How Many Foreign NGOs Are Subject to the Expanded Mexico City Policy?

Key Points

- On January 23, 2017, President Trump reinstated the Mexico City Policy (see KFF explainer). In the past, the policy required foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to certify that they would not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning,” using funds from any source, as a condition for receiving U.S. government global family planning assistance; it applied to foreign NGOs receiving funding directly, as prime recipients, and indirectly, as sub-recipients. It also required U.S. NGOs to ensure that their foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance.

- Under the Trump Administration, the policy’s scope has been significantly expanded to include most other U.S. bilateral global health assistance, beyond just family planning funding, and additional funding agreements.

- At this time, many questions remain about the potential impact of the expanded policy. One key unknown is the size of the universe of affected NGOs. To begin to answer this question, we analyzed data on U.S. global health assistance obligated over a recent three-year period (FY 2013-FY 20151 ) to identify the number of foreign NGOs that received funding. Our findings should be considered a minimum estimate, since we were only able to include a sample of NGO sub-recipients. Our analysis finds that:

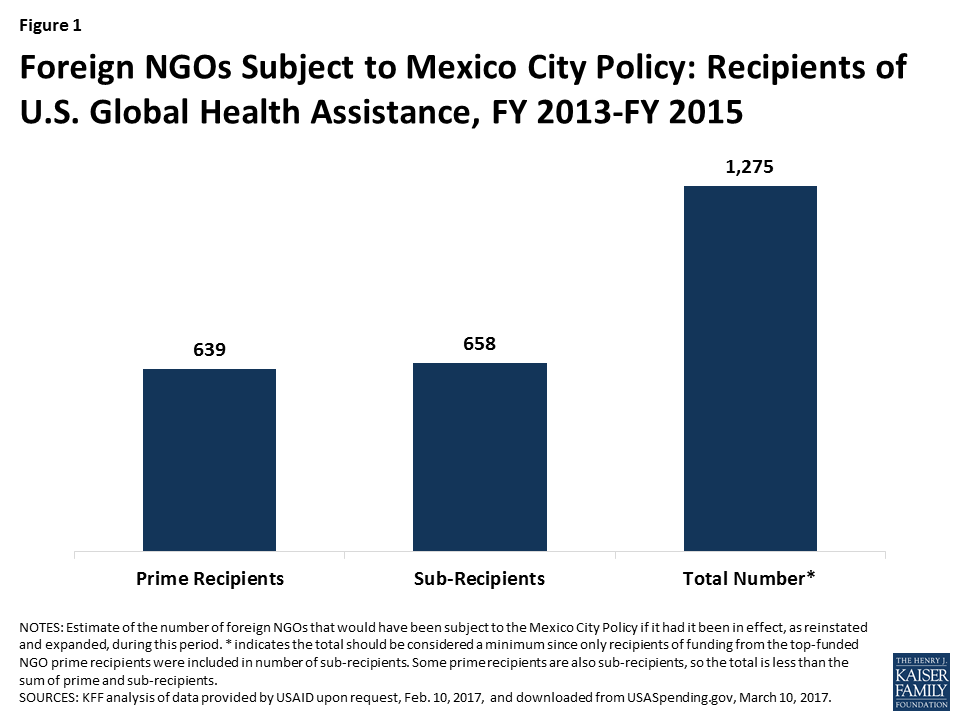

- If the policy had been in effect during this time, at least 1,275 foreign NGOs – half as prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance and half as sub-recipients – and approximately $2.2 billion in funding directed to these NGOs would have been subject to the policy.

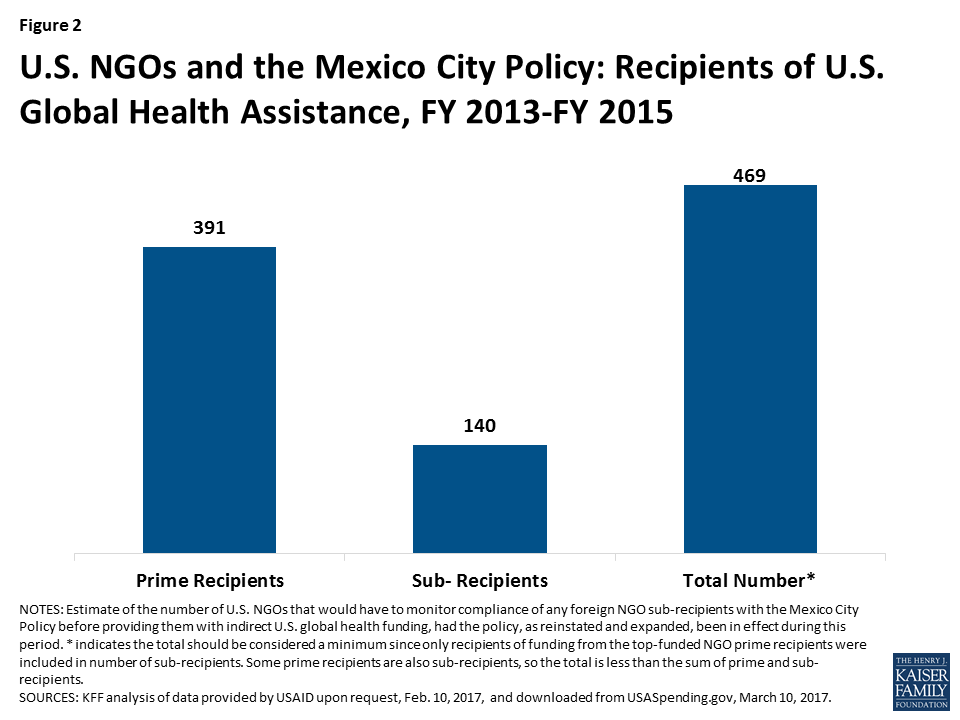

- In addition, at least 469 U.S. NGOs receiving U.S. global health assistance would have been required to ensure that their foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance.

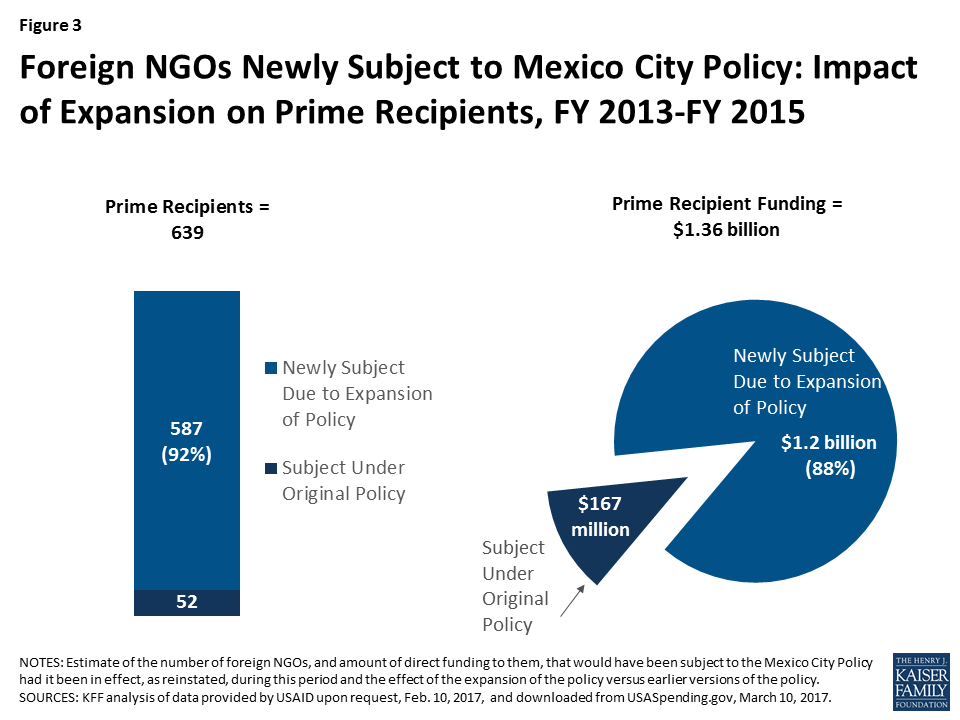

- The expansion of the policy greatly increased its reach. Among prime recipients alone, most affected foreign NGOs (92%) and funding (88%) would not have been subject to the policy under its pre-expansion terms.

- Ultimately, while it is too soon to know the actual impacts of the expanded policy on the people served by U.S. global health programs, our analysis suggests that, at a minimum, a significant number of NGOs will be subject to the policy.

Issue Brief

Introduction

On January 23, 2017, President Trump reinstated the Mexico City Policy (MCP), renamed “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance” (see the KFF explainer). In the past, when in effect, the policy required foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs)2 to certify that they would not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” using funds from any source (including non-U.S. funds) as a condition for receiving U.S. government global family planning assistance. This included both foreign NGOs receiving U.S. funding directly, as “prime recipients,”3 or indirectly, as “sub-recipients.”4 Furthermore, it required U.S. NGOs to ensure that any foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance. Under the Trump Administration, the policy’s scope has been significantly expanded beyond these conditions. It now includes most other U.S. bilateral global health assistance and, pending the outcome of a rule-making process, additional funding agreements (in the past, it applied to cooperative agreements and grants;5 the Administration intends to also apply it to contracts).6 As such, the policy applies to more than $7 billion, to the extent that such funding is ultimately provided to foreign NGOs, directly or indirectly.

At this time, many questions remain about the potential impact of the expanded policy. One key unknown is the size of the universe of affected NGOs. We undertook this analysis to begin to answer that question. Using ForeignAssistance.gov data obtained from USAID,7 we identified NGO prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance in the most recent three-year period for which such data were available (FY 2013- FY 2015).8 We categorized them into U.S. and foreign NGOs. We included bilateral global health funding obligated by USAID (including funding that had been transferred to USAID from the Department of State) through grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts (contracts were included even though the rule-making process has not yet been initiated9 ) that would have been subject to the MCP. We then analyzed data from USAspending.gov to identify NGO sub-recipients of the top NGO prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance over the same period.10 This allowed us to create a database of foreign NGOs that would have been subject to the expanded MCP if the policy had been in effect during that three-year period, as well as U.S. NGOs that would have been required to ensure that their foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance. We also quantified the effect of expanding the policy beyond its prior conditions on the number of affected NGOs.

Our findings should be considered a minimum estimate since we only looked at sub-recipients of the top prime recipients of funding (and not all prime recipients report sub-recipient data). Indeed, based on a prior analysis we conducted, most U.S. global health assistance flows first to U.S.-based organizations before reaching foreign NGOs.11 In addition, we did not include NGOs that received global health funding transferred from State or other agencies to the Department of Health and Human Services in this analysis (although such funding is subject to the policy12 ). At the same time, it is important to note that while all foreign NGOs will be required to certify compliance with the MCP as a condition of receiving U.S. global health assistance, only some carry out activities that are prohibited by the policy; however, available data did not allow us to assess this issue. See full methodology in Appendix A.

Findings

Overview

We found that had the expanded Mexico City Policy been in effect during the FY 2013 – FY 2015 period:

- At least 1,275 foreign NGOs – 639 as prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance and 658 as sub-recipients – would have been subject to the policy.13 See Figure 1.

- Together, they accounted for approximately $2.2 billion14 in funding subject to the policy, including $1.36 billion to prime recipients and $831 million15 to sub-recipients.

- This funding supported foreign NGO efforts in at least 91 countries, including many countries that allow for legal abortion in at least one case not permitted by the MCP (see KFF analysis), and across all major global health program areas: family planning/reproductive health (FP/RH), maternal and child health (MCH), nutrition, HIV, TB, malaria, global health security, and other threats, including NTDs. HIV had the greatest number of foreign NGO prime recipients (470), followed by MCH (105) and FP/RH (82). See Table 1.

| Table 1: Foreign NGO Prime Recipients: Number and Amount of Program Area Funding Subject to Mexico City Policy, FY 2013-FY 2015 | ||

| Program Area | Number of Prime Recipients Subject to MCP* | Prime Recipient Funding Subject to MCP* |

| FP/RH | 82 | $175 million |

| MCH | 105 | $75 million |

| Nutrition | 15 | $6 million |

| HIV | 470 | $873 million |

| Tuberculosis | 30 | $194 million |

| Malaria | 55 | $31 million |

| Global Health Security | 43 | $1 million |

| Other Threats, inc. NTDs | 5 | $6 million |

| TOTAL | 639 | $1.36 billion |

| NOTES: * Does not include funding not subject to the MCP, including support for the Food for Peace (FFP) and American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA) programs and certain WASH efforts as well as support via agreements other than cooperative agreements, grants, and contracts. Sub-recipients not included. | ||

- HIV also accounted for the greatest amount of affected funding ($873 million), though this represented just 8% of HIV program area funding obligated over the period. The TB program had the greatest share of its program funding affected (35%), though this represented a much smaller amount of funding ($194 million). For FP/RH funding, 11% (or $175 million) was subject to the policy.16 See Table 2. These variations largely reflect the extent to which different program areas rely on foreign NGOs as prime recipients of aid, which was most common in the case of the TB program.

| Table 2: Foreign NGO Prime Recipients: Amount & Share of Program Area Funding Subject to Mexico City Policy, FY 2013-FY 2015 | ||

| Program Area | Total Program Area Funding | Prime Recipient Funding Subject to MCP* (% of Total) |

| FP/RH | $1.54 billion | $175 million (11%) |

| MCH | $2.27 billion | $75 million (3%) |

| Nutrition | $490 million | $6 million (1%) |

| HIV | $11.24 billion | $873 million (8%) |

| Tuberculosis | $554 million | $194 million (35%) |

| Malaria | $1.62 billion | $31 million (2%) |

| Global Health Security | $388 million | $1 million (<1%) |

| Other Threats, inc. NTDs | $413 million | $6 million (2%) |

| NOTES: * Does not include funding not subject to the MCP, including support for the Food for Peace (FFP) and American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA) programs and certain WASH efforts as well as support via agreements other than cooperative agreements, grants, and contracts. Sub-recipients not included. | ||

- In addition to foreign NGOs, at least 469 U.S. NGOs that received U.S. global health assistance during this period (including 391 who were prime recipients) would have been required to ensure that their foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance. See Figure 2.

Newly Subject NGOs and Funding

Looking at prime recipients only, we also quantified the effect of expanding the policy beyond its prior conditions on the number of affected NGOs (available data on sub-recipients did not permit this level of analysis). We found that the expansion of the policy beyond family planning assistance and to contracts greatly increased its reach:

- Among prime recipients alone, most affected foreign NGOs (587 of 639, or 92%) and most funding ($1.2 billion of $1.36 billion, or 88%) would not have been subject to the policy under its pre-expansion terms. See Figure 3.

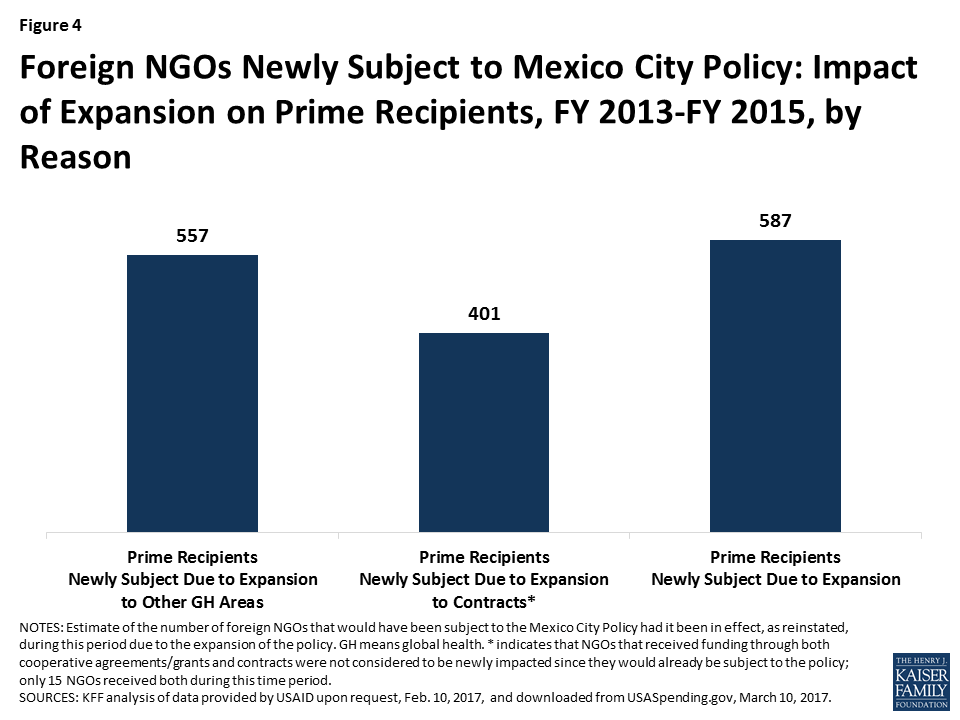

- Of the 587 newly subject to the policy, 557 received non-family planning global health assistance only (i.e., MCH, nutrition, HIV, TB, malaria, global health security, and other threats, including NTDs) and 401 received funding through contracts only.17 ,18 See Figure 4.

- Of the 391 U.S. NGOs prime recipients that would have had to ensure certification by and monitor compliance of their foreign NGO sub-recipients, most (321, or 82%) would have had to do this for the first time due to the expansion.19

Conclusion

Our analysis finds that the expansion of the Mexico City Policy by the Trump Administration greatly increased its reach, affecting a much greater number of foreign NGOs and funding than prior iterations. This is particularly the case given the Administration’s intent to expand the policy to include contracts, pending the outcome of a rule-making process. Importantly, while our analysis provides an initial estimate of the number of foreign NGOs that would be subject to the policy, it does not represent the entire universe, due to data limitations in identifying sub-recipients of U.S. support. Such an accounting would be important for more fully understanding the scope and impact. Furthermore, this analysis does not assess the extent to which affected NGOs carry out activities prohibited by the policy, some of whom may choose to end such activities or forgo U.S. funding. Ultimately, this next layer of analysis will be critical to assessing the impact of the expanded policy on the people served by U.S. global health programs, as the policy continues to be rolled-out.

Appendix

Methodology

Using ForeignAssistance.gov data obtained from USAID,20 we identified NGO prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance in the most recent three-year period for which such data were available (FY 2013 – FY 2015).21 We categorized them into U.S. and foreign22 NGOs. We included bilateral global health funding obligated by USAID (including funding that had been transferred to USAID from the Department of State) through grants, cooperative agreements, and contracts. We then analyzed data from USAspending.gov to identify NGO sub-recipients of the top NGO prime recipients of U.S. global health assistance over the same period. This allowed us to create a database of foreign NGOs that would have been subject to the expanded MCP if the policy had been in effect during that three-year period, as well as U.S. NGOs that would have been required to ensure that their foreign NGO sub-recipients were in compliance. We also quantified the effect of expanding the policy beyond its prior conditions on the number of affected NGOs.

Our findings should be considered a minimum estimate since we only looked at sub-recipients of the top prime recipients of funding (and not all prime recipients report sub-recipient data).23 In addition, we did not include NGOs that received global health funding transferred from State or other agencies to the Department of Health and Human Services in this analysis (although such funding is subject to the policy).

Funding totals shown in this report represent net obligations. We only included funding subject to the policy and for health activities in program areas subject to the policy.24 Funding that is exempted from the policy (e.g., funding provided to international organizations, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, certain water and sanitation activities, the American Schools and Hospitals Abroad (ASHA) program, the Food for Peace (FFP) program, and humanitarian assistance) was not included. The exceptions were funding provided to entities that are government-run hospitals25 and entities that qualify for a “commercial exemption”26 under the current policy.

For prime recipients, we used information in the ForeignAssistance.gov data on health program area, responsible office, and activity descriptions to identify funding amounts subject to the policy, which was available for most but not all recipients. For sub-recipients, we used information in the USAspending.gov data on the funded agreement and activity, as well as related additional research, to identify funding amounts subject to the policy. The funded agreement must have been included in and identified as “health,” at least in part, in the ForeignAssistance.gov prime recipient data for the funding to have been considered subject to the policy at the sub-recipient level.

NGOs are defined by USAID as “any non-governmental organization or entity, whether non-profit or profit-making, receiving or providing USAID-funded assistance under an assistance instrument or contract.”27 This includes institutions of higher education,28 hospitals, non-profit non-governmental organizations, and commercial organizations.29 ,30 For prime recipients, we used information in the ForeignAssistance.gov data on organization type and country of origin to assign organizations into these categories; where information was not available, we did additional research. For sub-recipients, we conducted additional research to categorize organizations as NGOs and used information in the USAspending.gov data on country of origin to assign them to the U.S. or foreign category.

Endnotes

- At the time this project began, this was the most recent complete data available at the awardee level. Complete data from FY 2016 may now be available. ↩︎

- Defined by USAID as “a for-profit or not-for-profit non-governmental organization that is not organized under the laws of the United States, any State of the United States, the District of Columbia, or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or any other territory or possession of the United States.” USAID: “Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303maa, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303maa; “Standard Provisions for Non-U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303mab, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303mab. ↩︎

- A prime recipient receives money directly from the U.S. government after signing a cooperative agreement, grant, contract, or other funding agreement with the U.S. government. ↩︎

- A sub-recipient receives money from a prime recipient (see above) to carry out the original agreement. ↩︎

- With some exceptions – see endnote #9 for exception about “grants under contracts.” ↩︎

- USAID, “Implementation of Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (formerly known as the Mexico City Policy),” Executive Message to USAID/General Notice Distribution List, May 15, 2017. As of May 15, the policy applies to all new USAID grants and cooperative agreements that provide global health assistance, as well as to all existing grants and cooperative agreements that provide global health assistance when such agreements are amended to add new funding. As of March 2, the same holds true for USAID grants and cooperative agreements that provide family planning assistance. USAID: “Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303maa, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303maa; “Standard Provisions for Non-U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303mab, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303mab. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of USAID FY 2013 – FY 2015 transaction data provided via personal communication with USAID staff of the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard (ForeignAssistance.gov), Feb. 10, 2017. ↩︎

- At the time this project began, this was the most recent complete data available at the awardee level. ↩︎

- USAID, “Implementation of Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (formerly known as the Mexico City Policy),” Executive Message to USAID/General Notice Distribution List, May 15, 2017. As of the date this brief was published, the policy is not in effect with regard to contracts. A rulemaking process is required to apply the policy to contracts, which may take some time. The exception to this is “grants under contracts,” which were previously subject to the policy when last in effect and are covered by the reinstated policy at this time; they are essentially grants made to sub-recipients by prime recipients of contracts. ↩︎

- Among the top 20 NGO prime recipients, as measured by funding that could have been subject to the MCP had it ultimately been directed to foreign NGOs, 14 reported providing global health funding to sub-recipients, but only 13 were included in this analysis (there was an apparent error in the funding amount reported by the one that was excluded); their sub-recipients that were NGOs were included in this analysis. KFF analysis of data downloaded from USAspending.gov, March 10, 2017. ↩︎

- See, for example, KFF, Key Implementers of U.S. Global Health Efforts, Sept. 6, 2016. ↩︎

- CDC, “Additional Requirement – 35: Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance,” webpage, updated July 13, 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/grants/additionalrequirements/ar-35.html; NIH, “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance,” Notice Number: NOT-OD-17-083, June 23, 2017, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-17-083.html. ↩︎

- Some prime recipients are also sub-recipients, so the total is less than the sum of prime and sub-recipients. ↩︎

- This $2.2 billion represented 17% of global health assistance that the policy might have applied to during this period if it had ultimately been provided entirely to foreign NGOs during this period (approximately $12.54 billion). ↩︎

- Of this, approximately $12 million was provided to other foreign NGOs (sub-recipients) by a foreign NGO prime recipient; this funding may or may not overlap to some degree with that prime recipient’s funding that was included in the foreign NGO prime recipient funding total. ↩︎

- This does not represent the entire amount of program funding that would have been subject to the policy. Most FP/RH funding was provided to U.S. NGO prime recipients, which may have provided funding to foreign NGO sub-recipients in turn; as with other global health funding provided to U.S. NGO prime recipients, funding provided indirectly to foreign NGOs would have been subject to the Mexico City policy. ↩︎

- NGOs that received funding through both cooperative agreements/grants and contracts were not considered to be newly impacted since they would already be subject to the policy; only 15 NGOs received both during this time period. ↩︎

- See State Department, “Subject: Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance,” Federal Assistance Management Advisory Number 2017-01; USAID, “USAID Notice: Implementation of Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (formerly known as the Mexico City Policy),” Executive Message, May 15, 2017. ↩︎

- Additionally, some of the 70 U.S. NGOs that would have been required to ensure prior certification of their foreign NGO subawardees for FP/RH funding under prior policy would have also had their responsibilities expanded under the reinstated policy to include subawardees of their non-FP/RH funding via cooperative agreements and grants and/or any global health funding via contracts. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of USAID FY 2013 – FY 2015 transaction data provided via personal communication with USAID staff of the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard (ForeignAssistance.gov), Feb. 10, 2017. ↩︎

- At the time this project began, this was the most recent complete data available at the awardee level. ↩︎

- A foreign NGO is defined by USAID as an NGO “that is not organized under the laws of the United States, any State of the United States, the District of Columbia, or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, or any other territory or possession of the United States.” USAID: “Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303maa, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303maa; “Standard Provisions for Non-U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303mab, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303mab. ↩︎

- Among the top 20 NGO prime recipients, as measured by funding that could have been subject to the MCP had it ultimately been directed to foreign NGOs, 14 reported providing global health funding to sub-recipients, but only 13 were included in this analysis (there was an apparent error in the funding amount reported by the one that was excluded); their sub-recipients that were NGOs were included in this analysis. KFF analysis of data downloaded from USAspending.gov, March 10, 2017. ↩︎

- See USAID, “Implementation of Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (formerly known as the Mexico City Policy),” Executive Message to USAID/General Notice Distribution List, May 15, 2017; USAID, “Standard Provisions for U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303maa, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303maa; USAID, “Standard Provisions for Non-U.S. Nongovernmental Organizations: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 303,” ADS Reference 303mab, partial revision May 22, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303mab. ↩︎

- PAI, What You Need to Know About the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance Restrictions on U.S. Global Health Assistance, Oct. 5, 2017. ↩︎

- For the purchase of goods or services. ↩︎

- USAID, Glossary of ADS Terms, partial revision, April 30, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1868/glossary.pdf. ↩︎

- Foreign public educational institutions were excluded from our analysis, since they are exempt from the Mexico City Policy as government-operated institutions. ↩︎

- USAID, Grants and Cooperative Agreements to Non-Governmental Organizations, ADS Chapter 303, partial revision, April 3, 2017, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/300/303. ↩︎

- Not subject to the Mexico City Policy are, among others: agreements with national and sub‐national governments, including foreign public universities; public international organizations; and other multilateral entities in which sovereign nations participate (such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria, and Tuberculosis, and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance). USAID, “Implementation of Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance (formerly known as the Mexico City Policy),” Executive Message to USAID/General Notice Distribution List, May 15, 2017. A Department of State memo included a similar statement; see the Department of State, “Subject: Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance,” Federal Assistance Management Advisory Number 2017-01, May 15, 2017. ↩︎