Key State Policy Choices About Medical Frailty Determinations for Medicaid Expansion Adults

Executive Summary

Since 2006, states have had to determine “medical frailty” for Medicaid enrollees if states choose to design an “alternative benefit plan” (ABP, previously called a benchmark benefit package) that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package. To date, there are 12 states that must determine medical frailty because they offer an ABP for Medicaid expansion adults. The medical frailty determination is intended to protect coverage for enrollees who have physical and/or mental health needs but do not qualify for Medicaid based on a disability. Medical frailty determinations are assuming greater importance in recent years as more states adopt restrictive Section 1115 waiver policies, such as premiums or work requirements. CMS has required many, but not all, of these states to identify and exempt enrollees who are medically frail from restrictions on coverage and benefits under these waivers. This issue brief answers three key questions about medical frailty determinations and presents new data on the rules and processes used by the 12 states making these determinations for Medicaid expansion adults. The findings are based on a 50-state survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured in fall 2018. Tables contain state-level data for the 12 states.

Key findings include the following:

- A dozen states, or about one-third of Medicaid expansion states, must identify enrollees who are medically frail because these states provide a benefit package to expansion adults that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package. The medical frailty process is intended to ensure that these enrollees receive the benefit package that best meets their needs. Key areas that may differ include home and community-based services, behavioral health, and preventive services.

- Medical frailty determinations are assuming even greater importance for enrollees’ ability to retain the coverage and scope of benefits for which they are eligible, as some states implement Section 1115 waivers that impose restrictions on eligibility and benefits. Currently, six states must determine medical frailty to exempt these enrollees from restrictive waiver policies such as work requirements and premiums.

- The complexity of the administrative process for determining medical frailty can affect enrollees’ ability to retain access to the benefit package and coverage for which they are eligible. Policy developments in this area will be important to watch, as Medicaid expansion and implementation of restrictive policies in Section 1115 waivers continues.

Issue Brief

Introduction

Since 2006, states have had to determine “medical frailty” for Medicaid enrollees if states choose to design an “alternative benefit plan” (ABP) that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package. To date, there are 12 states that must determine medical frailty because they offer an ABP for Medicaid expansion adults. The medical frailty determination is intended to protect coverage for enrollees who have physical and/or mental health needs but do not qualify for Medicaid based on a disability. Federal law provides that Medicaid enrollees who are medically frail or otherwise have special medical needs must have access to the traditional state plan benefit package. Federal regulations set out the general criteria that define medical frailty (Box 1). States have flexibility to further define the specific criteria and establish the process by which medical frailty is determined, with resulting variation among states.

Medical frailty determinations are assuming greater importance in recent years as more states adopt restrictive Section 1115 waiver policies, such as premiums or work requirements. Many of these waivers apply restrictive policies to – and require medical frailty determinations for – Medicaid expansion adults, although Indiana’s waiver includes traditional low-income parents as well as expansion adults. CMS has required many, but not all, states with waivers imposing restrictions on coverage and benefits to identify and exempt enrollees who are medically frail. For example, unlike the other states discussed in this brief, Utah and Wisconsin’s waiver approvals require those states to exempt enrollees with disabilities but do not require medical frailty determinations.

This issue brief answers three key questions about medical frailty determinations and presents new data on the rules and processes used by the 12 states making these determinations for Medicaid expansion adults. All 12 states offer a benefit package to expansion adults that differs from the state plan benefit package. Additionally, six of these states have waivers that impose other restrictions on non-medically frail expansion adults. The findings are excerpted from a survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia about Medicaid eligibility for seniors and people with disabilities conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured in fall 2018.1 Tables contain data for the 12 states.

Box 1: Federal Medical Frailty Criteria for Adults2

Federal rules require that medically frail adults include at least individuals with:

- Disabling mental disorders, including serious mental illness;

- Chronic substance use disorders;

- Serious and complex medical conditions;

- Physical, intellectual or developmental disabilities that significantly impair the ability to perform one or more activities of daily living; or

- A disability determination based on Social Security Administration criteria.

Key Questions

1. What is Medical Frailty and What are the Federal Rules?Since 2006, states have had the option to design an “alternative benefit plan” (ABP) for certain Medicaid populations that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package.3 An ABP is a set of covered services that is either (1) based on one of three types of commercial insurance plans or their actuarial equivalent (known as the ABP benchmark) or (2) determined appropriate by the Health and Human Services Secretary. States can design ABPs targeted to different subpopulations, such as beneficiaries in different geographic areas or beneficiaries with particular medical needs.

Few states elected the ABP option prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but ABPs became more widespread after the ACA required states to provide an ABP to Medicaid expansion adults. Expansion adult ABPs must include certain services (Box 2).4 However, an expansion adult ABP may not include all of the services in the traditional state plan benefit package,5 unless the state intentionally designs the ABP to align with the state plan benefit package.6 States can choose to design an expansion adult ABP that contains the same benefits as the state plan benefit package by using “Secretary-approved coverage” as the ABP benchmark. “Secretary-approved coverage” encompasses any Medicaid state plan benefit, including home and community-based services (HCBS).7 To fully align the benefits in an ABP with those in the Medicaid state plan benefit package, states must determine which state plan benefits must be added to the ABP and which ABP benefits must be added to the state plan benefit package.

Box 2: Benefits That the Medicaid Expansion Adult ABP Must Include:

- The ACA’s 10 categories of essential health benefits;8

- Any other benefits in the ABP benchmark plan;

- Early Periodic Screening Diagnostic & Treatment services for enrollees up to age 21;9

- Family planning services and supplies;10

- Federally qualified health center and rural health center services;11

- Emergency and non-emergency transportation;12 and

- Parity in physical and behavioral health services.13

If states do not choose to align their expansion adult ABP with the state plan benefit package, there are certain key areas that may differ, and these differences may be important to enrollees with physical or mental health needs (Box 3). The ABP may be less likely to include home and community-based services (HCBS), such as personal care services, because ABPs usually are based on commercial insurance plans, which typically provide less coverage of HCBS than what is available through the Medicaid state plan benefit package.14 On the other hand, the state plan benefit package may not include behavioral health and/or preventive services to the same extent as the expansion adult ABP because those benefits are optional in the state plan benefit package, while ABPs are subject to mental health parity and essential health benefit requirements to cover such services.15

Box 3: Key Benefits That May Differ If State Does Not Align the Expansion Adult ABP with the State Plan Benefit Package:

- Home and community-based services, such as personal care

- Behavioral health services, including mental health and substance use disorder treatment

- Preventive services

The medical frailty process is intended to ensure that enrollees receive the benefit package that best meets their needs if the state does not align the expansion adult ABP with the state plan benefit package. Certain people, including those who are “medically frail,” cannot be required to enroll in an ABP and instead must have access to the state plan benefit package, even if they are eligible for Medicaid through the ACA expansion group.16 If states choose to align their expansion adult ABP with their state plan benefit package, they do not need to identify medically frail enrollees. States that have opted to align their expansion adult ABP with their state plan benefit package have noted that doing so minimizes disruptions in coverage for enrollees who move between Medicaid eligibility groups.17 In addition, administering a single set of covered services for all populations may be administratively simpler.

States also must identify enrollees who are medically frail if the state has a Section 1115 waiver that imposes eligibility or benefit restrictions on enrollees. The increase in these restrictive waiver policies has meant that medical frailty determinations are assuming even greater importance for enrollees’ ability to retain the coverage and scope of benefits for which they are eligible. The types of restrictions imposed under waivers from which medically frail enrollees are exempt include premiums, work and reporting requirements, limits on or elimination of non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), mandatory enrollment in Marketplace premium assistance, required completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behavior activity, and a three-month coverage lock-out for failure to timely renew eligibility.

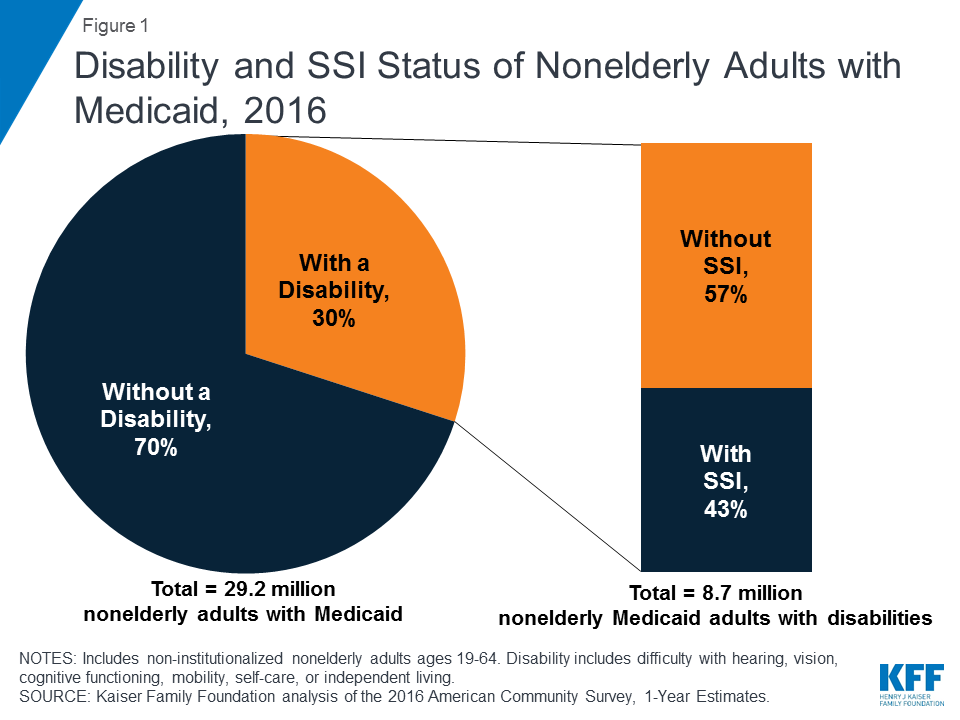

The medical frailty process accounts for the fact that the ACA expansion group includes some people with disabilities. Non-elderly adults with disabilities can qualify for Medicaid in the ACA expansion group, based solely on their low income, in states that have adopted the expansion.18 Three in 10 nonelderly adults with Medicaid report having a disability, according to data from the American Community Survey (ACS) (Figure 1). The ACS and other federal survey data classify a person as having a disability if they have a functional limitation that results in a participation limitation. This includes people who report serious difficulty with hearing, vision, cognitive functioning (concentrating, remembering, or making decisions), mobility (walking or climbing stairs), self-care (dressing or bathing), or independent living (doing errands, such as visiting a doctor’s office or shopping, alone).19

Notably, over half of nonelderly Medicaid adults with disabilities do not receive federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, despite reporting serious difficulty in at least one ACS functional area (Figure 1). While receiving SSI benefits is a pathway to Medicaid eligibility for some people with disabilities, the SSI disability standard is more stringent than the ACS definition.20 In addition, SSI financial eligibility criteria are more restrictive than those for Medicaid expansion adults and other disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways.21 As a result, people with disabilities who do not receive SSI can be eligible for Medicaid as expansion adults or low-income parents22 or through an optional disability-related pathway.23 People who are eligible for Medicaid based on their status as an SSI beneficiary are excluded from coverage in the ACA expansion group.

2. Which States Must Identify Medically Frail Enrollees and What are the Implications?

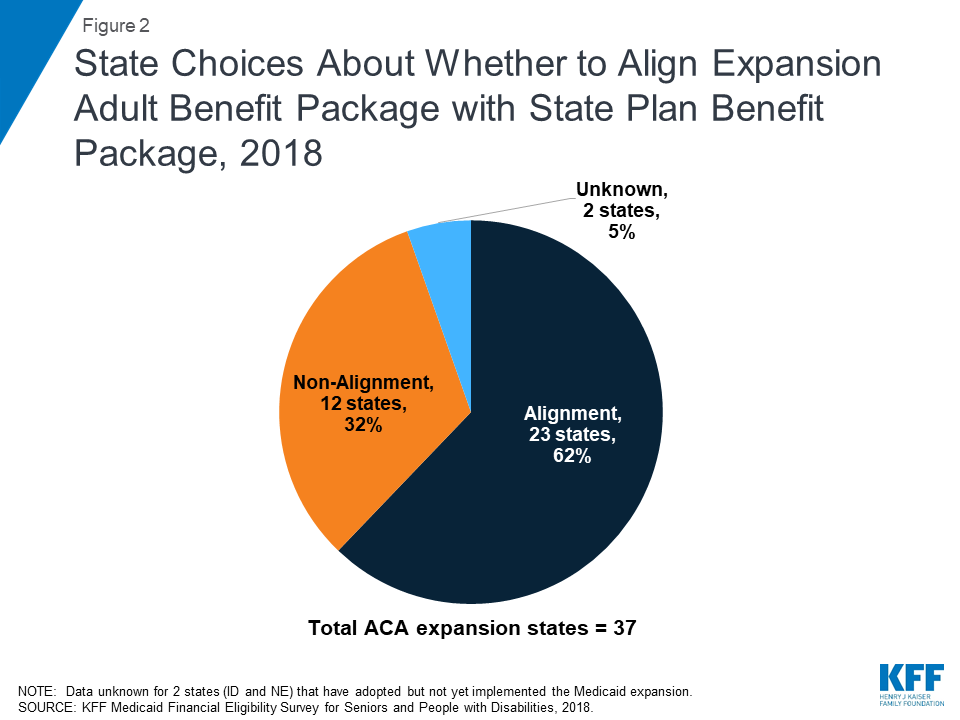

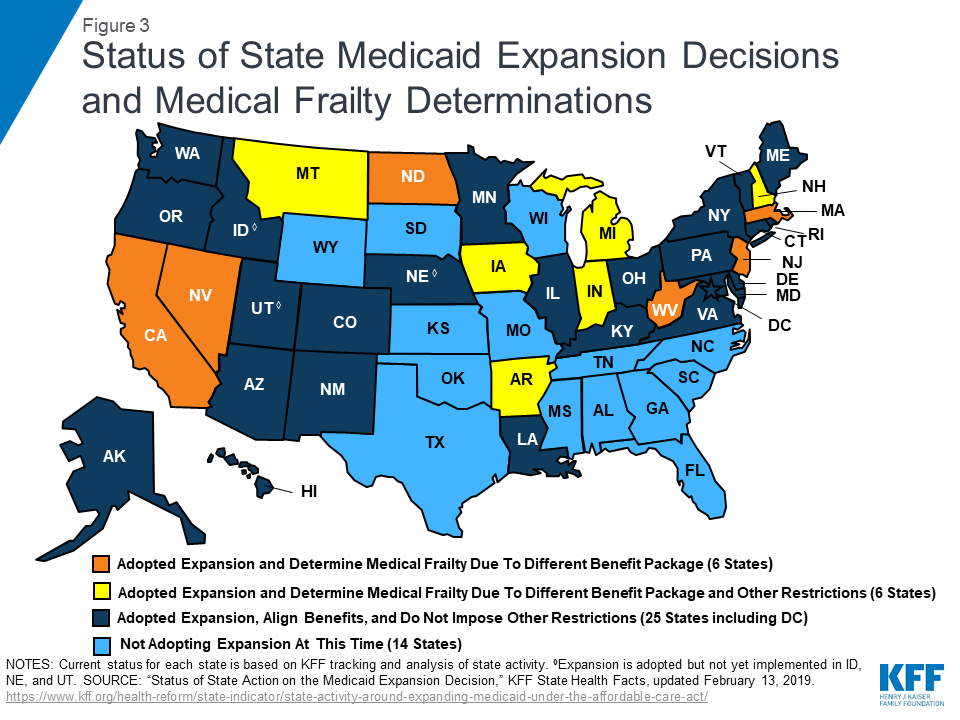

A dozen states, or about one-third of Medicaid expansion states, must identify enrollees who are medically frail because these states provide a benefit package to expansion adults that differs from the traditional state plan benefit package (Figure 2).24 As noted above, enrollees who are medically frail cannot be required to receive the expansion adult ABP and instead must have access to the state plan benefit package if they choose. The 12 states that report making medical frailty determinations because their expansion adult ABP is not aligned with their state plan benefit package include Arkansas, California, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, and West Virginia (Figure 3).

In addition to providing a different benefit package to expansion adults, six states impose other eligibility or benefit restrictions on Section 1115 waiver enrollees that require these states to identify and exempt medically frail individuals. These states include Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, and New Hampshire (Figure 3).25 Medically frail enrollees are exempt from Section 1115 waiver provisions that impose premiums in four states (IN, IA, MI, MT) and work and reporting requirements in three states (IN, MI, and NH). They also are exempt from restrictions on NEMT in two states (AR26 and IN27 ), mandatory enrollment in Marketplace premium assistance in Arkansas, required completion of a health risk assessment and healthy behavior activity in Michigan, and a three-month coverage lockout for failure to timely renew eligibility in Indiana.28

States with restrictive waivers, where medical frailty determines exemptions from conditions on coverage such as work requirements and premiums, report higher shares of medically frail enrollees than states where medical frailty only determines benefit package contents. Indiana reported the highest share of expansion adults (24%) identified as medically frail in 2018, among the 7 of 12 states able to report this data (Table 1).29 In Indiana, health plans identify individuals as potentially medically frail and then make a determination using a standardized assessment tool. Eight percent of expansion adults were identified as medically frail in Arkansas and Montana. Other data show that an increasing share of Arkansas enrollees who were subject to work and reporting requirements were identified as medically frail, and therefore exempt from complying, as the requirements were implemented in 2018. In these states, medical frailty determines exemptions from coverage restrictions, including work requirements and NEMT restrictions in Indiana and Arkansas, premiums in Indiana and Montana, and mandatory Marketplace premium assistance in Arkansas (Table 1).

Other states reported much smaller shares of medically frail expansion adults, ranging from 3% in Iowa to less than 1% in New Jersey and North Dakota (Table 1). In most states reporting very low shares of medically frail enrollees, medical frailty is limited to determining benefit package contents (MA, NJ, and ND). Various factors may account for differing shares of medically frail adults among states, including enrollee knowledge and ease of navigating the process, whether multiple or few entities can identify medically frail enrollees, the type of verification required, and whether states apply relatively broad or restrictive criteria in the context of the general federal rules.

| Table 1: Share of Expansion Adults Identified as Medically Frail and Implications, 2018 | ||

| State | Share of Expansion Adults Identified as Medically Frail | Implications of Medical Frailty Determination |

| Expansion States with Section 1115 Waivers Restricting Eligibility and/or Benefits | ||

| Arkansas | 8% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, NEMT restrictions, and mandatory Marketplace premium assistance. |

| Indiana | 24% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, NEMT restrictions, and premiums. |

| Iowa | 3% | Determines benefit package contents as well as exemption from premiums. |

| Michigan | NR | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements, premiums, and mandatory health risk assessment and healthy behavior activities. |

| Montana | 8% | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemption from premiums. |

| New Hampshire | NR | Determines benefit package contents, as well as exemptions from work requirements. |

| Expansion States without Section 1115 Waivers Restricting Eligibility and/or Benefits | ||

| California | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| Massachusetts | 1.40% | Determines benefit package contents. |

| Nevada | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| New Jersey | 0.30% 1 | Determines benefit package contents. |

| North Dakota | 0.02% | Determines benefit package contents. |

| West Virginia | NR | Determines benefit package contents. |

| NOTES: NR = No response. NEMT = non-emergency medical transportation. 1 New Jersey reported 1,698 people identified as medically frail. KFF analysis of Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System (MBES) data determined expansion adult population in FY2017 as 580,200 adults.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility Survey for Seniors and People with Disabilities, 2018. | ||

3. How Do States Administer the Medical Frailty Process?

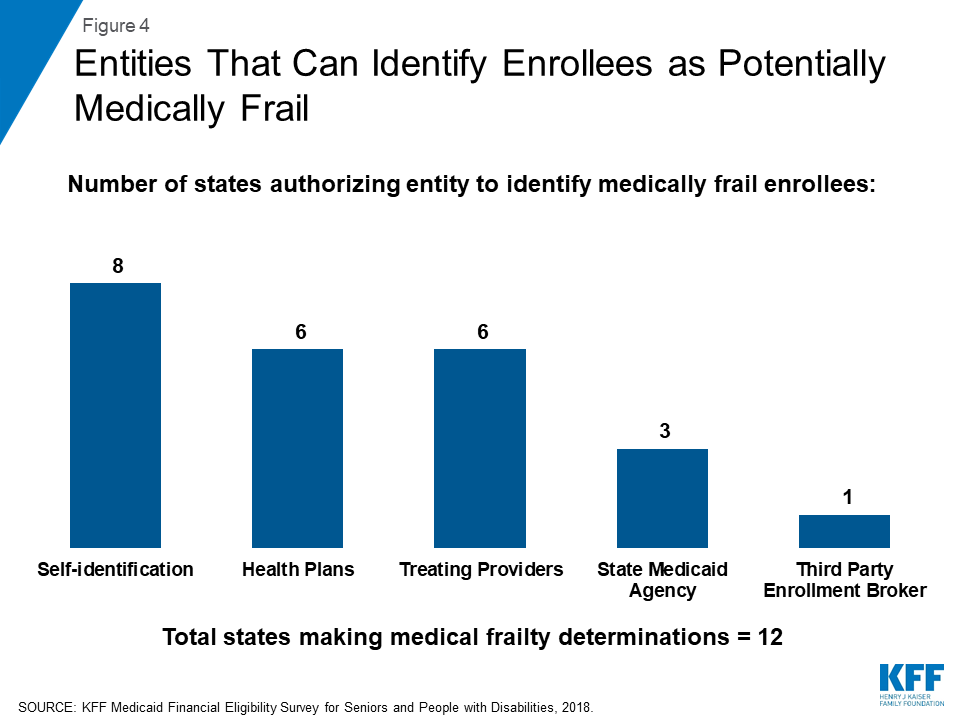

In a minority of states with medical frailty determinations, the Medicaid enrollee cannot initiate the medical frailty process (Appendix Table). These states include California, Indiana, Nevada, and New Jersey. Most states do allow the enrollee to self-identify as potentially medically frail (Figure 4). Other entities that states allow to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail include health plans, treating providers, the state Medicaid agency, and a third party enrollment broker.

Half of the states that determine medical frailty authorize just one entity to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail, which could lead to gaps in identifying eligible enrollees (Appendix Table). Four states (AR, MA, NH, and WV) allow self-identification as the only way to initiate the medical frailty determination. Self-identification is a person-centered approach but also requires that individuals know what the medical frailty designation means and how to navigate the process in order for self-identification to be a successful means of identifying eligible individuals. Navigating the process may be particularly challenging for certain enrollees. In an early look at implementation of Arkansas’ work and reporting requirements, some interviewees expressed concern about enrollees’ ability to understand that they potentially might qualify for a medical frailty exemption and to successfully navigate that process, especially for those with mental health needs. Indiana and New Jersey authorize health plans as the sole entity to initiate a medical frailty determination. Basing determinations exclusively on claims data could result in delayed identification of people who are newly enrolling in coverage or for whom there is no claims history, such as mental health or substance uses disorder services. By contrast, three states (MI, MT, and ND) allow multiple entities to initiate the medical frailty determination. Allowing multiple entities to identify enrollees as potentially medically frail may help ensure that eligible enrollees are identified.

Most states allow medically frail enrollees to be identified at multiple points, including at the time of application, at renewal, and during the eligibility period (Appendix Table). Allowing the medical frailty determination to occur at more than one time is another policy that may help ensure that all eligible individuals are identified.

Half of the states determine medical frailty based on a specific diagnosis as well as functional need criteria.30 These states include California, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, and North Dakota. By contrast, Arkansas and New Jersey only use functional need criteria. Montana and West Virginia do not require a specific diagnosis but instead base medical frailty determinations on the existence of any physical, mental, or emotional health condition that limits activities (MI) or that results in the need for assistance (WV). West Virginia also considers chronic substance abuse or developmental conditions when determining medical frailty. Massachusetts adopts the federal medical frailty criteria described in Box 1 above.31 Four states (AR, IN, NJ, and ND) use a standardized assessment tool to determine medical frailty. Standardized tools can help ensure that individuals with similar conditions are treated similarly but must be broad enough to include all enrollees who should qualify without arbitrary exclusions.

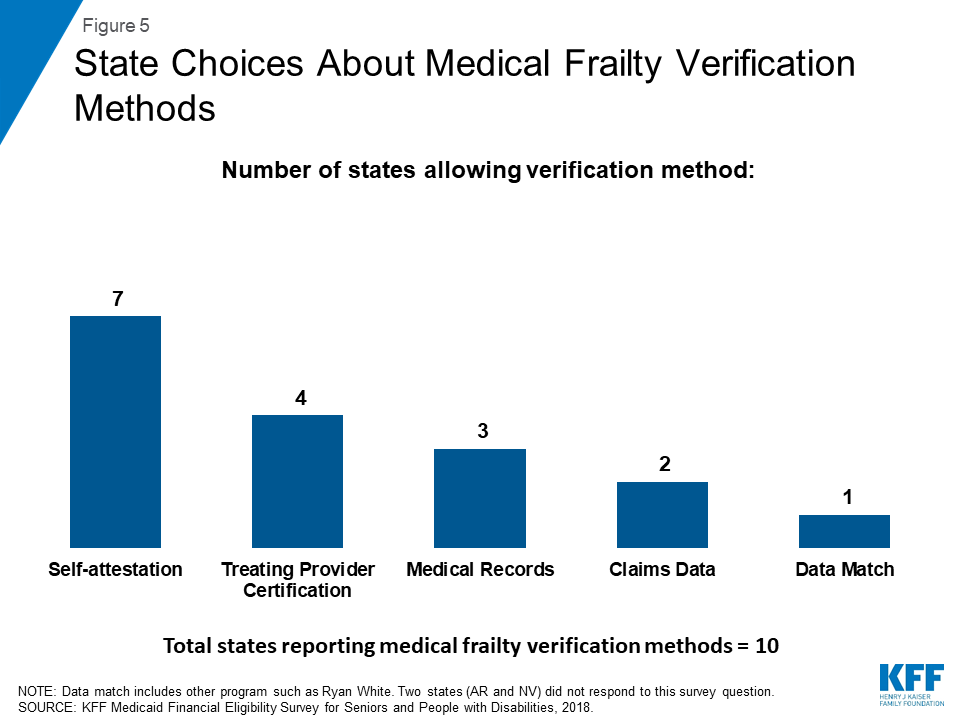

Over half of the states32 allow individuals to self-attest that they meet medical frailty criteria, instead of requiring documentation or other verification (Figure 5 and Appendix Table). Other sources of verification include treating provider certification, medical records, claims data, and data match with another program such as Ryan White. An existing body of research shows that additional reporting or administrative burdens can create barriers to eligible people retaining coverage. Half of the states provide for just one verification method, while the other six states allow more than one method.

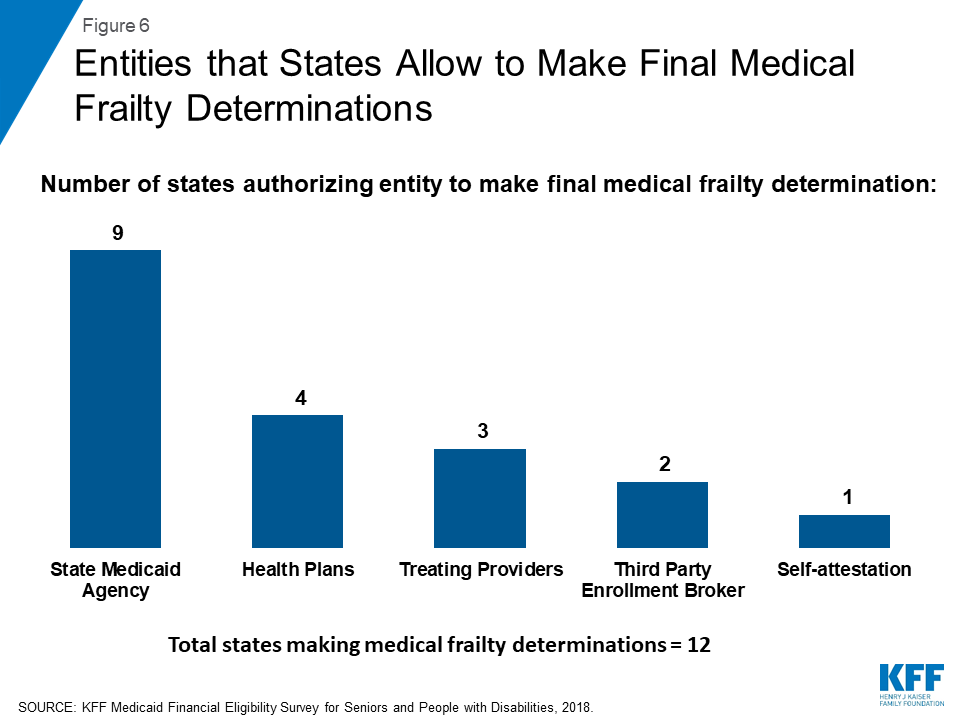

The state Medicaid agency makes the final medical frailty determination in most states (Figure 6 and Appendix Table). Other entities that states allow to make final medical frailty determinations are health plans, treating providers, and third party enrollment brokers. Individuals whose medical frailty status is denied or terminated can appeal that decision by requesting a state fair hearing in most states. In Indiana, an enrollee’s initial appeal of a medical frailty determination goes through the health plan appeals process before proceeding to a state fair hearing. Two states (NH and WV) report that a formal appeals process is not applicable because they accept enrollee self-attestation to establish medical frailty.33

Half of the states require medical frailty status to be renewed annually. These states include Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, and New Jersey. It is important that enrollees know about and are able to successfully navigate the medical frailty renewal process so that eligible individuals remain connected to coverage and the appropriate benefit package. The other six states review medical frailty status based on service need or a change in circumstances.

Looking Ahead

State rules and processes vary among states, and the complexity of the process can affect the extent to which Medicaid enrollees are appropriately identified as medically frail and therefore retain access to the benefit package and coverage for which they are eligible. The medical frailty process recognizes that not all people with physical and mental health needs are eligible for Medicaid based on a disability and is intended to ensure that these enrollees can access the benefit package that best meets their needs. However, if enrollees do not understand and have difficulty navigating the process, medical frailty determinations will not protect enrollees as intended. Medical frailty determinations are assuming even greater importance with the increase in Section 1115 waivers that place additional restrictions on eligibility and benefits but exempt medically frail enrollees. Policy developments in this area and assessments of whether state medical frailty criteria and procedures are appropriately identifying all eligible individuals will be important areas to continue to watch as Medicaid expansion and state implementation of restrictive waiver policies continues.

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: State Policy Choices About Medical Frailty Determinations for ACA Expansion Adults, 2018 | |||||||||

| State | Who can identify someone as Medically Frail? | Who makes the final Medically Frail Determination? | |||||||

| Self | State | Health Plan | Provider | Enrollment Broker | State | Health Plan | Provider | Enrollment Broker | |

| TOTAL | 8 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Arkansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| California | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Indiana* | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Massachusetts | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Michigan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Montana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| New Hampshire | ✓ | ||||||||

| New Jersey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| West Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| NOTES: NR = No response. *Indiana’s Section 1115 waiver also requires it to determine medical frailty for traditional low-income parents in addition to ACA expansion adults. | |||||||||

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility Survey for Seniors and People with Disabilities, 2018. | |||||||||

| (continued below) | |||||||||

| Appendix Table 1 (continued): State Policy Choices About Medical Frailty Determinations for ACA Expansion Adults, 2018 | ||||||||

| State | When is Medical Frailty Determined? | How is Medically Frail Status Verified? | ||||||

| Application | Renewal | During Eligibility Period | Claims data | Data Match | Self-Attestation | Provider Certification | Medical Records | |

| TOTAL | 11 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Arkansas | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| California | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Indiana* | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Iowa | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Massachusetts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Michigan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Montana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Nevada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | NR | ||||

| New Hampshire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| New Jersey | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| North Dakota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| West Virginia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| NOTES: NR = No response. *Indiana’s Section 1115 waiver also requires it to determine medical frailty for traditional low-income parents in addition to ACA expansion adults. | ||||||||

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility Survey for Seniors and People with Disabilities, 2018. | ||||||||

Endnotes

- For other survey findings, including state-level data on Medicaid financial eligibility criteria and adoption of key age and disability-related pathways, options to expand financial eligibility for Medicaid long-term services and supports, Medicaid assistance with out-of-pocket costs for low-income Medicare beneficiaries, state choices about whether to adopt optional age and disability-related pathways in light of states’ ACA expansion status, and state adoption of optional streamlined eligibility renewal procedures, see Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities: Findings from a 50-State Survey (June 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-financial-eligibility-for-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/. ↩︎

- Medically frail children must include those under 19 who are eligible for SSI, eligible under the Katie Becket option, in foster care or another out-of-home placement, receiving foster care or adoption assistance, or receiving services through a family-centered, community-based, coordinated care system receiving maternal and child health funds and those with serious emotional disturbances. 42 C.F.R. § 440.315 (f). ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396a (k)(1); 42 C.F.R. § § 440.370, 440.380 (noting that states have the option to provide benchmark coverage to beneficiaries without regard to comparability or statewideness). The statute uses the former terminology, “benchmark benefits.” In its July 2013 final rule, CMS began using the term “ABP.” 78 Fed. Reg. 42160 (July 15, 2013). ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396u-7; 42 C.F.R. § § 440.300-440.390; 45 C.F.R. Part 156. ↩︎

- Most adult Medicaid enrollees receive the state plan benefit package, which includes certain services that all states participating in Medicaid must cover and any optional services that the state chooses to cover. 42 U.S.C. § § 1396a (a)(10); 1396d (a)(1)-(29); 1396n (g), (i), (j), (k); 1396w-4. ↩︎

- The process for doing so is summarized at 78 Fed. Reg. 42238. ↩︎

- State plan HCBS include those available under the § 1915 (i) state plan option, § 1915 (j) self-directed personal assistance services, and § 1915 (k) Community First Choice attendant services and supports. 42 C.F.R. § 440.330 (d). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.345(d). The specific services in each EHB category are determined by those that are included in the commercial insurance plan that the state selects as its EHB benchmark. An EHB benchmark is one of several commercial insurance plans that the state selects and may differ from the state’s ABP benchmark. If the state’s EHB benchmark plan does not include any services within an entire EHB category, the state supplements the ABP by including all of the services in that category from another of the EHB benchmark plan choices. However, if the state’s EHB benchmark plan does not include any habilitative services, the state instead may choose to define the scope of that coverage for the expansion ABP. After the state determines the contents of the 10 EHB categories for its expansion adult ABP, the state then may substitute actuarially equivalent benefits within a single EHB category. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.345 (a). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.345 (b). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.365. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.390. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § § 440.345 (c). ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Benefits and Cost-sharing for People with Disabilities in Medicaid and the Marketplace (Oct. 2014), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/benefits-and-cost-sharing-for-working-people-with-disabilities-in-medicaid-and-the-marketplace/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Adult Behavioral Health Benefits in Medicaid and the Marketplace (June 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/adult-behavioral-health-benefits-in-medicaid-and-the-marketplace/. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.345 (f). Other populations that cannot be required to enroll in an ABP and instead must have access to the full state plan benefit package include people who are blind or have disabilities (regardless of whether they are eligible for SSI); children with disabilities eligible under the Katie Beckett state plan option; people dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid; people who are terminally ill and receiving hospice care; people who live in institutions and receive only a personal needs allowance; people with developmental disabilities and seniors who qualify for nursing facility or equivalent institutional services or home and community-based waiver services; women receiving treatment for breast or cervical cancer; people who qualify for Medicaid based on TB infection; and people who qualify for Medicaid as medically needy based on a spend down. 42 U.S.C. § 1396a (k)(1). Technically, beneficiaries in the adult expansion group who meet an ABP exemption “must be given the option of an Alternative Benefit Plan that includes all benefits available under the approved State plan” instead of being required to receive the ABP that the state has selected for the expansion group. 42 C.F.R. § 440.315. Exempt beneficiaries must have access to the full Medicaid state plan benefit package unless they instead choose to receive the expansion adult ABP. States must inform exempt beneficiaries about how benefits and cost-sharing in the expansion adult ABP compares to the benefits and cost-sharing in the Medicaid state plan and how to enroll in and disenroll from the expansion adult ABP. 42 C.F.R. § 440.320. ↩︎

- See, e.g., AZ SPA #14-006 (April 1, 2014) (noting that providing newly eligible adults with full state plan benefits “will help minimize disruptions for individuals who move among different eligibility categories”); CO SPA #13-0055 (Feb. 10, 2014) (noting that the ABP benchmark plan is the same as the Marketplace benchmark plan and that offering state plan services in the expansion ABP will “ease transitions as clients churn”); OR SPA #13-0019 (Jan. 9, 2014) (noting that the EHB benchmark plans in the ABP and Marketplace are the same and that aligning the ABP with state plan benefits will help minimize disruptions for people who move among benefit packages). ↩︎

- ACA expansion adults are a mandatory coverage group in the statute, although the Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling on the ACA’s constitutionality effectively made adoption of the expansion optional for states. Kaiser Family Foundation, A Guide to the Supreme Court’s Decision on the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion (Aug. 2012), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/a-guide-to-the-supreme-courts-decision/. ↩︎

- U.S. Census Bureau, How Disability Data are Collected from the American Community Survey, (Oct. 17, 2017), https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html. ↩︎

- SSI beneficiaries have an impaired ability to work at a substantial gainful level as a result of old age or significant disability. ↩︎

- The maximum SSI benefit is 74% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $9,252/year for an individual in 2019), and the asset limit for an individual is $2,000. The ACA Medicaid expansion covers individuals up to 138% FPL ($17,236/year for an individual in 2019) without an asset test in states that opt to adopt it. States also have the option to extend financial eligibility for disability-related Medicaid coverage pathways up to 300% of SSI ($27,756/year for an individual in 2019). ↩︎

- People with disabilities may qualify for Medicaid in traditional poverty-related pathways (such as low-income parents or children), although financial eligibility limits for adults in non-expansion states remain low. Under the ACA, all children in families with income up to 138% FPL are eligible for Medicaid regardless of whether they have a disability. However, the median financial eligibility limit for parents in non-expansion states is 40% FPL ($693 per month for a family of 3 in 2018; $711/month for a family of 3 in 2019), and only one non-expansion state (WI) offers any pathway to coverage based solely on low income for childless adults as of January 2019. Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey (March 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2019-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/. ↩︎

- Qualifying for Medicaid based solely on low income as an expansion adult can mean quicker access to coverage, without waiting for a disability determination. States have 90 days to determine Medicaid eligibility in disability-related pathways. Kaiser Family Foundation, The Affordable Care Act’s Impact on Medicaid Eligibility, Enrollment, and Benefits for People with Disabilities (April 2014), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-acts-impact-on-medicaid-eligibility-enrollment-and-benefits-for-people-with-disabilities/. By contrast, real-time eligibility determinations are available in most states for poverty-related pathways. Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey (March 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2019-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/. If someone who qualifies through the ACA expansion group is later also determined to be eligible through a disability-related pathway, the person can choose whether to remain in the expansion group or switch to the disability-related group. 42 C.F.R. § 435.911 (c) (2), (d); see also Kaiser Family Foundation, The Affordable Care Act’s Impact on Medicaid Eligibility, Enrollment, and Benefits for People with Disabilities (April 2014), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-affordable-care-acts-impact-on-medicaid-eligibility-enrollment-and-benefits-for-people-with-disabilities/. ↩︎

- Five states (ID, KY, NE, UT, and VA) did not respond to these survey questions. Survey results have been supplemented by information from state plan amendments (SPAs), Section 1115 waiver documents, and state legislation to determine that medical frailty determinations currently are not required in these states. Kentucky and Virginia align their expansion adult ABP with the state plan benefit package, making a medical frailty determination unnecessary. Kentucky Medicaid Alternative Benefit Plan, SPA #KY-13-020 (approved Dec. 20, 2013), https://www.medicaid.gov/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/KY/KY-13-020-ABPSPA.pdf; Virginia Medicaid Alternative Benefit Plan, SPA #18-0008 (effective Jan 1, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/VA/VA-18-0008.pdf. Kentucky’s Section 1115 waiver, which placed additional restrictions such as a work requirement and premiums on expansion adults (as well as some traditional adults) has been set aside by a court; if and when that waiver is allowed to be implemented, the waiver calls for Kentucky to exempt medically frail enrollees from those restrictions. See generally Kaiser Family Foundation, Ask KFF: MaryBeth Musumeci Answers 3 Questions on Kentucky, Arkansas Medicaid Work and Reporting Requirements (April 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/ask-kff-marybeth-musumeci-answers-3-questions-on-kentucky-arkansas-medicaid-work-and-reporting-requirement-cases/; Kaiser Family Foundation, Re-approval of Kentucky’s Medicaid Demonstration Waiver (Nov. 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/re-approval-of-kentucky-medicaid-demonstration-waiver/. Virginia has a pending Section 1115 Medicaid waiver application that could require the state to determine medical frailty to exempt individuals from restrictive provisions, such as a work requirement and premiums, if approved by CMS. Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State (April 18, 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/. Utah’s Section 1115 demonstration waiver does not require a determination of medical frailty. For more information about Medicaid expansion in UT, see Kaiser Family Foundation, From Ballot Initiative to Waivers: What is the Status of Medicaid Expansion in Utah? (April 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/from-ballot-initiative-to-waivers-what-is-the-status-of-medicaid-expansion-in-utah/. Idaho and Nebraska have adopted but not yet implemented the Medicaid expansion; state legislation calls for those states to pursue Section 1115 waivers that, if approved by CMS, would impose eligibility restrictions that may require a medical frailty determination. See generally Kaiser Family Foundation, Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision (May 13, 2019). ↩︎

- Two other states (AZ and OH) have approved Section 1115 waivers that will require a medical frailty determination when implemented. In addition, KY’s waiver has restrictions that would require a medical frailty determination, but that waiver has been set aside by a court and has not yet been implemented. AR also has additional waiver provisions that exempt medically frail enrollees but have been set aside by a court. See generally Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State (April 18, 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/. ↩︎

- Medically frail enrollees are exempt from prior authorization requirements. ↩︎

- Medically frail enrollees retain access to NEMT, which is waived for other enrollees. ↩︎

- However, medically frail enrollees are still disenrolled from coverage for failure to timely renew eligibility. ↩︎

- Five states (CA, MI, NV, NH, and WV) were unable to report this data. ↩︎

- NH did not respond to this question as it accepts enrollee self-attestation for medical frailty. ↩︎

- 130 CMR 505.008 (F), https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/01/29/130cmr505.pdf. ↩︎

- Two states (AR and NV) did not respond to this question. ↩︎

- The other two states (AR and MA) did not respond to this question. ↩︎