Loneliness and Social Isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An International Survey

Overview

The Kaiser Family Foundation, in partnership with The Economist, conducted a cross-country survey of adults in United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan to examine people’s views of and experiences with loneliness and social isolation. The survey, the second in partnership with The Economist, explores the public’s perceptions of the issue, including their views of the role of government and society in helping to reduce it, and how technology contributes to or stems the problem. It includes additional interviews with individuals who report always or often feeling lonely, left out, isolated or that they lack companionship to better understand the personal characteristics and life circumstances associated with these feelings, the reported causes of loneliness, and how people are coping.

Coverage from The Economist:

Key Findings: Introduction

In recent years, the issue of social isolation and loneliness has garnered increased attention from researchers, policymakers, and the public as societies age, the use of technology increases, and concerns about the impact of loneliness on health grow. To understand more about how people view the issue of loneliness and social isolation, the Kaiser Family Foundation, in partnership with The Economist, conducted a cross-country survey of adults in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. The survey included additional interviews with individuals who report always or often feeling lonely, left out, isolated or that they lack companionship to better understand the personal characteristics and life circumstances associated with these feelings, the reported causes of loneliness, and how people are coping.

Key Findings

Some of the key findings from the survey across all three countries are as follows.

1 in 5 Americans always or often feel lonely or socially isolated, including many whose health, relationships and work suffers as a result. More in 3-country @KaiserFamFound/@Economist survey

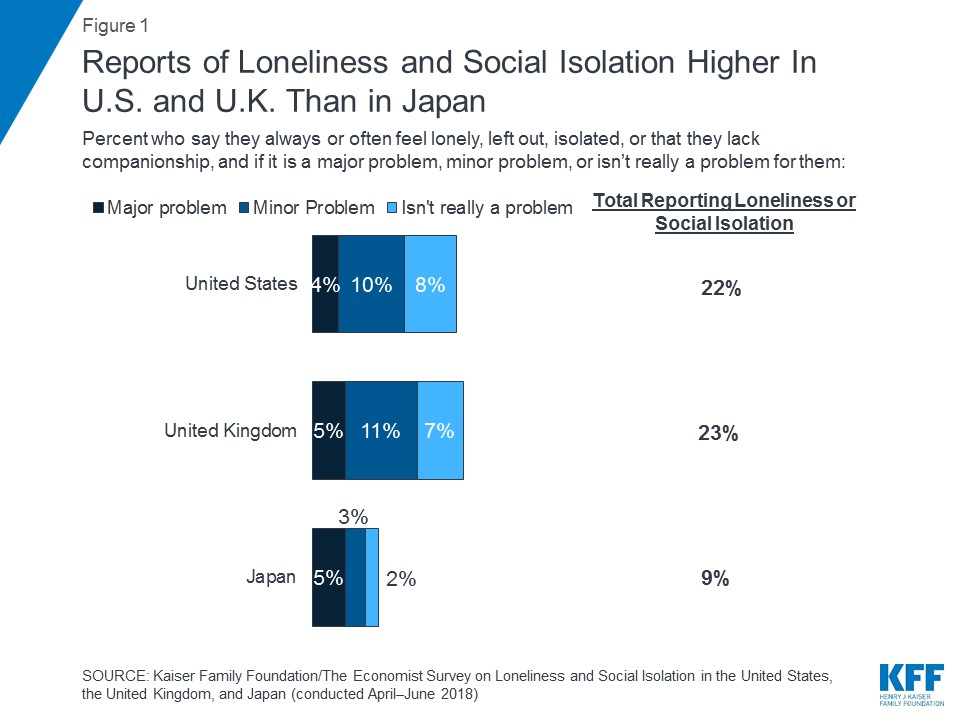

- More than two in ten report loneliness or social isolation in the U.K. and the U.S., double the share in Japan. More than a fifth of adults in the United States (22 percent) and the United Kingdom (23 percent) as well as one in ten adults (nine percent) in Japan say they often or always feel lonely, feel that they lack companionship, feel left out, or feel isolated from others, and many of them say their loneliness has had a negative impact on various aspects of their life. For example, across countries, about half or more reporting loneliness say it has had a negative impact on their personal relationships or their physical health. While loneliness is often thought of as a problem mainly affecting the elderly, the majority of people reporting loneliness in each country are under age 50. They’re also much more likely to be single or divorced than others.

- Loneliness appears to occur in parallel with reports of real life problems and circumstances. Across the three countries, people reporting loneliness are more likely to report being down and out physically, mentally, and financially. People experiencing loneliness disproportionately report lower incomes and having a debilitating health condition or mental health conditions. About six in ten say there is a specific cause of their loneliness, and, compared to those who are not lonely, they more often report being dissatisfied with their personal financial situation. They are also more likely to report experiencing negative life events in the past two years, such as a negative change in financial status or a serious illness or injury. Three in ten say their loneliness has led them to think about harming themselves.

- Those reporting loneliness appear to lack meaningful connections with others. Those reporting loneliness in each country report having fewer confidants than others and two-thirds or more say they have just a few or no relatives or friends living nearby who they can rely on for support. While individuals who report loneliness are more likely to express dissatisfaction with the number of meaningful connections they have with family, friends and neighbors, in the U.K. and the U.S., many still report talking to family and friends frequently by phone or in person. In Japan, reports of communication with family and friends are much less frequent, regardless of whether someone reports loneliness.

- Among the public at large, across countries, many have heard of the issue but views vary on the reasons for loneliness and who is responsible for helping to reduce it. Across the U.S., the U.K. and Japan, majorities say they have heard at least something about the issues of loneliness and social isolation in their country. In the U.S., the public is divided as to whether loneliness and social isolation are more of a public health problem or more of an individual problem (47 percent vs. 45 percent), and a large majority (83 percent) see individuals and families themselves playing a major role in helping to reduce loneliness and social isolation in society today and fewer see a major role for government (27 percent). In contrast, residents of the U.K. and Japan are more likely to see the issue as a public health problem than an individual issue (66 percent vs. 27 percent in the U.K. and 52 percent vs. 41 percent in Japan). And, while large majorities in the U.K. and Japan also think individuals and families should play a major role in stemming the problem, six in ten also see a major role for government, unlike in the U.S. A majority of people in the U.K. say “cuts in government social programs” is a major reason why people there are lonely or socially isolated, compared to minorities in the U.S. and Japan.

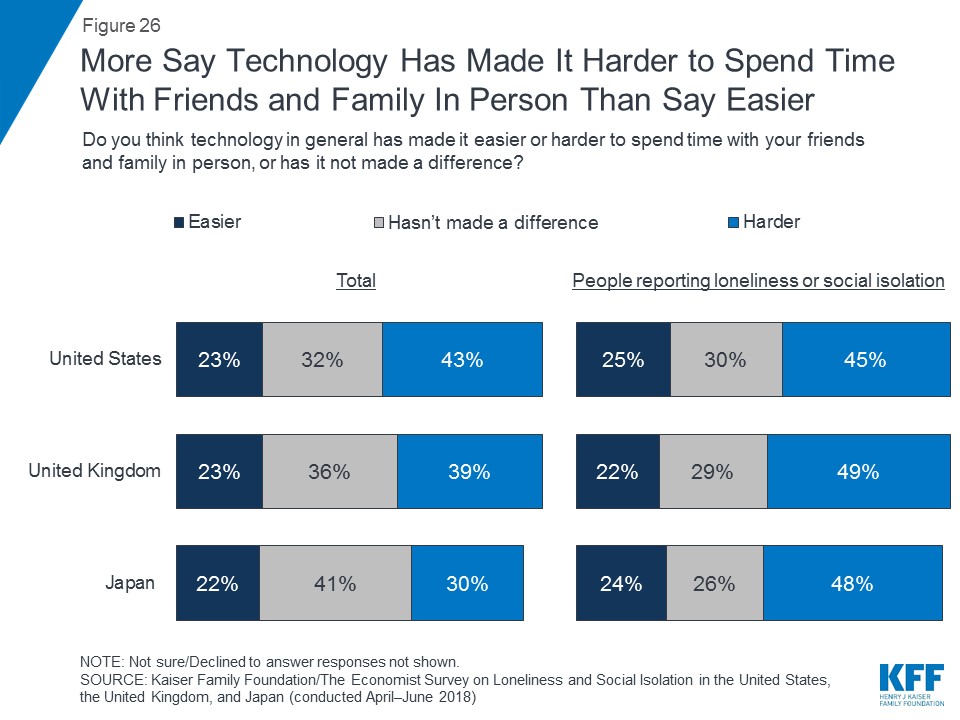

- Some are critical of the role technology plays in loneliness and isolation, but some see social media as an opportunity for connection. Many in the U.S. (58 percent) and U.K. (50 percent) view the increased use of technology as a major reason why people are lonely or socially isolated, whereas fewer people in Japan say the same (26 percent). Across countries, more say technology in general has made it harder to spend time with friends and family in person than say it has made it easier. However, when it comes to social media specifically, in each country, more say that they think their ability to connect with others in a meaningful way is strengthened by social media rather than weakened. But, for those experiencing loneliness or social isolation personally in the U.K. and the U.S., they are divided as to whether they think social media makes their feelings of loneliness better or worse. In addition, people who report being socially isolated or lonely in each country are not more likely than their peers to report using social media.

- Despite fewer people in Japan reporting loneliness, reports of the severity of the experience are worse. Half of those experiencing loneliness in Japan (or 5 percent of residents of Japan overall) say it is a major problem for them, compared to a fifth of those experiencing loneliness in the U.S. and the U.K. In Japan, more than a third (35 percent) of those who self-identify as lonely say they have felt isolated or lonely for more than 10 years, compared to a fifth of those in the U.S. (22 percent) or the U.K. (20 percent). Half of those reporting loneliness in Japan report dissatisfaction with their family life or employment situation and two thirds say the same about their financial situation. Higher shares in Japan than in the U.S. or U.K. say their loneliness has had a negative impact on their job and their mental health. Many people reporting loneliness in Japan are younger — nearly six in ten are less than 50 years old, compared to 42 percent who don’t report loneliness. People in Japan experiencing loneliness are also much more likely to be dissatisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have with friends. More generally, large majorities in Japan think the Japanese concepts of Hikikomori and Kodokishi are serious problems.

Key Findings: Section 1: Characteristics And Experiences Of Those Who Report Often Feeling Lonely Or Socially Isolated

Prevalence of Loneliness and Social Isolation

Consequences of loneliness: Many Americans who always or often feel lonely say it affects their physical and mental health, relationships and work, per @KaiserFamFound survey w/@Economist

More than a fifth of adults in the U.S. (22 percent) and the U.K. (23 percent) say they often or always feel lonely, feel that they lack companionship, feel left out, or feel isolated from others, about twice the share in Japan (nine percent), referred to here as those reporting loneliness or social isolation. Not everyone experiences loneliness and social isolation the same way and some do not see it as a problem for them; however, most of those reporting loneliness across the U.S., the U.K., and Japan do. About one in twenty across countries say their loneliness is a “major” problem for them. In the U.S. and the U.K. there are more saying it is a minor problem or not really a problem for them, whereas in Japan, most people who report feeling lonely say it is a major problem for them.

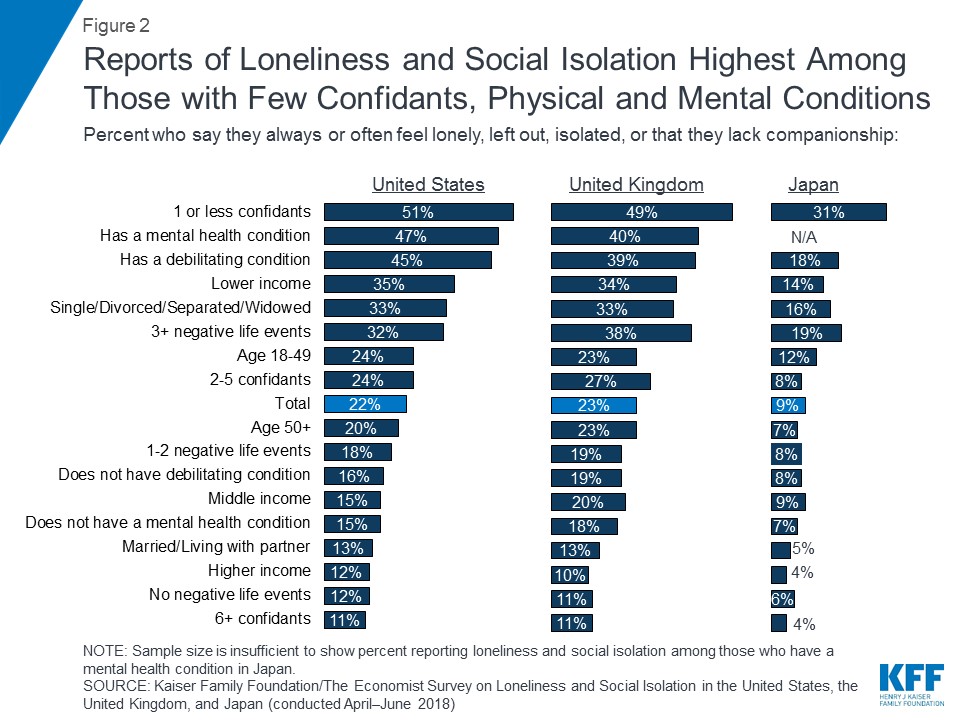

There are considerable differences in the share reporting loneliness or social isolation across a number of different demographics and life circumstances. The groups of people who are most likely to report being lonely or socially isolated include people who say they have few confidants, have mental health conditions, have a debilitating chronic illness or disability, are lower income, and are single, divorced, widowed, or separated. Each of these is discussed in more depth throughout this section.

Personal Characteristics of Adults Reporting Loneliness

Looked at another way, comparing the demographic profiles of those who report loneliness and those who do not can provide insights into the circumstances of those experiencing loneliness. For example, while loneliness is often thought of as a problem mainly affecting the elderly, majorities of people reporting loneliness across countries are younger than 50. In addition, those who report loneliness or social isolation are more likely than others to report lower incomes and not being married.

| Table 1: Demographics of those reporting loneliness | ||||||

| United States | United Kingdom | Japan | ||||

| Lonely | Not Lonely | Lonely | Not Lonely | Lonely | Not Lonely | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18-49 NET | 59% | 52% | 56% | 55% | 57% | 42% |

| 18-29 | 24 | 21 | 25 | 21 | 19 | 12 |

| 30-49 | 35 | 31 | 30 | 34 | 37 | 30 |

| 50+ NET | 41 | 48 | 44 | 45 | 43 | 58 |

| 50-64 | 25 | 26 | 19 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| 65+ | 16 | 21 | 25 | 22 | 21 | 36 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 44 | 50 | 45 | 50 | 54 | 51 |

| Female | 56 | 50 | 55 | 50 | 46 | 49 |

| Income | ||||||

| Lower Income | 58 | 31 | 49 | 29 | 47 | 30 |

| Middle Income | 21 | 34 | 18 | 21 | 29 | 31 |

| Higher income | 11 | 25 | 10 | 28 | 11 | 26 |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less/secondary or less | 47 | 37 | 35 | 30 | 63 | 62 |

| Some college/ post-secondary/junior college | 35 | 30 | 41 | 39 | 14 | 15 |

| College/university or more | 17 | 33 | 21 | 31 | 19 | 20 |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed full time | 33 | 49 | 25 | 43 | 35 | 46 |

| Employed part time | 13 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 14 |

| Unemployed (NET) | 14 | 4 | 14 | 5 | 22 | 11 |

| Other (NET) | 40 | 31 | 47 | 36 | 25 | 29 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single, that is never married | 32 | 23 | 32 | 23 | 42 | 19 |

| Single, living with a partner | 7 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 2 |

| Married | 22 | 48 | 22 | 43 | 30 | 60 |

| Divorced/Separated | 26 | 10 | 23 | 11 | 14 | 8 |

| Widowed | 11 | 7 | 14 | 8 | 12 | 10 |

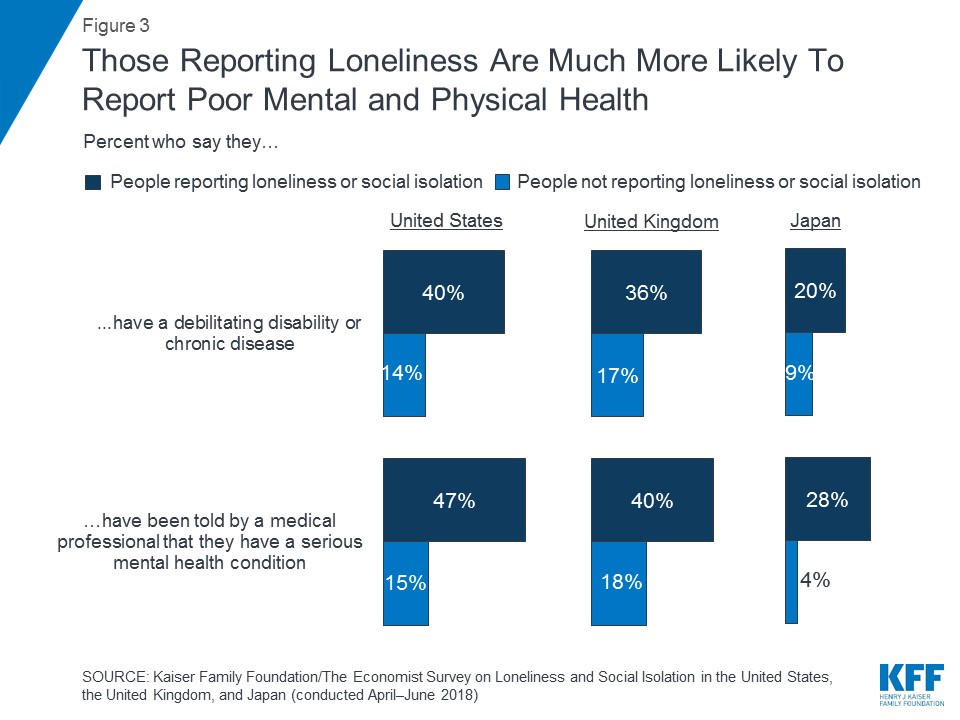

Reports of physical and mental health conditions are much more common among those experiencing loneliness than others. For example, across the three countries, people reporting loneliness are at least two times as likely as others to report having a debilitating disability or chronic disease that keeps them from fully participating in daily activities or to say they have been told by a medical professional that they have a serious mental health condition. And, while loneliness and social isolation may be perceived to be more often associated with mental health issues, those experiencing loneliness are almost as likely to report debilitating disabilities or chronic diseases as they are to report having a serious mental health condition.

Reported Causes of Loneliness and Negative Life Events

Loneliness appears to occur in parallel with reports of real life problems and circumstances. Across countries, about six in ten say there is a specific cause of their loneliness, but when asked what the specific cause is, the responses vary considerably. More than one in ten say the death of a significant other, parent, or other person caused their feelings of loneliness, while others say physical health problems (12 percent in U.S., eight percent in the U.K. and in Japan). Fewer say things like divorce, being away from family, or mental health problems are the specific causes of loneliness.

Some negative life events may exacerbate or put people at risk for feelings of loneliness and the findings show that loneliness is associated with real life challenges. For example, compared to others, people who report feeling lonely are much more likely to say they have experienced a negative change in financial status, a change in living situation, a serious injury or illness personally, or loss of a job in the past two years.

| Table 2: Reports of Negative Life Events | ||||||

| United States | United Kingdom | Japan | ||||

| Percent who say that in the past two years, they have experienced … | Lonely | Not Lonely | Lonely | Not Lonely | Lonely | Not Lonely |

| The death of a close family member or friend | 59% | 50% | 53% | 45% | 34% | 36% |

| A change in living situation | 46 | 34 | 42 | 29 | 38 | 28 |

| A negative change in financial status | 47 | 22 | 41 | 22 | 39 | 18 |

| A serious illness or injury in their family | 47 | 42 | 39 | 32 | 21 | 19 |

| A serious illness or injury themselves | 37 | 18 | 36 | 18 | 28 | 14 |

| A loss of a job | 27 | 16 | 17 | 11 | 28 | 9 |

| A death of a spouse or partner | 11 | 4 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Marital separation or divorce | 12 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Yes to any of the above | 91 | 81 | 89 | 75 | 79 | 67 |

Roughly half of those in the U.S. and the U.K. and two-thirds of those in Japan say they have felt lonely or isolated from those around them for at least three years. In Japan, more than a third (35 percent) say they have felt isolated or lonely for more than 10 years, compared to a fifth of those in the U.S. (22 percent) or the U.K. (20 percent).

Impacts of Loneliness and Social Isolation

Substantial shares across the three countries report that loneliness has had a negative impact on their lives. In Japan, majorities say loneliness has had a negative impact on their mental health (75 percent), physical health (63 percent), and personal relationships (59 percent), and nearly half say it’s had a negative impact on their ability to do their job (47 percent). In the U.S. and U.K., many say their loneliness has had a negative impact on their mental health (58 percent and 60 percent, respectively) and about half say it’s had a negative impact on their personal relationships (49 percent and 55 percent) and their physical health (55 percent and 49 percent). In terms of their ability to do their job, about a third in the U.S. and the U.K. say their loneliness has had a negative impact.

Likely stemming in part from the relatively high reports of mental health issues and negative mental health impacts of loneliness, about three in ten people experiencing loneliness in each country say it has led them to think about harming themselves – 31 percent in U.S., 30 percent in U.K., and 33 percent in Japan. Fewer say it has led them to think about committing a violent act – 15 percent in the U.S., 9 percent in the U.K., and 17 percent in Japan.

In addition to the specific impacts of loneliness, those reporting loneliness or isolation are much more likely to express general dissatisfaction with a number of different life domains, particularly when it comes to personal finances or employment, but also in housing and family life.

Social Interactions and Loneliness

Across countries, people experiencing loneliness are much more likely than others to say they have “just a few” or “no” people nearby they can rely on for help or support.

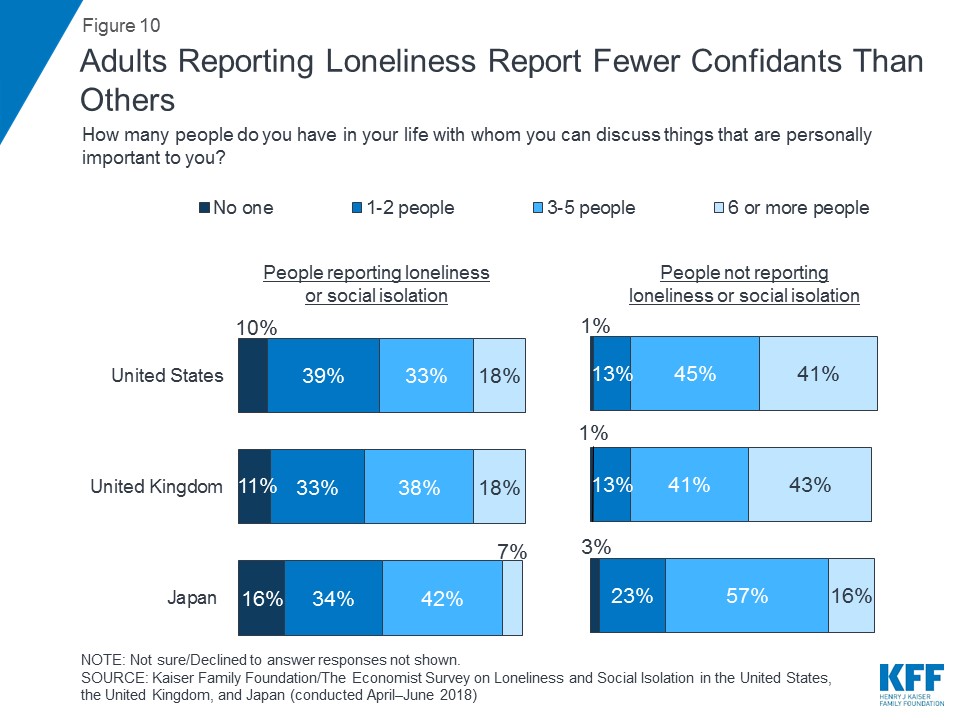

Specifically when it comes to the number of confidants people have with whom they can discuss personal matters, those who report feelings of loneliness and social isolation report having fewer confidants than others. For example, in the U.K., 11 percent of adults who report feeling lonely or socially isolated say they have no one with whom they can discuss things that are personally important to them and another 33 percent say they have one or two confidants, compared with 1 and 13 percent for others in the U.K.

And, more generally, across the three countries, those reporting loneliness are more likely to be dissatisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have with neighbors, family members and friends.

While some experiencing loneliness may be dissatisfied with the number of meaningful connections they have or have few confidants, many (roughly half or more) in the U.S. and the U.K. report talking to family or friends at least a few times a week either in person or over the phone. In Japan, it appears to be much less common to talk with family members frequently and roughly a fifth of those experiencing loneliness say they are in contact with family members in person or over the phone at least a few times a week. In each country, those who are lonely generally report communicating with friends and family less frequently than those who don’t report loneliness.

| Table 3: Frequency of Communication With Family and Friends | ||||||

| United States | United Kingdom | Japan | ||||

| Lonely | Not Lonely | Lonely | Not lonely | Lonely | Not lonely | |

| Talk to family members at least a few times a week… | ||||||

| …in person | 48% | 59% | 59% | 69% | 17% | 27% |

| …over the phone | 57 | 71 | 66 | 75 | 19 | 28 |

| …through email, text, or social media | 46 | 62 | 50 | 62 | 20 | 28 |

| Talk to friends at least a few times a week… | ||||||

| …in person | 57 | 74 | 60 | 73 | 25 | 27 |

| …over the phone | 57 | 62 | 48 | 58 | 13 | 23 |

| …through email, text, or social media | 61 | 66 | 54 | 66 | 34 | 34 |

Coping with Loneliness

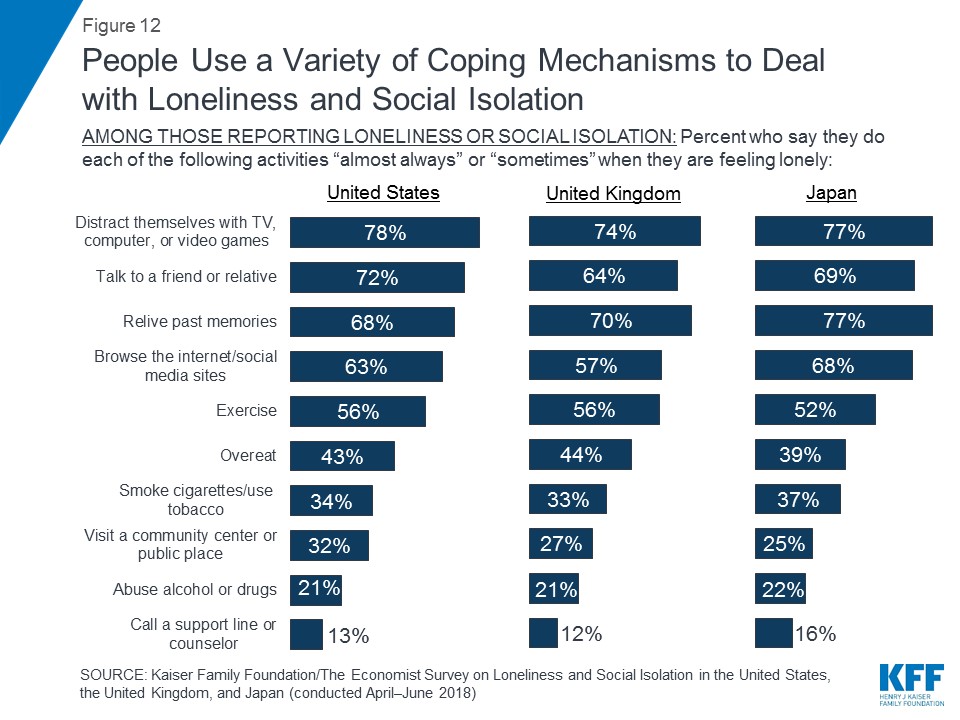

There are a number of different ways people may cope with loneliness, some more positive than others. Across countries, the most commonly reported coping mechanisms were distracting oneself with television, or computer or video games and reliving memories from the past, with about seven in ten or more saying they almost always or sometimes do these things when they feel lonely. Majorities report talking to a friend or relative, browsing the internet or social media sites or exercising. On the more negative side, across countries, four in ten say they overeat at least sometimes when feeling lonely, a third or more say they at least sometimes smoke cigarettes or use other tobacco products when feeling lonely, and two in ten say they at least sometimes abuse alcohol or drugs.

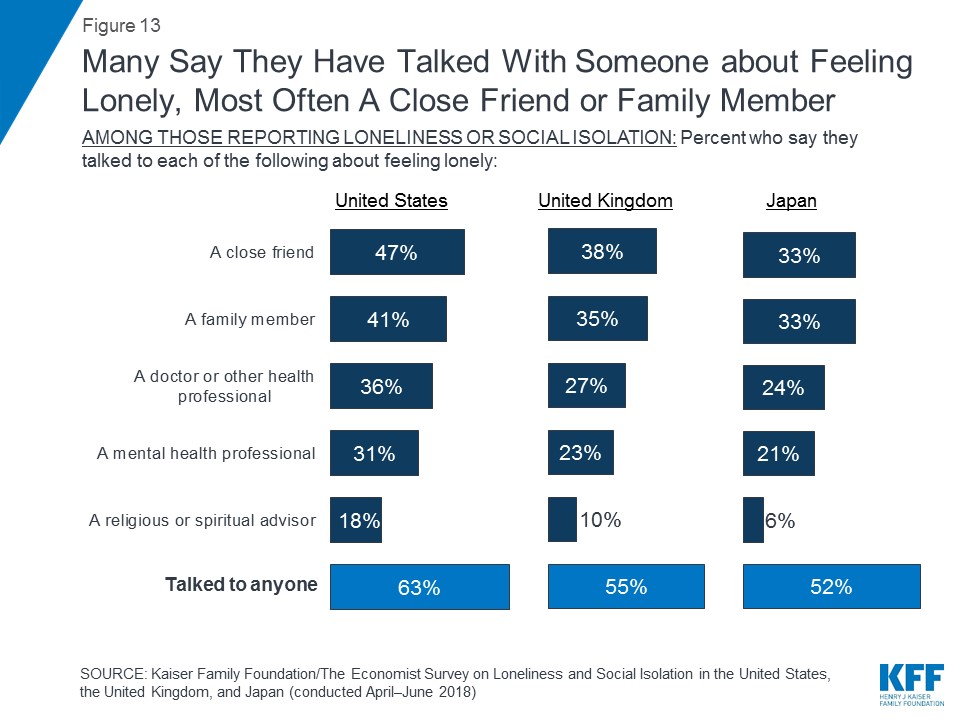

Across countries, majorities say they have talked to someone about their feelings of loneliness, but still others say they haven’t talked to anyone about it. Most commonly, they report talking to a close friend or family member, but some report talking to a doctor or other health professional, a mental health professional, or a religious or spiritual advisor.

Key Findings: Section 2: The Public’s Perceptions Of Loneliness And Social Isolation

Awareness and Views of the Issue

Across the U.S., the U.K., and Japan, majorities say they have heard “a lot” or “some” about the issue of loneliness and social isolation in their country. Not surprisingly given recent efforts by the U.K. government to address the issue, visibility is highest in the U.K. with two-thirds (67 percent) saying they’ve heard at least something about it, followed by 58 percent in Japan and 51 percent in the U.S. In the U.K., where a new minister for loneliness was appointed earlier this year, three in ten say they have heard or read “a lot” or “some” about recent efforts by the British government to address loneliness in the U.K. Another third say they’ve heard or read “only a little” and another third say they’ve heard “nothing at all.”

Who do people think of as being lonely? The most frequent answer is older people, with nearly three quarters of people in the U.K. (73 percent) and about half in the U.S. (49 percent) and Japan (46 percent) volunteering this group in an open-ended question. About four in ten people in Japan (43 percent) say when they think about people in Japan who are lonely, they think of people who live alone or are introverts, and nearly a fifth in the U.K. and the U.S. say the same. Additionally, about a fifth of adults in the U.S. and U.K. say they think of children, teenagers or young adults when they think of people who are lonely, compared to just six percent in Japan.

Across countries, views vary as to whether loneliness is more of a public health problem or more of an individual problem. In the U.K., and to a lesser extent Japan, more say it is more of a public health problem than say it is more of an individual problem (66 percent vs. 27 percent in the U.K. and 52 percent vs. 41 percent in Japan), whereas Americans are divided (47 percent vs. 45 percent).

Japan has unique terms for two specific conditions related to loneliness. One is Hikikomori, or the acute social withdrawal of adolescents and young adults, and the other is Kodokishi, which refers to the concept of dying alone. In Japan, eight in ten or more say that these are very or somewhat serious problems. Those reporting loneliness in Japan are more likely than others to say Hikikomori and Kodokishi are “very” serious problems (43 percent vs. 31 percent and 60 percent vs. 40 percent, respectively).

Across countries, large majorities of people say individuals and families should play a major role in helping to reduce loneliness and social isolation in society today. However, just about a quarter of Americans (27 percent) say the government should play a major role, whereas six in ten people in the U.K. (63 percent) and Japan (62 percent) see a major role for the government. Instead, more Americans see a major role for churches and other religious institutions (61 percent) than in the U.K. (42 percent) and Japan (16 percent).

Perceptions of Reasons for Loneliness

When asked how much responsibility individuals bear for their own loneliness, over half of Americans (54 percent) and seven in ten British people (72 percent) say a person’s loneliness is usually due to factors and circumstances beyond their control, rather than saying they mostly have themselves to blame. The Japanese are more divided with similar shares saying lonely people mostly have themselves to blame and saying loneliness is due to factors out of their control (44 percent and 42 percent, respectively). However, among people experiencing loneliness in Japan, 57 percent say a person’s loneliness is due to factors beyond their control.

There are a number of different societal factors that may play a role in loneliness and social isolation and views of these potential reasons for loneliness differ across the U.S., U.K. and Japan. In one place of agreement, majorities across countries say that long-term unemployment is a major reason why people are lonely or socially isolated in their country. Much of the public in the U.S. and U.K. point to increased use of technology and adults playing less of a role in helping aging parents as major reasons, whereas fewer in Japan say the same. In addition, residents of the U.K. are more likely than those in the U.S. to say people moving away from where they grew up is a major reason for loneliness. Residents of the U.K. are also more likely than people in the U.S. or Japan to say cuts in government social programs is a major reason for loneliness. Views are similar regardless of whether or not someone reports personally experiencing loneliness or social isolation themselves.

One striking difference across countries is in the shares saying “increased use of technology” is a major reason people are lonely or socially isolated – from 58 percent in the U.S., to 50 percent in the U.K. and 26 percent in Japan. When including “minor” reason, the shares in the U.S. (84 percent) and U.K. (86 percent) are similar, but in Japan, it is just over half (56 percent).

Social Media and Loneliness

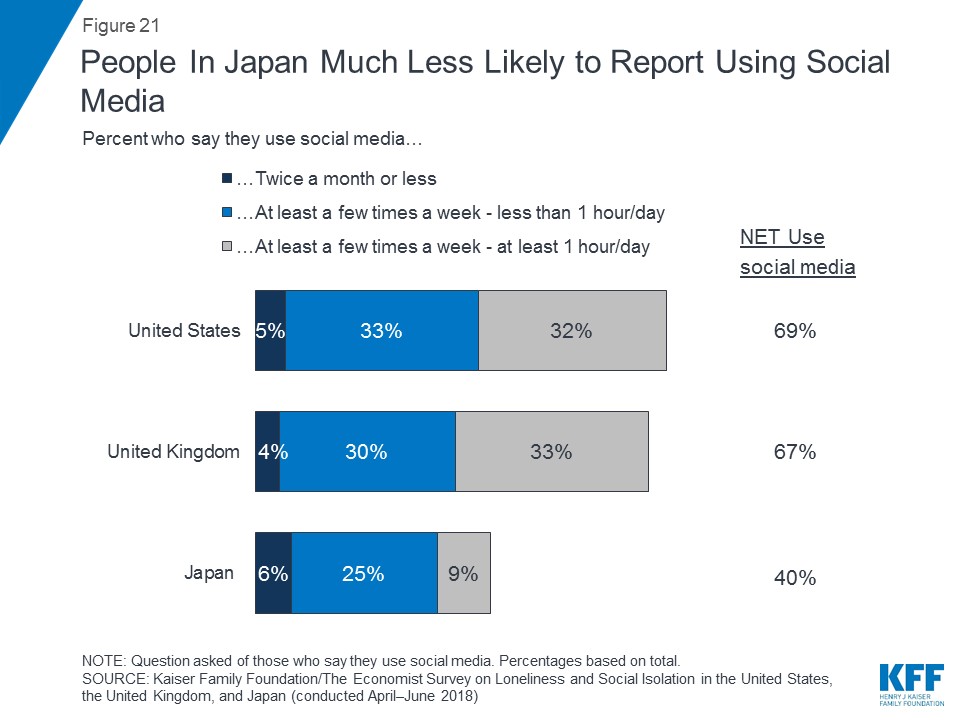

Social media consumption varies across the three countries from four in ten in Japan saying they use it, including 23 percent who say they use it every day, to 69 percent in the U.S. and 67 percent in the U.K., including nearly half in the U.S. and U.K. who say they use it every day, some of them for hours a day.

While most Americans view increased technology use as a major reason why people feel lonely/isolated, those who always or often feel that way are divided on social media’s impact

For the most part, people who report being socially isolated or lonely in each country are not more likely than their peers to report using social media. However, those experiencing loneliness in the U.S. and Japan are more likely than others to say they use social media for 2 hours or more per day (22 percent vs. 12 percent in the U.S. and 11 percent vs. 4 percent in Japan).

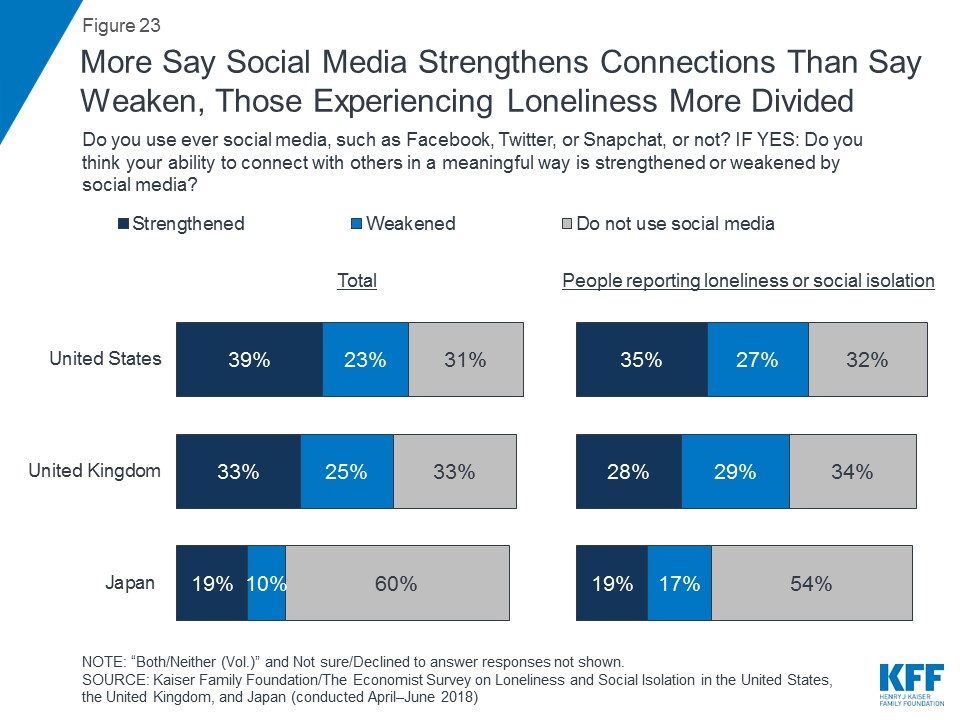

In each country, more of the public overall says that they think their ability to connect with others in a meaningful way is strengthened by social media than say it is weakened. However, those who are experiencing loneliness are more divided.

On the question of whether one’s personal feelings of loneliness are made better or worse by social media, roughly similar shares of those experiencing loneliness in the U.S., U.K., and Japan say better or say worse.

Most people in the U.S. and U.K. say that after interacting with a friend online they’re as satisfied as they would be after interacting with a friend on the phone. Still more say they feel less satisfied with this type of interaction than say they leave more satisfied. In Japan, views are more mixed with similar shares saying they they’re less satisfied (32 percent) as saying they’re equally satisfied (31 percent) when interacting via phone compared to online. However, when comparing an online interaction to an in-person interaction, across countries about four in ten say they’re less satisfied after interacting online, while fewer say they’re equally satisfied or more satisfied.

More broadly, across countries, more say technology in general has made it harder to spend time with friends and family in person than say it has made it easier. A third or more say it hasn’t made a difference. People experiencing loneliness or social isolation in the U.K. or Japan are more likely than others to say technology has made it harder to spend time with family and friends. In the U.S., shares are similar for those who are experiencing loneliness and those who aren’t.

Methodology

The Kaiser Family Foundation/The Economist Loneliness and Social Isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An International Survey was conducted among nationally representative random digit dial (RDD) telephone (landline and cell phone) samples of adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States (including Alaska and Hawaii), in the United Kingdom, and Japan (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). SSRS carried out the sampling and weighting for all countries, and conducted computer-assisted telephone interviews for the U.S. sample. Interviews in the U.K. were carried out by GDCC and interviews in Japan were carried out by Adams Communications, under the direction of SSRS. RDD landline and cell phone samples were provided by Marketing Systems Group (MSG) for the U.S., Sample Solutions Europe (SSE) for the U.K., and Adams Communications for Japan. Interview languages, field dates, and sample sizes for each country are shown in the table below. Teams from The Economist and the Kaiser Family Foundation worked together to develop the survey questionnaire and analyze the data. The Kaiser Family Foundation paid for the fieldwork costs associated with the survey. Each organization is responsible for its content.

| Country | Field Dates | Language(s) | Total sample size (unweighted) | Cell phone sample | Landline sample |

| United States | April 18-May 23, 2018 | English and Spanish | 1,003 | 720 | 283 |

| United Kingdom | April 18-May 23, 2018 | English | 1,002 | 503 | 499 |

| Japan | April 18-June 4, 2018 | Japanese | 1,000 | 635 | 365 |

Due to the multi-national design, the questionnaire was tested and translated in multiple stages. The first step involved a live-interview telephone pretest of the English questionnaire with U.S. and U.K. respondents. Revisions to the English questionnaire were made following the pretest in order to shorten the survey instrument and improve respondent comprehension of questions. Following the English pretest, the questionnaire was translated into Spanish (for interviewing in the U.S.) and Japanese. Translations were reviewed by a team of professional translators. A second pretest was conducted in Japan after which further revisions were made to the questionnaire.

In order to better understand the views and experiences of those personally experiencing loneliness or social isolation, the full sample includes additional interviews with people who say they “always” or “often” feel lonely, that they lack companionship, isolated, or left out (commonly referred to as an “oversample”). For brevity, throughout this report, this group is referred to as “lonely.” In order to complete at least 200 interviews in each country with adults meeting this definition, some interviews were only completed if the individual met the loneliness screening criteria. In the U.S., the SSRS Omnibus (weekly, RDD landline and cellular phone surveys of the general public) was used to identify respondents who qualified as lonely and then those individuals were re-contacted and re-screened for this survey. A total of 86 interviews in the U.S. were conducted with these pre-recruited individuals.

In each country, to randomly select a household member for the landline samples, respondents were selected by asking for the adult male or female currently at home who had the most recent birthday based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the adult of the opposite gender who had the most recent birthday. For the cell phone samples, interviews were conducted with the adult who answered the phone.

Multi-stage weighting processes were applied separately for each country to ensure an accurate representation of each country’s national adult population. The first stage of weighting involved corrections to account for the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection as well as accounting for oversampling of lonely respondents, as well as non-response adjustment. The second weighting stage was designed to make demographic adjustments to the sample to match national population estimates. In the U.S., the sample was balanced to match known adult-population parameters using data from the Census Bureau’s 2016 American Community Survey (ACS) and phone use parameters from the January-June 2017 early release estimates for the National Health Interview Survey. The weighting parameters used for the U.S. were age, gender, education, race/ethnicity, census region, and telephone use. Population parameters for the U.K. were from the mid-2014 U.K. Census Update and included gender, age, educational attainment, and region as well as phone status (cell phone only or reachable by landline) from Q1 2015 Communications Market Report. Population parameters from Japan were from the Population Census of Japan 2010 and included gender, age, educational attainment, marital status and region. In the final weighting stage, the lonely oversample was weighted to reflect its actual share in the adult population for each country. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting.

At the end of the field period, SSRS completed several data validation processes on the international data that included: internal validity checks, testing for straightlining, and analyzing paradata (interviewer workload, interview length, interview time, and overlap of interviews). The Kaiser Family Foundation, along with SSRS, also conducted a percent-match procedure to identify cases that share a high-percentage of identical responses to a large set of questions. This extra validation measure allows for detection of possible duplicate data, whether as a result of intentional falsification, or due to errors in data-processing.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for each country sample is shown in the table below. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error will be higher; sample sizes and margins of sampling error for subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Country | Total sample size (unweighted) | M.O.S.E |

| United States | ||

| Total | 1,003 | ±3 percentage points |

| Total reporting loneliness or social isolation | 276 | ±7 percentage points |

| United Kingdom | ||

| Total | 1,002 | ±4 percentage points |

| Total reporting loneliness or social isolation | 261 | ±4 percentage points |

| Japan | ||

| Total | 1,000 | ±4 percentage points |

| Total reporting loneliness or social isolation | 200 | ±9 percentage points |