Data Note: Changes in Enrollment in the Individual Health Insurance Market through Early 2019

Data Note

The individual health insurance market – where people go to buy their own coverage both through the exchange Marketplaces and off-exchange directly from insurers or brokers – grew rapidly following implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) subsidies and prohibition of discrimination based on pre-existing conditions. However, these enrollment gains were partially offset by subsequent declines, particularly among people not receiving subsidies amid steep premium increases. Most recently, the ACA’s individual mandate penalty was effectively repealed going into 2019, raising questions over whether enrollment would continue to drop.

Enrollment in the individual market dips slightly in first quarter of 2019 after repeal of individual mandate penalty, though ACA Marketplace plan enrollment holds steady via @KFF

In this analysis, we use publicly-available federal enrollment data and administrative data insurers report to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (as compiled by Mark Farrah Associates) to measure changes in enrollment in the individual market before and after the ACA’s coverage expansions and market rules went into effect in 2014 through the first quarter of 2019. Key findings include:

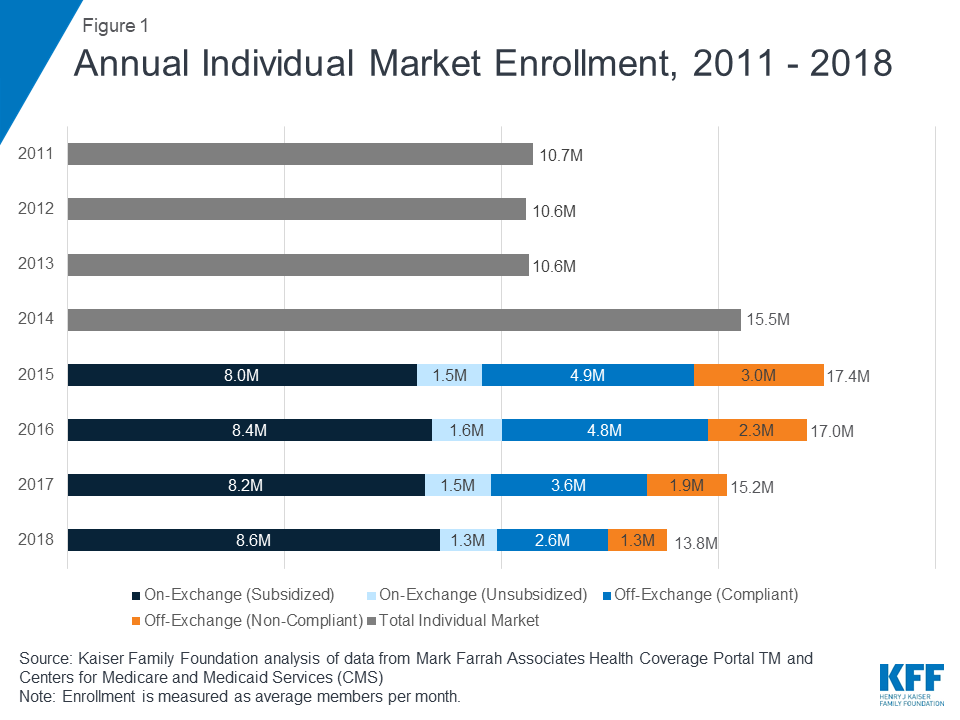

- Total individual market enrollment, measured on an average monthly basis, increased from 10.6 million in 2013 to a peak of 17.4 million in 2015, before declining to 13.8 million in 2018.

- Much of this decline was concentrated in the off-exchange market, where enrollees are not eligible for federal premium subsidies and therefore were not cushioned from the significant premium increases in 2017 and 2018.

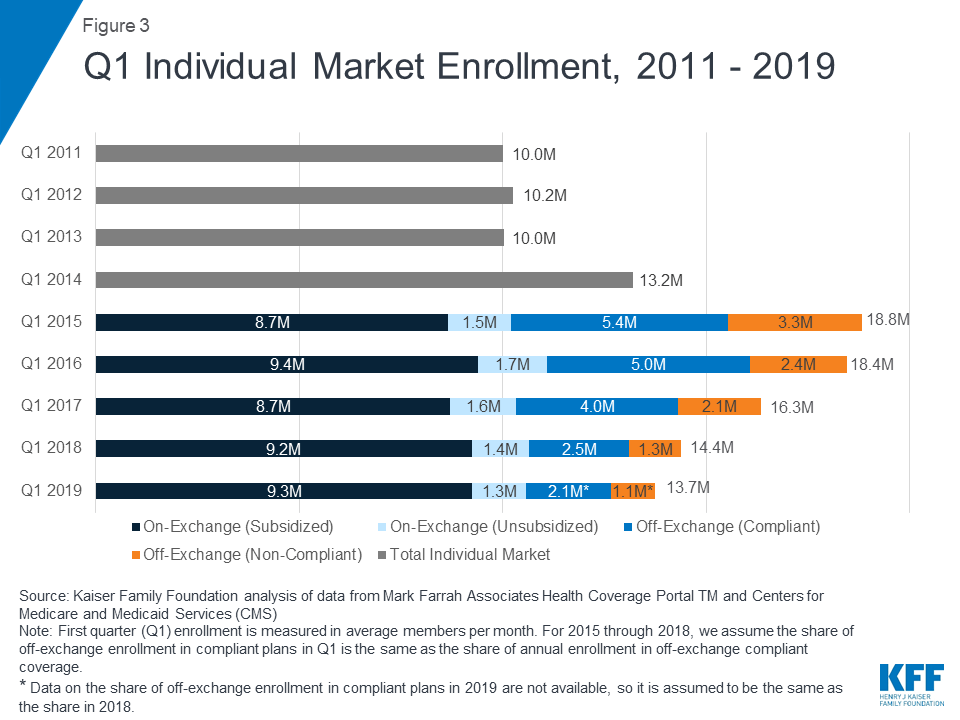

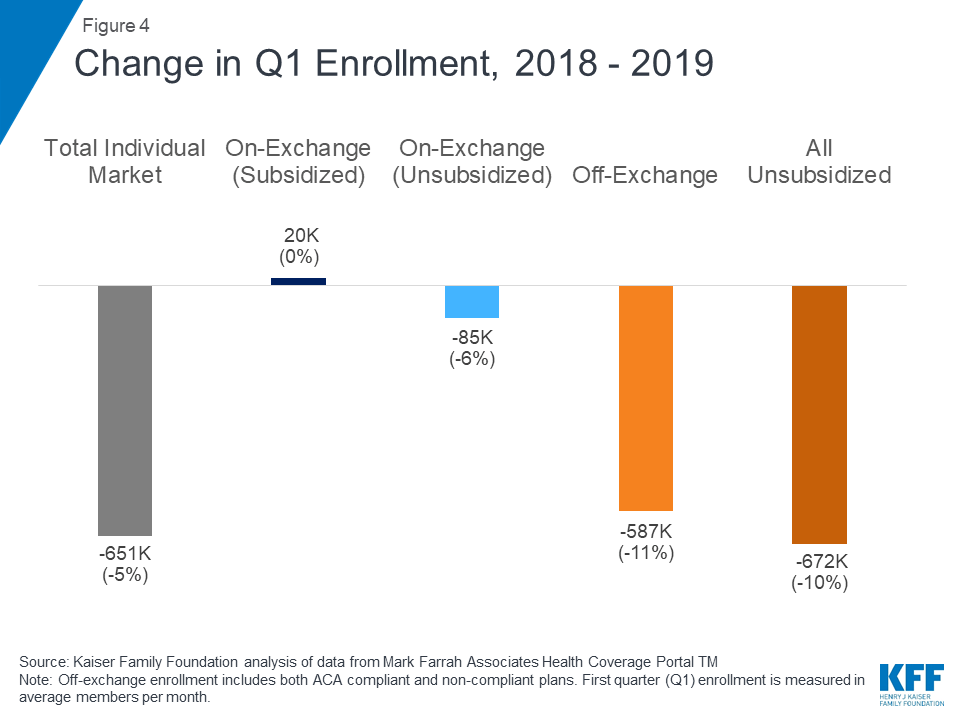

- Enrollment has continued to fall somewhat in early 2019, though may show signs of stabilizing, so long as premium growth continues to level off: First quarter enrollment has declined by 5% in 2019 compared to the first quarter of 2018.1 This is a smaller decline than had been seen in past years (11% in 2018 and 12% in 2017) amid steep premium increases.

- There are 13.7 million people enrolled as of the first quarter of 2019, compared to 10.6 million people in 2013, before the ACA went into effect.

Annual Changes in Individual Market Enrollment through 2018

The individual market comprises coverage purchased by individuals and families through the ACA’s exchanges (Marketplaces) as well as coverage purchased off-exchange, which includes both plans complying with the ACA’s rules and non-compliant coverage (e.g., grandfathered policies purchased before the ACA went into effect and short-term plans). The individual market (sometimes also called the nongroup market) is relatively small as a share of the U.S. population, with about 10.6 million people enrolled in 2013 before the ACA went fully into effect2 .

As the ACA market rules and premium subsidies were implemented in 2014, there was significant growth in enrollment on the individual market. For the first time in nearly all states, people with pre-existing conditions could purchase coverage on an open marketplace and low-income people were eligible for tax credits to help pay their premiums and reductions in their cost sharing. In addition, many people who went without insurance coverage had to pay a tax penalty. As of 2014, health plans had to follow new rules that standardized benefits and guaranteed coverage for those with pre-existing conditions when selling coverage to new customers (known as “ACA-compliant” plans). Following these changes, individual market enrollment increased substantially, expanding from 10.6 million members on average per month in 2013 to 17.4 million members in 2015 (Figure 1)3 . This included an estimated 3 million people in non-ACA compliant plans including some short-term plans, grandfathered plans, and plans purchased before October 2013 that were allowed to continue under a federal transition policy at the discretion of states and insurers.

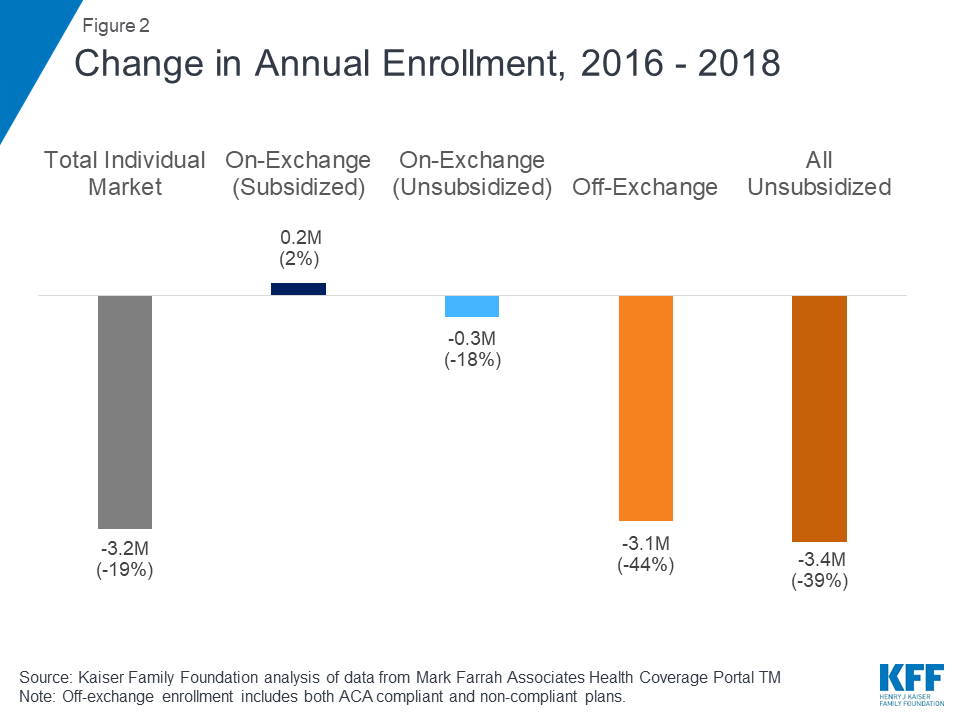

In 2016, total individual market enrollment was relatively unchanged from the previous year (at 17.0 million), though there was a shift from non-compliant to ACA-compliant plans. Enrollment in the total individual market began to decline in 2017 and continued through 2018 (Figure 2). Both compliant and non-compliant enrollment declined, suggesting that people ending transitional, non-compliant policies were not necessarily moving to the ACA-compliant market. In 2018, enrollment in compliant plans decreased further to 12.5 million and enrollment in non-compliant plans decreased to 1.3 million.

Quarterly Changes in Individual Market Enrollment through Early 2019

First quarter enrollment data from 2019 show total individual enrollment continuing to decline somewhat as premiums leveled off, even as enrollment on the ACA exchanges has remained relatively stable (Figure 3). 13.7 million people are enrolled in the individual market as of the first quarter of 2019, 5% lower than the first quarter of 2018 – a drop of about 651 thousand people.

Exchange Coverage

Exchange enrollment, particularly subsidized exchange enrollment, has largely remained stable since 2015. In the first quarter of 2019, 10.6 million people were covered on the ACA exchanges, including 9.3 million people receiving federal premium subsidies4 . Early 2019 exchange enrollment shows little change from the first quarter of 2018 when 10.6 million people were covered on-exchange, including 9.2 million receiving subsidies. As most people on the exchange receive subsidies that cap their premium payments at a certain share of their income, these enrollees are sheltered from the sticker price of premiums and would therefore be unlikely to drop their coverage due to changes in premiums.

Although exchange enrollment has held steady, according to CMS, the number of new consumers signing up for plans in 2019 dropped by 16% from 3.2 million to 2.7 million. This drop in new signups could be a result of a variety of factors, such as reductions in outreach and consumer assistance, repeal of the individual mandate penalty, or broader economic factors that may make people less likely to come into the market.

Off-Exchange Coverage

Declining off-exchange enrollment accounts for much of the drop in individual market enrollment since 2016. Total individual market enrollment began to decline in 2017 and has continued to fall through the first quarter of 2019 (Figure 4). Total individual market enrollment declined by 651 thousand people (5%) from the first quarter of 2018 to the first quarter of 2019. All of this decline was among unsubsidized enrollees, whose enrollment fell by 672 thousand (10%) from 2018 to 2019 (across unsubsidized ACA-compliant and non-compliant coverage).

Off-exchange enrollment includes ACA-compliant plans that are sold outside of the exchange but are part of the same risk pool as exchange plans, as well as non-compliant plans that do not meet ACA standards and have separate risk pools from the ACA-compliant plans. The primary distinction between on and off exchange ACA-compliant plans is that subsidies are only available through the exchange. To the extent that fewer healthy people buy off-exchange ACA-compliant plans, premiums in on-exchange plans are affected as well. Non-compliant plans (including grandfathered and some short-term plans) that are not part of the ACA risk pool are also included in off-exchange enrollment.

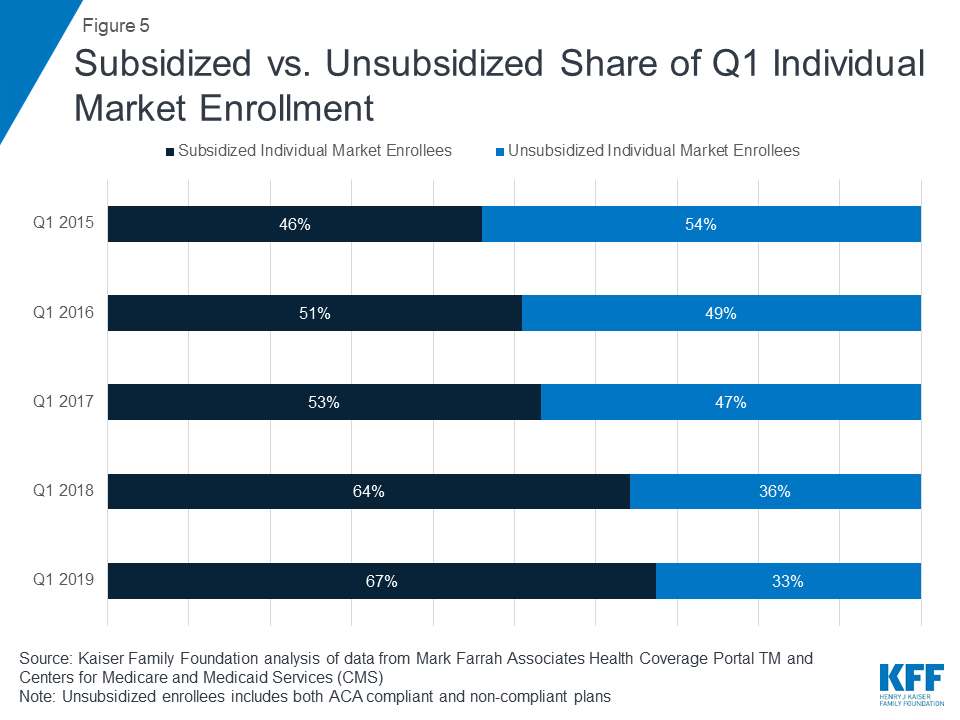

As unsubsidized enrollment has fallen over recent years, the individual market has increasingly become dominated by subsidized enrollees. In the first quarter of 2019, we estimate over two thirds of enrollees in the individual market are receiving a premium subsidy (Figure 5).

Limitations of Q1 Non-Compliant Coverage Estimates

In the first quarter of 2019, we estimate 2.1 million people were covered by off-exchange ACA-compliant plans, and 1.1 million people had non-compliant plans.5 A limitation of this analysis is that precise data on the number of people in non-compliant plans in early 2019 are not yet available. Additionally, while there are some data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners on enrollment in short-term plans, these data are only available annually (so do not include 2019) and do not account for all short-term coverage, as some plans are sold through associations and would not necessarily be considered individual market coverage. In Figure 3 above, we estimate the share of off-exchange individual market enrollees who are in ACA-compliant and non-compliant plans in early 2019 by assuming the same share as in 2018. In past years, this method has proven to be reliable, however, 2019 may differ from past years because this is the first year in which the individual mandate penalty has effectively been repealed and more loosely regulated plans may have proliferated.

Annual filings provide a more complete picture of the individual market and allow for more precise estimates of compliant vs non-compliant enrollment. Quarterly filings provide a sense of how enrollment is changing on a more current basis. First quarter enrollment tends to be higher than average annual enrollment because the number of people who drop coverage throughout the year exceeds the number who purchase coverage through special enrollment periods outside of annual open enrollment.

Possible Reasons for Individual Market Enrollment Declines

There are a variety of possible explanations for these declines in individual market enrollment in recent years, including: rising premiums for ACA-compliant coverage; the expansion of loosely regulated plans that may not be considered individual market coverage yet could attract customers away from the individual market; the effective repeal of the individual mandate; and broader economic trends, like gains in employment, which could lead to more people having job-based coverage. While we know that individual market enrollment has declined in 2019, we do not yet know whether people leaving the individual market have gained coverage through other sources.

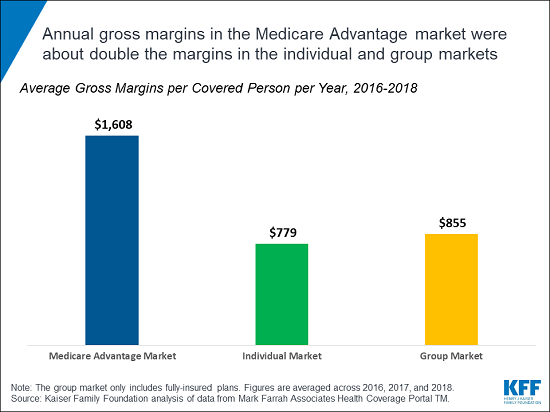

The most significant declines in individual market enrollment coincided with significant premium increases in 2017 and 2018. In the early years of the ACA exchanges, insurers underestimated how sick the new risk pool would be and set premiums too low to cover their claims. A number of insurers then exited the market and the remaining insurers raised premiums substantially on average to match their costs. Our analysis of insurer financials showed the market was stabilizing by 2017 and insurers were starting to become profitable in the individual market for the first time under the ACA. Signs pointed toward the 2017 premium increases being a one-time market correction. However, premiums increased again in 2018, in large part compensating for uncertainty around the ACA repeal debates in Congress and the Trump Administration’s termination of cost sharing payments.

While the vast majority of exchange consumers receive subsidies that protect them from premium increases, off-exchange consumers in ACA-compliant plans bear the full cost of premium increases each year. In 2017 and 2018, states that had larger premium increases generally saw larger declines in unsubsidized ACA-compliant enrollment (Figure 6), suggesting a possible relationship between premium hikes and enrollment drops.

Figure 6

Going into 2019, premiums held mostly flat on average but the individual mandate penalty was reduced to $0, effectively doing away with the ACA’s requirement to purchase health insurance. Despite the lack of penalty, subsidized enrollment largely held steady. We estimate enrollment in unsubsidized off-exchange ACA-compliant plans declined by about 400 thousand from 2018 to 2019 (corresponding with the effective repeal of the individual mandate penalty but also relatively flat premium growth), which is smaller than previous declines in this part of the market that corresponded with steep increases in premiums.

Discussion

The effective repeal of the individual mandate penalty has raised concerns of enrollment declines in the individual market, particularly among people who are healthier than average. Expanded options to purchase loosely-regulated short-term health plans were also expected to siphon away healthy people, pushing premiums up a bit further for ACA-compliant plans on and off the exchange.

While the effective repeal of the individual mandate penalty and expanded access to loosely-regulated plans had an upward effect on 2019 premiums, other factors (like prior over-pricing) had a downward effect and resulted in average 2019 premiums being similar to 2018. We find that, while enrollment in the individual market has declined somewhat in early 2019, there are signs that enrollment may stabilize after a couple turbulent years.

There are many possible reasons for changes in enrollment, including the state of the economy and the number of people eligible for job-based coverage or public programs like Medicaid, and it is outside the scope of this analysis to determine which factors are driving these changes or whether they have any net effect on the overall insured rate. Nonetheless, given continued strong financial performance by individual market insurers and enrollment that remains higher than before the ACA, there do not appear to be any signs of market collapse so far in the absence of the individual mandate penalty.

The majority of people on the exchanges receive subsidies and are protected from premium increases, which in turn has a strong stabilizing effect on the individual market as a whole. As long as subsidies continue, the individual market will likely remain stable under current law. Nevertheless, middle-class people who do not qualify for subsidies will feel the brunt of any future premium increases. This is especially true of people with pre-existing conditions who likely would not qualify for short-term plans that base eligibility and premiums on people’s health. So while there may be no signs of the individual market collapsing, there remain concerns about affordability of coverage for people who do not qualify for a subsidy, many of whom have already left the individual market. The numbers also provide some perspective on the often hot debate over the ACA’s marketplaces. More than 150 million people are covered through the employer market, 11 times the number covered in the individual market overall and 14 times the number covered through the marketplaces.

Methods

We analyzed publicly-available federal enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and insurer-reported enrollment and financial data from Health Coverage Portal TM, a market database maintained by Mark Farrah Associates, which includes information from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) and the California Department of Managed HealthCare. All total enrollment figures in this data note are for the individual health insurance market as a whole, which includes major medical insurance plans sold both on and off exchange.

Exchange and compliant enrollment are from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Total individual market enrollment is from administrative data insurers report to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, and compiled by Mark Farrah Associates: annual enrollment is from the Supplemental Health Exhibit and first quarter enrollment is from the Exhibit of Premiums, Enrollment, and Utilization for health companies and rolled over from the prior year Supplemental Health Exhibit for life companies. Off-exchange enrollment is estimated by subtracting exchange enrollment from total enrollment in the individual market. Non-compliant enrollment is estimated by subtracting compliant enrollment from total enrollment in the individual market. CMS does not collect enrollment data for off-exchange ACA compliant plans in Massachusetts or Vermont; in these states, non-compliant enrollment was estimated by applying the national average share of non-compliant off-exchange members to statewide off-exchange enrollment.

Annual enrollment figures from 2011 – 2018 are average monthly enrollment. Quarterly enrollment figures in 2019 are effectuated enrollment (i.e., people who paid their first month’s premiums). For 2015 through 2018, we assume the share of off-exchange enrollment in compliant plans in Q1 is the same as the share of annual enrollment in off-exchange compliant coverage. Data on the share of off-exchange enrollment in compliant plans in 2019 are not available, so it is assumed to be the same as the share in 2018. As described above, this assumption may be inaccurate given changes in policy that took effect in 2019 and could change the distribution of people signed up in off-exchange ACA-compliant coverage as opposed to non-compliant coverage.

Endnotes

- First quarter enrollment is generally higher than average annual enrollment, because people drop coverage throughout the year after the annual open enrollment period. In this brief, we compare first quarter 2019 enrollment to first quarter enrollment in previous years to estimate how enrollment is changing over time. ↩︎

- Estimates of the size of the individual market vary between administrative and survey data; a more thorough discussion of methods for measuring the individual market size can be found here. ↩︎

- ACA changes came into effect in 2014, but 2014 average enrollment is not necessarily comparable because the first open enrollment lasted for 6 months. ↩︎

- Exchange enrollment is measured as the number of enrollees who selected a plan during open enrollment and paid their first month’s premium (effectuated enrollment). In 2014, open enrollment lasted for six months and CMS did not report effectuated enrollment in the first quarter. In 2015 and 2016, CMS reported effectuated enrollment as of March 31st. In 2017, 2018, and 2019, CMS reported effectuated enrollment as of March 15th, and did not include policies starting on March 1st. Open enrollment for 2017 continued through the end of January, but for the 2018 and 2019 plan years it ended on December 15. It is likely, therefore, that effectuated enrollment for 2017 was somewhat understated relative to 2018 and 2019. ↩︎

- For 2015 through 2018, we assume the share of off-exchange enrollment in compliant plans in Q1 is the same as the share of annual enrollment in off-exchange compliant coverage. Data on the share of off-exchange enrollment in compliant plans in 2019 are not available, so it is assumed to be the same as the share in 2018. ↩︎