The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Key Findings

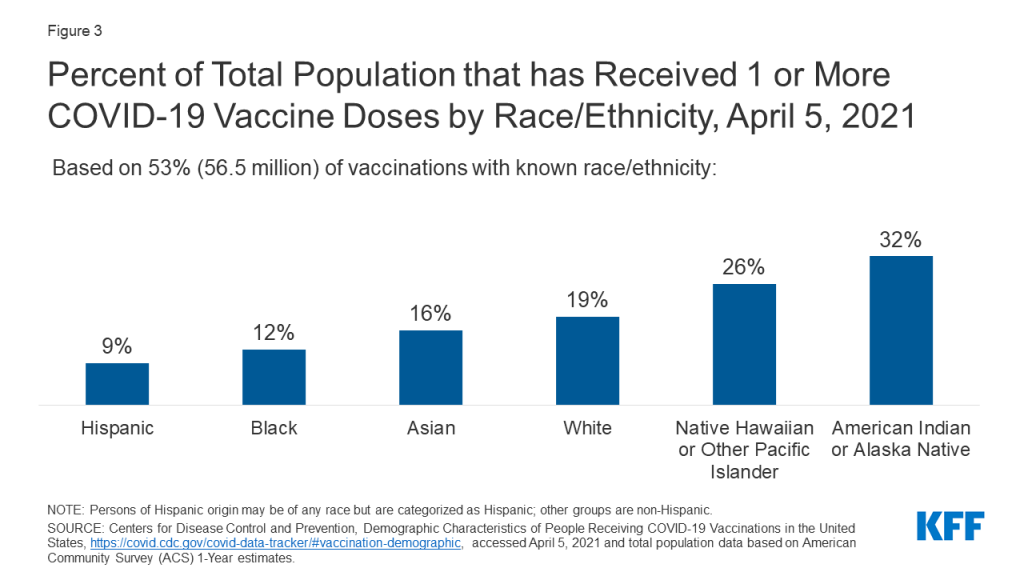

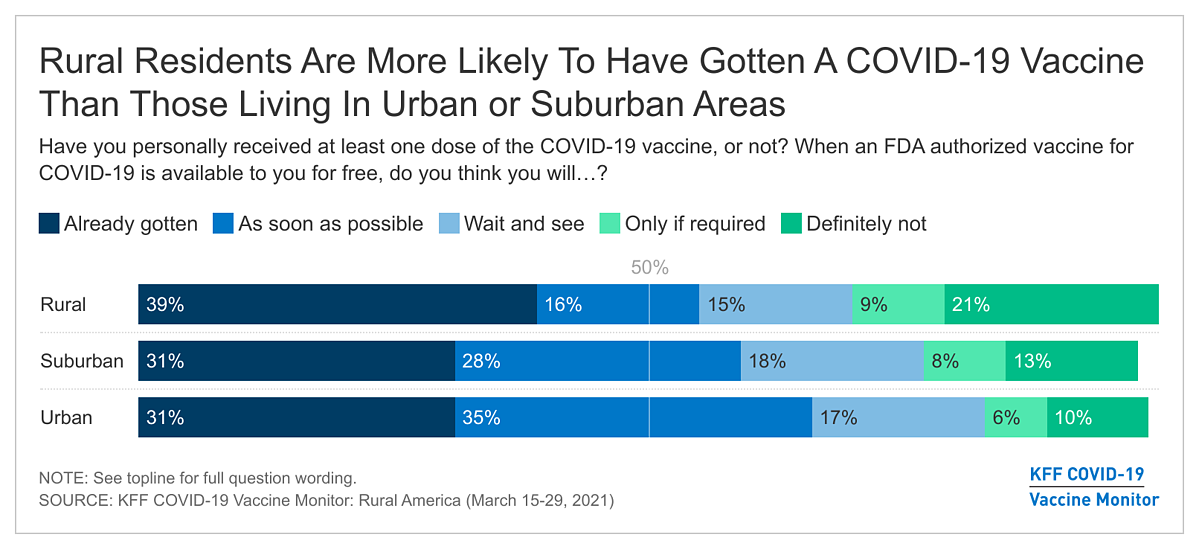

- The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor took a deep dive into how the coronavirus pandemic has impacted rural communities in the U.S. including an analysis of the vaccine intentions of rural residents. Based on interviews of 1,001 adults living in rural America, the Monitor finds four in ten (39%) saying they have already gotten at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, larger than the shares of adults living in urban or suburban areas who say the same (31% each). The Monitor results suggest there are many reasons why rural communities may so far be outpacing suburban and urban areas in vaccination rates, including the fact that rural residents are more likely than urban and suburban residents to say their community has enough vaccination locations and vaccine supply.

- While rural residents have outpaced suburban and urban residents in early self-reported uptake of COVID-19 vaccines, fewer rural residents compared to urban and suburban residents say they are planning or considering getting vaccinated. Three in ten rural residents say they will get vaccinated as soon as possible (16%) or are waiting to see how it is working for other people (15%), compared to about half of urban and suburban residents who say the same. Three in ten rural residents say they will either “definitely not” get vaccinated or will only do so if required, and few unvaccinated rural residents (11%) say they have tried to get an appointment. These results suggest that vaccination uptake in rural America may start lagging behind urban and suburban areas. The groups within rural communities that are the least likely to report either already receiving a vaccine or planning to do so as soon as possible are Republicans, White Evangelicals, essential workers in fields other than health care, and young adults 18-49. About three in ten in each of these groups report they will “definitely not” receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

- More than half of Black rural adults (64%) say they have either received a vaccine or will do so as soon as they can, but this population also disproportionately reports difficulty accessing COVID-19 vaccine resources. Less than half of Black adults say their rural communities have enough supply of COVID-19 vaccine (compared to 59% of White rural adults) and half (53%) say their community has enough vaccination locations (compared to 69% of White adults). Access to COVID-19 vaccines within the Black community is consistent with other forms of health care access in rural communities with Black residents also less likely than White residents to say their community has enough hospitals and doctors and health care providers.

- While the concerns about the vaccine for those living in rural areas are similar to urban and suburban areas, there are a variety of other attitudes towards the pandemic overall that may help explain why a larger share of rural residents say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated. About six in ten rural residents (compared to less than half of urban and suburban residents) say getting vaccinated against COVID-19 is a personal choice. Rural residents are also less likely to say they are worried about themselves or their family members getting sick from coronavirus or that they wear a mask most of the time when they leave their house.

COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions In Rural America

About four in ten U.S. adults living in rural areas say they have already received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (27% say they have received a full course either receiving both doses of a two-dose vaccine or a one-dose vaccine). The share of rural residents who have been vaccinated is up sixteen percentage points from February 2021 as many states increase their vaccine rollout to larger shares of the population, with an additional 16% of rural residents saying they will get the vaccine as soon as they can. At the same, nearly half of rural residents say they are either taking a “wait and see” approach (15%), they will get the vaccine only if they are required to do so for work, school, or other activities (9%), or that they will “definitely not” get the vaccine (21%), similar to the shares who have given those responses since January.

While a larger share of rural residents say they have already received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine than urban and suburban residents (31%, each), fewer rural residents compared to urban and suburban residents say they will get it as soon as possible (16% compared to 35% and 28%). This suggest that vaccine uptake in rural communities is currently outpacing urban and suburban areas but may begin lagging behind more populated areas as they experience increased access. Two-thirds of those living in urban areas say they have either already received a vaccine or will get it as soon as possible as do six in ten (59%) of those living in suburban areas.

Vaccine uptake does not differ within rural communities of varying size or regions of the U.S. Fifty-six percent of those living in less populated rural areas report receiving a vaccine or intending to get it as soon as they can, as do 52% of those living in more populated rural areas. In addition, similar shares of rural residents living in the Midwest, South, and West say they have already been vaccinated or will as soon as possible (50%, 57%, 56%).

Looking across various demographics within rural communities, the groups most likely to say they’ve either already gotten the vaccine or will get it as soon as possible are Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%), adults ages 65 and over (79%), and college graduates (67%). About three in ten Republicans (32%), essential workers in field other than health care (29%), and adults under the age of 50 (28%) say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine.

Understanding Who Is “Wait and See” And Who Is “Definitely Not” Getting the VACCINE In rural America

Twenty percent of U.S. adults live in rural America and this significant segment of the population reflect a very diverse community across race and ethnicity, educational levels, employment, partisanship and many other factors. In addition to understanding the vaccine intentions among certain demographic groups, it is also important to understand the demographics of the varying vaccine intention groups. Large shares of those who say they will “definitely not” receive a COVID-19 vaccine self-identify as White Evangelicals (41%) and Republicans or Republican leaning independents (73%). More than eight in ten in this group (85%) also say they do not normally get a flu vaccine.

Access To COVID-19 Vaccines In Rural Communities

Despite the fact that about half of rural residents who have not yet been vaccinated believe they are currently eligible to receive a vaccine, few (11%) say they have tried to get an appointment, which is half the share of those living in urban (21%) and suburban (22%) areas. A majority of rural residents who have tried to get an appointment say they were able to get one. Among those who say they were unable to get an appointment for a vaccine, the most common reason why was that they did not meet their area’s eligibility requirements, followed by a smaller portion who reported there weren’t any appointments available.

A majority of rural adults think their community has enough hospitals (73%), doctors and health care workers (70%) to serve local residents as well as enough COVID-19 vaccination locations (68%) and supply of the COVID-19 vaccine (58%) for local residents. Perception of availability of COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination locations does not vary within types of rural communities. Adults who live in more populated rural areas, on the whole, are no more or less likely to report enough access to the services listed than those who live in less populated rural areas.

Consistent with the higher reported vaccination rates among rural residents, the Monitor finds that rural residents are more likely to say their community has enough supply of the COVID-19 vaccine to serve local residents than urban or suburban community members (46% each). In addition, 68% of adults in rural areas report having enough vaccination locations, compared to smaller shares of urban (52%) and suburban (55%) adults.

Eight in ten suburban adults report having enough hospitals to serve their community than either urban or rural residents (compared to 76% urban and 73% rural), which is similar to the share who say the same about the number of doctors and health care providers. Less than half of urban, suburban, and rural residents say their community has enough mental health providers.

Among those living in rural areas, Black adults are less likely than White and Hispanic adults to feel their community has enough health care providers and vaccination access to serve the local population. Slightly less than half of Black rural adults say their community has enough supply of the COVID-19 vaccine, while 59% of White rural adults and 52% of Hispanic rural adults say the same. In addition, while about two-thirds of Hispanic and White rural adults say their community has enough vaccination locations, about half of Black rural adults think so. Black residents in rural communities are also less likely than White and Hispanic residents to say their community has enough hospitals, and doctors and health care providers.

In addition to perceived access to COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination locations within their communities, larger shares of rural residents (59%) say they think vaccines in the U.S. are being distributed fairly to people across urban, suburban, and rural areas compared to urban (43%) and suburban residents (50%).

This is despite the fact that majorities of rural residents, including 50% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, and 66% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, say the federal government does more to help people living in and around large cities than to help people living in rural areas.

Rural Residents Report Minimal Travel Burdens To Get A COVID-19 Vaccine, Black Residents Report Longer Travel Times

Around half of adults in all rural areas (49%) who have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine report it took them less than 15 minutes to travel to the place where they got the vaccine, which is similar to the share of urban residents (47%) and suburban residents (42%) who say the same.

About one-fourth of rural residents traveling to get a COVID-19 vaccine say it took them 30 minutes or longer to travel to the place to get vaccinated, however 14% of those living in more populated rural areas say it took them an hour or longer.

Rural adults who haven’t received their vaccine yet estimate that it will take them a little longer to travel to the nearest COVID-19 vaccination site in their area than those in urban and rural environments. About seven in ten rural adults in less populated areas think it will take them under 30 minutes to travel to their closest vaccination site, while fewer rural adults in more populated areas (68%) think it will take them under 30 minutes. At least six in ten urban (69%), suburban (63%), and rural (71%) residents estimate it will take them under 30 minutes in transit time.

Factors In Rural Residents’ Decisions To Get Vaccinated

Rural residents express a variety of attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic overall that differ somewhat from their urban and suburban counterparts and may explain their different level of willingness to get vaccinated. For example, several findings suggest that rural residents are less likely to view the pandemic as a serious threat either to the country or their families. More than four in ten rural residents (44%) say they think the news has “generally exaggerated” the seriousness of coronavirus, while one-third say the news has gotten it “generally correct” and one-fifth say it has been “generally underestimated.” A larger share of rural residents say it has been exaggerated compared to urban (27%) and suburban (33%) residents. Rural residents (40%) are also less likely to say they are worried about themselves or their family members getting sick from coronavirus compared to urban (54%) and suburban residents (49%). In addition, while majorities of rural residents report wearing a face mask to protect themselves and others at least most of the time when they leave their house (74%), it is a smaller share compared to urban (90%) and suburban (87%) residents.

Views of the coronavirus pandemic and willingness to wear a protective mask are also strongly connected to rural resident’s decisions to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. More than half rural residents who think the seriousness of the pandemic has been either generally correct or underestimated say they have already received a COVID-19 vaccine, compared to one in five (20%) of those who think the seriousness has been generally exaggerated. In addition, nearly half of rural adults who only wear a mask “some of the time” or “never” say they will definitely not get vaccinated.

Concerns Among Those Who Have not Yet Been Vaccinated

When asked to say in their own words the main reason why they don’t want to get vaccinated, rural residents in the “definitely not” group cite a range of concerns. The most frequently mentioned reason is feeling that the vaccines are too new or that there is not enough information about the long-term effects (mentioned by 19%). About one in ten cite general distrust of the vaccine (12%), dislike of vaccines in general (9%), don’t believe the vaccine is effective against COVID-19 (8%), or report that they either generally don’t need it (3%) or don’t need it because they already had COVID-19 (5%).

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: What is the MAIN reason why you don’t want to get the COVID-19 vaccine? (among rural adults who say they will “definitely not” get it)

“Pretty good immune system don’t want to mess with it.” – 55 year-old man

“I have allergies to flu shots. They make me very ill. I’m nervous about it.” – 50 year-old woman

“l don’t just want to get it, don’t see the point in getting it. Lot of negative reaction I rather not.” – 37 year-old woman

“99.9 survival.” – 71 year-old man

“I have already had the coronavirus and I am currently of the belief that it has more side effects than the government wants to admit to.” – 54 year-old man

“Because who knows of the effects or what the vaccine truly is.” – 41 year-old woman

“I honestly don’t think it will work full force and there will just be more COVID and different shots and I honestly think this is government made.” – 36 year-old woman

“I’ve never gotten a COVID or flu vaccine before.” – 31 year-old man

“It is not a vaccine, it is just a flu shot that has not been tested. It only makes the COVID flu, if you get it, easier for your body to resolve. A vaccine means you will not ever contract the virus you are vaccinated against.” – 77 year-old man

“I am a healthy young person. I will save it for someone else.” – 29 year-old woman

“Uh, because I have other health issues that weakened my immune system.” – 48 year-old man

“I’m scared. I just feel like if it is meant for me to catch it I will catch it.” – 34 year-old woman

“COVID virus has a 99% recovery rate.” – 42 year-old woman

“It’s a trial. Don’t know long term effects.” – 28 year-old woman

Six in ten rural residents (compared to four in ten urban residents and 47% suburban residents) say getting vaccinated against COVID-19 is a personal choice. This is a much larger share than the share of rural residents who say getting vaccinated is part of everyone’s responsibility to protect the health of others (42% of rural residents compared to 52% of suburban, 59% of urban).

Because a majority of rural residents think getting vaccinated is a personal choice, one of the top concerns among the 45% of rural residents who are not yet convinced to get the vaccine right away (defined as those who say they will “wait and see” before getting vaccinated, will get the vaccine “only if required” or will “definitely not” get it) is that they might be required to get a COVID-19 vaccine even if they don’t want to (66%). This is a top concern among both those who want say they definitely won’t be getting a vaccine as well as among those who want to “wait and see”. Other top concerns include possible serious side effects from the vaccine (64%) or the effects of the vaccine will be worse than getting COVID-19 (53%). Notably few rural residents cite inability to get the vaccine from a place they trust or difficulty traveling to a vaccination site as concerns (15% and 9%, respectively).

Among those who are not convinced to get vaccinated right away, seven in ten Republicans in rural areas (71%) say they are concerned that they might be required to get the vaccine even if they don’t want to.

A growing share of the overall population now say they have enough information about when and where they will be able to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Three-quarters of rural residents who are not yet vaccinated now say they have enough information about where they will be able to get a COVID-19 vaccine, up from 61% in February, and 66% have enough information about when they will be able to get vaccinated, up from 38% last month. Rural residents are more likely to say they have enough information about when they’ll be able to get vaccinated than both urban and suburban residents, with smaller differences on the question of where.

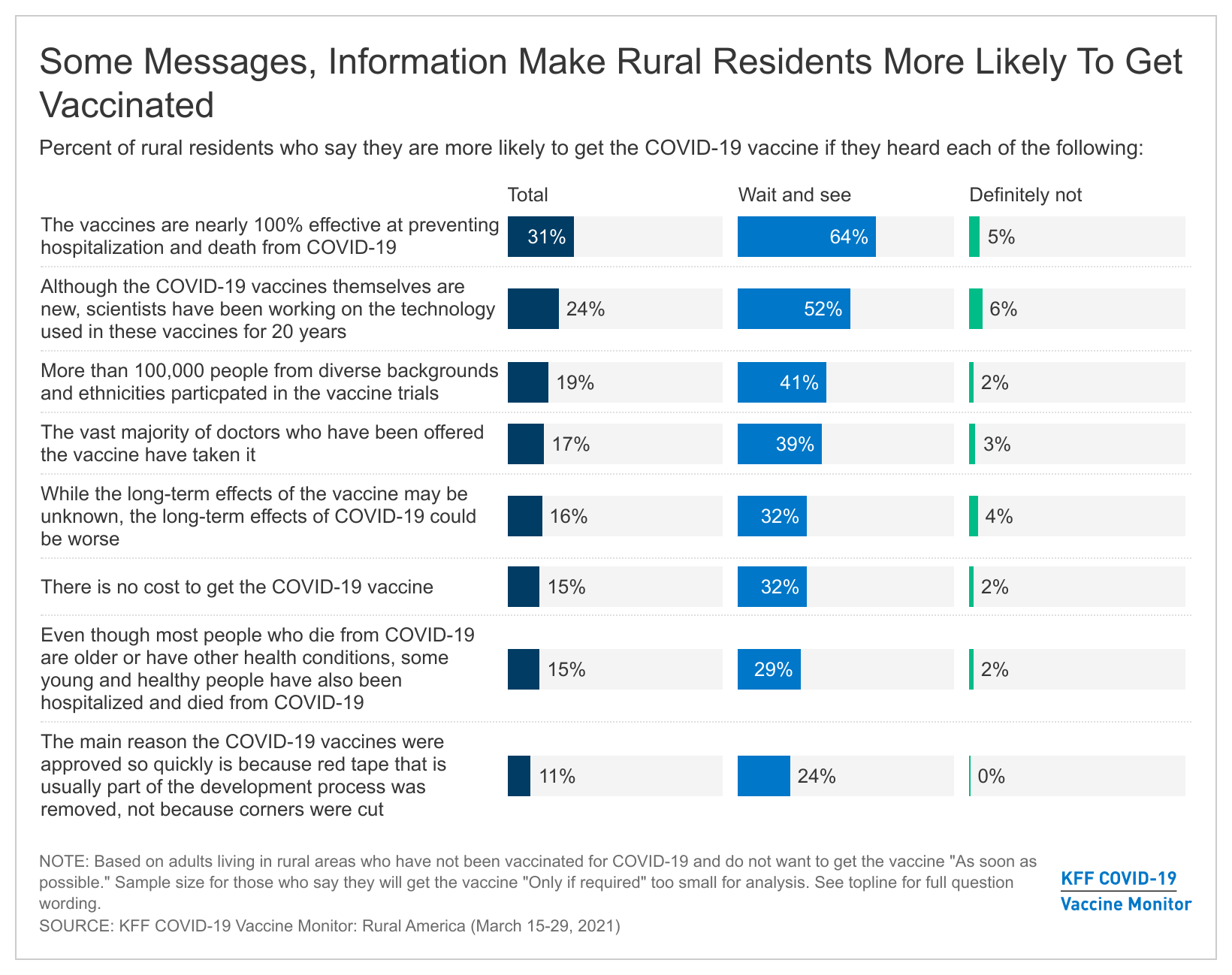

The latest COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor tested a variety of potential incentives, messages, and pieces of information that might be used to increase vaccination uptake. Similar to the general public, within the rural community there are various incentives and messages that may help convince people in the “wait and see” and “only if required” groups to get vaccinated, but very few of them move people in the “definitely not” group. For example, more than half of those in the “wait and see” group say hearing that the vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing hospitalization and death from COVID-19 (64%) or that hearing that scientists have been working on the technology used in the new COVID-19 vaccines or 20 years (52%) will make them more likely to get vaccinated. Across the board, no message or piece of information were effective at moving those who say they will definitely not get vaccinated, with the share of that group saying they’d be more convinced after hearing each message in the single digits.

Among rural residents who are not yet convinced to get the COVID-19 vaccine right away, few (14%) say they would be more likely to get vaccinated if President Trump came out with a message strongly urging people to do so. One in four rural residents in the “wait and see” group say this type of messaging could make them more likely to get a vaccine.