Community Health Centers and Family Planning in an Era of Policy Uncertainty

Executive Summary

Introduction. Community health centers play a major role in furnishing publicly funded reproductive health care, including family planning services, to women living in low-income and medically underserved communities. Community health center patients are overwhelmingly low-income, members of a racial or ethnic minority group, and disproportionately female. In 2016, nearly one-third of all low-income women of childbearing age obtained care at a community health center. Since the health centers program was first enacted into law in 1975, voluntary family planning has been a required service.

Study purpose and methods. Building on earlier research conducted by George Washington University in 2011, this study examines the current state of community health centers’ family planning services. Its purpose is to assess the scope and onsite availability of family planning services, how health centers are incorporating evidence-based recommended best practices into their activities, how participation in the Title X family planning program might affect the scope and quality of health center family planning services, and to document barriers to care. The study is based on a survey, conducted between May and July 2017, of health centers in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Since health centers on average deliver care at over seven sites, the survey gave special focus to each respondent’s largest service site offering family planning services onsite. The survey yielded a 41 percent response rate.

Key findings. Virtually all health centers (97 percent) reported that their largest comprehensive medical sites offered family planning services. Among the study’s key findings:

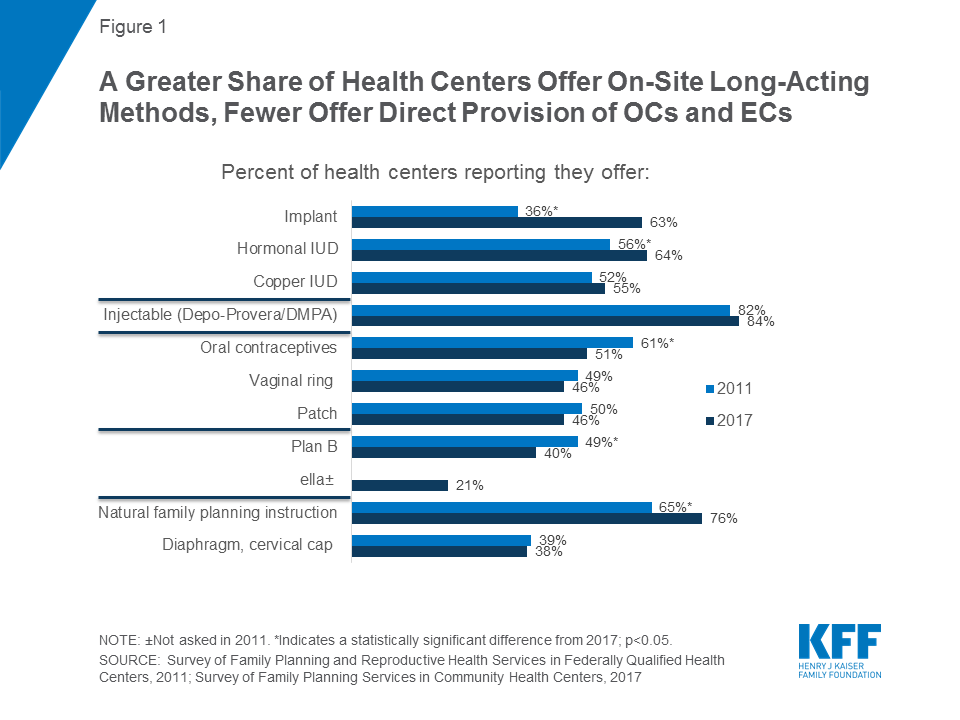

Scope and comprehensiveness of care: About half the sites provide short-acting, effective methods onsite, including oral contraceptives (OCs), the contraceptive ring, and the contraceptive patch, and over half provide long-acting methods onsite, including hormone-releasing IUDs, the copper IUD, and implant. Between 2011 and 2017, the proportion of sites offering onsite long-acting contraception rose from 36 percent to 63 percent for the implant and 56 percent to 64 percent for hormonal IUDs. Over the same time period, however, the percentage offering onsite oral contraceptives declined from 61 percent to 51 percent. Fewer than half provide emergency contraception onsite, and many do not prescribe or refer for it at all. Onsite provision of Plan B (available without a prescription) has significantly decreased from 2011. One in four health centers offers all seven of the most effective family planning methods onsite, while nearly half (48 percent) provide all seven methods either onsite or by prescription.

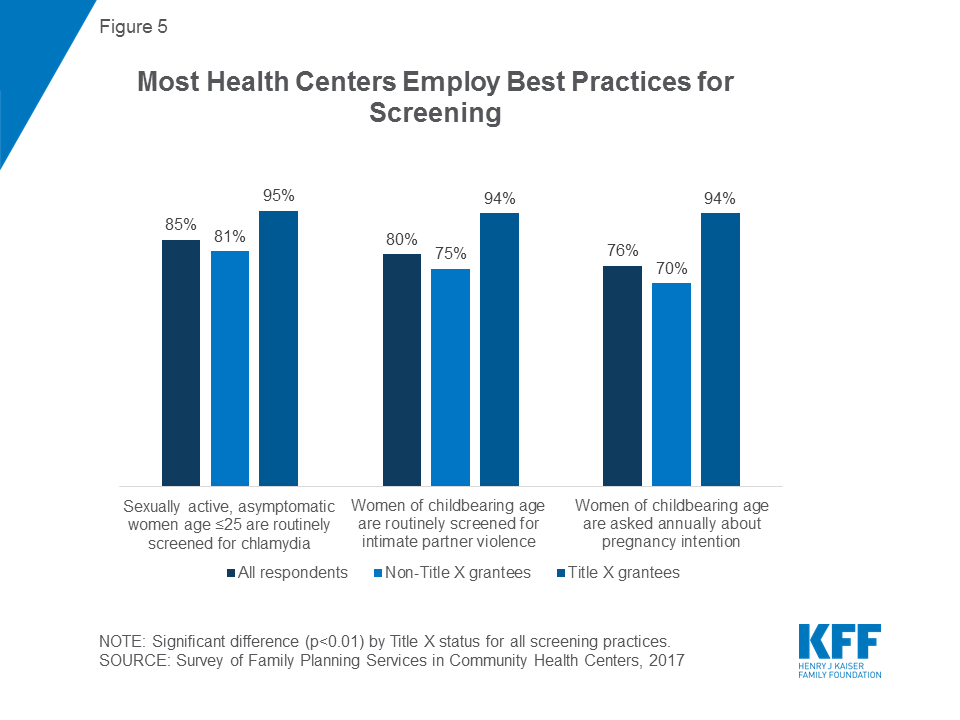

Promoting access to services and counseling. Two-thirds of health centers offer access to initial contraceptive visits on a same-day and walk-in basis. In 2017, 68 percent of health center sites offered same-day/walk-in initial contraceptive visits for new patients and 89 percent for established patients. Most health centers follow current patient screening and counseling recommendations: 76 percent report that they ask about the childbearing plans for female patients of childbearing age, 85 percent routinely screen sexually active women age 25 or younger for chlamydia, and 80 percent routinely screen women of childbearing age for intimate partner violence.

Family planning staffing. Health centers are less reliant on physicians for family planning counseling than they were in 2011. Three quarters report that physicians provide family planning counseling, down from 85 percent in 2011.

Special population services. Sixty-three percent of health centers offer services for adolescents, up substantially from 47 percent in 2011, and are more likely today than previously to maintain special confidentiality protections for minors.

The role of Title X funding: Across virtually all measures of performance, the receipt of additional Title X funding lifted performance. Twenty-six percent of respondents report that their largest family planning sites also receive Title X funding. In keeping with the more dedicated mission of Title X grantees and detailed family planning requirements of Title X, Title X-funded sites consistently show a larger range of onsite contraceptive methods across all types of methods, including natural family planning instruction and emergency contraception. Title X-funded health center sites are substantially more likely – 48 percent compared to 15 percent of sites not receiving Title X funding – to offer all seven of the most effective methods onsite. Title X-funded sites also consistently show greater incorporation of evidence-based best practice methods, including prescribing oral contraceptives without requiring a pelvic exam and use of the “quick start” method for oral contraception that ensures that women who seek it have more rapid access to effective contraception. Title X-funded sites are also more likely to follow best practices related to screening and counseling. Title X-funded sites are also far more likely – 43 percent compared to 16 percent – to have health counselors or educators providing family planning counseling.

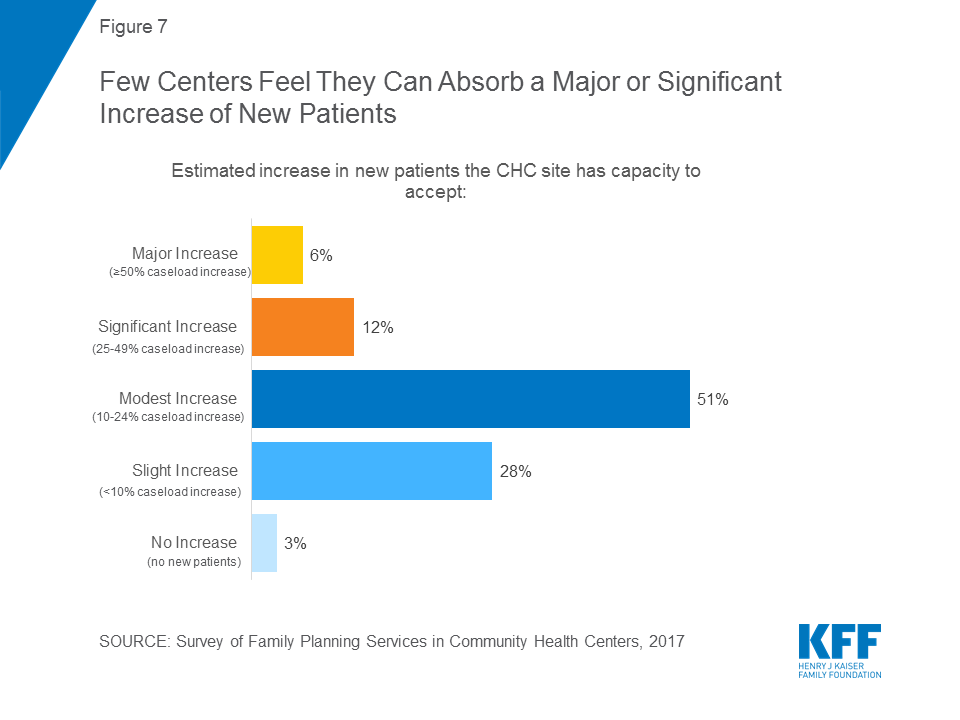

Expanded onsite services; limited additional capacity: As their services have grown – especially related to provision of long-acting contraceptives – health centers simultaneously are referring fewer patients to freestanding family planning clinics. Half of respondents reported increased demand for family planning services in the past five years, and the majority responded with staffing increases to support this demand. In 2011, 78 percent of health centers with family planning clinics in their service area reported referring patients to them; by 2017, this figure had declined to 36 percent. Sites without Title X funding more typically refer patients, whose care becomes their direct responsibility under Title X. Health centers reported limited capacity to accept new patients; 51 percent reported that they could increase patient capacity but only between 10 and 24 percent; only 6 percent reported that they could absorb a 50 percent or greater patient increase.

Expanded services; remaining barriers. Reported major barriers to meeting patients’ family planning and reproductive health needs focus on the challenges of affordability for patients and the financial resources needed to maintain a robust family planning practice. Nationally, 23 percent of health center patients remain uninsured, a percentage that is higher in non-ACA Medicaid expansion states (36 percent). Twenty-five percent reported the lack of insurance coverage among patients as a major barrier, 28 percent reported high patient out-of-pocket costs as a major barrier issue, and 19 percent reported inadequate insurance payments as a major barrier. One in four health centers (24 percent) reported the high cost of stocking contraceptives onsite as a major barrier, and twenty percent reported high patient demand for other primary care services at their largest site as a major barrier. Nineteen percent reported a lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures as a major barrier.

Implications. Community health centers are vital to low-income women’s access to primary and preventive healthcare services, including family planning services. Family planning has been a required service under the community health center program since its beginning and remains a crucial component of health care for women of reproductive age (15-44). This survey finds that since 2011, the share of health centers offering long acting contraceptive methods has grown. At the same time, health centers that also participate in the Title X program are more likely to offer a broad range of methods and engage in higher quality practices such as use of the quick start method for oral contraceptives and same day walk-in services. This suggests that targeted supplemental funding tied to clear performance expectations may yield positive, measurable results in preventive primary care. Expanding the availability of targeted family planning quality improvement funds as a direct part of the health centers program would be consistent with the Balanced Budget Act of 2018, which, in extending health center grant funding, explicitly allows HHS to spend funds on targeted primary care quality improvement. On February 23, 2018, the Trump Administration released the funding opportunity announcement (FOA) for Title X family planning grants. This funding announcement does not require that grantees adhere to evidence based standards for quality family planning that were promulgated by the Office of Population Affairs and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This study finds that health centers that participate in Title X are those that offer the highest quality family planning services. Any weakening of the evidence-based requirements for Title X grantees may result in a significant loss of access to the most effective contraceptive methods for low-income women, men, and teens.

A majority of health centers also reported in this study that they are unable to accept a major increase in new patients. This is particularly important to note in light of recent proposals to block Planned Parenthood from the Medicaid program and redirect funds to other providers, such as community health centers. The FOA for Title X funding released in February 2018 gives preference to clinics that provide primary health care and family planning services in the same location. In addition, as this survey suggests, these health centers may not have the capacity to fill the void if Planned Parenthood were excluded as a Medicaid or Title X provider.

Strategies that will elevate the standards of family planning services offered by health centers have the potential to have high impact on many of the challenges facing women’s health. Promoting the availability of high quality family planning services reduces unintended pregnancy and abortion rates, improves birth outcomes, and allows women to make informed and independent reproductive choices to improve their health and their future wellbeing.

Report

Introduction

Community health centers play a major role in furnishing reproductive health care to women living in low-income and medically underserved communities. Along with independent freestanding family planning clinics including Planned Parenthood health centers (which also may receive Title X funding), and local public health agencies, community health centers are part of a publicly supported provider network that serve an estimated one in three low-income women.1 The CDC defines family planning services as encompassing: contraception to reduce unintended pregnancy and abortion rates and promote appropriate birth spacing; pregnancy testing and counseling; infertility counseling and screening; preconception health care to promote better infant and maternal outcomes and to improve women’s and men’s health; and sexually transmitted disease (STD) screening and treatment services.2

Family planning services at community health centers are supported through a combination of patient revenues, health insurance, and grant funding, including the federal community health center program, as well as other federal, state, and local public health grants. Medicaid represents the most important source of health coverage among patients served by publicly supported clinics; in 2016, Medicaid insured two in five (42 percent) low-income women.3

This report, an update of an earlier study conducted in 2011,4 presents the key findings of a national survey of community health centers and their role in the provision of family planning and related services to low-income women, men, and teens.

Located in communities experiencing high poverty, elevated health risks, and a shortage of primary health care, community health centers offer comprehensive primary health care and adjust the fees charged to patients in accordance with their ability to pay. In recent years, community health centers have experienced steady growth primarily as a result of two major federal policy reforms: the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion; and an expanded investment in community health center grant funding under the ACA. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of community health centers grew from 1,124 to 1,367, the number of sites, from 6,949 to 10,404, and the number of patients, from 19.5 million to 25.9 million.5

Fifty-six percent of all community health center grantees are in urban communities, while the remainder are rural or suburban. Community health center patients are overwhelmingly low-income, members of a racial or ethnic minority group, and disproportionately female. In 2016, three in ten, or about 6.2 million, low-income women6 of childbearing age (ages 15-44) obtained care at a community health center.7

In recognition of the importance of family planning to population and women’s health, Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act, which authorizes the community health center program, has specified “voluntary family planning” as a required service since 1975 when8 the program was first authorized. As with other required community health center services, however, the law and implementing regulations and guidelines do not define the exact scope of services that must be provided to patients. Rather, community health centers are given significant leeway to determine the precise mix and scope of the required family planning services they will offer.9 This is in contrast with the federal Title X program, a block grant administered by the HHS Office of Population Affairs (OPA), and the only federal program specifically dedicated to supporting the provision of family planning services. In return for federal support, the Title X program requires that its grantees meet very specific performance criteria. In addition to providing women, men, and teens with a broad range of contraceptive services and supplies and other preventive, screening, and treatment services, Title X grantee clinics must follow special federal confidentiality protections and are expected to adhere to national Quality Family Planning Guidelines (QFP).10 About a quarter of all community health centers also participate in Title X; as a condition of grant eligibility, these community health centers must follow the more expansive Title X standards outlined for the provision of family planning services. The majority of community health centers, however, are bound only by the Section 330 requirements. As a result, there is considerable variation in the scope of services provided at community health centers across the country.

Study Purpose and Methodology

This study, conducted by researchers at George Washington University’s Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health and Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health Policy, and the Kaiser Family Foundation, builds on a 2011 study to examine the role of community health centers in the provision of family planning services.11 It comes at a time of enormous community health center growth and increased utilization of preventive services as a result of the ACA’s Medicaid and insurance expansions. It also comes at a time of significant pressure to withdraw federal support to other key providers of publicly supported family planning services, in particular, Planned Parenthood. Using data collected in 2017, the study is designed to examine the way in which the provision of family planning services by community health centers has changed, if at all, during an important time in the evolution of the family planning safety net.

This study sought to gain greater insight into the extent to which community health centers’ family planning services have evolved as patient needs and standards of practice have changed. In particular, we were interested in how community health centers were responding to the growing emphasis and acceptance of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) and clinical practice standards that promote rapid access to other effective forms of contraception. We also sought to learn more about the barriers community health centers face in the provision of family planning services to their patients and whether, as was documented in the 2011 study, Title X continues to be associated with more robust community health center family planning programs.

As was done in 2011, researchers surveyed all federally funded community health centers operating in the 50 states and the District of Columbia based upon data drawn from the federal 2015 Uniform Data System (UDS), a national reporting system that includes community health centers. The survey was conducted between mid-May and the end of July 2017. To ensure representativeness in terms of size and location, the results were weighted by US Census region and health center size. As with the 2011 survey, respondents were asked certain questions about the availability of family planning services across all sites, but the focus of the questionnaire was the practices and policies of their largest comprehensive medical site at which family planning services are available.

The study included statistical analyses to determine what effects, if any, might be associated with the following factors: participation in the Title X family planning program; health centers’ location in an ACA Medicaid expansion or non-expansion state; health center size;12 and geographic location.13 In the case of questions asked in both 2011 and 2017, we present current survey results along with those from our earlier study. All results described in this brief are statistically significant (at p < 0.05), unless otherwise noted.

Community health centers in all 50 states and the District of Columbia responded to the survey for a total of 546 responses out of 1,345 federally funded health centers in the 2015 UDS, a 41 percent response rate. The health centers that responded to the survey are generally similar to non-responding health centers in terms of size and location; there were no significant differences between health centers that responded to the survey and non-responders for rural vs. urban location, number of patients served, or number of patient visits.14

Key Findings

Onsite Access to Contraceptive Methods

Many health centers provide highly effective contraceptive methods onsite; the provision of long-acting methods has increased since 2011, while onsite oral contraceptive provision has dropped. Consistent with federal requirements and similar to our earlier findings, virtually all health centers (97 percent) reported that their largest comprehensive medical sites offered family planning services. Providing contraception onsite facilitates access to care, reducing barriers including the time and costs required to travel to an outside pharmacy or to another clinic. As in 2011, the contraceptive method most commonly offered onsite was the contraceptive injection (Depo Provera), a short acting method that protects against unintended pregnancy for three months (Figure 1). Over half of health center sites in the survey report providing long-acting methods onsite, including hormone-releasing IUDs (Mirena, Skyla, Liletta), the copper IUD (Paragard), and the implant (Nexplanon). A significantly higher percentage of sites provide the implant and hormonal IUDs than in 2011, with the largest increase in provision of the contraceptive implant from 36 percent in 2011 to 63 percent in 2017. About half the sites provide short-acting, effective methods onsite, including oral contraceptives (OCs), the contraceptive ring, and the contraceptive patch. However, the percentage of sites offering onsite access to OCs decreased from 61 percent in 201115 to 51 percent in 2017.

About one-quarter of respondents (26 percent) reported that their largest health center site receives Title X funding. The federal Title X program funds increase the resources available to health centers to operate high quality, accessible family planning programs, and establishes important performance standards with respect to contraceptive access, adherence to certain best practices, and the use of special safeguards for certain highly vulnerable populations.

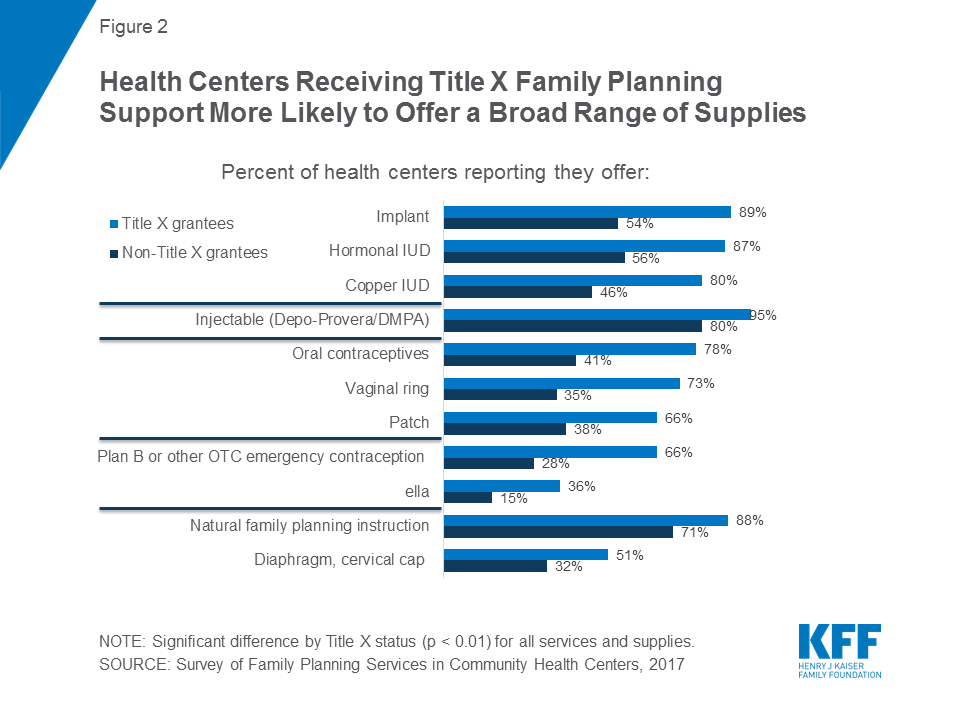

Sites with Title X funding consistently provide a larger range of contraceptive methods dispensed onsite, including emergency contraception. Particularly striking are differences related to the availability of highly effective, long-acting contraceptives. Health centers that received Title X funds were consistently more likely to offer the contraceptive implant (89 percent versus 54 percent) and hormonal (87 percent versus 56 percent) and copper (80 percent versus 46 percent) IUDs, compared with health centers that do not receive Title X funding (Figure 2). For all contraceptive methods, clinics that receive Title X funding are more likely to provide them onsite, even after controlling for location in a Medicaid expansion state, size, and urban vs. rural/suburban location (see Table A in Appendix). In particular, onsite dispensation of oral contraceptives – a low cost, and still the most widely used, method – is strikingly higher for Title X funded sites (78 percent) compared to those without Title X funding (41 percent).

Onsite provision of hormonal IUDs rose significantly among Title X sites, a 13 percentage point gain from 2011 to 2017. While onsite provision of the long-acting contraceptive implant increased significantly across both types of sites, the largest difference can be seen in Title X clinics; 89 percent of health centers with Title X funding now offer implant services onsite compared to 51 percent in 2011 (Table 1). In non-Title X sites, the percentage rose from a far lower 31 percent in 2011 to 54 percent in 2017.

While the availability of onsite oral contraceptive pills fell overall since 2011, it dropped significantly among clinics that do not receive Title X funding. Among all health centers, the onsite provision of oral contraceptive pills has dropped significantly from 61 percent in 2011 to 51 percent in 2017. There was a significant decrease among non-Title X-funded health centers, from 53 percent in 2011 to 41 percent in 2017. Title X sites also experienced a decrease, from 85 percent to 78 percent, but this decrease was not statistically significant (Table 1).

| Table 1: Differences in family planning services or supplies dispensed/provided onsite, by Title X funding status and survey year(2011 and 2017) | ||

| Non- Title X grantee site | Title X grantee site | |

| Oral contraceptives (OCs) | ||

| 2011 | 53%* | 85% |

| 2017 | 41% | 78% |

| Hormonal IUDs | ||

| 2011 | 50% | 74%* |

| 2017 | 56% | 87% |

| Copper IUD | ||

| 2011 | 45% | 73% |

| 2017 | 46% | 80% |

| Implant | ||

| 2011 | 31%* | 51%* |

| 2017 | 54% | 89% |

| Injectable | ||

| 2011 | 78% | 92% |

| 2017 | 80% | 95% |

| Patch | ||

| 2011 | 43% | 70% |

| 2017 | 38% | 66% |

| Ring | ||

| 2011 | 42%* | 68% |

| 2017 | 35% | 73% |

| Diaphragm, cervical cap | ||

| 2011 | 35% | 52% |

| 2017 | 32% | 51% |

| Natural family planning instruction | ||

| 2011 | 57%* | 86% |

| 2017 | 71% | 88% |

| Plan B | ||

| 2011 | 35%* | 83%* |

| 2017 | 28% | 66% |

| NOTE: *Indicates a statistically significant difference from 2017, p<0.05. | ||

Fewer than half of the largest health center sites provide emergency contraception onsite, and many do not prescribe or refer for it at all. Onsite provision of Plan B16 has significantly decreased since 2011. Only two in five sites provide onsite access to levonorgestrel, an over-the-counter (OTC) EC pill, the most well-known brand name of which is Plan B, down from roughly half (49 percent) of all health centers in 2011. One in five (21 percent) health centers currently provides onsite access to ulipristal acetate, the prescription EC (brand name: ella). Emergency contraception (EC) is an important component of contraceptive care, and reducing access barriers is essential in preventing unintended pregnancy. Depending on the type of EC (levonorgestrel or ulipristal acetate), a woman must take it within either 72 hours or 120 hours of unprotected sex or contraceptive failure. Quality family planning guidelines recommend that providers dispense EC onsite by providing or prescribing EC in advance for a woman to take home or to obtain without returning to the clinic.

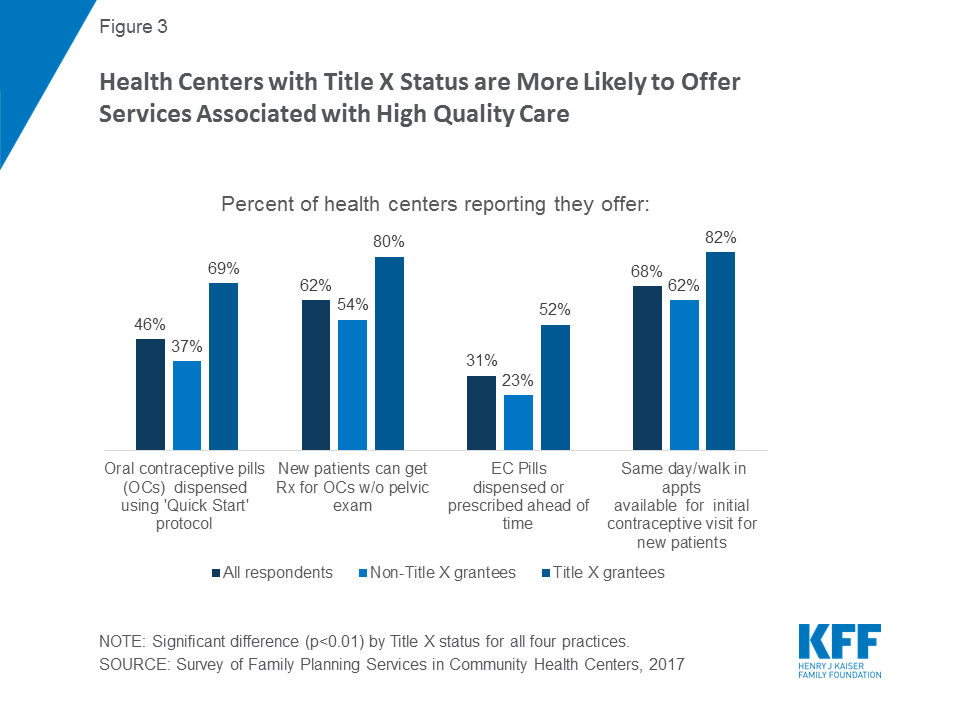

Onsite access to emergency contraception is greater at sites receiving Title X funding, although for both types of sites, access to prescribed emergency contraceptives at health centers is low. About two-thirds (66 percent) of Title X sites offered Plan B or other over the counter EC onsite, compared with less than one-third of non-Title X sites (28 percent). Onsite provision of Plan B has decreased significantly among both Title X and non-Title X sites since 2011 when 83 percent and 35 percent of health centers provided this service, respectively. Title X sites (36 percent) were also more likely to provide ella onsite than non-Title X sites (15 percent). Notably, 15 percent and 28 percent of all sites do not dispense, prescribe, or refer for plan B or ella, respectively.17 Less than one-third of the largest sites (31 percent) provide or prescribe EC ahead of time; however, Title X sites do so at twice the rate of non-title X sites (52 percent vs 23 percent, respectively) (Figure 3).18

Rural or suburban health centers are less likely to provide the full range of contraceptive methods onsite. Rural or suburban health centers are significantly less likely than urban health centers to provide hormonal and copper IUDs, the implant, the patch, and both types of emergency contraception onsite, although even at urban health centers, fewer than half (48 percent) provide onsite over the counter (Plan B) emergency contraception. (Figure 4).

Adherence to Best Practice Standards for Family Planning Services

Although a significant number of women rely on birth control pills, a considerable number of health centers have not yet adopted best practices related to the provision of OCs, such as prescribing oral contraceptives without requiring a pelvic exam, adopting the “quick start” method, and dispensing a one-year supply at a time.19 Only about three in five sites participating in the survey (62 percent) reported that they provide oral contraceptives without first requiring a pelvic exam, and less than half of health centers (46 percent) report using the “quick start” method. Current clinical guidelines recommend the “quick start” method when it comes to the initiation of oral contraceptives, which entails initiating birth control pills immediately, without regard to the timing of a woman’s menstrual cycle. Sites receiving Title X funds and sites in urban locations are more likely to allow patients to begin oral contraception without a pelvic exam. Title X sites are also more likely to use the “quick start” method (Figure 3).

In addition, under older standards of practice, clinicians typically prescribed or provided birth control pills only one month to three months at a time; today’s clinical recommendations now suggest providing at least three months or up to one year of oral contraceptives during a single visit to minimize the likelihood that patients will experience gaps, which increase the risk of unintended pregnancy.20 Only 30 percent of health centers that provide OCs onsite reported allowing patients to obtain a full year’s supply of OCs at a single visit, with no significant difference by Title X status. More rural/suburban health centers that provide OCs onsite allow patients to pick up one year of oral contraceptive pills at a time than urban health centers (38 percent versus 23 percent).

Roughly two-thirds of health center sites offer access to family planning services for new patients on a same-day and walk-in basis. Eighty-nine percent of the largest health center sites have same-day or walk-in contraceptive visits for established patients, and 68 percent maintain a walk-in policy for new patients. Clinical experts recommend providing same-day family planning services in order to reduce unnecessary barriers to obtaining family planning care. Waiting to receive contraceptive care places patients at greater risk of unintended pregnancy, and for most patients, there is no clinical need to delay initiation of access to the contraceptive of choice. Health centers with Title X status (82 percent) are more likely to offer same-day and walk-in appointments for initial contraceptive visits to new patients compared to health centers without Title X status (62 percent).

Most health centers follow current guidance on counseling approaches to pregnancy intentions, screening for intimate partner violence, and clinical screenings for sexually transmitted infections. Current clinical guidance recommends asking women annually about pregnancy intention so that clinicians can work with women to determine the contraceptive method that best fits their reproductive plans.21 Seventy-six percent of health centers reported that their largest site asks women annually about pregnancy intention. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and Quality Family Planning (QFP) Guidelines also recommend that providers routinely screen sexually active women age 25 or younger for chlamydia because, if left untreated, infection can result in infertility,22 and the majority of health centers (85 percent) currently do so. Finally, 80 percent routinely screen women of childbearing age for intimate partner violence, a practice recommended in the QFP Guidelines, the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative, and the USPSTF.23 Title X-funded sites are more likely to conduct these screening services than non-Title X health centers (Figure 5). Additionally, urban health center sites are more likely than rural/suburban sites to perform routine screenings for chlamydia among sexually active women age 25 or younger (93 percent versus 78 percent) and intimate partner violence among women of childbearing age (85 percent versus 75 percent).

Health centers rely less on physicians for patient counseling than they did in 2011. Three quarters of health centers (76 percent) use physicians to provide family planning counseling, down from 85 percent in 2011. In 2017, health centers are more likely to use advanced practice clinicians such as physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or certified nurse midwives than physicians to provide clinical exams (95 percent versus 86 percent) and pelvic exams (94 percent versus 86 percent). In light of the surging demand for health center care and physician staffing shortages, it is not surprising to see health centers relying more on other qualified clinicians and less on physicians for certain tasks. Furthermore, it may allow health centers to save money, as physicians bill at a higher rate than advanced practice clinicians.

Few health centers rely on health counselors or educators for family planning counseling, but Title X health centers are significantly more likely to use health counselors or educators than non-Title X health centers, a trend that has persisted since 2011. Family planning counselors or educators are an important part of family planning care because they provide patients with an opportunity to discuss questions or concerns about family planning separate from the traditional visit model. Only one in four sites (24 percent) usually provide counseling by health counselors or educators. However, the percentages are vastly different for Title X health centers, where 43 percent report using a health counselor or educator, and for non-Title X health centers, where 16 percent report using one. These shares remain consistent from 2011 when 44 percent of Title X and 14 percent of non-Title X sites used a health counselor or educator.

Services tailored to adolescents are a feature at six in ten health centers, as is adherence to standards designed to ensure confidentiality of care furnished to adolescents. Adolescents represent an especially vulnerable population but can be protected by measures such as maintaining confidentiality through separate contact information for communications regarding family planning services. Over 60 percent of sites offer contraceptive services tailored specifically for adolescents, collaborate with other entities on outreach activities to adolescents to meet their family planning needs, and/or maintain separate contact information for communications regarding family planning services for adolescents. A higher share of sites offer services tailored to adolescents (63 percent in 2017 compared to 47 percent in 2011), and collaborate with other entities and maintain specialized confidentiality procedures for minors than in 2011 (Table 2). About one quarter of health centers (23 percent) reported that their largest site also provides family planning services at school-based health centers (data not shown).

| Table 2: Share of Health Centers Reporting Services for Adolescents, 2011 and 2017 | ||

| 2011 | 2017 | |

| Offers contraceptive services tailored specifically for adolescents | 47%* | 63% |

| Collaborates with other entities on outreach activities to adolescents to meet their family planning needs | 52%* | 65% |

| Maintains separate contact information for communications regarding family planning services for adolescents | 48%* | 67% |

| NOTE: *Indicates a statistically significant difference from 2017, p<0.05. | ||

A very small subset of health centers offers multiple contraceptive methods and services onsite, and health centers with Title X funding are more likely to do so. One in four health centers (24 percent) provides all seven of the most effective family planning methods24 onsite, and about half (48 percent) provide all seven methods either onsite or by prescription (Figure 6). Significant differences emerge when examining these findings by Title X funding status. Among health center sites that also receive Title X funding, 48 percent offer all seven methods onsite, while 72 percent offer all seven methods either onsite or by prescription. The performance of non-Title X sites is much more limited: only 15 percent of non-Title X health centers offer all seven methods onsite, while 40 percent offer them either onsite or by prescription.

The proportion of health centers adhering to all best practices for providing contraception (the oral contraception quick start method, providing oral contraceptives without a pelvic exam, and providing emergency contraceptive ahead of time) is low (21 percent). Only 13 percent of non-Title X health centers do so, compared to 42 percent of Title X health centers. Finally, only six percent of all health centers show the highest level of performance, that is, they offer all seven effective methods onsite, follow all three contraceptive best practices, and offer same-day family planning visits for new patients. As with other performance indicators, Title X makes a big difference: two percent of non-Title X health center sites can be thought of as optimal performers compared to 17 percent of sites that also receive Title X funding.

Capacity to Absorb New Patients/ Referrals to Freestanding Family Planning Clinics

Few health centers report they can absorb a significant number of new patients given current staffing and space constraints. The recent health center expansion resulting from the ACA has occurred simultaneously with a marked decline in the number of freestanding family planning clinics.25 The majority of survey respondents (51 percent) said that – at most – they would be able to increase their new patient capacity between 10 and 24 percent (Figure 7). Only 6 percent reported that they could absorb a 50 percent or greater patient increase. These figures are consistent with findings from a study conducted in Texas following the reduction in access to publicly supported family planning services26 that shows the challenges in growing capacity at remaining providers quickly or substantially enough to overcome the loss of independent family planning clinics.

Health centers are providing substantially fewer referrals to freestanding family planning clinics than in 2011. In 2017, among health centers that reported they had a freestanding family planning clinic in their community, only 36 percent reported regularly making referrals to such a clinic. By comparison, in our 2011 study, 78 percent of health centers reported regularly making referrals among those that reported a freestanding family planning clinic in their community.

In 2017, 24 percent of all health centers reported that referral was not an option because there was no family planning clinic in their community, a similar proportion to 2011. The lack of referral options in 2017 was far more common in rural and suburban health centers (40 percent) compared to urban health centers, only 7 percent of which reported no referral clinics. Referrals are more commonly reported by sites that do not get Title X funding (43 percent versus 13 percent among those that receive Title X funding).

Referrals may be falling for several reasons. One is the growth in health centers and expanded capacity to furnish services onsite, particularly more complex procedures such as those involved in LARC methods. Another factor may be the reduction in the number of freestanding family planning clinics locally.27 Other reasons may be changes in care-seeking preferences of family planning patients (a desire to obtain all needed services in one place) and changes in overall standards of primary care practice, with a greater emphasis on the role of community health centers as comprehensive health homes.

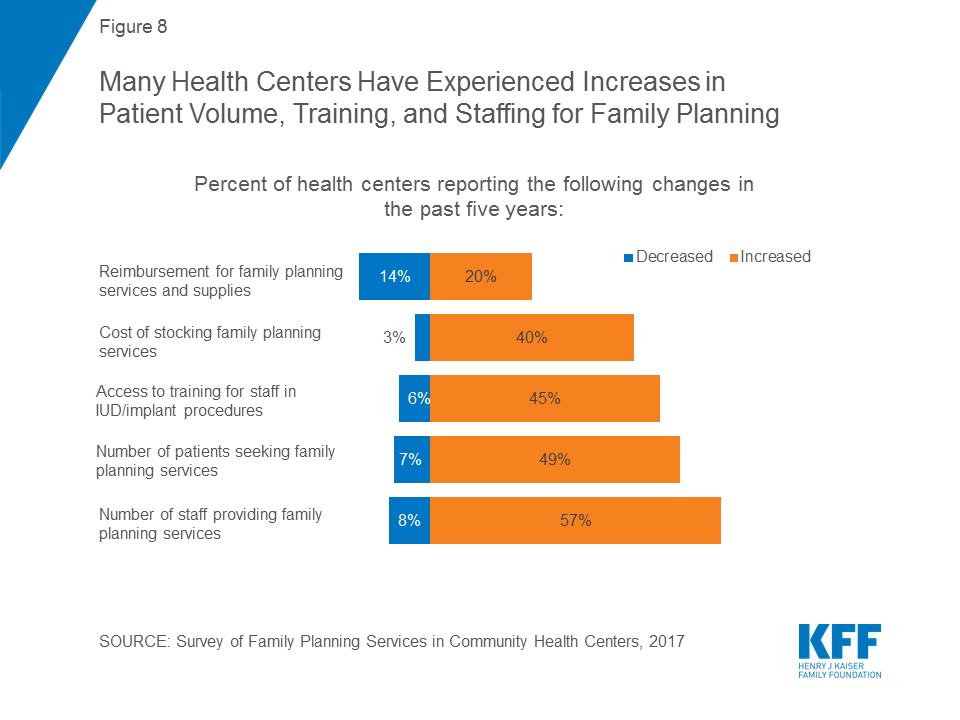

When asked to describe how their family planning services have changed in the past five years, health centers identify several factors, including reimbursement, staffing, and patient volume. Patient demand for family planning services rose for 49 percent of health centers; this was notable for both Title X grantees (64 percent) and, to a significantly lesser extent, for non-Title X sites (42 percent). In parallel, far more health centers reported family planning staffing increases (57 percent) than decreases (8 percent) (Figure 8). Access to training for staff in IUD and implant procedures rose. This was significantly different for Title X sites, where 62 percent reported an increase in access to training for staff, compared to 39 percent of sites that do not receive Title X funds. Nearly half (45 percent) of all health center sites report a decline in the number of uninsured patients, consistent with the reduction in the number of uninsured resulting from the ACA coverage expansions. A sizable minority of sites (40 percent) reported experiencing increases in the costs of stocking family planning supplies, and this was significantly higher among those that participated in Title X (51 percent) than those that did not (37 percent), likely because a higher share of Title X sites offered more costly methods like IUDs onsite.

Barriers to Providing High Quality Family Planning Care

Health centers report several major barriers to meeting patients’ family planning and reproductive health needs at their largest sites, most of which are related to the affordability of care for patients and the cost to the health center of maintaining a robust family planning practice. Twenty-five percent reported the lack of insurance coverage among patients as a major barrier, while 28 percent reported high patient cost-sharing as an issue (Table 3). In terms of their ability to maintain robust programs, one in four health centers (24 percent) reported the high cost of stocking contraceptives onsite as a major barrier. Twenty percent reported high patient demand for other primary care services at their largest site as a major barrier, which kept them from focusing additional resources on family planning. Nineteen percent reported a lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures as a major barrier, and 19 percent reported inadequate insurance payments. Lack of culturally and/or linguistically appropriate materials or services (3 percent), lack of stocking space (7 percent), lack of staff (11 percent), or religious or moral concerns among staff or board members (4 percent) were reported as barriers by a smaller share of health centers.

| Table 3 : Share of Health Centers Experiencing Major Barriers to the Provision of Family Planning Services, 2017,by Title X and ACA Medicaid Expansion | |||||

| All respondents | Title X status | ACA Medicaid Expansion Status | |||

| Non-Title X grantee sites | Title X grantee sites | Sites in non-expansion states | Sites in ACA Medicaid expansion states | ||

| High out of pocket costs for patients | 28% | 31%* | 17% | 39%* | 21% |

| Lack of insurance coverage among patients | 25% | 28%* | 17% | 41%* | 15% |

| High cost to have contraceptives in stock | 24% | 29%* | 9% | 22% | 26% |

| High patient demand for other primary care services | 20% | 23% | 15% | 22% | 20% |

| Lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures | 19% | 22%* | 9% | 21% | 18% |

| Inadequate insurance reimbursement/payments | 19% | 22%* | 12% | 28%* | 15% |

| NOTE: *Indicates a statistically significant difference between Title X and non-Title X grantee sites and between sites in non-expansion states and ACA Medicaid expansion states, p<0.05. | |||||

Title X-funded sites are significantly less likely than those that do not receive Title X funding to report certain barriers. Title X sites are less likely to report a lack of insurance coverage among patients, high out-of-pocket costs for patients, a lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures, the high cost of keeping contraceptives in stock, or inadequate insurance payments as major barriers to meeting the family planning and reproductive health needs of their patients. The latter four findings hold true even after controlling for location in a Medicaid expansion state, size, and urban vs. rural/suburban location (see Table B in Appendix). In addition, rural/suburban health centers are more likely to report a lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures (27 percent) as a major barrier, more than double the share of urban health centers that do (10 percent). Small health centers28 are also more likely to report this barrier, compared to large health centers (24 percent versus 14 percent). However, large health centers (23 percent) are more likely than small health centers (15 percent) to report that inadequate reimbursement is a major barrier to meeting the needs of their community.

Health centers in Medicaid expansion states are less likely to experience certain barriers to providing family planning care, especially barriers related to insurance and costs of care. While 41 percent of sites in non-expansion states experience the lack of insurance coverage among their patients as a major barrier, this percentage drops to 15 percent in states that have expanded Medicaid. Similarly, high out-of-pocket costs for patients are a major barrier in 39 percent of non-expansion state sites but in only 21 percent of expansion state sites. Significant differences between sites in expansion and non-expansion states persist after controlling for Title X grantee status, size, and urban vs. rural/suburban location (see Table B in Appendix).

Implications

Family planning and related services are essential to the health of women and families. For this reason, provision of high quality family planning services ought to be central to community health centers’ mission, not only because family planning is a required service but because community health centers play such a central role in women’s health. Thirty percent of all low-income women of reproductive age rely on community health centers, and women of reproductive age represent one quarter (26 percent) of all community health center patients. As community health centers have grown, and as other sources of accessible, affordable family planning services have shrunk, community health centers’ role in family planning has become increasingly important.

In thousands of communities, residents continue to rely on independent family planning clinics, which remain an essential part of the primary care landscape. Indeed, as the referral findings in this report suggest, many community health centers depend on collaboration with independent family planning clinics to help meet the sexual and reproductive health needs of their communities.

This report shows some of the ways in which community health center family planning services have strengthened. Between 2011 and 2017, the proportion of community health centers offering highly effective contraceptive implants onsite increased significantly among both Title X and non-Title X funded community health centers. However, the evidence also shows wide variation in health centers’ ability to meet women’s reproductive health care needs. These findings suggest that while some health centers have strengthened their services and performance, others fall short of the broad range of contraceptive methods and simplified access to care that are considered essential to modern, high quality family practice performance.

It is clear from this survey that Title X participation makes a significant difference in community health center performance. Some of this difference can be attributable to the fact that Title X grantees are dedicated to providing family planning services and have access to additional resources targeted to upgrading and improving family planning care. One would expect more dedicated and specially trained staff to provide a wider array of onsite services commensurate with Title X requirements. In addition, unlike Title X, Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act leaves many of the key details of clinical practice to community health centers, which in turn may contribute to highly variable care. Given their obligations to patients of all ages and their limited operational resources, community health centers must continually balance resource allocation against the full scope of community need, but the result is that some clinics fall short in meeting current standards of family planning care. As suggested by the FOA for Title X funding, the Trump Administration is changing the evidence -based requirements for Title X clinics, which will have severe implications for the provision of quality family planning at Title X clinics.

Some of the differences between community health centers that do and do not receive Title X funding are striking. Some involve relatively low practice transformation strategies to update older and outdated practices; these strategies should be well within reach regardless of the availability of additional Title X funding. For example, it is not clear why only half or fewer than half of all community health centers offer onsite access to oral contraceptives (51 percent) or emergency contraception (40 percent for plan B or other OTC EC); indeed, between 2011 and 2017, onsite oral contraceptive dispensing dropped by 17 percent, and a sizable minority of clinics do not dispense, prescribe, or refer for EC (15 percent for Plan B and 28 percent for ella). Nor is it clear why only 62 percent of community health centers report that new patients can secure a prescription for oral contraceptives without a pelvic exam and only 31 percent of community health centers will dispense or prescribe emergency contraception ahead of time. These practices are now considered the standard in the field and are elements of high quality care that require the introduction of healthcare efficiencies rather than major new resources. The value of focusing on relatively modest efficiency changes in the provision of family planning services that can improve access and quality thus emerges as an important report conclusion.

Important differences remain with respect to community health center size and rural/suburban or urban location, but measurable improvements involving highly effective family planning services have occurred in recent years. Similarly, over three-quarters of community health centers report that they routinely screen young women for chlamydia, screen for intimate partner violence, and ask about pregnancy intention. These numbers suggest the beneficial effects of evidence-based quality performance measures and the systematic introduction of best practices and the extent to which careful focus on performance can translate into greater quality.

It is particularly important to note the finding that only half of community health centers say they can handle a modest (10 to 24 percent) increase in patient capacity, and almost three in ten say they can only accommodate a slight (less than 10 percent) increase in new patients. A common theme among proposals to block Planned Parenthood from the Medicaid program is the redirection of funds to other providers, such as community health centers, with the expectation that other clinics could meet the needs of those formerly served by Planned Parenthood. However, this survey suggests that these health centers may not have the capacity to fill the void if Planned Parenthood were excluded as a Medicaid or Title X provider. In addition, this survey shows that many health centers are not providing the full range of methods to which women need access. Other studies have found that Planned Parenthood clinics are more likely to offer women the full range of contraceptive and family planning services. This survey confirms that many health centers not only do not feel equipped to absorb many new patients; many also do not offer the broad scope of services that are part of the current standard of high quality family planning care.

Finally, this study shows the value of a program such as Title X – not only as a vital source of funding for clinics that focus on reproductive health and ensuring access to comprehensive contraceptive methods but also as means for leveraging performance improvement among health centers that focus more broadly on the provision of primary care. Given the limited amount appropriated to Title X and the ongoing need for Title X funding in communities across the nation, a possible approach to improve the scope of family planning offered by all community health centers would be to dedicate a specified proportion of 330 funding to assist health centers in achieving specific family planning performance improvement. A strategy that combines supplemental funding with clear family planning improvement performance expectations is a permissible activity under the health center program itself.

Section 50901 of the Balanced Budget Act of 2018 (Pub. L. 115-123), which extends the Affordable Care Act’s health center grant fund through the end of Fiscal Year 2019, explicitly authorizes HHS to use a portion of these additional funds to make targeted improvements in primary health care quality improvement. The health centers program has successfully used this targeted supplemental grant approach for other high community needs such as maternity care, substance use addiction treatment, mental health, and oral health. Based on this study’s findings regarding the impact of dedicated Title X funding, and in view of community health centers’ central role in the health of low income women of childbearing age, a well-designed family planning initiative as central part of the health center program itself can be expected to promote the availability and quality of health center family planning services.

Appendix

| Table A: Adjusted odds ratios for prescribing or dispensing contraceptive methods onsite | ||||

| Title X grantee | Large site | Urban | Medicaid expansion state | |

| Oral contraceptives (OCs) | 5.17* | 1.52 | 1.18 | 0.75 |

| Hormonal IUDs | 4.30* | 1.67* | 1.76* | 1.05 |

| Copper IUD | 4.24* | 1.98* | 1.66* | 1.18 |

| Implant | 6.31* | 1.72* | 1.28 | 1.00 |

| Injectable | 4.84* | 1.64 | 0.68 | 1.07 |

| Patch | 3.04* | 1.50 | 1.34 | 1.06 |

| Ring | 4.47* | 1.32 | 1.15 | 0.95 |

| Diaphragm, cervical cap | 2.17* | 1.35 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| Natural family planning instruction | 2.91* | 1.42 | 1.09 | 1.26 |

| Plan B | 4.09* | 1.11 | 1.67* | 2.40* |

| ella | 2.97* | 1.13 | 1.95* | 1.75 |

| NOTE: *p<0.05. | ||||

| Table B: Adjusted odds ratios for major barriers to meeting the family planning and reproductive health needs of patients | ||||

| Title X grantee | Large site | Urban | Medicaid expansion state | |

| Lack of insurance coverage among patients | 0.60 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 0.26* |

| High out of pocket costs for patients | 0.53* | 1.05 | 0.89 | 0.46* |

| High patient demand for other primary care services | 0.72 | 1.49 | 0.56* | 1.07 |

| Lack of space to stock family planning supplies | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.27* | 0.95 |

| High cost to have contraceptives in stock | 0.28* | 1.33 | 0.69 | 1.23 |

| Lack of staff trained in IUD/implant procedures | 0.40* | 0.54* | 0.32* | 1.08 |

| Inadequate insurance reimbursement/payments | 0.50* | 2.32* | 0.89 | 0.42* |

| NOTE: *p<0.05. | ||||

Endnotes

- Ranji, U., Salganicoff, A., Sobel, L., Rosenzweig, C., & Gomez, I. (2017). Financing family planning services for low-income women: the role of public programs. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from: https://modern.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/financing-family-planning-services-for-low-income-women-the-role-of-public-programs/ ↩︎

- Gavin, L., Moskosky, S., Carter, M., Curtis, K., Glass, E., Godfrey, E., Marcell, A., Mautone-Smith, N., Pazol, K., Tepper, N. (2014). Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6304.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2017. ↩︎

- Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2017 https://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html ↩︎

- Wood, S., Goldberg, D., Beeson, T., Bruen, B., Johnson, K., Mead, H., … Rosenbaum, S. (2013). Health Centers and Family Planning: Results of a Nationwide Study. Retrieved from: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_facpubs/60. Accessed January 11, 2017. ↩︎

- Data derived from the Health Resources and Services Administration, Uniform Data System; calculations by GW ↩︎

- George Washington analysis of 2016 UDS data ↩︎

- US Census Bureau. (2017). Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/cps/data/cpstablecreator.html ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 254b(b)(1)(A) and (k)(3) (Because “look-alike” is conditioned on satisfaction of all federal health center requirements, family planning also would be a required service at look-alike health centers as well.) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 254b(b)(1)(A) and (k)(3) ↩︎

- Office of Population Affairs, Program Requirements for Title X Funded Family Planning Projects, April 2014. ↩︎

- Wood, S., Goldberg, D., Beeson, T., Bruen, B., Johnson, K., Mead, H., … Rosenbaum, S. (2013). Health Centers and Family Planning: Results of a Nationwide Study. Retrieved from: http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/sphhs_policy_facpubs/60. Accessed January 11, 2017. ↩︎

- Categories: at or above the median number of patient visits (15,000) reported at the site in calendar year 2016. ↩︎

- Categories: urban vs. rural/suburban ↩︎

- UDS does not include a category for suburban, and location is defined by health center self-report. At the site level, 60 percent were urban and 40 percent were rural, while at the grantee level, 56 percent were urban and 44 percent were rural (source: GW analysis of 2016 Uniform Data System [UDS] data). ↩︎

- Upon re-analysis of the 2011 data, some findings differed slightly (<1%) from previously published percentages due to rounding. ↩︎

- ella was not included on the 2011 survey. ↩︎

- ella was not included on the 2011 survey. ↩︎

- Committee Opinion Number 707: Access to Emergency Contraception. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. July 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co707.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20170707T0723545024 ↩︎

- Committee Opinion Number 615: Access to Contraception. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. January 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Access-to-Contraception ↩︎

- Gavin, L., Moskosky, S., Carter, M., Curtis, K., Glass, E., Godfrey, E., Marcell, A., Mautone-Smith, N., Pazol, K., Tepper, N. (2014). Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6304.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2017. ↩︎

- Gavin, L., Moskosky, S., Carter, M., Curtis, K., Glass, E., Godfrey, E., Marcell, A., Mautone-Smith, N., Pazol, K., Tepper, N. (2014). Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6304.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2017. ↩︎

- Gavin, L., Moskosky, S., Carter, M., Curtis, K., Glass, E., Godfrey, E., Marcell, A., Mautone-Smith, N., Pazol, K., Tepper, N. (2014). Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6304.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2017. ↩︎

- Gavin, L., Moskosky, S., Carter, M., Curtis, K., Glass, E., Godfrey, E., Marcell, A., Mautone-Smith, N., Pazol, K., Tepper, N. (2014). Providing Quality Family Planning Services Recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6304.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2017. ↩︎

- The seven effective methods include: hormonal IUDs, copper IUDs, the implant, the injectable, oral contraceptives, the contraceptive ring, and the contraceptive patch. ↩︎

- Frost, J.J., Frohwirth, L.F., Blades, N, Zolna, M.R., Douglas-Halland, A., Bearak, J. (2017). Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services At U.S. Clinics, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-funded-contraceptive-services-us-clinics-2015 ↩︎

- Ku, L., Cartwright-Smith, L., Sharac, J., Steinmetz, E., Lewis, J., & Shin, P. (2012). Deteriorating access to women’s health services in Texas: potential effects of the Women’s Health Program affiliate rule. Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative, George Washington University. Policy Research Brief No. 31. Retrieved from: http://www.rchnfoundation.org/?p=913 ↩︎

- Frost, J.J., Frohwirth, L.F., Blades, N, Zolna, M.R., Douglas-Halland, A., Bearak, J. (2017). Publicly Funded Contraceptive Services At U.S. Clinics, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/publicly-funded-contraceptive-services-us-clinics-2015 ↩︎

- Large health centers are defined as at or above median 15,000 visits in CY2016. Small health centers are below median 15,000 visits in CY2016. ↩︎