Strategies for Improving Health Coverage and Reducing Costs: Major Proposals and Key Considerations

Tricia Neuman, a KFF Senior Vice President and Director of KFF’s Program on Medicare Policy, testified on June 12, 2019, before the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means as part of a hearing on Pathways to Universal Health Coverage. Her testimony describes a range of proposals to broaden health insurance coverage and make health care more affordable, the similarities and differences among them, and the policy choices and trade-offs that could have significant implications for coverage and costs.

Visualizing Health Policy: Barriers to Care Experienced by Women in the United States

VIEW JAMA INFOGRAPHIC

Visualizing Health Policy: Barriers to Care Experienced by Women in the United States

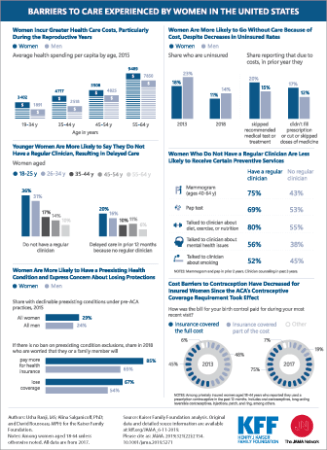

This Visualizing Health Policy infographic looks at barriers to care experienced by women in the United States. Women incur greater health care costs than men, particularly during the reproductive years. Despite a lower uninsured rate than men (11% vs 14%), women are more likely to skip a recommended medical test or treatment due to cost. However, cost barriers to contraception have decreased for insured women since the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) coverage requirement took effect. Three of 4 women reported that insurance covered the full cost of birth control during their most recent visit. Younger women are less likely to report having a regular clinician. Women without a regular clinician are less likely to receive certain preventive services, such as a mammogram and Papanicolaou test. Women are more likely than men to have a preexisting health condition (29% vs 24%) and express concern about the consequences of lifting ACA protections that ban preexisting condition exclusions.

Visualizing Health Policy is an infographic series produced in partnership with the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The full-size infographic is freely available on JAMA’s website and is published in the print edition of the journal.

Visualizing Health Policy: Barriers to Care Experienced by Women in the United States

This Visualizing Health Policy infographic looks at barriers to care experienced by women in the United States. Women incur greater health care costs than men, particularly during the reproductive years. Despite a lower uninsured rate than men (11% vs 14%), women are more likely to skip a recommended medical test or treatment due to cost. However, cost barriers to contraception have decreased for insured women since the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) coverage requirements took effect. Three of 4 women reported that insurance covered the full cost of birth control during their most recent visit. Younger women are less likely to report having a regular clinician. Women without a regular clinician are less likely to receive certain preventive services, such as a mammogram and Papanicolaou test. Women are more likely than men to have a preexisting health condition (29% vs 24%) and express concern about the consequences of lifting ACA protections that ban preexisting condition exclusions.

Visualizing Health Policy is an infographic series produced in partnership with the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The full-size infographic is freely available on JAMA’s website and is published in the print edition of the journal.

Disability and Technical Issues Were Key Barriers to Meeting Arkansas’ Medicaid Work and Reporting Requirements in 2018

Executive Summary

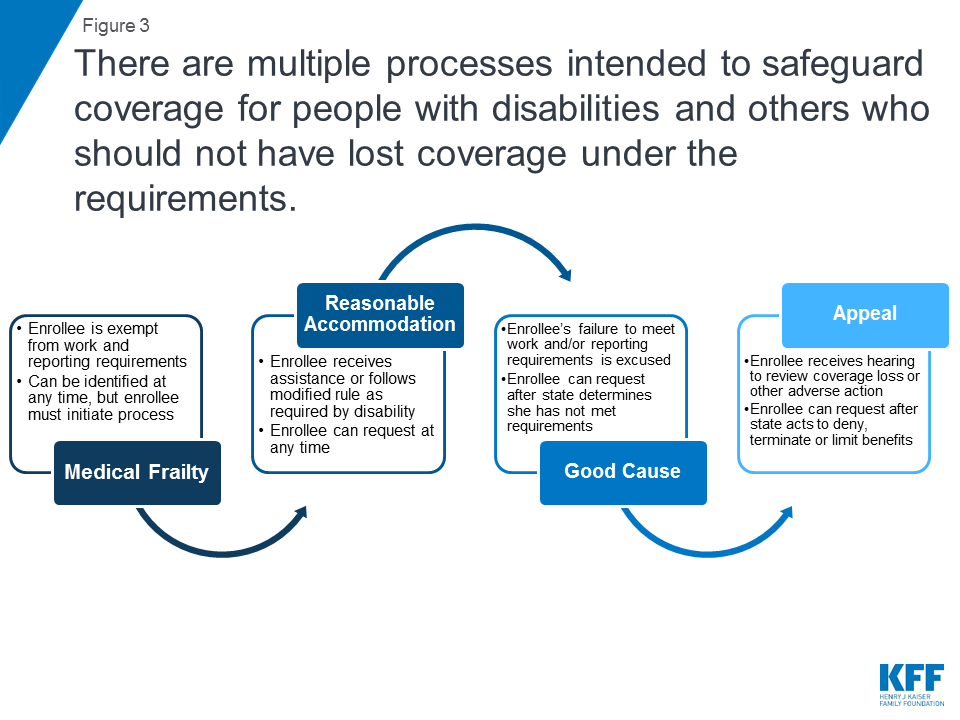

Over 18,000 people lost Medicaid coverage in Arkansas in 2018 due to the work and reporting requirements imposed under a Section 1115 demonstration waiver. There were four safeguards available to waiver enrollees that were intended to prevent people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the requirements from losing coverage. For example, the safeguards were intended to protect coverage for people who should not have been required to work due to a disability as well as for enrollees who did work the required number of hours but had difficulty navigating the monthly reporting process.

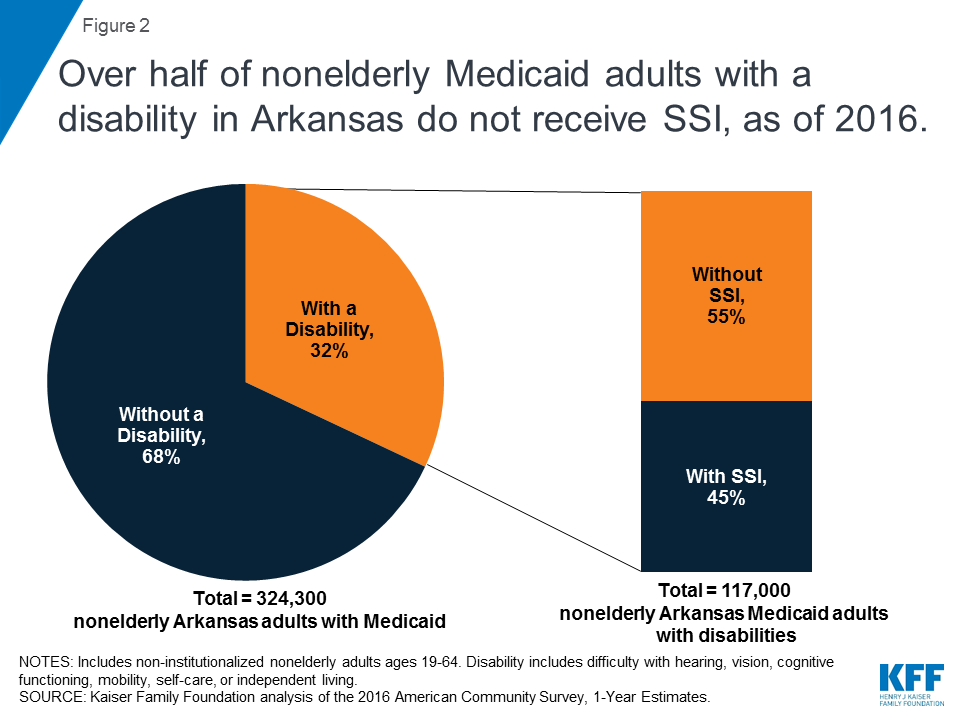

While proponents of the work and reporting requirements sometimes describe them as applying to “able-bodied” adults, some people with disabilities were subject to the requirements. Only people who receive federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits or are otherwise eligible for Medicaid based on a disability were entirely excluded from the requirements. Notably, 55% of nonelderly adults with Medicaid in Arkansas who report a disability do not receive SSI. At least some are eligible as ACA expansion adults and had to comply with the requirements or obtain an exemption to retain coverage under Arkansas’ waiver.

Two safeguards applied to protect coverage under the waiver for enrollees with disabilities. First, people with disabilities or health conditions that limited their ability to work were exempt from the requirements if they were determined to be “medically frail.” People with disabilities also could request a “reasonable accommodation” to receive assistance with meeting the requirements.

The other two safeguards applied to people with disabilities as well as other enrollees. Enrollees who were not exempt from the requirements and subsequently were determined to be non-compliant could have their status changed and be excused from the requirements by requesting a “good cause” exemption. Enrollees also could file an appeal to have a hearing to review the state’s decision to terminate their coverage under the new requirements.

This issue brief analyzes the impact of the four measures intended to safeguard coverage for people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the work and reporting requirements. It draws on data newly available from Arkansas’ 2018 annual waiver report to CMS and monthly data released by the state while the requirements were in effect. The data reveal that few people used these safeguard measures relative to the number of people who lost coverage due to the new requirements. Among those who accessed the safeguards, the vast majority did so due to disability/other health issues or technical issues such as those related to reporting. Key findings include the following:

- The four safeguards intended to protect coverage for people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the requirements are strikingly complex. Each safeguard has a different operational process and can be invoked at different times.

- Few enrollees utilized the processes intended to safeguard coverage relative to the over 18,000 people who lost coverage. While the medical frailty and good cause processes enabled some enrollees to retain the coverage for which they remained eligible, there were only 904 good cause requests, 17 reasonable accommodations, and 69 appeals in 2018. These low numbers may reflect a lack of enrollee knowledge about the safeguards and/or challenges navigating the required processes. Because over half of nonelderly adult Medicaid enrollees in Arkansas report a disability but do not receive SSI, it is likely that more enrollees qualified for relief from the requirements but did not navigate the process.

- People with disabilities were particularly vulnerable to losing coverage under the Arkansas work and reporting requirements, despite remaining eligible. As the requirements took effect, the share of enrollees identified as medically frail increased from 9% (about 2,200 people) in June to 14% (about 8,400 people) in December 2018. Still, this process did not identify all enrollees whose disabilities or health conditions prevented them from complying. Over one-third of approved good cause requests excused enrollees who had not been identified as medically frail from meeting the work or reporting requirements due to a disability or health issue.

- Administrative processes such as reporting requirements present barriers to eligible people retaining coverage beyond just those with disabilities. Over three-quarters of approved good cause requests excused enrollees from meeting the reporting requirement. This means that enrollees had completed the required number of hours but nevertheless initially had been found non-compliant because they were unable to successfully report. Technical issues were the most frequently cited basis for approved good cause requests, followed by enrollee disability or other health issues.

Looking ahead, the impact of measures intended to safeguard coverage for individuals with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to work and reporting requirements has implications for Arkansas as well as other states pursuing similar waivers. While the Arkansas requirements have been set aside by a court, they could be reinstated on appeal. The four safeguards are important protections to help eligible people remain covered, but their benefits may not have been fully realized due to the complexity of the processes. The extent of disability and technical issues, primarily related to reporting, experienced by those who ultimately were exempted from the requirements raises questions about whether additional individuals who lost coverage under the waiver might in fact remain eligible but were unable to retain coverage due to a disability or another difficulty navigating the reporting process.

Issue Brief

Introduction

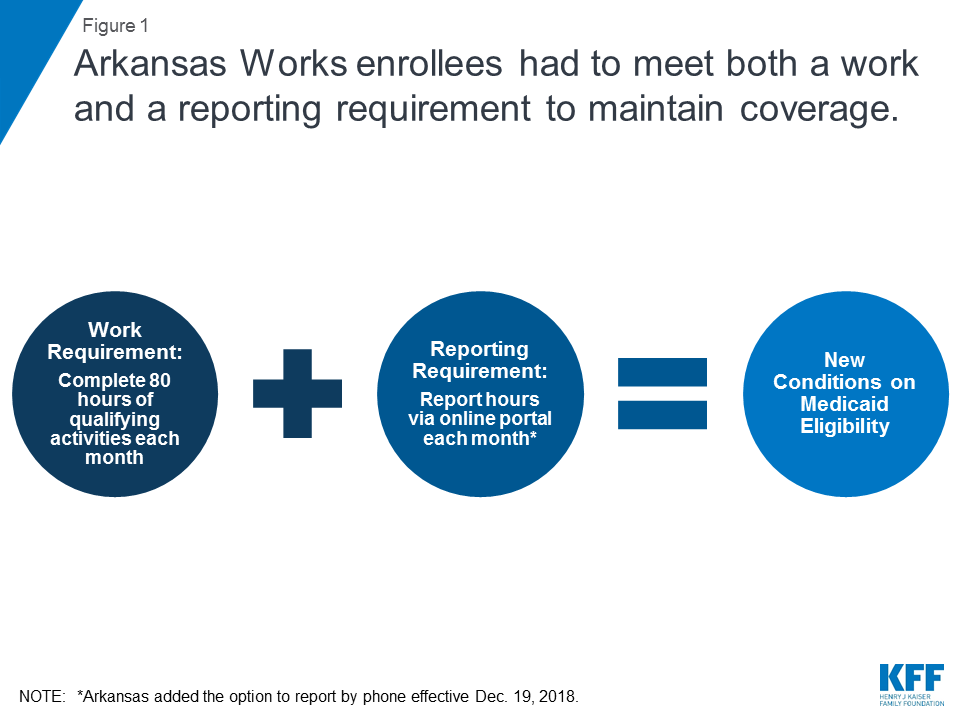

Over 18,000 people lost Medicaid coverage in Arkansas in 2018, due to work and reporting requirements imposed under a Section 1115 demonstration waiver known as Arkansas Works. The requirements were phased in for enrollees ages 30 to 49 from June through September 2018. Unless exempt, enrollees had to meet two separate but related requirements to maintain coverage: a requirement to complete 80 hours of work or other qualifying activities each month, and a requirement to report their hours each month (Figure 1). Individuals lost coverage after failing to meet the requirements for any three months in the calendar year. While the requirements started to apply to additional populations in 2019, no coverage losses have occurred this year to date because the requirements subsequently were set aside by a court; the case is currently on appeal.

This issue brief analyzes the impact of measures intended to safeguard coverage for people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the work and reporting requirements. It draws on data newly available from Arkansas’ 2018 annual waiver report to CMS and monthly data released by the state while the requirements were in effect. The data reveal that few people used these safeguard measures relative to the number of people who lost coverage due to the new requirements. Among those who accessed the safeguards, the vast majority did so due to disability/other health issues or technical issues, primarily related to reporting.

Background

While proponents of work and reporting requirements sometimes describe them as applying to “able-bodied” adults, some people with disabilities are subject to the requirements. Only people who receive federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits or are otherwise eligible for Medicaid based on a disability are entirely excluded from the requirements. However, 55% of nonelderly Medicaid adults in Arkansas who report a disability do not receive SSI (Figure 2 ).

Federal survey data classify a person as having a disability if they have a functional limitation that results in a participation limitation. This includes people who report serious difficulty with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (dressing or bathing), or independent living (doing errands, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping, alone).1 The SSI disability standard is more stringent.2 In addition, SSI financial eligibility criteria are more restrictive than those for Medicaid expansion adults and other disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways.3 As a result, people with disabilities who do not receive SSI can be eligible for Medicaid as expansion adults or low-income parents or through an optional disability-related pathway.4

Key Findings Related to Measures Intended to Safeguard Coverage

There were four safeguards that were intended to prevent people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the work and reporting requirements from losing coverage under Arkansas’ waiver (Figure 3). For example, the safeguards were intended to protect coverage for people who should not have been required to work due to a disability as well as for enrollees who did work the required number of hours but had difficulty navigating the monthly reporting process.

Two safeguards applied to protect coverage under the waiver for enrollees with disabilities. People with disabilities or health conditions that limited their ability to work were exempt from the requirements if they were identified as “medically frail.” People with disabilities also could request a “reasonable accommodation” to receive assistance or follow modified rules to meet the requirements.

The other two safeguards applied to people with disabilities as well as other enrollees who should not have lost coverage under the work and reporting requirements. Enrollees who were not exempt from the requirements and subsequently were determined to be non-compliant could have their status changed and ask the state to excuse them from meeting the requirements by submitting a “good cause” request. Enrollees also could file an appeal to have a hearing to review the state’s decision to terminate their coverage under the requirements.

The four safeguards intended to protect coverage for people with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the requirements are strikingly complex. Each safeguard has a different operational process and can be invoked at different times. More detail about each safeguard and related data about enrollee use of the safeguards is presented below.

Medical Frailty

People with disabilities or health conditions that limit their ability to work are exempt from Medicaid work and reporting requirements if they are identified as medically frail. Federal rules require that medically frail adults include at least those with disabling mental disorders, including serious mental illness; chronic substance use disorders; serious and complex medical conditions; physical, intellectual or developmental disabilities that significantly impair the ability to perform one or more activities of daily living; and those with a disability determination based on Social Security Administration criteria.5 In Arkansas, enrollees must self-identify as potentially medically frail to initiate the process.6 While health plans may have claims data or other information showing that an enrollee may be medically unable to work, health plans cannot initiate the medical frailty process in Arkansas. Final medical frailty determinations are made by the enrollee’s health plan and the state Medicaid agency and must be renewed annually.

Arkansas already was determining medical frailty before the work and reporting requirements took effect, but obtaining this status took on greater significance for enrollees under the new requirements than it had in the past. Previously, medically frail enrollees were exempt only from mandatory enrollment in Marketplace health plans and instead able to receive the traditional Medicaid benefit package. As the new requirements took effect, medically frail enrollees also became exempt from having to meet the work and reporting requirements as a condition of maintaining coverage. Although the notice sent to enrollees informing them that they are eligible for Medicaid and will be enrolled in a Marketplace health plan under Arkansas’ waiver must describe how to request a medical frailty determination,7 this information was not included in notices informing enrollees about the work and reporting requirements.8 In an early look at implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirements, some interviewees expressed concern about enrollees’ ability to understand that they potentially might qualify for a medical frailty exemption and to successfully navigate that process, especially for those with mental health needs. Safety net providers reported that individuals who are homeless and those who have more serious physical or mental health disabilities may be less likely to be aware of the requirements and more likely to have problems working or complying with monthly reporting.

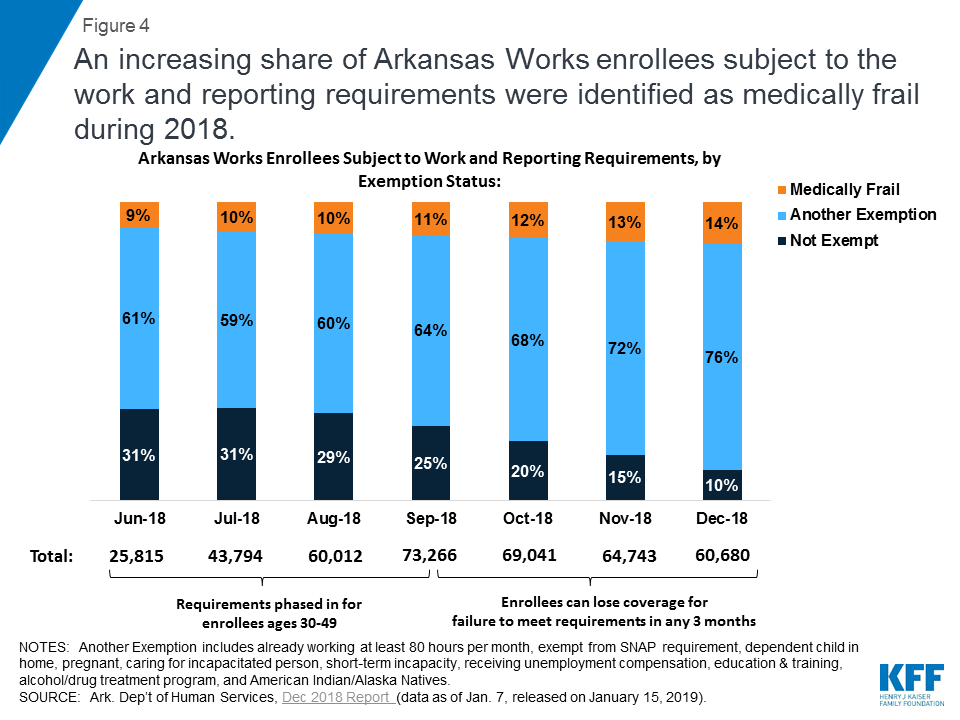

Among the subset of enrollees who were subject to the work and reporting requirements, an increasing share were identified as medically frail while the requirements were in effect (Figure 4). The work and reporting requirements did not apply to all waiver enrollees in 2018, but instead were phased in for enrollees ages 30 to 49 from June through September 2018. As the requirements took effect, the share of enrollees subject to the requirements who were identified as medically frail increased from 9% (about 2,200 people) in June to 14% (about 8,400 people) in December 2018. The share of enrollees who qualified for another exemption also increased during this period, leaving just 10% of enrollees not exempt by December.

Good Cause

Enrollees who were not exempt from the work and reporting requirements and subsequently were determined non-compliant could request that the state Medicaid agency grant them a good cause exemption, but very few (just over 900) did so relative to the over 18,000 people who lost coverage. The state could decide that an enrollee had good cause for not completing the required number of work activity hours and/or not reporting their hours or an exemption. Circumstances that constituted good cause included those related to an enrollee’s disability or health condition as well as other reasons. At a minimum, under Arkansas’ waiver, good cause exemptions had to be recognized for enrollees who were unable to meet the requirements for reasons related to a disability, hospitalization, or serious illness experienced by themselves or an immediate family member with whom they live; the birth or death of a family member in the enrollee’s home; severe inclement weather including natural disasters; and a family emergency or other life-changing event such as divorce or domestic violence.9

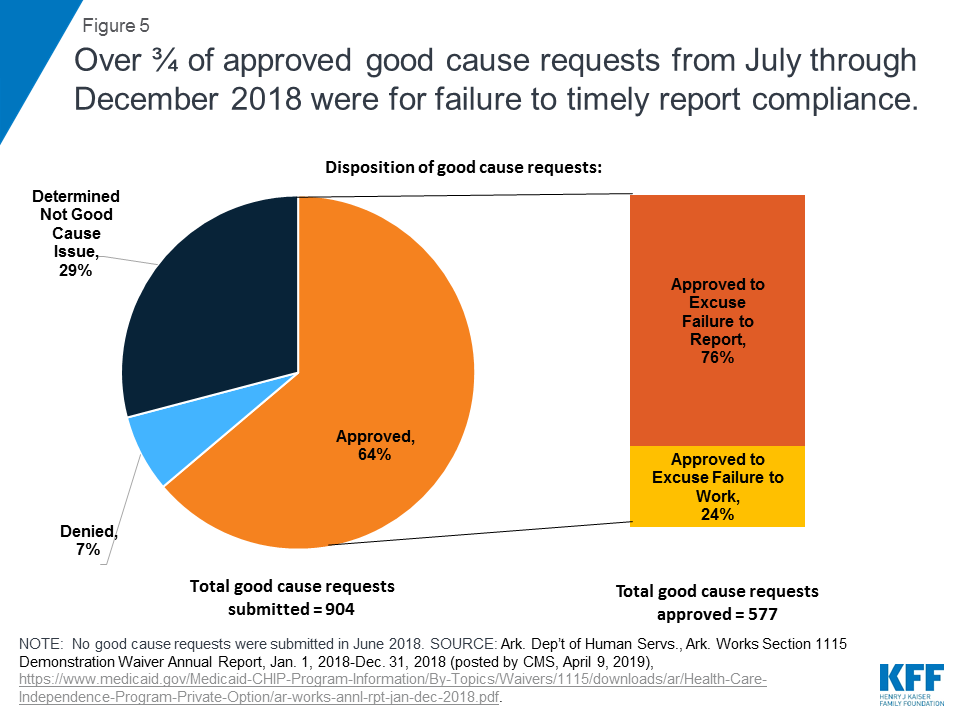

Nearly two-thirds of the 904 good cause requests received from July through December 2018 were approved, with most approvals excusing enrollees from meeting the reporting requirement (Figure 5). This means that these enrollees had successfully completed the required number of work activity hours in a given month but nevertheless initially had been found non-compliant because they were unable to successfully report that they had done so. The remaining good cause approvals excused enrollees from completing the required number of work activity hours in a given month. Most good cause requests that were not approved were determined by the state to “not constitute a good cause issue.” No further information is available about these requests. By contrast, a smaller number of good cause requests were formally denied.

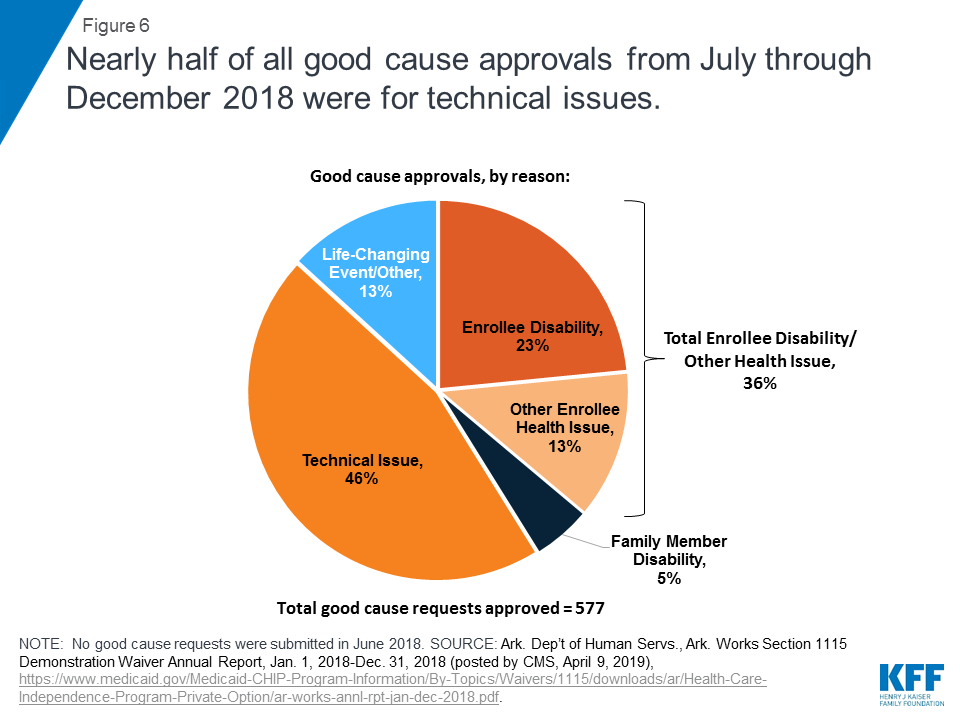

Among the good cause requests approved by the state, just under half were attributed to technical issues (Figure 6 and Table 1). These included client support issues, agency issues, and other unspecified technical issues. In the subset of good cause approvals related to the reporting requirement, technical issues were the chief reason that enrollees were excused from meeting the reporting requirement (Table 1). This finding is consistent with other research that shows that additional reporting or administrative burdens create barriers to eligible people retaining coverage. In addition, technical issues were the second most frequently cited reason in the subset of good cause approvals excusing enrollees from meeting the work requirement (Table 1).

| Table 1: Arkansas Works Good Cause Approvals, by Reason, July-December 2018 | |||

| Good Cause Reason | Share of All Good Cause Approvals | Share of Good Cause Approvals to Excuse Work Hours | Share of Good Cause Approvals to Excuse Reporting |

| Technical Issue | 46% | 17% | 55% |

| Enrollee Disability | 23% | 56% | 13% |

| Other Enrollee Health Issue | 13% | 9% | 14% |

| Family Member Disability | 5% | 7% | 4% |

| Life-Changing Event/Other | 13% | 11% | 14% |

| Total: | 100% (577 requests) | 100% (140 requests) | 100% (437 requests) |

| NOTES: Work and reporting requirements were phased in for enrollees ages 30-49 from June-December 2018, but no good cause requests were submitted in June. Other Enrollee Health Issue includes hospitalization and serious illness. Technical Issue includes technical agency issue, technical client support, and unspecified technical issues. Life Changing Event/Other also includes birth or death of household family member.SOURCE: Ark. Dep’t of Human Servs., Ark. Works Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver Annual Report, Jan. 1, 2018-Dec. 31, 2018 (posted by CMS, April 9, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-works-annl-rpt-jan-dec-2018.pdf | |||

Over one-third of all approved good cause requests were attributed to enrollee disability or another health issue, such as hospitalization or serious illness (Figure 6 and Table 1). This means that these enrollees were determined to have physical or mental health issues that prevented them from working the required number of hours or reporting their compliance, even though they had not previously been identified as medically frail and do not receive SSI benefits. This finding is consistent with research finding that people who are penalized for not meeting the TANF work requirement are more likely to have a disability compared to those who are not so penalized. In the subset of good cause approvals related to the work requirement, disability/health issues were the chief reason that enrollees were excused from completing the required number of hours (Table 1). In addition, disability/health issues were the second most frequently cited reason in the subset of good cause approvals excusing enrollees from meeting the reporting requirement (Table 1).

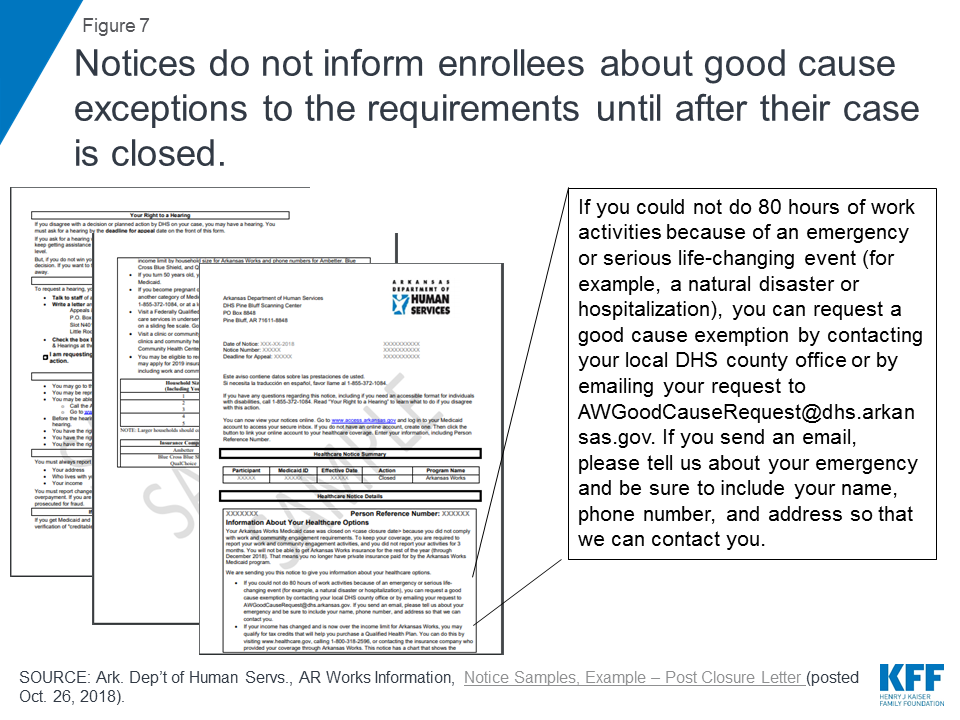

Not all enrollees who were eligible for a good cause exemption may have requested one. Just over 900 good cause requests were submitted, while over 18,000 enrollees lost coverage under the work and reporting requirements in 2018. An early look at implementation of the work and reporting requirements in Arkansas found that the good cause policies and process were not finalized until fall 2018, resulting in confusion about how to make these requests. Information about the good cause process was included in the notice informing enrollees that their case was closed due to three months of non-compliance (Figure 7), but this information was not included in earlier notices about the work and reporting requirements. In addition, the notice language describing good cause referred to “an emergency or serious life-changing event (for example, a natural disaster or hospitalization)” but did not include the broader list of good cause reasons that Arkansas must recognize, such as disability or serious illness (that may not have resulted in a hospitalization but nonetheless interfered with the enrollee’s ability to meet the requirements) as described above. Finally, the process for requesting good cause differed from the process to report work hours and exemptions; instead of using the online portal, good cause was requested via email.

Reasonable Accommodations

Arkansas received and granted very few — a total of 17 — reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities from June through December 2018, primarily for help using the online portal to report compliance.10 The state data do not indicate whether any support services necessary for people with disabilities to participate in the work and reporting requirements were provided. While federal Medicaid funds cannot be used to pay for supportive services in work requirement waivers, the state has an independent obligation to provide equal access to people with disabilities under other federal laws. As required by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, and Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, Arkansas had to provide reasonable accommodations to ensure that enrollees with disabilities had an equal opportunity to meet the work and reporting requirements. Examples of reasonable accommodations in the waiver terms approved by CMS included but were not limited to assistance with demonstrating eligibility for good cause exemptions; appealing disenrollments; documenting work activities and other documentation requirements; understanding notices and program rules related to community engagement requirements; navigating ADA compliant web sites; exemptions from participation where an individual is unable to participate or report for disability-related reasons; modification in the number of hours of participation required; and provision of support services necessary to participate.11

The very low number of these requests likely reflects a lack of knowledge among enrollees about the availability of reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities. For example, the notices sent to enrollees about the work and reporting requirements did not include information about the availability of reasonable accommodations or how to request them.12 While enrollees generally must initiate the request for a reasonable accommodation, the waiver terms and conditions also provided that the “state should evaluate individuals’ ability to participate and the types of reasonable modifications and supports needed.”13 No information about these efforts is provided in the state’s 2018 annual waiver report to CMS.

Appeals

A total of just 69 people requested an appeal related to the work and reporting requirements from June through December 2018,14 a fraction of the over 18,000 enrollees who lost coverage under the requirements. This could indicate that individuals do not know about appeals, are unable to successfully navigate the process, or believe that filing an appeal is futile. No information was provided about the outcome of requested appeals. While information about how to request an appeal was included in the notices, an early look at implementation of the work and reporting requirements in Arkansas found concerns among advocates and providers that the notices were confusing and may not have sufficiently accounted for low literacy and lack of English proficiency among some enrollees. Focus groups conducted in fall 2018 revealed that enrollees did not fully read or understand the notices. Many enrollees said that they did not focus on the notices because they had to attend to more immediate and pressing needs, such as alcoholism recovery or meeting basic needs like affording food and utility bills.

Looking Ahead

The impact of the measures intended to safeguard coverage for individuals with disabilities and others who should not have been subject to the work and reporting requirements has implications for Arkansas as well as other states pursing similar waivers. While the Arkansas requirements, along with those in Kentucky, have been set aside by a court, they could be reinstated on appeal. In addition, work and reporting requirements currently are in effect in Indiana and New Hampshire, although the New Hampshire requirements also are being challenged in court. Other states have or are actively seeking CMS approval to implement similar requirements, and the Trump Administration’s FY 2020 budget includes a proposal to adopt these requirements across the Medicaid program.15

Few enrollees used the safeguards relative to the number who lost coverage, likely at least in part due to the safeguards’ complexity. While the medical frailty and good cause processes enabled some enrollees to retain the coverage for which they remained eligible, there were few good cause requests (about 900) relative to the number of enrollees who lost coverage in 2018 (over 18,000). Even fewer enrollees requested a reasonable accommodation (17) or requested an appeal (69) related to the work and reporting requirements. These low numbers may reflect a lack of knowledge among enrollees about the availability of these safeguards and/or challenges successfully navigating the required processes. Each safeguard had a different operational process and can be invoked at different times. Because over half of nonelderly Medicaid adults in Arkansas repot a disability but do not receive SSI, it is likely that more enrollees qualified for relief from the requirements but did not navigate the process.

People with disabilities were particularly vulnerable to losing coverage under the work and reporting requirements, despite remaining eligible. An increasing share of Arkansas enrollees subject to the work and reporting requirements were identified as medically frail and therefore exempt from complying while the requirements were implemented. Still, this process did not identify all enrollees whose disabilities or health conditions prevented them from complying, as over one-third of good cause requests approved to excuse enrollees from meeting the work or reporting requirements were based on a disability or another enrollee health issue.

Administrative processes such as reporting requirements present barriers to eligible people retaining coverage beyond just those with disabilities. Over three-quarters of approved good cause requests excused enrollees from the reporting requirement. This means that these enrollees had successfully completed the required number of work activity hours in a given month but nevertheless initially had been found non-compliant because they were unable to successfully report that they had done so. Technical issues were the most frequently cited basis for approved good cause requests, followed by enrollee disability or other health issues.

The four safeguards are important protections to help eligible people remain covered, but their benefits may not have been fully realized due to the complexity of the processes. The extent of disability and technical issues, primarily related to reporting, experienced by those who ultimately were exempted from the requirements raises questions about whether additional individuals who lost coverage under the waiver might in fact remain eligible but were unable to retain coverage due to a disability or another difficulty navigating the reporting process.

Endnotes

- U.S. Census Bureau, How Disability Data are Collected from the American Community Survey, (Oct. 17, 2017), https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html. ↩︎

- SSI beneficiaries have an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of old age or significant disability. ↩︎

- The maximum SSI benefit is 74% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $9,252/year for an individual in 2019), and the asset limit for an individual is $2,000. The ACA Medicaid expansion covers individuals up to 138% FPL ($17,236/year for an individual in 2019) without an asset test in states that opt to adopt it. States also have the option to extend financial eligibility for disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways up to 300% of SSI ($27,756/year for an individual in 2019). ↩︎

- People who qualify for Medicaid both as an expansion adult and based on a disability can choose the group through which they enroll in coverage; benefit packages may differ by coverage group. 42 C.F.R. § 435.911 (c) (2), (d). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.315 (f). ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities: Findings from a 50-State Survey (June 2019). ↩︎

- CMS Special Terms and Conditions, Arkansas Works, No. 11-W-00287/6 (approval period March 5, 2018 through Dec. 31, 2021, amended March 5, 2018), at p. 14, 23 (f) regarding Arkansas Works Premium Assistance Enrollment Notices (providing that the “notice will include information describing how Arkansas Works beneficiaries who believe they are medically frail can request a determination of whether they are exempt from the ABP. The notice will also include alternative benefit plan options.”), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/ar-works-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- Enrollees who were subject to the work and reporting requirements were sent a notice the month before, indicating when their work requirement began and that, unless they received another notice saying that they were exempt from reporting, they had to report their work activities by the fifth of the following month or would be considered non-compliant and would lose coverage after three months of non-compliance. AR Works Information, Notices and Flyer Samples, Example – Subject to Work Requirement – Work Activities, last accessed Oct. 5, 2018, on file with author. ↩︎

- CMS Special Terms and Conditions, Arkansas Works, No. 11-W-00287/6 (approval period March 5, 2018 through Dec. 31, 2021, amended March 5, 2018), at p. 21-22, 53, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/ar-works-ca.pdf; see also Ark. Medical Servs. Pol’y Manual, Section F-201, Good Cause Exemptions (May 1, 2018). ↩︎

- Ark. Dep’t of Human Servs., Ark. Works Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver Annual Report, Jan. 1, 2018-Dec. 31, 2018 (posted by CMS, April 9, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-works-annl-rpt-jan-dec-2018.pdf. ↩︎

- CMS Special Terms and Conditions, Arkansas Works, No. 11-W-00287/6 (approval period March 5, 2018 through Dec. 31, 2021, amended March 5, 2018), at p. 20-21, 51-52, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/ar-works-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- AR Works Information, Notices and Flyer Samples, Example – Subject to Work Requirement – Work Activities, last accessed Oct. 5, 2018, on file with author. ↩︎

- CMS Special Terms and Conditions, Arkansas Works, No. 11-W-00287/6 (approval period March 5, 2018 through Dec. 31, 2021, amended March 5, 2018), at p. 20-21, 52, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/ar-works-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- Ark. Dep’t of Human Servs., Ark. Works Section 1115 Demonstration Waiver Annual Report, Jan. 1, 2018-Dec. 31, 2018 (posted by CMS, April 9, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ar/Health-Care-Independence-Program-Private-Option/ar-works-annl-rpt-jan-dec-2018.pdf. ↩︎

- U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Budget in Brief, Putting America’s Health First, FY 2020 President’s Budget for HHS, at p. 100, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2020-budget-in-brief.pdf. ↩︎

Women on Medicaid in 35 States and DC Have Extremely Limited Abortion Coverage Due to Hyde Amendment

Source

Coverage for Abortion Services in Medicaid, Marketplace Plans and Private Plans

Low-income Californians and Health Care

Introduction

Introduction

Despite its large economy, California is also the state with the highest poverty rate (19 percent) according to the U.S. Census Bureau.1 As Governor Gavin Newsom begins his tenure in office, Californians across income groups see health care as a key issue for the new governor and legislature to address. In late 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation conducted a representative survey of the state’s residents to gauge their views on health policy priorities and their experiences in California’s health care system. This summary examines key findings from the survey among “low-income” Californians, defined here as those whose self-reported incomes are below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (approximately $49,000 for a family of four). Where relevant, they are compared to higher-income Californians — those with self-reported incomes at or above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Half of low-income Californians say that someone in their family has delayed or forgone medical or dental treatment in the past year due to costs, this @KaiserFamFound / @CHCFNews survey finds.

Overall, the survey finds that while Californians at all income levels see health care as an important priority for the governor and legislative leaders to work on, health care affordability and access emerge as particularly prominent concerns among low-income residents of the state. Key findings include:

- Affordability of health care has affected treatment decisions for many low-income Californians, with over half saying that in the past year, they or someone in their family has delayed or forgone some type of medical or dental treatment due to costs.

- Californians with low incomes are almost twice as likely as higher-income residents to say they have had problems paying medical bills. As a result, many of those who experienced difficulty paying medical bills say they have had to cut back spending in other areas, use savings, or borrow money.

- Low-income Californians are also more likely than other residents to report nonfinancial barriers to accessing health care, such as long wait times to get an appointment. A majority of Californians with low incomes say their community does not have enough mental health providers, and about four in ten say their community lacks enough primary care doctors and specialists to meet the needs of residents.

- The distinctive health care experience of low-income Californians is also evident in their attitudes toward Medi-Cal. While overwhelming majorities of Californians across income levels say Medi-Cal is important to the state, low-income Californians are twice as likely as those with higher incomes to say the program is important to them and their families.

Findings

Health Care Priorities

When asked about a number of health care issues facing the state and its residents, Californians with low incomes say most are important priorities for state political leaders to address. About half of low-income Californians say that it is “extremely important” for the governor and the legislature to work on making sure people with mental health problems can get treatment (51 percent) and to work on making sure all Californians have access to health insurance (49 percent). Nearly half say it is “extremely important” that the governor and legislature work on lowering the amount people pay for health care (46 percent) and on making sure there are enough health care providers across the state (46 percent). Sixteen percent of Californians with low incomes think it is “extremely important” for state leaders to work on decreasing state spending on health care (Figure 1). While ratings of health care priorities are similar across income levels, Californians with low self-reported incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to say making sure there are enough health care providers across the state should be an “extremely important” priority for state leaders (46 percent versus 33 percent [not shown]).

Experiences with Health Care Affordability

Californians with low incomes are nearly twice as likely as those with higher incomes to say they or a household member had problems paying medical bills in the past 12 months (29 percent versus 15 percent) (Figure 2).

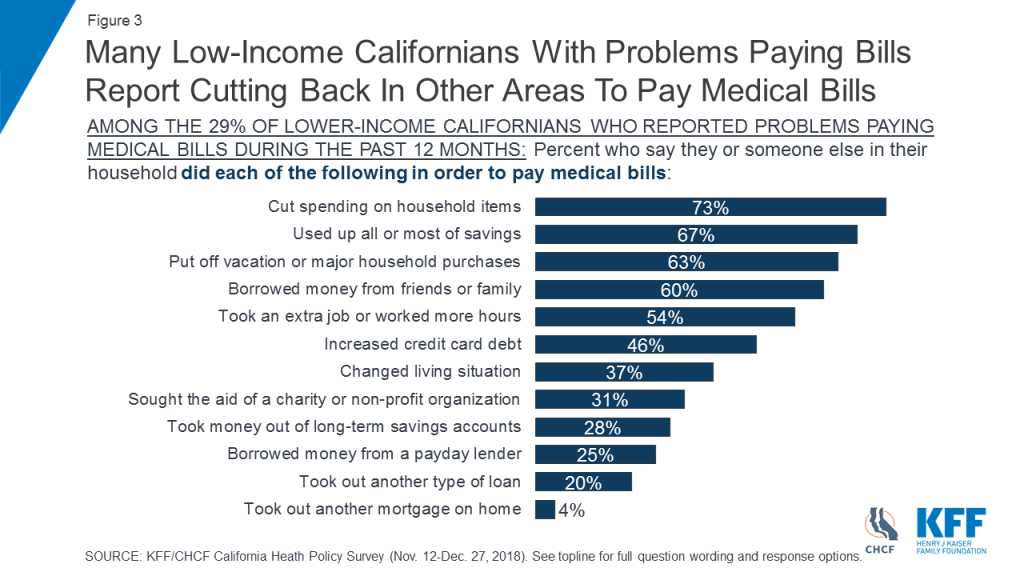

Many Californians with low incomes who had problems paying medical bills report having to cut back in other areas, dip into savings, or borrow money to help address their medical costs. Among the 29 percent of low-income Californians who report problems paying medical bills, nearly three-quarters (73 percent) say they have cut spending on household items to pay medical bills. Two-thirds (67 percent) say they used up all or most of their savings and about six in ten say they put off a vacation or major purchase (63 percent) or borrowed money from friends or family (60 percent) (Figure 3).

More than half of Californians with low incomes (55 percent) say that they or a family member living in their household delayed or went without some type of medical or dental care in the past year because they had difficulty affording the cost. This compares to 36 percent of those with higher incomes (not shown). Four in ten low-income Californians say someone in their household skipped dental care or checkups, 28 percent say they or a household member put off or postponed getting health care, and about a quarter say someone in their household skipped a recommended test or treatment (24 percent) or did not fill a prescription (24 percent) because of cost (Figure 4).

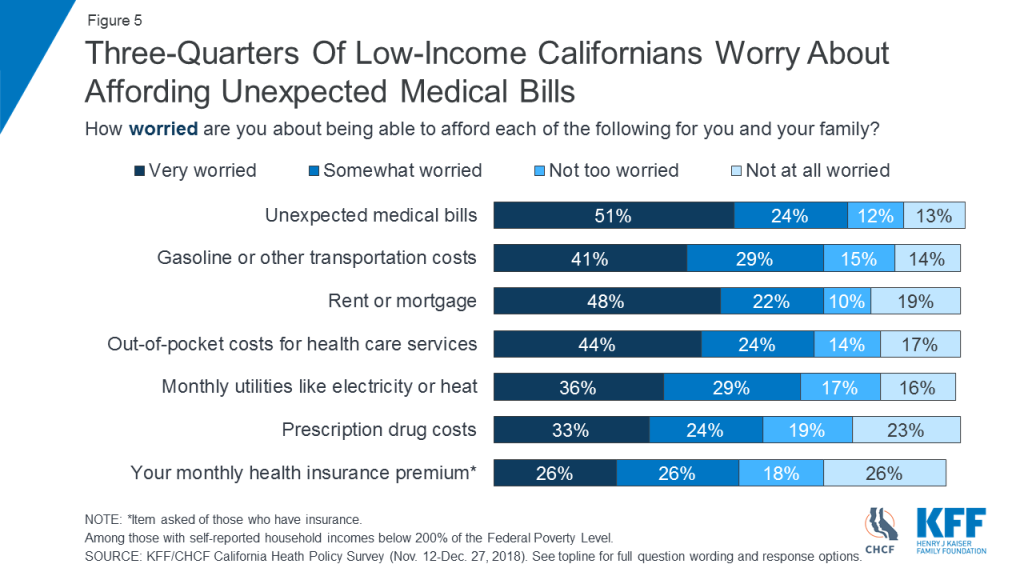

Three in four low-income Californians (75 percent) say they are very or somewhat worried about being able to afford unexpected medical bills, outranking other financial worries asked about in the survey, including paying for housing. Nearly seven in ten (68 percent) say they are worried about affording out-of-pocket costs for health care services (Figure 5).

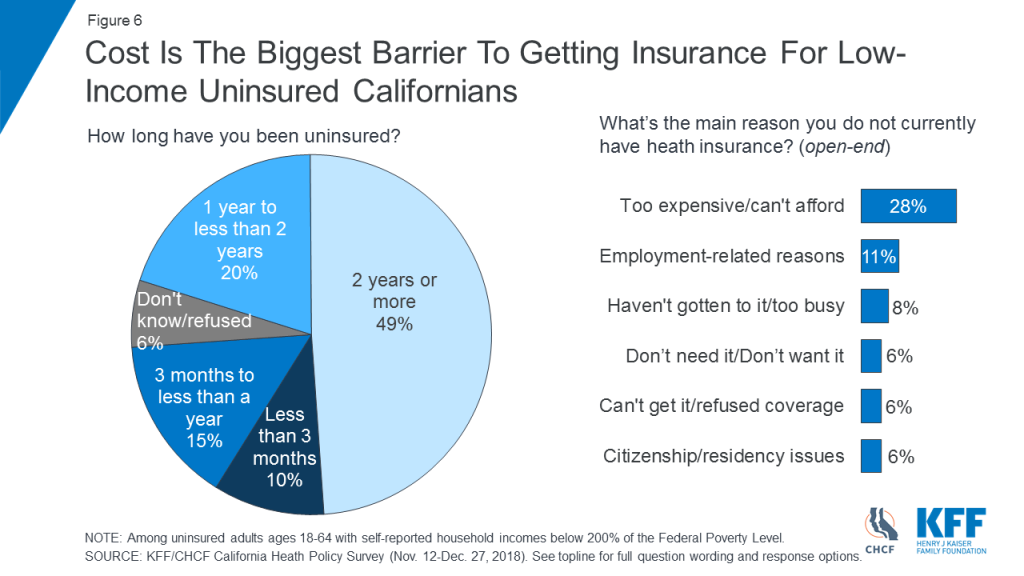

Cost concerns are also evident among low-income adults who are uninsured. Among uninsured Californians age 18–64 with low incomes, about half (49 percent) say they have been without health insurance for two years or more, and cost and affordability (28 percent) is the top reason cited for why they lack insurance (Figure 6).

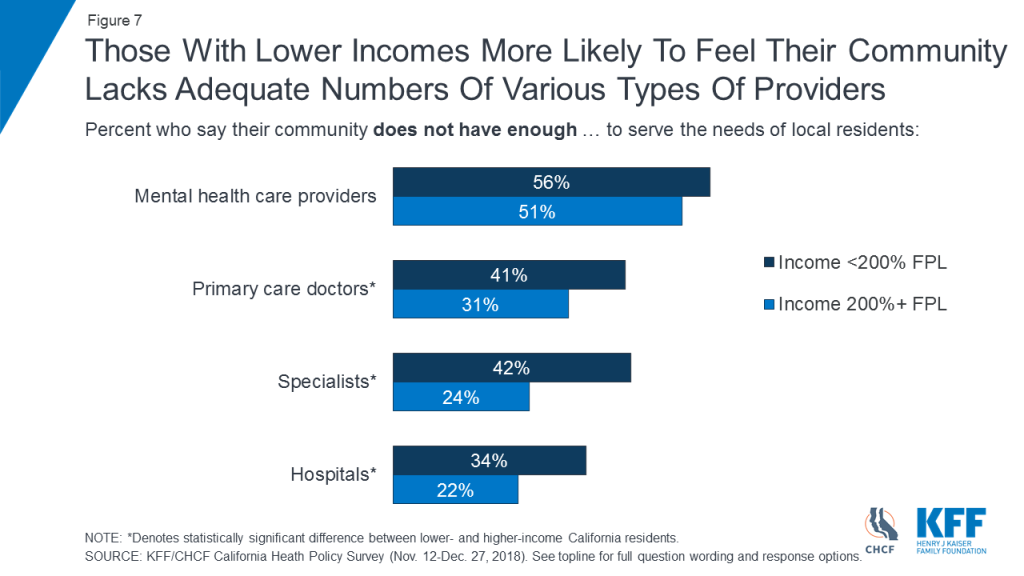

Access to Providers

A majority of low-income Californians (56 percent) say their community does not have enough mental health care providers to serve the needs of local residents. Those with low incomes are more likely than Californians with higher incomes to say their community does not have enough primary care doctors (41 percent versus 31 percent), specialists (42 percent versus 24 percent), and hospitals (34 percent versus 22 percent) (Figure 7).

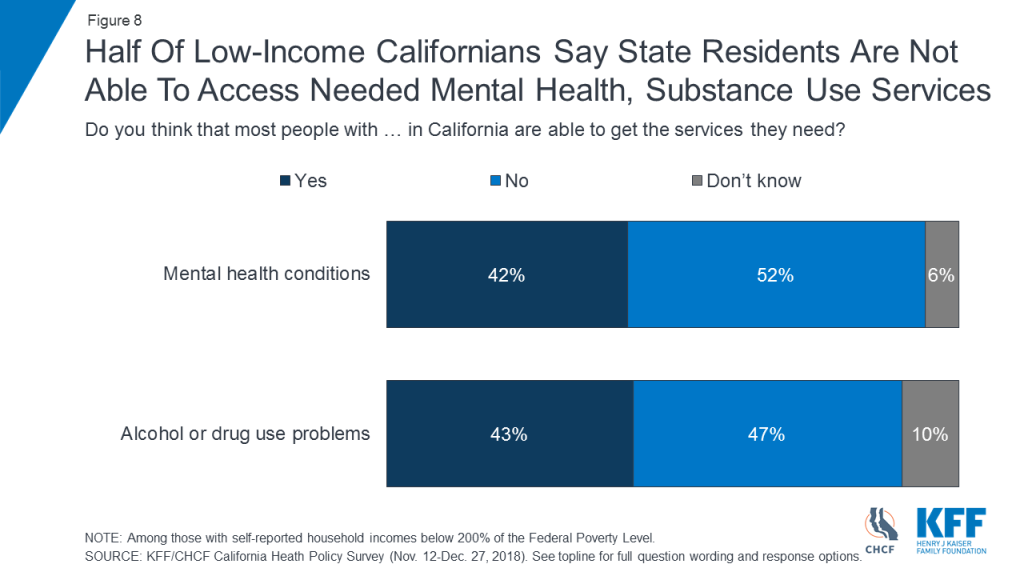

About half of Californians with low incomes (52 percent) say most people in the state with mental health conditions are not able to get the services they need. A similar share (47 percent) say those with alcohol or drug use problems in California are not able to get needed services (Figure 8).

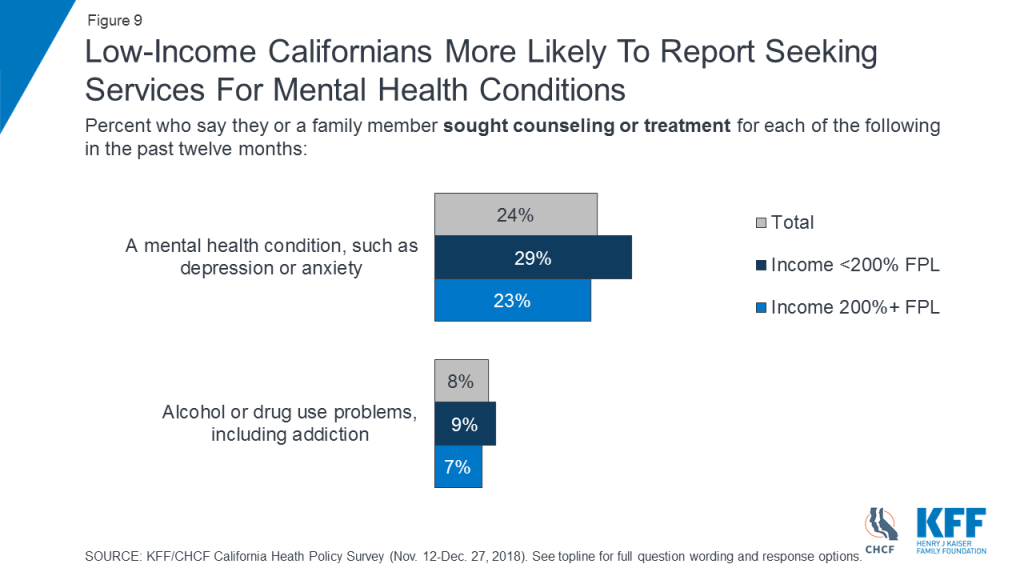

Similar shares of Californians across income levels say they or a family member have sought counseling or treatment for alcohol or drug use (Figure 9).

Californians with low incomes are slightly more likely than those with higher incomes to say they or a family member sought counseling or treatment for a mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression, in the past twelve months (29 percent versus 23 percent) (Figure 9).

Among Californians with low incomes, concerns about availability and access to providers are reflected in their personal experiences. About a quarter of low-income residents (27 percent) say there was a time in the past 12 months when they had to wait longer than they thought reasonable to get an appointment for medical care. Among low-income adults who say they or a family member sought mental health treatment in the past year, 27 percent said they had to wait longer than they thought reasonable for a mental health care appointment (Figure 10).

Among low-income Californians with Medi-Cal coverage who say they or a family member sought care, 33 percent report having to wait longer than they thought reasonable for a medical care appointment and four in ten (41 percent) say they had to wait longer than reasonable for a mental health care appointment (Figure 10).

Importance of Medi-Cal

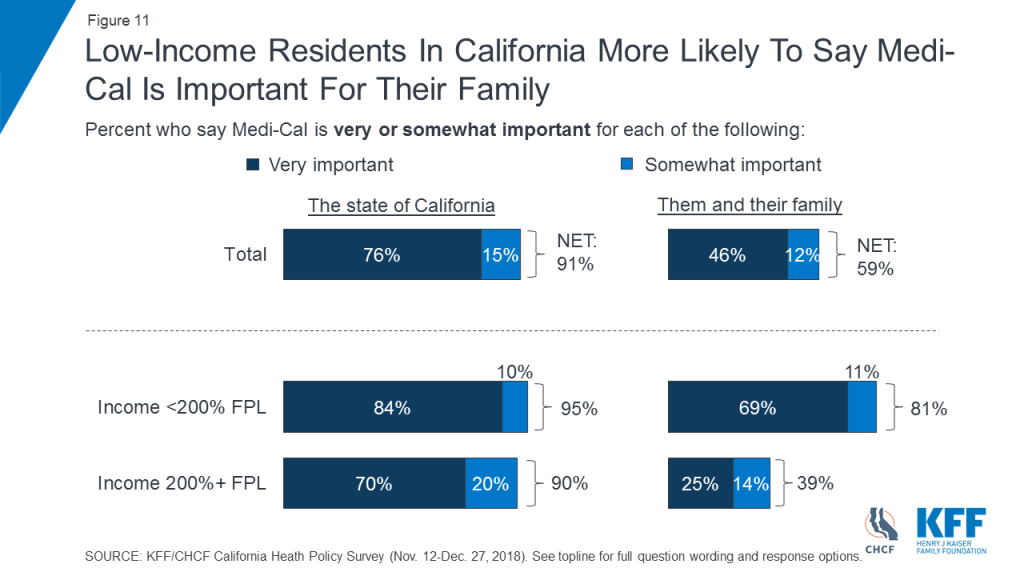

An overwhelming majority of low-income Californians say Medi-Cal is “very important” (84 percent) or “somewhat important” (10 percent) to the state. Eight in ten (81 percent) say it is either “very important” (69 percent) or “somewhat important” (11 percent) to them and their family. While an overwhelming majority of Californians with higher incomes also see Medi-Cal as important to the state (90 percent), they are less likely than those with low incomes to say the program is important to their own families (39 percent versus 81 percent) (Figure 11).

Survey Methodology

The Kaiser Family Foundation/California Health Care Foundation California Health Policy Survey was conducted by telephone November 12 – December 27, 2018, among a random representative sample of 1,404 adults age 18 and older living in the state of California (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Figures in the report may not add to 100 due to rounding. Interviews were administered in English and Spanish, combining random samples of both landline (476) and cellular telephones (928, including 668 who had no landline telephone). Sampling, data collection, weighting and tabulation were managed by SSRS in close collaboration with Kaiser Family Foundation and California Health Care Foundation researchers. The California Health Care Foundation paid for the costs of the survey fieldwork, and Kaiser Family Foundation contributed the time of its research staff. Both partners worked together to design the survey and analyze the results.

The sampling and screening procedures were designed to increase the number of Black and Asian-American respondents and low-income respondents, including those who have health insurance through Medi-Cal or who are uninsured. This oversample allowed for sufficient numbers of respondents in these subgroups to report their results separately; weighting adjustments were made to adjust their proportions to represent their actual shares of the population in overall results (see weighting description below). The sample included 463 respondents who were reached by calling back respondents in California who had previously completed an interview on either the SSRS Omnibus poll or the Kaiser Health Tracking Polls and indicated they fit one of the oversample criteria (Black, Asian, or low-income respondents, including low-income respondents with Medi-Cal or who are uninsured, and are living in California). It also included 46 respondents with prepaid (or pay-as-you-go) cell phone numbers in California, a group that is disproportionately lower-income.

The dual frame cellular and landline phone sample was generated by Marketing Systems Group (MSG) using random digit dial (RDD) procedures. The RDD frames were stratified by income-level in order to reach more low-income respondents. To address the fact that some qualifying respondents could be reached only by their cell-phone but had an out-of-state phone number, the sample was augmented with a sample of phone numbers outside of California associated with a billing address that indicated in-state residence (n=89). Survey Sampling International (SSI) generated these numbers randomly using Smart Cell sample. All respondents were screened to verify that they resided in California. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the qualifying adult who answered the phone.

A multi-stage weighting design was applied to ensure an accurate representation of the California adult population. The first stage of weighting involved corrections for sample design, including accounting for the components, the likelihood of non-response for the re-contacted sample, and an adjustment to account for the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection. In the second weighting stage, demographic adjustments were applied, at first, to the RDD and Smart Cell sample to account for systematic non-response along known population parameters. Population parameters included gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity (broken down by nativity), educational attainment, phone status (cell phone only or reachable by landline), and state region. Demographic parameters were based on estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), and telephone use was based on data for California from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. Based on this second stage of weighting, estimates were derived for self-reported income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (less than 200%, 200% or higher) by insurance status (Medi-Cal, uninsured, all else) in the California population. The last stage of weighting included all respondents and used poverty level by insurance status, based on the previous stage’s outcomes, as an additional weighting parameter.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of interviews and margins of sampling error for the subgroups analyzed in this report are shown in the table below. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E |

| Total | 1,404 | ±3 percentage points |

| <200% FPL | 724 | ±4 percentage points |

| 200% FPL+ | 553 | ±5 percentage points |

| <200% FPL & Medi-Cal (<65) | 281 | ±7 percentage points |

| <200% FPL & Uninsured (<65) | 125 | ±10 percentage points |

Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Endnotes

- The supplemental poverty measure takes into account government programs which assist low-income individuals and expenditures of food, clothing, shelter, and utilities. Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2017. (September 2018). Retrieved April 2019, from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-265.pdf ↩︎

Less Than One-Third of New Medicare Beneficiaries Enrolled in Medicare Advantage During Their First Year on Medicare

The Share Varies Considerably Across States and Counties

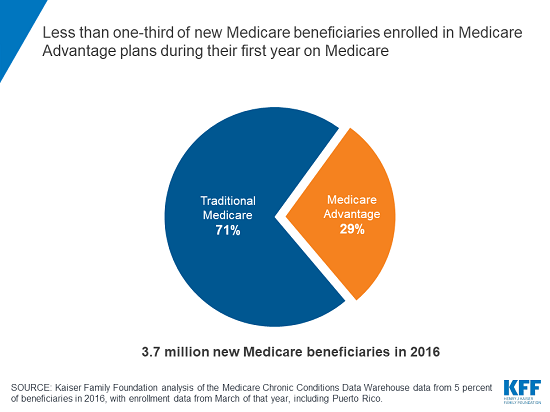

Twenty-nine percent of new beneficiaries chose to enroll in Medicare Advantage during their first year in Medicare in 2016, finds a new KFF analysis.

That level generally matches the overall share of beneficiaries who opted for Medicare Advantage that year, but does not support the view that the aging Baby Boom generation, having had more experience with HMOs and PPOs during their working years, would select the private plans over traditional Medicare at relatively high rates. In fact, the share of new beneficiaries choosing Medicare Advantage has increased only modestly over the years.

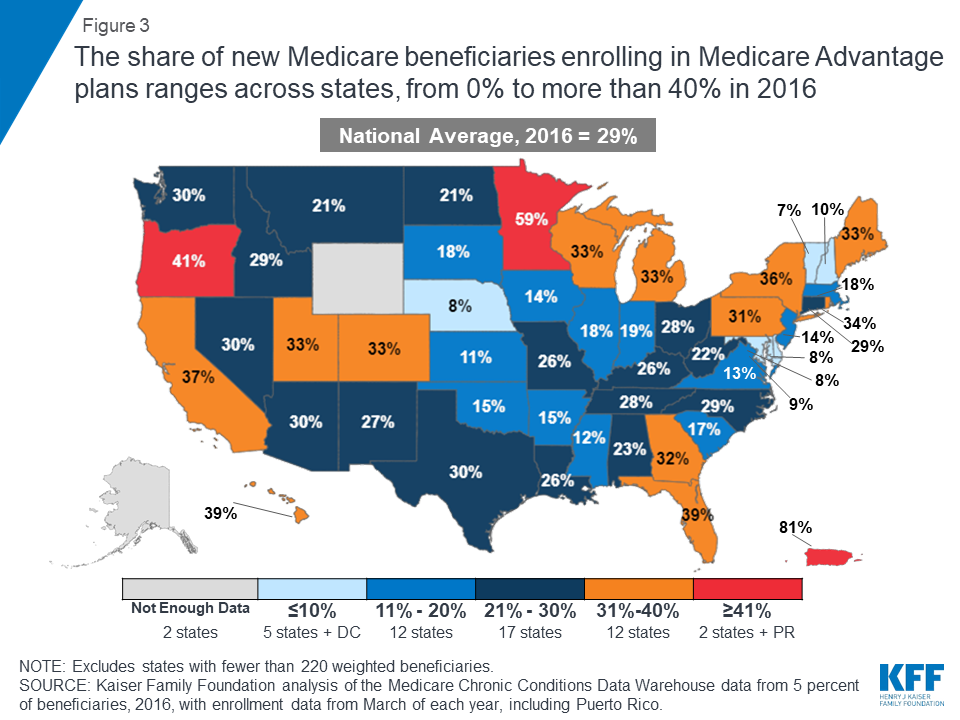

The share choosing Medicare Advantage in their first year varies considerably across states and counties, however. Less than 11 percent of new beneficiaries picked Medicare Advantage in Delaware, Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Vermont and the District of Columbia, to cite a few examples, while more than 40 percent selected such plans in Oregon and Minnesota.

The analysis examines Medicare Advantage enrollment rates among new beneficiaries over time, by geographic location and according to age and other characteristics of enrollees.

A second, updated analysis of Medicare Advantage provides 2019 data on enrollment, premiums and out-of-pocket limits. In 2019, 34 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries, or 22 million people, are enrolled in the private plans.

For more on Medicare Advantage, including our newly updated fact sheet, visit kff.org.

What Percent of New Medicare Beneficiaries Are Enrolling in Medicare Advantage?

Data Note

People new to Medicare can receive their Medicare benefits through either traditional Medicare or private plans, such as HMOs or PPOs, known as Medicare Advantage plans. Older adults and younger beneficiaries with disabilities have said that they make this choice based on premiums and out-of-pocket costs, access to desired providers, the reputation of the company offering the plan, ads and other marketing materials, and the advice of brokers, family members and friends.1 Medicare Advantage offers one-stop shopping, with all Medicare benefits in one combined package, and enrollees may have lower out-of-pocket costs than those in traditional Medicare, with an out-of-pocket cap and coverage of some additional benefits, such as eyeglasses. Beneficiaries in traditional Medicare have open access to providers and fewer administrative hassles, such as prior authorization and referral requirements.2

One line of thinking has been that the Baby Boom Generation will enroll in Medicare Advantage plans over traditional Medicare at much higher rates than prior generations because they have had more experience with managed care during their working years. Our prior analysis found that, in 2011, nearly one in four people enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans during their first year on Medicare.3 This brief examines whether the rate has increased with more boomers aging onto Medicare, and whether these coverage decisions vary by geographic area and select characteristics. The analysis is based on a five percent sample of claims from 2010 to 2016.

Enrollment Rates

In 2016, Less than one-third (29 percent) of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans during their first year on Medicare, slightly more than the 23 percent observed in 2011, but far from a majority (Figure 1). Most new beneficiaries (71 percent) were covered under traditional Medicare for their first year on Medicare.

Enrollment Rates, By Year

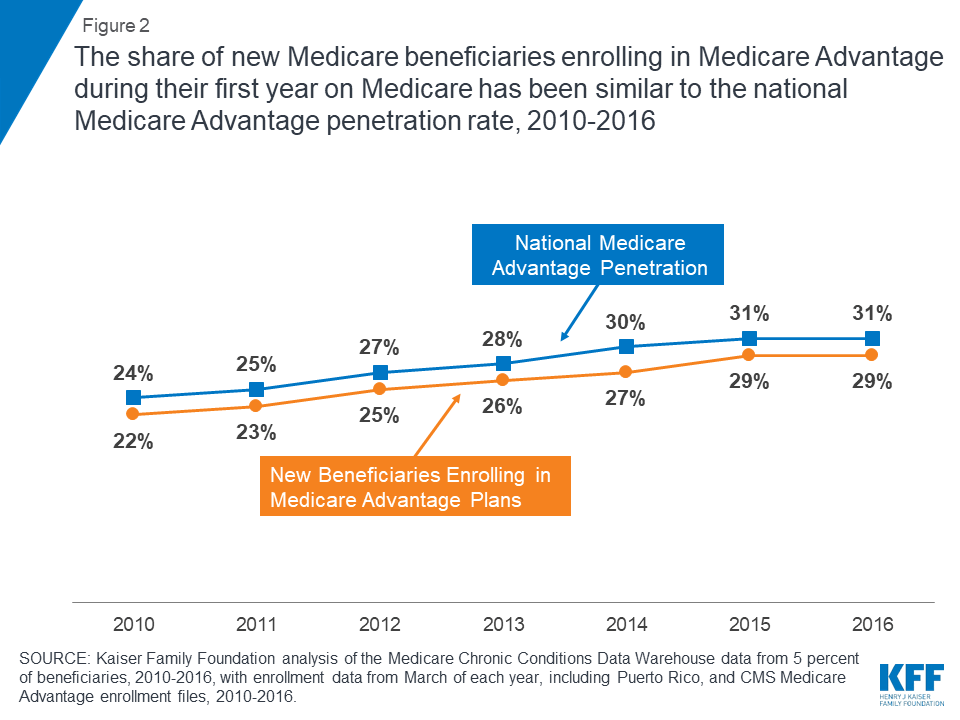

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage by new beneficiaries has tracked closely with the national Medicare Advantage penetration rate (Figure 2). In 2010, about 22 percent of new Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, while that same year, a similar percentage of all Medicare beneficiaries (24 percent) enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans. More recently, in 2016, less than one-third of new Medicare beneficiaries (29 percent) enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, which is similar to the national Medicare Advantage penetration rate among all Medicare beneficiaries that year (31 percent).

Enrollment Rates, By State

The share of new beneficiaries enrolling in Medicare Advantage plans during their first year on Medicare varies greatly across the country (Figure 3). In two states (Oregon and Minnesota) and Puerto Rico, more than 40 percent of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2016. However in five states (Delaware, Maryland, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and Vermont) and the District of Columbia, less than 11 percent of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, while the vast majority were instead choosing traditional Medicare when they first enrolled in Medicare.

Enrollment Rates Across Counties

The share of new beneficiaries that enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans also varied across counties. In counties as diverse as Atlantic, NJ (Atlantic City), Baltimore City, MD, Monterey, CA, and Shawnee, KS (Topeka), less than 11 percent of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans in 2016. In contrast, in counties such as Monroe, NY (Rochester), Miami-Dade, FL (Miami), Allegheny, PA (Pittsburgh), and Multnomah, OR (Portland), more than half of new beneficiaries enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan during their first year on Medicare. Additionally, these large differences in Medicare Advantage enrollment among new beneficiaries may help explain why some believe most new beneficiaries are enrolling in Medicare Advantage, which is the case in a minority of counties.

Enrollment Rates, By Medicare Advantage Penetration in the County

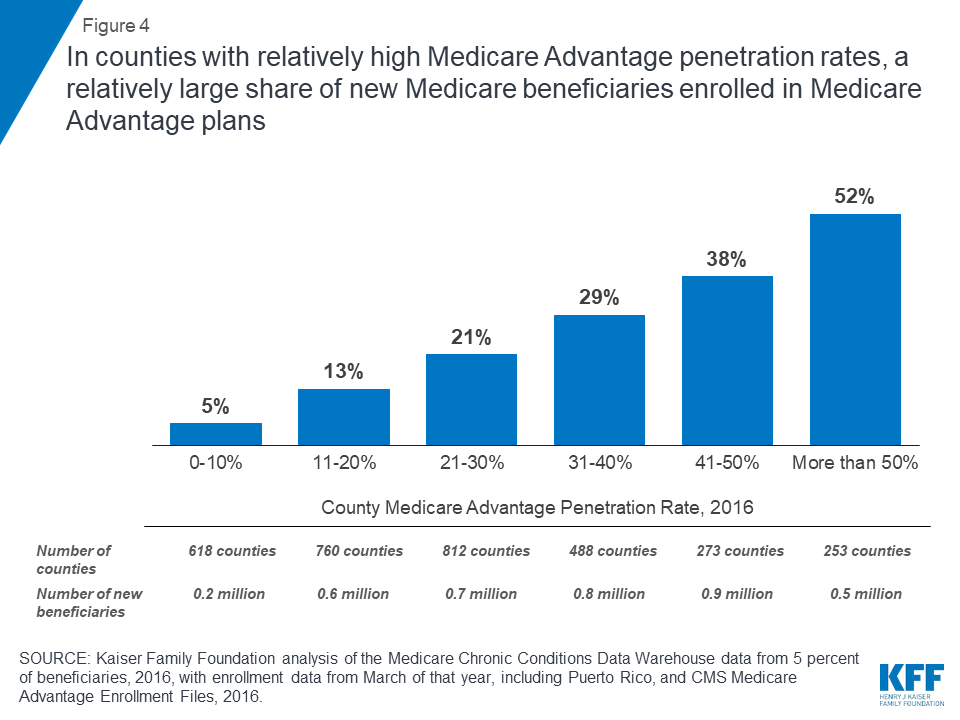

On average, the share of new beneficiaries enrolling in Medicare Advantage plans is higher in counties with higher Medicare Advantage penetration rates (Figure 4). In counties where more than half of all beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, 52 percent of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, on average, in 2016. In contrast, in counties where 10 percent or fewer beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, only 5 percent of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, on average.

Enrollment rates, By Number Of Medicare Beneficiaries In The County

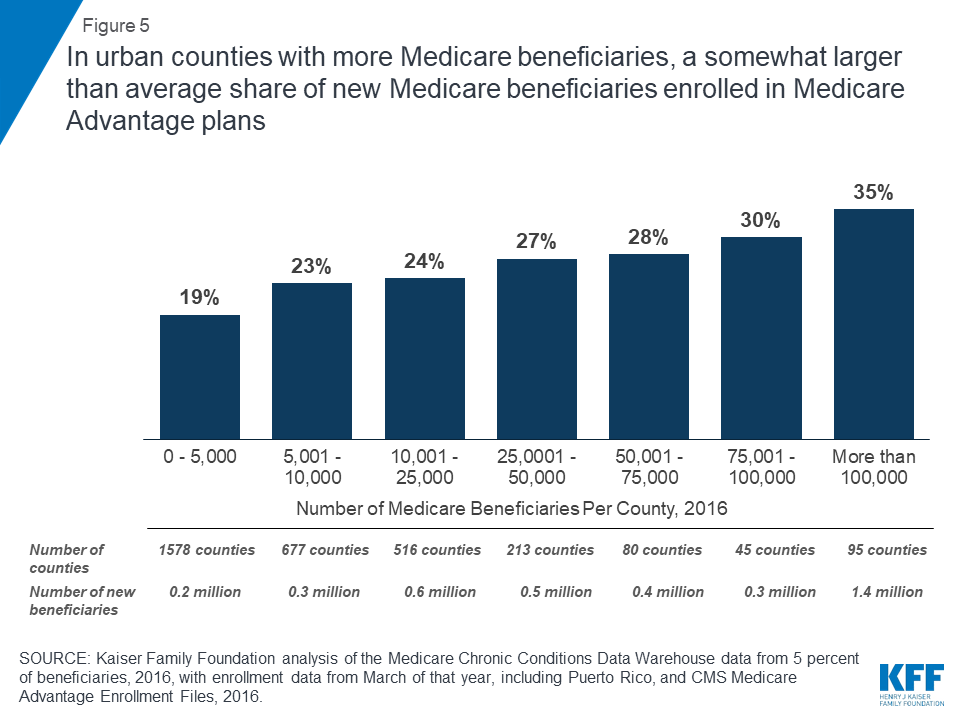

New beneficiaries enroll in Medicare Advantage plans at higher rates in areas with more Medicare beneficiaries (Figure 5). In counties with more than 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, about one-third (35 percent) of new Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, on average, in 2016. In smaller counties with 5,000 or fewer beneficiaries, about one-fifth (19 percent) of new beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, on average.

Enrollment Rates Across Select Characteristics

enrollment rates, BY AGE

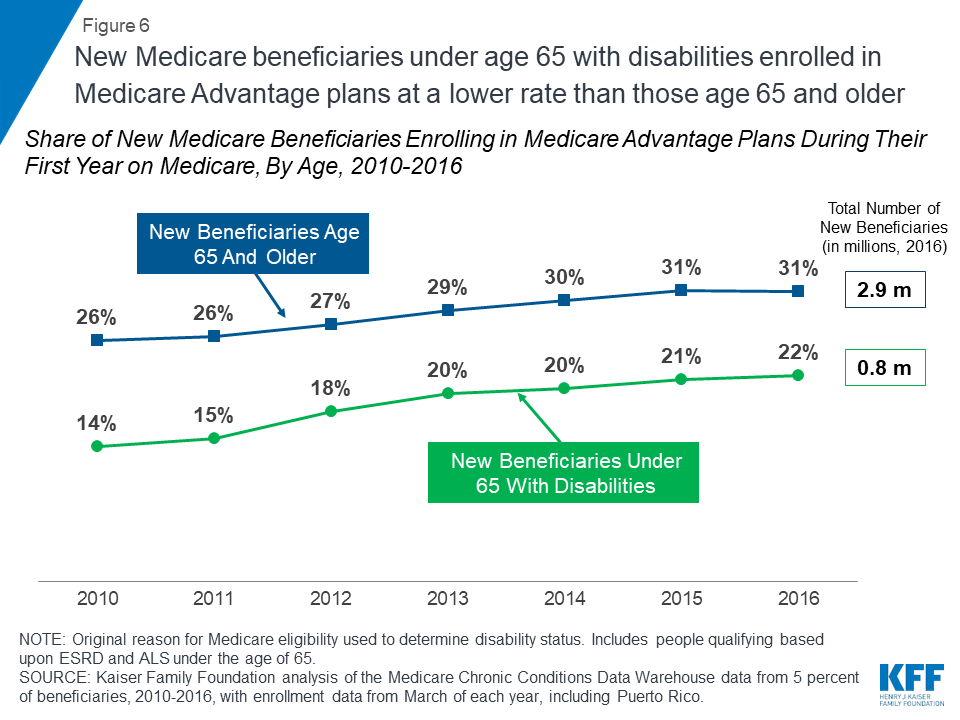

People under the age of 65 who became eligible for Medicare because of a serious disability enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans at consistently lower rates than new beneficiaries who qualified for Medicare because they were age 65 or older (22 versus 31 percent, respectively, in 2016; Figure 6). It is not clear why younger beneficiaries with serious disabilities enroll in Medicare Advantage plans at lower rates than people ages 65 and older, but these findings warrant further attention.

Enrollment rates, By Medicare-Medicaid Status

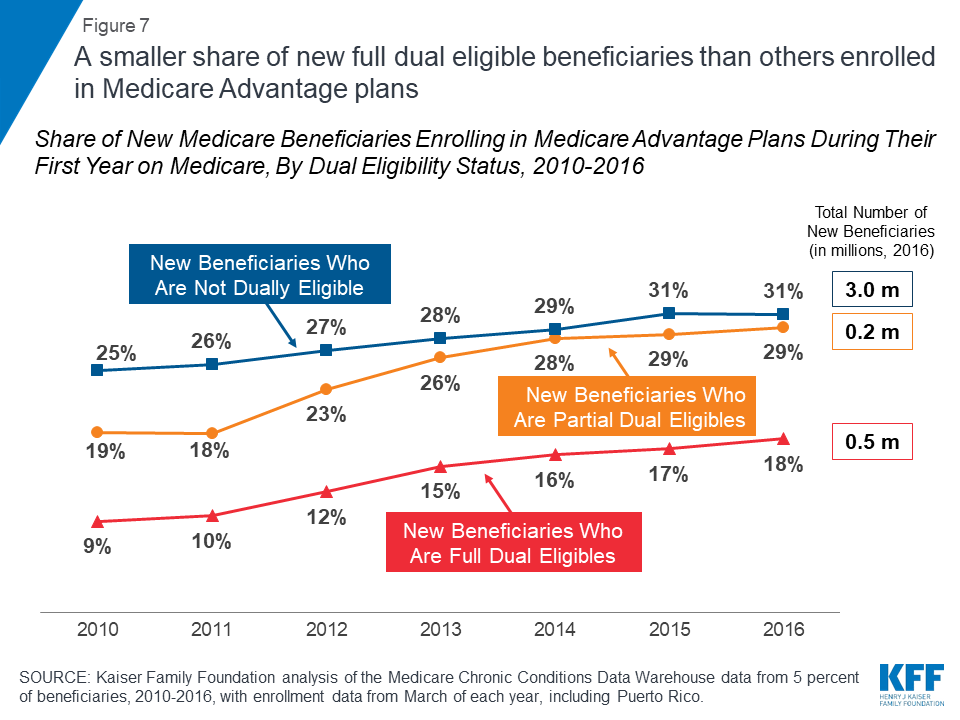

The Medicare Advantage enrollment rate among new beneficiaries who received full Medicaid benefits (“full dual eligibles”) was lower than among new beneficiaries not eligible for Medicaid in 2016 (18 percent versus 31 percent, respectively, Figure 7). New beneficiaries who receive partial Medicaid benefits (“partial dual eligibles”) opted into Medicare Advantage during their first year on Medicare at about the same rate as those who were not eligible for Medicaid. It is unclear why full dual eligibles are opting into Medicare Advantage plans at lower rates than others; it may be because they have significant health needs and are reluctant to join a plan with a limited provider network. Those who are less healthy may also be less attracted to plans’ extra benefits, such as gym memberships, and full dual eligibles may be less drawn to plans’ out-of-pocket limits if Medicaid is covering their cost-sharing requirements.

Discussion

Less than one-third (29 percent) of new Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans during their first year on Medicare, a rate slightly lower than the national Medicare Advantage penetration rate in 2016. While the Congressional Budget Office is projecting a steady increase in Medicare Advantage enrollment, rising to 47 percent by 2029, even with an aging Baby Boom Generation, the majority of new beneficiaries are opting for traditional Medicare in the year they first go on Medicare. The relatively low enrollment rates among new beneficiaries with high needs may warrant further scrutiny. While Medicare Advantage enrollment among new beneficiaries is rising, these findings suggest that ongoing attention to traditional Medicare is needed to meet the needs of the lion’s share of the Medicare population.

Gretchen Jacobson, Tricia Neuman, and Meredith Freed are with KFF.Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.

| Data and Methods The brief uses claims data from a five percent sample of Medicare beneficiaries from the Master Beneficiary Summary Files of Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for 2010 through 2016. The data was used in conjunction with the Medicare Advantage landscape file and enrollment file for each year. The analysis includes new beneficiaries residing in areas where no Medicare Advantage plans were available for individual enrollment, totaling about 30,000 new beneficiaries in 2016. The analysis was unable to exclude beneficiaries with retiree health coverage, who would likely use whichever coverage option, Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare, their former employer or union would fund. The analysis included new beneficiaries who were automatically enrolled into Medicare-Medicaid demonstration plans in the denominator of Medicare Advantage enrollees because they did not make a voluntary choice. |

Endnotes

- Kaiser Family Foundation, “How are Seniors Choosing and Changing Health Insurance Plans?” May 13, 2014. https://modern.kff.org/medicare/report/how-are-seniors-choosing-and-changing-health-insurance-plans/ ↩︎

- Neuman, Patricia and Gretchen A. Jacobson. Medicare Advantage Checkup. New England Journal of Medicine. November 2018. Issue 379, page 2163-2172. ↩︎

- Jacobson, Gretchen A., Patricia Neuman, and Anthony Damico. At Least Half of New Medicare Advantage Enrollees Had Switched From Traditional Medicare During 2006-11. Health Affairs. January 2015. Volume 34, Issue 1. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0218 ↩︎