Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey

| Key Takeaways |

This 17th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) provides data on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2019. See Appendix Tables 1-20 for state data. Over time, Medicaid has evolved from a program with limited eligibility and burdensome enrollment rules that excluded many low-income adults and created barriers to enrollment for eligible individuals to a modernized program that, along with CHIP, provides a broad base of health coverage for the low-income population and more effectively and efficiently connects eligible individuals to coverage. The survey data show:

Looking ahead, one key question is whether there will be continued advances to expand coverage and streamline enrollment or whether emerging policies will erode coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA. The Trump Administration is promoting new Medicaid eligibility requirements through waivers and its proposed budget and has approved a growing number of waiver requests from states, including work requirements, which have never previously been approved for the program. These provisions require complex and costly documentation and administrative efforts that would likely increase barriers to coverage and lead to coverage losses among eligible individuals. Other factors outside of Medicaid may also be contributing to enrollment declines among eligible individuals, including shifting immigration policy. |

This 17th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) provides data on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2019. It is based on a telephone survey of state Medicaid and CHIP officials conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. Appendix Tables 1-20 include state data. The survey data over the past 17 years document how Medicaid has evolved from a program with limited eligibility and burdensome enrollment rules that excluded many low-income adults and created barriers to enrollment for eligible individuals to a modernized program that, with CHIP, provides a broad base of health coverage for the low-income population and more effectively and efficiently connects eligible individuals to coverage. Emerging policies to add Medicaid eligibility requirements could lead to coverage losses and increase the complexity of enrollment processes, eroding coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA.

Eligibility

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), many poor parents and other adults remained ineligible for Medicaid. Under previous rules, Medicaid eligibility was limited to certain groups of individuals with limited incomes. Eligibility for parents was very restricted and states could not receive federal Medicaid matching funds to cover other non-disabled adults. The ACA helped fill longstanding gaps in coverage by expanding Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) ($29,435 for a family of three or $17,236 for an individual as of 2019) and provided enhanced federal funding to states for expansion coverage.

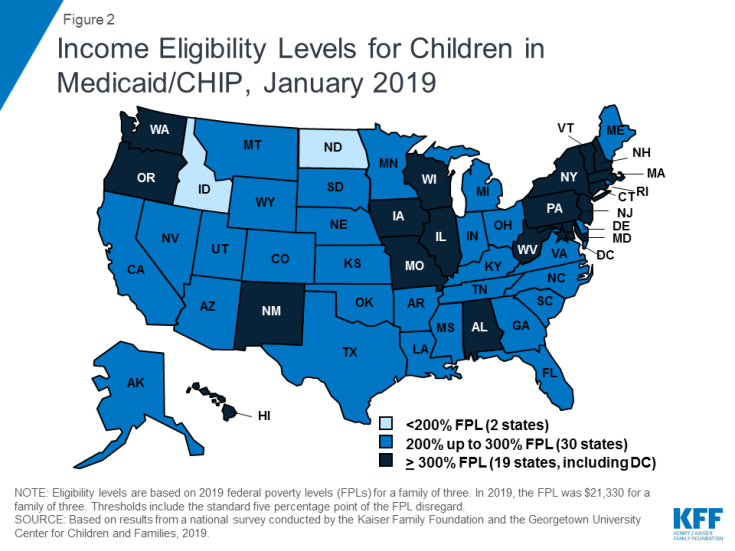

Most states have expanded Medicaid to low-income adults under the ACA, and five additional states took steps forward with expansion in the past year. Virginia and Maine became the latest states to implement the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019, significantly increasing eligibility for parents and other adults (Figure 1). Voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah passed ballot initiatives in 2018 to adopt the expansion, although it had not been implemented as of January 2019, and Utah and Idaho are seeking to add restrictions to the expansion. With this action, 37 states, including DC, had adopted the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019.

Figure 1: Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults based on Adoption of Medicaid Expansion as of January 2019

In the 14 states that had not yet adopted the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019, eligibility for parents and other adults remains very restrictive. The median eligibility level for parents in these states is 40% FPL ($8,532 per year for a family of three as of 2019) and other adults remain ineligible regardless of their income in all of these states, except Wisconsin. In these states, 2.5 million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap, earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for subsidies to purchase insurance through the Marketplace, which become available at 100% FPL.1

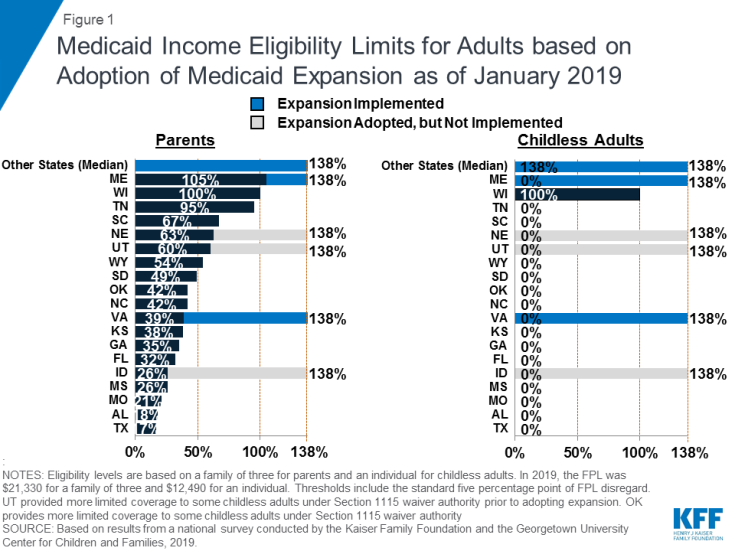

Medicaid and CHIP eligibility for children and pregnant women remains stable and robust. Eligibility levels for children and pregnant women are well above those for parents and other adults in almost all states. As of January 2019, 19 states, including DC, extend eligibility levels for children to 300% FPL or above (Figure 2), and nearly half of states provide eligibility to pregnant women above 200% FPL. The median income eligibility limit is 255% FPL ($54,392 per year for a family of three as of 2019) for children and 200% FPL ($42,660 for a family of three as of 2019) for pregnant women as of January 2019. The stability of children’s coverage reflected Congressional action in 2018 to continue CHIP funding through 2027 and retain the maintenance of effort (MOE) provision that preserves eligibility levels and enrollment procedures for children.

In 2018, additional states obtained Section 1115 waivers to add new eligibility requirements to their Medicaid programs. As of January 2019, 13 states had approved waivers allowing one or more eligibility requirements including conditioning eligibility on meeting a work requirement, adding completion of a health risk assessment as an eligibility requirement, charging premiums or monthly contributions, eliminating retroactive eligibility, delaying coverage until the first premium payment, and/or locking enrollees out of coverage for a period of time if they have unpaid premiums or do not complete timely renewals or report changes in circumstances.2 Many of these provisions require complex and costly administrative efforts that run counter to the streamlined enrollment processes under the ACA and lead to increased barriers to coverage and coverage losses among eligible individuals.

Enrollment and Renewal

Prior to the ACA, many states relied on paper-based, manual enrollment processes with burdensome requirements that could take days and weeks in some states. In addition to expanding Medicaid to adults, the ACA accelerated the adoption of new data-driven enrollment and renewal processes to connect individuals to coverage more quickly and conveniently and reduce the paperwork burden on states and individuals. These changes applied to all states regardless of whether they adopted the Medicaid expansion. The ACA also provided states enhanced federal funding for system upgrades to facilitate these improvements.

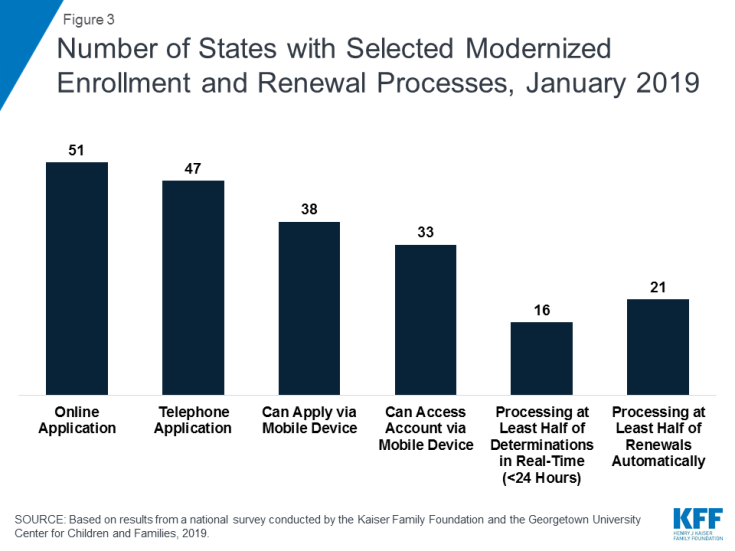

As of January 2019, many states provide a modernized, streamlined enrollment and renewal experience for individuals, reflecting the policies established by the ACA. With Tennessee rolling out a new eligibility system, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in all states for the first time as of January 2019 (Figure 3). Individuals can also apply by phone in the majority of states and, in many states, individuals can use a mobile device to apply or access an online account. Although online applications offer potential benefits to individuals and states, other application pathways, including in-person and mail, remain important, particularly for people with limited computer or internet access. Reflecting increased use of electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria, the majority of states can complete real-time determinations (within 24 hours) (46 states) and automated renewals (46 states), with 16 states making at least half of determinations in real-time and 21 states completing at least half of renewals automatically. Reflecting these broad system and process changes, most states indicated improvements in one or more areas of eligibility operations compared to before the ACA.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Federal regulations establish parameters for premiums and cost sharing for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees that reflect their limited ability to pay health care costs. Given their modest incomes, research shows that premiums serve as a barrier to enrollment for low-income families and copayments can limit utilization of needed health care.3

Kentucky and New Mexico eliminated cost sharing for children during 2018; otherwise, premiums and cost sharing for children remained largely stable. This stability, in part, reflects that states generally cannot increase premiums for children under the MOE provision included in the CHIP funding extension through 2027.

Premiums remain limited among parents and other adults, although additional states received waiver approval to impose premiums or monthly contributions on these groups during 2018. Some states have obtained waiver approval to charge premiums or monthly contributions not otherwise allowed under federal rules. As of January 2019, five states (Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and Montana) were charging premiums or monthly contributions for parents or other adults. Several additional states have received waiver approval for premiums or monthly contributions for adults, but they were not implemented as of January 2019. Some of these waivers also allow individuals to be locked out of coverage for a period of time if they are disenrolled due to non-payment and to delay coverage until after the first premium is paid. States can charge nominal cost sharing for adults in Medicaid under federal rules, and most states charge cost sharing for parents who were eligible for Medicaid through traditional pathways prior to the ACA and other adults.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, one key question is whether there will be continued advances to expand coverage and streamline enrollment processes or whether emerging policy changes will erode coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA.

Additional states may expand Medicaid, which would increase access to coverage for low-income adults and have positive effects on access to and use of care and state budgets and economies.4 However, if states attach waiver provisions such as work requirements or other restrictions to expansion, the positive reach and impact would be limited. Recently, some states have indicated interest in a partial expansion to an income level below 138% FPL with the ACA enhanced federal match rate.5 Relative to full expansion, partial expansions could limit coverage and potentially increase federal costs. While states can pursue waivers to extend coverage to a lower income level without access to the enhanced federal match, no waivers to allow an enhanced match for a partial expansion have been approved to date, and guidance from the previous administration prohibited use of the enhanced match for “partial expansions.”

Renewed CHIP funding protects children’s eligibility levels through 2027, but states that extend eligibility above 300% FPL will have the option to reduce eligibility starting in October 2019. When Congress continued funding for CHIP in 2018, it retained the MOE provision that requires states to preserve Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies for children. However, starting in October 2019, the MOE only applies to children’s coverage up to 300% FPL, meaning that states with eligibility limits above this level could reduce eligibility in the future. This change coincides with the beginning of the phase-out of the temporary 23-percentage point boost in federal CHIP matching rates, leaving states to resume paying a larger share of CHIP costs.

Emerging state and federal policies to add Medicaid eligibility requirements could erode the coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA. The Trump Administration is promoting new Medicaid eligibility requirements through waivers and its proposed budget and has approved a growing number of waiver requests from states, including work requirements, which have never previously been approved for the program. Some states are no longer moving forward with implementing waiver provisions following a change in leadership in the 2018 elections,6,7 while other states are considering adding waiver provisions.8,9,10,11 These types of requirements create barriers to coverage and increase administrative burdens and costs for states.12,13 As such, they will likely dampen potential coverage gains and lead to coverage losses.

Other policy changes may lead to coverage losses among eligible low-income families and growing administrative burdens on states. In 2017, coverage gains stalled and began to reverse for the first time since implementation of the ACA, and Medicaid enrollment of adults and children declined in 2018.14,15,16 Some of the decline in Medicaid enrollment could reflect the improving economy. However, some factors may be leading to a drop in enrollment among eligible individuals. While states’ growing use of technology and automation has led to improvements for individuals and states, there are concerns emerging in some states that eligible individuals may be losing coverage due to process-related issues.17,18,19 Further, other policy changes outside of Medicaid could be dampening enrollment. For example, the Trump administration substantially decreased funding for outreach and enrollment assistance, which is pivotal for helping eligible individuals get and stay enrolled in coverage. In addition, shifting immigration policies, including a proposed rule to make changes to public charge policy, will likely lead to broad decreases in participation in Medicaid among legal immigrant families and their primarily U.S.-born children and increase administrative burdens on states.20 Twenty states reported that they would need to change applications, forms, or other guidance, conduct additional staff training, and/or increase outreach and education to immigrant families if the public charge rule is finalized, while most of the remaining states indicated they could not yet determine how the rule would impact their operations.