What to Know about the Medicare Open Enrollment Period and Medicare Coverage Options

This document was updated on Oct. 4, 2024 to clarify that a new Special Enrollment Period (effective Jan. 1, 2025), which allows individuals who are dually-eligible for Medicare and full Medicaid benefits to make certain changes to their Medicare coverage outside of open enrollment, applies on a monthly basis, not quarterly as was previously stated.

Medicare is the federal health insurance program for 67 million people ages 65 and over and younger adults with long-term disabilities. The program helps to pay for many medical care services, including hospitalizations, physician visits, and prescription drugs, along with post-acute care, skilled nursing facility care, home health care, hospice care, and preventive services.

People with Medicare may choose to receive their Medicare benefits through traditional Medicare or through a Medicare Advantage plan, such as an HMO or PPO, administered by a private health insurer. People who choose traditional Medicare may sign up for a separate Medicare Part D prescription drug plan for coverage of outpatient prescription drugs and may also consider purchasing a supplemental insurance policy to help with out-of-pockets costs if they do not have additional coverage from a former employer, union, or Medicaid. People who opt for Medicare Advantage can choose among dozens of Medicare Advantage plans, which include all services covered under Medicare Parts A and B, and often include Part D prescription drug coverage as well.

Each year, Medicare beneficiaries have an opportunity to make changes to how they receive their Medicare coverage during the nearly 8-week annual open enrollment period. This brief answers key questions about the Medicare open enrollment period and Medicare coverage options.

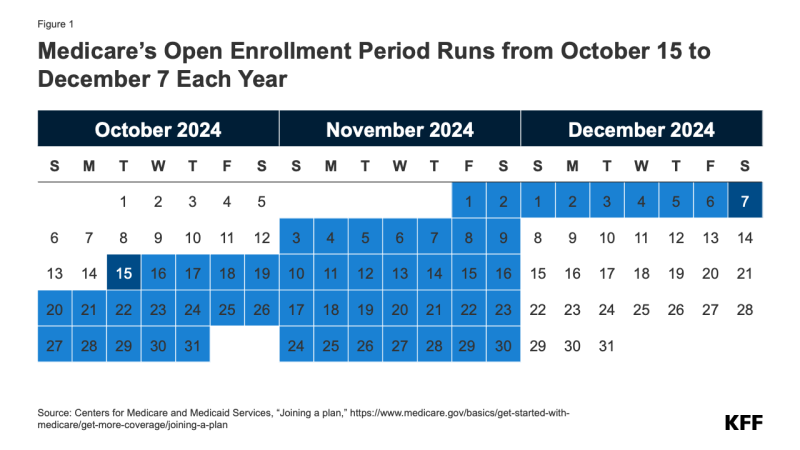

1. When is the annual Medicare open enrollment period?

The annual Medicare open enrollment period runs from October 15th to December 7th each year (Figure 1). During this time, people with Medicare can review features of Medicare plans offered in their area and make changes to their Medicare coverage, which go into effect on January 1st of the following year. These changes include switching from traditional Medicare to a Medicare Advantage plan (or vice versa), switching between Medicare Advantage plans, and electing or switching between Medicare Part D prescription drug plans.

2. What changes can Medicare beneficiaries make during the annual open enrollment period?

People in traditional Medicare can use the Medicare open enrollment period to enroll in a Medicare Part D prescription drug plan or switch between Part D plans. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries who did not sign up for a Part D plan during their initial enrollment period can enroll in a Part D plan during the annual open enrollment period, though they may be subject to a late enrollment penalty if they did not have comparable prescription drug coverage from another plan before signing up for Part D. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries with Medicare Parts A and B can also use this time to switch from traditional Medicare into a Medicare Advantage plan, with or without Part D coverage.

People who are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan can use the Medicare open enrollment period to choose a different Medicare Advantage plan or switch to traditional Medicare. Medicare Advantage enrollees who switch to traditional Medicare can enroll in a Part D plan if they want outpatient prescription drug coverage, which is not covered under Medicare Parts A and B. They may also consider purchasing a Medicare supplemental insurance policy (Medigap) if the option is available to them (see question 4 for details about Medigap and potential limits on enrollment).

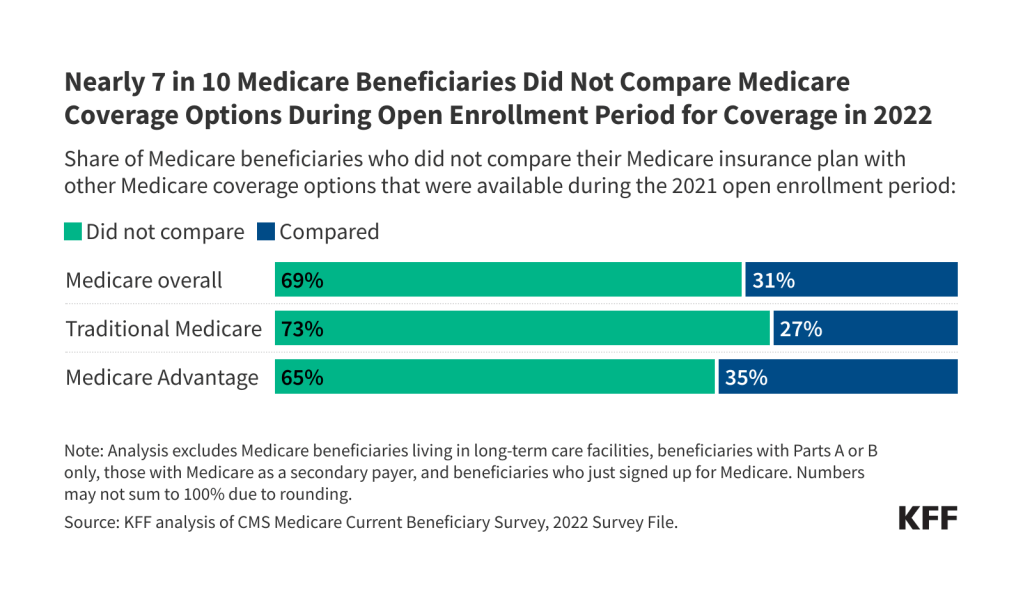

Medicare beneficiaries are encouraged to review their current source of Medicare coverage during the annual open enrollment period and compare other options that are available where they live. Because an individual’s medical needs can change over the course of the year, and from one year to the next, this may influence their priorities when choosing how they want to get their Medicare benefits. Medicare Advantage and Medicare prescription drug plans typically change from one year to the next and may vary in many ways that could have implications for a person’s access to providers and costs. Despite this, a KFF analysis of a nationally representative survey of people with Medicare found that nearly 7 in 10 (69%) did not compare their Medicare coverage options during a recent open enrollment period (Figure 2).

3. Are there other opportunities for Medicare beneficiaries to make coverage changes outside of the open enrollment period?

Some Medicare beneficiaries can make certain changes to their coverage at other times of the year. For example, beneficiaries who experience disruptions to existing coverage (such as a cross-county move or a loss of employer- or union-sponsored coverage) or changes in eligibility for Medicaid or other programs, may qualify for a Special Enrollment Period at any time of year. People who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (i.e., dual-eligible individuals) or who qualify for the Medicare Part D Extra Help program, can currently change their Medicare Advantage or Medicare Part D coverage once per quarter. People living in nursing homes and certain other facilities may change their Medicare Advantage or Medicare Part D coverage once per month.

Beginning on January 1, 2025, new rules go into effect related to the type and frequency of changes dual-eligible individuals and those who qualify for Extra Help can make to their Medicare coverage. Beneficiaries in this group will be allowed to disenroll from a Medicare Advantage plan into traditional Medicare on a monthly basis and may choose to enroll in a stand-alone Part D drug plan at that time. People who receive full Medicaid benefits will only be allowed to switch between Medicare Advantage plans on a monthly basis if switching to a Fully Integrated Dually Eligible Special Needs Plan (FIDE SNP), a Highly Integrated Dually Eligible Special Needs Plan (HIDE SNP), or a coordination-only D-SNP that is an Applicable Integrated Plan (AIP) that is aligned with their Medicaid managed care enrollment. People who receive partial Medicaid benefits, or who qualify for the Extra Help program but do not receive Medicaid benefits, will no longer be allowed to switch between Medicare Advantage plans outside of open enrollment.

Medicare Advantage enrollees who wish to change plans or switch to traditional Medicare may do so between January 1st through March 31st each year, during the Medicare Advantage Open Enrollment Period. (This is in addition to the open enrollment period that runs from October 15th to December 7th.) Additionally, those who have a Medicare Advantage or Medicare Part D plan with a 5-star quality rating available in their area may switch into a 5-star plan between December 8th and November 30th of the following year.

The annual open enrollment period and other opportunities to switch coverage are distinct from the initial enrollment period for people who are newly enrolling in Medicare, which begins three months before a person’s 65th birthday and ends three months after it. For more information on initial enrollment, see the Medicare Open Enrollment FAQ.

4. How does supplemental coverage, like Medigap and employer-sponsored retiree health benefits, factor into Medicare coverage decisions?

Many Medicare beneficiaries have some form of additional coverage, such as a Medicare Supplemental Insurance policy (Medigap) or coverage offered by an employer or a union, that helps with Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements. Enrollment in these plans and programs is not tied to the open enrollment period, though beneficiaries may wish to take them into account when considering their options for Medicare coverage.

Medigap. People in traditional Medicare with both Part A and Part B can apply for a Medigap policy at any time of the year. Medigap policies are designed to help beneficiaries in traditional Medicare with Medicare’s deductibles and cost-sharing requirements and have standard benefits to allow for apples-to-apples comparisons across insurers. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries with a Medigap plan that covers most deductible and cost-sharing requirements may have lower out-of-pocket spending for Medicare-covered services than people with other coverage, including a Medicare Advantage plan. Medigap policies are designed to wrap around traditional Medicare, and do not work with Medicare Advantage. People enrolled in Medicare Advantage do not need (and can’t buy) a Medigap policy.

While Medigap insurers are required to issue policies to people age 65 or over, without regard to health status or diagnosed medical conditions when they first enroll in Medicare, those with pre-existing conditions may be denied a Medigap policy or face higher premiums in most states if they apply for Medigap coverage after their first six months of enrollment in Part B. People who disenroll from Medicare Advantage within 12 months of first enrolling in Medicare Advantage have a right to purchase a Medigap policy without regard to medical history, but after 12 months, they are not guaranteed Medigap coverage and may be denied a policy due to a pre-existing condition or face higher Medigap premiums if they are offered a policy.

Medigap guaranteed issue rights are different for people under age 65 who qualify for Medicare due to long-term disability. Federal law does not require Medigap insurers to sell a policy to people with Medicare under age 65, although several states do require insurers to offer at least one kind of Medigap policy to people under 65. Premiums for Medigap policies sold to people under age 65 are typically higher than policies sold to those age 65 or older. People under age 65 with disabilities who are already enrolled in Medicare will qualify for the 6-month Medigap open enrollment period when they turn 65 and become age eligible for Medicare. At this point, they can buy any Medigap policy they want without facing higher premiums or denials of coverage based on their existing medical conditions.

Employer-sponsored coverage. While employer-sponsored retiree health benefits are on the decline, more than 14.5 million people with Medicare have retiree health coverage (distinct from people with Medicare Part A only who continue to work and have health insurance through their current employer or a spouse’s current employer). Retiree health benefits may be designed to supplement either traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage. Some employers that offer benefits to retirees on Medicare offer retiree health benefits exclusively through a Medicare Advantage plan. Beneficiaries with retiree health coverage offered exclusively through a Medicare Advantage plan may lose retiree health benefits if they choose to switch to traditional Medicare during the annual open enrollment period. Similarly, employers may only offer a retiree health benefit that supplements traditional Medicare. If a person with such coverage switches from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage during an open enrollment period, they may lose their retiree health benefits. In fact, if a Medicare beneficiary drops their employer or union-sponsored retiree health benefits for any reason, they may not be able to get them back.

5. How does additional support for low-income people factor into Medicare coverage decisions?

Low-income Medicare beneficiaries who meet their states’ Medicaid eligibility criteria qualify for additional coverage of services not covered under Medicare, such as long-term services and supports. Additionally, Medicare beneficiaries with modest incomes may qualify for assistance with Medicare premiums and out-of-pocket costs from the Medicare Savings Programs (MSP) and Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) if their income and assets are below certain amounts. Medicare beneficiaries who are eligible for Medicaid, the Medicare Savings Programs, or Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidies, but not yet enrolled in these programs, can enroll at any time of the year. This additional coverage and assistance may factor into how people choose to receive their Medicare benefits.

Medicaid. For people who qualify for full Medicaid benefits, the choice of Medicare coverage can impact how they receive those benefits and the degree to which those benefits are coordinated with Medicare. In general, Medicaid wraps around Medicare coverage, with Medicare as the primary payer and Medicaid paying for costs and services not covered by Medicare. People dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid can enroll in a Medicare Advantage plan designed for this population, such as a dual-eligible special needs plan (SNP), and depending on the state and the plan, experience a higher level of coordination of their benefits. People who qualify for full Medicaid benefits can currently switch their Medicare coverage outside of the open enrollment period, up to once per quarter. Beginning on January 1, 2025, new rules go into effect related to the type and frequency of changes dual-eligible individuals can make to their Medicare coverage (see Q3 for further details).

Medicare Savings Programs. State Medicaid programs pay Medicare premiums and, in many cases, cost sharing for Medicare beneficiaries who have income and assets below certain amounts (though some states have lifted their income and/or asset thresholds above the federal limits). Specifically, states cover the Medicare Part B premium for people who qualify and may also provide assistance with Medicare deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements. People who receive MSP assistance and are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan may still have cost sharing associated with non-Medicare covered services offered by the plan. People who qualify for MSP can also switch their coverage outside of the open enrollment period, up to once per quarter.

Part D Low-Income Subsidy. People who qualify for the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) receive varying levels of assistance toward their Part D prescription drug coverage premiums and cost sharing, depending on their income and asset levels. Dual-eligible individuals and people enrolled in the Medicare Savings Programs automatically qualify for full LIS benefits, and Medicare automatically enrolls them into a stand-alone Part D drug plan in their area with a premium at or below the regional average (the Low-Income Subsidy benchmark) if they do not choose a plan on their own. Other beneficiaries are subject to both an income and asset test and need to apply for the LIS through either the Social Security Administration or Medicaid. People who receive LIS assistance can select any Part D plan offered in their area, but if they enroll in a plan that is not a so-called “benchmark plan” (that is, plans available without a premium to enrollees receiving full LIS), or their current plan loses benchmark status, they may be required to pay some portion of their plan’s monthly premium, which would diminish the value of the subsidy.

6. How do the features of traditional Medicare compare to those of Medicare Advantage?

Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage both provide coverage of all services included in Medicare Part A and Part B, but certain features, such as out-of-pocket costs, provider networks, and access to extra benefits vary between these two types of Medicare coverage. When deciding between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, Medicare beneficiaries may want to consider a variety of factors, such as their own health and financial circumstances, preferences for how they get their medical care, which providers they see, and their prescription drug needs. These decisions may involve careful consideration of premiums, deductibles, cost sharing and out-of-pocket spending; extra benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans; how the choice of coverage option may affect access to certain physicians, specialists, hospitals and pharmacies; rules related to prior authorization and referral requirements; and variations in coverage and costs for prescription drugs.

People may prefer traditional Medicare if they want the broadest possible access to doctors, hospitals and other health care providers. Traditional Medicare beneficiaries may see any provider that accepts Medicare and is accepting new patients. People with traditional Medicare are not required to obtain a referral for specialists or mental health providers. Additionally, prior authorization is rarely required in traditional Medicare and only applies to a limited set of services. With traditional Medicare, people have the ability to choose among stand-alone prescription drug plans offered in their area, which tend to vary widely in terms of which drugs are covered and at what cost.

People may prefer Medicare Advantage if they want extra benefits, such as coverage of some dental and vision services, and reduced cost sharing offered by these plans, often for no additional premium (other than the Part B premium). Additionally, Medicare Advantage plans are required to include a cap on out-of-pocket spending, providing some protection from catastrophic medical expenses. Medicare Advantage plans also offer the benefit of one-stop shopping (i.e., people who enroll have coverage under one plan and do not need to sign up for a separate Part D prescription drug plan or a Medigap policy to supplement traditional Medicare).

7. How do Medicare Advantage plans vary?

The average Medicare beneficiary can choose from 43 Medicare Advantage plans (Figure 3) offered by 8 insurance companies in 2024. These plans vary across many dimensions, including premiums and out-of-pocket spending, provider networks, extra benefits, prior authorization and referral requirements, and prescription drug coverage. As a result, enrollees face different out-of-pocket costs, access to providers and pharmacies, and coverage of non-Medicare benefits (such as dental, vision and hearing) based on the Medicare Advantage plan they choose.

Premiums and out-of-pocket spending. Medicare Advantage enrollees may be charged a separate monthly premium (in addition to the Part B premium). In 2024, the average enrollment-weighted premium for Medicare Advantage plans was $14 per month, though three quarters (75%) of enrollees were in plans that charged no additional premium (apart from the Part B premium).

Medicare Advantage plans are generally prohibited from charging more than traditional Medicare, but vary in the deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance they require. For example, plans typically charge a daily co-pay for hospital stays, which vary both in the amount and the number of days for which they apply.

Medicare Advantage plans are required to include a cap on out-of-pocket expenses. In 2024, this cap may not exceed $8,850 for in-network services or $13,300 for all covered services. Most plans have an out-of-pocket limit below this cap, averaging $4,882 for in-network services and $8,707 for in-network and out-of-network services combined. Out-of-pocket limits only apply to services covered under Medicare Parts A and B.

Provider networks. Medicare Advantage plans are permitted to limit their provider networks, the size of which can vary considerably for both physicians and hospitals, depending on the plan and the county where it is offered. Medicare Advantage plans that include prescription drug coverage may also establish pharmacy networks or designate preferred pharmacies, where enrollees will have lower out-of-pocket costs. If a Medicare Advantage plan provides coverage of out-of-network providers, it may require higher cost sharing from enrollees for these services.

Extra benefits. Medicare Advantage plans may choose to offer extra benefits not covered by traditional Medicare, such as some coverage of dental, vision, and hearing services. Virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees are in a plan that offers extra benefits, including some coverage of eye exams and/or eyeglasses (more than 99%), dental care (98%), hearing exams and/or aids (96%), and a fitness benefit (95%). Additionally, a majority of Medicare Advantage enrollees are in plans that provide an allowance for over-the-counter items (88%) and meals following a hospital stay (74%). While extra benefits are common, the scope of coverage varies widely from plan to plan. For example, in 2021, more than half (59%) of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in a plan with a maximum dental benefit of $1,000 or less, while nearly one-third (30%) were in a plan with a limit between $2,000 and $5,000.

Prior authorization and referral requirements. Medicare Advantage plans may require enrollees to receive prior authorization before a service will be covered. In 2022, more than 46 million prior authorization requests were submitted to insurers on behalf of Medicare Advantage enrollees, and in 2024, virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required prior authorization for some services, such as inpatient hospital stays, diagnostic tests and procedures, or stays in a skilled nursing facility. Prior authorization may also be required for some services included in a plan’s extra benefits, such as hearing and eye exams or comprehensive dental services. In addition, Medicare Advantage plans may require enrollees to obtain a referral from a primary care provider in order to see a specialist or mental health provider.

Prescription drug coverage. Medicare Advantage enrollees who want prescription drug coverage must choose a plan that offers this coverage, as they are not permitted to enroll in a stand-alone prescription drug plan while enrolled in Medicare Advantage. Medicare Advantage plans that include prescription drug coverage may also charge a drug deductible. Drug coverage in Medicare Advantage plans varies along the same dimensions as drug coverage in stand-alone Part D plans (described below).

8. How do Part D plans vary?

The average Medicare beneficiary has 21 stand-alone Part D plans to choose from in 2024 (Figure 4) (in addition to a large number of Medicare Advantage drug plans, if they want to consider Medicare Advantage for all of their Medicare-covered benefits). For traditional Medicare beneficiaries who want to add Part D coverage, stand-alone Part D plans vary in terms of premiums, deductibles and cost sharing, the drugs that are covered and any utilization management restrictions that apply, and pharmacy networks. These differences can affect enrollees’ access to prescription drugs and out-of-pocket costs.

Premiums. People in traditional Medicare who are enrolled in a separate stand-alone Part D plan generally pay a monthly Part D premium unless they qualify for full benefits through the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) program and are enrolled in a premium-free (benchmark) plan. In 2024, the average enrollment-weighted premium for stand-alone Part D plans was $43 per month. Changes to the Part D benefit in the Inflation Reduction Act, such as the new $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket drug spending for Part D enrollees, will mean lower out-of-pocket costs for many Medicare beneficiaries but higher costs for Part D plans overall, leading to concerns about possible premium increases for 2025 (see Q9 for further discussion of the Inflation Reduction Act).

Deductibles and cost sharing. Deductibles and cost-sharing requirements for prescription drug coverage are variable. Plans generally impose a tier structure to define cost sharing requirements and cost sharing amounts charged. Plans typically charge lower cost-sharing amounts for generic drugs and preferred brands and higher amounts for non-preferred and specialty drugs, and charge a mix of flat dollar copayments and coinsurance (based on a percentage of a drug’s list price) for covered drugs.

Drugs covered and utilization management restrictions. Part D plans include a list of drugs they cover (also referred to as a plan’s formulary). In addition, plans may also impose utilization management restrictions on covered prescription drugs, including prior authorization, quantity limits, and step therapy, which can affect beneficiaries’ access to medications. In 2024, around 30% of covered drugs are subject to prior authorization.

Pharmacy networks. Part D prescription drug plans may establish pharmacy networks or designate preferred pharmacies, where enrollees will have lower out-of-pocket costs.

9. Do the Medicare prescription drug changes in the Inflation Reduction Act differ across Medicare coverage options?

No. The prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 that aim to lower out-of-pocket costs apply to all Part D plans, including both stand-alone Part D plans and Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plans. Regardless of whether beneficiaries get their drug coverage from a stand-alone Part D plan or a Medicare Advantage drug plan, they will benefit from these changes.

As of 2023, cost sharing for insulin is now capped at $35 per month per prescription. All Medicare Part D plans, both stand-alone drug plans and Medicare Advantage drug plans, will be required to charge no more than $35 for whichever insulin products they cover, although plans will not be required to cover all insulin products. Beneficiaries who use a specific insulin product should verify coverage of their product before enrolling in a specific plan.

Also as of 2023, adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D that have been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) must now be covered at no cost to enrollees. This change does not impact the small number of vaccines covered under Medicare Part B (such as the flu, pneumonia, and COVID-19 vaccines), many of which were already covered free of cost. Finally, drug companies are now required to pay rebates to the Medicare program if the cost of drugs used by Medicare beneficiaries rises faster than the rate of inflation each year, similar to the rebate system used by the Medicaid program.

Additional provisions came into effect at the start of 2024, which include phasing in a cap on out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs covered under Medicare Part D by eliminating cost sharing above the catastrophic threshold in 2024 and expanding eligibility for full benefits under the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program, which assists qualifying beneficiaries with their Part D premiums, deductibles, and cost-sharing expenses.

Starting in 2025, Medicare beneficiaries will pay no more than $2,000 out of pocket for the prescription drugs they take that are covered under Medicare Part D. Other changes to the Medicare Part D program will be introduced in future years.

10. What resources are available to assist Medicare beneficiaries in understanding their coverage options?

People with Medicare can learn more about Medicare coverage options and the features of different plan options by reviewing the Medicare & You handbook. In addition, people can review and compare the Medicare options available in their area by using the Medicare Plan Compare website, a searchable tool on the Medicare.gov website, by calling 1-800-MEDICARE (1-800-633-4227), or by contacting their local State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP). SHIPs offer local, personalized counseling and assistance to people with Medicare and their families. Contact information for state SHIPs can be found by calling 877-839-2675 or by checking the listing provided on the Medicare.gov website.

Additionally, many people use insurance agents and brokers to navigate their coverage options. While helpful, agents and brokers are financially compensated by private insurers for enrolling people in their plans, and often receive higher commissions if people choose a Medicare Advantage plan rather than remaining in traditional Medicare and purchasing a supplemental Medigap policy and stand-alone Part D plan.

Irving Washington

Irving Washington  Hagere Yilma

Hagere Yilma