The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment

Issue Brief

KEY FINDINGS

In 2017, nearly two million nonelderly adults in the United States had an opioid use disorder (OUD), and of these adults, nearly four in ten were covered by Medicaid. This brief examines Medicaid’s role in facilitating access to treatment for OUD. Key findings include:

- Among nonelderly adults with OUD, those with Medicaid were more likely than those with other coverage to have received treatment in 2017.

- Medicaid facilitates access to treatment by covering inpatient and outpatient treatment services, as well as medications and therapy prescribed as part of Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT).

- States use Medicaid Section 1115 waivers and other program authorities to expand treatment options for enrollees with OUD.

- While additional states expanding Medicaid could increase coverage and access, for new work and premium requirements could impose barriers to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage.

Introduction

As the opioid epidemic continues to devastate many parts of the country, Medicaid plays an important role in efforts to address the crisis. In 2017, nearly two million nonelderly adults had opioid use disorder (OUD)1 ,2 and there were 47,600 opioid overdose deaths in the United States, more than double the number in 2007. Medicaid has historically filled critical gaps in responding to public health crises, such as the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and the Flint water crisis. As with these other public health crises, Medicaid provides health coverage and access to necessary health care for those struggling with OUD. Additionally, as of May 2019, 36 states and Washington, D.C. have adopted Medicaid expansion, with enhanced federal funding, to cover adults with income up to 138% of the federal poverty level ($17,236 for an individual in 2019). All Medicaid expansion benefit packages must include behavioral health services, including mental health and substance use disorder services.

Based on data from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, this brief describes nonelderly adults with OUD, including their demographic characteristics and insurance status, and compares utilization of treatment services among those with Medicaid to those with other types of coverage. It also describes Medicaid financing for opioid treatment and the ways in which Medicaid promotes access to treatment for enrollees with OUD.

Characteristics of Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Use Disorder

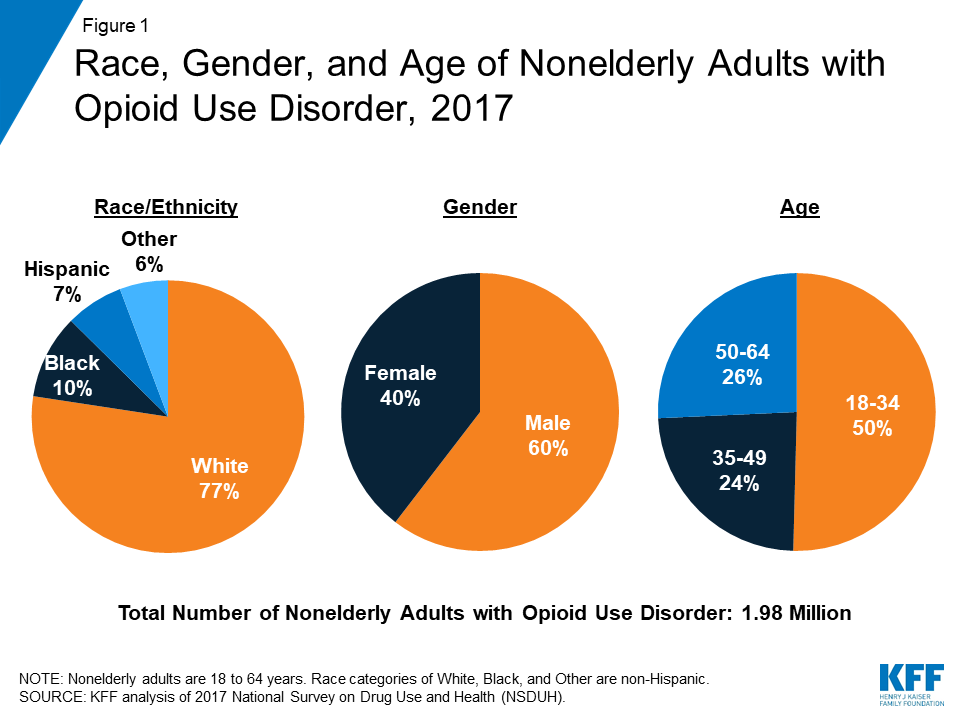

Individuals with OUD were predominantly white, male, and young adults. In 2017, more than three in four (77%) of the nearly two million nonelderly adults with OUD were non-Hispanic, White (Figure 1). Those with OUD were also more likely to be male (60%), although the epidemic has reached an increasingly large share of women in recent years, including many pregnant women.3 Additionally, half were between the ages of 18 and 34.

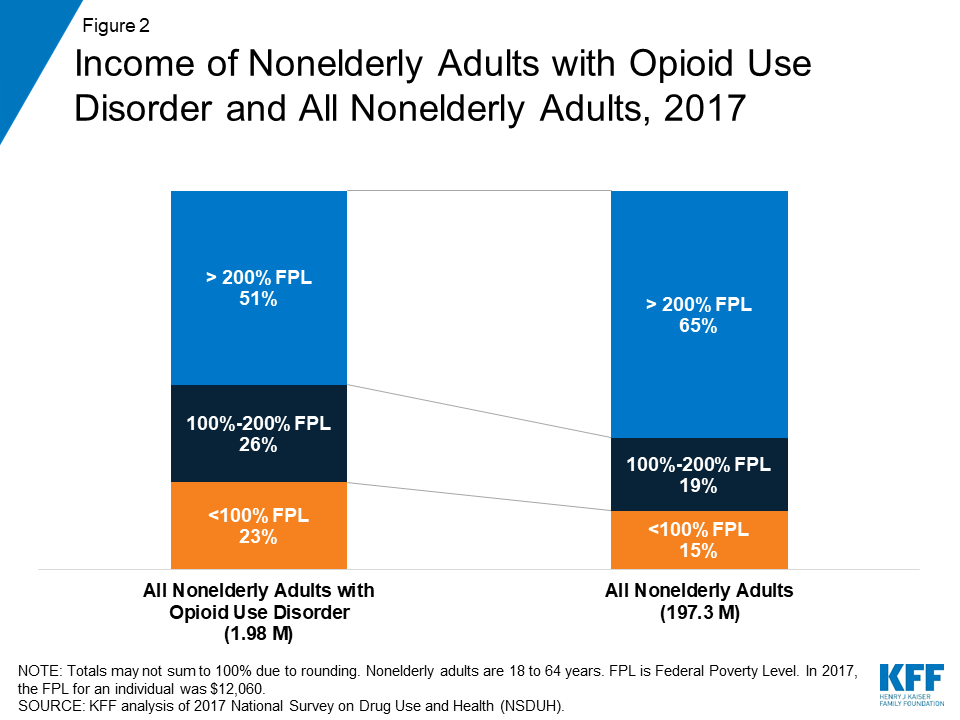

Nearly half of nonelderly adults with OUD had low incomes and almost a quarter were living in poverty. In 2017, 49% of adults with OUD had incomes below 200% FPL ($24,120 for an individual in 2017), compared to only 34% of all nonelderly adults (Figure 2). Additionally, almost a quarter (23%) of those with OUD were poor compared to just 15% of all nonelderly adults.

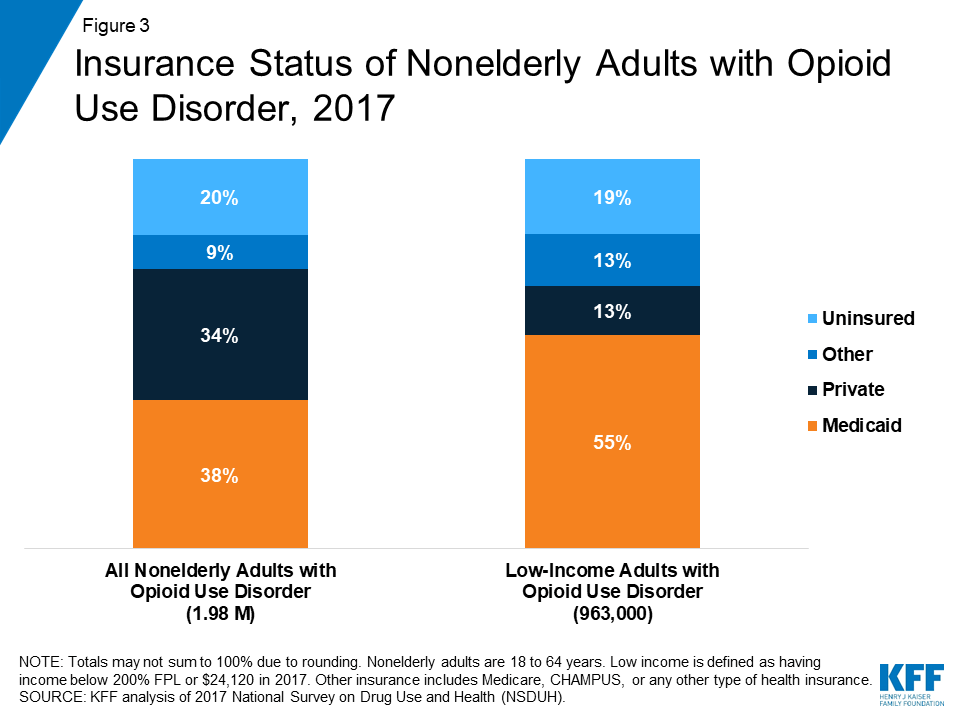

Medicaid covered a disproportionate share of nonelderly adults with OUD and an even greater share of those with low incomes. In 2017, nearly four in ten (38%) were covered by Medicaid, more than double the share of all nonelderly adults covered by Medicaid (16%).4 A similar share of adults with OUD (34%) had private insurance, while one in five was uninsured (Figure 3). Among nonelderly adults with OUD with low incomes, over half (55%) were covered by Medicaid, while only 13% had private insurance and 19% were uninsured.

Utilization of Treatment Services Among Nonelderly Adults with Opioid Use Disorder

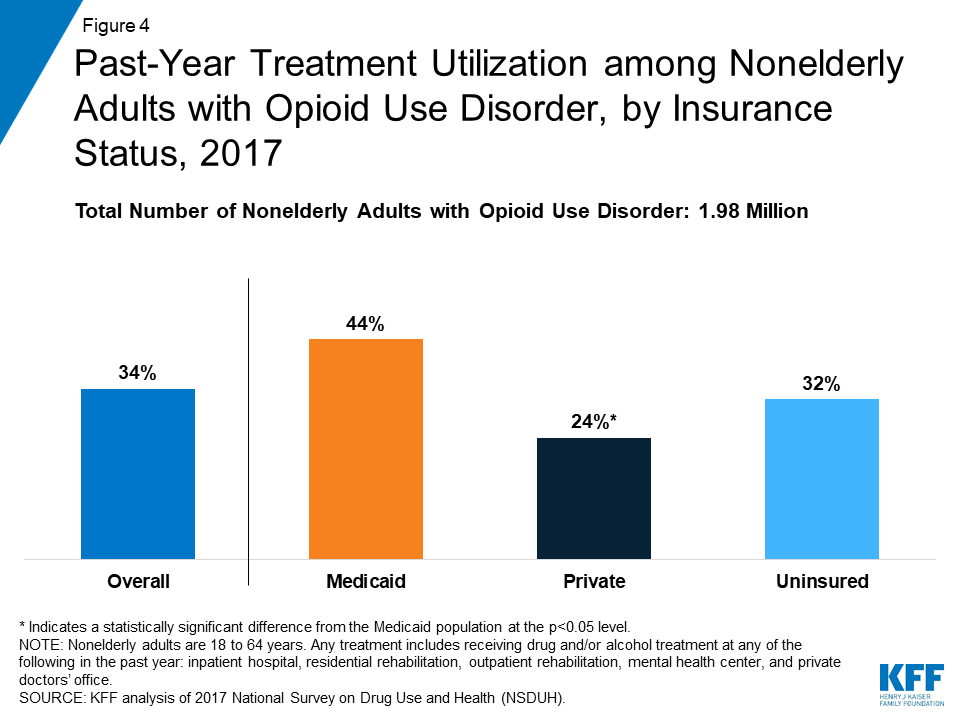

While overall receipt of drug and/or alcohol treatment was low among all nonelderly adults with OUD, those with Medicaid were significantly more likely to receive treatment than those with private coverage. In 2017, just over a third (34%) of adults with OUD received any drug and/or alcohol treatment in 2017 (Figure 4). However, those with Medicaid were nearly twice as likely as those with private insurance to have received drug and/or alcohol treatment (44% vs. 24%). Treatment can be delivered in an inpatient or outpatient setting and can be provided in numerous types of facilities, including hospitals, drug or alcohol rehabilitation facilities (for either inpatient or outpatient services), mental health centers, and private doctors’ offices, among other locations.

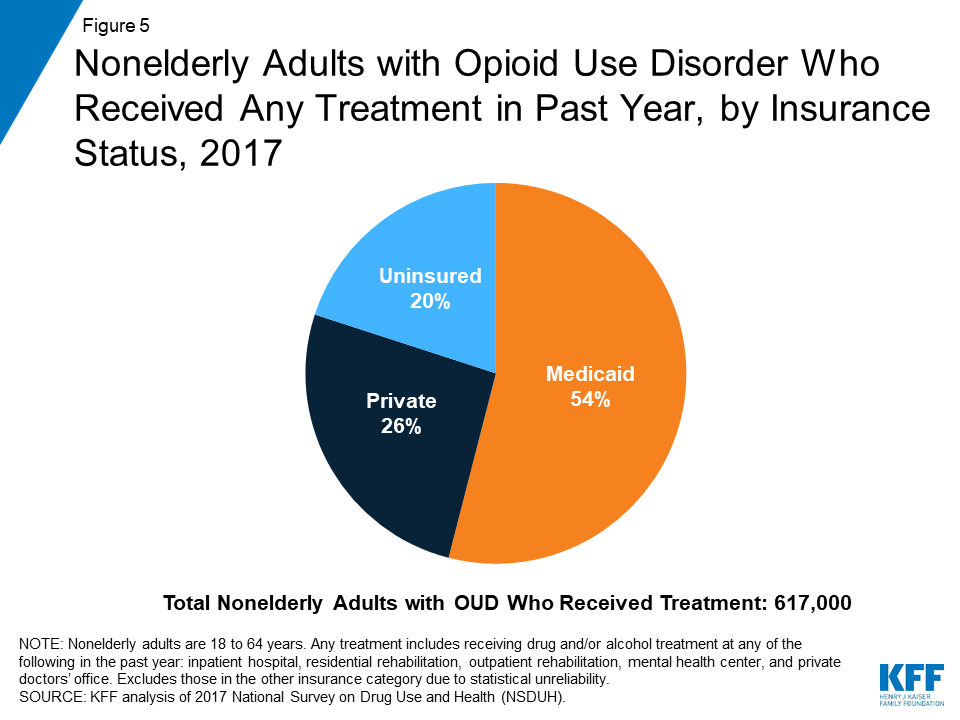

Medicaid covered over half of all nonelderly adults with OUD who received drug and/or alcohol treatment in the past year. In 2017, 617,000 nonelderly adults with OUD reported receiving treatment during the previous year. Of these individuals, 54% had Medicaid coverage while only 26% had private insurance and 20% were uninsured (Figure 5).

Medicaid’s Role in Covering Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Services

State Medicaid programs cover numerous substance use disorder treatment services that fit into several state plan categories, including outpatient treatment, inpatient treatment, prescription drugs, and rehabilitation services. The standard of care for OUD is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), which combines one of three medications (methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) with counseling and other support services.5 All state Medicaid programs cover at least one medication used as part of MAT and most cover all three of these medications.6 State Medicaid programs also cover many counseling and other support services, delivered either as part of MAT or separately. Most of these services are delivered at state option and include detoxification, intensive outpatient treatment, psychotherapy, peer support, supported employment, partial hospitalization, and inpatient treatment.7

Despite the general prohibition in federal law, there are some ways in which states can obtain federal Medicaid funds to pay for substance use disorder treatment services at “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs), an antiquated term in the statute. 8 Federal law has historically prohibited Medicaid payments for services provided to adults age 21-64 in IMDs as a way to preserve state financing of these services.9 However, the final Medicaid managed care regulation that took effect in July 2015, codified pre-existing long-standing federal sub-regulatory guidance that allowed federal Medicaid payments for IMD services without a day limit.10 Additionally, in July 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance stating that states could request federal funding for nonelderly adults primarily receiving substance use disorder services in IMDs through Section 1115 demonstration waivers.11 On November 1, 2017, CMS issued revised guidance that continues to allow states to seek Section 1115 waivers to pay for services provided in IMDs, including substance use disorder services.12 A number of states have sought waivers of the IMD exclusion specifically to expand treatment options for substance use disorder services. As of April 2019, CMS has approved waiver requests in 21 states to provide substance use disorder services in an IMD, and seven states have waiver applications pending with CMS.13 Most recently, the SUPPORT Act, comprehensive legislation addressing the opioid crisis, partially lifted the IMD payment exclusion by creating a new option for states to use federal Medicaid funds for nonelderly adults receiving IMD substance use disorder services up to 30 days a year,14 from October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2023.15

Many states have also applied for other Medicaid Section 1115 behavioral health waivers focused on treating individuals with substance use disorders, including OUD. CMS has approved Section 1115 waivers to expand community-based benefits, which enable states to provide additional services to individuals with behavioral health needs, including supportive housing, supported employment (such as job coaching), and peer recovery coaching. Additionally, CMS has approved waivers that allow states to expand Medicaid eligibility to cover additional populations with behavioral health needs and to implement certain delivery system reforms, such as physical and behavioral health integration and alternative payment models.16

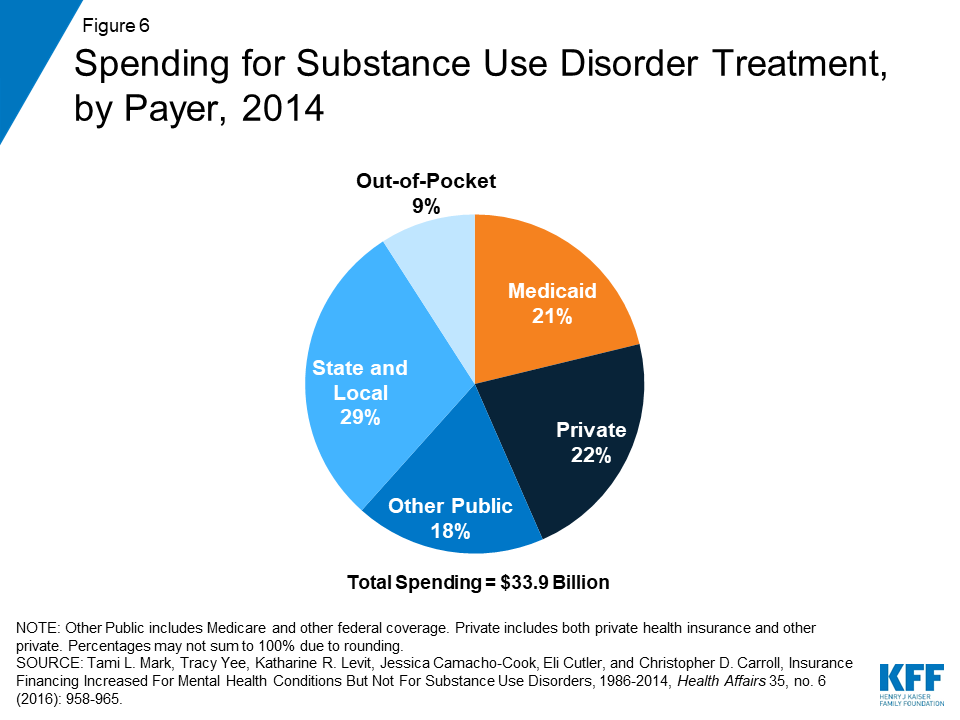

Because of the large number of Medicaid enrollees with OUD and the breadth of treatment services that Medicaid covers, Medicaid finances a substantial proportion of substance use disorder treatment. In 2014, Medicaid financed more than one-fifth (21%) of substance use disorder treatment, which was slightly less than the share covered by all private insurers (22%) (Figure 6). Nine percent of all spending on addiction treatment came from out-of-pocket payments by individuals.17 By 2020, it is projected that Medicaid will finance 28% of substance use disorder treatment services, while other payer types are projected to remain the same.18

Looking Ahead

As the opioid epidemic continues to ravage many parts of the country, particularly as fentanyl has become more pervasive,19 states are increasingly looking to Medicaid to expand coverage and treatment options to stem the crisis. In addition to covering MAT medications and therapy and numerous other treatment services, states are seeking waivers to allow payment for opioid treatment services provided in IMDs, to expand coverage of community-based benefits to support treatment and recovery, and to better integrate behavioral health services, including substance use disorder services with physical health services.

States that have not yet adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion can improve access to treatment by expanding Medicaid, which would enable them to cover many people with OUD who are currently uninsured. At the same time, using 1115 waivers to impose new requirements in Medicaid, including work requirements and premiums, could compromise efforts to address the opioid epidemic. Additional reporting requirements coupled with new premium requirements may also make it more difficult for eligible individuals to enroll in Medicaid and for those currently enrolled to keep their coverage. Utilization of treatment by adults with an OUD is already low; imposing new barriers to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid could further impede those battling OUD from getting the care they need.

Endnotes

- Opioid use disorder is defined as the dependence or abuse of opioids in the past year. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). ↩︎

- Jarlenski, M., Barry, C. L., Gollust, S., Graves, A. J., Kennedy-Hendricks, A., & Kozhimannil, K. (2017). Polysubstance Use Among US Women of Reproductive Age Who Use Opioids for Nonmedical Reasons. American journal of public health, 107(8), 1308–1310. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.303825, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5508143/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). ↩︎

- “Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT),” SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration), available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/. ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford, et al., “States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, State Policies for Behavioral Health Services Covered Under the State Plan (Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, June 2016), https://www.macpac.gov/publication/behavioral-health-state-plan-services/, ↩︎

- An IMD is a “hospital, nursing facility, or other institution of more than 16 beds, that is primarily engaged in providing diagnosis, treatment, or care of persons with mental diseases [sic], including medical attention, nursing care, and related services.” 42 U.S.C. § 1396d (i). ↩︎

- David G. Smith and Judith D. Moore, Medicaid Politics and Policy, at 188-89 (2008); see also CMS Medicaid Manual § 4309 (A)(2), https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/guidance/Manuals/Paper-Based-Manuals-Items/CMS021927.html. ↩︎

- Julia Paradise and MaryBeth Musumeci, “CMS’s Final Rule on Medicaid Managed Care: A Summary of Major Provisions,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed April 2018, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/cmss-final-rule-on-medicaid-managed-care-a-summary-of-major-provisions/, ↩︎

- CMS, New Service Delivery Opportunities for Individuals with a Substance Use Disorder, SMD #15-003, (July 27, 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd15003.pdf. ↩︎

- CMS, Strategies to Address the Opioid Epidemic, SMD #17-003 (Nov. 1, 2017), https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd17003.pdf. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Hinton, MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, Larisa Antonisse, and Cornelia Hall, “Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: The Current Landscape of Approved and Pending Waivers,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers/. ↩︎

- The 30 days do not need to be consecutive. H.R. 6, § 5052 (a)(2) (creating new Social Security Act § 1915 (l)(2)). ↩︎

- H.R. 6, § § 5051-5052; see also Kaiser Family Foundation, Federal Legislation to Address the Opioid Crisis: Medicaid Provisions in the SUPPORT Act (Oct. 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/federal-legislation-to-address-the-opioid-crisis-medicaid-provisions-in-the-support-act/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, April 18, 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/. ↩︎

- Tami L. Mark, et al., “Insurance Financing Increased For Mental Health Conditions But Not For Substance Use Disorders, 1986-2014,” Health Affairs 35, no. 6 (June 2016):958-965. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Projections of National Expenditures for Treatment of Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2010–2020. HHS Publication No. SMA-14-4883. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4883.pdf. ↩︎

- “Synthetic Opioid Data,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 2018, https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/fentanyl.html. ↩︎