HIV, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV), and Women: An Emerging Policy Landscape

Introduction

Women in the United States experience high rates of violence and trauma, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Women with HIV, who represent about a quarter of all people living with HIV in the U.S., are disproportionally affected.1,2,3 Intimate partner violence (IPV), a term often used interchangeably with domestic violence (DV), in particular, has been shown to be associated with increased risk for HIV among women, as well as poorer treatment outcomes for those already diagnosed.4,5 In addition, it has been suggested that women are at greater risk of experiencing violence upon disclosure of their HIV status to partners.6

Given the role that IPV plays in HIV risk, transmission, and care and treatment, decreasing the prevalence of IPV and mitigating its effects is an important part of addressing the HIV epidemic among women in the United States. Policy changes, including those related to health care and coverage, represent one mechanism for addressing the intersection of HIV and IPV. After highlighting key statistics about IPV generally as well as the link between HIV and IPV, this brief will review key policy changes and initiatives that attempt to address these challenges.

| Table 1: Key Terms and Definitions | |

| Term | Definition |

| Intimate Partner | A romantic or sexual partner, including spouses, boyfriends, girlfriends, people with whom an individual dated, were seeing, or “hooked up.” |

| Contact Sexual Violence | A combined measure that includes rape, being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact. |

| Stalking | Involves a pattern of harassing or threatening tactics used by a perpetrator that is both unwanted and causes fear or safety concerns in the victim. |

| Physical Violence | Includes a range of behaviors from slapping, pushing or shoving to severe acts that include being hit with a fist or something hard, kicked, hurt by pulling hair, slammed against something, hurt by choking or suffocating, beaten, burned on purpose, or assaulted with a weapon. |

| Psychological Aggression | Includes expressive aggression (such as name calling, insulting or humiliating an intimate partner) and coercive control, which includes behaviors that are intended to monitor and control or threaten an intimate partner, including through digital technologies. |

| Reproductive Coercion | Includes forced or coerced sex, sabotage of contraception, or the forcible control of reproductive health by an abusive partner. Reproductive coercion can take the form of hiding, withholding, or destroying a partner’s contraceptives, and threats or acts of violence forcing a victim to have an abortion or carry a pregnancy to term. |

| SOURCES: CDC. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief, November 2018; Deshpande N, Lewis-O’Connor A, Screening for Intimate Partner Violence During Pregnancy, 2013; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Committee on Health Care and Underserved Opinion: Reproductive and Sexual Coercion, February 2013. | |

Key Statistics

Women in the United States experience high levels of violence, including sexual violence, across their lifetimes, with the most recent data indicating that approximately 44% of US women report ever having experienced unwanted sexual contact.7 Moreover, an estimated 36% of US women report ever having experienced contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime.8

While IPV can and does occur among all groups, some groups face higher rates of violence. 57% of Multi-Racial Non-Hispanic women, 48% of American Indian/Alaska Native Non-Hispanic Women, and 45% of Black Non-Hispanic Women report facing IPV in their lifetimes (and those shares are likely to be under reported due to a variety of factors).9 Social class, LGBTQ identification, and disability status are also associated with higher rates of IPV. 10,11,12

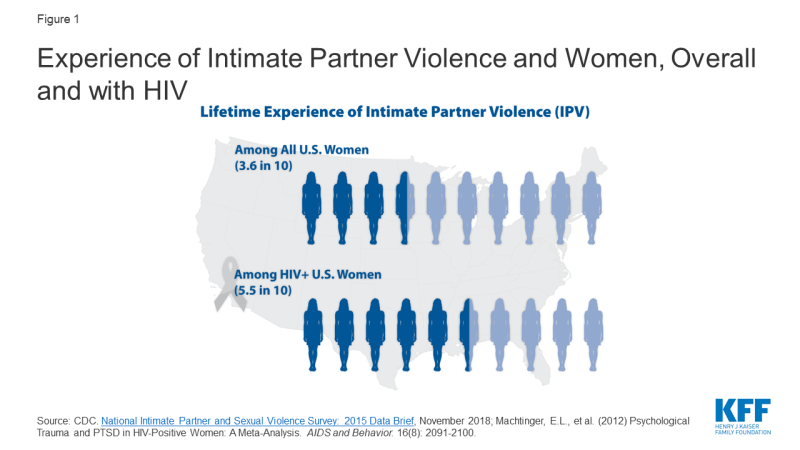

Overall, an estimated 26% of HIV-positive people are estimated to have experienced physically violence by a romantic or sexual partner and 17% are estimated to have been “threatened with harm or physically forced to have unwanted vaginal, anal, or oral sex”13; Among HIV positive women, IPV is even more prevalent, reported by 55% of women living with HIV.14 In addition to the traumatic impact IPV has on all women, the experience of trauma and violence is also associated with poor treatment outcomes and higher transmission risk among HIV positive women.15,16

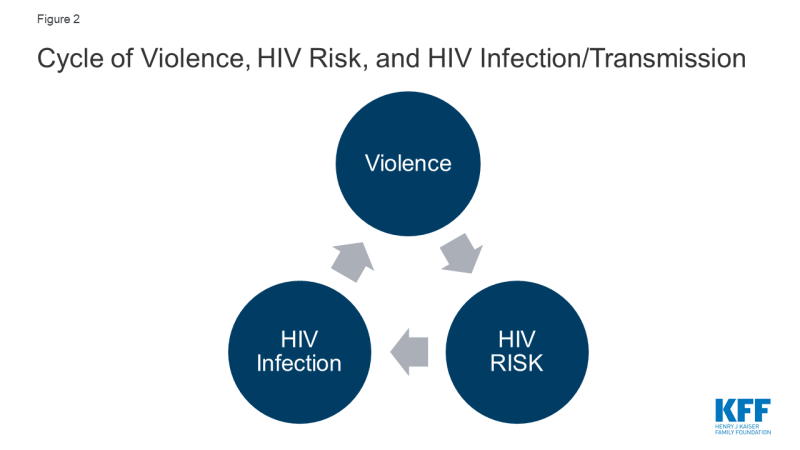

In many cases, the factors that put women at risk for contracting HIV are similar to those that make them vulnerable to experiencing trauma and IPV. Women in violent relationships are at a four times greater risk for contracting STIs, including HIV, than women in non-violent relationships and women who experience IPV are more likely to report risk factors for HIV.17 A nationally representative study found 20% of HIV positive women had experienced violence by a partner or someone important to them since their diagnosis and of these, with half perceiving that violence to be directly related to their HIV serostatus.18 Indeed, these experiences are interrelated and can become a cycle of violence, HIV risk, and HIV infection (see Figure 2). In this cycle, women who experience IPV are at increased susceptibility for contracting HIV and HIV positive women are at greater risk of experiencing IPV.19,20

Key Policies Addressing Intimate Partner Violence: The ACA and Beyond

Several key policy changes have occurred in recent years that either directly or indirectly address IPV among women with HIV, particularly changes ushered in by the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Policy Changes Under the ACA

The ACA, signed into law in 2010, expanded access to affordable health coverage and reduced the number of uninsured Americans through the creation of federal and state health insurance marketplaces and by expanding the Medicaid program, as well as through other reforms. In addition, there are several provisions that are specifically designed to protect individuals who have experienced IPV, including those with HIV. These include explicit protections in the law, as well as policy enacted through regulatory interpretation and guidance.

- The elimination of pre-existing condition exclusions and premium rate setting based on health status, such as HIV, and other factors, including whether someone is a survivor of IPV. Prior to the ACA, non-group private health insurers could deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions, which could include conditions arising out of acts of domestic violence, such as post-traumatic stress disorder and sexually transmitted infections.21,22 While some states enacted comprehensive IPV related anti-discrimination insurance protections, not all did so. Under the ACA, pre-existing condition exclusions are prohibited and rates are permitted to vary only by age, geographic location, and smoking status. This provision is important for HIV positive domestic violence survivors who in the past could have faced denials or higher rates based on experience of IPV (or use of related health services), their gender, or their HIV status. However, individuals with non-ACA compliant plans, such as short-term limited duration (STLD) plans may be turned down for coverage or charged more if they have a health condition such as HIV or have a history of experiencing IPV (or using health services related to IPV experience).23

- Coverage of a range of no-cost preventive services for women including screening and counseling for IPV. Under the ACA, screening and counseling for IPV is a preventive service that must be covered without cost-sharing by most insurers, including most private health plans and all Medicaid expansion programs, in states that have expanded. While, there is no requirement that traditional state Medicaid programs provide no-cost IPV screenings as part of the state benefit package, they are encouraged to do so – if states choose to cover a suite of preventive services, they can seek a 1% increase in their federal matching rate for those services. As of June 2019, 15 states have elected this opportunity.24 Screening might occur during a routine office visit or well-woman exam and might entail a provider asking a patient about their current and past relationships. The Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) recommends counseling if IPV/DV is disclosed, which can consist of assessing the patient’s safety, referring to mental health services, and providing linkage to support services and resources (Appendix Table 1).25 HIV screening and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), an HIV prevention medication (starting 2021), are also covered preventive services.

- Allowance for married survivors of IPV to file taxes separately from their spouse and claim a premium tax credit. To help make insurance coverage more affordable, the ACA provides advanced premium tax credits to individuals between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level who purchase private insurance through state and federal exchanges. Per the ACA, a married individual needs to file taxes jointly with their spouse to be eligible for premium tax credits which can help make health insurance coverage purchased through a marketplace more affordable. The Department of Treasury and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) issued guidance and subsequent regulations in April and July of 2014 that permit a survivor of IPV living apart from their spouse at the time of tax filing and unable to file a joint return, to claim a premium tax credit while using a married filing separately tax status for up to three consecutive years.26 Allowing survivors to file using this tax status and still obtain premium tax credits is designed to protect them from having to interact with an abuser at tax time while still being able to access insurance subsidies.

- Special Enrollment Period for survivors of IPV. While enrollment in private health plans through the insurance marketplaces must typically occur during a specific open enrollment period in most cases, there are exceptions. Individuals experiencing certain qualifying events, such as a marriage, divorce, or birth of a child, may be granted a Special Enrollment Period (SEP) and permitted to enroll outside of the specified open enrollment window. In 2014, a limited 2-month SEP was created for spousal victims of IPV and their dependents and in 2015 the SEP was extended to include any member of a household who is a victim of intimate partner violence.27 The SEP applies to federally facilitated marketplaces; state-run marketplaces may optionally provide SEPs related to experience of IPV.

- Non-grandfathered plans in the individual and small group markets and Medicaid expansion programs now cover mental health and substance use disorder services as one of ten “essential health benefit” categories. The ACA requires that individual and small group plans, sold both inside and outside the health insurance marketplaces, as well as Medicaid expansion plans, provide ten categories of essential health benefits including among others: ambulatory services; hospitalization; prescription drugs; and of note in this instance, mental health and substance use disorder services. Prior to this requirement, it was estimated that about one-third of those enrolled in individual market products lacked coverage for substance use services and about one in five were without coverage for mental health services.28 In addition, the ACA applies Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 standards to the individual and small group insurance markets which means that these services must now be covered at parity with medical and surgical benefits. Numerous studies have observed an association between IPV and an array of mental health conditions, including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, among others.29,30 People with HIV experience mental health and substance misuse comorbidities at higher rates than the population overall.31,32,33 Similarly, the rate of substance misuse among women experiencing IPV is 26%, compared to 5% among those not experiencing.34 Access to mental health and substance use services, therefore, is an important component of comprehensive health coverage for many people living with HIV and particularly for those dealing with current or past IPV and trauma.

- Maternal and child home visitation program includes focus on domestic violence. A 2013 study of 260 HIV positive women with a mean age of 46, found that 86% of those surveyed were mothers and 31% had children living at home.35 Given that a large share of women with HIV are likely to be parents and that women with HIV are disproportionately affected by IPV, home visits that include opportunities to address domestic violence could be particularly important for this population. The ACA established the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program, a grant program that provides states with resources to respond to the needs of children and families in at risk communities and includes specific opportunities to address domestic violence. The ACA provided the first five years of funding for the program. Participating states are required to demonstrate an improvement in 4 of 6 benchmarks, one of which is a reduction in crime or domestic violence with its performance measure being screening for IPV. In 2018, 82% of MIECHV caregivers were screened for IPV, up from 74% in 2017.36 In February 2018, the Program was allocated $400 million per year through fiscal year 2022 and in September 2018, 56 states, territories, and nonprofit organizations were awarded grants totaling approximately $361 million through the program.37

- Federal grant program to support pregnant teens and women, including those experiencing domestic and sexual violence, established under the Pregnancy Assistance Fund. The ACA also established a competitive grant program for states and tribes to support pregnant and parenting teens and women, allowing states to use funds to provide intervention and support services to pregnant women who are victims of domestic, sexual violence or stalking. The fund is also available to support the provision of assistance and training related to these issues for federal, state, local and other partners. In FY18, 25 grantees were awarded a total of $25 million. Of these, addressing domestic or interpersonal violence is specifically included in the project description provided on HHS.gov for six grantees.38

Other Policy Initiatives

In addition to ACA-related changes, several other policy initiatives could also help address the intersection of HIV and IPV, including:

- Reauthorization of The Violence Against Women Act.39 The Violence Against Women Act, first signed in 1994, dedicated over $1.5 billion in funding towards the investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women and towards “victim’s services,” including, rape crisis centers, battered women’s shelters, and other sexual assault or domestic violence programs. These services are often the resources recommended by providers to those who screen positively for IPV (Appendix Table 1) VAWA has been reauthorized several times, most recently in 2013. The last authorization lapsed and expired in December of 2018. As of August 2019, the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 had been passed by the House, and is awaiting vote by the Senate.

- The National HIV/AIDS Strategy. The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS), unveiled in 2010 under President Obama and updated in 2015 through 2020, has goals of reducing new HIV infections, increasing access to care and improving health outcomes for those living with HIV, reducing HIV-related disparities and health inequities, and achieving a more coordinated national response to the HIV epidemic. In order to reduce new HIV infections, NHAS recommends a combination of evidence-based approaches, including supporting and strengthening patient-centered IPV screening and linkage to services (housing, education, employment) for those who screen positively. To address the challenge posed by IPV for accessing and adhering to stable care, the NHAS suggests that a trauma-informed approach to care, which seeks to minimize the chances of re-traumatizing those who are trying to heal, may be applicable in an HIV care setting. The Trump administration is currently working on an updated version of the NHAS but it is not yet known whether addressing IPV will feature in the strategy.

- “Ending the HIV Epidemic” Initiative In February of 2019, President Trump announced a new initiative with the goal of ending the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.40 The Ending the HIV Epidemic proposal requests $291 million in the FY 2020 budget to begin the multiyear initiative. Although the plan does not specifically outline funding for those experiencing IPV or those with HIV at risk for IPV, the plan does aim to reduce new infections by 90% by 2030. Substantial localized planning will occur within the 48 counties, 7 states, Washington, D.C., and San Juan, Puerto Rico targeted in year one of the initiative. It is possible that addressing IPV as part of “ending HIV” strategy will feature to varying degrees across jurisdictions which will be charged with developing their own plans to reach the initiative’s goals.

- Funding to address the intersection of IPV & HIV among women.41 In December 2019, the Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office on Women’s Health (OWH) awarded new funding to community based organizations to “provide a community-level focus on the prevention of, screening for, and response to IPV and its intersection with HIV infection.” Awards totaling $3.1 million were provided to four organizations, each located in one of the jurisdictions prioritized in the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, TX, University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, TX, The Center for Women and Families, , in Louisville, KY, and the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies, in New Orleans, LA.

- Funding to provide HIV positive domestic violence survivors with housing. As part of a demonstration project, in 2016 the Departments of Justice and Housing and Urban Development awarded $9.2 million to eight local programs to provide stable housing to HIV positive survivors of domestic violence in an effort to prevent homelessness.42

Looking Ahead

Addressing trauma and violence experienced by women with and at risk for HIV aims to provide care and support in the immediate term, but in the longer term, may also be an important contribution in combating the HIV epidemic. Key policy changes, including those ushered in by the ACA and other opportunities outlined above, provide important vehicles for targeted interventions to address IPV in HIV positive and at risk women.

Despite these policy changes, several challenges remain. With respect to screening and counseling for IPV, as with all preventive services, coverage does not necessarily equate with uptake by consumers or with the service being offered by providers. Inclusion of IPV/DV screening as a reimbursable service and the associated federal and advisory body recommendations may drive up some provision of the intervention but additional efforts may be necessary to generate more widespread provider led screenings. A 2017 study found that just 27% of reproductive age women have discussed IPV with a provider recently, demonstrating that these screenings are still relatively rare.43 (See Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) for a compilation of IPV screening tools.) In addition, maintaining confidentiality for women seeking violence-related care can sometime be a challenge and create barriers to access. Private insurance plans typically send an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) that documents provided services to the principal policy holder which may deter women from accessing services. In addition, mandated reporting of IPV in many states, including requirements for providers to file police reports or reports with a public health department or other state entity, may also deter women from seeking services.44 Beyond these challenges related to IPV more generally, there is also a need to raise awareness among providers and women at risk for and living with HIV about the interrelatedness between HIV and intimate partner violence.

Finally, as states make different policy decisions, particularly around the ACA, opportunities for enrollees vary across the nation. For example, whether states with state based marketplaces decided to implement the SEP for victims of IPV discussed above is one such policy decision. Additionally, states are still making decisions about whether to expand their Medicaid program to all those below 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (currently 37 states (including DC) have expanded), and this has significant implications for access to coverage for low-income individuals. Given that multiple studies have demonstrated that HIV and IPV both trend with poverty, access to Medicaid expansion, including the associated IPV screening, could play a particularly important role for these populations.45 In addition, access to services, varies by coverage and as noted, IPV screening is not a required covered service for those in traditional Medicaid.

Key provisions under the ACA as well as other policy developments discussed above could present significant opportunities to address IPV, for both women living with HIV as well as those at risk. At the same time, efforts to eliminate all or parts of the ACA could remove many of these protections.