Overview: 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

Overview

Related Survey Materials

- Women’s Coverage, Access, and Affordability: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

- Women’s Connections to the Healthcare Delivery System: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

- Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Services: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

- Women, Work, and Family Health: Key Findings from the 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey

Health care is a central component of women’s lives, affecting their ability to care for themselves and their families, play a part in their communities, and participate in the workforce and earn a living. Access to comprehensive, affordable, and high quality care is essential for women to address their health care needs – which change across their lifespans. Women’s access to care is shaped by a wide range of factors, including federal and state health care policies. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 marked a significant change in the availability and affordability of coverage and care for millions of formerly uninsured women and men.

The 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey, a nationally-representative survey of women ages 18 to 64 finds that coverage rates for women are at all-time highs and use of preventive services is on the rise, but many women still face a wide range of affordability and other access challenges. This survey is the latest in a periodic series of surveys on women’s health conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation approximately every four years since 2001. The new survey was conducted in the summer and fall of 2017 and included a nationally representative sample of 2,751 women ages 18 to 64. In addition, a shorter survey of 600 men ages 18 to 64 was conducted and key findings are included for comparison. The findings presented in this report examine women’s coverage, access, and affordability of care, their connections to the health care delivery system and use of preventive care, use of reproductive health services, and responsibilities caring for family health needs.

Executive Summary

Introduction

Health care is a central component of women’s lives, affecting their ability to care for themselves and their families, play a part in their communities, and participate in the workforce and earn a living. Access to comprehensive, affordable, and high quality care is essential for women to address their health care needs – which change across their lifespans. Women’s access to care is shaped by a wide range of factors, including federal and state health care policies. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 marked a significant change in the availability and affordability of coverage and care for millions of formerly uninsured women and men. In addition to expanding coverage to more uninsured individuals, the law included provisions to address long-standing insurance practices that were discriminatory and had a disproportionate effect on women. Now all plans must include maternity benefits, are barred from gender rating where women are charged more than men for the same plan, and must cover, without cost sharing, recommended preventive services such as contraceptives.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has conducted the Kaiser Women’s Health Survey approximately every four years since 2001 to provide a look into the range of women’s health care experiences, especially those that are not typically addressed by most surveys. The findings presented in this report examine women’s coverage, access, and affordability of care, their connections to the health care delivery system and use of preventive care, use of reproductive health services, and responsibilities caring for family health needs. The survey was conducted in the summer and fall of 2017 and included a nationally representative sample of 2,751 women ages 18 to 64. In addition, a shorter survey of 600 men ages 18 to 64 was conducted and key findings are included for comparison.

The 2017 survey compares findings to earlier years when possible and highlights differences for uninsured, low-income, and minority women–groups of women that have been historically underserved. Nearly three in ten women ages 18 to 64 live in households that are below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) which was $20,420 for a family of three in 2017. Nearly two in five women identify as racial and ethnic minorities (13% Black, 16% Latina, and 9% Asian or Other) and half are in their childbearing years. A sizable minority of women also report that their health is fair or poor (18%) and over four in ten have a health condition that requires monitoring and treatment (45%). For these women in particular, access to health care is an essential and ongoing concern. Key findings include:

Coverage and Access

The share of women with health coverage has increased since the ACA was implemented, but one in ten women remain uninsured.

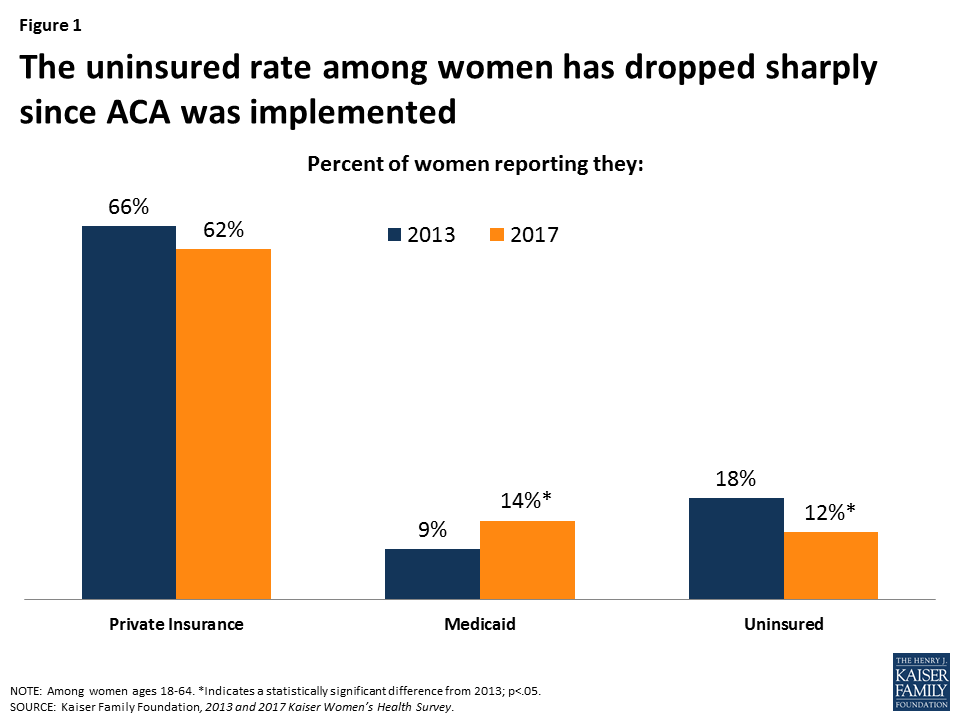

The Kaiser Women’s Health Survey finds that approximately one in ten (12%) non-elderly adult women report being uninsured in 2017, down from 18% in 2013 (Figure 1). An additional 8% of women who were insured at the time of the survey had a lapse in coverage in the prior year. Most women are still insured through a private plan, either employer sponsored or one they bought on their own; however, the greatest increase in coverage occurred through the expansion of the Medicaid program, which now covers 14% of women ages 18 to 64, up from 9% in 2013.

Despite expansions in coverage, many women still experience cost-related barriers to care and face medical bills that force them to make difficult tradeoffs. For some women, logistical problems such as a lack of childcare or difficulty taking time off work pose barriers to care.

Roughly one in four (26%) women report that they delayed or went without care in the prior year due to costs. This rises to half of uninsured women (49%), and is also the case for 25% of women with Medicaid and 21% with private insurance. One in four women report trouble paying medical bills in the last year, and a substantial share say they used up most of their savings or borrowed money to pay off bills. About one in four women report they did not obtain care because they could not find the time (24%) or take time off work (23%) (Figure 2). Some women go without or delay care because of problems with childcare (14%) or transportation (9%). These barriers are more common among low-income women.

Delivery System

Most women have a usual place and provider they go to for care, but uninsured and low-income women have weaker connections to the delivery system.

The vast majority of women say they have a place to go when they need care (83%), have a doctor that they see regularly (79%), and have seen a provider in the past two years (90%). These rates remain consistent since 2013. Uninsured women in general have much weaker connections to the health care system, with about half reporting they have a regular site of care (55%) and clinician (49%). Women who are younger, Latina, or low-income are also less likely to have these connections to the health care system.

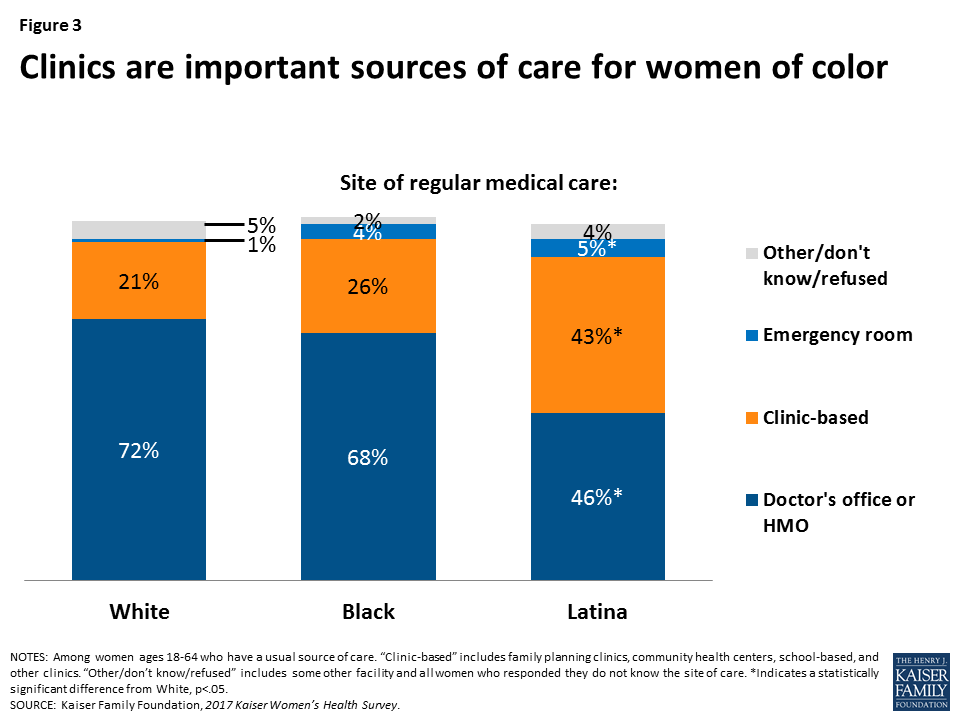

Most women get their care from doctors’ offices, but clinics are particularly important for women of color, low-income women, and the uninsured.

Two-thirds of women who have a usual source of care receive their care at a doctor’s office. A quarter of women seek care at a clinic, such as a community health center. Latina women (43%) and women covered by Medicaid (30%) are more likely to go to a clinic as their usual site of care (Figure 3).

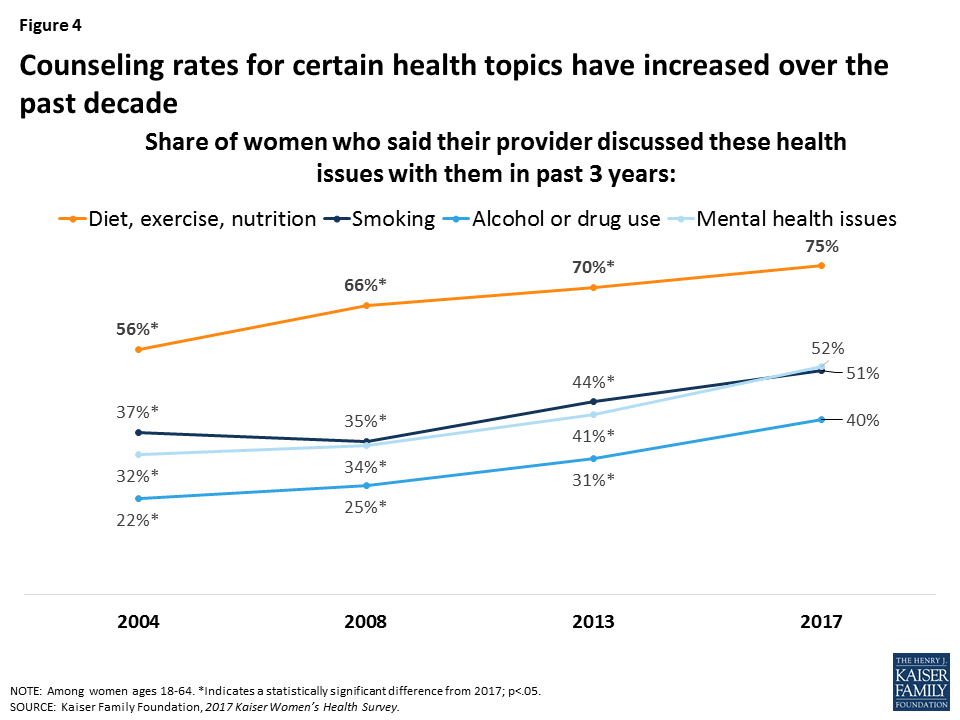

Rates of provider counseling for several health issues such as diet, smoking, and alcohol or drug use have increased over the past several years.

Professional organizations such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend providers discuss a wide range of preventive health topics in the primary care setting, including diet and exercise, alcohol misuse, and smoking. Diet, exercise, and nutrition remains the most frequently discussed health issue, with 75% of women saying a provider has discussed this topic with them in the past three years, up from 56% in 2004 (Figure 4). Rates of provider counseling on other issues are lower, including for smoking (51%), alcohol and drug use (40%), and mental health (52%), but have been rising steadily for more than a decade.

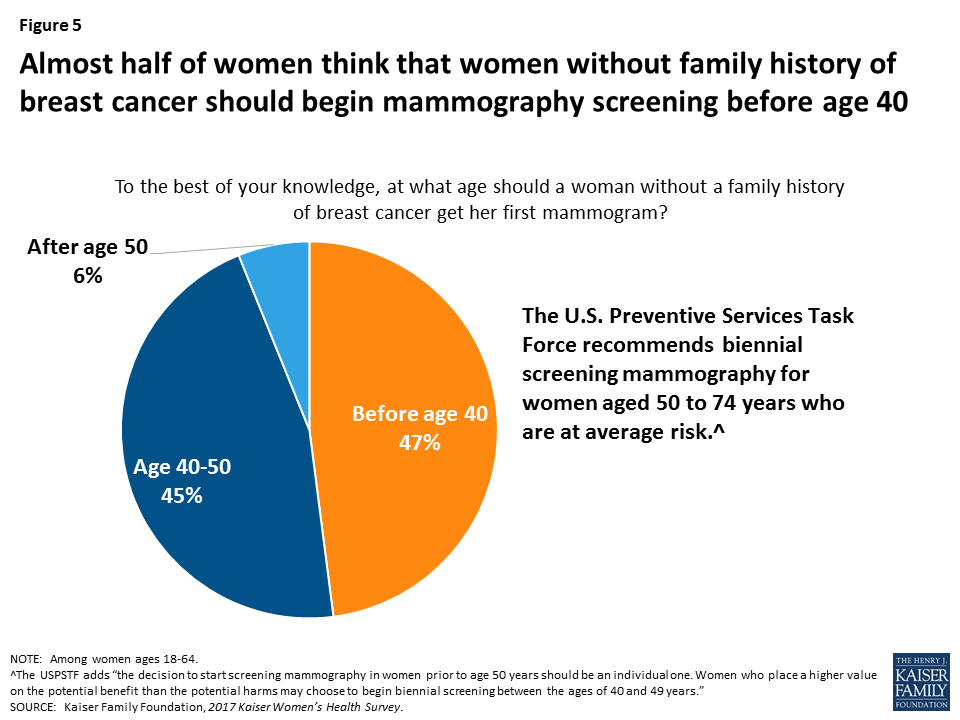

Many women think that women should begin screening tests for breast and cervical cancers at an earlier age than recommended by national groups.

While most women have had cancer screenings in the past two years, including mammograms (71%) and Pap tests (66%), knowledge of national recommendations for cancer screenings is low. Most women (61%) think that a woman should get her first Pap test before the age of 21, and almost half (47%) think that a woman without a family history of breast cancer should get her first mammogram before the age of 40 (Figure 5), even though the USPSTF recommends first Pap test at age 21 and first mammogram for average risk women at age 50.

Reproductive and Sexual Health

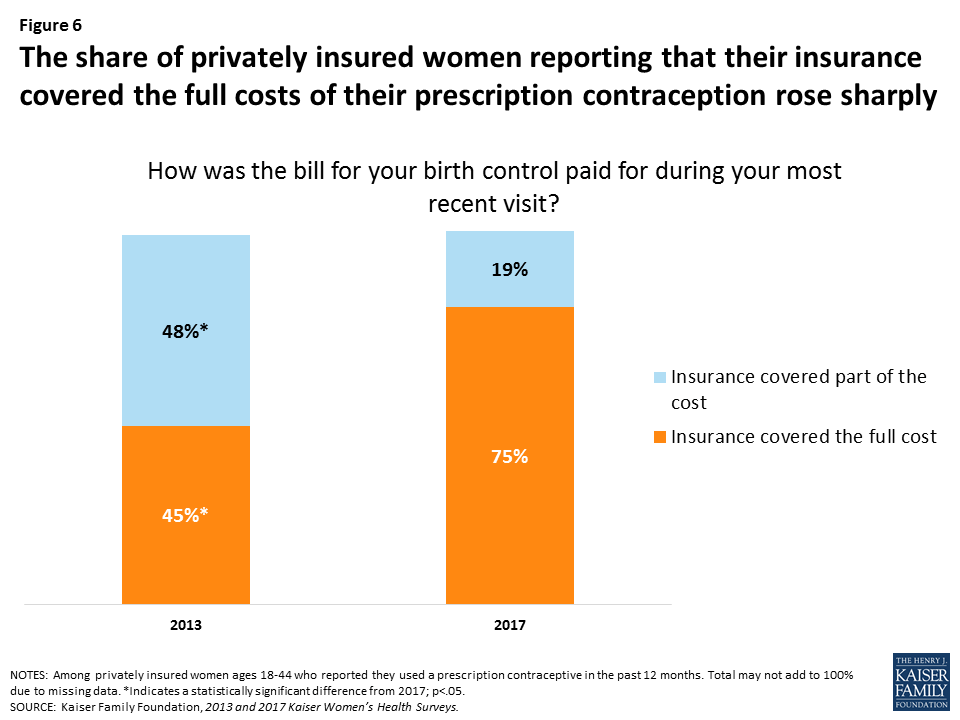

The share of privately insured women who reported that their insurance paid for the full costs of their prescription contraceptives increased significantly since 2013.

The ACA requires most plans to provide no-cost coverage for FDA-approved prescription contraceptive services and supplies for women. In 2017, three-fourths (75%) of privately insured women ages 18-44 who use prescription contraception reported that their insurance fully covered the cost of contraceptives (Figure 6). Another 19% said their insurance paid for part of the costs. This represents a large increase in no-cost contraceptive coverage since 2013, due in part to plans losing their grandfathered status and coming into compliance with the ACA’s contraceptive coverage requirement.

One in five sexually active women report that they are not using contraception, which puts them at higher risk for unintended pregnancy.

Contraception is a critical component of healthcare for reproductive-age women. However, nearly one in five (18%) sexually active women ages 18-44 are not using any method of contraception and are at high risk for unintended pregnancy. About half (48%) of women ages 18-44 report that they or their partners used at least one contraceptive method, one in ten (11%) are pregnant or trying to conceive, and one in five (23%) women report that they or their partner have had a sterilization procedure or cannot become pregnant. Among sexually active women who have used contraceptives in the past year, nearly six in ten (59%) report using male condoms and 40% have used oral contraceptives. Smaller shares report using other methods, such as IUDs and injectables.

Most women get their gynecologic and contraceptive care from private doctors’ offices, but a significant share of low-income and uninsured women go to clinics for this care.

Seven in ten (72%) women ages 18-44 report that their most recent gynecologic exam took place at a doctor’s office or HMO. Roughly one in ten (12%) women report that they went to a community health center or other public clinic; However, this rate is higher among some groups – 30% of Latinas, 23% of rural women, 34% of uninsured women, 23% of low-income women, and 19% of women who have Medicaid reported going to these clinics for their most recent gynecologic exam. These patterns persist in where women get their contraception care. Six in ten women obtain contraception from a private doctor or HMO, while one in five go to a clinic and another one in five go somewhere else, such as a drug store for condoms. Among low-income women, however, more than one-third (36%) report obtaining contraceptives at a clinic. One in three women ages 18-44 report that they have ever visited a Planned Parenthood clinic for health care services.

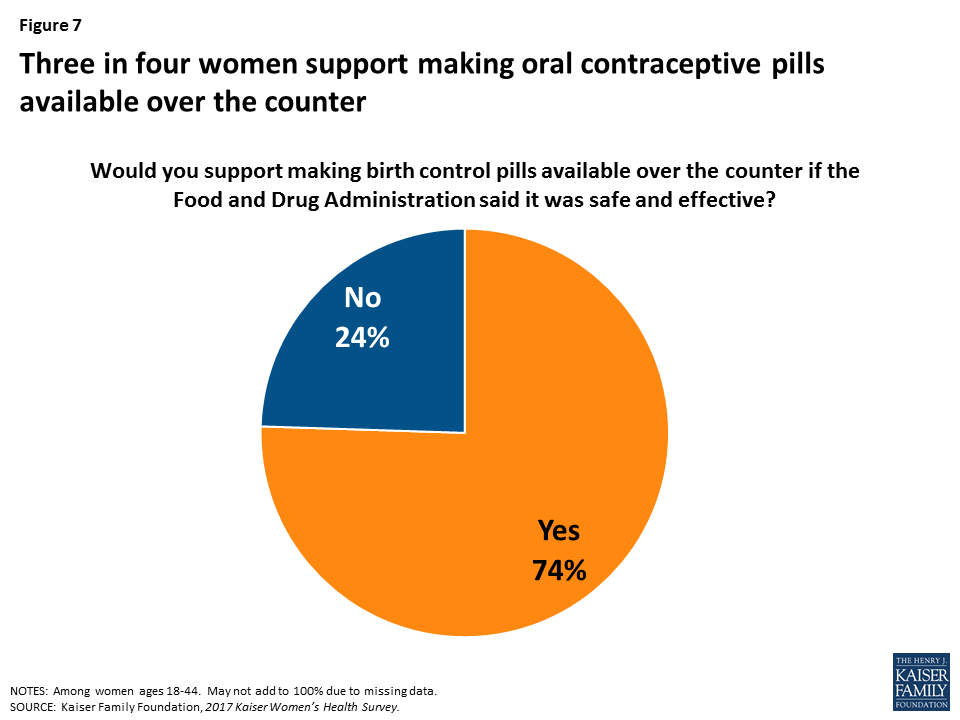

Three-fourths of women support over-the-counter access to oral contraceptive pills. Today, very few women get their contraception through direct pharmacy access or using an app.

Research suggests that over the counter access to oral contraceptives would increase the use of contraception and facilitate continuity of use; however currently, oral contraceptives are only available by prescription, usually from a doctor’s office. Among women of reproductive age, three-fourths (74%) support making oral contraceptives available over the counter if the FDA said it was safe and effective (Figure 7).

Some states have passed laws allowing women to get a contraceptive prescription directly from a pharmacist without seeing a doctor. In addition, several startups have developed online apps that allow women to get a prescription and order contraception to be delivered to their home or a nearby pharmacy. However, when asked how they obtained oral contraceptives and the patch, almost all women (95%) stated they obtained these methods from a doctor or clinic prescription rather than from a pharmacy or an online app.

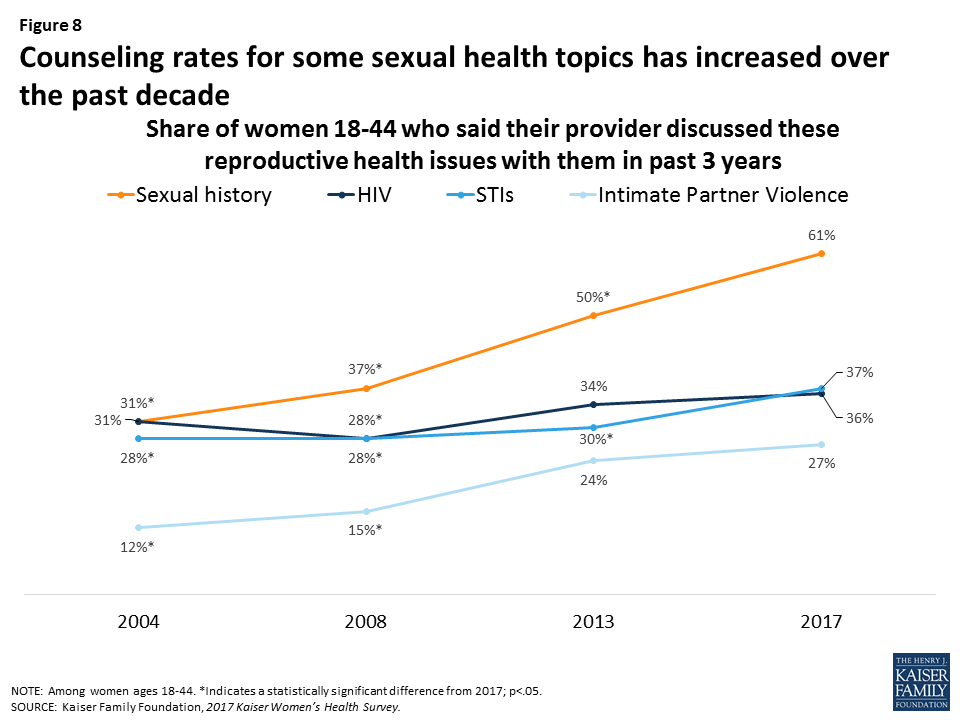

Provider counseling rates on sexual health topics have increased over time, but many women still report that their provider has not spoken with them about intimate partner violence.

In 2004, less than a third of women reported recently speaking with a provider about their sexual history, but this has risen sharply to six in ten women (61%) in 2017 (Figure 8). Despite the ACA’s no-cost coverage for intimate partner violence (IPV) screening, provider counseling on violence however remains low at 27% but this is up from 12% in 2004. Counseling rates on HIV and STIs have risen modestly.

Work and Family Health

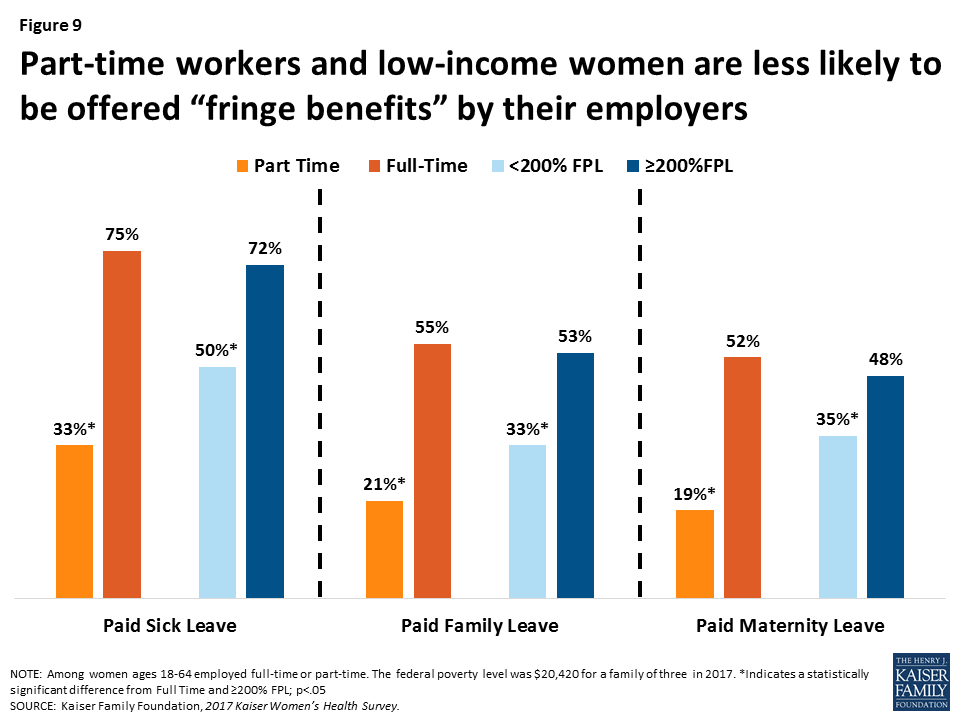

Employer benefits such as paid leave can help women meet their personal and family health care needs while also fulfilling their work responsibilities. However, benefits are not equally available to all workers.

About two-thirds of working women report that their employer offered them paid sick leave (65%), while almost half are offered paid maternity leave (44%) and paid family leave (47%). However, low-income women and part-time employees are less likely to be offered these benefits (Figure 9).

In most households, women are the managers of their families’ health care needs. Many working mothers lose pay when they take time off to care for sick children.

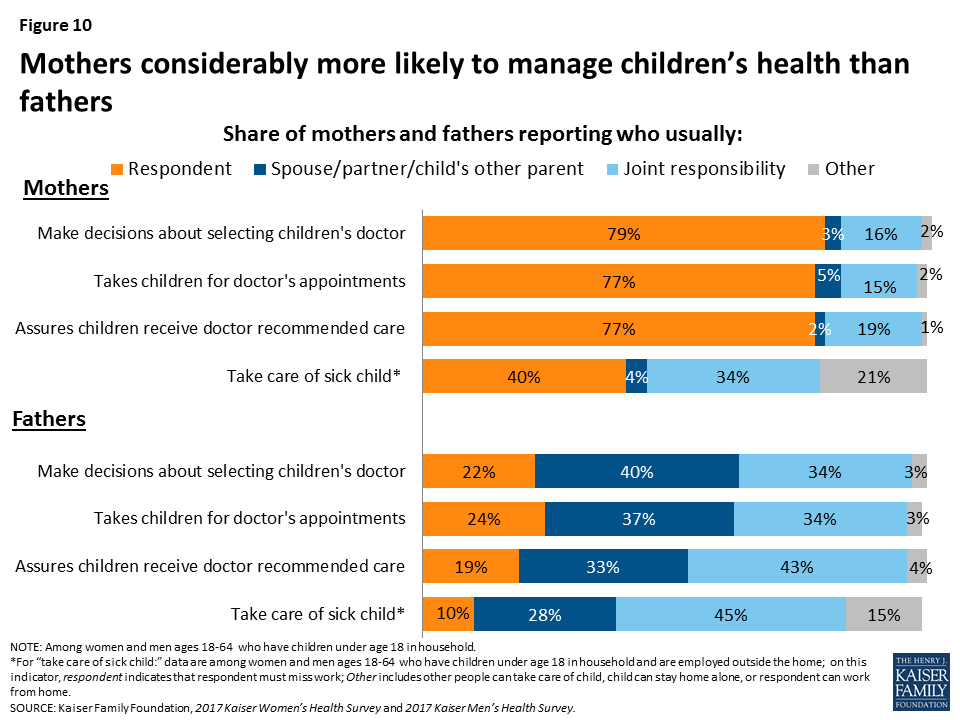

About three-quarters of mothers report that they are the ones who usually take charge of health care responsibilities such as choosing their children’s provider (79%), taking them to appointments (77%), and following through with recommended care (77%), compared to approximately a fifth of fathers who report they take care of these tasks (Figure 10). These rates have remained relatively unchanged for the past decade. Among working mothers, four in ten (40%) say they must take time off work and stay home when their children are sick. Among this group, more than half (56%) report they are not paid for that time off.

Conclusion

Women have much at stake in how the health care system operates. Seven years after the passage of the ACA in 2010, nine in ten women have health insurance coverage, more than ever before. Most women report having a regular place and clinician they go to for care, and counseling rates on a range of health issues have increased over the past decade. In addition, the majority of women who use contraception have full coverage without cost sharing under the ACA’s preventive services requirement.

However, it is important to recognize the ways in which the provision of healthcare can still improve. One in ten women remain uninsured, with higher rates among low-income women and women of color. Uninsured women have fewer connections to the health care delivery system and lower use of preventive services such as screening tests and provider counseling. A substantial share of women also continue to report that out of pocket costs limit their ability to see providers when they need to, obtain recommended tests and treatments, and adhere to medication protocols. Among reproductive-age women, one in five remain at high risk for unintended pregnancy despite increased coverage for contraception. All of this must be considered in the context of women’s lives. As mothers, most are in charge of addressing children’s health care needs. In addition, some women report they do not have time, or other supports, such as transportation and childcare, to obtain timely care. As the ACA and the Medicaid program face future challenges, some of the progress in coverage made in the past decade may be eroded, and more women could become uninsured and have difficulty accessing needed health care services.

Methodology

Summary

The 2017 Kaiser Women’s Health Survey obtained telephone interviews with a nationally representative sample of 2,751 women ages 18 to 64 living in the United States. The survey was designed and analyzed by staff at the Kaiser Family Foundation, and fieldwork was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Interviews were done in English and Spanish by Princeton Data Source LLC from July 26 to September 27, 2017. Interviews were conducted via landline (nLL=963) and cell phone (nC=1,788; including 1,255 without a landline phone). Statistical results are weighted to correct known demographic discrepancies. The margin of sampling error for the complete set of weighted data is ±2.8 percentage points.

Sample Design

A combination of landline and cellular random digit dial (RDD) samples was used to represent all women ages 18 to 64 in the United States who have access to either a landline or cellular telephone. Both samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC (SSI) according to PSRAI specifications. The samples were disproportionately-stratified to reach more low-income women and to increase the incidence of African-American and Latina respondents. To supplement the RDD samples, 188 interviews were completed using callback sample collected from recent PSRAI Omnibus surveys, national general population surveys of 1,000 interviews with adults that are usually fielded every other week.

As many as 7 attempts were made to contact every sampled telephone number. Sample was released for interviewing in replicates, which are representative subsamples of the larger sample. Using replicates to control the release of sample ensures that complete call procedures are followed for the entire sample. Calls were staggered over times of day and days of the week to maximize the chance of making contact with potential respondents. Each phone number received at least one daytime call if needed. Only female interviewers were used on this project. For the landline sample, interviewers first asked to speak with an adult female who was at home and age screening was done on that individual. Once a female was on the phone, they were asked their age and screened accordingly. Females were asked their age and screened accordingly. All eligible women reached on cell phones were offered a post-paid cash reimbursement of $5 to participate in the study.

Weighting and Analysis

Weighting is generally used in survey analysis to adjust for effects of the sample design and to compensate for patterns of nonresponse that might bias results. The weighting was accomplished in multiple stages to account for (a) the disproportionately-stratified samples, (b) the overlapping landline and cell sample frames, (c) household composition, and (d) differential non-response associated with sample demographics. The telephone usage parameter was derived from an analysis of recent national surveys conducted by PSRAI. All other weighting parameters were derived from the Census Bureau’s 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) PUMS data.

The survey’s margin of error is defined as the largest 95% confidence interval for any estimated proportion based on the total sample — the one around 50%. The margin of error for the entire sample of women ages 18-64 is ±2.8 percentage points and +3.8 percentage points for the sample of women ages 18-44. It is important to remember that sampling fluctuations are only one possible source of error in a survey estimate.