2016 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Introduction

The 2016 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health is the latest in a series of surveys designed, conducted, and analyzed by the Kaiser Family Foundation in order to shed light on the American public’s perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes about the role of the United States in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. This most recent survey updates trends on Americans’ perceptions of the most urgent problems facing developing countries, views on U.S. spending on health, and U.S. priorities for women’s health in developing countries. It also explores new questions on Americans’ awareness of the Zika virus outbreak and recent U.S. efforts to combat the outbreak both at home and in developing countries.

Executive Summary

The latest survey finds that a majority of the public wants the U.S. to take either the leading role or a major role in trying to solve international problems generally, as well as in improving health for people in developing countries specifically. However, improving health for people in developing countries is not one of the public’s top priorities for the ways in which the U.S. might engage in world affairs, falling behind fighting global terrorism and protecting human rights. Seven in ten Americans believe that the current level of U.S. spending on health in developing countries is too little or about right, yet the public is somewhat skeptical about the ability of more spending to lead to progress, with more than half saying that spending more money will not lead to meaningful progress. Republicans and independents are more skeptical than Democrats, and these partisan differences have increased over time. Another notable trend is the decreasing visibility of U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries; just over a third of the public says they have heard “a lot” or “some” about these efforts in the past 12 months, a decrease of 21 percentage points since 2010.

The most recent survey took an in-depth look at the public’s views on the U.S. role in improving women’s health, with a particular focus on the recent outbreak of the Zika virus in Central and South America. Most Americans view promoting opportunities for women and girls as an important priority for U.S. engagement in foreign affairs, and about half (52 percent) say U.S. government is currently not doing enough to improve the lives of women and girls in developing countries. The public also largely recognizes that most women in developing countries are disadvantaged compared with their male counterparts, and that most women in developing countries (including those affected by Zika) do not have adequate access to birth control. Despite this, there are mixed reactions to U.S. involvement in this area. While most want the U.S. to help women in Zika-affected countries access birth control, the public is split into equal thirds who say the U.S. is doing enough or not doing enough to help women in these countries make family planning and preventive health decisions (with another third unsure).

Section 1: Views Of U.s. Role In World Affairs And In Global Health Efforts

Most See a Major Role for U.S. in World Affairs Generally and in Global Health Specifically

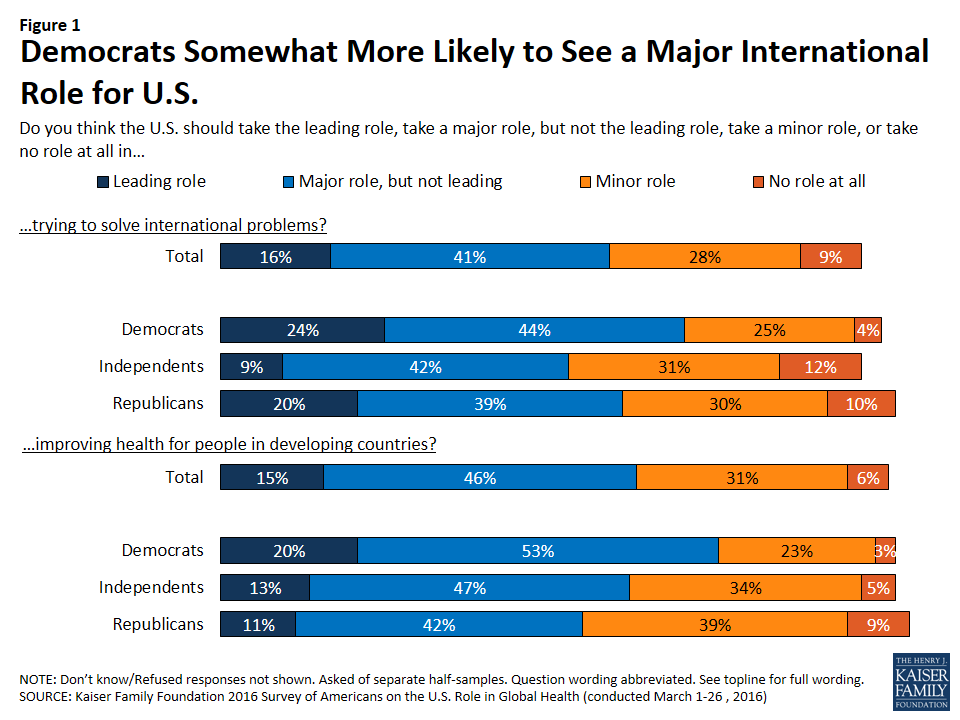

Broadly, the public is largely supportive of the U.S. playing a significant role in trying to solve international problems. About six in ten Americans (57 percent) say the U.S. should play at least a major role in world affairs, including 16 percent who say the U.S. should take the leading role and 41 percent who say the U.S. should play a major role but not the leading one. This is a decline from December 2015, when 65 percent said the U.S. should play at least a major role in world affairs, but similar to results from 2012.

| Table 1: Majority Say U.S. Should Take Major or Leading Role in World Affairs | |||

| I would like you think about the role the U.S.should play in trying to solve international problems.Do you think the U.S. should take… | 2012 | 2015 | 2016 |

| …a leading role in world affairs | 17% | 18% | 16% |

| …a major role, but not the leading role | 43 | 47 | 41 |

| …a minor role | 26 | 24 | 28 |

| …no role at all in world affairs | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 3 | 2 | 5 |

Similarly, six in ten Americans (61 percent) say the U.S. should play at least a major role in improving health for people in developing countries, including 15 percent who say we should take the “leading role” and 46 percent who say a “major role.” While majorities of Democrats, Republicans, and independents say the U.S. should take at least a major role in trying to solve international problems and improving health for people in developing countries, Democrats are somewhat more likely to support such a role.

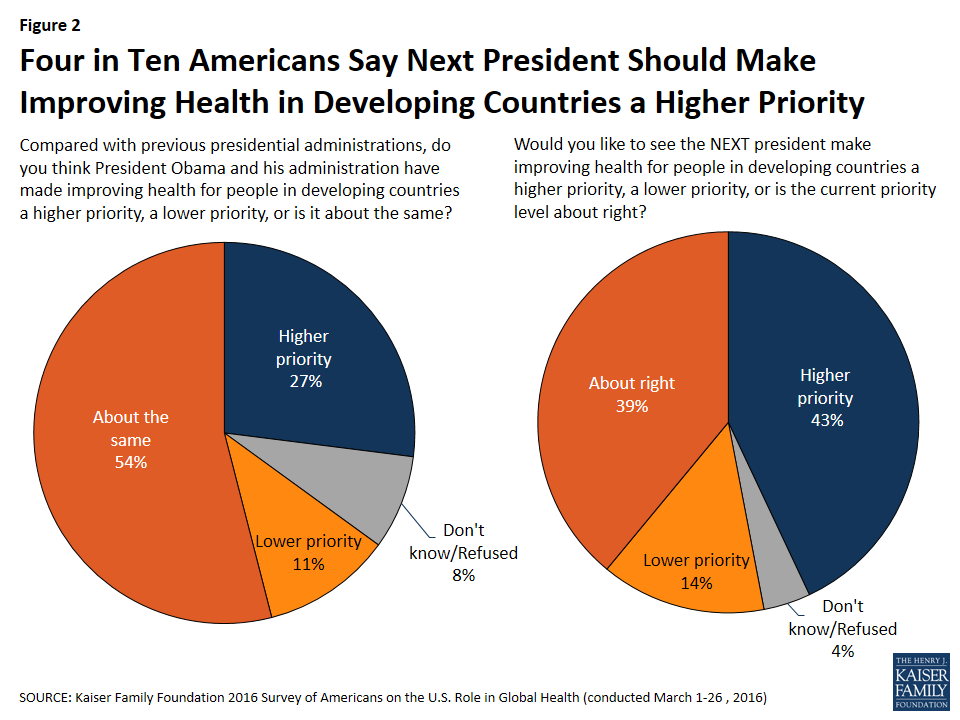

The majority of Americans think President Obama and his administration have made improving health for people in developing countries about the same level of a priority (54 percent) or a higher priority (27), compared to previous presidential administrations, with only about one in ten (11 percent) saying President Obama has made it a lower priority. Consistent with the overall sense that the U.S. should take a major role in this area, over four in ten (43 percent) say they would like the next president to make improving health for people in developing countries an even higher priority, while a similar share (39 percent) say the current priority level is about right and just 14 percent would like it to be a lower priority. Democrats are more likely to say that President Obama has made improving health a higher priority (38 percent) and are more likely to say they would like to see the next president make it a higher priority (53 percent) compared with independents (23 percent and 42 percent) or Republicans (21 percent and 31 percent).

Improving Health in Developing Countries Viewed as One of Many Important Priorities

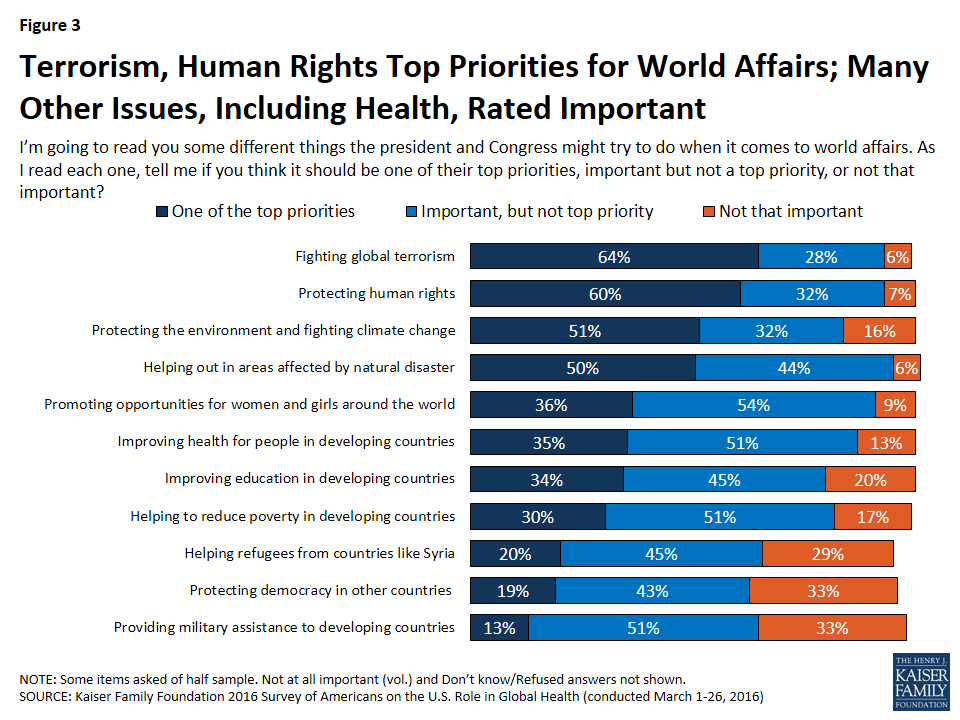

When it comes to different ways in which the U.S. might engage in world affairs, fighting global terrorism (64 percent) and protecting human rights (60 percent) top the public’s priority list. These are closely followed by protecting the environment and fighting climate change (51 percent) and helping out in areas affected by natural disaster (50 percent).

While improving health for people in developing countries does not top the list of priorities, more than one-third (35 percent) of Americans say it is one of the top priorities, and another 51 percent deem it an important priority. This is similar to the share that say promoting opportunities for women and girls around the world (36 percent) and improving education in developing countries (34 percent) are a top priority, and slightly more than the share who say helping to reduce poverty in developing countries (30 percent) is a top priority. Fewer prioritize helping refugees from countries like Syria (20 percent), promoting democracy in other countries (19 percent), and providing military assistance to developing countries (13 percent).

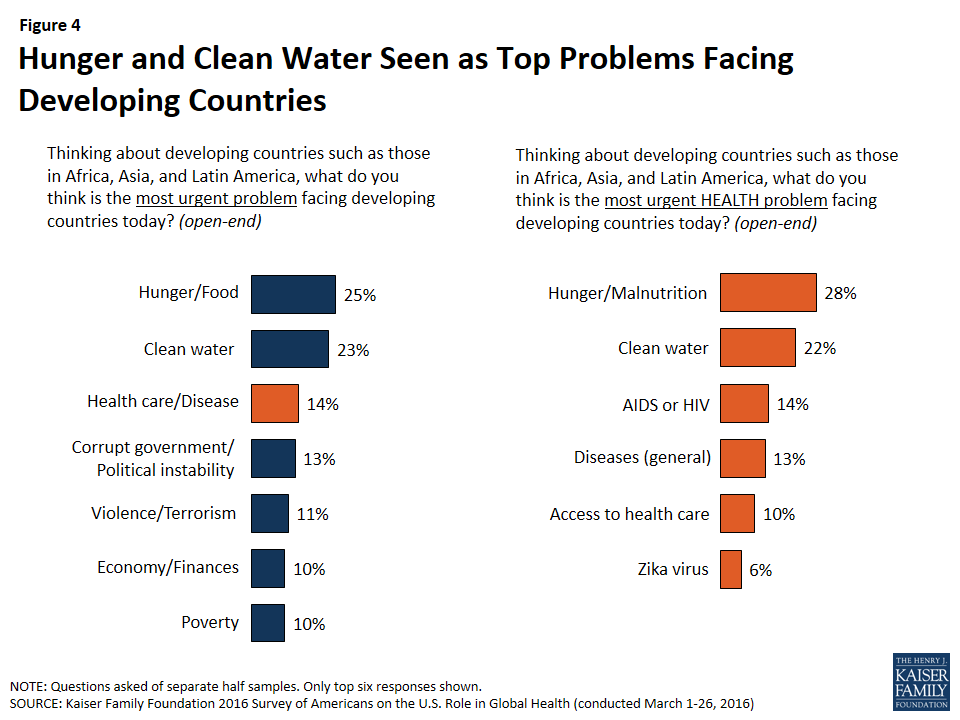

Despite the fact that improving health for people in developing countries does not top the public’s list of priorities for world affairs, two issues related to health – hunger and clean water – are named by the largest shares of Americans as the most urgent problems facing developing countries. In an open-ended question, one in four Americans name hunger or lack of food as the most urgent problem facing developing countries, followed closely by 23 percent who mention clean water. When the question is framed in terms of the most urgent health problem facing developing countries, the top two responses are similar: 28 percent name hunger or malnutrition and 22 percent say clean water.

The share of Americans who name clean water as an urgent problem in both these questions has increased significantly in the past four years. In 2012, only 7 percent of Americans said that clean water was one of the most urgent problems facing developing countries, and just 12 percent named it as the one of the most urgent health problems. The increased concern regarding access to clean water in developing countries may be due to recent media attention about water quality issues in the U.S., particularly surrounding the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

| Table 2: Percent of Americans Who Say Clean Water is an Urgent Problem | |||

| 2012 | 2016 | Percent Change from 2012 to 2016 | |

| Clean water is an urgent problem | 7% | 23% | +16 percentage points |

| Clean water is an urgent HEALTH problem | 12 | 22 | +10 percentage points |

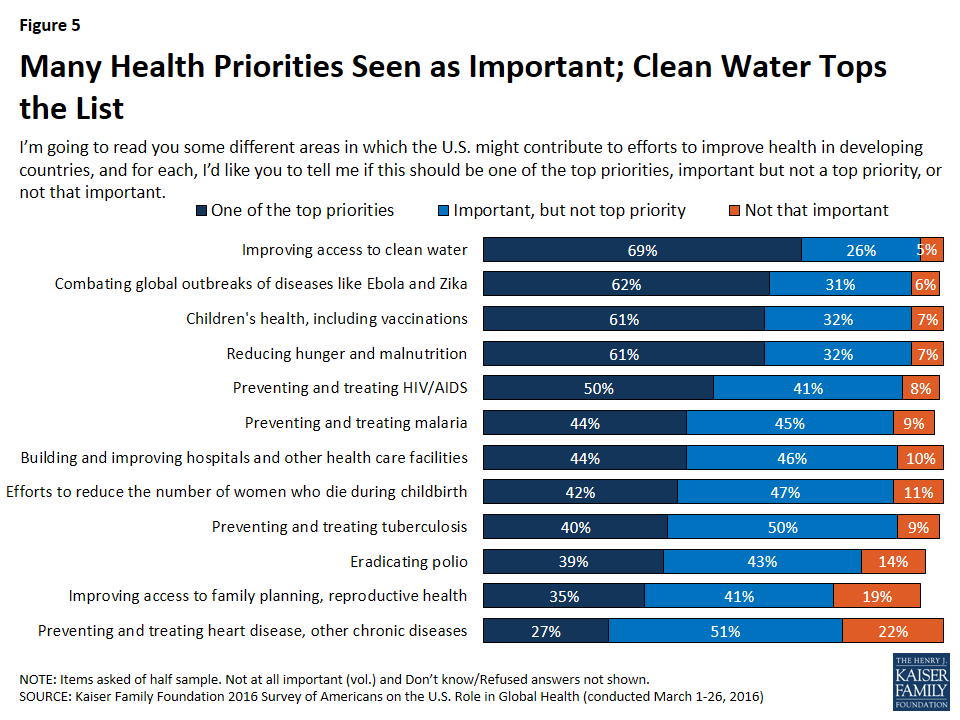

The focus on clean water and reducing hunger is also evident in opinions about priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries. Topping the list, 69 percent of Americans say that improving access to clean water should be one of the top priorities. This is slightly more than the percent who say by combating global outbreaks of diseases like Ebola and Zika (62 percent), improving children’s health (61 percent), and reducing hunger and malnutrition (61 percent) are top health priorities. While others – including combatting specific diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and polio as well as improving access to family planning – fall farther down the list, majorities of the public view each one of these areas as important, with fewer than a quarter saying each is “not that important.”

Mixed Attitudes on Whether U.S. Efforts Have Led To Progress

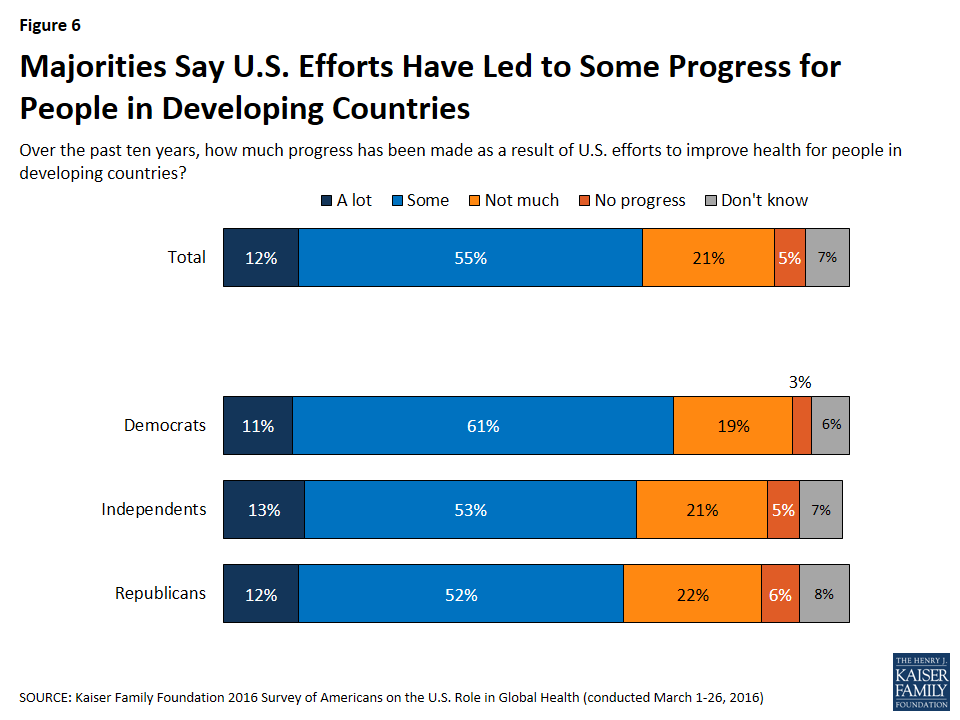

When asked about the success of U.S. global health efforts to date, the majority of the public, 67 percent, believes that over the past ten years, at least some progress has been made as a result of U.S. efforts to improve the health for people in developing countries, though relatively few (12 percent) feel that “a lot” of progress has been made. These views are shared across the political spectrum, with large shares of Democrats, independents, and Republicans all saying that at least some progress has been made.

At the same time that most Americans believe progress has been made as a result of U.S. global health efforts, overall visibility of these efforts appears to have decreased. Just over a third (36 percent) of the public in the most recent survey say that in the past year they have heard “a lot” or “some” about U.S. government efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, down from nearly half in 2013 and 2012, and 57 percent in 2010.

More Support For Global Health Spending Than For Foreign Aid

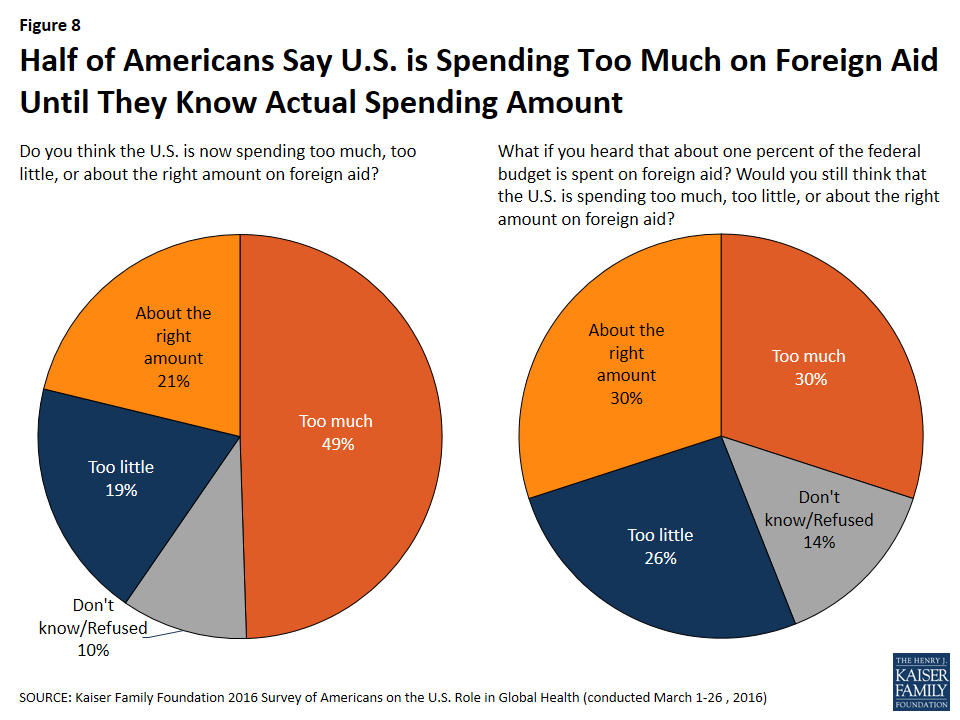

Previous Kaiser surveys have found that the public vastly overestimates the amount of the federal budget that is actually spent on foreign aid. In December 2015, just 3 percent of Americans correctly stated that 1 percent or less of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, and on average, Americans say spending on foreign aid makes up 31 percent of the federal budget.1 The 2016 survey finds that half of Americans say the U.S. is spending “too much” on foreign aid while only one in five say the U.S. is spending “too little” (19 percent) or the right amount (21 percent). Yet, after hearing the fact that foreign aid spending is about one percent of the federal budget, the percent of individuals who say spending is “too much” drops from 49 percent to 30 percent.

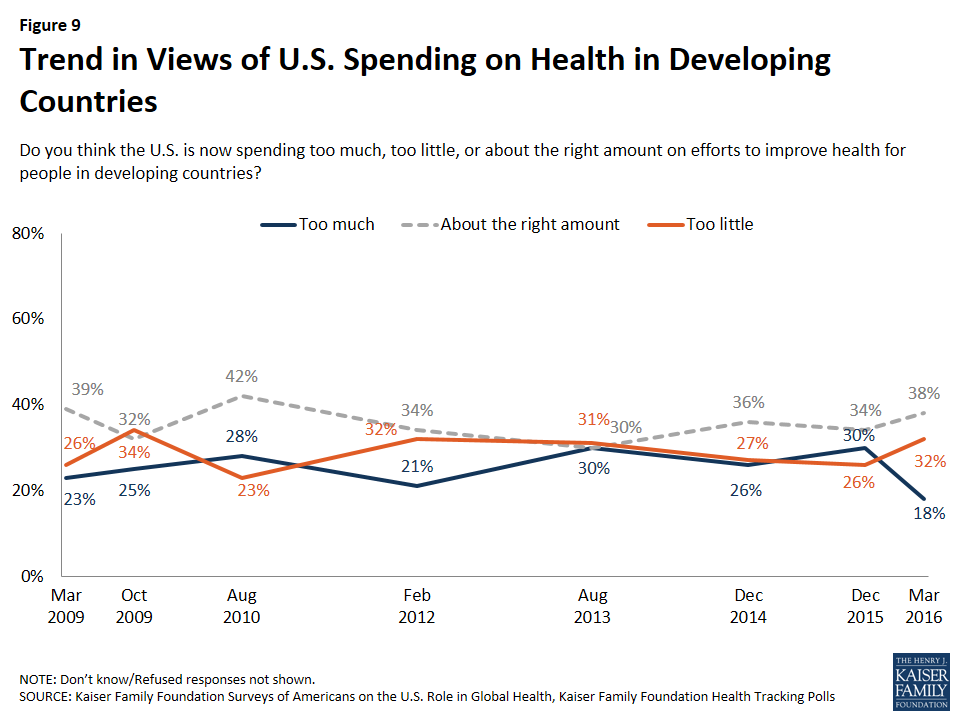

The public is more supportive of U.S. spending on global health than foreign aid more generally. When asked specifically about global health spending, seven in ten say the U.S. is now spending too little (32 percent) or about the right amount (38 percent) on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, and fewer than one-fifth say the U.S. is spending too much (18 percent). Over time, opinions on U.S. spending on improving health in developing countries have remained fairly stable, but the most recent survey does record the lowest share (18 percent) of Americans saying that the U.S. is spending too much on health in developing countries. This share is down from 30 percent in December 2015, a decrease that was seen across partisan subgroups.

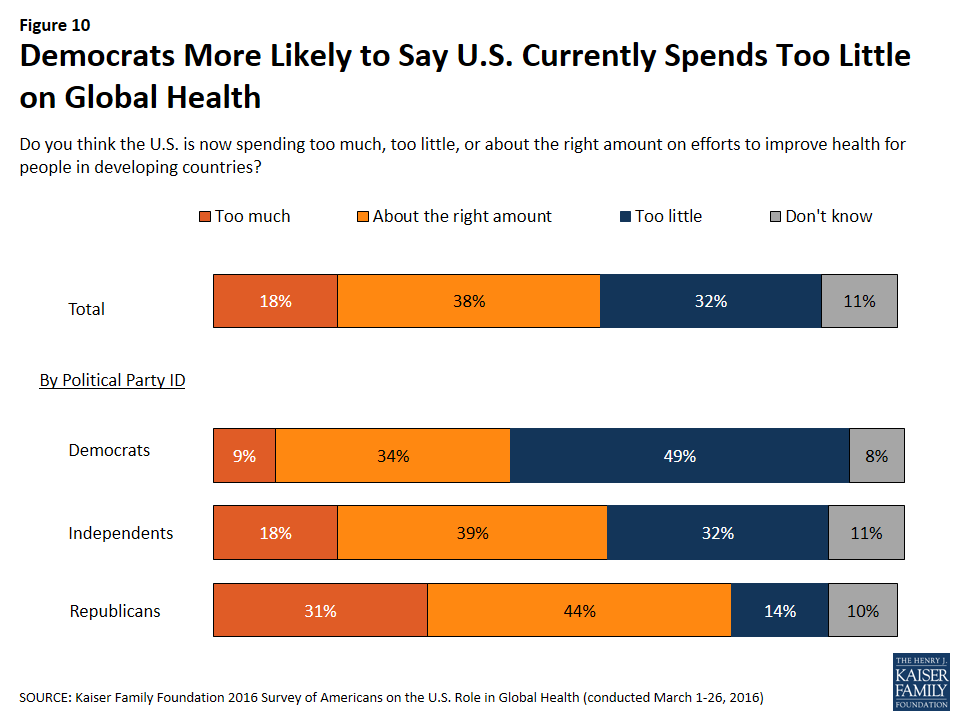

Partisan Differences In Views On U.S. Global Health Spending

Similar to partisan differences on the role of government and federal spending on domestic priorities found in other surveys, there are differences in views of U. S. spending on global health by political party identification. Democrats are more likely to say the country is spending “too little” than “too much” (49 percent vs. 9 percent), whereas Republicans are more likely to say the opposite, that the country is spending “too much” rather than “too little” (31 percent vs. 14 percent). Independents fall in the middle, with 32 percent saying the U.S. spends “too little” and 18 percent saying the U.S. spends “too much” on health in developing countries.

At the same time that the public generally supports maintaining or increasing government spending on health in developing countries, there is also doubt about the potential effectiveness of increased spending from the U.S. and other developed nations. More than half of Americans (57 percent) believe that spending more money will not make much of a difference in improving health for people in developing countries, while about four in ten (39 percent) say that more spending will lead to meaningful progress.

Republicans and independents are particularly skeptical, with majorities saying increased spending will not make much of a difference, 71 percent and 60 percent, respectively. This is compared to nearly six in ten Democrats (56 percent) who say increased spending will lead to meaningful progress and 42 percent who say increased spending will not make much of a difference.

These partisan differences have increased over time, from a margin of 13 percentage points separating the shares of Republicans and Democrats who believed spending more would lead to progress in 2009, compared to a difference of 32 percentage points today.

Americans see a variety of benefits, both at home and abroad, to U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries. About three-fourths (74 percent) say such spending helps protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like Ebola and Zika, and nearly six in ten (59 percent) say it helps to improve the image of the U.S. throughout the world. Two-thirds (68 percent) also believe such spending helps make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient. Americans are more skeptical about the impact of such spending on U.S. national security and the U.S. economy, with about four in ten saying spending helps in these areas (41 percent each) and over half saying it doesn’t have much impact (56 percent each). Partisan differences exist here, too, with Democrats more likely than Republicans to say that spending on global health helps in each of these areas. Still, majorities of Republicans say spending helps protect Americans from disease (68 percent), helps make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient (59 percent), and helps to improve the U.S. image around the world (52 percent).

| Table 3: Democrats More Likely to Say Spending Money on Improving Health in Developing Countries Helps U.S. and Other Countries | ||||

| Percent who say spending money on improving health in developing countries helps… | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| …protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like Ebola and Zika | 74% | 79% | 74% | 68% |

| …make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient | 68 | 75 | 70 | 59 |

| …improve the U.S. image around the world | 59 | 66 | 61 | 52 |

| …U.S. national security by lessening the threat of terrorism originating in developing countries | 41 | 49 | 41 | 30 |

| …the U.S. economy by improving the circumstances of people who can buy more U.S. goods | 41 | 52 | 39 | 28 |

Determining How Global Health Spending Should Be Directed

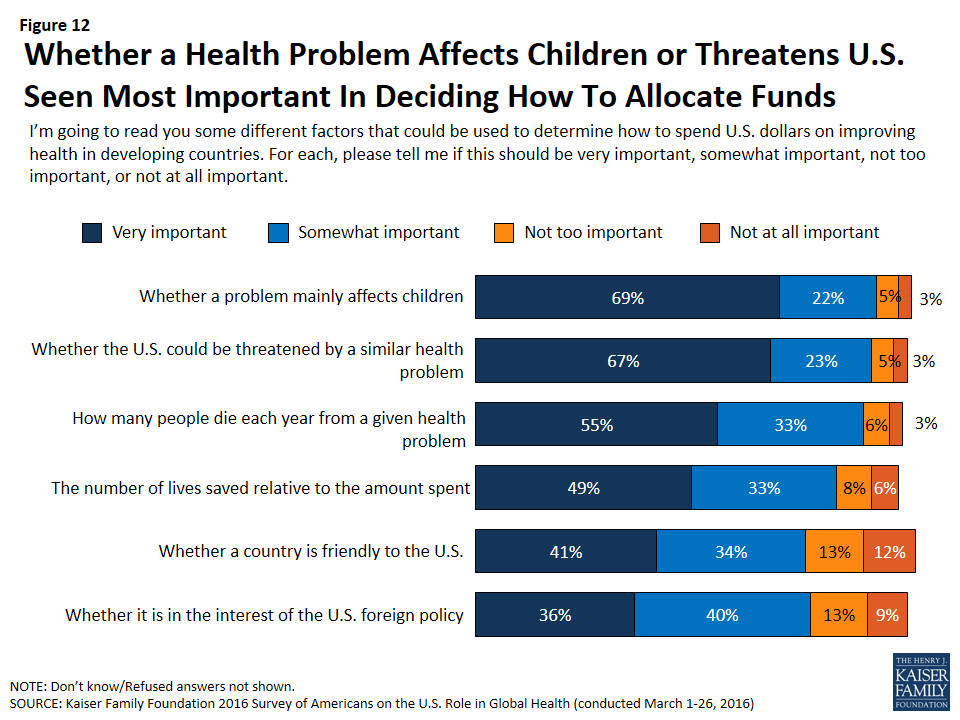

In terms of which criteria should be used to determine allocation of U.S. spending on health in developing countries, the public, regardless of party identification, ranks two factors at the top of the list: whether a problem mainly affects children, and whether the U.S. could be threatened by a similar health problem (nearly seven in ten say each of these should be “very important” in determining how U.S. dollars are spent). Roughly half also say “how many people die each year from a given health problem” (55 percent) and “the number of lives saved relative to the amount spent” (49 percent) should be very important criteria. U.S. foreign policy concerns rank lower on the list, with 41 percent placing great importance on whether a country is friendly to the U.S., and just over one-third (36 percent) saying the same about whether spending is in the interest of U.S. foreign policy.

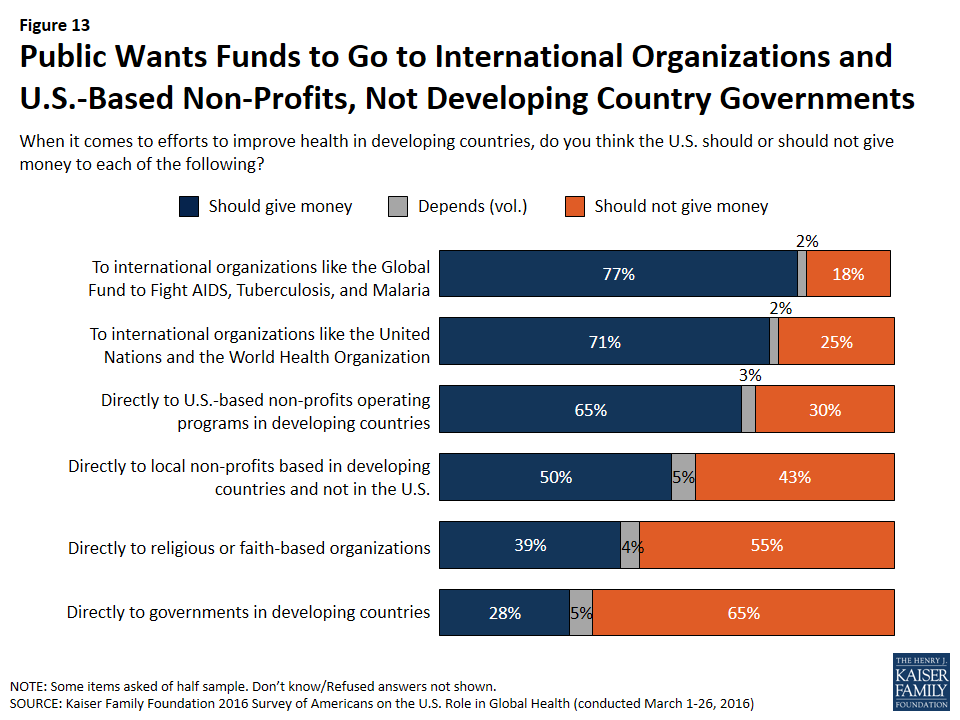

When asked how funds should be directed, a majority of the public thinks the U.S. should give money to international organizations like the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria (77 percent), the United Nations and the World Health Organization (71 percent), or directly to U.S. based non-profits operating programs in developing countries (65 percent). Half of Americans also say the U.S. should give money directly to local non-profits based in developing countries. On the other side, majorities say the U.S. should not give money directly to religious or faith-based organizations (55 percent) or directly to governments in developing countries (65 percent).

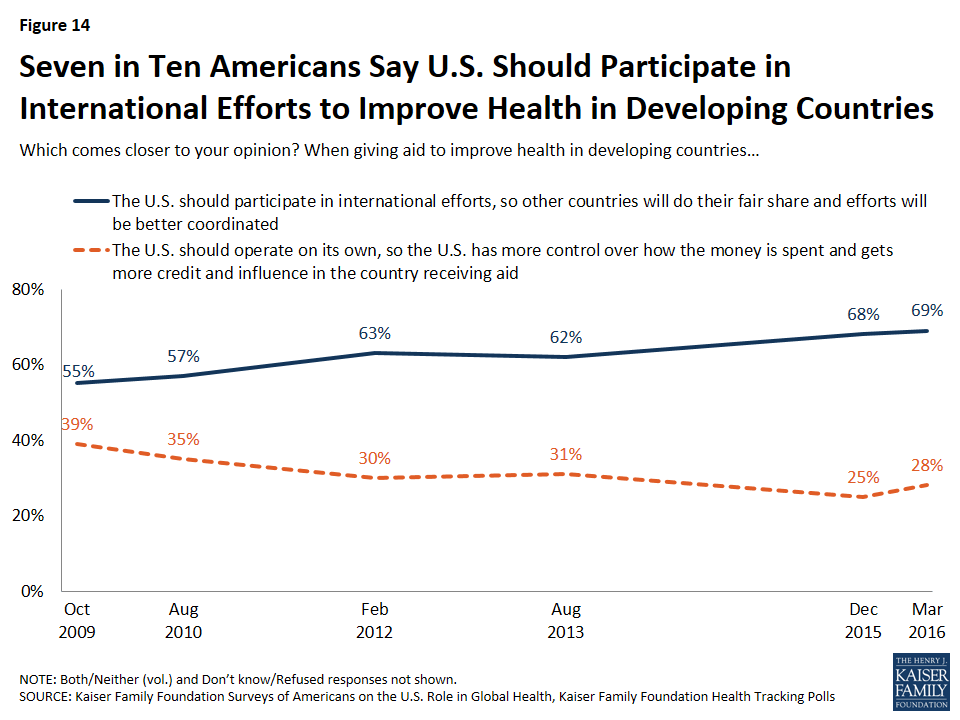

More broadly, seven in ten Americans (69 percent) want the U.S. to participate in international efforts when giving aid to improve health in developing countries, compared to 28 percent who want the U.S. to operate on its own so it has more control over how the money is spent and gets more credit and influence in the country receiving aid. The share who want the U.S. to participate in international efforts has increased steadily over the past seven years, from 55 percent in 2009 to 69 percent in 2016.

Section 2: Views On The U.s. Role Improving The Lives Of Women And Girls In Developing Countries

Many health issues in developing countries have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, and the most recent survey took an in-depth look at the public’s views on the U.S. role in improving women’s health, with a particular focus on the recent outbreak of the Zika virus in Central and South America. As noted above, nearly all Americans (90 percent) view promoting opportunities for women and girls as an important priority for U.S. engagement in foreign affairs, with over a third (36 percent) deeming it one of the top priorities.

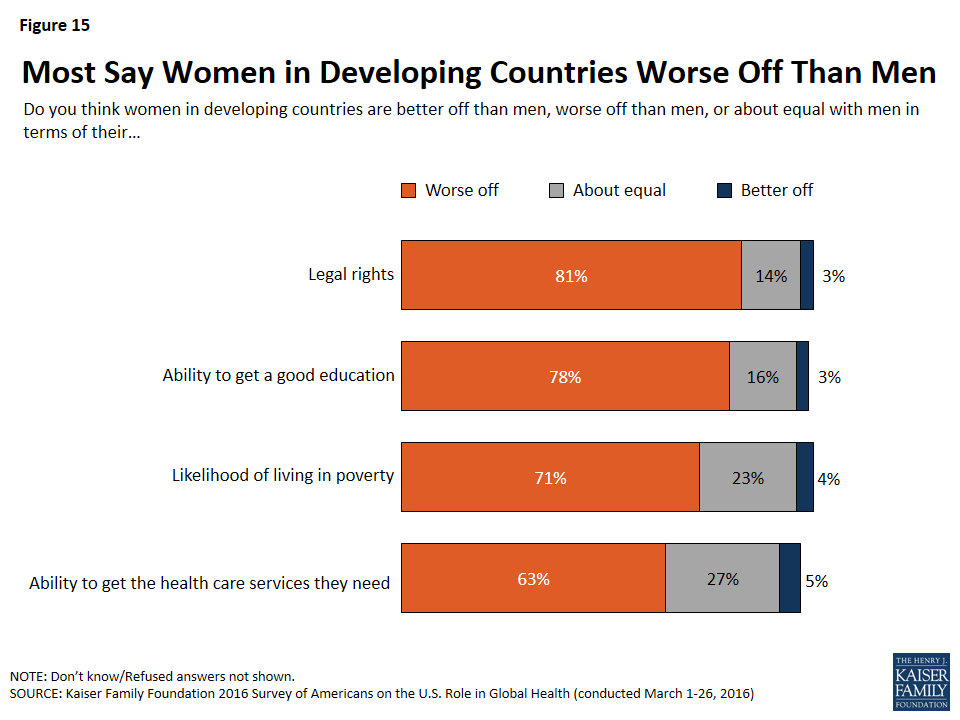

The public also largely recognizes that most women in developing countries are disadvantaged compared with their male counterparts. Large majorities say that women in developing countries are worse off than men in their legal rights (81 percent), ability to get a good education (78 percent), likelihood of living in poverty (71 percent), and their ability to get the health care services they need (63 percent).

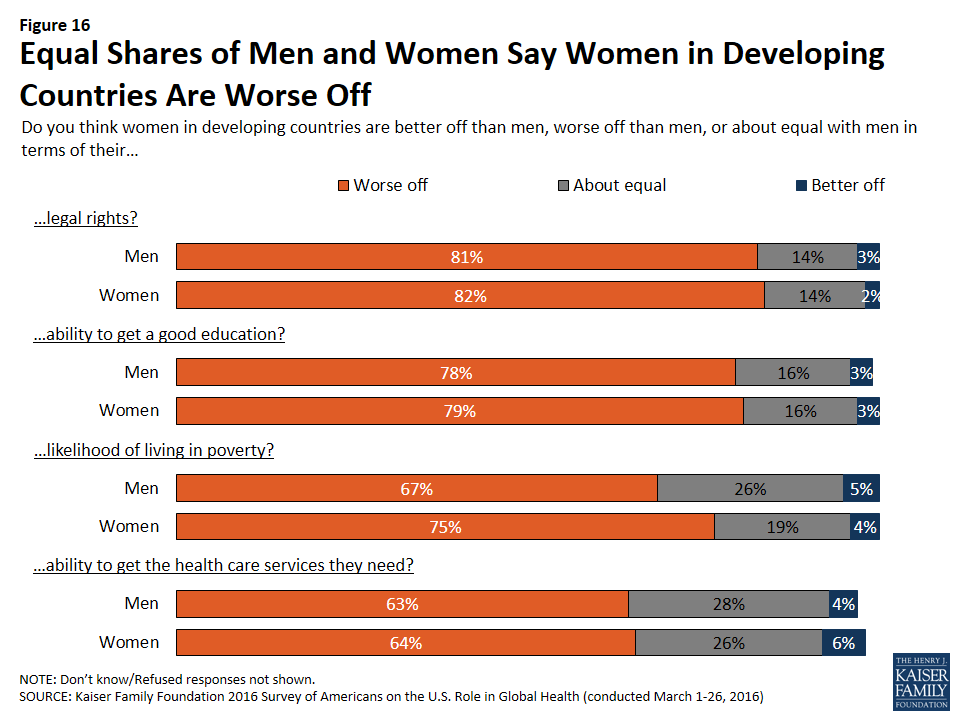

Interestingly, men and women provide similar responses, with majorities of both sexes saying that women are worse off. The only item in which women are more likely than men to say that women are worse off is the likelihood of living in poverty with 75 percent of women saying the women are worse off compared to 67 percent of men.

More than half (52 percent) of Americans think the U.S. government is not doing enough to improve the lives of women and girls in developing countries, while about one-third of Americans (32 percent) think the U.S. government is currently doing enough and 4 percent say the U.S. is either doing too much or shouldn’t be involved. A large majority of Democrats (68 percent) and a slim majority of independents (52 percent) say the U.S. government is not doing enough, while Republicans are more evenly split with 42 percent saying the U.S. government is doing enough and 36 percent saying it is not doing enough.

The Zika Virus

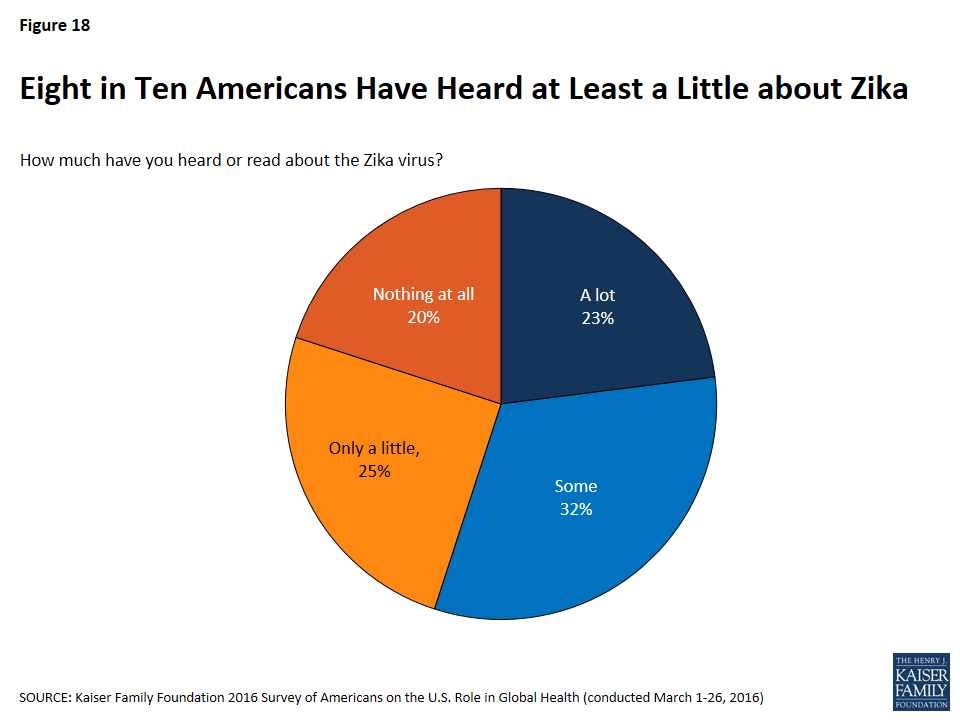

One recent global health development that has a disproportionate impact on women in developing countries is the Zika virus outbreak. The mosquito-borne Zika virus, which has mostly affected South and Central American countries and has been associated with birth defects in babies born to infected mothers, was declared a global health emergency by the United Nations on February 1st.2 Eight in ten Americans say they have heard or read about the Zika virus, with 23 percent saying they have heard or read “a lot” and 32 percent saying they have heard “some.”

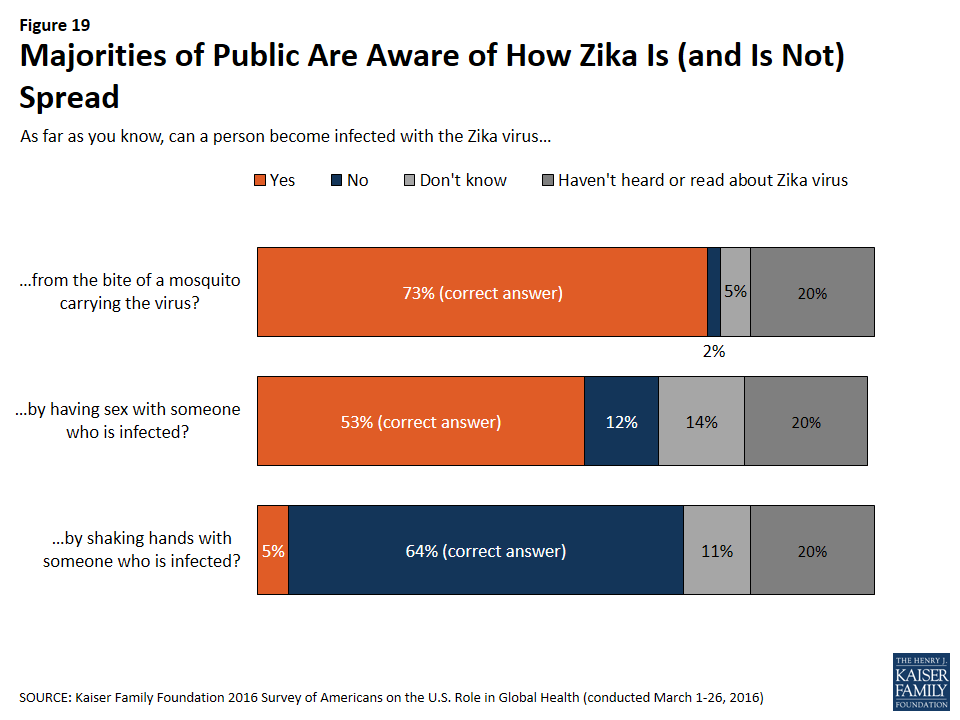

The majority of the American public is aware of the potential ways to spread the virus and potential effects of the virus. About three-quarters (73 percent) are aware that a person can become infected through a bite from an infected mosquito, more than half (53 percent) are aware that a person can become infected by having sex with someone who is infected, and 64 percent are aware that it does not appear to be spread through shaking hands with an infected person.

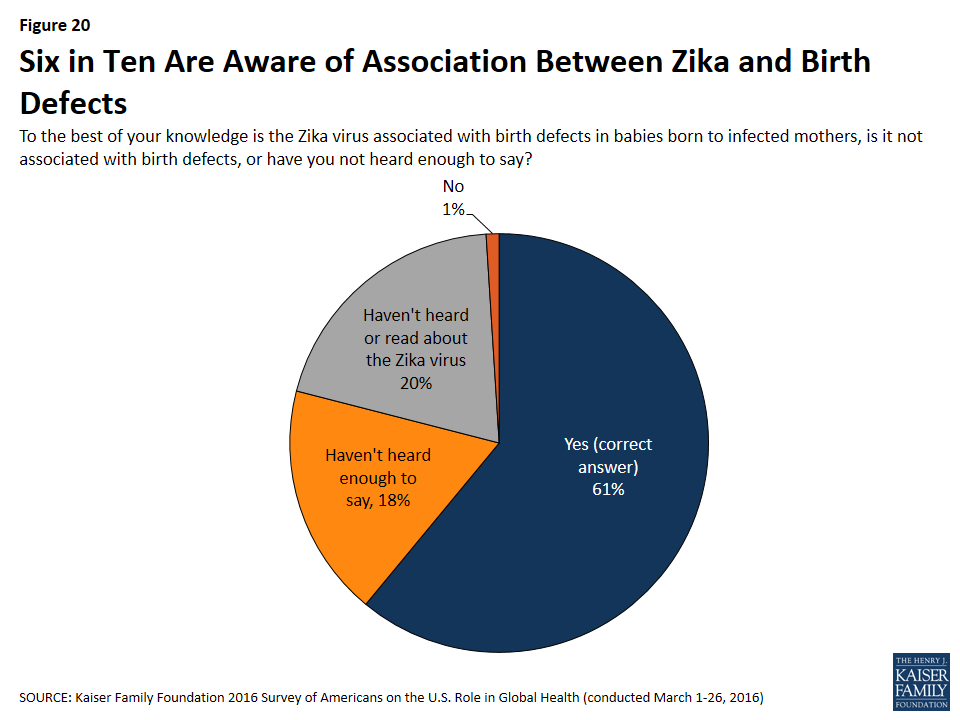

Six in ten Americans know about the connection between the Zika virus and birth defects in children born to infected mothers. This connection was confirmed by the CDC on April 13th, 2016.3

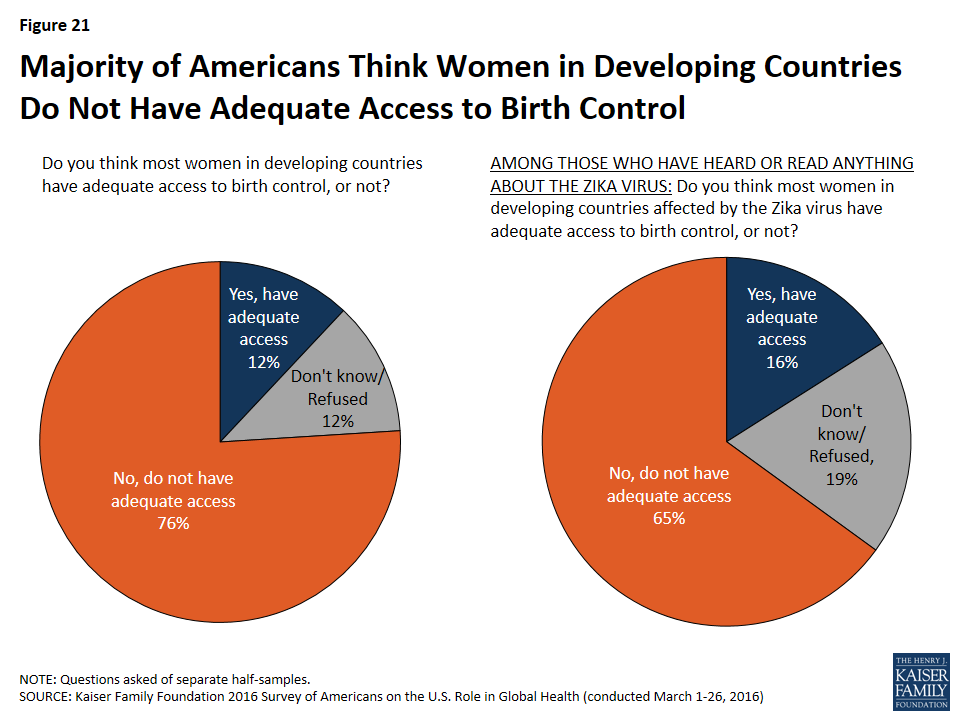

Given this link, concerns have been raised about women’s access to contraception in Zika-affected areas4 . Three-fourths (76 percent) of Americans say that most women in developing countries do not have adequate access to birth control while just 12 percent believe these women have adequate access and another 12 percent are unsure. When asked specifically about developing countries affected by the Zika virus, results are somewhat similar. Most (65 percent) of those who have heard or read about the Zika virus say women in developing countries affected by the virus do not have adequate access to birth control, while 16 percent believe they do have adequate access and 18 percent are unsure.

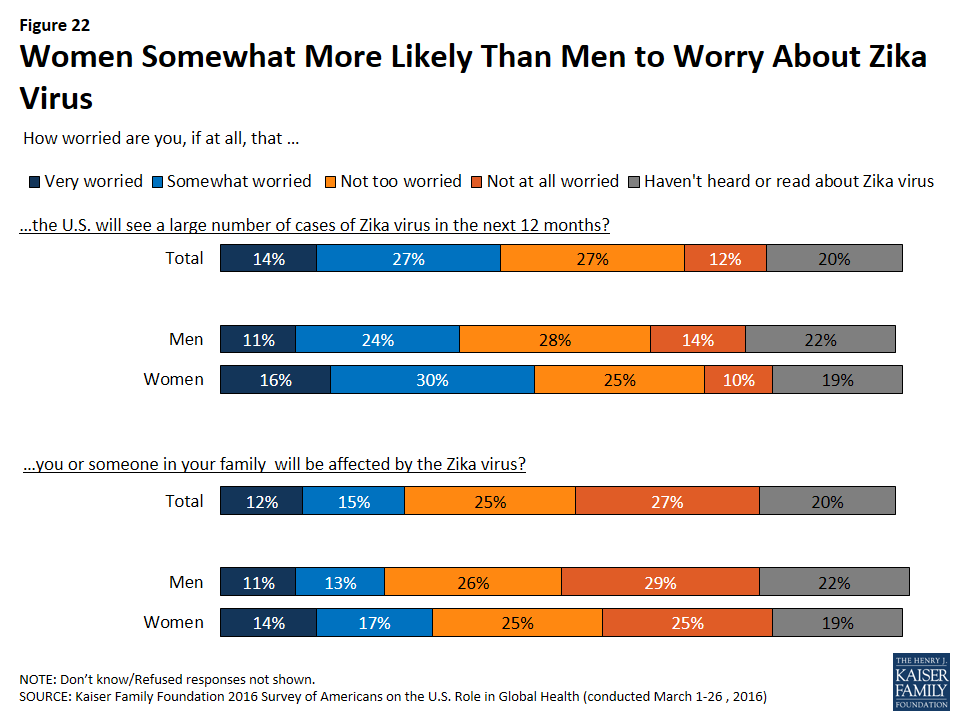

Women are somewhat more likely than men to know about the connection between the Zika virus and birth defects in babies born to infected mothers. Sixty-four percent of women report knowing about this connection compared to 57 percent of men. In addition, women are more likely than men to worry that they or someone in their family will be affected by the Zika virus and to worry that the U.S. will see a large number of cases of the Zika virus in the next 12 months. Nearly half of women (46 percent) are “very” or “somewhat” worried that the U.S. will see a large number of Zika cases, compared to 35 percent of men. Three in ten women (31 percent) are worried that they or someone in their family will be affected by the Zika virus, compared to 23 percent of men.

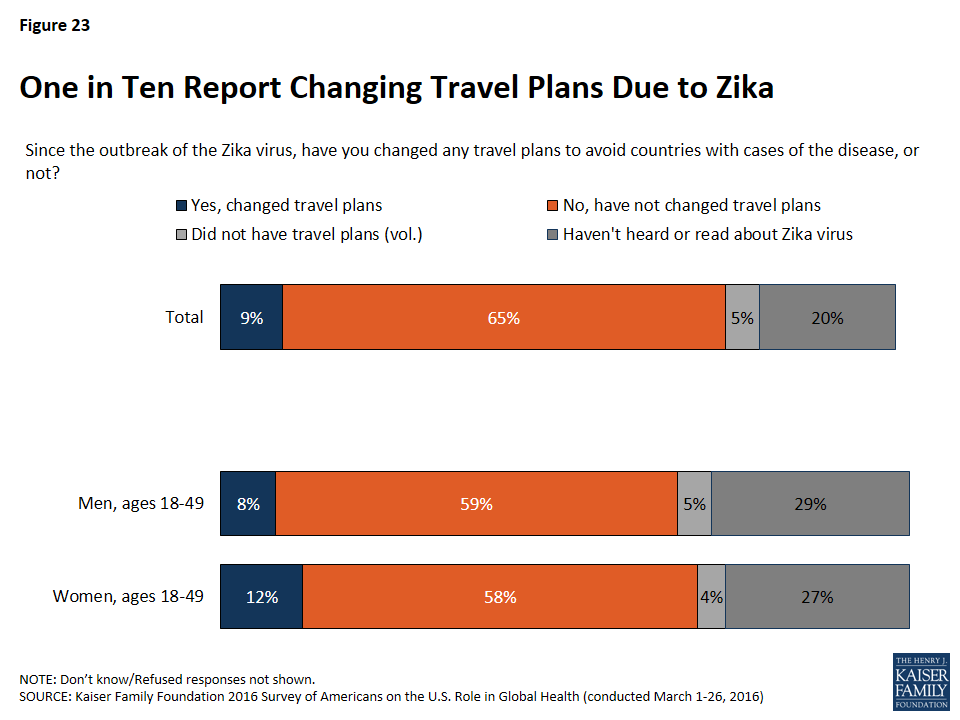

Despite this, fewer than one in ten Americans (9 percent) report they have changed their travel plans to avoid countries affected by Zika, including 12 percent of women of reproductive age (those between the ages of 18 and 49).

Attitudes Towards U.S. Efforts to Fight the Zika Virus

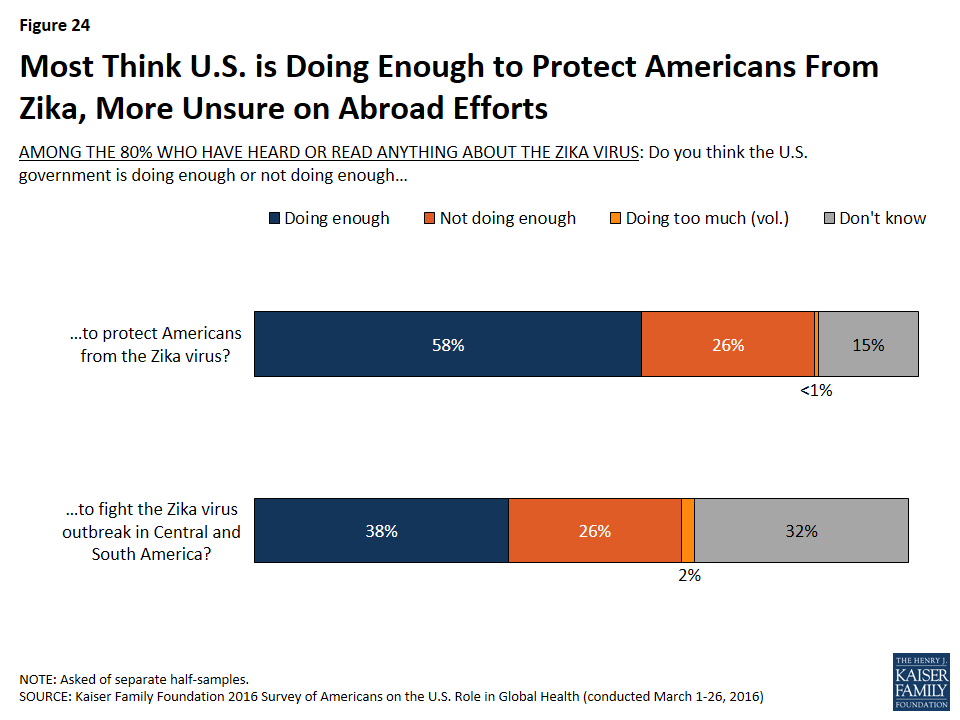

Among those who have heard or read anything about the Zika virus, a majority give mostly positive ratings to government efforts to combat Zika in the United States, though many are unsure about U.S. efforts in Central and South America. Six in ten (58 percent) say the U.S. is doing enough to protect Americans from the virus, while one in four (26 percent) say the U.S. is not doing enough and another 15 percent say they don’t know enough to say. Comparatively, four in ten (38 percent) say the U.S. is doing enough to fight the Zika virus in Central and South America, while 26 percent say the U.S. is not doing enough and almost a third (32 percent) say they don’t know enough to say. Two percent volunteer that the U.S. is doing too much in this area or should not be involved.

Attitudes are also split on whether the U.S. is doing enough to help women in developing countries who may be at risk for the Zika virus make family planning and preventive health decisions. One-third (34 percent) of Americans who have heard or read anything about Zika, say the U.S. government is not doing enough, which is roughly equal to the share who say it is doing enough (33 percent). Democrats are more likely to say the U.S. government is not doing enough (45 percent), compared to 33 percent of independents and 19 percent of Republicans.

| Table 4: U.S. Government Doing Enough to Help Women in Developing Countries At Risk for Zika | ||||

| Among those who have heard/read anything about Zika | ||||

| Do you think the U.S. government is doing enough or not doing enough to help women in Central and South America who may be at risk for the Zika virus make family planning and preventive health decisions? | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| Doing enough | 33% | 27% | 31% | 43% |

| Not doing enough | 34 | 45 | 33 | 19 |

| Doing too much/Should not be involved (vol.) | 2 | <1 | 3 | 4 |

| Don’t know | 30 | 27 | 33 | 33 |

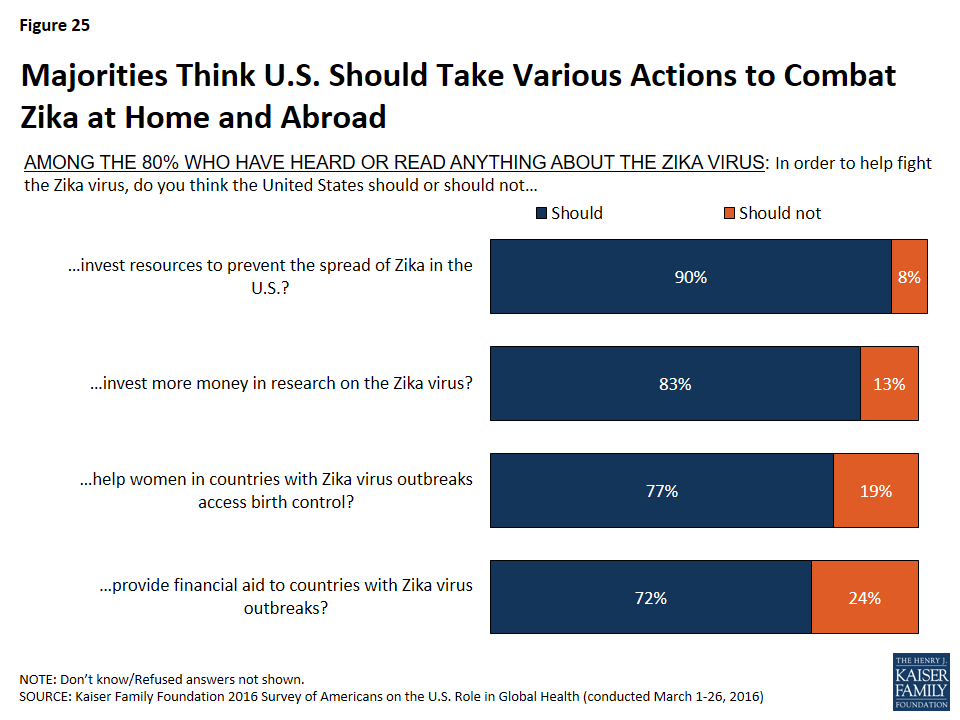

When asked whether the U.S. should or should not take several actions in response to the Zika virus, nine in ten of those who have heard or read anything about Zika say the U.S. should invest resources to prevent the spread of Zika in the U.S. More than eight in ten (83 percent) also say the U.S. should invest more money in research on Zika, while three-fourths want the U.S. to help women in Zika-affected countries access birth control (77 percent), and provide financial aid to Zika-affected countries (72 percent).

Methodology

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2016 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted March 1-26 2016, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,508 adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (606) and cell phone (902, including 549 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by Princeton Data Source under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Both the random digit dial landline and cell phone samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the person who answered the phone. The survey fieldwork was funded through a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2014 American Community Survey (ACS) on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, nativity (for Hispanics only), and region along with data from the 2010 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the January-June 2015 National Health Interview Survey. The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margin of sampling errors for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 1508 | ±3 percentage points |

| Party Identification | ||

| Democrats | 488 | ±5 percentage points |

| Republicans | 359 | ±6 percentage points |

| Independents | 478 | ±5 percentage points |

Endnotes

- B DiJulio, M Norton, and M Brodie, Americans’ Views on the U.S. Role in Global Health, Kaiser Family Foundation, January 20, 2016. https://modern.kff.org/global-health-policy/poll-finding/americans-views-on-the-u-s-role-in-global-health/ ↩︎

- World Health Organization, February 1, 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2016/emergency-committee-zika-microcephaly/en/ ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April 13, 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/s0413-zika-microcephaly.html ↩︎

- J Kates, J Michaud, and A Valentine, Zika Virus: The Challenge for Women, Kaiser Family Foundation, February 1, 2016. https://modern.kff.org/global-health-policy/perspective/zika-virus-the-challenge-for-women/ ↩︎