Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Cost Sharing Policies as of January 2019: Findings from a 50-State Survey

Executive Summary

Key Takeaways

This 17th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) provides data on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2019. See Appendix Tables 1-20 for state data. Over time, Medicaid has evolved from a program with limited eligibility and burdensome enrollment rules that excluded many low-income adults and created barriers to enrollment for eligible individuals to a modernized program that, along with CHIP, provides a broad base of health coverage for the low-income population and more effectively and efficiently connects eligible individuals to coverage. The survey data show:

- Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), most states have expanded Medicaid to low-income adults, helping to fill longstanding gaps in coverage. In the past year, there was an uptick in state activity to expand Medicaid, with five additional states taking steps forward. With this state action, 37 states, including DC, had adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion as of January 2019. Eligibility remains very restricted for adults in the 14 states that have not yet adopted the expansion, with the median eligibility level for parents at 40% FPL ($8,532 per year for a family of three as of 2019) and other adults remaining ineligible regardless of their income in all of these states, except Wisconsin.

- Reflecting ACA policies, all states have implemented more streamlined enrollment and renewal processes, regardless of whether they have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. As of January 2019, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in all states for the first time and most states can complete real-time determinations (within 24 hours) (46 states) and automated renewals (46 states). These modernized, streamlined processes can facilitate individuals’ ability to enroll in and maintain coverage and reduce state administrative burdens.

Looking ahead, one key question is whether there will be continued advances to expand coverage and streamline enrollment or whether emerging policies will erode coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA. The Trump Administration is promoting new Medicaid eligibility requirements through waivers and its proposed budget and has approved a growing number of waiver requests from states, including work requirements, which have never previously been approved for the program. These provisions require complex and costly documentation and administrative efforts that would likely increase barriers to coverage and lead to coverage losses among eligible individuals. Other factors outside of Medicaid may also be contributing to enrollment declines among eligible individuals, including shifting immigration policy.

This 17th annual survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) provides data on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2019. It is based on a telephone survey of state Medicaid and CHIP officials conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families. Appendix Tables 1-20 include state data. The survey data over the past 17 years document how Medicaid has evolved from a program with limited eligibility and burdensome enrollment rules that excluded many low-income adults and created barriers to enrollment for eligible individuals to a modernized program that, with CHIP, provides a broad base of health coverage for the low-income population and more effectively and efficiently connects eligible individuals to coverage. Emerging policies to add Medicaid eligibility requirements could lead to coverage losses and increase the complexity of enrollment processes, eroding coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA.

Eligibility

Prior to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), many poor parents and other adults remained ineligible for Medicaid. Under previous rules, Medicaid eligibility was limited to certain groups of individuals with limited incomes. Eligibility for parents was very restricted and states could not receive federal Medicaid matching funds to cover other non-disabled adults. The ACA helped fill longstanding gaps in coverage by expanding Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) ($29,435 for a family of three or $17,236 for an individual as of 2019) and provided enhanced federal funding to states for expansion coverage.

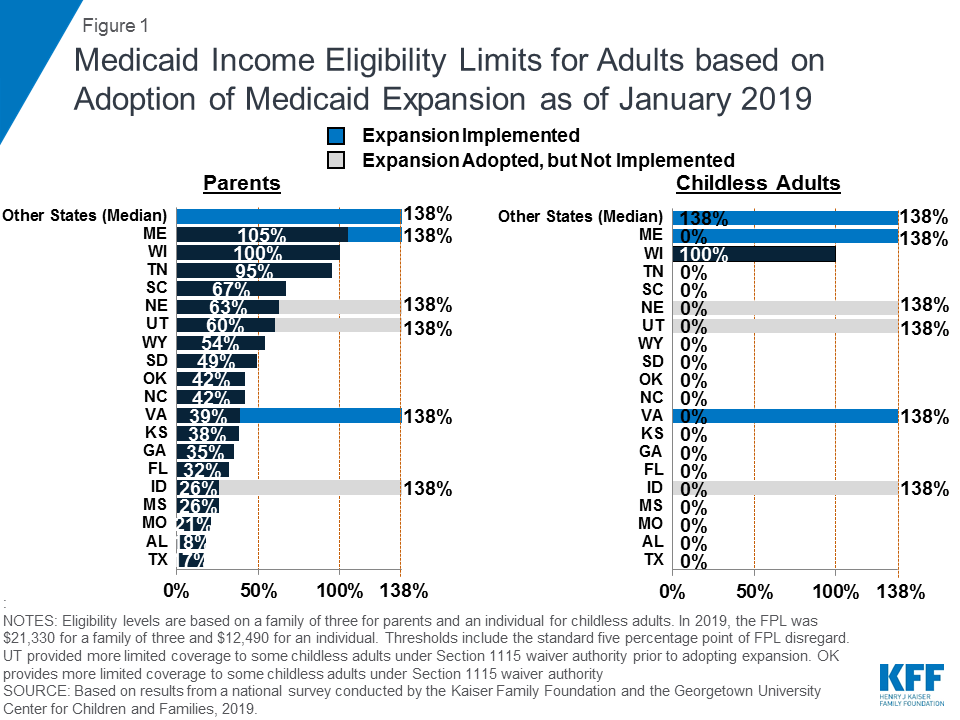

Most states have expanded Medicaid to low-income adults under the ACA, and five additional states took steps forward with expansion in the past year. Virginia and Maine became the latest states to implement the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019, significantly increasing eligibility for parents and other adults (Figure 1). Voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah passed ballot initiatives in 2018 to adopt the expansion, although it had not been implemented as of January 2019, and Utah and Idaho are seeking to add restrictions to the expansion. With this action, 37 states, including DC, had adopted the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019.

In the 14 states that had not yet adopted the Medicaid expansion as of January 2019, eligibility for parents and other adults remains very restrictive. The median eligibility level for parents in these states is 40% FPL ($8,532 per year for a family of three as of 2019) and other adults remain ineligible regardless of their income in all of these states, except Wisconsin. In these states, 2.5 million poor uninsured adults fall into a coverage gap, earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for subsidies to purchase insurance through the Marketplace, which become available at 100% FPL.1

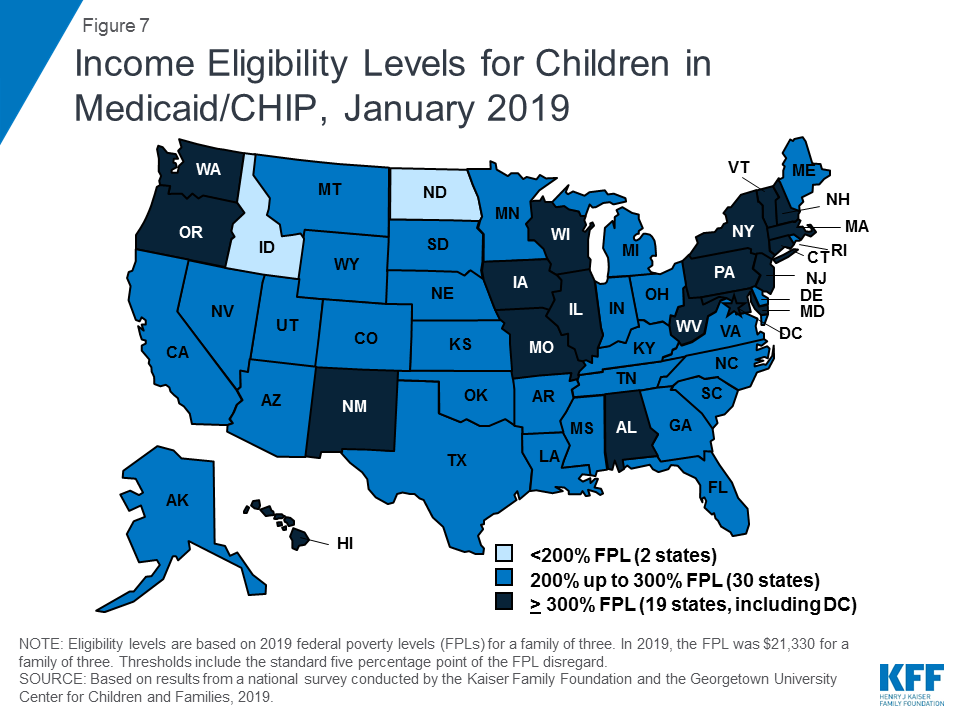

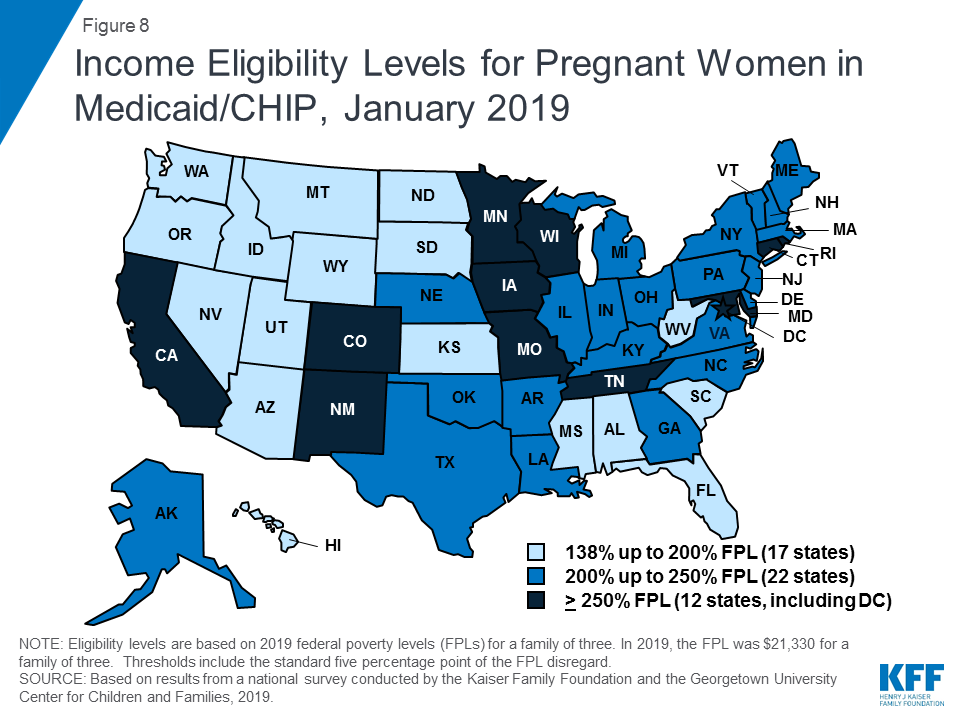

Medicaid and CHIP eligibility for children and pregnant women remains stable and robust. Eligibility levels for children and pregnant women are well above those for parents and other adults in almost all states. As of January 2019, 19 states, including DC, extend eligibility levels for children to 300% FPL or above (Figure 2), and nearly half of states provide eligibility to pregnant women above 200% FPL. The median income eligibility limit is 255% FPL ($54,392 per year for a family of three as of 2019) for children and 200% FPL ($42,660 for a family of three as of 2019) for pregnant women as of January 2019. The stability of children’s coverage reflected Congressional action in 2018 to continue CHIP funding through 2027 and retain the maintenance of effort (MOE) provision that preserves eligibility levels and enrollment procedures for children.

In 2018, additional states obtained Section 1115 waivers to add new eligibility requirements to their Medicaid programs. As of January 2019, 13 states had approved waivers allowing one or more eligibility requirements including conditioning eligibility on meeting a work requirement, adding completion of a health risk assessment as an eligibility requirement, charging premiums or monthly contributions, eliminating retroactive eligibility, delaying coverage until the first premium payment, and/or locking enrollees out of coverage for a period of time if they have unpaid premiums or do not complete timely renewals or report changes in circumstances.2 Many of these provisions require complex and costly administrative efforts that run counter to the streamlined enrollment processes under the ACA and lead to increased barriers to coverage and coverage losses among eligible individuals.

Enrollment and Renewal

Prior to the ACA, many states relied on paper-based, manual enrollment processes with burdensome requirements that could take days and weeks in some states. In addition to expanding Medicaid to adults, the ACA accelerated the adoption of new data-driven enrollment and renewal processes to connect individuals to coverage more quickly and conveniently and reduce the paperwork burden on states and individuals. These changes applied to all states regardless of whether they adopted the Medicaid expansion. The ACA also provided states enhanced federal funding for system upgrades to facilitate these improvements.

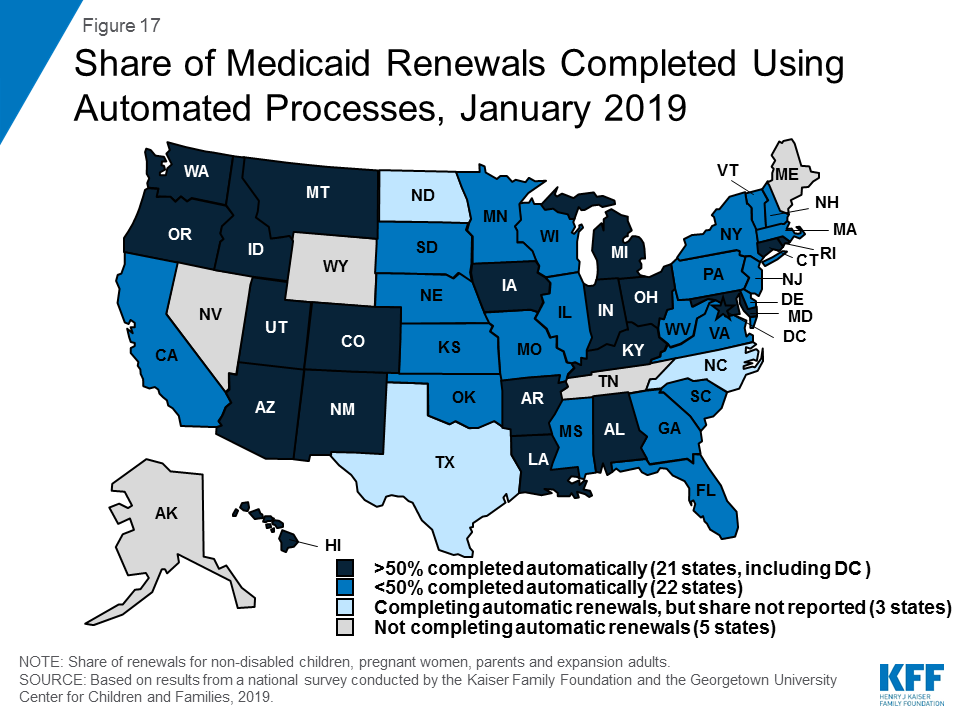

As of January 2019, many states provide a modernized, streamlined enrollment and renewal experience for individuals, reflecting the policies established by the ACA. With Tennessee rolling out a new eligibility system, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in all states for the first time as of January 2019 (Figure 3). Individuals can also apply by phone in the majority of states and, in many states, individuals can use a mobile device to apply or access an online account. Although online applications offer potential benefits to individuals and states, other application pathways, including in-person and mail, remain important, particularly for people with limited computer or internet access. Reflecting increased use of electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria, the majority of states can complete real-time determinations (within 24 hours) (46 states) and automated renewals (46 states), with 16 states making at least half of determinations in real-time and 21 states completing at least half of renewals automatically. Reflecting these broad system and process changes, most states indicated improvements in one or more areas of eligibility operations compared to before the ACA.

Premiums and Cost-Sharing

Federal regulations establish parameters for premiums and cost sharing for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees that reflect their limited ability to pay health care costs. Given their modest incomes, research shows that premiums serve as a barrier to enrollment for low-income families and copayments can limit utilization of needed health care.3

Kentucky and New Mexico eliminated cost sharing for children during 2018; otherwise, premiums and cost sharing for children remained largely stable. This stability, in part, reflects that states generally cannot increase premiums for children under the MOE provision included in the CHIP funding extension through 2027.

Premiums remain limited among parents and other adults, although additional states received waiver approval to impose premiums or monthly contributions on these groups during 2018. Some states have obtained waiver approval to charge premiums or monthly contributions not otherwise allowed under federal rules. As of January 2019, five states (Arkansas, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and Montana) were charging premiums or monthly contributions for parents or other adults. Several additional states have received waiver approval for premiums or monthly contributions for adults, but they were not implemented as of January 2019. Some of these waivers also allow individuals to be locked out of coverage for a period of time if they are disenrolled due to non-payment and to delay coverage until after the first premium is paid. States can charge nominal cost sharing for adults in Medicaid under federal rules, and most states charge cost sharing for parents who were eligible for Medicaid through traditional pathways prior to the ACA and other adults.

Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, one key question is whether there will be continued advances to expand coverage and streamline enrollment processes or whether emerging policy changes will erode coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA.

Additional states may expand Medicaid, which would increase access to coverage for low-income adults and have positive effects on access to and use of care and state budgets and economies.4 However, if states attach waiver provisions such as work requirements or other restrictions to expansion, the positive reach and impact would be limited. Recently, some states have indicated interest in a partial expansion to an income level below 138% FPL with the ACA enhanced federal match rate.5 Relative to full expansion, partial expansions could limit coverage and potentially increase federal costs. While states can pursue waivers to extend coverage to a lower income level without access to the enhanced federal match, no waivers to allow an enhanced match for a partial expansion have been approved to date, and guidance from the previous administration prohibited use of the enhanced match for “partial expansions.”

Renewed CHIP funding protects children’s eligibility levels through 2027, but states that extend eligibility above 300% FPL will have the option to reduce eligibility starting in October 2019. When Congress continued funding for CHIP in 2018, it retained the MOE provision that requires states to preserve Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies for children. However, starting in October 2019, the MOE only applies to children’s coverage up to 300% FPL, meaning that states with eligibility limits above this level could reduce eligibility in the future. This change coincides with the beginning of the phase-out of the temporary 23-percentage point boost in federal CHIP matching rates, leaving states to resume paying a larger share of CHIP costs.

Emerging state and federal policies to add Medicaid eligibility requirements could erode the coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA. The Trump Administration is promoting new Medicaid eligibility requirements through waivers and its proposed budget and has approved a growing number of waiver requests from states, including work requirements, which have never previously been approved for the program. Some states are no longer moving forward with implementing waiver provisions following a change in leadership in the 2018 elections,6 ,7 while other states are considering adding waiver provisions.8 ,9 ,10 ,11 These types of requirements create barriers to coverage and increase administrative burdens and costs for states.12 ,13 As such, they will likely dampen potential coverage gains and lead to coverage losses.

Other policy changes may lead to coverage losses among eligible low-income families and growing administrative burdens on states. In 2017, coverage gains stalled and began to reverse for the first time since implementation of the ACA, and Medicaid enrollment of adults and children declined in 2018.14 ,15 ,16 Some of the decline in Medicaid enrollment could reflect the improving economy. However, some factors may be leading to a drop in enrollment among eligible individuals. While states’ growing use of technology and automation has led to improvements for individuals and states, there are concerns emerging in some states that eligible individuals may be losing coverage due to process-related issues.17 ,18 ,19 Further, other policy changes outside of Medicaid could be dampening enrollment. For example, the Trump administration substantially decreased funding for outreach and enrollment assistance, which is pivotal for helping eligible individuals get and stay enrolled in coverage. In addition, shifting immigration policies, including a proposed rule to make changes to public charge policy, will likely lead to broad decreases in participation in Medicaid among legal immigrant families and their primarily U.S.-born children and increase administrative burdens on states.20 Twenty states reported that they would need to change applications, forms, or other guidance, conduct additional staff training, and/or increase outreach and education to immigrant families if the public charge rule is finalized, while most of the remaining states indicated they could not yet determine how the rule would impact their operations.

Report: Introduction

This 17th annual survey of the 50 states and DC provides data on Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2019 and changes implemented in 2018. The report is based on a telephone survey of state Medicaid and CHIP program officials conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families during January 2019. It includes findings in three key areas: Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment and Renewal Processes, and Premiums and Cost Sharing. State-specific information is available in Appendix Tables 1-20. The report includes policies for children, pregnant women, parents, and other adults under age 65 (who are determined eligible based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) financial eligibility rules); it does not include policies for groups eligible through Medicaid eligibility pathways for seniors and individuals eligible based on a disability (non-MAGI groups).

Evolution of Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment

Medicaid has expanded over time to fill gaps in coverage and provide a broad base of coverage for the low-income population. Historically, Medicaid eligibility was tied to cash assistance and limited to low-income individuals in certain categories, including children, pregnant women, parents, seniors, and individuals with a disability. Over time, Congress gradually expanded Medicaid eligibility for children, and it was formally delinked from cash assistance in 1996. Following this delinking and the enactment of CHIP in 1997, many states continued to expand eligibility for children and pregnant women. Moreover, many states pursued innovative outreach and enrollment efforts to help mitigate coverage losses associated with delinking Medicaid from cash assistance and facilitate enrollment of eligible but uninsured children and pregnant women under the broader eligibility rules. However, eligibility for parents remained limited and other nondisabled adults were excluded from the program regardless of income. The ACA filled these coverage gaps by expanding Medicaid to low-income adults with incomes up to 138% FPL and providing enhanced federal funding to states for expansion coverage.

In addition, the Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and renewal experience has evolved from a paper-based, cumbersome process to a modernized, streamlined approach. Prior to the ACA, Medicaid enrollment processes in many states reflected the program’s historic ties to cash assistance. As of January 2013, over half of states imposed an asset test on parents, and some still required parents to complete a face-to-face interview at enrollment or renewal. Applications could only be completed by mail or in-person in a number of states and eligibility determinations could sometimes take days or weeks. The ACA accelerated the adoption of new data-driven enrollment and renewal processes that align and coordinate with the Marketplaces. These processes allow individuals to connect to coverage more quickly and conveniently and reduce the paperwork burden on states and individuals. The streamlined enrollment and renewal policies apply to all states regardless of whether they expanded Medicaid under the ACA. Many of the ACA policies built on innovations states implemented to facilitate enrollment when they expanded coverage for children following the enactment of CHIP. This previous state experience and research showed that complex enrollment processes with burdensome requirements create barriers for eligible individuals to obtain and maintain coverage and increase administrative burdens and costs for states.21 ,22

Report: Medicaid And Chip Eligibility

Eligibility as of January 2019

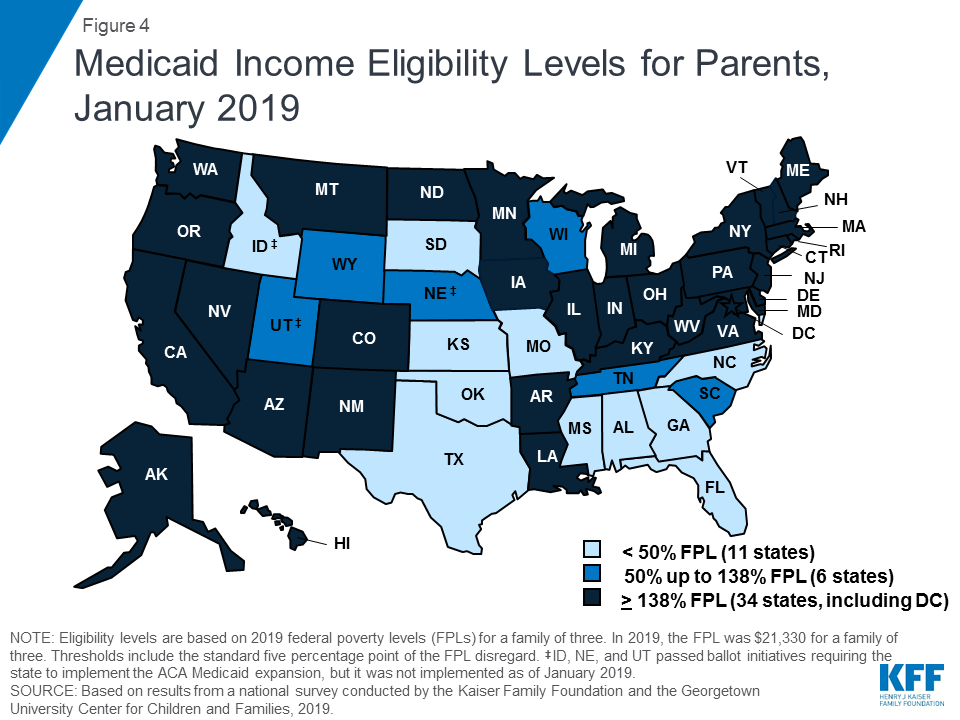

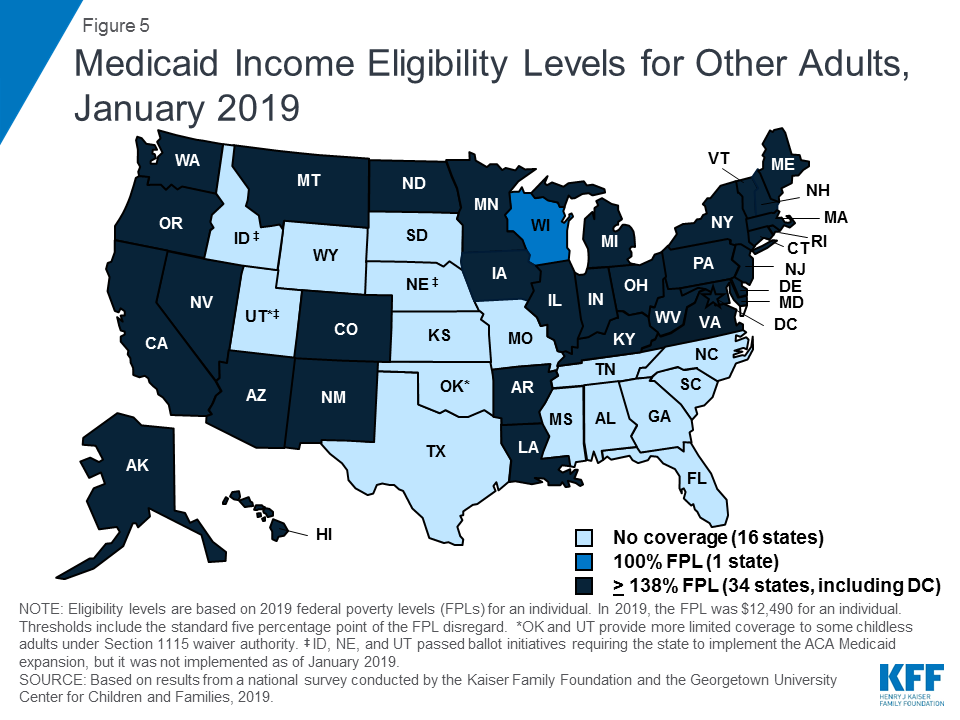

Under the ACA, most states have expanded Medicaid to low-income adults. As of January 2019, 34 states, including DC, had implemented the Medicaid expansion, extending eligibility to parents and other adults with incomes up to 138% FPL ($29,435 for a family of three or $17,236 for an individual as of 2019) (Figures 4 and 5). Connecticut and DC provide eligibility to higher levels. DC covers parents to 221% FPL and other adults to 215% FPL, and Connecticut restored parent eligibility to 155% FPL in 2018, after it had been reduced to 138% FPL in 2017.

There was an uptick in state action to expand in the past year, with five additional states taking steps forward. In January 2019, Maine and Virginia implemented the Medicaid expansion, significantly increasing eligibility for parents and other adults (Figure 6). Through ballot initiatives in November 2018, Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah voters adopted the expansion, although it had not yet been implemented as of January 2019, and Utah and Idaho are seeking to add restrictions to their expansions. With this state action, 37 states, including DC, had adopted the expansion as of January 2019.

In the 14 states that have not yet adopted or implemented the Medicaid expansion, eligibility levels remain limited to very low-income parents, and other adults are largely ineligible. In these states, the median eligibility level for parents was 40% FPL, or $8,532 for a family of three, with ten states limiting parent eligibility to less than half of the poverty level. Other adults remain ineligible for Medicaid regardless of their income in all of these states, except Wisconsin. Moreover, in 10 of these 14 states, the parent eligibility level has been eroding over time as a percent of the FPL (from 42% FPL to 39% FPL between January 2014 and January 2019), because it is tied to a static dollar threshold, while the FPL generally increases each year. This erosion further widens the disparity in coverage available for adults in expansion states versus those that have not yet adopted the expansion.

As of January 2019, eligibility levels for children were robust, with 49 states covering children with incomes above 200% FPL (Figure 7). Eligibility levels for children ranged from 175% FPL to 405% FPL across states, with a median level of 255% FPL. All states use CHIP funding to extend children’s coverage through a Medicaid expansion, a separate CHIP program, or a combination of both approaches. As of January 2019, 36 states had a separate CHIP program, which provides states additional flexibility with regard to benefits, premiums, and cost sharing. However, 16 of these states provide children in their separate CHIP program the full Early, Periodic, Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment Services (EPSDT) benefit that is the Medicaid benefit standard for children.

In 2018, Congress extended CHIP funding through 2027, which supports stable coverage for children. This action followed the longest funding lapse since the CHIP program was enacted in 1997, which had put continued coverage in jeopardy. The legislation retained the MOE provision requiring states to preserve children’s eligibility levels and enrollment policies. Starting in October 2019, however, the MOE will not apply to eligibility levels above 300% FPL.23 At that time, states may continue covering children at these higher income levels and receive federal funding, but they would newly have the option to reduce eligibility to 300% FPL. This change in the MOE coincides with the beginning of a phase-out of the 23-percentage point temporary boost in federal CHIP matching rates. Also in 2018, Congress passed legislation requiring states to cover all former foster youth up to age 26 in Medicaid, regardless of where the youth was in foster care.24 Previously, states were only required to cover those who had been in foster care within the state. This provision will become effective in 2023. In the interim, as of January 2019, 11 states have a waiver to cover former foster children regardless of whether they had been in care within the state, with Michigan discontinuing this coverage in 2018.

Almost half of states (22) report using CHIP funds to support a Health Services Initiative (HSI). Since the enactment of CHIP in 1997, states have had an option to utilize CHIP funds to support a state-designed HSI to improve the health of low-income children, as long as CHIP administrative costs combined with HSI services do not exceed 10% of total CHIP expenditures. HSIs must directly improve the health of low-income children who are eligible for CHIP and/or Medicaid but may serve children regardless of income. States reported a variety of purposes for their HSIs with the most common including supporting poison control systems, enhancing access to health services in schools, providing immunization services, and funding lead abatement efforts. Several states have enacted multiple initiatives through HSI funding with unique purposes ranging from supporting early reading programs in Oklahoma to providing respite care for children with developmental disabilities in New Jersey.

The median eligibility level for pregnant women remained steady at 200% FPL, with the upper eligibility limit ranging from 138% FPL to 380% FPL across states. The majority of states (47) provide Medicaid eligibility to pregnant women beyond the federal minimum of 138% FPL, and nearly half of states (22) extend eligibility to above 200% FPL (Figure 8). Five states use CHIP funds to cover pregnant women above Medicaid levels. In 46 states, pregnant women receive full Medicaid benefits (versus pregnancy-related services only), and all five states covering pregnant women with CHIP funds provide full CHIP benefits. All states are required to provide family planning services to individuals in Medicaid, while 28 states offer family planning services to individuals not otherwise eligible for Medicaid through a state option or waiver.25 In 2018, Maryland expanded family planning eligibility to 264% FPL to match its eligibility level for pregnant women and extended eligibility to men while New Mexico added age restrictions to its coverage.

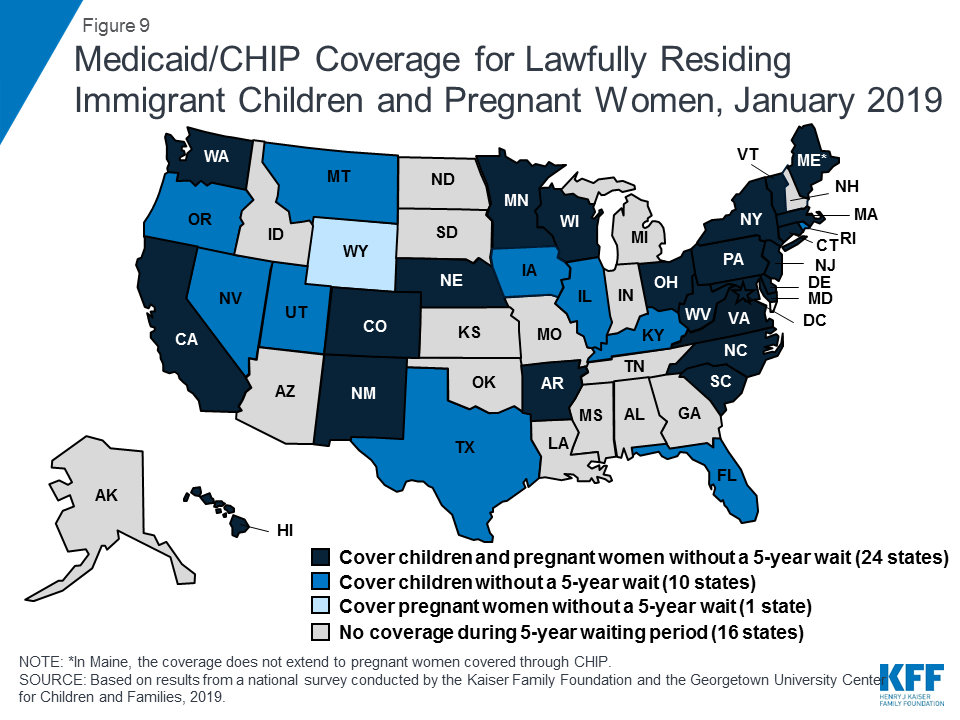

A total of 35 states have taken up the option to eliminate the five-year waiting period for Medicaid/CHIP coverage for lawfully-residing immigrant children and/or pregnant women (Figure 9). Lawfully residing immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and CHIP but are subject to eligibility restrictions. In general, they must have a “qualified” immigration status and many, including most lawful permanent residents or “green card” holders, must wait five years after obtaining qualified status before they may enroll.26 States have an option to eliminate the five-year wait for lawfully residing immigrant children and pregnant women.27 Half of states (24) apply the option to both children and pregnant women, while ten states use it for children only, and one state (Wyoming) uses it only for pregnant women. This count includes Nevada, which implemented the option for children in January 2019. Since 2002, states also have had the option to provide prenatal care to women regardless of immigration status by extending CHIP coverage to the unborn child, which 16 states provided as of January 2019. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP, but some states have fully state-funded programs that cover certain groups of immigrants regardless of immigration status, including seven states that cover all income-eligible children.28

Emerging Eligibility Restrictions in Section 1115 Waivers

In 2018, some states obtained Section 1115 waivers to add eligibility requirements to their Medicaid programs not otherwise allowed under federal rules. Many of these provisions are targeted to low-income adults made eligible by the ACA Medicaid expansion, although, in some states, they also affect poor parents and other traditional groups that existed prior to the ACA.29 ,30 As of January 2019, 13 states had approved waivers that allow one or more eligibility requirements, including conditioning eligibility on meeting a work requirement, adding completion of a health risk assessment as an eligibility requirement, charging premiums or monthly contributions, eliminating retroactive eligibility, delaying coverage until the first premium payment, and/or locking enrollees out of coverage for a period of time if they have unpaid premiums or do not complete timely renewals or report changes in circumstances.31 However, many of these provisions had not yet been implemented as of January 2019.

These new eligibility requirements will increase barriers to coverage and contribute to coverage losses.32 ,33 Under these new requirements, eligible people may lose coverage due to their inability to navigate more complicated enrollment processes and requirements, such as documenting work or a qualifying exemption.34 Moreover, a large and longstanding body of research shows that premiums serve as an enrollment barrier among the low-income population.35 As such, implementation of the eligibility restrictions will likely lead to reductions in Medicaid enrollment and erode coverage gains achieved under the ACA. For example, in Arkansas, the first state to implement a work requirement under a waiver, over 18,000 individuals lost coverage between September and December 2018 due to not meeting the work reporting requirements.36 Additional research is needed to understand more about enrollees who lost coverage, but an early study found that many enrollees in Arkansas were unaware of or confused by the new requirements (despite outreach efforts) and faced multiple barriers complying with the work and reporting requirements that initially could only be reported online.37

Recent waiver provisions also would make enrollment processes more complex and increase administrative burdens on states.38 Implementing these types of eligibility provisions increases documentation requirements on individuals and states and can be administratively complex and costly. A number of states reported that implementing or preparing to implement these waivers increased administrative costs, staff time, the length of time to process renewals, and/or required changes to systems. For example, states implementing work requirements likely have to make system changes to reflect new eligibility rules; document compliance with new requirements; interface with other programs; implement coverage lockout periods; and exchange information among the state, enrollment broker, health plans, and providers. Additional staff may be required to educate enrollees, develop notices, evaluate and process exemptions, and review applications as churn increases and enrollees reapply or appeal coverage lockout periods.

Report: Medicaid And Chip Enrollment And Renewal Processes

Enrollment and Renewal Processes as of January 2019

The ACA accelerated the adoption of data-driven enrollment and renewal processes that align and coordinate with the Marketplaces. Prior years of the survey documented that states have made significant progress upgrading or building new systems and re-engineering their business processes to provide a more modernized and streamlined enrollment and renewal experience that increasingly relies on electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria. As noted in last year’s report, continued advancement leveled off as these systems and processes matured, although states continued to implement targeted improvements and some states are still engaged in system upgrades. This year’s data shows continued progress in some areas, plans for continued improvements, and insight into how states’ current eligibility operations compare to prior to the ACA.

Eligibility Systems and Operations

Implementation of the ACA required states to change eligibility systems to implement new MAGI-based financial eligibility methodology for pregnant women, children, parents, and expansion adults and to apply streamlined eligibility and enrollment processes for MAGI groups that coordinate with the Marketplaces. To assist states with ACA implementation and accelerate the use of technology, the federal government increased the federal match available for states to implement new or upgraded systems to 90%.

States took varied approaches to implement system changes to reflect MAGI-based Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment processes. As of January 2019, most states had launched a new eligibility system or made a significant system upgrade, while others made only necessary adjustments to existing systems. Some states implemented new systems or major upgrades when the ACA was first implemented in 2014, while others have done so more recently. Some states are still implementing new systems or upgrades, either to replace older legacy systems or to build upon and continue to improve newer systems. Tennessee, which had relied solely on the Federally-facilitated Marketplace (FFM) to implement ACA policies, launched its new combined Medicaid and CHIP eligibility system on a pilot basis in select counties in 2018, with statewide expansion planned for early 2019.

In many states, these system upgrades and re-engineered processes have contributed to improvements in eligibility and enrollment operations compared to before the ACA. Most states (34 of 46 reporting states) reported improvement in at least one area of eligibility operations compared to prior to the ACA (Figure 10). Officials in some states described how new systems provided increased efficiency and accuracy and freed up eligibility workers to work on more complex cases. Some states reported no change in their operations compared to prior to the ACA. Only six states reported that one or more of these aspects of operations were worse, but a number of those states were in the process of implementing a new system, which is often associated with short-term challenges.

Applications, Online Accounts, and Mobile Access

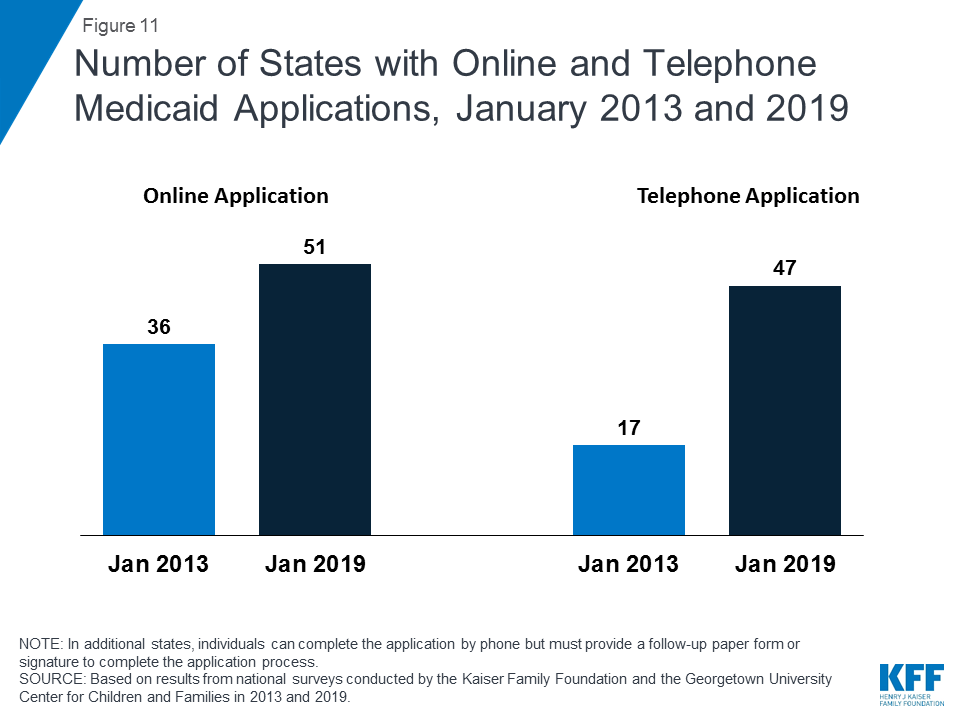

With Tennessee’s launch of a new eligibility system and accompanying web-based application in 2018, individuals can apply online for Medicaid in every state as of January 2019.39 In contrast, online applications were only available in 36 states in January 2013, the year prior to the implementation of the ACA coverage provisions (Figure 11). In 38 states, individuals can complete the online application using a mobile device, and 20 states have made the online application mobile-friendly and/or developed a mobile “app” for the application. In 2018, Indiana and Tennessee developed the capacity for individuals to apply using a mobile device, New Hampshire and Nevada added a mobile-friendly design to their application, and Wisconsin launched a mobile “app” for its online application. Additional states plan to enhance mobile functionality in 2019 or later. All states also offer the ability for individuals to apply via telephone, but four states have not enabled telephonic signatures and require a follow-up paper form or electronic signature to complete the application. The broad availability of telephone applications also represents a significant increase compared to prior to the ACA, when telephone applications were accepted in only 17 states.

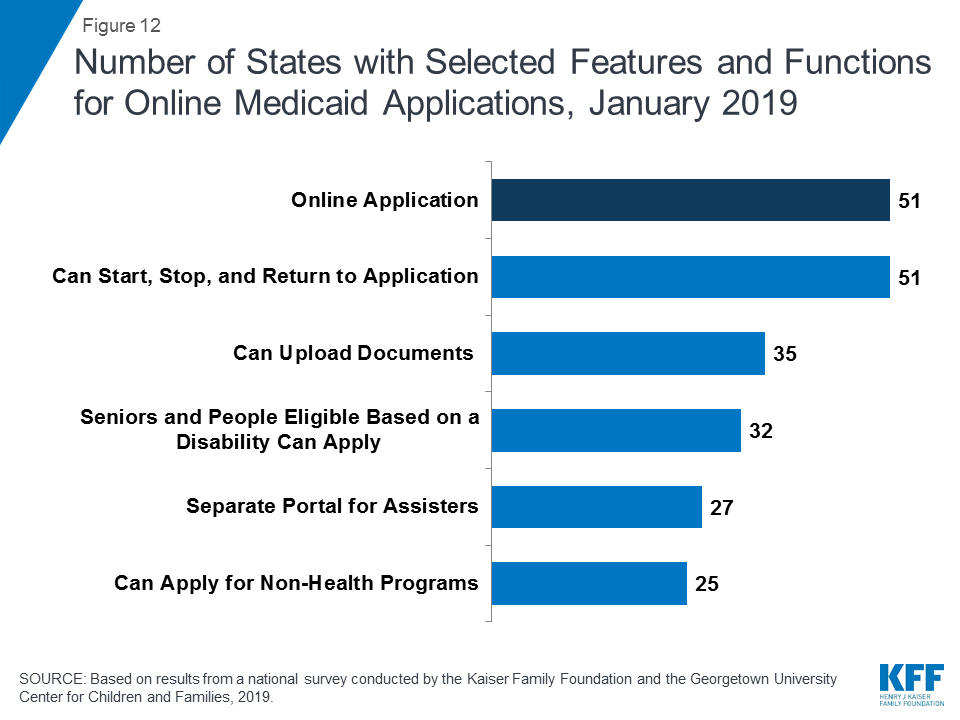

All states have designed their online applications so that individuals may start, stop, and return to the application (Figure 12). In addition, two-thirds of states (35) provide the option for individuals to scan and upload documents that may be needed to verify eligibility, and 27 states have separate portals for application assisters to submit facilitated applications. In 32 states, all Medicaid eligibility groups (children, pregnant women, adults, seniors, and individuals eligible based on a disability) can apply through a combined online application. Half of the states (25) offer a multi-benefit online application that also allows individuals to apply for at least one non-health program such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), or child care assistance. These combined applications can facilitate individuals’ access to a broader array of services, but also may increase the length and complexity of the application.

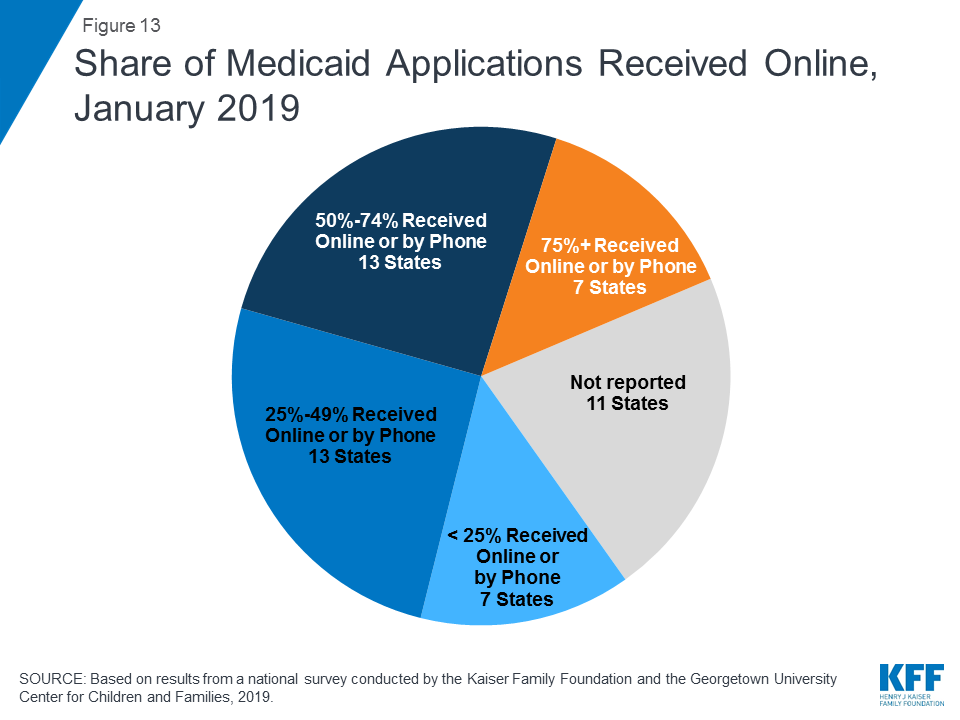

Although online applications offer potential benefits to individuals and states, other application pathways remain important. Online applications can make applying for coverage more convenient and accessible for some individuals, and can facilitate faster processing of determinations, limit data entry errors, and reduce state administrative burdens. However, other application pathways remain important for individuals who may not have easy access to a computer or the internet or who feel more comfortable applying in-person or through a paper form. Among the 40 states able to report data on modes of application, the median share of applications received online was 50%. The remaining half came via phone, in-person, or mail, although the share of telephone applications was very small in many states. Of these 40 states, 20 reported receiving half or more of applications online, including 7 states that reported receiving at least 75% of applications online (Figure 13). However, the share varied widely across states, ranging from 4% in Mississippi to 90% or higher in Florida, New York and Texas.

States continued to advance the use of electronic accounts for enrollees to review or submit information. Online accounts add convenience for enrollees to access and update their information and efficiencies for states by eliminating the need for caseworkers to manually enter information like address changes. With New Jersey and Tennessee implementing electronic accounts, 42 states provided electronic accounts as of January 2019. During 2018, states also continued to expand the functions and features of existing accounts. As of January 2019, most states offer a broad array of functions through their accounts (Figure 14). In 33 of the 42 states with an electronic account, enrollees can access the account through a mobile device. Additionally, 21 states indicate that the online account has been designed with mobile-friendly formatting and six report that they have created a mobile “app” through which individuals can access their account. Several states reported plans to enhance mobile access to online accounts during or after 2019.

Eligibility Determinations

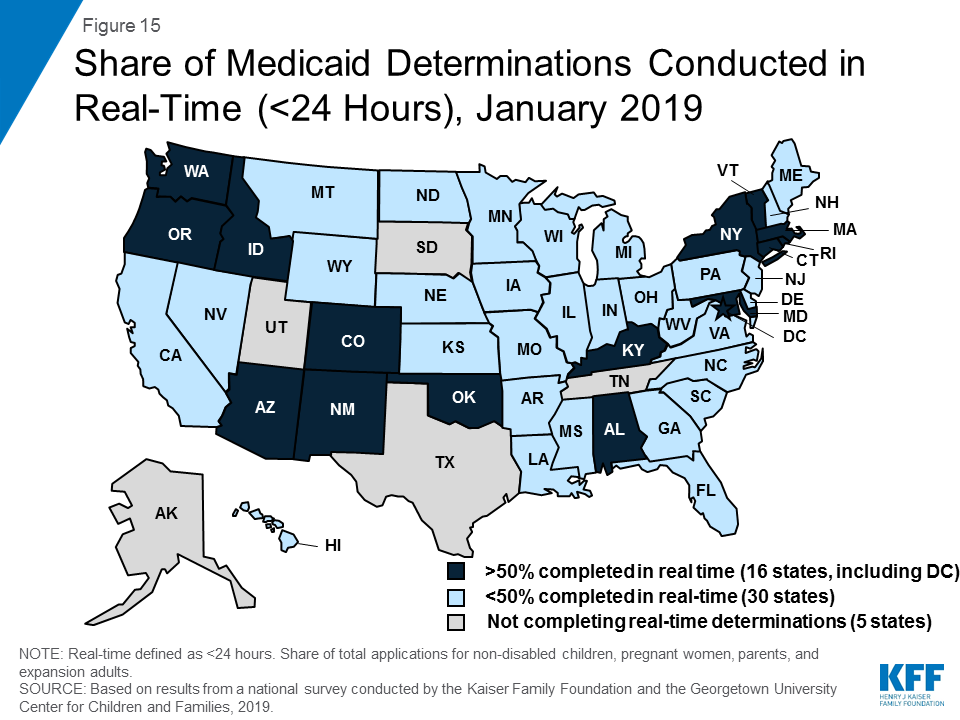

With new or upgraded eligibility systems, states are increasingly able to make real-time eligibility determinations (within 24 hours) by using electronic data matches to verify eligibility criteria. As of January 2019, 46 states are able to make real-time eligibility determinations. However, the share of determinations completed in real-time varies widely across states. A total of 16 states report conducting at least half of MAGI-based determinations in real-time, including 9 states which make three-quarters or more of determinations in under 24 hours (Figure 15). States processing the majority of their applications in real-time are more likely to report that most are made by the eligibility system automatically without caseworker action, while those processing a lower share in real-time are more likely to require caseworker interaction to complete the determination. Automated determinations are more efficient and can reduce data entry errors and administrative burden, but systems and links to trusted data sources must be well-tested and subject to ongoing quality assurance to ensure accuracy.

The majority of states do not report any problems or delays in their eligibility determinations. However, ten states indicated problems or delays as of January 2019. About half of these states are continuing to make changes to systems and processes, which may be contributing to these challenges. Other reasons for backlogs include gaps in staffing and resources or increased volume of applications resulting from recent implementation of the Medicaid expansion.

All states verify citizenship or qualified immigration status, as well as income, when determining eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP. States are able to electronically verify citizenship or immigration status either directly with the Social Security Administration or Department of Homeland Security or through the federal data services hub that consolidates access to these sources. These verifications must be conducted prior to determining eligibility, however, individuals who attest to a qualified status must be given a reasonable amount of time to provide documentation if eligibility cannot be confirmed electronically. While states must also verify income, they have the option to do so prior to enrollment, which 45 states do, or to enroll based on the applicant’s reported income and verify post-enrollment. Verification policies for other eligibility criteria, including age/date of birth, state residency, and household size, vary across states, reflecting state options to verify this information before or after enrollment or to accept the individual’s self-attestation.

Just over half of states (28) report that they conduct data matches on a periodic basis to identify changes in circumstances between annual redetermination periods. States may disenroll individuals if these data checks reveal changes in income or other information that affect eligibility and the individual is unable to resolve the discrepancy within specified timeframes (often within ten days from the date of the notice). These data checks can lead to coverage losses among eligible individuals if they do not receive the notice or are not able to provide documentation within the required timeframe. States vary in the frequency of these checks. For example, some conduct them quarterly, while others conduct only one check between annual renewals. In 2018, Minnesota and Tennessee implemented routine data checks to verify eligibility. Several additional states have recently passed legislation or are considering legislation to require stricter and more frequent data checks.40 ,41

The need for presumptive eligibility has decreased as states are increasingly able to process determinations quickly, but it remains an avenue in some states for people to access temporary coverage when they are unable to receive a real-time determination. Presumptive eligibility is a long-standing policy option that allows states to train and authorize qualified entities such as federally qualified health centers or prenatal clinics to make a temporary eligibility determination so that individuals can quickly access temporary coverage while their final eligibility determination is processed. The ACA expanded the use of presumptive eligibility to allow hospitals in all states to presumptively enroll MAGI-based groups including parents and expansion adults, although Arkansas obtained an exemption from this requirement through a Section 1115 waiver. As of January 2019, 30 states use presumptive eligibility for pregnant women and 20 states have adopted the policy for children. Fifteen states also have extended the policy to parents, adults, family planning services, and/or former foster youth.

System Integration

States continue to reintegrate Medicaid eligibility determinations for seniors, individuals eligible based on a disability, and non-health programs into their upgraded Medicaid systems. Prior to the ACA, state systems generally determined eligibility for all Medicaid groups and most included non-health programs, such as TANF and SNAP.42 The ACA required states to use new financial eligibility rules and streamlined enrollment policies for MAGI-based groups. However, states continue to apply their pre-ACA financial eligibility rules to non-MAGI groups (seniors and individuals eligible based on a disability). As a result, some states separated MAGI eligibility determinations from non-MAGI groups and non-health programs when they implemented the ACA. As their new systems have matured, states have increasingly reintegrated non-MAGI groups and non-health programs into the upgraded systems. This trend continued in 2018, with Iowa and Tennessee integrating non-MAGI groups into their systems. As of January 2019, 32 states determine eligibility for all Medicaid groups through a single system, and, in 24 states, the MAGI-based Medicaid eligibility system determines eligibility for at least one non-health program. This integration can facilitate access to services for individuals and offer efficiencies to states but requires more complex system implementation. States also have realized progress integrating Medicaid and CHIP eligibility determinations. Prior to the ACA, less than half of states with separate CHIP programs (16 of 38) used a single system for Medicaid and CHIP, but, as of January 2019, all but 1 of the 36 states with separate CHIP programs determine eligibility through a single system. Looking ahead, states remain focused on reintegration with nearly half indicating plans to integrate non-MAGI groups and/or additional non-health programs into their MAGI-based system in 2019 or beyond.

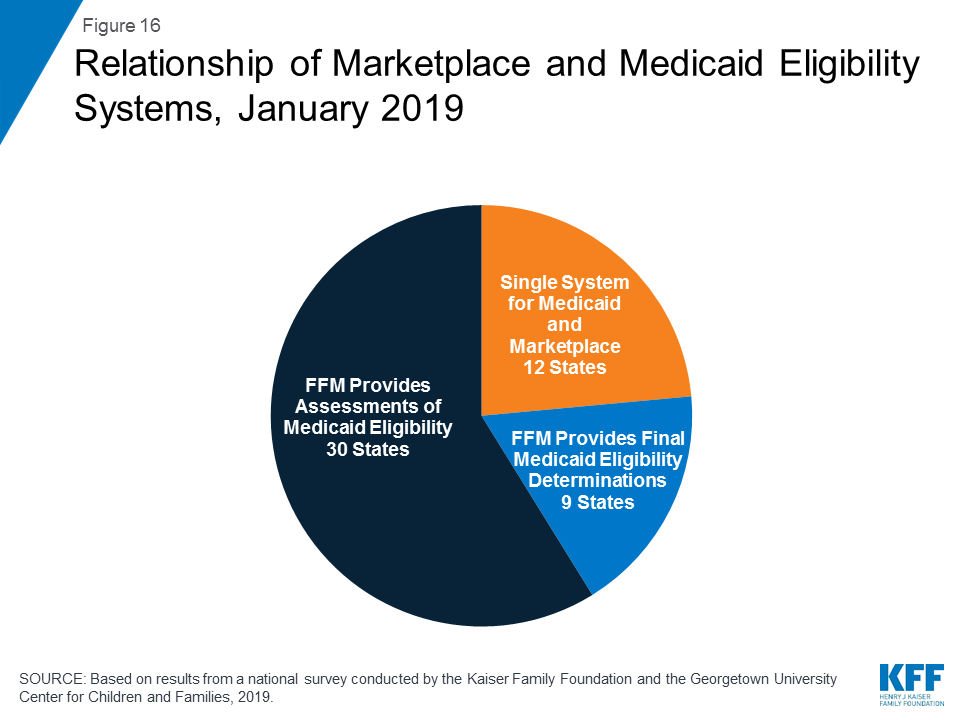

All states coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace coverage, as required under the ACA. However, how states coordinate this coverage depends on the structure of its Marketplace. Most states (39) rely on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) system, known as Healthcare.gov, for Marketplace eligibility determinations and enrollment. These states must electronically transfer data back and forth with the FFM to coordinate Medicaid and Marketplace coverage. States report that these transfers generally are going smoothly without any significant delays or problems. Of the 39 states relying on the FFM platform, 30 states use the FFM only to assess Medicaid eligibility, and then make a final determination after the case is transferred to the state. In 2018, Arkansas shifted to receiving assessments from the FFM. Nine states allow the FFM to make final Medicaid or CHIP determinations, including Virginia, which switched from an assessment to a determination state in 2018 to facilitate its implementation of the Medicaid adult expansion. In the remaining 12 states that use their own State-based Marketplace system, Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace determinations are conducted through a single integrated system (Figure 16).

Renewals

Streamlined renewal policies can facilitate continuous coverage among eligible individuals, which helps prevent gaps in care and protects individuals from medical costs that might occur if they experience breaks in coverage. Under ACA policies, states are required to use available data to determine ongoing eligibility before requesting the enrollee to complete a renewal form or provide documentation. If a state is unable to determine ongoing eligibility based on available data, it may then request additional information from the individual and must provide the individual multiple avenues to renew, including online, by phone, in-person, or via mail. The move to automatic renewals can help reduce “churn” or short gaps in coverage, contribute to efficiencies and cost savings, and reduce data entry errors and administrative burden. However, eligible individuals may remain at risk for losing coverage at renewal if the state is unable to determine ongoing eligibility based on available data and they do not receive or understand notices or forms requesting additional information and respond to requests within required timeframes, which are often limited to 10 days.

As of January 2019, 46 states were completing automatic or “ex parte” renewals, through which the state renews coverage based on available eligibility-related data. Among the 43 states able to report the share of renewals completed through automated processes, 21 states reported at least half of MAGI renewals are conducted automatically, including 10 states that complete three-quarters or more of renewals automatically (Figure 17). States with a high share of automatic renewals are more likely to have a system that can complete the renewals without requiring caseworker action. Conversely, states that rely on manual action by a caseworker—for example, to look up data to verify ongoing eligibility—generally report a smaller share of renewals completed automatically.

When unable to renew coverage based on available data, 46 states send pre-populated forms to enrollees to facilitate the renewal process (Figure 18). This count includes Tennessee and Vermont which began sending pre-populated forms in 2018. Idaho stopped mailing pre-populated forms in 2018, and like Florida and Oklahoma, sends a notice to the individual requesting that they log into their online account or call to confirm their information and/or report any changes. Most states (41), allow individuals to renew by phone; and four additional states allow individuals to complete most of the renewal process by phone, but still require a paper form or electronic signature to complete the process.

As of January 2019, the majority of states were up-to-date in processing Medicaid and CHIP renewals. However, ten states reported delays with most of these states overlapping with the ten states that reported delays in application processing. Causes of renewal delays were similar to those contributing to backlogs in eligibility determinations, including issues related to system upgrades or challenges related to staffing and volume of renewals.

Nearly two-thirds of the states (32) minimize gaps in coverage for children by providing 12-month continuous eligibility in either Medicaid and/or CHIP. All states are required to renew coverage every 12 months for children, pregnant women, parents and expansion adults. However, during that 12-month period, individuals may lose coverage if they experience a change in circumstance that makes them ineligible, such as an increase in income. For children, states can opt to provide 12-month continuous eligibility, which allows a child to remain enrolled for a full year unless the child ages out of coverage, moves out of state, voluntarily withdraws, or does not make required premium payments. Continuous eligibility promotes stable access to care by reducing “churn” or individuals moving on and off coverage due to modest, and often temporary, changes in circumstances such as overtime or extra seasonal work. Continuous eligibility also facilitates a more accurate assessment of the quality of health care children receive in Medicaid and CHIP because most quality measures require minimum periods of enrollment. As of January 2019, 24 states have adopted continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid and CHIP, and eight additional states have implemented the policy only in their separate CHIP programs. Montana and New York also provide 12-month continuous coverage for adults through a Section 1115 waiver.

Report: Premiums And Cost Sharing

Research shows that premiums serve as a barrier to enrollment for low-income families and copayments can limit utilization of needed health care.43 Federal regulations establish parameters for premiums and cost sharing for Medicaid and CHIP enrollees that reflect their limited ability to pay out-of-pocket health care costs due to their modest incomes. Under these rules, states may not charge premiums in Medicaid for enrollees with incomes less than 150% FPL. However, some states have obtained waivers to impose charges in Medicaid that are not otherwise allowed. Maximum allowable cost sharing varies by type of service and income in Medicaid (Table 1). CHIP programs have more flexibility in regard to premiums and cost sharing, but both Medicaid and CHIP limit total family out-of-pocket costs to no more than 5% of family income.

Box 1: Medicaid and CHIP Premium and Cost Sharing Rules

Premiums in Medicaid. States may charge premiums for children and adults with incomes above 150% FPL. Medicaid enrollees with incomes below 150% FPL may not be charged premiums.

Cost Sharing in Medicaid. States may charge cost sharing for adults in Medicaid, but allowable charges vary by income (Table 1). Cost sharing cannot be charged for emergency, family planning, pregnancy-related services in Medicaid, preventive services for children, or for preventive services in Alternative Benefit Plans in Medicaid, which have been defined as essential health benefits. In addition, children with incomes below 133% FPL generally cannot be charged cost sharing.

Limit on Out-of-Pocket Costs. Overall, premium and cost sharing amounts for family members enrolled in Medicaid may not exceed 5% of household income.

Premiums and Cost Sharing in CHIP. States have somewhat greater flexibility to charge premiums and cost sharing for children covered by CHIP, although there remain limits on the amounts that can be charged, including an overall cap of 5% of household income.

| Table 1: Allowable Cost Sharing Amounts for Adults in Medicaid by Income | |||

| <100% FPL | 100% – 150% FPL | >150% FPL | |

| Outpatient Services | up to $4 | up to 10% of state cost | up to 20% of state cost |

| Non-Emergency use of ER | up to $8 | up to $8 | No limit |

| Prescription Drugs | Preferred: up to $4Non-Preferred: up to $8 | Preferred: up to $4Non-Preferred: up to $8 | Preferred: up to $4Non-Preferred: up to 20% of state cost |

| Inpatient Services | up to $75 per stay | up to 10% of state cost | up to 20% of state cost |

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Children

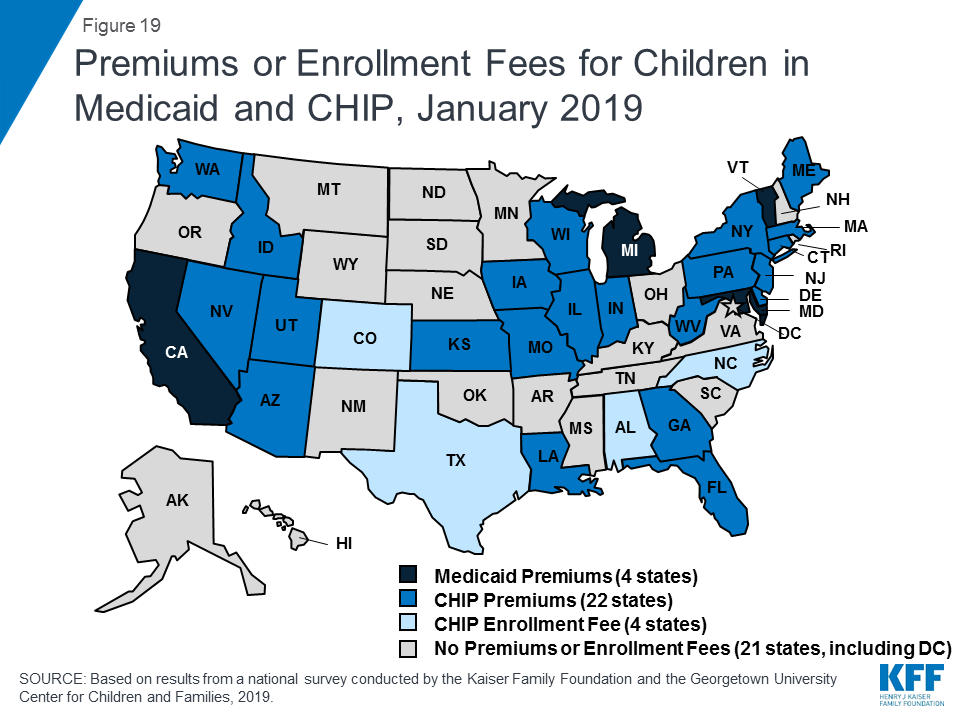

The number of states (30) charging premiums or enrollment fees to children in Medicaid/CHIP held steady in 2018 (Figure 19). The stability of premiums, in part, reflects that the extension of CHIP funding also extended the MOE provision for children’s eligibility and enrollment policies. Under the MOE, states may not implement new premiums or increase premiums outside of routine increases that were approved in the state’s plan as of 2010. Premiums and cost sharing are much more prevalent in CHIP than Medicaid, reflecting that the program covers families with more moderate income levels. Only four states charge premiums for children in Medicaid. These premiums are limited to children in CHIP-funded Medicaid expansions and the lowest income level at which they are charged is 160% FPL. Among the 36 separate CHIP programs, four charge annual enrollment fees and 22 impose monthly or quarterly premiums for children; the lowest income at which these charges begin is 133% FPL.

States vary in disenrollment policies related to non-payment of premiums within federal rules designed to minimize gaps in coverage for children. The minimum grace period before canceling coverage for non-payment of premiums is 60 days in Medicaid and 30 days in CHIP. However, 16 of the 22 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in CHIP provide at least a 60 day grace period. Children who are disenrolled from Medicaid for non-payment of premiums cannot be locked-out of coverage for a period of time as a penalty for non-payment, while separate CHIP programs may establish a lockout period of up to 90 days. Among the 22 states charging monthly or quarterly premiums in CHIP, eight states do not impose lockout periods, including Georgia, which eliminated the practice in 2018. As of January 2019, 14 states maintain lockout periods in CHIP ranging from 1 month to 90 days.

As of January 2019, less than half of the states (23) charge copayments to children in Medicaid and CHIP after Kentucky and New Mexico eliminated children’s copayments. In 2018, New Mexico eliminated its copayments for children, leaving only two states (Tennessee and Wisconsin) that require copayments for children in Medicaid. Kentucky also eliminated copayments for children in its separate CHIP program in 2018, reducing the number of states that impose copayments on children to 23 of 36 states with separate CHIP programs (Figure 20). Only one state (Tennessee) imposes cost sharing below 133% FPL due to long-standing waiver authority. Cost sharing varies by state and service. At 151% FPL, 18 states charge cost sharing for non-preventive physician visits, 14 states charge for an inpatient hospital visit, and 14 charge for generic drugs.

Premiums and Cost Sharing for Parents and Other Adults

Some states have obtained waivers to charge premiums or monthly contributions for adults in Medicaid that would not otherwise be allowed under federal rules. As of January 2019, five states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) have implemented premiums or monthly contributions for expansion adults, and, in Indiana, the charges also apply to parents. In 2018, Indiana used waiver authority to add a tobacco surcharge of 50% of the normal monthly contribution if the enrollee has been a tobacco user for the past year. Some of these waivers also allow individuals to be locked out of coverage for a period of time if they are disenrolled due to non-payment and to delay coverage until after the first premium is paid. An additional four states (Arizona, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Wisconsin) have obtained waiver approval to charge premiums or monthly contributions to adults and, in some cases, impose lockout periods or delay coverage, but they were not yet implemented as of January 2019. New Mexico is no longer planning to implement the premiums following a change in state leadership and implementation was on hold in Arizona and Wisconsin, while Kentucky is in the process of preparing for implementation.

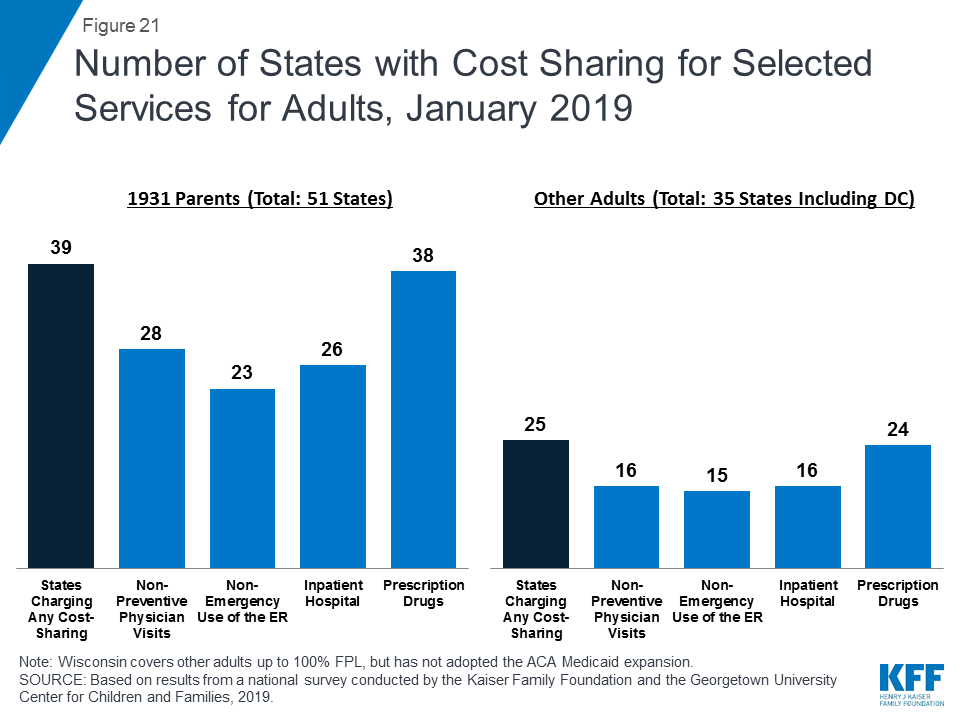

As of January 2019, most states charge cost sharing for parents and other adults. A total of 39 states charge copayments for parents eligible for Medicaid under traditional pathways that existed before the ACA (Figure 21). In addition, of the 35 states that cover other adults (including the 34 states that have implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion and Wisconsin, which covers other adults but has not adopted the expansion), 25 charge copayments. The number of states charging copayments to traditional parents has remained generally consistent for several years. Although many states impose the charges on all adult beneficiaries, regardless of income, cost sharing amounts in Medicaid are limited by federal law. Two states made minor adjustments to copayments in 2018, including New Hampshire, which lowered cost sharing amounts for expansion adults to match levels charged for 1931 parents, and Indiana which dropped its copayment of subsequent non-emergency use of the emergency room from $25 to $8.

Report: Looking Ahead

Looking ahead, one key question is whether there will be continued advances to expand coverage and streamline enrollment processes or whether emerging policy changes will erode coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA.

Additional states may expand Medicaid, which would increase access to coverage for low-income adults and have positive effects on care and state budgets and economies.44 Several new governors who were elected in 2018 ran on platforms to expand Medicaid. Further, the success of recent ballot initiatives to expand could spark similar action in other states. However, voter-approved ballot measures may face barriers to implementation based on state law requirements, efforts to block or amend the policies by legislators or governors, or legal challenges.45 Ongoing litigation related to the constitutionality of the ACA also could influence state decisions to expand. However, if states attach waiver provisions such as work requirements or other restrictions to expansion, the positive reach and impact would be limited. Recently, some states have indicated interest in a partial expansion to an income level below 138% FPL with the ACA enhanced federal match rate.46 Relative to full expansion, partial expansions could limit coverage and potentially increase federal costs. While states can pursue waivers to extend coverage to a lower income level without access to the enhanced federal match, no waivers to allow an enhanced match for a partial expansion have been approved to date, and guidance from the previous administration prohibited the use of the enhanced match for “partial expansions.”

Renewed CHIP funding protects children’s eligibility levels through 2027, but states that extend eligibility above 300% FPL will have the option to reduce eligibility starting in October 2019. When Congress continued funding for CHIP in 2018, it retained the MOE provision that requires states to preserve Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment policies for children. However, starting in October 2019, the MOE only applies to children’s coverage up to 300% FPL. At that time, states can maintain coverage for children above this income level and still receive federal matching funds, but will newly have the option to reduce eligibility to 300% FPL. This change in the scope of the MOE coincides with the beginning of the phase-out of the 23-percentage point temporary boost in federal CHIP matching rates available between 2016 and 2019. This boost will be reduced by half (11.5 percentage points) in 2020 and then rates revert to the traditional enhanced CHIP match rate in 2021, leaving states to resume paying a larger share of CHIP costs.

Emerging state and federal policies to add Medicaid eligibility requirements could erode the coverage gains and enrollment simplifications realized under the ACA. The Trump Administration is promoting new Medicaid eligibility requirements through waivers and its proposed budget and has approved a growing number of waiver requests from states, including work requirements, which have never previously been approved for the program. Some states are no longer moving forward with implementing waiver provisions following a change in leadership in the 2018 elections,47 ,48 while other states are considering adding waiver provisions.49 ,50 ,51 ,52 Research shows that these types of requirements create barriers for eligible individuals to obtain and maintain coverage and increase administrative burdens and costs for states.53 ,54 As such, they will likely dampen potential coverage gains and lead to coverage losses that would erode the coverage increases realized under the ACA. States’ implementation of waiver provisions could be affected by ongoing legal challenges to the Administration’s authority to approve work requirements and other restrictive measures in Arkansas and Kentucky.

Other policy changes may lead to coverage losses among eligible low-income families and growing burdens on states. In 2017, coverage gains stalled and began to reverse for the first time since the implementation of the ACA and Medicaid enrollment of adults and children declined in 2018.55 ,56 ,57 Some of the decline in Medicaid enrollment could reflect the improving economy. However, some factors may be leading to enrollment declines among eligible individuals. While states’ growing use of technology and automation has led to improvements for individuals and states, there are concerns emerging in some states that eligible individuals may be losing coverage due to process-related issues.58 ,59 ,60 Further, other policy changes outside of Medicaid could be dampening enrollment. For example, the Trump administration substantially decreased funding for outreach and enrollment assistance, which is pivotal for helping eligible individuals get and stay enrolled in coverage. In addition, shifting immigration policies, including the proposed rule to make changes to public charge policy, will likely lead to broad decreases in participation in Medicaid among legal immigrant families and their primarily U.S.-born children and increase administrative burdens on states.61 Twenty states reported they would need to change applications, forms, or other guidance, conduct additional staff training, and/or increase outreach and education to immigrant families if the public charge rule is finalized, while most of the remaining states indicated they could not yet determine how the rule would impact their operations.

Tables

Trend and State-by-State Tables

Table 2: Waiting Period for CHIP Enrollment, January 2019

Table 3: State Adoption of Optional Medicaid and CHIP Coverage for Children, January 2019

Table 8: Features of Online Medicaid Accounts, January 2019

Table 9: Mobile Access to Online Medicaid Applications and Accounts, January 2019

Table 11: Coordination between Medicaid and Other Systems, January 2019

Table 12: Presumptive Eligibility in Medicaid and CHIP, January 2019

Table 14: Premium, Enrollment Fee, and Cost Sharing Requirements for Children, January 2019

Table 15: Premiums and Enrollment Fees for Children at Selected Income Levels, January 2019

Table 16: Disenrollment Policies for Non-Payment of Premiums in Children’s Coverage, January 2019

Endnotes

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Distribution of Eligibility for ACA Health Coverage Among those Remaining Uninsured as of 2017 (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2018), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/distribution-of-eligibility-for-aca-coverage-among-the-remaining-uninsured/ ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/#Table3 ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings ((Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/ ↩︎

- Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz and MaryBeth Musumeci, “Partial Medicaid Expansion” with ACA Enhanced Matching Funds: Implications for Financing and Coverage, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/partial-medicaid-expansion-with-aca-enhanced-matching-funds-implications-for-financing-and-coverage/ ↩︎

- Governor Janet Mills, Letter to CMS Administrator Seema Verma, January 22, 2019, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/me/mainecare/me-mainecare-approval-reponse-ltr-01222019.pdf ↩︎

- Office of Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, “Gov. Lujan Grisham Announces Plan to Reverse Medicaid Policies that Create Barriers to Accessing Coverage,” (Office of Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, Press Release, February 13, 2019), https://www.governor.state.nm.us/2019/02/13/gov-lujan-grisham-announces-plan-to-reverse-medicaid-policies-that-create-barriers-to-accessing-coverage/ ↩︎

- South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “Community Engagement Section 1115 Waiver Application,” South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (March 4, 2019), https://www.scdhhs.gov/public-notice/community-engagement-section-1115-demonstration-waiver-application-0 ↩︎

- The Alaska State Legislature, SB 7, 31st Legislature (2019-2020), accessed March 11, 2019, http://www.akleg.gov/basis/Bill/Detail/31?Root=sb%207 ↩︎

- The Iowa Legislature, Senate File 538, 88th General Assembly, accessed March 11, 2019, https://www.legis.iowa.gov/legislation/BillBook?ba=SF%20538&ga=88 ↩︎

- The Montana Legislature, HB 658, 66th Legislature, accessed March 25, 2019, http://laws.leg.mt.gov/legprd/LAW0210W$BSIV.ActionQuery?P_BILL_NO1=658&P_BLTP_BILL_TYP_CD=HB&Z_ACTION=Find&P_SESS=20191 ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses Appendix, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2018), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/implications-of-a-medicaid-work-requirement-national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses-appendix/ ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Implications of Emerging Waivers on Streamlined Medicaid Enrollment and Renewal Processes, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/implications-of-emerging-waivers-on-streamlined-medicaid-enrollment-and-renewal-processes/ ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Kendal Orgera, and Anthony Damico, The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer – Key Facts about Health Insurance and the Uninsured amidst Changes to the Affordable Care Act, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2019), https://modern.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/ ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid & CHIP Monthly Applications, Eligibility Determinations, and Enrollment Reports: January 2014 – December 2018 (preliminary)”, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, (February 28, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/program-information/medicaid-and-chip-enrollment-data/monthly-reports/index.html ↩︎

- Tricia Brooks, Child Enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP Down 600k Children in 2018, (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, March 2019), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2019/03/02/child-enrollment-in-medicaid-and-chip-took-another-hit-in-november-down-600k-children-in-2018/ ↩︎

- Phil Galewitz, “Missouri’s shrinking Medicaid rolls raise red flag on vetting process,” Kaiser Health News, (February 11, 2019), https://www.stltoday.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/missouri-is-pushing-eligible-people-off-medicaid-including-thousands-of/article_c4bbec5b-26e5-55a6-936a-8904224dbfa7.html? ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Barbara Coulter Edwards, Aimee Lashbrook, Elizabeth Hinton, Larisa Antonisse, and Robin Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/ ↩︎

- Michael Ollove,”Child Enrollment in Public Health Programs Fell by 600K Last Year,” Governing, (March 8, 2019), http://www.governing.com/topics/health-human-services/sl-chip-medicaid-children-enrollment.html ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, Rachel Garfield, and Anthony Damico, Estimated Impacts of the Proposed Public Charge Rule on Immigrants and Medicaid, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/estimated-impacts-of-the-proposed-public-charge-rule-on-immigrants-and-medicaid/. ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses Appendix, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2018), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/implications-of-a-medicaid-work-requirement-national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses-appendix/ ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Implications of Emerging Waivers on Streamlined Medicaid Enrollment and Renewal Processes, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/implications-of-emerging-waivers-on-streamlined-medicaid-enrollment-and-renewal-processes/ ↩︎

- 305% FPL with the five percentage point income disregard that is applied to MAGI-based groups. ↩︎

- U.S. Congress. House. Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act of 2018. HR 6, 115th Congress. Introduced in House June 13, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6 ↩︎

- Some states also have state-funded family planning programs. ↩︎

- Some immigrants with qualified status, such as refugees and asylees, do not have to wait five years before enrolling. Some immigrants, such as those with temporary protected status, are lawfully present but do not have a qualified status and are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP regardless of their length of time in the country ↩︎

- This option also extends coverage to lawfully present immigrants without a qualified status. ↩︎

- The District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, Oregon and Washington use state funds to cover income-eligible children regardless of immigration status. In addition, some states use state funds to cover adult immigrants, but the coverage is often limited to targeted groups. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Hinton, MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, Larisa Antonisse, Cornelia Hall, Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: The Current Landscape of Approved and Pending Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers-the-current-landscape-of-approved-and-pending-waivers/ ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Waiver Tracker: Approved and Pending Section 1115 Waivers by State (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-waiver-tracker-approved-and-pending-section-1115-waivers-by-state/#Table5 ↩︎

- This count excludes Maine, which rejected previously approved waiver terms and conditions in January 2019. Six states (DE, MA, MD, RI, TN, and UT) have retroactive coverage waivers that are not included in this count because they pre-date the ACA and may have been associated with achieving the budgetary savings necessary to expand coverage before federal law authorized the use of Medicaid funds for childless adults. ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Implications of a Medicaid Work Requirement: National Estimates of Potential Coverage Losses (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-a-medicaid-work-requirement-national-estimates-of-potential-coverage-losses/ ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Anthony Damico, Implications of Work Requirements in Medicaid: What Does The Data Say? (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/implications-of-work-requirements-in-medicaid-what-does-the-data-say/ ↩︎

- MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and Perspectives of Enrollees (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-enrollees/ ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings ((Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/ ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Cornelia Hall, January State Data for Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-data-for-medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas/ ↩︎

- MaryBeth Musumeci, Robin Rudowitz, and Barbara Lyons, Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas: Experience and Perspectives of Enrollees (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, December 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas-experience-and-perspectives-of-enrollees/ ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Implications of Emerging Waivers on Streamlined Medicaid Enrollment and Renewal Processes, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/implications-of-emerging-waivers-on-streamlined-medicaid-enrollment-and-renewal-processes/ ↩︎

- Tennessee is phasing the online application in by county with statewide access planned for early 2019. ↩︎

- The Oklahoma Legislature, HB 1270, 56th Legislature (2017), accessed March 11, 2019, http://www.oklegislature.gov/BillInfo.aspx?Bill=hb1270&Session=1800 ↩︎

- The Mississippi Legislature, HB 1010, Regular Session 2017, accessed March 11, 2019, http://billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/2017/PDF/history/HB/HB1090.xml ↩︎

- Martha Heberlein, Tricia Brooks, Joan Alker, Samantha Artiga and Jessica Stephens, Getting into Gear for 2014: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP, 2012-2013, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2013), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/getting-into-gear-for-2014-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-of-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-in-medicaid-and-chip-2012-2013/. ↩︎

- Samantha Artiga, Petry Ubri, and Julia Zur, The Effects of Premiums and Cost Sharing on Low-Income Populations: Updated Review of Research Findings ((Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-premiums-and-cost-sharing-on-low-income-populations-updated-review-of-research-findings/ ↩︎

- Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Larisa Antonisse and Robin Rudowitz, An Overview of State Approaches to Adopting the Medicaid Expansion, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/an-overview-of-state-approaches-to-adopting-the-medicaid-expansion-issue-brief/ ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz and MaryBeth Musumeci, “Partial Medicaid Expansion” with ACA Enhanced Matching Funds: Implications for Financing and Coverage, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/partial-medicaid-expansion-with-aca-enhanced-matching-funds-implications-for-financing-and-coverage/ ↩︎

- Governor Janet Mills, Letter to CMS Administrator Seema Verma, January 22, 2019, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/me/mainecare/me-mainecare-approval-reponse-ltr-01222019.pdf ↩︎

- Office of Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, “Gov. Lujan Grisham Announces Plan to Reverse Medicaid Policies that Create Barriers to Accessing Coverage,” (Office of Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, Press Release, February 13, 2019), https://www.governor.state.nm.us/2019/02/13/gov-lujan-grisham-announces-plan-to-reverse-medicaid-policies-that-create-barriers-to-accessing-coverage/ ↩︎

- South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “Community Engagement Section 1115 Waiver Application,” South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (March 4, 2019), https://www.scdhhs.gov/public-notice/community-engagement-section-1115-demonstration-waiver-application-0 ↩︎

- The Alaska State Legislature, SB 7, 31st Legislature (2019-2020), accessed March 11, 2019, http://www.akleg.gov/basis/Bill/Detail/31?Root=sb%207 ↩︎