50-State Survey of Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies in 2017: A Baseline for Measuring Future Changes

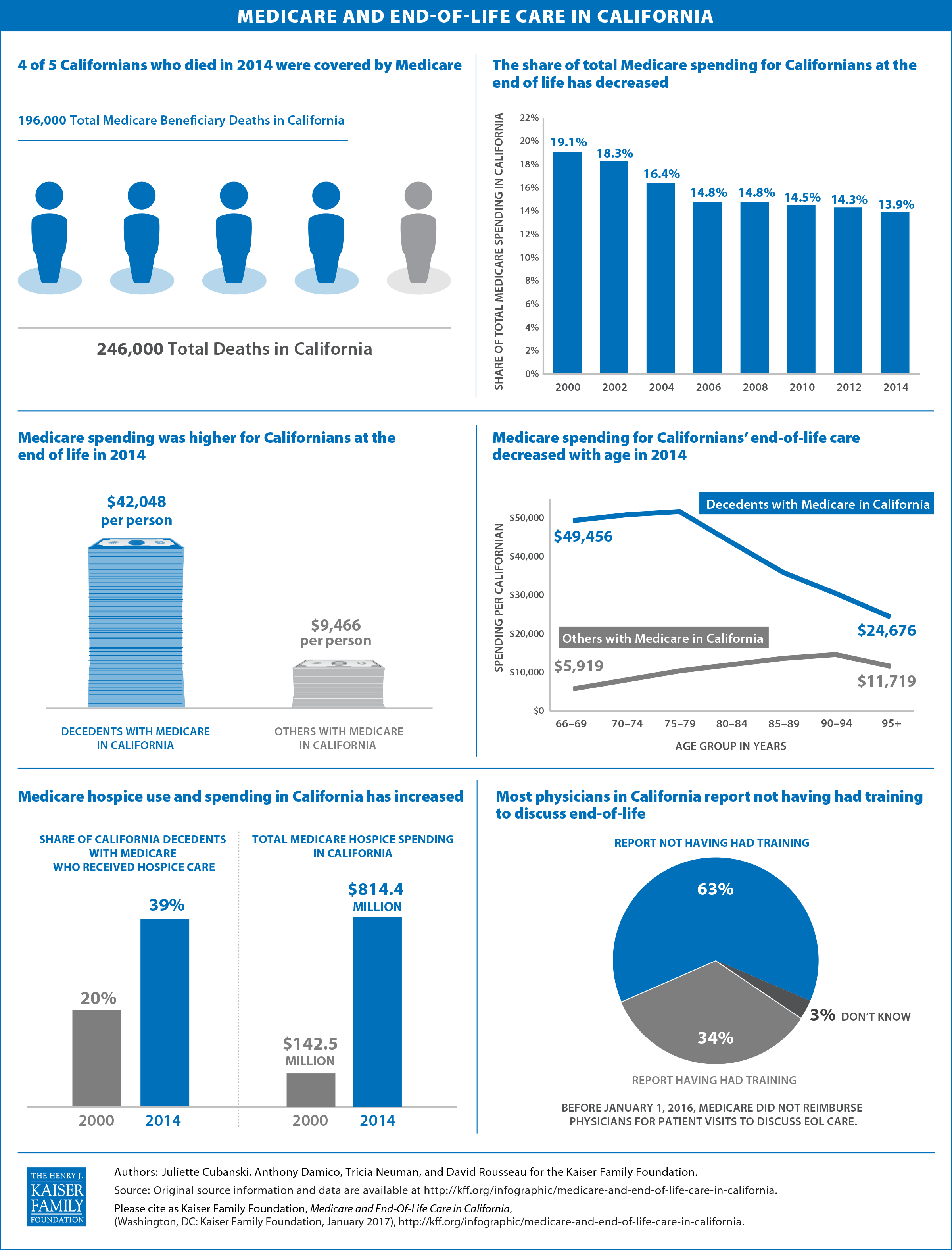

As the Trump administration and Republican leadership in Congress begin a new term and seek to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a new 50-state survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation offers an in-depth profile of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies in each state as of January 2017, providing a baseline against which future policy changes may be measured.

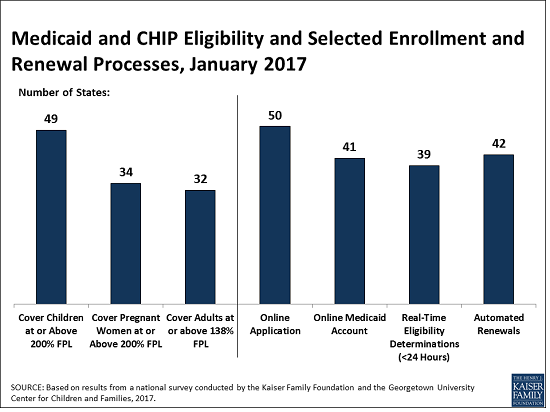

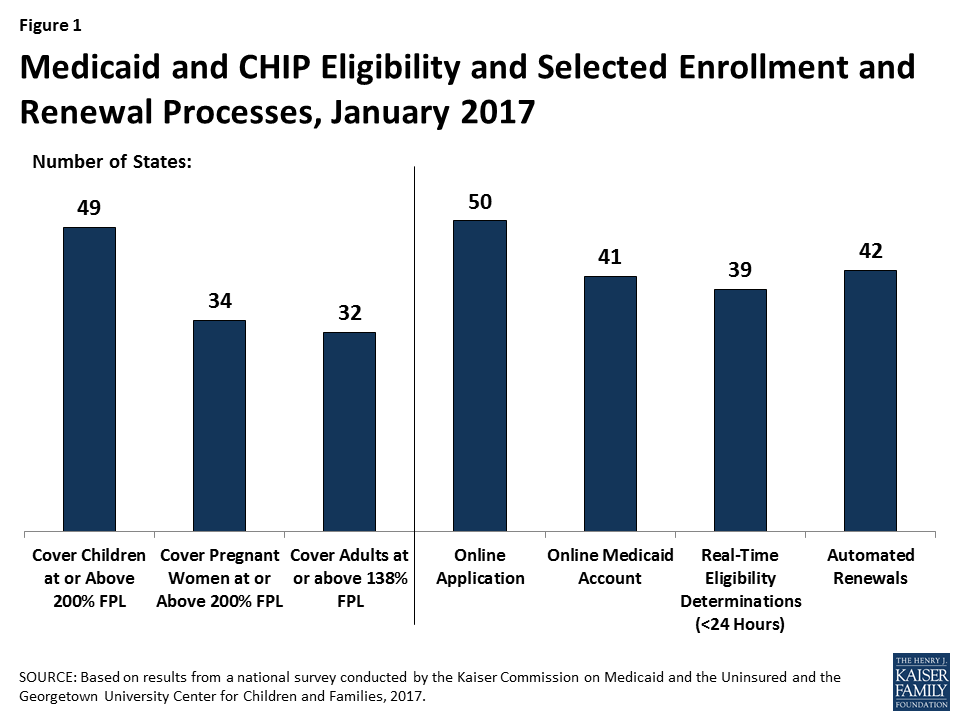

Changes to Medicaid and CHIP could affect coverage for many of the nation’s low-income families and adults given the central role these programs play in providing coverage, as shown in the survey findings. As of 2017, 49 states cover children and 34 states cover pregnant women with incomes at or above two times the federal poverty level ($40,320 for a family of three). Thirty-two states cover low-income parents and other adults with incomes up to at least 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($27,820 for a family of three), reflecting their adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. In the 19 states that have not adopted the expansion, the median eligibility limit for parents remains at 44 percent of the federal poverty level and other adults without dependent children are not eligible regardless of income, except in Wisconsin.

In addition to the impact on coverage, repeal of the ACA could alter Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies and processes in every state. The ACA standardized and streamlined these processes to move to a modernized, technology-driven approach. Following several years of state efforts to implement these processes through major upgrades to state eligibility systems, 50 states currently have an online application for Medicaid, 41 states offer an online account for enrollees to manage their Medicaid coverage, 39 states can determine Medicaid eligibility decisions within 24 hours, and 42 states are processing automated renewals. Since Medicaid systems coordinate or are integrated with Marketplace systems in all states, changes to the Marketplaces would also affect Medicaid.

Lastly, the survey provides detail on states’ continued use of available options to expand access to coverage and further streamline enrollment and renewal processes and provides information on states’ use of premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid and CHIP.

This 15th annual survey, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey, conducted in the fall of 2016 with Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families, offers an in-depth profile of eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies in each state and can serve as a baseline for changes going forward. Reports from previous years can be found on KFF.org.

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2017: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Executive Summary

This 15th annual 50-state survey provides data on Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal and cost sharing policies as of January 2017, and identifies changes in these policies in the past year. (See Appendix Tables 1-21 for state data.) As discussion of repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), broader changes to Medicaid, and reauthorization of CHIP unfolds, this report documents the role Medicaid and CHIP play for low-income children and families and the evolution of these programs under the ACA. The findings offer an in-depth profile of eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies in each state as of January 2017, providing a baseline against which future policy changes may be measured.

Key Findings

Medicaid and CHIP are the central sources of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women, with 49 states covering children and 34 states covering pregnant women with incomes at or above 200% FPL as of January 2017 (Figure 1). CHIP plays a key role across states, covering children in separate CHIP programs in 36 states, funding coverage for some children in Medicaid in 49 states, and supporting coverage for pregnant women in 19 states. In 2016, several states took up options to expand access to coverage for children and pregnant women.

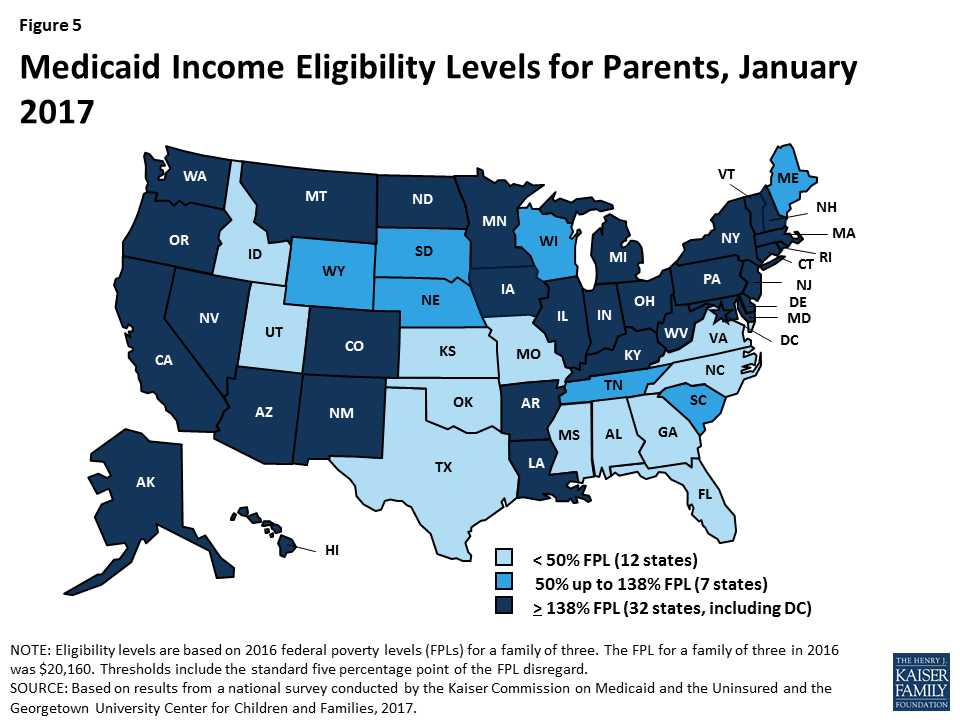

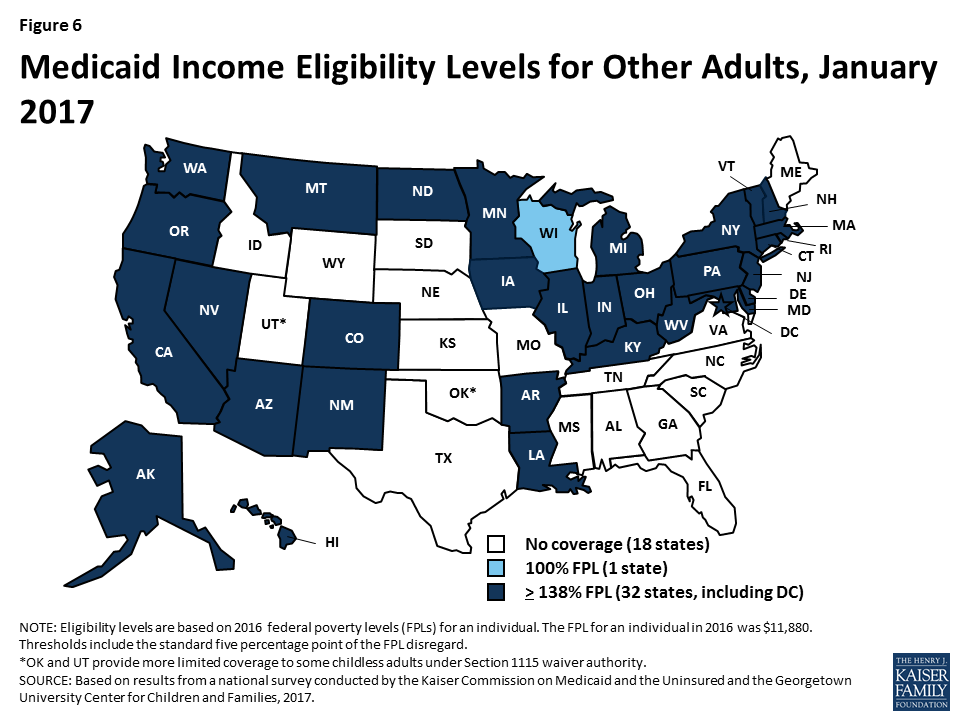

Medicaid’s role for low-income adults broadened under the ACA, with 32 states covering low-income parents and other adults with incomes up to 138% FPL ($16,394 for an individual or $27,820 for a family of three in 2016) under the Medicaid expansion as of January 2017. This count reflects Louisiana’s adoption of the expansion in 2016. In the 19 states that have not expanded, the median eligibility limit for parents is 44% FPL ($8,870 for a family of three as of 2016) and other adults are ineligible regardless of income, except in Wisconsin.

During 2016, states continued to upgrade and streamline Medicaid eligibility and enrollment systems and processes under the ACA, using federal funding available to support system development. As of January 2017, 50 states have an online Medicaid application, 41 states offer online accounts for enrollees to manage their coverage, 39 states make real-time Medicaid eligibility decisions, and 42 states process automated renewals. Moreover, Medicaid systems coordinate or are integrated with Marketplace systems in all states. In 12 of the states with a State-based Marketplace (SBM), there is one system that determines eligibility for Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. The remaining 39 states transfer data back and forth with the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), HealthCare.gov, to coordinate eligibility decisions.

Use of premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid and CHIP varies across states and groups. As of January 2017, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees and 25 states charge cost sharing for children in Medicaid or CHIP. In most cases, these charges are limited to children in CHIP, because CHIP covers children with higher family incomes than those in Medicaid and the program has different premium and cost sharing rules. Given the low incomes of adults covered by Medicaid, most states do not charge adults premiums, and cost sharing amounts for adults are generally nominal. Overall, 39 states charge parents cost sharing, and 23 of the 32 states that have expanded Medicaid charge cost sharing for expansion adults. Six states have received waivers to charge premiums or monthly contributions for adults that are not otherwise allowed under law.

Looking Ahead

This year’s findings build on results from previous years, documenting state policy choices and state implementation of ACA changes to Medicaid, including the expansion to low-income adults and the streamlining of enrollment and renewal processes. Together, these changes have led to increased Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, which has helped to reduce the nation’s uninsured rate to historic lows of 10% for the population under age 65 and 5% for children as of June 2016.1 As discussion of repeal of the ACA, broader changes to Medicaid, and reauthorization of CHIP unfolds, the findings provide a baseline of state policies as of January 2017, against which future policy changes can be measured. Together they suggest:

Given the significant role of Medicaid and CHIP for low-income families across states, changes to these programs could affect coverage for many of the nation’s low-income families. The findings show that Medicaid and CHIP are central sources of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women in all states. Reauthorization of CHIP will have particularly important implications for children and pregnant women given the role CHIP plays complementing Medicaid to support their coverage across states. Loss of CHIP funding could put this coverage at risk and would create funding gaps for states. The findings also show how Medicaid’s role for low-income parents and other adults has broadened in states that implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion. If the Medicaid expansion was eliminated under a repeal of the ACA, many low-income parents and other adults would lose eligibility and potentially become uninsured, depending on what other coverage options may be available. Moreover, broader changes to the financing structure of Medicaid, coupled with reductions in federal Medicaid funding, could affect coverage for all groups of enrollees.

The ACA included changes in Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies and processes in all states, which could be affected by a repeal of the ACA. Under the ACA, all states have implemented new standardized streamlined eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies, which have yielded modernized systems and processes that reduced paperwork for individuals and administrative burdens on states. Implementing these policies and processes has taken ongoing efforts by states since the ACA was enacted in 2010, with substantial investments of time and resources. It remains to be seen which of these policies or processes could be affected by a repeal of the ACA. However, reverting back to pre-ACA policies or implementing new policies would likely require major investments of time, staff, and resources. Moreover, changes to the Marketplaces could affect Medicaid eligibility systems and enrollment processes because the systems are interwoven in all states.

States are using available program options to expand access to coverage, further streamline enrollment and renewal processes, and charge premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid and CHIP. To date, states have taken up many available program options to expand coverage and further streamline enrollment and renewal processes, particularly for children and pregnant women. Most states also are using options to charge premiums and cost sharing to some Medicaid and CHIP enrollees. In most cases, states target premiums and above-nominal cost sharing to enrollees with relatively higher incomes. The program options available to states, states’ use of these options, and the role of waivers could be affected by a repeal of the ACA or broader efforts to restructure Medicaid.

Report: Introduction

This annual report presents Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal and cost sharing policies as of January 2017, and identifies changes in policies that occurred between January 2016 and 2017. As discussion around potential repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), broader changes to the financing and structure of Medicaid, and reauthorization of CHIP unfold, this report offers an in-depth profile of eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies in each state as of January 2017. This information may serve as a baseline against which future policy changes may be measured.

This report has documented state implementation of changes to Medicaid since the ACA was implemented in 2014, including the Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, changes to eligibility rules, and modernization and streamlining of enrollment and renewal processes. These changes have led to increases in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment, which rose by 17 million between Summer 2013 and October 2016,2 and helped reduce the nation’s uninsured rates to historic lows of 10% for the overall population under age 65 and 5% for children as of June 2016.3 This year’s survey finds continued state efforts to expand access to coverage for some groups and to implement the streamlined enrollment and renewal processes outlined in the ACA.

This report is based on a telephone survey of state Medicaid and CHIP program officials conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families during Fall 2016. It includes findings in three key areas: Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment and Renewal Processes, and Premiums and Cost Sharing. State-specific information is available in Appendix Tables 1 to 21 at the end of the report. This report includes policies for children, pregnant women, parents, and other adults under age 65; it does not include policies for groups covered through Medicaid eligibility pathways for seniors and individuals with disabilities.

Report: Medicaid And Chip Eligibility

Most income eligibility limits for Medicaid and CHIP are based percentages of the federal poverty level (FPL). As of 2016, the FPL was $20,160 for a family of three and $11,880 for an individual. The ACA established a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 133% FPL for children, pregnant women, and adults as of January 2014, and included a standard income disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level, which effectively raises this limit to 138% FPL. This expansion made many parents and other adults newly eligible for the program. Before the ACA, most states limited eligibility levels for parents to less than the poverty level and other adults generally were not eligible regardless of income. As enacted, the Medicaid expansion was to be implemented nationwide. However, the 2012 Supreme Court ruling on the ACA made the expansion to low-income adults optional. The minimum continues to apply nationwide for children and pregnant women, and, as a result of the minimum, 18 states transitioned coverage for some older children from separate CHIP programs to Medicaid during 2014.

The ACA also changed how financial eligibility is determined for non-disabled groups in Medicaid, including children, pregnant women, parents, and the new expansion adults, to be based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), as defined in the Internal Revenue Code. The ACA eliminated the use of income disregards and deductions other than the new standard disregard of five percentage points of the FPL and required states to convert their pre-ACA eligibility levels to MAGI-equivalent levels.

The findings below show eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults as of January 2017, and identify changes in eligibility that states made between January 2016 and 2017.

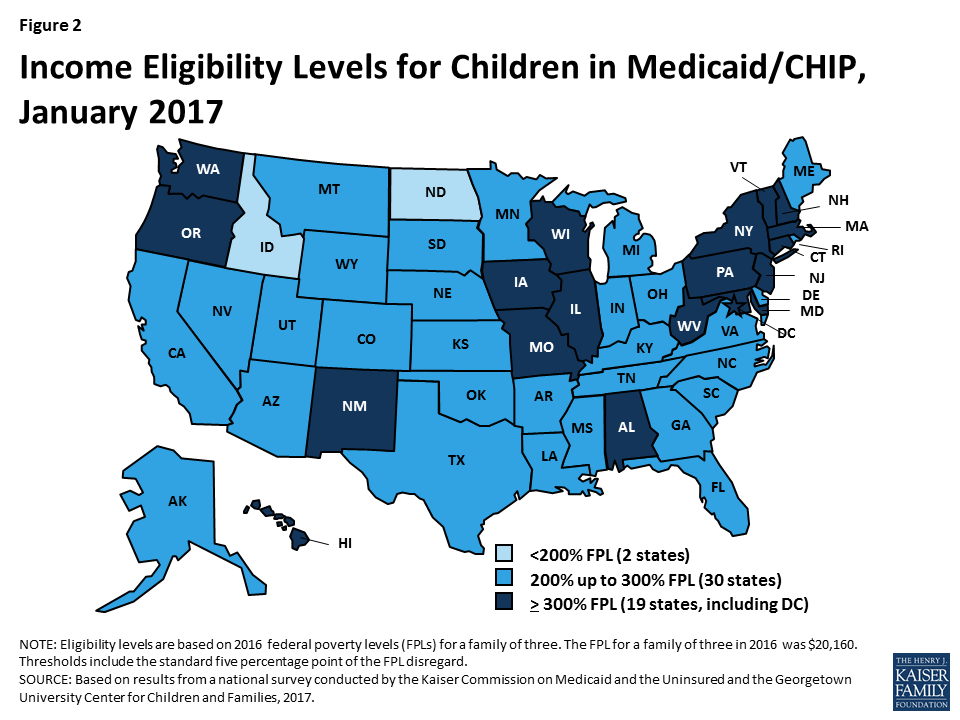

Children

As of January 2017, 49 states cover children with incomes up to at least 200% FPL through Medicaid and CHIP, including 19 states that cover children with incomes at or above 300% FPL (Figure 2). Only two states (Idaho and North Dakota) limit children’s Medicaid and CHIP eligibility to lower incomes. Across states, the upper Medicaid/CHIP eligibility limit for children ranges from 175% FPL in North Dakota to 405% FPL in New York. Consistent with the past several years, children’s Medicaid and CHIP eligibility remained largely stable during 2016, with the exception of Michigan expanding eligibility to children with incomes up to 400% FPL who were affected by the Flint water crisis.4 This stability reflects the ACA’s maintenance of effort provision, under which states must keep children’s eligibility levels at least as high as the levels they had in place when the law was enacted in 2010 until 2019.

CHIP plays a substantial role covering children across states. As of January 2017, 36 states operate separate CHIP programs, and CHIP funding covers some children in Medicaid in 49 states. As of January 2017, enrollment is open in all separate CHIP programs. Arizona reopened enrollment in its CHIP program in July 2016; it had been closed to enrollment since late 2009, just prior to enactment of the ACA.

Several states took up options to cover more children through Medicaid and CHIP in 2016.

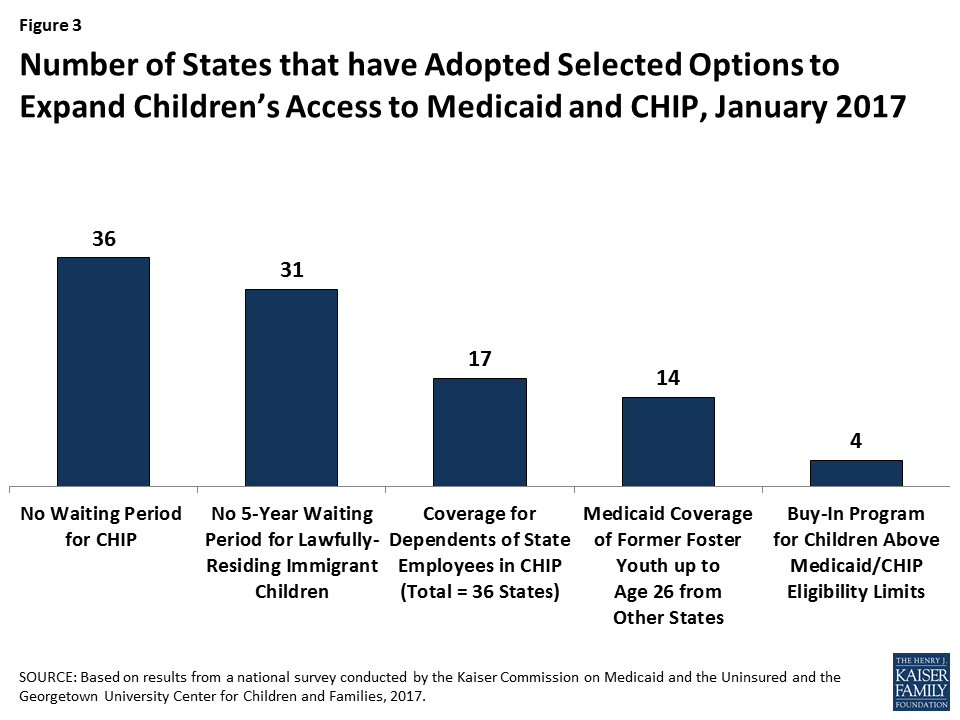

- Eliminating waiting periods for CHIP coverage. States can require children to be uninsured for up to 90 days before enrolling in CHIP. States have used these waiting periods as an approach to discourage families from dropping private insurance to enroll in the program. However, the number of states requiring a waiting period has declined over time, particularly after the ACA, since one of the ACA’s goals is to eliminate gaps in coverage. This decline continued in 2016, with Georgia and New York eliminating their waiting periods for CHIP. With these changes, as of January 2017, 36 states have no waiting period for CHIP coverage (Figure 3).

- Extending coverage to lawfully residing immigrant children. Longstanding rules require that lawfully present immigrants who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid or CHIP must wait five years from the time they receive a qualified immigration status before they may enroll. However, states have the option to eliminate this five-year waiting period for lawfully present immigrant children and pregnant women. In 2016, Florida and Utah took up this option for children. With these additions, as of January 2017, 31 states cover lawfully present immigrant children in Medicaid and/or CHIP without a five-year waiting period. In addition, six states (California, District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington) use state-only funds to cover income-eligible children who are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status. This count includes the statewide expansion of coverage for all income-eligible children in California in May 2016.

- Allowing dependents of state employees to enroll in CHIP. In January 2016, Tennessee became the 17th state to adopt an option available to cover certain dependents of state employees in CHIP. Under this option, states can give part-time workers and other state employees who lack access to affordable dependent coverage in the state employee health plan the option to enroll their children in CHIP.

- Expanding coverage for former foster youth. Under the ACA, youth who were formerly in foster care in the state are eligible for Medicaid until age 26. This provision mirrors the ACA change that allowed young adults to remain on their parents’ health plan until age 26. However, extending Medicaid coverage to former foster youth from other states was a state option. With the addition of Utah during 2016, 14 states had taken up this option. In November 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released regulations, which clarified that states could not cover former foster youth from other states through a state option but could do so under Section 1115 waiver authority. CMS indicated in guidance that it will work with the 14 states that have adopted this coverage to transition it to waiver authority. 5

Four states have maintained programs that allow families above the upper income eligibility limit to buy into Medicaid or CHIP coverage for their children as of January 2017.6 The number of states offering buy-in programs declined from a peak of 15 in 2011 to 4 as of January 2017. An increasing number of states eliminated these programs in recent years, because many families above Medicaid and CHIP income limits gained new coverage options through the Marketplaces.

Pregnant Women and Family Planning Expansion Programs

All states cover pregnant women with incomes up to at least 138% FPL, and 34 states cover pregnant women with incomes at or above 200% FPL as of January 2017 (Figure 4). Across states, eligibility for pregnant women ranges from 138% FPL in Idaho and South Dakota to 380% FPL in Iowa. Five states cover pregnant women through CHIP, and 16 states use CHIP funding to provide coverage through the unborn child option, under which states cover income-eligible pregnant women regardless of immigration status. Just under half of states (23 states) have taken up the option to cover lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women without a five-year waiting period. In addition, the District of Columbia, New Jersey, and New York use state-only funds to cover income-eligible pregnant women who are not otherwise eligible due to immigration status. During 2016, Michigan expanded Medicaid eligibility to pregnant women with incomes up to 400% FPL who were affected by the Flint water crisis. Missouri created a separate CHIP program for pregnant women with incomes between 201% and 305% FPL and adopted the unborn child option. Outside of these changes, Medicaid and CHIP coverage for pregnant women remained stable in 2016.

As of January 2017, over half of the states (29) have expanded access to family planning services through a waiver or the state option created by the ACA. States must provide family planning services as a covered benefit to Medicaid enrollees. Historically, some states also used waivers to provide family planning services to women or men who did not qualify for full Medicaid coverage. The ACA made a new option available for states to expand family planning services coverage. As of January 2017, 29 states have family planning expansion programs through a waiver or the state plan option.

Parents and Adults

With Louisiana’s adoption of the Medicaid expansion during 2016, 32 states cover parents and other adults with incomes at up to at least 138% FPL as of January 2017 (Figures 5 and 6). Alaska, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia also extend coverage to parents and/or other adults with incomes above 138% FPL. In addition, two states, Minnesota and New York, have used the ACA Basic Health Program option to cover adults with incomes between 138% and 200% FPL, rather than having individuals in this income range access coverage through the Marketplace.

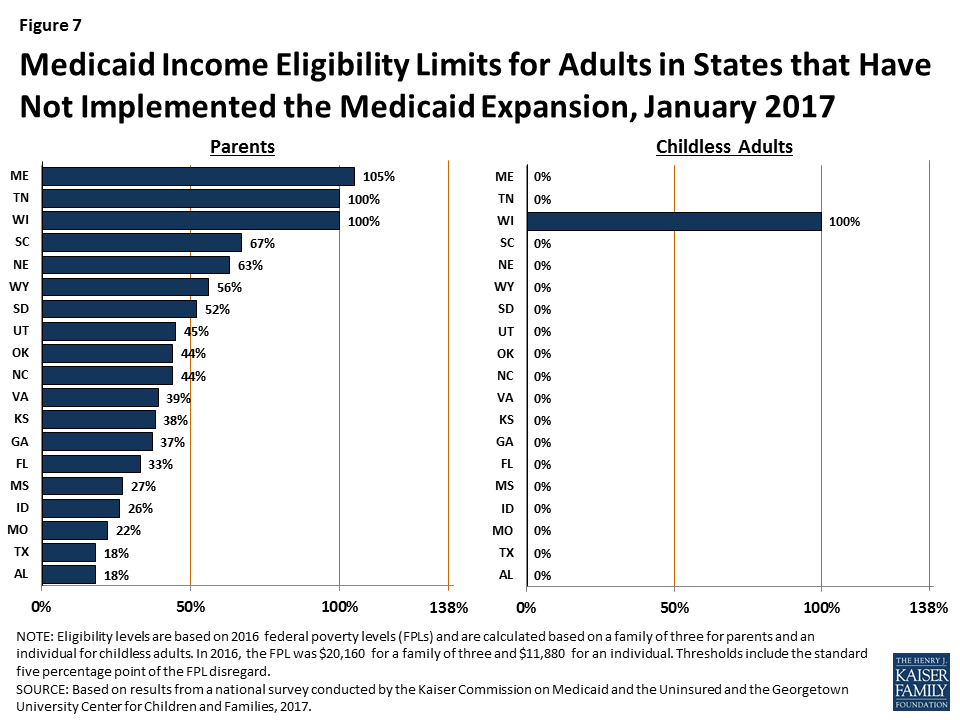

In the 19 states that have not expanded Medicaid, the median eligibility level for parents is 44% FPL, and other adults remain ineligible regardless of income, except in Wisconsin (Figure 7). Among the 19 non-expansion states, parent eligibility levels range from 18% FPL in Alabama to 105% FPL in Maine. Only 3 states—Maine, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—cover parents at or above 100% FPL, while 12 states limit parent eligibility to less than half the poverty level ($10,080 for a family of three as of 2016). Wisconsin is the only non-expansion state that provides full Medicaid coverage to other non-disabled adults, although its 100% FPL eligibility limit remains below the ACA expansion level and it does not receive the enhanced federal match for this coverage. While this study reports eligibility based on a percentage of the FPL, 13 non-expansion states base eligibility for parents on dollar thresholds (which have been converted to an FPL equivalent in this report). Twelve of these states do not routinely update the dollar standards, resulting in eligibility levels that erode over time relative to the cost of living. In non-expansion states, 2.6 million poor adults fall into a coverage gap.7 These adults earn too much to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to qualify for subsidies for Marketplace coverage, which are available only to those with income at or above 100% of FPL.

Report: Medicaid And Chip Enrollment And Renewal Processes

The ACA standardized many streamlined enrollment and renewal procedures that states pioneered for children in the decades following the passage of CHIP in 1997. It also provided federal funding to support state upgrades to Medicaid eligibility systems, since many states had outdated systems that impeded updates to enrollment and renewal processes. Since the ACA was enacted, states have invested significant time and resources to upgrade or build new eligibility systems, using available federal funding. The modernized technology of these new systems has served as the cornerstone for states to implement the streamlined enrollment and renewal processes in the ACA. Under these processes, states are to use available electronic data to verify eligibility criteria at application and renewal; to provide individuals multiple methods to apply, including online, by phone, via mail, or in-person; to coordinate eligibility decisions with Marketplaces; and to renew Medicaid coverage every 12 months. Implementation of these processes has varied across states, in part reflecting different starting places before the ACA. However, as of January 2017, nearly all states have moved closer to the processes outlined in the ACA, with continued work occurring during 2016.

As a result of these efforts, the Medicaid enrollment and renewal experience has moved from a paper-based, manual process that could take days and weeks in some states to a modernized, technology-driven approach that can happen in real-time in a growing number of states. This shift has reduced burdens on individuals and states and led to shifting roles for eligibility workers, with some states scaling back or redirecting staff resources.

The findings below present the status of state systems and processes as of January 2017, and identify changes made to systems and processes during 2016. Unless otherwise indicated, the findings are for Medicaid systems and processes for children, pregnant women, parents and expansion adults. Many of the system upgrades and streamlined processes focused on these groups, and some separate eligibility rules and processes apply to seniors and individuals with disabilities. However, as indicated in the findings below, an increasing number of states are capitalizing on the federal funding available for system upgrades to expand improved systems to include all Medicaid groups and non-health programs.

Eligibility Systems

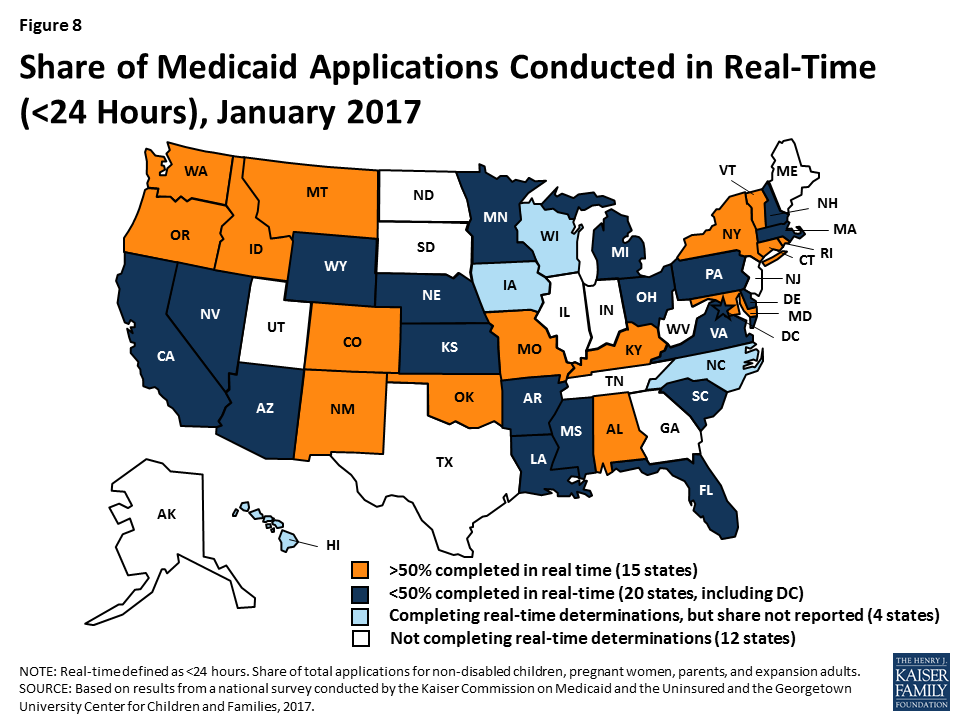

As of January 2017, 39 states can make Medicaid eligibility determinations in real-time (defined as within 24 hours). One of the notable features of upgraded eligibility systems is the ability to check against other electronic data sources in real-time or overnight to provide timely eligibility decisions. During 2016, Idaho and New Mexico began determining eligibility in real-time, and several more states anticipate reaching this milestone in early 2017. At least 50% of applications receive a real-time determination in 15 of the 35 states that were able to report this data (Figure 8), including 9 states that report over 75% of applications receive a real-time decision.

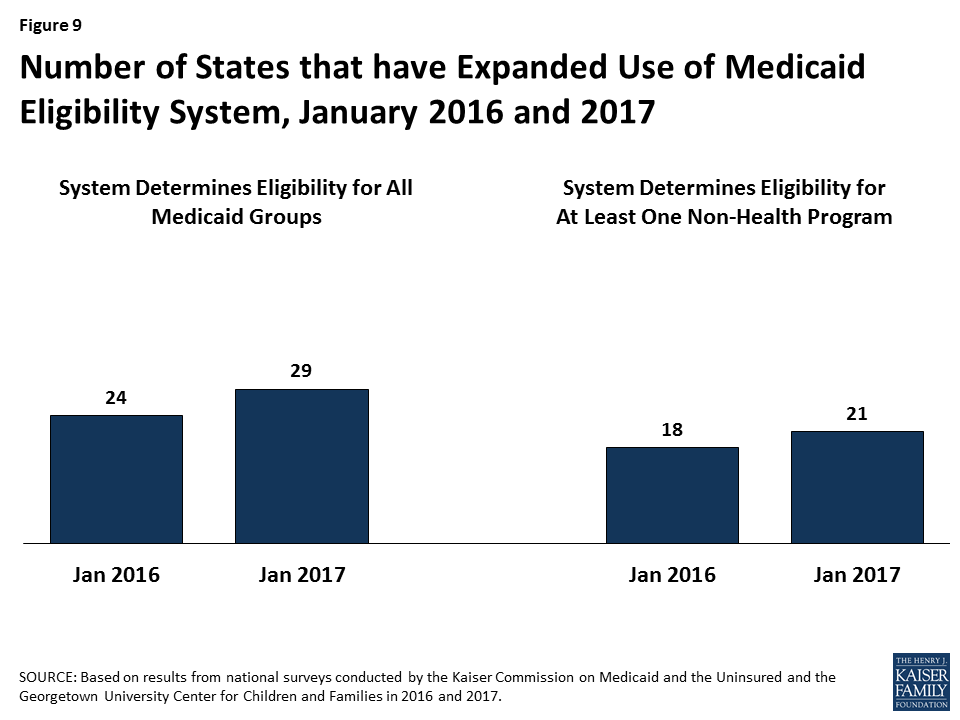

States are expanding improved Medicaid eligibility systems to include eligibility decisions for seniors and individuals with disabilities as well as non-health programs. Prior to the ACA, most states used one system to determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups as well as some non-health programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Given the complexity of system upgrades, many states initially built their new systems to determine eligibility for the non-disabled groups affected by the ACA streamlining changes. As new systems were launched for these groups, states continued to use their old systems to determine eligibility for seniors and individuals with disabilities as well as non-health programs. As states finished initial implementation of new systems, a number began expanding them to include other groups and programs, using the ongoing federal funding available for system upgrades. During 2016, the number of states with systems that determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups grew from 24 to 29 (Figure 9). The number of states that include at least one non-health program in their Medicaid system increased from 18 to 21. In addition, several states added additional non-health programs to their systems during 2016. Thirty states plan to expand their systems to include seniors and individuals with disabilities and/or additional non-health programs in 2017 and beyond.

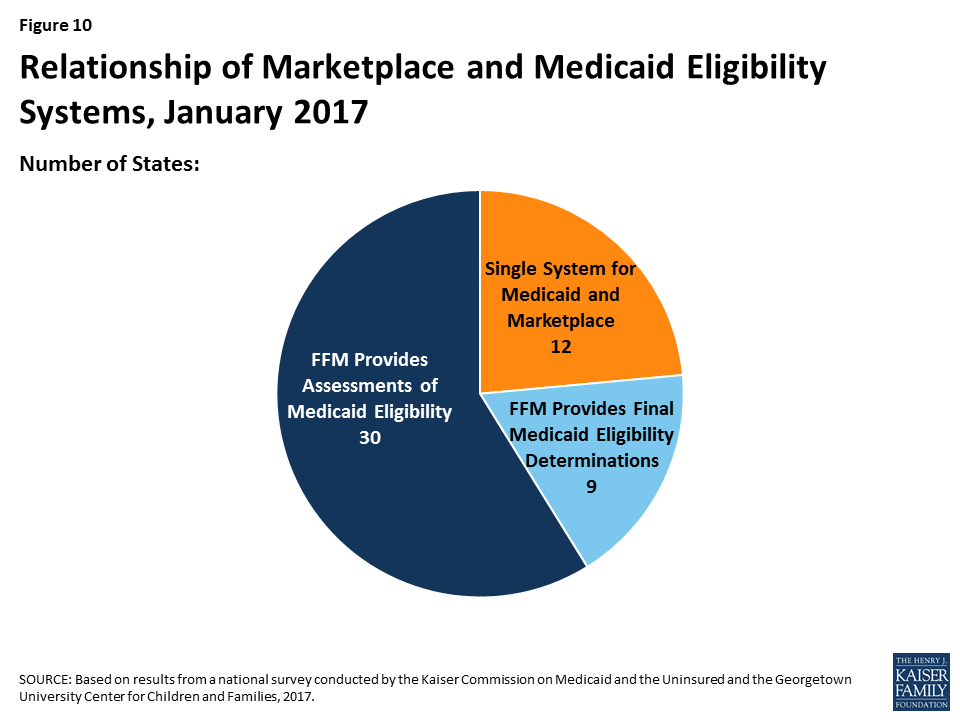

Medicaid eligibility systems are integrated with or connected to Marketplace systems in all states. In 12 of the states with a State-based Marketplace (SBM), there is one system that determines eligibility for both Medicaid and Marketplace coverage (Figure 10). The remaining 39 states coordinate with the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), HealthCare.gov. This count reflects the dismantling of Kentucky’s SBM enrollment system, kynect, during 2016. States coordinating with the FFM must electronically transfer data back and forth with the FFM to coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace eligibility decisions. Nine of these states have authorized the FFM to make final Medicaid eligibility determinations based on the eligibility rules established by the state, enabling the states to enroll individuals in Medicaid after receiving the account transfer. During 2016, Louisiana began on relying final determinations to facilitate enrollment under its newly implemented Medicaid expansion. In the remaining 30 states, the FFM assesses Medicaid eligibility based on the state eligibility rules. In these states, after receiving the account transfer from the FFM, the Medicaid agency may check state data sources or request additional documentation before completing the eligibility determination. When the ACA was first implemented, there were significant problems with account transfers that contributed to delays in Medicaid enrollment. As of January 2017, only 6 states report ongoing, regular delays or difficulties with transfers, down from 20 as of January 2016.

Applications, Online Accounts, and Mobile Access

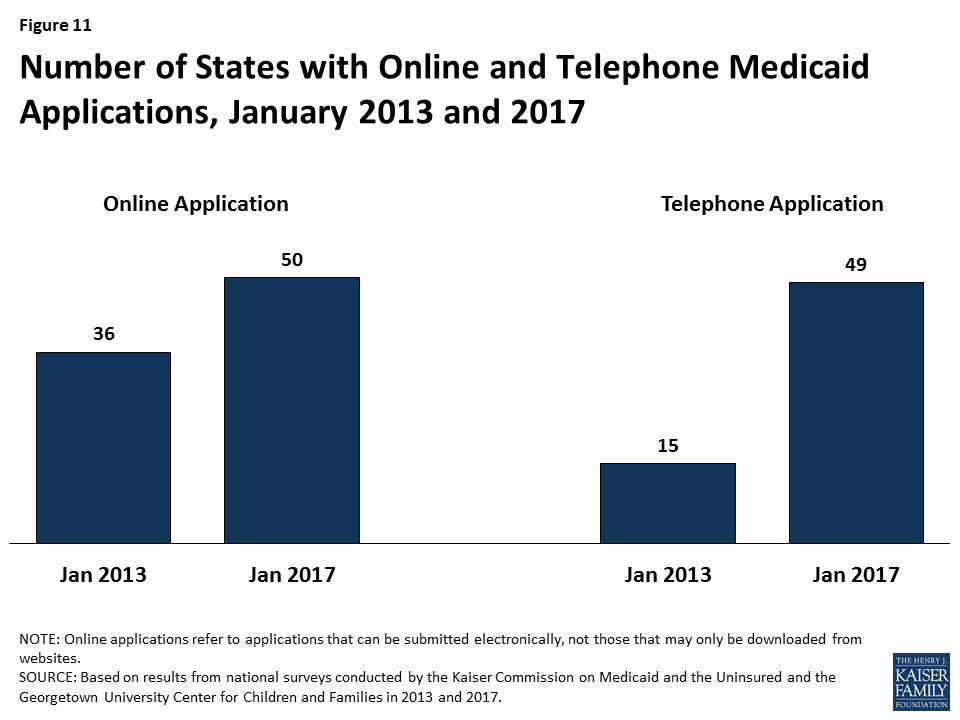

Individuals can apply for Medicaid online and by phone in nearly all states as of January 2017. Under the ACA, states must provide multiple methods for individuals to apply for health coverage, including online, by phone, by mail, and in person. In 2013, prior to ACA implementation, 36 states had an online Medicaid application and individuals could apply for Medicaid by phone in 15 states. As of January 2017, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in all states except Tennessee, and individuals can apply by phone in all states except Tennessee and Minnesota (Figure 11). At least 50% of Medicaid applications are submitted online in 18 of the 45 states that were able to report the share of applications received online.

The features and functions of online applications vary across states (Figure 12). In all 50 states with an online application, applicants can start, stop, and return to finish the application at a later time. Applicants can upload electronic copies of documents with their application, if needed, in 33 states. With the addition of Ohio in 2016, all Medicaid groups, including seniors and people with disabilities, can apply through the online application in 30 states. Individuals can also apply for a non-health program, such as SNAP or TANF, using the online application in half of states. This count includes Kentucky, which launched an online multi-benefit application in 2016.

Just over half of the states (26 states) have a web portal or secure login that enables consumer assisters to submit applications on behalf of consumers they help. Massachusetts and New Jersey added a portal for consumer assisters in 2016. In some states, the assister portals have additional functions or features that support the work of assisters, such as the ability to check a renewal date. These types of tools may help reduce workloads on state administrative staff, for example, if assisters are able to update addresses and other information. This functionality may also allow the state to track, monitor and report the work of assisters.

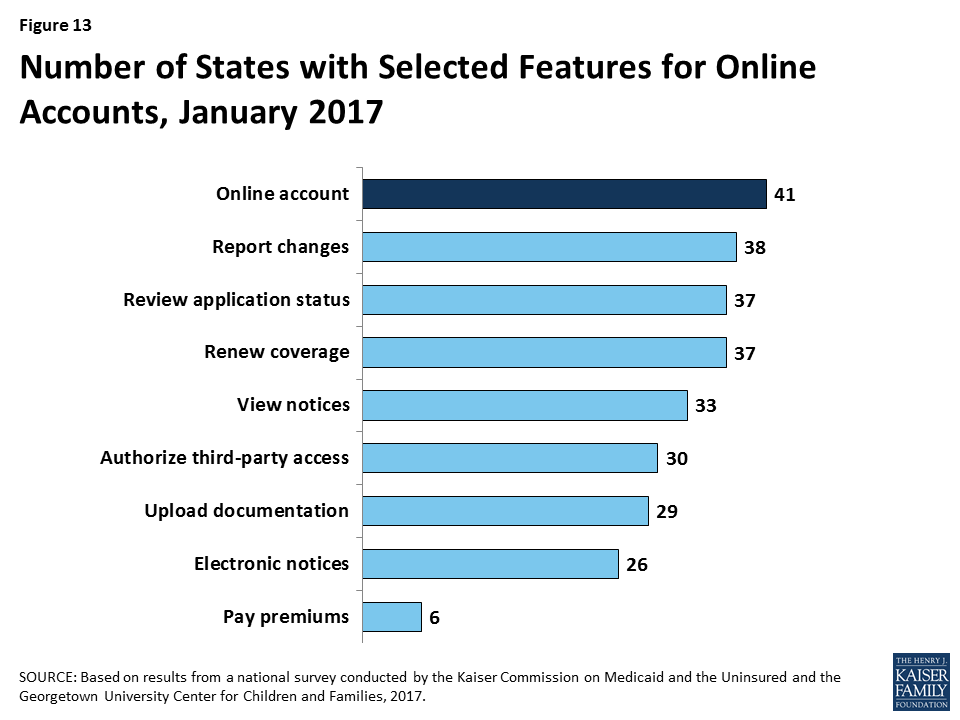

In 41 states, individuals can create an online account to manage their Medicaid coverage after enrollment (Figure 13). Most states provide a wide array of functions through online accounts and states have expanded functionality over time, with several states adding functions to their accounts in 2016. Most of these accounts allow enrollees to report changes, review the status of their application, to renew coverage, and to view notices. Smaller numbers allow enrollees to go paperless and receive electronic notices or to pay premiums. Online accounts create administrative efficiencies by reducing mailing costs, call volume, and manual processing of updates such as an address change. They also provide enrollees increased autonomy to manage and monitor their coverage.

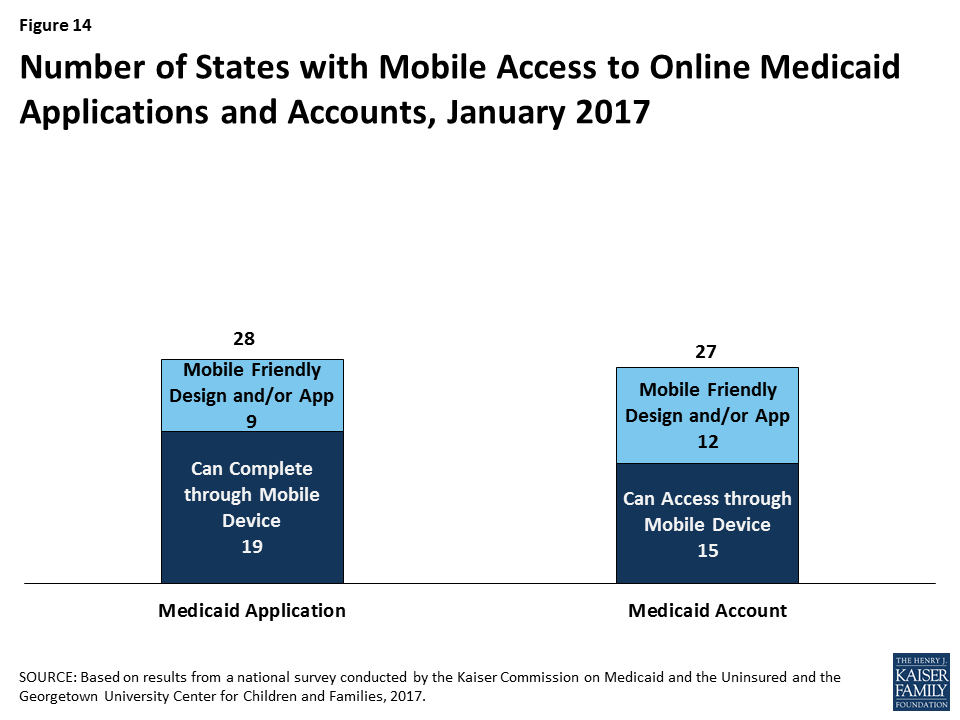

States have begun to make online applications and accounts accessible through mobile devices, such as phones or tablets. As of January 2017, individuals in 28 states can complete and submit the online Medicaid application through a mobile device. Nine of these states have designed a mobile-friendly version of the application and/or developed a mobile “app” for individuals to apply through a mobile device (Figure 14). Similarly, in 27 states, enrollees can access the online Medicaid account through a mobile device. In 12 of these states, there is a mobile-friendly version of the account and/or the state has created an “app” for enrollees to access the account through a mobile device. A number of states indicate that they plan to enhance mobile access to online applications and accounts in 2017 or beyond.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

One major shift under the ACA has been for states to rely on data from reliable electronic data sources rather than paper documentation to verify eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP. This change provides for a faster, more efficient eligibility determination process that reduces paperwork requirements for individuals and eases administrative burden on states, although it required significant upfront work by states to establish system connections to other data sources.

All states verify income eligibility, as well as citizenship and qualified immigration status of applicants, as required in Medicaid and CHIP. States must verify citizenship or qualified immigration status in advance of enrollment. Individuals who attest to a qualified status but who cannot have their eligibility confirmed electronically must be given a reasonable amount of time to provide adequate documentation. Nearly all states (44 states) verify income prior to enrollment, while 7 states complete the verification after enrollment. Verification of other eligibility criteria, such as age/date of birth, state residency, and household size vary across states and criteria, reflecting state options to verify this information before or after enrollment or to rely on self-attestation of information. If a state relies on self-attestation, it must verify information if it has any data on file that conflicts with the self-attestation.

All states access income and other information from the Social Security Administration, and many states also use state wage and unemployment data to verify eligibility criteria. As of January 2017, more than two-thirds of states get income and other information through the federal data hub, which was established by the ACA. The data hub enables states to access information from multiple federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and a commercial database that provides earnings reported by large employers. States not using the federal hub rely on direct links to SSA and DHS databases that existed before the ACA. In addition, most states utilize state wage and unemployment data for income and other information. Fewer states rely on federal or state tax data.

Renewal Processes

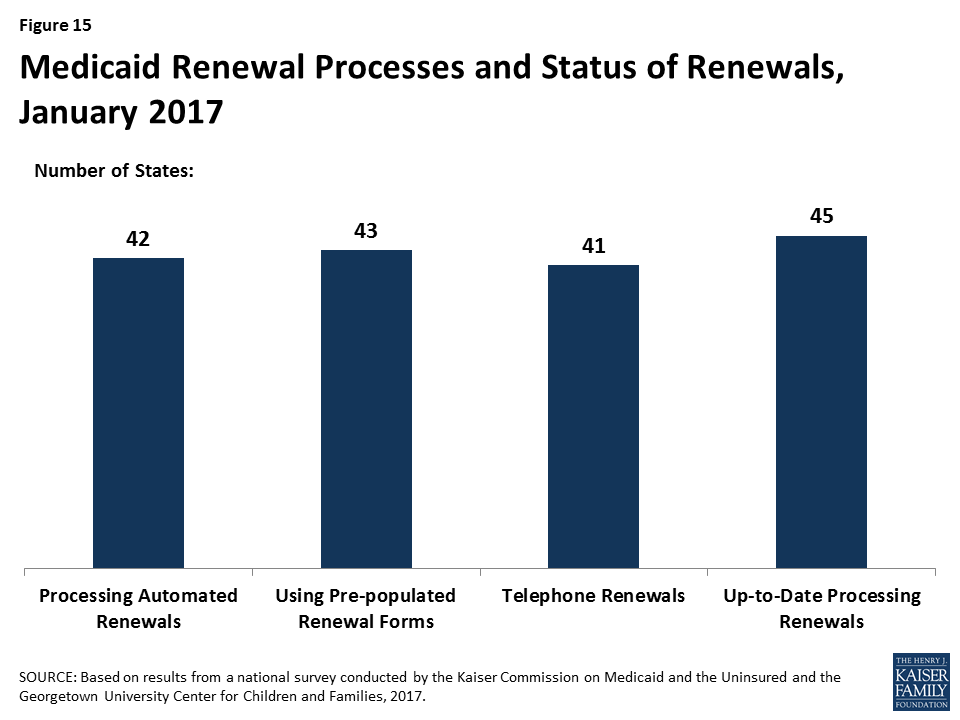

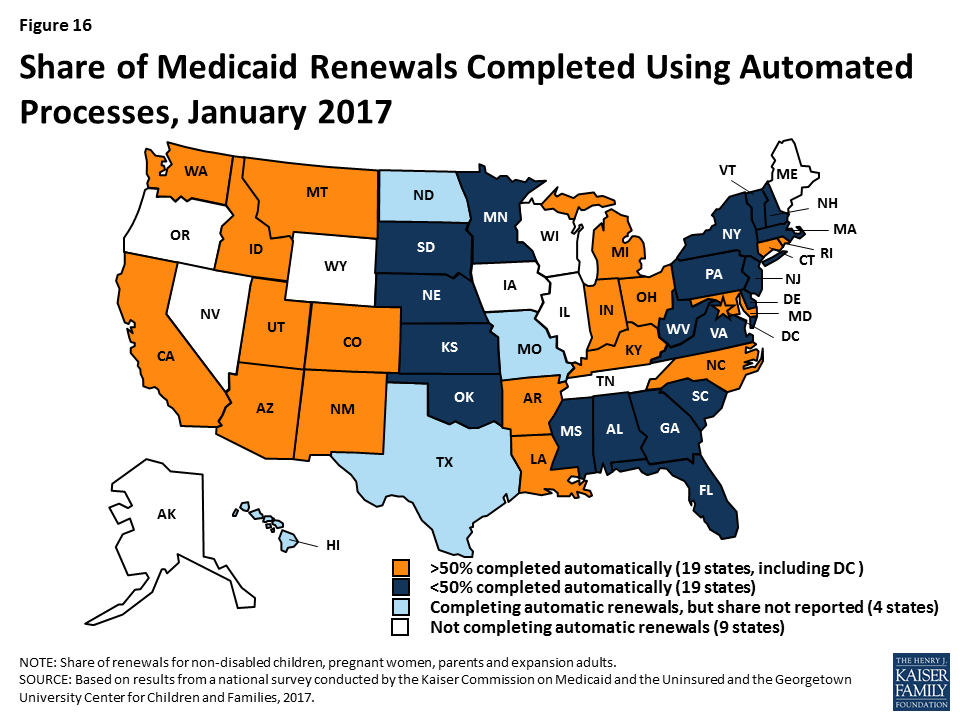

As of January 2017, 42 states were processing automated Medicaid renewals (Figure 15). This count includes five states that newly implemented automated renewal processes during 2016. Similar to data-driven enrollment, under the ACA, states are to use electronic data when available to renew coverage without requiring an individual to fill out a renewal form or provide documentation. This approach minimizes paperwork for individuals and reduces workloads for states. Among the 38 states able to report the share of renewals that are completed through automatic processes, 19 states report that more than 50% of renewals are automated (Figure 16), including 10 states with automatic renewal rates above 75%. In comparison, only 3 states reported that over 75% of renewals were automated as of January 2016.

If a renewal cannot be completed based on available data, states are expected to send a pre-populated notice or renewal form to the enrollee and to allow individuals to renew by phone. Between January 2016 and 2017, the number of states able to send pre-populated renewal forms or notices increased from 41 to 43. In 13 states, the forms are populated using updated sources of data from electronic data matches. With the addition of Arkansas and Texas during 2016, individuals can renew Medicaid coverage by phone in 41 states as of January 2017.

Most states are up-to-date on renewals as of January 2017. Six states report ongoing delays in processing renewals, most often citing system challenges or staff capacity as contributing factors.

Facilitated Enrollment and Renewal Options

States can take up additional options to streamline enrollment and renewal beyond the processes standardized by the ACA. Most of these options have been available for many years prior to the ACA, but some were made newly available by the ACA. States’ use of these options may decline over time as states are able to achieve more real-time determinations and automated renewals through their standard processes. However, the options may remain useful for providing access to coverage for individuals who cannot have their eligibility verified in real-time. As of January 2017, states use a range of these options (Figure 17):

- Presumptive eligibility. Presumptive eligibility is a longstanding option in Medicaid and CHIP, which allows states to authorize qualified entities—such as community health centers or schools—to make a temporary eligibility determination to expedite access to care for children and pregnant women while the full application is processed. The ACA broadened the use of presumptive eligibility in two ways. First, it allows states that provide presumptive eligibility for children or pregnant women to extend the policy to parents, adults, and other groups. In 2016, two states (Missouri and Wyoming) expanded their use of presumptive eligibility. As of January 2017, over half of states use presumptive eligibility for children or pregnant women, while smaller numbers have adopted this policy for other groups. Second, the ACA gives hospitals nationwide the authority to determine eligibility presumptively for all non-disabled individuals under age 65. With the addition of Tennessee during 2016, hospital-based presumptive eligibility has been implemented in 46 states of as January 2017; 38 states report that hospitals are submitting applications through this process.

- Express Lane Eligibility. Express Lane Eligibility (ELE) is another longstanding option that allows states to enroll or renew children in Medicaid or CHIP based on findings from other programs, like SNAP. As of January 2017, seven states (Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, New York, South Carolina, and South Dakota) enroll children in Medicaid through ELE, while three states (Colorado, Iowa, and Pennsylvania) do so in CHIP. Georgia ended its use of ELE for children in 2016. New York has a waiver to use ELE to enroll parents. Six states use ELE to renew children’s Medicaid coverage (Alabama, Louisiana, Massachusetts, New York, South Carolina, and South Dakota), while two states (Massachusetts and Pennsylvania) do so in CHIP. Massachusetts also uses ELE to renew parents and expansion adults in Medicaid under Section 1115 waiver authority.

- 12-month continuous eligibility. States are expected to re-determine eligibility every 12 months. During this 12-month period, enrollees are required to report changes and will lose coverage if these changes make them ineligible. However, states have an option to provide 12-month continuous eligibility to children, which enables them to provide more stable coverage by disregarding changes in income until renewal. Continuous eligibility promotes retention and reduces the number of people moving on and off of coverage due to small changes in income, which decreases administrative costs. It also improves states’ ability to monitor quality of care given that many quality measures require at least 12 months of continuous enrollment. States can adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for children as an option, but must obtain Section 1115 waiver approval to provide it to parents and other adults. The number of states that have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility remained stable in 2016. As of January 2017, 24 states provide continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid, 26 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs use it in CHIP, and Montana and New York provide it to parents and other adults under waiver authority.

Report: Premiums And Cost Sharing

States have options to charge premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid up to maximum allowable charges under federal rules that vary by income and group (Box 1).8 These rules establish parameters for premiums and cost sharing given that Medicaid and CHIP enrollees have limited ability to pay out-of-pocket costs due to their modest incomes and a large body of research that shows that premiums and cost sharing can impede access to coverage and care for low-income families.9

Box 1: Medicaid and CHIP Premium and Cost Sharing Rules

Premiums in Medicaid. States may charge premiums for Medicaid enrollees with incomes above 150%, including children and adults. Medicaid enrollees with incomes below 150% FPL may not be charged premiums.

Cost Sharing in Medicaid. States may charge cost sharing in Medicaid, but allowable charges vary by income (see Table 1). Cost sharing cannot be charged for emergency, family planning, pregnancy-related services in Medicaid, preventive services for children, or for preventive services defined as essential health benefits in Alternative Benefit Plans in Medicaid. In addition, children enrolled through mandatory eligibility categories generally cannot be charged cost-sharing. The federal minimum eligibility standard for children is 133% FPL, although some states have higher minimum standards for children.

Limit on Out-of-Pocket Costs. Overall, premium and cost sharing amounts for family members enrolled in Medicaid may not exceed 5% of household income. This 5% cap is applied on a monthly or quarterly basis.

Premiums and Cost Sharing in CHIP. States have somewhat greater flexibility to charge premiums and cost sharing for children covered by CHIP, although there remain limits on the amounts that can be charged, including an overall cap of 5% of household income.

| Table 1: Maximum Allowable Cost Sharing Amounts in Medicaid by Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100% – 150% FPL | >150% FPL | |

| Outpatient Services | $4 | 10% of state cost | 20% of state cost |

| Non-Emergency use of ER | $8 | $8 | No limit (subject to overall 5% of household income limit) |

| Prescription Drugs | |||

| Preferred | $4 | $4 | $4 |

| Non-Preferred | $8 | $8 | 20% of state cost |

| Inpatient Services | $75 per stay | 10% of state cost | 20% of state cost |

| Notes: Some groups and services are exempt from cost sharing, including children enrolled in Medicaid through mandatory eligibility pathways, emergency services, family planning services, pregnancy related services, and preventive services for children. Maximum allowable amounts are as of FY2014. Beginning October 1, 2015, maximum allowable amounts increase annually by the percentage increase in the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). | |||

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Children

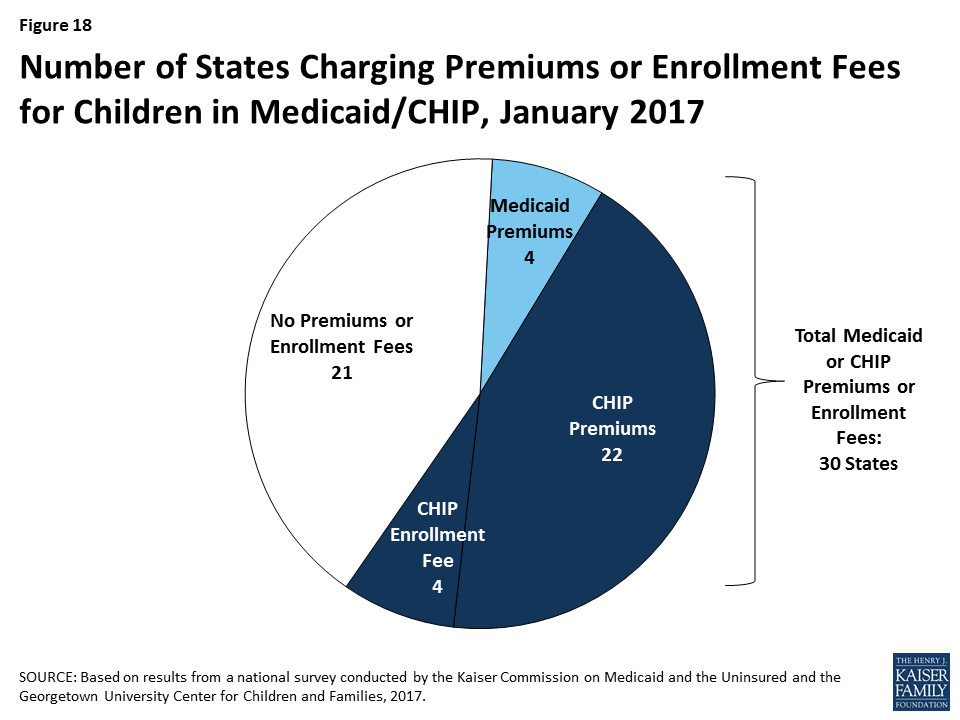

As of January 2017, 30 states charge premiums or enrollment fees for children in Medicaid or CHIP. Overall, 26 states charge monthly or quarterly premiums (4 in Medicaid and 22 in CHIP), and 4 states charge annual enrollment fees for CHIP (Figure 18). A larger number of CHIP programs have premiums and enrollment fees compared to Medicaid because the program covers children with relatively higher incomes and has different premium rules. In 22 of the 30 states charging premiums or enrollment fees, these charges begin for children in families with incomes at 150% FPL or higher, including 8 states that begin premiums at or above 200% FPL. Premium amounts vary across states, and most states scale the amounts by income. As part of the ACA protections for children’s coverage that extend through 2019, states may only increase premiums for cost-of-living adjustments or if the state had a routine premium adjustment approved prior to the enactment of the ACA. During 2016, there were no changes to premiums and enrollment fees for children outside of a routine adjustment.

State policies for non-payment of premiums vary. Among the 26 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in Medicaid or CHIP, 21 provide a 60-day or longer grace period before cancelling coverage for non-payment. This count includes the 4 states that charge premiums in Medicaid, which must provide a minimum 60-day grace period and cannot require enrollees to repay outstanding premiums as a condition of re-enrollment. It also includes 17 states that charge premiums in separate CHIP programs. In contrast to Medicaid, CHIP programs must provide a minimum 30-day grace period and may impose up to a 90-day “lock-out period,” during which a child is not allowed to re-enroll. Among the 22 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in CHIP, 4 limit the grace period to the minimum 30 days and 15 have a lock-out period for children disenrolled due to non-payment. Arizona reduced its lock-out period from three to two months when it reopened CHIP enrollment in 2016. Overall, 17 of the 26 states that charge monthly or quarterly premiums in Medicaid or CHIP require families to reapply for coverage before re-enrolling, subject to some exceptions. Consistent with Medicaid rules, the four states that charge premiums in Medicaid provide retroactive coverage. In addition, eight of the states that charge premiums in separate CHIP programs allow for retroactive reinstatement of coverage if outstanding premiums are paid.

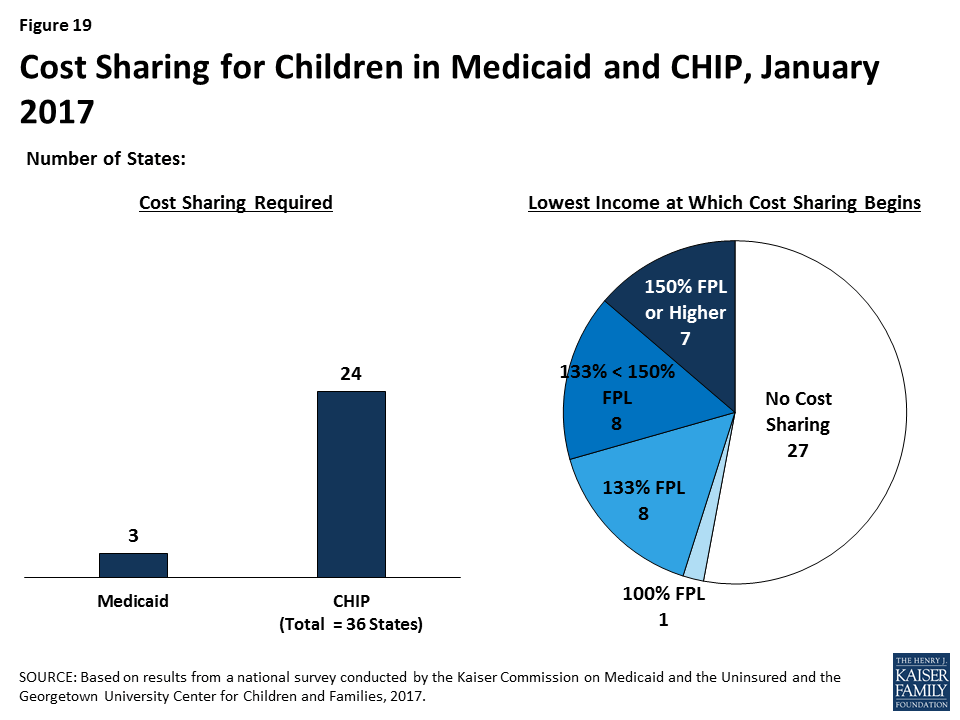

As of January 2017, 3 states charge cost sharing for children in Medicaid, while 24 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs do so (Figure 19). Consistent with federal rules, cost sharing does not apply to children below 133% FPL in all of these states, except Tennessee, which has a waiver to begin cost sharing at 100% FPL. In 16 states, cost sharing begins between 133% and 150% FPL, while 7 states begin cost sharing at 150% FPL or higher. Cost sharing charges vary by service. For example, for a child with family income at 201% FPL, 20 states charge cost sharing for a physician visit, 12 charge for an emergency room visit, 18 charge for non-emergency use of the emergency room, 15 charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 19 charge for prescription drugs, although, in some cases, charges only apply to brand name or non-preferred brand name drugs.

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Parents and Other Adults

Because eligibility levels for parents and other adults are much lower than for children, in most states, these groups are not charged premiums. However, six states (Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) have received waivers to charge premiums or monthly contributions for adults that are not otherwise allowed under law. Arizona received this waiver approval during 2016. In addition, during 2016, Arkansas received approval to amend its existing waiver, which included changing from monthly income-based contributions to health savings accounts in lieu of point-of-service cost sharing to monthly premiums for individuals with incomes above 100% FPL.

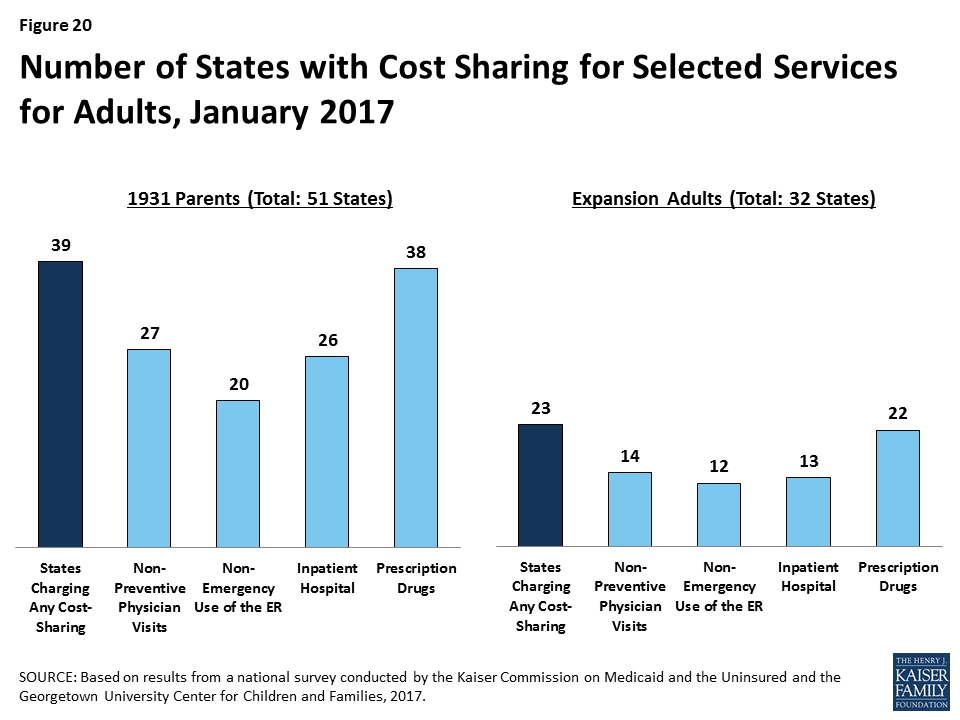

Among adults, 39 states charge parents cost sharing in Medicaid and 23 of the 32 states that have expanded Medicaid charge cost sharing for expansion adults. These counts reflect the elimination of copayments for parents and other adults in Oregon during 2016. Wisconsin, which is the only non-expansion state to cover other adults, also charges cost sharing but is not included the count for expansion adults. In most of the states that charge cost sharing for parents and/or expansion adults, cost sharing is required of all enrollees regardless of income. However, cost sharing amounts for adults are generally nominal, reflecting their low incomes. Cost sharing charges vary by service (Figure 20). Cost sharing for parents and expansion adults remained largely stable during 2016, aside from changes in a few states. Specifically, Oregon eliminated cost sharing for parents and expansion adults, Arizona and Montana increased cost sharing amounts for some services, and Iowa decreased the income at which cost sharing begins for expansion adults.

Report: Looking Ahead

The findings of this 15th annual report illustrate the central role that Medicaid and CHIP play in covering low-income children and families today. They also show how the ACA expanded Medicaid’s role for low-income adults and led to modernization and streamlining of eligibility systems and enrollment processes. As debate over the future of the ACA, potential broader changes to Medicaid, and CHIP reauthorization unfold, these findings provide a baseline against which future policy changes may be measured. Looking ahead, these findings suggest:

Given the significant role of Medicaid and CHIP across states, changes to these programs could affect coverage for many of the nation’s low-income families. As the findings illustrate, Medicaid and CHIP serve as the base of coverage for low-income children and pregnant women across all states. The findings also show how Medicaid’s role for low-income adults has expanded in the 32 states, including DC, that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion. Since the ACA was enacted through October 2016, net Medicaid and CHIP enrollment has grown by over 17 million people, increasing total enrollment to over 74 million enrollees.10 These enrollment gains have helped to reduce the nation’s uninsured rate to a record low of 10% in for the overall population under age 65, and to bring the children’s uninsured rate to 5% as of June 2016.11 As such, changes to Medicaid or CHIP would affect many low-income families. The outcome of debate around reauthorization of CHIP will have particularly important implications children and pregnant women given the key role CHIP plays complementing Medicaid to support their coverage across states. Loss of CHIP funding could put this coverage at risk and would create funding gaps for states. If the Medicaid expansion was eliminated under a repeal of the ACA, many low-income parents and other adults would lose eligibility and potentially become uninsured, depending on what other coverage options may be available. Moreover, broader changes to the financing structure of Medicaid, coupled with reductions in federal Medicaid funding, could affect coverage for all groups of enrollees.

The ACA included changes in Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies and processes in all states, which could potentially be affected by a repeal of the ACA. The ACA established new standards for eligibility, enrollment, and renewal processes that accelerated state efforts to modernize and streamline their systems and processes to utilize electronic data, reduce paperwork requirements for individuals, and increase administrative efficiency for states. For most states, this has been a multi-year effort that has involved significant investments of time, staff, and resources, using available federal funding for system upgrades. State work has involved developing new business procedures; writing new state administrative rules; training staff; and designing and deploying complex eligibility systems. The administrative structure in some states has been transformed through these changes, with increasing efficiencies gained through automation leading to changing needs and roles for eligibility staff. It remains to be seen which of these policies or processes could be affected by a repeal of the ACA. However, reverting back to pre-ACA policies or implementing new policies would likely require major investments of time, staff, and resources. Moreover, changes to the Marketplaces could affect Medicaid eligibility systems and enrollment processes because the systems are interwoven in all states. For example, if SBM enrollment systems were dismantled, those states would need to move Medicaid eligibility decisions to a new system or potentially revert to an old system, if one has been maintained.

States are using available program options to expand access to coverage, further streamline enrollment and renewal processes, and charge premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid and CHIP. Under current program rules, states can choose from a range of options to expand coverage for many groups and further streamline enrollment and renewal processes beyond the new standardized processes included in the ACA. States have taken up many of these options, particularly to expand access to coverage for children and pregnant women. Most states also are using options to charge premiums and cost sharing to some Medicaid and CHIP enrollees. However, in most cases, states largely target premiums and above-nominal cost sharing to enrollees with relatively higher incomes. The program options available to states, states’ responses to these options, and the role of waivers could be affected by a repeal of the ACA or as part of broader efforts to restructure Medicaid.

Tables

Trend and State-by-State Tables

Table 2: Waiting Period for CHIP Enrollment, January 2017

Table 3: State Adoption of Optional Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Children, January 2017

Table 7: Coordination between Medicaid and Marketplace Systems, January 2017

Table 10: Features of Online Medicaid Accounts, January 2017

Table 11: Mobile Access to Online Medicaid Applications and Accounts, January 2017

Table 13: Presumptive Eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP, January 2017

Table 14: Express Lane Eligibility and 12-Month Continuous Eligibility for Children, January 2017

Table 15: Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Cost Sharing Requirements for Children, January 2017

Table 16: Premiums and Enrollment Fees for Children at Selected Income Levels, January 2017

Table 17: Disenrollment Policies for Non-Payment of Premiums in Children’s Coverage, January 2017

Endnotes

- Emily P Zammitti, Robin A Cohen, and Michael E Martinez, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2016, (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, November 2016), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201611.pdf. ↩︎

- “October 2016 Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), accessed January 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html. ↩︎

- Emily P Zammitti, Robin A Cohen, and Michael E Martinez, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2016, (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, November 2016), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201611.pdf. ↩︎

- The CHIP eligibility limit in Kansas is tied to the 2008 FPL; as such, it erodes annually as the FPL amount increases each year. Between 2016 and 2017 it declined from 247% to 238% FPL. ↩︎

- Vikki Wachino, CMCS Informational Bulletin, Section 1115 Demonstration Opportunity to Allow Medicaid Coverage to Former Foster Care Youth Who Have Moved to a Different State, November 21, 2016, available at https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib112116.pdf. ↩︎

- This count does not include states that offer buy-in options that are limited to children with disabilities. ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield and Anthony Damico, The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission for Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2016), https://modern.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. ↩︎

- “Cost-Sharing,” CMS, accessed December 2016, http://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/cost-sharing/cost-sharing.html. ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz and Laura Snyder, Premiums and Cost Sharing in Medicaid, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, February 2013), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/premiums-and-cost-sharing-in-medicaid/. ↩︎

- “October 2016 Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights,” CMS, accessed January 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/report-highlights/index.html. ↩︎

- Emily P Zammitti, Robin A Cohen, and Michael E Martinez, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-June 2016, (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, November 2016), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201611.pdf. ↩︎

New Interactive Map with Local Data: Estimated 2016 ACA Marketplace Enrollment by Congressional District

Additional Interactive Maps Chart Medicaid Expansion Enrollees by State

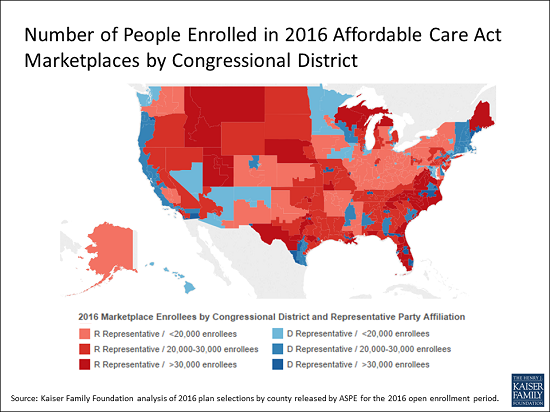

As the 115th U.S. Congress deliberates the future of the Affordable Care Act, a new interactive map from the Kaiser Family Foundation provides estimates of the number of people in each congressional district who enrolled in a 2016 ACA marketplace health plan and the political party of each district’s representative as of January.

The analysis, Interactive Maps: Estimates of Enrollment in ACA Marketplaces and Medicaid Expansion, finds that of 11.5 million ACA marketplace enrollees nationally as of March 31, 2016, 6.3 million live in districts with a Republican representative and 5.2 million live in districts represented by a Democrat.

The analysis also includes maps charting by state the total number of people enrolled under the ACA Medicaid expansion in 2015, along with the political parties of the governors and U.S. senators. Among states that adopted the Medicaid expansion as of January 2017, 16 have Republican governors, 14 have Democratic governors, and one has an Independent governor. In Washington, D.C., which also expanded Medicaid, the mayor is a Democrat.

All three maps can be embedded in web sites.

New Brief Examines the Future of Contraceptive Coverage

The Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive coverage provision made access to the full range of contraceptive methods available to millions of women with private insurance at no cost. Despite broad public support, this provision has been challenged by religious employers, with two cases reaching the Supreme Court.

It is unclear how or whether the new Trump administration and 115th Congress will address the contraceptive coverage requirement, either through administrative action or through efforts to repeal the ACA. If the requirement is modified or eliminated, no cost contraceptive coverage for millions of women is at stake, and the scope of a woman’s contraceptive coverage would again depend on her insurance plan and where she lives and works.

A new brief from the Kaiser Family Foundation explains the ACA’s contraceptive coverage rule, the impact it has had on women, and the potential state of coverage if the rule is modified or eliminated.

The Future of Contraceptive Coverage

Issue Brief

Contraceptive coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made access to the full range of contraceptive methods affordable to millions of women. This provision is part of a set of services that has been identified by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as key preventive services for women that are not addressed by the US Preventive Services Task Force or the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, entities that identified preventive services that must be covered without cost-sharing under the ACA. On December 20, 2016, HRSA issued updated coverage requirements, accepting in whole the recommendations of the Women’s Preventive Services Committee, which is comprised of representatives of national groups with expertise in women’s health. These updated recommendations continue to include contraceptive coverage.

Since it was first issued in 2012, this provision has been controversial. While very popular with the public, with over 77% of women and 64% of men reporting support for no-cost contraceptive coverage (Figure 1), it has been the focus of litigation brought by religious employers, with 2 cases reaching the Supreme Court. As the Trump administration transitions to the White House, it remains to be seen specifically how or whether the new Administration and 115th Congress will address this particular provision. This brief explains the current contraceptive coverage rule, the impact it has had on coverage, and the potential state of coverage if the ACA rule is eliminated either through a full ACA repeal or administrative action.

What does the contraceptive coverage rule require plans to cover?

Starting in 2012, all new private plans were required to cover, without cost-sharing, the full range of contraceptives approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as prescribed for women, counseling and services.1 This provision applies to all non-grandfathered individual, small and large group, and self-funded plans. Grandfathered plans do not have to comply with this requirement or the other insurance reforms in the ACA.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued guidance in May 2015, which clarified that at least one form of all 18 FDA-approved methods of birth control must be covered without cost-sharing (Table 1). If a provider recommends a specific option or product, plans must cover it without cost-sharing as well. Insurers may use reasonable medical management, however, to limit coverage to brand-name drugs when a generic version exists, and can impose cost-sharing for equivalent branded drugs. Plans are required to have a “waiver” process for women who have a medical need for contraceptives otherwise subject to cost-sharing or not covered.2 In addition, plans must cover services such as contraceptive counseling, initiation of contraceptive use, and follow-up care, including management and evaluation, as well as changes to and removal or discontinuation of contraceptive methods.

| Table 1 : Minimum Contraceptive Coverage Requirements Clarified by HHS Guidance | |

| Contraceptive Method | Products/Options |

| Surgical sterilization | Also called tubal ligation |

| Implant sterilization | Only Essure available |

| Implantable Rod | Multiple |

| IUD – Copper | Only ParaGard available |

| IUD – Progestin | Multiple |

| Injection | Multiple |

| Oral contraceptives – combined | Multiple |

| Oral Contraceptives – progestin only | Multiple |

| Oral Contraceptives – extended/continuous use | Multiple |

| Patch | Multiple |

| Vaginal Ring | Only NuvaRing available |

| Diaphragm with Spermicide | Only Milex Omniflex available |

| Sponge with Spermicide | Only Today Sponge available |

| Cervical Cap with Spermicide | Only FemCap available |

| Female Condom | Multiple |

| Spermicide alone | Multiple |

| Emergency Contraception-Progestin | Multiple |

| Emergency Contraception- Ulipristal Acetate | Only ella available |

| SOURCES: FDA, Birth Control Guide and Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Treasury, FAQs about Affordable Care Act Implementation (Part XXVI). | |

What are the coverage requirements for employers?

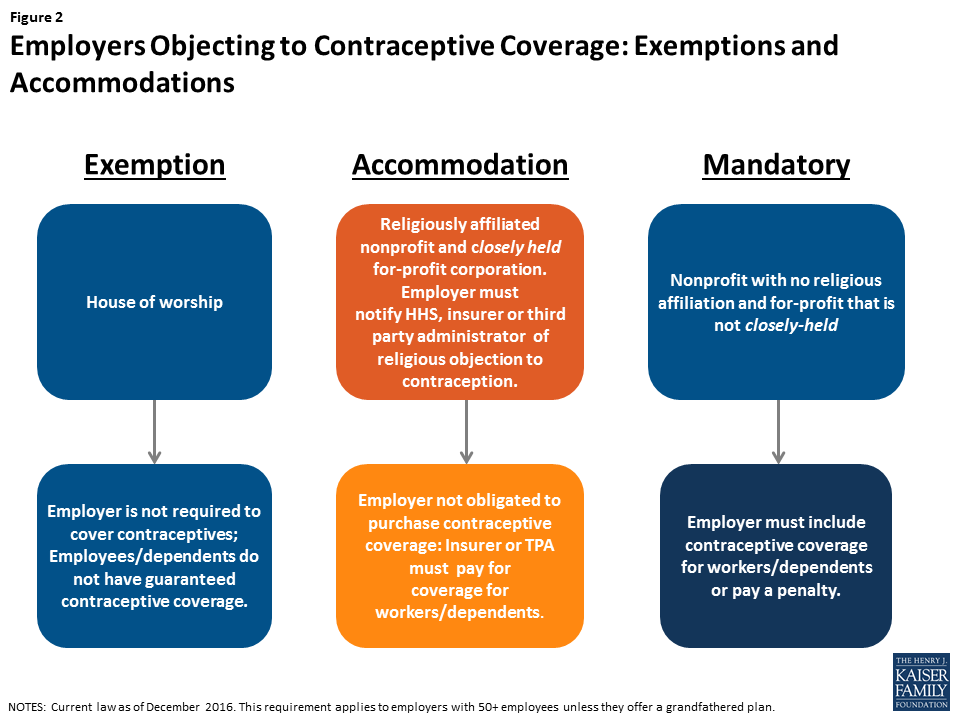

As the contraceptive coverage rules have evolved through litigation and new regulations, there are three categories of employers with differing requirements. Most employers are required to include the coverage in their plans. Houses of worship can choose to be exempt from the requirement if they have religious objections (Figure 2). This exception means that workers and dependents of exempt employers do not have coverage for either some or all FDA approved contraceptive methods, if their employer has an objection. Religiously affiliated nonprofits and closely held for-profit corporations are not eligible for an exemption, but may receive an accommodation. The Obama Administration originally crafted the accommodation to address the concerns of religiously-affiliated nonprofit employers, and then extended this same option to closely held for-profits after the Supreme Court ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby. The accommodation allows these employers to opt out of providing and paying for contraceptive coverage in their plans by either notifying their insurer, third party administrator, or the federal government of their objection. The insurers then are responsible for covering the costs of contraception, which assures that their workers and dependents have contraceptive coverage, and relieves the employers of the requirement to pay for it.

While 10% of nonprofits with 5,000 or more employees have elected for an accommodation without challenging the requirement, this approach, however, has not been acceptable to all nonprofits with religious objections.3 Some are seeking an “exemption” from the rule, meaning their workers would not have coverage for some or all contraceptives, rather than an accommodation, which entitles their workers to full contraceptive coverage but releases the employer from paying for it. In May 2016, the Supreme Court remanded Zubik v. Burwell, sending 7 cases brought by religious nonprofits objecting to the contraceptive coverage accommodation back to the respective Courts of Appeal. The Court instructed the parties to work together to “arrive at an approach going forward that accommodates petitioners’ religious exercise while at the same time ensuring that women covered by petitioners’ health plans receive full and equal health coverage, including contraceptive coverage.”4 In July 2016, the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Labor and Treasury issued a Request for Information (RFI) inviting public comments on “whether there are alternative ways (other than those offered in current regulations) for eligible organizations that object to providing coverage for contraceptive services on religious grounds to obtain an accommodation, while still ensuring that women enrolled in the organization’s health plans have access to seamless coverage of the full range of Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives without cost sharing.” The Obama Administration asked the courts to delay any action on the cases while they review the over 50,000 comments submitted. The next case status reports with the courts are due after the transition to the Trump Administration. It is not clear whether the Trump Administration will continue to defend these lawsuits, maintain the current regulations, or change the rules for employers with objections to contraceptive coverage. The Trump campaign supported expanding the exemption for nonprofits with religious objections, and incoming Secretary of Health and Human Services, Tom Price, stated in 2012, that he felt the contraceptive coverage requirement infringes on religious liberties.5 6

How has the contraceptive coverage rule affected women?

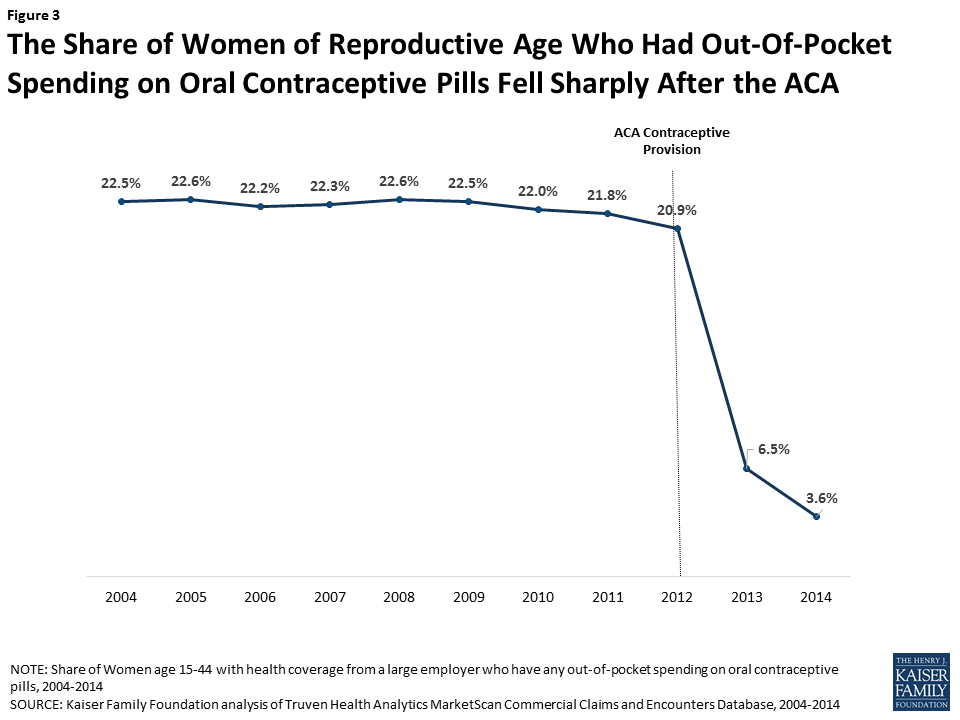

Contraceptive use among women is widespread, with over 99% of sexually-active women using at least one method at some point during their lifetime.7 Contraceptives make up an estimated 30-44% of out-of-pocket health care spending for women.8 Since the implementation of the ACA, out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs has decreased dramatically (Figure 3). The majority of this decline (63%) can be attributed to the drop in out-of-pocket expenses on the oral contraceptive pill for women.9 One study estimates that roughly $1.4 billion dollars per year in out-of-pocket savings on the pill resulted from the ACA’s contraceptive mandate.10 By 2013, most women had no out-of-pocket costs for their contraception, as median expenses for most contraceptive methods, including the IUD and the pill, dropped to zero.11

This provision has also influenced the decisions women make in their choice of method. After implementation of the ACA contraceptive coverage requirement, women were more likely to choose any method of prescription contraceptive, with a shift towards more effective long-term methods.12 High upfront costs of long-acting methods, such as the IUD and implant, had been a barrier to women who might otherwise prefer these more effective methods. When faced with no cost-sharing, women choose these methods more often13 , with significant implications for the rate of unintended pregnancy and associated costs of childbirth.14

Finally, decreases in cost-sharing were associated with better adherence and more consistent use of the pill. This was especially true among users of generic pills. One study showed that even copayments as low as $6 were associated with higher levels of discontinuation and non-adherence,15 increasing the risk of unintended pregnancy.

If the contraceptive coverage rule is modified or eliminated, are there other federal rules and state laws that affect coverage?

More than half of women in the United States are insured through an employer-sponsored plan, either as the primary beneficiary or as a spouse or dependent. In 2000, a ruling by the Employment Equal Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that employers that covered preventive prescription drugs and services, but did not cover prescription contraceptives, were in violation of the Civil Rights Act.16 The EEOC reasoned that failure to cover contraception constituted sex discrimination under Title VII and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which prohibits discrimination against women based on their ability to get pregnant. This ruling, however, did not address the issue of cost-sharing, nor the scope of coverage.

Prior to the passage of the ACA and the contraceptive coverage requirement, the 2010 Kaiser/HRET survey of employers found that 85% of large firms covered prescription contraceptives in their largest health plans17 , although they may have used cost-sharing and were not required to cover the full scope of contraceptive care, the amount of which can vary greatly by employer and type of plan. If the ACA contraceptive coverage rule is modified or eliminated, any requirement for the coverage of contraceptives without cost-sharing will fall back to the states. State laws, however, only apply to state regulated plans, not self-funded plans where 61% of covered workers are insured.18 In self-funded plans, the employer assumes the risk of providing covered services and usually contracts with a third party administrator (TPA) to manage the claims payment process. These plans are overseen by the Federal Department of Labor under the Employer Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

States have historically regulated insurance, and many have mandated minimum benefits for decades. Contraceptive coverage is no exception. Currently, 28 states require insurance plans to cover contraceptives, with a wide range of coverage and cost-sharing requirements, and exemptions among these mandates.19

Since the passage of the ACA, four states have strengthened and expanded the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. In 2014 California passed the Contraceptive Coverage Equity Act of 2014, which requires private and Medicaid managed care plans to cover all prescribed FDA-approved contraceptives for women without cost-sharing. Maryland enacted a very similar law in 2016, and it will go into effect in January 2018. Vermont also passed a similar law (effective January 2017) that applies to all health insurance plans, as well as coverage offered through Medicaid and all other public programs offered by the State. Illinois’s law, (effective January 2017) requires plans to cover all contraceptive methods, including all over-the-counter methods except male condoms, without cost-sharing.

While contraceptive coverage without cost-sharing will remain intact for fully insured plans in these 4 states, regardless of what happens with the ACA rule, state laws do not have jurisdiction over self-funded plans, under which many women are insured.

Conclusion

For the first time, the ACA set federal preventive services rules, including no-cost contraceptive coverage, for all insurance plans. If the Trump Administration modifies or eliminates the ACA contraceptive coverage rule, scope of coverage will depend on where a woman lives, where she works, and her insurance plan. Millions of women could lose no-cost coverage for the full range of contraceptive methods. Insurance companies and employers will be the ones to make choices about coverage and cost-sharing. For some women, their choices will be limited, and some of the most effective and costly methods will be out of financial reach.

Endnotes

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2015). HPV, HIV, Birth Control. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2015). FAQs about the Affordable Care Act Implementation (Part XXVI). ↩︎

- Sobel, L., Rae, M., & Salganicoff, A. Data Note: Are Nonprofits Requesting an Accommodation for Contraceptive Coverage?, Kaiser Family Foundation (Dec. 2015). ↩︎

- Supreme Court of the United States, per curium opinion, Zubik v. Burwell, May 16, 2016, page 4 ↩︎

- Charisma News. (2016). Read the Letter Donald Trump Wrote to Catholic Leaders. ↩︎

- ThinkProgress. (2012). House Republican Leader Price: ‘There’s Not One Woman’ Who Doesn’t Have Access To Birth Control ↩︎

- Guttmacher Institute. (2016). Contraceptive Use in the United States. ↩︎

- Nora V. Becker and Daniel Polsky. Women Saw Large Decrease in Out-Of-Pocket Spending for Contraceptives After ACA Mandate Removed Cost Sharing. Health Affairs 34, no.7 (2015):1204-1211. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016). Examining high prescription drug spending for people with employer sponsored health insurance. ↩︎

- Nora V. Becker and Daniel Polsky. Women Saw Large Decrease in Out-Of-Pocket Spending for Contraceptives After ACA Mandate Removed Cost Sharing. Health Affairs 34, no.7 (2015):1204-1211. ↩︎

- Adam Sonfield, Athena Tapales, Rachel K. Jones, and Lawrence B. Finer. Impact of the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee on out-of-pocket payments for contraceptives: 2014 update. Contraception 91 (2015) 44-48. ↩︎

- Caroline S. Carlin, Angela R. Fertig and Bryan E. Dowd. Affordable Care Act’s Mandate Eliminating Contraceptive Cost Sharing Influenced Choices of Women with Employer Coverage. Health Affairs 35, no.9 (2016):1608-1615. ↩︎

- Birgisson, N. E., Zhao, Q., Secura, G. M., Madden, T., & Peipert, J. F. (2015). Preventing Unintended Pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in Review. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(5), 349–353. ↩︎

- Birgisson, N. E., Zhao, Q., Secura, G. M., Madden, T., & Peipert, J. F. (2015). Preventing Unintended Pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in Review. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(5), 349–353. ↩︎

- Lydia E. Pace, Stacie B. Dusetzina and Nancy L. Keating. Early Impact of the Affordable Care Act On Oral Contraceptive Cost Sharing, Discontinuation, And Nonadherence. Health Affairs 35, no.9 (2016):1616-1624. ↩︎

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. December 14, 2000. Decision- Contraception. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010). 2010 Employer Health Benefits Survey. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research Educational Trust, 2014 Employer Health Benefits Survey. ↩︎

- Guttmacher Institute. (2016). State Policies in Brief: Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives. ↩︎

Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: Health Care Priorities for 2017

Findings

KEY FINDINGS:

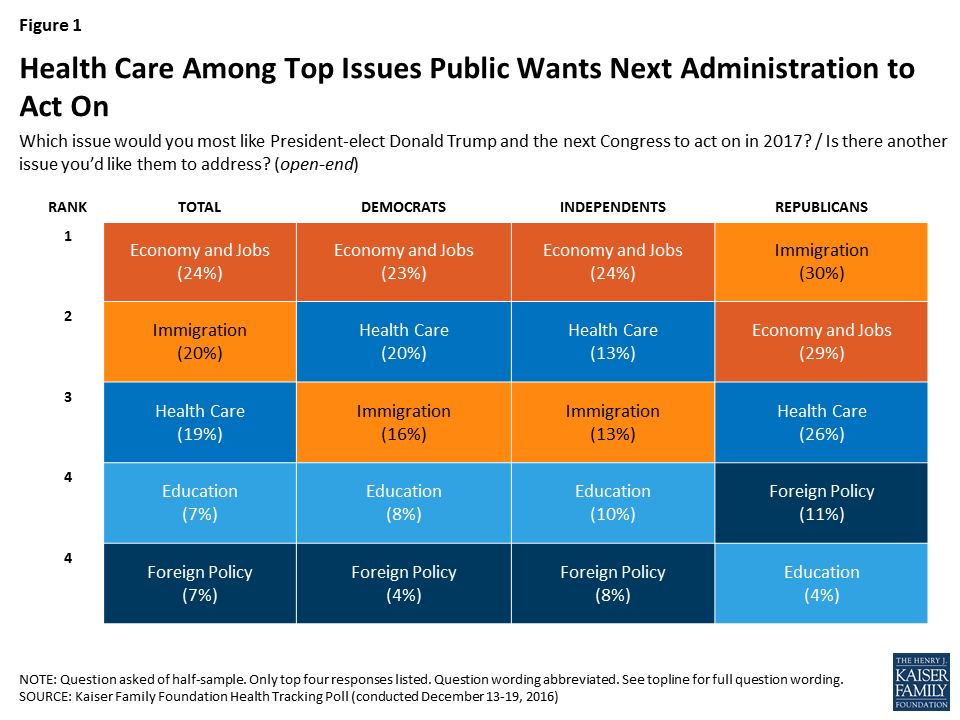

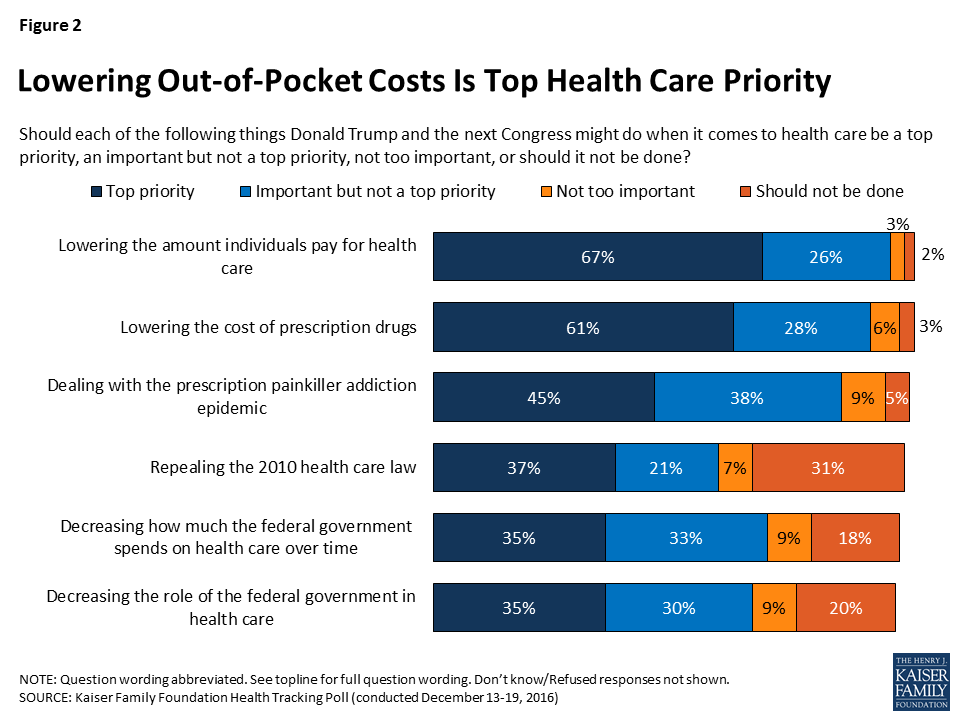

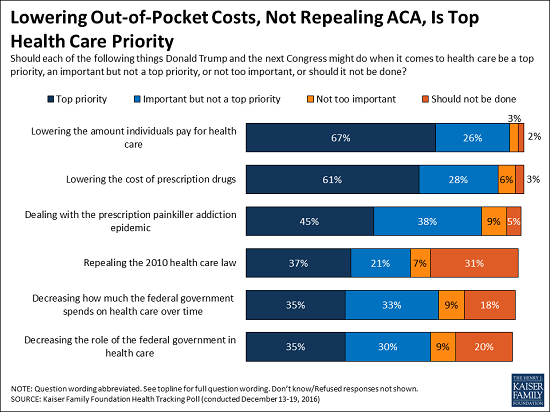

- The latest Kaiser Health Tracking Poll finds that health care is among the top issues, with the economy and jobs and immigration, Americans want President-elect Donald Trump and the next Congress to address in 2017. When asked about a series of health care priorities for President-elect Trump and the next Congress to act on, repealing the ACA falls behind other health care priorities including lowering the amount individuals pay for health care, lowering the cost of prescription drugs, and dealing with the prescription painkiller addiction epidemic.

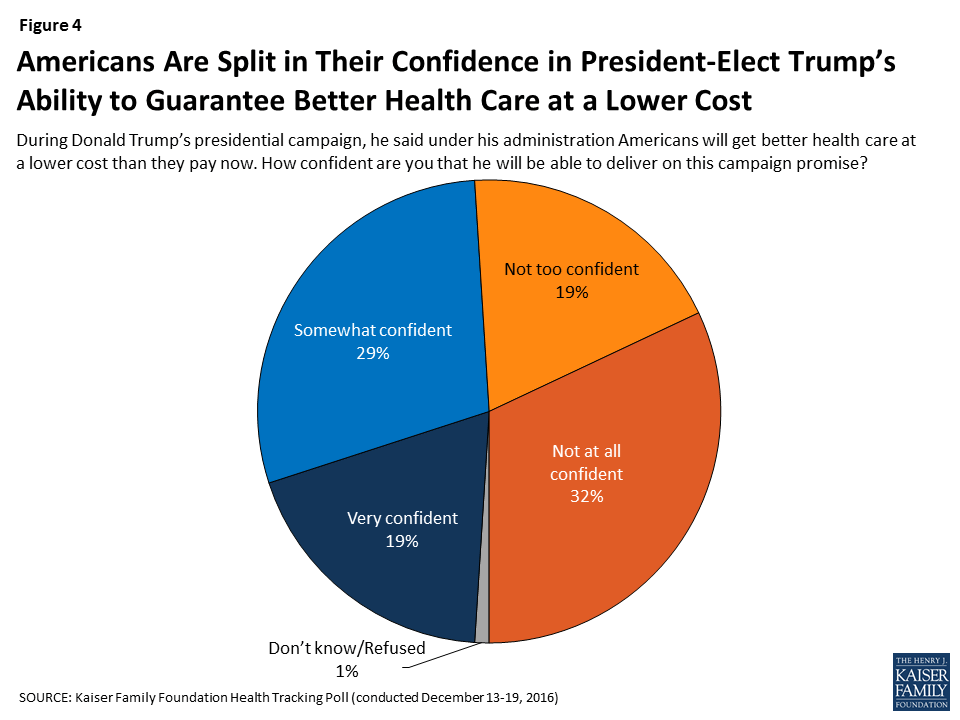

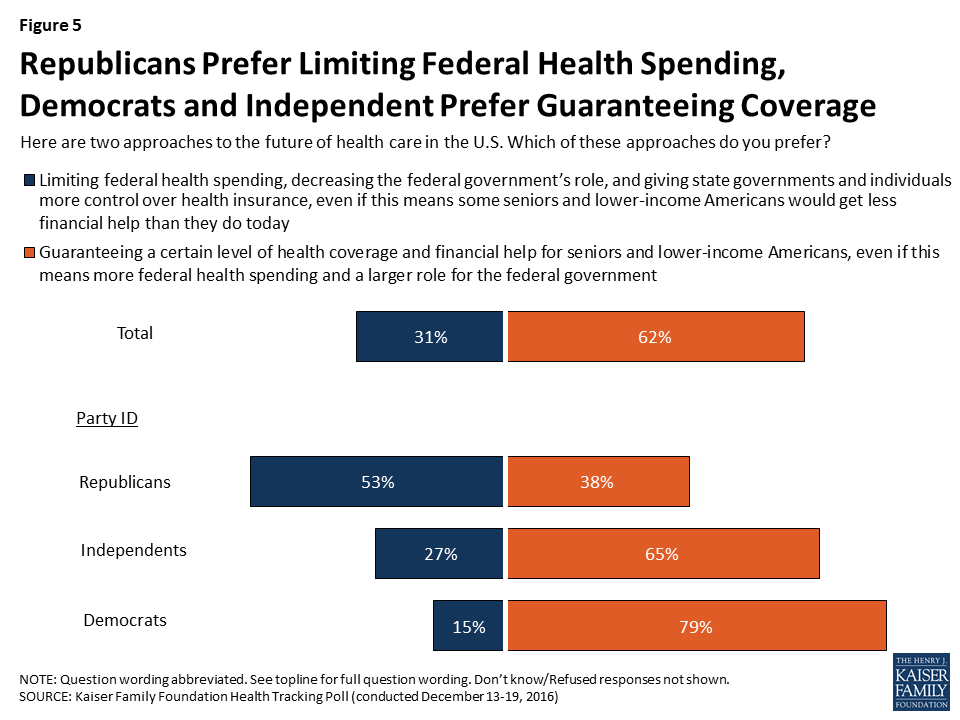

- When presented with two general approaches to the future of health care in the U.S., six in ten (62 percent) Americans prefer “guaranteeing a certain level of health coverage and financial help for seniors and lower-income Americans, even if it means more federal health spending and a larger role for the federal government” while three in ten (31 percent) prefer the approach of “limiting federal health spending, decreasing the federal government’s role, and giving state governments and individuals more control over health insurance, even if this means some seniors and lower-income Americans would get less financial help than they do today.”

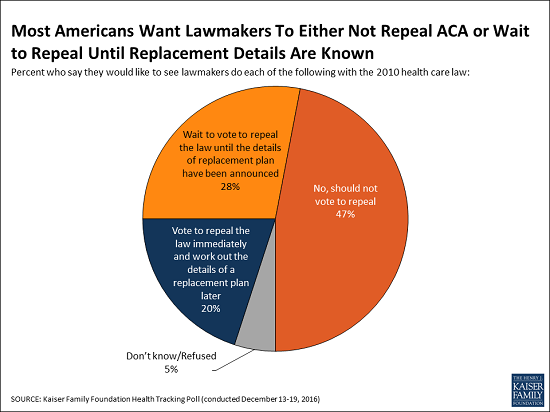

- As Congressional lawmakers make plans for the future of the ACA, the latest survey finds the public is divided on what they would like lawmakers to do when it comes to the 2010 health care law. Forty-nine percent of the public think the next Congress should vote to repeal the law compared to 47 percent who say they should not vote to repeal it. Of those who want to see Congress vote to repeal the law, a larger share say they want lawmakers to wait to vote to repeal the law until the details of a replacement plan have been announced (28 percent) than say Congress should vote to repeal the law immediately and work out the details of a replacement plan later (20 percent). However, the survey also finds malleability of attitudes towards Congress repealing the health care law with both supporters and opponents being persuaded after hearing counter-messages.

Top Issues for President-elect Trump and Congress

The latest Kaiser Health Tracking Poll finds health care among the top issues Americans want President-elect Donald Trump and the next Congress to address in 2017. When asked which issue they would most like the next administration to act on in 2017, one-fourth of the public mention the economy and jobs (24 percent), followed by immigration (20 percent), and health care (19 percent). Among Democrats and independents, the economy and jobs is the top issue (23 percent and 24 percent, respectively) while the top issues for Republicans are immigration (30 percent) and economy and jobs (29 percent). Among all partisans, health care ranks among the top three issues that the public wants the next administration to act on in 2017.

The top issue for voters who supported President-elect Donald Trump are similar to those among Republicans: economy and jobs (31 percent) and immigration (31 percent), followed closely by health care (27 percent).

When asked to mention which health care issue they would most like President-elect Trump and the next Congress to act on in 2017, about one-third of the public mention the Affordable Care Act (ACA) but attitudes are mixed between wanting the next administration to act on repealing the 2010 health care law (14 percent), improving/fixing the law (11 percent), or keeping/expanding the law (8 percent).