Key Facts about Uninsured Adults with Opioid Use Disorder

Data Note

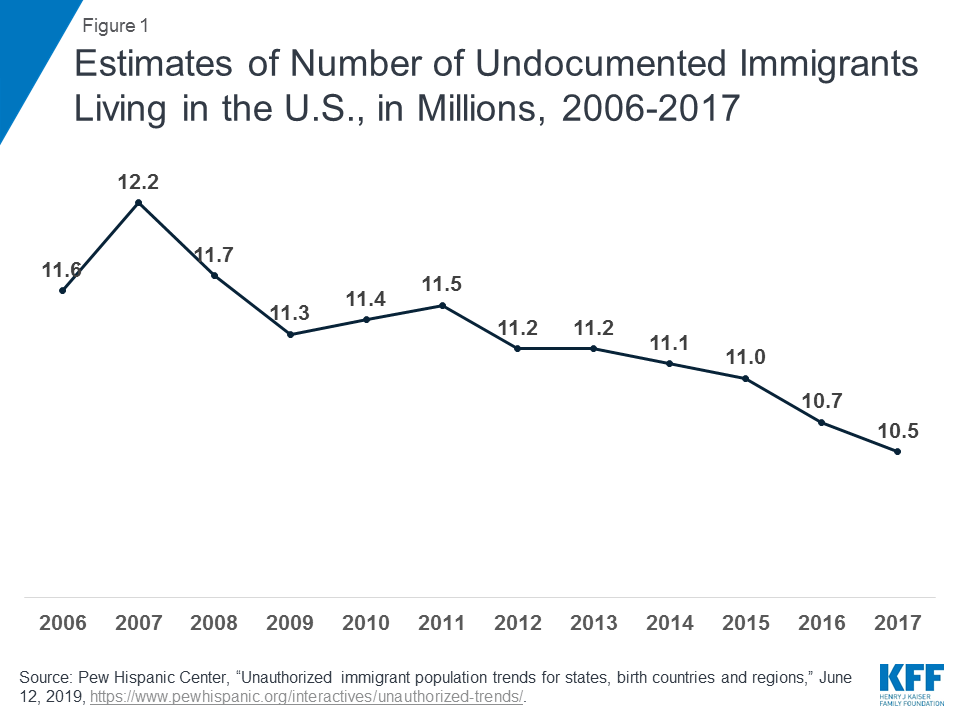

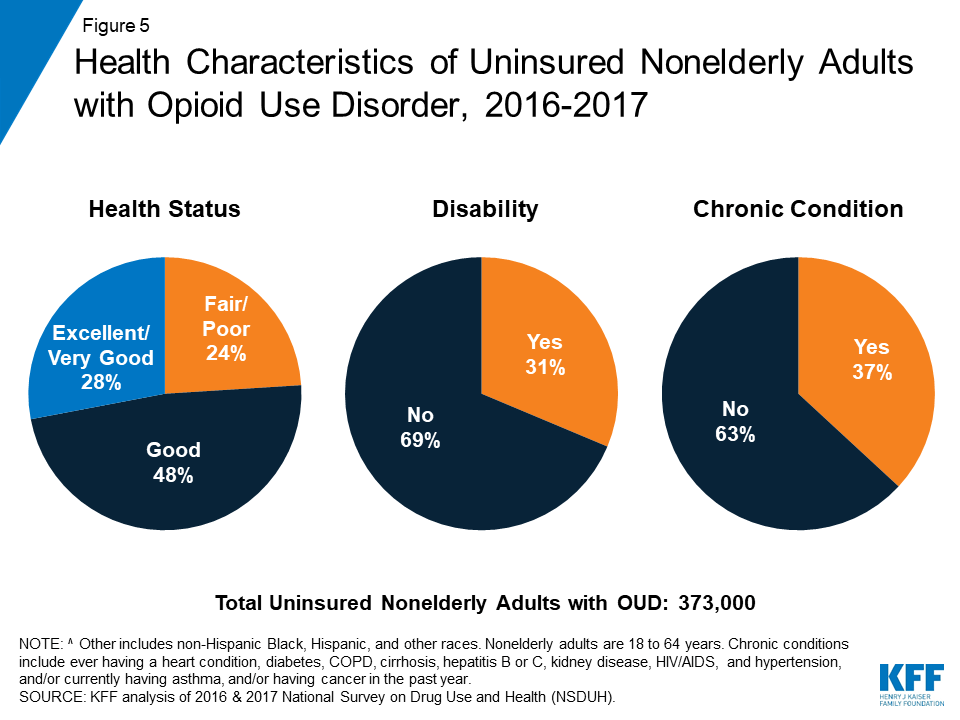

The opioid epidemic continues to devastate many parts of the country, with thousands dying each year from opioid overdoses. The number of deaths is increasing, driven by a spike in overdoses from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids.1 Of the roughly two million nonelderly adults with opioid use disorder (OUD), about a fifth are uninsured. Uninsured adults with OUD are particularly vulnerable because of limited access to treatment and care. Based on data from the 2016 and 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), this data note describes uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD, including their demographic characteristics and treatment utilization.

As the #opioidepidemic continues, nearly 1 in 5 of the 2 million nonelderly adults who have opioid use disorders are uninsured. Evidence indicates that individuals without health coverage are less likely to obtain needed treatments.

Who Are Uninsured Adults with Opioid Use Disorder?

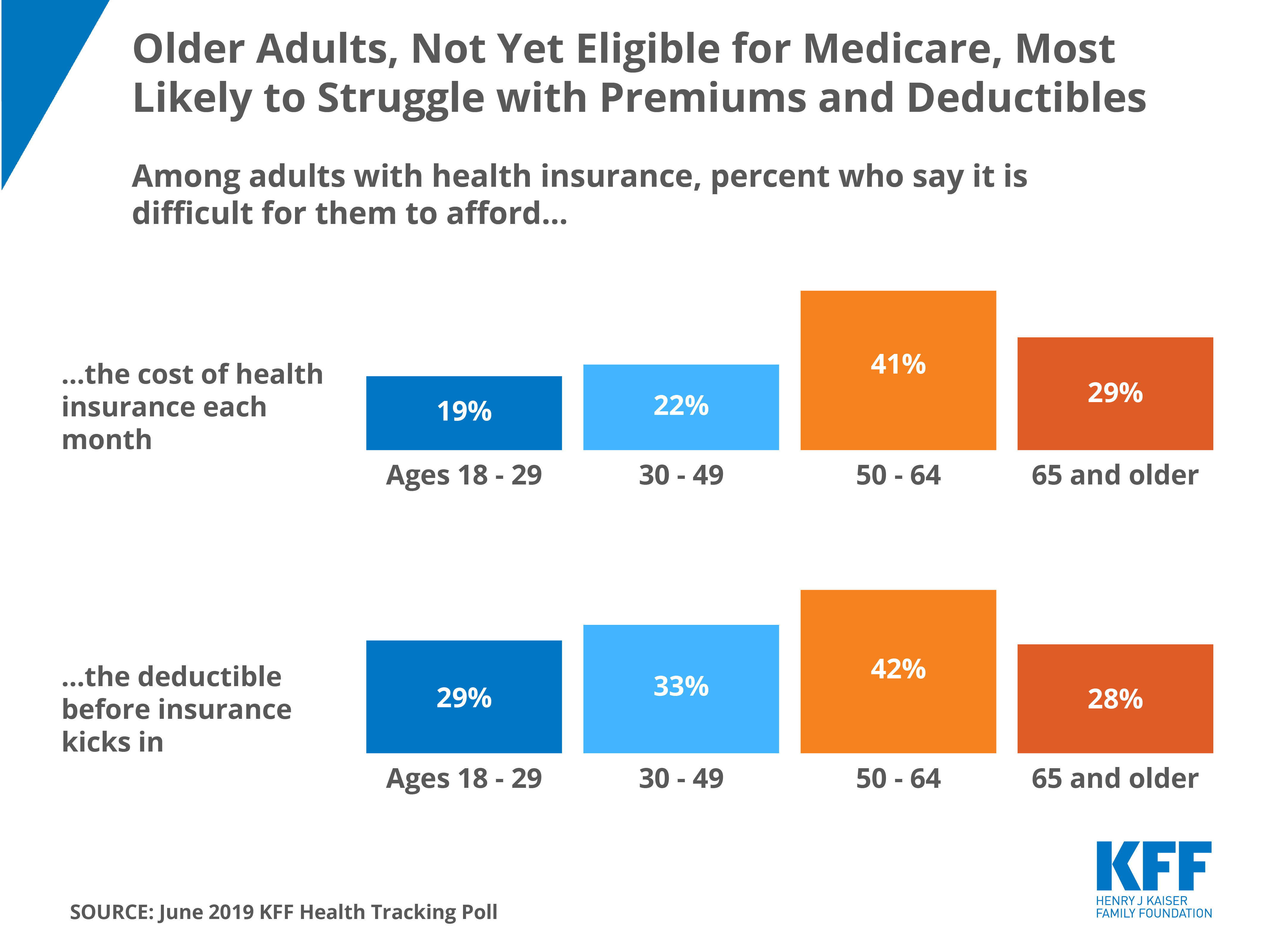

Nearly one-fifth (18%) of nonelderly adults with OUD were uninsured during the period analyzed (Figure 1). Of the two million nonelderly adults with OUD, 373,000 were uninsured. Lacking insurance coverage poses unique challenges to accessing health care services, particularly services for treating substance use disorders. Evidence indicates that individuals without health coverage are less likely to obtain needed treatments that their health care providers recommend for them than those with coverage.2

Uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD were predominantly male, young adult, and white. Nearly seven in ten (67%) of the 373,000 uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD were male and 58% were ages 18 to 34 (Figure 2). Additionally, three-quarters were non-Hispanic white.

The opioid epidemic continues to be driven by misuse of prescription opioids. Among uninsured adults with OUD, nearly two-thirds (65%) reported prescription opioid use disorder3 compared to one in five (21%) who reported heroin use disorder. Another 14% reported using both types of opioids (Figure 3). These percentages were similar to those who had insurance coverage.

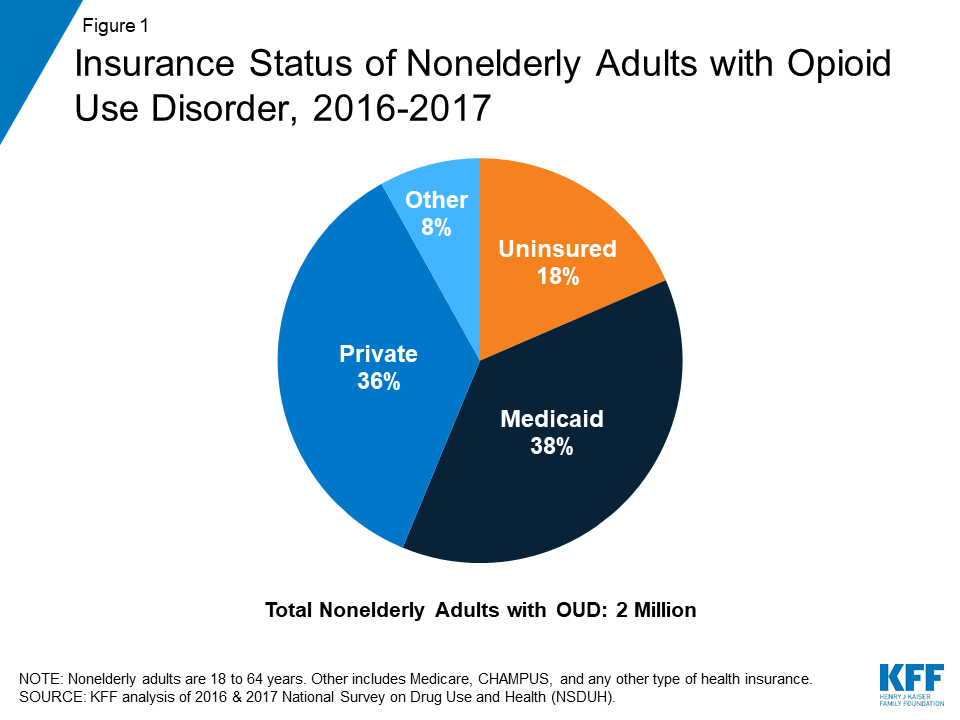

Six in ten of the uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD had low incomes (Figure 4). A quarter of uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD were living in poverty and more than a third (35%) had incomes 100-200% of the Federal Poverty Level ($24,120 for an individual in 2017).

What is the Health Status and Access to Treatment among Uninsured Adults with Opioid Use Disorder?

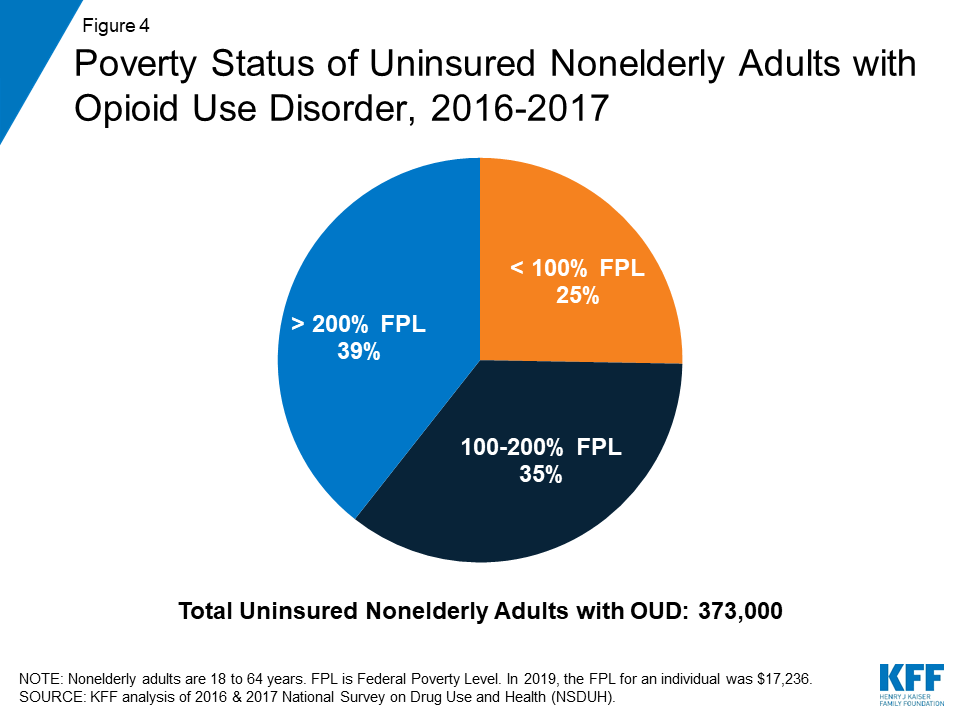

Nearly a quarter of the uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD reported being in fair or poor health (Figure 5). More than three in ten reported having a disability and nearly four in ten (37%) reported having a chronic condition and/or cancer in the past year. Pain management for chronic conditions and cancer can lead to opioid use and ultimately misuse, which is of growing concern for prescribers treating individuals with chronic or severe pain.4 Compared to all uninsured adults, those with OUD are more likely to have a disability or chronic condition (data not shown).

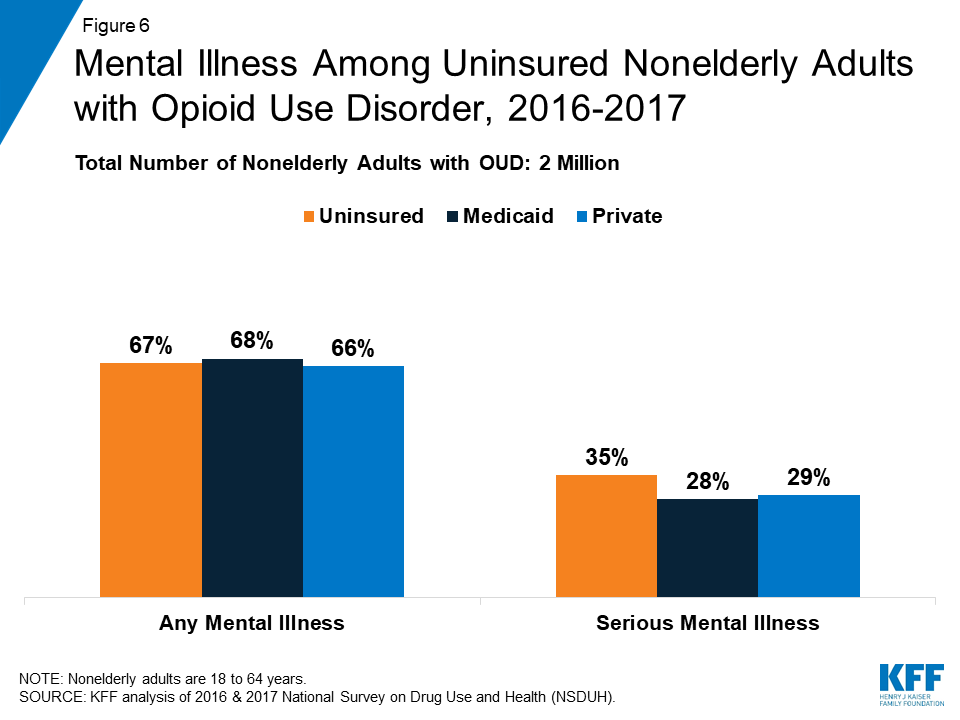

Over two-thirds of uninsured adults with OUD reported any mental illness in the past year. Additionally, more than a third (35%) reported a serious mental illness5 (Figure 6). These rates were similar among nonelderly adults with OUD regardless of insurance coverage.

Fewer than three in ten (28%) uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD reported receiving any treatment in the past year (Figure 7). By comparison, over four in ten nonelderly adults with OUD who had Medicaid and just over one in five of those with private insurance received any treatment. Overall receipt of drug and/or alcohol treatment was low among all nonelderly adults with OUD, with less than a third (31%) reporting they received treatment.

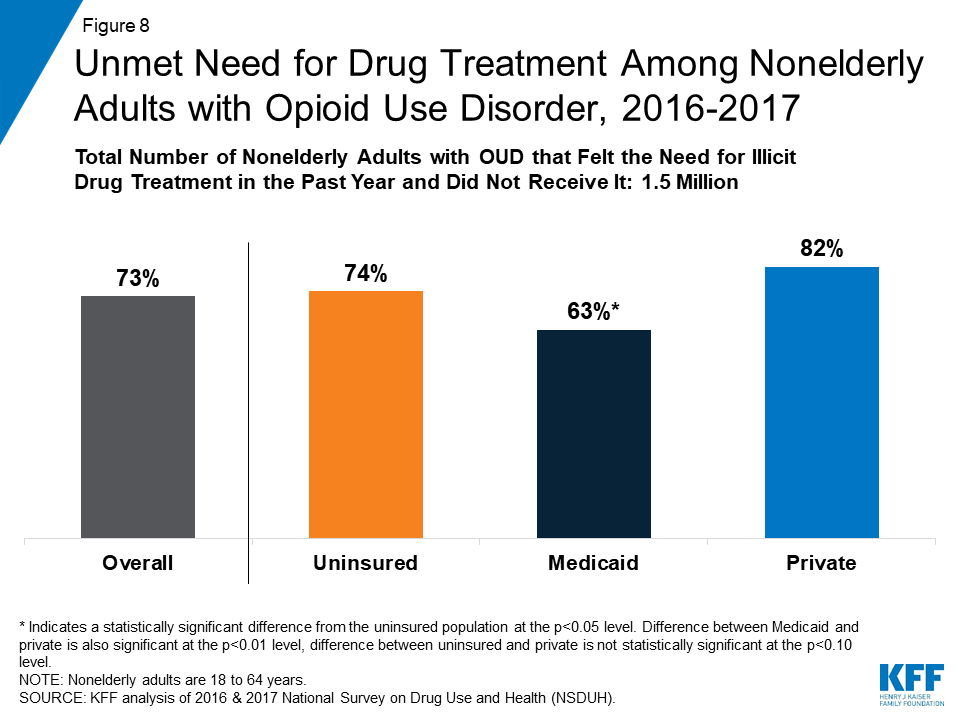

Nearly three-quarters of uninsured adults with OUD reported needing drug treatment in the past year, but did not receive it (Figure 8). Those with Medicaid were least likely to have unmet need for drug treatment, while more than eight in ten (82%) of those with private insurance reported having unmet need in the past year. The reasons for not accessing treatment vary, but common explanations included limited insurance coverage, lack of affordability, concerns about stigma or a negative effect on job, and not being ready to stop using the substance(s).6

Looking Ahead

Uninsured adults with OUD are predominantly male, young adults, and white and many have low incomes. Given the high rates of disability and chronic conditions as well as mental illness in this population, the lack of health insurance may hinder access to needed health care services. Less than a third of uninsured adults with OUD received drug and/or alcohol treatment in the past year. As the number of opioid overdose deaths, particularly due to overdoses from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, continues to increase, uninsured nonelderly adults with OUD are particularly vulnerable. Expanding Medicaid in states that have not yet adopted the expansion could improve access to treatment for many low-income uninsured with OUD.

DATA & METHODS

This analysis is based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2016 and 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Data for 2016 and 2017 were combined to increase the statistical reliability of the estimates; weights were divided by two to account for the two years of data. We included nonelderly adults (age 18 to 64) who reported that they had opioid use disorder in the past year. Adults with opioid use disorder (OUD) were those self-reporting dependence or abuse of heroin or prescription drugs in the past year. Insurance coverage reflected an individual’s coverage as of the point-in-time of the survey. Additionally, because survey respondents may report having more than one type of health insurance coverage, we used a hierarchy to sort each respondent into one category of insurance in the following order: Medicaid; private insurance; other, which consists of Medicare, TRICARE, CHAMPUS, CHAMPVA, VA, and any other coverage; then uninsured.

Endnotes

- Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, “Opioid Overdose Deaths by Type of Opioid,” accessed July 2019, https://modern.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-type-of-opioid/. ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, “The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer, Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the Affordable Care Act,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2019), https://modern.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/. ↩︎

- In this analysis, fentanyl, a common synthetic opioid, is included as a prescription opioid; therefore, the misuse of illicitly manufactured fentanyl may not be fully captured. ↩︎

- Han et al., “Prescription Opioid Use, Misuse, and Use Disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” (Ann Intern Med. 2017; 167(5):293:301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28761945. ↩︎

- Defined as a diagnosable mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of sufficient duration, excluding substance use disorders and developmental disorders, that interferes/limits major life activities (NSDUH Methodological Summary and Definitions, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHMethodSummDefs2017/NSDUHMethodSummDefs2017.pdf). ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 18-5068, NSDUH Series H-53), (Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, September 2018), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.pdf. ↩︎