Pharmacies as an Access Point for Expanding Contraceptive Care: A Geographic Analysis

Issue Brief

Key Takeaways

- There are 3.8 million women of reproductive age living under the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) residing in counties with no or low access to publicly funded clinics offering contraceptive care.

- Policy changes, such as state policies and laws allowing pharmacists to prescribe contraceptive methods and the Food and Drug Administration approval of an over-the-counter daily oral contraceptive, have positioned pharmacies to play a bigger role in the provision of contraceptive methods.

- If all states had pharmacist prescribing laws and if all pharmacies offered this care, the share of reproductive age women under the FPL living in counties with little to no access to hormonal contraceptives could decrease, while the share in counties with broadened access to contraceptive options like the pill, ring, patch, or shot could grow considerably as a result of better contraceptive access through pharmacies.

- 35 states and DC have passed laws allowing pharmacists to prescribe, however, these policies have not been adopted by the majority of pharmacists in those states. Fifteen states do not have laws permitting pharmacists to prescribe contraception.

- Beyond enacting state policy, there are many challenges in broadening the role of pharmacists and pharmacies as access points for hormonal contraceptive methods. These include insurance and Medicaid reimbursement to pharmacists for contraceptive counseling and consultation services, pharmacist willingness, availability, and capacity to provide services, and patient awareness of the option and interest in getting contraceptive services in a pharmacy setting.

Introduction

Pharmacies are increasingly positioned to play a bigger role in the provision of certain health care services, including access to hormonal contraceptive methods. Currently, over half of states allow pharmacists to prescribe hormonal contraception. Additionally, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved an over-the-counter (OTC) daily oral contraceptive pill, and another formulation is currently under FDA review. In this brief, we explore avenues for expanding hormonal contraceptive care and supplies through pharmacies, as well as how and where pharmacies and pharmacists may be positioned to fill gaps in contraceptive care where there are few brick-and-mortar family planning providers, as well as the challenges in expanding these pathways.

Pathways to Contraceptive Care

Today, there are several paths to obtaining many hormonal contraceptives such as the pill, patch, shot, or ring. Those seeking contraceptive methods can 1) visit a clinician (e.g., doctor, nurse practitioner, or nurse midwife) to get a prescription either in-person or via telehealth, 2) order through a telecontraception service, using an online questionnaire to be completed asynchronously or a live video, phone, or text consultation, 3) obtain through a pharmacist in the 34 states that have implemented policies which allow pharmacists to prescribe hormonal contraceptives. In addition, Opill or levonorgestrel (Plan B, Next Choice) emergency contraceptive pills can be obtained at a pharmacy in person or ordered online without needing a prescription. Those who seek an IUD or an implant must go in person to a provider to get the methods inserted.

Although the majority of reproductive-aged women get their contraceptive care at a doctor’s office, larger shares of women with incomes under 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) or who are uninsured access contraceptive care at a clinic or pharmacy (Figure 1).

Publicly-Funded Contraceptive Clinics

Clinics play an important role in ensuring contraceptive access, particularly for uninsured individuals and those with low incomes. There are over 17,000 clinics nationwide that receive funds from either the Federal Title X family planning program, the Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) program, Medicaid, or the Indian Health Service (IHS) to provide family planning and contraceptive care. Despite this large network of clinics, many live in communities where access to in-person family planning services is limited. An estimated 19 million women of reproductive age in the US live in counties with fewer than one health center for every 1,000 women and are considered to be in need of publicly-funded contraception. For people living in these medically underserved areas, pharmacies could be leveraged to broaden contraceptive access.

Over-the-Counter Oral Contraception

On July 13, 2023, the FDA approved Opill for OTC availability. It is the first time a daily-use oral contraceptive pill has been approved in the US without a prescription. Emergency contraceptive pills such as Plan B and levonorgestrel generic pills have been available OTC but are not recommended for daily use. Opill became available for purchase in stores and online in the spring of 2024.

Awareness of Opill is generally still low, with just a quarter (26%) of women ages 18 to 49 saying they have heard of the newly approved daily oral contraceptive pill shortly after it became available for sale in 2024. Larger shares of women ages 26 to 35 say they have heard of Opill (30%) compared to women ages 36 to 49 (24%) according to the KFF Women’s Health Survey fielded in May and June 2024. Smaller shares of Black (21%) and Hispanic (23%) women say they have heard of the new oral contraceptive compared to White women (29%).

Research suggests that OTC oral contraceptives could especially expand access to populations who have historically faced barriers accessing contraceptive care, such as young adults and adolescents, those who are uninsured, and those living in contraceptive deserts or areas with limited access to health centers offering the full range of contraceptive methods. However, smaller shares of women who are uninsured (17%) and who live in rural areas (21%) are aware of Opill compared to those with private insurance (29%) and those living in urban or suburban areas (27%).

While Opill is a progestin-only pill, other hormonal contraceptive pills are in development or in the FDA review pipeline for over-the-counter status. Another pharmaceutical company, Cadence, has submitted to the FDA to get the first OTC combined oral contraceptive pill (COC), Zena, on the market in the U.S.

Pharmacist Prescribing

As of February 2025, 35 states and DC had passed laws (Appendix Table 1) enabling pharmacists to prescribe self-administered hormonal contraception — such as oral contraceptive pills, the DMPA injection, the patch, and the ring. Of these states, 34 states have implemented these pharmacist prescription laws (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1).

All of these states allow pharmacists to prescribe oral contraceptives, but vary in other details, such as the type of prescriptive authority, minimum age requirements for the patient, the type of contraceptive permitted, the length of the supply, and whether the patient needs a prior prescription from a physician.

There are generally four different policy pathways states use to expand pharmacists’ scope of practice: collaborative practice agreements (6 states), standing order (9 states), statewide protocol (14 states), and prescriptive authority (5 states) (Table 1). These four mechanisms authorize pharmacists to prescribe and dispense hormonal contraceptives with varying degrees of authority, from collaborative practice agreements being the most restrictive to prescriptive authority offering pharmacists the greatest autonomy.

Pharmacy Access Across the US

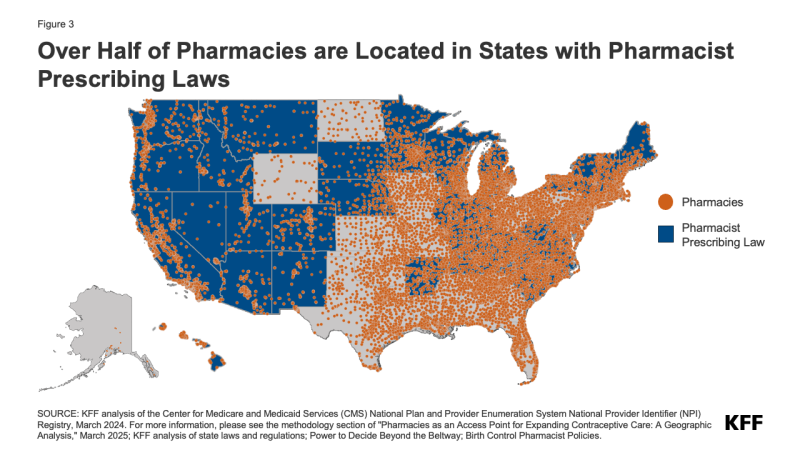

There were over 70,000 retail, clinic, and hospital-based pharmacies nationwide in March 2024 (Figure 3). It is estimated that 88.9% of people in the US live within 5 miles of their nearest pharmacy. More than 44,000 pharmacies (57% of all pharmacies) were located in states that have passed pharmacist prescribing laws and 29,913 (40% of all pharmacies) were in states that have no pharmacist prescribing laws. In states that have implemented pharmacist prescribing, pharmacist and pharmacy uptake affects the potential impact of these laws to expand contraceptive access.

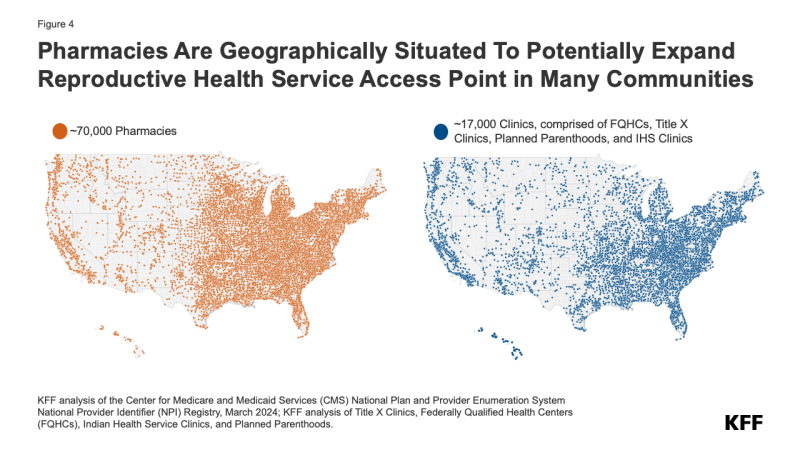

There are nearly four times as many pharmacies (70,000) in the US as publicly funded clinics (17,000). Most counties have more pharmacies than publicly funded clinics (Figure 4). Many areas with little to no clinic access have pharmacies that could potentially serve as an additional site to obtain hormonal contraceptive care for people who may not be able to physically get to a clinic for their services. Given the sheer number of sites and geographic spread, pharmacies are geographically situated to expand reproductive health service access points — particularly in areas that currently have no or little access to publicly funded clinics (Figure 4).

Although most counties have both pharmacies and publicly funded clinics (2,417 counties, green in map below), one in five counties have no clinics (655 counties, the two darkest blues in map below), 4% of counties have no pharmacies (152 counties, light blue and darkest blue below), and 3% have neither publicly funded clinics or pharmacies (80 counties, darkest blue in map below) (Figure 5).

Some estimates have found that 19 million women of reproductive age in the US live in counties with fewer than one health center for every 1,000 women and are estimated to be in need of publicly funded contraception. This KFF analysis specifically looks at women of reproductive age who live under the FPL in each of these counties and finds that 3.8 million women of reproductive age with incomes under the under the FPL live in a county with no or lower access (either no clinic or fewer than one clinic to every 1000 women) to publicly-funded clinics offering contraceptive care. Nearly half of those women (1.8 million) live in states that do not have pharmacist prescribing laws. In the broadest scenario where all states have pharmacist prescribing laws and if all pharmacies offered this care, the share who are classified as having no or low contraceptive access could plummet and the share with broadened access to contraceptive options like the pill, ring, patch, or shot could grow considerably.

When considering pharmacies as access points for contraceptive care, the analysis shows that even counties with lower comparative access were those with fewer than one clinic or pharmacy to every 250 women of reproductive age under the FPL. In many counties, pharmacies could function as a point of service for hormonal contraceptive care and potentially alleviate some of the challenges with accessing contraceptive care, even in locations where there is an existing clinic (Figure 6). In these places, women in low-income households who are interested in obtaining hormonal contraceptives at a pharmacy could do so, and those who might otherwise utilize clinic services for those same products might opt to go to the pharmacy, potentially expanding clinics’ capacity to take on more patients and serve those who require clinical care.

Challenges and Barriers

Pharmacist prescribing laws, pharmacist and pharmacy uptake of these policies, OTC oral contraception, and patient knowledge and uptake all play an important role in the availability and efficacy of pharmacies as a contraceptive care access point. There are, however, many implementation challenges beyond enacting policies to broaden the role of pharmacists and pharmacies as access points for hormonal contraceptive methods.

Reimbursement

Some states require coverage parity or payment for services such as counseling that go beyond insurance coverage of just the contraceptive supply or product. The counseling generally entails a self-screening form for patients to fill out, where patients may be asked a range of questions, from whether they have had a miscarriage or abortion in the last seven days, to medical history questions about diabetes, or migraines, or previous negative interactions with hormonal contraceptives. This may be accompanied by a blood pressure screening. For example, California requires Medicaid (but not commercial plans) to pay for pharmacist contraceptive counseling. New Mexico requires parity in payment for contraceptive counseling in all group health plans so that pharmacists are reimbursed for their time for counseling at the same rate as other clinicians offering the same services. Colorado has a more limited payment parity policy and only requires payment parity for pharmacists in Health Provider Shortage Areas. Some states, like Utah and Minnesota, have pharmacist prescribing policies, but do not formally address payment for the services provided by pharmacists other than the usual dispensing fee for the contraceptive prescription. This is a disincentive for pharmacies and pharmacists to offer these services even if the state has broadened its scope of practice. As a result, even if the costs of the method are fully covered by their plan, patients will be left with out-of-pocket costs for obtaining contraceptive care at pharmacies. These services, however, would typically be covered if they sought contraceptive care from a non-pharmacist clinician.

Uptake Of Pharmacist Prescription and Training

In order to prescribe contraception, pharmacists must complete additional education requirements, which vary by state, and often include several hours of continuing education from an accredited training program. Beyond certification, pharmacists would also need to work at a pharmacy that is willing to offer pharmacist prescription of contraceptives to their customers.

A survey of pharmacists in Oregon conducted in 2015, just before Oregon implemented its prescribing law, found that over half (57%) of pharmacists were interested in prescribing contraception. However, pharmacy staffing shortages, liability concerns, and need for additional training were identified as the three largest barriers to pharmacist participation in prescribing contraceptives. A more recent national study of community pharmacists from 2021 found that a majority (65%) were interested in prescribing hormonal contraception. Pharmacists in this survey, however, expressed similar concerns about safety (e.g. patients not obtaining health screenings), liability, and time constraints, as well as lack of payment or reimbursement for services rendered.

Successful implementation also requires public information and education about the availability and safety of pharmacist-prescribed contraceptives. From the patient perspective, they must be aware of, able to afford, and be comfortable with accessing contraceptive care from a pharmacist. A report from the Birth Control Pharmacist describes a need for public awareness campaigns that this service exists and points out that although there can be media coverage when a state passes a pharmacist prescribing law, delays in implementation and lack of full provider uptake translates into lack of public knowledge about pharmacist prescribing as an option or where to find this service. A Manatt report highlights other successful programs focused on pharmacist prescribing, such as New Mexico’s work with community-based organization, Bold Futures, to expand access to contraceptive counseling and prescription in a pharmacy setting, and North Dakota’s work on ONE Rx, which promoted pharmacist prescription of naloxone.

Interviews with patients have identified several benefits of pharmacist prescribing, such as trusting pharmacists to walk through the benefits and side effects of various types of birth control methods and convenience of a pharmacy, especially when the cost to see a doctor or limited clinic hours/availability poses a barrier. However, patients also identified concerns with a lack of privacy at pharmacies in areas where everyone knows each other, and a need to continue to see a primary care provider.

OTC Contraception

The OTC availability of Opill and levonorgestrel emergency contraceptive pills adds to the options available to those seeking contraceptives in a pharmacy setting. However, the extent of the uptake of OTC oral contraceptives will rely on both access and affordability. Retailers choose whether and how to stock Opill. Those who sell it also need to decide the supply options (one, three, or six-month packs) to stock, which may affect the purchase price . Also, as with emergency contraception, many retailers could choose to keep Opill in a locked case on the shelf or behind the pharmacy counter, which could create additional access barriers.

The suggested retail price for Opill is $19.99 for a one-month supply or $49.99 for a three-month supply. Nine states require state-regulated private health plans and/or Medicaid to cover at least some OTC contraceptive methods without a prescription. However, states have limited authority to regulate contraceptive coverage for many plans. The ACA contraceptive coverage requirement largely falls to the federal government, as they have the authority to regulate the contraceptive coverage mandate in the ACA that affects the majority of plans in the U.S. A Biden Administration proposed regulation intended to expand contraceptive coverage for people with private insurance (and many with Medicaid) for OTC oral contraceptives such as Opill, male condoms, and emergency contraceptive pills without a prescription and without cost-sharing at in-network pharmacies, but this was rescinded and never finalized.

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their input on this brief: Adam Leive, PhD and Dorothy Kronick, PhD of the Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley; Brigid Groves, PharmD and E. Michael Murphy, PharmD of the American Pharmacists Association.

Sample Scenarios

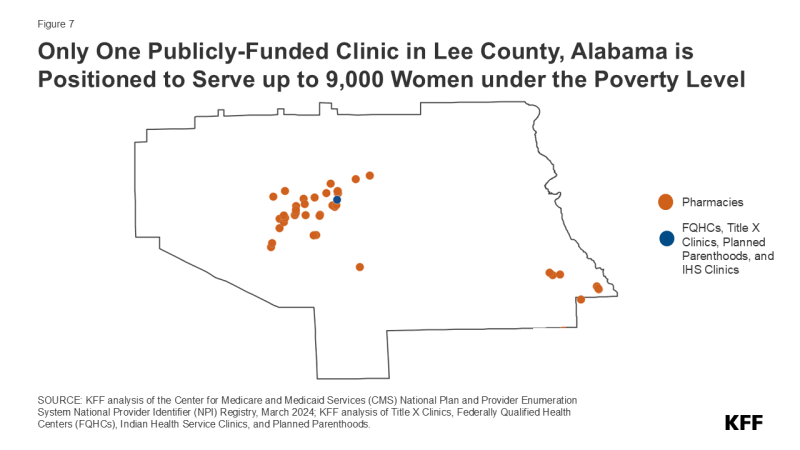

KFF identified examples of counties where access could be improved most from the passage of pharmacist prescribing laws, expanded clinic funding, and pharmacist uptake of prescribing laws.

Pharmacist Prescribing Law Could Expand Access

Lee County, Alabama, with one Title X clinic and no federally qualified health centers, has the most women of reproductive age living under the FPL per clinic of any county in the US. Lee County is a HRSA designated Medically Underserved Area and, according to a George Washington University US Prescription Contraception Workforce Tracker, only has 87 contraceptive prescribers to 41,324 total women of reproductive age. These prescribers are defined as primarily obstetrician/gynecologists (OBGYNs), family medicine physicians, and advanced practice nurses who have provided at least 10 total prescriptions for the pill, patch, or ring. Alabama does not have a pharmacist prescription law; however, if a law were passed, it is estimated that the nearly 30 pharmacies in Lee County could help bridge the contraceptive prescriber gap (Figure 7).

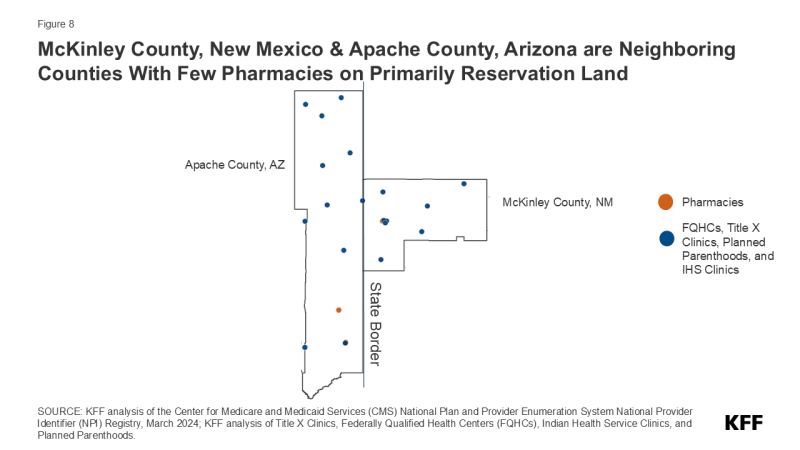

The Role of The Indian Health Service

Many of the counties that have no or low access to pharmacies are those with a high population of American Indian and Alaskan Native people, a historically underserved and marginalized population. In these places, Indian Health Service clinics provide much, if not all, of the contraceptive care options offered to the community. McKinley County, New Mexico and Apache County, Arizona, are neighboring counties in two states that both have pharmacist prescribing laws (Figure 8). In these counties, however, pharmacy uptake would not help address their medically underserved area designation nor expand access to contraceptive care, simply because there are not enough pharmacies in those communities to do so. These counties and similar counties would need additional clinic service sites, rather than expanded pharmacy uptake, to improve access to contraceptive care for women with low incomes.

Pharmacist Prescribing as A Stopgap Measure

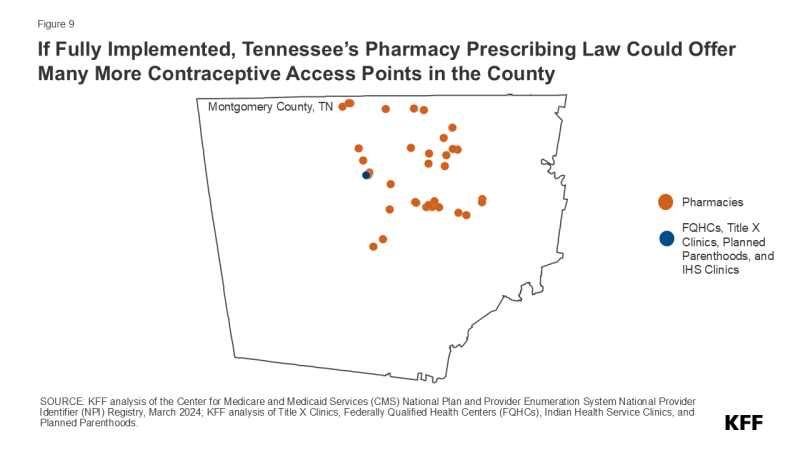

Montgomery County, Tennessee has many more pharmacies than clinics (Figure 9). According to the GW Tracker, Montgomery County has 152 total prescribers to a total of 51,180 women aged 15-44. Tennessee’s pharmacist prescriber law went into effect in 2019 — the same year the prescriber data starts. However, there were no pharmacists prescribing at least 10 prescriptions for the pill, patch, or ring in Montgomery County in 2022. Low participation could be because of low uptake of pharmacists in prescribing and dispensing contraception, lack of participation of pharmacies in offering this service, or low consumer awareness or interest in using the services. The legislation alone has not been enough to expand the number of contraceptive prescribers in the county.

Methods

Overview

The pharmacy location addresses (as of March 10, 2024) were pulled from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) National Plan and Provider Enumeration System National Provider Identifier (NPI) Registry based on previous research by E. Michael Murphy, Lucianne West, and Nimit Jindal’s paper, “Pharmacist Provider Status: Geoprocessing Analysis of Pharmacy Locations, Medically Underserved Areas, Populations, and Health Professional Shortage Areas” (November 2021).

Pharmacy Data

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) requires that every health care provider and organization have an NPI number — Type 1 numbers are assigned to specific providers and Type 2 numbers are assigned to provider locations. Adhering to the Murphy et. al methodology, we pulled all providers with the taxonomy code 3336C0003X, which designates a community or retail pharmacy, excluded all Type 1 providers, removed duplicate addresses and phone numbers, and removed all territories. Then, after extensive data cleaning to prepare the data for geocoding, the data was geocoded using R, with a cascade method which first tried the US Census Geocoder, then Open Street Maps, and then Google Maps API. The remaining pharmacies that did not correctly geocode were manually checked and almost all were closed, so these closed pharmacies were removed from the database and the remaining were manually geocoded. After data cleaning and removing duplicates, we identified 74,752 pharmacies in the US.

Clinic Data

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)

The FQHC data, current as of March 2024, was pulled from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) website.

Indian Health Service (IHS) clinics

Indian Health Service Clinic locations, current as of June 2023, were obtained from the Indian Health Service (IHS) website. Although the IHS data includes a flag for FQHCs, very few of the FQHC-flagged clinics were found in the FQHC dataset, and there were several others in the FQHC data that did not have a flag. For this reason, the IHS clinics were de-duplicated from the FQHCs by geographic location (clinics with the same or similar name within a half mile of each other).

Title X clinics

The Title X Clinic data from the Office of Population Affairs (OPA) in Health and Human Services (HHS) is current as of February 2024. Mobile clinics were excluded and duplicates based on location were removed. Title X clinics that are also FQHCs were counted as FQHCs to avoid double counting. Tennessee did not have any clinics reflected in the database due to the state’s refusal to comply with federal Title X funding rules requiring clinics to provide referral for abortion.

Planned Parenthood clinics

The Planned Parenthood dataset is an internally collected KFF dataset pulled from the Planned Parenthood Federation America (PPFA) website. This data is current as of March 2024.

Women of Reproductive Age Under the Federal Poverty Line

Women of reproductive age under the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) was calculated using the 2022 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables: B17001, Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months by Sex by Age from the US Census website. Counts for females 15-49 under the FPL, over the FPL, and total by county were summed. To maintain data quality, any counties that had fewer than 50 women of reproductive age under the FPL were suppressed.

In 2024, the FPL was an annual income of $15,060 per year for a family of 1 and $25,820 for a family of 3. In 2022, the last year used in the 5-year American Community Survey sample cited, it was $13,590 for a family of 1 and $23,030 for a family of 3.

In 2022, Connecticut made a change to its counties – going from 8 to 9, and redrawing some of the county lines. ACS released a 1-year comparison file for Connecticut with these new counties, which is used in lieu of the 5-year in this analysis. The full 5-year ACS file with the new Connecticut counties will not be available until 2027. The 5-year was used for all other states as the sample size is larger.

A Note About Sex and Gender Language

Throughout this research, we refer to women of reproductive age. This is a nationally collected metric often used in reproductive health research. This is not a full representation of people who seek access to the full range of contraceptive methods: people of all gender identities use contraception.