States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019

Executive Summary

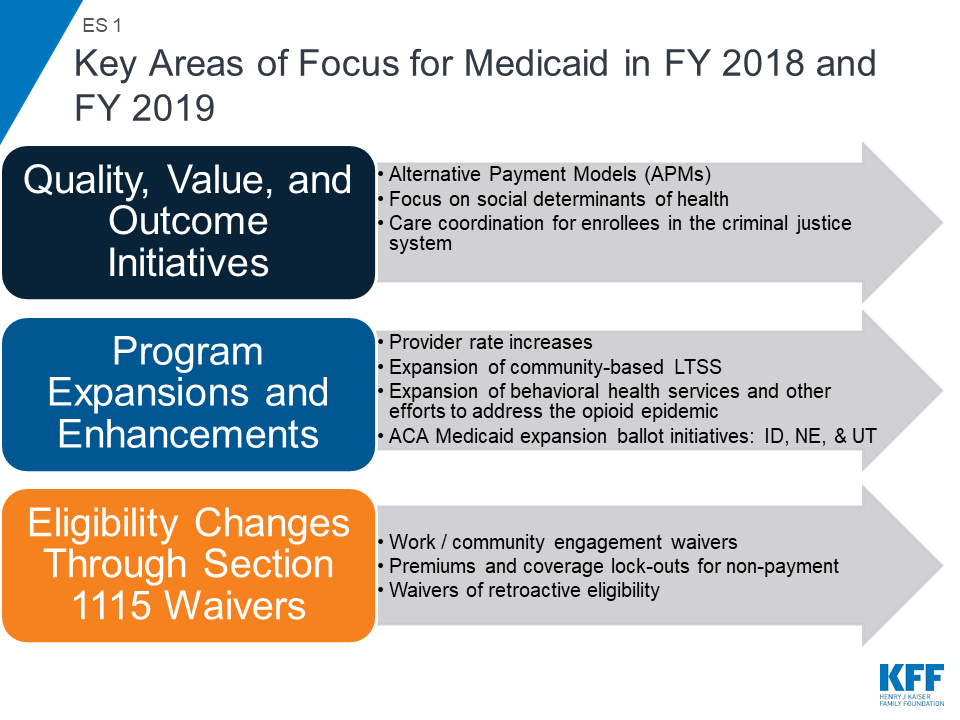

Medicaid covers one in five Americans, accounts for one in six dollars spent on health care in the United States, and makes up more than half of all spending on long-term services and supports. Medicaid is a state budget driver as well as the largest source of federal revenue to states. The program is constantly evolving in response to federal policy changes, the economy, and state budget and policy priorities. As states began state fiscal year (FY) 2019, the economy in most states was stable or improving and 36 states faced upcoming gubernatorial elections. With fewer budget pressures, a number of states reported expansions or enhancements to provider rates and benefits (including expansions for community-based long-term services and supports (LTSS) and behavioral health services). In addition, ballot initiatives in three states could result in adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. States also continue to focus on improvements in outcomes and value through delivery system changes and managed care requirements. In response to policy directions promoted by the Trump administration, an increasing number of states are pursuing demonstration waivers that include work requirements and the elimination or restriction of retroactive eligibility — policies that could result in enrollment declines (ES 1).

This report provides an in-depth examination of the changes taking place in Medicaid programs across the country. The findings are drawn from the 18th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). This report highlights certain policies in place in state Medicaid programs in FY 2018 and policy changes implemented or planned for FY 2019. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis but a separate survey was fielded and results will be released in another report. Key findings include the following:

A growing number of states are pursuing federal waivers to add work requirements in Medicaid, impose new or increased premiums and lock-out periods, and waive retroactive eligibility

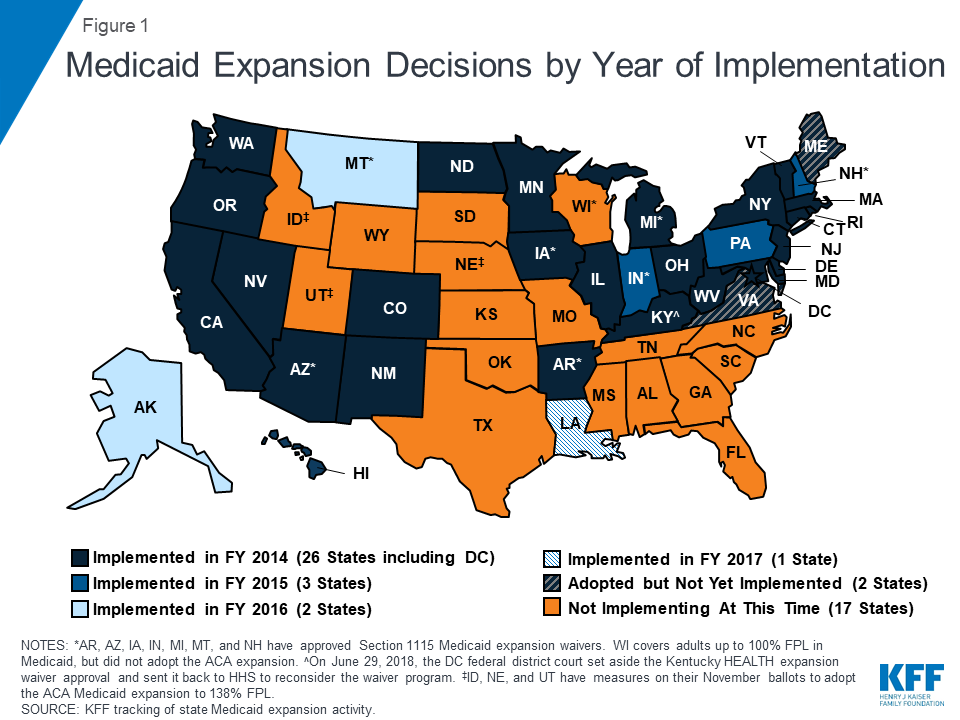

A growing number of states are implementing or planning Section 1115 waivers with policies that have or could result in enrollment declines, while three states (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah) could adopt the ACA Medicaid expansion through ballot initiatives. Policies that have or are likely to result in enrollment declines are counted as restrictions in this report. Eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2018 (by six states) or planned for implementation in FY 2019 (in 11 states) generally target broad Medicaid populations, including parents/caretakers and expansion adults. These changes are primarily occurring through Section 1115 waiver demonstration authority because they are not allowed under current law. Restrictions for FY 2018 or FY 2019 include eight states implementing or planning to implement work or community engagement requirements as a condition of Medicaid eligibility, eight states eliminating or restricting retroactive eligibility, and three states implementing or proposing lock-out periods for non-payment of premiums, failure to complete redetermination, and/or failure to timely report changes affecting eligibility. In contrast, with the exception of planned implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in Maine and Virginia in FY 2019, most Medicaid eligibility expansions for FY 2018 or FY 2019 are narrow and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. Most states are working with corrections agencies and with local jails to facilitate Medicaid enrollment prior to release and the majority of states do not terminate Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated.

What to Watch: Three states have proposals to adopt the Medicaid expansion on the November 2018 ballot (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah) and many states have Section 1115 waivers pending or under development that could be implemented after FY 2019 and would impact eligibility, if approved by CMS.

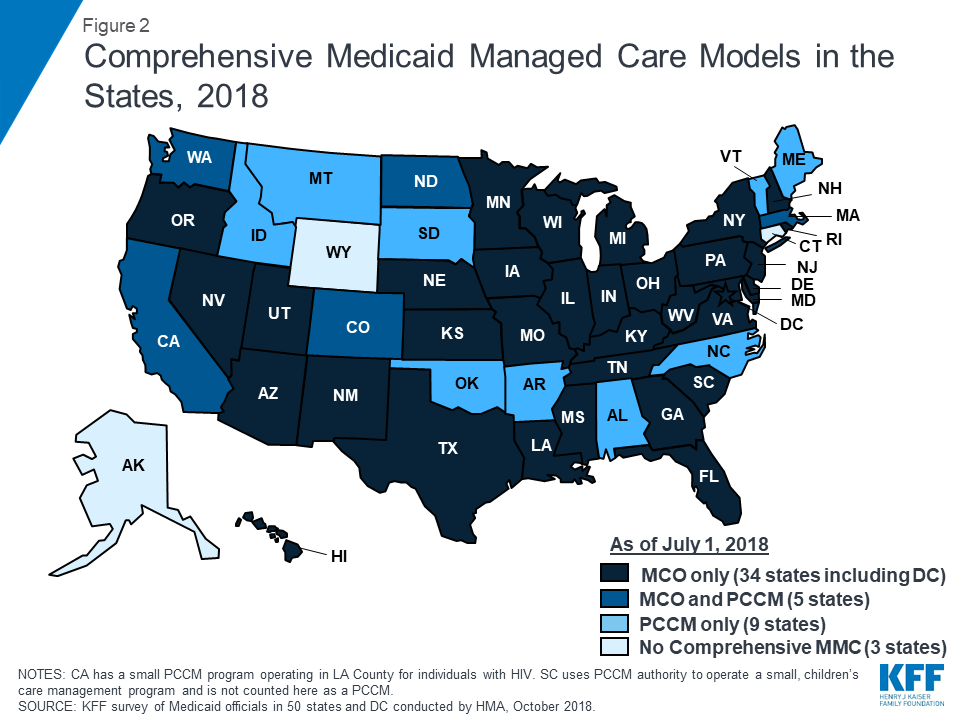

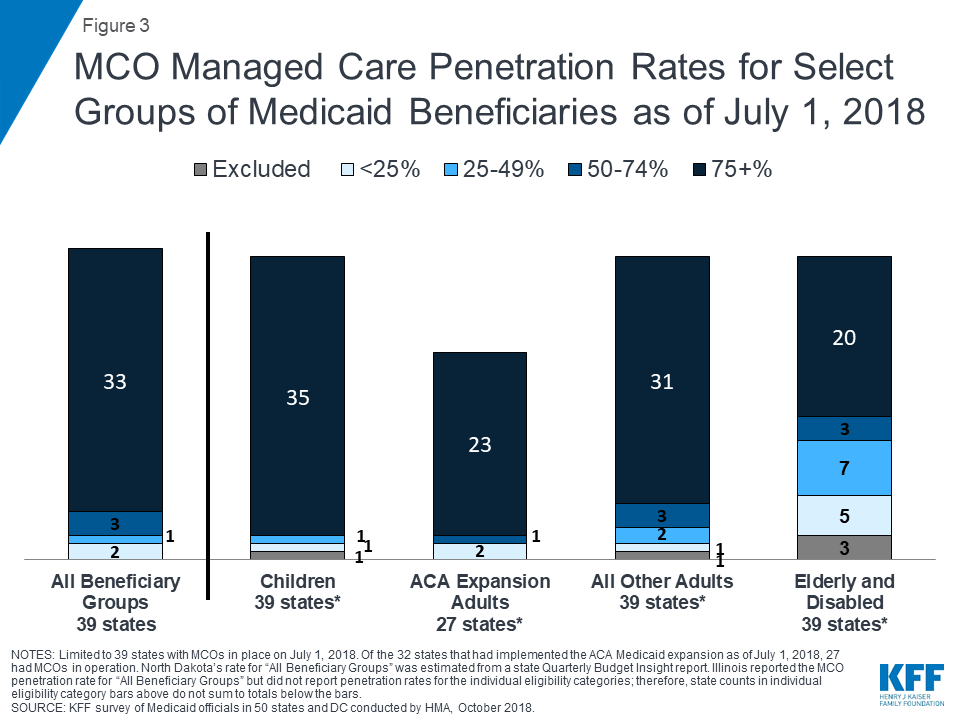

Risk-based managed care continues to be the predominant delivery system for Medicaid services, and states are focused on implementing alternative payment models and improving quality within MCOs. Among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2018. Although many states still carve-out behavioral health services from MCO contracts, movement to carve-in these services continues. Nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds and an increasing number of states (23 in FY 2018) set a target percentage of MCO provider payments that must be in alternative payment models (APMs).

What to Watch: Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. States continue to focus on improving value, quality, and outcomes through managed care arrangements. CMS has announced plans to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations for public comment later this fall.

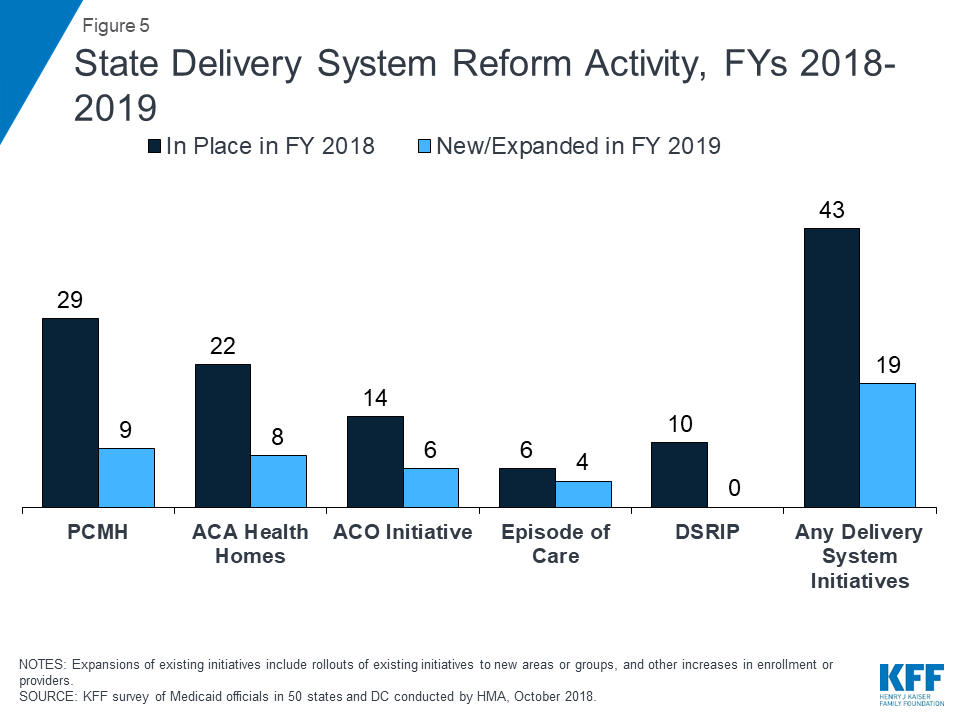

States are working to address social determinants of health both within and outside of MCO contract requirements. Medicaid programs have been expanding their use of other service delivery and payment reform models to achieve better outcomes and lower costs. Forty-three states had one or more delivery system or payment reform initiatives in place in FY 2018 (e.g., patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), ACA Health Homes, accountable care organizations (ACOs), episode of care payments, or delivery system reform incentive programs (DSRIPs)).

What to Watch: About one-third of the states reported a wide variety of initiatives implemented in FY 2018 or planned for FY 2019 that address the social determinants of health (SDOH) outside of managed care and more than one-third reported collecting or plans to collect SDOH data from various sources including screenings and assessments, data collected for other state programs, claims data, beneficiary surveys, or as part of a care management or home visiting program.

Nearly all states in FY 2018 (46 states) and FY 2019 (48 states) are employing one or more strategies to expand the number of people served in home and community-based settings. Almost all states continue to report using home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers and/or state plan options (i.e., 1915(c), 1115, 1915(i), and 1915(k)) to serve more individuals in the community. As of July 1, 2018, 24 states covered LTSS through one or more capitated managed care arrangements (“MLTSS”). Pennsylvania introduced MLTSS in FY 2018, with a plan to phase-in statewide over time. Virginia ended its Financial Alignment Demonstration (FAD) but adopted statewide MLTSS for a broader population, including dual eligible individuals. To address challenges in finding and retaining LTSS direct care workers, a number of states reported wage increases for these workers in FY 2018 and/or FY 2019.

What to Watch: Housing-related supports remain an important part of state LTSS benefits, even as Money Follows the Person (MFP) grant funds expire. While 30 states reported that they expect to continue to offer housing-related supports after MFP funds are exhausted, about half of states reported plans to discontinue at least some housing-related services or administrative functions when MFP ends.

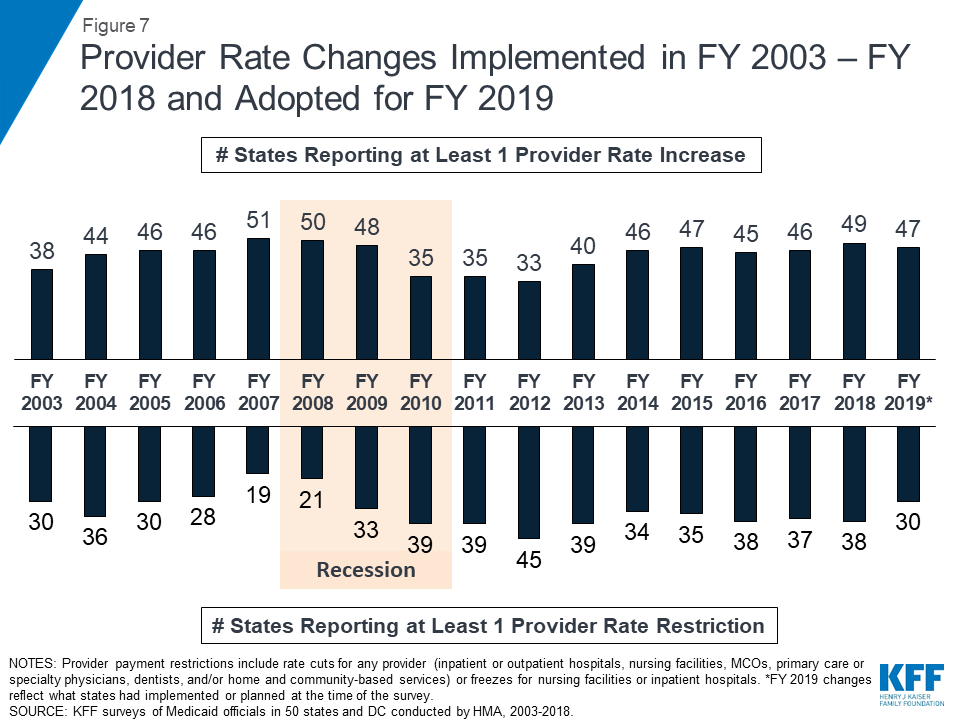

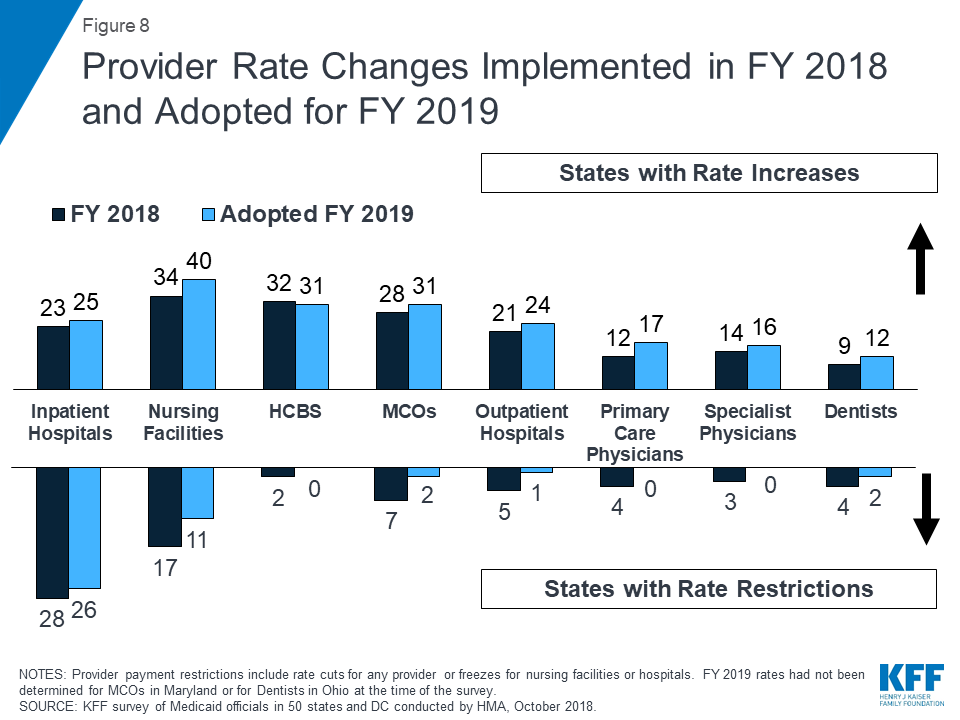

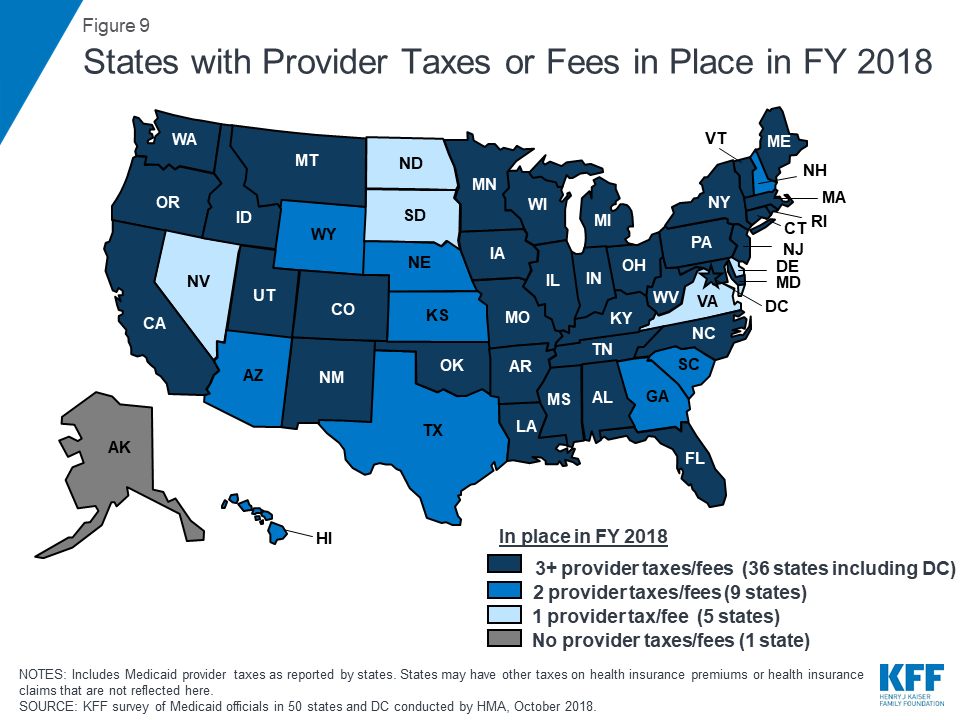

In FY 2018 and FY 2019, with favorable economic conditions in most states, more states made or are planning provider rate increases compared to restrictions, and there is little new activity around provider taxes. More rate increases relative to decreases holds true across major provider types, with the exception of inpatient hospitals (where inpatient hospital rate “restrictions” are primarily rate freezes that are counted as restrictions in this report). About half of MCO states (21 of 39) require MCO payments to some or all types of providers to follow percent or level changes in fee-for-service (FFS) rates. Twenty-seven states require minimum MCO payments (rate floors) for some provider types, and five states reported minimum MCO payment requirements for all types of Medicaid providers. All states except Alaska rely on provider taxes and fees to fund a portion of the non-federal share of the costs of Medicaid. Two states indicated plans for new provider taxes in FY 2019, including Virginia that plans a new hospital provider tax to finance state costs of the newly adopted Medicaid expansion.

What to Watch: As enrollees are predominantly in MCOs, the significance of changes in FFS payment rates is difficult to assess without a better understanding of how changes in FFS rates affect changes in MCO rates paid to providers. Twenty-nine states have at least one provider tax that is at or above 5.5% of net patient revenues (close to the maximum safe harbor threshold of 6%). Therefore, federal action to lower that threshold as proposed in the past would have financial implications for many states.

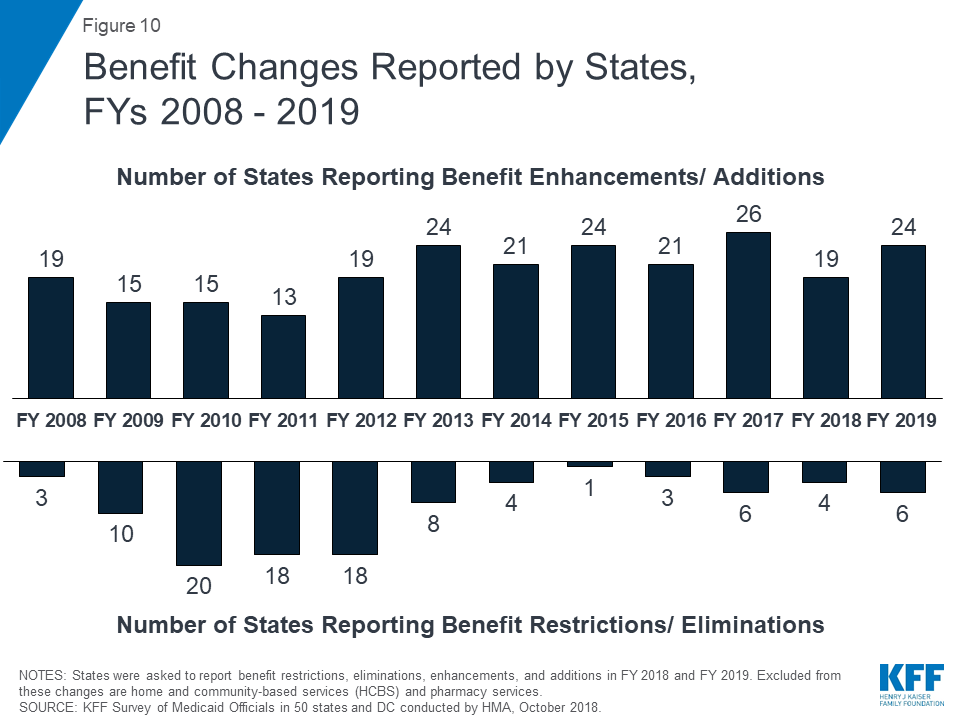

Positive economic conditions and state priorities resulted in a number of states increasing benefits, particularly for mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. A total of 19 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in FY 2018 and 24 states plan to add or enhance benefits in FY 2019. The most common benefit enhancements reported were for mental health/SUD services (including waiver of the IMD exclusion). A handful of states also reported expansions related to dental services, telemonitoring/telehealth, physical or occupational therapy services, and screening or home visiting services for pregnant women and/or children.

What to Watch: Medicaid continues to play an important role in addressing the opioid epidemic and more broadly in connecting Medicaid beneficiaries to behavioral health services. Going forward, it will be important to follow trends and innovations in how states use Medicaid to increase access to behavioral health services and contain the growth of the opioid and broader SUD crisis.

States continue to focus on cost containment efforts to address rising prescription drug costs and on pharmacy benefit management strategies to address the opioid crisis. Prescription drug costs continue to exert pressure on Medicaid spending, and most states identified specialty and high-cost drugs (individually or in general) as the most significant driver of these costs. Many states reported implementing or making changes to a wide variety of prescription drug cost containment initiatives in FY 2018 or FY 2019, especially initiatives to generate greater rebate revenue and implement new utilization controls (e.g., prior authorization requirements, step therapy, other clinical criteria, or dose optimization). Almost all MCO states generally carve the pharmacy benefit into managed care, and many MCO states are moving to align MCO pharmacy policies with FFS policies. In FY 2018, all states report implementing one or more FFS pharmacy management strategies targeted at opioid harm reduction, including quantity limits, clinical criteria claim system edits, step therapy, other prior authorization requirements, and requirements for Medicaid prescribers to check their states’ Prescription Drug Monitoring Program before prescribing opioids to a Medicaid patient. States continue to increase access to Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder, and 38 states reported coverage of methadone in FY 2018.

What to Watch: Several states noted the emerging cost challenge posed by gene therapies and immunotherapies like “CAR-T” (Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T cell) therapies,1 designated by CMS as covered outpatient drugs. While states are expanding coverage of MAT, many reported access challenges, especially in rural areas.

Challenges and Priorities FY 2019 and Beyond: Continuing to tackle the opioid epidemic is a key priority for states in FY 2019 and beyond. New federal legislation expected to be signed into law as this report was being finalized, the Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act, contains a number of provisions related to Medicaid’s role in helping states provide coverage and services to people who need SUD treatment,2 particularly those needing opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment. These provisions include the ability to use federal Medicaid funds for services in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs) for nonelderly adults for up to 30 days from October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2023; required coverage of all FDA-approved drugs for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) as well as counseling and behavioral therapy services from October 2020 through September 2025; required suspension of Medicaid eligibility for individuals under age 21 or former foster care youth up to age 26 while incarcerated, and restoration of coverage upon release; creation of new demonstrations to help states increase Medicaid SUD provider capacity; and tighter prescription drug oversight.

In addition, states reported a wide variety of other priorities for FY 2019 and beyond, including implementing managed care, payment, and delivery system reform initiatives; undertaking major information technology system procurements and upgrades; pursuing new Section 1115 demonstration waivers, and managing their Medicaid budgets. The trajectory of the economy, the direction of federal policies around Medicaid Section 1115 waivers, and the outcomes of state and federal elections in November 2018 will be factors that shape Medicaid in FY 2019 and beyond.

Report: Introduction

Medicaid now provides health insurance coverage to one in five Americans and accounts for nearly one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.3 The Medicaid program constantly evolves due to changes in federal and state policies, the economy, and other state budget and policy priorities. As of July 26, 2018, all states had enacted a new or revised budget for FY 2019 with only three states enacting a budget after the fiscal year began.4 ,5 This represented a significant improvement from the prior year when a number of states called special sessions in 2017 to complete their FY 2018 budgets and 11 states started FY 2018 without a fully enacted budget.6 A stable economy and improvements in state revenue growth resulted in surpluses in many states at the beginning of FY 2019 when this survey was conducted.7

Report findings are drawn from the 18th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). (Previous reports are archived here.8 ) This year’s KFF/HMA Medicaid budget survey was conducted from June through September 2018 via a survey sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2018 and then a follow-up telephone interview. An acronym glossary and the survey instrument are included as appendices to this report.

The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report; the counts of state policies or policy actions that are interspersed throughout this report include survey responses from the 51 “states” (including DC). All 50 states and DC completed surveys and participated in telephone interview discussions between July and September 2018.9 Given differences in the financing structure of their programs, the U.S. territories were not included in this analysis but a separate survey was fielded and results will be released in another report.

This report examines Medicaid policies in place or implemented in FY 2018, policy changes implemented at the beginning of FY 2019, and policy changes for which a definite decision has been made to implement in FY 2019 (which began for most states on July 1, 201810 ). Policies adopted for the upcoming year are occasionally delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems, or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS. Key findings of this survey, along with state-by-state tables, are included in the following sections of this report:

Report: Eligibility And Premiums

Key Section Findings

Since 2014, most major Medicaid eligibility policy changes have been related to adoption of the ACA Medicaid expansion. Thirty-two states have implemented the expansion to date and two additional states adopted the expansion in FY 2018 and plan to implement the policy in FY 2019 (Maine and Virginia). Other Medicaid eligibility expansions for FY 2018 or FY 2019 were narrow and targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. In contrast, eligibility restrictions implemented in FY 2018 (by six states) or planned for implementation in FY 2019 (in 11 states) generally target broader Medicaid populations including expansion adults and parents/caretakers. Policies that have or are likely to result in enrollment declines are counted as restrictions in this report. The vast majority of states implementing or planning eligibility policies that are counted as restrictions in FY 2018 or FY 2019 are doing so through Section 1115 waiver authority, whereas most states implementing or planning eligibility expansions are doing so through state plan amendment (SPA) authority.

What to watch:

- Three states have proposals to adopt the Medicaid expansion on the November 2018 ballot (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah).

- In FY 2019, eleven states are planning to implement Medicaid Section 1115 waivers with policies that would result in eligibility restrictions including the addition of work requirements and the elimination or limitation of retroactive eligibility. Some states indicated that significant administrative resources will be needed to implement these initiatives, including one-time costs such as systems modifications and ongoing annual costs such as increased staffing.

- Most states are working with corrections agencies and with local jails to facilitate Medicaid enrollment prior to release and the majority of states do not terminate Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated. The SUPPORT Act would be prohibit states from terminating Medicaid eligibility for an individual under age 21 or former foster care youth up to age 26 while incarcerated beginning in October 2019.

- Seven states reported planned changes related to new or increased premiums in FY 2019, six of which are through Section 1115 waivers.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 at the end of this section include additional details on eligibility, premium, and corrections-related policy changes in FY 2018 and FY 2019.

Changes to Eligibility Standards

Eligibility Restrictions

A growing number of states are pursuing Section 1115 waivers that include policies that would result in eligibility restrictions in FY 2018 and FY 2019 (Exhibit 1). Some of these policies are in response to January 2018 CMS guidance11 indicating the agency’s support for Section 1115 waiver proposals that would require certain Medicaid enrollees to meet a work requirement in order to maintain coverage. Policies that have or are likely to result in enrollment declines are counted as restrictions in this report.

| Exhibit 1: Eligibility Restrictions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |||

| SPA | 2 States | CT, NM | 0 States | |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 4 States | AR, IA, IN, UT | 11 States | AL*, FL*, IN, KY*^, MA, ME*, MI*, NH, NM*, OH*, SD* |

| *Indicates the Section 1115 Waiver has not yet been approved by CMS.^CMS’ approval of Kentucky’s waiver authorizing FY 2019 restrictions was set aside by a court order in June 2018 that also remanded the waiver to CMS for reconsideration regarding how the waiver would meet the medical assistance objectives of the Medicaid statute. | ||||

Six states reported implementing restrictions in FY 2018 and 11 states reported restrictions already implemented or planned for implementation in FY 2019 (Exhibit 1 and Table 1). This year’s survey reports changes that states plan to implement in FY 2019, even if the changes are in Section 1115 waiver proposals that are still pending approval12 at CMS. Waiver provisions that states plan to implement in FY 2020 or after are described later in the “Challenges and Priorities” section of this report.

Eight states reported implementing or plans to implement work requirements under Section 1115 waiver authority in FY 2018 or FY 2019 (Table 2).13 These policies generally require beneficiaries to verify their participation in approved activities, such as employment, job search, or job training programs, for a certain number of hours per week or month to receive health coverage or qualify for an exemption. Data show, however, that most Medicaid enrollees are already working or would qualify for exemptions from these requirements, yet these individuals would still need to navigate a reporting or exemption process to retain their Medicaid coverage. In this report, work requirement policies are counted based on the initial date of implementation rather than the date on which the first coverage terminations will occur.

- Three states have approved waivers to implement a work requirement, including one state (Arkansas) that implemented the policy in June of FY 2018 and two states (Indiana and New Hampshire) that plan to implement in FY 2019.

- Five additional states reported pending work requirement proposals that they plan to implement in FY 2019. Four of these states (Alabama, Maine, Ohio, and South Dakota) have proposals pending approval by CMS and one state (Kentucky) received approval for a work requirement waiver that was set aside by court order. That waiver is now back with CMS for reconsideration (see the Kentucky HEALTH waiver box below). Kentucky’s waiver is referred to as “pending” throughout the rest of this report.

Many of these states reported new administrative requirements or costs associated with implementation of work requirement policies, including those related to vendor contracts for call centers, systems modifications, increased state and local office staff, outreach to beneficiaries and providers, and increased MCO personnel costs.

Kentucky HEALTH Waiver

In January 2018, Kentucky received initial CMS approval for the Kentucky HEALTH Section 1115 waiver. The waiver included several provisions approved for the first time in Medicaid — a work requirement, monthly premiums up to 4% of income, and coverage lock-outs for failure to timely renew eligibility or timely report changes affecting eligibility — as well as heightened cost-sharing for non-emergency ER use, elimination of retroactive eligibility, and elimination of non-emergency medical transportation. A court order issued in Stewart v. Azar on June 29, 2018, however, set aside the CMS approval and remanded the waiver to CMS for reconsideration regarding how the Kentucky waiver would meet the medical assistance objectives of the Medicaid statute. At the time of the survey, CMS had completed an additional federal public comment period and the state was preparing for FY 2019 implementation, but the waiver remained under consideration at CMS.

Eight states indicated that they have eliminated or propose to eliminate or restrict retroactive eligibility for one or more groups in FY 2018 and FY 2019 (Table 2).14 In FY 2018, Arkansas limited retroactive eligibility from 90 to 30 days, Iowa eliminated retroactive eligibility for all groups other than children under age one and pregnant women (but restored retroactive eligibility for nursing facility residents in July 2018), and Utah eliminated retroactive eligibility for Primary Care Network (PCN) waiver adults. In FY 2019, five states (Florida, Kentucky, Maine, New Hampshire, and New Mexico) plan to eliminate retroactive eligibility or limit it to a single month for most enrollees.

Other examples of reported eligibility restrictions in FY 2018 or FY 2019 include:

- In FY 2018, as part of their HIP 2.0 waiver renewal (a waiver that already included other eligibility restrictions), Indiana15 imposed a three-month lock-out from coverage on expansion adults who fail to comply with redetermination. Enrollees who do not verify eligibility at renewal are disenrolled but can re-enroll without a new application if they provide necessary documentation within 90 days. After 90 days, individuals are subject to a three-month lock-out before they can re-enroll.16

- In FY 2019, New Mexico plans to implement proposals included in a pending waiver application to disenroll and lock-out expansion adults who do not pay required Medicaid premiums and a “reasonable promptness” waiver that would delay coverage until the first day of the first month following receipt of required premiums.

- In FY 2019, Maine17 plans to implement (if their pending waiver is approved) several restrictions on their traditional Medicaid populations in addition to their planned waiver of retroactive eligibility and the work requirement. These include applying a $5,000 asset test to all coverage groups that currently do not have an asset test and eliminating hospital presumptive eligibility for all coverage groups. The state’s pending waiver application proposes to implement these initiatives within six months of demonstration approval.

Eligibility expansions

Aside from planned implementation of the ACA Medicaid expansion in two states in FY 2019, most other eligibility expansions for FY 2018 and FY 2019 are narrow in scope. Overall, ten states implemented Medicaid eligibility expansions in FY 2018, and seven states plan to implement expansions in FY 2019.

Two states (Maine and Virginia) plan to implement the ACA Medicaid expansion in FY 2019. These expansions will add to the 32 states that had already implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 2018 (Figure 1). In Virginia, the expansion was adopted as part of the FY 2019-2020 Medicaid budget, with implementation planned for January 1, 2019. Maine voters adopted the Medicaid expansion through a ballot initiative in November 2017 that required submission of a state plan amendment (SPA) within 90 days and implementation of expansion within 180 days of the measure’s effective date.18 After failing to meet the SPA submission deadline (April 3, 2018), Maine’s Governor complied with a Maine Supreme Judicial Court order to submit an expansion SPA on September 4, 2018 but also sent a letter to the federal government asking CMS to reject the SPA. The expansion had not yet been implemented at the time of the survey, and implementation will fall to the new governor after the November 2018 election.

Three additional states (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah) will have referendum initiatives to adopt the Medicaid expansion on the November 2018 ballot. Montana also has an expansion-related initiative for voters on the November ballot that would eliminate the state’s June 2019 expansion program sunset date and raise tobacco taxes to fund the state’s share of expansion costs.

| Exhibit 2: Eligibility Expansions by Policy Authority | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019* | |||

| SPA | 8 States | AR, CO, ID, MO, PA, SC, UT, VT | 6 States | CT, MD, ME, MO, NJ, VA |

| Section 1115 Waiver | 3 States | DE, UT, VA | 0 States | |

| *Iowa’s FY 2019 eligibility expansion that reinstated 3-month retroactive eligibility for Medicaid-eligible nursing facility residents did not require new Section 1115 or SPA authority. | ||||

Ten states implemented more narrow eligibility expansions in FY 2018 and five states plan to implement more limited expansions in FY 2019. In contrast to eligibility restrictions, which states are primarily implementing under Section 1115 authority, most states implementing or planning eligibility expansions in FY 2018 or FY 2019 are doing so through optional authority using a state plan amendment (SPA) (Exhibit 2). Some examples of these other expansions include the following:

- In FY 2018 under Section 1115 waiver authority, Utah implemented coverage for individuals with income below 5% of the federal poverty level (FPL) who are chronically homeless, justice-involved, or in need of substance use and/or mental health treatment. The state also has approval to implement 12 month continuous eligibility for this population.

- Missouri increased asset limits in both FY 2018 and FY 2019 for aged and disabled beneficiaries and Vermont increased asset limits in FY 2018 for their Working People with Disabilities Program.

- In FY 2018, Arkansas and South Carolina eliminated the five-year waiting period on Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children and pregnant women.19

Premiums

The Medicaid statute generally does not allow states to charge premiums to most Medicaid beneficiaries. Historically, premiums were limited to special higher income categories of beneficiaries such as expanded Medicaid for the working disabled. However, some states have obtained waiver authority to charge higher premiums and/or copayments than otherwise allowed.

Only Indiana reported activity related to Medicaid premiums in FY 2018 (Table 2). Effective January 1, 2018, the state changed its monthly premiums (which are paid into a health account) for expansion adults from 2% of income to tiered amounts based on income ranges (expressed as a percentage of the FPL). The result is reduced fluctuation of premiums. This report considers the change neutral from the beneficiary’s perspective.

Seven states report proposed implementation of new premium programs or changes to existing premiums for FY 2019 (Table 2). Three of these states (Idaho, Indiana, and Iowa) have already received approval for these changes, while they are still pending as part of Section 1115 waiver requests in four states (Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, and New Mexico). Notable FY 2019 premium policy changes include an approved waiver provision in Indiana to implement a premium surcharge for tobacco users and a pending waiver request in Michigan to require premiums of up to 5% of income (a higher amount than CMS has ever approved for any state) for expansion adults after 48 cumulative months of expansion eligibility.

Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

In recent years, many states have implemented new policies to connect individuals involved with the criminal justice system to Medicaid, as the Medicaid expansion extended new coverage to these individuals in many states (especially childless adults who were not previously eligible in most states). Connecting these individuals to health coverage20 can facilitate their integration back into the community upon release. While individuals may be enrolled in Medicaid while they are incarcerated, Medicaid cannot cover the cost of their care during incarceration, except for inpatient services. Nearly all states have policies in place to cover inpatient care under Medicaid for eligible, incarcerated individuals (Exhibit 3 and Table 3). Most states are also working with corrections agencies and with local jails to facilitate Medicaid enrollment prior to release. The majority of states do not terminate Medicaid coverage for enrollees who become incarcerated: states either maintain the eligibility of the incarcerated individual with benefits limited to inpatient hospital care, or they suspend eligibility. When coverage is suspended, it can be reinstated more easily and quickly upon release from incarceration or when an inpatient hospital stay occurs.

As this report was being finalized, the Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act was expected to be signed into law. Beginning in October 2019, the Act would prohibit states from terminating Medicaid eligibility for an individual under age 21 or former foster care youth up to age 26 while incarcerated. States would also be required to redetermine eligibility prior to release without requiring a new application and restore coverage upon release.

While both Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states have adopted strategies to connect justice-involved individuals to Medicaid coverage, these initiatives affect many more people in expansion states compared to non-expansion states where Medicaid eligibility for adults remains restrictive.

| Exhibit 3: Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population in FY 2018 and/or FY 2019 (# of States) | |||

| Select Medicaid Coverage Policies for the Criminal Justice Population | Jails | Prisons* | Parolees |

| Medicaid coverage for inpatient care provided to incarcerated individuals | 42 | 48 | N/A |

| Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release from incarceration or for parolees | 34 | 39 | 26 |

| Eligibility maintained or suspended (rather than terminated) for Medicaid enrollees who become incarcerated^ | 36 | 38 | N/A |

| ^States that continue Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals but limit covered benefits to inpatient hospitalization are also included in the count of states that suspend eligibility. *The District of Columbia has jails but not a prison system. However, DC is counted under Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies because some individuals who serve prison terms outside of DC may be placed in residential re-entry centers upon returning to DC and may apply for Medicaid to access coverage for 24-hour inpatient care and to facilitate enrollment prior to release. | |||

Table 1: Changes to Eligibility Standards in all 50 States and DC, FY 2018 and FY 2019

| Eligibility Standard Changes | ||||||

| States | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | ||||

| (+) | (-) | (#) | (+) | (-) | (#) | |

| Alabama | X | |||||

| Alaska | ||||||

| Arizona | ||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | |||

| California | ||||||

| Colorado | X | |||||

| Connecticut | X | X | ||||

| Delaware | X | |||||

| DC | X | |||||

| Florida | X | |||||

| Georgia | ||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||

| Idaho | X | |||||

| Illinois | ||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | |||

| Iowa | X | X | ||||

| Kansas | ||||||

| Kentucky | X | |||||

| Louisiana | ||||||

| Maine | X | X | ||||

| Maryland | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | |||||

| Michigan | X | |||||

| Minnesota | ||||||

| Mississippi | ||||||

| Missouri | X | X | ||||

| Montana | ||||||

| Nebraska | ||||||

| Nevada | ||||||

| New Hampshire | X | |||||

| New Jersey | X | |||||

| New Mexico | X | X | ||||

| New York | X | |||||

| North Carolina | ||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||

| Ohio | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | ||||||

| Oregon | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | |||||

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| South Carolina | X | |||||

| South Dakota | X | |||||

| Tennessee | ||||||

| Texas | ||||||

| Utah | X | X | ||||

| Vermont | X | |||||

| Virginia | X | X | ||||

| Washington | ||||||

| West Virginia | ||||||

| Wisconsin | ||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||

| Totals | 10 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 1 |

NOTES: From the beneficiary’s perspective, eligibility expansions or policies likely to increase Medicaid enrollment are denoted with (+), eligibility restrictions or policies likely to decrease enrollment are denoted with (-), and neutral changes are denoted with (#). This table captures eligibility changes that states have implemented or plan to implement in FY 2018 or FY 2019, including changes that are part of pending Section 1115 waivers. For pending waivers, only provisions planned for implementation before the end of FY 2019 (according to waiver application documents and/or interviews with state Medicaid staff) are counted in this table. Waiver provisions in pending waivers that states plan to implement in FY 2020 or after are not counted here. SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. | ||||||

Table 2: States Reporting Eligibility21 and/or Premium22 Changes in FY 2018 and FY 201923

| State | Fiscal Year | Eligibility Changes |

| Alabama | 2019 | Parents & Caretaker Relatives (-): Pending Section 1115 Waiver: Add a work/community engagement requirement for non-disabled, non-pregnant individuals under age 60 (75,000 individuals). |

| Arkansas | 2018 | Expansion Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Limit retroactive coverage from 90 to 30 days. Expansion Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work requirement for expansion adults (40,000 individuals) (first case closures occurred 9/1/2018). Expansion Adults (#) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: End premium assistance program for employer sponsored insurance and transition individuals to QHP coverage (40 individuals). Children and Pregnant Women (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year waiting period on Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children and pregnant women. |

| Colorado | 2018 | Aged & Disabled (+): Medicaid buy-in option for individuals in support living services, spinal cord injury, & brain injury waivers (40 individuals). |

| Connecticut | 2018 | Parents & Caretaker Relatives (-): Reduce the income threshold for Husky A from 155% FPL to 138% FPL (12,000 individuals). |

| 2019 | Parents & Caretaker Relatives (+): Increase the income threshold for Husky A from 138% FPL to 155% FPL (12,000 individuals). | |

| Delaware | 2018 | Former Foster Youth (+) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add coverage for individuals who were in foster care and on Medicaid in another state at the time they aged out of the foster care system (under age 26 and under 133% FPL) (3 individuals). |

| District of Columbia | 2019 | Medically Needy (#): Clarification of Medically Needy eligibility criteria (with regard to countable medical expenditures) (7,000 individuals). |

| Florida | 2019 | Non-Pregnant Adults (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver:Discontinue retroactive eligibility beyond the current application month. |

| Idaho | 2018 | Children (+): Cover children with serious emotional disturbance (SED) in families with income between 185% and 300% FPL (SED YES program) (2,000 to 10,000 children). |

| 2019 | Premiums (New): Children enrolled in the 1915(i) SED YES program will be subject to a premium in early 2019. | |

| Indiana | 2018 | Expansion Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Three-month lock-out of coverage following a 90-day period of disenrollment for failure to comply with redetermination. Expansion Adults (#) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: End HIP Link premium assistance program for employer-sponsored insurance (enrollees will be moved to other HIP 2.0 coverage). Parents & Caretaker Relatives (#) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Transitional Medical Assistance (TMA) is now for families in which a qualified HIP low-income parent/caretaker would otherwise fail financial eligibility due to new or increased earned income from a job or from self-employment exceeding the 133% FPL MAGI income limit. Premiums (Neutral) for Expansion and Other Adults Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Monthly POWER Account contributions are now tiered based on income. The tiered amounts, effective January 1, 2018, are $1.00, $5.00, $10.00, $15.00, and $20.00. |

| 2019 | Expansion and Other Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work/community engagement requirement, phased implementation beginning 1/1/2019. Premiums (New) for Expansion Population Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add a 50% premium surcharge for tobacco users beginning in the second year of enrollment. | |

| Iowa | 2018 | All Groups but Pregnant Women and Children Under Age 1 (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility. |

| 2019 | Nursing Facility Residents (+): Reinstate 3-month retroactive eligibility for Medicaid-eligible nursing facility residents, effective July 1, 2018. Premiums (New) Approved Section 1115 Waiver: Adults must complete healthy behaviors (preventive dental visit and health risk assessment) or pay a $3 monthly premium for the Dental Wellness Plan. | |

| Kentucky | 2019 | Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering:24 Work/community engagement requirement. Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Eliminate retroactive eligibility. Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Reasonable promptness waiver to delay coverage until the first day of the first month following receipt of the required premium. Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Disenrollment and lock-out of coverage if renewal is not completed timely. Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Disenrollment and lock-out of coverage if changes affecting eligibility are not reported timely. Expansion Adults (-) Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Disenrollment and lock-out of coverage for non-payment of premiums. Premiums (New) for Expansion Adults and Parents/Caretakers Sec. 1115 Waiver Approval Set Aside by Court, CMS Reconsidering: Up to 4% of income but at least $1. |

| Maine | 2019 | Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Add a work requirement for many groups of traditional adults. Those who do not comply with work requirement would be limited to no more than 3 months coverage in a 36-month period. All Groups (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility. Adults (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Apply a $5,000 asset test to all coverage groups that do not currently have an asset test (under current law there is no asset test for coverage groups based solely on low income (vs. old age/disability)). All Groups (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate hospital presumptive eligibility. Expansion Adults (+): Implement ACA Medicaid expansion (approved by referendum in November 2017) via a SPA.25 Premiums (New) for Adults Ages 19 to 64 Pending Sec 1115 Waiver: Premiums of between $10 and $40 per month, not to exceed 2% of income. |

| Maryland | 2019 | Adults (+): Increased income threshold for limited family planning benefit from 200% FPL to 250% FPL, remove age limit, and expanded coverage to include men. Switched from 1115 to SPA authority (9,000 individuals). |

| Massachusetts | 2019 | Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate 90-day period of provisional eligibility for adults under age 65 without verified income. The following groups will continue to be eligible for 90-day provisional eligibility pending verification of income: (1) pregnant women with self-attested MAGI income less than or equal to 200% FPL; (2) individual with HIV-positive status with self-attested MAGI income less than or equal to 200% FPL; or (3) individual in active treatment for breast or cervical cancer with self-attested MAGI income less than or equal to 250% FPL. (135,000).26 |

| Michigan | 2019 | Expansion Adults 100-138% FPL (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Disenroll individuals for non-payment of required premiums after reaching 48 months of cumulative Healthy Michigan Plan eligibility. Expansion Adults 100-138% FPL (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Disenroll individuals for failure to complete an annual healthy behavior requirement after reaching 48 months of cumulative Healthy Michigan Plan eligibility. Premiums (Increased) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Require premium of 5% of income for expansion population with incomes between 100% and 133% FPL. |

| Missouri | 2018 | Aged & Disabled (+): Asset limit increase (phased increase from FY 2018 through FY 2022) (2,865 individuals). |

| 2019 | Aged & Disabled (+): Asset limit increase (phased increase from FY 2018 through FY 2022) (992 individuals) | |

| New Hampshire | 2019 | Expansion Adults (-): Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work/community engagement requirement for expansion population, implementation beginning 1/1/2019. Expansion Adults (-): Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility for expansion population. |

| New Jersey | 2019 | Family Planning Enrollees (+): Expansion of family planning to cover men and women ages 19 to 65 between 138% and 205% FPL (over 30,000 individuals). |

| New Mexico | 2018 | Aged & Disabled (-): Home equity exclusion changed from the federal maximum of $840,000 to the federal minimum of $560,000 (fewer than 5 individuals). |

| 2019 | Family Planning (-) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Limit family planning to age 51 and under (or under 65 with Medicare) (15,200 individuals). Most Managed Care Members (-) Pending 1115 waiver: Limit retroactive Medicaid to one month for most managed care members (8,000 individuals). Expansion Adults (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Reasonable promptness waiver to delay coverage until the first day of the first month following receipt of the required premium (pending CMS approval of proposed premiums). Expansion Adults (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Disenrollment and lock-out of coverage for non-payment of premiums. Transitional Medical Assistance Parents/Caretakers (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate TMA coverage pathway for parents/caretakers. Premiums for Expansion Adults above 100% FPL (New) Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: New monthly premiums, which could be lowered under provisions of the healthy behavior incentive program. | |

| New York | 2018 | Former Foster Youth (#): Eliminate coverage category for individuals under age 26 who were in foster care and on Medicaid in another state at the time they aged out of the foster care system (0 individuals in this category). |

| Ohio | 2019 | Expansion Adults (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work/community engagement requirement for Group VIII (expansion) MAGI adults (701,707 individuals). |

| Pennsylvania | 2018 | Children Under Age 4 (+): Continuous eligibility (7,746 children). |

| South Carolina | 2018 | Children & Pregnant Women (+): Implemented the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year waiting period on Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children and pregnant women. |

| South Dakota | 2019 | Adults in Minnehaha and Pennington Counties (-): Pending Sec. 1115 Waiver: Work/community engagement requirement, with offer of 12 months TMA and an additional 12 months premium assistance to individuals who continue to meet the work requirement but whose income increases above the Medicaid eligibility limit as a result of meeting the requirement (1,300 individuals). |

| Utah | 2018 | Parents & Caretakers (+): Increased the Basic Maintenance Standard to 55% FPL (3,000 individuals). Adults (+) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: New eligibility group for chronically homeless, justice-involved individuals and those in need of substance abuse and/or mental health treatment, with income below 5% FPL (2,800 individuals). Adults (-) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Eliminate retroactive eligibility for Primary Care Network (PCN) adults. Adults (+) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Twelve months continuous eligibility for targeted childless adult population. |

| Vermont | 2018 | Aged & Disabled (+): Increased asset level for Working People with Disabilities program (from $5,000 to $10,000 for an individual and from $6,000 to $15,000 for a couple) (70 individuals). |

| Virginia | 2018 | Disabled (+) Approved Sec. 1115 Waiver: Increased eligibility from 80% to 100% FPL for waiver services for people with serious mental illness (GAP waiver program, full restoration to pre-2016 level) (2,000 adults with SMI). |

| 2019 | Expansion Adults (+): ACA expansion of eligibility to non-caretaker, low-income adults between 0% and 138% of FPL (400,000 individuals). |

Table 3: Corrections-Related Enrollment Policies in all 50 States and DC, in Place in FY 2018 And Actions Taken in FY 2019

| States | Medicaid Coverage For Inpatient Care Provided to Incarcerated Individuals | Medicaid Outreach/Assistance Strategies to Facilitate Enrollment Prior to Release^ | Medicaid Eligibility Suspended Rather Than Terminated For Enrollees Who Become Incarcerated^ | |||||||||

| Jails | Prisons | Jails | Prisons | Jails | Prisons | |||||||

| In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | In place FY 2018 | New or Expanded FY2019 | |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X* | X* | ||||||

| DC | X | N/A | N/A | X | X | X | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||||||||

| Georgia | X | |||||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Idaho | X | X | ||||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Kansas | X | X* | X | |||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Louisiana | X | X | X* | X | X | X | ||||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X* | X | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | ||||||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| North Carolina | X | X | ||||||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Oklahoma | X | |||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Vermont | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 42 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 32 | 5 | 38 | 4 | 35 | 2 | 37 | 1 |

NOTES: ^States with “Medicaid outreach assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release” include those implementing a variety of strategies. In many cases, staff of the prison or jail provide most of the assistance in collaboration with the Medicaid agency. ^States that continue Medicaid eligibility for incarcerated individuals but limit covered benefits to inpatient hospitalization are also included in the count of states that suspend eligibility. “*” indicates that a policy was newly adopted in FY 2019, meaning that the state did not have any policy in that category/column in place in FY 2018. N/A: The District of Columbia has jails but no prisons (however, individuals returning to DC from federal prisons may be placed in residential re-entry centers and have the opportunity to apply for Medicaid from there in order to attain coverage for 24 hour inpatient care and to facilitate enrollment prior to release). SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2018. | ||||||||||||

Report: Managed Care Initiatives

Key Section Findings

Managed care is the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 1, 2018, among the 39 states with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), 33 states reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs, a notable increase from the 29 states reporting 75% or more as of July 1, 2017. Although many states still carve-out behavioral health services from MCO contracts, movement to carve-in these services continues – two states in FY 2018 and 11 states in FY 2019 reported BH service carve-ins or implementation of an integrated MCO arrangement. Nearly all states have managed care quality initiatives in place such as pay for performance or capitation withholds.

What to watch:

- The current administration is expected to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations for public comment.

- Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. Alaska is contracting with one MCO to serve one geographic area, and Arkansas will begin making actuarially sound “global payments” to “Provider-led Arkansas Shared Savings Entities” (PASSEs) that serve Medicaid beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities service needs.

- The 2016 Medicaid MCO rule allows states to use “in lieu of” authority to cover services for adults who receive inpatient psychiatric or SUD treatment services in an IMD for no more than 15 days in a month. In this survey, 28 of the 39 MCO states reported that they are using this authority for both FYs 2018 and 2019, and three states reported plans to begin using this authority in FY 2019. The SUPPORT Act would create a new state option from October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2023 to cover IMD services for up to 30 days in a year for individuals with an SUD and also would codify the provision allowing MCOs to offer “in lieu of” IMD coverage for up to 15 days in a month.

- An increasing number of states (23 in FY 2018) set a target percentage of MCO provider payments that must be in alternative payment models (APMs), up from 13 states in FY 2017 and 5 states in FY 2016. States are also increasingly requiring MCOs to screen beneficiaries for social needs (16 states in FY 2018 and 3 additional states in FY 2019); and to provide care coordination pre-release to incarcerated individuals (6 states in FY 2018 and 2 additional states in FY 2019).

Tables 4 through 7 include more detail on the populations covered under managed care (Tables 4 and 5), behavioral health services covered under MCOs (Table 6), and managed care quality initiatives (Table 7).

NEW: 50-state Medicaid survey finds that states are increasingly relying on managed care. In 33 states of 39 states with managed care organizations (MCOs), at least 75% of all Medicaid beneficiaries are in managed care.

Managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2018, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut,27 and Wyoming – had some form of managed care in place, unchanged from July 2017. Compared to the prior year, the number of states contracting with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) (39 states) also remained unchanged while two fewer states reported operating a Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) program (14 states). PCCM is a managed fee-for-service (FFS) based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care.

Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, five operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 34 states operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only28 (Figure 2 and Table 4). In total, 28 states contracted with one or more PHPs to provide Medicaid benefits including, behavioral health care, dental care, vision care, non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), or long-term services and supports (LTSS).

The current administration is expected to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations for public comment. Under the previous administration in April 2016, CMS issued a final rule on Medicaid managed care providing a framework of plan standards and requirements designed to improve the quality, performance, and accountability of these programs.29 ,30 The new rule represented a major revision and modernization of federal regulations in this area. The Trump Administration, however, is expected to release revised Medicaid managed care regulations before the end of CY 2018.31

In advance of releasing revised Medicaid managed care regulations, CMS released an Informational Bulletin32 in June 2017 indicating they would use “enforcement discretion” to work with states on achieving compliance with the new managed care regulations, except for specific areas that “have significant federal fiscal implications.” In this year’s survey, MCO states were asked whether they have asked CMS for flexibility in meeting managed care regulation deadlines. States answering “yes” most frequently reported requesting relief on deadlines related to member services (e.g., grievance and appeals procedures or member handbooks and enrollment requirements) and provider/network requirements (e.g., screening and enrollment of network providers or provider directory requirements).

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions and new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. This year’s survey showed continued notable growth. Among the 39 states with MCOs, 33 states33 reported that 75% or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2018 (up from 29 states in last year’s survey), including nine of the ten states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment. These nine states (California, New York, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Michigan, and Georgia) account for over half of all Medicaid beneficiaries across the country (Figure 3 and Table 4).34

Children and adults, particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion, are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or persons with disabilities. Thirty-five35 of the 39 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of all children through MCOs. Of the 32 states that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2018, 27 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults.36 The large majority of these states (23 states) covered more than 75% of beneficiaries in this group through capitated managed care. New Hampshire reported that most of its ACA expansion adults are enrolled in Qualified Health Plans (with premium assistance, under Section 1115 authority) and only 20% are enrolled in MCOs.37 The state reported, however, that it will end its premium assistance waiver (as of December 31, 2018) and will transition QHP-enrolled members to MCOs. Thirty-one of the 39 MCO states reported covering 75% or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. In contrast, the elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 20 of the 39 MCO states reporting coverage of 75% or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 3).

In states with both MCOs and PCCM programs, MCOs cover a larger share of beneficiaries than PCCM programs in a majority of these states. However, Colorado is an exception: as of July 1, 2018, a majority of Colorado’s enrollees were in the PCCM program, which is the foundation of the state’s “Accountable Care Collaboratives.”

Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. Alaska is contracting with one MCO to serve one geographic area that includes Anchorage and the Mat-Su Valley, and Arkansas will begin making actuarially sound “global payments” (beginning January 1, 2019) to “Provider-led Arkansas Shared Savings Entities” (PASSEs) that will serve Medicaid beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities service needs. Only one state reported policies that reduced the state’s reliance on the MCO model of managed care: Massachusetts reported that the implementation of its Accountable Care Organization (ACO) program beginning in FY 2018 has resulted in decreased MCO enrollment as MCO enrollees may choose to enroll in ACOs instead.

Populations with Special Needs

For geographic areas where MCOs operate, this year’s survey asked MCO states whether, as of July 1, 2018, certain subpopulations with special needs were enrolled in MCOs for their acute care services on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded. This year’s survey further grouped subpopulations by dual eligible and by LTSS status (Exhibit 4 and Table 5).

Pregnant women were the group most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis while persons with I/DD were among the least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis. As a group, foster children were most likely to be enrolled on a voluntary basis, although they were enrolled on a mandatory basis in a larger number of states. Among states indicating that the enrollment approach for a given group or groups varied, the location of LTSS services provided (residential versus community-based) was a frequently cited basis of variation. States with Financial Alignment Demonstrations for dual eligibles in addition to other managed care programs also often cited varying enrollment criteria for dual eligibles.

| Exhibit 4: MCO Enrollment of Populations with Special Needs, July 1, 2018(# of States) | ||||||||

| Non-Dual/Non-LTSS: | Non-Dual/Receives LTSS: | Dual Eligibles | ||||||

| Pregnant women | Foster children | CSHCNs | Persons with SMI/SED | Persons with I/DD | Persons w/ physical disabilities | Seniors | ||

| Always mandatory | 36 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 11 |

| Always voluntary | 2 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Varies | 0 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 14 |

| Always excluded | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| Notes: “CSHCNs” – children with special health care needs, “SMI/SED” – persons with serious mental illness or serious emotional disturbance, “I/DD” – persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. | ||||||||

Acute Care Managed Care Population Changes

In both FY 2018 and FY 2019, only a few states reported actions to increase enrollment in acute care managed care, reflecting full or nearly full MCO saturation in most MCO states. As described above, Alaska and Arkansas reported plans to implement an MCO program for the first time in FY 2019. Of the 39 states with MCOs already in place as of July 1, 2018, five states in FY 2018 and five states in FY 2019 indicated that they made specific policy changes to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs through geographic expansion, voluntary or mandatory enrollment of new groups into MCOs, or mandatory enrollment of specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis (Exhibit 5). Thirty-seven states reported that acute care MCOs were operating statewide as of July 2018, including Illinois, which expanded MCOs statewide in FY 2018. The remaining two MCO states without statewide programs (Colorado and Nevada) did not report a geographic expansion planned for FY 2019.

| Exhibit 5: Medicaid Acute Care Managed Care Population Expansions, FY 2018 and FY 2019 | ||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |

| Geographic Expansions | IL | — |

| New Population Groups Added | PA, TX, VA | IL, NH, OH, PA, VA |

| Voluntary to Mandatory Enrollment | WI | — |

| Implementing an MCO program for the first time | — | AK, AR |

Two notable acute care MCO expansions relate to programs that combine both acute care and LTSS:

- In January 2018, Pennsylvania began to phase-in its Community HealthChoices (CHC) program which provides both physical health and long-term services and supports through newly contracted MCOs. CHC enrollees include individuals in nursing facilities (currently carved out of managed care after 30 days), full benefit dually-eligible individuals, and individuals receiving home and community-based services.

- Virginia implemented its CCC Plus (Commonwealth Coordinated Care) program in FY 2018 making MCO enrollment mandatory for most LTSS populations.

In FY 2018 and FY 2019, states expanded MCO enrollment (either voluntary or mandatory) to other groups including state wards and foster children (Illinois), expansion adults transitioning from the state’s premium assistance program to MCO coverage (New Hampshire), workers with disabilities and persons receiving Specialized Recovery Services (Ohio), the Breast and Cervical Cancer and Adoption Assistance eligibility groups (Texas), and persons with third party liability coverage (Virginia).

Only one state made enrollment mandatory for a specific eligibility group that was formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis: Wisconsin made enrollment mandatory in FY 2018 for SSI adults with disabilities that do not have long-term care needs, are not enrolled in HCBS or MLTSS, are not tribal members, and are not dual eligibles.

Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Behavioral Health Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Although MCOs are at risk financially for providing a comprehensive set of acute care services, nearly all states exclude or “carve-out” certain services from their MCO contracts, frequently behavioral health services. States with acute care MCOs were asked to indicate whether specialty outpatient mental health (MH) services, inpatient mental health services, and outpatient and inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services are always carved-in (i.e., virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or the carve-in status varies by geographic or other factors. More than half of the 39 MCO states reported that specific behavioral health service types were carved into their MCO contracts, with specialty outpatient mental health services somewhat less likely to be carved in (Exhibit 6 and Table 6).

| Exhibit 6: MCO Coverage of Behavioral Health, July 1, 2018 (# of States) | ||||

| Specialty Outpatient MH* | Inpatient MH | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD | |

| Always carved-in | 22 | 24 | 27 | 26 |

| Always carved-out | 10 | 7 | 7 | 6 |

| Varies | 7 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| *“Specialty outpatient mental health” services mean services used by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED), commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers. | ||||

In FY 2018, Mississippi and South Carolina reported actions to carve behavioral health services into their MCO contracts and Washington reported implementing integrated MCO contracts in additional geographic areas.

In FY 2019, 11 states reported actions impacting the coverage of behavioral health services under MCO contracts:

- Six states (Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) reported actions to carve behavioral health services into their MCO contracts.

- Arizona and Washington reported plans to implement additional integrated MCO contracts.

- Michigan reported a plan to implement pilot programs that would provide both physical and behavioral health services.

- Ohio reported a full carve-in of behavioral health services as of July 1, 2018.

- Arkansas reported plans to implement a new MCO program to serve beneficiaries who have complex behavioral health and intellectual and developmental disabilities needs.

Institutions for Mental Disease (IMD) “In Lieu OF” Rule

The 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule38 allows states (under the authority for health plans to cover services “in lieu of” those available under the Medicaid state plan), to receive federal matching funds for capitation payments on behalf of adults who receive inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder (SUD) treatment or crisis residential services in an IMD for no more than 15 days in a month.39 States were asked whether or not they planned to use this new authority. Of the 39 states with MCOs as of July 1, 2018, 28 states answered “yes” for both FYs 2018 and 2019; three states reported plans to begin using this authority in FY 2019; and five states answered “no.”40 Also, North Carolina reported using “in lieu of” authority in its PHP contract and Arkansas reported plans to use this authority when it launches its new MCO program in January 2019. At the time this report was being finalized, however, the SUPPORT Act41 was expected to be signed into law creating a new state option from October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2023 to cover IMD services for up to 30 days in a year for individuals with an SUD. The SUPPORT Act also codified the 2016 Medicaid Managed Care Final Rule provision allowing MCOs to offer “in lieu of” IMD coverage for up to 15 days in a month.

Additional Services

Thirty-seven states with MCO contracts as of July 1, 2018, reported that MCO plans in their states may offer a range of services beyond those described in the state plan or waivers. The most common additional services reported were limited or enhanced adult dental services beyond contractually required state plan benefits, enhanced vision services for adults, and enhanced transportation services. Other value-added services reported included enhanced care coordination, wellness incentives, waiving co-payments, routine or school/sports physicals, and diabetic, weight-loss, tobacco cessation, and chiropractic services. Several states noted that MCOs offer services that address social determinants of health, including GED coaching, housing support, mother and baby supports, educational services and food access services. Others reported offering services/items to promote safety, including helmets and infant car seats.

Managed Care (Acute and LTSS) Quality, Contract Requirements, and Administration

Quality Initiatives

Over time, the expansion of comprehensive risk-based managed care in Medicaid has been accompanied by greater attention to measuring quality and plan performance and, increasingly, to measuring health outcomes. After years of comprehensive risk-based managed care experience within the Medicaid program, many states now incorporate quality into the procurement process, as well as into ongoing program monitoring.42

States procure MCO contracts using different approaches; however, most states use competitive bidding, in part because the dollar value is so large. Under these procurements, states can specify requirements and criteria that go beyond price, and may expect plans to compete on the basis of value-based payment arrangements with network providers, specific policy priorities such as improving birth outcomes, strategies to address social determinants of health, and/or other specific performance and quality criteria. In this year’s survey, states were asked if they used, or planned to use, the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA’s) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) scores as criteria for selecting MCOs. Of the 39 states with MCOs, 14 indicated that they use or plan to use HEDIS scores as criteria for selecting MCOs.

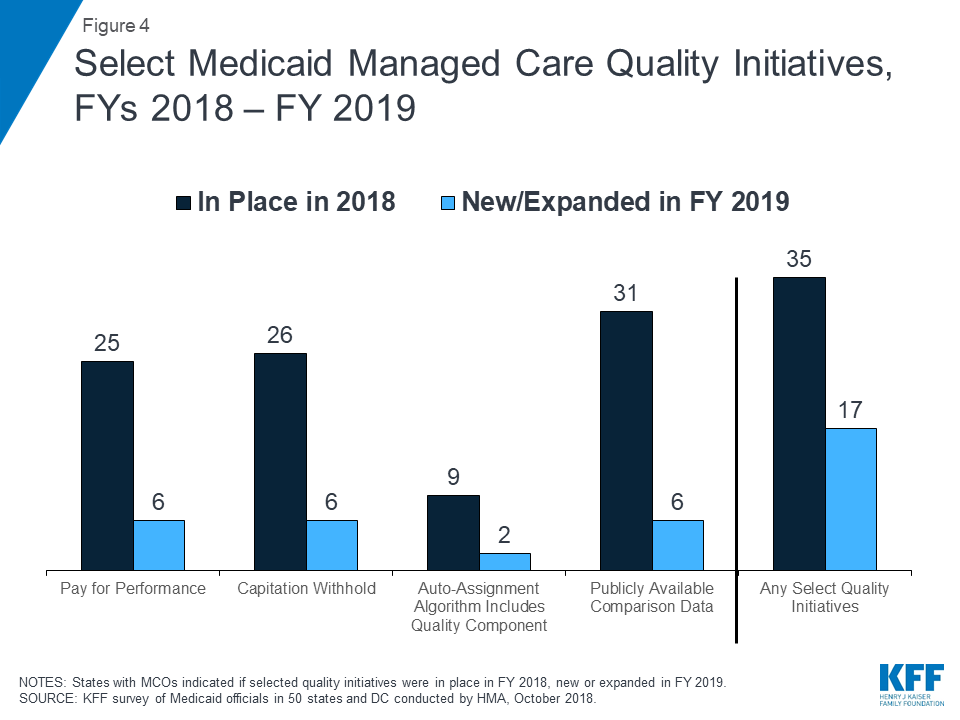

Nearly all MCO states (35 states) reported using at least one select Medicaid managed care quality initiative in FY 2018 (Figure 4 and Table 7). States were asked to indicate whether they had specific managed care quality strategies (acute and/or MLTSS) in place in FY 2018 and to identify newly added or expanded initiatives for FY 2019. More than three quarters of MCO states reported having initiatives in place in FY 2018 that make MCO comparison data publicly available. More than half of MCO states reported capitation withhold arrangements and/or pay for performance incentives in FY 2018. Fewer states reported use of an auto-assignment algorithm that includes quality performance measures.

In FY 2019, 17 MCO states expect to implement new or expanded quality initiatives (Figure 4). The predominance of states reporting new or expanded activity in FY 2019 reported activity related to enhancing/expanding existing initiatives. However, two states reported new initiatives. Utah is planning to create a public facing dashboard for its acute care MCOs to make comparison data publicly available in FY 2019 and Louisiana is planning to add quality as a component to its auto-assignment algorithm for acute care contracts in calendar year 2019 (Table 7).

State-mandated Performance Improvement Project Examples

Federal regulations mandate that states must require, under contracts starting on or after July 1, 2017, each MCO or PHP to establish and implement an ongoing comprehensive quality assessment and performance improvement program for Medicaid services. Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs) may be designated by CMS, by states, or developed by health plans, but must be designed to achieve significant, sustainable improvement in health outcomes and enrollee satisfaction. In this year’s survey, states were asked to indicate whether they mandate MCO PIPs in a particular focus area. States reported a range of state-mandated PIP focus areas, including prenatal smoking and antipsychotic medication use in children (Kentucky), diabetes prevention and management and clinical depression screening and management (New Mexico), child health (Ohio), strengthening care coordination and encouraging transitions from nursing facilities to community care (Pennsylvania), and individuals with complex needs, especially those with comorbid anxiety and depression (Texas).

Contract Requirements

Alternative [Provider] Payment Models Within MCO Contracts

Value-based purchasing (VBP) strategies are important tools for states pursuing improved quality and outcomes and reduced costs of care within Medicaid and across payers. Generally speaking, VBP strategies include activities that hold a provider or MCO accountable for cost and quality of care.43 This often includes efforts to implement alternative payment models (APMs) which replace FFS/volume-driven provider payments with payment models that incentivize quality, coordination, and value (e.g., shared savings/shared risk arrangements and episode-based payments). Many states included a focus on adopting and promoting APMs as part of their federally-supported State Innovation Model (SIM) projects and as part of delivery system reform efforts approved under Section 1115 Medicaid waivers.44 A growing number of states are encouraging or requiring Medicaid MCOs to adopt APMs to advance VBP in Medicaid.

More than half of MCO states (23 states) identified a specific target in their MCO contracts for the percentage of provider payments, network providers, or plan members that MCOs must cover via alternative provider payment models in FY 2018 (Exhibit 7). (Only 13 states identified having a target percentage in place in FY 2017 and five states in FY 2016.) Four additional states plan to add a target percentage in FY 2019.

| Exhibit 7: States that Require MCOs to Meet a Target % for Provider APMs | ||

| # of States | States | |

| In Place FY 2018 | 23 | AZ, CA, DC, DE, HI, IA, LA, MA, MN, MO, NE, NH, NM, NY, OH, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, WA, WI, WV |

| Plan to Begin in FY 2019 | 4 | FL, OR, UT, VA |

In FY 2018, 10 states had contracts that required Medicaid MCOs to adopt specific alternative provider payment models (e.g., episode of care payments, shared savings/shared risk, etc.), while eight states had contracts that encouraged MCOs to adopt specific APMs (Exhibit 8). In FY 2019, three additional states plan to require the use of specific APMs while four additional states plan to encourage specific APMs. CMS launched a Learning and Action Network (LAN) in 2015 to encourage alignment across public and private sector payers by providing a forum for sharing best practices and developing common approaches to designing and monitoring of APMs, as well as by developing evidence on the impact of APMs.45 Several states reported use of the LAN framework in devising MCO APM requirements (see examples below).

| Exhibit 8: States that Require vs. Encourage the Use of Specific APMs | ||||

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | |||

| Require | 10 States | IA, LA, NE, NM, OH, PA, RI, TN, WA, WV | 3 States | AZ, KS, MI |

| Encourage | 8 States | DC, DE, IL, MA, NH, NY, TX, VA | 4 States | NJ, OR, UT, WI |

State APM Strategies for Medicaid MCO Contracts

- Arizona has set value-based APM targets at 50% for acute care MCOs, 35% for LTSS MCOs, and 25% for its seriously mentally ill (SMI) integrated population. The state plans to require use of strategies in LAN-APM46 categories 3 and 4 with targets of 40% for acute care MCOs, 25% for MLTSS, and 10% for SMI plans in FY 2019.

- Louisiana requires MCOs to implement APMs that fall within the LAN category 2A, 2C, 3, or 4, with an expectation that the MCO will implement one new contract in category 3 or 4 by 2019.

- Massachusetts requires that 60% of enrollees are covered by APM arrangements in years 1 and 2 of the current MCO contract, with 70% of enrollees in APM arrangements by years 3 and 4.

- Michigan plans to require use of the state preferred patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model in FY 2019.

- New Mexico requires that MCOs implement APM arrangements that: include a quality/outcome-based bonus or withhold for a minimum of 7% of all MCO provider payments; have an upside-only shared savings arrangement or two or more bundled payments (for episodes of care) for a minimum of 10% of all MCO provider payments; and have an upside and downside risk or a full-risk global payment arrangement for at least 3% of all MCO provider payments.

Social Determinants of Health