COVID-19 Risks and Impacts Among Health Care Workers by Race/Ethnicity

Summary

Health care workers face potential COVID-19 exposure through their job. Data suggest that at least 200,000 health care workers have been infected with coronavirus as of November 2020, but this estimate likely vastly underestimates the number affected due to major gaps in data collection. Data further show that people of color account for the majority of COVID-19 cases and deaths known among health care workers, and that they are more likely to be in health care worker roles and settings that have particularly high risks of workplace exposure. This analysis provides greater insight into COVID-19 risks and impacts among health care workers and how they vary by race and ethnicity. It is based on a KFF analysis of 2019 American Community Survey and publicly available information on COVID-19 impacts among health care workers (see Methods for more details). It finds:

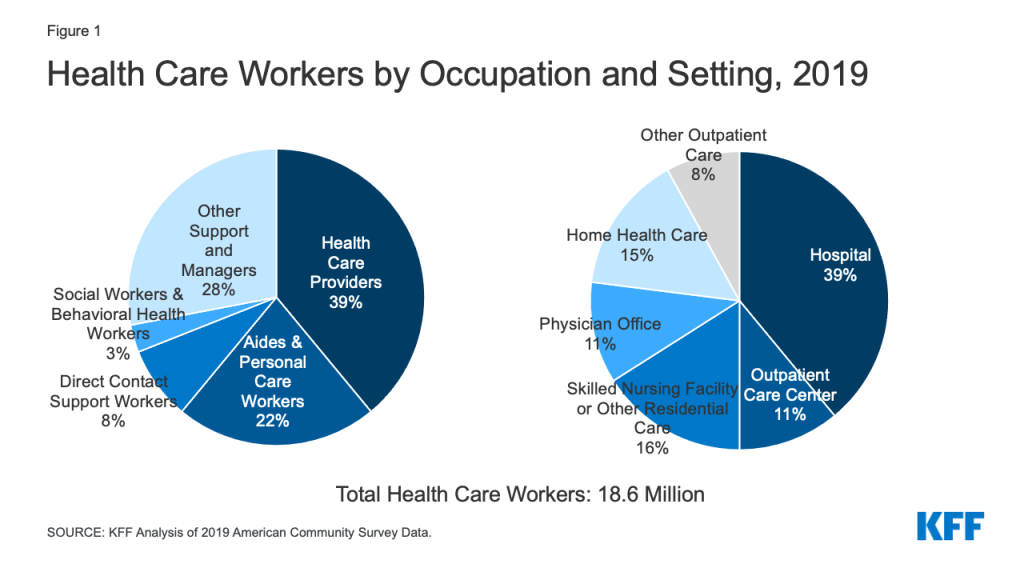

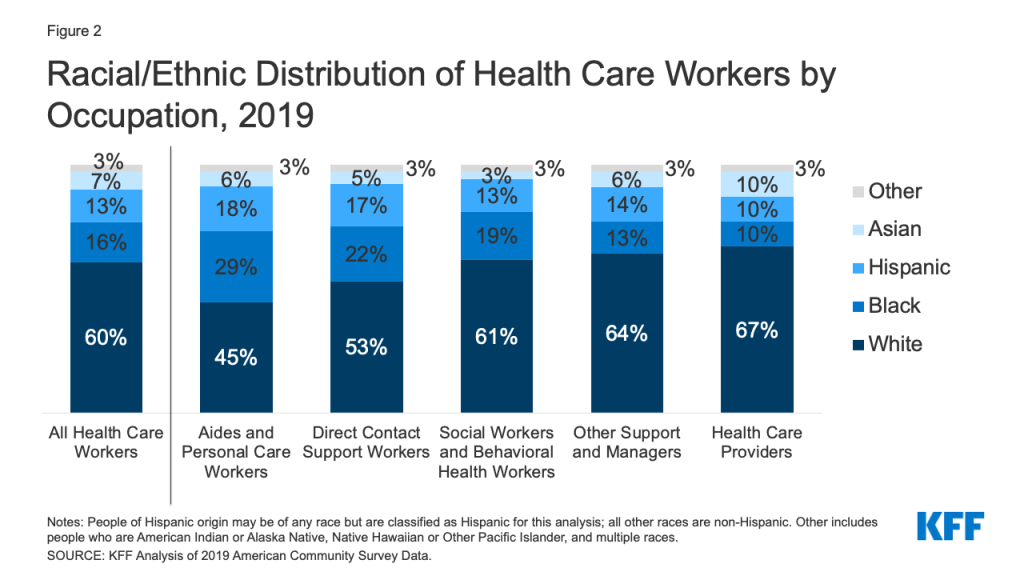

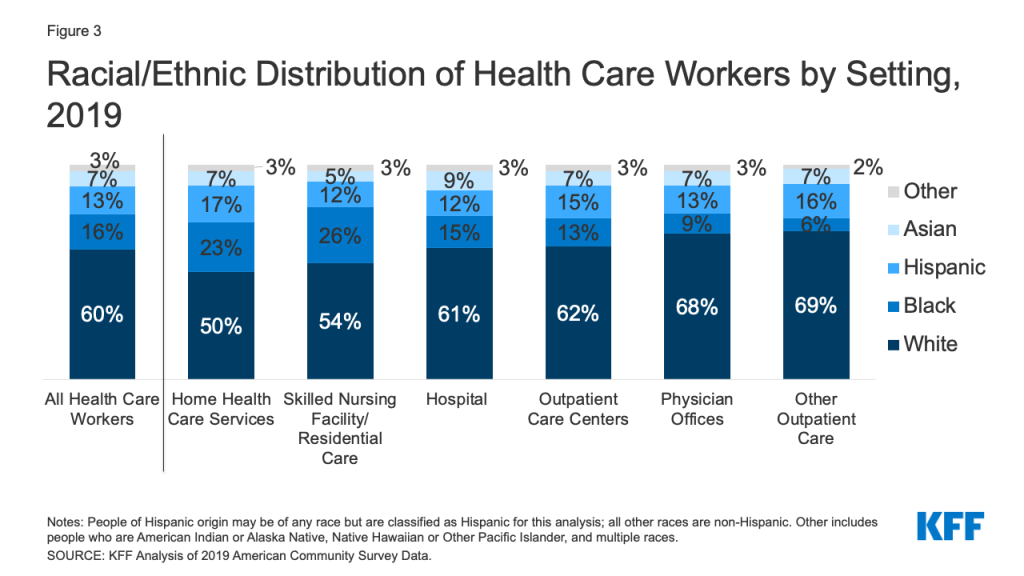

In 2019, there were over 18.6 million people working in the health care industry across a range of occupations and settings. Overall, 60% of health care workers were White and 40% were people of color, including 16% who were Black, 13% who were Hispanic, and 7% who were Asian. However, the racial/ethnic composition of health care workers varied across occupations and settings. Black and Hispanic health care workers made up relatively larger shares of aides and personal care workers and direct contact support workers. Black and Hispanic workers also accounted for larger shares of health care workers in home health care, and Black workers made up a relatively larger share of workers in skilled nursing facility or other residential care settings.

People of color account for the majority of COVID-19 cases and/or deaths known among health care workers for which race/ethnicity data are available. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 200,000 cases and just over 790 deaths among health care personnel as of November 9, 2020. However, this estimate likely vastly underestimates the number of health care workers affected as health care personnel status was known for only a quarter (25%) of total cases. CDC further found that, as of July 2020, more than half (53%) of confirmed cases among health care personnel were among people of color, including 26% who were Black, 12% who were Hispanic, and 9% who were Asian. Data collected by states, the media, and other organizations similarly find that people of color account for the majority of COVID-19 cases and/or deaths known among health care workers.

Research suggests that health care workers face increased risks of coronavirus exposure and infection, with certain health care workers facing particularly high risks that disproportionately affect people of color. Studies show that health care workers are at increased risk for exposure and infection relative to the general population, with particularly high risks for health care workers who provide direct patient care, work in inpatient hospital or residential or long-term care settings, are in nursing or direct support staff roles, or do not have adequate access to PPE.1 Research further suggests that, among health care workers, people of color are more likely to report reuse of or inadequate access to PPE and to work in clinical settings with greater exposure to patients with COVID-19. CDC analysis of antibody evidence of previous infection among health care personnel further found higher rates of seropositivity among people or color compared to their White counterparts (9.7% vs. 4.4%), suggesting higher rates of previous infection.

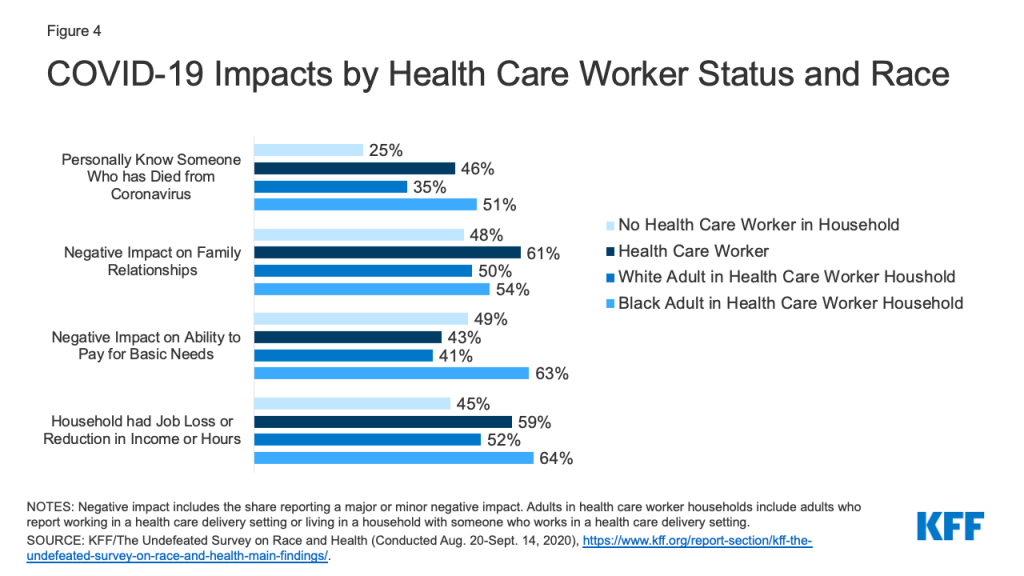

A recent KFF/The Undefeated Survey suggests that the pandemic is taking a disproportionate toll on health care workers, especially Black health care workers and their families. It finds that health care workers are more likely than others to worry about being exposed to the virus through the workplace, to know someone who has died from the virus, to say it has negatively impacted family relationships, and to report someone in their household lost a job or experienced a cutback in hours or income due to the pandemic. Black health care workers and their families are particularly likely to report certain impacts, including knowing someone who has died from the virus and a negative impact on their ability to pay for basic needs.

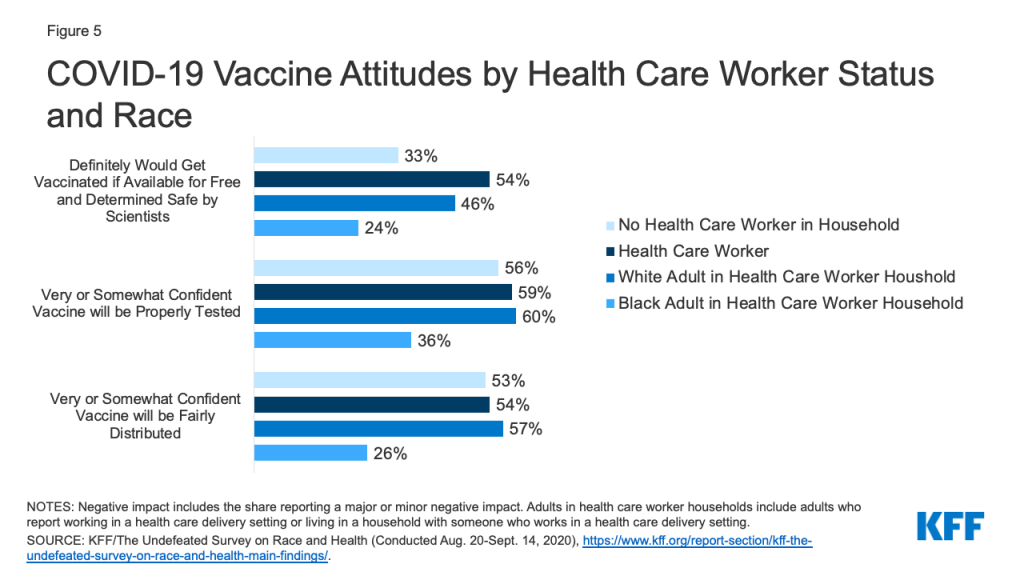

KFF/The Undefeated Survey data also show that, while health care workers are more likely than others to say they would definitely get a COVID-19 vaccine, substantial shares express vaccine hesitancy, particularly among Black health care workers and their families. Overall, 54% of health care workers say they would definitely get vaccinated if it was available for fee and determined safe and effective by scientists, compared to 33% of adults who do not have a health care worker in their household. However, among adults who are health care workers or who live in a household with a healthcare worker, Black adults are much less likely to say they would definitely get vaccinated compared to White adults (24% vs. 46%), mirroring greater vaccine hesitancy among Black adults more broadly.

Together these findings highlight the importance of focusing on health care workers as part of response efforts to help protect against COVID-19 infection and spread. They can also help target response efforts and distribution of treatments and vaccines as they become available to prioritize health care workers who are facing the highest risks of exposure and infection. Targeting these efforts will also have important implications for health disparities given the disproportionate risks and impacts among health care workers who are people of color, which may compound broader increased health and economic risks that are contributing to the pandemic’s disproportionate toll on people of color overall. This analysis also shows that there remain significant gaps in data to understand COVID-19 impacts by industry and occupation. Increased data would allow for better understanding of work-related risks and outbreaks to help guide response efforts and resources going forward.

Issue Brief

Overview of Health Care Workers

As of 2019, there were over 18.6 million people working in the health care industry. Health care workers face potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 through their job, but this risk may vary based on the type and setting of their work. Overall, nearly four in ten (39%) health care workers were health care providers such as nurses, physicians, technicians, and therapists; 22% were aides and personal care workers, such as certified nursing assistants, home health aides, and medical assistants; 8% were direct contact support workers, such as housekeeping and kitchen and cafeteria staff; and 3% were social workers and behavioral health workers (Figure 1). The remaining 28% were other support workers and managers, such as office and administrative managers and staff, who may have less direct contact with patients. Nearly four in ten (39%) worked in a hospital, 16% worked in a skilled nursing facility or other residential care, 11% worked in an outpatient care center, 11% worked in a physician office, 15% worked in home health care, and the remaining 8% worked in other health care service settings such as a dentist, optometrist or chiropractor offices.

The racial/ethnic make-up of health care workers varied by occupation and health care setting. Overall, 60% of health care workers were White and 40% are people of color, including 16% who were Black, 13% who were Hispanic, and 7% who were Asian. However, Black and Hispanic health care workers made up relatively larger shares of aides and personal care workers and direct contact support workers and accounted for fewer health care providers (Figure 2). Similarly, Black and Hispanic workers made up larger shares of health care workers in home health care (23%), and Black workers accounted for over a quarter of workers in skilled nursing facility or other residential settings (26%) (Figure 3).

COVID-19 Among Health Care Workers

Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths

Some federal, state, and other data are available on COVID-19 infections and deaths among health care workers, but significant data gaps remain:

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 200,000 cases and just over 790 deaths among health care personnel as of November 9, 2020. However, health care personnel status was only known for less than a quarter of total cases, and death status was available for less than three-quarters of cases among health care personnel.

- KFF review of state websites identified 16 states reporting over 144,000 COVID-19 cases among health care workers as of November 2020.2 However, states varied widely in how they defined and identified health care workers. Further, in most cases, it was not clear what share of total cases had health care worker status known. Some counties also report data for health care workers. For example, Los Angeles County reported over 17,000 positive cases and 105 deaths among health care workers and first responders as of October 29, 2020.

- Media and other organizations have also undertaken efforts to track COVID-19 deaths among health care workers. For example, reporting by Kaiser Health News and the Guardian has identified over 1,300 likely deaths among health care workers related to COVID-19 as of November 9, 2020. National Nurses United estimated that, as of September 16, 2020, 1,718 health care workers, including 213 registered nurses, had died of COVID-19 and related complications based on media reports, social media, obituaries, union memorials, federal and state reporting, and internal reporting.

These data likely underestimate COVID-19 impacts among health care workers given that the majority of cases and deaths are missing information on health care worker status. CDC analysis of antibody evidence of previous infection further suggests that a high proportion of COVID-19 infections among health care personnel go undetected.

People of color accounted for a majority of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths known among health care workers for which race/ethnicity data is available. CDC found that, as of July 2020, more than half (53%) of confirmed cases among health care personnel were among people of color, including 26% who were Black, 12% who were Hispanic, and 9% who were Asian. Separate CDC analysis of hospitalization data, found that most health care personnel hospitalized with COVID-19 were people of color, including over half (52%) who were Black and nearly 9% who were Hispanic. Data from Los Angeles County show that, among the over 17,000 health care workers and first responders who were identified as positive for COVID-19 as of late October 2020, 50% were Hispanic, 15% were Asian, and 7% were Black. Moreover, among the 105 health care workers and first responders who died, 45% were Hispanic and 37% were Asian. Kaiser Health News and the Guardian tracking of health care worker deaths associated with COVID-19 further finds that a majority of deaths were among people of color. Similarly, National Nurses United found that over half (58%) of the 213 registered nurses it had identified as dying due to COVID-19 and related complications were nurses of color, including nearly a third (32%) who were Filipino nurses and 18% who were Black nurses.

Risks of Exposure and Infection

Analysis suggests health care workers are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection relative to the general population and that certain health care workers are at particularly high risk. A United States and United Kingdom study found higher prevalence of COVID-19 infections among frontline health care workers (i.e., those who reported direct patient contact) compared to the general community, with the highest risks for those working in inpatient hospital settings and nursing homes, reporting inadequate personal protective equipment (PPE), and caring for patients with documented COVID-19. CDC analysis of health care providers in Minnesota found that two-thirds (66%) of higher-risk exposures to COVID-19—defined as close contact for 15 minutes or more or during an aerosol-generating procedure—involved direct patient care, while roughly one-third (34%) were through nonpatient contacts, such as interactions with coworkers and social or household contacts. It also found that health care personnel working in congregate living or long-term care settings, including skilled nursing facilities, were less likely to wear appropriate PPE, worked more often while symptomatic, and were more likely to test positive following a higher-risk exposure compared to those working in acute care settings. Other CDC analysis found that more than two-thirds (67%) of health care personnel who were hospitalized with COVID-19 were in roles that likely required direct patient contact, and over one-third (36%) were in nursing-related occupations. Similarly, Kaiser Health News and the Guardian tracking of COVID-19 deaths among health care workers found that nurses and support staff accounted for the largest numbers of deaths.

Research further suggests that, among health care workers, people of color are more likely to face elevated risks of workplace exposure. As noted earlier, Black and Hispanic workers make up relatively larger shares of aides and personal care workers and direct contact support workers who typically are engaged in direct patient care, which is associated with increased risk of infection. Moreover, Black workers make up over a quarter of workers in skilled nursing facility or other residential settings, which pose higher risks of infection and have been sources of a significant share of cases. The United States and United Kingdom study also found that, among frontline health care workers, people of color were at especially high risk of infection and were disproportionately likely to report reuse of or inadequate access to PPE and to work in clinical settings with greater exposure to patients with COVID-19. Further, it found that Black, Asian, and other frontline workers of color had increased risk of a positive COVID-19 test compared to their White counterparts. CDC analysis of antibody evidence of previous infection among health care personnel also found higher rates of seropositivity among people or color compared to their White counterparts (9.7% vs. 4.4%), suggesting higher rates of previous infection.

Health and Financial Impacts of the Pandemic

A recent KFF/The Undefeated Survey suggests that the pandemic is taking a disproportionate toll on health care workers, especially among Black health care workers and their families. Health care workers were more likely than adults who live in a household without any health care workers to be worried that they might be exposed to coronavirus at work (67% vs. 50%), to personally know someone who has died from coronavirus (46% vs. 25%), and to say the pandemic has had a negative impact on their relationships with family members (61% vs. 48%) (Figure 4). Health care workers also were more likely than adults living in a household without a health care worker to say that someone in their household has lost a job, been placed on furlough, or had their hours or income reduced as a result of the pandemic (59% vs. 45%), but they were not more likely to say it had a negative impact on their ability to pay for basic needs (43% vs. 49%). Among adults who are health care workers or who live in a household with a health care worker, Black adults were more likely compared to their White counterparts to report knowing someone who has died from coronavirus (51% vs. 35%) and to say that the pandemic negatively affected their ability to pay for basic necessities (63% vs. 41%).

COVID-19 Vaccine Attitudes

The KFF/The Undefeated survey also found that health care workers are more likely than others to say they would definitely take a vaccine if it was available for fee and determined safe and effective by scientists, but there are still substantial shares who say they would probably or definitely not get vaccinated, particularly among Black adults. Overall, 54% of health care workers say they would definitely get vaccinated, compared to 33% of adults who do not have a health care worker in their household (Figure 5). However, among adults who are health care workers or who live in a household with a healthcare worker, Black adults are much less likely to say they would definitely get vaccinated compared to White adults (24% vs. 46%), mirroring greater vaccine hesitancy among Black adults more broadly. Among health care workers and their family members, Black adults also express less confidence that a vaccine will be tested properly and distributed fairly compared to their White counterparts.

Implications

Health care workers face risk of COVID-19 exposure through their workplace. Data provide some estimates of cases and deaths among health care workers and show that people of color account for the majority of health care workers affected by COVID-19. However, the data likely vastly underestimate impacts among health care workers. Research suggests that health care workers are at increased risk of exposure and infection compared to the general population and that most high-risk exposures among health care workers occur through the workplace. However, risks are not equally shared across health care workers. Analysis suggests that frontline workers providing direct care in certain settings and those with inadequate access to PPE face particularly high risks. Moreover, among health care workers, people of color are more likely to face these elevated workplace risks, which may compound broader increased health and economic risks that are contributing to the pandemic’s disproportionate toll on people of color.

Together these findings highlight the importance of focusing on health care workers as part of response efforts to help protect against infection and spread. They can also help target response efforts and distribution of treatments and vaccines as they become available to prioritize health care workers who are facing the highest risks of exposure and infection. Targeting these efforts will also have important implications for health disparities given the disproportionate risks and impacts among health care workers who are people of color. This analysis also shows that there remain significant gaps in data to understand COVID-19 impacts by industry and occupation. Increased data would allow for better understanding of work-related risks and outbreaks to help guide response efforts and resources going forward.

Methods

This analysis is based on KFF analysis of the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), 1-year file. The ACS includes a 1% sample of the US population, the subset used here includes over 170,000 observations. The health care industry is defined as industry codes 7970 through 8290, and does not include the childcare or vocational training industries. For more information see here.

| Industry Classification | ||

| Industry Code | Title | Classification |

| 7970 | Offices of physicians | Offices of physicians |

| 7980 | Offices of dentists | Other Outpatient |

| 7990 | Offices of chiropractors | Other Outpatient |

| 8070 | Offices of optometrists | Other Outpatient |

| 8080 | Offices of other health practitioners | Other Outpatient |

| 8090 | Outpatient care centers | Outpatient care centers |

| 8170 | Home health care services | Home health care services |

| 8180 | Other health care services | Home health care services |

| 8191 | Hospital | General or MH Hospital |

| 8192 | Psychiatric and substance abuse hospitals | General or MH Hospital |

| 8270 | Skilled nursing facilities | SNF & Care Facility |

| 8290 | Residential care facilities | SNF & Care Facility |

We define the healthcare workforce as all individuals who earned at least $1,000 during the year and indicated that their job was in one of the industry codes listed above. Within these industry groups, we grouped people’s occupations into five different categories based on type of work and level of contact with patients:

- Aides and personal care workers includes certified nursing assistants (CNAs), personal care aides, home health aides, licensed practical nurses (LPNs), OT and PT assistants, medical assistants, and other aides.

- Direct contact support workers includes non-clinical support staff, such as housekeeping and janitorial staff, kitchen and cafeteria staff, recreation workers, laundry workers, security guards, shuttle drivers, clergy, and first-line supervisors of support workers.

- Health care providers includes registered nurses (RNs), physicians, dental assistants, physician therapists, occupational therapists, nurse practitioners, dentist, radiologist, phlebotomists, and various types of technicians that provide direct patient care.

- Other support workers and managers includes office and administrative managers and staff, receptionists, nutritionists, laboratory technicians, office clerks, billing clerks, medical records specialist, human resources, groundskeeping and facilities workers, who are likely to come into regular direct contact with patients less often than other types of health care workers.

- Social Workers and Behavioral health workers includes health professions such as Social workers, Mental health counselors and substance abuse counselors

Note, that this analysis only includes those in the healthcare industry, therefore healthcare professionals working in other care settings, such as school nurses are not included.

Endnotes

- Long H. Nguyen et al., “Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study,” The Lancet 5, no. 9 (September 2020): 475-483, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30164-X/fulltext; . Ashley Fell et al., “SARS-CoV-2 Exposure and Infection Among Health Care Personnel — Minnesota, March 6–July 11, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, no. 43 (October 2020): 1605-1610, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6943a5.htm?s_cid=mm6943a5_w; . Anita K. Kambhampati et al., “COVID-19–Associated Hospitalizations Among Health Care Personnel — COVID-NET, 13 States, March 1–May 31, 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 69, no. 43 (October 2020): 1576-1583) https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6943e3.htm?s_cid=mm6943e3_w; . “Lost on the Frontline,” The Guardian, accessed November 9, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2020/aug/11/lost-on-the-frontline-covid-19-coronavirus-us-healthcare-workers-deaths-database ↩︎

- States reporting COVID-19 cases among health care workers include: AL, AR, CO, GA, ID, MA, MN, NH, OH, OK, OR, SC, UT, VT, VA, and WA. Dates for which cases are reported through vary across states. Total cases among Colorado health care workers includes confirmed COVID-19 cases among staff in any health care setting, based on active and resolved outbreak data. ↩︎