income parents, and those receiving TMA receive the traditional state plan benefit package, which continues to include vision, dental, and over-the-counter (OTC) medications. These services are excluded from the expansion adult ABP and instead available through the My Rewards account (described above). No waiver of EPSDT for those under 21. Waives non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) for most expansion adults. Those who are medically frail, 19 or 20 year olds entitled to EPSDT, former foster care youth, and pregnant women continue to receive NEMT for all services (see medical frailty exception for methadone NEMT below). Adds methadone to the state plan benefit package upon demonstration approval, but contingent on waiving NEMT for methadone services provided to all enrollees except children under 21, former foster care youth, and pregnant women (no medically frail exception). Upon CMS approval of an implementation protocol, the benefit package for all enrollees (both those in Kentucky HEALTH and others), will include SUD residential treatment, crisis stabilization, and withdrawal management services provided in IMDs (short term stays, no day limit specified). |

| Delivery System: | Continues to use existing capitated Medicaid managed care health plans for all populations statewide (except those in ESI premium assistance). |

| Reasonable Accommodations and Modifications for People with Disabilities: | The state must provide reasonable accommodations under the ADA/504/1557 to afford people with disabilities an equal opportunity to participate in the work requirement. The state also must provide reasonable modifications to the eligibility renewal process, the obligation to report a change in circumstances, and premium payment and work requirement protections and procedures to enable and assist people with disabilities under the ADA/504/1557. Reasonable modifications for the work program include but are not limited to assistance with demonstrating eligibility for good cause, appealing suspensions, documenting work activities and other documentation requirements, and understanding work requirement notices and program rules, and must include exemptions when non-compliance is due to a disability-related reason, modifications in the number of hours required, and provision of support services necessary for participation. The state must evaluate individuals’ ability to participate in the work requirement and the types of reasonable modifications and supports needed. The state also must assess whether people with disabilities have limited job or other opportunities for reasons related to a disability and address those barriers. The state also must maintain a system that identifies, validates, and provides reasonable modifications for people with disabilities related to the obligations to report a change in circumstances, to pay premiums, and to comply with the work requirement. |

| Implementation Processes and Protocols: | The waiver only requires the state to submit operational protocols for the SUD provisions for CMS approval and incorporation into the waiver terms and conditions. A SUD implementation protocol is due within 120 days of demonstration approval. It should address the plan for meeting the following milestones:

Protocols governing operation of Kentucky HEALTH, including the work requirement, premiums, healthy behaviors, and other provisions only will be submitted at state option. |

| Performance Metrics and Monitoring: | The state must submit proposed metrics for quarterly and annual monitoring reports within 120 days of implementation, which will be jointly identified with CMS. Metrics may include but are not limited to beneficiary engagement through the incentive account, work requirement initiatives, and coverage of SUD services. The state also must submit an SUD monitoring protocol within 150 days of demonstration approval, including reporting on each of the milestone areas in the implementation protocol and for each county, access to MAT, availability of MAT providers, the number of individuals accessing MAT including methadone, and the estimated cost of provided NEMT for accessing methadone. The SUD monitoring protocol also must include data collection, reporting and analytic methodologies for performance measures identified by the state and CMS, including timeframes and a baseline, target and annual goal for closing the gap. |

| Reports to CMS, Budget Neutrality, and Administrative Costs: | The state will submit to CMS 3 quarterly reports and 1 annual report each year and post them on the state website within 30 days of CMS approval. The reports must document:

The state shall separately track and report administrative cost directly attributable to the demonstration (not included in budget neutrality). |

| Evaluation: | The state must begin to arrange for an independent party to conduct an evaluation upon demonstration approval. The state will submit a draft evaluation design to CMS for approval within 180 days of demonstration approval, a revised draft within 60 days of receiving CMS’s comments, and will publish the evaluation design within 30 days of CMS approval. Each hypothesis must specify quantitative and qualitative research methodologies, proposed baseline and comparison groups, proposed process and outcome measures, data sources and collection frequency, cost estimates, and timelines. The design will incorporate multiple stakeholder perspectives including but not limited to surveys of beneficiaries enrolled and no longer enrolled and national survey data. The interim evaluation is due (and should be posted for public comment with) when submitting an application for the waiver renewal or else 1 year prior to demonstration end. The final interim evaluation shall be posted to the state’s website 60 days after receiving CMS comments on the draft. The draft summative evaluation is due to CMS within 18 months of the end of the initial waiver approval period, and the final summative evaluation is due within 60 days of CMS’s comments and must be posted to the state’s website within 30 days of CMS approval. Should CMS undertake a federal evaluation of the demonstration or any component, the state will cooperate fully and timely. The state also must conduct an independent mid-point assessment of the SUD provisions within 90 days after the third year of the demonstration and collaborate with health plans, providers, beneficiaries, and other key partners to examine progress toward milestones. The SUD implementation protocol must be modified for milestones at medium to high risk of not being achieved. The draft SUD evaluation design is due to CMS within 180 days of demonstration approval. Hypotheses should include initiation and compliance with treatment, utilization of ED and inpatient hospital services, reduction in key outcomes such as overdose deaths, effectiveness of MAT, interaction of MAT impact and access to NEMT and cost effectiveness of the IMD payment and NEMT waivers. Evaluation of the NEMT waiver shall include a beneficiary survey approved by CMS. |

| Process for Waiver Amendments: | Allows waiver terms and conditions to be revised to reflect changes that the Secretary determines are “of an operational nature” without requiring submission of a waiver amendment, public notice and comment, budget neutrality calculations, a detailed description of the amendment including the impact on beneficiaries, supporting documentation, data supporting evaluation hypotheses, and how the evaluation design will be modified if applicable. Waiver amendments are subject to guidance published in a 1994 Federal Register public notice, instead of the ACA public notice and comment process. The 1994 public notice requires the state to do one of the following: (1) hold at least one public hearing with time for comment on the “most recent working proposal”; (2) use a commission or similar process with an open public meeting in proposal development; (3) submit results from enactment of a proposal by the state legislature that includes an “outline” of the proposal; (4) provide for formal notice and comment of at least 30 days under the state administrative procedures act; (5) post a notice of intent to submit a proposal in newspapers of general circulation and provide a mechanism for receiving a copy of the proposal and at least 30 days to comment; or (6) any other similar process for public input that would allow an interested party to learn about and comment on the proposal contents. |

| Public Input: | Public forum required within six months of implementation and annually thereafter. |

| SOURCE: CMS Special Terms and Conditions, KY HEALTH 1115 Demonstration, #11-W-00306/4 and 21-W-00067/4, approval period Jan. 12, 2018 through Sept. 30, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ky/ky-health-ca.pdf. | |

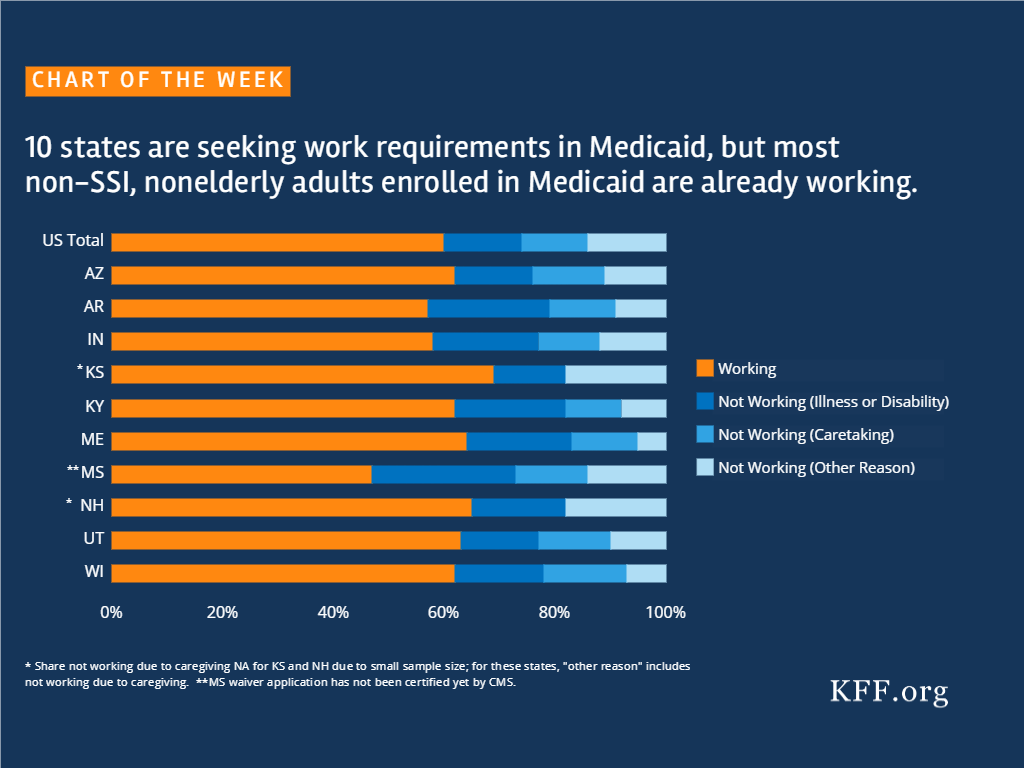

With the approval of Kentucky’s Medicaid expansion waiver, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has for the first time granted a state permission to make Medicaid eligibility conditional on meeting a work requirement. Nine other states have waivers pending at CMS that would impose work requirements, including Arizona, Arkansas, Kansas, Indiana, Wisconsin, Maine, New Hampshire, Mississippi and Utah.

A new brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation highlights what the work requirements would be in each state, including what would count as work activities (e.g. job search and training, community service), the hours required, and what the common exemptions to the requirements would be (e.g. disability, being in drug treatment, caregiving). The brief also highlights some of the key issues to consider in implementing such requirements, such as administrative costs, potential confusion over documentation requirements and the risk that some people will lose coverage for which they remain eligible.

Also available is our updated Medicaid waiver tracker, which rounds up states’ approved and pending Medicaid waiver requests.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of March 2017 Current Population Survey.

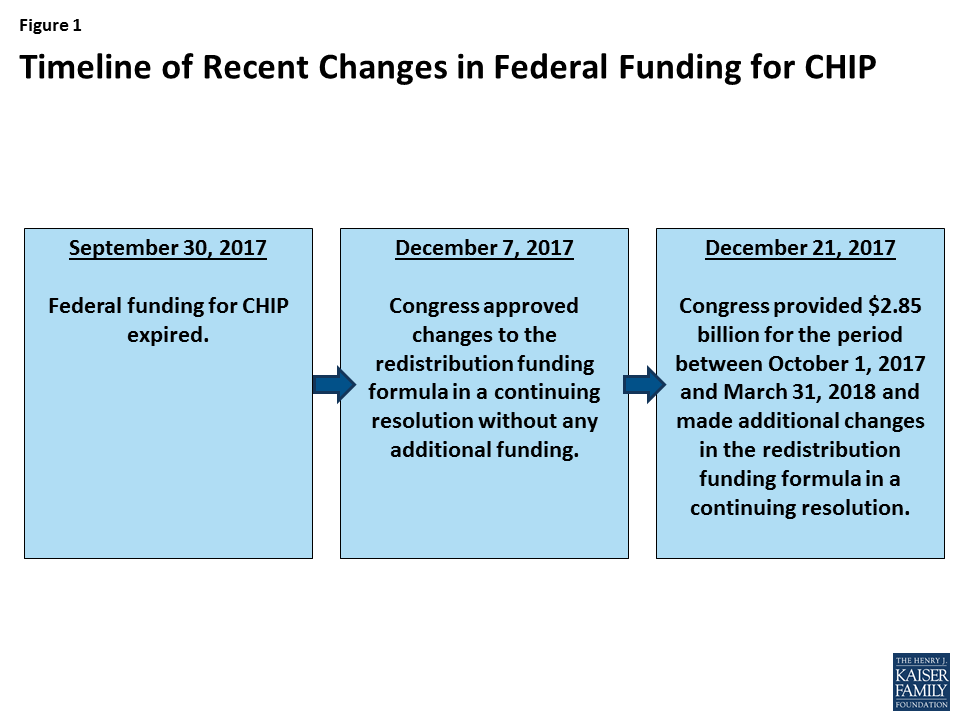

This fact sheet provides an overview of the current status of federal funding for CHIP and implications for states and families. CHIP covers 8.9 million children in working families who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but cannot afford or access private coverage. (See here for state Medicaid and CHIP eligibility limits for children.) Federal funding for CHIP expired on September 30, 2017. On December 21, 2017, Congress provided a short-term extension of federal funding for the program as part of its continuing resolution to keep the federal government operational through January 19, 2018. However, without longer-term federal funding, states continue to face uncertainty and may need to reduce coverage, while families may experience confusion about the status of coverage and face concerns and worries about losing their children’s coverage.

Federal CHIP funds available to states are limited. Federal funds currently available to states include:

All of these sources are limited and insufficient to support coverage through 2018. Once states exhaust these funds, no additional funds will be available unless Congress enacts legislation with an appropriation.

Prior to providing short-term funding in the December 21 continuing resolution, Congress made changes in a December 7 continuing resolution that allowed CMS to direct more redistribution funds to states facing budget shortfalls in early 2018 (Figure 1). No additional funds were provided with this change. As such, it resulted in more redistribution funds going to states experiencing budget shortfalls during the first quarter of 2018, leaving less funding for remaining states. The December 21 continuing resolution further changed how redistribution funds go to states so that they are provided on a monthly basis in the order in which states realize monthly funding shortfalls.

The short-term funding provided temporary relief to states but will still leave them facing budget shortfalls. Prior to the short-term funding, 37 states anticipated they would exhaust federal funds by the end of March 2018, including 16 that projected exhausting funds by the end of January 2018. The continuing resolution provided $2.85 billion in funding for the period October 1, 2017 through March 31, 2018. CMS released preliminary information on the allotments to states from this funding. However, it is unclear how long this funding will hold states over. In a recent statement, CMS indicated that it is “unable to say with certainty whether there is enough funding for every state to continue its CHIP program through March 31, 2018.”1 Without additional federal funds, the majority of states will face a budget shortfall because nearly all states assumed full continued federal CHIP funding in their state fiscal year (SFY) 2018 state budgets.2

The short-term funding delayed some planned state actions to reduce CHIP coverage, but some states have indicated that the funding may only extend coverage for a few additional weeks. Prior to short-term funding, many states with separate CHIP programs were planning to terminate coverage and/or close enrollment for children and/or to terminate coverage for pregnant women. A number of states were preparing to take action in January 2018, and had started warning families about potential coverage reductions in December. After Congress provided the short-term funding, these states delayed planned actions for January. However, in some cases, they note that they may only be able to extend coverage for a few additional weeks (Figure 2):

States with CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion coverage must determine how they will fund the increased cost of covering these children at the lower federal Medicaid match rate. States are required to maintain CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion coverage under the Affordable Care Act maintenance of effort requirement. Once federal CHIP funds are exhausted, states will face increased costs since they will receive the lower federal Medicaid match rate for this coverage. States can address these shortfalls by reducing costs in Medicaid, making reductions in other areas of the budget, or increasing revenues. States will face challenges replacing federal dollars since many were already facing shortfalls heading into SFY 2018.7

Without stable long-term funding, states face ongoing uncertainty that contributes to challenges managing their programs as well as wasted administrative time and costs. Without secure funding, states must continue to plan for how they will address the shortfalls they will face once federal funds are exhausted. States have to take an array of actions to implement program changes and need to build in time to conduct these actions as they plan to make program changes. In addition, states face administrative costs associated with these actions. If planned actions change as the funding situation changes, they face additional time and costs associated with changing course or reversing changes.

Families also face uncertainty and confusion around the status of their CHIP coverage. As delay over long-term funding for CHIP continues, a growing number of families are learning about potential reductions in CHIP coverage through media reports and notices or information provided by states. With state program plans rapidly changing, families may be uncertain and confused about the status of their coverage. This confusion could result in some potential coverage losses, for example, if a family does not renew coverage because they believe it is no longer available. Moreover, families face increasing concerns and worries about how they will meet the health care needs of their children if their state eliminates their CHIP coverage.

Reductions in CHIP coverage will result in coverage losses for children and negative effects on children’s health and family finances. If states close enrollment and/or discontinue coverage for children in separate CHIP programs, some children could shift to their parents’ employer-sponsored plans or Marketplace plans, but they would likely face increased costs for coverage and have higher cost sharing and less comprehensive benefits than they have under CHIP. Other families would not be able to afford private coverage and their children would become uninsured. Previously, some states closed enrollment in CHIP for limited periods in response to state budget pressures, and studies show that this led to coverage losses, left eligible individuals without access to coverage, and had negative effects on health and family finances.

Congress still must complete multiple steps to extend funding, although changes in the tax law significantly reduced the size of federal offsets Congress has to make in federal spending to extend CHIP. The House has passed a bill that would extend federal CHIP funding for five years, providing states the funding necessary to support coverage, which was over $14 billion in 2016. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) previously estimated that this extension would result in a net cost to the federal government of $8.2 billion, which the bill offset through several provisions. The Senate Finance Committee has also reported a bill out of committee to extend funding for five years. However, the full Senate has not yet taken up action on this bill, and the bill did not include offsets. Final legislation still requires passage by the full Senate, resolution of any differences between the House and Senate bills, and signature by the President. One factor contributing to delay of continued progress to pass the five-year extension has been difficulty reaching agreement on how to offset the federal costs to extend coverage. On January 5, 2018, the CBO released a new score for the CHIP funding extension of $800 million, much lower than its previous estimate of $8.2 billion.8 It noted that the costs to the federal government of extending CHIP decreased because the repeal of the individual mandate in the recent tax legislation and other regulatory changes affecting Marketplace premiums made Marketplace coverage more expensive for families and increased subsidy costs for the federal government. Therefore, extending CHIP, which would increase CHIP coverage and decrease Marketplace coverage, requires fewer federal offsets compared to before the changes. Media accounts and statements further indicate that CBO also projects that a ten-year extension of CHIP would result in net savings to the federal government of $6.0 billion.9