Serious Illness in Late Life: The Public’s Views and Experiences

Overview

The U.S. population is aging, and with that shift comes new challenges in meeting the needs of older adults with serious health needs. In order to better understand the public’s expectations about later life and any efforts they’ve taken to plan for if they become seriously ill, the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a large scale, nationally representative telephone survey of 2,040 adults, including 998 interviews with people with recent experience with serious illness in older age, either personally or with a family member. For this survey, those who are seriously ill are older adults who have at least one of several chronic conditions and report functional limitations due to a health or memory problem. This comprehensive survey helps provide insight into the perspectives of the public at large as well as of older adults personally facing serious illness and their family members about how they view care in the U.S., steps they’ve taken to plan for becoming seriously ill in later life, and their current experiences with care and support for those with serious illness. It is the first in a series of surveys that will measure how these attitudes and experiences change over time.

Report: Serious Illness in Late Life: The Public’s Views and Experiences

Four infographics illustrate some of the survey’s main findings:

Executive Summary

The number of older Americans is growing rapidly. The share of adults 65 or older in the U.S. is expected to rise from 14.5 percent of the population in 2014 to 21.7 percent of the population by 2040.1 While medical advances have allowed many older adults to live longer, healthier lives, many are also living with multiple chronic conditions that are likely to lead to a slow deterioration over time. In the context of these demographic changes and the challenges arising from an older population with serious health needs, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) conducted a large scale nationally representative telephone survey of 2,040 adults, in order to better understand people’s expectations about later life and efforts they’ve taken to plan for if they become seriously ill. This survey will serve as a baseline and we will conduct future surveys to measure how these attitudes and experiences change over time. To learn more about the experiences of those with serious illness specifically, this survey included interviews with 998 adults who are either personally age 65 or older living with a serious illness, or have a family member who is or was before they recently died. For this survey, those who are seriously ill are older adults who have at least one of several chronic conditions and report functional limitations due to a health or memory problem such as difficulty preparing meals, shopping for groceries, taking medications, getting across a room, eating, dressing, bathing, or using the toilet. This broad definition not only includes people who are quite ill and in their last few months of life, but also those who may be earlier in their disease course who have many months or years yet to live.

New @KaiserFamFound survey examines the challenges facing Americans with serious illness late in life

The following are some of the key findings from the survey.

The public largely acknowledges some of the issues that can arise with serious illness in late life, but many people report that they have not yet taken steps to plan for if they become seriously ill themselves.

- Americans are generally aware that most people die after a period of worsening health rather than suddenly and think that problems affording medical care and support services are common for people in late life. Many are personally worried about these things affecting them when they are older if they become seriously ill, yet just about a third say they have talked with a family member about how they would pay for help if they became seriously ill and, more broadly, just about half say they are saving for retirement.

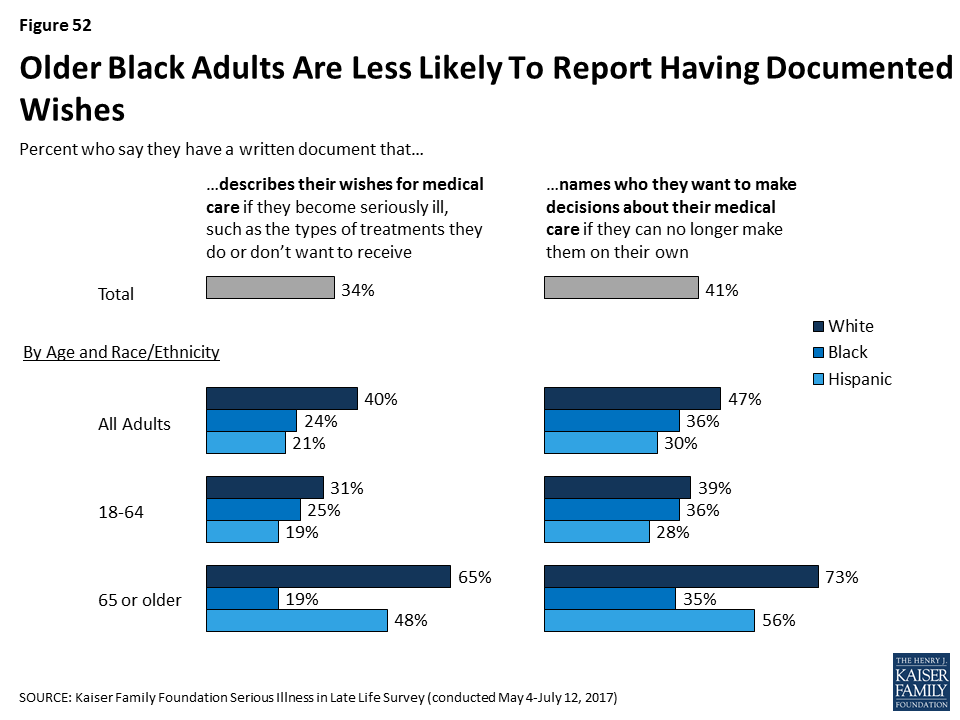

- People say a number of different aspects of life are important to them to maintain a good quality of life in older age, including making sure their medical wishes are followed, but more than half say they do not have a document that describes their wishes for care or names a person they would want to make medical decisions on their behalf. In fact, one-third (34 percent) say they have a written document outlining their wishes and four in ten (41 percent) say they have a written document designating someone to make medical decisions on their behalf. Older adults are much more likely than younger adults to say they have these types of documents. Discussions of these issues with family members are reportedly much more common than written documentation. Majorities, including among younger adults, report talking about at least one related issue with a family member, but some specific aspects of planning are discussed less often, such as finances, where someone would prefer to live, or what they would need to have a good quality of life.

- Most say they have not talked with a doctor or health care provider about their wishes, including among older adults and adults that report being in fair or poor health. For those that have written documents, few report sharing them with their doctors or other health care providers, leaving open the potential for uncertainty or confusion about what a person would want if seriously ill, even though they have gone to the effort of documenting their wishes.

Older adults with serious illness report a variety of challenges and some say they need help more often than they are getting.

- Older adults with serious illness and their family members say they face a variety of challenges, from being forgetful (71 percent), feeling depressed (56 percent), and having difficulty understanding medical instructions (48 percent), to having trouble with basic tasks like preparing meals (39 percent). Six in ten older adults with serious illness have someone constantly providing help with everyday tasks. Still, more than four in ten say they need help more often than they are getting, and some report difficulty getting the help needed (27 percent) or forgoing such help due to cost (18 percent).

- Having a loved one facing serious illness can be stressful for family members, and, while many say their personal needs are being met, some say they only sometimes get the help they need managing feelings of anxiety or sadness. Family members report helping their loved one with a variety of tasks, such as transportation (67 percent), everyday activities (57 percent), coordinating care across different doctors or clinics (55 percent), managing finances (43 percent), and medical-nursing tasks (42 percent). Those family members personally providing help are spending quite a bit of time on such tasks, but most of those who report helping with daily activities say they have someone that can give them a break when they need it. However, about one in five family members providing help say there is no one to give them a break, likely increasing the stress involved with caring for a loved one. Just over half of those helping with medical-nursing tasks say they received training from a nurse or other health professional on specific caregiving techniques, but even still, a large majority feel they were at least somewhat well trained to provide care.

For older adults with serious illness, those with documents outlining wishes for care are more likely to say their wishes have been followed and nearly all family members who have referred to these documents say they have been helpful in making decisions about their loved one’s care.

- Most family members of older adults with serious illness report their loved one has a document describing their wishes (60 percent) or a document naming someone to make medical decisions on their behalf (70 percent). Some family members say they have referred to this document and nearly all who have referred to it say it was helpful.

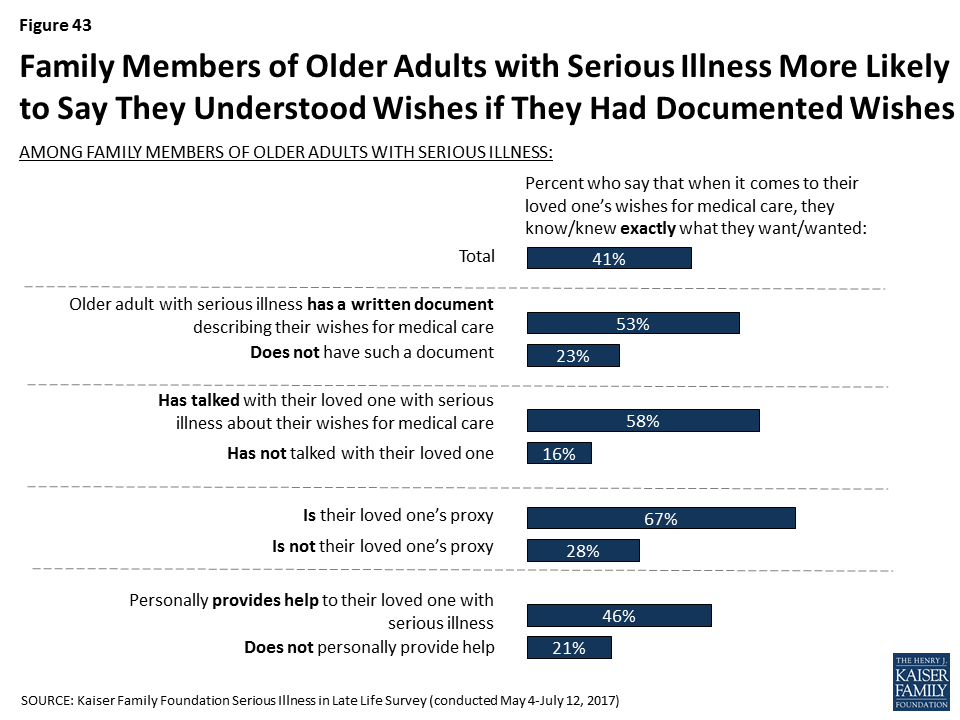

- Writing wishes down and talking about them appears to make a big difference in family members being confident they know what their loved one wants for their medical care. Family members who say their loved one has a written document outlining their wishes are more than twice as likely to say they know exactly what their loved one wants than those without such a document (53 percent versus 23 percent). And, family members who say they talked with their seriously ill loved one about their wishes are more than three times as likely than others to say they knew exactly what their loved one wanted (58 percent vs. 16 percent). In addition, older adults with serious illness and their family members are more likely to say their wishes for medical care are ‘very closely’ followed if they report having a document describing their wishes than if they don’t (70 percent vs. 54 percent).

Overall, much of the public rates the U.S. health care system poorly in terms of the care it provides to older people with serious health needs, but most of those who are currently experiencing serious illness themselves have more positive impressions.

- About half of the public overall (52 percent) rate the U.S. health care system fair or poor on the care it provides older people with serious health needs and 45 percent say there is not enough support available in their community for older people with serious illness.

- However, over half of older adults who themselves are dealing with serious illness say there is enough support available in their community and 60 percent rate the U.S. health care system’s care for seriously ill people as good, very good, or excellent. And, most older adults with serious illness and their family members who get paid help from a nurse or health care aide say the provider is well trained (89 percent) and rate the quality of the care provided as very good or excellent (63 percent).

Older black adults are much less likely than others to report having written documents outlining wishes or designating a health care proxy. People who are Hispanic are more apt to report financial challenges and uncertainty about late life and serious illness than black and white adults.

- Older black adults are much less likely than older people who are white or Hispanic in having written documents outlining wishes or designating someone to make medical decisions on their behalf, even after controlling for other demographic factors associated with having these documents. Just 19 percent of black adults ages 65 or older say they have a document describing their wishes and about a third (35 percent) have a document naming a health care proxy, compared to about half of older Hispanics and more than six in ten older whites who say they have either type of written document.

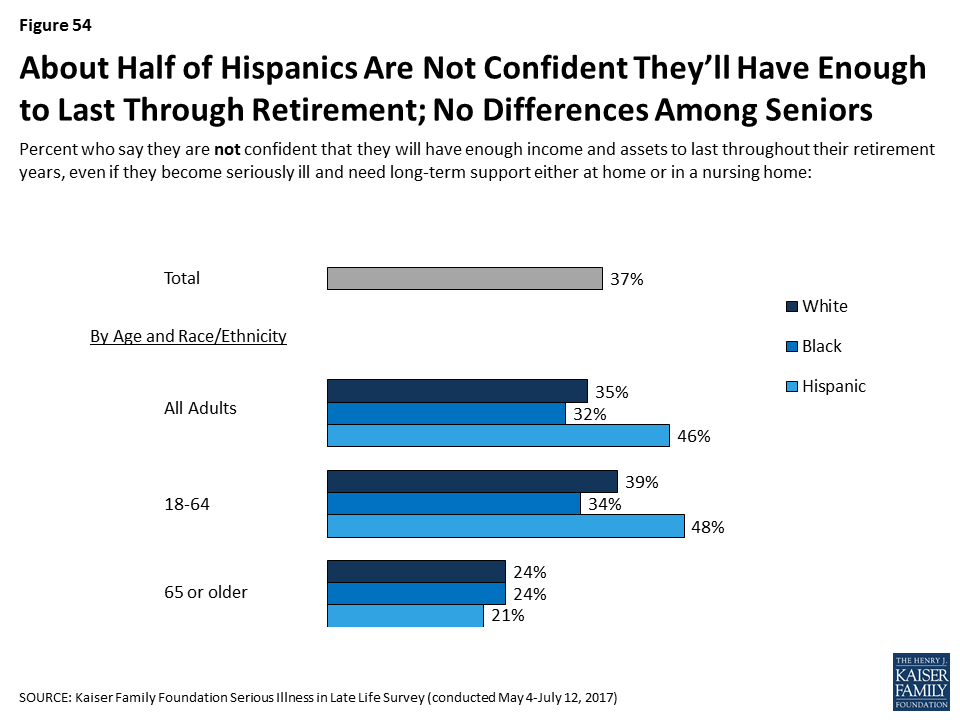

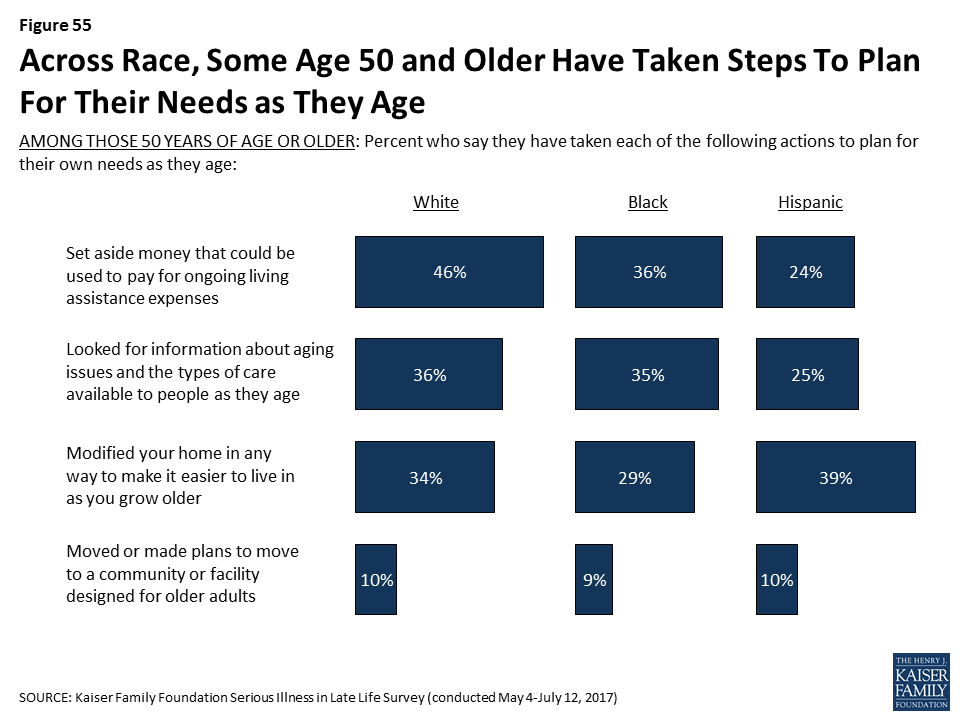

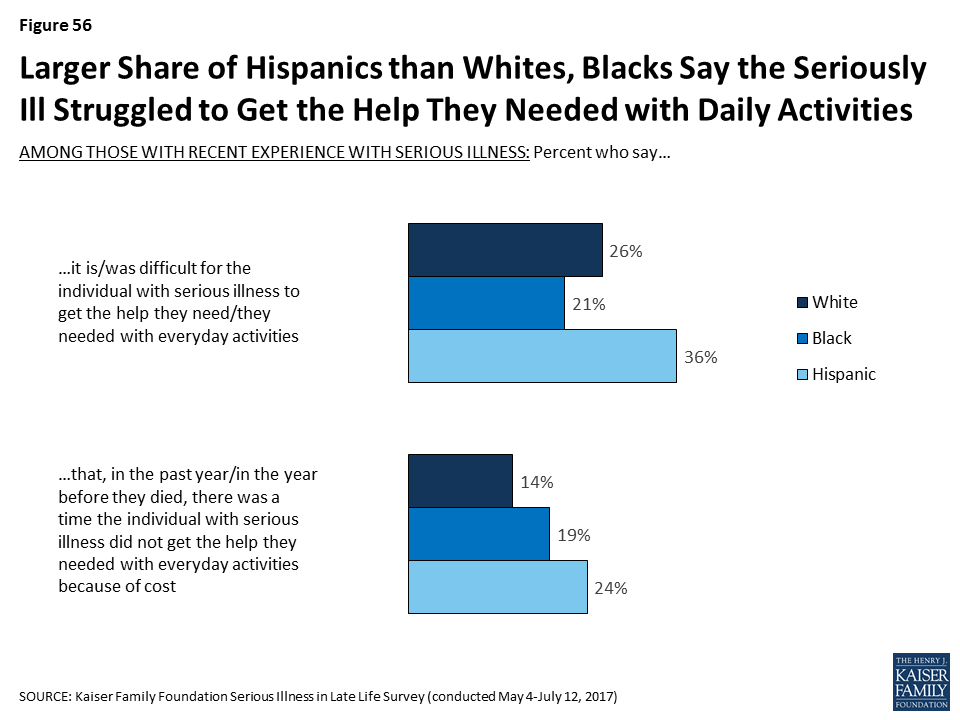

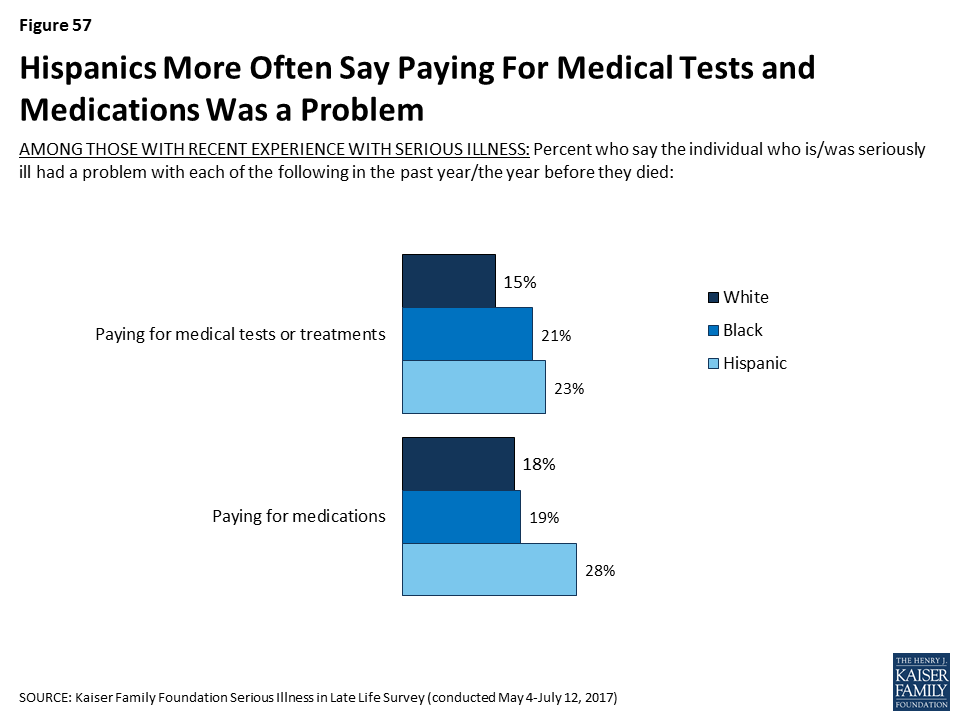

- Hispanic adults are more likely than white or black adults to report being worried about facing challenges when they are older such as affording medical care or support, housing issues, or leaving debts to their family. Further, about half of Hispanic adults are not confident they will have enough money or assets to last through retirement if they become seriously ill. This worry and lack of confidence carries over into reported actions taken to plan for retirement. Just a third of people who are Hispanic and not yet retired say they are saving for retirement, compared to half of black adults (49 percent) and six in ten white adults (60 percent). And, Hispanics 50 or older are less likely than others to say they have set aside money that could be used to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses. This theme continues among older adults with serious illness. Hispanics who are themselves dealing with serious illness or have a seriously ill family member are more likely to report that it was difficult to get the help they needed with everyday tasks, that they didn’t get needed help due to cost, and that they had trouble affording medications, tests, and treatments.

Introduction

The number of older adults is growing rapidly. The share of adults 65 or older in the U.S. is expected to rise from 14.5 percent of the population in 2014 to 21.7 percent of the population by 2040, and the number of people age 85 or older is expected to triple from 6.2 million in 2014 to 14.6 million in 2040.2 While medical advances have allowed many older adults to live longer, healthier lives, many are also living with multiple chronic conditions that are likely to lead to a slow deterioration over time.3 In the context of these demographic changes and the challenges arising from an older population with serious health needs, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) conducted a large scale nationally representative telephone survey of 2,040 adults, in order to better understand people’s expectations about later life and efforts they’ve taken to plan for the event they become seriously ill. In light of current efforts underway to improve the situations of those with serious illness and prepare for the aging population, this survey will serve as a baseline and we will conduct future surveys to measure how these attitudes and experiences change over time. To learn more about the experiences of those with serious illness, this survey included interviews with 998 adults who are either personally age 65 or older living with a serious illness, or have a family member who is or was before they recently died. Experts consider serious illness to be a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacts a person’s daily function or quality of life or excessively strains their caregivers. For this survey, those who are seriously ill are older adults who have at least one of several chronic conditions and report functional limitations due to a health or memory problem such as difficulty preparing meals, shopping for groceries, taking medications, getting across a room, eating, dressing, bathing, or using the toilet. This broad definition not only includes older people who are quite ill and in their last few months of life, but also those older people who may be earlier in their disease course who have many months or years yet to live. (For more details on how this survey defines serious illness, see Section 2 and the Methodology). A survey of this magnitude allows for analysis across age, race/ethnicity, health status, income, and other factors that may influence a person’s views and experiences with serious illness. This report summarizes the results from the survey and is organized as follows:

- Section 1 examines the public’s overall views of issues related to serious illness care, people’s perceptions of how the U.S. health care system meets the needs of older adults with serious illness, as well as the public’s awareness of the issues that can arise when someone is facing a serious illness, such as financial problems, access to support services and medical care, and housing issues.

- Section 2 covers the experiences and perspectives of those with experience with serious illness, either personally or with a family member, including the challenges they face, what types of care and support they are receiving and whether their needs are being met.

- Section 3 focuses on the steps the public has taken to plan for serious illness in later life, including the types of documents they may have created and concrete steps they have taken to prepare for aging or save for retirement, as well as the types of conversations that people are having with their loved ones and medical providers about their wishes and desires in the event they become seriously ill.

- Section 4 highlights some of the key areas where views and experiences differ for people who are black, Hispanic or white, although across many measures, their responses are similar.

In addition to the survey, this report also incorporates themes that emerged during focus groups with family members of older adults with serious illness that were conducted in February and March 2017 in Kansas City, MO, and Chattanooga, TN. The survey and focus groups were designed and analyzed by researchers at KFF and paid for by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. For more on how the survey or the focus groups were conducted, see the Methodology section.

Section 1: Views Of The Issue

Public’s Perceptions of People’s Last Years

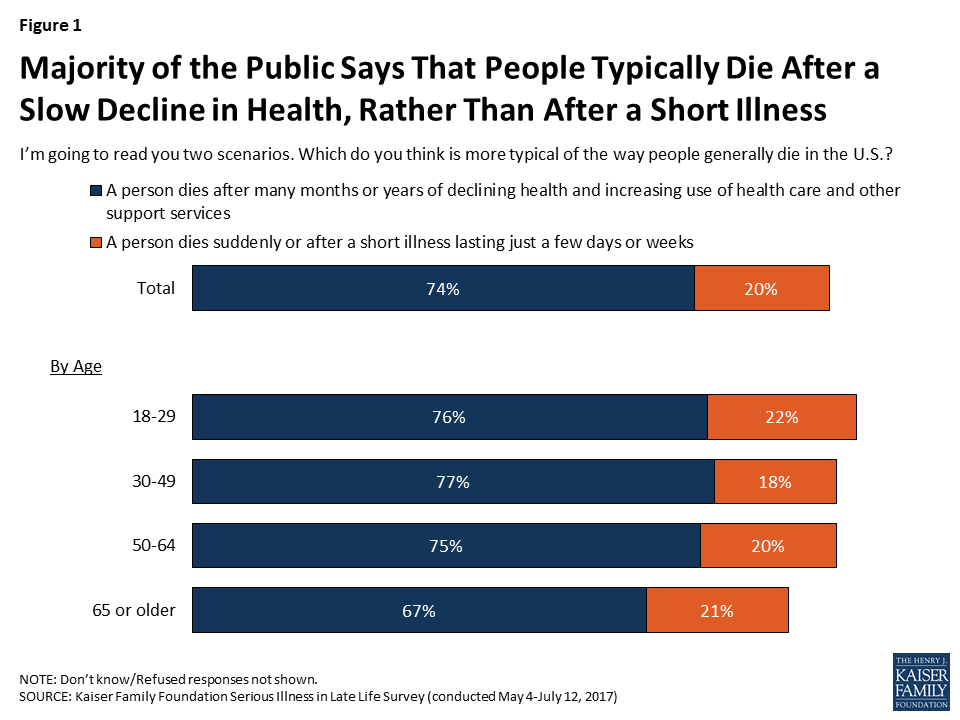

Due to medical advances and the ability to manage chronic conditions in older adults, more people are living longer and, rather than dying from acute episodes of illness, they are dying after long periods of sickness and declining health. The public is generally aware of this – most people (74 percent) are aware that people typically die after many months or years of declining health and after increasing use of health care and other support services, as opposed to dying suddenly or after a short illness lasting just a few days or weeks (20 percent). Interestingly, older adults are somewhat less likely to say that death comes after a slow decline than younger people.

As people live longer in varying states of health, many are faced with needing medical care or support services for longer periods than they may have expected, which can strain finances, families, and individuals themselves. Large majorities of the public say it’s common for people in their last few years of life to have difficulty paying for medical care (83 percent), support services (80 percent), and housing (76 percent), and that it’s common to have to move somewhere other than where they would like to be living (74 percent). Older people are somewhat less likely to say each of these things is common in later life.

Public Gives Mixed Ratings of U.S. Health Systems’ Care for Seriously Ill

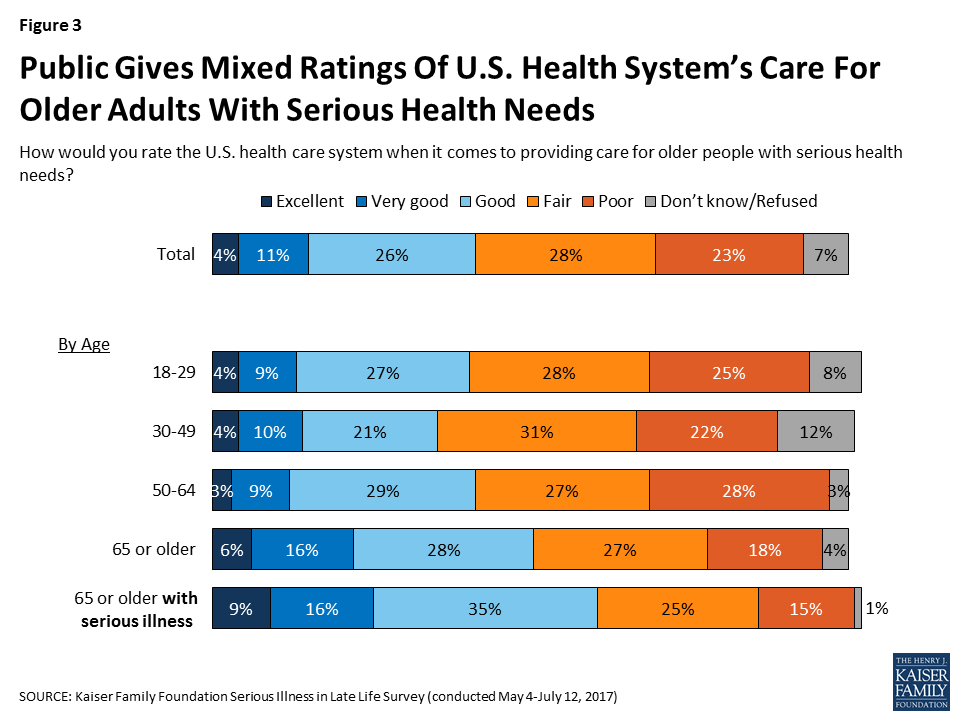

In terms of how the public views the care provided for older people with serious health needs, 52 percent rate the U.S. health care system fair or poor, while about a quarter rate it as good and 15 percent rate it as very good or excellent. Older adults are somewhat more likely to rate it positively than others. Older people personally facing serious illness – who are in the best position to judge this issue – give more positive ratings than others. Six in ten older adults with serious illness rate the U.S. health care system as excellent, very good, or good on the care it provides for older people with serious illness, higher than the share without any experience with serious illness (40 percent).

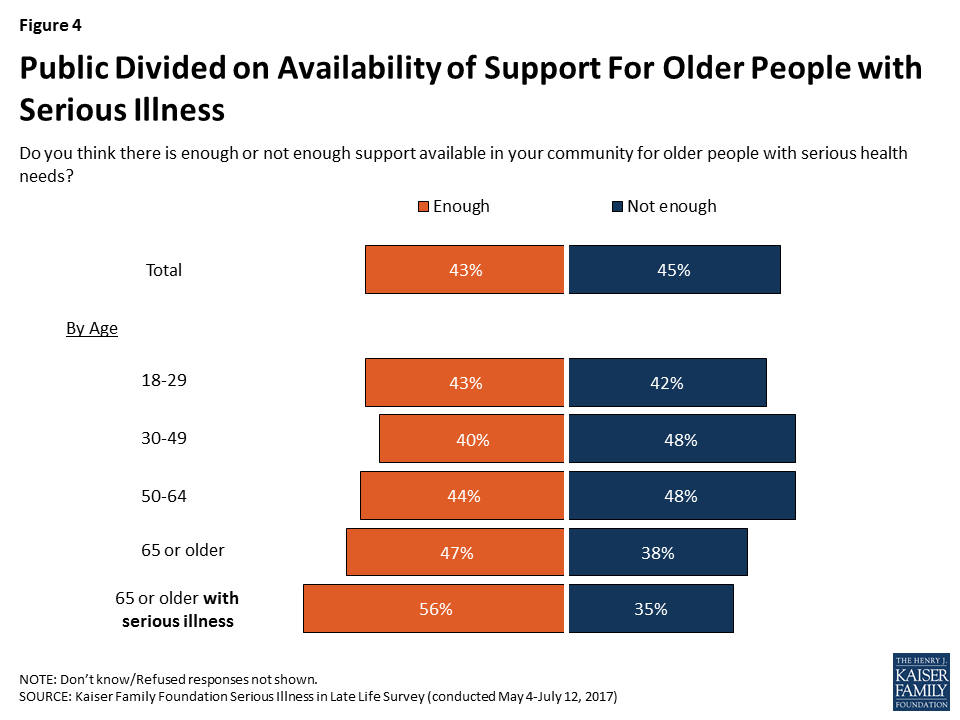

As far as the support available to older people with serious health needs, the public is divided on whether there’s enough support available in their community (43 percent say enough and 45 percent say not enough). Older adults – those 65 or older – lean toward saying there is enough support in their community rather than not enough (47 percent versus 38 percent). Among older adults who themselves are dealing with serious illness, a majority (56 percent) say there is enough support available in their community, while about a third (35 percent) say there is not enough.

Personal Priorities for Older Age

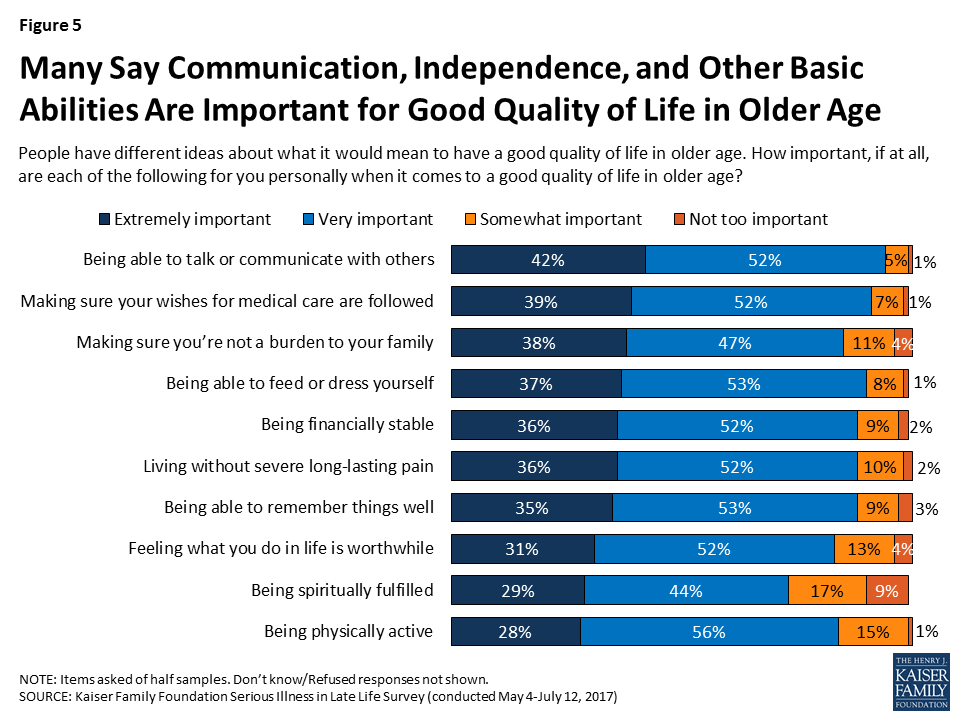

When it comes to what it would mean to have a good quality of life in older age, large majorities of the public say a variety of things are important to them personally, some of which may require advanced planning in order to achieve. About four in ten say a number of things are “extremely” important, including being able to talk or communicate with others (42 percent), making sure their wishes for medical care are followed (39 percent), making sure they’re not a burden to their family (38 percent). Some also say it is “extremely” important to be able to feed or dress themselves (37 percent), to be financially stable (36 percent), to live without severe long-lasting pain (36 percent), and to be able to remember things well (35 percent). In addition, about three in ten say feeling what they do in life is worthwhile (31 percent), being spiritually fulfilled (29 percent) and being physically active (28 percent) are extremely important to them in having a good quality of life in older age.

Focus Group Insights: Given their experience, family members say they want to avoid being a burden on their loved ones if they become seriously ill.

“As far as me, I don’t want my kids to ever deal with me like I have to deal with my wife. I hate it.”

Section 2: Experience Of Older Adults With Serious Illness

In order to better understand how older people with serious illness are faring and what challenges they face in accessing and affording care and support services, the survey included interviews with people who have experience with serious illness, either personally or with a family member.

Individuals were classified as being an older adult with serious illness if they met each of the following criteria:

- they were 65 or older,

- they reported functional limitations due to a health or memory problem such as difficulty preparing meals, shopping for groceries, taking medications, getting across a room, eating, dressing, bathing, or using the toilet,

- they said they have been diagnosed with at least one of the following conditions: diabetes or high blood sugar; asthma, lung disease, emphysema, or COPD; heart disease or had a stroke; cancer, not including skin cancer; Alzheimer’s disease, dementia or memory loss; depression, anxiety or other serious mental health problems; or, chronic kidney disease or kidney failure.

Individuals qualified as a family member of someone with serious illness if their loved one currently met the criteria above or they did so before they recently died. In order to be included, family members also must have said they knew at least something about their family member’s medical care. About 11 percent in the “serious illness experience” group for this survey are themselves dealing with serious illness, 52 percent are family members of someone living with a serious illness, and 37 percent are family members of someone who has died after a period of serious illness. For most family members, their loved one with serious illness is a parent (56 percent), while 21 percent say the person is a grandparent, 9 percent say it is their spouse, and 7 percent say it is an in-law.

Profile of Older Adults with Serious Illness

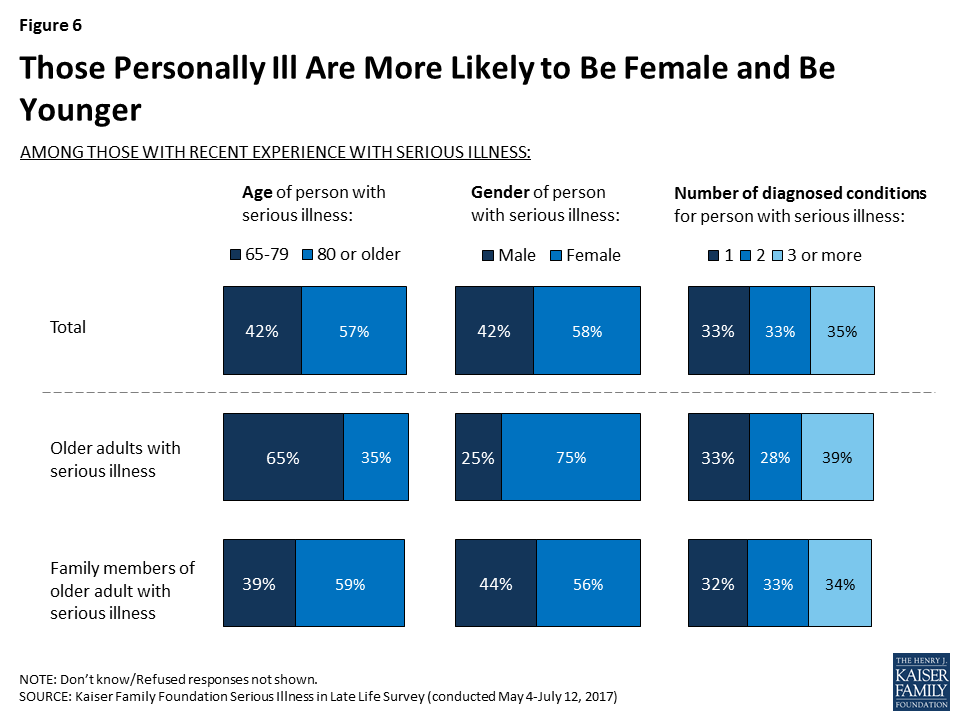

Among those identified in this survey as older adults with serious illness, 58 percent are women, 57 percent are age 80 or older, and two-thirds (67 percent) report having two or more chronic conditions. However, there are some differences in the personal characteristics of those who are personally dealing with serious illness and those whose family member is answering on their behalf.4 For example, while by the definition used in the survey, all older adults with serious illness are (or were) 65 or older, those answering about themselves tend to be younger (65 percent are 65 to 79), while family members’ seriously ill loved ones are usually older (59 percent are 80 or older). In addition, a bigger majority of those answering about themselves are women (75 percent) than family members’ loved ones (56 percent).

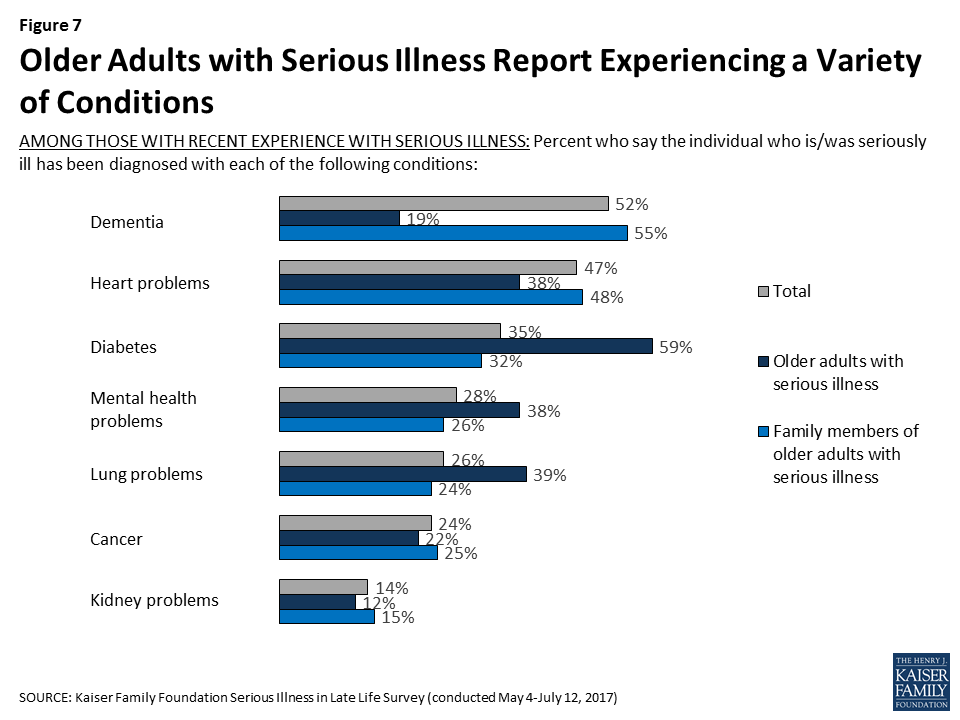

While this survey’s definition of serious illness includes several different conditions, some are more common than others, and reports of these conditions vary by whether someone is personally dealing with serious illness themselves or if they’re responding about a family member. Overall, 52 percent report they or their loved one has been diagnosed with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or memory loss, 47 percent report being diagnosed with heart disease or having a stroke, followed by diabetes (35 percent), mental health problems such as anxiety or depression (28 percent), asthma, lung disease, emphysema, or COPD (26 percent), cancer (24 percent), and chronic kidney disease or kidney failure (14 percent). Those responding about their own experience as an older adult with serious illness are more likely to say they have been diagnosed with diabetes (59 percent), while 55 percent of family members of older adults with serious illness say their loved one has dementia and half (48 percent) say their loved one has heart disease. Some of these differences are at least in part related to the group of seriously ill people that were able to be interviewed, in that they had to be well enough to answer the telephone and not be institutionalized. As a result, the group of older adults who themselves are dealing with serious illness tends to be a group in somewhat better health or potentially at an earlier stage of illness than those with a family member answering on their behalf.

How Older Adults with Serious Illness Compare to Others 65 or Older

There are also some key differences in the personal characteristics of those 65 or older who are seriously ill and those who are 65 who are not classified as seriously ill. Older people with serious illness are much more likely than their peers to be female (75 percent versus 53 percent), widowed (42 percent versus 24 percent), have an annual income of less than $40,000 (64 percent versus 38 percent), and have a high school education or less (71 percent versus 40 percent). They are also somewhat more likely than their peers to be Black (18 percent versus 9 percent) or Hispanic (12 percent versus 5 percent).

Utilization of Medical Services Among Older Adults with Serious Illness

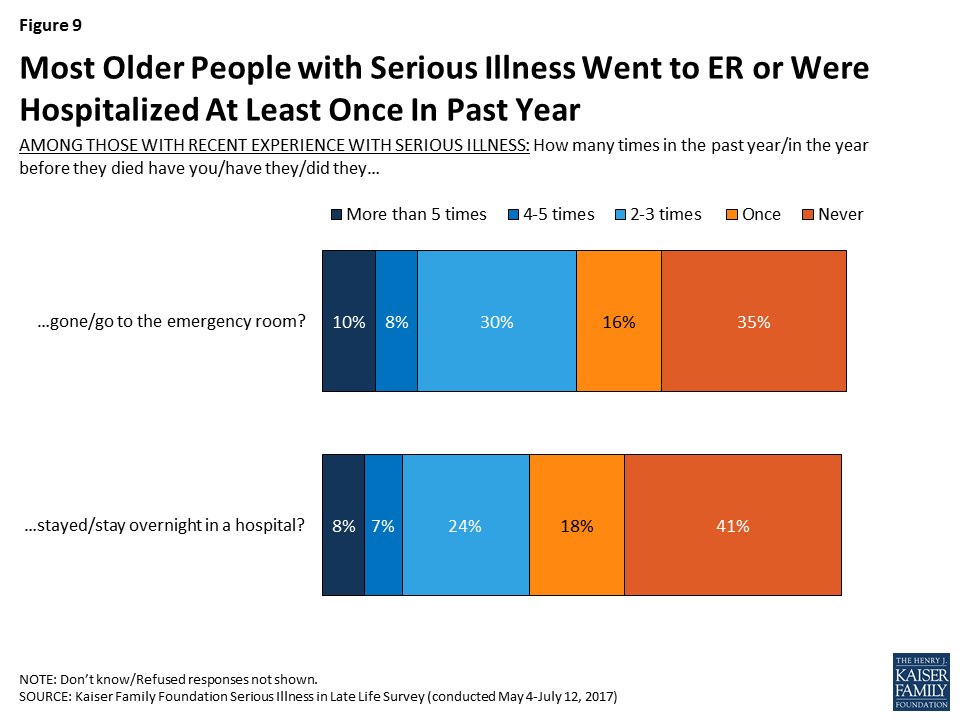

Among older adults and family members of older adults with serious illness, about two-thirds (64 percent) report that they went to the emergency room in the past year (or in the year before they died for those with a deceased family member), including 10 percent who say they went more than five times. In addition, about six in ten (58 percent) say that the seriously ill person stayed overnight in the hospital in the past year, or in the year before they died. Those whose loved one is deceased are more likely than others to say they had gone to the emergency room (75 percent) or stayed in the hospital overnight in the year before they died (78 percent).

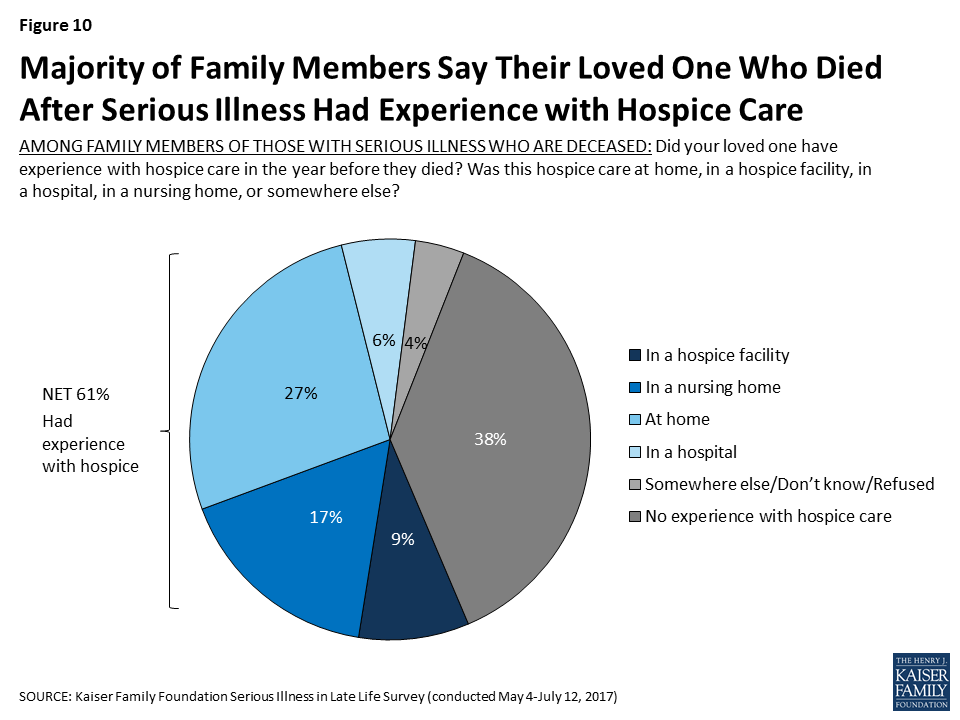

Among those family members whose loved one is deceased, 61 percent say their loved one had some experience with hospice in the year before they died. Family members most commonly say their loved one had hospice care at home (27 percent), followed by in a nursing home (17 percent), in a hospice facility (9 percent), and in a hospital (6 percent).

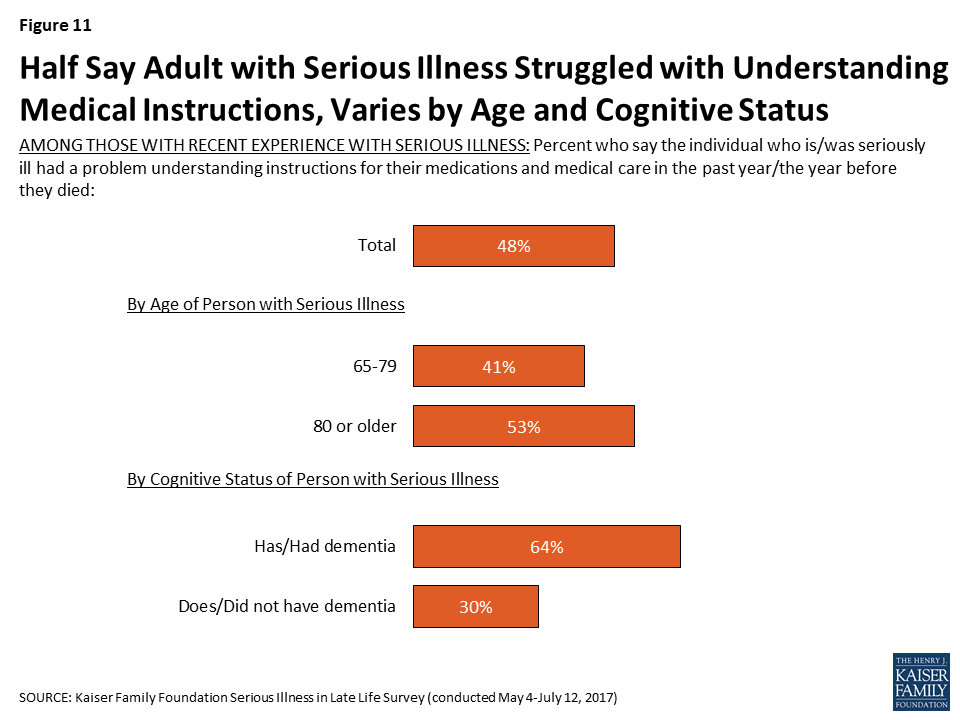

Problems Faced by Older Adults with Serious Illness

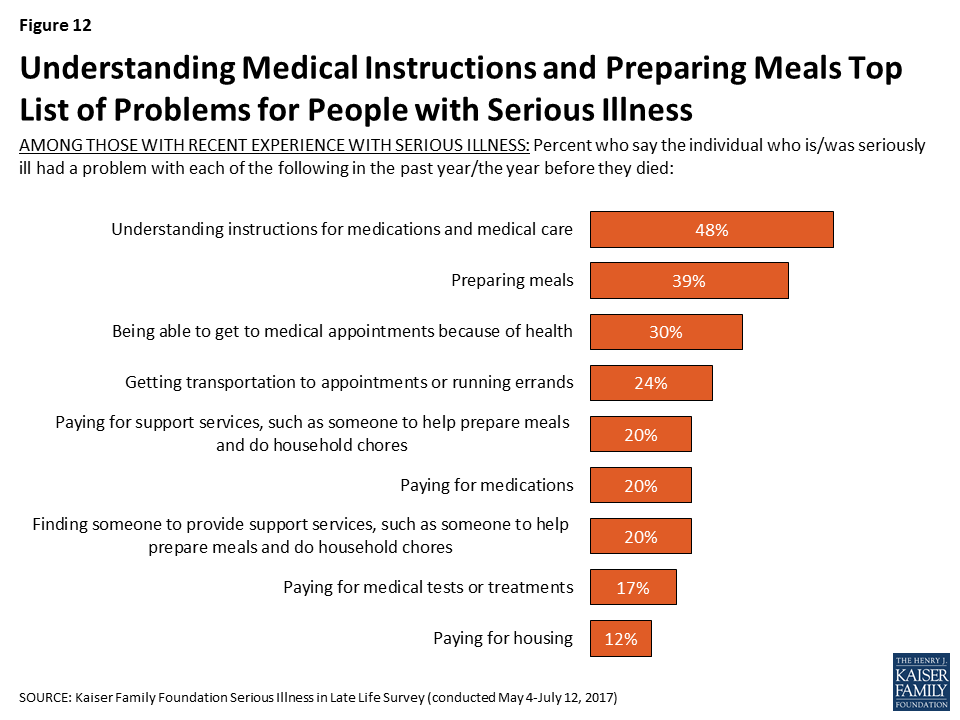

People with serious health needs can face a variety of challenges, ranging from difficulty managing daily tasks independently to having trouble affording medical care and support services. Nearly half (48 percent) of individuals and family members of older adults with serious illness say that in the past year they had a problem understanding instructions for medications and medical care. Those ages 80 or older (53 percent) are more likely than those between 65 and 79 to say they had problems understanding medical instructions (41 percent). In addition, reports of trouble understanding instructions for medical care and medications are about twice as common for those with dementia than for those without (64 percent versus 30 percent).

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness noted that managing medications is often a challenge. People expressed concern about the number of medications their loved ones were taking as well as the medications that are needed to treat side effects of other medications, and the side-effects in general.

“It took me an hour and a half after mom got out of the hospital, just to do two weeks of morning and evening pills. … She was already on a lot of medications. Just sorting it all out, it was crazy.”

Older adults with serious illness report other problems as well. About four in ten (39 percent) say they or their family member with serious illness had trouble preparing meals in the past year, 30 percent say they had trouble getting to appointments because of their health, 24 percent say they had trouble getting transportation or running errands, and 20 percent say they had trouble finding someone to provide support services.

In addition, being able to afford the things they need is an issue for some. About one in five say they have trouble paying for support services (20 percent), medications (20 percent), and medical tests or treatments (17 percent). Relatively few say they have had trouble paying for housing (12 percent). Those with lower incomes (less than $40,000 annually) are more likely than those earning $40,000 or more to say that they or their family member had trouble paying for medications (33 percent versus 13 percent), medical treatments (27 percent versus 11 percent), and housing (16 percent versus 9 percent).

It is important to note that while Medicare covers the basic medical care that older people require, it does not typically pay for long-term care and support services that people with serious illness may need. As a result, many must pay for these types of services out-of-pocket, with the exception of those with incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid. In light of this, it may be surprising that problems paying for medical care and problems paying for support services rank similarly. However, this may be at least in part because the question asks about those who have had difficulty paying for care and does not reflect those who may not have tried to get this type of help because they felt they couldn’t afford it.

In addition to issues paying for support services, medications, medical treatments or housing, about three in ten family members of those currently living with serious illness are not confident that their loved one will have enough income and assets to last for the rest of their life, while a majority are at least somewhat confident (71 percent).

Problems with Mood or Cognition

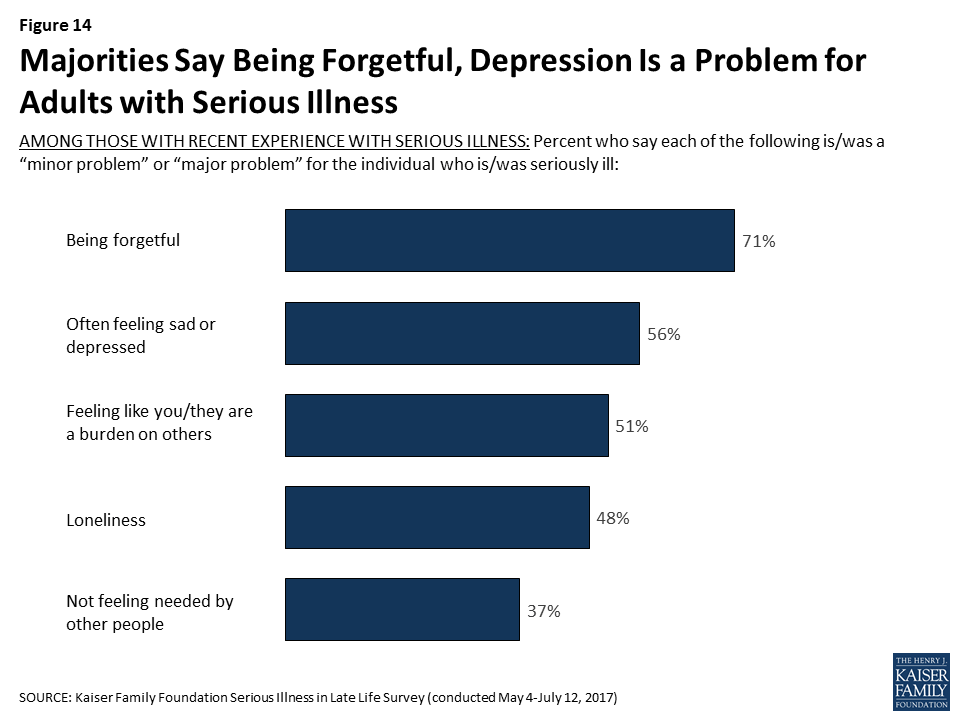

Many older adults with serious illness and their family members report issues with memory – seven in ten say being forgetful is at least a minor problem, including nearly half who say it is a major problem. Many also report issues with mood such as often feeling sad or depressed (56 percent), feeling like a burden on others (51 percent), and loneliness (48 percent), which can have a negative impact on health. Fewer, 37 percent, report that not feeling needed by other people is a problem.

Assistance For Older Adults with Serious Illness

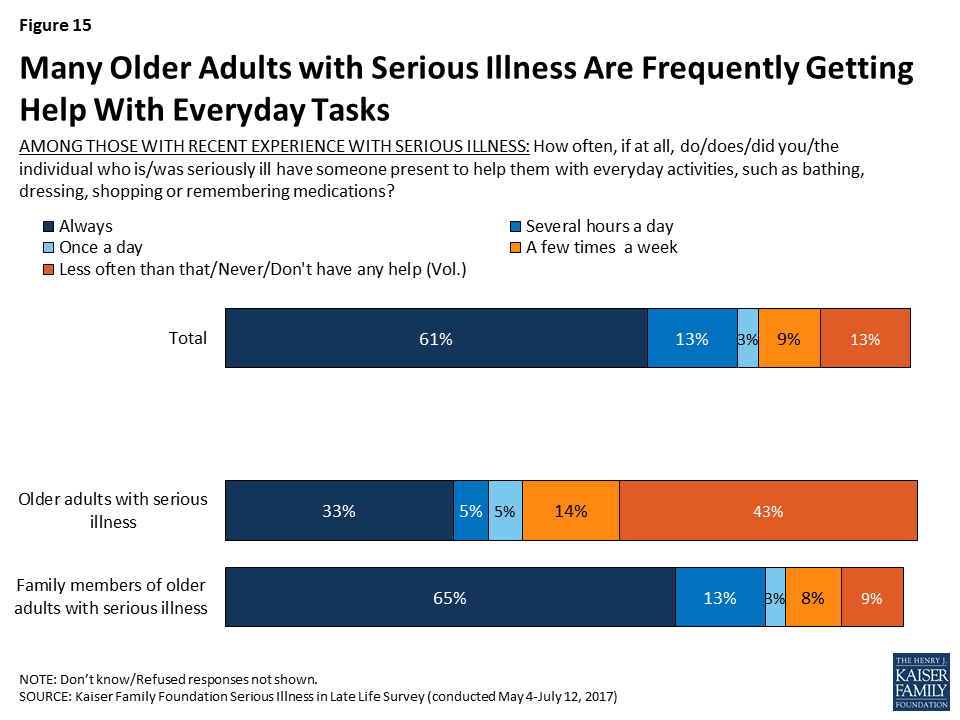

Many older adults who are seriously ill report getting frequent help. Six in ten (61 percent) say they or their loved one always has someone present to help them with everyday activities like dressing, bathing, shopping, or remembering medications, and an additional 13 percent say they have someone present several hours a day.

There are big differences for those responding to the survey who are dealing with serious illness themselves – 33 percent say they always have someone present to help, but 16 percent say they never do and 27 percent say they have help less than a few times a week. In contrast, the majority of those with family members with serious illness say their loved one always has someone present to help (65 percent). As noted earlier, this is likely related to the fact that those answering about themselves are relatively younger and in somewhat better health than the loved ones family members are referring to.

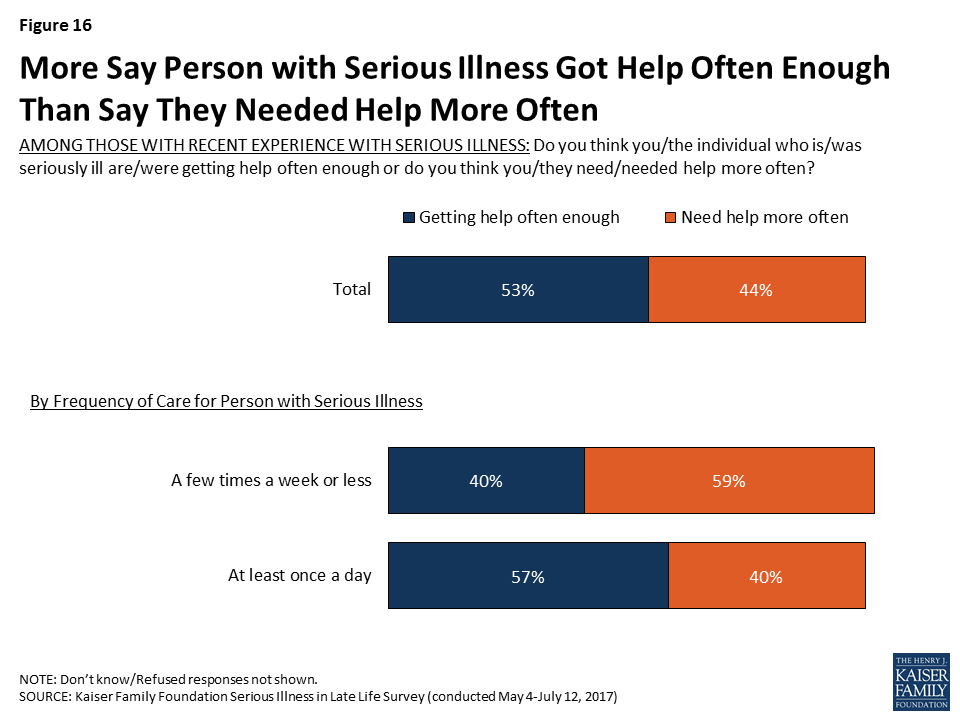

Slightly over half feel they or their family member are getting help with daily activities often enough, but over four in ten feel like they need help more often than they are getting. Those getting care just a few times a week or less are more likely than others to say they need help more often (59 percent versus 40 percent).

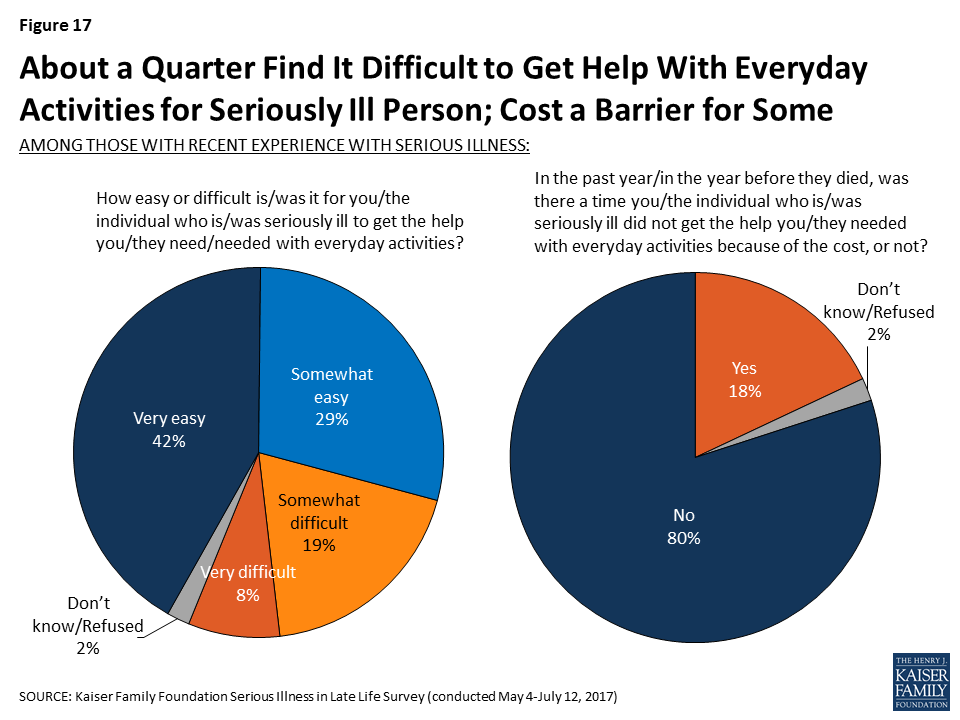

While most (71 percent) say it is easy to get the help needed with everyday activities, about a quarter (27 percent) say it is either somewhat (19 percent) or very difficult (8 percent) to get the help needed. In addition, about one-fifth of those with experience with an older adult with serious illness (18 percent) say that in the past year, there was a time they did not get the help they needed with everyday activities because of the cost.

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness reported non-medical help – for example, providing companionship, household chores, and errands – is crucial but often difficult to find and afford.

“I’m going to be looking for some help coming up in the next three or four weeks. I’m really not sure which direction to go…I’m going to try and find some people that know what they’re doing and will be there for you.”

Who is Providing Help?

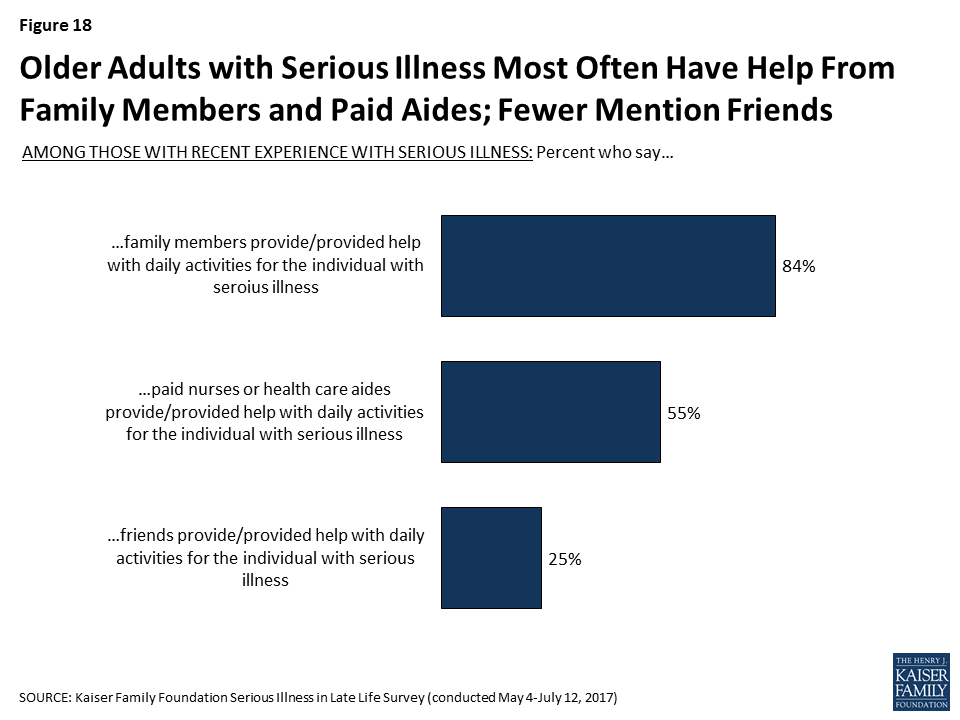

Family members are a primary source of help with everyday activities for older people with serious illness – 84 percent report that the older adult with serious illness receives help from a family member. Over half of older adults who themselves are dealing with serious illness (56 percent) say a family member helps them with everyday activities. In addition, 57 percent of family members say they personally help their loved one with daily activities, but a large majority (73 percent) also say that another family member provides help, including 79 percent of those family members who do not personally provide care. Professional caregivers are also a key source of help for those with serious illness, with over half (55 percent) saying paid nurses or health care aides help with everyday activities. In addition, a quarter say that friends are helping with daily activities (25 percent).

Most of those getting paid help say the nurse or health care aide is well trained (89 percent) and rate the quality of the care provided as very good or excellent (63 percent), however a few report being less satisfied with the help, including 10 percent who say the people helping them were not well trained and 12 percent who rate the care as fair or poor. Family members who report that other family members play a role in providing help most often say that the other family members were well trained (74 percent), and most getting help from friends feel they were well trained as well (66 percent).

Family Members Personally Providing Care

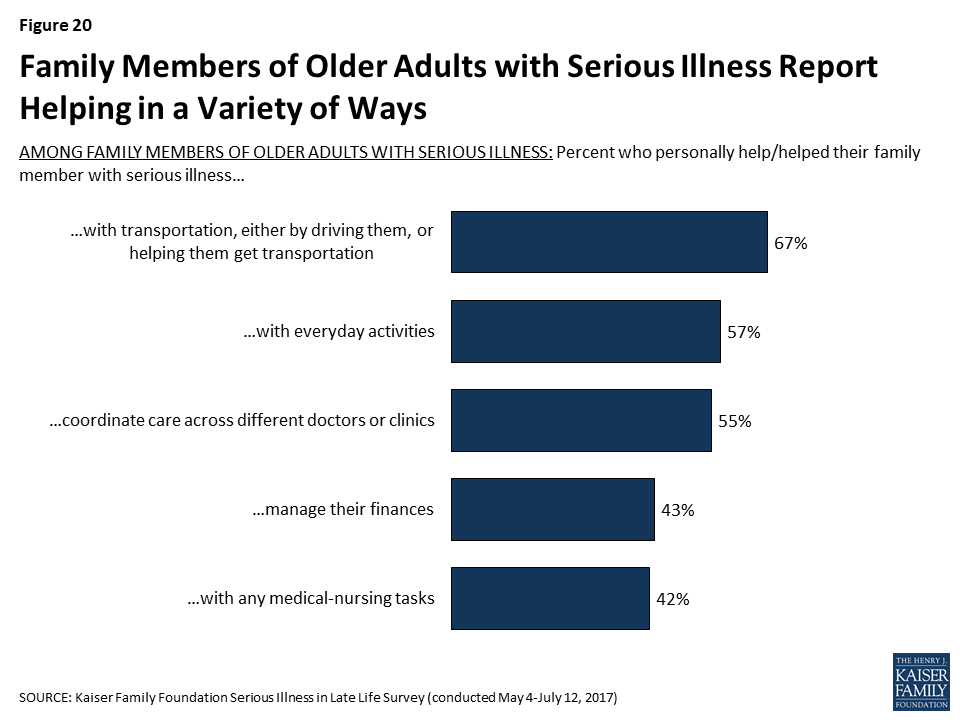

Family members of older adults with serious illness report helping with a variety of tasks. Most commonly, family members report helping their loved one with transportation (67 percent), but, as noted above, nearly six in ten also say they help with daily activities (57 percent), and over half say they help with coordinating care across different doctors or clinics (55 percent). In addition, about four in ten say they help with managing their loved one’s finances (43 percent) or with medical-nursing tasks, including things like giving medicines, monitoring blood pressure or blood sugar, helping with incontinence, or operating equipment like hospital beds (42 percent).

About half of family members who provide some type of assistance say they are doing so several hours a day or constantly, while 24 percent say a few hours a week and 13 percent say less often than that. Most of those providing help with daily activities said there was someone that could provide respite (79 percent), but 21 percent of family members, including 24 percent of family members who are providing care for at least an hour a day say that there is no one that can give them a break from caring for their loved one.

Focus Group Insights: Caregivers are faced with making difficult decisions about how much time they should devote to caring for a loved one. Those who care-give full-time make substantial sacrifices.

“Yeah, I watched 18 years go by when I quit working. I was there all the time. If I went out, somebody had to be there with her, so no. I kind of gave up my life for a while.”

******

Having support and relief for caregivers is key, as it’s both physically and emotionally taxing.

“We have to take care of ourselves because if we don’t they’re not going to have anybody to take care of them. I was to the point where I was about ready to split. I was tired and wasn’t thinking right. I started asking people, ‘Could you come and stay? Let me just get out for a little while.’ That’s happened. It’s a lot better. Your brain gets a little crazy when you’re tired.”

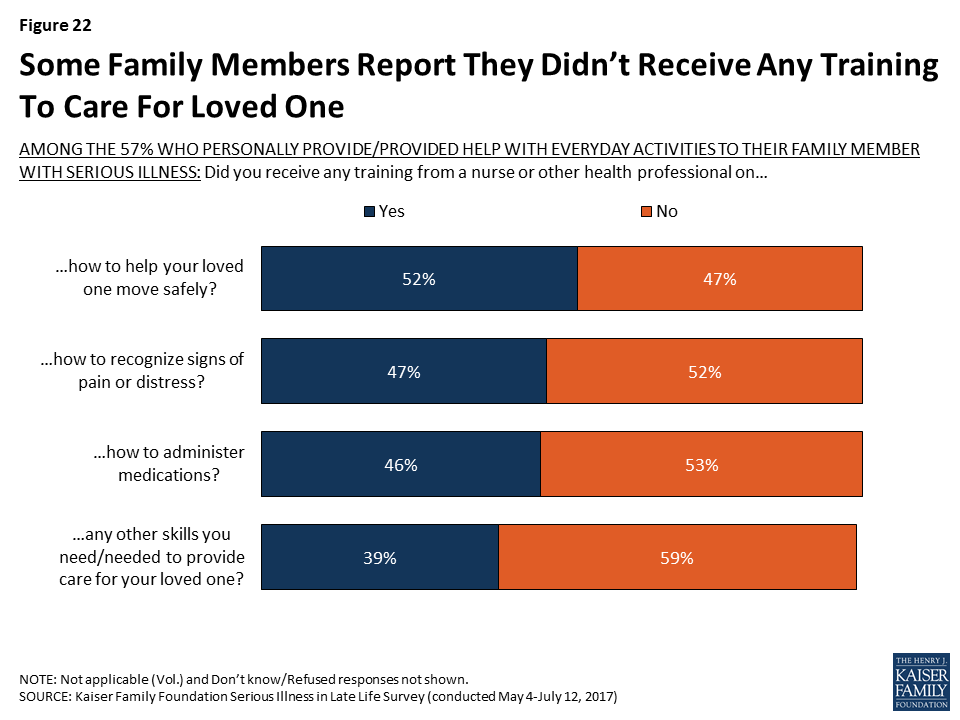

In terms of the specific types of training that family members received from a nurse of other health professional, significant shares of those providing help with daily activities say they received training on how to move their loved one safely (52 percent), how to recognize signs of pain or distress (47 percent), and how to administer medications (46 percent). Still, about half say they did not receive training in each of these areas, and 31 percent say they did not receive any of these types of training.

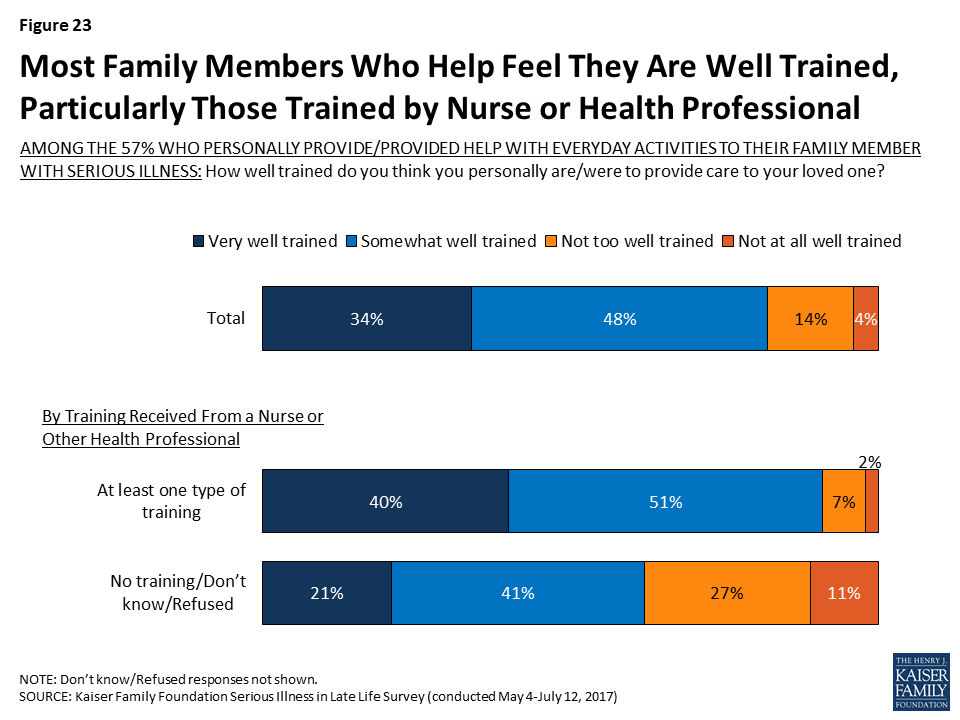

A large majority (82 percent) of family members who report personally helping their loved one with everyday activities feel they were at least somewhat well trained to provide care, but about one in five feel they were not well trained (18 percent). Family members who report getting at least one of these types of training from a nurse or health professional are more likely than others to say they feel they were well trained to provide care to their loved one (91 percent versus 62 percent). During focus groups with family members of those with serious illness, some said they learned how to care for their loved one independently, from family members, or through online resources, which may in part explain why more family members feel well trained than say they received training from a nurse or health professional.

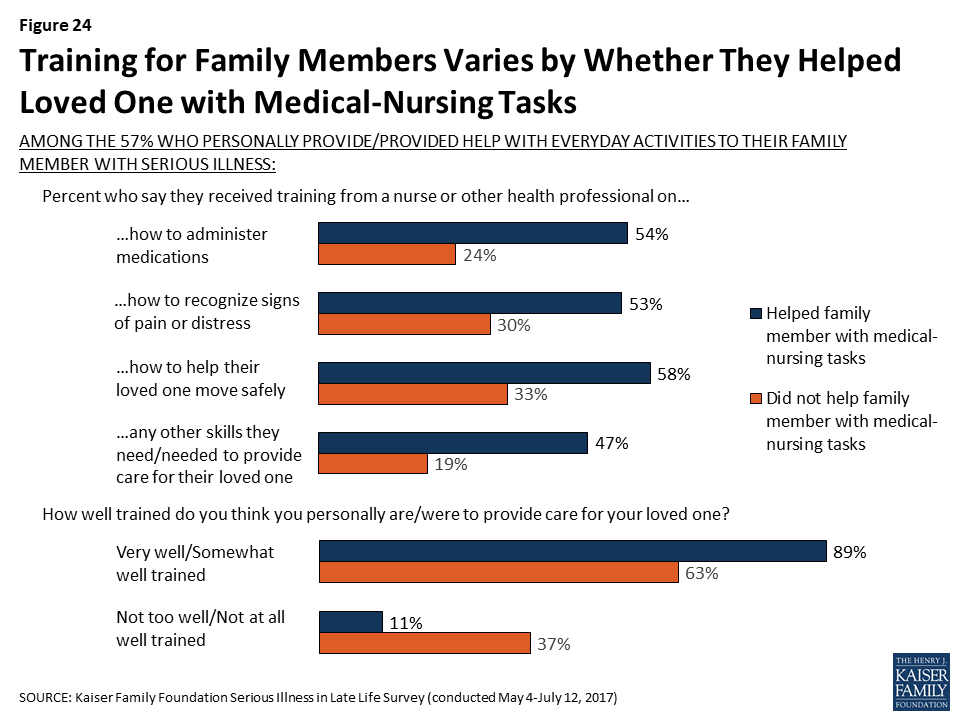

Those providing medical-nursing types of care are much more likely than family members who are not doing medical-nursing tasks but are providing help more generally to say they received training from professionals. For example, over half of family members who report helping with nursing tasks say they received training from a nurse or another health professional on how to help their loved one move safely (58 percent) and how to administer medications (54 percent), shares that are much higher than for family members who help with daily activities but who aren’t providing nursing care (33 percent and 24 percent, respectively). The vast majority of family members helping their loved one with nursing tasks feel they were well-trained (89 percent), including 41 percent who say they were ‘very’ well trained.

Focus Group Insights: Some suggested classes for family members that provided information on a person’s illness and prognosis or basic caregiving training.

“The one thing I would say, for my family members, I was able to show them how to wash hair, how to change the bed with the person in it, those things. But it would have been so helpful if the hospital, community center, anybody, had offered some basic classes.”

“I had to learn for myself. It’s the best way to do that from my end. I have sisters and brothers that help me with the medications, set it up and all that stuff but just to be hands on and do it myself and learn it, watch different videos on it and just research myself.”

Seriously ill person’s needs being met

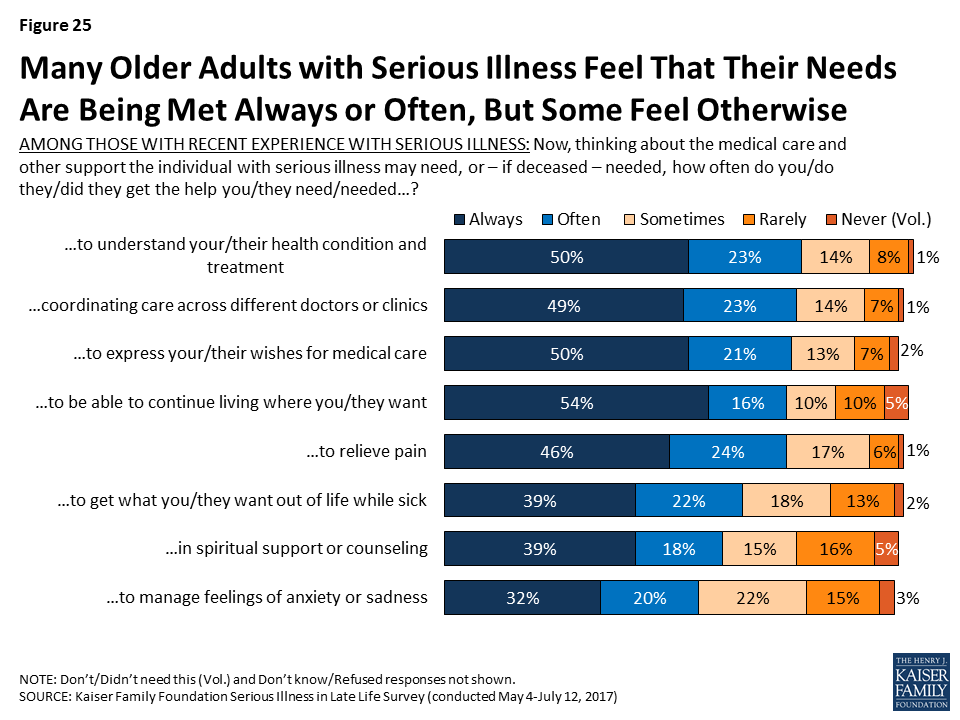

While many say that the person with serious illness could use help more often than they’re getting, large shares report that their or their seriously ill family member’s needs are often or always being met in specific areas, particularly in regard to help understanding their health condition and treatment (73 percent), coordinating care across different doctors or clinics (73 percent), being able to continue living where they want to be living (71 percent), expressing their wishes for medical care (71 percent), relieving pain (69 percent), and getting what they want out of life while sick (61 percent). In addition, just over half say they or their loved one often or always gets the help they need with spiritual support or counseling and to manage feelings of anxiety or sadness. However, there are some who say their needs are just sometimes, rarely, or never met, most often in help to manage feelings of anxiety or sadness (40 percent), in spiritual support or counseling (37 percent), and in getting what they want out of life while sick (34 percent).

Focus Group Insights: Aspects of care that family members of seriously ill people said were challenging included things like coordinating care across many different providers and getting treatment information from providers.

“Trying to get in touch with your primary care is like trying to get in touch with the president, you can’t.”

Family Members’ Needs Being Met

While seriously ill people themselves have many needs that must be met, family caregivers are also often in need of emotional and logistical support. Most of those who are family members of an older person with serious illness say they often or always get the help they need understanding their loved one’s condition and with coordinating care across different clinics and providers. However, like people with serious illness themselves, the areas where more family members are less often getting the care they need is with spiritual support and managing feelings of anxiety or sadness, with about four in ten saying their personal needs in these areas were just sometimes, rarely, or never met (40 percent and 45 percent respectively). These findings hold true for those personally providing help at least an hour a day (43 percent and 48 percent, respectively).

Focus Group Insights: Because of challenges with care coordination, some family members of those with serious illness felt the level of care was dependent on a family’s ability to advocate and be there for their loved one.

“You really have to be aggressive and keep up with every single thing when you’re in the hospital. Because they will fall through the cracks.”

******

Many family members of those with serious illness mentioned efforts to research conditions on the internet and feeling like they needed more ‘big picture’ information from medical providers about the course of illness and what they could expect down the line.

“I don’t know if they assume that you know what all is going to happen to you when you have chemotherapy and cancer, and they don’t walk you through it, or if that’s just common not to be taught what to expect.”

Section 3: Documenting And Talking About Wishes

As people live longer with more chronic conditions, the potential for more serious health needs increases and people may experience many years of worsening health, including longer periods of time with significant physical or mental functional limitations. One way to help family members and medical providers honor and respect a person’s desires and choices about how they would like to live and be treated in the event they become seriously ill is to have a written document, no matter what age, that describes their wishes and expectations for care, such as the types of treatments they may or may not want, as well as who they would like to make decisions for them if they are no longer able to make decisions on their own. A document outlining a person’s preferences for medical care can have a variety of different names, such as a living will, an advanced treatment directive, a do-not-resuscitate order (DNR), or physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. Other documents may name a person to make decisions about medical care on another person’s behalf, a designation that is sometimes called a health care proxy or surrogate or a durable power of attorney. Throughout this report, these two types of documents will generally be referred to as a document describing a person’s medical wishes and a document naming who would make decisions on another’s behalf.

Nearly All Say Written Documents Are Important and Should Be Done Early in Adulthood

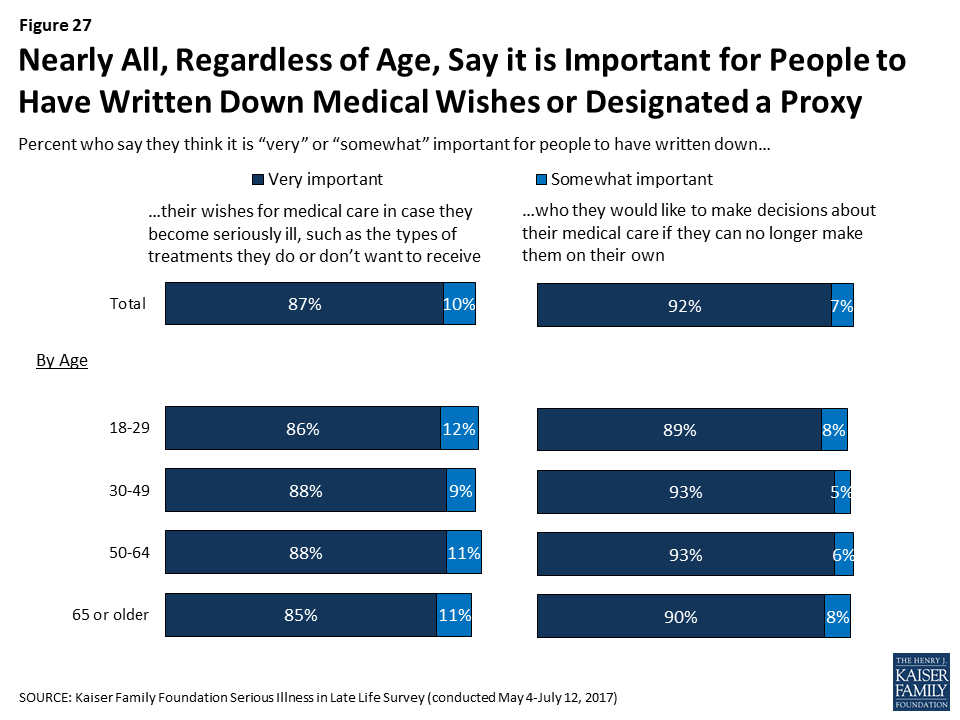

Nearly all adults, regardless of age, say it is important for people to have written down their wishes for medical care or who they would like to make decisions about their medical care in case they become seriously ill.

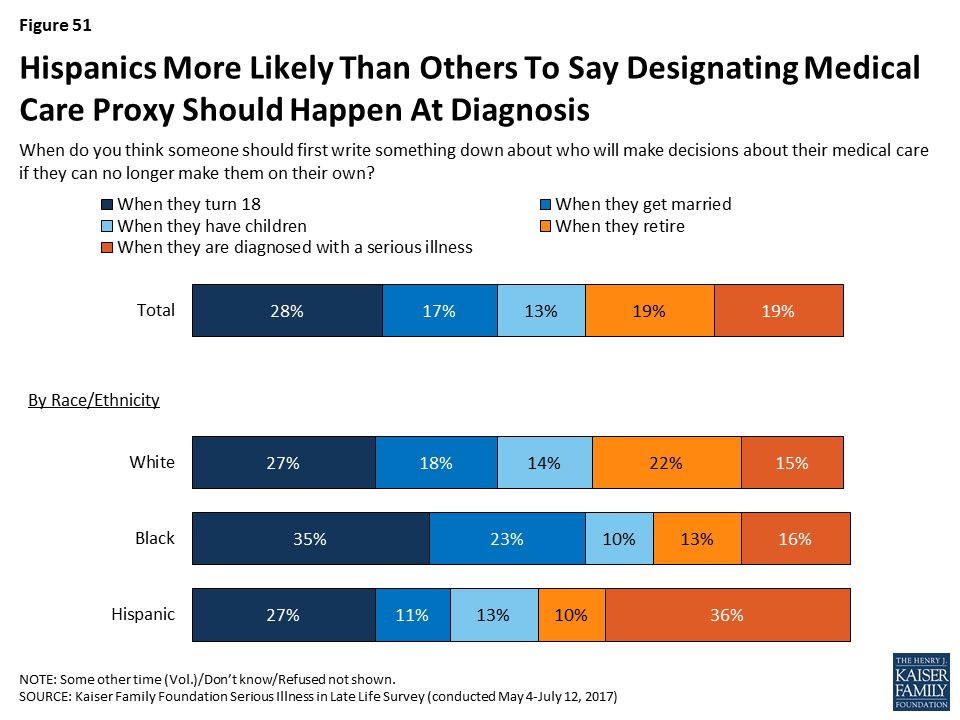

When asked when a person should first write something down about who will make decisions about their medical care if they’re no longer able to make them on their own, the most common answer is when they turn 18 (28 percent), followed by when they retire (19 percent), when they are diagnosed with a serious illness (19 percent), when they get married (17 percent), and when they have children (13 percent). Older adults more commonly say that people should write down who they want to make decisions for them when they retire, while younger people more commonly say it should be done when they turn 18.

Focus Group Insights: Participants felt that planning for serious illness is important to do before someone becomes sick. They noted that conversations during illness were often challenging, wrought with emotion and difficult trade-offs, or came too late.

“We made some decisions that I regret. But we did it not knowing what his real wishes would have been. He wasn’t capable of telling us at that point.”

But, Fewer People Report Actually Having Written Documents

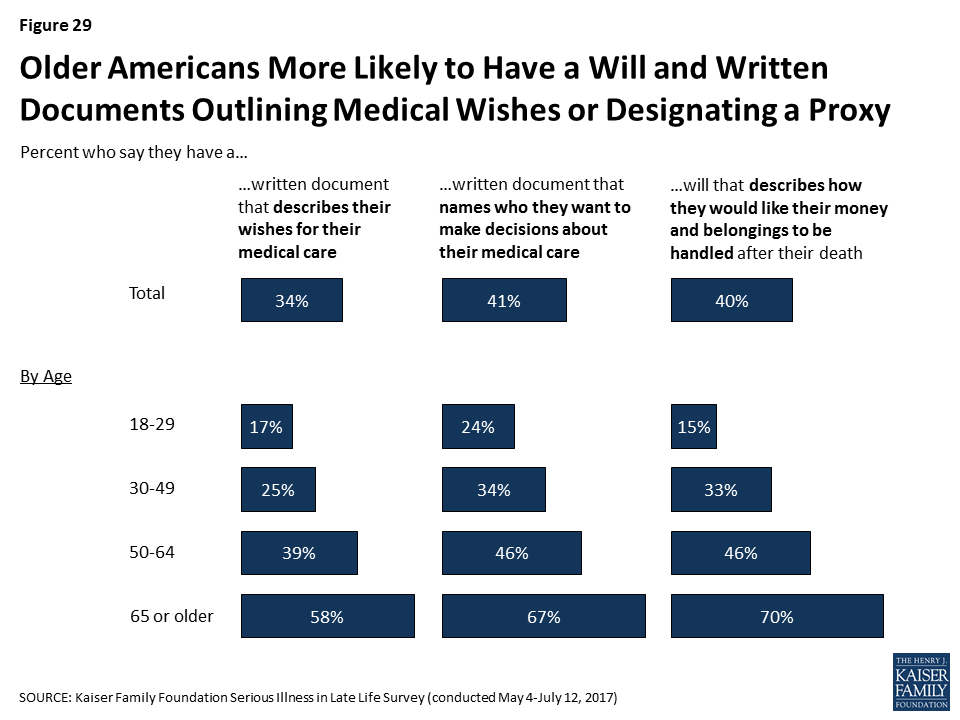

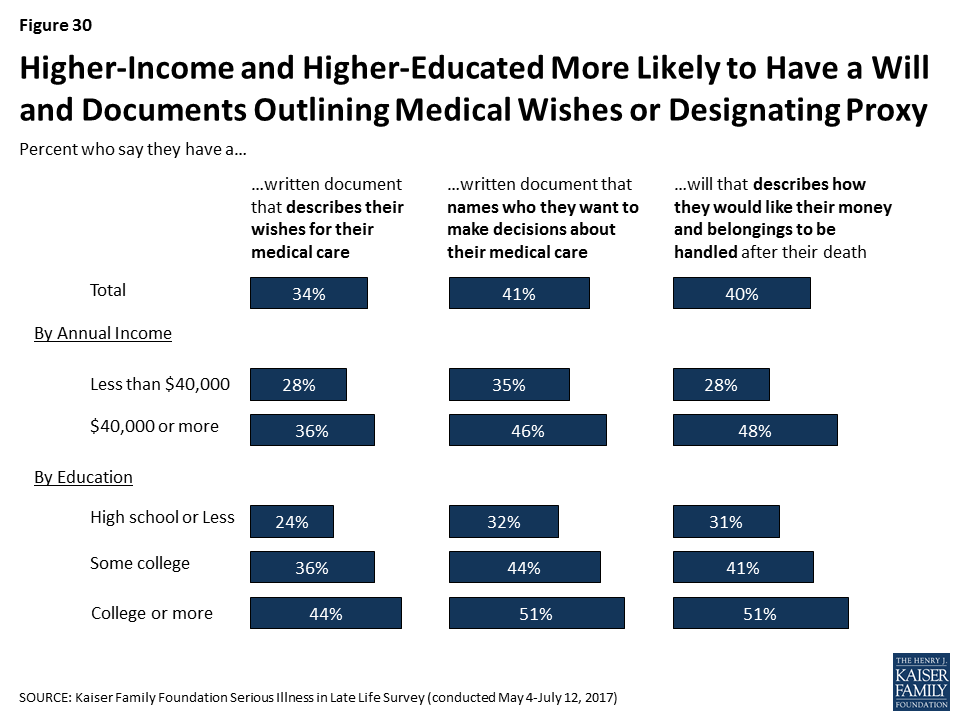

While nearly all say it’s important to have written documents, just a third of the public (34 percent) say they have a written document that describes their wishes for medical care if they became seriously ill, such as the types of treatments they would or would not want to receive. Slightly more (41 percent) report having a document that designates who they would want to make decisions about medical care on their behalf. In addition, for comparison, a similar share (40 percent) say they have a will that documents how they would like their money and belongings handled after their death. Perhaps not surprisingly, those who are older are much more likely to say they have these documents than younger people. For example, two-thirds of those 65 or older say they have a written document designating a proxy, while just a quarter of those 18 to 29 years old say they do (24 percent).

Those with lower levels of income or education are significantly less likely to report having these types of documents. For example, about a third of adults with a high school education or less (32 percent) say they have a document naming a person they would like to make decisions about their medical care, compared to 44 percent of those with some college education and 51 percent of those with at least a college education.

Whether a person is seriously ill or knows someone who is appears to play a limited role in whether or not they have these types of documents. Despite their poor health status, older adults who are themselves dealing with serious illness are somewhat less likely than their peers who are 65 or older to report having such documents. While this may seem counter to the expectation that those in poor health would be more likely to have these documents, this finding is related to the fact that those personally dealing with serious illness themselves report lower levels of education and income which, as noted above, are both factors that make someone less likely to have these types of documents. In addition, those who have a loved one who recently died after a period of serious illness are somewhat more likely than those with no such experience to say they have these documents.

| Table 1: Reports of Planning for Serious Illness by Experience with Illness and Discussion of Death | ||||||||

| Older adults (65+) with serious illness | Older adults (65+) without serious illness | Recent experience with serious illness of a family member | Has a family member or close friend who has died after a period of serious illness | Talked about deathgrowing up | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Occasionally/Fairly often | Never/rarely | |||

| Percent who say they have a written document that… | ||||||||

| …describes their wishes for medical care | 44% | 59% | 39% | 32% | 37% | 25% | 37% | 30% |

| …names who they want to make decisions about their medical care | 56 | 68 | 47 | 40 | 44 | 35 | 45 | 38 |

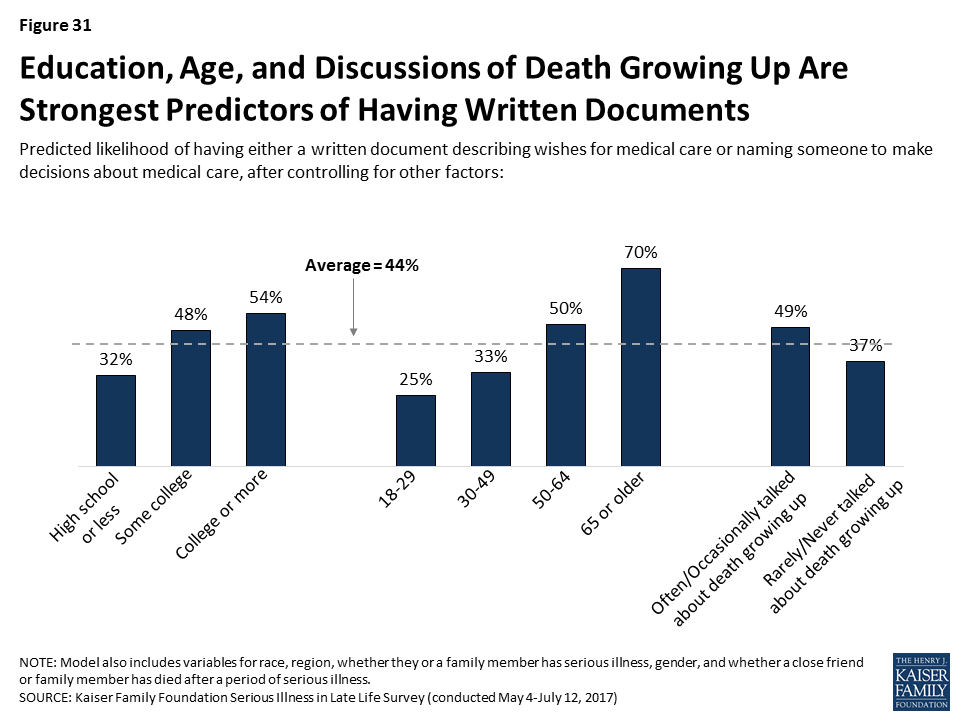

Because many of the factors that can influence whether someone has these types of written documents are inter-related, we conducted a regression analysis to isolate which factors are the strongest predictors of who reports having either type of document. This analysis found that age is the biggest factor in having these types of documents. In addition, those with higher levels of education and those who report that their family talked about death at least occasionally when they were growing up, were more likely to report having either of these documents, even after controlling for factors such as race/ethnicity, personally being seriously ill or knowing someone who has died after a period of illness, region, and gender.

Assistance In Writing Documents

Among those who have documents either describing their wishes for care or designating a medical proxy, most say someone helped them prepare the documents. Most often people say it was a lawyer who helped them, and notably very few report getting help from a doctor or nurse or a staff member at a hospital or clinic. About a third of those who have such documents (roughly one in ten of the public overall) say they wrote them on their own.

| Table 2: Most With Documents Say Someone Helped Them | ||

| Percent who say they… | Document describing wishes | Document designating proxy |

| Have a written document | 34% | 41% |

| Someone helped write document | 21% | 25% |

| Lawyer helped | 13% | 15% |

| Family member helped | 4% | 5% |

| Staff member at a hospital or clinic helped | 1% | 2% |

| Doctor/Nurse helped | 1% | 1% |

| Friend helped | 1% | 1% |

| Someone else helped | 1% | 2% |

| Wrote document on their own | 10% | 14% |

| Note: Multiple answers were accepted for who helped. | ||

Creating and Reviewing Documents

Keeping these documents up to date can help avoid questions and confusion when they are put to use. Most of those who report having such a document, or about a quarter of the public overall (27 percent), say they first created or have reviewed the document within the past five years, including 13 percent who say they created or reviewed the document within the past year. Just 6 percent of the public say they have a document and they’ve made changes to the document since they first created it.

Sharing Documents with Others

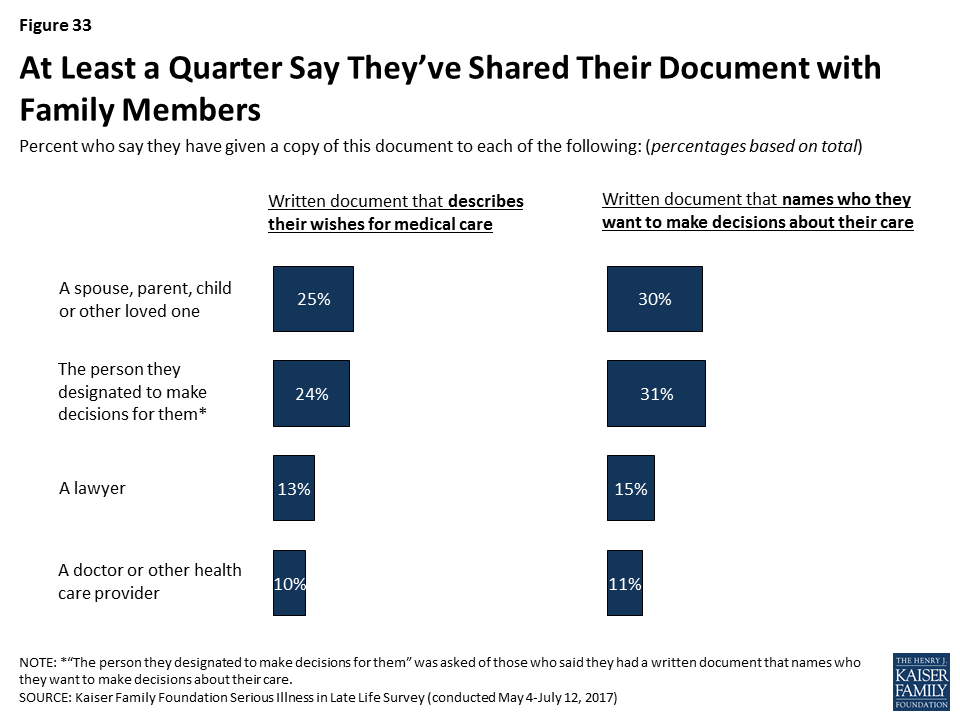

These types of documents can be more useful in helping loved ones and medical providers follow a person’s wishes if others know they exist and where to find them. Large majorities of those with a document (between a quarter and three in ten of the public overall) say they’ve given it to a spouse, parent, child, or other loved one, or that they’ve specifically given it to the person designated to make decisions for them. However, relatively few say they have given the document to a lawyer, and perhaps most importantly, just about three in ten of those with these types of documents (one in ten of the public overall) say they have given them to a doctor or other health care provider.

Barriers to Written Documents Outlining Wishes

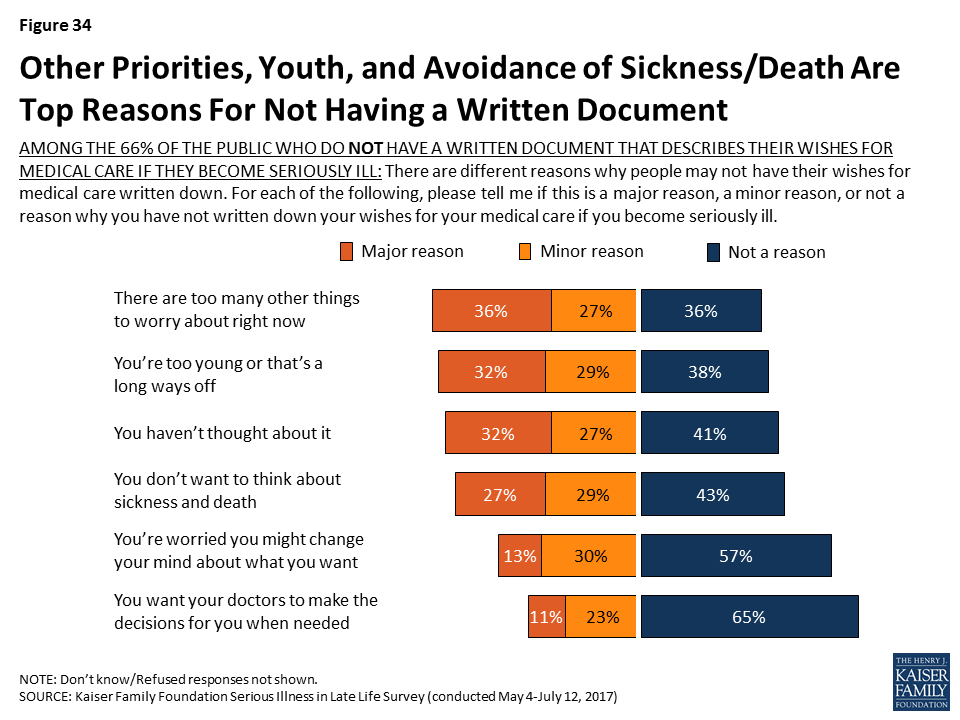

For the 66 percent of the public that report not having a written document that outlines their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, many say that a number of barriers stand in their way, such as having too many other things to worry about right now (63 percent), feeling too young or that it’s a long way off (61 percent), they haven’t thought about it (58 percent), or that they don’t want to think about sickness and death (56 percent). Younger people are more likely than older people to say most of these are reasons they don’t have a written document outlining their wishes.

| Table 3: Barriers to Written Documents Outlining Wishes Varies by Age | |||||

| AMONG THE 66% OF THE PUBLIC WHO DO NOT HAVE A WRITTEN DOCUMENT THAT DESCRIBES THEIR WISHES FOR MEDICAL CARE IF THEY BECOME SERIOUSLY ILL: Percent who say each of the following was a major or minor reason why they have not written down their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill: | Total | Age | |||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | ||

| There are too many other things to worry about right now | 63% | 71% | 65% | 58% | 50% |

| You’re too young or that’s a long ways off | 61 | 80 | 66 | 49 | 34 |

| You haven’t thought about it | 58 | 61 | 66 | 51 | 47 |

| You don’t want to think about sickness and death | 56 | 56 | 60 | 60 | 41 |

| You’re worried you might change your mind about what you want | 42 | 48 | 45 | 37 | 33 |

| You want your doctors to make the decisions for you when needed | 34 | 37 | 35 | 30 | 31 |

Focus Group Insights: Barriers to planning and writing down wishes include a societal taboo of discussing death, fear of death, and procrastination.

“I’m not ready to die, I think I’m too young.”

“Nobody wants to be faced with their own mortality.”

“I’ll deal with it tomorrow. The perpetual tomorrow”

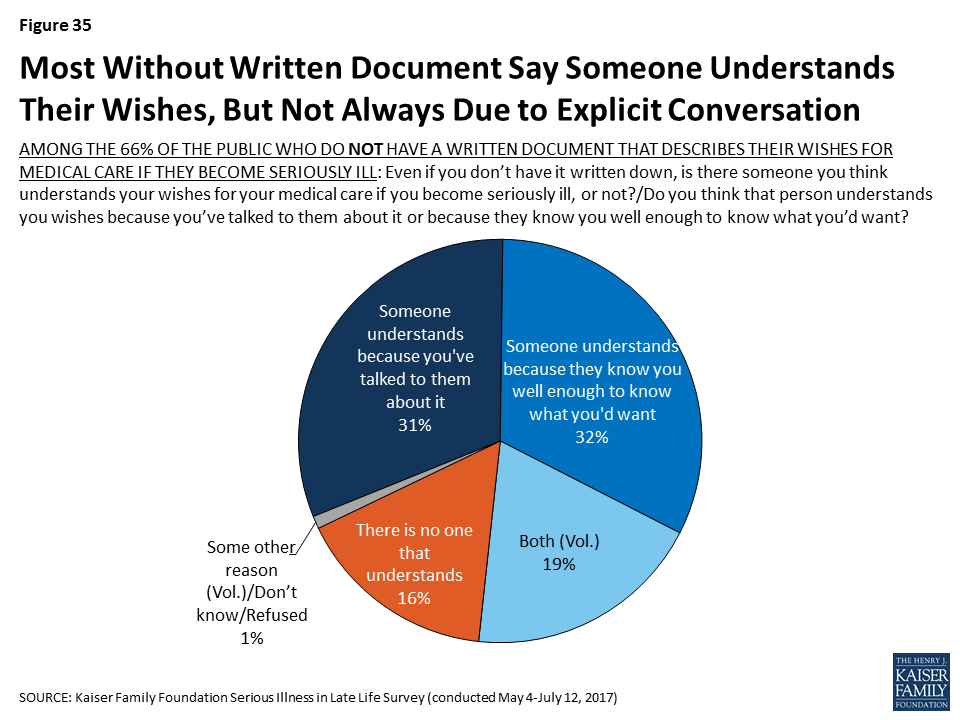

Perhaps another barrier that prevents people from creating documents outlining their wishes for medical care is the feeling that someone else already understands what they would want. More than eight in ten of those who don’t have a written document describing their medical wishes say they think there is someone who understands their wishes. However, some (32 percent of those without a written document) say they think that someone else knows their wishes because they know them well enough to know what they’d want, rather than because they’ve talked to them about it (31 percent).

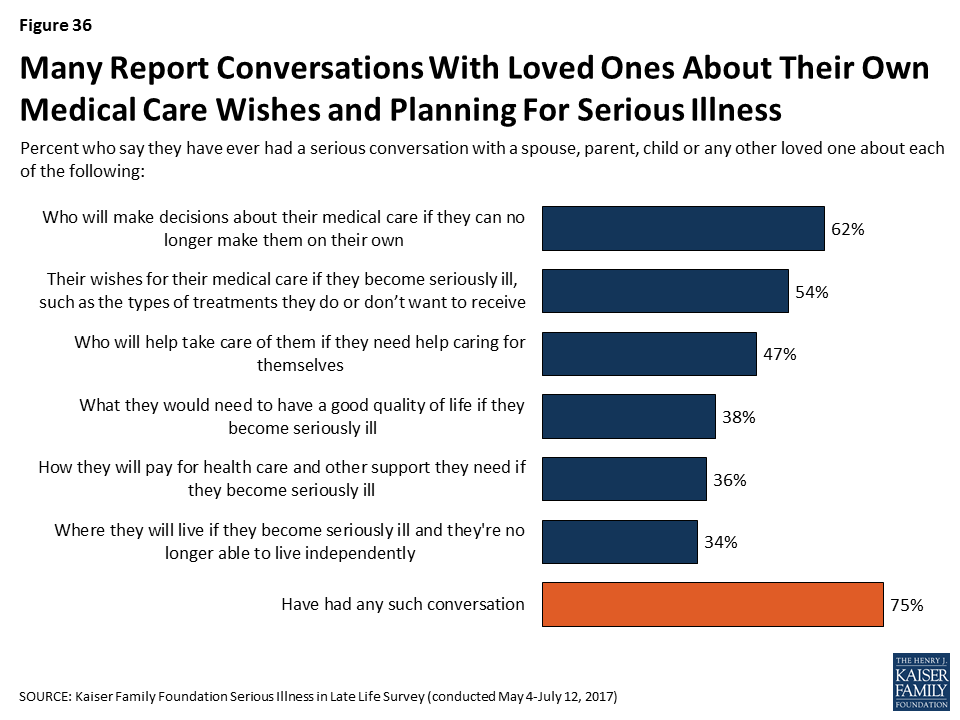

However, Many say they’ve talked about these things with their family

Although most of the public says they don’t have a document outlining their wishes or who they would want to make decisions for them if they were to become seriously ill, many do say they have had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child, or other loved one about a number of different aspects of planning for potentially becoming seriously ill. More than half say they’ve had a serious conversation with a loved one about who will make medical decisions if they can no longer do so on their own (62 percent) or about their wishes for medical care if they become serious ill (54 percent). About half say they have talked with a loved one about who would help take care of them if they needed help caring for themselves (47 percent). Less frequently reported types of conversations include what they would need to have a good quality of life while seriously ill (38 percent), how they would pay for health care and other support they might need if seriously ill (36 percent), and where they would live if they’re no longer able to live independently (34 percent). However, many still say they have not had discussions about some of the specific topics experts say are important parts of planning for serious illness.

It’s particularly notable that one of the types of conversations that is less often reported is about finances, the aspect that may take the most advanced planning and one that ties into several of the other aspects such as access to housing and support services.

Generally, older people are more likely than younger adults to report having these types of conversations with loved ones. Those who are 65 or older who themselves are dealing with serious illness are no more likely than their peers in better health to say they’ve had these types of conversations with a family member.

| Table 4: Serious Conversations with a Family Member About Planning for Serious Illness, by Age | ||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child or any other loved one about each of the following: | By Age | Serious Illness | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | Older adults (65+) with serious illness | Older adults (65+) without serious illness | |

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 40% | 59% | 69% | 82% | 80% | 83% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 38 | 46 | 61 | 71 | 70 | 71 |

| Who will help take care of them if they need help caring for themselves | 31 | 40 | 55 | 65 | 66 | 65 |

| What’s needed for a good quality of life if seriously ill | 25 | 35 | 43 | 48 | 44 | 48 |

| Where they’ll live if seriously ill | 17 | 29 | 39 | 55 | 54 | 55 |

| How to pay for health care and other support if seriously ill | 22 | 32 | 43 | 47 | 38 | 48 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 59 | 71 | 80 | 90 | 92 | 90 |

But, those who have some connection to serious illness, either with a loved one currently facing illness or knowing someone who died after a period of illness are more likely to say they’ve talked about some of these things. For example, 58 percent of those who say they have a family member or close friend that died after a period of serious illness say they have discussed their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill with a family member, compared to 43 percent of other adults. In addition, those who say their family talked about death at least occasionally when they were growing up are more likely to report having at least one of these types of conversations with family members than those who report talking about death less frequently.

| Table 5: Serious Conversations with a Family Member About Planning for Serious Illness, by Experience with Illness | ||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a spouse, parent, child or any other loved one about each of the following: | Recent experience with serious illness of a family member | Has a family member or close friend who has died after a period of serious illness | Talked about death growing up | |||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Occasionally/Fairly Often | Rarely/never | |

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 68% | 61% | 66% | 54% | 65% | 59% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 56 | 53 | 58 | 43 | 57 | 50 |

| Who will help take care of them if they need help caring for themselves | 54 | 46 | 50 | 41 | 51 | 43 |

| What’s needed for a good quality of life if seriously ill | 42 | 37 | 41 | 30 | 43 | 32 |

| Where they’ll live if seriously ill | 41 | 33 | 38 | 26 | 37 | 31 |

| How to pay for health care and other support if seriously ill | 42 | 35 | 39 | 29 | 40 | 31 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 79 | 74 | 79 | 66 | 80 | 69 |

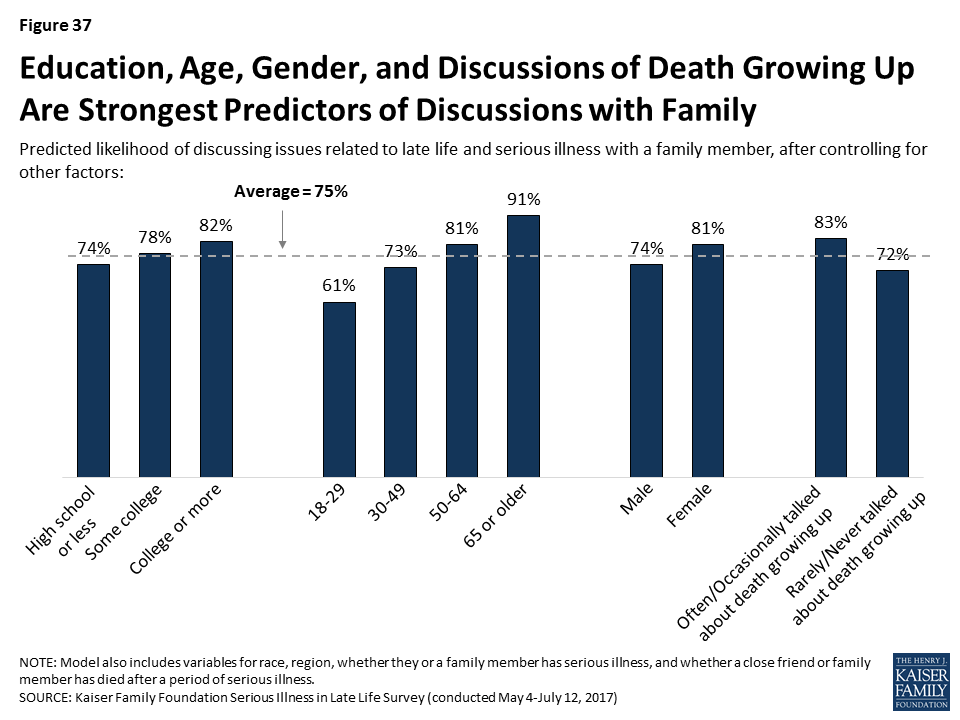

A regression analysis shows that the factors most associated with discussing these issues with family members, are higher levels of education, being older, being female, and having discussed death with family growing up at least occasionally, even after controlling for race/ethnicity, region, knowing someone who has died after a period of serious illness, and being personally seriously ill. Age is the most influential factor, even after considering other personal characteristics.

Most Say They Have Discussed These Issues With Their Family More Than Once

People who report having conversations with family members about preparations for serious illness say they’ve had such conversations repeatedly, and recently. Experts consider both to be an important part of planning for serious illness because wishes may change with time or as circumstances change. About half of the public say they’ve discussed these issues with loved ones more than once, while 17 percent say they’ve only discussed them once. Most of those who report talking with their family about these issues say they’ve discussed them within the past year (48 percent of the public overall), particularly those who say their health is fair or poor (59 percent).

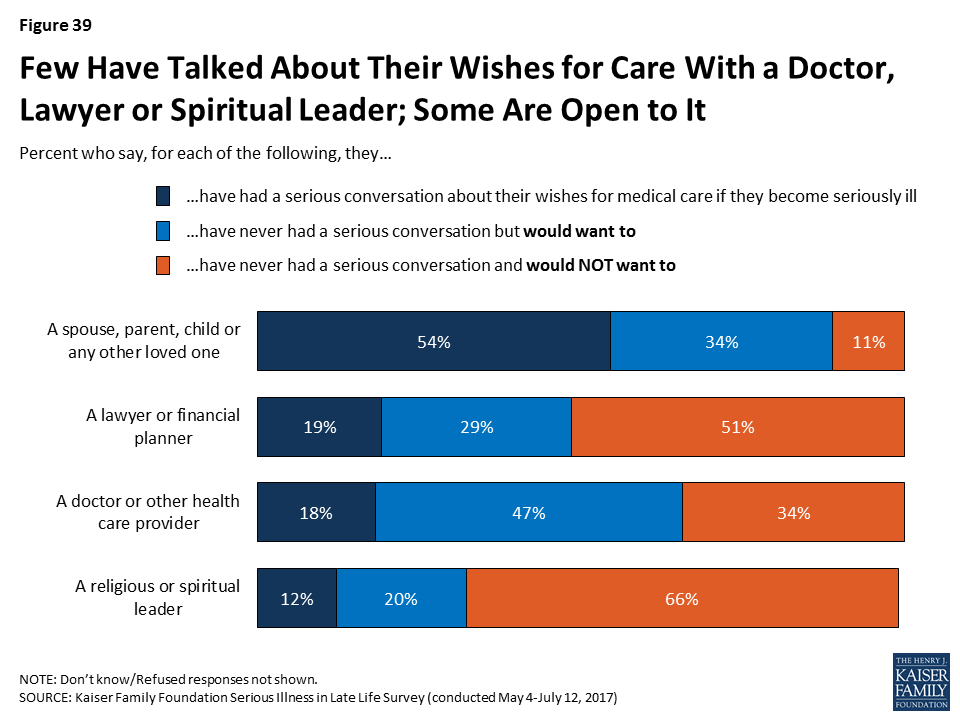

Relatively Few Say They Have Talked About Preparing for Serious Illness with Medical Providers, Lawyers, Financial planners, or Religious Leaders

Doctors and other medical providers can play an important role in helping people fulfill their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, however relatively few say they’ve talked to a medical provider about who would make decisions for them (23 percent), what sort of medical care they would want (18 percent), or where they would like to receive care if they became seriously ill (11 percent). Older people and people in fair or poor health are more likely to report having these types of conversations with a doctor, but still just about half of older people say they’ve talked about any of these issues.

| Table 6: Serious Conversations with Doctors or Other Health Care Providers about Planning for Serious Illness, By Age and Health Status | |||||||

| Percent who say they have ever had a serious conversation with a doctor or other health care provider about each of the following: | Total | Age | Health Status | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | Excellent/Very good/Good | Fair/Poor | ||

| Who will make decisions about their medical care if they can no longer make them on their own | 23% | 18% | 19% | 23% | 37% | 22% | 30% |

| Their wishes for medical care if seriously ill | 18 | 9 | 11 | 19 | 34 | 16 | 24 |

| Where they would like to receive care if seriously ill | 11 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 20 | 10 | 17 |

| Yes to any of the above types of conversations | 31 | 24 | 23 | 30 | 51 | 28 | 41 |

Focus Group Insights: There are mixed reactions to how involved physicians should be in the planning process. Some people say they are resistant to talking with their doctors about planning for serious illness because they don’t want to think about dying while they’re at the doctors’. Others say they would prefer to get information from doctors that they can take home and consider, while others are open to conversations with providers they know well.

“Every time I go, [a doctor asks] do you have a do-not-resuscitate? And it makes me feel funny because I’m at the doctors and I don’t want to think about dying right now, thank you very much.

There are other individuals that can play a role in helping to shape or fulfill an individual’s wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, such as a lawyer or financial planner who can help create legal documents or savings plans and religious or spiritual leaders who can help individuals outline what’s important to them in sickness and dying. But conversations with these individuals about wishes for medical care are also relatively rare – 19 percent say they’ve talked with a lawyer or financial planner and 12 percent say they’ve talked with a religious or spiritual leader.

For those who haven’t had these types of conversations with their family, medical providers, lawyers or financial planners, or religious leaders, some say they would want to do so. For example, for the 46 percent who say they haven’t talked with a family member about their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, most say they would want to (34 percent of the public overall). Notably, half the public (51 percent) say they have not and do not want to discuss these issues with a lawyer or financial planner, and two-thirds (66 percent) say the same about discussions with a religious or spiritual leader.

Reports of Planning Among Family Members of Older Adults with Serious Illness

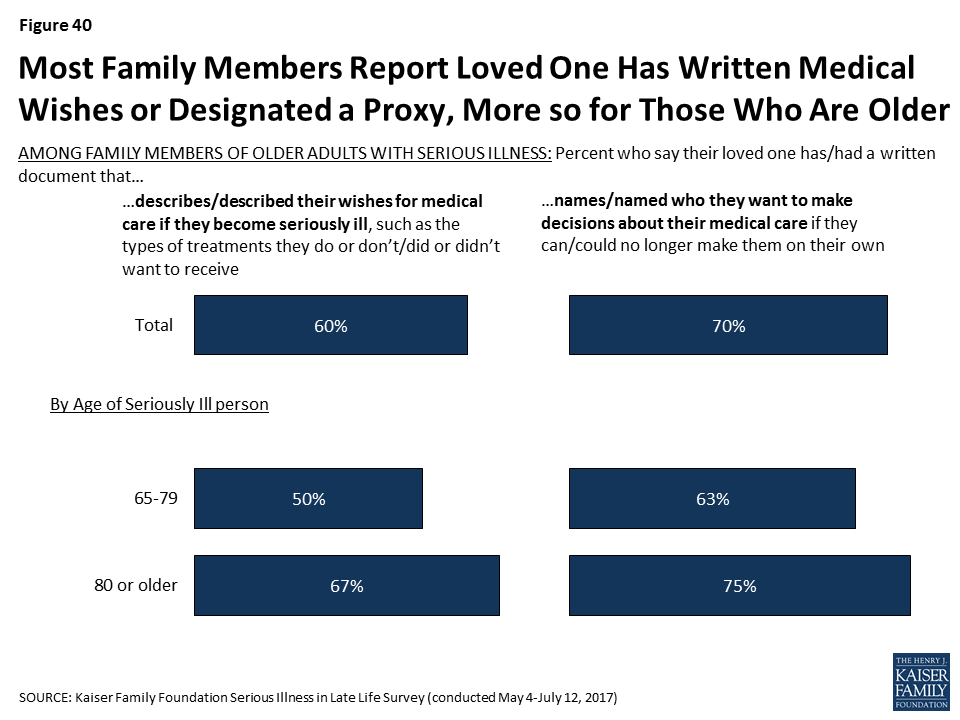

Among family members of older adults with serious illness, most report that their loved one has a document that describes their wishes for medical care (60 percent) or designates someone to make medical decisions on their behalf (70 percent). Those whose loved one is at least 80 years old are more likely than those whose family members are between ages 65-79 to say they have these written documents.

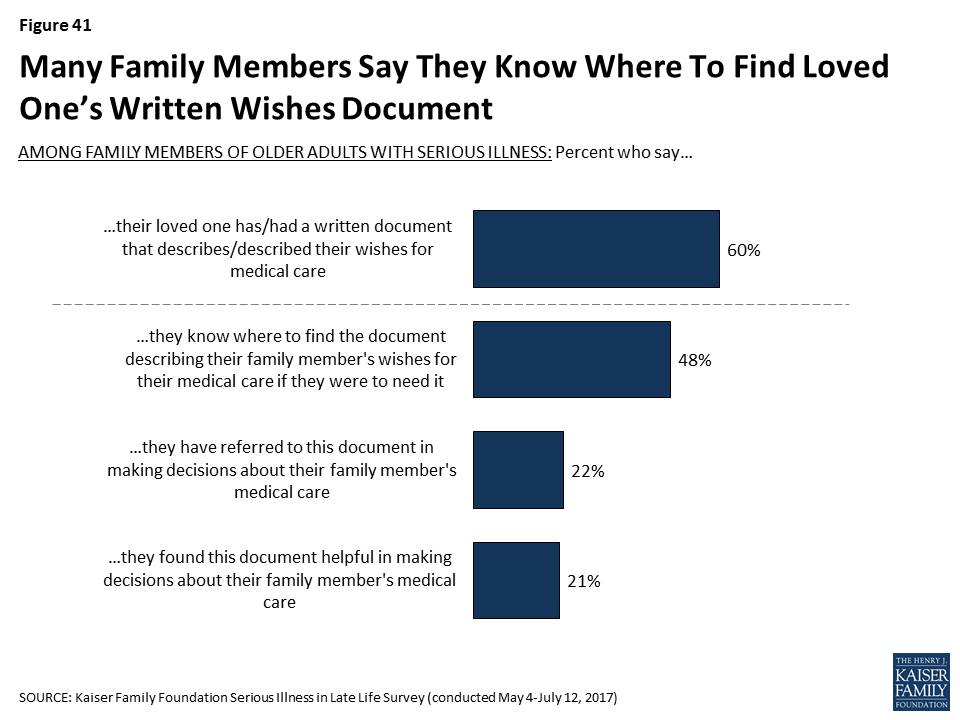

Family members, for the most part, say that if their loved one has a document describing their wishes for medical care, they know where to find it if they were to need it (80 percent of those whose family member has a written document, or 48 percent of all family members of older adults with serious illness). About one in five say they have referred to this document when making decisions about their family member’s care and nearly all of those who referred to the document say it was helpful to have (21 percent of family members overall).

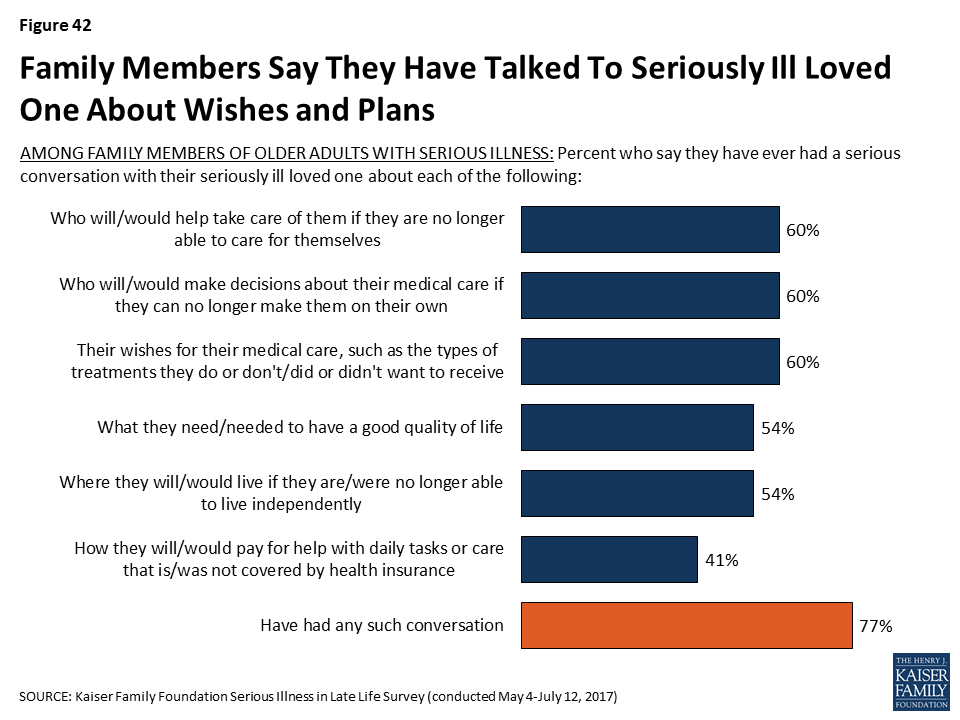

A majority of family members of older people with serious illness say that they have had a serious conversation about a variety of aspects of planning for late life and poor health. Six in ten family members say they’ve talked with their loved one about their wishes for medical care (60 percent), who would make decisions for them about their medical care if they were no longer able to make them on their own (60 percent), or who would help take care of them if they were no longer able to care for themselves (60 percent). Over half say they’ve talked with their family member about what they need to have a good quality of life while sick and where they would like to live if they can’t live independently (54 percent each). A smaller share, about four in ten, say they’ve talked to their family member about how they will pay for help with daily tasks or care that isn’t covered by health insurance (41 percent). It’s notable that here family members are also reporting their loved ones are talking less about finances than about some of their other expectations about late life and serious illness. Of course, family members are answering about their conversations with their loved one and it’s possible their loved one has had a conversation with a different family member.

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness say that staying at home is an attractive option until the reality of the level of care needed becomes apparent.

“She would have stayed at home all the way. She had always said, ‘Don’t ever put me anywhere. I want to always be at home.’ We’d always agreed to that until we were in that position. I never thought I would put her anywhere else, ever.”

Understanding And Following Loved Ones Wishes

Most family members of older adults with serious illness say they know or knew exactly what their loved one’s wishes for medical care are or that they have a pretty good idea. And, for those that say they don’t really know their loved one’s wishes, eight in ten (83 percent) say that there’s another family member that knows their wishes better than they do. Writing wishes down and talking about them appears to make a big difference; family members whose loved one has a written document outlining their wishes are more than twice as likely to say they know exactly what their loved one wanted than those without such a document (53 percent versus 23 percent). And, family members who say they talked with their seriously ill loved one about their wishes are more than three times as likely than others to say they know exactly what their loved one wanted (58 percent vs. 16 percent). Those family members that are designated as their loved one’s proxy or help their loved one with daily activities or other types of assistance are also more likely to say they know exactly what their seriously ill loved one wants for their medical care.

Focus Group Insights: Family members of those with serious illness appreciate when wishes are known and steps are taken to plan for serious illness. They expressed frustration when decision making is left up to them.

“She had living will and power of attorney but you know what it said? Unless it was putting her in a facility or she was on life support, in other words other than two options, it was up to us to decide. I’m like, ‘That’s not an answer.’ I think she’s one of those, if you avoid this subject then it’s not going to happen. That was very frustrating.”

Among individuals and family members of older adults with serious illness, nearly all say their or their loved ones wishes for their medical care are being very or somewhat closely followed, including more than six in ten who say they are ‘very closely’ followed. Those who say they have documents outlining their wishes are more likely to say their wishes are ‘very closely’ followed than those that do not (70 percent versus 54 percent), but there’s no difference for those who say they’ve talked about them compared to those who say they haven’t discussed their wishes (65 percent and 60 percent). However, as noted above, those family members who haven’t talked with their loved one about their wishes are less familiar with the care they want and therefore may not be able to accurately describe if their wishes for care are being closely followed.

Most family members of older adults with serious illness (68 percent) say there are rarely or never disagreements among family members about what sort of medical care their loved one should or shouldn’t receive, but about one in ten (9 percent) say there are often disagreements, and about two in ten (22 percent) say there are sometimes disagreements. Those who say their family member has had conversations with them or has a written document about their wishes are no more likely to say there are frequently disagreements among family members.

Planning: Financial Preparations

As noted above, just 36 percent of the public say they have personally had a serious conversation with a loved one about how they would pay for medical care and other needed services if they become seriously ill. While they may not be talking about this issue, about six in ten of the public say they feel very or somewhat confident they will have enough income and assets to last throughout their retirement years, even if they become seriously ill and need long-term support either at home or in a nursing home, but 37 percent are not confident they will. For those currently in or near their retirement years – those 65 or older – 74 percent feel confident they have enough income and assets for retirement, even if they become sick. And, for many older adults, this confidence may not be misplaced; more than six in ten of adults 65 or older are estimated to be financially secure, however this security declines for the oldest adults (75 or older), and still many are estimated to have more tenuous financial circumstances.5

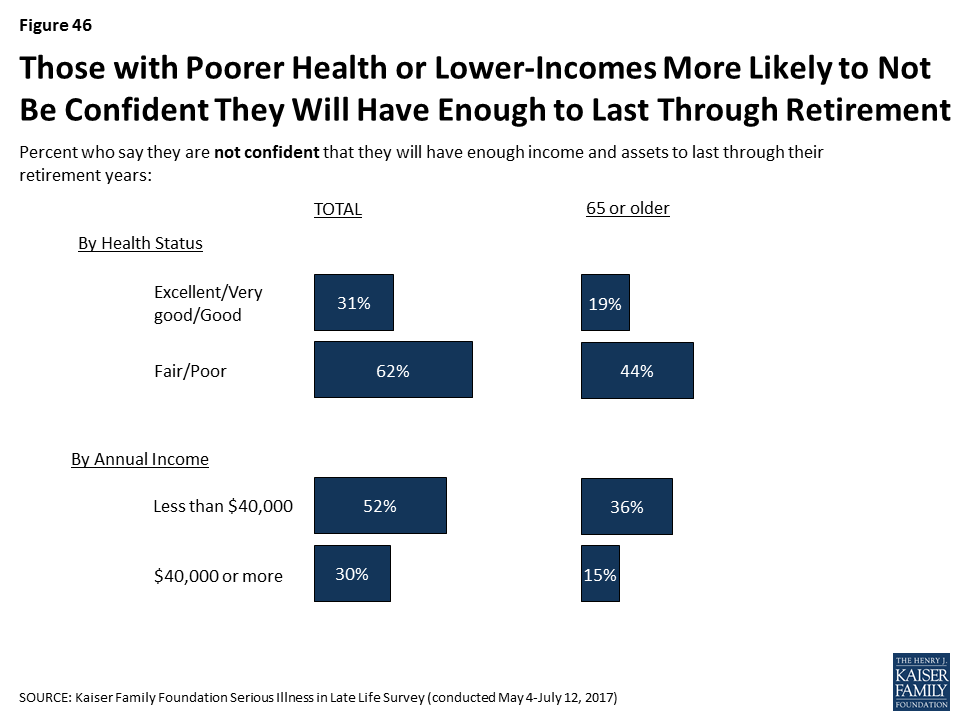

A striking 62 percent of those in fair or poor health and 52 percent of those making less than $40,000 annually say they’re not confident they’ll have enough income and assets to last through retirement. Looking specifically at those age 65 or older, roughly four in ten of those in fair or poor health or of those with annual incomes of less than $40,000 say they are not confident they will have enough income and assets to last throughout their retirement.

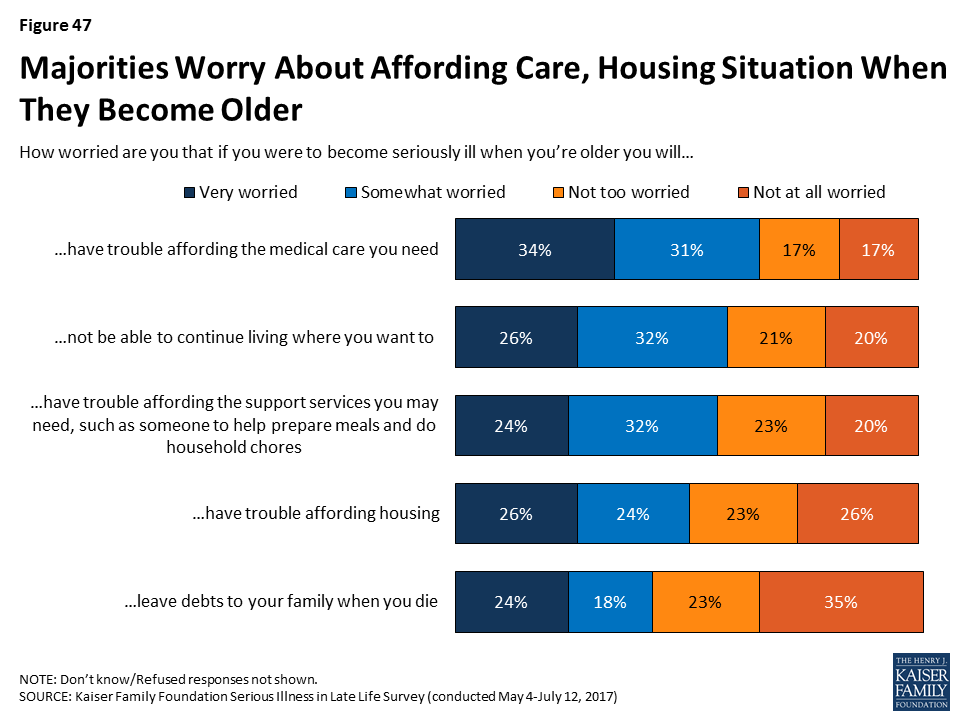

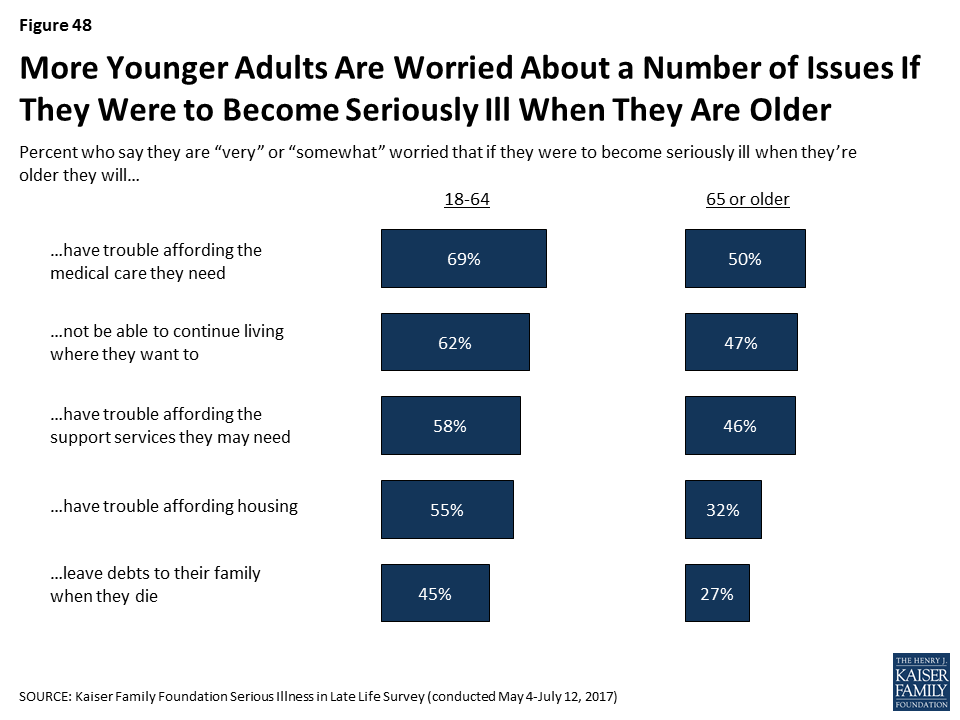

Even while many are confident they will have the income and assets to last through retirement in the event of illness, many say they are worried that if they were to become seriously ill when they are older they will have trouble affording needed medical care (65 percent), not be able to continue living where they want to (59 percent), have trouble affording support services (56 percent), have trouble affording housing (50 percent), or that they will leave debts to their family when they die (42 percent). Younger adults are particularly worried about these issues.

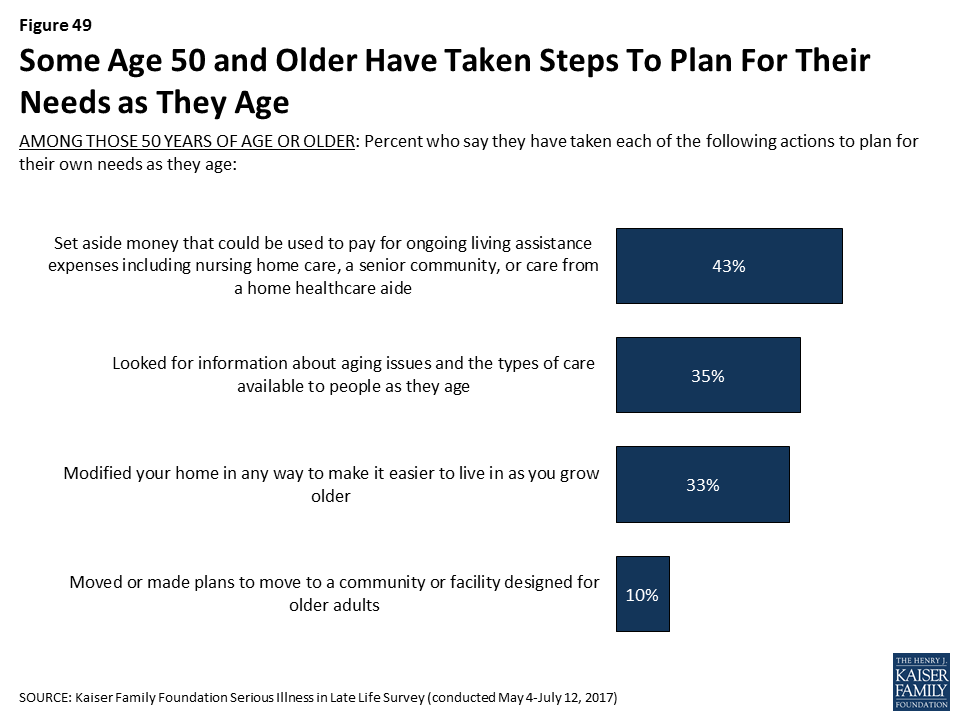

Steps Taken to Plan for Aging

Some people 50 and older report taking a variety of actions to plan for their own needs as they age, such as setting aside money that could be used to pay for ongoing living assistance (43 percent), looking for information about aging issues and the types of care available to people as they age (35 percent), modifying their home to make it easier to live in as they grow older (33 percent), or moving or making plans to move to a place designed for older adults (10 percent).

In addition, about half of those who have not yet retired (53 percent) say they are currently saving for retirement. Adults under 30 are much less likely to say they are saving (39 percent), but majorities of those 30 to 49 (59 percent) and 50-64 (57 percent) say they are, as well as about half (49 percent) of those 65 or older who are not already retired.

| Table 7: Steps Taken to Plan for Serious Illness | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | |

| AMONG THOSE 50 YEARS OF AGE OR OLDER: Percent who say that in order to plan for their needs as they age they have… | ||||

| …Set aside money that could be used to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses | — | — | 36% | 52% |

| …Looked for information about aging issues and the types of care available to people as they age | — | — | 28 | 43 |

| …Modified your home in any way to make it easier to live in as you grow older | — | — | 28 | 40 |

| …Moved or made plans to move to a community or facility designed for older adults | — | — | 7 | 13 |

| AMONG THOSE WHO ARE NOT RETIRED: Percent who say they are… | ||||

| …Currently saving for retirement | 39 | 59 | 57 | 49 |

Misconceptions About The Role of Medicare in Late Life

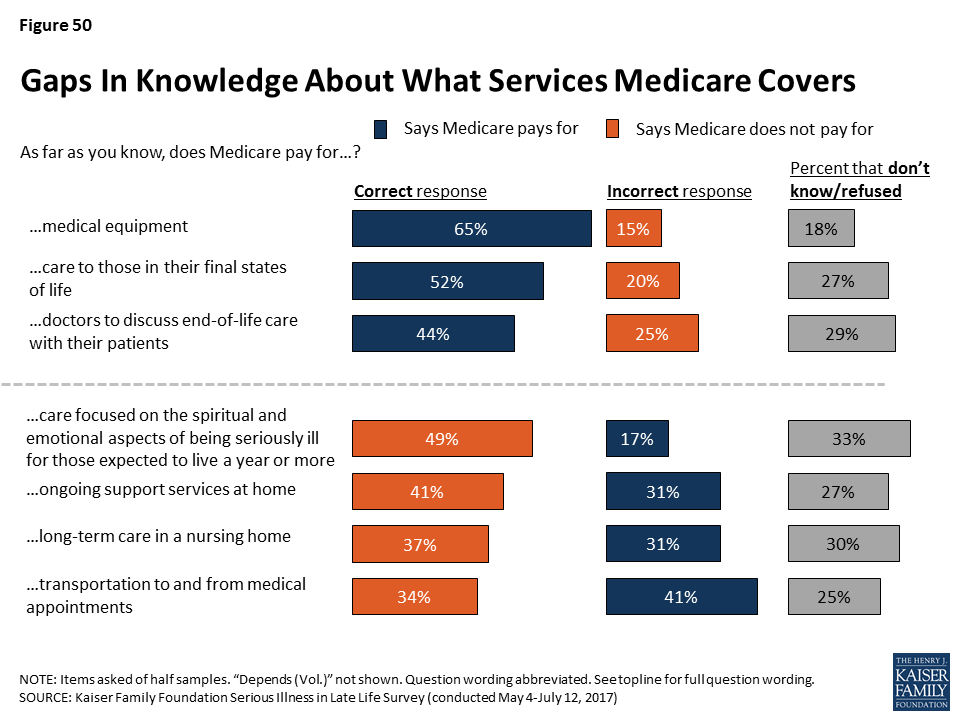

Other surveys have shown that much of the public expects to rely on Medicare when they get older.6 However, there are misconceptions about what Medicare does and does not cover that can leave people ill prepared to handle expenses they have to pay out of pocket. Many are correctly aware that Medicare covers medical equipment, such as wheelchairs and other assistive devices (65 percent), care to those in their final stages of life (52 percent), and doctors’ discussions with patients about end-of-life care (44 percent). However, about three in ten incorrectly say Medicare covers ongoing support services at home, such as someone to help prepare meals and do household chores, or that it covers long-term care in a nursing home. Four in ten incorrectly say it covers transportation to and from medical appointments for those who can no longer drive. About two in ten incorrectly say Medicare covers care that focuses on the spiritual and emotional aspects of living with a serious illness for those who are expected to live a year or more.

Section 4: Differences By Race/ethnicity

To better understand how views of and experiences with serious illness vary across race/ethnicity, the following section highlights some of the areas where attitudes and experiences diverge for black, Hispanic, and white adults. However, in many areas, there are few differences across these racial and ethnic groups.7

Older Black Adults Are Less Likely To Report Having Documented Wishes

Across races, nearly everyone thinks it is important to have documents describing wishes for medical care and designating someone to make decisions on one’s behalf. But there is less agreement on when the best time to complete these documents is in adulthood. Black adults skew towards believing people should name a health care proxy in their younger years – 35 percent of people who are black say it should be when a person turns 18 and another 23 percent of people who are black say it should be when they get married. On the other hand, over a third of Hispanic adults (36 percent) say that a person should first write something down about who they would want to make decisions for them when they are diagnosed with a serious illness. Interestingly, Hispanic adults who are in fair or poor health (51 percent), female (44 percent), or have lower-incomes (earning less than $40,000 per year) (43 percent) are more likely than other Hispanic adults to say it should be done when a person is diagnosed with a serious illness.

Overall, black and Hispanic adults are less likely than white adults to report having documents describing their wishes or naming a health care proxy, a finding that is at least in part related to the fact that black and Hispanic adults tend to be younger, have lower levels of education, and have lower incomes than white adults – all factors, as noted above, that are associated with being less likely to have these types of documents. However, focusing only on those 65 or older, about half of older Hispanics and more than six in ten older whites say they have either type of written document, but older blacks are less likely than their white and Hispanic counterparts in reports of having these types of documents. Just 19 percent of blacks adults ages 65 or older say they have a document describing their wishes and about a third (35 percent) have a document naming a health care proxy.8

Black and Hispanic Adults More Likely Than Whites to Report Resistance To Thinking about Sickness and Death

Reports of which barriers keep people from creating these types of documents are similar across racial and ethnic groups, except black and Hispanic adults who do not have these documents are more likely than white adults to express resistance to thinking about sickness and death. Roughly four in ten black and Hispanic adults say the fact that they ‘don’t want to think about sickness and death’ is a major reason they do not have a written document, compared to 21 percent of whites.

| Table 8: Barriers to Written Documents Outlining Wishes Varies Little by Race | ||||

| AMONG THE 66% OF THE PUBLIC WHO DO NOT HAVE A WRITTEN DOCUMENT THAT DESCRIBES THEIR WISHES FOR MEDICAL CARE IF THEY BECOME SERIOUSLY ILL: Percent who say each of the following was a major reason why they have not written down their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill: | Total | Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | Black | Hispanic | ||

| There are too many other things to worry about right now | 36% | 35% | 33% | 43% |

| You’re too young or that’s a long ways off | 32 | 32 | 26 | 34 |

| You haven’t thought about it | 32 | 29 | 34 | 39 |

| You don’t want to think about sickness and death | 27 | 21 | 37 | 42 |

| You’re worried you might change your mind about what you want | 13 | 10 | 20 | 14 |

| You want your doctors to make the decisions for you when needed | 11 | 9 | 10 | 16 |

People who are black (77 percent) or Hispanic (76 percent) that do not report having written down their wishes are somewhat less likely than people who are white (89 percent) to say they think there is someone who understands their wishes for medical care if they become seriously ill, but still large majorities do.

Across Race/Ethnicity, Many Report Talking To Loved ones About These Issues

White adults are more likely than black and Hispanic adults to report having conversations with their family about their wishes, about who will make decisions on their behalf, and about who will help take care of them. Again, these differences are related to demographic differences such as age and income. However, similar shares of older Hispanics, older whites, and to a somewhat lesser extent, older blacks, report they have had these types of conversations with family.

| Table 9: Serious Conversations with Family Member about Planning for Serious Illness, By Race/Ethnicity and Age | ||||||||||