State Options for Medicaid Coverage of Inpatient Behavioral Health Services

What Behavioral Health Services Does Medicaid Cover?

Medicaid covers many behavioral health services, though there is not a specifically defined category of Medicaid benefits dedicated to behavioral health. Some behavioral health services fall under mandatory Medicaid benefit categories that all states must cover. For example, psychiatrist services are covered under the required “physician services” category. States also cover behavioral health services through optional benefit categories that states may choose to include in their Medicaid programs, such as case management or prescription drugs (which all states do). One important benefit category for behavioral health is the rehabilitative services option, through which states commonly cover non-clinical behavioral health services such as peer support and community residential services. In addition, under waiver or state plan authority, states can provide home and community-based long-term care behavioral health services that support independent community living, such as day treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation services. While all states that participate in Medicaid must cover inpatient services, federal law prohibits payment for services provided in IMDs, as further described below. Box 1 provides examples of behavioral health services that may be covered by Medicaid. A glossary defining key Medicaid behavioral terms is included in the Appendix.

Medicaid coverage of behavioral health services is sometimes more comprehensive than private insurance coverage. While many private insurance plans cover psychiatric hospital visits, in some states, Medicaid is more likely to cover additional services, such as case management, individual and group therapy, detoxification, and medication management. Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports on which many people with disabilities, including those with mental health needs, rely to live independently in the community.

Box 1: Examples of Medicaid Behavioral Health Services

- Institutional care and intensive services for some populations, such as psychiatric hospital visits, 23-hour psychiatric observation, psychiatric residential, inpatient detoxification, and SUD residential rehabilitation, except for services provided in IMDs.

- Outpatient services, such as case management, psychiatric evaluation, psychiatric testing, psychological testing, individual therapy, group therapy, family therapy, intensive outpatient, outpatient detoxification, methadone maintenance, Suboxone treatment, and medication evaluation, prescription, and management.

- Home and community-based long-term services and supports, such as adult group homes, day treatment, partial hospitalization, psychosocial rehabilitation, supported housing, and supportive employment.

What Are the Patterns of Behavioral Health Treatment Among Nonelderly Medicaid Adults?

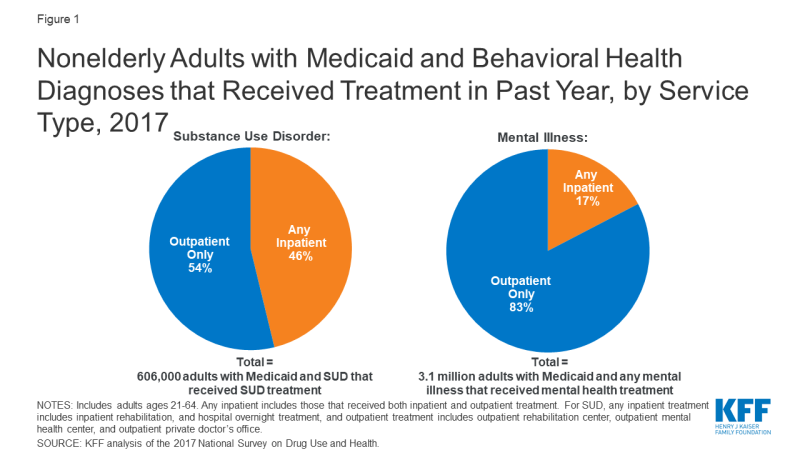

Most nonelderly Medicaid adults receiving behavioral health treatment do so in an outpatient setting, without any inpatient services. In 2017, inpatient services were used by just under half (46%) of nonelderly Medicaid adults with SUD who received drug or alcohol treatment in the past year (Figure 1). A smaller share (17%) of Medicaid enrollees with mental illness who received treatment used inpatient services. The data do not distinguish services provided in IMDs from those provided in other inpatient settings such as a general inpatient hospital.

Figure 1: Nonelderly Adults with Medicaid and Behavioral Health Diagnoses that Received Treatment in Past Year, by Service Type, 2017

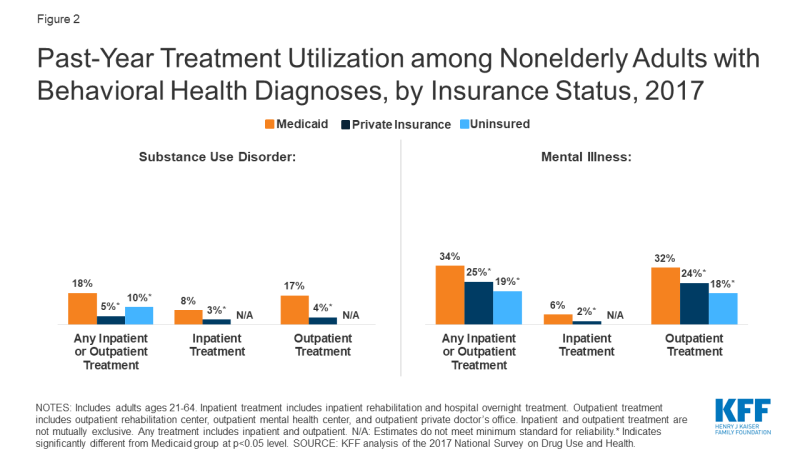

Though nonelderly Medicaid adults with behavioral health needs are significantly more likely than those who are privately insured to have used inpatient and outpatient treatment services in the past year, treatment rates are low across all payers. Among nonelderly adults with SUD, those with Medicaid are more likely have used inpatient treatment services compared to those with private insurance (8% vs. 3%, Figure 2). Similarly, among nonelderly adults with any mental illness, those with Medicaid are more likely to have used inpatient treatment, compared to those with private insurance (6% vs. 2%). Nevertheless, treatment utilization rates (use of treatment services in past year by those with a behavioral health diagnosis), particularly for inpatient treatment, remain low across payers. Inpatient treatment rates are low even for private insurers who, unlike Medicaid, are not subject to the IMD payment exclusion.

Figure 2: Past-Year Treatment Utilization among Nonelderly Adults with Behavioral Health Diagnoses, by Insurance Status, 2017

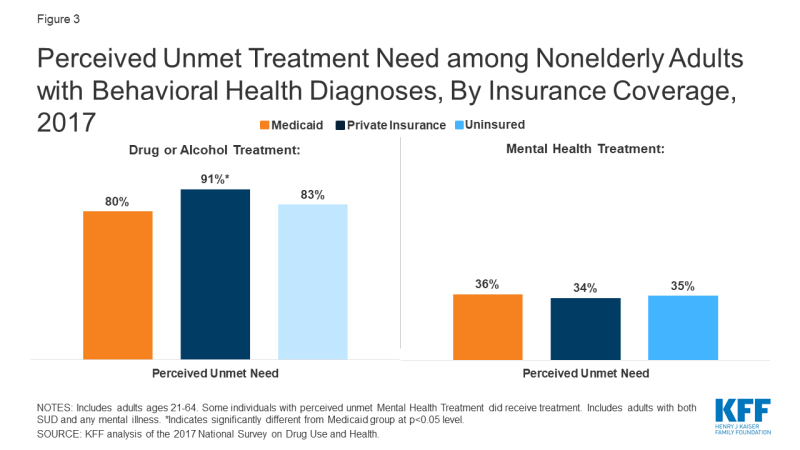

Many people with behavioral health diagnoses report unmet treatment needs. Substantial shares of nonelderly adults with SUD and any mental illness report an unmet need for drug or alcohol treatment, with those with private insurance significantly more likely to have an unmet SUD treatment need compared to those with Medicaid (91% vs. 80%, Figure 3). The share of nonelderly Medicaid adults with SUD and any mental illness reporting an unmet need for mental health treatment is similar to those with private insurance (36% vs. 34%).

Figure 3: Perceived Unmet Treatment Need among Nonelderly Adults with Behavioral Health Diagnoses, By Insurance Coverage, 2017

Administrative data shows wide state variation in use of inpatient services among nonelderly Medicaid adults who receive mental health or substance use disorder services. In FY 2013, the share of nonelderly Medicaid adults receiving any behavioral health treatment who received any inpatient SUD services ranged from 10% in Alaska to 57% in West Virginia. The share of those receiving any inpatient mental health services ranged from 9% in Alaska to 31% in Alabama and New York (Appendix Table 1). Like the national data discussed above, the state-level data do not separately identify IMD services from other inpatient services. In addition, this data – which is the most recently publicly available – predates the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and the opioid epidemic’s impact over the last six years, and consequently may understate the number of enrollees now utilizing these services in states that have implemented the expansion since 2014.1

What is the IMD Payment Exclusion and Its Exceptions?

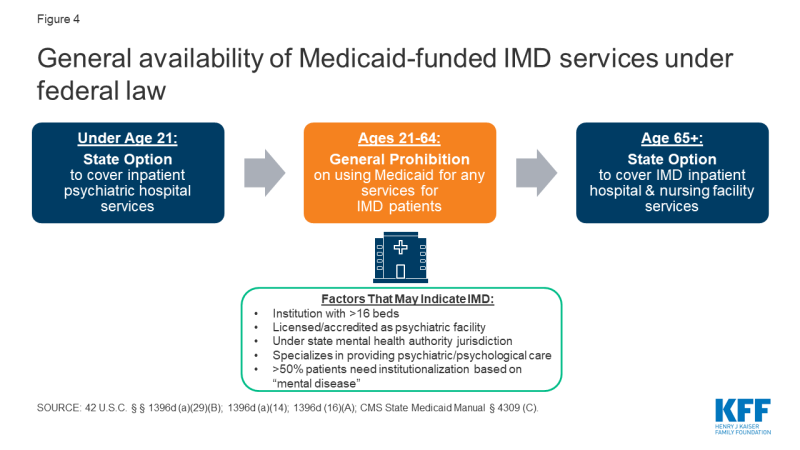

Federal law generally bars states from receiving “any [Medicaid] payments with respect to care or services for any individual who has not attained 65 years of age and who is a patient in an [IMD].”2 The payment exclusion applies to services provided within an IMD as well as to services provided outside an IMD to nonelderly adult IMD patients. An IMD is a “hospital, nursing facility, or other institution of more than 16 beds, that is primarily engaged in providing diagnosis, treatment, or care of persons with mental diseases [sic], including medical attention, nursing care, and related services” (Figure 4).3 Whether a particular facility is an IMD is determined by the state. Figure 4 lists factors considered in this determination. While all states that choose to participate in the Medicaid program must cover inpatient hospital services, those services specifically exclude care provided in IMDs.4 The IMD payment exclusion applies to Medicaid enrollees ages 21 through 64. States have the option to cover inpatient psychiatric hospital services for those under age 215 and IMD inpatient hospital and nursing facility services for those age 65 and older.6

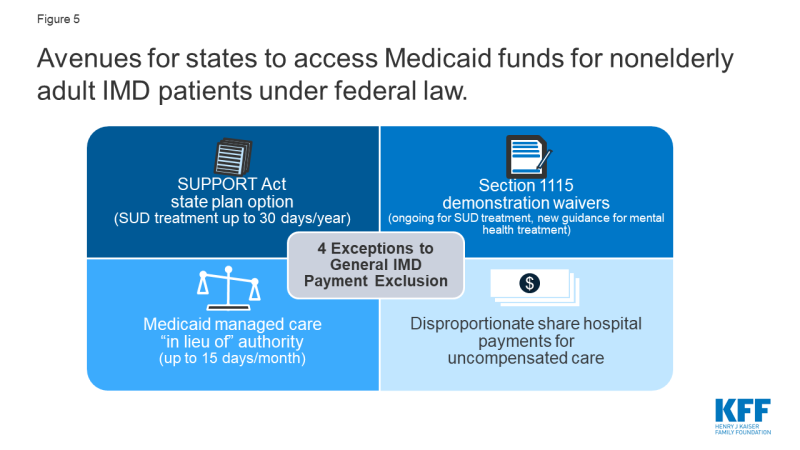

There are four ways that states can receive federal Medicaid funds for IMD services for nonelderly adults. These include Section 1115 demonstration waivers, Medicaid managed care “in lieu of” authority, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and the SUPPORT Act7 state plan option (beginning in October 2019) (Figure 5). Box 2 discusses considerations for providing institutional services under the Americans with Disabilities Act, separate from Medicaid.

Figure 5: Avenues for states to access Medicaid funds for nonelderly adult IMD patients under federal law.

Box 2: Institutional Services and Community Integration

Waiving the IMD payment exclusion and expanding institutional services without also ensuring adequate access to community-based services could have implications for states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) if people with disabilities are inappropriately institutionalized.8 The Supreme Court’s Olmstead decision found that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities violates the ADA. The ADA’s community integration mandate is separate from federal Medicaid law. However, states rely on Medicaid funding to help meet their ADA obligations, because Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports, including home and community-based services.9 Medicaid also is an important source of financing for behavioral health services, paying for 21% of SUD services and 25% of mental health services as of 2014.10 Consequently, even when providing IMD services to the extent permitted under federal Medicaid law or a waiver, states still separately must meet their independent community integration obligations under the ADA.

Section 1115 waivers

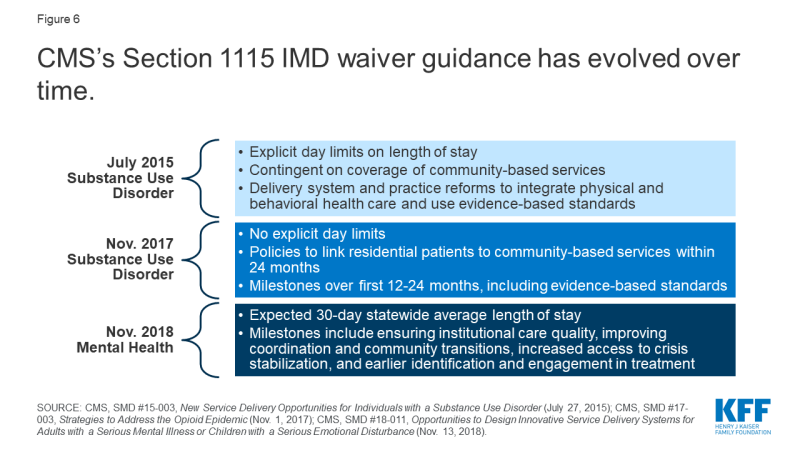

With the opioid epidemic increasing, CMS has been inviting states to apply for Section 1115 IMD SUD waivers,11 with guidance released in 2015,12 and revised in 2017.13 These waivers allow states to test using federal Medicaid funds to provide short-term inpatient and residential SUD treatment services in IMDs. Some of the requirements for these waivers have evolved over time (Figure 6). For example, unlike waivers approved under the 2015 guidance,14 waivers approved under the 2017 guidance do not explicitly limit the length of individual IMD stay.15 In addition, waivers under the 2015 guidance were contingent on states covering community-based SUD treatment services at the time of approval,16 while the 2017 guidance allows states up to two years after waiver approval to cover “critical levels of care.”17 As discussed in more detail below, more than half of states have an approved or pending IMD SUD payment waiver as of November 2019.

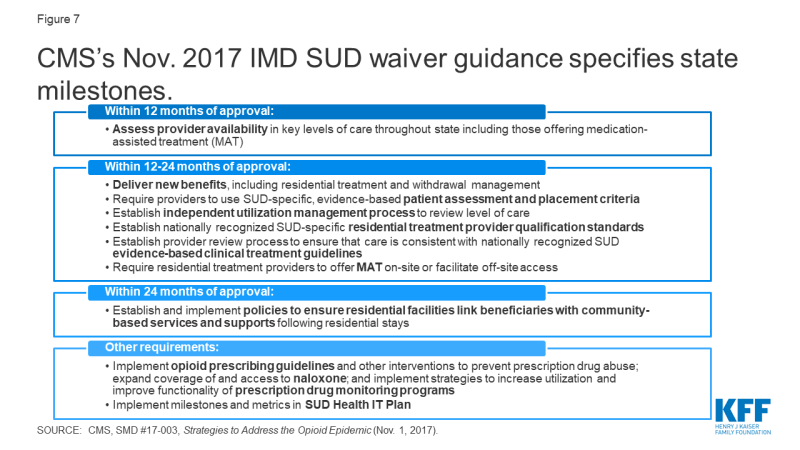

In addition to covering certain levels of care, the 2017 guidance incorporates other milestones that states must achieve during the term of an IMD SUD waiver (Figure 7).18 These include using evidence-based patient placement criteria; applying nationally recognized provider qualification standards; implementing prescribing guidelines and other strategies to address opioid abuse; and improving care coordination and transitions between levels of care.19 CMS’s 2019 IMD SUD waiver evaluation design guidance identifies SUD treatment access and utilization,20 health outcomes,21 and opioid-related overdose deaths as three key areas to assess.22

CMS also reversed long-standing policy and issued new guidance inviting states to apply for Section 1115 IMD payment waivers for mental health services in November 2018 (Figure 6).23 Until this point, CMS had not approved IMD mental health waiver requests in Illinois,24 Massachusetts,25 or North Carolina,26 citing its former policy not to allow Medicaid payments for individuals who receive only mental health treatment in IMDs.27 Under the new guidance, states will have to achieve a set of milestones over the term of these waivers, including ensuring institutional care quality, improving coordination and community transitions, increasing access to crisis stabilization, and earlier identification and engagement in treatment. States that previously had IMD mental health waiver requests that were not approved, as well as states with new requests, can apply for waivers under the 2018 guidance. As of November 2019, only one state (Vermont) has an approved Section 1115 IMD mental health waiver.

Managed care “in lieu of” authority

States with capitated managed care delivery systems can use “in lieu of” authority to cover IMD SUD and mental health services for up to 15 days per month.28 Specifically, states can use federal Medicaid funds for capitation payments to managed care plans that cover IMD inpatient or crisis residential services for nonelderly adults instead of providing other services, such as non-IMD inpatient or outpatient services, that are covered in the state plan benefit package.29 The IMD services must be medically appropriate and cost-effective, and enrollees cannot be required to accept IMD services instead of state plan services. This regulation took effect in July 2016,30 although it codified pre-existing long-standing federal sub-regulatory guidance that allowed federal Medicaid payments for IMD services. However, unlike the regulation, the former guidance did not subject IMD services covered under “in lieu of” authority to a day limit. Of the 41 states using comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations, 31 use Medicaid managed care “in lieu of” authority to cover IMD SUD and/or mental health services in both FY 2019 and FY 2020, and two (MS and NC) report plans to begin doing so in FY 2020.31 Two states reported using the authority in FY 2019 only (Appendix Table 3).32

Disproportionate Share Hospital payments

States can spend a portion of their Medicaid DSH funds on IMD services.33 States must make these payments to offset uncompensated care costs incurred by hospitals that serve a disproportionate number of low-income patients. In FY 2018, 33 states made DSH payments totaling $2.9 billion to mental health treatment facilities including IMDs. These payments ranged from 0.0003% of total DSH payments to mental health facilities in Minnesota to 18% in New York (Appendix Table 4).

Support Act state plan option

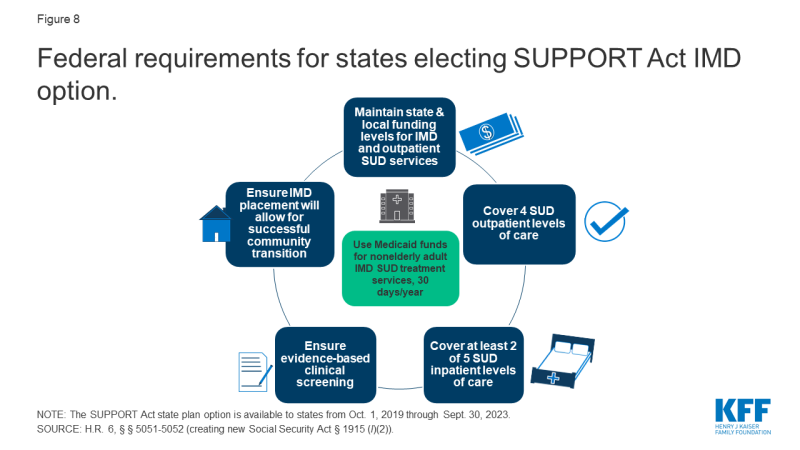

The SUPPORT Act partially lifts the IMD payment exclusion by allowing states to use federal Medicaid funds for nonelderly adults receiving IMD SUD services up to 30 days a year,34 from October 2019 through September 2023.35 IMD coverage under the SUPPORT Act option is in addition to IMD services covered under managed care in lieu of authority36 and Section 1115 waivers.37 To receive Medicaid payments under the SUPPORT Act option, IMDs must follow “reliable, evidence-based practices” and offer at least two forms of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) on-site38 for opioid use disorder. Separately, the SUPPORT Act also authorizes Medicaid payments for services provided outside IMDs for pregnant and post-partum women receiving IMD SUD services, as of October 2018.39

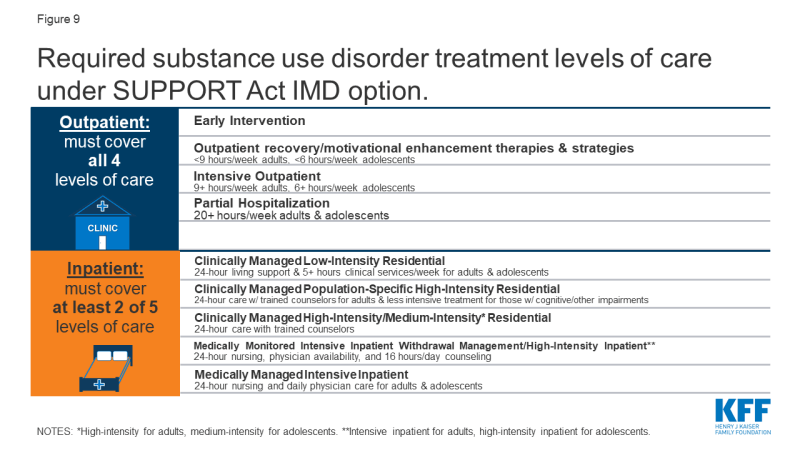

States must satisfy five criteria to qualify for Medicaid funds under the SUPPORT Act option (Figure 8). First, states have to maintain annual state and local funding levels40 for both IMD services and a specific list of community-based outpatient services41 provided to nonelderly adults who become eligible for Medicaid-funded IMD services under the new option. Additionally, states must ensure that nonelderly adults receive “appropriate evidence-based clinical screening” prior to receiving IMD SUD services.42 States also must confirm that IMDs receiving Medicaid payments can provide outpatient services, either themselves or through an established relationship with another facility or provider accepting Medicaid patients, to allow for successful community transitions.43 Finally, states electing the SUPPORT Act option must cover Medicaid SUD treatment services at four outpatient levels of care44 and at least two of five inpatient levels of care45 (Figure 9).

According to a KFF survey, five states report plans to pursue the SUPPORT Act option in FY 2020.46 These states include Idaho, Indiana, New Hampshire, South Dakota, and Tennessee.47 Twenty-one states report that they have not yet determined if they will pursue the SUPPORT Act option,48 and 24 states indicate that they do not plan to pursue this option.49 In explaining the rationale for not pursuing this option, many states noted that they already had a Section 1115 waiver in place or were pursuing such a waiver to allow IMD funding.50 Several states also felt that their Section 1115 waiver would provide more flexible limits on length of IMD stays compared to the 30-day cap on IMD services under the SUPPORT Act option.51 Table 1 compares key elements of Section 1115 IMD waivers with the SUPPORT Act.

| Table 1: Key Elements of Section 1115 Waivers vs. SUPPORT Act Option for IMD Payment | ||

| Program Element | Section 1115 Waiver | SUPPORT Act |

| Type of authority | Waiver | State plan option |

| Length of authority | Initial waivers usually granted for 5 years. States can apply for renewals, usually for 3 years. | Available from October 2019 through September 2023. |

| Type of IMD services allowed | SUD and/or mental health | SUD only |

| Length of stay | Varies by waiver: some numeric day limits, some unspecified, some require 30-day statewide average. | 30 days per year |

| Covered inpatient levels of care | Must cover intensive residential/inpatient and medically supervised withdrawal management within 24 months of waiver approval. | Must cover at least 2 of 5 inpatient levels of care. |

| Covered outpatient levels of care | Must cover outpatient and intensive outpatient services within 24 months of waiver approval. | Must cover all 4 outpatient levels of care. |

| Institutional to community transitions | Must develop policies to link residential patients to community-based services. | Must ensure that IMD placement will allow for successful community transition. |

| Evidence-based practices | Must use evidence-based patient assessment and placement criteria and provide access to MAT. | Must follow evidence-based practices, including clinical screening and MAT. |

| Maintenance of effort | For SUD waivers, CMS encourages states to maintain current funding levels for a continuum of services; waivers should not reduce or divert state spending on behavioral health services. For mental health waivers, CMS will consider a state’s commitment to on-going maintenance of effort on funding outpatient community-based services when approving waivers. | Must maintain state and local funding levels for IMD and outpatient services. |

How Are States Using Medicaid IMD Waivers?

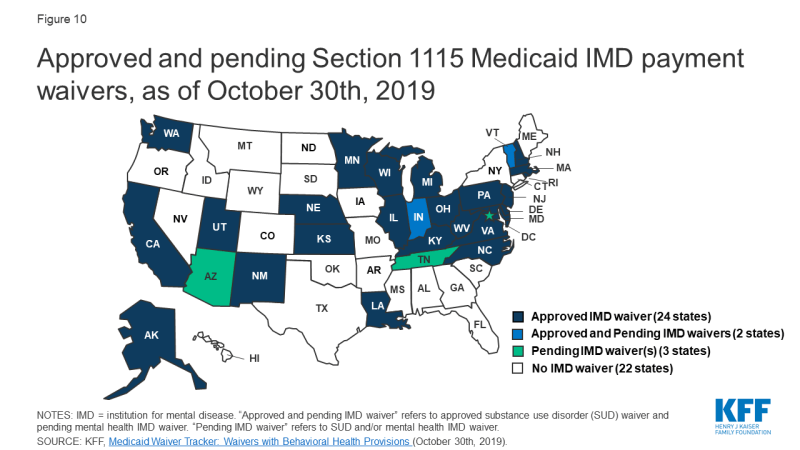

The number of Section 1115 IMD SUD waiver approvals has markedly increased since January 2017. Four states had IMD SUD waivers approved by CMS as of December 31, 2016, and another 22 states have had IMD SUD payment waivers approved since then. Three more states have these waiver requests pending with CMS as of November 2019 (Figure 10 and Appendix Table 2).52 To date, Vermont remains the only state with an existing IMD mental health waiver, the current terms of which require those payments to phase out between 2021 and 2025.53 Vermont recently submitted a request to transition its existing mental health authority to the terms of the new guidance. Additionally, DC and Indiana have submitted pending waiver requests for IMD mental health services under the new guidance, with more states expected to follow. Idaho, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island report plans to pursue an IMD mental health waiver in FY 2020, while Alaska, Connecticut, Virginia, and Washington report plans to do so after FY 2020.54

While waiver evaluations are still underway, news reports, interim evaluations, and feedback directly from states can inform the ongoing implementation of IMD waivers. While some waiver evaluation results are emerging, most are not expected until 2024 or 2025 (Appendix Table 2).55 Given the attention to state efforts to combat the opioid epidemic and emerging focus on mental health, states are moving forward with waiver implementation. State experience with these initiatives can help inform policy choices and design as other states consider similar waivers. To make some of this information available in advance of formal waiver evaluations, we conducted case studies in two states and one county. Table 2 summarizes the waivers in the three case study areas, and Box 3 describes the case study methodology.

| Table 2: Key Components of Approved 1115 Waivers for California, Virginia, and Vermont | |||

| State | California | Virginia | Vermont |

| Waiver/Program Name | Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System (DMC-ODS) | The Virginia GAP and ARTS Delivery System Transformation | Vermont Global Commitment to Health |

| Approval Date | 8/13/2015 | 12/15/2016 | 1/1/199656 |

| IMD Authority Begins | 1/1/2016 (San Diego County implanted 7/2018) | 4/01/2017 | 1/1/199657 |

| IMD Authority Expires | 12/31/2020 | 12/31/2019 (Submitted amendment to extend) | 12/31/2021 for SUD; mental health to phase-out by 2025 (pending mental health waiver submitted to CMS) |

| SUD Authority | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mental Health Authority | ✓ | ||

| Day Limit | 30-day statewide average; 90 day max. | 30-day statewide average | 30-day statewide average |

| SOURCE: KFF analysis of Section 1115 waivers for the IMD Payment Exclusion | |||

Box 3: Overview of Case Study Areas

Because waiver evaluations are ongoing and there is limited information about states’ experiences and outcomes with IMD waivers to date, we conducted case studies in Vermont; San Diego County, California; and Virginia, to provide a snapshot of how these three areas are using IMD waivers and identify common themes and lessons learned. In July 2019, we interviewed state and county officials by phone. We also reviewed publicly available waiver approval, reporting, and evaluation documents. Because San Diego County’s program is part of the California waiver, we also include relevant findings from the overall California waiver evaluation and other California waiver documents as relevant. In addition to considering geographic and political diversity, we chose case study regions to enable us to examine state experiences based on the type of IMD waiver authority (SUD and/or mental health), whether the waiver was approved under the 2015 or 2017 CMS guidance, and duration of implementation (Table 2).

Vermont has long-standing experience with using federal Medicaid funds for both IMD SUD and mental health services, through a Section 1115 waiver dating back to 1996. Vermont’s SUD authority is currently authorized under CMS’s 2017 guidance. Although the current waiver requires Vermont to phase-out IMD mental health funding between 2021 and 2025,58 the state has applied for IMD mental health waiver authority under the 2018 guidance. San Diego County began offering IMD SUD services in July 2018, and is one of the 40 counties participating in California’s Section 1115 waiver Drug Medi-Cal Organized Delivery System pilot program, which was approved under the 2015 guidance.59 Virginia added the Addiction and Recovery Treatment Services (ARTS) Delivery System Transformation Demonstration program, which includes IMD SUD services, to its Section 1115 waiver effective April 2017. Virginia’s waiver initially was approved under the 2015 CMS guidance, although the state subsequently came into compliance with the 2017 guidance.60

Role of Community-Based Services

Interviews with case study areas implementing IMD waivers reveal that some expanded community-based treatment services in addition to IMD services. Notably, Virginia used state funds that previously went to IMD services to finance additional community-based SUD services to complement the IMD SUD services authorized by its waiver. Specifically, Virginia used state plan authority to add recovery supports and expanded medication-assisted treatment to the intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential levels of care. In addition to IMD residential services, California’s waiver adds enhanced SUD community-based services in the participating counties, including case management, withdrawal management, recovery services, physician consultation, and at county option, additional MAT drugs and partial hospitalization. Without the waiver, the California Medicaid state plan benefit package is limited to outpatient, intensive outpatient, perinatal residential (non-IMD), and opioid treatment program services. Other states not included as case studies for this report similarly expanded community-based services either under or in conjunction with their waivers authorizing payment for IMD services, such as West Virginia,61 Kansas,62 Illinois,63 Alaska,64 Indiana,65 and Wisconsin.66 However, at least one state (Kentucky) has restricted access to some community-based services (methadone) while funding IMD services under its waiver.67

While states believe that newly added community-based services are essential to achieving their waiver goals, utilization of some of the new services during initial implementation has not been as high as expected. Respondents noted that use of recovery supports (Virginia and California)68 and case management (California)69 has been low. As waiver implementation continues, these states are focused on additional provider training to increase new service utilization and improve treatment continuity as enrollees transition among care settings.

States are making efforts to address transitions between inpatient and outpatient care settings. California’s managed care external quality review report recommends that SUD providers at both residential and outpatient levels of care be allowed to bill for services provided to an individual on the same day to align with evidence-based best practices that call for introducing a patient to new treatment staff at least twice before residential discharge.70 This practice is intended to smooth care transitions and increase the rate of community-based treatment engagement after residential discharge. Having implemented bundled payments for episodes of care in 2019, Vermont is transitioning to value-based payments for IMD SUD services by January 2021, seeking to eliminate incentives for longer residential stays resulting in higher provider payments. The model is designed to encourage providers to engage in effective discharge planning, with payment disincentives for rapid readmissions. Virginia requires providers to include comprehensive transition plans and coordination of current care and post-discharge plans related to community services in their treatment plan to ensure continuity of care upon discharge with the individual’s family, school and community.

Provider Networks and Service Delivery Changes

In addition to covering new services, states took steps to expand or maintain IMD residential provider networks for SUD services. San Diego County has worked to develop its residential provider network, while Vermont is focused on maintaining its long-standing network. One challenge in San Diego and other California counties has been helping residential providers establish the record keeping and quality improvement initiatives needed to successfully bill for Medicaid services.71 San Diego’s initiatives in this area include “gentle” reimbursement withholding incentives, in which a portion of provider payment is delayed until certain performance standards are met. San Diego also has spent substantial county staff time offering technical assistance to providers and introduced advance payments so that providers had funding available upfront to establish the needed administrative infrastructure.

States also worked to expand their community-based provider networks and increase payment rates. Virginia has been able to use state funds to fund “significant” provider rate increases for intensive outpatient and partial hospitalization services intended to build the Medicaid provider network. California’s waiver broadens the range of approved SUD treatment providers and allows counties to pay providers at higher than state plan rates to account for geographic differences and encourage providers to add capacity.72

All three areas also have initiatives to improve care coordination across providers to help ensure that enrollees remain connected to care as required under waiver guidance and milestones. For example, Virginia added a new office-based treatment program benefit, which co-locates a buprenorphine waivered provider and a licensed mental health provider, and includes reimbursement for care coordination. Virginia also changed its policy to allow both medical and SUD providers to bill for services for the same patient on the same day. This change was identified as a lesson learned to incentivize engaging patients in SUD treatment when they come in for other needed care. For example, a pregnant woman may see both an obstetrician and an MAT provider on the same day. San Diego County is including peer advocates and social work staff alongside doctors in emergency departments to help connect patients to community-based treatment after discharge.

Utilization and Participation

Evaluation results in all three areas show increased treatment service utilization and provider participation. Results from the first year (April 2017 to March 2018) of waiver implementation in Virginia found that the number of outpatient providers billing for ARTS services increased by 173%;73 the number of Medicaid enrollees who used SUD treatment services increased by 57%;74 and more than 40% of enrollees with SUD received treatment, up from 24% in the prior year.75 In the seven counties that began service delivery in 2017, California’s waiver evaluation found that the number of people accessing treatment increased by about 7%.76 In the three counties included in the California waiver’s managed care external quality review report, the number of enrollees receiving SUD services nearly tripled in the first year of waiver implementation, compared to pre-waiver baseline claims data.77 While not yet included in California’s waiver evaluation findings, San Diego County anecdotally reports a 40 to 50% increase in the number of patients receiving SUD treatment services on both an inpatient and outpatient basis since waiver implementation in July 2018, compared to the corresponding month in the prior year. Vermont’s evaluation for 2013 to 2016 found that rates of initiation and engagement in community-based treatment post inpatient discharge for enrollees who had received IMD services exceeded both the general Vermont Medicaid rate and the national rate for both SUD and psychiatric services.78

California’s waiver evaluation found notable gains in access to residential treatment that could not have been financed by Medicaid without the waiver.79 Additionally, the California waiver’s managed care external quality review report notes that without the IMD payment authority, “[a]pproximately 80 percent of the residential facilities in California would not have qualified for [Medicaid] reimbursement, thus severely limiting treatment options.”80 As of March 2019, San Diego County reported adding 67 IMD beds, which has reduced the number of patients waiting for services.81

Evaluation results also have found decreases in emergency room visits and inpatient hospitalizations. From 2013 through 2016, Vermont’s interim waiver evaluation found that emergency room use within 30-days post-IMD discharge declined compared to emergency room use prior to the IMD admission for both mental health services (with declines ranging from 23 to 44%)82 and SUD services (with declines ranging from 39 to 56%).83 Psychiatric IMD readmission rates averaged 8% after 30 days over the four years, while SUD readmission rates were under 15% across settings (general hospital detox, IMD detox, and IMD residential) during this period.84 During the first 10 months of waiver implementation in Virginia, the number of emergency department visits related to SUD decreased by 14%, and the number of Medicaid enrollees with an acute inpatient admission related to SUD decreased by 4%.85

Implementation Limitations and Challenges

States report that existing IMD authority and policy may limit their efforts to address unique needs of special populations, such as pregnant women and individuals in the criminal justice system. With Vermont’s transition from its older waiver authority to waivers under the more recent CMS guidance, the state will no longer be able to use federal Medicaid funds for a specialized residential treatment facility that serves pregnant women and new mothers and infants. That care delivery model is based on a length of stay of 12 to 18 months, with an average length of stay of six months from 2013 through 2016.86 As a result, including this one program would cause the statewide average length of stay to exceed the 30 days approved in Vermont’s waiver. San Diego County and Virginia both reported unexpected challenges where the courts were ordering defendants to residential SUD treatment instead of incarceration, without regard to the evidence-based placement criteria adopted under the waiver that instead called for outpatient treatment.87 In both cases, Medicaid staff had to educate the courts about the need to order a medical evaluation to determine the appropriate level of care instead mandating residential care in all circumstances.

States report that waiver terms about IMD lengths of stay may not align with current evidence-based or state practices. California’s external quality review report found that the waiver’s limit of two IMD stays per year may be too restrictive because patients often do not complete their initial residential treatment visits, instead leaving in the first week to 10 days, but then later return when they are ready to commit to treatment.88 The report notes that current clinical criteria call for residential treatment to stabilize SUD issues, followed by partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient services, but do not limit residential treatment to two stays per year. In contrast, Virginia’s waiver initially included a 90-day maximum IMD stay, but CMS subsequently removed that provision, recognizing that stays tend to be longer at the lower levels of residential care where the focus is more on supportive services and less on clinical care. While Vermont finds that a 30-day average statewide length of stay is appropriate for SUD treatment, it believes that this limit will be too limiting for mental health treatment, especially with CMS’s newly cited position that federal Medicaid funds will be limited to individual IMD stays that do not exceed 60 days. Vermont’s state hospital serves patients with the most severe needs that can take “substantially longer to stabilize;” the average length of stay there is 120 days. Vermont will be able to meet CMS’s 30-day statewide average requirement by averaging that facility’s stays with another IMD that has more beds and serves patients with less acute needs. However, Vermont is concerned that its ability to use federal Medicaid funds for most of its state hospital patients will be limited because CMS has newly proposed that Medicaid cannot fund individual IMD stays that exceed than 60 days.

States are considering non-waiver exemptions to the IMD waivers, in part due to the time limited nature of waivers. For example, while Vermont reports that its IMD SUD waiver is working well, it also is considering pursuing the SUPPORT Act state plan option. While “largely redundant” of its existing waiver, the state sees the state plan option as more of a “long-term assurance” to have IMD payment authority in place. Virginia noted that it decided to add SUD community-based services using state plan rather than waiver authority as a way of “securing” those services as waivers are not permanent.

States are drawing on their experience with IMD SUD waivers to inform their consideration of whether to pursue and how to design an IMD mental health waiver. Before applying for an IMD SUD waiver, Virginia reviewed its existing Medicaid SUD benefits to determine what was working well and whether there were other evidence-based services that could be added to the benefit package to establish a robust community-based continuum of care. Now, Virginia is similarly assessing its Medicaid-covered mental health services. The state plans to establish a solid community-based services foundation first and then pursue a future IMD mental health waiver. After largely deinstitutionalizing its mental health services over the past 30 years,89 Vermont is working to retain a minimum capacity for patients with the most acute needs.90 The state is concerned that losing its current IMD mental health capacity under the existing federal funding phase-out plan will strain its community-based providers, who would be challenged by having to serve patients with more severe needs and as a result have less capacity to serve those with less severe needs. In Vermont’s experience, providing institutional care for the most acute patients reserves community-based services for those who do not need institutional care.

Looking Ahead

Many people with behavioral health diagnoses report unmet treatment needs, with substantial shares of nonelderly adults with SUD and any mental illness reporting an unmet need for drug or alcohol treatment. Though treatment utilization among nonelderly Medicaid adults with behavioral health needs is greater than the privately insured, treatment rates are low across all payers. Enabling states to access federal Medicaid funds for inpatient SUD and mental health treatment could help to address some of this unmet need and help states to cover services that reflect current evidence-based treatment standards. Additionally, providing federal matching funds for IMD services can free up state dollars previously spent on inpatient treatment to instead fund corresponding expansions in community-based services across the behavioral health care continuum. By law, state initiatives to expand behavioral health services cannot solely focus on inpatient services and instead also must consider community-based services, given states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Thus, state expansion of behavioral health services under efforts to fund IMDs may also address demonstrated unmet treatment needs for outpatient behavioral health services.

The number of states with Section 1115 IMD SUD payment waivers has increased dramatically since 2017, now comprising over half the states. DC, Indiana, and Vermont have submitted applications seeking an IMD mental health payment waiver under the new guidance to date, other states have expressed interest, and more applications are likely to follow. In addition, the SUPPORT Act option for IMD SUD services is newly available to states in October 2019, with a few states expressing interest to date. All three case study areas in this report reported overall positive experiences with their waivers, supported by early evaluation findings, along with some implementation challenges that had to be resolved. Notably, all three areas had devoted substantial time and resources to expanding and strengthening a robust network of community-based SUD treatment services in addition to IMD services. Policymakers reported that receiving federal Medicaid funds for IMD services under the waivers can allow state and local funds to be used to expand community-based service options, increase provider payment rates, and develop other necessary program features that Medicaid does not fund, such as housing.

Given the widespread use of SUD waivers, and the notable policy change now allowing mental health waivers, states, health plans, providers, and enrollees will be interested in evaluation results assessing the waivers’ impact. Key questions include how allowing states to use federal Medicaid funds for IMD services affects access to and utilization of inpatient and outpatient care, health outcomes, care quality, costs, IMD day limits, discharge planning and care transitions, and the continued evolution of evidence-based best practices for SUD and mental health treatment. States may draw on their IMD SUD waiver experience to inform their design and implementation of IMD mental health waivers, and many enrollees have co-occurring SUD and mental health conditions. Still, it is not entirely clear how states’ IMD SUD experience will translate to IMD mental health waivers, given differences in providers and different requirements in CMS guidance. CMS and states may implement policy changes that represent lessons learned based on states’ mid-point assessments toward their waiver milestones. While some waiver evaluation results are emerging, most are not expected until 2024 or 2025. In the meantime, states’ quarterly and annual waiver reports to CMS and interim evaluation findings can provide important information about the waivers’ impact to inform whether CMS makes further Medicaid IMD policy changes and/or whether Congress acts to amend the statute.

This work was supported in part by the Milbank Memorial Fund. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities. The authors appreciate the time that public officials in Vermont; San Diego County, California; and Virginia, as well as members of the Fund’s Reforming States Group Inpatient Mental Health Financing Workgroup (Nick Macchione, San Diego County; Becky Pasternik-Ikard, Oklahoma; Sue Birch, Washington; Duane Mayes, Alaska; Judy Lee, North Dakota; Kate McEvoy, Connecticut; and Tom Alexander, South Carolina), spent sharing their experience and expertise.