Introducción

La política de inmigración ha sido y continúa siendo un tema controversial en los Estados Unidos. Durante el transcurso de las elecciones y desde que asumió el cargo, el presidente Donald Trump ha intensificado el debate nacional sobre inmigración ya que ha implementado reglas para reforzar la aplicación de las leyes migratorias y restringir la entrada de inmigrantes de ciertos países que, la administración cree, pueden significar una amenaza para el país. (Apéndice 1). El clima alrededor de estas políticas y este debate afectan potencialmente a 23 millones de personas que viven en el país y no son ciudadanas, incluyendo a ambas: aquéllas con presencia legal y a los inmigrantes indocumentados, muchos de los cuales vinieron a los Estados Unidos en busca de seguridad y para mejorar las oportunidades para sus familias3 . También tienen implicaciones para los más de 12 millones de niños que viven con un padre que no es ciudadano, los cuales predominantemente son ciudadanos estadounidenses4 . Este informe provee una mirada sobre cómo el medio ambiente actual está afectando la vida diaria, el bienestar y la salud de las familias inmigrantes, incluyendo a sus niños. Los hallazgos se basan en grupos de discusión realizados con 100 padres de familias inmigrantes de 15 países, y entrevistas telefónicas con 13 pediatras que atienden a comunidades de inmigrantes.

Métodos

Durante el otoño de 2017, la Kaiser Family Foundation trabajó con PerryUndem Research/Communication para realizar grupos de discusión con 100 padres de familias inmigrantes. Los participantes en los grupos de discusión se seleccionaron para representar un rango de razas/etnias, países de origen, y estatus migratorio, y para proveer experiencias con diversidad geográfica. Se realizaron un total de 10 grupos de discusión en 8 ciudades de cuatro estados (Chicago, Illinois; Boston, Massachusetts; Bethesda, Maryland; y Anaheim, Fresno, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego, California). Además, se realizaron 13 entrevistas telefónicas con pediatras y clínicas que atienden a familias de inmigrantes. Con la asistencia de la American Academy of Pediatrics, se identificaron pediatras que atienden a diferentes poblaciones inmigrantes en un amplio rango de estados (Arkansas, California, Illinois, Minnesota, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Vermont) y el Distrito de Columbia. La Blue Shield of California Foundation apoyó los grupos de discusión y las entrevistas realizadas en California.

Los grupos de discusión se realizaron en 5 idiomas con padres provenientes de 15 países. Hubo seis grupos de discusión de hispanohablantes con padres de México, el Caribe, Centroamérica y Sudamérica, un grupo con padres coreanos; un grupo con padres que hablan portugués de Brasil y Cabo Verde; un grupo con padres que hablan farsi de Afganistán; y otro grupo de padres que habla árabe de Irak, Egipto y Siria. Los participantes incluyeron a personas con un rango de estatus migratorio: indocumentados, refugiados/con asilo; y residentes permanentes legales (que tienen una green card). (Ver Apéndice 2 para tener una mirada general sobre los estatus migratorios seleccionados). Cuatro de los grupos se organizaron en instalaciones para grupos de discusión, los seis restantes en organizaciones comunitarias. Dado que los participantes en los grupos organizados por las entidades comunitarias a menudo recibían servicios a través de la organización, generalmente estaban conectados a más recursos y tenían más conocimientos sobre sus derechos en comparación con la comunidad en general.

Se realizaron entrevistas telefónicas uno-a-uno con pediatras. Los pediatras entrevistados atienden a una variedad de familias inmigrantes, incluyendo a inmigrantes latinos de México, Centroamérica y Sudamérica, así como a inmigrantes de otra serie de países y regiones, incluyendo Bután, Burma, China, India, Corea, Myanmar, Mongolia, Vietnam, Yemen, la República Democrática del Congo, Somalia, Etiopía, Eritrea, Europa del Este y el Medio Oriente.

Hallazgos Clave

Panorama de los padres participantes y de sus familias

Los padres participantes migraron a los Estados Unidos para escapar de la guerra o de la actividad de las pandillas en sus países de origen, por oportunidades de trabajo y educación, y/o para reunirse con familiares. Algunos padres contaron historias sobre la pérdida de seres queridos en guerras o por la violencia de pandillas en sus países de origen, y dijeron que migraron a los Estados Unidos en busca de seguridad. De la misma manera, refugiados y personas con asilo migraron para escapar de la guerra o la persecución en sus países de origen. Muchos padres también destacaron que sus países de origen tienen altas tasas de pobreza, sistemas de educación inadecuados, y pobres perspectivas de trabajo, y que venir a los Estados Unidos provee a sus familias mejores oportunidades laborales y de educación. Algunos participantes también vinieron a los Estados Unidos para unirse a otros miembros de la familia que habían migrado previamente. Los participantes variaron ampliamente en cuanto al tiempo que llevan viviendo en los Estados Unidos. Algunos estaban en el país desde hacía muchos años, mientras que otros habían llegado más recientemente. Algunos llegaron a los Estados Unidos de niños y no tienen experiencias en sus países de origen. Un número de participantes, particularmente refugiados y personas con asilo que escaparon de la guerra, expresaron cuán agradecidos estaban por la oportunidad de estar en los Estados Unidos.

“Mataron a tres miembros de mi familia y… me fui.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Soy salvadoreño y, por la guerra, vine aquí. Asesinaron a mi hermano y entonces vine aquí.” -Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“En México no hay oportunidades, incluso para la gente joven. El medio ambiente es demasiado violento.” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Muchos de nosotros vinimos de niños, y no teníamos idea sobre el futuro. Ahora no tenemos otra opción más que quedarnos porque… tenemos miedo de volver a un lugar con el que no estamos familiarizados.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Estoy aquí desde que tenía 6 años, tengo una hija que tiene 6. No estoy familiarizada con ningún otro país. Amo a este país.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“…nuestro padre nos trajo aquí para de esa manera tener mejor educación.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“El gobierno de los Estados Unidos nos recibió porque no nos estábamos sintiéndonos seguros en nuestros países y porque éramos discriminados. Agradecemos a los Estados Unidos por eso.” –Padre que habla árabe, Anaheim, California

“Una de las principales razones es la seguridad, en términos de seguridad física, mental, emocional …” –Padre afgano, Oakland, California

“…allí [en México], hay mucho crimen.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

Los niños de los padres que participaron son mayormente ciudadanos nacidos en los Estados Unidos. De manera similar, los pediatras destacaron que en muchas de las familias que atienden, los niños nacieron en los Estados Unidos mientras que uno o ambos padres pueden ser indocumentados. Algunos padres también tienen hijos mayores que trajeron con ellos a los Estados Unidos, los cuales obtuvieron un estatus bajo el Programa de Acción Diferida para los Llegados en la Infancia (DACA) o son indocumentados. Unos pocos todavía tienen niños en sus países de origen. Los padres destacaron que sus niños nunca han visitado sus países de origen y que los Estados Unidos es el único hogar que conocen. Los hijos de refugiados y personas con asilo incluyen una mezcla de aquellos que volaron a los Estados Unidos con sus padres, y niños más pequeños que nacieron en los Estados Unidos.

Las barreras económicas y del lenguaje son una gran preocupación para muchos participantes. Los participantes generalmente tienen al menos un trabajador en la familia, a menudo en servicios, construcción, o trabajos de jardinería. Muchos indicaron que están tratando de encontrar la mayor cantidad de trabajo posible, pero todavía viven quincena a quincena. Destacaron que los costos de la renta y las compras continúan aumentando, haciendo difícil llegar a fin de mes. Los participantes que llegaron a los Estados Unidos más recientemente, en particular aquéllos de países de Medio Oriente, describieron desafíos asimilando la vida en los Estados Unidos, destacando la presión por encontrar trabajo rápidamente y la dificultad que enfrentan debido a las barreras culturales y del idioma. Algunos señalaron que tenían carreras profesionales en sus países de origen, y que han tenido que trabajar en empleos menos calificados cuando se establecieron.

Miedos y preocupaciones entre las familias

Padres y pediatras dijeron que el miedo a la deportación y los sentimientos generales de incertidumbre han aumentado desde la elección presidencial. Los padres que son indocumentados, o que tienen un miembro de la familia que lo es, expresaron miedos crecientes a ser separados de sus hijos y/o cónyuge. Algunos también temen volver a sus países de origen por la violencia o la actividad de las pandillas. Un número de participantes tienen amigos y/o familiares que fueron detenidos o deportados recientemente. También describieron redadas recientes y actividad de oficiales de inmigración en sus vecindarios, en las calles y en sus lugares de trabajo. Un pediatra destacó que, aunque se percibe que estos miedos entre los inmigrantes indocumentados afectan principalmente a latinos, hay un número creciente de indocumentados asiáticos que también están sintiendo más miedo.

“El área en donde vivo… la mayoría de las redadas ocurren allí. Y escuchamos muchos casos sobre personas que deportan de sus apartamentos en esa área… la comunidad está tan asustada.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Si mi esposo es deportado, ¿cómo se supone que viviré aquí sin él? No hay manera. Quiebra a toda la familia.” –Padre que habla portugués, Boston, Massachusetts

“…nos levantamos todas las mañanas con miedo a ser deportados, a la separación de nuestras familias, a tener que dejar a los niños.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“…soy ambos, mamá y papá para mis hijos… por eso, debo estar ahí, y pienso, Dios perdóname, pero si me detienen, me deportarán …” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“…todos están temerosos porque tienen sus vidas aquí. No tienen papeles, pero tienen sus vidas aquí y ya no tienen nada en México porque, quiero decir, está años atrás. No hay forma que se mantengan allí.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Me pasó varias veces que escuchas que alguien golpea a tu puerta y se lleva a tus familiares y los encierra.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Están poniendo más presión en la frontera. Revisan todo.” –Padre latino, San Diego, California

“Creo que todo asusta más. Hay más miedo en mi personalmente hablando… ahora siento que es personal. No antes, pero ahora lo siento.” –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“Los peores miedos son que nos separen… que vayan a separar familias.” –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

Los sentimientos de mayor miedo e incertidumbre se extienden a aquéllos con estatus legal. Por ejemplo, padres coreanos en Chicago y afganos en Oakland dijeron que sentían que tener una green card ya no era suficiente y que necesitan obtener la ciudadanía para asegurar su estatus. Algunos dijeron que, incluso con una green card, ya no se sentían seguros viajando fuera del país, porque les preocupa que puedan tener problemas al regresar a los Estados Unidos. Algunos padres también dijeron que, desde la elección, se ha vuelto más difícil obtener la ciudadanía, y que el período de tiempo para obtener una green card o la ciudadanía ha aumentado. Los padres que hablan árabe y un número de pediatras informaron que los refugiados y personas con asilo se sienten inseguros y preocupados sobre si podrán permanecer en el país. Los pediatras enfatizaron que los refugiados y personas con asilo llegan con historias de persecución del gobierno y que es difícil para ellos confiar en que permanecerán protegidos. Además, algunos padres expresaron preocupación que el gobierno pueda eliminar el Estatus de Protección Temporal (TPS) para las personas de Nicaragua, El Salvador y Honduras5 . Algunos padres dijeron que, aunque las políticas actuales no los han afectado, les preocupa que las reglas cambien, causando que pierdan el estatus o el permiso para permanecer en los Estados Unidos.

“Me siento inquieto. Aunque ya tenemos la green card, si no solicitamos la ciudadanía, no creo que podamos estar tranquilos.” –Padre coreano, Chicago, Illinois

“Antes de esto, estábamos viviendo aquí con residencia permanente sin ciudadanía y pensábamos que no sería un problema… pero después que Trump fue electo, pensé, si quiero vivir aquí y criar a mi hijo, tendré que solicitar la ciudadanía.” –Padre coreano, Chicago, Illinois

“Incómodo e inestable; creemos que en cualquier momento se podría emitir una nueva norma que lleve a expulsarnos y enviarnos de vuelta.” –Padre que habla árabe, Anaheim, California

“No hay estabilidad. [El presidente] podría escribir un tweet en Twitter mañana y poner las cosas patas para arriba.” –Padre que habla árabe, Anaheim, California

“…Las nuevas leyes están siendo aprobadas, nos mantienen con una sensación de incertidumbre… TPS… DACA, ¿qué va a pasar en seis meses?” – Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“La preocupación es que hoy es un grupo, y mañana puede ser otro. Hoy podemos estar contentos de que nos hayan dejado solos, pero mañana podría ser otra historia.” – Padre afgano, Oakland, California

“Cuando se eligió al presidente Trump, había un enorme, enorme temor en nuestras comunidades de refugiados y nuestras comunidades de inmigrantes. No importaba que tuvieran estatus legal…” –Pediatria, Vermont

“Incluso si ellos mismos no están directamente en riesgo porque estarían en una situación migratoria que los beneficia, especialmente en el caso de los refugiados, están tan acostumbrados a temer al gobierno y desconfían del gobierno…” –Pediatria, California

Padres y pediatras destacaron una particular preocupación entre los jóvenes que obtuvieron DACA. En los grupos de discusión que se realizaron antes de la revocación de DACA, los padres expresaron preocupaciones sobre la seguridad de DACA, temiendo que el programa fuera eliminado. En los grupos realizados después de la revocación de DACA, padres reportaron que el miedo y la incertidumbre entre los recipientes de DACA se había intensificado, con muchos preocupados por su situación actual y perdiendo esperanza en el futuro.

“Los niños que están en la escuela también están preocupados, los que van a la universidad, porque no sabemos qué pasará con DACA …”—Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Hablo en el caso de DACA. Todos están en el camino correcto. Todos están estudiando, pero aún enfrentan riesgos. Entonces, puede sucedernos a cualquiera de nosotros… Todo depende de [el presidente] y de las leyes que crean.” –Padre que habla portugués, Boston, Massachusetts

“Está yendo para atrás, porque todo lo que Obama ayudó a los dreamers, bueno, ahora todos sienten miedo porque Trump quiere quitar eso …” –Padre latino, San Diego, California

“…ella pudo obtener DACA … si no puede renovarlo, está pensando que irán a buscarla porque tienen toda su información.” –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“…Tengo dos primos y estaban bajo la Ley DREAM … todos tienen trabajos e iban a la escuela y… conocen toda su vida aquí. Y todo, para que simplemente se los lleven.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Conozco a alguien con DACA que lo obtuvo recientemente y… desde que obtuvo su permiso de trabajo se le abrieron muchas puertas… entonces sus sueños fueron enormes, pero ahora, frenando DACA, tiene tanto miedo.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“[Yo estaba] en el proceso [de solicitud de DACA] cuando escuchamos las noticias. Fue realmente doloroso… estaba haciendo las cosas bien, por mi cuenta… para buscar un futuro para mí y para mis hijos. Entonces entra la depresión, ¿qué voy a hacer ahora?” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Recientemente también tengo un par de pacientes … más de un par… con quienes he hablado, que son recipientes de DACA que se sienten muy inseguros sobre cuál será su futuro.” -Pediatria, District of Columbia

Los padres variaron en los niveles de miedo que sentían. Una variedad de factores influyó en el nivel de miedo que sentían los padres, incluyendo sus estatus migratorios y el de los miembros de la familia; experiencias en sus países de origen, razones por las que migraron a los Estados Unidos, el período de tiempo en el país; la extensión de la diversidad, apoyo y liderazgo en sus comunidades locales; y la exposición a las deportaciones y las redadas. Por ejemplo, algunos participantes en California que eran de México destacaron una disposición a restablecer sus vidas en México si ellos o un familiar era deportado, particularmente aquéllos en San Diego que están cerca de la frontera. Por el contrario, participantes de otros países que llegaron a los Estados Unidos para escapar de la guerra y/o la persecución dijeron que volver a sus países de origen no era una opción. Los padres que han vivido en los Estados Unidos por muchos años generalmente se sentían más seguros que aquellos que habían llegado más recientemente. Los padres conectados con las organizaciones comunitarias locales sintieron que estaban más informados sobre sus derechos en comparación con otros en la comunidad, y que los rumores difundidos a través de las redes sociales o el “boca a boca” a menudo conducen a un aumento de los miedos y el pánico basados en la información errónea. Un pediatra señaló que, entre las comunidades asiáticas, existe una renuencia a hablar sobre el estatus migratorio, lo que limita el intercambio de información y puede contribuir a aumentar los temores derivados de rumores o desinformación.

“…las comunidades latinas aquí en el valle, específicamente aquí en Fresno, tal vez no se sienten apoyadas porque nuestros líderes, nuestros líderes comunitarios, no han alcanzado el nivel para poder ofrecer el apoyo a todos.” – Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Ese es el problema con muchas personas, no se informan, no buscan la información real. Solo se basan en lo que escucharon en las noticias o en lo que les dijo su amigo.” – Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

Los niños también sienten un aumento del miedo y la incertidumbre sobre la posibilidad de perder a sus padres a causa de una deportación, o tener que regresar a los países de origen de sus padres. Padres a través de los grupos, incluyendo aquéllos con estatus legal, recordaron historias de sus niños, y niños en sus comunidades, llegando a casa llorando inmediatamente después de la elección presidencial, preocupados sobre qué pasaría con ellos y si tendrían que irse del país. Los padres dijeron que, aunque tratan de proteger a sus hijos de estos temas, muchos los están escuchando en la escuela. También dijeron que algunos niños han expresado temores e inquietudes sobre los países de origen de sus padres, señalando que los Estados Unidos es el único hogar que conocen.

“…después que Trump fue elegido, los niños lloraron en la escuela y dijeron que tenían que emigrar a Canadá. Los niños hablan mucho entre ellos.” –Padre coreano, Chicago, Illinois

“Después de la inauguración, mis hijos más pequeños lloraban porque pensaban que iban a ser deportados …” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Mis hijos llegaban a casa de la escuela y contaban que en la escuela decían que todos los padres serían deportados…” –Padre que habla portugués, Chicago, Illinois

“Todos los niños, incluso si nacieron aquí, tienen miedo. Temen que cada vez que regresan de la escuela no encontrarán a sus padres.” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Y entonces ella se puso triste. Y hasta lloró solo viendo las noticias y viendo cómo inmigración está haciendo redadas y cómo recogen gente.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“….ella se preocupa demasiado, más de lo que los niños deberían preocuparse. Quiero decir que es solo una niña pequeña. Realmente no puedes decirle que no se preocupe.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“[Mi hijo] de 15 años… pregunta, ‘¿cómo voy a regresar a Brasil si tengo que empezar todo de nuevo? …’ Dice… ‘si regreso, tengo que empezar de nuevo y perder mucho tiempo, y no sé si me adaptaré allí otra vez’.’” –Padre que habla portugués, Boston, Massachusetts

“Bueno, mis hijos se asustaron por mí. Ya sabes, cuando Donald Trump ganó, el más joven me abrazó y me dijo ‘mamá, no tienes ninguno de tus papeles’”. –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“Creo que hay temor e incertidumbre general que incluso los niños que pertenecen a familias que no tienen estatus de ciudadanía mixto, pero… son niños de color o niños que son latinos o niños cuya familia prefiere hablar español…” –Pediatria, North Carolina

“Honestamente, no solo son las familias indocumentadas… sino también las familias donde los niños son residentes legales permanentes o tienen estatus de refugiados. Me refiero incluso a esas familias: los padres vinieron y me dijeron que sus hijos estaban preocupados.” –Pediatria, Pennsylvania

“…ahora sentir estos temores cada vez mayores acerca de si van a ver a sus padres o no al final del día, ¿van a poder terminar la escuela, van a tener que mudarse…? Hay una gran cantidad de ansiedad.” –Pediatria, California

Los participantes y pediatras dijeron que el racismo y la discriminación, incluyendo el acoso de niños de color en las escuelas, ha aumentado significativamente desde la elección. Un número de padres dijo que las experiencias personales con el racismo y la discriminación han aumentado desde la elección y describieron incidentes recientes contra ellos mismos, amigos y/o familiares. Muchos sentían que los latinos, particularmente los mexicanos, y los musulmanes han sido los principales blancos del racismo y la discriminación crecientes. También señalaron que la intimidación a los niños ha aumentado en las escuelas y que se extiende más allá de los inmigrantes a los niños de color, independientemente de su estatus migratorio.

“Siempre ha habido racismo, pero en este momento ha salido a la superficie.” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Cuando viajo a lugares como el oeste o un lugar sin coreanos o étnicamente homogéneo, cuando es predominantemente blanco, tengo un poco de miedo.” –Padre coreano, Chicago, Illinois

“Hay algunas personas racistas que comenzaron a sentirse más cómodas desde que Trump fue elegido, y ahora expresan su odio hacia los inmigrantes más libremente.” –Padre que habla árabe, Anaheim, California

“…Donde trabajo, personalmente veo que la gente me discrimina… y tengo que intervenir por mis empleados. No tuve que hacerlo antes, pero ahora es como un renacimiento de la discriminación.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Trabajo en jardinería, y estamos trabajando y te ven trabajando… y empiezan a gritarte cosas…” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“…el caso es que este presidente, desde que hizo algunos comentarios que son muy racistas, ahora las personas que son de aquí en Fresno y donde sea que vayan… ahora también van en contra de nosotros.” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“…Creo que antes de Trump no había tanta discriminación como ahora.” – Padre latino, San Diego, California

“….mi cuñada estaba en el trabajo y le prohibieron hablar español.” – Padre latino, San Diego, California

“Después de la inauguración, mi hija… no podría estar bien en la escuela porque hay mucho racismo.” – Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“He tenido pacientes y padres que voluntariamente me dicen que sus hijos se enfrentan a más intimidación.” –Pediatria, Minnesota

“Los intimidan… les dicen cosas como ‘ahora tú y tu familia tendrán que irse’. Y así, a pesar de que esos niños en realidad no tienen que preocuparse por su estatus migratorio, creo que obviamente un niño, no conocen los detalles de cómo funciona el sistema.” –Pediatria, Pennsylvania

“…el miedo a ser uno mismo, ¿está bien ser musulmán, usar una hijab?, a muchos de los niños se los intimida por la forma en que se ven, la forma en que se visten, su identidad cultural, y por lo tanto hay mucha ansiedad.” –Pediatria, California

Efectos en la vida diaria

Algunas familias, particularmente aquéllas con un miembro indocumentado, están haciendo cambios en su vida diaria y rutinas en respuesta al miedo a la deportación. Algunos dijeron que solo salen de la casa cuando es necesario, por ejemplo, para trabajar; limitan el tiempo de manejo o solo conducen los que tienen un estatus legal; y/o limitan su tiempo fuera de sus vecindarios. Por ejemplo, padres en Boston dijeron que las familias solían colmar los parques los fines de semana con picnics y parrilladas, pero ahora estaban vacíos. Varios padres y pediatras indicaron que las familias ahora pasan largas horas dentro de sus hogares, bajo llave, temerosas cada vez que alguien toca a la puerta. Algunos padres y pediatras también notaron que la asistencia escolar disminuyó inmediatamente después de las elecciones y que se desploma después de una redada de inmigración o si hay un rumor de un allanamiento en la comunidad. Los padres en Maryland y California dijeron que algunas de las escuelas enviaron cartas para tranquilizar a las familias sobre su seguridad en la escuela, que, creen, ayudó a aliviar los temores. Las familias también temen cada vez más a la policía y las autoridades, y algunos padres y pediatras expresaron su preocupación que las personas se animen menos a denunciar agresiones, abusos u otros delitos. Otros participantes, especialmente aquéllos que han vivido en los Estados Unidos por muchos años y que residen en diversas comunidades con un fuerte apoyo, dijeron que continúan con su vida cotidiana y sus rutinas regulares a pesar del aumento de los temores.

“Antes, había muchos niños en los parques … pero ahora … Los niños pasan más tiempo dentro en estos días porque tenemos miedo de ser deportados.” – Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Tememos miedo de abrir la puerta o mirar a través de la mirilla para ver quién es…” – Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“También me preocupa porque si algo nos sucede en la calle, si nos agreden o algo así, ni siquiera podremos llamar a la policía porque verán que somos inmigrantes.” – Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“…pero ahora alrededor de las 6 o 7 de la tarde no encontrarás a nadie en [el vecindario] … por el miedo que todos sentimos sobre lo que va a suceder.” – Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Mi cónyuge no sale de la casa… lo último que quiere es que la detengan y que empiecen a hacerle preguntas …” – Padre latino, San Diego, California

“Hoy en día las personas evitan caminar por ciertos lugares.” – Padre que habla portugués, Boston, Massachusetts

“…la mayoría de ellos no fue a la escuela el primer día después que él ganó porque todos temían que sucediera algo.” – Padre latino, Boston Massachusetts

“En las escuelas, se levantan todas las mañanas con el temor de dejar a sus hijos, pensando que tal vez los detengan.” – Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Cuando conduzco, y [mi hijo] ve a un policía, empieza a ponerse realmente nervioso, está muy nervioso.” – Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“Las escuelas nos han enviado notas diciendo que no deberíamos preocuparnos… y que no deberíamos temer enviar a los niños a la escuela.” – Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“…cuando, en la comunidad latina, hay un mensaje a la comunidad que ICE está haciendo, está haciendo redadas, luego todos se detienen, dejan de enviar a sus hijos a la escuela y dejan de venir a la clínica.” –Pediatria, California

Muchos participantes dijeron que es más difícil encontrar empleo en el entorno actual, lo que agrava los problemas financieros. Un número consideró que las opciones de empleo se habían vuelto más limitadas desde las elecciones presidenciales. Señalaron que hay menos permisos de trabajo disponibles y que los permisos no se están renovando. Algunos también dijeron que el aumento de los procedimientos de verificación por parte de los empleadores está causando que algunas personas pierdan sus empleos, a veces trabajos que han tenido durante muchos años. Ante estos desafíos, los participantes dijeron que a menudo tienen que salir de sus barrios o comunidades y/o viajar grandes distancias para encontrar trabajo, lo que aumenta el tiempo y los costos de traslado y dificulta el cuidado infantil. En algunos casos, las personas ya no buscan trabajo porque temen exponerse a las autoridades. De manera similar, algunos padres en Maryland dijeron que temen ser voluntarios en las escuelas de sus hijos porque las escuelas requieren que los padres voluntarios presenten documentación y se sometan a una verificación de antecedentes.

“En este momento, en su mayoría, no están dando permisos; ellos quieren que nos vayamos. Entonces cuando no tenemos permiso de trabajo, nadie nos contrata.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“La situación laboral es cada vez más difícil … si saben que no tienes documentos … empiezan a cuestionar por qué trabajas allí …” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Es más difícil encontrar trabajo, y nos levantamos todos los días con el temor de ser deportados, de separarnos de nuestras familias, de tener que dejar a los niños.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Me gustaría encontrar otro trabajo, y es difícil poder buscar trabajo porque no sientes el mismo tipo de confianza o seguridad que tuviste en años anteriores cuando simplemente ibas y dejabas tu información.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Muchas veces no trabajo… porque siento que estoy más segura aquí en mi casa. Y a veces lo que gana mi marido no es suficiente y por eso debes limitarte en muchas cosas.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Porque estaba trabajando en una empresa que era más o menos grande… y tuve que irme, porque me dijeron que iban a verificar nuestra documentación.” –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

Algunos padres han organizado el cuidado de sus hijos en caso que los detengan o deporten, mientras que otros están inseguros y temerosos sobre lo que les pasaría a sus hijos. Algunos padres han preparado poderes notariados para autorizar a miembros de la familia o amigos a convertirse en guardianes de sus hijos en caso de detención o deportación. Algunos también informaron haber recibido solicitudes de vecinos, familiares y/o amigos para convertirse en guardianes de sus hijos. Sin embargo, otros padres dijeron que no saben quién cuidaría de sus hijos si fueran detenidos o deportados y/o que no tienen amigos o familiares aquí en los Estados Unidos a los que puedan pedir ayuda. Un pediatra señaló que algunos padres preguntaban si podían designar al hospital de niños como guardián para niños con necesidades complejas porque no tenían a nadie más que pudiera proporcionar el nivel de atención que necesitan sus hijos.

Efectos en la salud y el bienestar de los niños

El aumento del miedo entre los niños se manifiesta de muchas maneras, incluidos problemas de conducta, síntomas psicosomáticos y problemas de salud mental. Los padres y los pediatras informaron que los temores están contribuyendo a problemas de comportamiento entre los niños, incluidos problemas para dormir y comer, regresión, aumento de la inquietud y agitación, y alejamiento de familiares y amigos. Los niños también experimentan síntomas psicosomáticos, como dolores de cabeza, estómago, náuseas y vómitos. Además, los padres y pediatras indicaron que algunos niños experimentan ansiedad, tienen ataques de pánico, muestran síntomas de depresión y/o expresan una pérdida general de esperanza en el futuro. Por ejemplo, un pediatra contó cómo un niño cuyo padre había sido deportado comenzó a tener ataques de pánico porque temía perder también a su madre y que lo pusieran en cuidado temporal. Otro pediatra señaló que, después de las elecciones, el “miedo a Trump” surgió como una queja principal en su agenda diaria.

“…no expresan cómo se sienten, solo intentan mantenerse cerca de mamá, para que no se vaya. Si va a algún lado, entonces van con ella …” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“El mío tiene 6. No estoy seguro de si se da cuenta de lo que está pasando, pero se asusta cuando le digo que voy a viajar. Me dice que no vaya porque dice que no volveré, que no volverá a verme.” –Padre que habla portugués, Boston, Massachusetts

“…iría a la biblioteca, iríamos en el autobús, pero ella dijo, ‘si vamos a la biblioteca, la inmigración te llevará, no vayamos’. Y así me mostró que su miedo es tan grande que preferiría simplemente no ir a la biblioteca.” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Llegan con una queja física y luego llegamos al fondo, y el fondo es la ansiedad.” –Pediatria, California

“…Pero perder … ese apoyo, ese tipo de apoyo emocional y financiero ha sido realmente difícil. Esas son las familias que diría probablemente cuando se trata de problemas de salud mental, donde lo veo más intensamente, donde es … más dramático en términos del cambio, el cambio en el niño ya sea más retraído o actuando más extraño, o estando más ansioso…” –Pediatria, District of Columbia

“Ayudamos a muchos niños y padres con problemas para dormir. Tuvimos muchos niños que lloraban y tal vez tuvieron algunos comportamientos regresivos.” –Pediatria, Vermont

“Entonces puedes ver algunas regresiones en su desarrollo. Tal vez estaban entrenados para ir al baño antes y ahora no, tal vez ya no mojaban la cama por la noche y de repente la mojan, tal vez están más pegotes de lo que estaban…” –Pediatria, Texas

“…Así que los niños que podrían tener algún tipo de síntomas inespecíficos como dolor de estómago o dolores de cabeza. Y luego, cuando hablas con ellos, es porque están realmente preocupados por su familia y sus padres, y lo que les vaya a pasar.” –Pediatria, Pennsylvania

“Los niños que vienen con inquietudes en los que se puede rastrear ansiedad suelen ser los estudiantes de los grados superiores de la primaria, 3°, 4° grado, estudiantes de la escuela media… de 7° y 8° grado, que tienen quejas inespecíficas como dolor anormal o dolores de cabeza o disminución del apetito… Y luego, en niños que están en la secundaria para el rango de edad de la escuela secundaria, es un poco más amplio: tristeza, disminución del apetito, no querer participar en actividades habituales, disminución del rendimiento en la escuela, ese tipo de cosas.” –Pediatria, Arkansas

Los padres y pediatras expresaron su preocupación que el aumento del miedo y el estrés esté afectando negativamente el rendimiento escolar de algunos niños. Los padres y los pediatras dijeron que algunos niños tienen cada vez más dificultades para prestar atención en la escuela debido a su estrés y la preocupación de perder potencialmente a sus padres. Un par de pediatras notaron un aumento en los informes escolares de trastorno por déficit de atención/hiperactividad (TDAH), que, creen, pueden ser problemas de atención derivados del miedo o la ansiedad. Otros notaron que algunos niños están teniendo problemas de comportamiento que están interfiriendo con su desempeño en la escuela. Por ejemplo, uno de los padres notó que su hijo recientemente tuvo problemas en la escuela como resultado de enfrentarse a otros estudiantes que intimidaban a otros niños hispanohablantes.

“Sus calificaciones disminuyen, no van a la escuela con el mismo entusiasmo que antes. Van a la escuela con miedo a no encontrar a sus padres cuando vuelvan …” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Comienzan a empeorar en la escuela o tienen problemas de conducta en la escuela.” –Pediatria, Texas

“…así que tiende a ser que los niños no están interesados ya sea en terminar las tareas o en hacer otro trabajo, porque están enfocados en lo siguiente que les sucederá a sus padres, que están pasando por un procedimiento.” –Pediatria, Arkansas

El aumento de los temores también ha afectado el bienestar de los padres y les ha dificultado concentrarse en el cuidado. Varios padres informaron que también están sufriendo un aumento de la ansiedad y/o depresión debido a sus miedos. Algunos informaron problemas para dormir y comer, así como dolores de cabeza y náuseas productos del estrés y la preocupación. Algunos pediatras indicaron que, en algunos casos, estos temores han servido como desencadenantes para los padres que tienen antecedentes de trauma o persecución, que conducen a la depresión y/o ansiedad. Los pediatras también notaron que, a medida que los padres experimentan un aumento en el estrés y la ansiedad, pueden tener más dificultades para concentrarse en el cuidado y/o alejarse más de sus hijos. Algunos pediatras informaron preocupaciones sobre las tensiones en las relaciones familiares, particularmente cuando los miembros de la familia tienen diferentes estatus migratorios. Por ejemplo, un hermano menor en la familia puede ser un ciudadano nacido en los Estados Unidos, mientras que un hermano mayor puede ser indocumentado o ser recipiente de DACA.

“Tuve muchas pesadillas. A menudo soñaba que la inmigración vendría y lloraba mucho. Me despertaba temblando…” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“Y me deprimí, no tenía hambre, no podía dormir, temía salir”. Yo lloraba a veces. No tuve hambre durante varios días, era como si estuviera deprimido.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“Dolores de cabeza de pensar tanto porque solo piensas en lo que va a pasar”. Piensas en el futuro; ¿Qué pasa si esto sucede, qué voy a hacer??” –Padre latino, Bethesda, Maryland

“Creo que la ansiedad paralizaría a la gente y no podrían ser padres. No podrían funcionar, algunas personas, porque estaban tan abrumados y ansiosos; no podía ir a trabajar, no podía salir de su casa …” –Pediatria, Vermont

Efectos en el uso de la atención de salud

La mayoría de los padres indicaron que no han realizado ningún cambio en la forma en que buscan la atención médica para sus hijos en respuesta a un aumento de los temores; sin embargo, algunos padres y pediatras describieron cambios en el uso de la atención médica. La mayoría de los padres señalaron que continúan buscando atención médica para sus hijos y que confían en sus médicos actuales, y consideran que los consultorios y hospitales son espacios seguros. También notaron que priorizan la búsqueda de atención médica para sus hijos por sobre sus miedos. Los pediatras también informaron que, en general, los pacientes siguen recibiendo atención. Sin embargo, algunos padres y pediatras reportaron disminuciones en las visitas y/o cambios en el horario de las visitas. Por ejemplo, algunos pediatras han observado una baja en las citas de niños sanos, en los seguimientos de derivaciones con proveedores con los que las familias no tienen una relación existente y en las mujeres embarazadas que buscan atención prenatal. Un pediatra también informó que algunos padres ya no abren sus puertas o no atienden llamados para consultas de salud en el hogar. Otro pediatra consideró que los padres habían cambiado de utilizar las visitas programadas a las visitas sin cita porque pueden dudar en proporcionar información para programar la cita. En Boston, algunos padres dijeron que tratan de programar las citas de sus hijos por la mañana porque sienten que ese es el momento más seguro para estar afuera. Además, un pediatra informó que los padres están agrupando visitas para minimizar la frecuencia de visitas y limitar su tiempo fuera del hogar. En Fresno, algunos padres dijeron que, en el entorno actual, prefieren utilizar proveedores latinos.

“El caso es… si estás en el hospital estás a salvo. No pueden ingresar a un hospital, una escuela o una iglesia… porque es un santuario.” –Padre latino, Chicago, Illinois

“…tienes que elegir un médico… que sea más hispano… como están las cosas ahora con la inmigración …” –Padre latino, Fresno, California

“Ahora intento hacer mis citas más temprano en la mañana para no quedarme demasiado tiempo afuera. Por lo tanto, trato de hacer esto temprano y luego me quedo tranquilo en casa.” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“…Hemos tenido familias… en particular, aquellas familias de grandes necesidades; diciendo cosas … como ‘bueno, tengo estas tres citas con especialistas que tenemos que hacer. Vamos a hacerlos el mismo día’, … porque les preocupa estar… en público con frecuencia y con el riesgo de ser detenidos.” –Pediatria, District of Columbia

“Creo que lo más sorprendente es que nuestros trabajadores de salud en el hogar se daban cuenta que cuando llamaban a las puertas, las personas no respondían …” –Pediatria, Minnesota

“…También hemos visto familias haciendo cambios significativos en el acceso a la atención debido a las preocupaciones sobre el estatus migratorio. Entonces, las familias cuyos hijos necesitan ver a especialistas que retrasaban esas citas especiales porque no se sentían cómodos saliendo de su casa o de su barrio donde se sentían seguros.” –Pediatria, Pennsylvania

Los pediatras describieron algunas acciones que están tomando para ayudar a las familias a sentirse seguras. Los pediatras informaron que colocaron letreros en sus consultorios para comunicarles a las familias que sus hijos son bienvenidos y que están seguros. Uno observó que han puesto al personal bilingüe fuera de la entrada para recibir a las familias y asegurarse de que no encuentren ninguna dificultad al ingresar a la clínica. Algunos indicaron que están tomando medidas para asegurar a las familias que mantendrán la confidencialidad de su información, de modo que se sientan cómodas hablando de cuestiones relacionadas con la inmigración durante las visitas de atención médica. Un número dijo que han capacitado al personal para destacar la importancia de la confidencialidad y las mejores prácticas para discutir temas delicados como el estado de inmigración. Dos pediatras también indicaron que sus prácticas habían desarrollado protocolos operativos para que el personal supiera qué pasos tomar si oficiales de inmigración entraban al consultorio. Algunos pediatras dijeron que han organizado eventos o proporcionado referencias para ayudar a las familias a entender sus derechos y a planificar en caso que sean detenidos o deportados. Muchos pediatras también informaron que escribieron cartas para ayudar a las familias involucradas en los procedimientos de deportación.

“…Colocamos carteles en toda la oficina indicando que son bienvenidos o todos son bienvenidos… Tenemos letreros en la entrada… que no discriminamos por status migratorio y que los refugiados e inmigrantes son bienvenidos en nuestra oficina … Y eso es algo que implementamos después de las elecciones…” –Pediatria, Chicago

“…Creamos un prendedor que dice ‘todos son bienvenidos’. Fue realmente un gran esfuerzo hacerlos… declaraciones generales que los niños eran bienvenidos … que la comunidad los estaba apoyando … y creo que eso ayudó a las familias refugiadas a sentir que la comunidad las apoyaría…” –Pediatria, Vermont

“Así que hemos visto un gran aumento en el número de personas que están pidiendo cartas solo para tenerlas, ya sea por razones de seguridad o para dárselas a un abogado o algo así.” –Pediatria, Arkansas

Algunos pediatras expresaron su preocupación acerca de la ambigüedad de las fronteras en torno a los espacios seguros y la incertidumbre sobre cómo aconsejar a las familias en medio del entorno actual. Por ejemplo, un pediatra indicó que, si bien el hospital en sí mismo puede ser un lugar seguro, no está claro hasta dónde se extiende ese límite y si la protección llega al estacionamiento. Un pediatra señaló que los consultorios cerca de la frontera entre los Estados Unidos y México informan una mayor presencia de patrullas fronterizas en estacionamientos de clínicas y dijo que su presencia disuade a los padres de llevar a sus hijos a atenderse. Además, algunos pediatras destacaron los desafíos al desarrollar políticas y protocolos para el personal en asuntos relacionados con la inmigración debido a que el ambiente cambia constantemente.

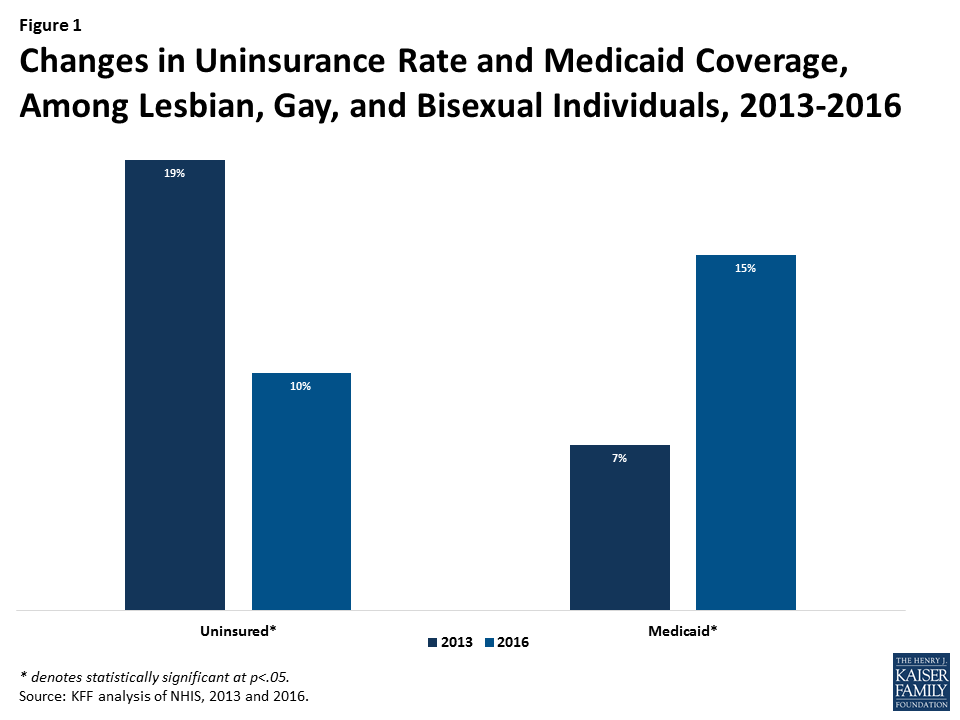

Efectos sobre la participación en Medicaid/chip y otros programas

Los padres generalmente informaron que mantienen la cobertura de Medicaid y CHIP para sus hijos, pero hubo algunos informes de una menor participación éstos y otros programas. La mayoría de los participantes tienen a sus hijos inscriptos en Medicaid y CHIP y dijeron que tienen la intención de mantenerlos inscriptos. Los padres dijeron que valoran mucho la cobertura de Medicaid y CHIP, que les permite acceder a la atención necesaria para sus hijos. Sin embargo, algunos padres y pediatras informaron que algunas familias con niños elegibles están menos interesadas en inscribirse en Medicaid y CHIP. Además, una clínica señaló que algunos pacientes solicitaron que se cancelara su inscripción porque temen que puedan poner en riesgo a miembros de la familia indocumentados o poner en peligro el estado legal de los miembros de la familia. Los pediatras dijeron que han observado disminuciones más pronunciadas en la participación en el programa de nutrición para mujeres, bebés y niños (WIC) y el Programa de Asistencia de Nutrición Suplementaria (SNAP). Creen que es más probable que los padres vean WIC y SNAP como programas federales que podrían exponer su información a las autoridades. Los padres y los pediatras también notaron preocupaciones constantes en la comunidad sobre que el uso de Medicaid, CHIP y otros programas afectarán negativamente el estatus migratorio de las personas con estatus legal o que buscan residencia o ciudadanía. Los participantes consideraron que sería útil si las fuentes oficiales proporcionaran más información sobre cómo el uso de los beneficios podría afectar el estatus migratorio de las familias. Algunos pediatras indicaron que no están seguros de cómo aconsejar a las familias sobre el uso de los beneficios y la inscripción en los programas, ya que las políticas podrían cambiar. Por ejemplo, un pediatra indicó que es más cautelosa al alentar a las familias a inscribirse en SNAP porque hacerlo podría tener consecuencias negativas si cambian las políticas.

“Personalmente, tengo miedo de tratar de obtener mi MassHealth [Medicaid] o algo de nuevo, debido a mi permiso … Están solicitando muchos documentos …” –Padre latino, Boston, Massachusetts

“…también le piden toda su información e ICE irá a su casa y esa es la razón por la que aún no aplica, porque están pidiendo toda la información sobre todos, sus cónyuges, sus hijos.” -Padre latino, San Diego, California

“…desde que me hice residente me dijeron que no pidiera nada al gobierno porque el día que vas y pides tu ciudadanía puedes tener problemas. Eso es lo que siempre escuché.” –Padre latino, San Diego, California

“He oído sobre los cupones de alimentos, que si consigues que el gobierno te ayude, va a afectar tu estatus.” –Padre latino, Los Angeles, California

“Empecé a escuchar… preguntas sobre si deben o no acceder a los servicios… Entonces, algunas madres primerizas con recién nacidos preguntan si deberían inscribir a su hijo que es ciudadano de los Estados Unidos. Y nació aquí en este país, si deberían inscribir a su hijo en WIC. E, incluso, en algunas circunstancias, decidieron no presentar la solicitud aunque hubieran calificado…” –Pediatria, District of Columbia

“Lo que están haciendo cada vez más las familias es no recibir cupones de alimentos, no tomar WIC, no querer tomar los servicios federales porque tienen miedo …” –Pediatria, Vermont

“No hemos visto una caída entre las familias que ya están inscritas, pero hemos visto familias que no habían aplicado anteriormente y deciden no seguir adelante [con la inscripción en Medicaid o CHIP].” —Pediatria, Minnesota

“…Me he dado cuenta que cada vez más personas que antes no tenían miedo de recibir… servicios como SNAP, por ejemplo, están muy nerviosos por eso. Y entonces tuve dos familias la semana pasada que no querían obtener esos servicios aunque los necesitaran… y luego una familia que estaba nerviosa incluso por volver a solicitar Medicaid, porque… pensaron que pondría en peligro la capacidad del padre para obtener una visa.” –Pediatria, California

“…Yo personalmente no los aliento de la misma manera, mientras que antes tenía mucha más confianza al decir, ‘esto no es un problema para ti, no te preocupes, si inscribes a tu hijo que nació aquí, no te afectará para nada’. No sé si eso es verdad, así que no puedo, ya no digo eso con esa confianza.” –Pediatria, California

La mayoría de los padres participantes no tienen seguro y dicen que se retrasan o no reciben atención médica debido al costo. Aquellos que son indocumentados no son elegibles para Medicaid y generalmente no tienen acceso a cobertura privada. Principalmente dependen de clínicas, pero a menudo evitan buscar atención debido al costo. Los padres con estatus legal tenían más probabilidades de tener cobertura, a menudo a través de Medicaid, y podían acceder mejor a la atención necesaria.

Implicaciones de largo plazo para los niños

Los pediatras expresaron una preocupación significativa sobre las consecuencias a largo plazo del ambiente actual para los niños. Señalaron una investigación de larga data sobre los efectos dañinos del estrés tóxico sobre la salud física y mental a lo largo de la vida (Cuadro 1). Creen que el entorno actual está creando estrés tóxico para los niños y que este estrés dará lugar a cambios fisiológicos que contribuyen a un aumento de las tasas de enfermedades crónicas y trastornos de salud mental hasta la edad adulta. Un pediatra que atiende a familias cerca de la frontera con México señaló que el estrés para los niños en ese medio ambiente es extremo, particularmente debido a la presencia visual constante de la patrulla fronteriza y la militarización del área, que según indicó, ha aumentado desde las elecciones presidenciales. Los pediatras expresaron su preocupación que las disminuciones en la participación en WIC y SNAP afectarán negativamente el desarrollo saludable de los niños. De manera similar, advirtieron que las reducciones en el uso de la atención médica podrían generar condiciones más serias y costosas. Algunos pediatras expresaron su preocupación que la mayor cantidad de tiempo que las familias pasan a puertas cerradas comprometerá el desarrollo de los niños y reducirá sus oportunidades de enriquecimiento y actividad física. Los pediatras también enfatizaron que la pérdida de un padre debido a la deportación afecta negativamente la salud y el desarrollo de los niños de múltiples maneras, incluida la pérdida de apoyo económico y social, y la interrupción del vínculo entre padres e hijos.

“No quiero que estos niños vayan a la escuela ansiosos y deprimidos y no puedan concentrarse, pero también me preocupa lo que le está haciendo al corazón y al hígado.” –Pediatria, District of Columbia

“Cuando te preocupas todos los días por que se lleven a tus padres o que tu familia se divida, que realmente es una forma de estrés tóxico… sabemos que tendrá implicaciones a largo plazo para la enfermedad cardíaca, para los resultados de salud para estos niños en la edad adulta.” –Pediatria, Minnesota

“Creo que vamos a tener una generación de niños que, especialmente en nuestros hogares de inmigrantes, van a tener más experiencias infantiles adversas de las que tendrían. Por lo tanto, creo que estamos creando esta generación de niños para que tengan una mayor incidencia de enfermedades crónicas, mayor incidencia de mala salud mental, mayor incidencia de adicciones…” –Pediatria, California

“Creo que una gran preocupación es que los niños que tienen problemas que son menores y reparables ahora… eso, si esos niños no reciben tratamiento, podrían terminar siendo problemas mayores en el futuro que serán más difíciles de tratar y realmente van a afectar la calidad de vida del niño.” –Pediatria, Pennsylvania

“Creo que esa es una de las cosas que más me preocupan, desde un punto de vista de la exposición desde hace mucho tiempo, es que los niños pierden la oportunidad de tener cualquier tipo de experiencias de enriquecimiento porque las familias tienen miedo de hacer cualquier cosa que no sea esencial. Así que creo que es cierto, especialmente en el verano donde cuidamos a muchas de las familias, los niños estaban en casa viendo televisión todo el día porque los padres se sentían incómodos al salir de la casa…” –Pediatria, North Carolina

“Si tus padres temen ir a trabajar, entonces tienes problemas de inseguridad alimentaria. Si no se registran para obtener diferentes beneficios y tienes problemas de inseguridad alimentaria… quiero decir, creo que esto afecta a los niños en tantas, tantas formas que ni siquiera podemos entender. Entonces tenemos niños que tienen hambre, los niños que tienen hambre no pueden aprender. Tenemos niños que están estresados, los niños que están estresados no pueden aprender. Tenemos niños que están en familias necesitadas o tienen padres que están angustiados… están preocupados por sus padres, no pueden aprender. No pueden ser niños normales. No pueden jugar. No pueden desarrollarse. No pueden crecer.” –Pediatria, Vermont

Box 1: Investigación sobre los efectos del estrés tóxico en el aprendizaje, la conducta y la salud

El estrés tóxico puede afectar de manera negativa el desarrollo físico, cognitivo y emocional de un niño. Cuando los niños experimentan estrés continuo y prolongado, conocido como “estrés tóxico”, puede dañar las conexiones en el cerebro, resultando en problemas con el desarrollo del cerebro y efectos negativos de largo plazo en la salud física y mental.

Un cuerpo creciente de literatura encuentra que la amenaza de la detención y deportación de los padres es un estrés tóxico6 . Los niños que viven con la amenaza constante de la deportación de sus padres pueden tener un constante y elevado estado de ansiedad que no permite que el cuerpo vuelva a su funcionamiento basal. La American Academy of Pediatrics recientemente advirtió que el estrés de vivir con miedo a la deportación entre los niños inmigrantes podría interrumpir los procesos de desarrollo del niño y conducir a problemas de salud a largo plazo.7

La investigación muestra que el estrés tóxico tiene efectos en la salud física, mental y del comportamiento a corto y largo plazo8 . A corto plazo, el estrés tóxico puede aumentar el riesgo y la frecuencia de las infecciones en niños, ya que los altos niveles de hormonas del estrés suprimen al sistema inmune. También puede provocar problemas de desarrollo debido a la reducción de las conexiones neuronales en áreas importantes del cerebro. El estrés tóxico está asociado con el daño a las áreas del cerebro responsables del aprendizaje y la memoria. A largo plazo, el estrés tóxico se puede manifestar como una mala capacidad de afrontar y manejar el estrés, estilos de vida poco saludables, adopción de conductas de salud riesgosas y problemas de salud mental, como depresión. El estrés tóxico también se asocia con mayores tasas de afecciones físicas en la edad adulta, que incluyen enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica, obesidad, cardiopatía isquémica, diabetes, asma, cáncer y trastorno de estrés postraumático.

Los pediatras y los padres describieron cómo la deportación y la revocación de DACA constituyen un desafío para las familias y aumentan el riesgo de pobreza cíclica. Los pediatras y los padres señalaron que perder a un miembro de la familia por deportación a menudo resulta en la pérdida del ingreso familiar, lo que lleva a tensiones financieras y, a veces, a la inseguridad alimentaria y de la vivienda. Un pediatra observó un aumento en la falta de vivienda entre los niños debido a la pérdida de miembros de la familia y los ingresos. Los pediatras dijeron que estas pérdidas de ingresos aumentarán la probabilidad de pobreza cíclica entre las familias. También notaron que muchos jóvenes con DACA estaban buscando educación y carreras que pudieran sacar a sus familias de la pobreza y que esta oportunidad se pierde con la revocación de DACA. Han observado que algunos adolescentes, especialmente aquellos que son indocumentados o que tienen DACA, han perdido la esperanza en el futuro y están reconsiderando los planes para asistir a la universidad o buscar ciertas oportunidades laborales. Dijeron que esta pérdida de esperanza y perspectivas negativas para el futuro podrían afectar sus elecciones de vida y limitar sus logros potenciales y ganancias económicas. Los padres y pediatras también expresaron su preocupación que las familias inmigrantes se alienen cada vez más de sus comunidades más amplias como resultado del ambiente actual. A los pediatras les preocupa que esta situación pueda llevar a las familias a sentirse más aisladas y que los niños puedan enfrentar desafíos para construir sus identidades.

“…no solo está estableciendo un riesgo social basado solo en el estatus migratorio, sino que ahora también se basa en todos los demás determinantes sociales de la salud. Así que las familias que viven en una familia monoparental, es decir, uno de los padres fue deportado y son una familia monoparental ahora están en riesgo de pobreza, en riesgo de inequidad educativa, en riesgo de todas estas otras cosas que sabemos que son también experiencias adversas para la infancia, pero luego colocan a los niños en riesgo de efectos a largo plazo.” –Pediatria, North Carolina

“En Brownsville tenemos alrededor de 1,700 escolares que no tienen un hogar. Muchos de esos niños carecen de hogar a causa de un padre que fue deportado o encarcelado.” –Pediatria, Texas

“Muchos de estos niños enfrentarán inseguridad con respecto a la vivienda, la comida, a las necesidades básicas … A largo plazo, la economía y la estabilidad y la angustia emocional …” –Pediatria, Illinois

“Así que creo que hay muchos efectos secundarios… los cambios en el programa DACA no afectan solo al destinatario de DACA, sino a sus padres si están ayudando… a los niños… a sus hermanos, a cualquier otra persona del hogar…” –Pediatria, District of Columbia

“…dependiendo lo que ocurra con el programa DACA, hay tantos niños en nuestra comunidad a los que ayudó, que continuaron hasta la universidad para obtener su título … Creo que sería una pérdida terrible, no solo el estudiante y sus familias, pero para toda la comunidad si el trabajo que pudieron hacer porque obtuvieron DACA se detuviera acá.” –Pediatria, Arkansas

“…Mis hijos nacieron y crecieron aquí y no fue su elección… cuando crezcan, me temo que también podrían estar alienados.” – Padre coreano, Chicago, Illinois

“…No saber si puedes o no quedarte, sentir que no perteneces, no tener un pie adentro, como un dedo del pie en un lugar al que puedas llamar hogar. Me refiero a las implicaciones a largo plazo, creo que está afectando cómo formulan sus identidades.” –Pediatria, Illinois

Conclusión

En conjunto, estos hallazgos muestran que las familias inmigrantes en diferentes entornos y ubicaciones están sintiendo un aumento en los niveles de miedo e incertidumbre en medio del clima actual. Los padres y los niños de familias en las que un miembro es indocumentado temen separarse, y aquéllos con estatus legal se preocupan por la seguridad y la estabilidad de su estatus, y por si pueden verse afectados en el futuro por cambios en la política. Los hallazgos muestran que estos temores tienen efectos amplios en la vida cotidiana y las rutinas de algunas familias inmigrantes que temen abandonar su hogar, lo que limita su participación en actividades, y los confronta con mayores desafíos laborales. Además, señalan las consecuencias a largo plazo para los niños de familias inmigrantes, incluidos peores resultados de salud a lo largo de la vida, crecimiento y desarrollo comprometidos, y mayores desafíos en una variedad de factores sociales y ambientales que influyen en la salud.

Este informe fue preparado por Samantha Artiga y Petry Ubri, de la Kaiser Family Foundation. Las autoras agradecen a Blue Shield of California Foundation por su apoyo con los grupos de discusión y las entrevistas realizadas en California. También agradecen a la American Academy of Pediatrics por su ayuda identificando pediatras para entrevistar para este trabajo. Finalmente, expresan su aprecio profundo a los padres y pediatras que compartieron su tiempo y experiencias para este informe.