Sources of Payment for Uncompensated Care for the Uninsured

Issue Brief

Summary

Uncompensated care costs for the nation’s uninsured averaged $42.4 billion per year in the 2015-2017 time period. While substantial, these costs significantly declined following implementation of the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion, down from $62.8 billion per year in 2011-2013. Although health care providers incur substantial cost in caring for the uninsured, the bulk of their costs are compensated through a web of complicated funding streams, financed largely with public funds from the federal government, states and localities. This brief estimates the level of public funding that was paid to help offset providers’ uncompensated care costs for the uninsured in 2017. To conduct the analysis, we rely on several secondary data sources including government budget appropriations and expenditure data for major public programs that provided funds to cover the cost of care for the uninsured, as well as analyses of secondary data sources completed by others. Key findings include:

- Nationally, at least $33.6 billion in public funds were paid to providers to help defray providers’ uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured in 2017.

- The federal government accounted for an estimated $21.7 billion, or nearly two-thirds of the public funding sources examined, most of which was through the Veterans Health Administration or Medicaid; providing $11.9 billion, states and localities made up the balance, primarily through indigent care and public assistance programs.

- Comparing the level of public funding to our estimate of total uncompensated care costs for the uninsured ($42.4 billion per year in 2015-2017), we calculate that in the aggregate nearly 80.0 percent of providers’ uncompensated care costs were offset by government payments designed to cover these costs.

Given the rise in the number of the uninsured since 2017, provider uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured have likely increased. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of uninsured grew by an estimated 1.5 million. In addition, with the economic toll brought on by the pandemic, the nation’s uninsured rate may have continued to climb in 2020. With the increase in uninsurance since 2017, provider uncompensated care also likely increased. As policymakers undertake efforts to expand coverage and assess the financial impact of the pandemic, understanding uncompensated care costs and the adequacy of public funding to help defray these costs can help direct policies targeted to the uninsured. With substantial public funding of uncompensated care, government costs associated with increases in coverage could be offset in part by savings in other parts of the public ledger.

Introduction

Uninsured people use less care than their insured counterparts, but when they do use care and cannot pay for it themselves, the cost of that care is uncompensated. Providers may absorb these costs as bad debt or tap into funding sources designed to cover some of the costs. However, these funding sources may be inefficient or may not target funds to providers with the most uncompensated care, which can leave uninsured people with bad debt, credit issues, or even bankruptcy.

Over the years, the federal government, states, and localities have devoted considerable resources to pay providers for care they provide to uninsured patients through several public program efforts (e.g., Veterans Health Administration and state and local indigent care programs) and also through direct financial support (e.g., Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments).

The economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has potentially led to millions more people in the United States being uninsured. In addition to posing challenges to these individuals’ ability to access needed health care and be protected from medical debt, rising uninsured rates could exacerbate issues with uncompensated care costs associated with providing health care to the uninsured.

In this brief, we examine government funding streams that were available to help providers defray the costs of providing medical services to the uninsured in 2017. Specifically, building on previous analyses, we use government program data and appropriations information and other data to estimate the level of public funds paid in 2017 to help offset providers’ uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured. This study complements our analysis that estimates the total cost of uncompensated care for uninsured people, using an alternative approach to estimate specific sources of funding for uncompensated care.1 We compare the total amount estimated in this analysis to our 2017 estimate of the total cost of care for uninsured people to assess the extent to which government funding defrays the uncompensated care costs for uninsured people.

Methods

We use publicly available program data and appropriations information and other secondary data to estimate the level of public funds paid in 2017 to help offset providers’ uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured. Specifically, we examine the following government funding sources: the Veterans Health Administration, the Medicaid program (namely, Medicaid DSH and uncompensated care pool payments), state and local indigent care programs, state and local public assistance programs, the Indian Health Service, and community health centers. For government funding tied to individual patients, the estimates reflect payments various programs made for direct medical care and services for uninsured people including inpatient care, outpatient care, behavioral health serves and prescription drugs. Non-medical related program activities (e.g., costs associated with facilities and administration) are not included. We also excluded uncompensated care costs associated with long-term care services. We then compare this level of estimated public funding to our estimate of the cost of uncompensated care provided to uninsured people in 2017, which was generated using data from the Medical and Expenditure Panel Survey.

Although we include major sources of public funding, we acknowledge that we do not account for all available government funding streams to help provide care for the uninsured.2 While this leads us to underestimate the level of available public funds for uncompensated care, previous analysis indicates that these sources account for a relatively small share of public funds for uncompensated care. To the extent possible, we tried to match services and payments we included with those contained in our recent analysis that estimated the level of uncompensated care costs for the uninsured. This was done so we could compare the extent to which government funding defrays the uncompensated care costs for uninsured people, but we acknowledge that the alignment is likely imperfect.

Another limitation to the analysis is that we do not account for private funding sources that are available to help pay for care received by the uninsured such as care provided to the uninsured by philanthropic organizations or by private physicians or private funds that flow through government-funded programs, such as prescription drug rebates.

These estimates rely on available information on program budgets as well as a series of supported assumptions about to what extent funds are directed to cover the cost of care for uninsured people. Details on the different data sources, the assumptions, and the process for estimating the level of government funding can be found in the technical appendix.

Findings

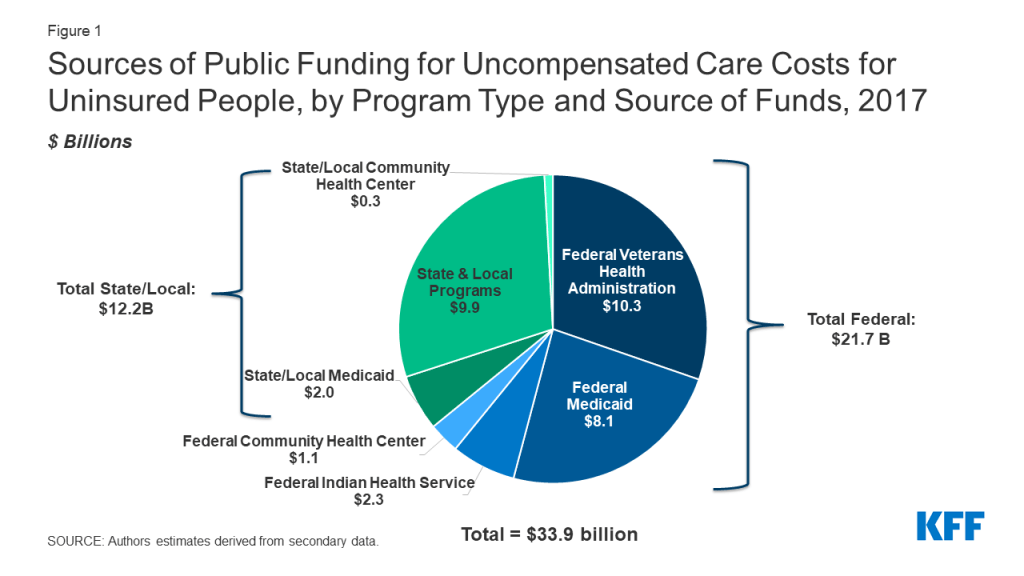

In the aggregate, we estimate that government payments to offset the cost of uncompensated care for the uninsured totaled $33.6 billion in 2017 (Figure 1 and Table 1). The federal government contributed nearly two-thirds of these payments, an estimated $21.7 billion. States and local government payments accounted for the remaining amount, $11.9 billion.

The Veterans Health Administration was the single largest government payment source, spending an estimated $10.3 billion in caring for the uninsured in 2017, all of which was federal funds (Table 1). With estimated spending totaling $9.8 billion, funding provided through the Medicaid program followed closely. Medicaid payments to cover the cost of care for the uninsured were split between DSH payments ($4.4 billion) and uncompensated care pool payments ($5.4 billion). The federal government accounted for more than four-fifths of this Medicaid funding, reflecting states’ use of alternate financing arrangements to finance their share of DSH and uncompensated care pool funds.3

Through public assistance and indigent care programs, states and localities spent an estimated $9.9 billion on caring for the uninsured. The bulk of these payments, $7.7 billion, came from tax appropriations for indigent care programs. An estimated $2.2 billion was spent through state and local government public assistance programs.

Other federal programs examined were the Indian Health Service, which spent an estimated $2.3 billion on the uninsured (all federal funds), and community health centers which spent an estimated $1.3 billion, with $1 billion being federal payments and $0.3 billion state and local.

| Table 1: Estimate of Public Funding for Uncompensated Care Costs for Uninsured by Program Type and Funding Sources Examined, 2017 ($Billions) | |||

| Program | Funding by Program by Level of Government ($Billions) | ||

| Federal | State/Local | Total | |

| Total Estimated Public Funding for UCC Costs for Uninsured by Payment Sources Examined | $21.7 | $11.9 | $33.6 |

| Veterans Health Administrationa | $10.3 | NA | $10.3 |

| Medicaid Programb | $8.1 | $1.7 | $9.8 |

| UCC Pool Payments | $4.6 | $0.8 | $5.4 |

| DSH Payments | $3.5 | $0.9 | $4.4 |

| State and Local Programs | NA | $9.9 | $9.9 |

| State/Local Tax Appropriations for Indigent Programsc | NA | $7.7 | $7.7 |

| State/Local Public Assistanced | NA | $2.2 | $2.2 |

| Indian Health Servicee | $2.3 | NA | $2.3 |

| Community Health Centersf | $1.0 | $0.3 | $1.3 |

| NOTES:a U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. (2019). “Volume II Medical Programs and Information Technology Programs Congressional Submission FY 2019 Funding and FY 2020 Advance Appropriations.” http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Expenditures.asp; Huang, G., Muz, B., Kim, S., & Gasper, J. (2018). “2017 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Use of Health Care.” Westat. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/SOE2017/VA_Enrollees_Report_Data_Findings_Report2.pdf.b Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2018, December) “MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book.” https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/December-2018-MACStats-Data-Book.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2019, July). “Medicaid States’ Use and Distribution of Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO-19-603. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/700378.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2014, July). “Medicaid Financing States’ Increased Reliance on Funds from Health Care Providers and Local Governments Warrants Improved CMS Data Collection.” Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO-14-627. https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/665077.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2015, March 13). “Medicaid Financing: Questionnaire Data on States’ Methods for Financing Medicaid Payments from 2008 through 2012.” GAO-15-227SP. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-15-227sp;MACPAC. (2019, March). “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Note the link to this issue brief is no longer publicly available but formerly accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf.c Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019, December). “National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA).” https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.d Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019, December). “National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA). ”https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.e U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Indian Health Service. (2018). “Indian Health Service Budget Submission Fiscal Year 2019 Congressional Justification.” https://www.ihs.gov/sites/budgetformulation/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/FY2019CongressionalJustification.pdf.f U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA), Bureau of Primary Health Care. (2017). “2017 Health Center Data.” https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds2017/datacenter.aspx?q=tall&year=2017&state=.SOURCE: Authors’ estimates derived from secondary data. | |||

Government payments substantially offset the cost of uncompensated care for the uninsured. In other recent work, we estimated uncompensated care costs for the nation’s uninsured averaged $42.4 billion per year in the 2015-2017 time period. Comparing this estimate to our estimate of government payments for uncompensated care in 2017 ($33.6 billion), public dollars cover nearly 80 percent of providers’ costs of caring for the uninsured.

The remaining share of uncompensated care (about 20 percent) may be covered by private sources, provider charity, or possibly transferred to other payers in the health care system. While, overall, government funding offsets nearly four-fifths of provider uncompensated care costs, it does not pay for all of these costs. Based on our estimates, about $8.8 billion is not covered by public dollars included in this analysis. Some of this remaining share may be accounted for by public sources not considered in this analysis, though in earlier analysis we estimate those amounts to be relatively small. Private funding sources (e.g., workers compensation, provider charity and philanthropic organizations), which we did not consider here, may also cover some of the residual share. Some of it may be also be paid for by the privately insured through increased health insurance premiums. The extent to which providers shift costs associated with shortfalls in Medicare and Medicaid payments and caring for the uninsured to private payers has been a long-standing health policy question and remains unsettled.4 While limited research has been conducted on provider cost shifting to pay for charity care associated with the uninsured,5 considerable work has examined whether hospitals charge private payers more because of shortfalls in public payments. Evidence on this question is mixed, showing that provider’s ability to do so is largely based in market power, cost shifting occurs at a relatively low rate, and when it occurs it does so well below a “dollar for dollar” shift.6

Even if we assume, however, that all the $8.8 billion spending on the uninsured not covered by public dollars was passed to the privately insured, the effect on premiums would be small. According to the National Health Expenditures Account, spending on private health insurance premiums totaled $975.5 billion in 2017, so uncovered spending on the uninsured accounted for less than 1 percent total spending on health insurance premiums.

Looking Ahead

Even with the significant coverage expansion afforded by the ACA, provider uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured remain substantial. In other recent work, we estimate that these costs averaged $42.4 billion each year in 2015-2017. At the same time, as reported here we find that the government covers the vast majority of uncompensated care costs; we calculate that nearly 80 percent of these costs were compensated with public funding.

Importantly, though, our analysis examined providers’ uncompensated care costs and sources of public funding in the aggregate, not at the individual provider level. The federal government, states and localities support multiple programs designed to help offset provider uncompensated care costs, and targeting of payments made under these varied programs has been a longstanding issue. Thus, some providers may incur costs treating the uninsured and receive little to no compensation.

The level of provider uncompensated care is far from static. Since 2017, the level of uninsurance has increased. Between 2017 and 2019, the number of the uninsured grew by 1.5 million and may have continued to increase in 2020 due the economic downturn caused by COVID-19. So, in all likelihood, provider uncompensated care costs have also increased since 2017.

Apart from rising uninsurance, changes to government payments to cover uncompensated care costs have occurred since 2017, and more are scheduled. Beginning in in fiscal year 2020, for example, the distribution of Medicare hospital uncompensated care payments changed so that hospital uncompensated care levels rather than Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) days are used to allocate these payments. Estimated to total about $8.4 billion each year, this Medicare policy change provides a substantial new funding source to help offset providers’ uncompensated care costs associated with the uninsured.7 On the other hand, sizable reductions in federal Medicaid DSH allotments are scheduled. Under current law, cutbacks in federal funding totaling $8 billion each year are set to start fiscal year 2024 and run to fiscal year 2027. As policymakers undertake efforts to expand coverage and assess the financial impact of the pandemic, understanding uncompensated care costs and the adequacy of public funding can help direct policies targeted to the uninsured. With substantial public funding of uncompensated care, government costs associated with increases in coverage could be offset in part by savings in other parts of the public ledger.

Teresa A. Coughlin and Haley Samuel-Jakubos are with The Urban Institute. Rachel Garfield is with KFF.

Appendix

Technical Appendix

In this appendix, we provide a more detailed description of data sources, assumptions, and limitations used in the analysis. The discussion is arranged by program funding source and level of spending.

As mentioned in the brief, we rely on government program data and appropriations information and other secondary data to estimate the level of public funds paid in 2017 to help offset providers’ uncompensated care costs associated with caring for the uninsured. Specifically, we examine the following funding sources: Veterans Health Administration, Medicaid DSH payments, Medicaid uncompensated care pool payments, state and local indigent care programs, and state and local public assistance programs, Indian Health Service, and community health centers.8 For direct patient payments, the estimates reflect payments made for direct medical care and services only;9 they do not include spending on non-medical related program activities (e.g., costs associated with facilities and administration). More specifically, we excluded costs associated with medical facilities, medical support and compliance, enabling services (e.g., outreach, education, community health workers, etc.), as well as long-term care services and supports.

These estimates are based on available information on program budgets as well as a series of supported assumptions about to what extent funds are directed to cover the cost of care for uninsured people. As such, there is uncertainty in these estimates.

Veterans Health Administration. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides care to over 9 million veterans enrolled in the VA health care program. In 2017, the VHA spent $51.0 billion on direct medical care for veterans, which included direct medical care obligations used to support inpatient care and outpatient care, as well as dental care, mental health care, prosthetics and rehabilitation care. A 2017 national survey of VHA enrollees found that 20.2 percent of VHA enrollees lacked health coverage. Assuming that uninsured VHA enrollees incur costs proportionate to their share of the patient population, we apply the percent of uninsured VHA enrollees to the direct medical care spending to estimate that total VHA spending on care for the uninsured was $10.3 billion in 2017, all of which was federally funded (Appendix Table 1). This estimate may be an undercount if uninsured patients incur a larger share of costs relative to their share of the VHA patient population.

| Appendix Table 1: Estimated Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Appropriations/Obligations Spent on Medical Care for the Uninsured, 2017 ($Billions) | ||

| VHA Appropriations for Direct Acute Medical Care Servicesa | $51.0 | |

| Percent of VHA Users with No Public or Private Health Insuranceb | 20.2% | |

| Estimated Direct Medical Care Spending for Uninsured | $10.3 | |

| NOTES:a Estimate of VHA appropriations expenditures devoted to direct medical care services is derived from final FY 2017 national VHA budget: inpatient care ($10.7 billion) + outpatient (ambulatory) care ($29.3 billion) + dental care ($1.0 billion) + mental health care ($6.1 billion) + prosthetics ($3.2 billion) + rehabilitation care ($0.7 billion) = $51.0 billion. Final direct medical budget appropriations for inpatient and outpatient services includes those discretionary and mandatory obligations associated with medical services and community care. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. (2019). “Volume II Medical Programs and Information Technology Programs Congressional Submission FY 2019 Funding and FY 2020 Advance Appropriations.” http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Expenditures.asp.b Huang, G., Muz, B., Kim, S., & Gasper, J. (2018). “2017 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Use of Health Care.” Westat. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHPOLICYPLANNING/SOE2017/VA_Enrollees_Report_Data_Findings_Report2.pdf.SOURCE: Authors’ estimate based on U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs expenditures data: http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Expenditures.asp. | ||

Medicaid Program. Apart from base payments paid to hospitals, the Medicaid program also makes supplemental payments to hospitals, some of which can be targeted to help pay for uncompensated care hospitals render to the uninsured. As set out in a 2019 report by MACPAC, Medicaid makes two types of supplemental payments that are designed, at least in part, to support uncompensated care costs hospitals incurring in caring for the uninsured: disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments and uncompensated care pool payments.10

Medicaid DSH payments. Required by federal law, Medicaid DSH payments are intended to help hospitals that serve a high or disproportionate share of Medicaid and low-income patients. DSH payments can be used not only to cover the unpaid cost of caring for uninsured patients but also can help offset Medicaid shortfall—that is, the difference between a hospital’s cost of providing care to a Medicaid patient and the Medicaid payment received for providing care. Within broad federal guidelines, states decide on what basis they allocate DSH payments among hospitals.

In 2017, Medicaid DSH payments to hospitals totaled $12.1 billion, with the federal share totaling $6.9 billion; the state share, $5.2 billion.11 To estimate what portion of these payments were available to help defray hospitals’ uncompensated care costs for the uninsured, we made several assumptions. First, we assumed that 50 percent of DSH payments went to cover uncompensated care costs for uninsured patients and 50 percent went to offset shortfalls in Medicaid base payments. Limited information is available on how DSH funds are actually allocated. To our knowledge the most recent available information is 2019 work done by MACPAC which used 2014 DSH audit statements to examine on what basis DSH payments are distributed. MACPAC reported that nationally, in 2014, 69 percent of DSH hospital payments went to help offset the cost of caring for uninsured patients, and 31 percent went to cover Medicaid payment shortfall.12 Owing to the ACA coverage expansion, between 2014 and 2017, the number of uninsured declined while the number of Medicaid enrollees increased. Because of this decline, for this analysis we assumed that states adjusted their DSH allocations to account for these shifts in insurance coverage. If states in 2017 paid out less than 50 percent of Medicaid DSH payments to help defray uncompensated care costs, we overstate the availability of these payments to cover unpaid costs of uninsured patients.13 Alternatively, if states allocated more than 50% of their DSH payments to cover uncompensated care costs, we understate availability.

Second, we made assumptions about what share of Medicaid DSH payments represent new funding available to hospitals to help cover uncompensated care costs for the uninsured. For many years states have relied on provider taxes, inter-governmental transfers (IGTs), certified public expenditures (CPEs) and other financing mechanisms to finance their share of DSH payments rather than using revenue from state general funds, which is generally the source of funding for the state Medicaid share. Data collected by the US. General Accountability Office for state fiscal year 2012 (the most recently available information to our knowledge) found that, nationally, 63.9 percent of the state share of DSH payments used revenues from provider taxes, IGTs and similar funding types for financing; the balance of the state share (36.1 percent) of DSH payments was financed with state funds such as state general revenues.

To account for these alternative financing sources, we assumed that the state share of DSH payments raised by provider taxes, IGTs and like financing was the same in 2017 as it was in 2012. We further assumed that the state share of DSH payments financed with these alternative financing sources did not represent new funds to the hospitals. In many instances, hospitals supply the money to fund the alternative financing sources that states then used to pay the state share of DSH payments. In contrast, we assumed that the state share of the DSH payments financed with state general funds did represent new funds available to hospitals to help pay for the unpaid costs of caring for the uninsured. We similarly assumed that the entirety of the federal share of DSH payments represented new funding to hospitals available to defray the unpaid costs for the uninsured. Applying these assumptions, we estimate that $1.9 billion of the state share of DSH payments (.36 x $5.2 billion) in 2017 represents new funding to hospitals, of which 50 percent ($0.9 billion) went to help cover uncompensated care costs for the uninsured. Similarly, we estimate that 50 percent of the full federal share of DSH payments (half of $6.9 billion or $3.5 billion), were paid to hospitals to help cover uncompensated care costs for the uninsured (Appendix Table 2). Combining the federal and state share we estimate that in 2017 $4.4 billion in Medicaid DSH payments were directed to hospitals with the goal of helping to defray the uncompensated care costs of the uninsured.

| Appendix Table 2: Estimate of Medicaid Supplemental Payments Available to Fund Uncompensated Care Costs for Uninsured, 2017 ($Billions) | |||

| Potentially Available Funding ($Billions) | |||

| Federal | State/Local | Total | |

| Estimated Medicaid Funding for Uninsured | $8.1 | $1.7 | $9.8 |

| DSH Paymentsb | $3.5 | $0.9 | $4.4 |

| UCC Pool Paymentsa | $4.6 | $0.8 | $5.4 |

| NOTES:a MACPAC. (2019, March). “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Note the link to this issue brief is no longer publicly available but formerly accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2014, July). “Medicaid Financing- States’ Increased Reliance on Funds from Health Care Providers and Local Governments Warrants Improved CMS Data Collection.” Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO-14-627. https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/665077.pdf.b Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2018, December) “MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book.” https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/December-2018-MACStats-Data-Book.pdf; U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2019, July). “Medicaid- States’ Use and Distribution of Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO-19-603. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/700378.pdf; GAO. (2014, July). “Medicaid Financing States’ Increased Reliance on Funds from Health Care Providers and Local Governments Warrants Improved CMS Data Collection.” Report to Congressional Requesters. https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/665077.pdf.SOURCE: Authors’ estimates using secondary data sources. | |||

Medicaid Uncompensated Care Pool Payments. In fiscal year 2017, nine states supported uncompensated care pool payments through Medicaid Section 1115 demonstrations.14 Combined, $8.0 billion in pool payments were made in 2017 across the nine states, about $4.6 billion in federal funds and $3.4 billion in state funding.15 The specifics of how pool payments are made and on what basis vary state to state; California’s Global Payment Program (accounting for nearly half, $3.8 billion, of all pool payments in 2017), for example, supported payments to cover the uninsured costs of care with a particular emphasis on providing care in appropriate, cost-effective settings.

Similar to state financing of Medicaid DSH payments, a large part of the state share of uncompensated care pool payments is financed with funds from providers and local governments through provider taxes and IGTs. According to the U.S. General Accounting Office, nationally, providers and local governments provided 78 percent of the state share of non-DSH supplemental payments in 2012.16 Consistent with our adjustment for state use of alternative funding sources in financing DSH payments, we assumed that the state share of uncompensated care pool payments paid for with these alternative sources did not represent new funds to providers. We further assumed that the state share of uncompensated care pool payments (22 percent) financed with state funds did represent new funds to providers. We also assumed that the entirety of the federal share of uncompensated care pool payments represented new funding to providers. Applying these assumptions, we estimate that $0.8 billion of the state share of uncompensated care pool payments (.22 x $3.4 billion) in 2017 represents new funding to providers. Combining this with the full federal share of uncompensated care pool payments ($4.6 billion), we estimate that $5.4 billion in Medicaid uncompensated care payments were paid to providers to help cover the unpaid costs of the uninsured in 2017 (Appendix Table 2). Between Medicaid DSH and UCC payments, we estimate that Medicaid paid $9.8 billion to help cover the cost of caring for the uninsured, with $8.1 billion in federal funds and $1.7 billion in state funds.

State and Local Tax Programs and Public Assistance. State and local governments provide funds to cover some uncompensated care costs through subsidies to providers and funding of public assistance and indigent care programs. We estimate state and local tax expenditures and spending on public assistance that goes toward uncompensated care based on the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) for 2017. There is no comprehensive information available on how these funds were used or what share went toward care for the uninsured. Mirroring our previous work in this area, we assume that 50 percent of these funds support uncompensated care costs.

Specifically, we calculated state and local tax appropriations to cover the cost of uncompensated care for the uninsured based on funds reported as “Other state and local programs” that went toward the following services: hospital ($15.3 billion), physician and other clinical services ($0.08 billion), other professional services ($0.01 billion), and prescription drugs ($0.01 billion). We assume half of these total funds support uncompensated care, leading to an estimated $7.7 billion in payments made by state and local tax appropriations in 2017 (Appendix Table 3).

For state and local public assistance spending to cover the cost of uncompensated care for the uninsured we use funds reported as “general assistance” that went toward the following services: hospital ($2.6 billion), physician and other clinical services ($0.8 billion), other professional services ($0.1 billion), and prescription drugs ($0.9 billion). We assume half of these total funds supported uncompensated care costs, leading to an estimated $2.2 billion in state and local public assistance paid in 2017 (Appendix Table 3).

| Appendix Table 3: Estimate of State and Local Tax Programs and Public Assistance Programs for Medical Care for Uninsured, 2017 ($Billions) | |

| Estimated State/Local Spending on the Uninsured | $9.9 |

| State/Local Tax Appropriations for Indigent Programs, 2017a | $7.7 |

| State/Local Public Assistance Spending on the Uninsured, 2017b | $2.2 |

| NOTES:a State and local appropriations for indigent programs reflect those public payments designated as “other state and local programs” including total hospital expenditures ($15.3 billion) + total physician and other clinician services expenditures, other professional services expenditures, and prescription drug expenditures (collectively amount to roughly $0.1 billion). Note that we assume that half of the public payments tied to these expenditures support uncompensated care.b State and local public assistance reflect those public payments designated as “general assistance” including total hospital expenditures ($2.6 billion) + total physician and other clinician services expenditures ($0.8 billion) + total other professional services expenditures ($0.1 billion) + total prescription drug expenditures ($0.9 billion). Note that we assume that half of the public payments tied to these expenditures support uncompensated care.SOURCE: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) CY 2017: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical. | |

Indian Health Service. In 2017, the Indian Health Service (IHS) spent $3.4 billion providing direct medical care services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. This included spending on inpatient hospital services and services provided in health clinics (e.g., outpatient care and prescription drugs) as well as referred care services which supports the delivery of health care services not available in IHS-operated facilities. To estimate how much of this spending went to care for uninsured American Indians and Alaska Native, we deducted the $1.1 billion IHS received from third-party payers from total medical spending ($3.4 billion), and estimate that IHS spent $2.3 billion caring for the uninsured in 2017, all of which was federally funded (Appendix Table 4).

| Appendix Table 4: Estimate of Indian Health Service Spending for Medical Care for Uninsured, 2017 ($Billions) | |

| Estimated Appropriations Spent on Uninsured | $2.3 |

| IHS Spending for Medical Care Services, 2017a | $3.4 |

| Collections from Public and Private Insurance | <$1.1> |

| NOTE:a IHS spending for medical care services includes hospital and health clinic services (e.g., inpatient care, ambulatory care, labs, pharmacy, etc.), dental services, mental health, alcohol and substance abuse services, and purchased/referred care services.SOURCE: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Indian Health Service FY 2019 Performance Budget Submission to Congress: https://www.ihs.gov/sites/budgetformulation/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/FY2019CongressionalJustification.pdf. | |

Community Health Centers. Administrated by the federal government, the Community Health Center (CHC) program comprises 1,373 health centers which, nationwide, provided health care services to 27 million individuals. National program data report that CHCs spent $15.5 billion on direct medical care and other clinical care services (e.g., dental, mental health, and prescription drugs) in 2017.17 Patient program revenue data show that 16.9 percent of total annual charges in 2017 were attributed to self-paying patients. Applying the share of charges attributed to self-pay patients to total spending on medical spending, we estimate that CHCs spent $2.6 billion in caring for the uninsured in 2017 (Appendix Table 5). We then deducted total collections received from self-pay patients ($1.1 billion) and funding received from private grants and contracts for the uninsured ($0.2 billion) and estimate that CHCs spent $1.3 billion in direct care for the uninsured.

Finally, to estimate the share of CHC spending on the uninsured by type of funding source (federal, state, or local), we multiplied the estimated level of CHC spending on the uninsured ($1.3 billion) by the share of total CHC program spending by federal, state and local sources. In 2017, program data show that the federal government provided 64 percent of overall CHC program funding, and state and local governments 24 percent.18 Applying these percentages to total estimated CHC spending on the uninsured, we estimate that the federal government paid $1.0 billion and federal and state and local governments $0.3 billion (Appendix Table 5).

| Appendix Table 5: Estimated Community Health Centers Uncompensated Care Costs for Uninsured, 2017 ($Billions) | ||

| Estimated Uncompensated Care Spending on Uninsured | $1.3 | |

| Medical and Other Clinical Services Spendinga | $15.5 | |

| Share of Total CHC Spending for Self-Pay Patientsb | 16.9% | |

| Share of Medical and Other Clinical Services Spending for Self-Pay Patients | $2.6 | |

| Payments made by Self-Pay Patients | <$1.1> | |

| Private Payments for Uninsuredc | <$0.2> | |

| NOTES:a CHC medical costs for 2017 included medical care ($9.4 billion) and other clinical services ($6.1 billion).b CHC patient charges in 2017 totaled $27.7 billion, 16.9 percent ($4.3 billion) were incurred by self-pay patients.c Private payments includes funding from foundation/private grants and contracts.SOURCE: Bureau of Primary Health Care, HRSA, Uniform Data System, 2017 Health Center Data: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds2017/datacenter.aspx?q=tall&year=2017&state=. | ||

Endnotes

- The estimates in this brief include spending to cover both implicitly subsidized care (that is, the cost of care for an uninsured person with no identifiable source tied to that specific person) and care covered through alternative (non-health insurance) sources, such as payments to providers through the Indian Health Service or grants to Community Health Centers. ↩︎

- For example, we do not include funding from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program or the Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant Program. ↩︎

- The high share of federal funding is due to how states generally finance their share of these payments, which is through alternative financing sources such as provider taxes and intergovernmental transfers. See appendix for details. ↩︎

- See for example, Frakt, A.B. (2011). How Much Do Hospitals Cost Shift? A Review of the Evidence. The Milbank Quarterly, 89 (1); 90-130. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00621.x;Gruber, J. & Rodriquez, D. (2007). How much uncompensated care do doctors provide? J. of Health Economics 26, 1151-1169. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.08.001;Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing. (n.d.). Colorado Cost Shift Analysis. https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/hcpf/colorado-cost-shift-analysis. ↩︎

- One important exception to this is a study that showed that physicians provide negative to very limited uncompensated care to the uninsured. Gruber, J. & Rodriquez, D. (2007). How much uncompensated care do doctors provide? J. of Health Economics 26, 1151-1169. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.08.001. ↩︎

- The ability to cost shift depends upon several factors, one being relative market power between hospitals and health plans. So, in some cases hospitals with substantial market power may have the ability to negotiate higher payments from insurers in response to increases in uncompensated care costs. But, Frakt finds that the preponderance of the literature as of 2011 shows that cost shifting is one strategy hospitals can adopt to make up for payment shortfall but that others (e.g., cutting costs) may be even more important. Changes to the health care market since 2011 (e.g., increased provider integration and consolidation) could shift the dynamics between payors and hospitals, in turn affecting the extent of provider cost shifting. Frakt, A.B. (2011). How Much Do Hospitals Cost Shift? A Review of the Evidence. The Milbank Quarterly, 89 (1); 90-130. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00621.x ↩︎

- In our analysis, we did not consider Medicare uncompensated care payments because until 2020 these payments were focused on defraying providers’ Medicaid payment shortfall not on the uninsured. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019, August 2). “Fiscal Year (FY)2020 Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCH) Prospective Payment System (CMS-1716-F).” https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fiscal-year-fy-2020-medicare-hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-system-ipps-and-long-term-acute-0. ↩︎

- Unlike in our previous work on this topic, we do not include Medicare payments as a funding source for uncompensated care for the uninsured. While Medicare makes DSH and uncompensated care payments, in 2017 these payments were not directed to covering uncompensated care costs for the uninsured. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2016, August 2). “Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCH) Final Rule Policy and Payment Changes for Fiscal Year (FY) 2017.” https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-system-ipps-and-long-term-acute-care-hospital-ltch-final-rule. Specifically, in 2017 Medicare DSH payments were paid based on the level of a hospital’s Medicaid inpatient days, and Medicare uncompensated care payments were allocated based on a combination of the number of a hospital’s inpatient Medicaid days and the number of Medicare days for low-income Medicare patients who received Supplemental Security Incomes (SSI). In other words, in 2017 Medicare DSH and uncompensated care payments were largely directed at making up for the shortfall in Medicaid base payment, not uncompensated care for the uninsured. For more on this topic, see Stensland, J., Gaumer, Z.R., & Miller, M.E. (2016). Contrary To Popular Belief, Medicaid Hospital Admissions Are Often Profitable Because Of Additional Medicare Payments. Health Affairs, 35 (12), 2282- 2288. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0599. Importantly, beginning in fiscal year 2020 the way in which Medicare uncompensated care payments are distributed changed: Hospital uncompensated care levels (as reported in the Medicare cost report) rather than Medicaid and SSI days will be used to allocate Medicare uncompensated care payments, which are estimated to total about $8.4 billion. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2019, August 2). “Fiscal Year (FY)2020 Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCH) Prospective Payment System (CMS-1716-F).” https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fiscal-year-fy-2020-medicare-hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-system-ipps-and-long-term-acute-0. Another source of Medicare funding for uncompensated care for the uninsured that we included in previous work was Medicare Indirect Medical Education or IME payments which compensate teaching hospitals for the indirect costs of activities associated with medical teaching that add to the cost of treating Medicare patients. Similar to the distribution of Medicare DSH and uncompensated care payments in 2017, IME payments are paid out as a percentage add-on to a hospital’s inpatient Medicare payments and do not consider uncompensated care costs for uninsured in determining payment. The costs of uncompensated care for the uninsured is not part of the Medicare IME distribution formula. http://www.medpac.gov/-public-meetings-/meeting-details/september-2019-public-meeting. ↩︎

- See note 1. ↩︎

- In addition to DSH and uncompensated care pool payments, states can also make other Medicaid hospital supplemental payments. As identified by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) these are upper payment limit (UPL) payments, delivery system reform incentive (DSRIP) payments, and graduate medical education (GME) payments. MACPAC. (2019, March). “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Note the link to this issue brief is no longer publicly available but formerly accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf; Unlike DSH and uncompensated care pool payments, however, UPL, DSRIP and GME payments are not intended to help hospitals cover the unpaid costs of the uninsured but rather are designed to support other purposes. For example, UPL payments are meant to supplement Medicaid hospital fee-for-serve base payments that in recent years many states have reduced or frozen. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2019, July). “Medicaid States’ Use and Distribution of Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Report to Congressional Requesters. GAO-19-603. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/700378.pdf. DSRIP payments, which are made available under some Medicaid Section 1115 demonstrations, are not intended to pay for medical services but rather are designed to help providers (hospitals and others) undertake infrastructure and other investments to improve access to and quality of care provided to Medicaid enrollees. Finally, GME payments are designed to support teaching hospitals in their efforts to train medical professionals, among other things. Given this, we do not include UPL, DSRIP and GME payments as funding for uncompensated care costs associated with the uninsured. ↩︎

- In addition to community-based acute care hospitals, Medicaid DSH payments are also paid to institutions for mental diseases or IMDs. To better align with our uncompensated care estimate based on the MEPS, which excludes individuals residing in institutions from the survey sample, we exclude IMD DSH payments from this analysis. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). (2018, December) “MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book.” https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/December-2018-MACStats-Data-Book.pdf. ↩︎

- States are statutorily required to submitting DSH audit data to CMS; at the time of MACPAC 2019 report 2014 was the latest year for which data were available. MACPAC. (2019, June). Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP June 2019. Chapter 2: Treatment of Third-Party Payments in the Definition of Medicaid Shortfall. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Treatment-of-Third-Party-Payments-in-the-Definition-of-Medicaid-Shortfall.pdf. ↩︎

- Increasingly, states have relied on Medicaid UPL payments to help cover the Medicaid shortfall. In 2017, states paid $12.9 billion in hospital UPL payments, higher than the $12.1 billion states paid in DSH in the year. MACPAC. (2019, March). “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Note the link to this issue brief is no longer publicly available but formerly accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf.Given the scale of state use of hospital UPL payments, it is plausible, though not certain, that a sizable share of Medicaid DSH payments is targeted to cover unpaid costs of the uninsured. ↩︎

- The nine states: Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Kansas, New Mexico, Tennessee and Texas. MACPAC. (2019, March). “Medicaid Base and Supplemental Payments to Hospitals.” Note the link to this issue brief is no longer publicly available but formerly accessed at https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Medicaid-Base-and-Supplemental-Payments-to-Hospitals.pdf. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- In addition to Medicaid uncompensated care pool payments, the GAO study included UPL payments and other add on payments in its non-DSH supplemental payment category. Similar to DSH payments, we considered the category of other sources of funding (e.g., tobacco settlement funds) as state funds for non-DSH supplemental payments. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2015, March 13). “Medicaid Financing: Questionnaire Data on States’ Methods for Financing Medicaid Payments from 2008 through 2012.” GAO-15-227SP. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-15-227sp. ↩︎

- Note that we have excluded expenditures for enabling services such as outreach, case management, transportation services, as well as facility and non-clinical support services. Bureau of Primary Health Care, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). (n.d.) Uniform Data System, 2017 Health Center Data. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds2017/datacenter.aspx?q=tall&year=2017&state=. ↩︎

- At 12 percent, private sources accounted the rest of Community Health Center (CHC) funding. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). (n.d.). Health Center Program Data Table 9E. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national/table?tableName=9E&year=2017. ↩︎