2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey

Abstract

This annual survey of employers provides a detailed look at trends in employer-sponsored health coverage, including premiums, employee contributions, cost-sharing provisions, offer rates, wellness programs, and employer practices. The 2019 survey included 2,012 interviews with nonfederal public and private firms.

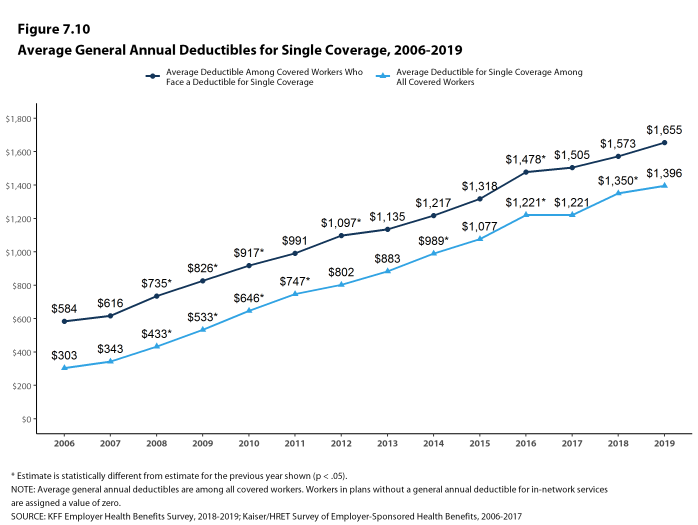

Annual premiums for employer sponsored family health coverage reached $20,576 this year, up 5% from last year, with workers on average paying $6,015 toward the cost of their coverage. The average deductible among covered workers in a plan with a general annual deductible is $1,655 for single coverage. Fifty-six percent of small firms and 99% of large firms offer health benefits to at least some of their workers, for an overall offer rate of 57%.

Survey results are released in several formats, including a full report with downloadable tables on a variety of topics, a summary of findings, and an article published in the journal Health Affairs.

NEWS RELEASE

- A news release announcing the publication of the 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey is available here.

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

- The Summary of Findings provides an overview of the 2019 survey results and is available in the Summary of Findings section.

FULL REPORT

- The complete Employer Health Benefits Survey report includes over 200 exhibits and is available under the Report. The “Report” section contains 14 separate sections. Users can view each section separately or download the section exhibits from the right side of the respective section page.

HEALTH AFFAIRS

- The peer-reviewed journal Health Affairs has published an article with key findings from the 2019 survey: Health Benefits In 2019: Premiums Inch Higher, Employers Respond to Federal Policy.

RELATED

- This related analysis includes an overview of the various network configuration strategies employers are implementing and offers a deeper understanding of the successes, barriers, and trade-offs firms have experienced in their network decision-making.

WEB BRIEFING

- On Wednesday, Sept. 25, 2019, the Kaiser Family Foundation held a reporters-only web briefing to release the 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey.

INTERACTIVE GRAPHIC

- This graphing tool allows users to look at changes in premiums and worker contributions for covered workers at different types of firms over time: Premiums and Worker Contributions Among Workers Covered by Employer-Sponsored Coverage, 1999-2019.

KEY EXHIBITS-CHARTPACK

- Over twenty overview slides from the 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey are available as a slideshow.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

- Standard errors for selected estimates are available in the Technical Supplement here.

- Employer Health Benefits Surveys from 1998–2018 are available here. Please note that historic survey reports have not been revised with methodological changes.

- Researchers may request a public use dataset by going to Contact Us and choosing “TOPIC: Health Costs.”

Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation and NORC at the University of Chicago designed and analyzed the survey.

Summary Of Findings

Employer-sponsored insurance covers over half of the non-elderly population; approximately 153 million nonelderly people in total.1 To provide current information about employer-sponsored health benefits, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) conducts an annual survey of private and non-federal public employers with three or more workers. This is the twenty-first survey and reflects employer-sponsored health benefits in 2019.

HEALTH INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND WORKER CONTRIBUTIONS

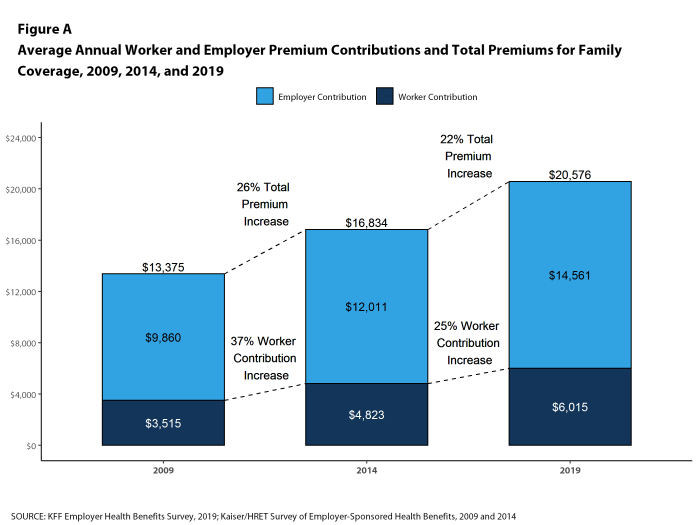

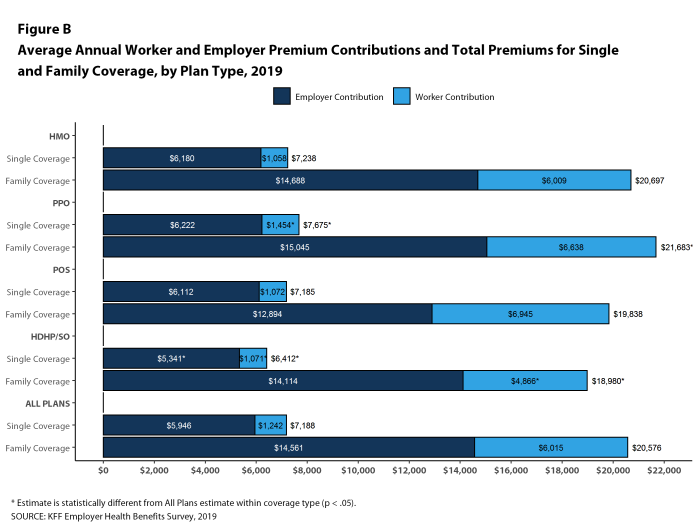

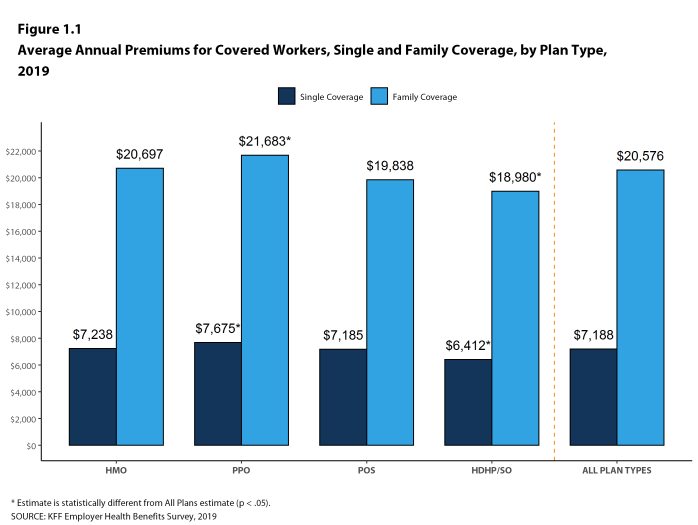

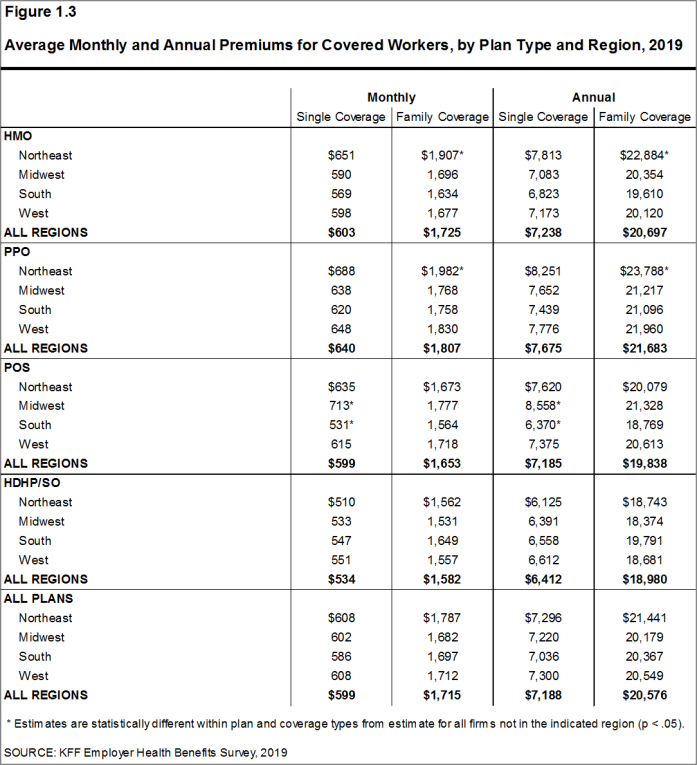

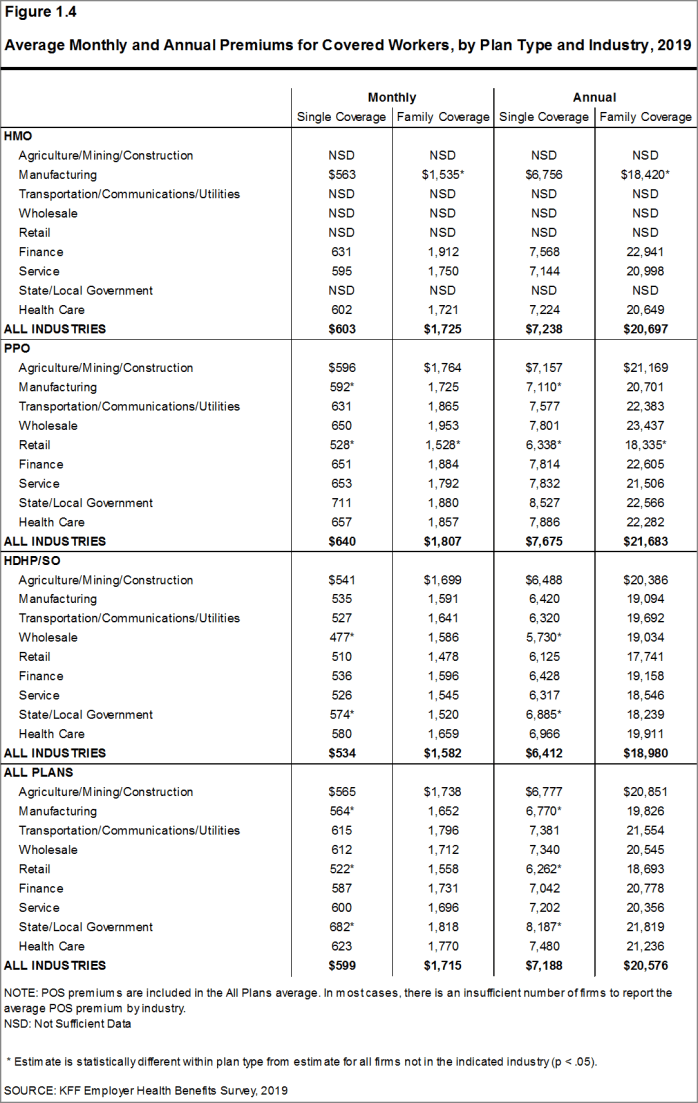

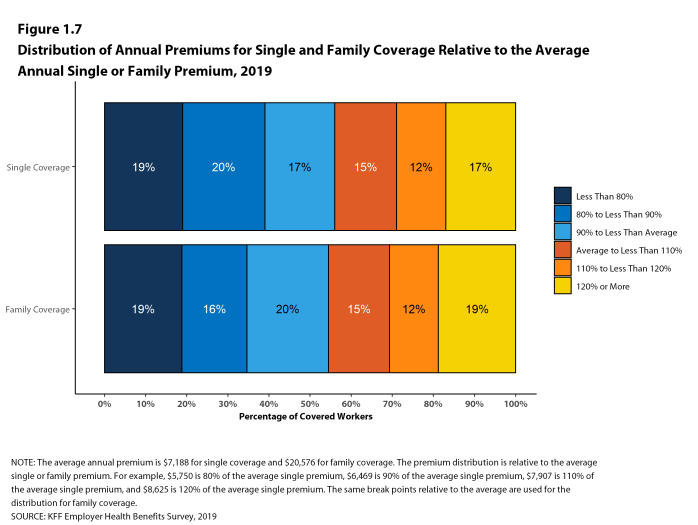

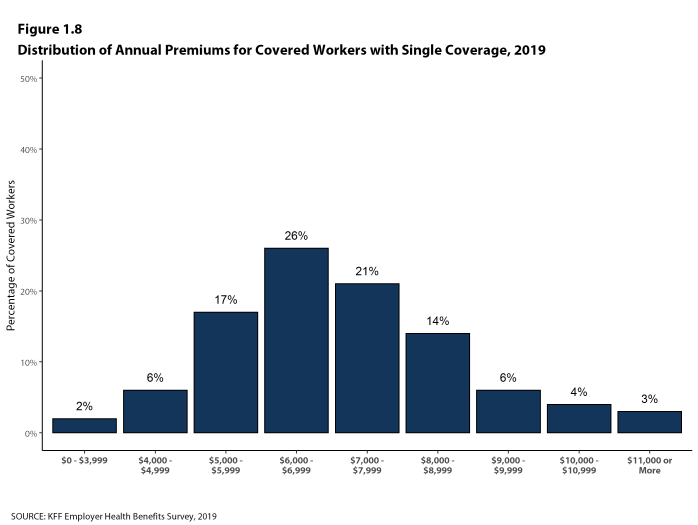

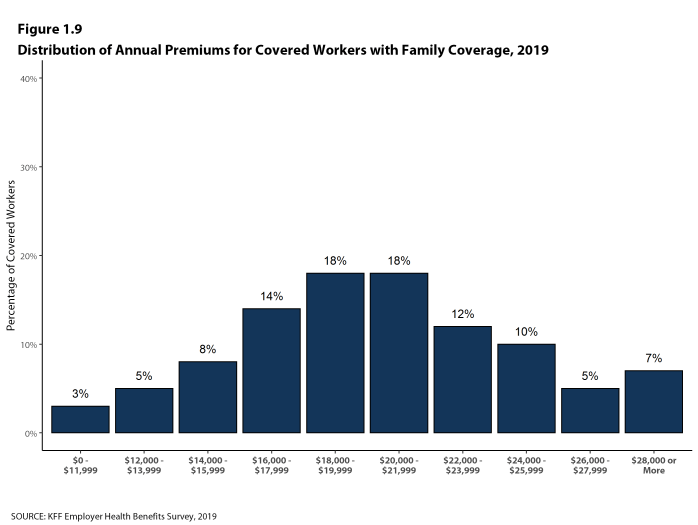

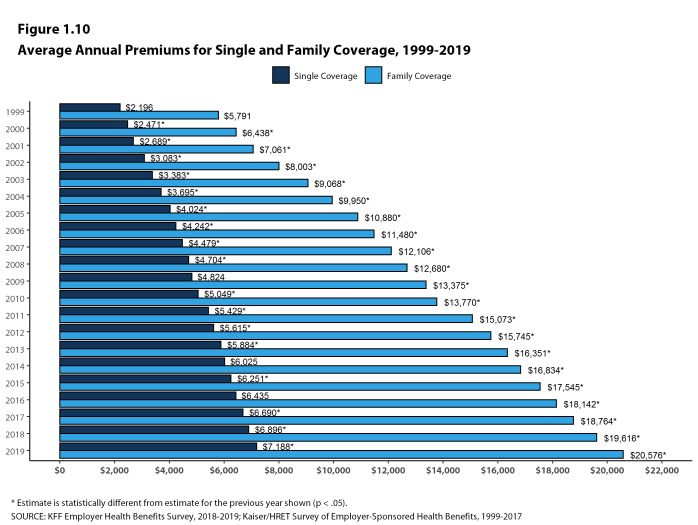

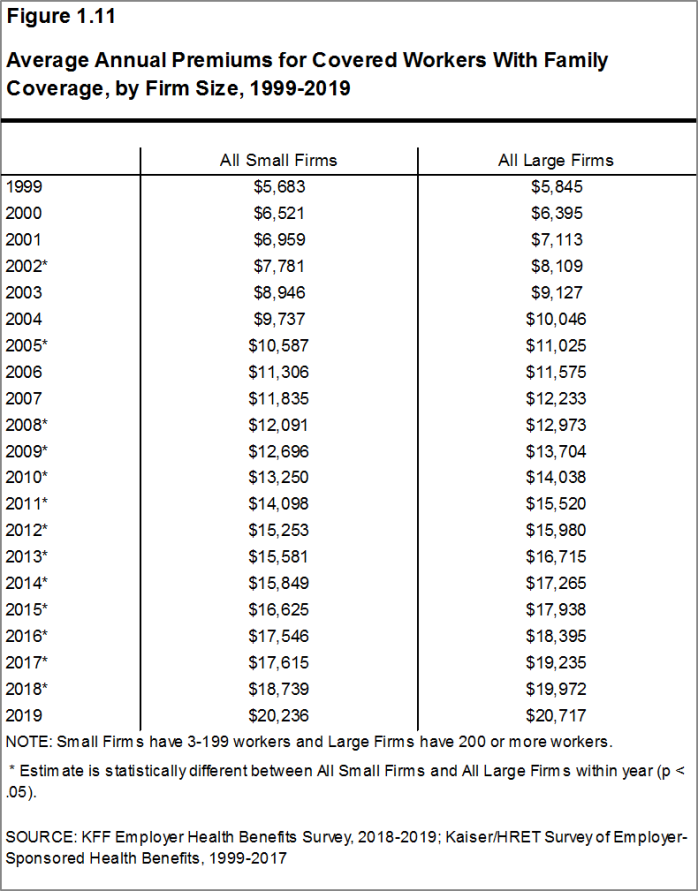

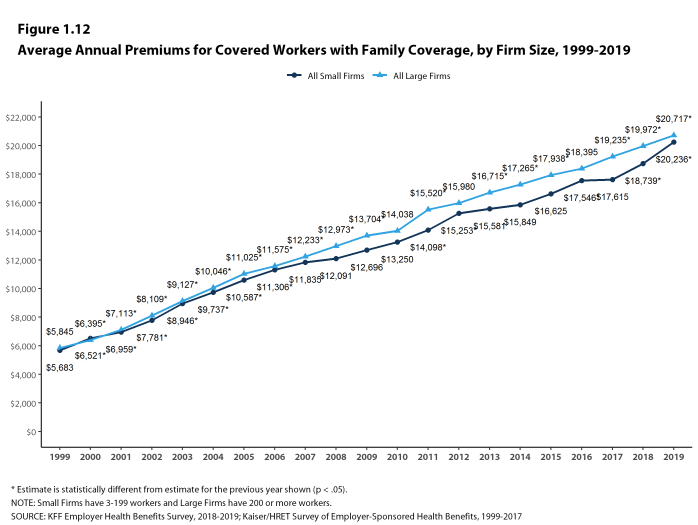

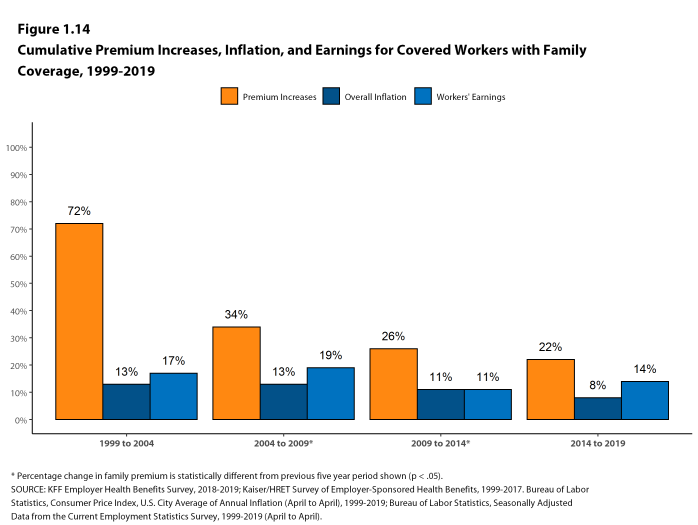

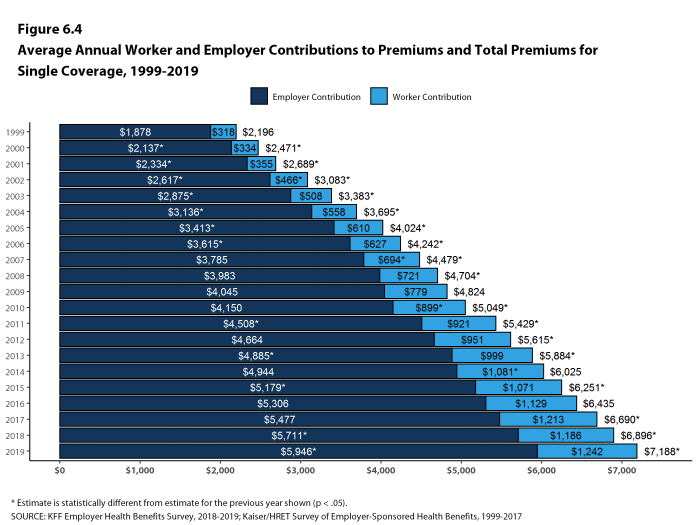

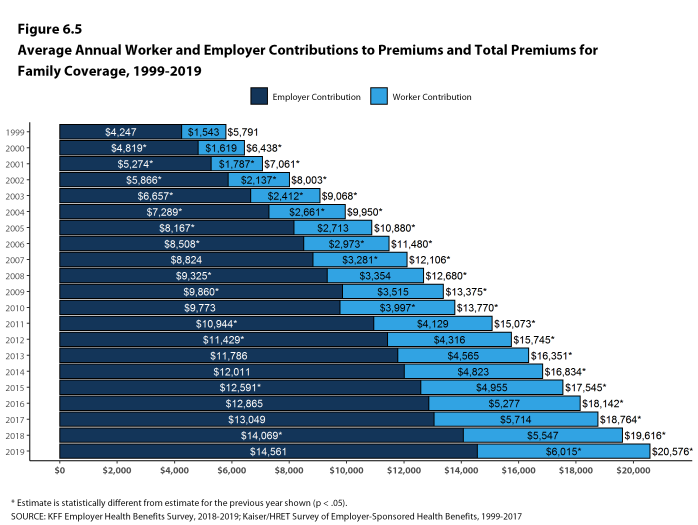

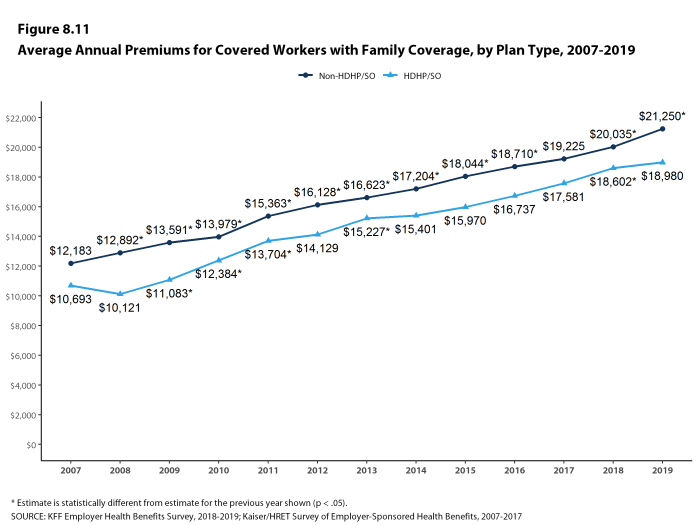

The average annual premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance in 2019 are $7,188 for single coverage and $20,576 for family coverage [Figure B]. The average single premium increased 4% and the average family premium increased 5% over the past year. Workers’ wages increased 3.4% and inflation increased 2%.2

The average premium for family coverage has increased 22% over the last five years and 54% over the last ten years, significantly more than either workers’ wages or inflation [Figure A].

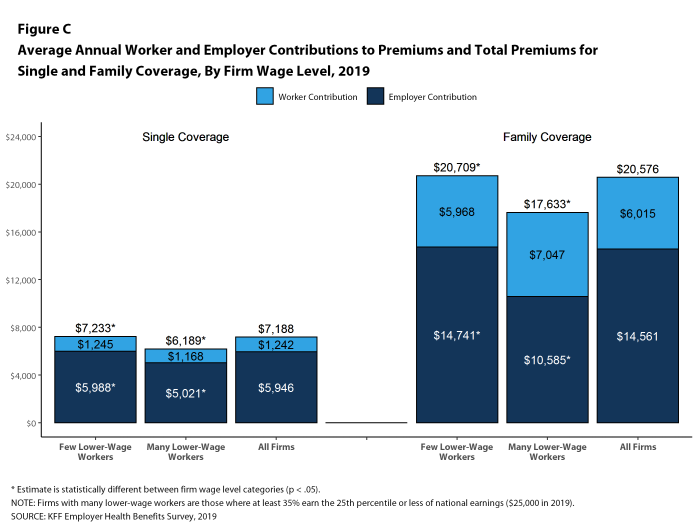

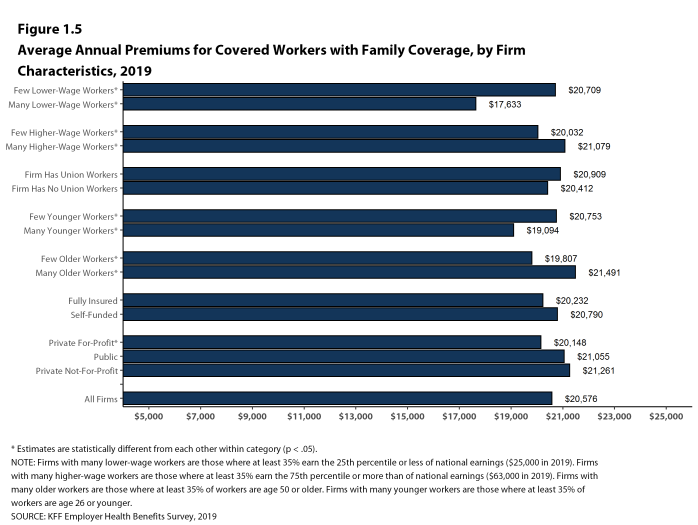

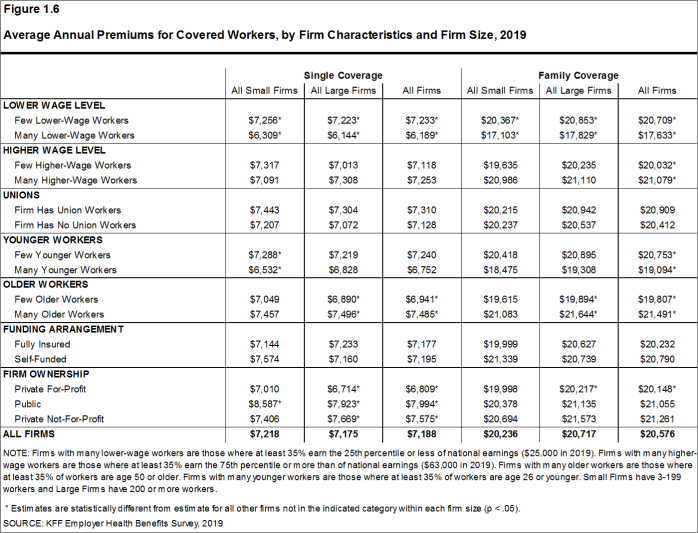

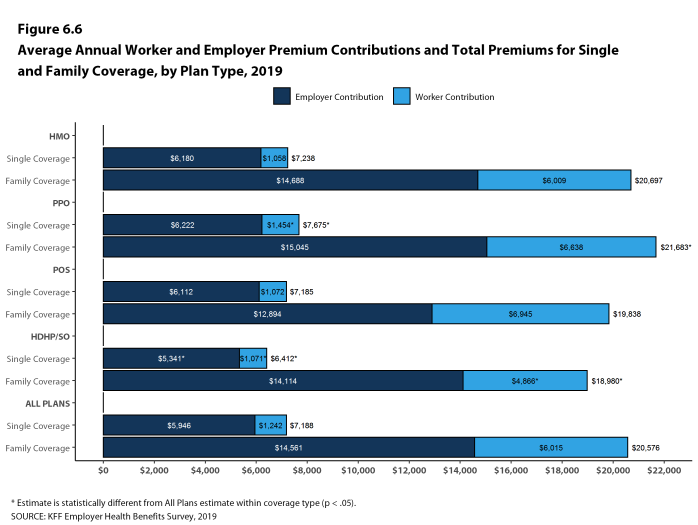

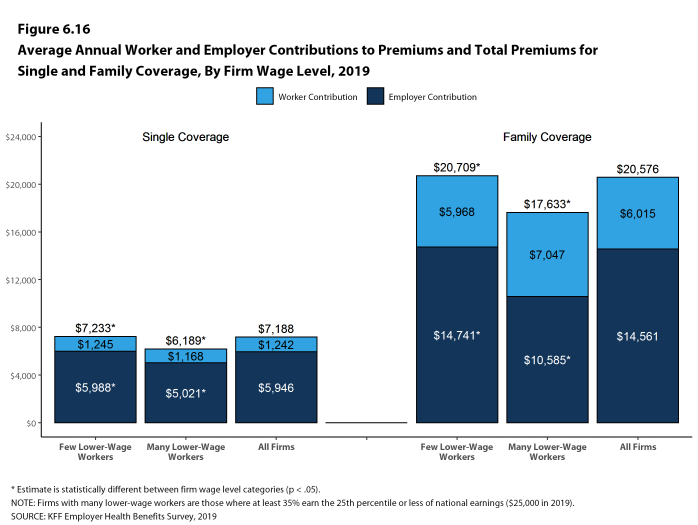

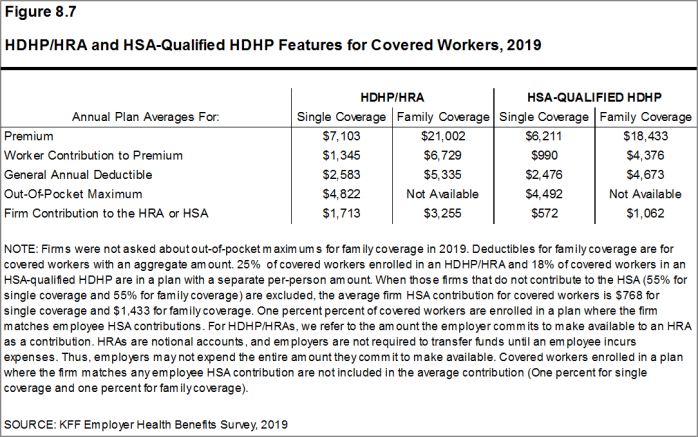

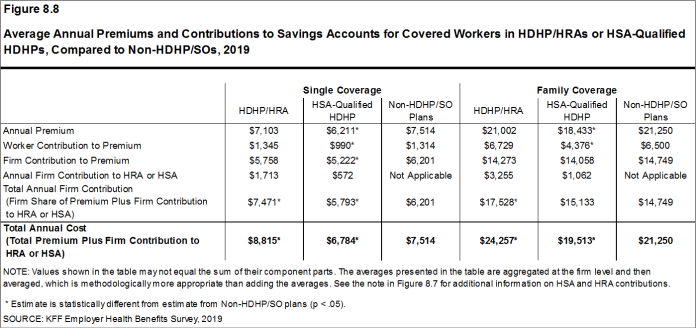

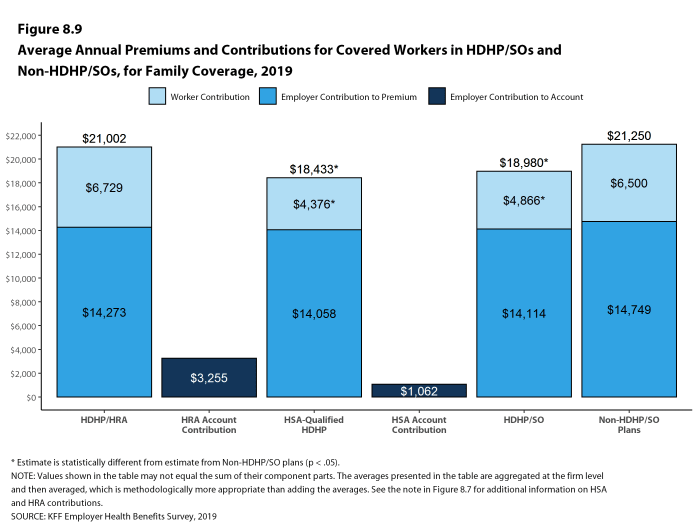

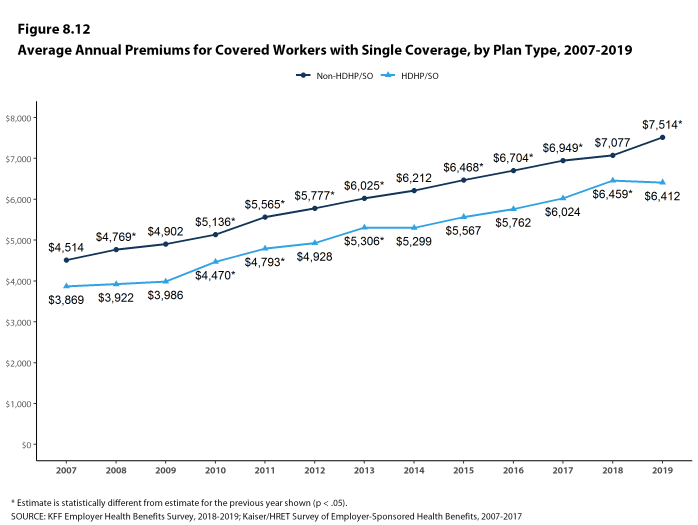

As we generally see, the average premiums for covered workers in high-deductible health plans with a savings option (HDHP/SOs) are considerably lower than the overall average for all plan types for both single and family coverage, at $6,412 and $18,980, respectively [Figure B]. Covered workers in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers (where at least 35% of workers earn $25,000 a year or less) have lower average premiums for both single and family coverage than covered workers in firms with a smaller share, likely because their plans are less comprehensive. Covered workers at private for-profit firms have lower average premiums than covered workers at not-for-profit or publicly owned firms for both single and family coverage.

Figure A: Average Annual Worker and Employer Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Family Coverage, 2009, 2014, and 2019

Figure B: Average Annual Worker and Employer Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2019

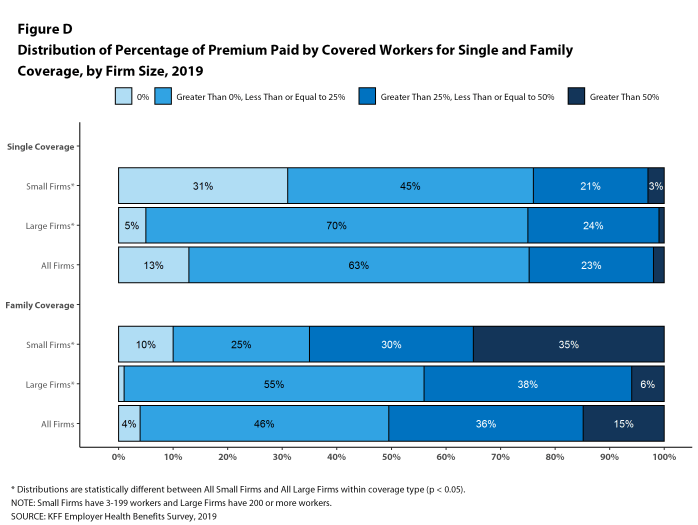

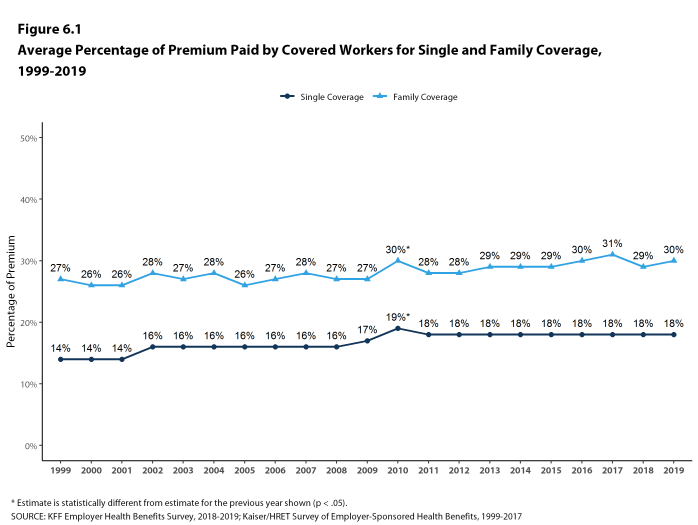

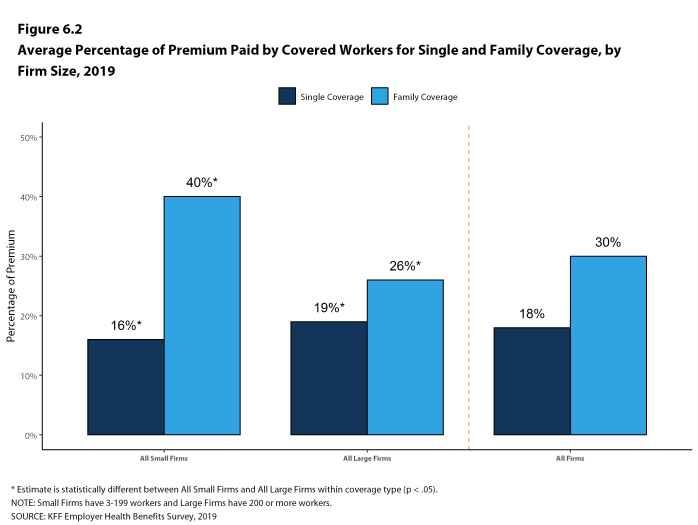

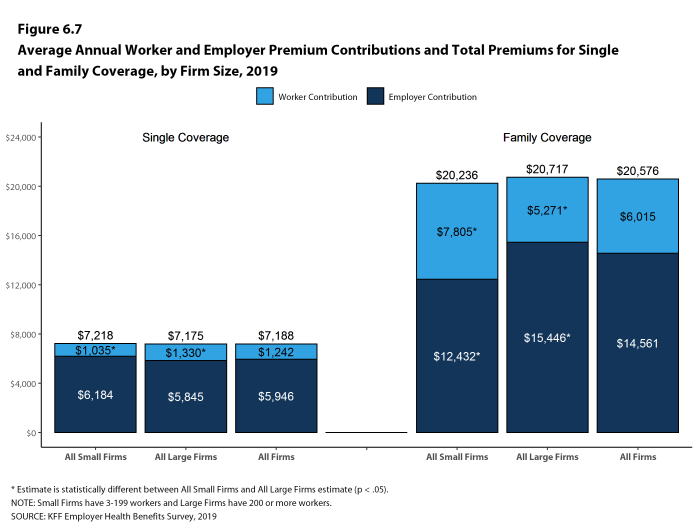

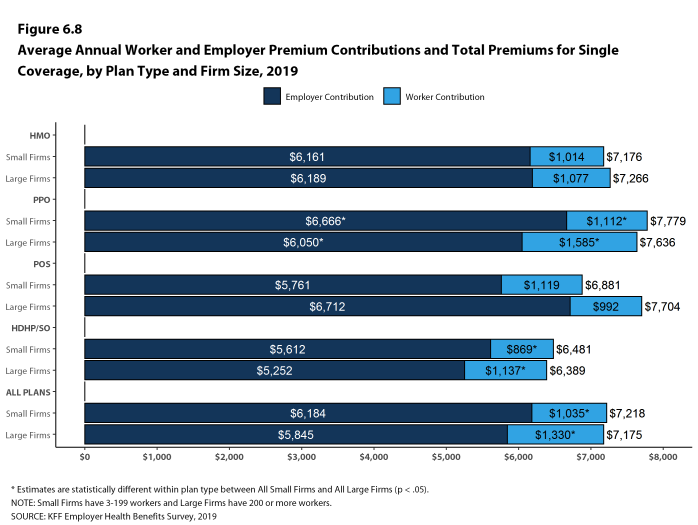

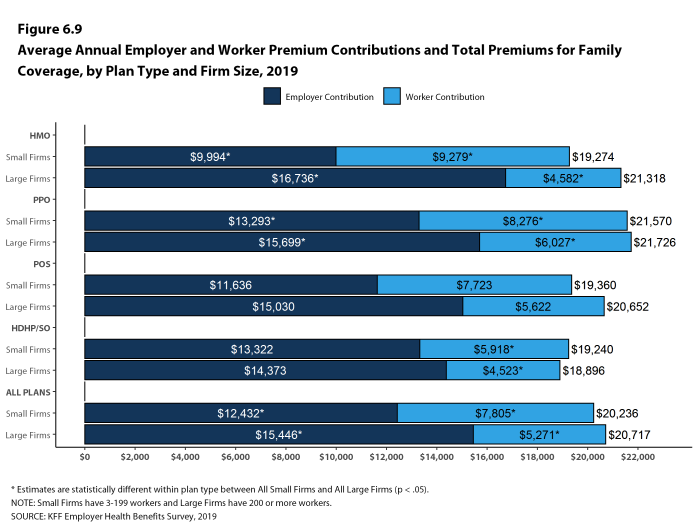

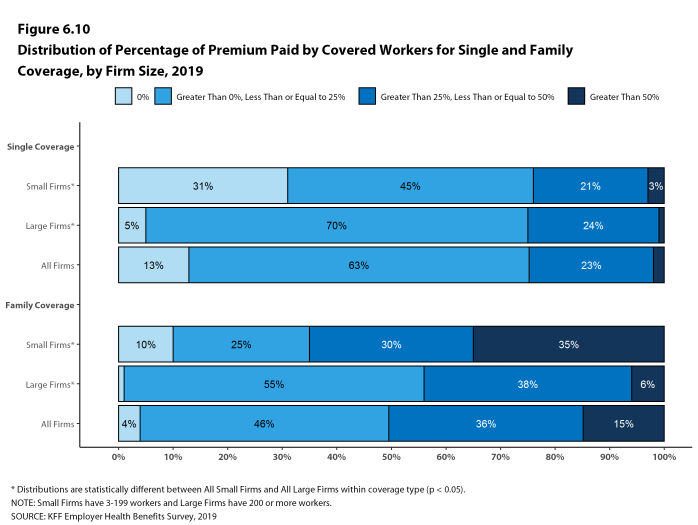

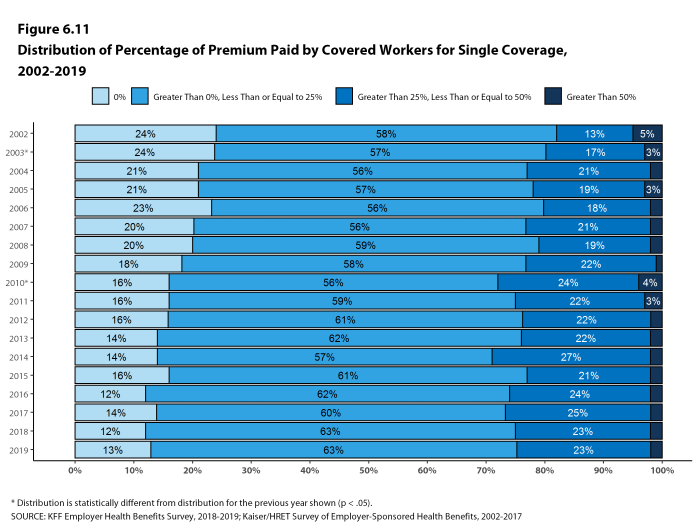

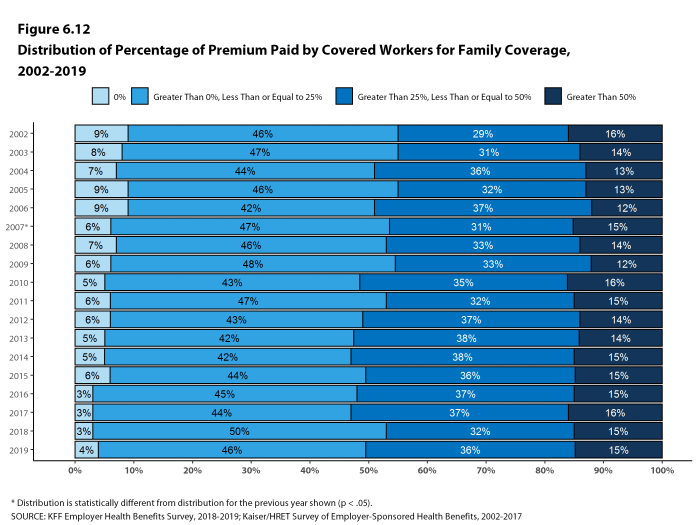

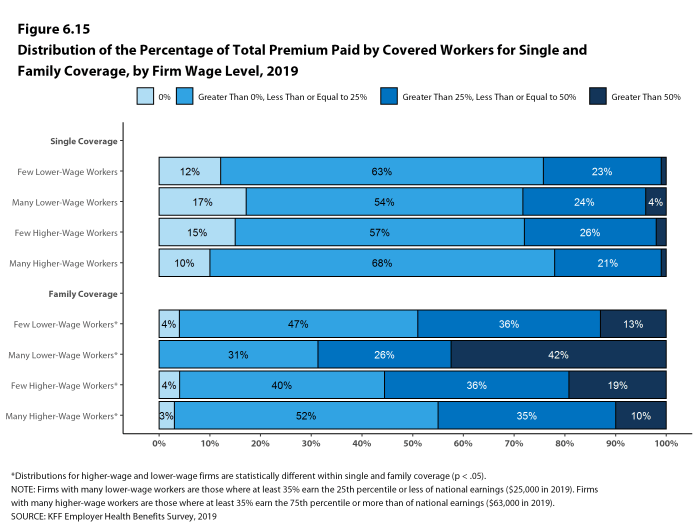

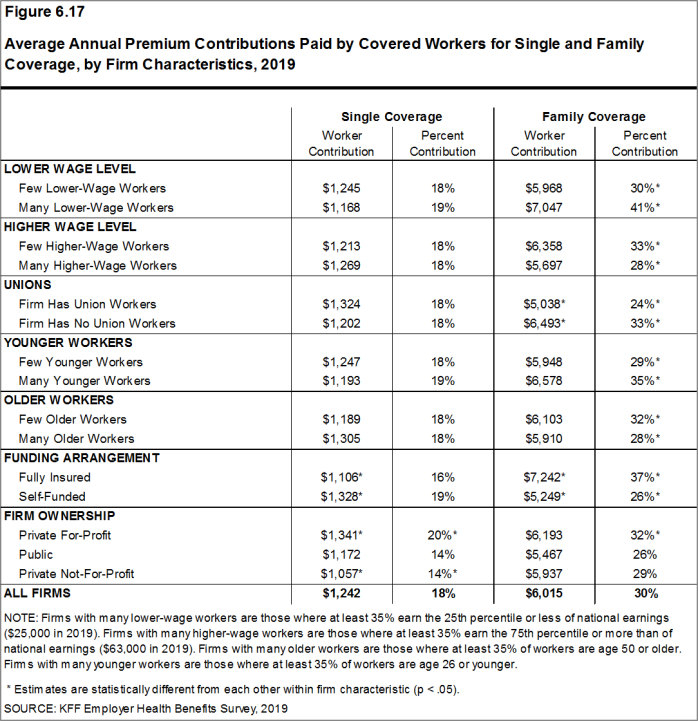

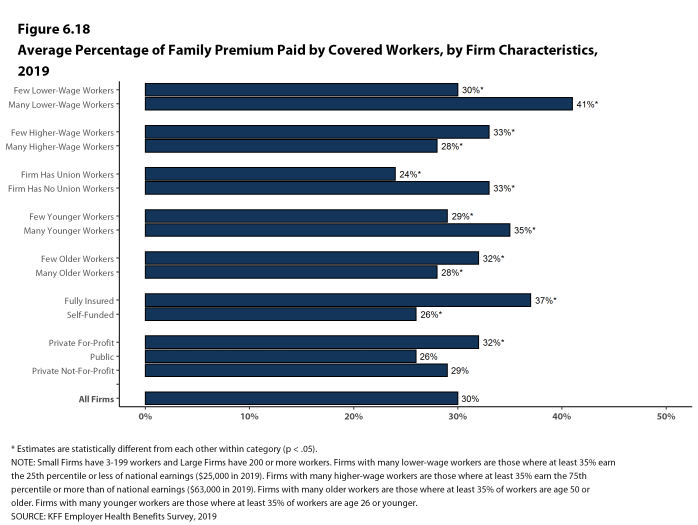

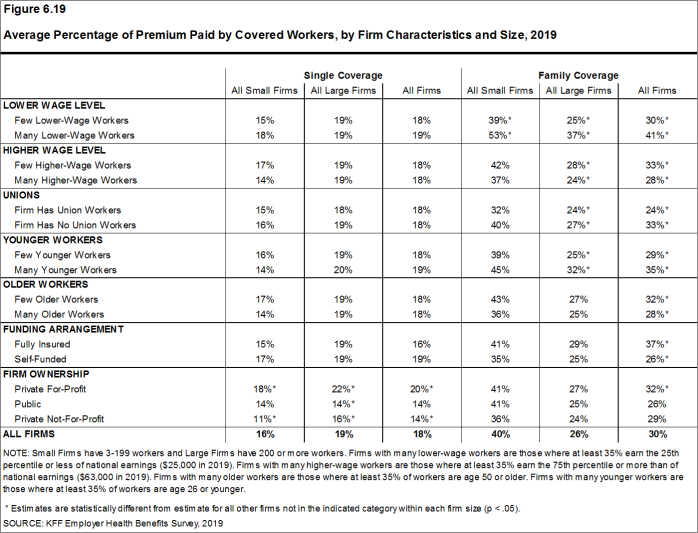

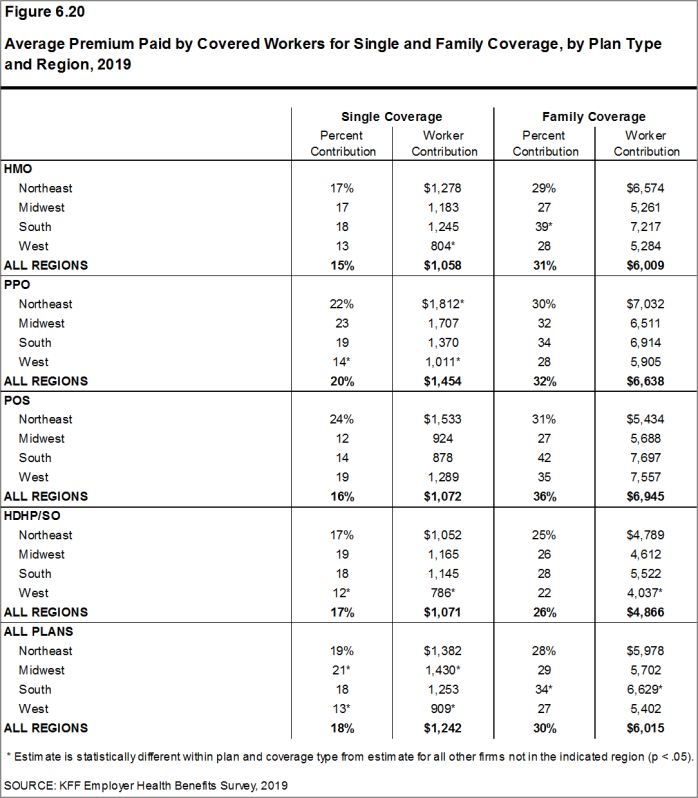

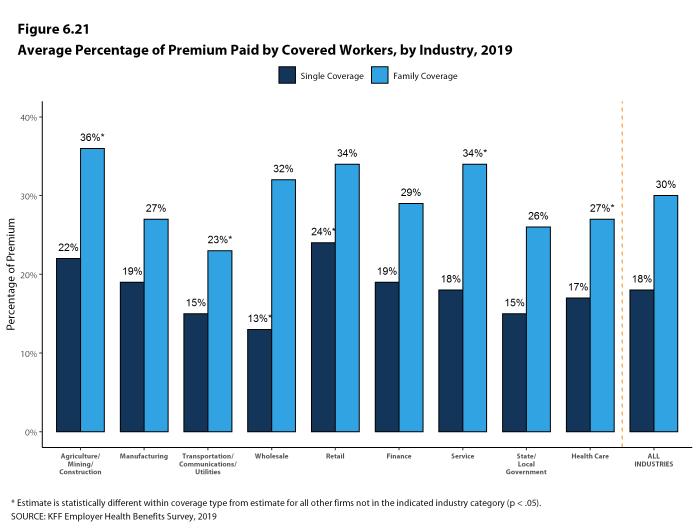

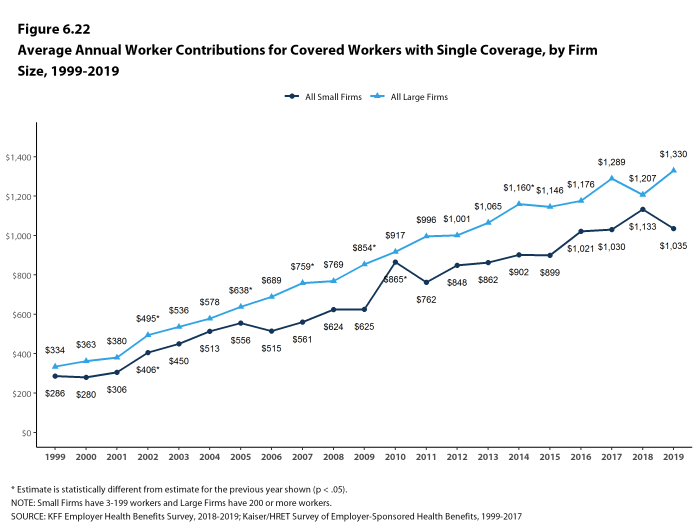

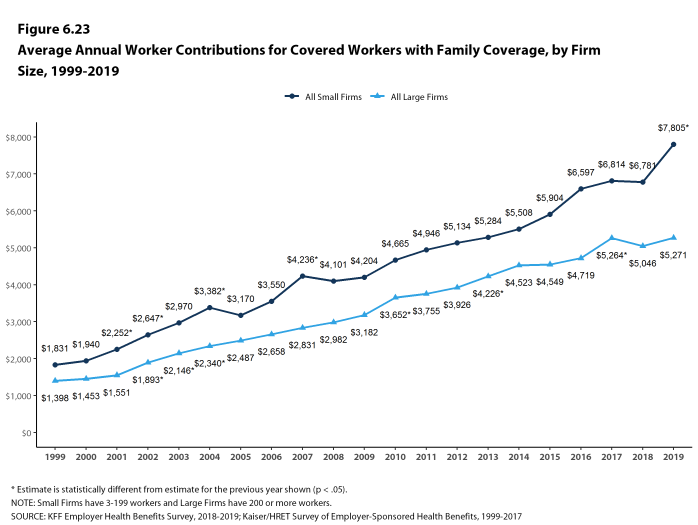

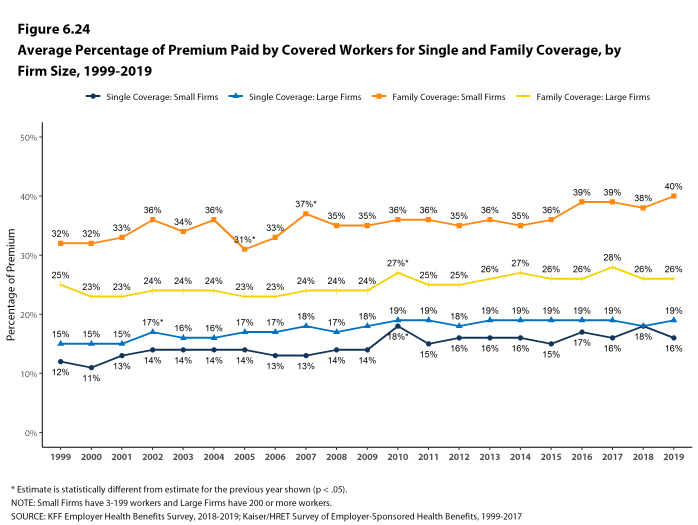

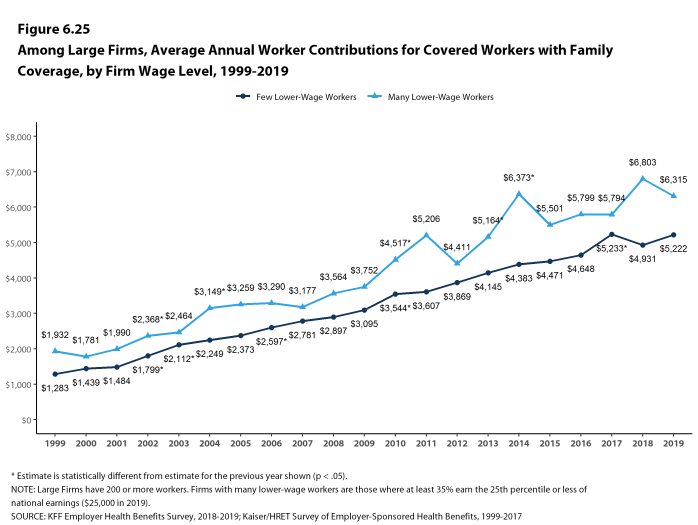

Most covered workers make a contribution toward the cost of the premium for their coverage. On average, covered workers contribute 18% of the premium for single coverage and 30% of the premium for family coverage. Compared to covered workers in large firms, covered workers in small firms on average contribute a lower percentage of the premium for single coverage (16% vs. 19%) and a higher percentage of the premium for family coverage than workers in large firms (40% vs. 26%). Covered workers in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers have higher average contribution rates for family coverage (41% vs. 30%) than those in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers.3 Covered workers at private for-profit firms on average contribute a higher percentage of the premium for both single and family coverage than covered workers at other firms for both single and family coverage.

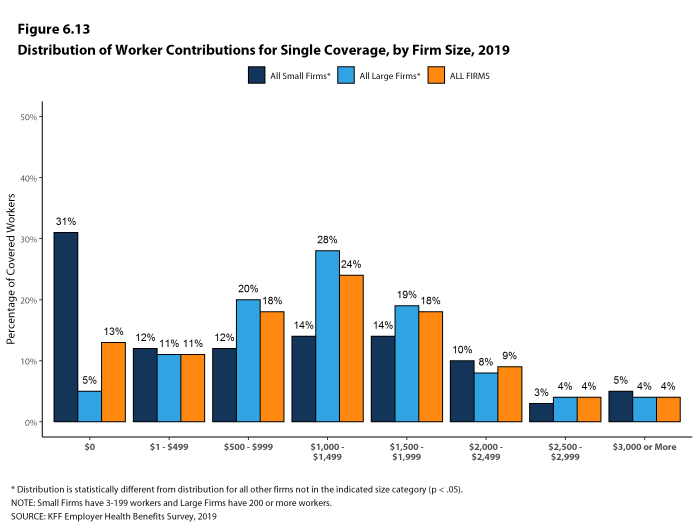

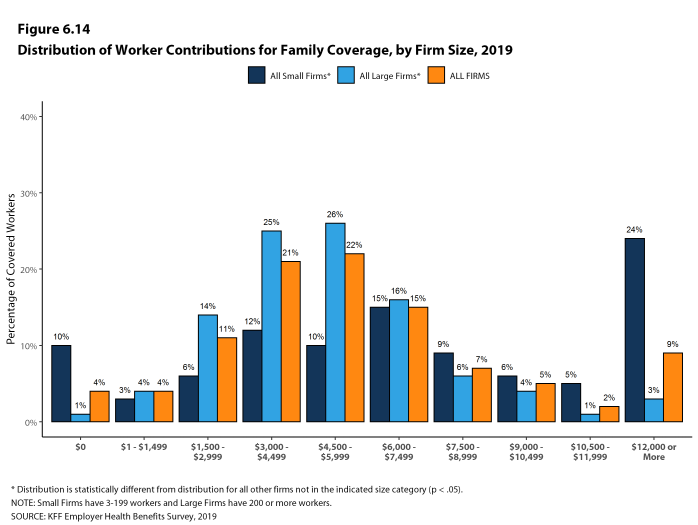

Thirty-one percent of covered workers in small firms are in a plan where the employer pays the entire premium for single coverage, compared to only 5% of covered workers in large firms. In contrast, 35% of covered workers in small firms are in a plan where they must contribute more than one-half of the premium for family coverage, compared to 6% of covered workers in large firms [Figure D].

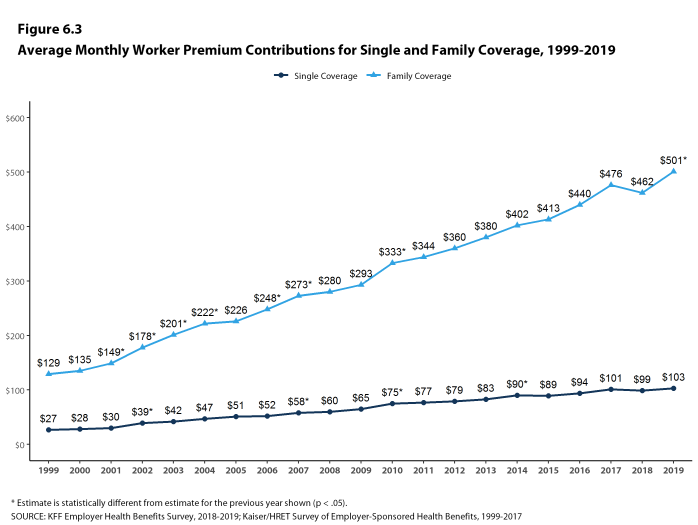

The average annual dollar amounts contributed by covered workers for 2019 are $1,242 for single coverage and $6,015 for family coverage. The average dollar contribution for family coverage has increased 25% since 2014 and 71% since 2009 [Figure A]. Average contribution amounts for covered workers in HDHP/SOs are lower than the average overall contribution amounts for both single and family coverage [Figure B]. Nine percent of covered workers, including 24% of covered workers in small firms, are in a plan with a worker contribution of $12,000 or more for family coverage.

Figure C: Average Annual Worker and Employer Contributions to Premiums and Total Premiums for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Wage Level, 2019

Figure D: Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 2019

PLAN ENROLLMENT

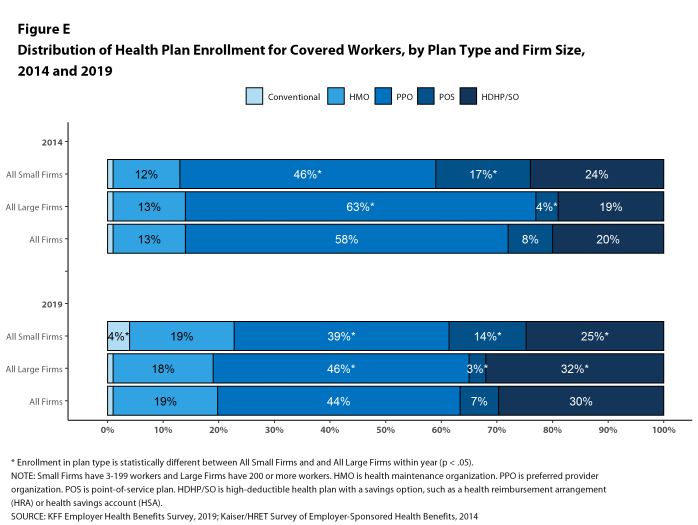

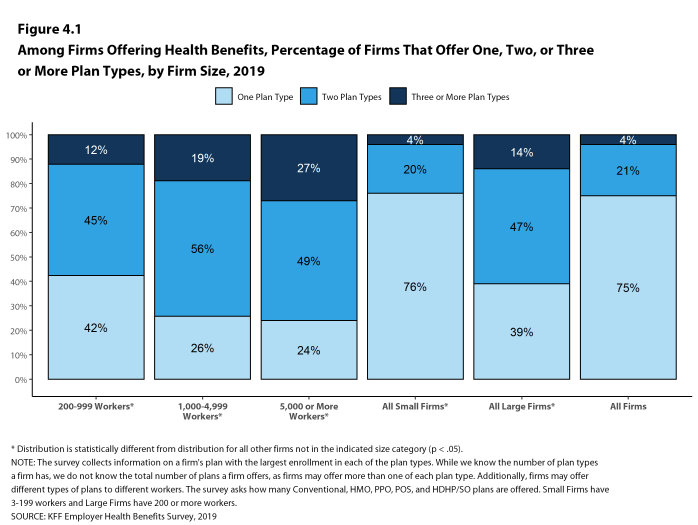

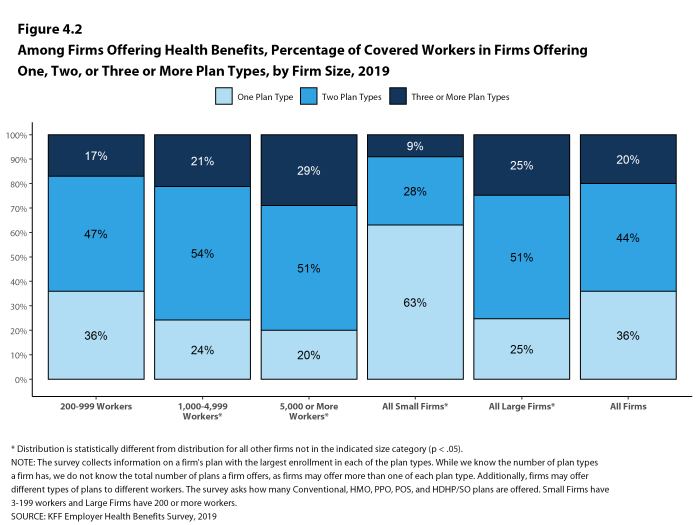

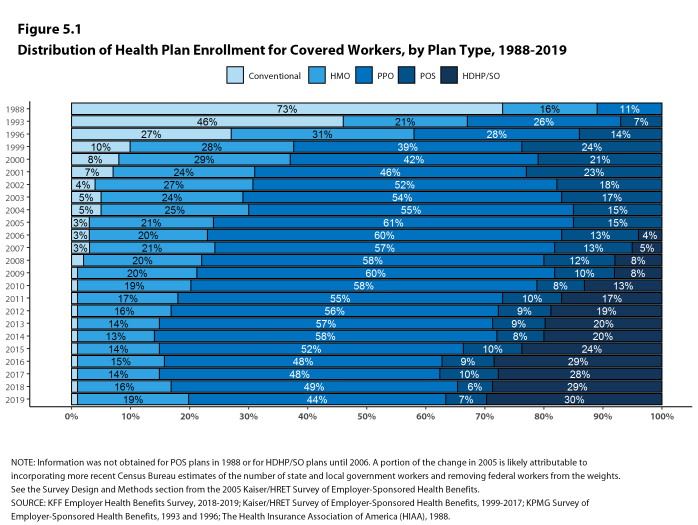

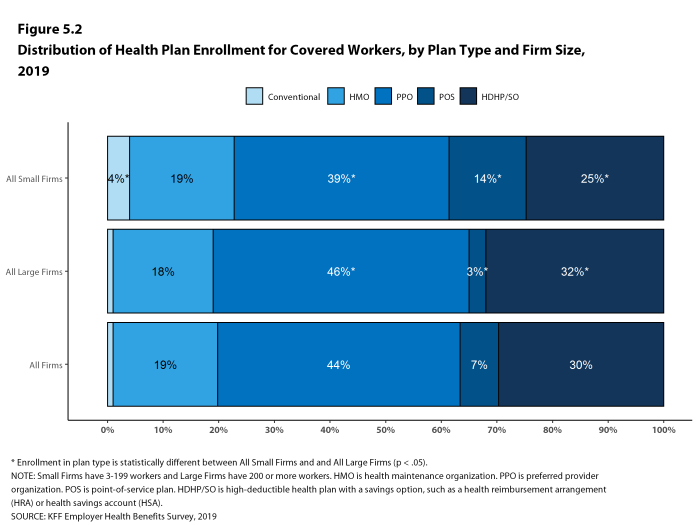

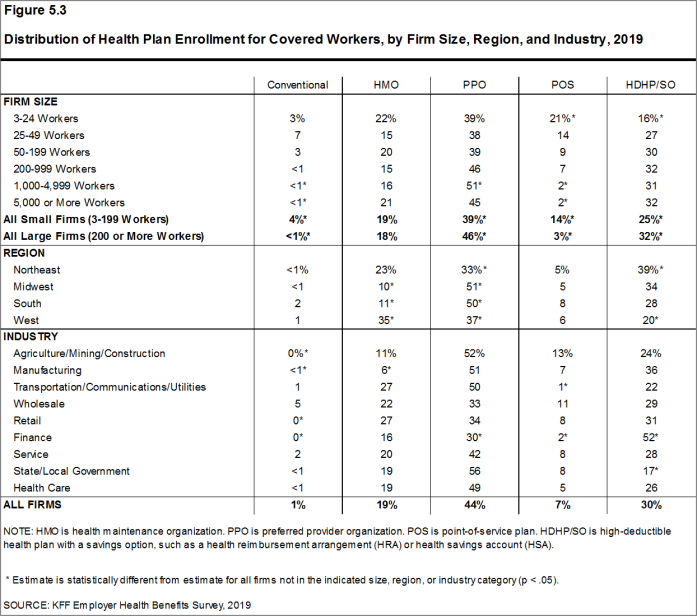

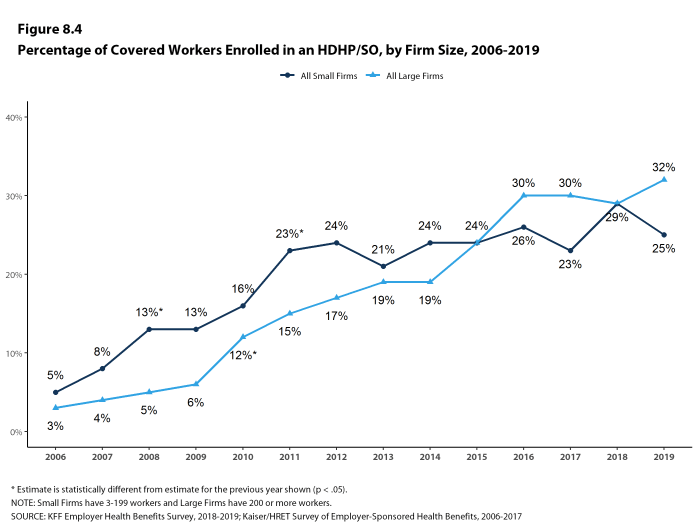

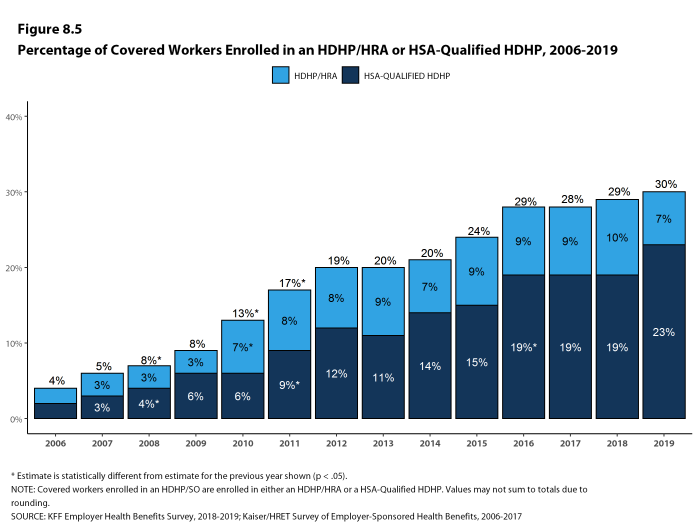

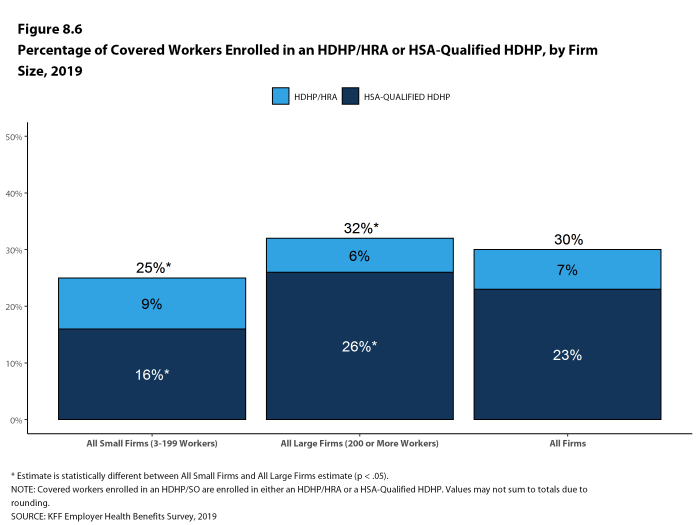

PPOs continue to be the most common plan type, enrolling 44% of covered workers in 2019. Thirty percent of covered workers are enrolled in a high-deductible plan with a savings option (HDHP/SO), 19% in an HMO, 7% in a POS plan, and 1% in a conventional (also known as an indemnity) plan [Figure E].

Figure E: Distribution of Health Plan Enrollment for Covered Workers, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2014 and 2019

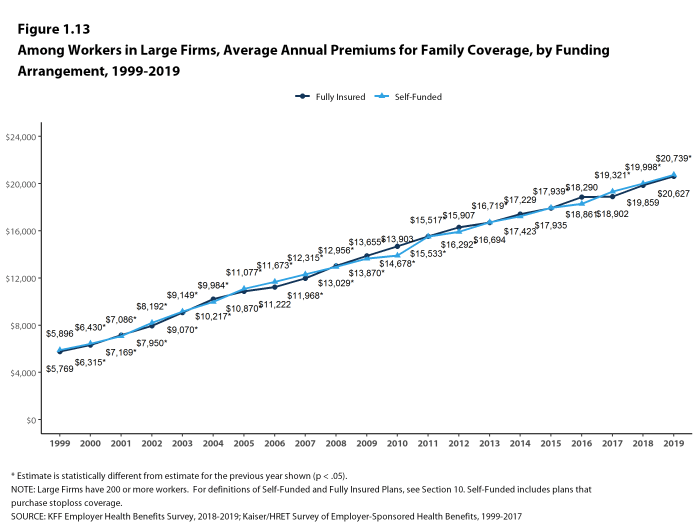

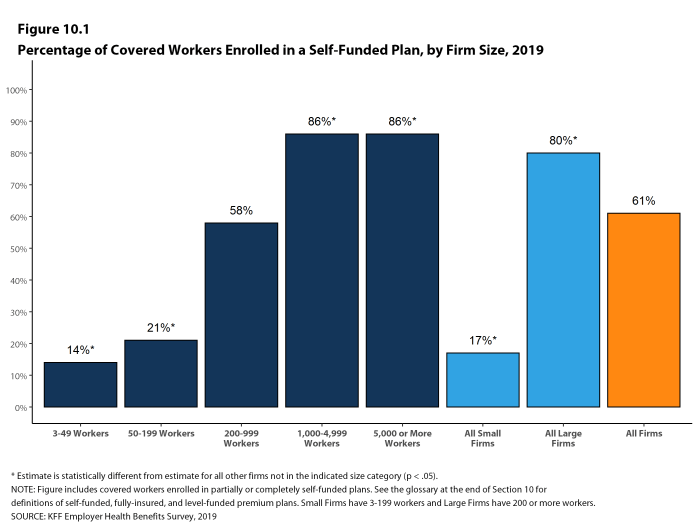

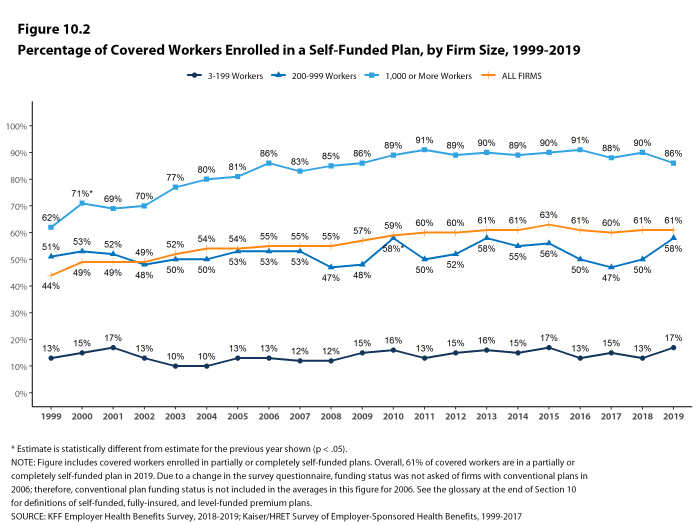

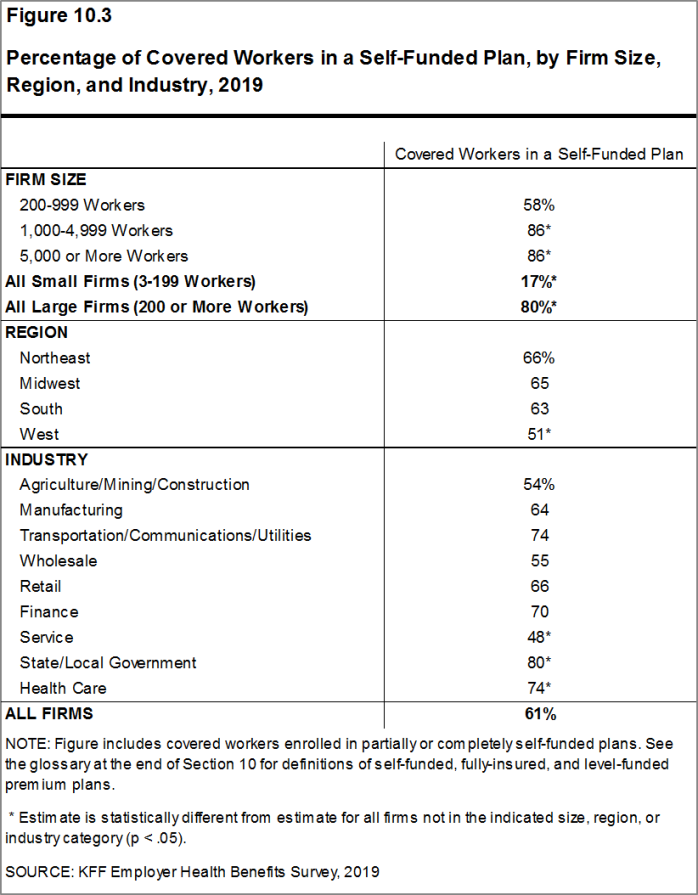

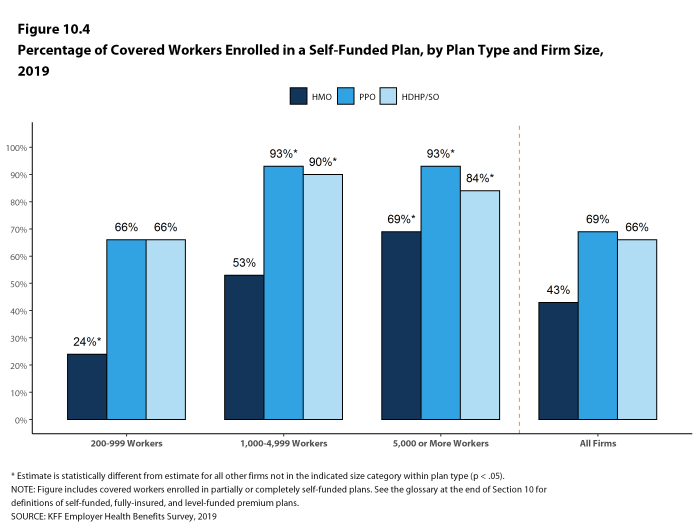

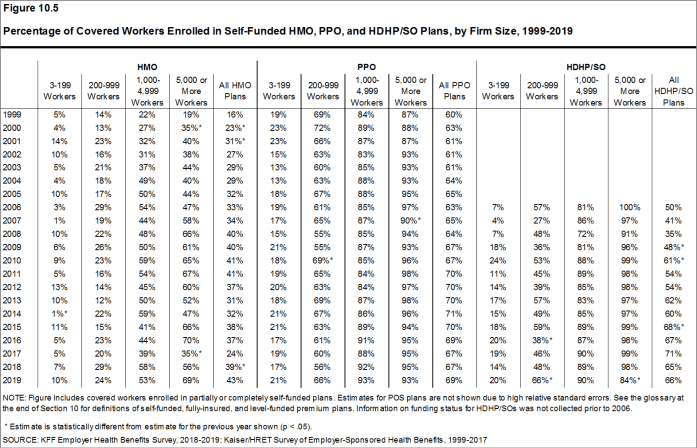

Self-Funding. Sixty-one percent of covered workers, including 17% of covered workers in small firms and 80% in large firms, are enrolled in plans that are either partially or completely self-funded.

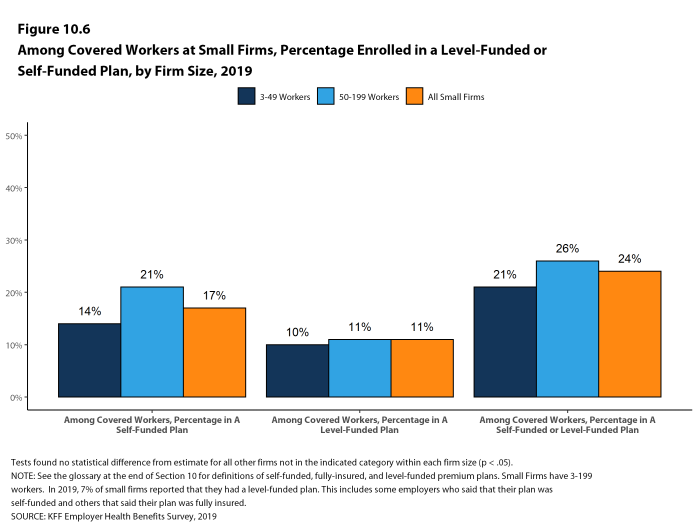

Seven percent of small firms report that they have a level-funded plan. These arrangements combine a relatively small self-funded component with stoploss insurance with low attachment points that may transfer a substantial share of the risk to insurers. These arrangements are complex and some small employers may not be entirely certain about the funding status of their plans.

EMPLOYEE COST SHARING

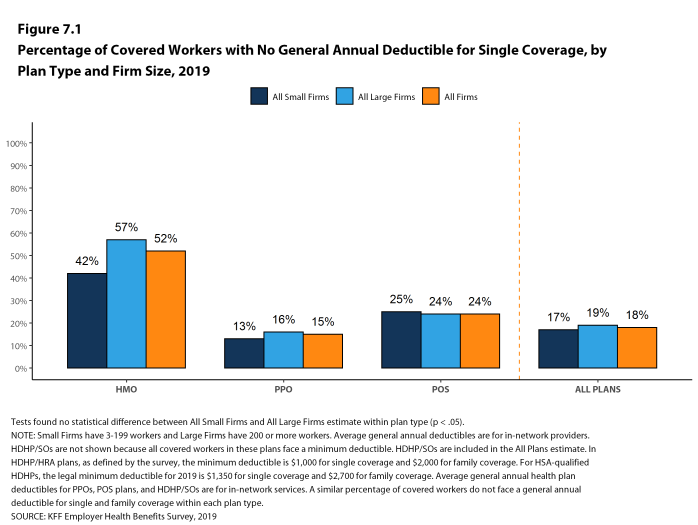

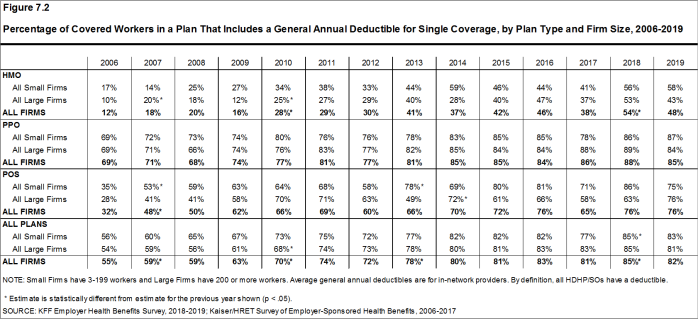

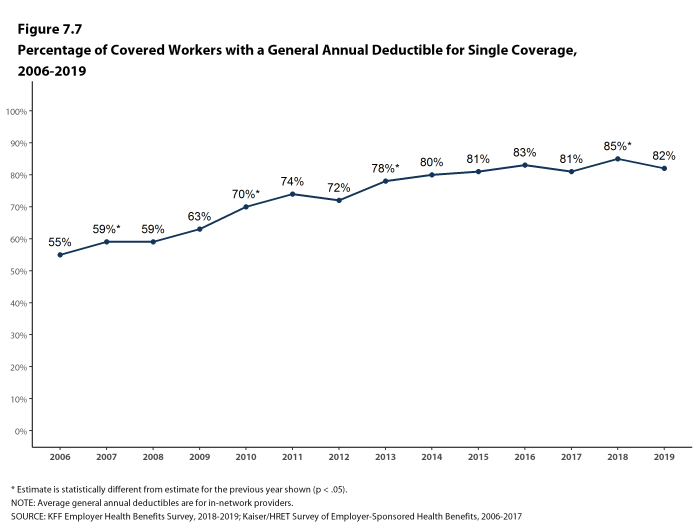

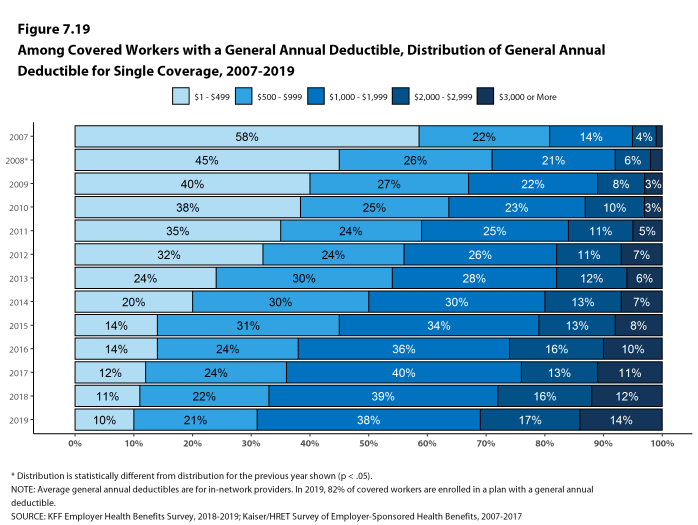

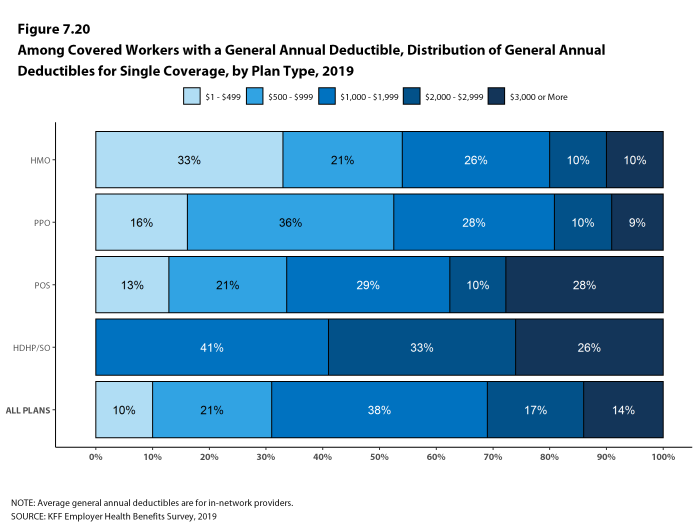

Most covered workers must pay a share of the cost when they use health care services. Eighty-two percent of covered workers have a general annual deductible for single coverage that must be met before most services are paid for by the plan.

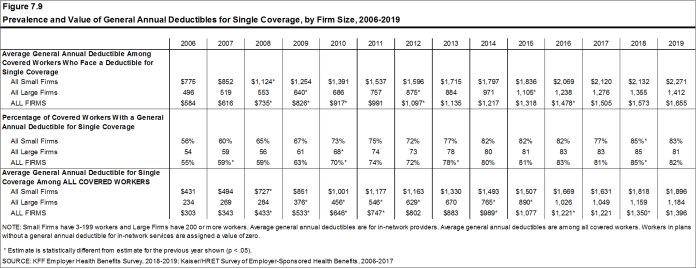

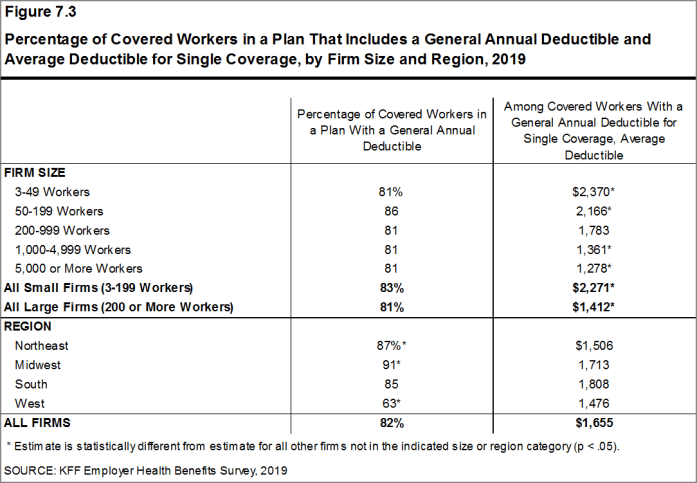

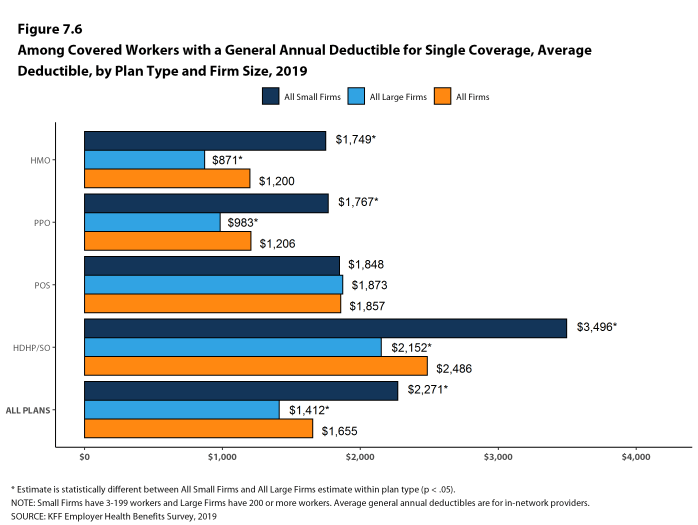

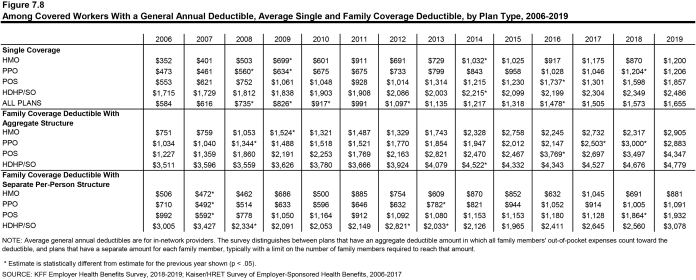

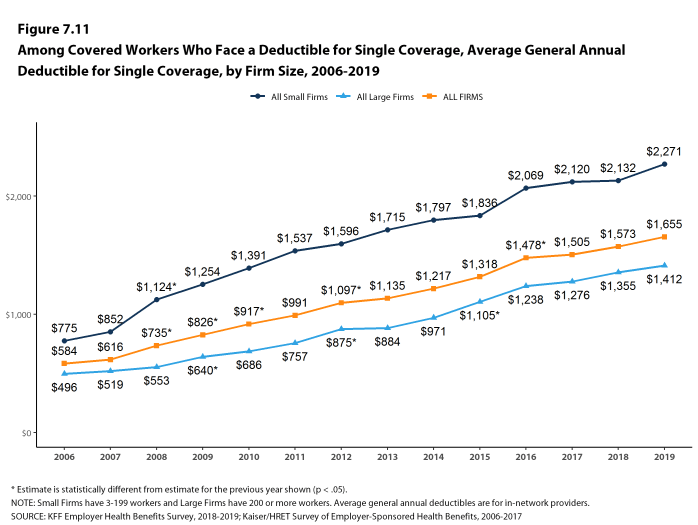

Among covered workers with a general annual deductible, the average deductible amount for single coverage is $1,655, similar to the average deductible last year. The average deductible for covered workers is higher in small firms than large firms ($2,271 vs. $1,412). The average annual deductible among covered workers with a deductible has increased 36% over the last five years and 100% over the last ten years.

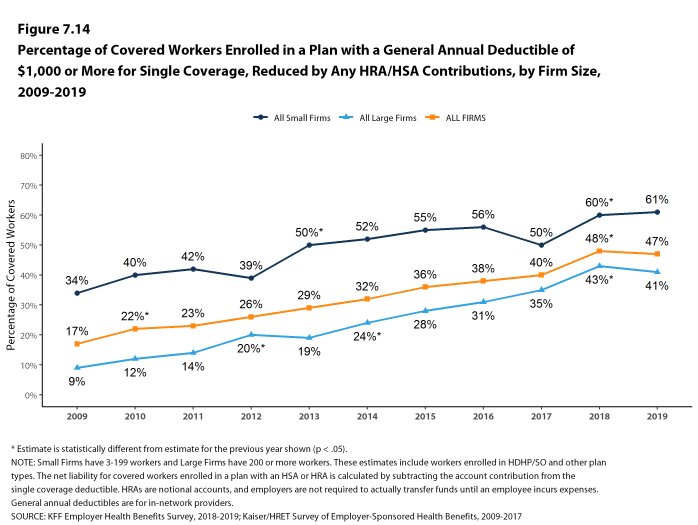

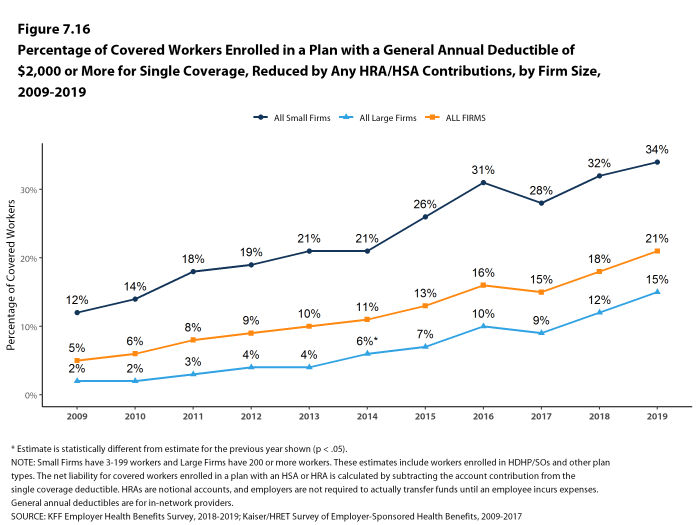

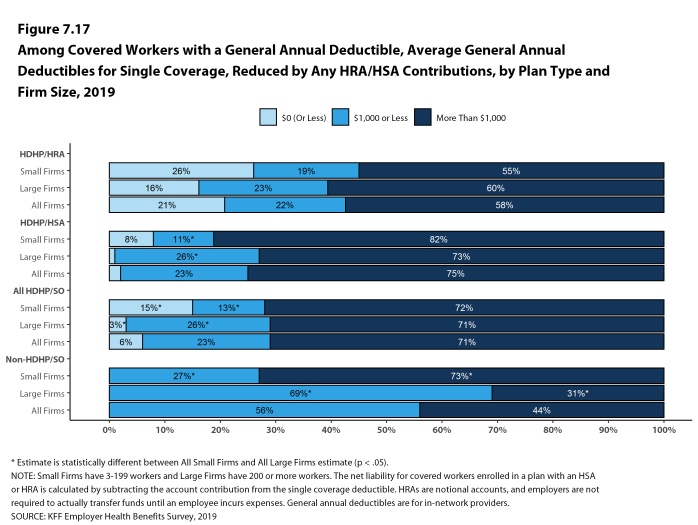

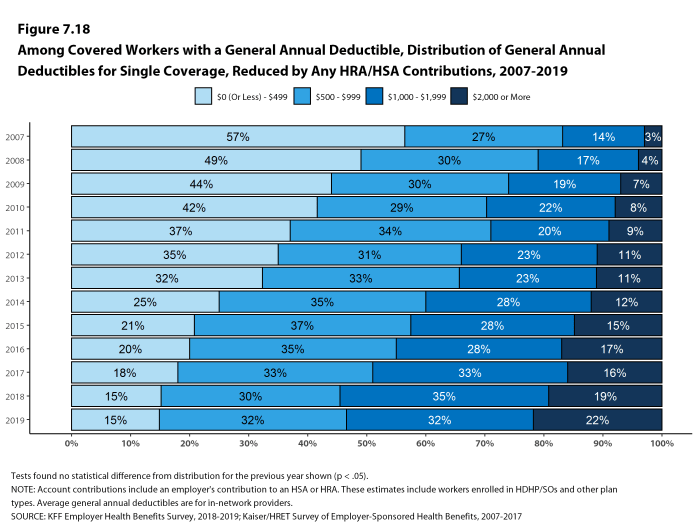

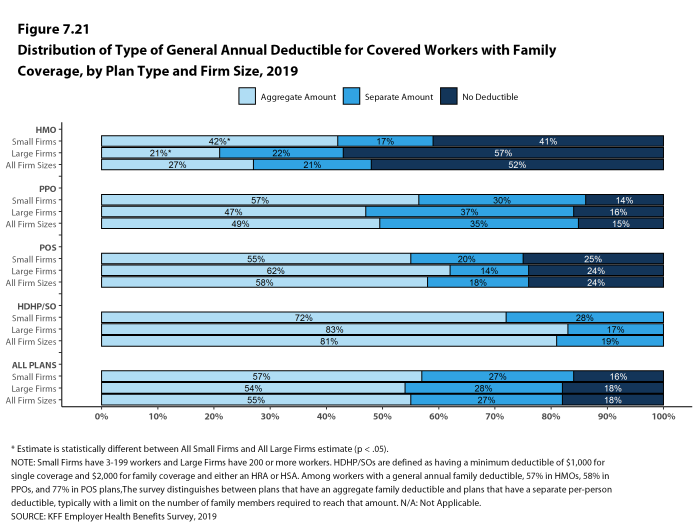

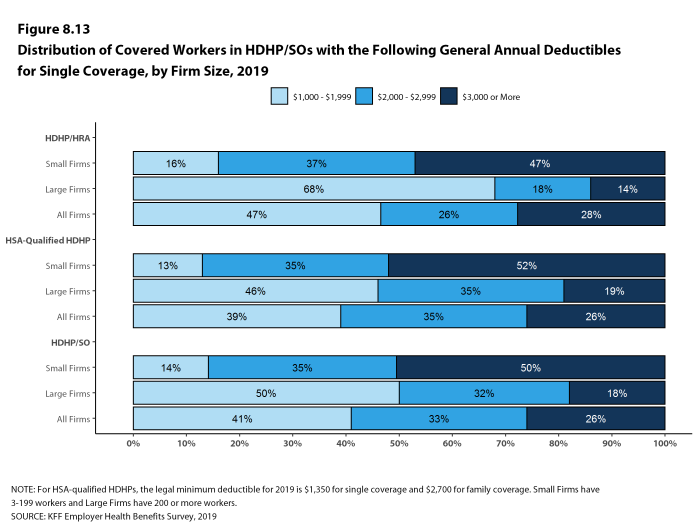

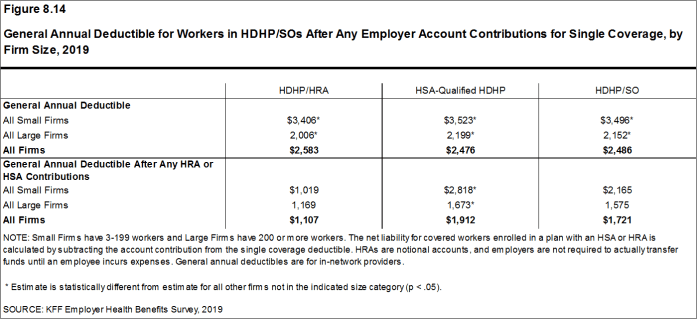

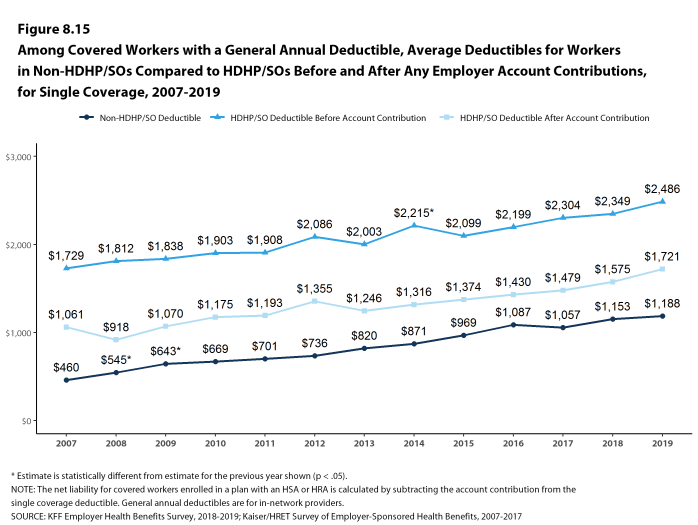

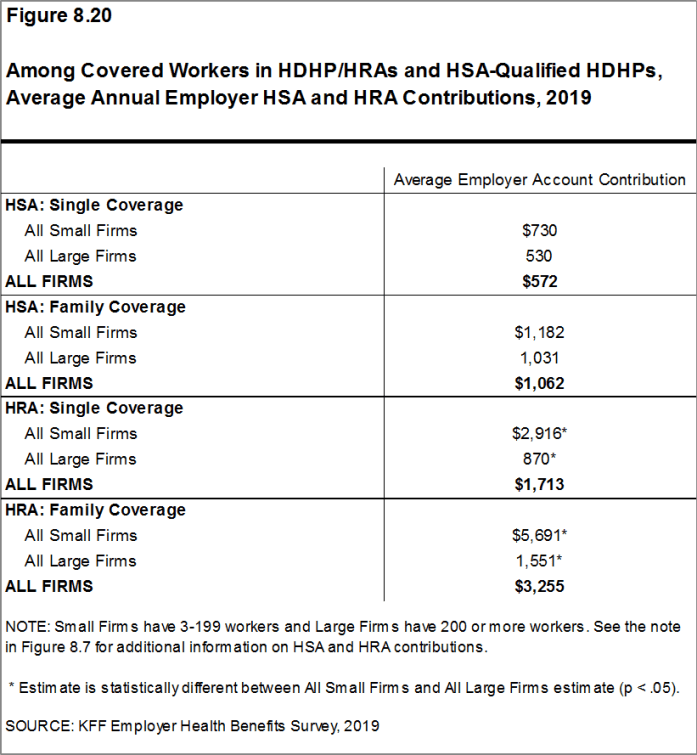

Deductibles have increased in recent years due to higher deductibles within plan types and higher enrollment in HDHP/SOs. While growing deductibles in PPOs and other plan types generally increase enrollee out-of-pocket liability, the shift to enrollment in HDHP/SOs does not necessarily do so because many HDHP/SO enrollees receive an account contribution from their employers. Twenty-one percent of covered workers in an HDHP with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA), and 2% of covered workers in a Health Savings Account (HSA)-qualified HDHP receive an account contribution for single coverage at least equal to their deductible, while another 22% of covered workers in an HDHP with an HRA and 23% of covered workers in an HSA-qualified HDHP receive account contributions that, if applied to their deductible, would reduce their actual liability to less than $1,000.

The 2019 value is 41% higher than the average general annual deductible of $989 in 2014 and 162% higher than the average general annual deductible of $533 in 2009.

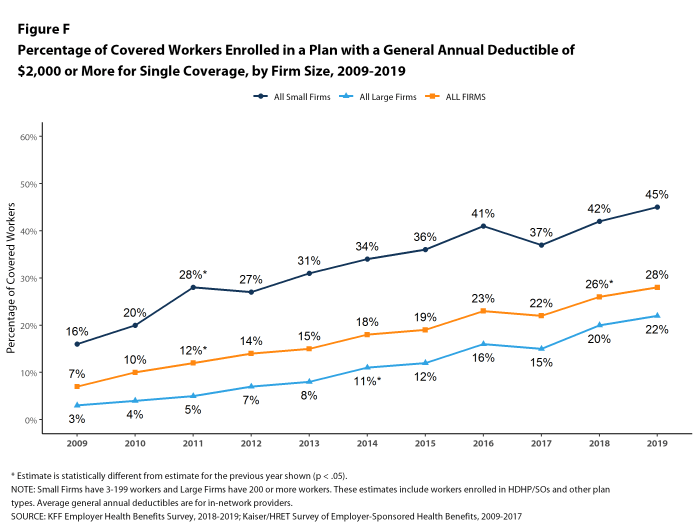

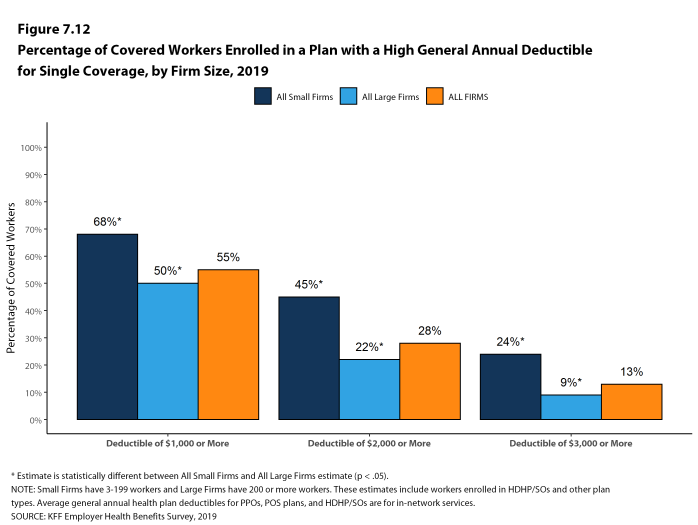

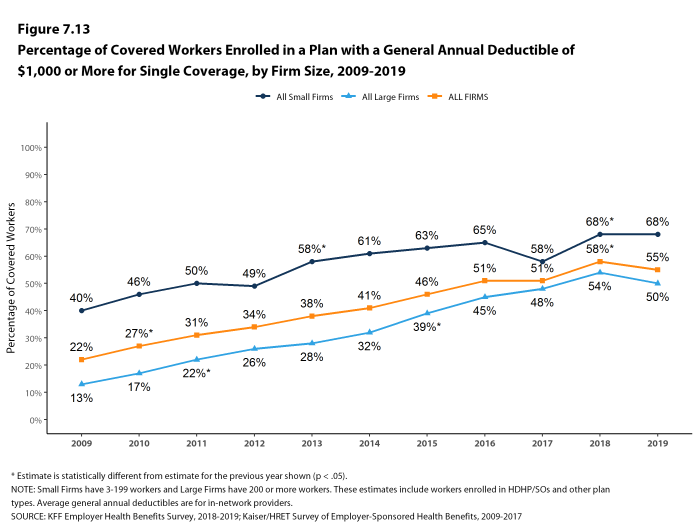

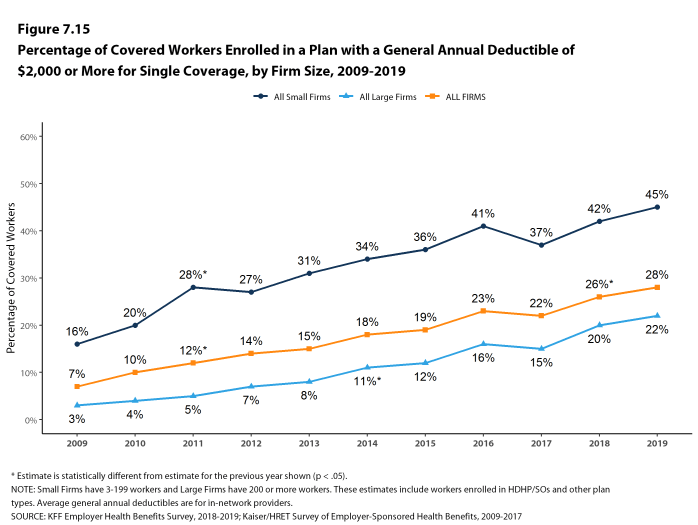

Another way to look at deductibles is the percentage of all covered workers who are in a plan with a deductible that exceeds certain thresholds. Over the past five years, the percentage of covered workers with a general annual deductible of $2,000 or more for single coverage has grown from 18% to 28% [Figure F].

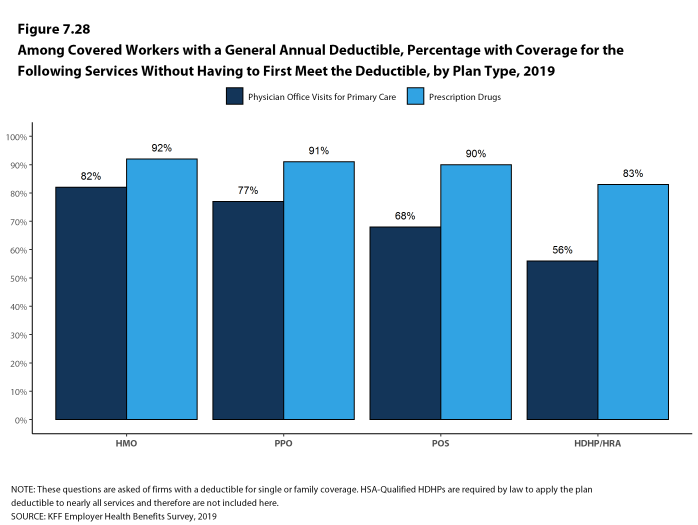

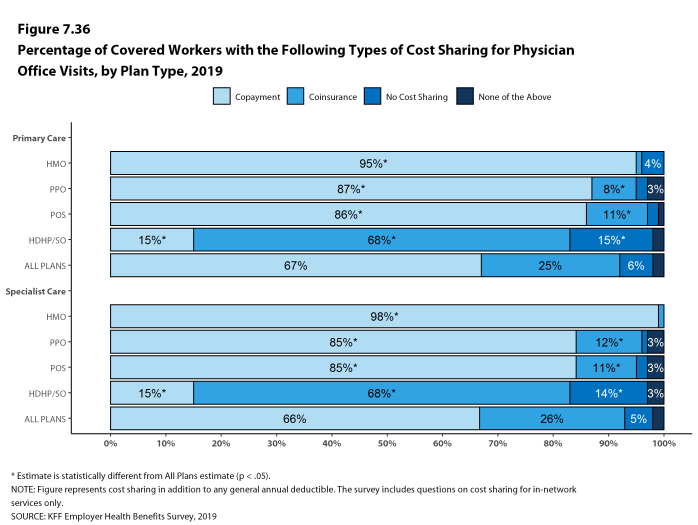

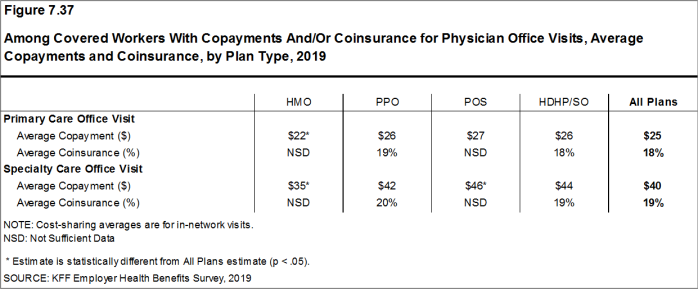

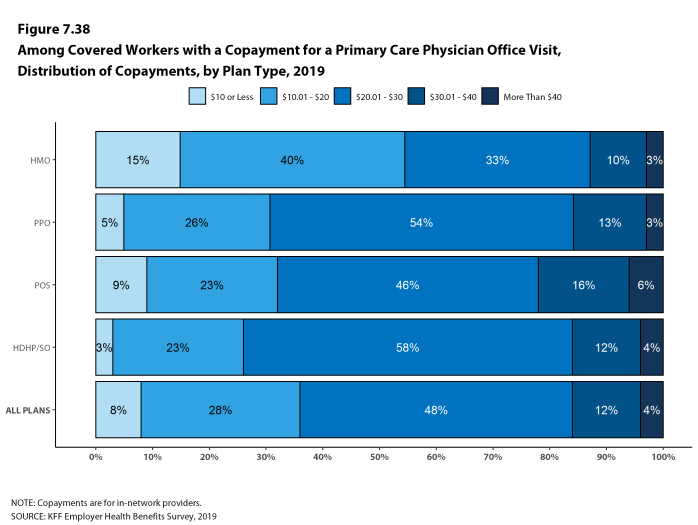

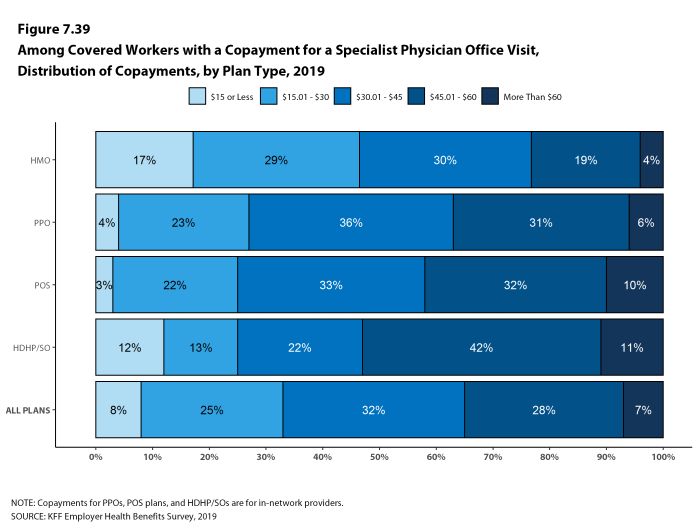

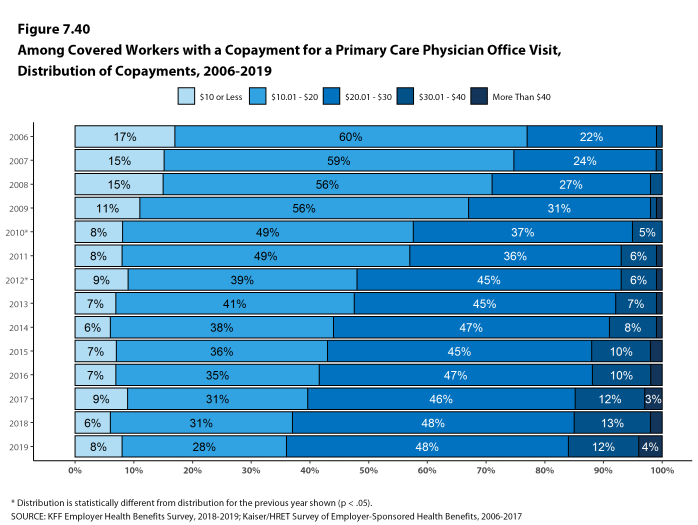

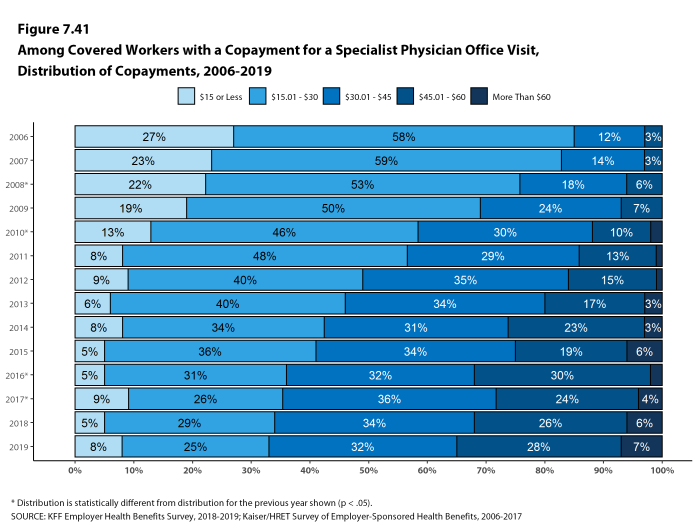

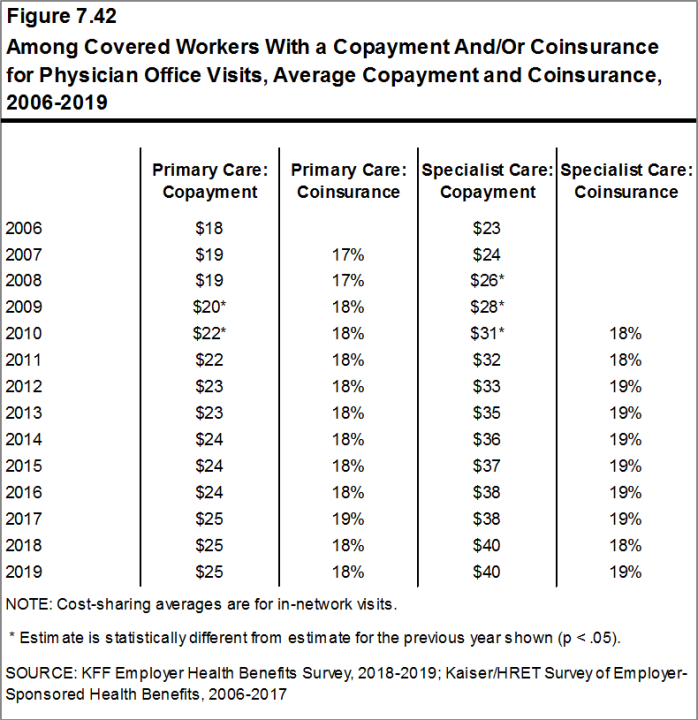

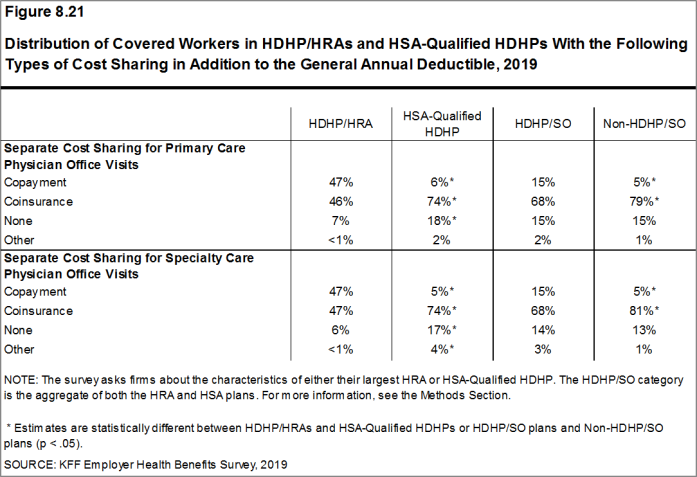

A large share of covered workers also pay a portion of the cost when they visit an in-network physician. Most covered workers face a copayment (a fixed dollar amount) when they visit a doctor, although some workers face coinsurance requirements (a percentage of the covered amount). The average copayments are $25 for primary care and $40 for specialty care. The average coinsurance rates are 18% for primary care and 19% for specialty care. These amounts are similar to those in 2018.

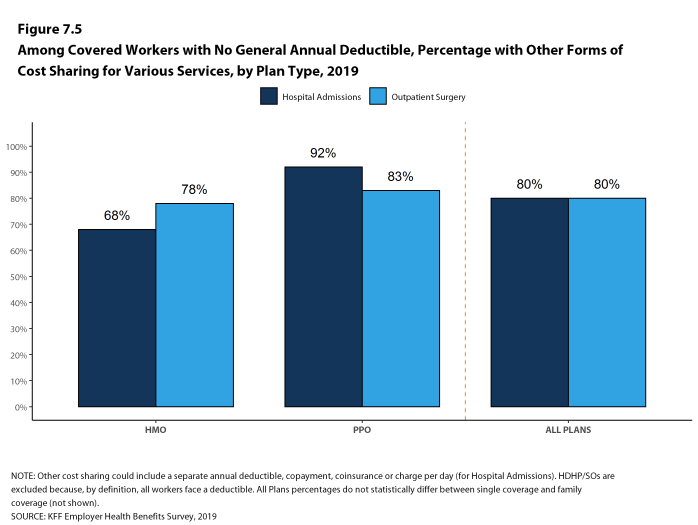

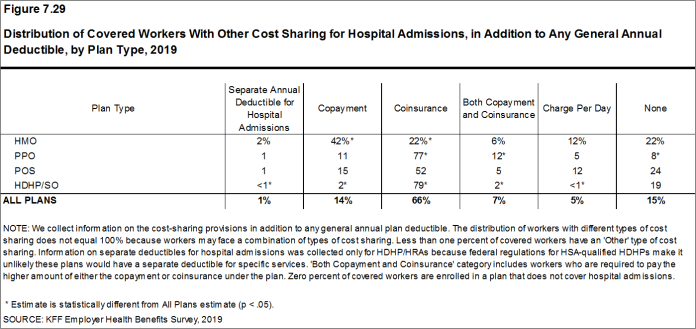

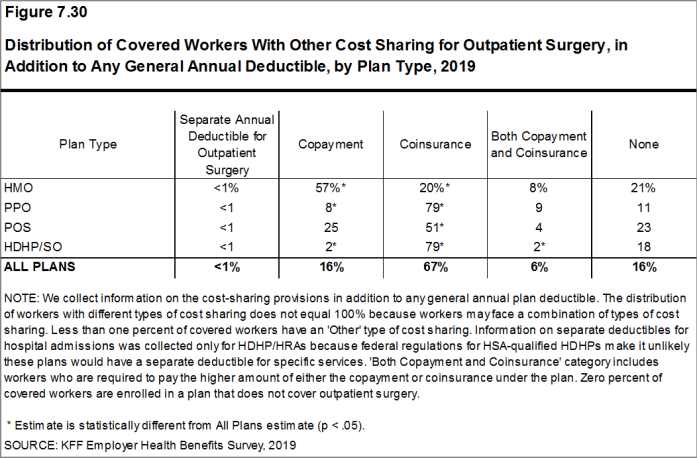

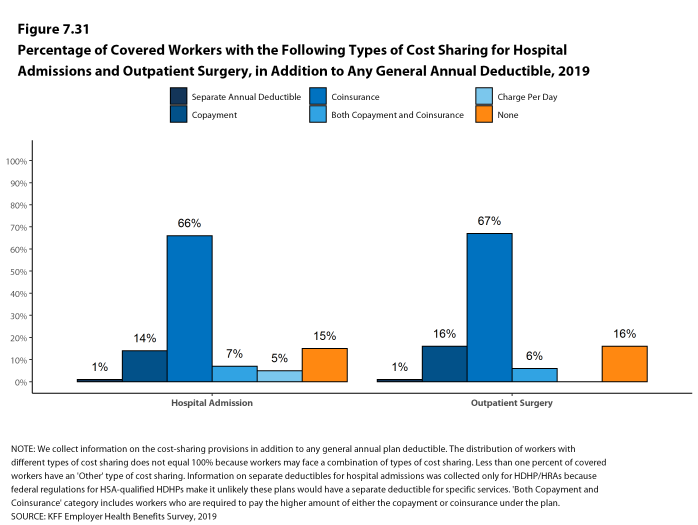

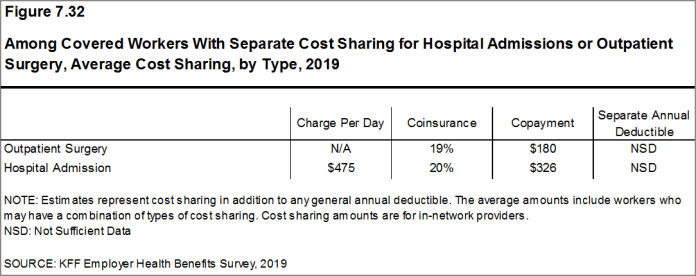

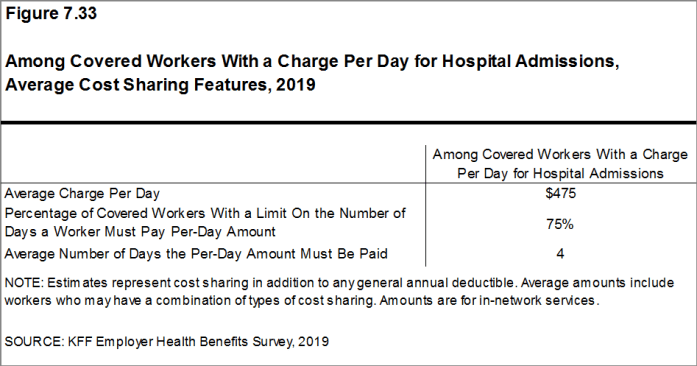

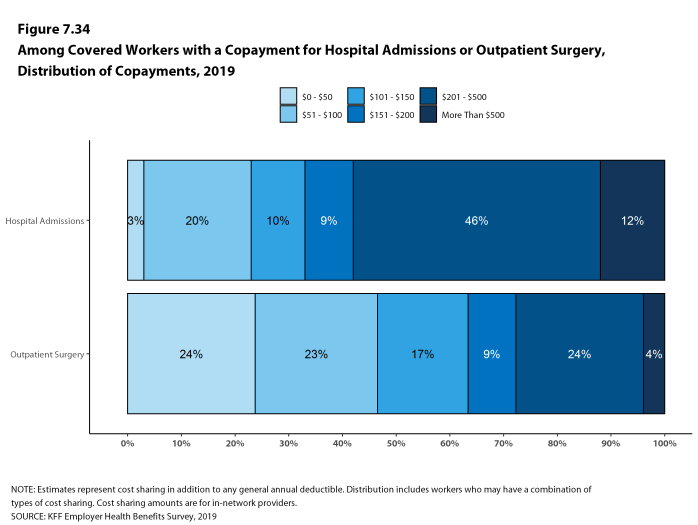

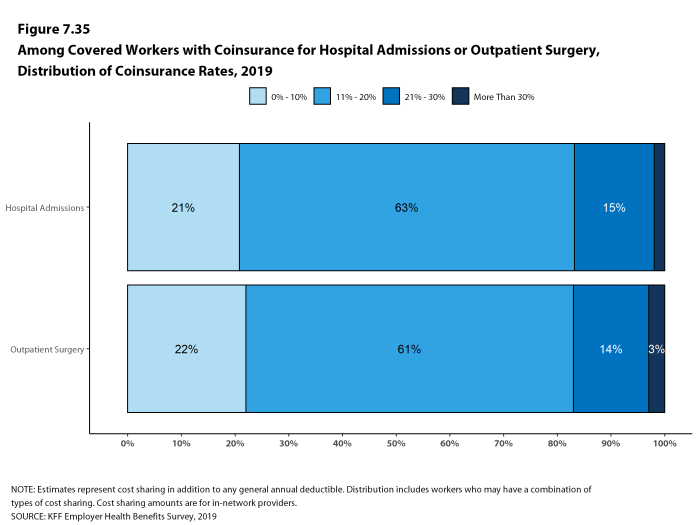

Most workers also face additional cost sharing for a hospital admission or outpatient surgery. Sixty-six percent of covered workers have coinsurance and 14% have a copayment for hospital admissions. The average coinsurance rate for a hospital admission is 20% and the average copayment is $326 per hospital admission. The cost-sharing provisions for outpatient surgery follow a similar pattern to those for hospital admissions.

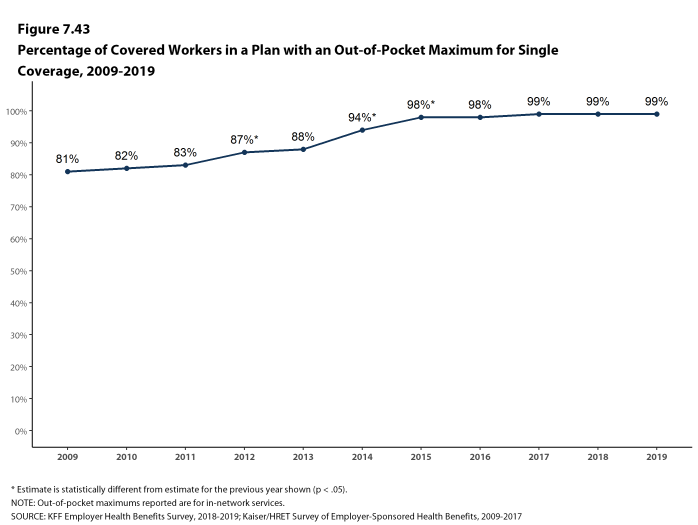

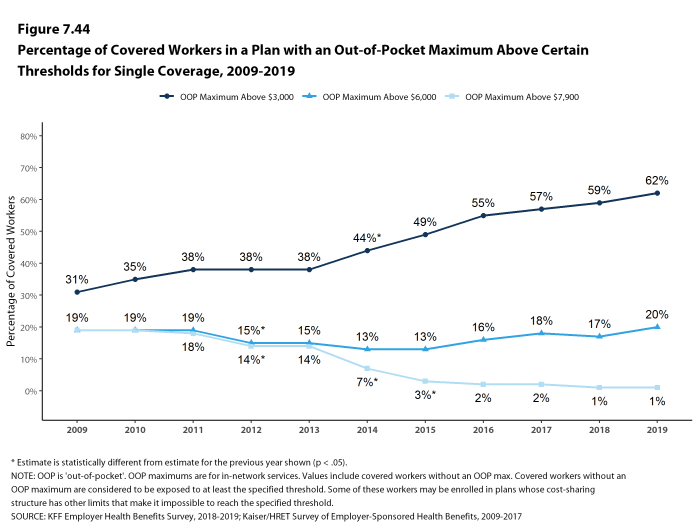

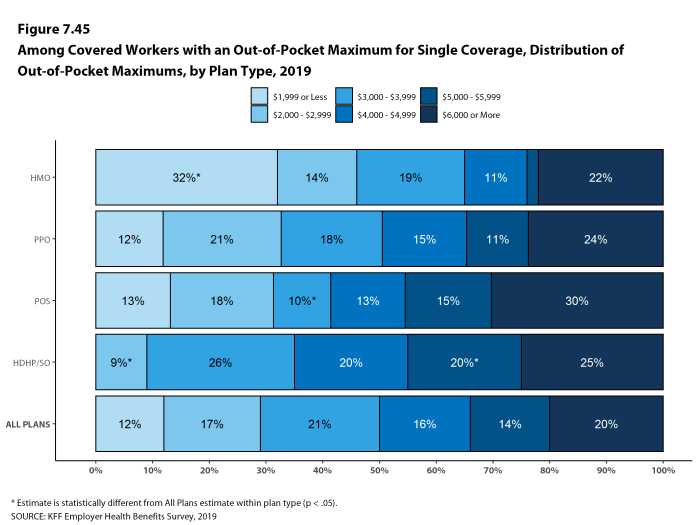

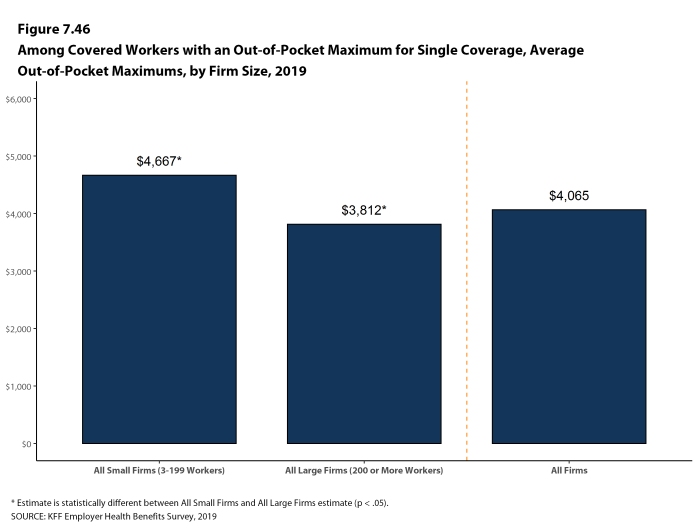

Almost all (99%) covered workers are in plans with a limit on in-network cost sharing (called an out-of-pocket maximum) for single coverage, though the limits vary significantly. Among covered workers in plans with an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage, 12% are in a plan with an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $2,000, while 20% are in a plan with an out-of-pocket maximum of $6,000 or more.

Figure F: Percentage of Covered Workers Enrolled in a Plan With a General Annual Deductible of $2,000 or More for Single Coverage, by Firm Size, 2009-2019

AVAILABILITY OF EMPLOYER-SPONSORED COVERAGE

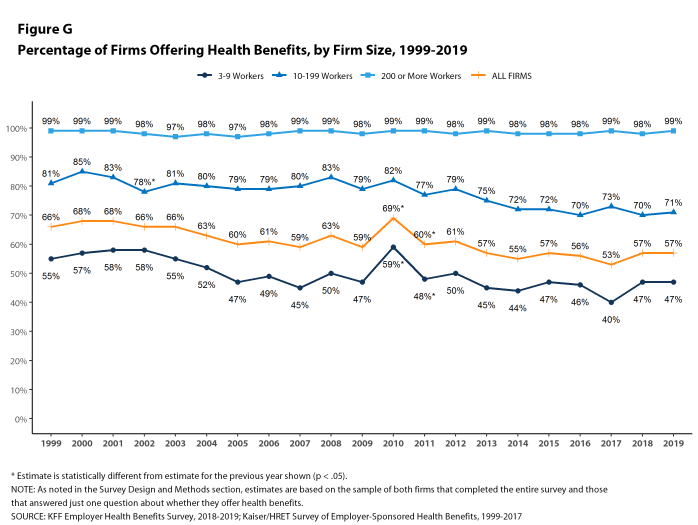

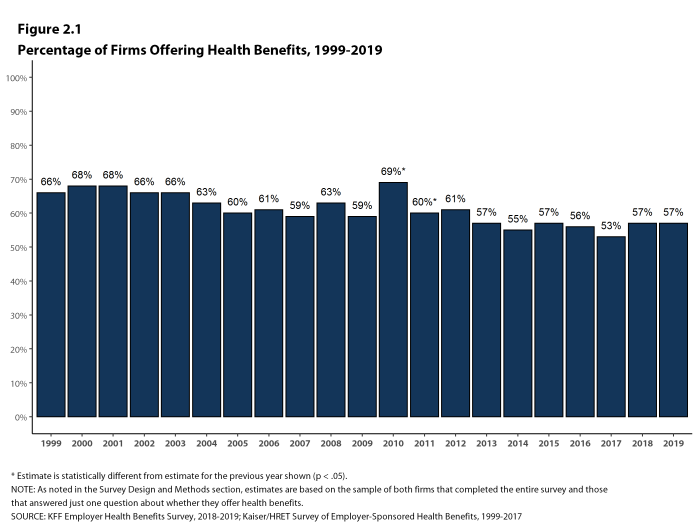

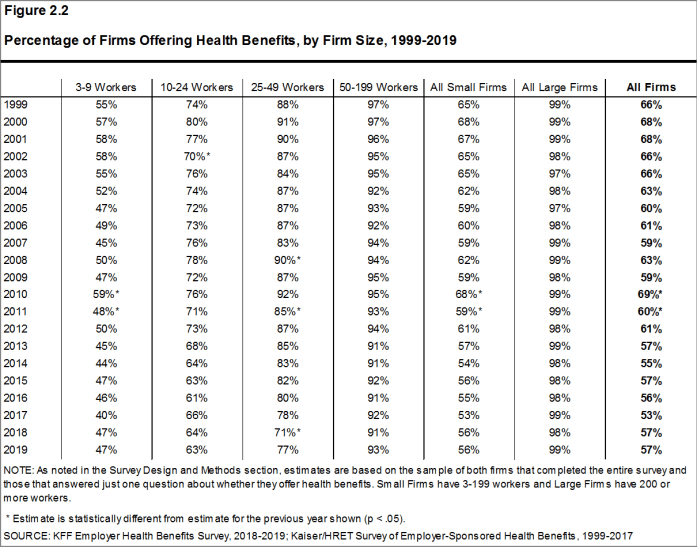

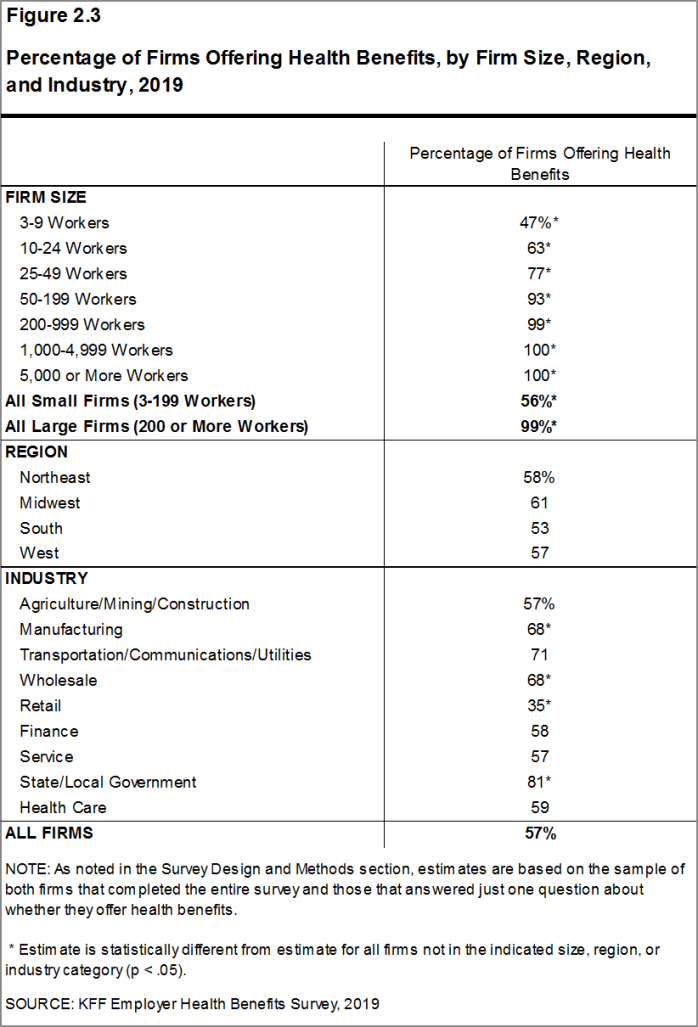

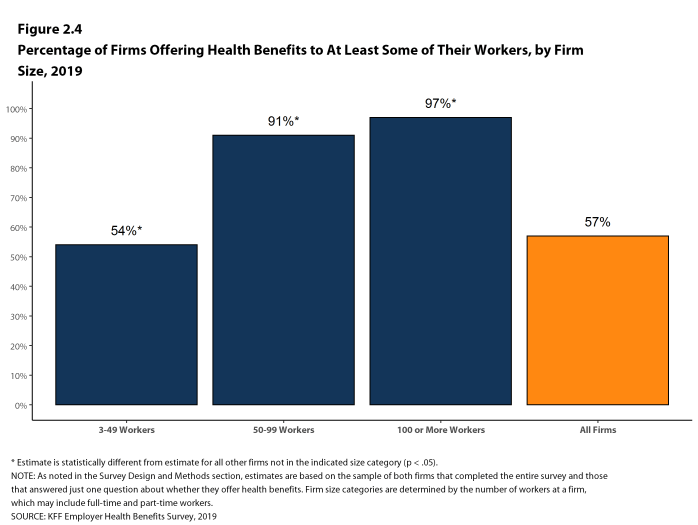

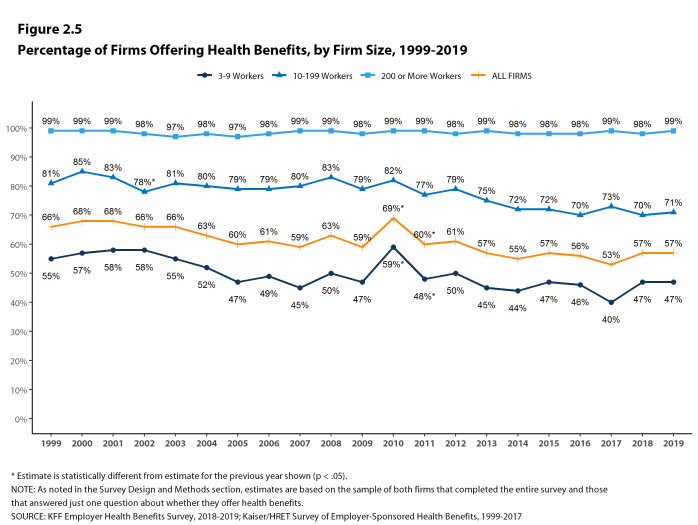

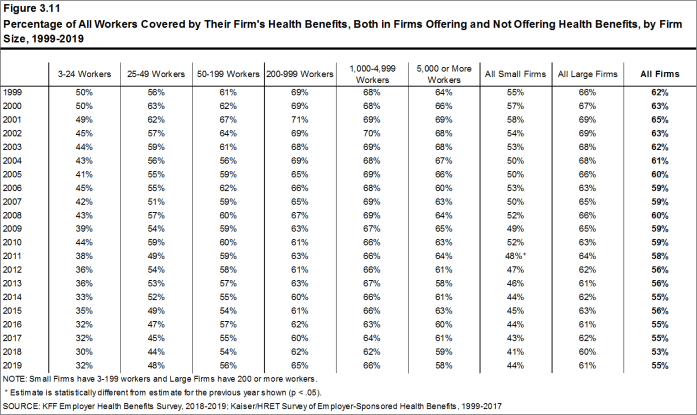

Fifty-seven percent of firms offer health benefits to at least some of their workers, similar to the percentage last year [Figure G]. The likelihood of offering health benefits differs significantly by firm size; only 47% of firms with 3 to 9 workers offer coverage, while virtually all firms with 1,000 or more workers offer coverage.

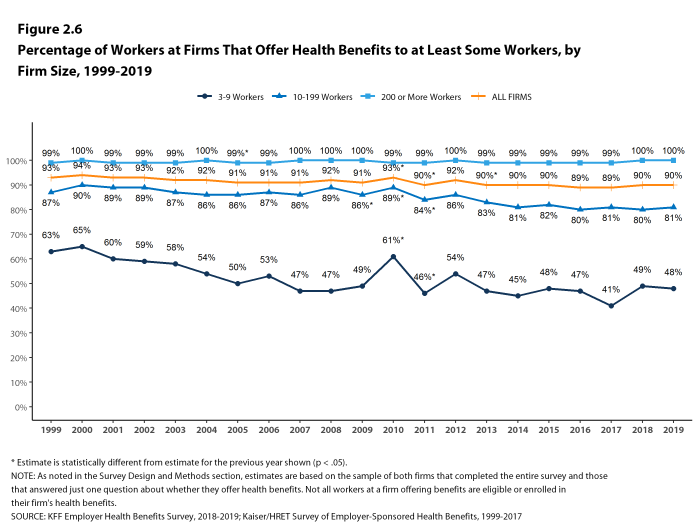

While the vast majority of firms are small, most workers work for large firms that offer coverage. In 2019, 90% of workers are employed by a firm that offers health benefits to at least some of its workers.

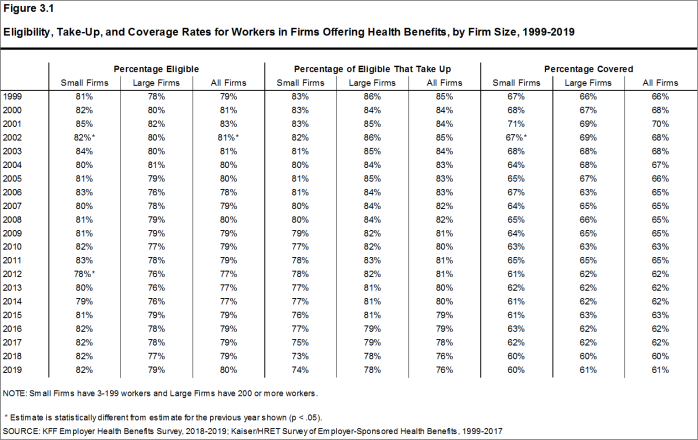

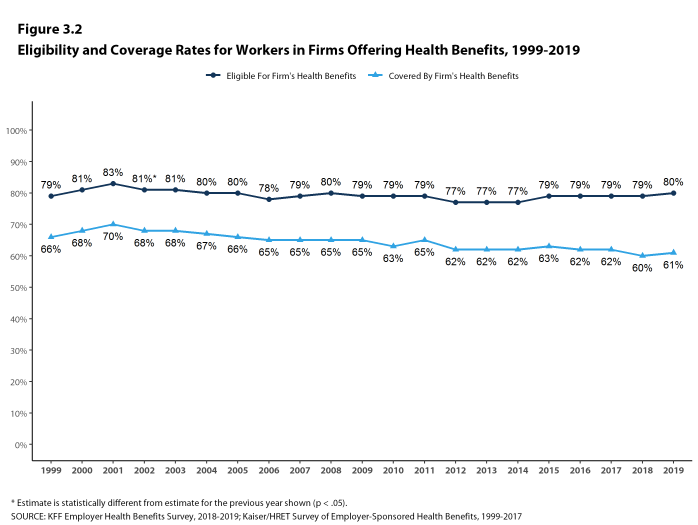

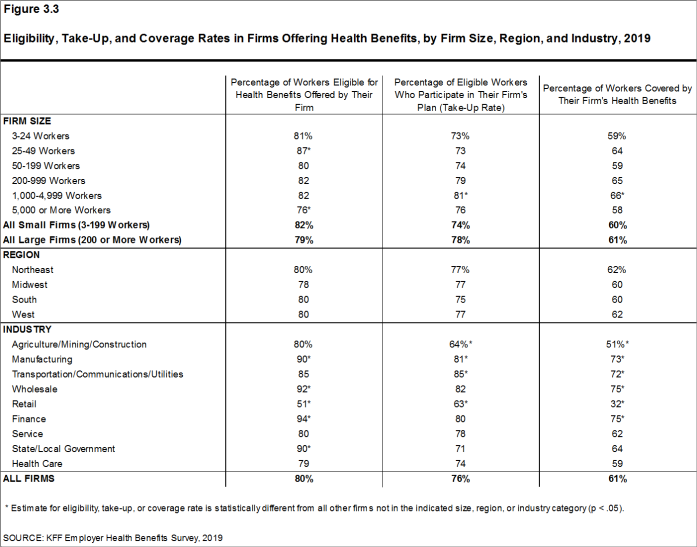

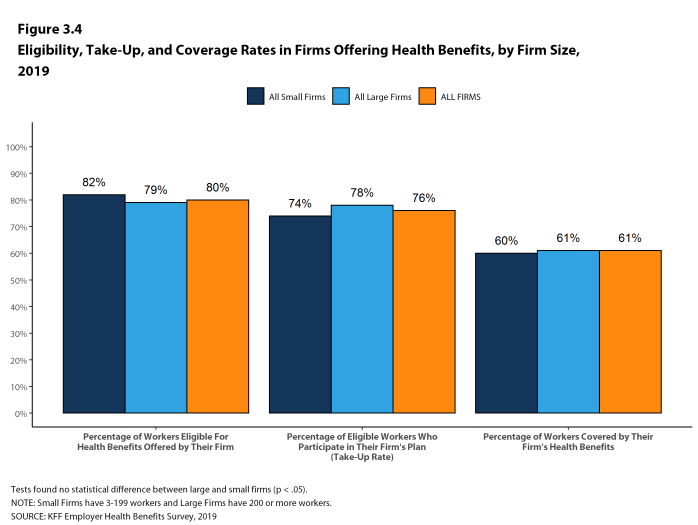

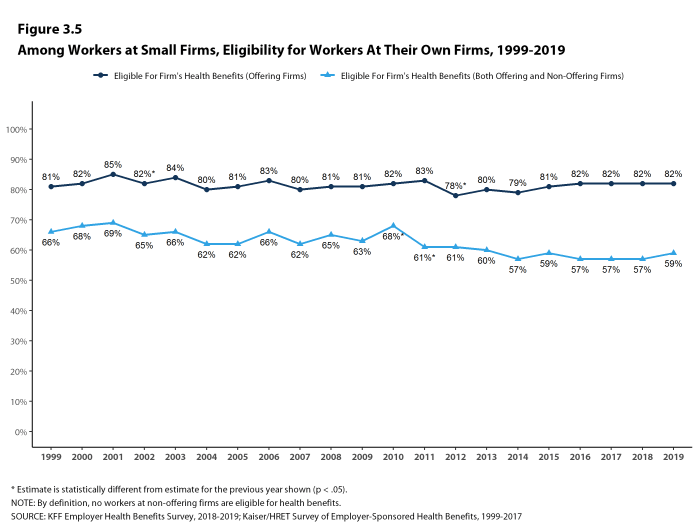

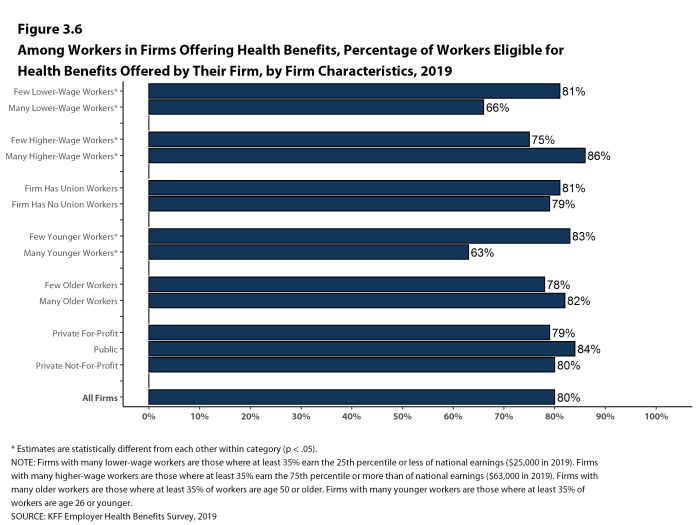

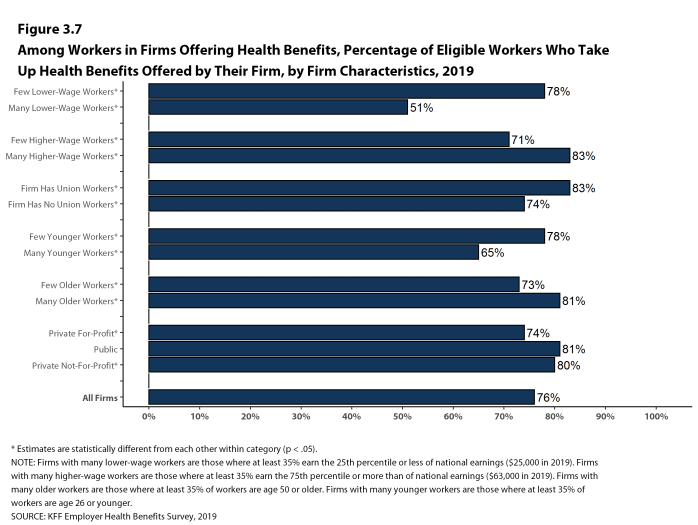

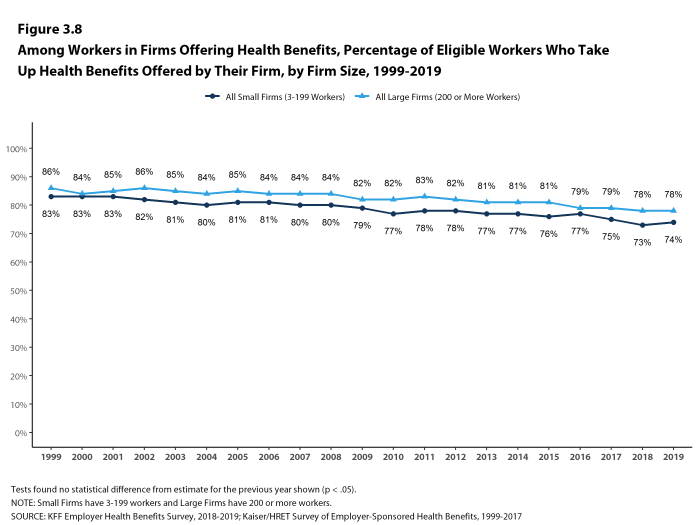

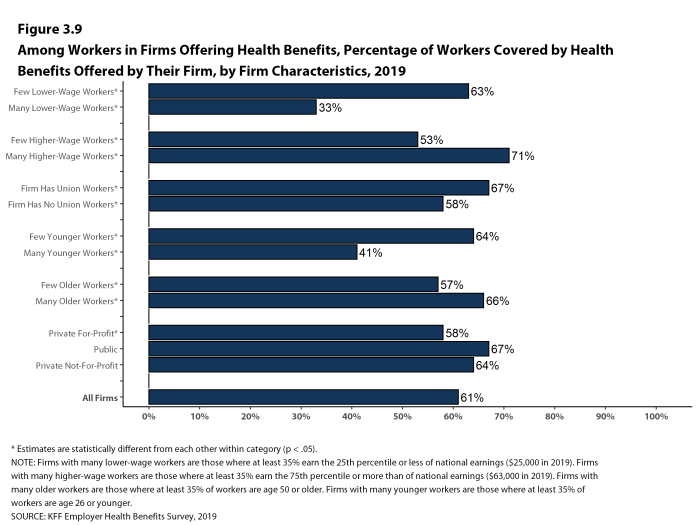

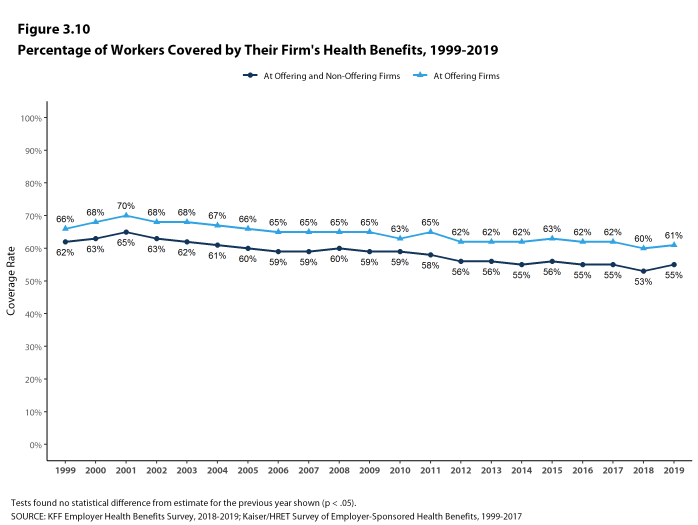

Although the vast majority of workers are employed by firms that offer health benefits, many workers are not covered at their job. Some are not eligible to enroll (e.g., waiting periods or part-time or temporary work status) and others who are eligible choose not to enroll (e.g., they feel the coverage is too expensive or they are covered through another source). In firms that offer coverage, 80% of workers are eligible for the health benefits offered, and of those eligible, 76% take up the firm’s offer, resulting in 61% of workers in offering firms enrolling in coverage through their employer. All of these percentages are similar to 2018.

Looking at workers in both firms that offer and firms that do not offer health benefits, 55% of workers are covered by health plans offered by their employer, similar to the percentage last year.

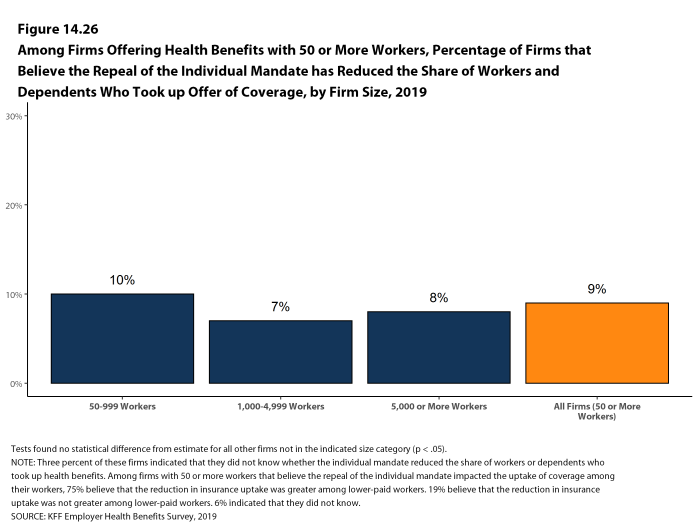

Repeal of the Individual Mandate Beginning in 2019, there is no penalty for individuals who do not maintain health insurance, sometimes called the Individual Mandate. Among firms offering health benefits with at least 50 employees, 9% say that they believed the repeal of the penalty reduced the percentage of employees and dependents that elected the firm’s coverage in 2019. We did not, however, observe a change in the takeup rate for workers offered coverage at their job since last year.

Figure G: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2019

HEALTH AND WELLNESS PROGRAMS

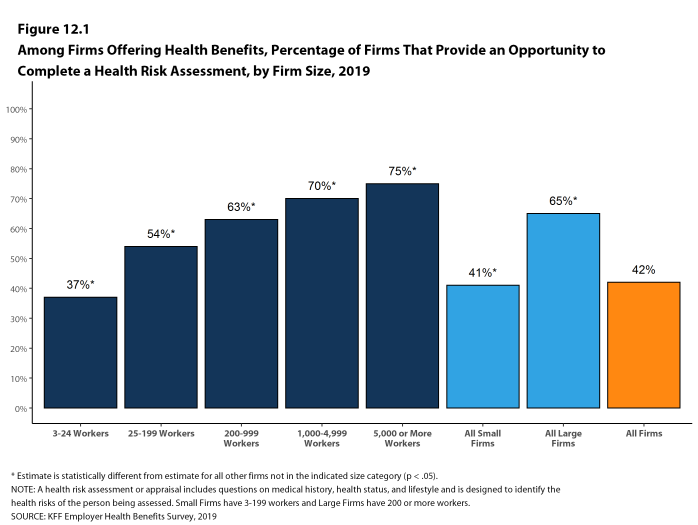

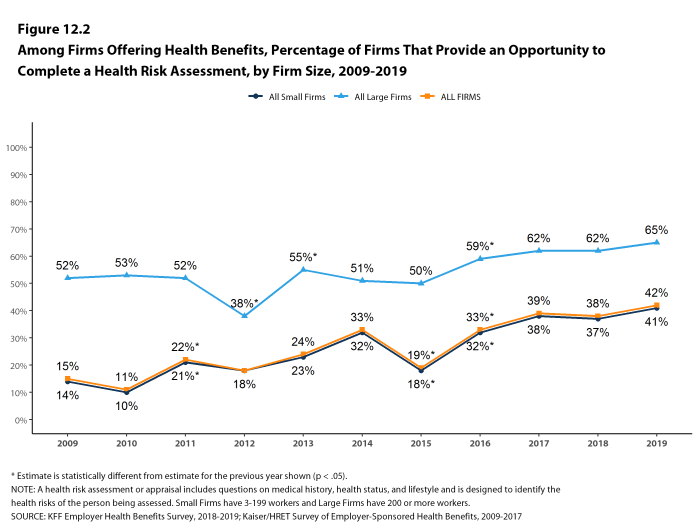

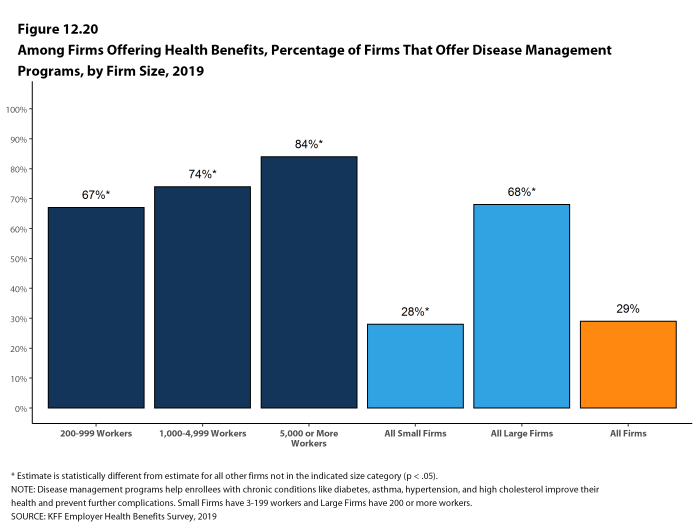

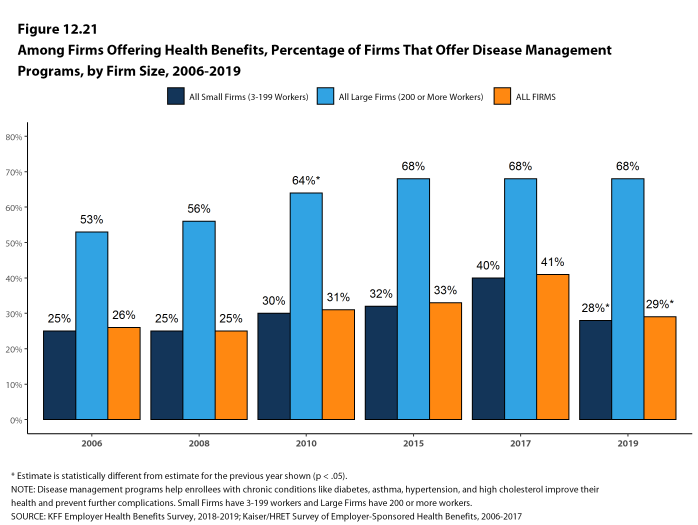

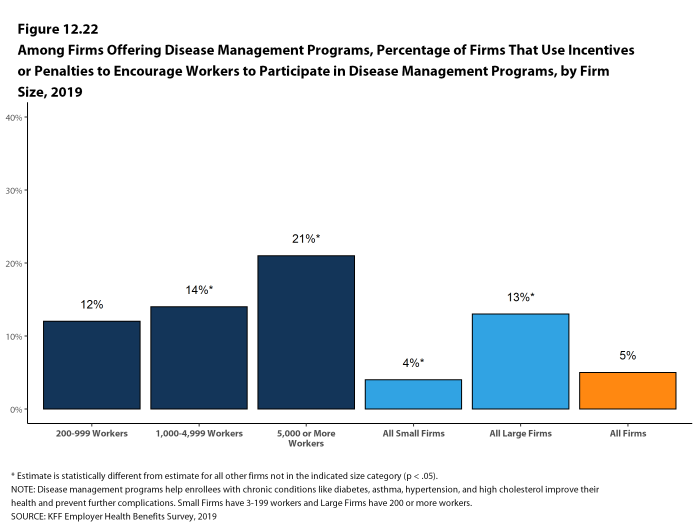

Most large firms and many small firms have programs that help workers identify health issues and manage chronic conditions, including health risk assessments, biometric screenings, and health promotion programs.

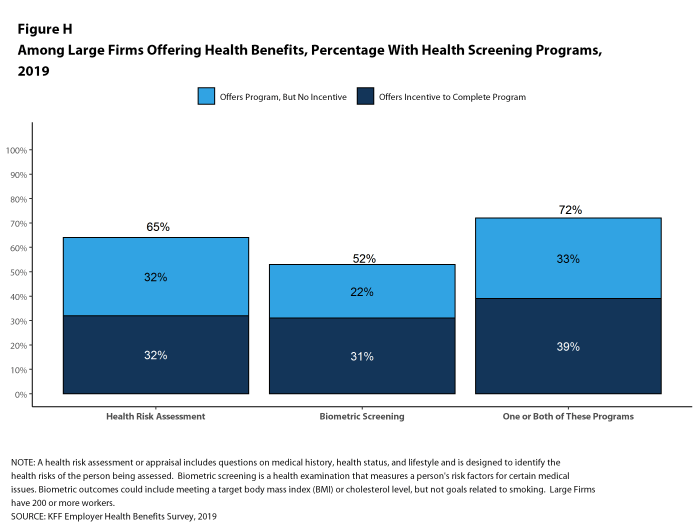

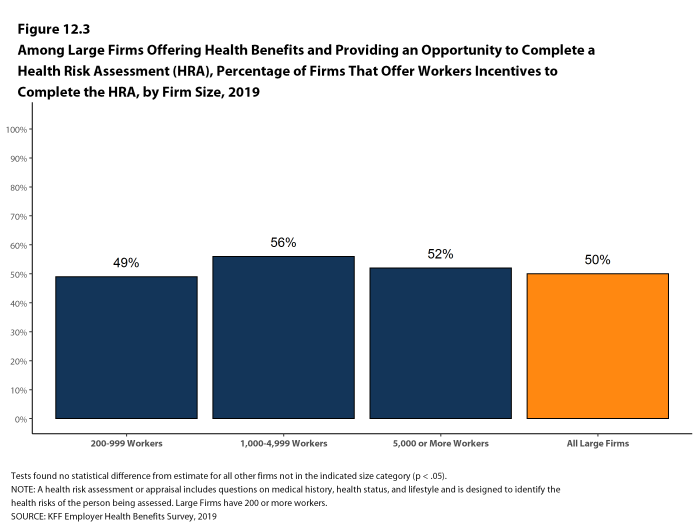

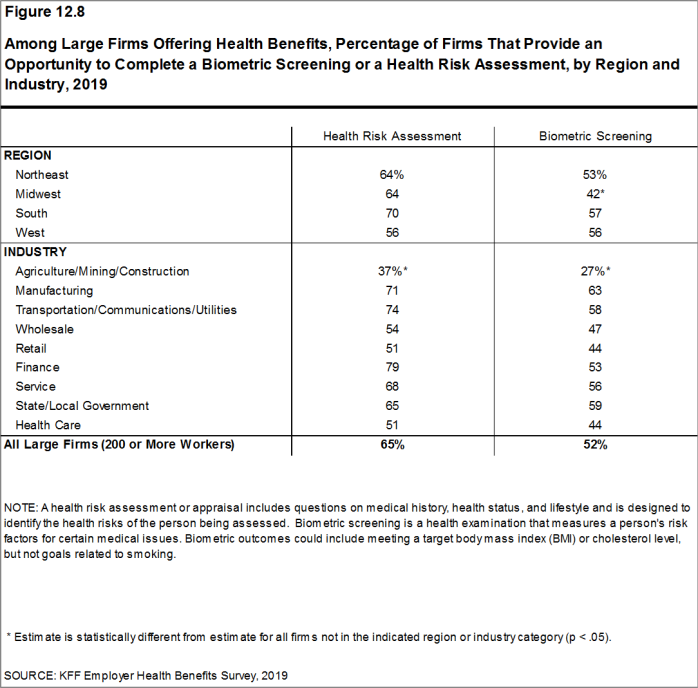

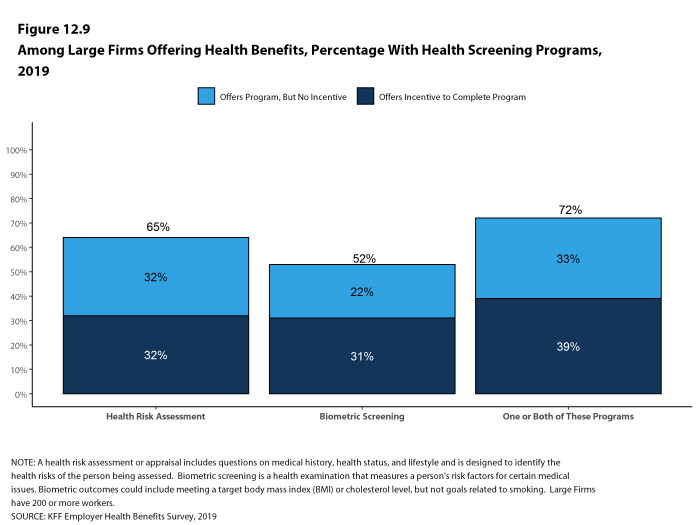

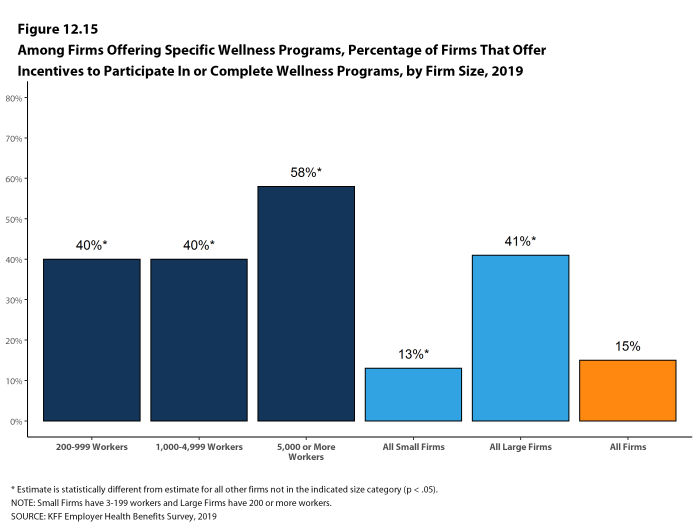

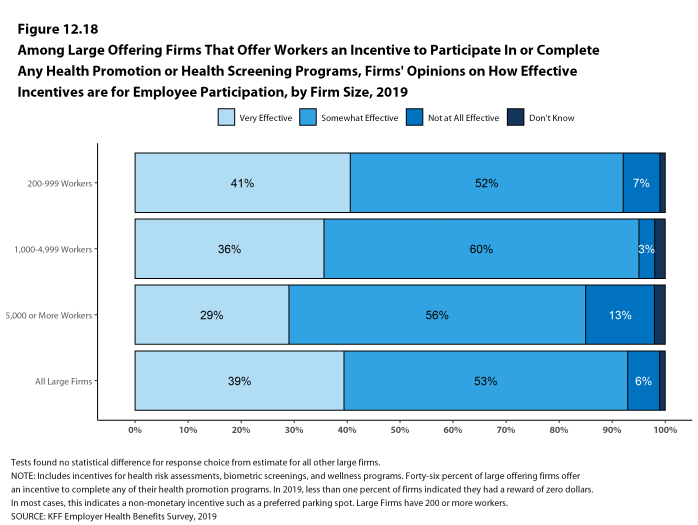

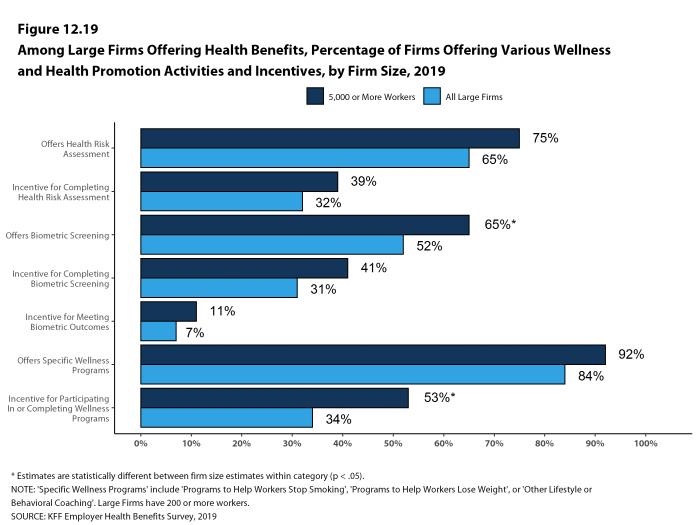

Health Risk Assessments. Among firms offering health benefits, 41% of small firms and 65% of large firms provide workers the opportunity to complete a health risk assessment. A health risk assessment includes questions about a person’s medical history, health status, and lifestyle. Fifty percent of large firms with a health risk assessment program offer an incentive to encourage workers to complete the assessment. Incentives may include: gift cards, merchandise or similar rewards; lower premium contributions or cost sharing; and financial rewards, such as cash, contributions to health-related savings accounts, or avoiding a payroll fee.

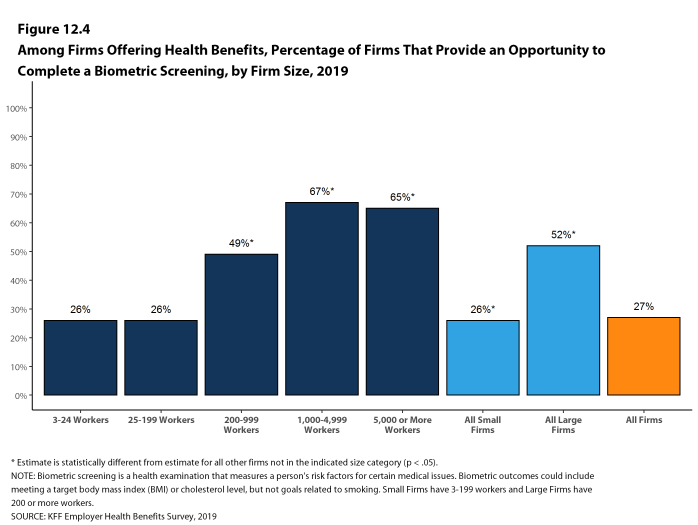

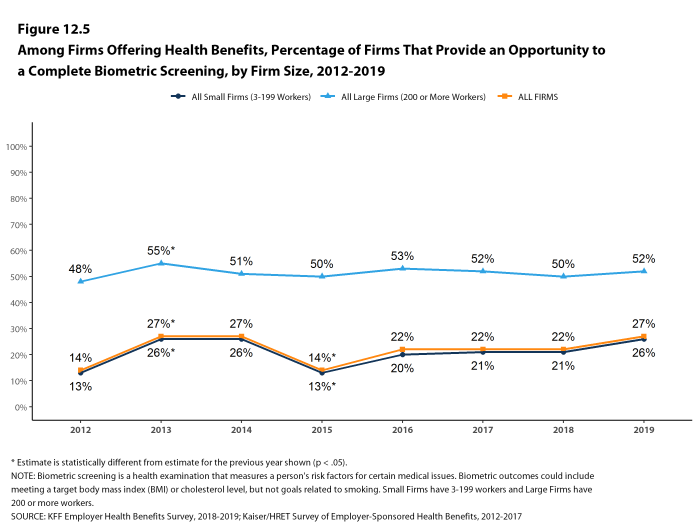

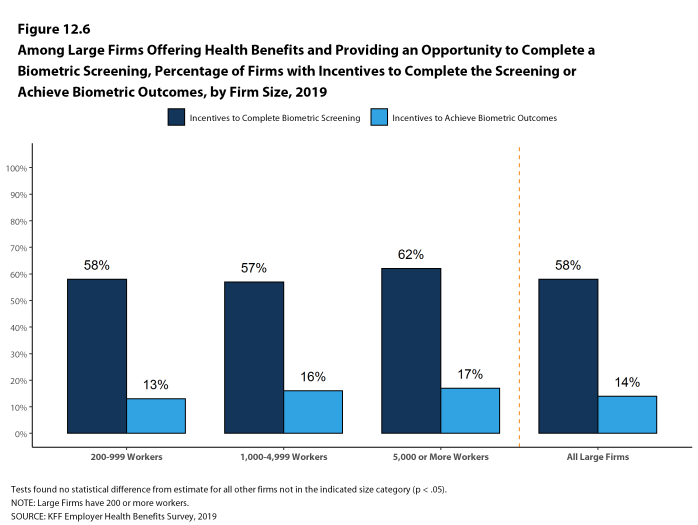

Biometric Screenings. Among firms offering health benefits, 26% of small firms and 52% of large firms provide workers the opportunity to complete a biometric screening. A biometric screening is an in-person health examination that measures a person’s risk factors, such as body mass index (BMI), cholesterol, blood pressure, stress, and nutrition. Fifty-eight percent of large firms with biometric screening programs offer workers an incentive to complete the screening, similar to the incentives for completing health risk assessments.

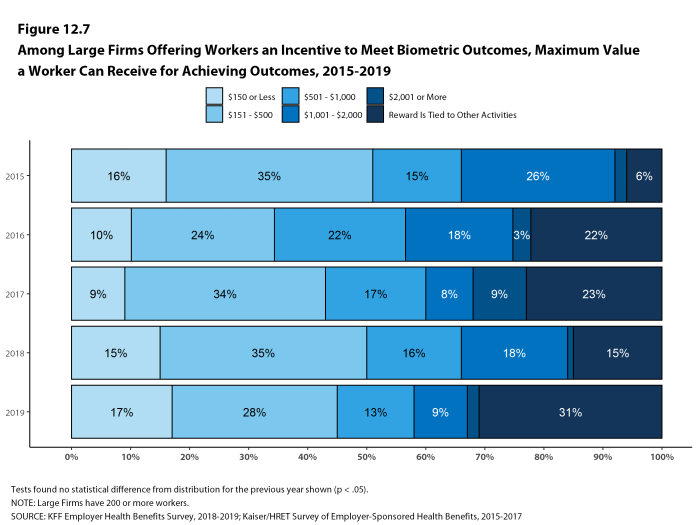

Additionally, among large firms with biometric screening programs, 14% reward or penalize workers based on achieving specified biometric outcomes (such as meeting a target BMI). The size of these incentives varies considerably: among large firms offering a reward or penalty for meeting biometric outcomes, the maximum reward is valued at $150 or less in 17% of firms and more than $1,000 in 11% of firms.

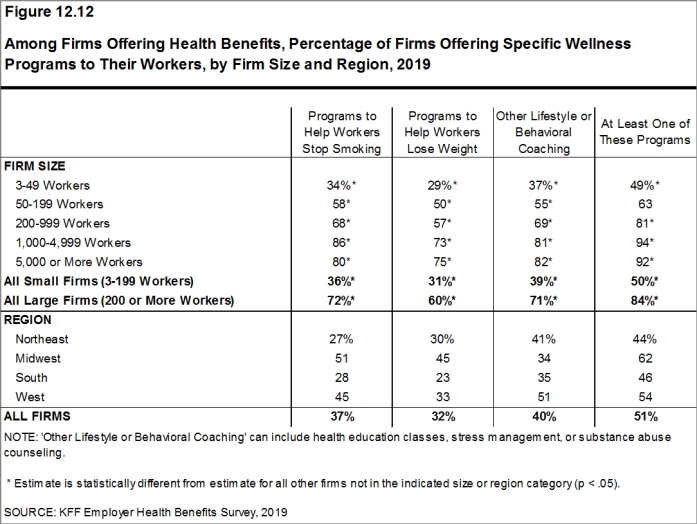

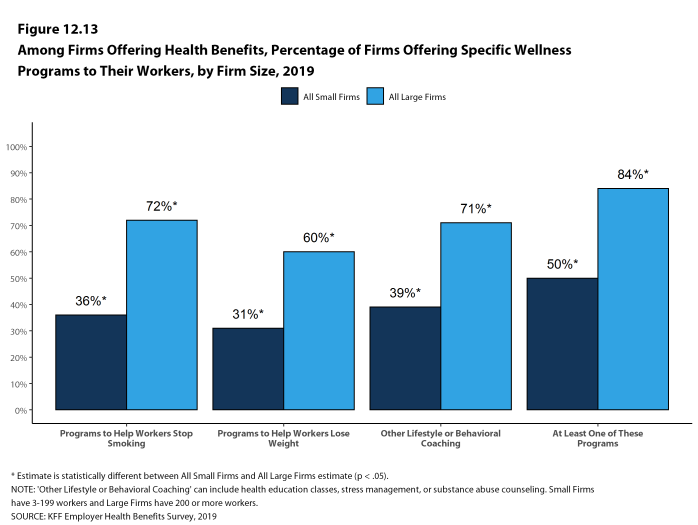

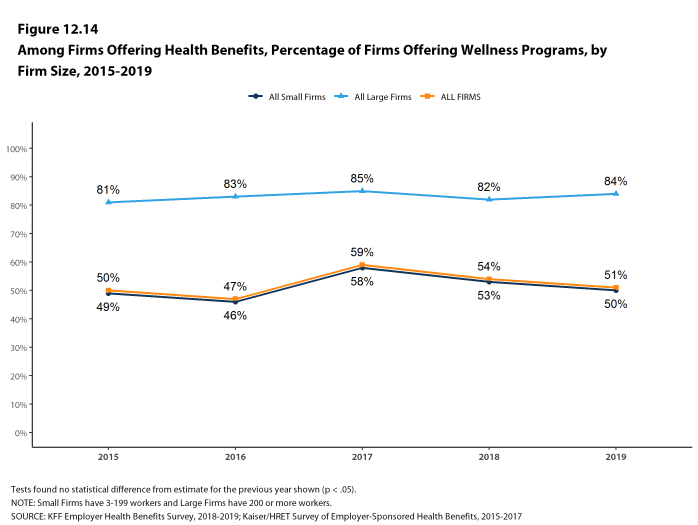

Health and Wellness Promotion Programs. Most firms offering health benefits offer programs to help workers identify and address health risks and unhealthy behaviors. Fifty percent of small firms and 84% of large firms offer a program in at least one of these areas: smoking cessation, weight management, and behavioral or lifestyle coaching. Among large firms offering at least one of these programs, 41% offer workers an incentive to participate in or complete the program.

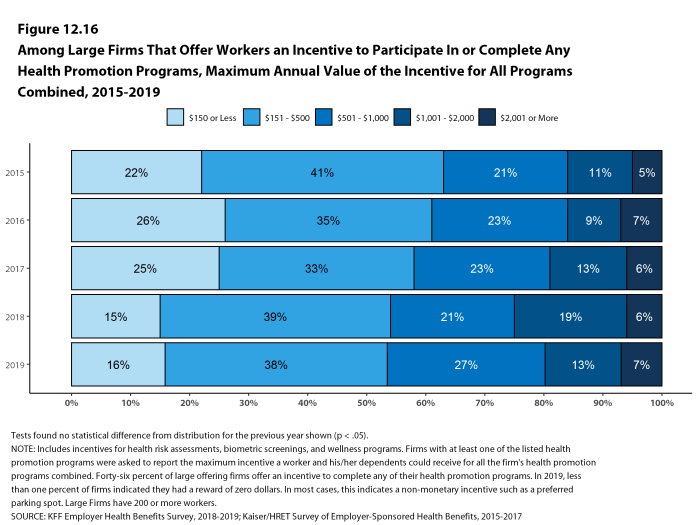

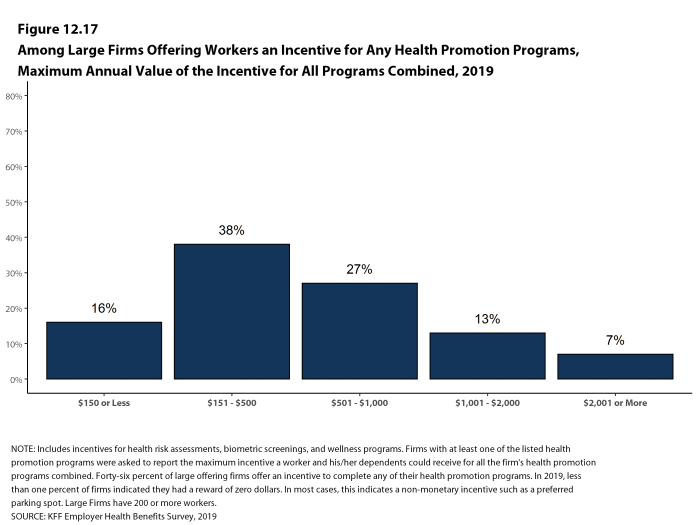

As health screenings and wellness programs have become more complex, incentives have become more sophisticated and may involve participating in or meeting goals in different programs. We asked firms that had incentives for any of these programs to estimate the maximum incentive for a worker across all of their screening and promotion programs combined. Among large firms with any type of incentive, 16% have a maximum incentive of $150 or less, while 20% have a maximum incentive of more than $1,000.

Figure H: Among Large Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage With Health Screening Programs, 2019

SITES OF CARE

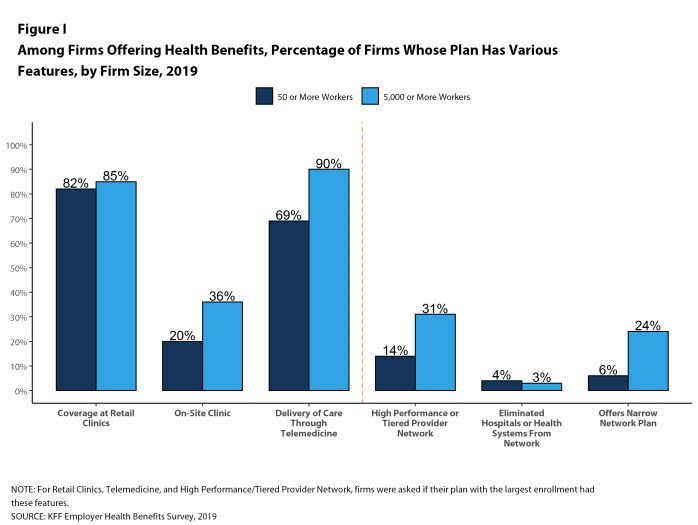

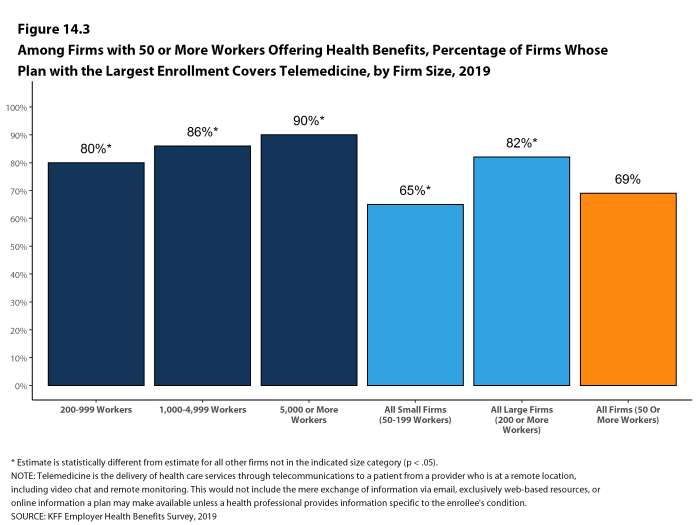

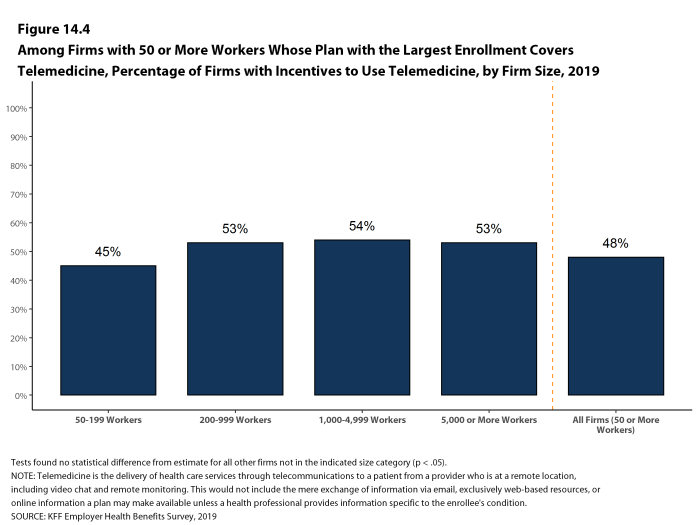

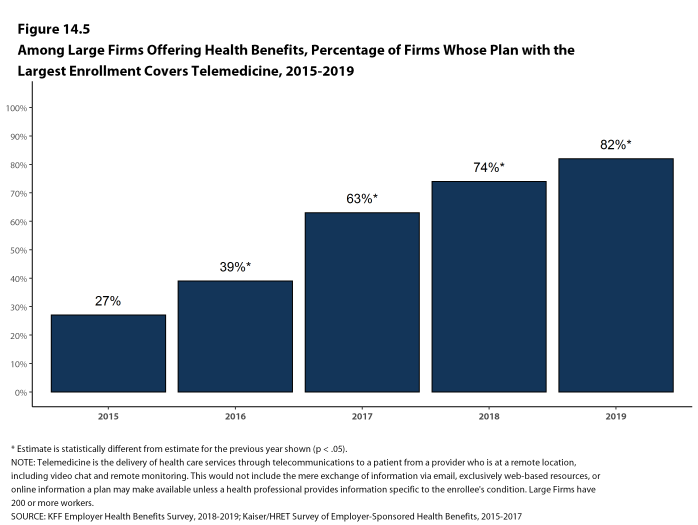

Telemedicine. Sixty-nine percent of firms with 50 or more workers offering health benefits cover the provision of health care services through telemedicine in their largest health plan [Figure I]. Telemedicine is the delivery of health care services through telecommunications to a patient from a provider who is at a remote location, including video chat and remote monitoring. Firms with 5,000 or more workers are more likely to cover services provided through telemedicine than smaller firms.

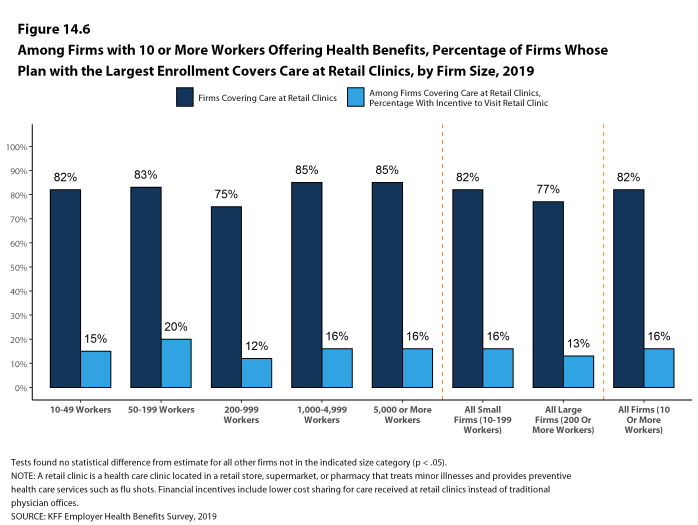

Retail Health Clinics. Seventy-seven percent of large firms offering health benefits cover health care services received in retail clinics, such as those located in pharmacies, supermarkets and retail stores, in their largest health plan [Figure I]. These clinics are often staffed by nurse practitioners or physician assistants and treat minor illnesses and provide preventive services.

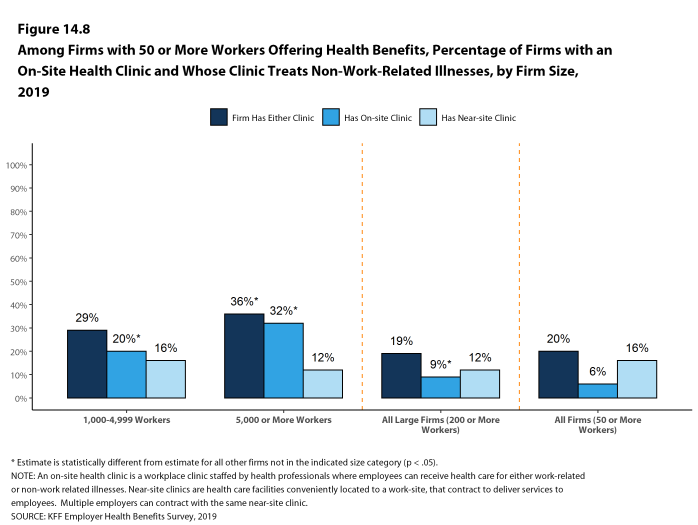

On-Site and Near-Site Health Clinics 19% of large firms offering health benefits, including 36% of firms with 5,000 or more employees, have a health clinic for their employees at or near one or more of their major locations. A large share of these firms report that employees can receive treatment for non-work-related illnesses at their on-site clinics.

PROVIDER NETWORKS

Firms and health plans can structure their networks of providers and their cost sharing to encourage enrollees to use providers who are lower cost or who provide better care. Periodically we ask employers about network strategies, such as using tiered or narrow networks. For 2019, as part of our partnership with the Peterson Center on Healthcare, we added questions about additional network strategies and about employer satisfaction with the options available to them.

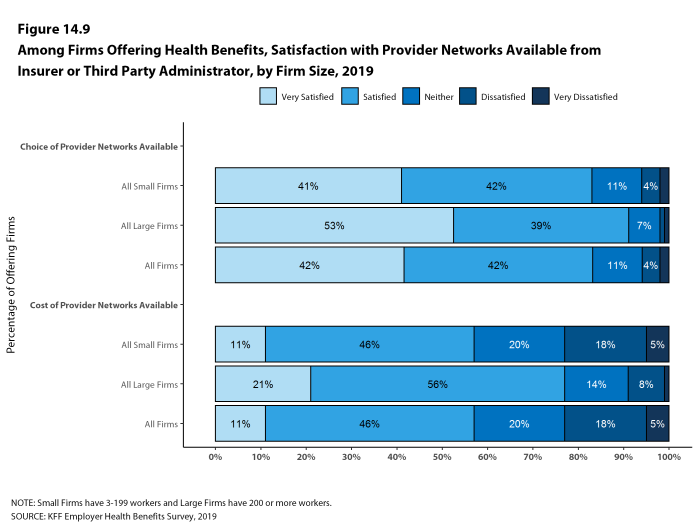

Satisfaction with Network Choices Among employers offering health benefits, 42% of firms report being ‘very satisfied’ and 42% report being ‘satisfied’ by the choice of provider networks available to them. They are somewhat less satisfied with the cost of the provider networks available to them, however. Only 11% of these firms report being ‘very satisfied’ while 46% report being ‘satisfied’ with the cost of provider networks available to them. Large firms are more likely than small firms to be very satisfied with the cost of available provider networks, while small firms are more likely to be ‘dissatisfied’ or ‘very dissatisfied’ with the cost of the provider networks available to them.

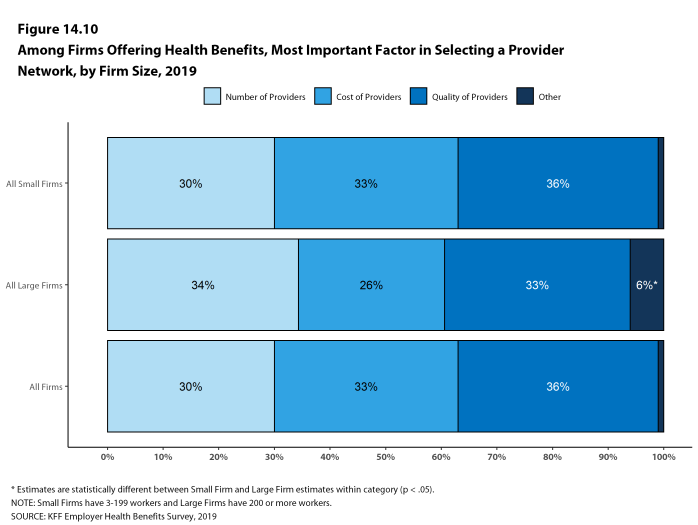

When asked to identify the most important factor they use to assess provider networks, employers are fairly evenly divided, with 30% of employers identifying the number and convenience of providers as most important, 33% identifying the cost of providers as most important, and 36% identifying the quality of providers as most important.

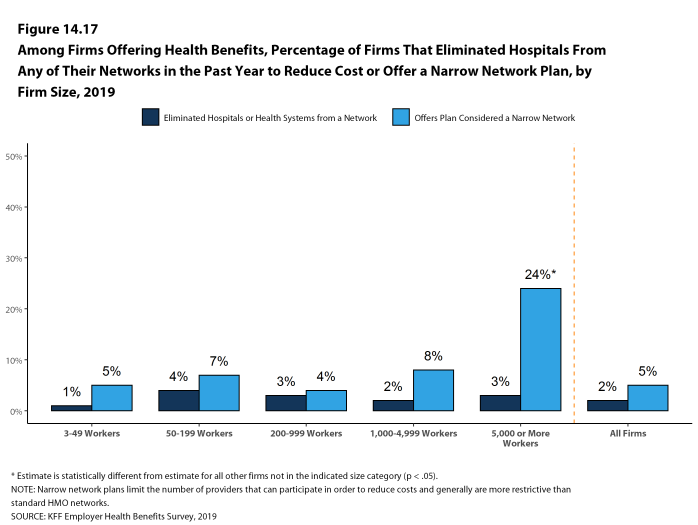

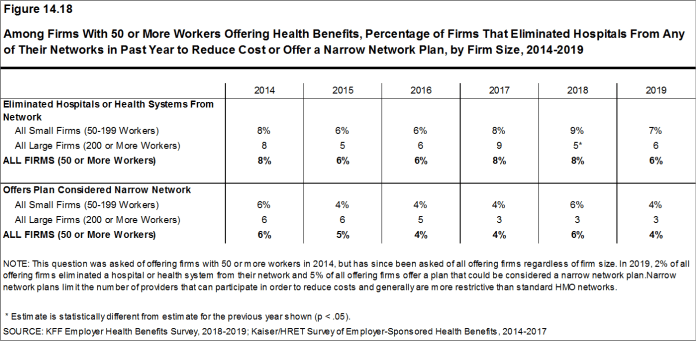

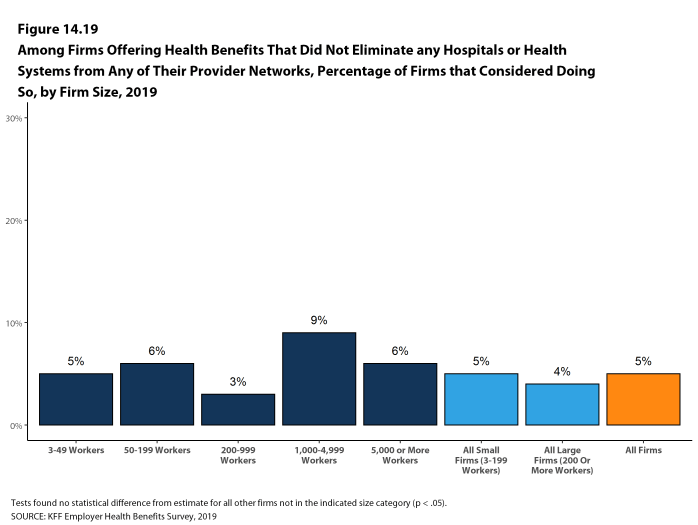

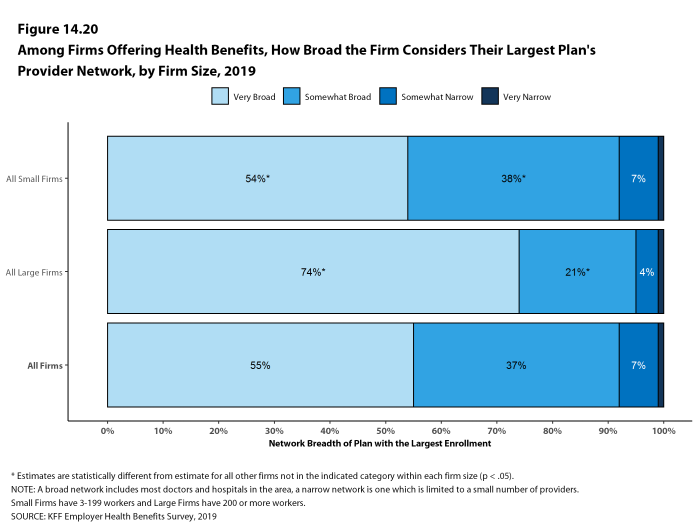

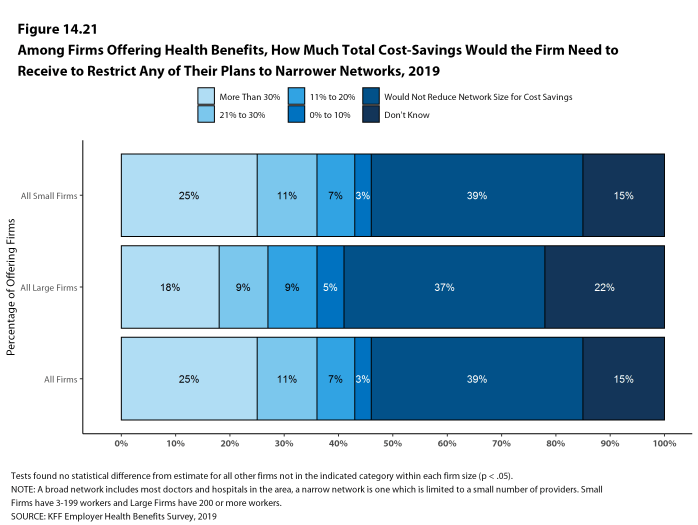

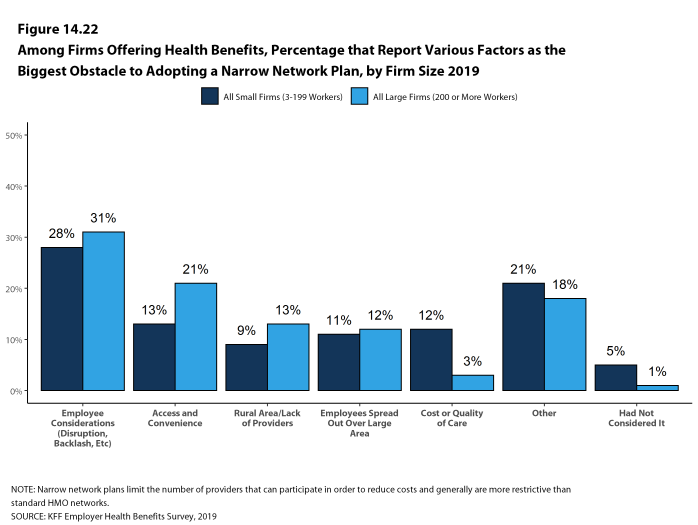

Narrow Networks Among employers offering health benefits, 55% say that the network for their plan with the largest enrollment is ‘very broad’, 37% say it is ‘somewhat broad’, and 7% say it is ‘somewhat narrow’. When asked how much cost savings the firm would need to realize to shift any of their health plans to narrower networks, a significant share of employers (39%) say that they would not reduce network size for cost savings, 25% say that they would need to realize savings of more than 30%, and 11% say that they would need to realize savings of between 20% and 30%. When employers were asked to identify the biggest obstacle adopting a narrower network plan or plans, 28% cite employee considerations, such as disruption of provider relationships or employee backlash, 14% cite concerns about access or convenience for employees, 9% say that they are in a rural area and/or there was a lack of providers, 11% say that their employees are spread out over a large area, and 12% cite concerns about the cost or quality of care.

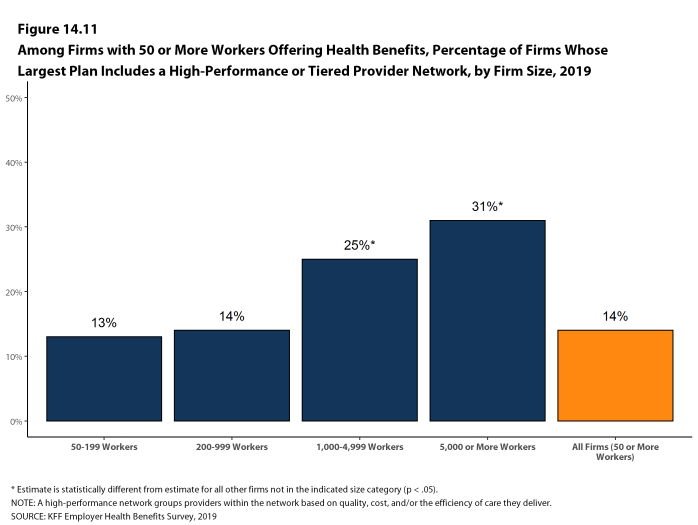

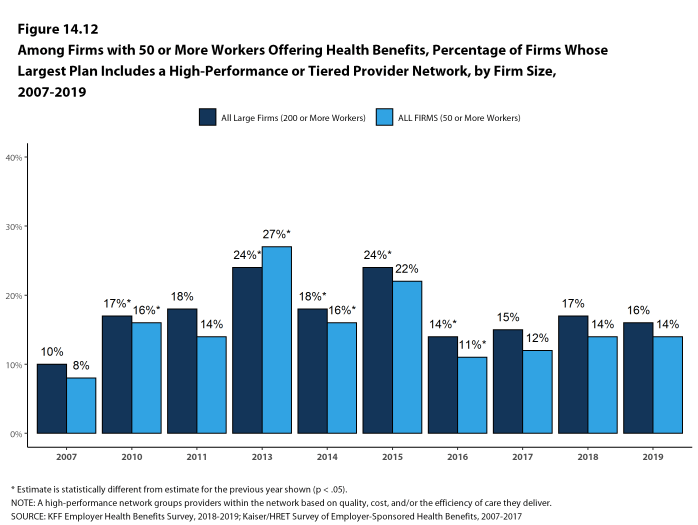

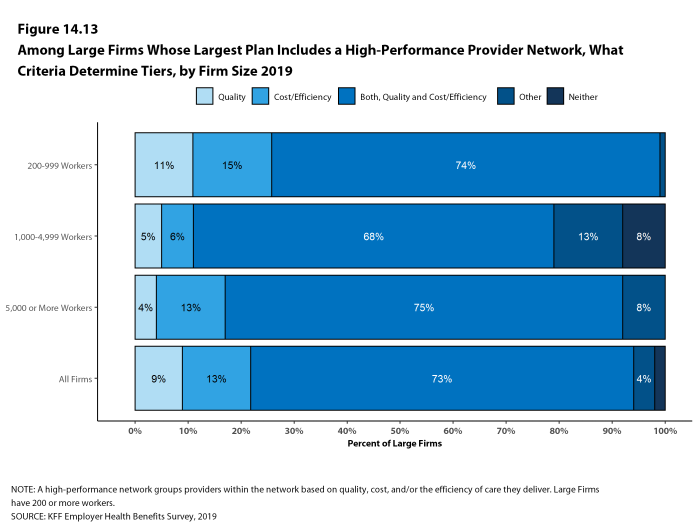

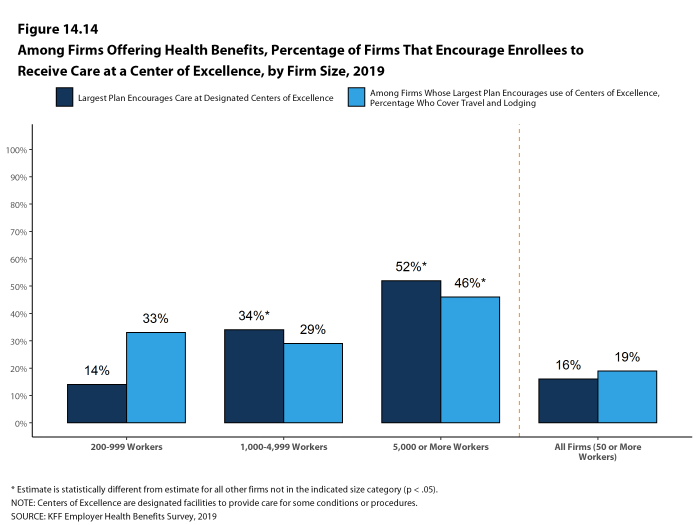

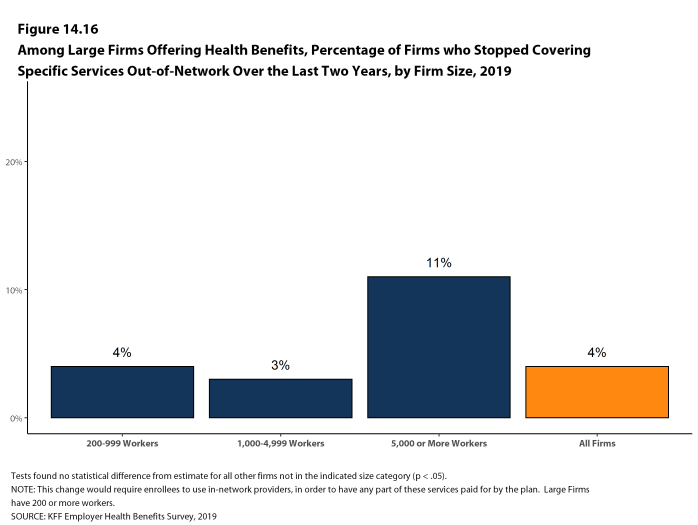

Tiered or High-Performance Networks Fourteen percent of firms with 50 or more workers that offer health benefits include a high-performance or tiered provider network in their health plan with the largest enrollment, similar to the percentage last year. A tiered or high-performance network typically groups providers in the network based on the cost, quality and/or efficiency of the care they deliver and uses financial incentives to encourage enrollees to use providers on the preferred tier.

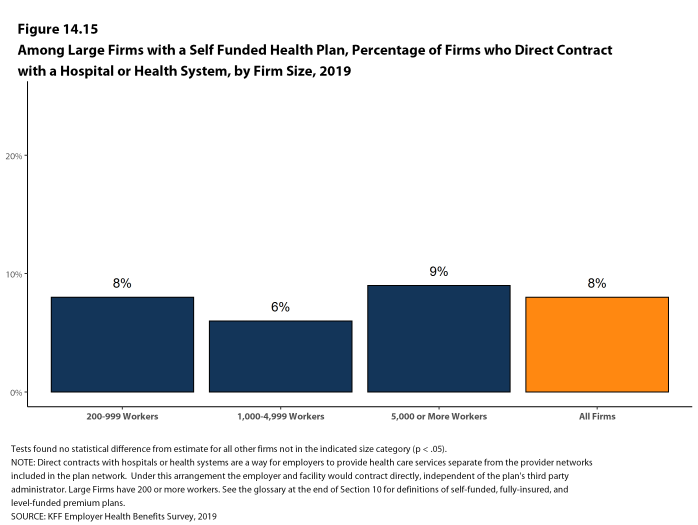

Direct Contracting Some employers also contract directly with certain health plans or health systems, outside of their established provider networks, to treat patients with specified conditions. Among large employers with at least one self-funded health plan, 8% have such an arrangement.

Figure I: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms Whose Plan Has Various Features, by Firm Size, 2019

EXCISE TAX ON HIGH COST HEALTH PLANS

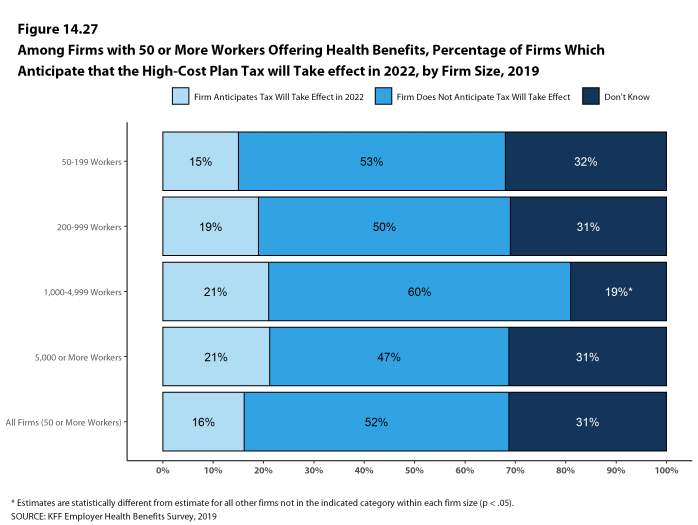

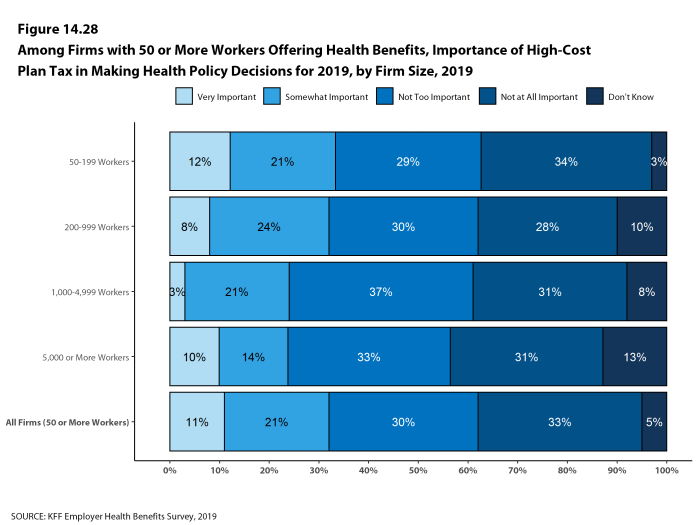

The high-cost plan tax, sometimes called the “Cadillac Tax”, is an excise tax on health benefit plans with premiums and other costs that exceed specified thresholds. The tax was scheduled to take effect in 2018, but its effective date has been delayed several times, and recently a bill passed the House that would repeal the provision entirely.4 Only 16% of firms offering health benefits with 50 or more employees say they expect the high-cost plan tax to take effect as scheduled, 52% say it will not take effect as scheduled, and 31% say they do not know. Thirty-three percent of offering firms say that the upcoming high-cost plan tax was ‘very important’ or ‘somewhat important’ when making health benefit decisions for 2019, while 62% say that was ‘not too important’ or ‘not important at all.’ A recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis finds that at least one in five employers would be affected by the tax if it takes effect in 2022 unless they make changes to lower plan costs.5

PRESCRIPTION DRUG PRACTICE

The cost of prescription drugs is one of the largest challenges facing employers and families. Recent policy options have focused on the complexity involving the delivery and pricing of prescription drugs and the lack of transparency about the true price for individual prescriptions. In particular, policy makers have focused on rebate payments from pharmaceutical manufacturers to payers and intermediaries as obscuring true costs. Payers have also raised questions about discount coupons and other patient assistance that manufacturers provide to patients which reduce patient cost sharing and mute financial incentives in payer formularies to encourage patients to use lower-priced alternatives.

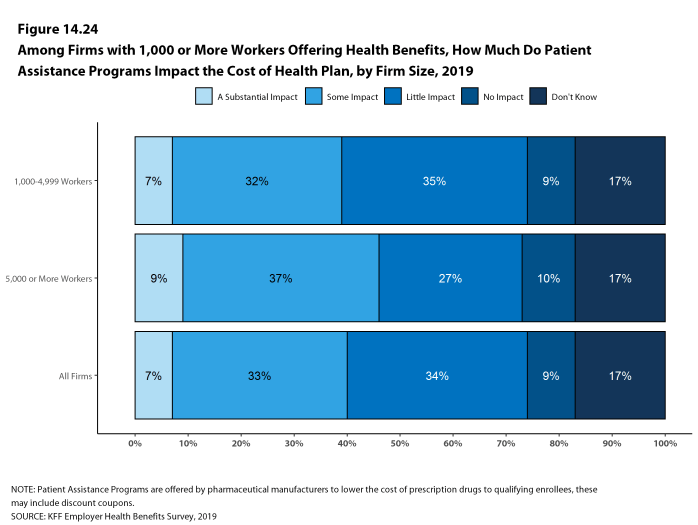

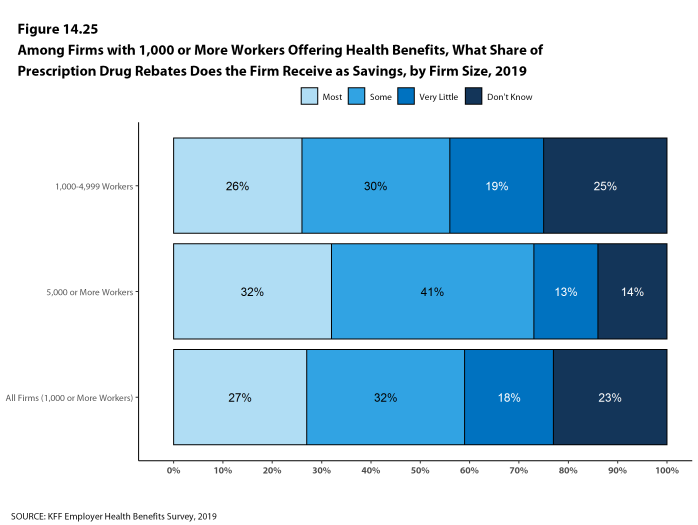

Among employers offering health benefits with 1,000 or more employees, 27% say that they receive ‘most’ of the prescription drug rebate negotiated by their PBM or health plan, 32% say that they receive ‘some’ of the negotiated rebate, 18% say that they receive ‘very little’ of the negotiated rebate, and 23% do not know. When asked about discount coupons and patient assistance programs, only 7% say they believe that they have a ‘substantial impact’ on the cost of their health plans, 33% say that have ‘some impact’ on plan costs, 34% say that they have ‘little impact’ on plan costs, 9% say that they have ‘no impact’ on plans costs, while 17% do not know.

DISCUSSION

Trends in the market for employer-based coverage have been moderate for several years now. Premiums go up each year, but in the low to mid-single digits, which seems tame for those who remember the much higher increases in the early 2000’s and periods before. Cost sharing, particularly deductibles, has increased meaningfully over time, but the largest percentage increases were now a few years ago. New ideas and new approaches – things like narrow networks, value-based pricing, telemedicine, direct contracting – are tried and sometimes gradually implemented, but with modest impact on the basic structure of the market or the overall cost of coverage. Even though actual cost levels are quite high (the average family premium exceeds $20,000 for a family of four), an expanding economy and historically low underlying health care cost growth appear to have dampened any impatience for big changes, although predicted economic slowing over the next couple of years could push employers to consider more significant actions.

One thing that is new this year is the context: the public debate over expanding Medicare or creating public program options is raising questions about the performance of employer-based coverage that are rarely triggered when looking only at annual performance. In particular, those suggesting a bigger role for public programs raise issues about the cost and affordability of health care for the society overall and for individuals and families. Although premium growth has been low, it still exceeds inflation, and the prices employer plans pay for care are rising faster than either Medicare or Medicaid. One side of the coin calls this a cost shift from public plans to private payers; the other side suggests a lack of any real cost-control efforts in private plans. Negotiating lower prices means that plans have to be willing to tell higher-priced providers they cannot be in the network, but as the survey findings show, narrowing networks is both unpopular with employers and, due to dispersed workforces and rural challenges, impractical for many. Other than increasing cost-sharing, this is the most (and maybe only) powerful cost-reducing tool that private plans have, but it is rarely employed.

How to best assure affordable access to care for individuals and families is really the main theme in the debate about public plan options, and our polling suggests this issue raises important questions about the adequacy of employer-based plans. In a recent survey conducted by KFF and the LA Times, 40 percent of non-elderly adults with employer-based coverage said that they or a family member had difficulty affording health insurance or health care or had problems paying medical bills.6 Roughly one-in-two said that they or a family member had skipped or postponed getting health care or prescriptions in the past 12 months due to costs. Among those with employer-based coverage who say that someone under the plan has a chronic health condition, roughly three in five say they are confident that they have enough money or health insurance to afford the cost of a major illness; this percentage falls to just one-in-three for those in plans with the highest deductibles ($3,000 for single coverage; $5,000 or more for family coverage).

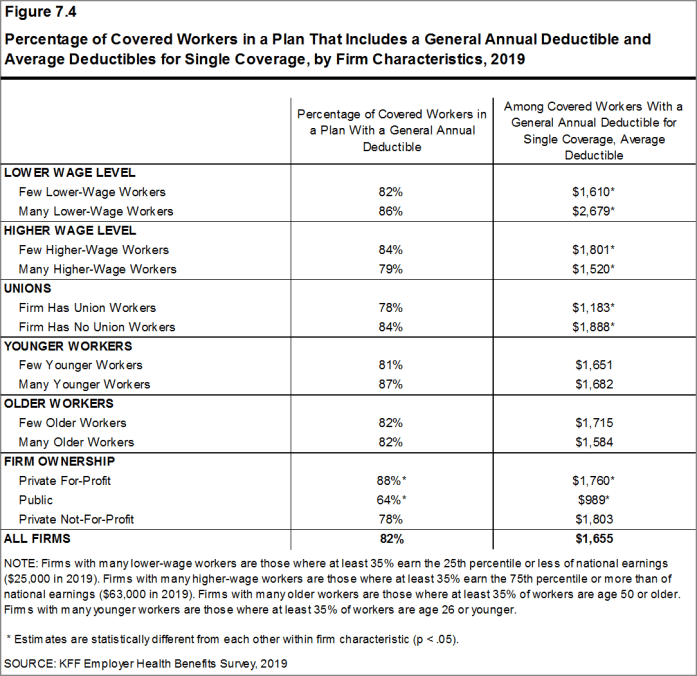

This survey shows other affordability issues as well, particularly for some identifiable groups. Covered workers in small firms face relatively high deductibles for single coverage and a meaningful share face substantial premium contributions if they choose family coverage. Covered workers in firms with large shares of lower-wage workers on average face higher deductibles for single coverage and must contribute a greater share of the premium for family coverage than workers in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers. When people talk about the 153 million people with employer-based coverage they often gloss over the very real cost differences for different groups of workers across the marketplace.

Regardless of its outcome, the national debate about expanding Medicare or creating public program options provides an opportunity to step back and evaluate how well employer-based coverage is doing in achieving national goals relating to costs and affordability. In doing so, it will be important to look past averages and examine how well the market serves the many different types of employers and working families in the many different circumstances that they face.

METHODOLOGY

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey reports findings from a telephone survey of 2,012 randomly selected non-federal public and private employers with three or more workers. Researchers at NORC at the University of Chicago and the Kaiser Family Foundation designed and analyzed the survey. National Research, LLC conducted the fieldwork between January and July 2019. In 2019, the overall response rate is 27%, which includes firms that offer and do not offer health benefits. Among firms that offer health benefits, the survey’s response rate is 26%. To improve estimates for small firms, the 2018 survey had a significantly larger sample than in previous years; the increased sample size led to both more firms completing the survey and a lower response rate than in years past. Unless otherwise noted, differences referred to in the text and figures use the 0.05 confidence level as the threshold for significance. Values below 3% are not shown on graphical figures to improve the readability of those graphs. Some distributions may not sum due to rounding. In 2019, we modified our weighting methodology by no longer using a non-response adjustment; this change had the largest impact on the offer rate but had a negligible effect on most statistics.

For more information on the survey methodology, please visit the Survey Design and Methods section at http://ehbs.kff.org/.

Filling the need for trusted information on national health issues, the Kaiser Family Foundation is a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco, California.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer: Supplemental Tables. 2019 Jan (cited 2019 Aug 16). https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/. See Table 1: 267.5 million nonelderly people, 57.1% of whom are covered by employer-sponsored insurance.↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers (April to April – not seasonally adjusted): Department of Labor; 2019. https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0. Wage data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and based on the change in total average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees. Employment, hours, and earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey: Department of Labor; 2019. https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES0500000008↩

- This threshold is based on the twenty-fifth percentile of workers’ earnings. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2018 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates: United States. Washington (DC): BLS. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm↩

- Middle Class Health Benefits Tax Repeal Act, H.R. 748, 116th Cong. (2019)↩

- Rae, Matthew; Claxton, Gary; Levitt, Larry. “How Many Employers Could Be Affected by the High-Cost Plan Tax” Kaiser Family Foundation. July 12, 2019. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/how-many-employers-could-be-affected-by-the-high-cost-plan-tax/↩

- Hamel, Liz; Munana, Cailey and Brodie, Mollyann. “Kaiser Family Foundation/LA Times Survey Of Adults With Employer-Sponsored Insurance.” Kaiser Family Foundation. May 2, 2019. https://www.kff.org/report-section/kaiser-family-foundation-la-times-survey-of-adults-with-employer-sponsored-insurance-section-2-affordability-of-health-care-and-insurance/↩

Survey Design And Methods

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) has conducted this annual survey of employer-sponsored health benefits since 1999. KFF works with NORC at the University of Chicago (NORC) and National Research, LLC (NR) to field and analyze the survey. From January to July 2019, NR completed computer-assisted telephone interviews with human resource and benefits managers at 2,012 firms.

SURVEY TOPICS

The survey includes questions on the cost of health insurance, health benefit offer rates, coverage, eligibility, plan type enrollment, premium contributions, employee cost sharing, prescription drug benefits, retiree health benefits, and wellness benefits.

Firms that offer health benefits are asked about the plan attributes of their largest health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point-of-service (POS) plan, and high-deductible health plan with a savings option (HDHP/SO).7 We treat exclusive provider organizations (EPOs) and HMOs as one plan type and conventional (or indemnity) plans as PPOs. The survey defines an HMO as a plan that does not cover nonemergency out-of-network services. PPOs and POS plans have lower cost sharing for in-network services than HMOs do. POS plans use a primary care gatekeeper to screen for specialist and hospital visits. HDHP/SOs were defined as plans with a deductible of at least $1,000 for single coverage and $2,000 for family coverage and that either offer a health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) or are eligible for a health savings account (HSA).

Throughout this report, we use the term “in-network” to refer to services received from a preferred provider. Definitions of the health plan types are available in Section 4, and a detailed explanation of the HDHP/SO plan type is in Section 8.

To reduce survey burden, some questions on worker cost sharing for hospitalization, outpatient surgery and prescription drugs were only asked about the firm’s largest plan type

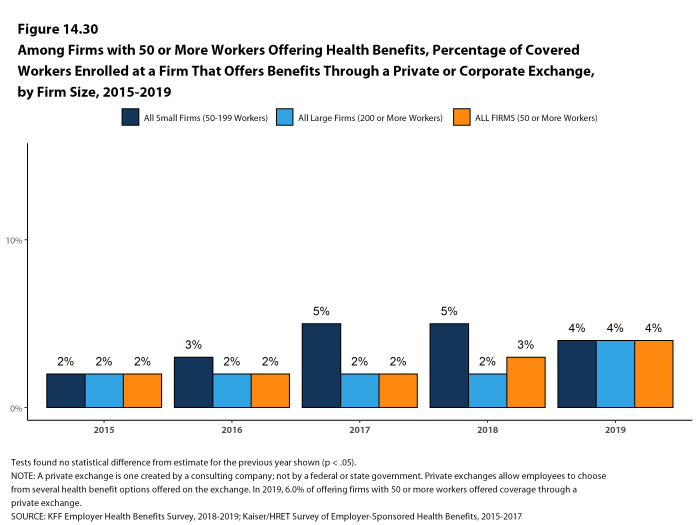

Firms with 50 or more workers were asked: “Does your firm offer health benefits for current employees through a private or corporate exchange?” Employers were still asked for plan information about their HMO, PPO, POS and HDHP/SO plan regardless of whether they purchased health benefits through a private exchange or not.

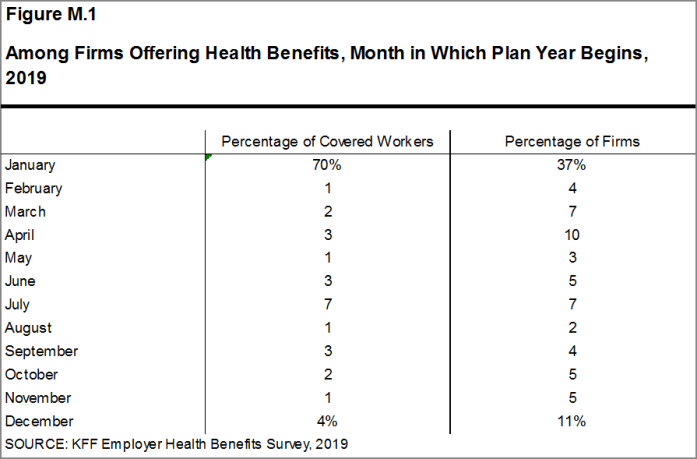

Firms are asked about the attributes of their current plans during the interview. While the survey’s fielding period begins in January, many respondents may have a plan whose 2019 plan year lags behind the calendar year [Figure M.1]. In some cases, plans may report the attributes of their 2018 plans and some plan attributes (such as HSA deductible limits) may not meet the calendar year regulatory requirements.

Figure M.1: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Month in Which Plan Year Begins, 2019

SAMPLE DESIGN

The sample for the annual Kaiser Employer Health Benefits Survey includes private firms and nonfederal government employers with three or more employees. The universe is defined by the U.S. Census’ 2015 Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) for private firms and the 2012 Census of Governments (COG) for non-federal public employers. At the time of the sample design (December 2018), these data represented the most current information on the number of public and private firms nationwide with three or more workers. As in the past, the post-stratification is based on the most up-to-date Census data available (the 2016 SUSB). We determine the sample size based on the number of firms needed to ensure a target number of completes in six size categories.

We attempted to repeat interviews with prior years’ survey respondents (with at least ten employees) who participated in either the 2017 or the 2018 survey, or both. Firms with 3-9 employees are not included in the panel to minimize the potential of panel effects. As a result, 1,445 of the 2,012 firms that completed the full survey also participated in either the 2017 or 2018 surveys, or both. In total, 329 firms participated in 2017, 157 firms participated in 2018, and 959 firms participated in both 2017 and 2018. Non-panel firms are randomly selected within size and industry groups.

Since 2010, the sample has been drawn from a Dynata list (based on census assembled by Dun and Bradstreet) of the nation’s private employers and the COG for public employers. To increase precision, we stratified the sample by ten industry categories and six size categories. The federal government and business with fewer than three employees are not included. Education is a separate category for the purposes of sampling, and included in Service category for weighting. For information on changes to the sampling methods over time, please consult the Survey Design and Methods Sections of prior Employer Health Benefits Surveys as well as extended methods at http://ehbs.kff.org/

Each year, we conduct a series of checks on our instrument to confirm the accuracy of data collection, including test interviews prior to the official launch. Beginning in 2019, we included firms with at least ten employees that had completed a pre-test during the prior year’s survey in the current year’s sample. Firms eligible to complete pre-testing had been sampled from the same two universe datasets as the main non-panel sample, differing only by when they made contact with the interview team. We expect to continue including these firms completing an interview during the pre-testing phase of our survey, and believe they will improve our response rate without adding any bias to our data collection effort.

RESPONSE RATE

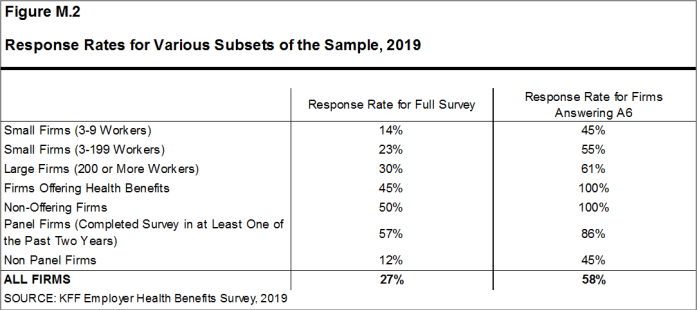

Response rates are calculated using a CASRO method, which accounts for firms that are determined to be ineligible in its calculation. The overall response rate is 27% [Figure M.2].8 The response rate for panel firms is higher than the response rate for non-panel firms [Figure M.2]. Similar to other employer and household surveys, the Employer Health Benefits Survey has seen a general decrease in response rates over time. Since 2017, we have attempted to increase the number of completes by increasing the number of non-panel firms in the sample. While this generally increases the precision of estimates by ensuring a sufficient number of respondents in various sub-groups, it has the effect of reducing the overall response rate.

The vast majority of questions are asked only of firms that offer health benefits. A total of 1,668 of the 2,012 responding firms indicated they offered health benefits. The response rate for firms that offer health benefits is also 26%.

We asked one question of all firms in the study with which we made phone contact but where the firm declined to participate: “Does your company offer a health insurance program as a benefit to any of your employees?”. A total of 4,395 firms responded to this question (including 2,012 who responded to the full survey and 2,383 who responded to this one question). These responses are included in our estimates of the percentage of firms offering health benefits.9 The response rate for this question is 58% [Figure M.2].

Figure M.2: Response Rates for Various Subsets of the Sample, 2019

While response rates have decreased, elements of the survey design limit the potential impact of a response bias. First, most major statistics are weighted by the percentage of covered workers at a firm. The percentage of the population whose employers completed the full survey has not decreased with response rates. The most important statistic that is weighted by the number of employers is the offer rate; firms that do not complete the full survey are asked whether their firm offers health benefits to any employees. As noted this question relies on a wider set of respondents than just those completing the full survey.

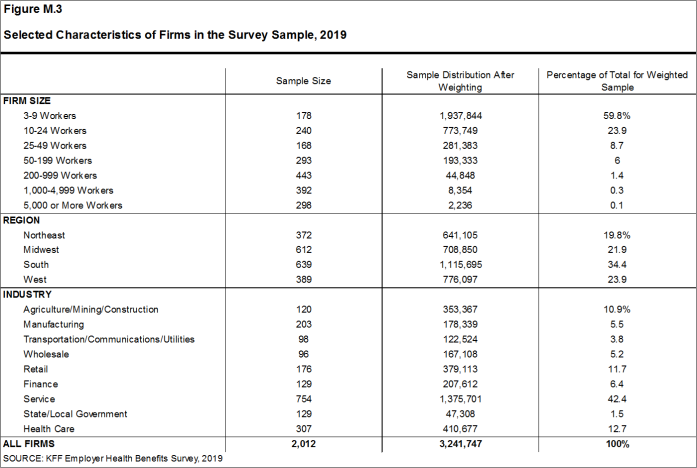

FIRM SIZES AND KEY DEFINITIONS

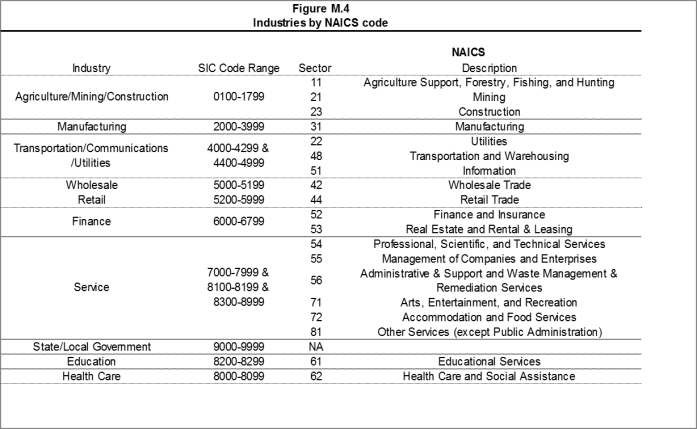

Throughout the report, we report data by size of firm, region, and industry. Unless otherwise specified, firm size definitions are as follows: small firms: 3-199 workers; and large firms: 200 or more workers. [Figure M.3] shows selected characteristics of the survey sample. A firm’s primary industry classification is determined from Dynata’s designation on the sampling frame and is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), [Figure M.4]. A firm’s ownership category and other firm characteristics such as the firm’s wage level and the age of the work force are based on respondents’ answers. While there is considerable overlap in firms in the “State/Local Government” industry category and those in the “public” ownership category, they are not identical. For example, public school districts are included in the service industry even though they are publicly owned. Family coverage is defined as health coverage for a family of four.

Figure M.3: Selected Characteristics of Firms in the Survey Sample, 2019

Figure M.4: Industries by NAICS code

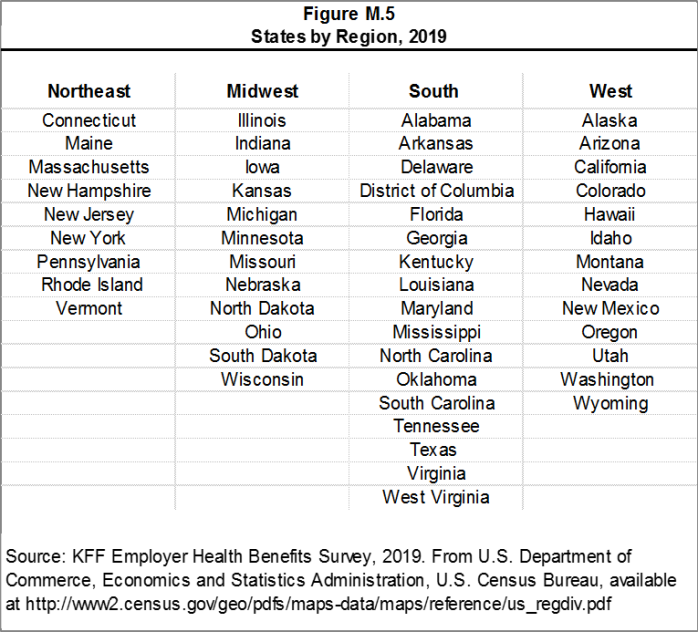

[Figure M.5] presents the breakdown of states into regions and is based on the U.S Census Bureau’s categorizations. State-level data are not reported both because the sample size is insufficient in many states and we only collect information on a firm’s primary location rather than where all workers may actually be employed. Some mid- and large-size employers have employees in more than one state, so the location of the headquarters may not match the location of the plan for which we collected premium information.

Figure M.5: States by Region, 2019

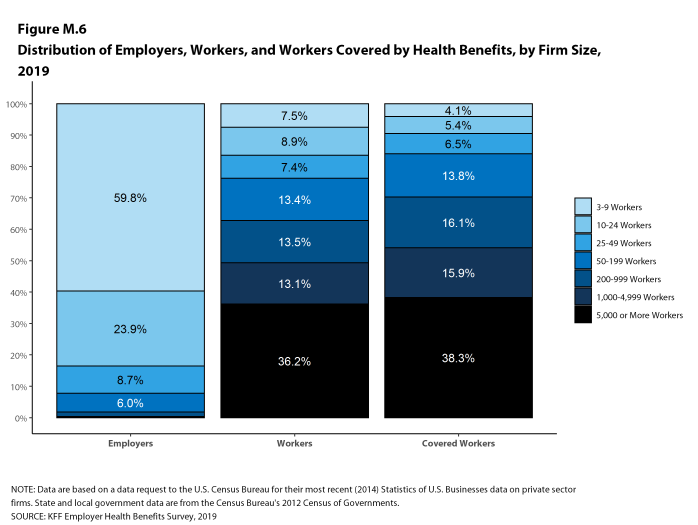

[Figure M.6] displays the distribution of the nation’s firms, workers, and covered workers (employees receiving coverage from their employer). Among the three million firms nationally, approximately 59.8% employ 3 to 9 workers; such firms employ 7.5% of workers, and 4.1% of workers covered by health insurance. In contrast, less than one percent of firms employ 5,000 or more workers; these firms employ 36.2% of workers and 38.3% of covered workers. Therefore, the smallest firms dominate any statistics weighted by the number of employers. For this reason, most statistics about firms are broken out by size categories. In contrast, firms with 1,000 or more workers are the most influential employer group in calculating statistics regarding covered workers, since they employ the largest percentage of the nation’s workforce. Statistics among small firms and those weighted by the number of firms tend to have more variability.

Figure M.6: Distribution of Employers, Workers, and Workers Covered by Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 2019

The survey asks firms what percentage of their employees earn more or less than a specified amount in order to identify the portion of a firm’s workforce that has relatively lower or higher wages. This year, the income threshold is $25,000 or less per year for lower-wage workers and $63,000 or more for higher-wage workers. These thresholds are based on the 25th and 75th percentile of workers’ earnings as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics using data from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) (2018).10 The cutoffs were inflation-adjusted and rounded to the nearest thousand.

ROUNDING AND IMPUTATION

Some figures in the report do not sum to totals due to rounding. Although overall totals and totals for size and industry are statistically valid, some breakdowns may not be available due to limited sample sizes or high relative standard errors. Where the unweighted sample size is fewer than 30 observations, figures include the notation “NSD” (Not Sufficient Data). Estimates with high relative standard errors are reviewed and in some cases not published. Many breakouts by subsets may have a large standard error, meaning that even large differences between estimates are not statistically different. Values below 3% are not shown on graphical figures to improve the readability of those graphs. The underlying data for all estimates presented in graphs are available in the Excel documents accompanying each section on http://www.kff.org/ehbs.

To control for item nonresponse bias, we impute values that are missing for most variables in the survey. On average, 5% of observations are imputed. All variables are imputed following a hotdeck approach. The hotdeck approach replaces missing information with observed values from a firm similar in size and industry to the firm for which data are missing. In 2019, there were seven variables where the imputation rate exceeded 20%; most of these cases were for individual plan level statistics. When aggregate variables were constructed for all of the plans, the imputation rate is usually much lower. There are a few variables that we have decided not to impute; these are typically variables where “don’t know” is considered a valid response option. Some variables are imputed based on their relationship to each other. For example, if a firm provided a worker contribution for family coverage but no premium information, a ratio between the family premium and family contribution was imputed and then the family premium was calculated. We estimate separate single and family coverage premiums for firms that provide premium amounts as the average cost for all covered workers.

To ensure data accuracy we have several processes to review outliers and illogical responses. Every year several hundred firms are called back to confirm or correct responses. In some cases, answers are edited based on responses to open-ended questions or based on established logic rules.

Annual inflation estimates are calculated from April to April. The 12 month percentage change for this period was 2.0%.11 Data presented is nominal unless indicated specifically otherwise.

WEIGHTING

Because we select firms randomly, it is possible through the use of weights to extrapolate the results to national (as well as firm size, regional, and industry) averages. These weights allow us to present findings based on the number of workers covered by health plans, the number of total workers, and the number of firms. In general, findings in dollar amounts (such as premiums, worker contributions, and cost sharing) are weighted by covered workers. Other estimates, such as the offer rate, are weighted by firms.

Calculation of the weights follows a common approach. The employer weight was determined by calculating the firm’s probability of selection. This weight was trimmed of overly influential weights and calibrated to U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 Statistics of U.S. Businesses for firms in the private sector, and the 2012 Census of Governments totals. The worker weight was calculated by multiplying the employer weight by the number of workers at the firm and then following the same weight adjustment process described above. The covered-worker weight and the plan-specific weights were calculated by multiplying the percentage of workers enrolled in each of the plan types by the firm’s worker weight. These weights allow analyses of all workers covered by health benefits and of workers in a particular type of health plan.

The trimming procedure follows the following steps: First, we grouped firms into size and offer categories of observations. Within each strata, we calculated the trimming cut point as the median plus six times the interquartile range (M + [6 * IQR]). Weight values larger than this cut point are trimmed. In all instances, very few weight values were trimmed.

The survey collects information on primary and specialty care physician office visits for each plan type. Different plan types at the same firm may have different cost-sharing structures (e.g., copayments or coinsurance). Because the composite variables (using data from across all plan types) are reflective of only those plans with that provision, separate weights for the relevant variables were created in order to account for the fact that not all covered workers have such provisions.

To account for design effects, the statistical computing package R version 3.6.1 (2019-07-05) and the library “survey” version 3.36 were used to calculate standard errors.

STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS

All statistical tests are performed at the .05 confidence level. For figures with multiple years, statistical tests are conducted for each year against the previous year shown, unless otherwise noted. No statistical tests are conducted for years prior to 1999.

Statistical tests for a given subgroup (firms with 25-49 workers, for instance) are tested against all other firm sizes not included in that subgroup (all firm sizes NOT including firms with 25-49 workers, in this example). Tests are done similarly for region and industry; for example, Northeast is compared to all firms NOT in the Northeast (an aggregate of firms in the Midwest, South, and West). However, statistical tests for estimates compared across plan types (for example, average premiums in PPOs) are tested against the “All Plans” estimate. In some cases, we also test plan-specific estimates against similar estimates for other plan types (for example, single and family premiums for HDHP/SOs against single and family premiums for HMO, PPO, and POS plans); these are noted specifically in the text. The two types of statistical tests performed are the t-test and the Wald test. The small number of observations for some variables resulted in large variability around the point estimates. These observations sometimes carry large weights, primarily for small firms. The reader should be cautioned that these influential weights may result in large movements in point estimates from year to year; however, these movements are often not statistically significant. Standard Errors for most key statistics are available in a technical supplement available at http://www.kff.org/ehbs.

Due to the complexity of many employer health benefits programs, this survey is not able to capture all the components of any particular plan. For example, many employers have complex and varied prescription drug benefits, premium contributions, and incentives for wellness programs. We attempted to complete interviews with the person who is most knowledgeable about the firm’s health benefits. In some cases, the firm may not know details of some elements of their plan.

While we collect information on the number of workers enrolled in health benefits, the survey is not able to capture the characteristics of the workers offered or enrolled in any particular plan. As discussed above, statistics weighted by the percentage of employers often display a high level of variability.

2019 SURVEY

Starting in 2019, we discontinued a weighting adjustment informed by a follow-back survey of firms with 3-49 workers that refused to participate in the full survey. This adjustment was intended to reduce non-response bias in the offer rate statistic, under the assumption that firms that did not complete the survey were less likely to offer health benefits. The adjustment involves comparing the distribution of offering to non-offering firms in the full survey and the follow-back sample in the three smallest size categories (3-9, 10-24, 25-49). The adjustment is based on the differences between the two groups of firms and generally operates to adjust the weights of offering firms and non-offering firms to bring the counts closer together. However, if the distributions of the two groups differ to a statistically significant extent, we consider the follow-back survey to be a different population from the full survey and do not make any adjustment to the weights.

Although we cannot be sure of the reason, we are no longer witnessing the systematic upward bias on estimates for the offer rates of small firms that gave rise to the adjustment. Looking at the decade from 2010 to 2019, offer rates among firms responding to the follow-up survey have been higher for five of ten surveys. Firms with 3-49 employees responding to this follow-up survey have reported a higher offer rate than the full EHBS survey during the 2014, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019 surveys. An alternative way to measure non-response bias is to compare estimates throughout the fielding period.

In 2019, the percent of firms offering health benefit was similar in the last month of fielding to offer rates throughout the entire fielding period. Changes in both the survey methodology and the health insurance market have led us to become increasingly cautious about assuming that the follow back survey is a suitable proxy for the true population. Since 2014, we have collected offer rate information from firms before a final disposition is assigned. This method was introduced to reduce a bias in which firms who offer health benefits face a longer average survey than non-offering firms. This had the effect of increasing the percentage of firms for whom contact was made from whom we collected offer rate information. Additionally, we have also attempted to reduce non-response bias by increasing our data collection.

Recent changes in the marketplace also raise some concerns about the validity of the follow-back survey to be the basis for a weight adjustment. We have in recent years seen an increase in non-offering firms reporting that they are providing funds to employees to purchase non-group health insurance. We do not consider this to be an offer of health insurance by the firm, but we are concerned that the person who responds to the follow-back survey may not be able to make that distinction. The follow-back survey is a very simple set of questions asked to whoever answers the phone at a firm that refused to participate in the survey. In contrast, during the full-survey, we attempt to talk to the person most knowledgeable about health benefits, and the interviewers are trained to distinguish between types of benefit programs.

For 2019, making the weight adjustment would change offer rate statistic for all firms from 57% to 60%. Neither estimate is different than the 57% we reported last year (when the weight adjustment was not made because the statistical test indicated that the follow-back group was significantly different than the full survey group).

Starting in 2019, all presented calculations of out-of-pocket maximums strictly relied on an arithmetic average across all plans weighted by covered worker plan enrollment. In prior surveys, some figures (for example Figures 7.43, 7.45, and 7.46 in the 2018 report) were calculated based on the out-of-pocket maximum of the largest plan. This change did not meaningfully change any findings and ensured consistency within the out-of-pocket maximum section of the Employee Cost Sharing section.

For prescription drug coverage, similar to years past, if the firm reports that the worker pays the full cost for drugs on a particular tier and/or that the plan only offers access to a discount program, we do not consider this as offering covering for that drug tier. Starting this year, firms with multiple tiers that cover exclusively specialty drugs, were asked about the cost-sharing of the tier that is used most often. Cost-sharing for prescription drugs does not typically include mail order. Hospital, outpatient surgery and prescription drug cost-sharing was only asked of a firm’s largest plan type.

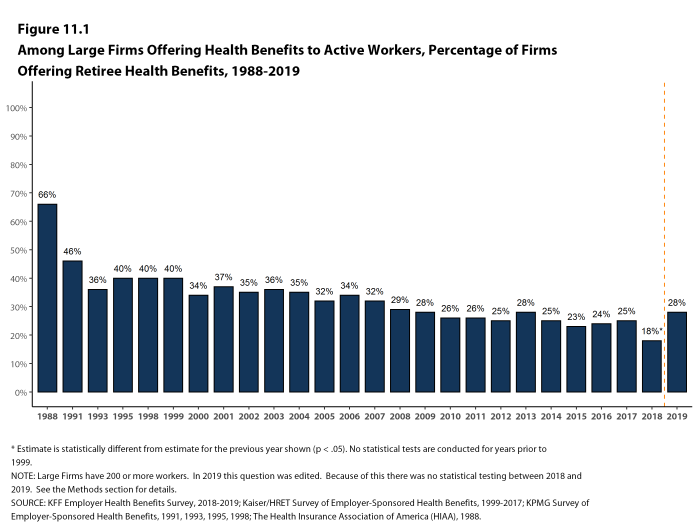

For 2019, we clarified the question that we use to ask firms whether or not they provide retiree health benefits; particularly, we added language that explicitly stated that firms that had terminated retiree health benefits but still has some retirees currently getting coverage, or that had current employees who will get retiree health coverage in the future, should answer yes to the question. We made this clarification in response to a large decline in the 2018 survey in the prevalence of retiree coverage (from 25% in 2017 to 18% in 2018). In the 2018 survey, we expressed concern that the then current public focus on public entities eliminating retiree benefits for future (not existing) retirees may be influencing the responses we were getting and said that we were going to add clarifying language to the survey question in future years.

For 2019, two open-ended questions were added to the survey in order to examine employer responses to the opioid crisis and obstacles preventing firms from adopting narrow network health plans. All responses to these questions were reviewed in a consistent manner by KFF staff to determine whether they could be recoded as an earlier multiple choice item, or if they could be sorted into new categories.

To increase participation in the final two weeks of the survey, a financial incentive was offered to firms with 3-9 employees, but only 6 firms that completed the survey within that time period qualified for the incentive. All respondents received a printed copy of the survey findings.

OTHER RESOURCES

Additional information on the 2019 Employer Health Benefit Survey is available at http://ehbs.kff.org/, including an article in the Journal Health Affairs, an interactive graphic and historic reports. Standard Errors for some statistics are available in the online technical supplement. Researchers may also request a public use dataset here: https://www.kff.org/contact-us/

The survey design and methods section found on our website (http://ehbs.kff.org/) contains an extended methods document that was not included in the portable document format (PDF) or the printed versions of this book. Readers interested in the extended methodology should consult the online edition of this publication.

As part of the Peterson Center on Healthcare’s work on the Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker, additional questions on provider networks were included in the 2019 survey. The authors thank Tricia Neuman, Gretchen Jacobson, Karen Pollitz, Larry Levitt, and Cynthia Cox for their contributions.

Published: September 25, 2019. Last Updated: September 23, 2019.

HISTORICAL DATA

Data in this report focus primarily on findings from surveys conducted and authored by the Kaiser Family Foundation since 1999. Between 1999 and 2017, the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) co-authored this survey. HRET’s divestiture had no impact on our survey methods, which remain the same as years past. Prior to 1999, the survey was conducted by the Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA) and KPMG using a similar survey instrument, but data are not available for all the intervening years. Following the survey’s introduction in 1987, the HIAA conducted the survey through 1990, but some data are not available for analysis. KPMG conducted the survey from 1991-1998. However, in 1991, 1992, 1994, and 1997, only larger firms were sampled. In 1993, 1995, 1996, and 1998, KPMG interviewed both large and small firms. In 1998, KPMG divested itself of its Compensation and Benefits Practice, and part of that divestiture included donating the annual survey of health benefits to HRET.

This report uses historical data from the 1993, 1996, and 1998 KPMG Surveys of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits and the 1999-2017 Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits. For a longer-term perspective, we also use the 1988 survey of the nation’s employers conducted by the HIAA, on which the KPMG and KFF surveys are based. The survey designs for the three surveys are similar.

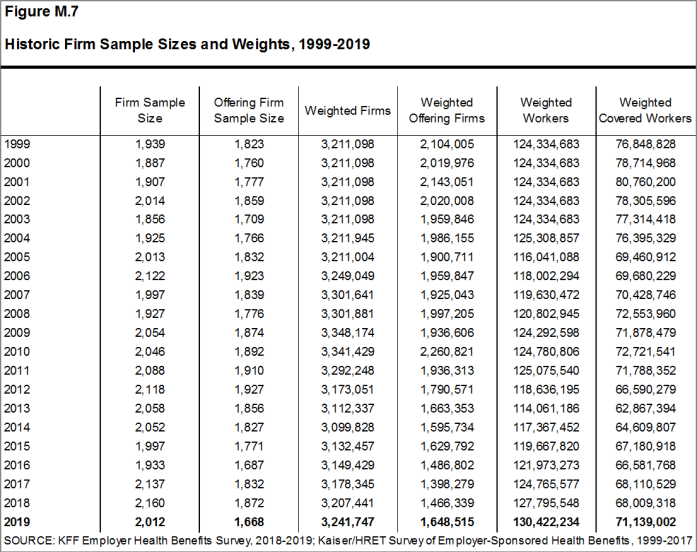

[Figure M.7] displays the historic sample sizes and weights of firms, workers, and covered workers (employees receiving coverage from their employer).

Figure M.7: Historic Firm Sample Sizes and Weights, 1999-2019

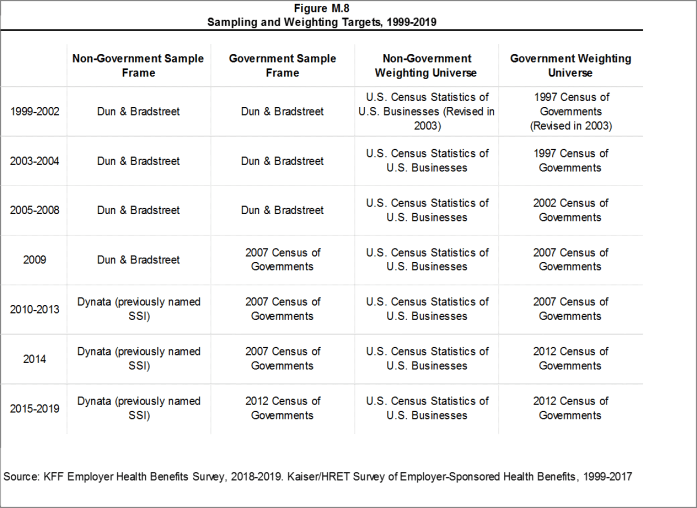

[Figure M.8] displays the historic sample frames and weighting universes.

Figure M.8: Sampling and Weighting Targets, 1999-2019

1999

The Kaiser Family Foundation and The Health Research and Educational Trust (Kaiser/HRET) began sponsoring the survey of employer-sponsored health benefits supported for many years by KPMG Peat Marwick LLP, an international consulting and accounting firm. In 1998, KPMG divested itself of its Compensation and Benefits Practice, and donated the annual survey of health benefits to HRET, a non-profit research organization affiliated with the American Hospital Association. From 1999 until 2017, the survey was conducted under a partnership between HRET and The Kaiser Family Foundation, a health care philanthropy and policy research organization that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente or Kaiser Industries. Starting in 1999, survey continued a core set of questions from prior KPMG surveys, but was expanded to include small employers and a variety of policy-oriented questions. Some reports include data from the 1993, 1996 and 1998 KPMG Surveys of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits. For a longer-term perspective, we also use the 1988 survey of the nation’s employers conducted by the Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA), on which the KPMG, Kaiser/HRET, and Kaiser Family Foundation surveys were based. Many of the questions in the HIAA, KPMG, Kaiser/HRET, and Kaiser Family Foundation surveys are identical, as is the sample design. Since Point-of-Service (POS) plans did not exist in 1988, reports do not include statistics for this plan type in that year. Starting in 1999, Kaiser/HRET drew its sample from a Dun & Bradstreet list of the nation’s private and public employers with three or more workers. To increase precision, Kaiser/HRET stratified the sample by industry and the number of workers in the firm. Kaiser/HRET attempted to repeat interviews with many of the 2,759 firms interviewed in 1998 and replaced non-responding firms with another firm from the same industry and firm size. As a result, 1,377 firms in the 1999 total sample of 1,939 firms participated in both the 1998 and 1999 surveys.

For more detail about the 1999 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2000

Kaiser/HRET attempted to repeat interviews with many of the 1,939 firms interviewed in 1999 and replaced non-responding firms with other firms of the same industry and firm size. As a result, 982 firms in the 2000 survey’s total sample of 1,887 firms participated in both the 1999 and 2000 surveys. The overall response rate was 45% down from 60% in 1999. Contributing to the declining response rate was the decision not to re-interview any firms with 3-9 workers who participated in the 1999 survey. In 1999, the survey weights had instead been adjusted to control for the fact that firms with 3-9 workers that are in the panel (responded in either 1998 or 1999) are biased in favor of offering a health plan. The response rate in 2000 for firms with 3-9 workers was 30%.

For more detail about the 2000 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2001

For more detail about the 2001 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2002

The list of imputed variables was greatly expanded in 2002 to also include self-insurance status, level of benefits, prescription drug cost-sharing, copay and coinsurance amounts for prescription drugs, and firm workforce characteristics such as average income, age and part-time status. On average, 2% of these observations are imputed for any given variable. The imputed values are determined based on the distribution of the reported values within stratum defined by firm size and region.

For more detail about the 2002 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2003

The calculation of the weights followed a similar approach to previous years, but with several notable changes in 2003. First, as in years past, the basic weight was determined, followed by a nonresponse adjustment added this year to reflect the fact that small firms that do not participate in the full survey are less likely to offer health benefits and, consequently, are unlikely to answer the single offer rate question. To make this adjustment, Kaiser/HRET conducted a follow-up survey of all firms with 3-49 workers that did not participate in the full survey. Each of these 1,744 firms was asked the single question, “Does your company offer or contribute to a health insurance program as a benefit to its employees?” The main difference between this follow-up survey and the original survey is that in the follow-up survey the first person who answered the telephone was asked whether the firm offered health benefits, whereas in the original survey the question was asked of the person who was identified as most knowledgeable about the firm’s health benefits. Conducting the follow-up survey accomplished two objectives. First, statistical techniques (a McNemar analysis which was confirmed by a chi-squared test) demonstrated that the change in method-speaking with the person answering the phone rather than a benefits manager-did not bias the results of the follow-up survey. Analyzing firms who responded to the offer question twice, in both the original and follow-up survey, proved that there was no difference in the likelihood that a firm offers coverage based on which employee answered the question about whether a firm offers health benefits. Second, the follow-up survey demonstrated that very small firms not offering health benefits to their workers are less likely to answer the one survey question about coverage. Kaiser/HRET analyzed the group of firms that only responded to the follow-up survey and performed a t-test between the firms who had responded to the initial survey as well as the follow-up, and those who only responded to the follow-up. Tests confirmed the hypothesis that the firms that did not answer the single offer rate question in the original survey were less likely to offer health benefits. To adjust the offer rate data for this finding an additional non-response adjustment was applied to increase the weight of firms in the sample that do not offer coverage. The second change to the weighting method in 2003 was to trim the weights in order to reduce the influence of weight outliers. On occasion one or two firms will, through the weighting process, represent a highly disproportionate number of firms or covered workers. Rather than excluding these observations from the sample, a set cut point that would minimize the variances of several key variables (such as premium change and offer rate) was determined. The additional weight represented by outliers is then spread among the other firms in the same sampling cell. Finally, a post-stratification adjustment was applied. In the past, Kaiser/HRET was poststratified back to the Dun & Bradstreet frequency counts. Concern over volatility of counts in recent years led to the use of an alternate source for information on firm and industry data. This year the survey uses the recently released Statistics of U.S. Businesses conducted by the U.S. Census as the basis for the post-stratification adjustment. These Census data indicate the percentage of the nation’s firms with 3-9 workers is 59% rather than the higher percentages (e.g., 76% in 2002) derived from Dun & Bradstreet’s national database. This change has little impact on worker-based estimates, since firms with 3-9 workers accounted for less than 10% of the nation’s workforce. The impact on estimates expressed as a percentage of employers (e.g., the percent of firms offering coverage), however, may be significant. Due to these changes, Kaiser/HRET recalculated the weights for survey years 1999-2002 and modified estimates published in the survey where appropriate. The vast majority of these estimates are not statistically different. However, please note that the survey data published starting in 2003 varies slightly from previously published reports.

For more detail about the 2003 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2004

For more detail about the 2004 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2005

In 2005, the Kaiser/HRET survey added two additional sections to the questionnaire to collect information about high-deductible health plans (HDHP) that are offered along with a health reimbursement account (HRA) or are health savings account (HSA) qualified. Questions in these sections were asked of all firms offering these plan types, regardless of enrollment. Specific weights were also created to analyze the HDHP plans that are offered along with HRAs or are HSA qualified. These weights represent the proportion of employees enrolled in each of these arrangements.

We updated our data to reflect the 2002 Census of Governments. We also removed federal government employee counts from our post-stratification.

For more detail about the 2005 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2006

For the first time in 2006, Kaiser/HRET asked questions about the highest enrollment HDHP/SO as a separate plan type, equal to the other plan types. In prior years, data on HDHP/SO plans were collected as part of one of the other types of plans. Therefore, the removal of HDHP/SOs from the other plan types may affect the year to year comparisons for the other plan types. Given the decline in conventional health plan enrollment and the addition of HDHP/SO as a plan type option, Kaiser/HRET eliminated nearly all questions pertaining to conventional coverage from the survey instrument. We continue to ask firms whether or not they offer a conventional health plan and, if so, how much their premium for conventional coverage increased in the last year, but respondents are not asked additional questions about the attributes of the conventional plans they offer. Because we have limited information about conventional health plans, we must make adjustments in calculating all plan averages or distributions. In cases where a firm offers only conventional health plans, no information from that respondent is included in all plan averages. The exception is for the rate of premium growth, for which we have information. If a firm offers a conventional health plan and at least one other plan type, for categorical variables we assign the values from the health plan with the largest enrollment (other than the conventional plan) to the workers in the conventional plan. In the case of continuous variables, covered workers in conventional plans are assigned the weighted average value of the other plan types in the firm.

The survey newly distinguished between plans that have an aggregate deductible amount in which all family members’ out-of-pocket expenses count toward the deductible and plans that have a separate amount for each family member, typically with a limit on the number of family members required to reach that amount.

In 2006, Kaiser/HRET began asking employers if they had a health plan that was an exclusive provider organization (EPO). We treat EPOs and HMOs together as one plan type and report the information under the banner of “HMO”; if an employer sponsors both an HMO and an EPO, they are asked about the attributes of the plan with the larger enrollment.

Kaiser/HRET made a slight change to one of the industry groups: we removed Wholesale from the group that also included Agriculture, Mining and Construction. The nine industry categories now reported are: Agriculture/Mining/Construction, Manufacturing, Transportation/Communications/Utilities, Wholesale, Retail, Finance, Service, State/Local Government, and Health Care.

Starting in 2006, we made an important change to the way we test the subgroups of data within a year. Statistical tests for a given subgroup (firms with 25-49 workers, for instance) are tested against all other firm sizes not included in that subgroup (all firm sizes NOT including firms with 25-49 workers in this example). Tests are done similarly for region and industry: Northeast is compared to all firms NOT in the Northeast (an aggregate of firms in the Midwest, South, and West). Statistical tests for estimates compared across plan types (for example, average premiums in PPOs) are tested against the “All Plans” estimate. In some cases, we also test plan specific estimates against similar estimates for other plan types (for example, single and family premiums for HDHP/SOs against single and family premiums in HMO, PPO, and POS plans). Those are noted specifically in the text. This year, we also changed the type of Chi-square test from the Chi-square test for goodness-of-fit to the Pearson Chi-square test. Therefore, in 2006, the two types of statistical tests performed are the t-test and the Pearson Chi-square test.

For more detail about the 2006 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2007

Kaiser/HRET drew its sample from a Survey Sampling Incorporated list (based on an original Dun and Bradstreet list) of the nation’s private and public employers with three or more workers.

In prior years, many variables were imputed following a hotdeck approach, while others followed a distributional approach (where values were randomly determined from the variable’s distribution, assuming a normal distribution). This year, all variables are imputed following a hotdeck approach. This imputation method does not rely on a normal distribution assumption and replaces missing values with observed values from a firm with similar characteristics, in this case, size and industry. Due to the low imputation rate for most variables, the change in methodology is not expected to have a major impact on the results. In some cases, due to small sample size, imputed outliers are excluded. There are a few variables that Kaiser/HRET has decided should not be imputed; these are typically variables where “don’t know” is considered a valid response option (for example, firms’ opinions about effectiveness of various strategies to control health insurance costs).

The survey now contains a few questions on employee cost sharing that are asked only of firms that indicate in a previous question that they have a certain cost-sharing provision. For example, the copayment amount for prescription drugs is asked only of those that report they have copayments for prescription drugs. Because the composite variables are reflective of only those plans with the provision, separate weights for the relevant variables were created in order to account for the fact that not all covered workers have such provisions.

For more detail about the 2007 survey, see the Survey Methodology section of that year’s report.

2008

National Research, LLC (NR), our Washington, D.C.-based survey research firm, introduced a new CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interview) system at the end of 2007, and, due to several delays in the field, obtained fewer responses than expected. As a result, an incentive of $50 was offered during the final two and a half weeks the survey was in the field. Kaiser/HRET compared the distribution of key variables between firms receiving the incentive and firms not receiving the incentive to determine any potential bias. Chi-square test results were not significant, suggesting minimal to no bias.

In 2008, we changed the method used to report the annual percentage premium increase. In prior years, the reported percentage was based on a series of questions that asked responding firms the percentage increase or decrease in premiums from the previous year to the current year for a family of four in the largest plan of each plan type (e.g., HMO, PPO). The reported premium increase was the average of the reported percentage changes (i.e., 6.1% for 2007) weighted by covered workers. This year, we calculate the overall percentage increase in premiums from year to year for family coverage using the average of the premium dollar amounts for a family of four in the largest plan of each plan type reported by respondents and weighted by covered workers (i.e., $12,106 for 2007 and $12,680 for 2008, an increase of 5%). A principal advantage of using the premium dollar amounts to calculate the annual change in premiums is that we are better able to capture changes in the cost of health insurance for those firms that are newly in the market or that change plan types, especially those that move to plans with very different premium levels. For example, in the first year that a firm offers a plan of a new plan type, such as a consumer-directed plan, the firm can report the level of the premium they paid, but using the previous method would be unable to report the rate of change from the previous year since the plan was not previously offered. If the premium for the new plan is relatively low compared to other premiums in the market, the relatively low premium amount that the firm reports will tend to lower the weighted average premium dollar amount reported in the survey, but the firm responses would not provide any information to the percentage premium increase question. Another advantage of using premium dollar amounts to examine trends is that these data directly relate to the other findings in the survey and better address a principal public policy issue (i.e., what was the change in the cost of insurance over some past period). Many users noted, for example, that the percentage change calculated from the reported premium dollar amounts between two years did not directly match the reported average premium increase for the same period. There are several reasons why we would not expect these questions to produce identical results: 1) they are separate questions subject to varying degrees of reporting error, 2) firms could report a premium dollar amount for a plan type they might not have offered in the previous year, therefore, contributing information to one measure but not the other, or 3) firms could report a premium dollar amount for a plan that was not the largest plan of that type in the previous year. Although the two approaches have generated similar results in terms of the long-term growth rate of overall family premiums, there are greater discrepancies in trends for subgroups like small employers and self-funded firms. Focusing on the dollar amount changes over time will provide a more reliable and consistent measure of premium change that also is more sensitive to firms offering new plan options.

As we have in past years, this year we collected information on the cost-sharing provisions for hospital admissions and outpatient surgery that is in addition to any general annual plan deductible. However, for the 2008 survey, we changed the structure of the question and now include “separate annual deductible or hospital admissions” as a response option rather than collecting the information through a separate question. We continue to examine and sometimes modify the questions on hospital and outpatient surgery cost sharing because this can be a complex component of health benefit plans. For example, for some plans it is difficult to distinguish a separate hospital deductible from one categorized as a general annual deductible, where office visits and preventive care are covered and the deductible only applies to hospital use. Because this continues to be a point of confusion, we continue to refine the series of questions in order to clearly convey the information we are attempting to collect from respondents.