Access and Coverage for Mental Health Care: Findings from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey

Issue Brief

Key Takeaways

- A significantly higher share of women (50%) than men (35%) thought they needed mental health services in the past two years. Among those who thought they needed mental health care, about six in ten women and men sought care in the past two years.

- Nearly two-thirds of young women ages 18-25 report needing mental health care in the past two years compared to one-third of women ages 50-64.

- Among all women ages 18-64 who thought they needed mental health services in the past two years, just half tried and were able to get an appointment for mental health care, 10% tried but were unable to get an appointment, and 40% did not seek care.

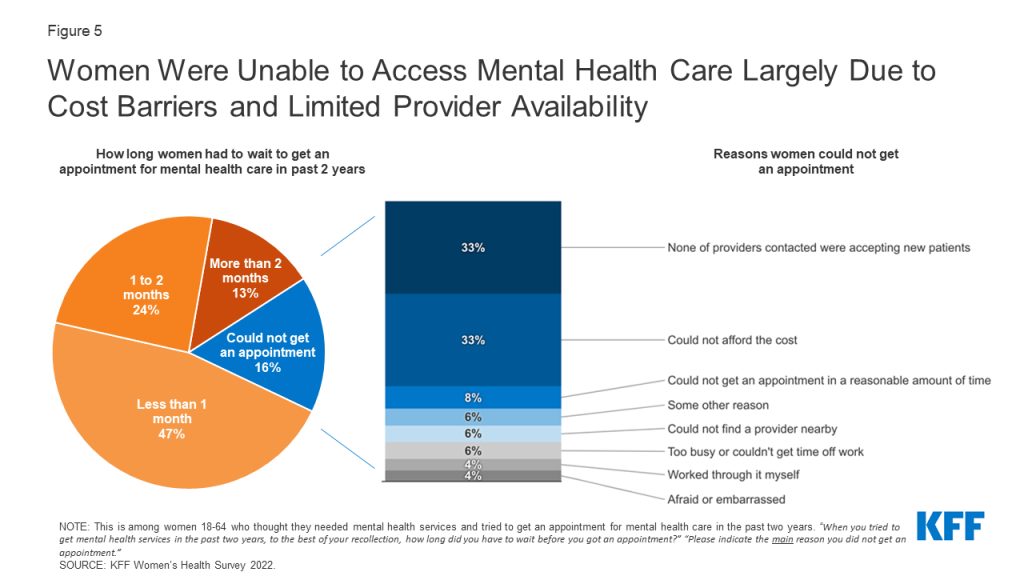

- Almost half of women who needed mental health services and tried to get care were able to get an appointment within a month, but more than one-third of women had to wait more than a month. Among those who could not get an appointment, women cite limited provider availability and cost as the main reasons they were unable to access mental health care.

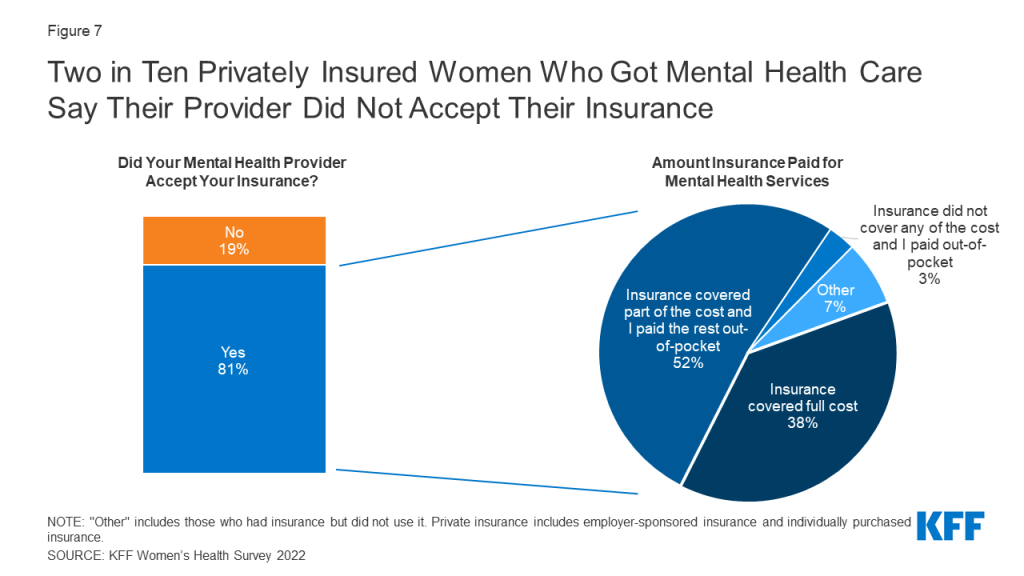

- Two in ten privately insured women with a mental health appointment in the past two years say their provider did not accept their insurance.

- Sixty percent of women had a telemedicine/telehealth visit in the past two years. Mental health care was the third most common reason women cited for accessing telehealth/telemedicine services, with 17% saying it was the primary purpose of their most recent telemedicine visit. The majority report that the quality of their telehealth visit was the same as an in-person visit.

Introduction

Mental health has emerged as a rapidly growing concern in recent years, with 90% of Americans saying there is a mental health crisis in a recent KFF-CNN poll. Women experience several mental health conditions more commonly than men, and some also experience mental health disorders that are unique to women, such as perinatal depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorders that may occur when hormone levels change. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics show that across all age groups, women were almost twice as likely to have depression and anxiety than men. The COVID-19 pandemic, the opioid epidemic, and racism are among commonly cited stressors that have exacerbated long-standing mental health issues and prompted growing demand for mental health services in the past two years, particularly among women.

This brief provides new data from the 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey (WHS), a nationally representative survey of 5,145 women and 1,225 men ages 18-64 conducted primarily online from May 10, 2022, to June 7, 2022. In addition to several topics related to reproductive health and well-being, the survey asked respondents about their experiences accessing mental health services in the past two years. This issue brief presents KFF WHS data on mental health services access among self-identified women and men ages 18-64, and it also takes a closer look at mental health coverage among women. People of all genders, including non-binary people, were asked these questions; however, there are insufficient data to report on non-cisgendered people. See the Methodology section for details.

Utilization of Mental Health Services

Gender Differences

Half of women ages 18-64 (50%) thought they needed mental health services in the past two years (Figure 1) and a significantly smaller share of men report they needed mental health care (35%). Studies have long documented gender disparities in the rates and types of mental health conditions. Among those who thought they needed care, however, similar rates of women and men report seeking care. Sixty percent of women tried to make an appointment for mental health compared to 56% of men.

Need and Care Seeking

Nearly two thirds (64%) of women ages 18-25 thought they needed mental health services at some point in the past two years compared to just 35% of women ages 50-64 (Figure 2). Previous findings from the 2020 KFF WHS revealed that more than half of women (51%) said that worry or stress related to the coronavirus had affected their mental health. Other studies show that young adults, particularly women, experienced high incidence of depression and loneliness during the early stages of the pandemic.

More than half of women with low incomes (< 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL)) (55%) and women with Medicaid coverage (58%) thought they needed mental health care in the past two years compared to less than half (47%) of women with higher incomes (≥ 200% FPL) and those with private insurance (includes employer-sponsored insurance and individually purchased insurance) (47%). The FPL in 2022 for an individual is $13,590 (Figure 2).

Among those who thought they needed mental health care, larger shares of women ages 26-35 (63%) and women ages 36-49 (64%) sought care compared to 55% of women ages 50-64. Larger shares of women enrolled in Medicaid (67%) sought mental health services compared to women who have private insurance (58%) and women who are uninsured (50%) (Figure 3).

A significantly lower share of Asian/Pacific Islander women (40%) say they needed mental health services at some point in the past two years than their White counterparts (50%). Although not statistically significant, smaller shares of Asian/Pacific Islander women report seeking care compared to White women (50% vs. 62%). While the pandemic fueled violence against Asians and subsequently worsened anxiety and mental health for many, studies have shown that Asians reported greater cultural barriers to help-seeking such as family stigma and concerns about “losing face.” Cultural barriers may influence perceived need of care in addition to help-seeking behaviors.

Although the self-reported need for mental health care did not differ between Hispanic and White women (both 50%), smaller shares of Hispanic women (56%) sought care compared to White women (62%). Despite high rates of depression among Hispanic women, studies have shown that stigma and perceived discrimination in health care settings can contribute to underutilization of mental health services within Hispanic communities. Hispanic women also have the highest uninsured rate, which may limit their access to care.

Among the 50% of women who thought they needed mental health services, half (50%) were able to get an appointment, while another 40% did not try to get mental health services (Figure 4). One in ten (10%) who tried to get care were unable to make an appointment for mental health services. This suggests that the other half of women who report needing care may have unmet mental health needs.

Among all women who thought they needed mental health care and tried to get it in the past two years, nearly half (47%) had to wait less than a month for an appointment (Figure 5). One-quarter (24%) had to wait one to two months, and 13% had to wait more than two months to get care. The remaining 16% of those who sought mental health care could not get an appointment.

Among the 16% of women who needed care, sought care, and were unable to get an appointment for mental health services, the main reasons were limited provider availability and cost barriers. One-third of women who could not get an appointment say the main reasons were that they could not find a provider that was accepting new patients (33%) or that they could not afford the cost of mental health services (33%). Eight percent could not get an appointment in a reasonable amount of time and six percent say they could not find a provider nearby. Another 6% say they could not get an appointment for another reason, such as not wanting to go in-person due to COVID-19.

Our findings on provider availability are consistent with other studies on mental health access. A report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that many consumers with health insurance faced challenges finding in-network care. The country also faces a workforce shortage of behavioral health professionals in addition to other challenges with health care infrastructure that exacerbates issues with accessibility.

Cost and Coverage for Mental Health Services

Among those who sought care but could not get an appointment, one-third (33%) say the main reason was that they could not afford it (Figure 5). Cost remains a barrier to mental health care access for some people with insurance and especially for those who lack coverage. Significantly larger shares of women who are uninsured (60%) say they could not get an appointment due to affordability reasons, compared to those who have health insurance either through private plans (33%) or Medicaid (30%) (Figure 6). There were no significant differences between women who have private insurance and women covered by Medicaid.

These findings on cost barriers are consistent with current literature, which has found that along with provider availability, affordability is one of the most prevalent barriers to mental health care.

While federal laws require special insurance protections such as parity for mental health care, gaps in coverage remain. All state Medicaid programs provide coverage for mental health services, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires most private insurers to cover mental health care. However, the scope of coverage varies, provider networks are limited in many plans, and mental health providers may not accept all insurance plans. Some mental health practitioners do not accept insurance of any kind.

While most privately insured women who received mental health services in the past two years say their provider accepted their insurance for their most recent mental health visit (81%), two in ten (19%) say their provider did not. Among privately insured women who said their provider accepted their insurance, more than half report having out-of-pocket expenses for their most recent mental health visit. More than one-third (36%) say their insurance covered the full cost and 52% say their insurance covered some of the cost. Three percent say their insurance did not cover any of the cost. (Figure 7).

The Affordable Care Act requires that enrollees in most private health insurance plans have the right to appeal denied claims, though some evidence suggests that many are unfamiliar with appeals processes or are unaware of this protection. Among privately insured women whose insurance was not accepted by their mental health provider, 27% filed a claim with the health insurance plan to try to get reimbursed for some or all the cost (data not shown).

Telehealth

Social distancing during the pandemic contributed to a sharp increase in the provision of telehealth services, widening the access of counseling, therapy, prescribing, and other services via remote methods such as video and telephone. The rapid expansion of telemedicine/telehealth over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic has broadened access to health care for many, including access to mental health services. Mental health services provided via telehealth include speaking to a mental health provider over telephone or video, or through online apps such as Talkspace.

Sixty percent of women ages 18-64 had a telemedicine/telehealth visit in the past two years. Among these women, 17% say the primary purpose of their most recent visit was for mental health services (Figure 8). Accessing mental health care services was the third most common reason for telehealth visits, following annual check-ups (18%) and visits for minor illness or injury (18%). Three in ten women ages 18-25 (29%) say their most recent telehealth visit was for mental health services compared to 20% of women ages 26 to 35, 18% of women ages 36 to 49, and 10% of women ages 50 to 64 and older. A larger share of White women (21%) obtained mental health services at their most recent telehealth visit than Black women (13%), Hispanic women (14%), and Asian/Pacific Islander women (7%).

A larger share of women with Medicaid coverage (22%) report that their most recent telemedicine or telehealth visit was for mental health services than women who are privately insured (15%).

A similar share of women living in rural (23%) and urban/suburban (17%) areas report that the primary purpose of their most recent telehealth or telemedicine visit was for mental health services.

The majority (69%) of women who had a telehealth or telemedicine visit in the past two years for mental health care say the quality of care they received at their most recent visit was the same as an in-person visit for this type of care (Figure 9). One-in-five (19%) report receiving better quality of care during their telehealth visit, while 12% report experiencing worse quality than an in-person visit. These findings suggest the quality of mental health care is typically not diminished when accessing care via telehealth.

Conclusion

The demand for mental health care continues to surge as wait lists for professional help grow. Recent reports reveal that mental health providers across the nation are facing an overwhelming demand for services, leaving many individuals without care. Our survey finds that among the half of women who report that they thought they needed mental health services in the past two years, only half got an appointment for care. Unmet mental health needs are known to affect the overall well-being and productivity of individuals, families, and society, and studies have consistently shown that women are disproportionately affected by these unmet needs. Data from the 2022 KFF WHS underscore that addressing issues with provider availability and cost could improve access to mental health care for some. Our findings suggest that affordability barriers are a substantial obstacle for uninsured women.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and other changes in the health policy environment, larger shares of employers began expanding coverage of mental health services by including more providers for in-person and telehealth care. Telehealth and telemedicine services have been recognized as an evolving strategy to increase access to care and address health needs, including care for mental health. We found that most women who received mental health services via telehealth say the quality of care they received was the same as in-person care. Telehealth has and likely will continue to play a role in addressing mental health access concerns for women.

Despite federal and state laws intended to expand and strengthen coverage for mental health care, gaps in coverage and problems with affordability continue to hinder access to mental health services even for those with private insurance and Medicaid. Our survey finds that in addition to challenges obtaining services, many women who have insurance faced at least some out-of-pocket costs for their visit. The findings from the 2022 KFF WHS suggest that future policies affecting telehealth, provider availability, health insurance coverage, and affordability will play a significant role in addressing the demand for mental health care.

Methodology

Overview

The 2022 KFF Women’s Health Survey is a nationally representative survey of 6,442 people ages 18 to 64, including 5,201 females (self-reported sex at birth) and 1,241 males, conducted from May 10, 2022, to June 7, 2022. The objective of the survey is to help better understand respondents’ experiences with contraception, potential barriers to health care access, and other issues related to reproductive health. The survey was designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) and fielded online and by telephone by SSRS using its Opinion Panel, supplemented with sample from IPSOS’s KnowledgePanel.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Questionnaire design

KFF developed the survey instrument with SSRS feedback regarding question wording, order, clarity, and other issues pertaining to questionnaire quality. The survey was conducted in English and Spanish. The survey instrument is available upon request.

Sample design

The majority of respondents completed the survey using the SSRS Opinion Panel (n=5,202), a nationally representative probability-based panel where panel members are recruited in one of two ways: (1) through invitations mailed to respondents randomly sampled from an Address-Based Sample (ABS) provided by Marketing Systems Group through the U.S. Postal Service’s Computerized Delivery Sequence. (2) from a dual-framed random digit dial (RDD) sample provided by Marketing Systems Group.

In order to have large enough sample sizes for certain subgroups (females ages 18 to 35, particularly females in the following subgroups: lesbian/gay/bisexual; Asian; Black; Hispanic; Medicaid enrollees; low-income; and rural), an additional 1,240 surveys were conducted using the IPSOS KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative probability-based panel recruited using a stratified ABS design.

Data collection

Web Administration Procedures

The majority of surveys completed using the SSRS Opinion Panel (n=5,056) and all of the surveys completed using the KnowledgePanel (n=1,240) were self-administered web surveys. Panelists were emailed an invitation, which included a unique passcode-embedded link, to complete the survey online. In appreciation for their participation, panelists received a modest incentive in the form of a $5 or $10 electronic gift card. All respondents who did not respond to their first invitation received up to five reminder emails and panelists who had opted into receiving text messages from the SSRS Opinion Panel received text message reminders.

Overall, the median length of the web surveys was 13 minutes.

Phone Administration Procedures

In addition to the self-administered web survey, n=146 surveys were completed by telephone with SSRS Opinion Panelists who are web reluctant. Overall, the median length of the phone surveys was 28 minutes.

Data processing and integration

SSRS implemented several quality assurance procedures in data file preparation and processing. Prior to launching data collection, extensive testing of the survey was completed to ensure it was working as anticipated. After the soft launch, survey data were carefully checked for accuracy, completeness, and non-response to specific questions so that any issues could be identified and resolved prior to the full launch.

The data file programmer implemented a “data cleaning” procedure in which web survey skip patterns were created in order to ensure that all questions had the appropriate numbers of cases. This procedure involved a check of raw data by a program that consisted of instructions derived from the skip patterns designated on the questionnaire. The program confirmed that data were consistent with the definitions of codes and ranges and matched the appropriate bases of all questions. The SSRS team also reviewed preliminary SPSS files and conducted an independent check of all created variables to ensure that all variables were accurately constructed.

As a standard practice, quality checks were incorporated into the survey. Quality control checks for this study included a review of “speeders,” reviewing the internal response rate (number of questions answered divided by the number of questions asked) and open-ended questions. Among all respondents, the vast majority (97%) answered 96% or more of the survey questions they received, with no one completing less than 91% of the administered survey (respondents were informed at the start of the survey that they could skip any question).

Weighting

The data were weighted to represent U.S. adults ages 18 to 64. The data include oversamples of females ages 18 to 35 and females ages 36 to 64. Due to this oversampling, the data were classified into three subgroups: females 18 to 35, females 36 to 64, and males 18 to 64. The weighting consisted of two stages: 1) application of base weights and 2) calibration to population parameters. Each subgroup was calibrated separately, then the groups were put into their proper proportions relative to their size in the population.

Calibration to Population Benchmarks

The sample was balanced to match estimates of each of the three subgroups (females ages 18 to 35, females ages 36 to 64, and males ages 18 to 64) along the following dimensions: age; education (less than a high school graduate, high school graduate, some college, four-year college or more); region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West); and race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic-born in U.S., Hispanic-born Outside the U.S., Asian non-Hispanic, Other non-Hispanic). The sample was weighted within race (White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; and Asian) to match population estimates. Benchmark distributions were derived from 2021 Current Population Survey (CPS) data.

Weighting summaries for females ages 18 to 35, females ages 36 to 64, and males ages 18 to 64 are available upon request.

Finally, the three weights were combined, and a final adjustment was made to match the groups to their proper proportions relative to their size in the population (Table 1).

Margin of Sampling Error

The margin of sampling error, including the design effect for subgroups, is presented in Table 2 below. It is important to remember that the sampling fluctuations captured in the margin of error are only one possible source of error in a survey estimate and there may be other unmeasured error in this or any other survey.

KFF Analysis

Researchers at KFF conducted further data analysis using the R survey package, including creating constructed variables, running additional testing for statistical significance, and coding responses to open-ended questions. The survey instrument is available upon request.

Rounding

Some figures in the report do not sum to totals due to rounding. Although overall totals are statistically valid, some breakdowns may not be available due to limited sample sizes or cell sizes. Where the unweighted sample size is less than 100 or where observations are less than 10, figures include the notation “NSD” (Not Sufficient Data).

Statistical significance

All statistical tests are performed at the .05 confidence level. Statistical tests for a given subgroup are tested against the reference group (Ref.) unless otherwise indicated. For example, White is the standard reference for race/ethnicity comparisons and private insurance is the standard reference for types of insurance coverage. Some breakouts by subsets have a large standard error, meaning that sometimes even large differences between estimates are not statistically different.

A note about sex and gender language

Our survey asked respondents which sex they were assigned at birth, on their original birth certificate (male or female). They were then asked what their current gender is (man, woman, transgender, non-binary, or other). Those who identified as transgender men are coded as men and transgender women are coded as women. While we attempted to be as inclusive as possible and recognize the importance of better understanding the health of non-cisgendered people, as is common in many nationally representative surveys, we did not have a sufficient sample size (n >= 100) to report gender breakouts other than men and women with confidence that they reflect the larger non-cisgender population as a whole. The data in our reproductive health reports use the respondent’s sex assigned at birth (inclusive of all genders) to account for reproductive health needs/capacity (e.g., ever been pregnant) while the data in our other survey reports use the respondent’s gender.