How Many Employers Could Be Affected by the High-Cost Plan Tax

Issue Brief

Unlike other compensation, employer based health benefits are not taxed, meaning employees may receive thousands of dollars of tax benefits if they get their health insurance at work. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the exclusion cost the federal government $300 billion in forgone revenues. Economists have long argued that providing this tax break encourages employers to offer more generous benefit plans than they otherwise would because employees prefer to receive additional benefits (which are not taxed) in lieu of wages (which are taxed). Employees with generous plans use more health care because they face fewer out-of-pocket costs, which economists argue contributes to the overall growth in health care spending.

To address this issue, the ACA included the High-Cost Plan Tax (HCPT), sometimes referred to as the “Cadillac Plan Tax”. The HCPT is a tax on employers based on the value of plans they provide in excess of designated thresholds, originally set at $10,200 for single coverage and $27,500 for family coverage. These caps grow annually with inflation. The CBO estimates that the thresholds will be $11,200 for individual coverage and $30,100 for family coverage when the law takes effect in 2022. Some employers with workers in high-risk industries or older workers face higher caps. Originally scheduled to take effect in 2018, the effective date of the HCPT has been twice delayed, most recently to 2022. While many employers anticipate the provision will be either delayed again or repealed, the tax as currently structure is projected to raise 193 billion dollars between 2022 and 2029.

We previously analyzed the percentage of employers with plans that would exceed the HCPT thresholds. Our purpose here is not to estimate the number of employers or employees who actually would pay the tax, but to look at the share of current plans that might meet the definition of “high cost” over time, assuming modest premium growth and no changes in plan design (i.e., we assume that employers do not increases deductibles to avoid the taxes). These estimates can be understood as the share of employers who have plans where the cost for some employees will exceed specified thresholds, presenting employers with the choice of restructuring their benefits or increasing either the firm’s or their employee’s tax liabilities.

As with our previous analysis, we focus on the value of plans providing single coverage due to the complexity of how family coverage is defined. There are some aspects of these proposals that we do not include. For example, the premiums for tax-preferred dental and vision coverage as well as certain workplace health clinics are included in total benefit costs but we do not have information on the amounts.

The High-Cost Plan Tax

The HCPT is a 40% tax on the cost of employer plans in excess of specified thresholds, which are projected to be $11,200 for individual coverage and $30,100 for family coverage. The tax is calculated for each employee at a firm based on their total health benefits, including spending on:

- The average cost for the health insurance plan (whether insured or self-funded);

- Employer contributions to a health savings account (HSA), Archer medical spending account (MSA) or health reimbursement arrangement (HRA);

- Contributions (including employee-elected payroll deductions and non-elective employer contributions) to a Flexible Spending Account (FSA);

- The value of coverage in certain on-site medical clinics; and

- The cost for certain limited-benefit plans if they are provided on a tax-preferred basis.

Consistent with our previous analysis, we use information from the 2018 Kaiser Employer Health Benefits Survey to estimate the share of employers with plans that would exceed the threshold. The survey contains information about plan premiums, employer contributions to health savings accounts and health reimbursement arrangements, and the amounts that employers permit their employees to contribute to a flexible spending account. We compute the total cost for each plan offered by an employer by adding together the total plan premium (employer and employee share), the employer contribution to an HSA and a portion of the promised HRA contribution as well as the permitted amount employees can contribute to an FSA. Because employees have a choice of whether or not to contribute to an FSA, we provide estimates with and without FSA amounts included in the plan total costs. These plan costs are trended forward based on the projected annual per-capita increases in spending in employer-provided coverage from the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHE).

This @KaiserFamFound analysis estimates that the #CadillacTax on high-cost health plans could affect 1 in 5 employers when it starts in 2022 – and even more over time or when accounting for workers’ voluntary FSA contributions.

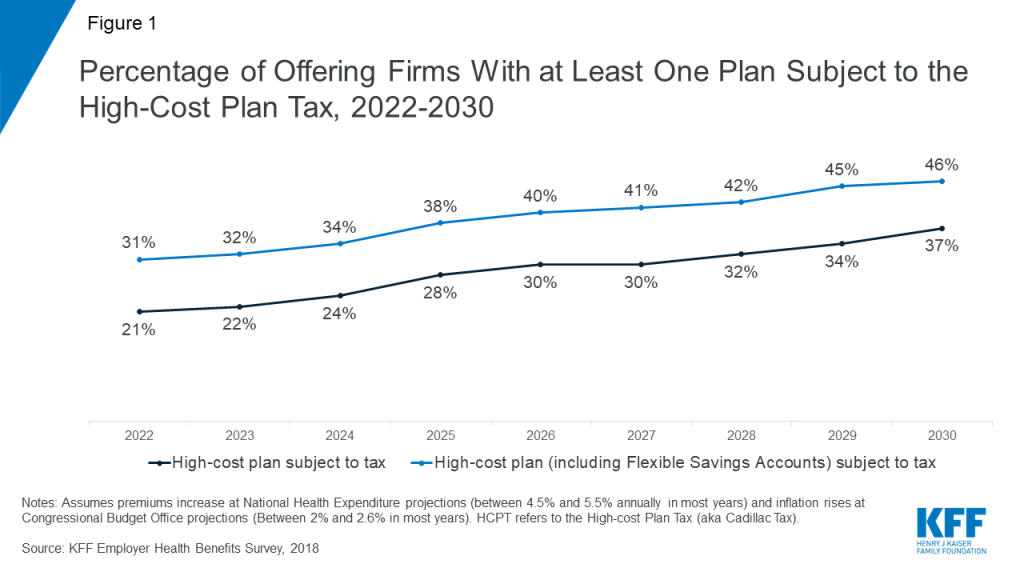

When the HCPT takes effect in 2022, an estimated 21% of employers offering health benefits will have at least one plan whose premium and account contributions would exceed the HCPT threshold (Figure 1). When potential FSA contributions are included, the percentage climbs to 31%. The impact of adding the FSA contributions is substantial because the maximum FSA contribution employees can elect (up to an estimated $2,900 in 2022) is quite large relative to the threshold. Since not all employees offered an FSA option make the maximum contribution, and some do not contribute, the threshold will be reached with respect to some employees at the firm and not others.

The percentage of employers with a plan reaching the threshold is projected to grow fairly rapidly over time, to 28% in 2025 and 37% in 2030 without including potential FSA contributions, and to 38% in 2025 and 46% in 2030 when they are included. This growth occurs because our assumed premium growth, which averages about 4.9% annually over the period, is higher than inflation projections (about 2.4%). If premiums grow more slowly than projected, the percentage of employers with a plan reaching the threshold would be smaller. Twenty-one percent of firms offered a health plan in 2018 which already exceeded the HCPT thresholds, including 11% of firms exceeding the threshold without including FSA contributions.

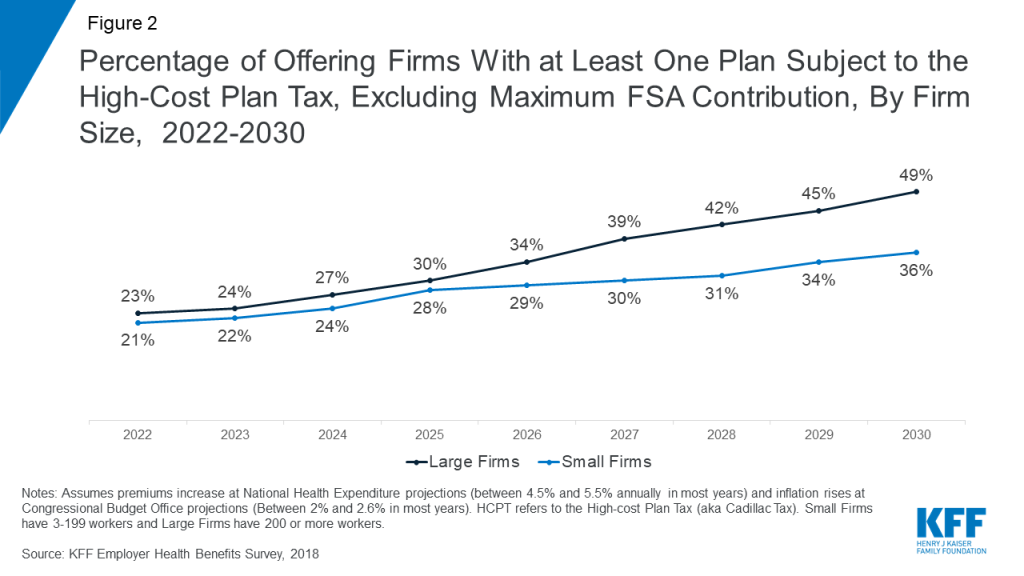

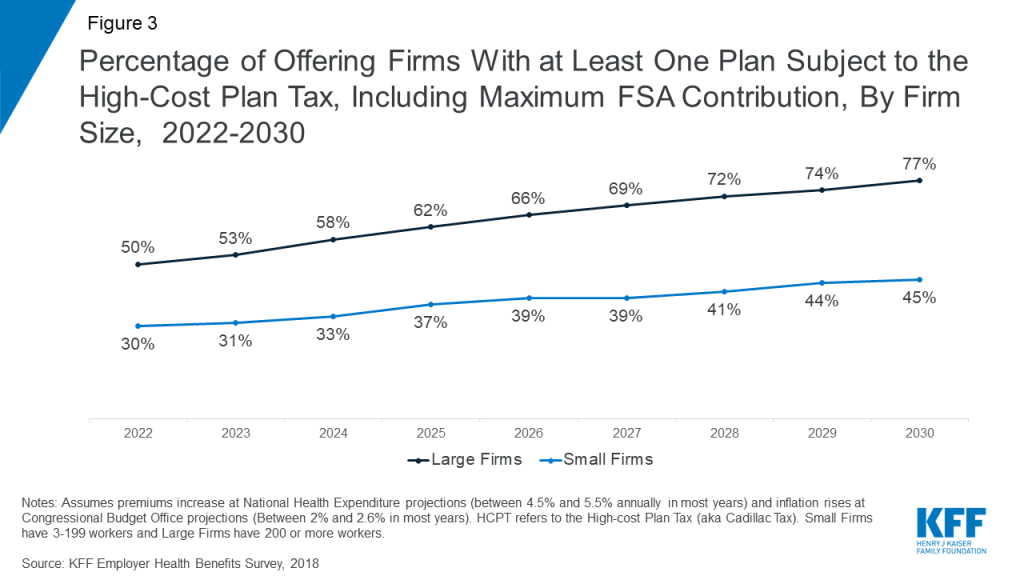

Without other plan changes a larger percentage of large firms (200 or more workers) would sponsor health programs which exceed the thresholds than smaller firms (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Excluding any FSA contributions, 49% of large firms and 36% of smaller firms would have a program subject to the tax in 2030.

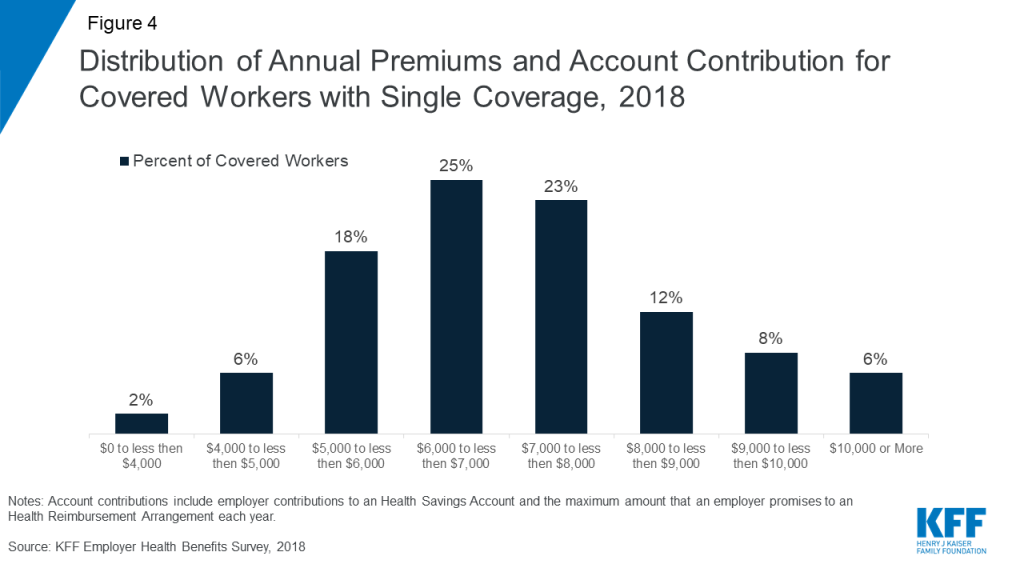

Both because of varying regional costs, and differences in plan generosity there is considerable variation in the cost of employer plans. Fourteen percent of covered workers are enrolled in a plan where the premium and employer account contribution exceed $9,000 in 2018. Conversely, 8% of covered workers are in a plan where the premium and account contributions are less than $5,000 (Figure 4).

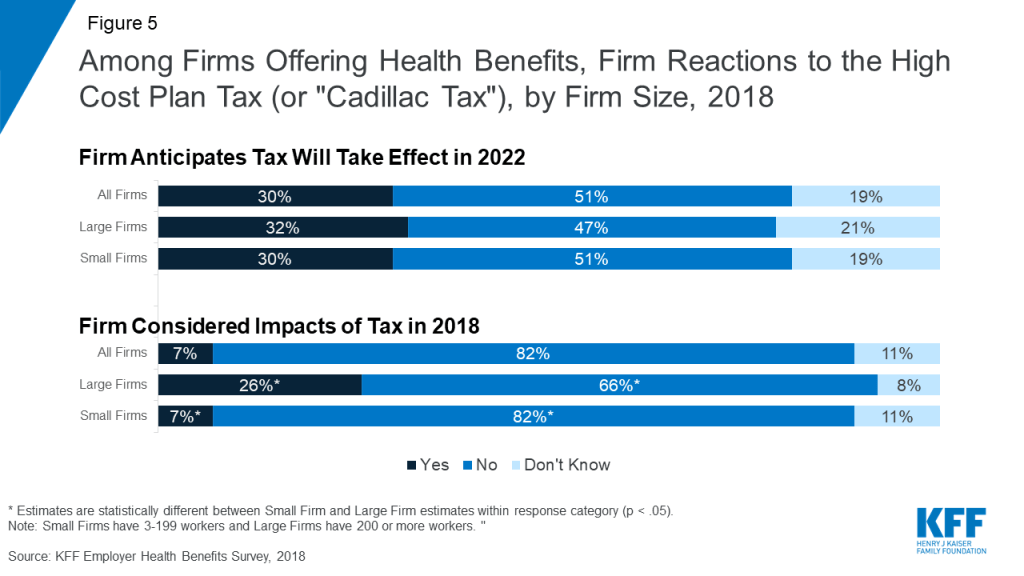

There remains considerable uncertainty whether the HCPT will be implemented in 2022, delayed or repealed. In 2018, less than one-third (30%) of firms offering health benefits anticipate that the high cost plan tax will take effect as scheduled in 2022. Despite this, many employers, in particular large employers are already making changes to their health benefits to either reduce or avoid tax-liability if the provision takes effect. Among firms offering health benefits, 7% of small firms and 26% of large firms say they considered the potential impact of the upcoming tax when they made their benefit decisions for 2018.

Discussion

In 2018, 11% of employers offering health benefits, sponsored a plan which exceeds the HCPT tax thresholds, an additional 21% surpass theses thresholds when an FSA is included in plan costs. Given that most estimates suggest that health costs will continue to increase faster than inflation over time, a growing number of employers will be subject to the tax unless they make changes to their health programs. We estimate if the tax takes effect in 2022, 31% will be subject to the tax, increasing to 46% by 2030 unless firms reduce costs. Excluding workers FSA contributions, 21% of firms will be subject to the tax in 2022, increasing to 37% in 2030.

In addition to raising revenue to fund the expansion of coverage under the ACA, the HCPT provides powerful incentives to control health plans costs over time, whether through efficiency gains or shifts in costs to workers in the form of higher deductibles and other patient cost-sharing. While many employers do not expect that the tax will take effect in 2022, others are already amending their health programs in anticipation. If the HCPT is not delayed again, we can expect employers will continue to modify their offerings to limit their liability.

Methods

We used information about the premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance from the 2018 Kaiser Employer Health Benefits Survey (EHBS) to estimate the percentage of employers that would have at least one health plan subject to the law. The EHBS is an annual survey that collects information on health benefits from more than 2,100 employers with three or more employees. This method is largely consistent with our earlier estimates.

The EHBS collects information from employers about their largest plan for up to four plan types — health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point of service plan (POS), and high deductible health plan offered with a savings option (HDHP/SO). An HDHP/SO is a plan with a single deductible of $1,000 or more offered with a health reimbursement arrangement (HRA), or a health plan that qualifies the employee to make contributions to a Health Saving Account (HSA). For HDHP/SOs, the amounts that employers contribute to employees’ HSAs or make available to employees through HRAs are also collected. The 2018 EHBS includes information on the percentage of employers who sponsor a flexible spending account (FSA) and the maximum amount that they allow employees to contribute. FSAs are tax-preferred accounts employers may establish for their employees, so they can use pre-tax dollars for some medical spending. While three-quarters of large employers (those with 200 or more workers) sponsor FSAs, the ACA placed limits on the maximum amount that an employee may contribute ($2,650 in 2018).

Since HRAs are notional accounts, employers are not required to actually transfer funds until an employee incurs expenses. Thus, employers may not expend the entire amount that they commit to make available to their employees through an HRA. We therefore counted half of an employers total HRA contribution towards the plans total cost.

For the estimates, we took the single premium for each health plan offered by responding employers and increased them by National Health Expenditure Accounts (Table 3) projections in the annual percent change in private health insurance. For HSA-qualified plans, we added the amount that employers contribute to employees’ HSAs to the premium. For high deductible health plans with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA), the survey collects information about the amounts employers make available to employees, but not the amounts that are actually contributed. To be conservative, we added one-half of the amounts that employers make available through the HRA to the plan premium. The HSA and HRA amounts were also increased by NHE projections. For employers that reported offering an FSA, we added the maximum contribution the firm allows adjusted for inflation to the estimated premium for each plan type except HSA-qualified plans. We did not add the FSA amount to the premium for HSA-qualified plans because generally a person cannot establish an HSA if they have an FSA that could reimburse expenses before the plan deductible is met. We used the maximum contribution amount because we were evaluating if the cost for the plan could exceed the threshold for an employee. We used the projections in the CBO’s “Options for Reducing the Deficit: 2019 to 2028” for the threshold in 2022 and then assumed it increased at the Congressional Budget Office’s 2019 projections of the Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) (Table 2-3).