5 Key Facts About Medicaid and Pregnancy

Improving maternal and infant health is a national priority at the state and federal level. In the face of preventable maternal mortality, stark racial and ethnic disparities, and large gaps in the availability of maternity and reproductive health care in many communities, policymakers, clinicians, and other health care stakeholders have turned to the Medicaid program to improve the health of women and children.

As a primary payer for maternity care in the U.S., the Medicaid program is an integral component of maternal and infant health in the country. Many federal initiatives aiming to improve maternal and infant health include policies to strengthen the Medicaid program, and many state program leaders cite improving maternal and child health as a top priority. President Trump and other conservatives have called for increasing the birth rate. At the same time, Congress is considering changes to Medicaid that would reduce federal spending on the program and lead to an estimated 7.6 million people losing Medicaid coverage and becoming uninsured. This brief examines Medicaid’s pregnancy and postpartum coverage and its support for strengthening and improving maternal health outcomes.

1. Medicaid finances over four in ten births nationally and nearly half of births in rural communities.

Medicaid is the largest single payer of pregnancy-related services, financing 41% of births nationally in 2023 (Figure 1) and over half of births in four states (Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma). The program plays a particularly large role in rural areas, paying for nearly half (47%) of all births in rural communities and helping to shore up financing for hospitals in rural areas suffering from provider shortages. Rural counties in states with more expansive Medicaid eligibility criteria for pregnancy coverage are more likely to have hospitals that provide obstetric services than rural counties in states with more restrictive program eligibility thresholds. Recognizing the importance of assuring that pregnant people have access to care, federal Medicaid law also explicitly prohibits out-of-pocket charges for any pregnancy-related care, an important protection for pregnant people covered by the program, as out-of-pocket health expenses for maternity care can reach thousands of dollars.

2. All states have chosen to extend Medicaid eligibility to pregnant people beyond the federal minimum requirements.

By federal law, the minimum Medicaid eligibility level for pregnant women is 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), which is $36,770 for a family of three. Many states also use the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) program to extend eligibility to pregnant women at higher income levels. However, nearly all states, across partisan divides, have used their flexibility to set Medicaid income eligibility criteria for pregnancy above the minimum requirement so that more pregnant people can qualify for coverage. As a result, the median eligibility limit (Figure 2) for pregnancy coverage in Medicaid and CHIP is well above the minimum requirement in states that voted for President Trump (205% FPL) and states that voted for former Vice President Harris (217% FPL).

Many states chose to broaden eligibility for pregnant people during the 1980s, in part responding to high rates of infant mortality, particularly in southern states. Recognizing the importance of prenatal care for both maternal and infant health outcomes, states embraced the opportunity to cover pregnant people and get them into care as early as possible.

3. States use Medicaid to strengthen and improve maternal health care quality and outcomes.

Amid a national crisis in maternal health, characterized by high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity, regional shortages in maternity clinicians, closures of maternity wards in rural and urban communities, and ongoing concerns about reproductive care access, several states are leveraging their Medicaid programs to improve the quality of maternity care and maternal health outcomes. These efforts include increased investment in outreach and education to enrollees and providers about maternal health issues; expanded coverage for benefits such as doula care, home visits, and substance use disorder and mental health treatment; and use of new payment, delivery, and performance measurement approaches. For example, South Dakota has created a pregnancy care management program that offers enhanced reimbursement to providers for care coordination and meeting prenatal and postpartum care program objectives.

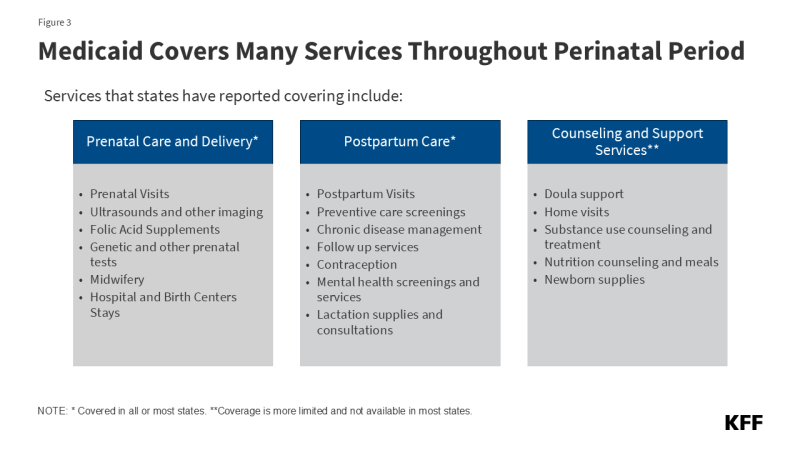

KFF research has found that most states cover a broad range of maternity care services, including prenatal screenings, folic acid supplements, labor and delivery, and breastfeeding supports (Figure 3). In addition, a growing number of states have expanded benefits beyond traditional maternity services in recent years, such as for doula services and home visiting programs, to promote better maternal and infant health outcomes and reduce racial/ethnic health disparities. Some states are focusing on other support services. For example, Nebraska, Tennessee, and New Jersey are piloting programs that provide nutrition counseling and medically indicated meals for pregnant/postpartum individuals. In the face of federal funding cuts, these program enhancements may be difficult or impossible for states to continue to support.

4. Medicaid expansion broadens access to Medicaid coverage before pregnancy, providing an important pathway to primary and preventive care that has been demonstrated to improve pregnancy outcomes.

Decades of research has found that pre-pregnancy health is a key determinant of both maternal and infant outcomes. Coverage prior to pregnancy provides access to important primary and preventive care as well as the opportunity to assess and manage chronic diseases that affect pregnancy, including hypertension, obesity, and diabetes. KFF research finds that Medicaid expansion covers 38% of women ages 19-49 enrolled in the program. Women in Medicaid expansion states are more than twice as likely (Figure 4) to be enrolled in the program prior to becoming pregnant compared to women in non-expansion states (59% vs. 26%). Conversely, most women in non-expansion states obtained Medicaid coverage only after becoming pregnant, with about one-third (34%) enrolling after the first trimester. As a result, Medicaid expansion is associated with increased use of prenatal services as well as lower rates of adverse birth outcomes such as low birthweight newborns. Federal law stipulates that children born to women covered by Medicaid are automatically eligible and enrolled in the program for the first year of their life.

5. Individuals who qualify for Medicaid during pregnancy face an income eligibility cliff one year after giving birth, but the cliff is not as steep in expansion states.

Until recently, Medicaid pregnancy coverage ended at 60 days postpartum. This changed with a provision in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 that gave states a new option to extend postpartum coverage to 12 months. Today, all but two states (Arkansas and Wisconsin) have adopted this optional eligibility extension, which means that birthing parents can stay covered for a year.

Medicaid eligibility levels for parents are much more restrictive than those related to pregnancy, which means that in all states some new parents no longer qualify for Medicaid after the postpartum period, but there is a divide in access to coverage between expansion and non-expansion states. In states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, new parents with income below 138% FPL can retain Medicaid eligibility and those with income above that level are generally eligible for subsidized coverage in the Marketplace. In contrast, in states that have not adopted Medicaid expansion, more low-income parents are at risk of becoming uninsured just as their children enter the toddler years because adults with incomes below the poverty level do not qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace and because of the extremely low Medicaid eligibility levels for parents (Figure 5). For example, in Texas, parents in a family of three only qualify for continued Medicaid coverage after the postpartum period if they make less than $3,900 a year (15% FPL). Across all non-expansion states, median eligibility for parents is 33% FPL, which is approximately $8,800 annually for a family of three.

Medicaid expansion offers continuous coverage following the postpartum period for many parents and promotes access to care for many parents’ ongoing health needs, including conditions that may have been identified during pregnancy but require ongoing care and treatment. This includes many chronic diseases that are leading causes of adverse maternal health outcomes, such as hypertension and other cardiovascular conditions as well as depression and other mental health conditions. KFF research shows that women in Medicaid expansion states are able to retain coverage for longer periods after a delivery. The program’s coverage of contraception and family planning can help people prevent, plan, and space subsequent pregnancies for optimal outcomes.