How State Medicaid Programs are Managing Prescription Drug Costs: Results from a State Medicaid Pharmacy Survey for State Fiscal Years 2019 and 2020

Executive Summary

Medicaid provides health coverage for millions of Americans, including many with substantial health needs who rely on Medicaid drug coverage for both acute problems and for managing ongoing chronic or disabling conditions. Though the pharmacy benefit is a state option, all states provide pharmacy benefit coverage. States administer the benefit in different ways but within federal guidelines regarding, for example, pricing, utilization management, and rebates. Due to federally required rebates, Medicaid pays substantially lower net prices for drugs than Medicare or private insurers. After a sharp spike in 2014 due to specialty drug costs and coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Medicaid drug spending growth has slowed, similar to the overall US pattern; however, state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending as spending is expected to grow in future years. Due to Medicaid’s role in financing coverage for high-need populations, it pays for a disproportionate share of some high-cost specialty drugs. In addition, Medicaid is required to cover the “blockbuster” drugs increasingly entering the market as a result of the structure of the pharmacy benefit. Policymakers’ actions to control drug spending have implications for beneficiaries’ access to needed prescription drugs.

To better understand how the Medicaid pharmacy benefit is administered across the states, KFF and Health Management Associates conducted a survey of all 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) in 2019. Highlights from the full survey are below (ES Figure 1).

What entities play a role in administering Medicaid pharmacy benefits?

States may administer the Medicaid pharmacy benefit on their own or may contract out one or more functions to other parties. The administration of the pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery through managed care organizations (MCOs) and increased reliance on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). In addition, drug utilization review (DUR) boards and pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees play oversight and administrative roles in Medicaid pharmacy benefits.

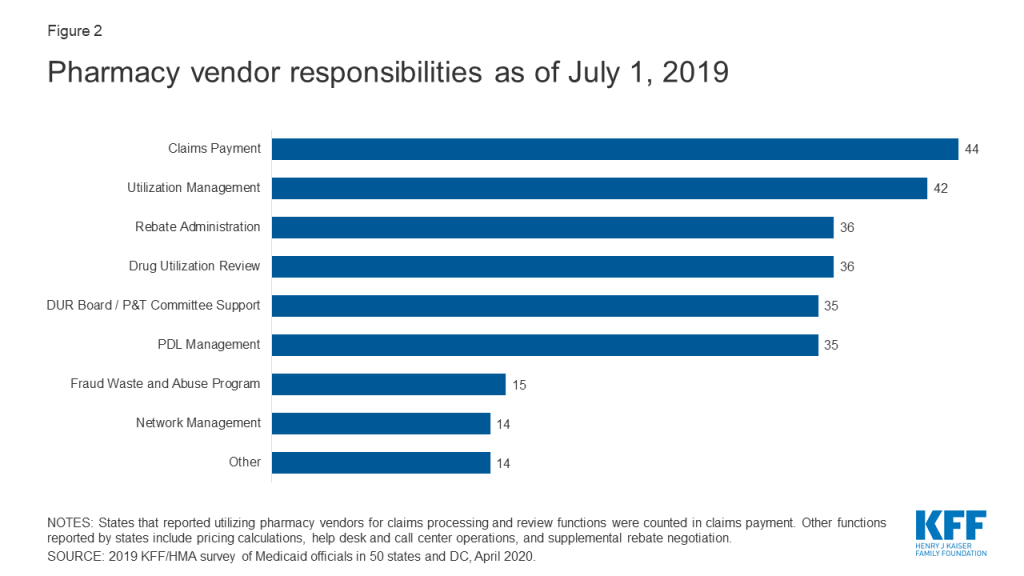

All but one state reported outsourcing some or all functions to one or more vendors as of July 1, 2019. The most commonly outsourced functions reported were claims payment, utilization management, and drug utilization review. Of the 44 states that reported outsourcing the claims payment function, 23 reported that their fiscal intermediary processes pharmacy claims.

States are exploring pharmacy policy reforms to adapt to the growth in managed care and the growing role of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). States reported enacting or considering policy changes such as drug carve-outs, PBM pass-through pricing, and transparency reporting requirements. While most states that contract with MCOs reported that the pharmacy benefit was carved in to managed care coverage, two states reported plans to carve out the pharmacy benefit in FY 2020, one state has announced that a carve-out would be effective in FY 2021, and other states reported carve-outs were under consideration. Fifteen states also reported carving out one or more drugs or drug classes, often as part of a fiscal risk mitigation strategy.

States are taking action to prevent or monitor spread pricing within MCO-PBM contracts. State use of external vendors for administering the pharmacy benefit, particularly the use of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), has generated considerable policy debate about costs and prices in Medicaid, particularly as it relates to oversight and regulation. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy. In the absence of oversight, some PBMs have been able to keep this “spread” as profit. As of July 1, 2019, 11 MCO states prohibited PBM spread pricing and five states reported plans to eliminate spread pricing in FY 2020. One state also reported that a spread pricing prohibition would take effect in January 2021. Twenty-six MCO states also reported they will have transparency reporting requirements in place in FY 2020.

How are states managing use and cost in their programs?

Managing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit and pharmacy expenditures remains a policy priority for state Medicaid programs, and state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth. Because state Medicaid programs are required to cover all drugs from manufacturers that have entered into a federal rebate agreement (in both managed care and FFS settings), states cannot limit the scope of covered drugs to control drug costs. Instead, states use an array of payment strategies and utilization controls to manage pharmacy expenditures.

Most states (46 of 50 reporting states) reported having a preferred drug list (PDL) in place for fee-for-service (FFS) prescriptions as of July 1, 2019. PDLs allow states to drive the use of lower cost drugs and offers incentives for providers to prescribe preferred drugs. In recent years, a growing number of MCO states have adopted uniform PDLs requiring all MCOs to cover the same drugs as the state. Sixteen MCO states reported having a uniform PDL for some or all classes and eight states plans to establish or expand a uniform PDL in FY 2020.

Most states reported that prior authorization (PA) was always (16 states) or sometimes (30 states) imposed on new drugs. Over two-thirds of the responding states (35) report reviewing comparative effectiveness studies when determining coverage criteria, and the vast majority of responding states (45 of 50) require biosimilar drugs to undergo the same review process as other drugs. While states often impose PA on high-cost specialty or non-preferred drugs, a number of states have legislation protecting drug classes or categories from the use of these tools in some or all circumstances.

How are states addressing payment for prescription drugs?

Medicaid payments for prescription drugs are determined by a complex set of policies at both the federal and state levels that draw on price benchmarks to set both ingredient costs and determine rebates under the federal Medicaid drug rebate program (MDRP). States set policies on dispensing fees paid to pharmacies and beneficiary cost-sharing within federal guidelines, while federal regulations guide payment levels for ingredient costs. The final cost to Medicaid is then offset by any rebates received under the federal MDRP. In addition, states or managed care plans may negotiate with manufacturers for supplemental rebates on prescription drugs or form multi-state purchasing pools when negotiating supplemental Medicaid rebates to increase their negotiating power.

Forty-six states report negotiating for supplemental rebates in addition to federal statutory rebates. Approximately two-thirds of these states (30 states) have entered into a multi-state purchasing pool to enhance their negotiating leverage and collections.

A small, but growing number of states are employing alternative payment methods to increase supplemental rebates through value-based arrangements (VBAs) negotiated with individual pharmaceutical manufacturers. States are pursuing these alternative payment methods as a response to high-cost, breakthrough therapies. Two states reported having a VBA in place as of July 1, 2019 and an additional eight states reported plans to submit a VBA State Plan Amendment to CMS or implement a VBA in FY 2020.

States reported a variety of strategies to avoid receiving duplicate discounts on 340B drugs dispensed by safety net providers. The 340B program offers discounted drugs to certain safety net providers that serve vulnerable or underserved populations, including Medicaid beneficiaries. States cannot receive Medicaid rebates for drugs acquired through the 340B program. Strategies to avoid duplicate discounts include relying on the Medicaid exclusion file, prohibiting contract pharmacies and using claims indicators.

States reported continued challenges related to new, expensive breakthrough drugs, particularly those approved on an accelerated pathway. More than two-thirds of the responding states reported that developing policies and strategies related to new high-cost therapies was a top priority. Because of the structure of the MDRP, states are required to cover all drugs approved by the FDA, even if the drug demonstrates limited clinical efficacy.

Looking ahead

States’ management of the pharmacy benefit in FYs 2019 and 2020 reflects efforts to respond to an increasingly changing prescription drug landscape within the flexibility of federal guidelines. Drug pricing has been prominent in national policy debates and lawmakers at both the state and federal levels continue to show interest in efforts to control costs that may have implications for the Medicaid program.

Federal prescription drug policy changes have implications for states. States reported concerns related to enacted legislation such as the SUPPORT and 21st Century Cures Acts as well as monitoring proposed federal statutory and regulatory efforts related to drug pricing, drug reimportation, gene and cell therapies, and PBM contracting reforms. Some federal efforts propose policy changes to Medicaid while others focus on Medicare and commercial insurance but may have implications for Medicaid.

States continue to explore MCO pharmacy policy reforms and view them as a high priority. State priorities include a focus on increasing oversight, implementing uniform PDLs and improving data collection related to managed care.

States remain concerned about prescription drug spending growth and continue to explore policies to ensure fiscal sustainability. States reported developing PA policies for gene and cell therapies, exploring value-based arrangements, and carving out high-cost drugs from managed care.

Report: Introduction

Medicaid provides health coverage for millions of Americans, including many with substantial health needs who rely on Medicaid drug coverage for both acute problems and for managing ongoing chronic or disabling conditions. (Medicaid beneficiaries who also have Medicare receive drug coverage through Medicare). Though optional, all states provide pharmacy benefit coverage and administer the benefit in different ways within federal guidelines regarding, for example, pricing and rebates. To better understand how the Medicaid pharmacy benefit is administered across the states, KFF and Health Management Associates conducted a survey of all 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) in 2019. The survey was designed to capture information on state policies and strategies for managing the pharmacy benefit as well as planned changes for FY 2020 and future priorities and challenges.

Methods

Report findings are drawn from a survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA). The survey was conducted from June through December 2019 via a survey sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2019. The survey instrument is included as an appendix to this report. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report; the counts of state policies or policy actions that are interspersed throughout this report include survey responses from 50 states (including DC). Utah did not respond. This report examines Medicaid pharmacy policies in place or implemented in FY 2019, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2020, and policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2020 (which began for most states on July 1, 2019). Policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems, or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS.

Report: Pharmacy Benefit Administration

What entities are responsible for administering the Medicaid drug benefit?

States may administer the Medicaid pharmacy benefit on their own or may contract out one or more functions to other parties. The administration of the pharmacy benefit has evolved over time to include delivery through managed care (MCOs) and more reliance on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). In addition, drug utilization review (DUR) boards and pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees play an oversight and administrative role in Medicaid pharmacy benefits. State contracts with MCOs, PBMs, or other vendors may have important implications for Medicaid enrollees and providers who are sometimes challenged by the administrative processes they must navigate to access or be reimbursed for medically necessary drugs. MCO subcontracts with PBMs are also under increasing scrutiny as more states recognize a need for more stringent oversight and management of these subcontract arrangements.

Managed Care’s Role in Administering Pharmacy Benefits

Managed care plans play a major role in administering Medicaid pharmacy benefits, with a majority of states using comprehensive managed care arrangements that include prescription drugs as a covered benefit. As of July 1, 2019, 40 states had comprehensive, risk-based contracts with one or more managed care organization (MCOs).1 States with MCOs may opt to “carve in” the pharmacy benefit by including it as a covered benefit and placing the MCO at risk for costs, “carve out” the pharmacy benefit by excluding it from the MCO contract and covering drugs in FFS, or carve in some drugs and carve out others. Changes made to the rebate program by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have encouraged more states to carve in the pharmacy benefit, allowing states to increase budget predictability and leave the MCO accountable for drug costs.2 ,3 States that include pharmacy as an MCO-covered benefit may also build administrative and clinical pharmacy requirements into the MCO contract, as discussed in more detail later in this report.

Carve-out vs. Carve-in of the Pharmacy Benefit

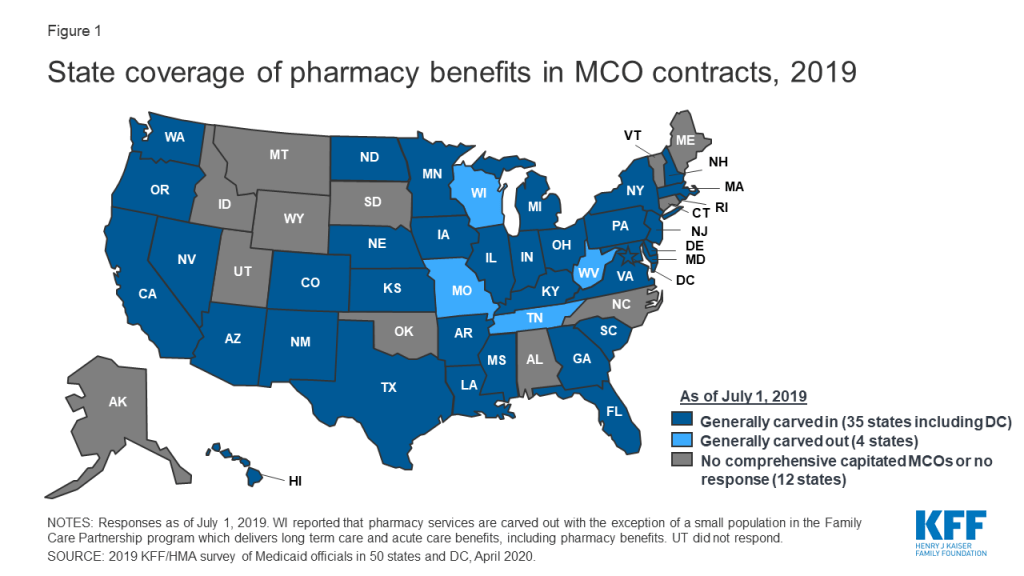

In general, carving the pharmacy benefit into the MCO benefit remains the prevalent approach for managing the prescription drug program for MCO enrollees. Of the 39 MCO states that responded to this survey question, only four states – Missouri, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wisconsin4 – reported that pharmacy benefits were generally carved out (with possible exceptions) as of July 1, 2019, while the remaining 35 states reported that pharmacy benefits were generally carved in (Figure 1).

However, more states are making or considering carve-out changes. Two states reported planned changes for 2020: North Dakota intends to carve out the pharmacy benefit in 2020 and Wisconsin reported plans to carve the pharmacy benefit out of its Family Care Partnership MCO contracts (serving a small number of frail elderly and persons with disabilities) resulting in a full carve-out. Several other states reported that potential FY 2020 changes were “undetermined” or that pharmacy benefit delivery system options were currently under review. Illustrating the dynamic nature of this area, in the period since the survey was originally issued, California issued an RFP for a carve-out of its pharmacy benefit, to be effective January 1, 2021,5 and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services announced its intent to carve out the pharmacy benefit.6

States are more likely to carve out certain subsets of drugs than to carve out the full benefit. We asked states about their use of carve-outs for certain high-cost drug groups/classes: 15 states report carving out one or more of these classes (Table 1 and Appendix Table 1). Of those states, 12 (California, DC, Iowa, Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington) report using the class carve-outs as part of a risk mitigation strategy, as discussed in more detail below.

| Table 1: Drug Classes Carved Out of MCO Benefit, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Drug Class | # of States | States(35 MCO Carve-in States Responding) |

| Hemophilia | 9 | AZ, CA, FL, IN, MI, MS, NH, NJ, WA |

| Hepatitis C | 4 | IN, MI, SC, WA |

| HIV/AIDS | 4 | CA, DC, MD, MI |

| Mental Health | 4 | CA, MD, MI, OR |

| Medication Assisted Therapy | 3 | CA, MD, MI |

| Oncology | 1 | MI* |

| Other | 8 | AZ, IA, IN, MD, NH, OH, TX, WA |

| NOTES: *MI reported it carves out select oncology drugs but not the entire class.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

States are planning additional drug carve-outs for specialty or “blockbuster” drugs. For FY 2020, three states (North Dakota, Nevada, and Washington) reported plans to carve out additional drugs (with North Dakota intending to carve out the full pharmacy benefit), and Maryland reported plans to implement both carve-in and carve-out strategies. The most commonly mentioned drugs carved out or considered for carve-out strategies are Zolgensma and Spinraza, gene therapy treatments for spinal muscular atrophy. Other agents mentioned include CAR-T therapies,7 cystic fibrosis, and muscular dystrophy drugs. Washington indicated it will take a drug-specific approach to new carve-outs, reviewing specifically for impacts to the actuarial soundness of rates or for the likelihood that the financial impact of the new drug will not be spread equally across Medicaid plans. While carving specialty drugs out of the pharmacy benefit is a more common strategy, two states reported an intention to carve drugs back into the managed care benefit in FY 2020: Maryland will carve in HIV/AIDS drugs and Michigan will carve in hemophilia and oncology drugs and select drugs used to treat rare metabolic diseases.

Risk Mitigation Strategies

States that use MCOs to deliver some or all pharmacy benefits to Medicaid enrollees may use risk mitigation strategies to curb plans’ financial risk. As of July 1, 2019, states reported deploying a variety of financial risk mitigation strategies in their MCO contracts, with drug carve-outs and risk corridors being the most common (Table 2). For drug carve-outs, hepatitis C and hemophilia drugs were those most commonly mentioned among states with risk mitigation strategies in place. Six states reported planned changes for FY 2020: Maryland, Nevada, and Washington are carving out additional drugs; Kansas is implementing different reimbursement methods for high-cost drugs; Ohio is removing the hepatitis C risk pool in 20208 ; and Michigan reported a plan to implement high-cost drug kick payments for certain drugs being carved in as of October 1, 2019.

| Table 2: Risk Mitigation Strategies used in MCO Pharmacy Contracts, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Strategy | # of States | States (35 MCO Carve-in States Responding) |

| Drug Carve-outs | 12 | CA, DC, IA, IN, MD, MI, MS, NH, OH, OR, SC, WA |

| Risk Corridors | 10 | AZ, HI, KY, LA, MA, NE, NJ, NV, OR, RI |

| Kick Payments | 4 | CA, KS, MD, MI |

| Risk Pools | 4 | DE, FL, NE, OH |

| Reinsurance | 3 | AZ, NV, VA |

| Other | 2 | MA, PA |

| None | 8 | AR, GA, IL, MN, ND, NM, NY, TX |

| SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

The Role of PBMs and Other Vendors in Administering Pharmacy Benefits

State use of external vendors to administer the pharmacy benefit, particularly the use of PBMs, has generated considerable policy debate about costs and prices in Medicaid. While the relationship between state Medicaid programs and PBMs is not new, the extent to which states rely on PBMs has grown significantly in the past ten years. PBMs may perform a variety of financial and clinical services for Medicaid programs, including adjudicating claims, administering rebates, monitoring utilization, supporting DUR processes, and overseeing and formulating preferred drug lists (PDLs).9 States may utilize PBMs in both managed care and FFS settings. The financial responsibilities PBMs take on, including negotiating prescription drug rebates with manufacturers and dispensing fees with pharmacies, have led to closer scrutiny of these arrangements and changing state policies governing PBM functions.

Fee-for-Service (FFS) Vendors

Within FFS delivery of pharmacy benefits, states have historically outsourced some or all of the administrative functions of the benefit and continue to do so. All responding states except one (California) reported outsourcing some or all FFS functions to one or more PBMs or other vendors as of July 1, 2019.10 The most commonly outsourced functions reported were claims payment and utilization management (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2). Other outsourced functions mentioned by more than one state included provider call centers (Arkansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Vermont) and determining AAC11 or MAC12 pricing (Indiana, Michigan, and Montana).

In recent years, a number of states have consolidated pharmacy administration into more streamlined contracts with a single vendor. These contracts resemble PBM contracts where the vendor has direct management responsibilities over the network, reimbursement rates, and rebate negotiations.13 Of the 44 states that reported outsourcing the claims payment function, 23 reported that their fiscal intermediary, a vendor who handles administrative functions on behalf of the state, processes pharmacy claims14 with the remaining 21 respondents reporting outsourcing to Magellan, Change Healthcare, or OptumRx to process claims.

MCO Vendors and State requirements

States are taking action to prevent or monitor spread pricing within MCO-PBM contracts. Thirty-four MCO carve-in states15 responded to survey questions about spread pricing. When the payment the PBM receives from the MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy differ, some PBMs have opted to keep this “spread” as profit, an issue which has generated a significant amount of political attention to MCO oversight.16 Eleven states prohibited spread pricing as of July 1, 2019; five states (Arkansas, Kentucky, Nebraska, New York and Washington) reported plans to eliminate spread pricing in FY 2020; and Maryland indicated that a spread pricing prohibition would take effect in January 2021 (Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3). Also, Pennsylvania reported plans to require MCOs to develop a process that ensures pharmacy reimbursement is sufficient to cover acquisition costs plus the cost of professional services and the cost to dispense. Twenty-six MCO states reported they will have transparency reporting requirements in place in FY 2020, including 16 states that require MCOs to provide reports to the Medicaid agency.

Outside of contractual prohibitions on spread pricing, very few states reported imposing other restrictions or limitations on the MCO relationship or contract with their PBM. States noted the following alternative actions:

- In Delaware, two legislative task forces are reviewing PBM sub-contracting practices.

- Indiana is considering the level of reporting to be required in 2021. While not contractually required, Indiana indicates that all MCOs have moved to pass-through PBM pricing.

- Kentucky’s MCO contract language includes an annual PDL review, uniform alignment at the discretion of the agency, and mandatory pass-through models; prohibits retroactive clawbacks of payments to pharmacies or imposition of fees, and removes contractual barriers to receiving claim or summary level information from the MCOs.

- Michigan reported plans to impose additional disclosure requirements as of October 1, 2019.

- Nebraska MCOs must obtain state approval of their choice of PBM

- On January 1, 2020, Washington will prohibit retroactive payment adjustments (except by the MCO or in the event of an improper payment).

Drug Utilization Review Board (DUR Board) and Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee Policies

External boards and committees also play a role in overseeing and administering the Medicaid pharmacy benefit. Section 1927 of the Social Security Act requires states to operate a DUR Board to guide drug utilization review (DUR) activities including retrospective review, application of DUR standards, and pharmacy and prescriber interventions. DUR programs also include evaluation for problems like duplicate prescriptions, incorrect dosage, and clinical misuse. Data reported to CMS shows that 48 states have conducted a review of estimated cost savings or cost avoidance of their DUR program, and CMS estimates that DUR programs save about 20%.17 States may also institute a P&T Committee to review therapeutic drug classes for PDL placement and coverage decisions, and 39 of the 50 responding states reported doing so as of July 1, 2019.18 Arizona, which operates its Medicaid program under a Section 1115 waiver, reported having only a P&T committee, but no DUR Board. MCOs may also use their own DUR Board rather than utilize the same board as the FFS agency. Federal data for federal fiscal year 2018 shows that 28 states of 36 states with pharmacy benefits carved in (including Utah which did not participate in this survey) report that at least one of their MCOs has its own DUR Board.19

Conflict-of-interest policies for DUR Boards and P&T committees are left to the states, and 10 states reported not having such a policy in place for at least one of these entities. Federal requirements for P&T committees specify they must consist of pharmacists, physicians and other “appropriate” individuals, but otherwise leave states with flexibility for determining committee operations. Of the 50 responding states, 40 reported having a conflict of interest policy for the DUR Board.20 Of the 39 states that reported having a P&T committee, 36 had in place a conflict of interest policy. Three states had no conflict-of-interest policy for either entity (Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina).21

States vary in what functions DUR Boards and P&T committees play in administering Medicaid pharmacy benefits. DUR Boards and P&T committees may play a role in setting or reviewing utilization management tools. With the exception of review of new drugs for PDL placement which was carried out by a P&T committee in more than half the states, other activities were more evenly divided across the various entities (Table 3 and Appendix Table 4). Most states that reported “other” entities were responsible for one or more of the activities commented that more than one entity was responsible for reviews. However, Connecticut reported that step therapy criteria are developed in legislation, Louisiana reported that its DUR Board reviews prior authorization (PA) criteria developed by the University of Louisiana Monroe’s Office of Outcomes Research and Evaluation, and New Hampshire indicated that an independent medical review contractor was responsible for reviewing orphan/expedited review drugs.

| Table 3: Responsible Entity for Reviewing New PDL Drugs, Step Therapy Criteria, PA Criteria andOrphan/FDA Expedited Review Drugs, July 1, 2019(50 States Reporting) | ||||

| Entity | New PDL Drugs | Step Therapy Criteria | PA Criteria^ | Orphan/Expedited Review Drugs |

| DUR Board | 6 | 14 | 15 | 12 |

| P&T Committee | 29 | 12 | 9 | 10 |

| Medicaid agency | 7 | 14 | 16 | 17 |

| Other | 4 | 5 | 9 | 11 |

| N/A | 4* | 5+ | 0 | 0 |

| NOTES: *States that reported they had no PDL. +States that reported they had no step therapy.^HI did not respond.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||||

Most states reported that DUR Boards and/or P&T committees incorporate comparative effectiveness studies in coverage decisions. Over two-thirds of the responding states (35 states) report reviewing comparative effectiveness studies when determining coverage criteria. The most commonly cited studies come from the Institute for Clinical Economic Review (ICER) and the Drug Effectiveness Review Project (DERP). However, states also report reviewing other drug effectiveness studies and compendia to determine effectiveness and several states use local universities and their DUR Board/P&T support vendor for research.

Report: Cost Containment And Utilization Control Strategies

How are states managing use and costs in their programs?

Managing the Medicaid prescription drug benefit and pharmacy expenditures remains a policy priority for state Medicaid programs, and state policymakers remain concerned about Medicaid prescription drug spending growth. Because state Medicaid programs are required to cover all drugs from manufacturers that have entered into a federal rebate agreement (in both managed care and FFS settings), states cannot limit the scope of covered drugs to control drug costs. Instead, states use an array of payment strategies and utilization controls, discussed below, to manage pharmacy expenditures.

Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs)

Most state Medicaid programs maintain a preferred drug list (PDL), a list of outpatient prescription drugs the state encourages providers to prescribe over others. A state may require prior authorization for a drug not on a preferred drug list or attach a higher copayment, creating incentives for a provider to prescribe a drug on the PDL when possible. In this way, a PDL allows a state to drive utilization to lower-cost drugs, including drugs for which the state has negotiated a supplemental rebate with the manufacturer. With the exception of four states (Hawaii, New Jersey, New Mexico, and South Dakota), all other responding states (46 of 50 states) reported having a PDL in place for FFS prescriptions as of July 1, 2019, and also negotiating supplemental rebates for preferred agents.

Most state P&T committees are responsible for determining PDL placement for new drugs (29 states). A small number of states reported that either the Medicaid agency (7 states) or the DUR board (6 states) is responsible for the review of new drugs for inclusion on the PDL.

Most state DUR Boards and/or P&T Committees review PDLs at least annually. For PDL reviews, 20 of 50 responding states reported annual reviews, and 10 of the 17 states that reported other review periods review their PDLs quarterly, with an additional three states reviewing bi-annually (Appendix Table 5).

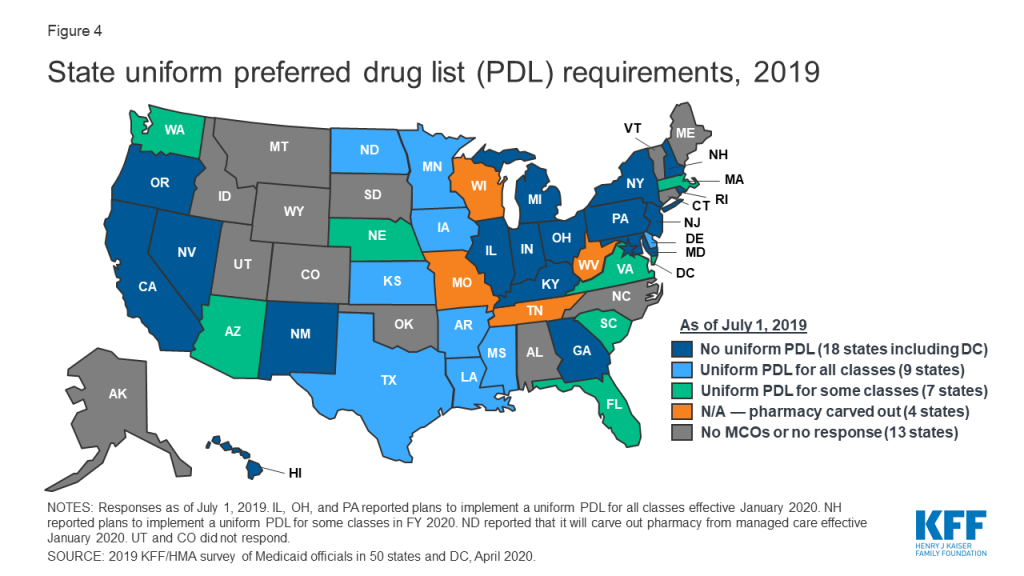

In recent years, a growing number of MCO states have adopted uniform PDLs requiring all MCOs to cover the same drugs as the state. In a previous survey of state Medicaid programs, just nine states reported having a uniform PDL across FFS and managed care in FY 2015.22 In this survey, 16 MCO states reported having a uniform PDL for some or all classes as of July 2019, 18 states reported no uniform PDL requirement (Figure 4). Eight states, however, reported plans to establish (Illinois, Ohio, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania) or expand (Arizona, Massachusetts, Nebraska, and Washington) a uniform PDL in FY 2020. Several states noted that possible future changes were under consideration. Notably, Washington is considering including the physician-administered drugs on the PDL.

Though not all states utilize a uniform PDL, many states do review and approve MCOs’ PDL changes. More than half of the MCO states reported that the DUR Board, P&T Committee, or other state entity reviews and/or approves MCO PDL changes.

Prior Authorization and Step Therapy

States varied in what entity is responsible for developing prior authorization (PA) or step therapy criteria. One of the primary tools that almost all states have long used to manage drug utilization is prior authorization (PA), which requires prescribers to obtain approval from the state Medicaid agency (or its contractor) before a particular drug can be dispensed. States may also use step therapy, a type of PA for drugs that requires beneficiaries to begin treatment for a medical condition with a specific drug therapy, usually a lower-cost drug or generic, and progress to other therapies only if medically necessary. Sixteen states reported that the Medicaid agency is the entity responsible for setting PA criteria while 15 states reported that the DUR board sets PA criteria and the remaining states reported that the P&T committee (9 states) or other entities (9 states) fill this role (Table 3). Fourteen states reported the Medicaid agency develops step therapy criteria and 14 states reported that the DUR Board fills this role. The remainder of states reported utilizing either the P&T committee (12 states) or other entities (5 states).

Most states review PA and step therapy criteria on a less frequent basis than PDLs. The majority of states reported that both step therapy (24 states) and PA criteria (32 states) are reviewed “as needed” (Figure 5 and Appendix Table 5). The most common response for other review frequencies for both step therapy and PA criteria was quarterly.

Most states report that new drugs are subject to PA before undergoing initial review by the DUR Board and/or P&T committee. Four states without a PDL (Hawaii, New Jersey, New Mexico, and South Dakota) reported no PA requirement for new drugs while all other responding states reported that PA was always (16 states) or sometimes (30 states) required. For states answering “sometimes,” states identified reasons related to the new drug’s PDL status, cost and class as conditions for PA prior to review (Table 4). As one state noted, not requiring PA for a new drug could have a detrimental impact on supplemental rebates earned on existing PDL-preferred agents.

| Table 4: New Drug PA Reasons*, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Condition for PA | # of States | States(30 States Responding ) |

| Drug is in a current PDL class | 12 | AL, DC, DE, IN, LA, MT, NY, OH, PA, TN, VA, WV, |

| Cost threshold | 6 | DC, DE, MD, ND, NV, WV |

| Temporary PA required until full DUR BOARD and/or P&T Committee review | 5 | AK, FL, KS, OR, RI |

| PA always required except for protected drug classes (oncology, HIV, etc.) | 4 | CA, MI, MO, OR |

| Drug is in a PDL/therapeutic class that requires PA | 4 | DE, NC, TX, WY |

| Other^ | 6 | CO, MD, NE, OK, OR, WI |

| NOTES: *Responses were collected for the 30 states that reported not automatically subjecting all drugs to PA before initial review. States may have reported more than one condition for PA. ^Other reasons include statutorily required PA time limits, the drug not falling within a PDL class, the drug label having restrictive criteria, and other reasons as determined by the Medicaid agency.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

While states often impose PA on high-cost specialty or non-preferred drugs, a number of states have legislation protecting drug classes or categories from the use of these tools in some or all circumstances. Nearly half of the responding states (24) reported one or more state statutory limits in place on the Medicaid agency’s ability to subject a drug or drug class to FFS utilization controls such as PA or step therapy requirements (Table 5). In some cases, states noted that the statutory prohibition applied to PDL placement but did not prevent the Medicaid agency from imposing quantity limits. Of the 24 states with a statutory limit on utilization controls, 17 included pharmacy as a covered benefit under an MCO arrangement. All but five of these states (Maryland, Michigan, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and Virginia), also applied the statutory limits to MCOs.23

| Table 5: State Statutory Limits on Utilization Controls, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Drugs/Drug Classes Protected | # of States | States(50 States Responding) |

| HIV/AIDS antiretrovirals | 14 | AL, CO, CT, FL, LA, MD, MI, ND, NV, OK, RI, TX, VA, VT |

| Mental health drugs | 10 | CO, CT, HI, IN, MI, MO, ND, OH, OR, VA |

| Cancer drugs | 6 | CO, MI, ND, TN, TX, VA |

| Epilepsy drugs | 4 | CO, CT, IL, MI |

| Medication Assisted Treatment | 3 | DC, IL, TX |

| Other* | 6 | KS, MI, NC, NV, RI, VA |

| NOTES: *Other drugs reported include antihemophilic medications, organ transplant drugs, multiple sclerosis drugs, brain disorder drugs, therapeutic classes with only one drug, or drugs with very low utilization.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

States are active in their management of MCO clinical protocols, or medical necessity criteria, with 28 states reporting that they require uniform clinical protocols for some or all drugs with clinical criteria. Only six states reported no uniform clinical criteria (Figure 6). In addition, five states report that they plan to impose uniform protocols on at least one drug in 2020 (Arizona, Louisiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington). No states reported plans to remove any uniform clinical protocols.

Most states that use MCOs to deliver pharmacy benefits require plans’ PA policies to be no more restrictive than or the same as state rules in FFS. Of the 34 responding states24 that included pharmacy as a covered benefit under an MCO arrangement as of July 1, 2019, nearly two-thirds of these states (22) required MCO policies to be no more restrictive than FFS policies (Table 6).

| Table 6: Limits on MCO PA and Step Therapy Criteria, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Drug/Drug Classes Protected | # of States | States(34 MCO States Responding) |

| Required to be no more restrictive | 22 | AR, CO, DC, DE, FL, GA, IL, KY, LA, MA, MS, ND, NE, NH, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, TX, VA, WA |

| Varies | 4 | HI, MN, NJ, SC |

| Required to be the same | 2 | IA, KS |

| Required to be no less restrictive | 2 | NM, NV |

| Permitted to be more restrictive | 2 | CA, MD |

| Other | 2 | IN*, MI+ |

| NOTES: *IN reported that MCO contracts requirements are being transitioned to require “no more restrictive” policies as contracts come up for renewal. +MI reported that MCO policies can only be less restrictive than the PA and step therapy criteria outlined in the MCO common formulary.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

Similar to their oversight of PDL changes, some states report oversight of MCO PA and step therapy criteria regardless of their uniform requirements for these rules, with the majority of those responding indicating that the state oversees either step therapy, PA/utilization management criteria, or both.

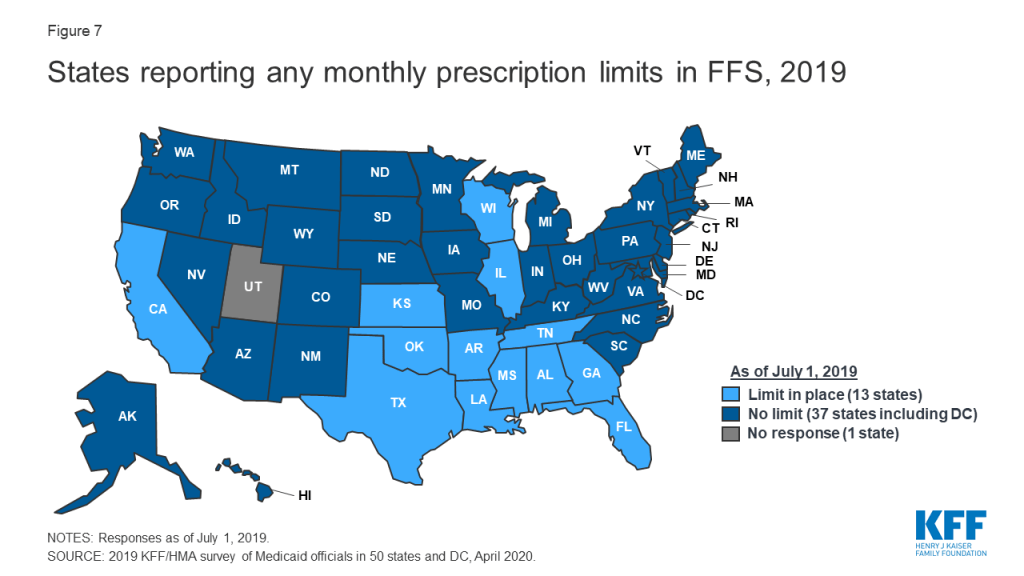

Prescription Limits

Some states report imposing limits on the number of total and/or brand prescriptions a beneficiary may access in a month without PA. States may limit the number of prescriptions a beneficiary may access without prior authorization,25 but prescribers and pharmacists may submit requests to override these limits when medically necessary or under other specific circumstances. About one-quarter of the 50 responding states26 (13 states) reported imposing a monthly limit on FFS prescriptions (Figure 7 and Appendix Table 6). Nine of these 13 states reported that the limit could be overridden using PA or other appeals process.27 Three states reported applying monthly prescription limits only to narcotics and seven of the remaining 10 states with limits noted a number of excluded drugs or drug classes such as HIV antiretrovirals (6 states), cancer drugs (5 states), family planning products (5 states), mental health drugs (4 states), and tobacco cessation products (3 states). Six of the 13 states reported applying the limits only to adults, and four states noted specific exemptions for persons receiving long term services and supports.

Prescription limits were less likely to be uniform across FFS and MCOs as other utilization management tools. States imposing monthly limits were also asked to indicate if MCOs were required to apply the same limits, PA/appeals processes, and exemptions. Four of the 13 states had no MCOs (Alabama and Oklahoma) or did not include pharmacy as an MCO-covered benefit (Tennessee and Wisconsin). Of the remaining nine states, only one (Mississippi) required MCOs to apply the same limits and two states (Florida and Louisiana) noted that MCOs could be less restrictive, but not more restrictive, than the state’s FFS policy. Only one state reported a planned change for FY 2020: Mississippi increased the number of drugs covered in its monthly prescription limit to six from five effective July 1, 2019.

Generic Drug Policies

Almost all states have policies or tools in place to promote generic utilization. As shown in Table 7 and Appendix Table 7, the most common policy reported was a mandatory generics policy (41 states). Only three states (California, New Hampshire, and Nevada) reported having no policies or tools in place. No state reported planned changes to their policies for generic utilization for FY 2020, although one state noted that where applicable, the state will switch from a preferred brand to a preferred generic if the generic becomes less expensive.

| Table 7: Policies/Tools in Place to Promote Generic Utilization, July 1, 2019(50 states responding) | |

| Policy/Tool | # of States |

| Mandatory generics | 41 |

| Lower copayment requirement for generics | 17 |

| Provider education | 13 |

| PDL placement | 5 |

| Higher point of sale dispensing fee for generic substitution | 3 |

| Tiered dispensing fee based on pharmacy’s generic drug utilization rate | 1 |

| Other* | 3 |

| No policies or tools | 3 |

| NOTES: *Other policies and tools reported were a requirement to cover drugs with the lowest net costs, which could be either a brand or a generic (ID and ME), and a lower required copayment for selected generics treating specific conditions (MA).SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | |

In contrast, states are less likely to require biosimilar substitution, though most allow it. No state reported requiring pharmacists to substitute a biosimilar for a prescribed biologic, but over two-thirds of responding states (34 of 48 states)28 indicated that biosimilar substitution was allowed (Figure 8).

The vast majority of responding states (45 of 50) require biosimilar drugs to undergo the same DUR Board/P&T committee review process as other drugs. Five states, however, reported a different process: Arizona’s P&T Committee reviews biosimilars only if the branded product is available within 180 days of when the biosimilar becomes available in the market; Montana will use the same criteria as the original product, unless the DUR Board requests a separate review; New Mexico reported covering biosimilars based on FDA approval and a CMS rebate agreement; Rhode Island indicated that the Medicaid agency reviews biosimilars; and Vermont reported performing a financial analysis in place of a full new drug review.

About half of MCO states align some or all FFS and MCO generic substitution policies. Of the 34 responding states that include pharmacy as an MCO covered benefit, 12 reported that MCOs were required to follow the state’s FFS generic policies,29 while three MCO states (Minnesota, New York, and Washington) reported that MCOs were required to following MCO policies in part.

Report: Payment, Supplemental Rebates And Rebate Management

How are states addressing payment for prescription drugs?

Medicaid payments for prescription drugs are determined by a complex set of policies, at both the federal and state levels, that draw on price benchmarks to set both ingredient costs and determine rebates under the federal Medicaid drug rebate program (MDRP). States set policies within federal guidelines on beneficiary cost-sharing while federal regulations guide the payment methodology for prescription drug ingredient cost reimbursement and professional dispensing fees. The final cost to Medicaid is then offset by any rebates received under the federal MDRP. In addition to federal statutory rebates under MDRP, most states negotiate with manufacturers for supplemental rebates on prescription drugs, frequently using placement on a PDL as leverage. States have also formed multi-state purchasing pools when negotiating supplemental Medicaid rebates to increase their negotiating power. In addition, most MCO states allow their MCOs to negotiate their own supplemental rebate agreements with manufacturers. A few states have also used their supplemental rebate authority to negotiate alternative payment models with manufacturers, and states continue to show interest in these arrangements.

Supplemental Rebates

Most states use competitive procurement to select an entity to negotiate supplemental rebates, and a majority of states with supplemental rebate programs rely on a purchasing pool to negotiate the rebates. Of the 46 states reporting supplemental rebate programs, 24 states reported that a purchasing pool handled negotiations, six states indicated a PBM, five states indicated the state Medicaid agency, seven states indicated another vendor, and four states reported that more than one entity was responsible for negotiations (Appendix Table 8). Three-quarters of the states (35) reported that the negotiating entity was selected through a competitive procurement.

Approximately two-thirds of the states with supplemental rebate programs (30 of 46 states) have entered into multi-state purchasing pools to enhance their negotiating leverage and collections. As shown in Table 8, as of July 1, 2019, 30 states reported participating in three different multi-state purchasing pools. Two states (Louisiana and Maine) also reported participating in an intrastate purchasing pool, where multiple agencies within the state consolidate their purchasing,30 and one other state (Nevada) reported new state legislation, effective January 1, 2020, allowing state agencies and non-profits to “pool” their pharmacy expenditures with Medicaid FFS for rebate purposes.

| Table 8: Multi-State Purchasing Pool Participation, July 1, 2019 | ||

| Pool | # of States | States(50 States Responding) |

| National Medicaid Pooling Initiative (NMPI) | 11 | AK, DC, KY, MI, MN, MT, NC, NH, NY, RI, SC |

| Sovereign States Drug Consortium (SSDC) | 10 | DE, IA, ME, MS, ND, OH, OK, OR, VT, WY |

| Top Dollar Program (TOP$) | 9 | CT, ID, LA, MD, NE, TN, WA, WI, WV |

| None | 20 | AL, AR, AZ, CA, CO, FL, GA, HI, IL, IN, KS*, MA, MO, NJ, NM, NV, PA, SD, TX, VA |

| NOTES: *KS reported that contract with a multi-state pool was in place but not used.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

Most states anticipate supplemental rebates to remain steady or increase as a share of pharmacy expenditures. Of the 46 responding states with supplemental rebate programs, nearly three-quarters (34) expected rebates to remain “about the same” in FY 2020 compared to FY 2019, while 11 states expected higher rebates.31 Only one state (Tennessee) projected lower rebate collections due to patent expirations and orphan drug approvals.

Most states with managed care allow MCOs to negotiate supplemental rebates beyond the state supplemental rebate. Twenty-seven of the 34 responding non-carve-out MCO states32 reported allowing MCOs to negotiate supplemental rebates (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 9). Of these 27 states, eight reported having a uniform PDL for one or more classes and that MCOs were not permitted to negotiate supplemental rebates for uniform classes. One MCO state with a uniform PDL (Kansas) reported that it allowed MCOs to negotiate rebates for all classes of drugs, even for classes that are governed by a universal PDL. Seven MCO states reported that MCOs were not permitted to negotiate rebates for any drugs. About one-third of the MCO states that allow MCOs to negotiate supplemental rebates (9 of 25 reporting) indicated that the MCOs’ PBMs were required to pass through supplemental rebate collections to the MCO and nearly two-thirds (16 of 24 reporting states) required MCOs to report aggregate supplemental rebate collections to the state Medicaid agency.

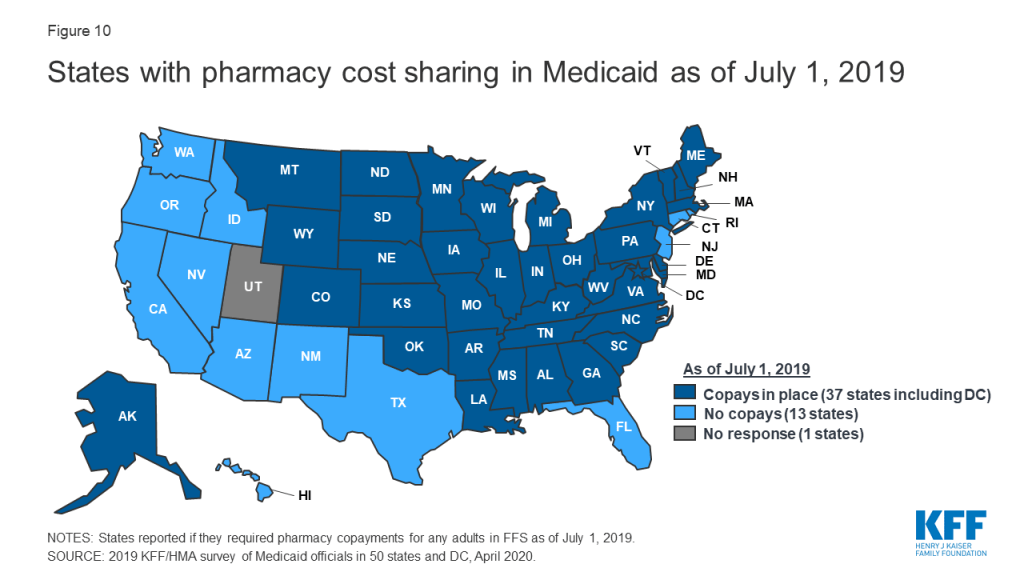

Pharmacy Copays

Most states impose pharmacy cost sharing, and many structure copayment requirements to favor lower-cost generic and preferred brands. As of July 1, 2019, nearly three-quarters of the 50 responding states (37 states) reported requiring FFS pharmacy copayments for non-exempt adults (Figure 10 and Appendix Table 10). All but four of these 37 states (Kentucky, Maine, Missouri, and Ohio) reported that reimbursement to the pharmacy provider was decreased by the copayment amount. Also, 17 states reported lower copays for generics compared to brands, 11 states reported uniform copays for generics and brands, eight states reported that copay amounts varied based on the cost of the drug, and one state reported copays varied based on PDL placement. A few states also mentioned copay exemptions for selected therapeutic classes.

Most of the responding states with copay requirements that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2019 (20 of 24 states) reported that copayment requirements for the expansion population were the same as for non-expansion adults. Only four expansion states reported different requirements: two states reported no copay requirements (Arkansas and Iowa) and two states reported higher copay requirements (Indiana and Michigan). Also, of the 24 responding states that imposed FFS copayments and included pharmacy as a covered benefit under an MCO arrangement as of July 1, 2019, 13 reported no difference in the pharmacy copayment requirement applicable to MCOs, and 11 reported that MCOs either charged no copays or had flexibility to charge or waive copays. A few states reported plans to implement copayment changes in FY 2020: DC and Ohio reported plans to remove copay requirements for selected drugs; Louisiana indicated plans to increase copays to the maximum amount allowed based on household income; North Dakota reported plans to eliminate required copays; and Montana reported plans to eliminate copays for Medicaid expansion adults.

Medication Therapy Management (MTM)

Few states are reimbursing pharmacists for medication therapy management (MTM) services in their FFS programs. MTM, often provided by pharmacists, is intended to ensure the best therapeutic outcomes for patients by addressing issues of polypharmacy, preventable adverse drug events, medication adherence, and medication misuse. MTM typically includes five core elements: medication therapy review, a personal medication record, a medication-related action plan, intervention or referral, and documentation and follow-up.33 Only 9 of 49 responding states34 reported the state paid pharmacists to provide MTM services in the FFS program as of July 1, 2019 (Table 9).

| Table 9: Medication Therapy Management Programs, July 1, 2019 | ||

| State | MTM Conditions/Enrollees | MCOs Required to Cover Same MTM services? |

| Colorado | Drug-drug interactions, drug duplication, adverse reactions and to improve overall patient outcomes | No |

| Michigan | Persons with one or more chronic conditions | No* |

| Minnesota | Persons with one or more chronic conditions | Yes, in part+ |

| Missouri | Diabetes, Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) | NA – Rx carved out of MCO contract |

| Montana | Persons with one or more chronic conditions | NA – No MCOs |

| North Dakota | Asthma, COPD, Diabetes, compliance, transitions of care, high-risk use medications | No |

| New Mexico | Medication overutilization including narcotic overutilization and use with benzodiazepines and/or antipsychotics, and antipsychotic use by children and those specifically in foster care | Yes |

| Oregon | Clozapine monitoring, birth control prescribing, must include covered services on the prioritized list and be a collaboration | No^ |

| Wisconsin | The member takes four or more prescription medications to prevent two or more chronic conditions, one of which must be hypertension, asthma, chronic kidney disease, CHF, dyslipidemia, COPD, or depression. Also, diabetes would qualify a member for MTM eligibility. | N/A – pharmacy carved out of MCO contract |

| NOTES: *MTM services in MI are carved out and paid in FFS. +MCOs in MN must provide at least the same benefit as FFS. ^Most MCOs in OR have the capability to cover MTM services if they choose.SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | ||

Value-Based Arrangements

A small, but growing number of states are employing alternative payment methods to increase supplemental rebates through “value-based arrangements” (VBAs) negotiated with individual pharmaceutical manufacturers. Two states reported having a VBA in place as of July 1, 2019: Oklahoma reported having four VBAs covering two long-acting injectable antipsychotics, and an epilepsy drug, and an antibiotic used mainly in the emergency room;35 and Washington reported having a modified subscription model VBA (also known as the “Netflix model”) for hepatitis C antiviral drugs.36 ,37 An additional eight states (Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Michigan) reported plans to submit a VBA State Plan Amendment to CMS or implement a VBA in FY 2020, and eight states (Connecticut, DC, Idaho, Kentucky, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia) indicated VBAs were under consideration or being explored.

States cited a range of barriers or challenges to implementing VBAs. The most frequently cited barrier or challenge, cited by 10 states, was the administrative resources needed to develop and negotiate VBAs. Eight states indicated that the CMS approval process was a challenge; eight states commented on the data collection and measurement requirements associated with VBAs; five states noted the time needed for implementation and to measure value; five states cited the lack of willing manufacturers; and four states mentioned the risk to the state or challenge of calculating a return on investment. Other challenges mentioned by two states included: the need to obtain stakeholder agreement; the inability to include 340B-eligible drugs; the overall complexity; and limited feasibility for smaller states with smaller volume/utilization.

Other Payment Initiatives

A small number of states use limited pharmacy networks for specialty drugs. Unlike MCOs that sometimes limit the size of provider networks, including retail pharmacy networks (when permitted by the state), to achieve better pricing or higher quality, Medicaid FFS programs typically enroll “any willing,” qualified, and appropriately credentialed provider. Three states, however, reported selective contracting or limited network arrangements for FFS specialty pharmacy drugs in place as of July 1, 2019: Arizona competitively procured a vendor to provide specialty pharmacy services for anti-hemophilic product and other blood disorder medications; Pennsylvania competitively procured two preferred vendors to provide specialty pharmacy drugs, ancillary items and services and clinical supports; and DC created a mental health specialty pharmacy network in 2010 to allow selected physician-administered injectable antipsychotics to be billed as a pharmacy benefit through the pharmacy point-of-sale system. Pharmacies interested in dispensing these medications directly to physician offices or other healthcare facilities may opt in as a provider for this pharmacy network. No state reported having a limited FFS network for non-specialty drugs.

Some states have mandated dispensing fees for MCOs. As described in Table 10 below, nine states (Arizona, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, Nebraska, and New Mexico) reported having have some form of mandated dispensing fee in place as of July 1, 2019. Two states (Illinois and Ohio), plan to add a mandated fee requirement in 2020: Illinois will require MCOs to pay the Department’s dispensing fee for Critical Access Pharmacies, which are, generally, independent pharmacies located in counties with less than 50,000 residents, and Ohio reported plans to implement a supplemental dispensing fee pilot to support independent pharmacies and small chains, especially those who serve a large number of Medicaid beneficiaries.38

| Table 10: Mandated Dispensing Fees, July 1, 2019 | |

| State | Description of Fee |

| AZ | Must pay FQHCs a $8.75 dispensing fee |

| IA | Must pay same dispensing fee as FFS |

| KS | Must pay $0 for Usual and Customary claims and Medicare Part D copay assistance and $10.50 for all other claims, unless there is third party liability, which may have an impact |

| KY | Must pay $2 more in dispensing fees paid to pharmacies by MCOs 39 |

| LA | Must pay non-chain pharmacies (local) at the same rate as FFS |

| MS | Must pay the same as FFS, $11.29 for brand/generic; $61.14 for specialty drugs on state’s Specialty Drug List |

| ND | Must pay FFS rates as of January 1, 2019 |

| NE | Minimum dispensing fee defined for independent pharmacies of 6 or fewer |

| NM | Must pay $2.00 in addition to contracted dispensing fee |

| SOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020. | |

Some, but not all, states have policies in place to manage medical benefit drugs, or drugs delivered outside of Medicaid’s pharmacy benefit. Some drugs covered by Medicaid are paid through the medical benefit rather than the pharmacy benefit. These drugs are sometimes not in a PDL or managed by PBMs; rather, they are approved through the medical management department. These drugs are often high-cost drugs administered in physician offices, infusion suites, or hospitals. There can be wide variability on how these drugs are authorized, and states continue to seek utilization controls. Over half of responding states reported having policies or tools in place to ensure that drugs are paid at the lowest cost benefit including prior authorization, paying for all drugs through the pharmacy benefit, prohibitions on “white bagging,”40 and delegating policy making to MCOs.

Report: State Strategies To Manage 340b Programs

As a condition of participation in the MDRP, manufacturers also must participate in the federal 340B program. The 340B program offers discounted drugs to certain safety net providers (known as covered entities, or CEs) that serve vulnerable or underserved populations, including Medicaid beneficiaries, in order to “stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible.”41 ,42 Additionally, CEs sometimes elect to contract with non-affiliated retail pharmacies to provide pharmacy services to their patients. These are known as contract pharmacy arrangements.

States are prohibited from invoicing manufacturers for Medicaid rebates when a drug is acquired through the 340B program; this is known as the “duplicate discount” prohibition. While it is the responsibility of the Medicaid agency to ensure that 340B claims are excluded from rebate billings to manufacturers, it is the responsibility of the CE to ensure that claims are properly identified during claims billing, including claims billed by contract pharmacies. The use of contract pharmacies has come under scrutiny for complicating the oversight of duplicate discounts.43 States have struggled to ensure compliance with the duplicate discount prohibition and, with the federal government and the National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP), have developed processes to identify 340B claims both at the claims level and administrative level. On January 8, 2020, CMS issued an informational bulletin outlining best practices for states to consider employing to avoid duplicate discounts.44

340B Management Strategies to Avoid Duplicate Discounts

Most states report multiple strategies to manage 340B claims from covered entities (CEs). Most commonly, states rely on the Medicaid Exclusion File published by the federal government to exclude claims from CEs who have indicated that they are participating in the Medicaid program (Table 11 and Appendix Table 11). Many states also prohibit the use of contract pharmacies in FFS (36 states) or managed care (19 states) to fill prescriptions. States also report use of claims indicators to flag 340B claims when they are submitted to the Medicaid agency for payment (31 states). Fewer states reported carving out 340B entities entirely from managed care (6 states) or FFS (2 states).45 Despite the reported challenges of the 340B program, only five states (California, Michigan, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Rhode Island) reported issues with duplicate discounts on this survey.

| Table 11: 340B Management Strategies | |

| Strategy | # of States |

| Use of the Medicaid Exclusion File (MEF) | 38 |

| Prohibition on contract pharmacies in FFS | 36 |

| Use of NCPDP fields* to identify 340B claims | 31 |

| Prohibition on contract pharmacies in managed care | 18 |

| 340B entities not allowed to carve into managed care | 5 |

| Use of medical claims modifiers to identify 340B claims | 7 |

| 340B entities not allowed to carve into FFS | 2 |

| NOTES: *NCPDP fields allow pharmacies to indicate on a claim that a drug was purchased through the 340B programSOURCE: 2019 KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA) survey of Medicaid officials in 50 states and DC, April 2020, and NCPDP Reference Guide.46 | |

340B Reimbursement Models

Most states do not have specific requirements for 340B dispensing fees or MCO payment levels for 340B claims. Federal rules issued in 2016 require that payments to pharmacies for drug costs be based on the actual cost of acquiring the drug. For drugs acquired under 340B, this acquisition cost cannot exceed the 340B ceiling price.47 Federal rules also require that states pay a fee for the pharmacist’s professional services and costs to dispense the drug to Medicaid beneficiaries. States are allowed flexibility in establishing their professional dispensing fees, with some states choosing to segment pharmacies by prescription volume, number of locations or other factors, including 340B status. Forty-two states (of 49 states) indicated they did not have a dispensing fee for 340B programs that was different from the FFS professional dispensing fee, while seven did (Arizona, Illinois, Maryland, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, and Tennessee). Three states (Arizona, Iowa, and Mississippi) mandate that MCOs reimburse 340B claims at the FFS rate.

Report: Challenges And Priorities In Fy 2020 And Beyond

Impact of Federal Reforms

CMS Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Bulletin

Recent MLR guidance will have implications for states that cover drugs through managed care. CMS issued sub-regulatory guidance in May 2019 on Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) reporting for managed care contracts when the managed care entity uses a third-party vendor in a subcontracted arrangement, including PBM subcontracts.48 States’ responses on whether there would be a fiscal impact with implementing the MLR bulletin varied: states that required PBM transparency reporting and/or contracting as of July 2019 reported no fiscal impact because the actual drug ingredient costs and dispensing fees were factored into capitation rates. States with no PBM reporting requirements or that allowed spread pricing reported that capitation rates were likely overstated and would be adjusted in future rate setting periods.49

The 21st Century Cures Act

A number of states cited the 2016 21st Century Cures Act’s expansion of drugs eligible for the FDA expedited review process as a concern. New drugs eligible for an expedited review include cell and gene therapies that are typically high cost and other medications for rare diseases. There are reduced efficacy study requirements for expedited review, which means that a new drug that may not be more effective than a preexisting therapy may be priced many times more. Some of the states commenting on the Cures Act expressed a desire for more flexibility on covering these drugs — even with the MDRP in place — when clinical trials and independent efficacy studies do not support increased effectiveness or equivalent effectiveness at the higher price.

The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act

Several states reported that implementation of the 2018 SUPPORT Act could affect Medicaid drug spending in their state. In particular, states reported that open access to substance use disorder (SUD) agents without prior authorization and without respect to PDL and supplemental rebate strategies has the potential to increase costs for SUD agents considerably.

The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act of 2019

Several areas of this Act were noted as consequential for states, especially reforms to the MDRP, including increasing the amount of the rebate to exceed 100% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). A number of states welcomed this reform, particularly for drugs that increase prices beyond the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) and those that come with very expensive launch prices. As of February 2020, the legislation has been passed out of committee but has not been voted on by the Senate. There remains significant interest at the federal level to address drug prices and the President has signaled his support for bipartisan legislation.

Other Potential Federal Reform Areas

Other potential federal reform areas that states reported watching include repeal efforts of the entire Accountable Care Act, drug reimportation, CMS guidance on CAR-T therapies, modifications to DUR requirements, and PBM contracting reforms.

State Priorities for the Next Two Years

Over two-thirds of the responding states reported that developing policies and strategies related to new high-cost therapies was a top priority. Significant advancements in gene and cellular therapies like CAR-T50 to treat cancer and rare diseases in recent years come with high price tags but are often curative. With more of these costly therapies in the drug development pipeline, states are struggling to adequately budget for current and future therapies. Twenty-three of the 45 states responding to an open-ended question about gene and cell therapies reported that their medical and pharmacy teams have put risk mitigation policies in place, such as PA, risk corridors, or MCO carve-outs, or that an exploration of policy options was underway. Twelve states also reported pursuing or considering State Plan Amendments to enter into value-based arrangements.51

Nearly one-third of the MCO states that carve-in the pharmacy benefit reported that MCO pharmacy policy reforms were a high priority. This included increasing oversight controls, implementing uniform PDLs, and carving the benefit out of managed care. States also reported that they are focusing on improving data collection, implementing new managed care programs, and improving managing medical benefit drugs.

Several states stated that addressing the opioid epidemic, including implementing the SUPPORT Act, is a priority. As noted above, some states are concerned that the SUPPORT Act restrictions on imposing PA on SUD medications will raise costs in those classes of drugs.

Conclusion

States’ management of the Medicaid pharmacy benefit in FY 2019-2020 reflects ongoing state efforts to adapt and respond to the ever-changing prescription drug landscape within the limits of federal law. In response to the increasing roles played by MCOs and PBMs in managing the Medicaid pharmacy benefit, states are increasingly expanding the scope of their clinical and administrative oversight by imposing greater controls over MCO PDL and PA policies and the pricing and reporting arrangements MCOs negotiate with their PBM subcontractors. Conversely, a few states have recently chosen to carve pharmacy benefits out of their managed care arrangements entirely or are considering doing so. A small but growing number of states are also looking to negotiate value-based arrangements with manufacturers to increase supplemental rebates. Looking ahead, states remain concerned about new, high-cost therapies and are prioritizing further reforms to MCO pharmacy policy. Drug pricing has been prominent in national policy debates and lawmakers at both the state and federal levels continue to show interest in efforts to control costs that may have implications for the Medicaid program.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Appendix

Download the Survey (.pdf)

Appendix Table 1: Drugs/Classes Carved Out of MCO Benefit, July 1, 2019 | |||||||

State | Hemophilia Factor | Hepatitis C Antivirals | HIV/AIDs Antiretrovirals | Mental Health Drugs | Medication Assisted Therapy (MAT) Drugs | Oncology Drugs | Other Drugs/Classes Carved Out |

Alabama | |||||||

Alaska | |||||||

Arizona | X | Exondys 51, Spinraza, medications to treat Gaucher Disease | |||||

Arkansas | |||||||

California | X | X | X | X | |||

Colorado | |||||||

Connecticut | |||||||

Delaware | |||||||

DC | X | ||||||

Florida | X | ||||||

Georgia | |||||||

Hawaii | |||||||

Idaho | |||||||

Illinois | |||||||

Indiana | X | X | Exondys 51, Spinraza, Kalydeco, Orkambi, Symdeko, CAR-T therapies, Luxturna, Zolgensma | ||||

Iowa | Zolgensma | ||||||

Kansas | |||||||

Kentucky | |||||||

Louisiana | |||||||

Maine | |||||||

Maryland | X | X | X | Spinraza, Cinryze, and Zolgensma* | |||

Massachusetts | |||||||

Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

Minnesota | |||||||

Mississippi | X | ||||||

Missouri | |||||||

Montana | |||||||

Nebraska | |||||||

Nevada | |||||||

New Hampshire | X | Carbaglu, Ravicti | |||||

New Jersey | X | ||||||

New Mexico | |||||||

New York | |||||||

North Carolina | |||||||

North Dakota | |||||||

Ohio | Zolgensma | ||||||

Oklahoma | |||||||

Oregon | X | ||||||

Pennsylvania | |||||||

Rhode Island | |||||||

South Carolina | X | ||||||

South Dakota | |||||||

Tennessee | |||||||

Texas | Medicaid wrap-around services for outpatient drugs and biological products for STAR+PLUS members | ||||||

Utah | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Vermont | |||||||

Virginia | |||||||

Washington | X | X | Zolgensma, Yescarta, Crysvita, Brineura, Radicava, Revcovi, Gamifant, Exondys 51, Lutathera, Spinraza, Palynziq, Kymriah, Luxturna | ||||

West Virginia | |||||||

Wisconsin | |||||||

Wyoming | |||||||

Totals | 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

NOTES: States that cover pharmacy through managed care were asked to report drug classes that were carved out as of July 1, 2019. “NR” = Not Reporting; “DF” = dispensing fee. *MD reported planned implementation of carve-out in January 2020.SOURCE: KFF / Health Management Associates 2019 Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, April 2020. | |||||||

| Appendix Table 2: Pharmacy Vendor Responsibilities, July 1, 2019 | |||||||||

| State | Utilization Management | Claims Payment | DUR | Rebate Admin | PDL Management | DUR Board/P&T Committee Support | Fraud, Waste, Abuse | Network Management | Other |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Alaska | X | ||||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| California | |||||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| DC | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Georgia | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | ||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | |||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | ||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| North Carolina | X | ||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Oklahoma | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Oregon | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | ||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Utah | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Washington | X | ||||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Wyoming | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Totals | 42 | 44 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 35 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| NOTES: States that reported contracting with a vendor to administer the FFS pharmacy benefit were asked to report which services were provided by a vendor as of July 1, 2019. “NR” = Not Reporting.SOURCE: KFF / Health Management Associates 2019 Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, April 2020. | |||||||||

Appendix Table 3: PBM Transparency Requirements in Place, July 1, 2019 | |||

State | Spread Pricing Arrangements Prohibited as of 7/1/2019? | PBM Transparency/Reporting Requirements in Place FY 2020? | FY 2020 Comments |

Alabama | N/A | N/A | |

Alaska | N/A | N/A | |

Arizona | No | Yes | MCOs will report the amount paid by the PBM to the network pharmacy in FY 2020. |

Arkansas | No | Yes | Legislation effective 7/24/19 to prevent spread pricing. Spread pricing currently reported and attested to each month. |

California | No | No | |

Colorado | NR | NR | NR |

Connecticut | N/A | N/A | |

Delaware | No | Yes | MCO must report actual paid amout to provider on submitted encounter claim. |

DC | No | No | |

Florida | No | Yes | PBM financial records are inspected and audited regarding all financial terms and arrangements with the PBM. Pharmacies have encounter claim submission requirements. MCOs must submit compliance reports. |

Georgia | Yes | Yes | State legislature requires aggregrate reporting of pharmacy expenditures. |

Hawaii | No | No | |

Idaho | N/A | N/A | |

Illinois | No | Yes | New statutory regulatory transparency requirements on PBMs are effective 07/01/2020. No changes to MCO contracts/requirements. |

Indiana | No | Yes | Annually, MCOs are required to provide the Medicaid agency with the aggregate amount paid to pharmacies. |

Iowa | Yes | No | |

Kansas | Yes | Yes | Pass-through pricing on encounters with requirement for a basis of cost determination and a reimbursement policy give specific reimbursement direction to the MCO and PBM, which therefore limits spread pricing. The state fiscal agent also system checks all MCO encounters based on state policy. |

Kentucky | No | Yes | MCOs are required to submit aggregated data via template to the department on a monthly basis. |

Louisiana | Yes | Yes | MCOS are legislatively mandated to submit transparency reports. |

Maine | N/A | N/A | |

Maryland | No | Yes | Effective 2021, MCOS must eliminate spread pricing from contracts. The state is adding the requirement to contracts effective 1/1/2020, allow one year to come into compliance. |

Massachusetts | No | Yes | MCOs have a reporting requirement. |

Michigan | Yes | Yes | PBM spread pricing prohibition reporting will be expanded and inclusion of PBM contract disclosure provisions was added. |

Minnesota | Yes | Yes | A new PBM licensure law was passed during the 2019 legislative session. |

Mississippi | Yes | Yes | MCOs have a monthly reporting requirement to Division of Medicaid. |

Missouri | N/A | N/A | |

Montana | N/A | N/A | |

Nebraska | No | Yes | MCOs must submit monthly PDL load report, pharmacy claims report, and quarterly PDL compliance report. |

Nevada | No | No | |

New Hampshire | No | Yes | MCOs must report encounter data and claims payment data to the Department. |

New Jersey | Yes | No | |

New Mexico | No | Yes | MCOs are required to report quarterly to our State Medicaid Agency. |

New York | No | Yes | MCOs (and their subcontracted PBMs) will be subject to quarterly reporting, which will require the disclosure of all sources and amounts of income, payments and financial benefits paid to the PBM for PBM services rendered on behalf of the MCO. This includes all rebates, clawbacks, credits, manufacturer fees, administrative payments, and other income streams or benefits received by the PBM. |

North Carolina | N/A | N/A | |

North Dakota | Yes | No | |

Ohio | Yes | Yes | MCOs have financial reporting requirements, etc. |

Oklahoma | N/A | N/A | |

Oregon | No | Yes | Additional MCO requirements were written into the 2020 MCO contracts. |

Pennsylvania | No | Yes | The 2019 MCO Agreement requires quarterly transparency reporting as well as ongoing transparent outpatient drug encounters submission. The encounters must include the ingredient cost and dispensing fee paid to the dispensing provider. |

Rhode Island | No | No | |