Donor Government Assistance for Family Planning in 2015

Executive Summary

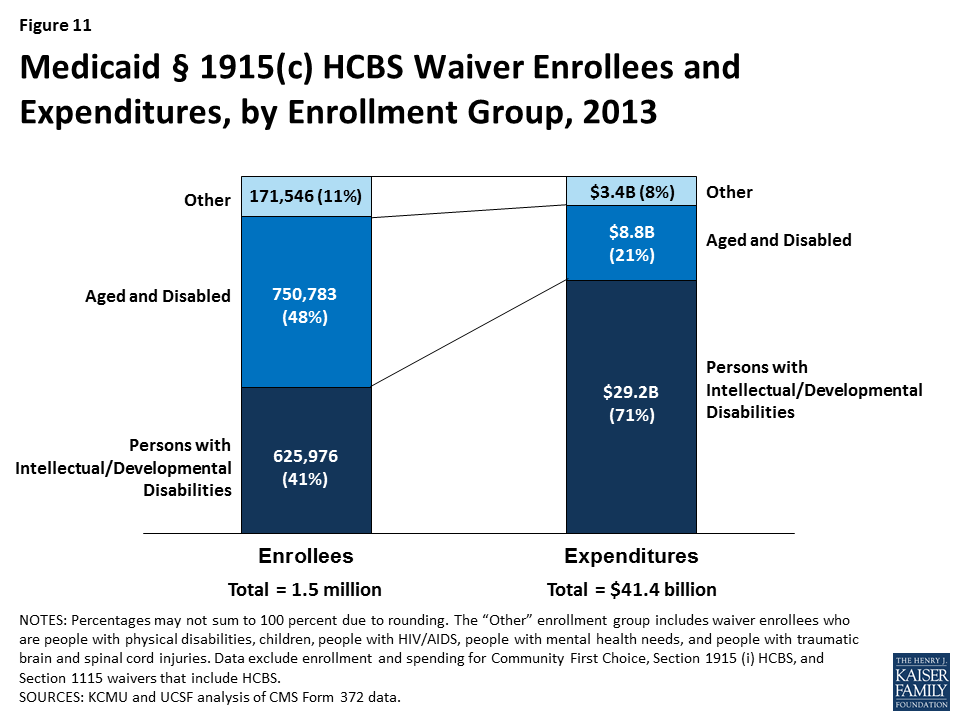

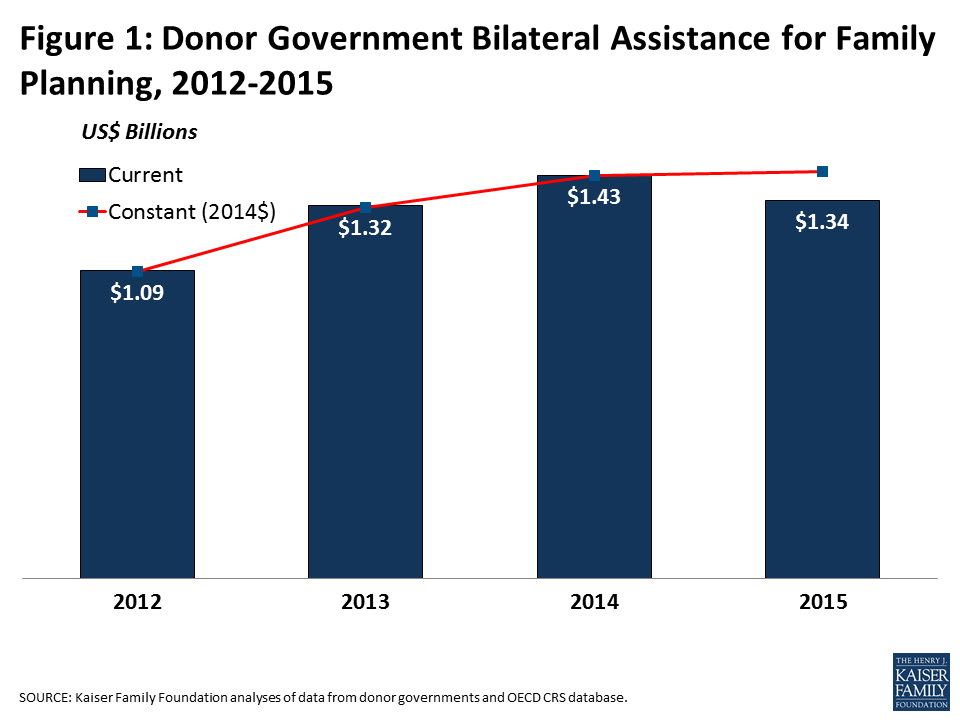

2015 marks the fourth year that the Kaiser Family Foundation has been analyzing donor government funding for family planning, tracking progress against commitments made at the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning.1 After steady increases since the Summit, funding for bilateral family planning activities remained essentially flat in 2015 in real terms (after adjusting for the effects of exchange rate fluctuations and inflation). However, in current U.S. dollars, 2015 funding (US$1.3 billion) was 6% below the 2014 level. The decrease in current U.S. dollars was largely due to a complex set of factors, primarily the appreciation of the U.S. dollar, but also to real declines by several donors. In addition to bilateral funding, donor governments also contributed US$392.6 million in core contributions to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2015, a decrease of US$78.9 million (-17%) below 2014 levels, similarly due to the appreciation of the U.S. dollar. Among the donor governments profiled, eight made specific commitments as part of the London Summit, seven of which are on track to meet these commitments.

Key findings include:

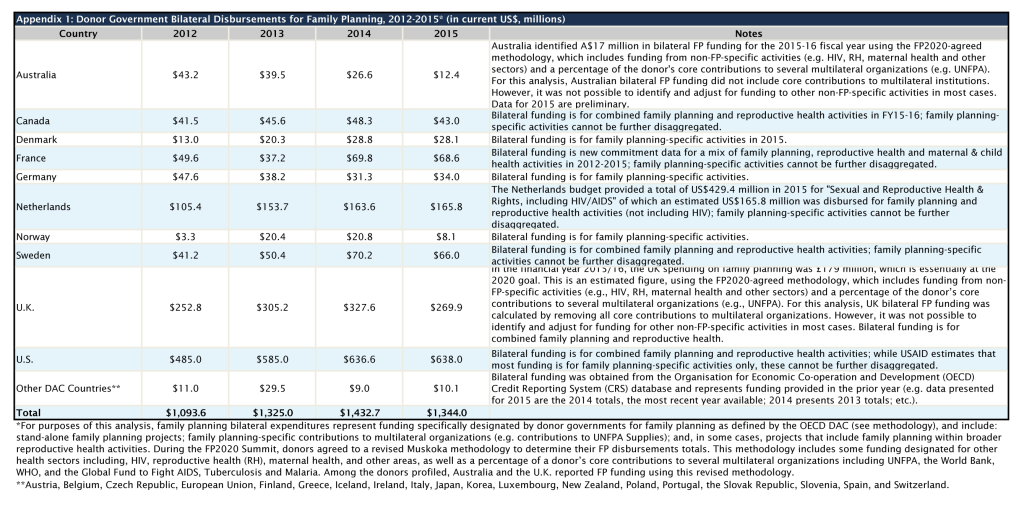

- In 2015, donor governments provided US$1.3 billion for bilateral family planning programs, essentially matching the 2014 level (US$1.4 billion) when measured in real terms (after adjusting for the effects of exchange rate fluctuations and inflation). In current dollars, 2015 funding was 6% below (-US$88.6 million) 2014, and essentially a return to 2013 levels, though still above the 2012 baseline (see Table 1 and Appendix 1).

- The decline, when measured in current U.S. dollars, is due to a complex set of factors, primarily the significant appreciation of the U.S. dollar, resulting in the depreciation of most other donor currencies, but also to real declines by several donors. In their currency of origin, five donors (Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden) increased, while funding from three donors (Australia, Norway, and the U.K.) declined. Funding from the U.S. and Canada remained flat. Despite the real declines by several donors, when the effects of the exchange rate fluctuations are removed, 2015 funding essentially matches 2014 levels.

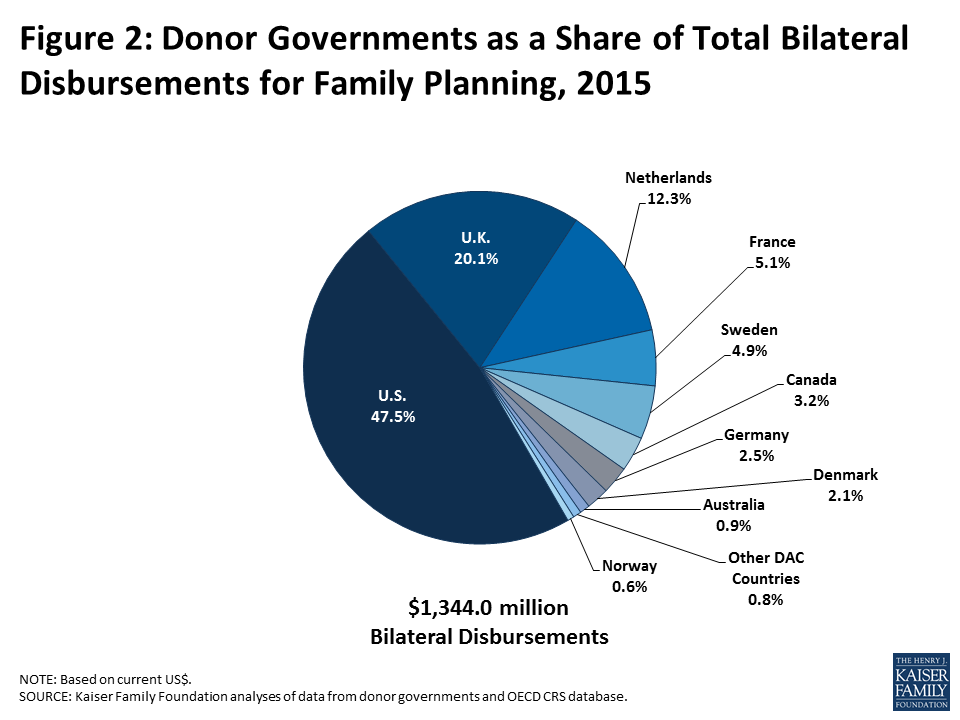

- The U.S. was the largest bilateral donor to family planning in 2015, providing US$638.0 million or almost half (47%) of total bilateral funding. The U.K. (US$269.9 million, 20%) was the second largest donor, followed by the Netherlands (US$165.8 million, 12%), France (US$68.6 million, 5%), and Sweden (US$66.0 million, 5%). Funding trends for family planning have been primarily driven by the two largest donors, the U.S. and U.K., which have accounted for approximately two-thirds of total funding between 2012 and 2015.

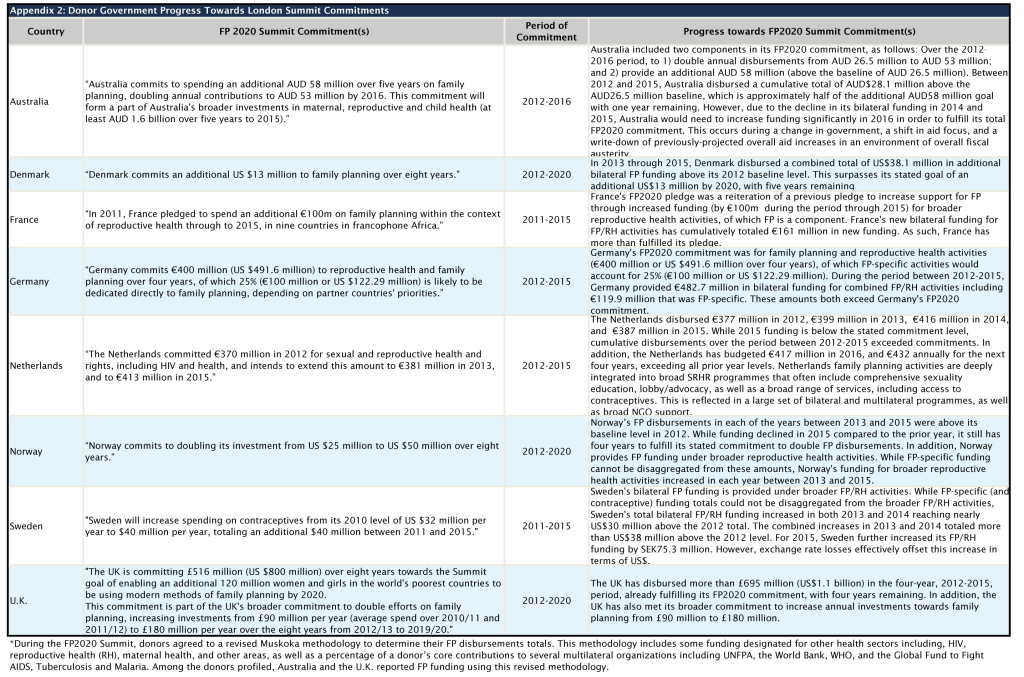

- Among the 10 donors profiled, 8 made commitments during the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning: Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the U.K., of which all but one are on track towards fulfilling these commitments. Australia had made progress in prior years, but due to recent declines would need to significantly increase funding in order to fulfill its commitment (see Appendix 2).

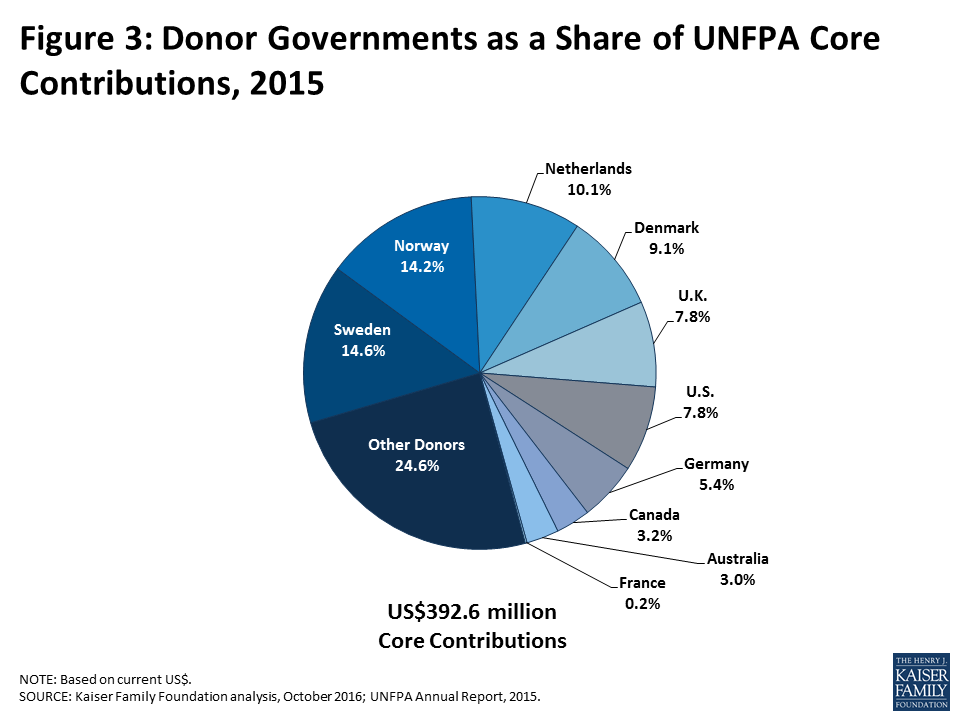

- In addition to donor contributions to UNFPA that are earmarked for family planning, and are therefore counted as bilateral funding above, the donors examined also provided US$392.6 million in core contributions to UNFPA. This too was a decline – US$78.9 million below the 2014 level (US$471.5 million). Similar to bilateral funding, much of this decline can be attributed to the appreciation of the U.S. dollar. In fact, when measured in the currency of origin, all of the donors profiled essentially maintained their contribution to UNFPA’s core resources at the prior year level, with the exception of Denmark, which increased funding. Among the donor governments profiled, Sweden provided the largest core contribution to UNFPA in 2015 (US$57.4 million), followed by Norway (US$55.6 million), the Netherlands (US$39.7 million), and Denmark (US$35.7).2

| Table 1: Donor Government Bilateral Disbursements for Family Planning, 2012-2015 (in current US$, millions) | ||||||

| Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Difference | |

| 2014 – 2015 | 2012 – 2015 | |||||

| Australia | $43.2 | $39.5 | $26.6 | $12.4 | $-14.2(-53.4%) | $-30.8(-71.3%) |

| Canada | $41.5 | $45.6 | $48.3 | $43.0 | $-5.3(-11%) | $1.5(3.6%) |

| Denmark | $13.0 | $20.3 | $28.8 | $28.1 | $-0.7(-2.4%) | $15.1(116.2%) |

| France | $49.6 | $37.2 | $69.8 | $68.6 | $-1.2(-1.7%) | $19(38.3%) |

| Germany | $47.6 | $38.2 | $31.3 | $34.0 | $2.7(8.6%) | $-13.6(-28.6%) |

| Netherlands | $105.4 | $153.7 | $163.6 | $165.8 | $2.2(1.3%) | $60.4(57.3%) |

| Norway | $3.3 | $20.4 | $20.8 | $8.1 | $-12.7(-61.1%) | $4.8(145.5%) |

| Sweden | $41.2 | $50.4 | $70.2 | $66.0 | $-4.2(-6%) | $24.8(60.2%) |

| U.K. | $252.8 | $305.2 | $327.6 | $269.9 | $-57.7(-17.6%) | $17.1(6.8%) |

| U.S. | $485.0 | $585.0 | $636.6 | $638.0 | $1.4(0.2%) | $153(31.5%) |

| Other DAC Countries* | $11.0 | $29.5 | $9.0 | $10.1 | $1.1(12.4%) | $-0.9(-7.7%) |

| Total | $1,093.6 | $1,325.0 | $1,432.7 | $1,344.0 | $-88.6 (-6.2%) | $250.4 (22.9%) |

| *Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, European Union, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland. | ||||||

Report

Introduction

At the London Summit on Family Planning (FP2020), the global community made commitments totaling US$2.6 billion in additional funding for family planning by 2020 (see Box 1). With the commitment period of several donors coming to an end in 2015 and with 2016 marking the halfway point towards fulfillment of the FP2020 goals, it is important to assess the progress made as well as plans moving forward. The status of global funding for family planning takes on added relevance as donors navigate additional budgetary and other pressures, including the ongoing refugee crisis and other competing demands, as well as the effects of Brexit.

Box 1: London Summit on Family Planning

In July 2012, the U.K. Government and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in partnership with UNFPA, civil society organizations, developing countries, donor governments, the private sector, and multilateral organizations met at the London Summit on Family Planning (FP2020) and made commitments aimed at improving access to voluntary family planning services.

London Summit on Family Planning Goals & Outcomes: “By 2020, the goal is to deliver contraceptives, information, and services to a total of 380 million women and girls in developing countries so they can plan their families.”

- Sustain coverage for the estimated 260 million women in the world’s poorest countries who are currently using contraceptives (as of June 2012); and

- Provide family planning for an additional 120 million women in these countries.

- The Summit resulted in stated commitments totaling US$2.6 billion in additional funding for family planning activities from all sources (donor governments, non-governmental organizations, philanthropies, multilateral organizations, and domestic resources).

While funding from all sources – domestic public and private spending, donor government bilateral assistance, multilateral organizations, and private philanthropy (see Box 2) – is needed to help fulfill international family planning goals and commitments, donor governments provide a significant share of the total.3 Following the London Summit, the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted an analysis of donor government funding for family planning activities in 2012 to establish a FP funding baseline that could be used to track funding levels over time as well as specific donor government progress in meeting the Summit’s commitments.

Box 2: Other Sources of Funding for FP in Low- & Middle-Income Countries

In addition to donor governments, there are three other major funding sources for family planning assistance: multilateral organizations, the private sector, and domestic resources.

Multilateral Organizations: Multilateral organizations are international organizations made up of member governments (and in some cases private sector and civil society representatives), who provide both core contribution support and donor-directed funding for specific projects. Core support from donors is pooled by the multilateral organization which in turn directs its use, such as for family planning. Donor-directed or earmarked funding, even when provided through a multilateral organization, is considered part of a donor’s bilateral assistance.

The primary multilateral organization focused on family planning is the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), which estimates that it spent US$341 million (US$92 million from core resources and US$249 million from non-core resources), or 42.7% of its total resources, on family planning activities in 2015.4 Another important source of multilateral assistance for family planning is the World Bank which provides such funding under broader population and reproductive health activities. In 2014, the World Bank estimates that it spent US$251 million on population and reproductive health, an increase of US$30 million above the 2013 level (US$221 million).5 With the creation of the Global Financing Facility (GFF), the World Bank is expected to play an increasingly important role in supporting family planning activities.

Private Sector: Foundations (charitable and corporate philanthropic organizations), corporations, faith-based organizations, and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provide support for FP activities in low- and middle-income countries not only in terms of funding, but through in-kind support; commodity donations; and co-investment strategies with government and other sectors. For instance, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has become a major funder of global health efforts, including family planning activities, and is a core partner of FP2020. In 2015, the Gates Foundation provided US$148 million for family planning.6

Domestic Resources: Domestic resources include spending by country governments that also receive international assistance for FP and spending by households/individuals within these countries for FP services. Such resources represent a significant and critical part of the response. Since the London Summit, a total of 36 low- and middle-income countries have made specific commitments to increase their family planning spending.

This report provides an analysis of donor government bilateral funding for family planning activities in 2015 compared to prior year levels. It includes data from the 29 governments who were members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Development Assistance Committee (DAC) in 2015.7 Data were collected directly from ten donors, who represent approximately 99% of bilateral family planning funding, and are profiled in this report: Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S. Data for the remaining DAC members was obtained from the OECD Credit Reporting System (CRS). For purposes of this analysis, family planning services were defined to include the following activities as specified in the CRS: “counseling; information, education and communication (IEC) activities; delivery of contraceptives; capacity building and training.”8 Bilateral totals include actual funding amounts provided (e.g., cash transfers) as well as other types of transactions and activities (e.g., technical assistance), products (e.g., commodities), and donor government earmarked contributions to multilateral organizations (e.g. contributions to the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security at UNFPA).

Where bilateral family planning funding was included as part of broader reproductive and maternal health activities or other non-health-sector activities, we worked directly with donor governments to identify family planning specific amounts to the extent possible (see Methodology for more information). Where it was not possible to disaggregate FP funding from broader reproductive and maternal health activities, the estimated level of family planning funding may be an overestimate. At the same time, some family planning funding provided under non-health-sectors remains largely unidentified, likely resulting in an underestimate of total family planning funding.

Findings

Bilateral Assistance

In 2015, donor governments disbursed9 US$1,344.0 million in bilateral funding for family planning activities (see Table 1, Figure 1 & Appendix 1), essentially flat compared to 2014 when measured in real terms (adjusting for the effects of exchange rate fluctuations and inflation). However, when measured in current U.S. dollars, 2015 was a decrease of US$88.6 million (-6%) below 2014 levels (US$1,432.7 million) and essentially a return to 2013 levels (US$1,325.0 million). The decline, when measured in current U.S. dollars, is due to a complex set of factors, primarily the significant appreciation of the U.S. dollar in 2015, which resulted in the depreciation of most other donor currencies, but also to real declines (in currency of origin) by several donors. Among the donors profiled, five (Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden) actually increased FP funding in 2015 – when measured in their currencies of origin, while funding from three donors (Australia, Norway, and the U.K.) declined. Funding from two donors (Canada and the U.S.) remained flat. Despite the decline in 2015 compared to 2014, donor government bilateral assistance for family planning is still approximately US$250 million above the 2012 baseline (US$1,093.6 million).

The United States (US$638.0 million) was the largest bilateral donor in 2015 accounting for almost half (47%) of total bilateral assistance (see Figure 2). The U.K. (US$269.9 million, 20%) was the second largest bilateral donor, followed by the Netherlands (US$165.8 million, 12%), France (US$68.6 million, 5%), and Sweden (US$66.0 million, 5%).

While the majority of donor governments increased family planning funding between 2012 and 2015, recent trends have been largely driven by the two largest donors, the U.S. and U.K., which have accounted for approximately two-thirds of total funding over the period.

Progress Towards FP2020 Commitments

Eight of the donor governments profiled in this analysis made multi-year commitments at the FP2020 Summit in 2012: Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the U.K. (see Appendix 2). Data collected for 2012-2015 indicate that seven of the eight donors have either fulfilled or are on track to fulfill their FP2020 commitment including: Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the U.K. Australia, whose commitment period ends in 2016, had made progress, but due to recent declines, would need to significantly increase family planning funding in 2016 in order to fulfill its commitment.

Donor Contributions to UNFPA

While the majority of donor government assistance for family planning is provided bilaterally, donors also provide support for family planning activities through contributions to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (see Box 3).10 Most of UNFPA’s funding is from donor governments, which provide funding in two ways: 1) donor directed or earmarked contributions for specific activities (e.g. donor contributions to the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security at UNFPA), which are included as part of bilateral funding; and 2) general contributions to “core” activities that are untied and meant to be used for both programmatic activities (family planning, population and development, HIV-AIDS, gender, and sexual and reproductive health and rights) and operational support as determined by UNFPA.

Box 3: United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Mission, Goals, & London Summit on Family Planning Commitment

Created in 1969, UNFPA supports sexual and reproductive health activities in many low- and middle-income countries and was a key partner in the London Summit on Family Planning.

UNFPA Goal: “The goal of UNFPA is to deliver a world a world where every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe and every young person’s potential is fulfilled. To accomplish this, UNFPA works to ensure that all people, especially women and young people, are able to access high quality sexual and reproductive health services, including family planning, so that they can make informed and voluntary choices about their sexual and reproductive lives.”11

UNFPA Mandate:

- “Build the knowledge and the capacity to respond to needs in population and family planning;

- Promote awareness in both developed and developing countries of population problems and possible strategies to deal with these problems;

- Assist their population problems in the forms and means best suited to the individual countries’ needs; and

- Assume a leading role in the United Nations system in promoting population programmes, and to coordinate projects supported by the Fund.”12

UNFPA London Summit on Family Planning Commitment: “UNFPA will double the proportion of its resources focused on family planning from 25% to 40 % based on current funding levels, bringing new funding of at least US$174 million per year from core and noncore funds. This will include a minimum of US $54 million per year, from 2013-2019, in increased funding for family planning from UNFPA’s core resources.”

In 2015, donor governments provided US$392.6 million in core contributions to UNFPA, a decrease of US$78.9 million (-17%) below 2014 levels (US$471.5 million). Similar to bilateral funding, much of this decline can be attributed to the appreciation of the U.S. dollar. In fact, when measured in the currency of origin, all of the donors profiled essentially maintained their contribution to UNFPA’s core resources at the prior year level, with the exception of Denmark, which increased funding. Sweden provided the largest core contribution to UNFPA in 2015 (US$57.4 million), followed by Norway (US$55.6 million), the Netherlands (US$39.7 million), and Denmark (US$35.7) (see Figure 3 and Table 2).13 Among the ten donors profiled, two provided a larger contribution to UNFPA’s core resources than their total bilateral disbursement for family planning: Denmark and Norway.

| Table 2: Donor Government Contributions to UNFPA (Core Resources), 2012-2015 (in current US$, millions) | ||||||

| Country | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Difference | |

| 2014 – 2015 | 2012 – 2015 | |||||

| Australia | $14.9 | $15.6 | $13.9 | $11.7 | $-2.2(-15.8%) | $-3.2(-21.5%) |

| Canada | $17.4 | $16.0 | $14.0 | $12.4 | $-1.6(-11.5%) | $-5(-28.7%) |

| Denmark | $44.0 | $40.4 | $41.9 | $35.7 | $-6.2(-14.8%) | $-8.3(-18.9%) |

| France | $0.5 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.6 | – | $0.1(20%) |

| Germany | $20.7 | $24.0 | $24.7 | $21.3 | $-3.4(-13.8%) | $0.6(2.9%) |

| Netherlands | $49.0 | $52.4 | $48.4 | $39.7 | $-8.7(-18%) | $-9.3(-19%) |

| Norway | $59.4 | $70.6 | $69.1 | $55.6 | $-13.5(-19.5%) | $-3.8(-6.4%) |

| Sweden | $66.3 | $65.8 | $70.3 | $57.4 | $-12.9(-18.3%) | $-8.9(-13.4%) |

| U.K. | $31.8 | $31.5 | $33.1 | $30.8 | $-2.3(-6.8%) | $-1(-3.1%) |

| U.S. | $30.2 | $28.9 | $31.1 | $30.8 | $-0.3(-1%) | $0.6(2%) |

| Other Donors | $98.0 | $108.8 | $125.0 | $96.6 | $-28.4(-22.7%) | $-1.4(-1.4%) |

| Total | $432.2 | $454.0 | $471.5 | $392.6 | $-78.9 (-16.7%) | $-39.6 (-9.2%) |

Conclusion

After several years of funding increases since the 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, donor government funding for family planning was essentially flat in 2015 in real terms, and fell when measured in current U.S. dollars. While the decline was primarily driven by the appreciation of the U.S. dollar, some donors did reduce funding, as measured in their currencies of origin. At the same time, seven of the eight profiled who made commitments at the London Summit, have either fulfilled or are on track towards fulfilling their commitments. Still, as donor commitment periods come to an end and given the uncertainty associated with the value of the U.S. dollar, it is unclear what the scope of support for family planning will be going forward.

Methodology

Methodology

Bilateral and multilateral data on donor government assistance for family planning (FP) in low- and middle-income countries were collected from multiple sources. The research team collected the latest bilateral assistance data directly for 10 governments: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States during the first half of 2016. Data represent the fiscal year 2015 period for all governments. Direct data collection from these donors was desirable because they represent the preponderance of donor government assistance for family planning and the latest official statistics – from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) (see: http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/data) – which are from 2014 and do not include all forms of international assistance (e.g., funding to countries such as Russia and the Baltic States that are no longer included in the CRS database). In addition, the CRS data may not include certain funding streams provided by donors, such as FP components of mixed-purpose grants to non-governmental organizations. Data for all other OECD DAC member governments – Austria, Belgium, the European Commission, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland – who collectively accounted for less than 2 percent of bilateral family planning disbursements, were obtained from the OECD CRS and are from calendar year 2014.

For purposes of this analysis, funding was counted as family planning if it met the OECD CRS purpose code definition: “Family planning services including counselling; information, education and communication (IEC) activities; delivery of contraceptives; capacity building and training.” Where it was possible to identify funding amounts, family-planning-related activities funded in the context of other official development assistance sectors (e.g. education, civil society) are included in this analysis. Project-level data were reviewed for Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden to determine whether all or a portion of the funding could be counted as family planning. Family-planning-specific funding totals for the United States were obtained through direct data downloads and communications with government representatives. Funding attributed to Australia and the United Kingdom is based on a revised Muskoka methodology as agreed upon by donors at the London Summit on Family Planning in 2012. Funding totals presented in this analysis should be considered preliminary estimates based on data provided by representatives of the donor governments who were contacted directly.

It was difficult in some cases to disaggregate bilateral family planning funding from broader reproductive and maternal health totals, as the two are sometimes represented as integrated totals. In addition, family-planning-related activities funded in the context of other official development assistance sectors (e.g. education, civil society) have in the past remained largely unidentified. For purposes of this analysis, we worked closely with the largest donors to family planning to identify such family-planning-specific funding where possible. In some cases (e.g. Canada), specific FP percentages were recorded for mixed-purpose projects. In other cases, it was possible to identify FP-specific activities by project titles in languages of origin, notwithstanding less-specific financial coding. In still other cases, detailed project descriptions were analyzed. (see Appendix 1 for detailed data table).

Bilateral funding is defined as any earmarked (FP-designated) amount and includes family planning-specific contributions to multilateral organizations (e.g. non-core contributions to the Global Programme to Enhance Reproductive Health Commodity Security at UNFPA). U.S. bilateral data correspond to amounts disbursed for the 2015 fiscal year. UNFPA contributions from all governments correspond to amounts received during the 2014 calendar year, regardless of which contributor’s fiscal year such disbursements pertain to.

With some exceptions, bilateral assistance data were collected for disbursements. A disbursement is the actual release of funds to, or the purchase of goods or services for, a recipient. Disbursements in any given year may include disbursements of funds committed in prior years and in some cases, not all funds committed during a government fiscal year are disbursed in that year. In addition, a disbursement by a government does not necessarily mean that the funds were provided to a country or other intended end-user. Enacted amounts represent budgetary decisions that funding will be provided, regardless of the time at which actual outlays, or disbursements, occur. In recent years, most governments have converted to cash accounting frameworks, and present budgets for legislative approval accordingly; in such cases, disbursements were used as a proxy for enacted amounts.

UNFPA core contributions were obtained from United Nations Executive Board documents. UNFPA estimates of total family planning funding provided from both core and non-core resources were obtained through direct communications with UNFPA representatives. Other than core contributions provided by governments to UNFPA, un-earmarked core contributions to United Nations entities, most of which are membership contributions set by treaty or other formal agreement (e.g., United Nations country membership assessments), are not identified as part of a donor government’s FP assistance even if the multilateral organization in turn directs some of these funds to FP. Rather, these would be considered as FP funding provided by the multilateral organization, and are not considered for purposes of this report.

The fiscal year period varies by country. The U.S. fiscal year runs from October 1-September 30. The Australian fiscal year runs from July 1-June 30. The fiscal years for Canada and the U.K. are April 1-March 31. Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden use the calendar year. The OECD uses the calendar year, so data collected from the CRS for other donor governments reflect January 1-December 31. Most UN agencies use the calendar year and their budgets are biennial.

All data are expressed in US dollars (USD). Where data were provided by governments in their currencies, they were adjusted by average daily exchange rates to obtain a USD equivalent, based on foreign exchange rate historical data available from the U.S. Federal Reserve (see: http://www.federalreserve.gov/) or in some cases from the OECD. Data obtained from UNFPA were already adjusted by UNFPA to represent a USD equivalent based on date of receipts.

Appendices

Endnotes

- The Kaiser Family Foundation initiated a family planning resource tracking project in 2013, adapting the methodology it has long used to track donor government spending on HIV. Since 2002, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the Kaiser Family Foundation have been tracking donor government assistance for HIV in low- and middle-income countries by the donor government members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC). For the methodological approach used to monitor donor government spending on HIV see: https://modern.kff.org/global-health-policy/report/financing-the-response-to-aids-in-low/. ↩︎

- In 2014, Finland provided the third largest core contribution (US$60.4 million) to UNFPA, followed by the Netherlands. ↩︎

- UNFPA, Financial Resource Flows for Population Activities Report 2011, 2013. ↩︎

- UNFPA, Direct communication, September, 2016. UNFPA methodological note: “When accounting for Family Planning expenses, it is crucial to take into account the cross-cutting nature of this area of work. Family Planning is strictly inter-linked with other areas in which UNFPA operates such as integrated services on sexual and reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, gender equality and reproductive rights, adolescents and youth, data and analysis. For example, family planning is an integral part of the activities to provide or support integrated SRH services, such as post-partum family planning, post-abortion family planning, family planning services for HIV positive individuals, etc. UNFPA’s focus on adolescents and youth includes access to contraceptives information and services for adolescents through advocacy, comprehensive sexuality education or youth-friendly services. When UNFPA supports countries in advocating for gender equality and promoting reproductive rights, especially for marginalized women and girls, family planning services are the top priority on the agenda. Family planning is closely linked with population policies and strategies, and UNFPA assists governments to link family planning with population dynamics, while developing national strategies and build reliable population data and analysis. In light of these inter-linkages, the family planning expense hereby reported also takes into account the family planning component of expense that, while predominantly conducted under some other areas of UNFPA mandate, still contribute to the achievement of family-planning related results.” ↩︎

- World Bank, Direct communication, August, 2014. ↩︎

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Direct communication, September, 2016. ↩︎

- Includes funding from 28 DAC member countries and the European Commission (EC). ↩︎

- OECD, The List of CRS Purpose Codes, 2013. ↩︎

- A disbursement is the actual release of funds to, or the purchase of goods or services for, a recipient. An enactment represents a budgetary decision that funding will be provided, regardless of the time at which an actual outlays, or disbursement, occurs. Therefore, disbursements in any given year may include funds committed (enacted) in prior years and in some cases, not all funds committed (enacted) during a government fiscal year are disbursed in that year. While most donor governments examined disburse enacted amounts within the same year, the U.S. government does not and may disburse enactments over multiple years. For instance, in FY 2013, U.S. bilateral enacted funding for family planning activities totaled $615.1 million, while disbursements totaled $585 million. ↩︎

- UNFPA, “Frequently Asked Questions” (http://www.unfpa.org/frequently-asked-questions), accessed October, 2016. ↩︎

- UNFPA, “Frequently Asked Questions” (http://www.unfpa.org/frequently-asked-questions), accessed October, 2016. ↩︎

- UNFPA, “Frequently Asked Questions” (http://www.unfpa.org/frequently-asked-questions), accessed October, 2016. ↩︎

- In 2015, Finland, which was not directly profiled in this analysis, provided the fifth largest core contribution ($38.0 million) to UNFPA, followed by the U.S. ↩︎