Asian Immigrant Experiences with Racism, Immigration-Related Fears, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Summary

Asian immigrants have faced multiple challenges in the past year. There has been a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, driven, in part, by inflammatory rhetoric related to the coronavirus pandemic, which has spurred the federal government to make a recent statement condemning and denouncing acts of racism, xenophobia, and intolerance against Asian American communities and to enact the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act. At the same time, immigrants living in the U.S. have experienced a range of increased health and financial risks associated with COVID-19. These risks and barriers may have been compounded by immigration policy changes made by the Trump administration that increased fears among immigrant families and made some more reluctant to access programs and services, including health coverage and health care. Although the Biden administration has since reversed many of these policies, they may continue to have lingering effects among families.

Limited data are available to understand how immigrants have been affected by the pandemic, and there are particularly little data available to understand the experiences of Asian immigrants even though they are one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the U.S. and are projected to become the nation’s largest immigrant group over the next 35 years. To help fill these gaps in information, this analysis provides insight into recent experiences with racism and discrimination, immigration-related fears, and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among Asian immigrant patients at four community health centers.

The findings are based on a KFF survey with a convenience sample of 1,086 Asian American patients at four community health centers. Respondents were largely low-income and 80% were born outside the United States. The survey was conducted between February 15 and April 12, 2021. Key findings include:

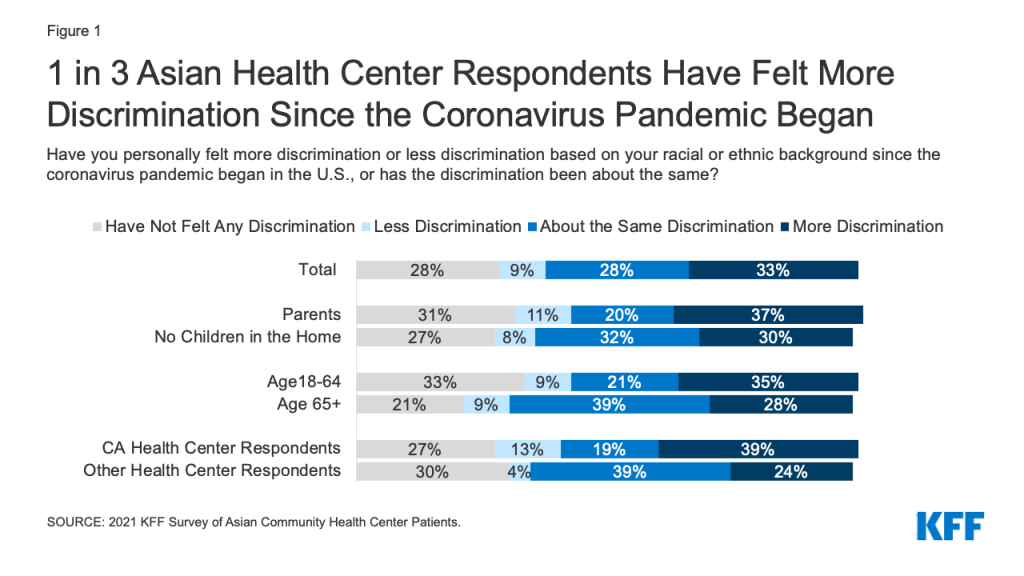

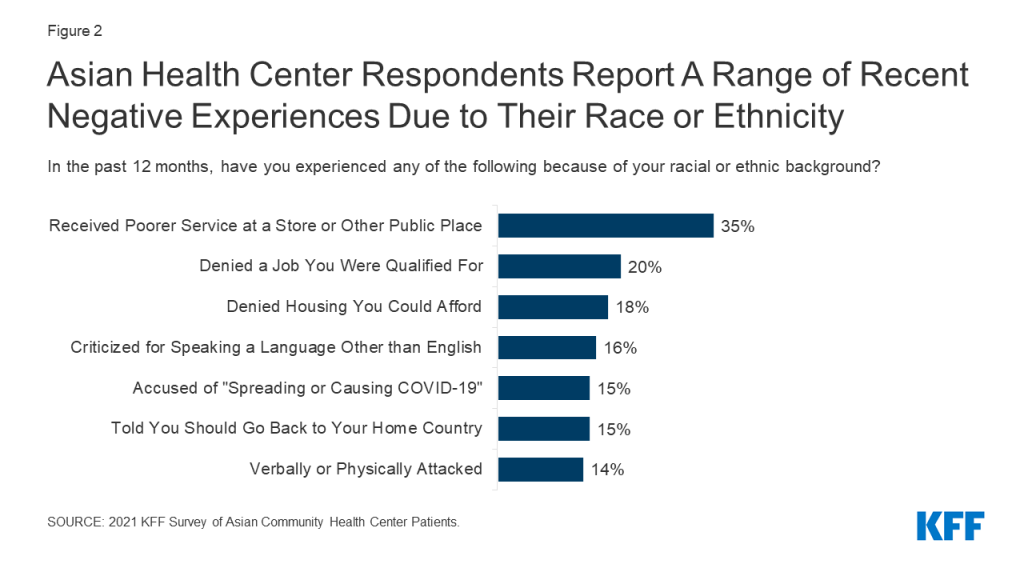

- One in three (33%) respondents report that they have personally felt more discrimination based on their racial/ethnic background since the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S. Asian health center respondents report facing a range of negative experiences due to their racial or ethnic background over the past 12 months, including 14% who say they experienced a personal verbal or physical attack due to their race/ethnicity.

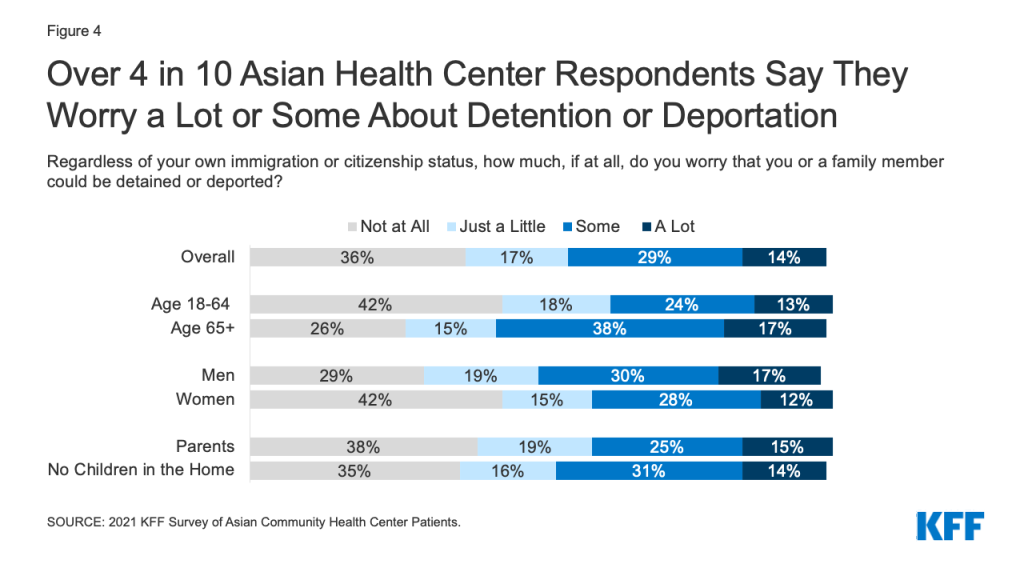

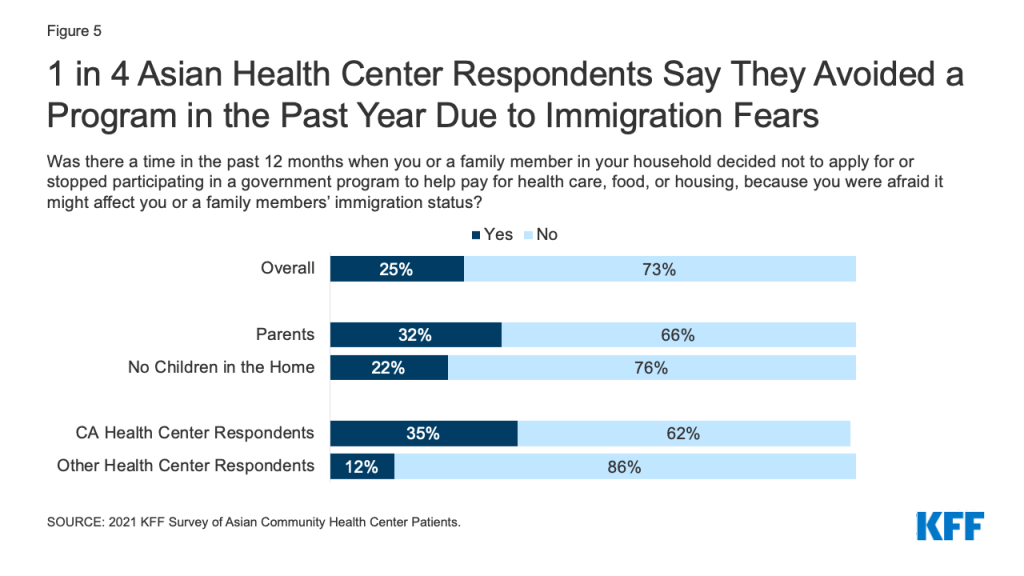

- Many respondents have immigration-related fears, and most say they don’t have enough information about how recent immigration policy changes affect their family. Over four in ten (44%) Asian health center respondents say they worry a lot or some that they or a family member could be detained or deported. One quarter (25%) say they or a member of their household did not apply for or stopped participating in a government program to help pay for health care, food, or housing in the past year due to immigration-related fears. Over half (54%) say they do not have enough information about how recent changes to U.S. immigration policy might impact them or their family.

- Asian health center respondents report negative health and financial impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic. Nearly half (48%) of respondents say the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected their ability to pay for basic needs like housing, utilities, and food, and over half (54%) say someone in their household experienced job or income loss due to the pandemic. Over four in ten (43%) report negative effects on their mental health.

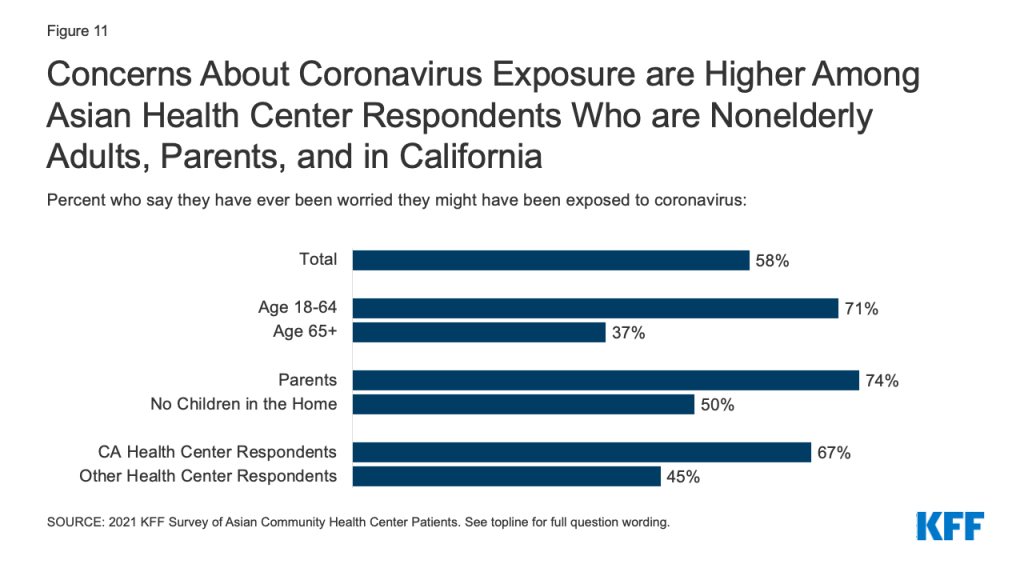

- Nearly six in ten (58%) respondents say they have worried at some point that they have been exposed to coronavirus. Most (60%) of those who worried about being exposed say they have been tested for the virus. Among those who worried about exposure but say they have not been tested, the most frequently cited reasons for not getting tested were thinking they could isolate at home (31%) or not knowing where to get tested (26%). Some also say concerns about costs (13%), effects on ability to work (12%), and fears of negative impacts on their or a family member’s immigration status (10%) are reasons for not getting tested. The large majority of Asian health center patients who responded say they are willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine, with nearly two in three (64%) wanting to get it as soon as possible at the time the survey was fielded.

Approach

The findings in this report are based on responses from a convenience sample of Asian patients at four community health centers. KFF worked with the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations (AAPCHO) and community health center staff to develop and field the survey. Because the survey is based on a convenience sample, the findings are not generalizable to a broader population and cannot be benchmarked against other population-based surveys. Respondents are limited to four locations and may be lower income than Asian immigrants overall as they are patients of federally qualified health centers serving a predominantly low-income population. Further, as patients of a community health center, respondents are connected to a source of health care. Despite these limitations, the findings increase the knowledge base for understanding Asian immigrant experiences, which remains very limited. (See Methods for more details.)

The health centers that fielded the survey serve a predominantly Asian, low-income population that likely includes many immigrants. Four health centers fielded the survey: Asian Health Services in Alameda County, CA; North East Medical Services, in San Francisco, CA; HOPE Clinic in Houston, TX; and International Community Health Services (ICHS) in King County, WA. Overall, 79% of patients at these health centers identify as Asian; over 87% have income below 200% of the federal poverty level, including 54% who have income below poverty; and 12% are uninsured.1 Health centers do not collect information on patient immigration status, but nearly seven in ten patients at these health centers are best served in a language other than English.2

Mirroring the patient populations served by the health centers, respondents include Asian American patients who are largely low-income and born outside the United States. Overall, a total of 1,086 survey respondents self-identify as Asian patients of one of the health centers. Among Asian patient respondents, over six in ten (62%) identify as Chinese and roughly one in five (18%) identify as Vietnamese, with the remaining respondents representing a broad range of ethnic backgrounds. Eight in ten (80%) report that they were born outside the U.S. The remaining share report they were U.S.-born; however, these respondents may have an immigrant family member living in their household as many express immigration-related concerns in their survey responses. Over seven in ten (72%) respondents report total annual family income below $40,000, and 15% report they were uninsured.

Respondents include a larger share of patients age 65 or older compared to the total patient population served by the health centers. Nearly four in ten respondents (39%) are age 65 or older compared to 20% among the total patient population of the health centers. The higher share of respondents age 65 or older reflects that the health centers fielded the survey during the time they began COVID-19 vaccination efforts, which were initially focused on people in this age group.

Over half of respondents (57%) are patients at either of the two California-based health centers, while about a third (32%) are patients with ICHS in Washington state, and 11% are patients at HOPE clinic in Texas. California health center respondents are more likely than other health center respondents to be under age 65 (69% vs. 51%) and less likely to have lower household income (<$40,000 per year) (65% vs. 80%). They also are more likely to be Chinese (71% vs. 49%) and less likely to be Vietnamese (13% vs. 24%).

Given that the respondents are older than the overall patient population for these health centers, we examine findings by age to identify key differences in experiences of adults ages 18-64 and those ages 65 and older. In addition to comparing findings by age group, we also examine differences between California health center respondents vs. other health center respondents. The data allowed for comparisons between California health center respondents and other health center respondents, but the ability to make comparisons for Washington and Texas, specifically, was limited due to sample size restrictions. In addition, we highlight differences by gender and parental status (i.e., whether respondents are parents or guardians of children under age 18 living in their household). We also identify differences between Chinese and Vietnamese respondents; comparisons for other ethnicities were not possible due to sample size restrictions. All differences mentioned in the brief are significant at the .05 level.

Findings

Experiences with Racism and Discrimination

One in three (33%) Asian health center respondents say they have personally felt more discrimination based on their racial/ethnic background since the COVID-19 pandemic began in the U.S (Figure 1). Roughly three in ten indicate that they have not felt any discrimination (28%) or that they have felt about the same level of discrimination (28%), while less than one in ten (9%) report less discrimination.

The share reporting more discrimination since the pandemic began is somewhat higher among parents (37%) than those without children in the home (30%) and among adults under age 65 (35%) compared to adults over age 65 (28%). Chinese respondents are more likely than Vietnamese respondents to say that they have felt about the same level of discrimination since the start of the pandemic (30% vs. 19%) but less likely to say they have felt no discrimination (28% vs. 36%). Those who are 65 or older are more likely than those under age 65 to say that the amount of discrimination they feel has not changed, while those under age 65 are more likely to say they have not felt any discrimination since the pandemic began. California health center respondents are more likely to report both more and less discrimination since the start of the pandemic compared to those in other locations (Texas and Washington), while those in other locations are more likely to say they have felt the same level of discrimination.

Asian health center respondents say they have faced a range of negative experiences due to their racial or ethnic background over the past 12 months, including verbal and physical attacks. Over one in three (35%) report receiving poorer service than other people due to their racial or ethnic background at a store or other public place, one in five (20%) say they have been being denied a job for which they were qualified, and 18% report being denied housing they could afford. Others report more personal attacks based on their race/ethnicity, including 16% who say they were criticized for speaking a language other than English in public, 15% who say they have been accused of “spreading or causing COVID-19” or were told that they should go back to their home country, and 14% who say they were verbally or physically attacked (Figure 2).

Those who are age 65 or older are more likely to say they have received poorer service (44% vs. 30%) or been denied housing (30% vs. 11%) or a job (27% vs. 16%) based on their race/ethnicity compared to younger respondents, and men are more likely than women to report receiving poorer service (41% vs. 32%) and being denied housing (22% vs. 15%) (Figure 3). Similarly, respondents without children in the home were more likely than parents to report housing discrimination (21% vs. 13%). California health center respondents were less likely to say they experienced discrimination in housing (11% vs. 27%) or jobs (18% vs. 23%) compared to those of other health center locations (Washington and Texas).

Over four in ten (42%) Asian health center respondents say they have been criticized for wearing a mask since the pandemic began in the U.S., while 13% say they have been criticized for not wearing a mask. There are some variations in experiences among respondents. For example, higher shares of those age 65 and older say they have been criticized for wearing a mask compared to those who are younger (57% vs. 32%) and men are more likely to say they have been criticized for mask wearing than women (47% vs. 38%). Respondents without children in the home also are more likely than parents to report being criticized for wearing a mask (48% vs. 29%). There are also variations in experiences by location, with California health center respondents less likely than those in other locations to report being criticized for wearing a mask (30% vs. 57%) and more likely to say they have been criticized for not wearing one (16% vs. 7%).

Immigration-Related Fears

Over four in ten (44%) Asian health center respondents say they worry a lot or some that they or a family member could be detained or deported (Figure 4). Worries are higher among those age 65 or older, men, and those without children in the home, compared to those who are under age 65, women, and parents. Among parents, three in ten (30%) say their children have worries or fears that they or a family member might be detained or deported. Although there is no significant difference in their own levels of worry about detention or deportation by location, parents who are California health center respondents are more likely to say their children are concerned about a family member being detained or deported than parents in other locations (39% vs. 12%).

One quarter (25%) of respondents say they or a member of their household decided not to apply for or stopped participating in a government program to help pay for health care, food, or housing in the past year due to immigration-related fears (Figure 5). Overall, nearly one in five (17%) say they did not apply for or stopped participating in a program that helps with housing, 12% for a program that helps with food, and 10% for a program that helps pay for health care. The shares who say they did not apply for or stopped participating in a program are higher among parents (32%) and respondents at California health centers (35%). However, parents also are more likely than those without children in the home to say they have received any type of government assistance to pay for things like housing, food, or health insurance in the past year (53% vs. 34%), as are California health center respondents compared to those in other locations (48% vs. 29%).

Over half of (54%) respondents say they do not have enough information about how recent changes to U.S. immigration policy might impact them or their family (Figure 6). Chinese respondents are more likely than Vietnamese respondents to say they do not have enough information (59% vs. 41%).

Asian health center respondents report relying on a variety of sources for information on immigration policy. The most frequently cited sources that they relied on very or somewhat often were television and radio in their native language (59%) followed closely by friends and families (56%) and social media (56%). Over half (51%) report relying on newspapers in their native language, and nearly half said they rely on English television and radio (44%) or English newspapers (40%) very or somewhat often. About four in ten report turning to nonprofit organizations (36%) or the government (34%) for this information, while over one in three said they rely on religious organizations (34%) or an attorney (32%).

In general, respondents age 65 or older are more likely to report using all sources of information very or somewhat often compared to their younger counterparts, except for social media or close family or friends. In addition, those without children in the home and men are more likely to report frequent use of certain information sources than parents and women, particularly English language television, radio, and newspapers. California health center respondents are less likely than those of other health centers to report frequent use of certain sources of information, including English language television and radio (16% vs. 35%), English language newspapers (10% vs. 27%), native language television or radio (21% vs. 30%), a nonprofit organization (6% vs. 13%), a religious organization or church (7% vs. 13%), government sources (5% vs. 20%), or an immigration attorney (5% vs. 25%).

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

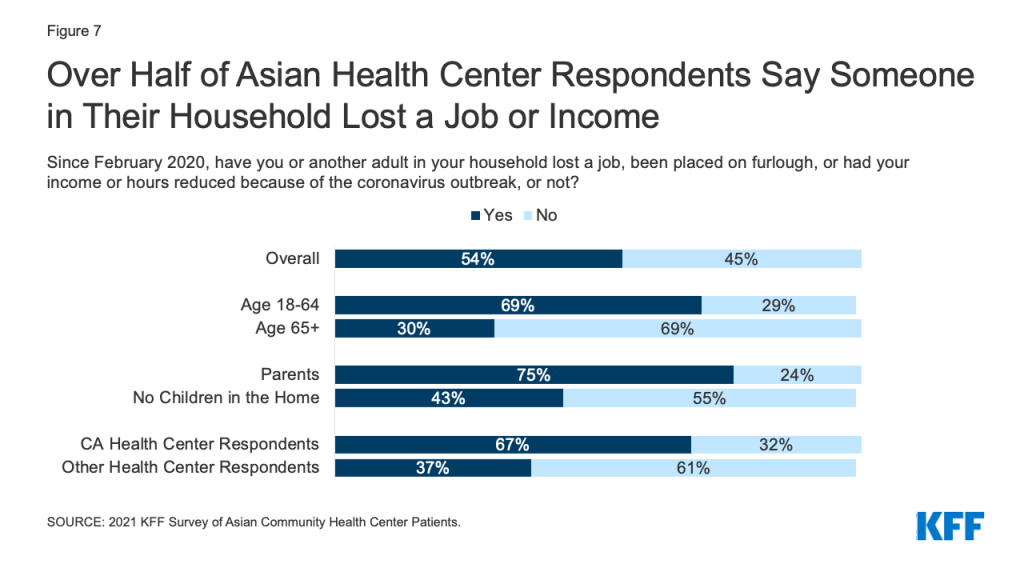

Over half (54%) of Asian health center respondents say they or another adult in their household lost their job or had their income or hours reduced due to the pandemic (Figure 7). This share rises to 75% for those who are parents and nearly seven in ten among those under age 65 (69%) and who are California health center respondents (67%).

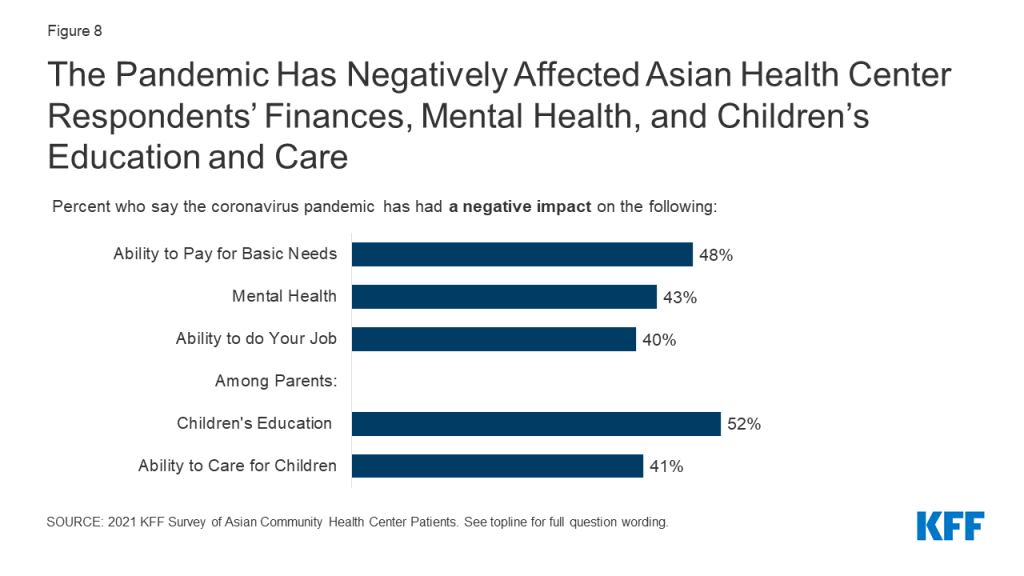

Respondents also report negative impacts on their ability to pay for basic needs, their mental health, and their children’s education and care (Figure 8). Nearly half (48%) say that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected their ability to pay for basic needs like housing, utilities, and food, four in ten (40%) report that it negatively affected their ability to do their job, and 43% say it has negatively impacted their mental health. The share reporting negative impacts on ability to pay for basic needs rises to over half among parents (53%) and men (53%). Vietnamese respondents are more likely than Chinese respondents to report negative impacts on their ability to pay for basic needs (61% vs. 44%) and their ability to do their job (51% vs. 37%), while Chinese respondents are more likely to report positive effects in these areas as well as on their mental health (30% vs. 20%).

Over half of parents (52%) say the pandemic has negatively affected their children’s education and 41% say it has had negative impacts on their ability to care for their children. In contrast, three in ten say the pandemic has positively impacted their children’s education (30%) and their ability to care for their children (30%). California health center respondents are more likely than those of other health centers to report positive impacts on their children’s education (35% vs. 17%) and care (35% vs. 19%), while other health center respondents are more likely than California health center respondents to report no impact on education (26% vs. 11%) or care (39% vs. 20%).

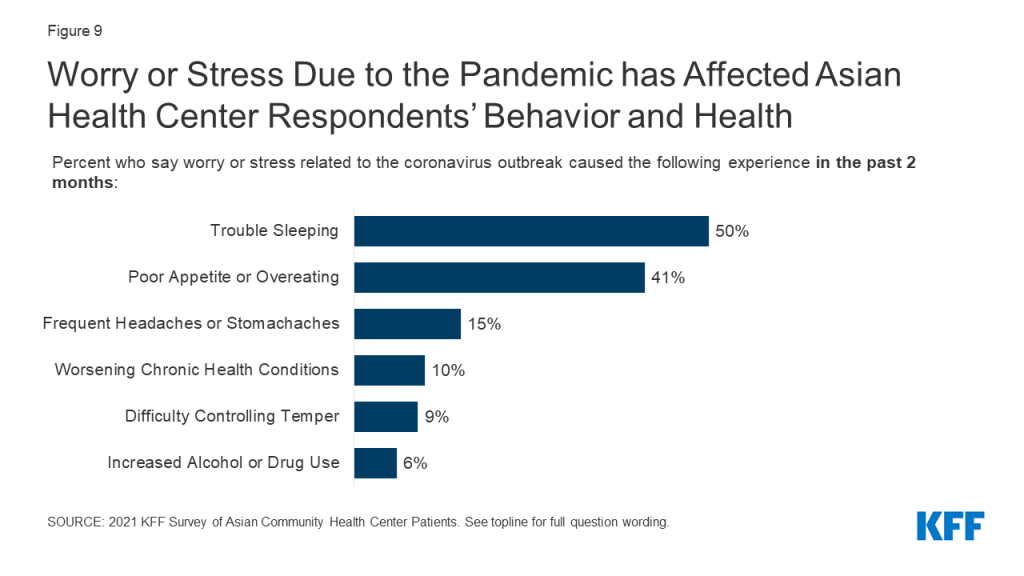

Many respondents say worry and stress related to the pandemic has affected their behavior and health in certain ways. Nearly half (48%) say it has affected their sleep and 39% report changes in their appetite and eating (Figure 9). Others say it has led to frequent headaches or stomachaches (24%), increased difficulty controlling temper (15%), increased alcohol or drug use (10%), and worsened chronic conditions, like diabetes or high blood pressure (9%). Adults under age 65 are more likely than those age 65 and older to report some of these effects, including frequent headaches or stomachaches, difficulty controlling temper, and increased alcohol and drug use. There were also some differences by location, with California health center respondents more likely to report these same effects, which may also reflect that they are more likely to be under age 65.

Three in ten (30%) Asian health center respondents say they put off or went without health care in the past 12 months and 37% of parents report doing so for their children. Among those who put off or went without health care for themselves, 42% say they did not seek health care because of concerns about exposure to coronavirus. Other factors include not being able to take time off work (45%) and not being able to afford the cost (31%), despite being patients of a community health center that provides free or low-cost care. Less than one in ten (6%) say they went without care because they were concerned it would negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status. Adults under age 65 are more likely to say they put off or went without care than those age 65 and older (35% vs. 23%), and a higher share of parents say they went without care than those without children in the home (39% vs. 26%). Parents are more likely than those without children in the home to say they went without care because they couldn’t take time off work or due to difficulty getting to an office or clinic and less likely to cite concerns about exposure to coronavirus as a reason. California health center respondents are more likely than those at other centers to report putting off or going without health care for themselves (42% vs. 15%) and their children (44% vs. 20%). These differences may reflect demographic differences—California health center respondents are more likely to be under age 65 and parents—as well as differences in social distancing policies across locations.

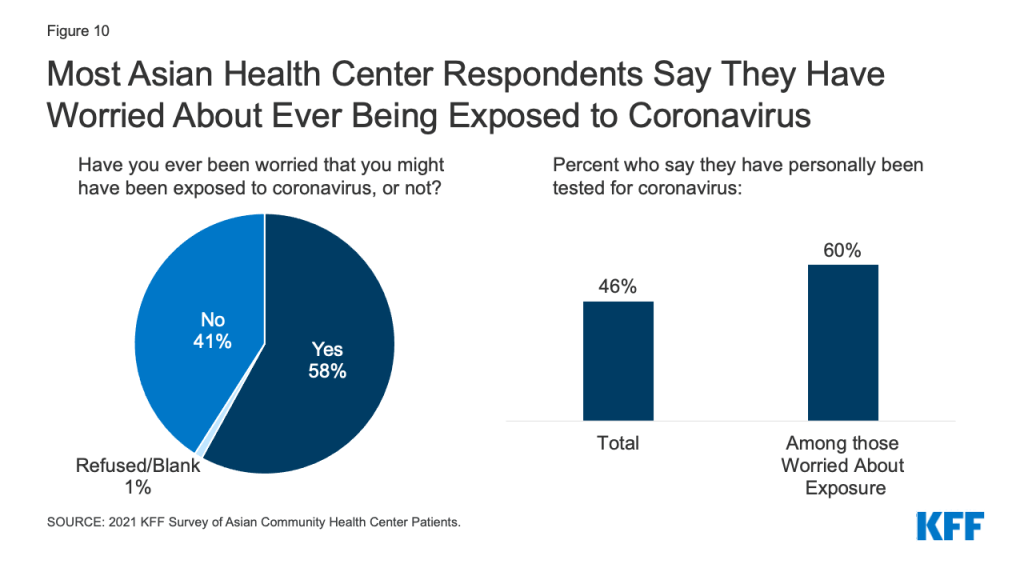

COVID-19 Exposure, Testing, and Vaccines

Nearly six in ten (58%) Asian health center respondents say they have worried at some point about being exposed to coronavirus (Figure 10). Overall, less than half (46%) say they have ever been tested for coronavirus, but the share rises to 60% among those who say they have ever worried about exposure. Among those who worried they might have been exposed but were not tested, the main reasons they give for not getting tested are thinking they could isolate at home (31%) or not knowing where to go to get tested (26%). Some also report concerns about costs (13%) and being told by a health professional they did not need to get tested (13%). About one in ten say they had concerns about effects on their ability to work (12%) or fears of negative effects on their or a family member’s immigration status (10%), even though the federal government has clarified that getting tested will not negatively affect immigration status.

Concerns about ever being exposed to coronavirus are higher among adults under age 65, parents, and California health center respondents (Figure 11). Reflecting these increased worries, these groups are also more likely to report having received a COVID-19 test, overall. There are no notable differences by age or parental status in the share who say they have received a test among those who ever worried about exposure. However, among those who say they have ever worried about exposure, California health center respondents are more likely to report being tested than those of other health centers (66% vs. 49%).

At the time of the survey, nearly two-thirds (64%) of respondents said they wanted to get the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as they can. About a quarter (23%) indicated they want to wait to see how it works for other people. Only 11% said they will only get the vaccine if required or definitely will not get it. Concerns about side effects, believing that the vaccine development process was rushed, and not believing they are at risk for getting seriously ill from the virus are the main reasons why people say they are not ready to be vaccinated. Broader data show that vaccine attitudes have shifted over the course of the vaccine rollout, with willingness to get a vaccine increasing across a number of groups.

Conclusion

While these findings are not representative of Asian immigrants or Asian health center patients overall, they provide new insight into and understanding of the experiences of Asian health center patients who are largely immigrants, a group for whom there remain very little data. The findings illustrate the ways Asian immigrants experience racism and discrimination in their daily lives and indicate that these experiences have increased amid the COVID-19 pandemic. They also suggest that immigration-related fears are ongoing among the community and contributing to reluctance accessing government assistance programs for food, housing, and health care. The findings further show the that the pandemic has taken a toll on mental health and well-being, finances, and access to health care for Asian immigrant families. This increased understanding can help inform COVID-19 response efforts as well as efforts to address health disparities more broadly. Going forward, continued efforts to assess and understand the experiences of smaller population groups, including Asian immigrants, remain important as they are often invisible in public data sources.

Methods

This analysis is based on a KFF survey of Asian patients at four community health centers: Asian Health Services in Alameda County, CA; North East Medical Services, in San Francisco, CA; HOPE Clinic in Houston, TX; and International Community Health Services (ICHS) in King County, WA. In 2019, these four health centers served a total of 154,604 patients, 117,617 of whom identified as non-Hispanic Asian, or 79% of patients with known race/ethnicity. Health centers do not collect information on patient immigration status, but nearly seven in ten patients at these health centers are best served in a language other than English.3 The survey instrument was designed by researchers at KFF in collaboration with staff at the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations and the community health centers who participated in the survey. Community health center staff translated the survey into Chinese (traditional), Vietnamese, Korean, and Burmese. Reflecting their patient demographics, Asian Health Services, North East Medical Services, and ICHS fielded the survey in English, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean, while HOPE Clinic fielded the survey in English, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Burmese.

The survey was conducted between February 15 and April 12, 2021 by health center staff. Over a third (34%) of respondents completed the survey in-person with clinic staff, 32% completed a paper version of the survey, 25% completed the survey online, and 7% completed the survey via phone. There were a total of 1,467 survey respondents. The analysis presented above was limited to 1,086 respondents who self-identified as Asian and indicated that they were a patient of one of the four health centers in their survey responses. Of those included in the analysis, 874 indicated that they were born outside the United States or Puerto Rico and 176 were born in the U.S. or Puerto Rico; 36 respondents did not answer the survey question on nativity.

This work was supported, in part, by the Blue Shield of California Foundation. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities. The authors thank the Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations (AAPCHO) and community health center staff for their assistance developing and fielding the survey.