Medicaid Managed Care Plans and Access to Care: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation 2017 Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans

Executive Summary

Managed care organizations (MCOs) cover nearly two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries nationwide,1 making managed care the nation’s dominant delivery system for Medicaid enrollees. As the entities responsible for providing comprehensive Medicaid benefits to enrollees by contracting with providers, plans play a critical role in shaping access to care for Medicaid enrollees. Many plan actions are dictated by state policy or contracting requirements; however, plans also have some flexibility to design payment and delivery systems and structure enrollees’ experiences using their coverage. To understand how Medicaid managed care plans approach access to care and the challenges they face in ensuring such access, the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a survey of plans in 2017. Highlights from the full survey report are below:

KFF conducted a national survey of #Medicaid managed care organizations to understand how plans approach access to care. #Managedcare is the dominant delivery system for Medicaid beneficiaries, with #MCOs covering nearly two-thirds of enrollees.

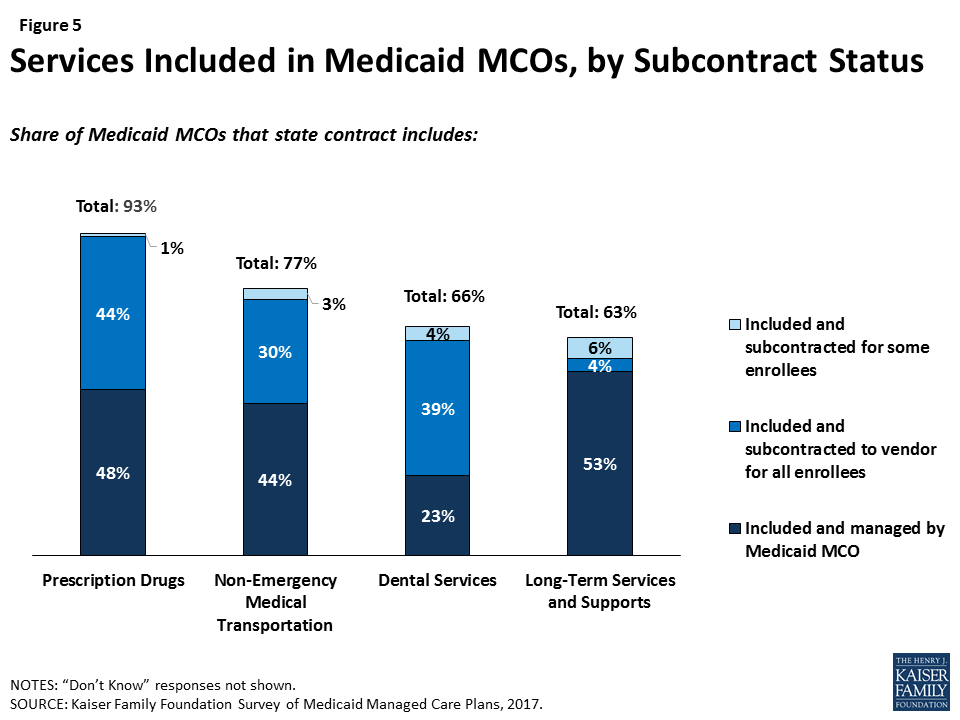

Most plans surveyed are focused on serving the Medicaid population, serve a broad range of enrollee groups, and provide a range of services. Most (70%) plans responding to the survey have been participating in the Medicaid program for 10 or more years, a plurality (45%) are private non-profit, and the vast majority (73%) do not operate statewide.2 Medicaid enrollees comprise at least 75% of total health plan enrollment for nearly two-thirds of plans surveyed (64%). Among plans enrolling Medicaid expansion adults, only 38% also offer an Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace product. Most plans include prescription drugs (93%), non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT, 77%), dental services3 (66%), or long-term services and supports (LTSS, 63%) in their contract with the state; however, plans are likely to subcontract these services for at least some of their enrollees.

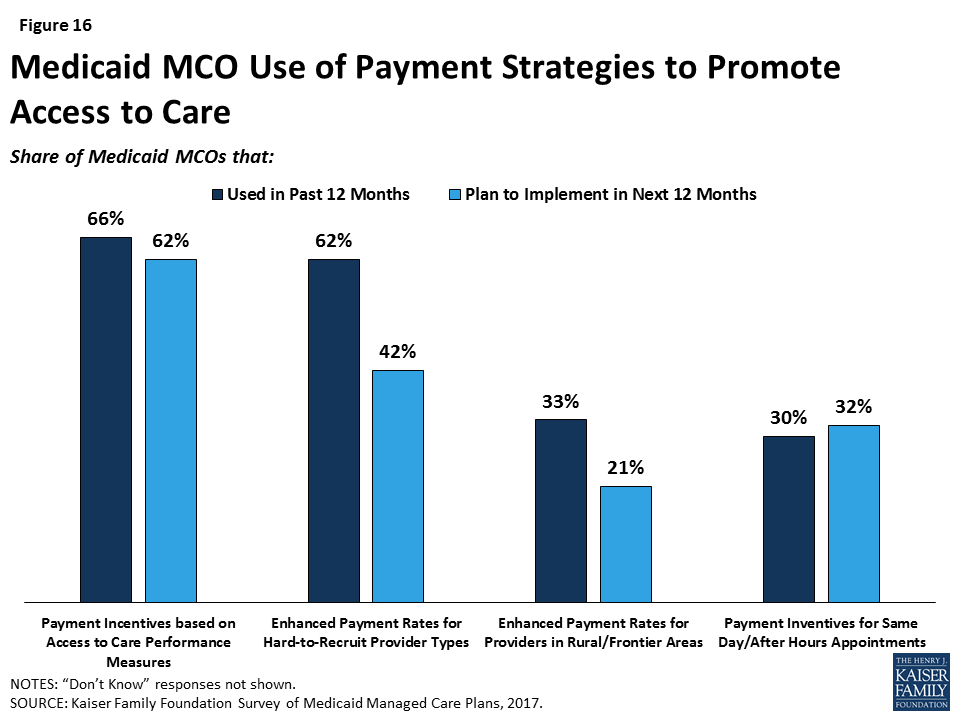

Plans reported challenges in recruiting specialists but pointed to provider supply shortages rather than low participation rates as a challenge to network adequacy. The most common activities that plans reported for monitoring network capacity were member/provider complaints or call center reports, feedback from regular member survey data such as the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), and monitoring out-of-network visits. Plans are more likely to cite market-wide provider supply shortages in certain specialties or certain geographic areas than low provider participation in Medicaid as a top challenge in ensuring access to care. A majority of plans said that they either already use or plan to use enhanced payment rates for hard-to-recruit provider types, and about a third of plans reported using or planning to use enhanced payment rates for providers in rural or frontier areas. More than two-thirds (68%) of plans reported using telemedicine in at least one clinical area.

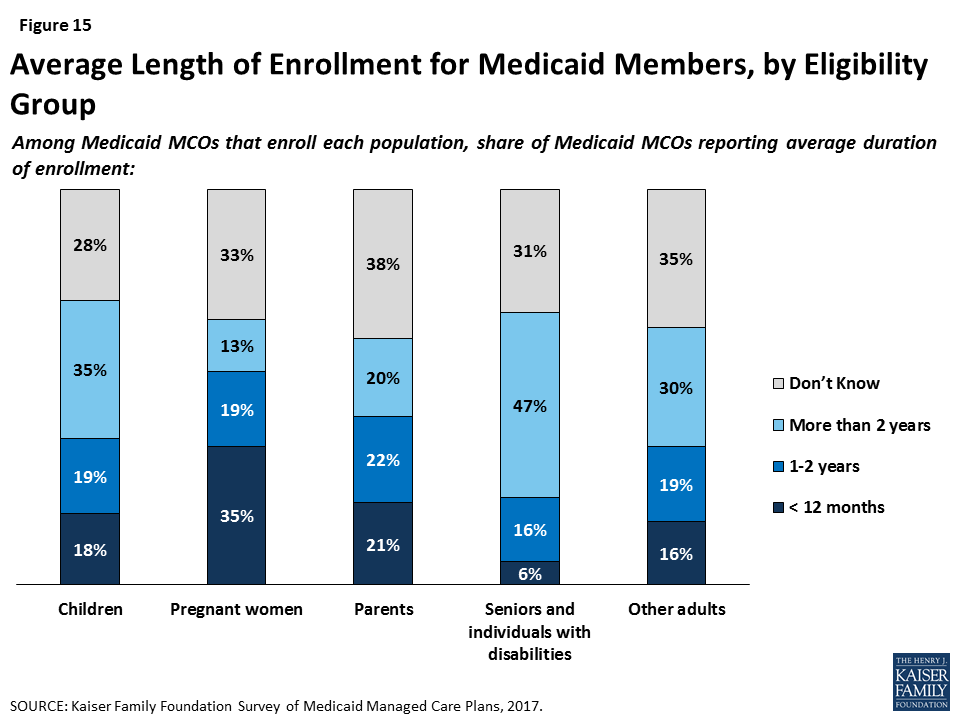

Plans are making efforts to engage high-risk members in their care, and nearly all plans surveyed also undertake activities to promote healthy behaviors or address social determinants of health. Most plans reported actively conducting health assessments or data analytics to engage members, particularly high-need members, in care. Almost all plans reported offering incentives for “healthy behaviors,” with the most common incentives for well-child care, prenatal visits, and postpartum care. Almost all plans (91%) reported activities to address social determinants of health, with housing, nutrition/food security, and education reported as top targets. Reflecting state and federal eligibility rules, plans reported relatively short enrollment duration for pregnant women, and plans in states that have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility for children reported longer enrollment duration among children.

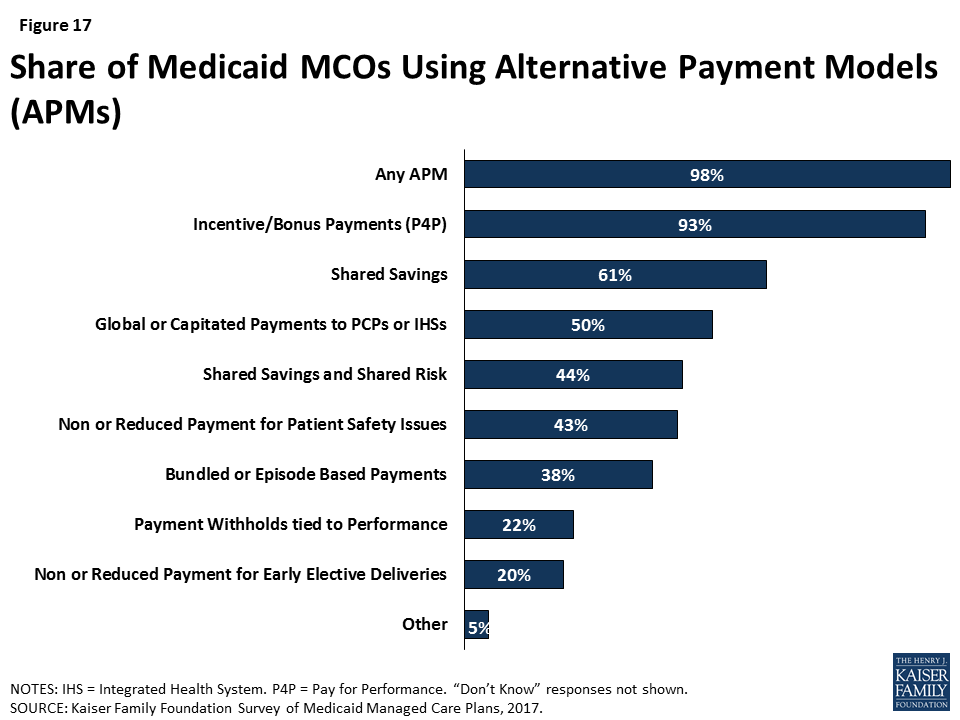

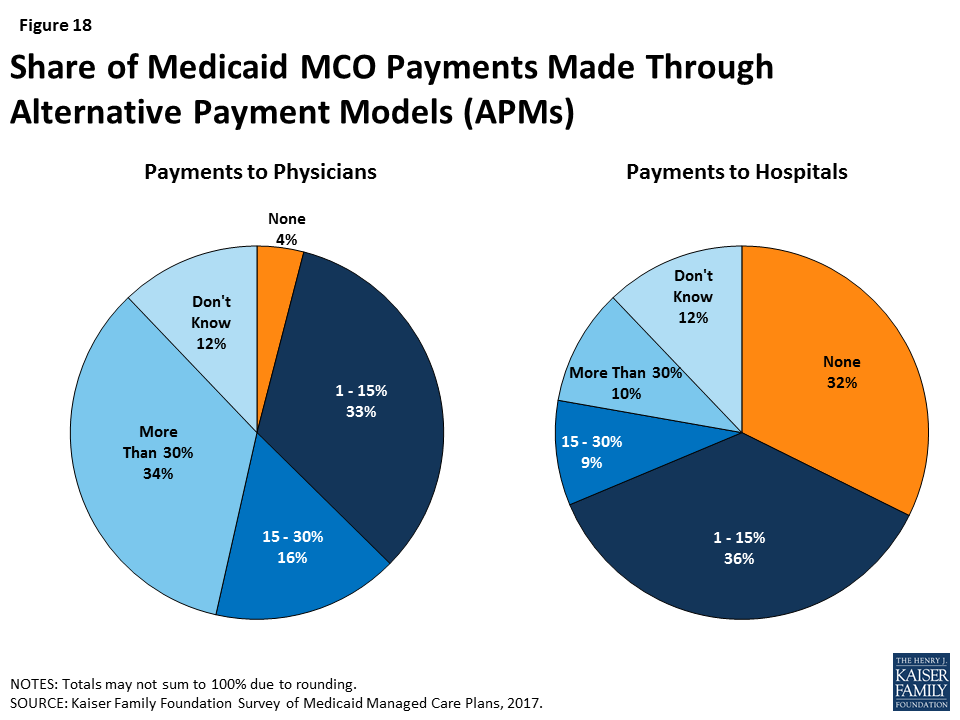

Nearly all responding plans have adopted at least one “alternative payment system” for quality, cost, or access outcomes, and survey respondents also are using a range of activities to coordinate and integrate care. Almost all plans (93%) still make fee-for-service (FFS) payments to at least some providers. Ninety-eight percent of plans reported using at least one alternative payment model (APM) for at least some providers. The vast majority of plans (93%) use incentives and/or bonus payments tied to performance measures. Fewer plans reported using bundled or episode-based payments (38%) or shared savings and risk arrangements (44%). Twenty-eight percent of plans reported contracting with an ACO. Physical and behavioral health integration ranks as the top priority for plans in ensuring access to care for members.

Plans reported concern about the potential access consequences of efforts to restructure Medicaid financing or implement new Medicaid waiver provisions. Likely reflecting long plan duration in the Medicaid market and focus on serving the Medicaid population, only a small share of responding plans indicated that they are likely to rethink their Medicaid participation if the ACA expansion is repealed or they are faced with limits on capitation rates. However, plans did report concern about the implications of current policy debates for member access. Plans were almost universally negative when responding to an open-ended question about federal Medicaid financing reform proposals (block grants or per capita caps). Responses described a multitude of anticipated beneficiary impacts, such as decreased enrollment, decreased or reduced benefits, and provider rate cuts that may lead to reduced provider participation/access. Some plans also specifically indicated that a block grant or per capita cap may put them at risk financially, lead to negative margins, or compromise the actuarial soundness of capitation rates. When asked to choose what, if any, potential impact various waiver provisions being considered or proposed by states would have on plans or enrollees, a majority of plans indicated that such provisions would have an effect on enrollee access to care or continuity of coverage. A majority of plans reported needing at least some additional guidance to implement many of the 2016 Medicaid managed care final rule provisions. However, nearly three-quarters of plans reported that the change in Administration has not caused them to put a hold on activities to implement provisions of the Medicaid managed care rule.

Looking Ahead: Managed care plans are on the front lines of efforts to facilitate access to care for Medicaid enrollees. In this role, plans both work directly with providers and enrollees and undertake efforts to facilitate connections between providers and enrollees. While many of these activities stem from contract provisions between states and plans, others are plan-initiated. Some of the goals of enrolling Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care plans are to promote coordinated care, help emphasize preventive care, and facilitate efforts to adopt “whole-person” delivery models that aim to address patients’ physical, mental, and social needs; however, policy changes under discussion that disrupt enrollment continuity or duration may inhibit plans’ ability to implement or realize these goals. While MCOs in this survey have long experience serving Medicaid enrollees, they face an uncertain future as they navigate how to move forward with new initiatives in the context of potential budget cuts, waivers, and changes to federal regulations.

Report: Introduction

Since the early 1980s, and particularly in recent years, states have increasingly used managed care to deliver services to Medicaid beneficiaries. The dominant model is comprehensive managed care, in which states contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) to provide comprehensive acute care — and in some cases long-term services and supports as well — to Medicaid beneficiaries and pay the MCO a fixed monthly premium or “capitation rate” for each enrollee. Historically, states largely limited risk-based managed care to pregnant women, children, and parents, but states are increasingly including Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs, including people with disabilities and people over 65 years of age. Today, 39 states (including the District of Columbia) contract with comprehensive managed care plans to provide care to at least some of their Medicaid beneficiaries.4 Nationwide, MCOs cover nearly two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries,5 making managed care the nation’s dominant delivery system for Medicaid enrollees. As the entities responsible for providing comprehensive Medicaid benefits to enrollees by contracting with providers, plans play a crucial role in shaping access to care for Medicaid enrollees.

To understand how Medicaid managed care plans approach access to care and the challenges they face in ensuring such access, the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a survey of plans in 2017. The survey aimed to capture information on plans’ policies, procedures, and strategies for ensuring access to care as well as their priorities and challenges in facilitating access. The survey was fielded among all plans in operation during the survey (2017) and reference (2016) periods.6 The final sample of nearly 100 plans across 31 states captured approximately 40% of Medicaid beneficiaries in comprehensive MCOs. Additional detail on the methods underlying the survey and characteristics of plans, as well as full survey results, are available in Topline & Methodology Report, and a brief overview of the survey methods is below.

Overview of Survey Methods

The Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) collected information about MCO policies, procedures, challenges, and priorities regarding enrollees’ access to care. The survey also collected information on key characteristics of MCOs and the impact of current policy developments on MCO operations. The Kaiser Family Foundation contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago to develop and field the web-based survey.

The target population included all comprehensive Medicaid MCOs in the 39 states (including DC) that use comprehensive managed care for any Medicaid enrollees. Eligible plans included any plan that had a 2016 Medicaid MCO contract and was active during the data collection period in 2017. Data collection began on April 17, 2017 and concluded on September 21, 2017. The survey was distributed by email to executives at each MCO. Outreach to plan contacts occurred multiple times throughout the field period to encourage participation. The survey was offered in English only. A PDF of the survey instrument was provided to all respondents along with a link to the web-based survey.

The response rate was calculated using American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) standards for establishment surveys. The final survey response rate was 34.3% (95 complete surveys out of 277 eligible plans). Three additional plans partially completed the survey. Comparison of the plans represented in data reporting to the universe of eligible plans indicates that responding plans represent 31 of 39 states and 38% of total comprehensive Medicaid managed care enrollment. Reporting plans were slightly more likely than the universe of plans to be non-profit and in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA. Compared to the universe of eligible plans, reporting plans were similar in average Medicaid enrollment, geographic distribution, and state Medicaid MCO penetration.

Report: Plan Characteristics, Enrollees, And Services

As Medicaid managed care has developed over the past several decades, the plans serving Medicaid enrollees have developed as well. Some of these changes reflect changing federal rules and state policies, which allowed plans to focus primarily on Medicaid, permitted states to require mandatory enrollment in managed care, and expanded the geographic areas and beneficiary groups included in managed care. The characteristics of plans serving Medicaid enrollees — such as organization type, lines of business, geographic scope, and experience in Medicaid — may influence or reflect plans’ ability to ensure enrollees’ access to care. For example, some Medicaid enrollees have special needs that may be best served by small, focused plans specifically designed to care for populations with complex needs or by plans with long experience serving the Medicaid population. Other Medicaid beneficiaries may have health needs similar to the population covered by private insurance, or they may be covered by more than one type of insurance, and could be best served by plans that span public and private markets. In addition, plans that cover a broad range of services may help facilitate coordination of care, while plans that cover a more limited range of services may focus attention on acute care and rely on specialty plans or subcontractors to manage other services.

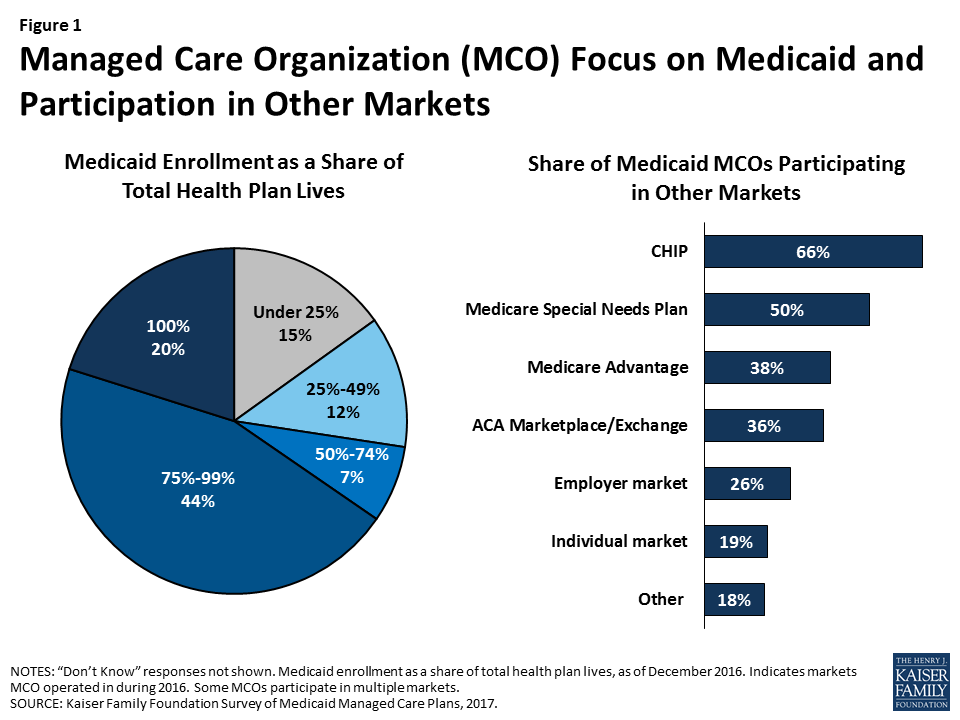

Managed care plans enrolling Medicaid beneficiaries are typically focused on serving this population or other markets serving low-income individuals enrolled in public coverage. Nearly two-thirds of responding plans (64%) are Medicaid-only (100% of plan enrollment consists of Medicaid enrollees) or Medicaid-dominated (Medicaid accounts for 75% to 99% of total plan enrollment); we refer to these two groups of plans (those for whom Medicaid accounts for at least 75% of total enrollment) as “Medicaid focused” plans. An additional 7% of plans reported that Medicaid accounts for at least half of total plan enrollment (Figure 1). MCOs that participate in other lines of business besides Medicaid are more likely to offer products in public insurance (CHIP, Medicare) or ACA marketplaces than in the employer or individual market (Figure 1). Thus, these plans may have expertise in serving the unique needs of low-income populations, serving groups whose coverage status may change with modest income fluctuations, or coordinating care across payers.

Still, only about a third of responding Medicaid MCOs also offer an ACA marketplace product and, even among plans enrolling Medicaid expansion adults, only 38% also offer an ACA marketplace product (data not shown). Similarly, only 38% of plans overall and 42% of plans that serve dual eligible individuals participate in the Medicare Advantage market that serves the general Medicare population. This pattern stands in contrast to children’s coverage, in which 69% of plans that serve children also offer a CHIP product,7 and dual eligible individual’s coverage, in which 62% of plans that enroll dual eligible individuals also offer a Medicare special needs plan. These differences may reflect state contracting requirements, different plan rules in different markets, or plans’ own market strategies.

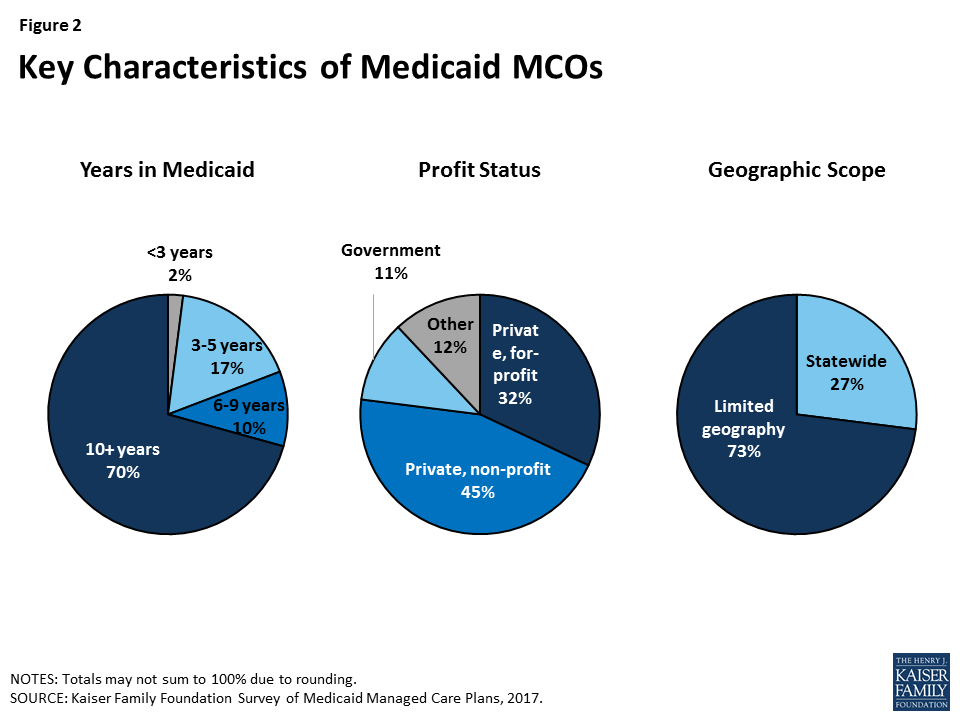

Most Medicaid MCOs responding to the survey have a long history of participating in Medicaid, are likely to be non-profit, and are not offered statewide (Figure 2). Most (70%) plans have been participating in the Medicaid program for 10 or more years, a plurality (45%) are private non-profit, and the vast majority (73%) do not operate in all geographic areas of the state.8 Geographic scope of plans likely reflects state contracting policy, as many states contract with plans at the county or regional level rather than the state level. Plans in which Medicaid enrollment accounts for at least 75% of covered lives (“Medicaid-focused plans”) were less likely than other plans to be private non-profit plans (34% versus 63%) and more likely to be government plans (15% versus 5%), other types9 (17% versus 3%), or private for-profit (34% versus 26%) (data not shown). In addition, Medicaid-focused plans were more than twice as likely as other plans to be offered statewide (34% versus 13%). There were not differences in length of time in the Medicaid market for Medicaid-focused plans versus other plans.

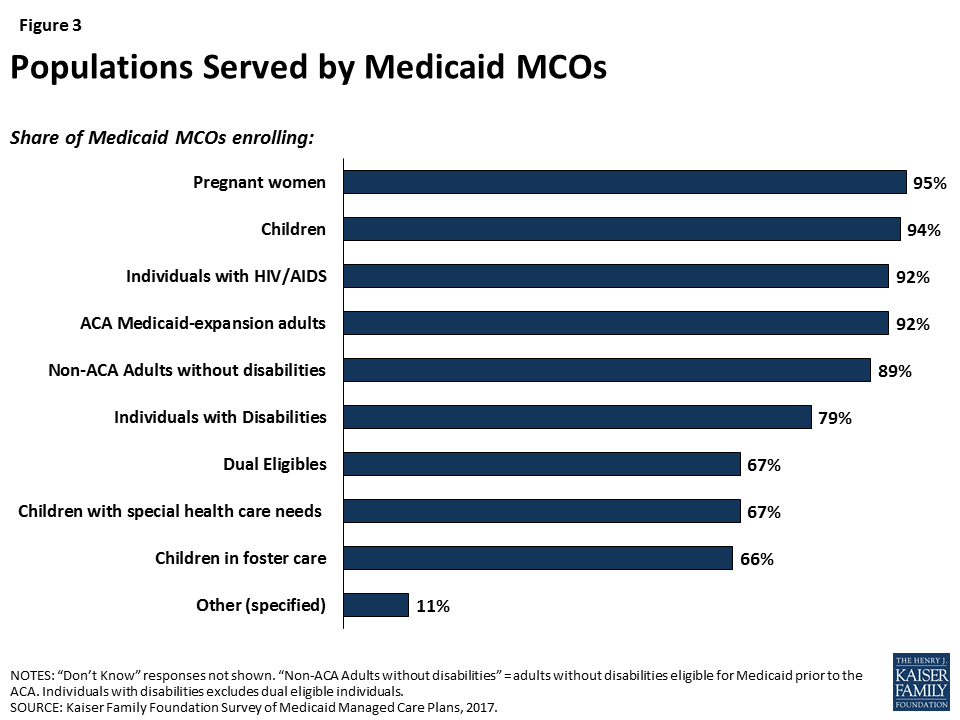

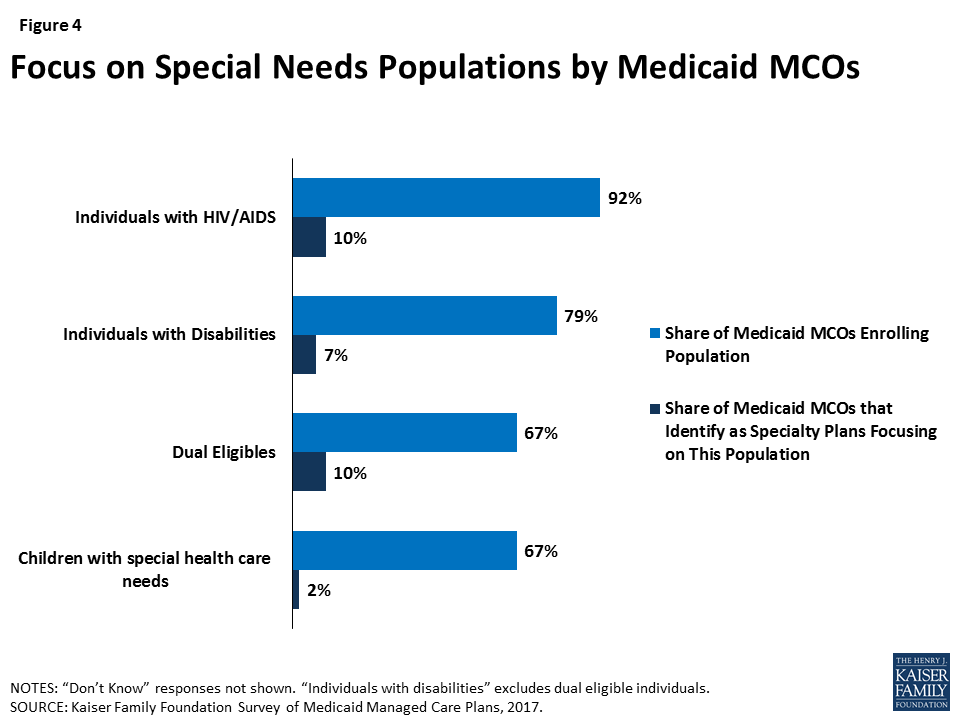

Comprehensive Medicaid managed care plans are serving a broad range of populations, including many populations with special health needs. Though plans are focused in terms of the geographic market they serve, they typically serve a broad range of enrollee groups. Nearly all responding plans enroll pregnant women, children, non-disabled adults, and ACA adults (if they operate in a state that expanded Medicaid) (Figure 3), groups that private insurance also generally enrolls. However, most Medicaid plans also enroll special needs populations such as people with HIV/AIDS, people with disabilities, dual eligible individuals, children with special health care needs, and children in foster care. Some Medicaid plans identify as “specialty plans” designed specifically to serve a targeted population, but, notably, rates of covering special needs populations were high even among non-specialty plans (Figure 4). For example, 92% of plans cover people with HIV/AIDS, but only 10% of plans identify as specialty plans focused on this population (Figure 4). Similarly, all self-identified specialty plans enroll multiple populations, including populations outside of their specialties.

Although responding plans’ contracts with states frequently include comprehensive Medicaid benefits including physical health, behavioral health, prescription drugs, dental services, and long-term services and supports (LTSS), many plans subcontract some of these services to other entities. Some states “carve out” certain benefits from their contracts with Medicaid MCOs. These carved-out benefits may be provided and financed under a separate state contract with a limited-benefit prepaid health plan (PHP) or on a fee-for service basis. Alternatively, states may include these services in their contracts with MCOs, who in turn decide whether to manage them in-house or subcontract with PHPs to provide such benefits. State carve-outs or plan subcontracting may fragment care, as enrollees (and payers) have multiple plans to coordinate; on the other hand, carve-outs and subcontracts could place management of a particular benefit in the hands of a plan specifically focused on that clinical area.

Most responding plans reported that their state contracts include a broad range of services, including services that states most commonly opt to carve-out. Specifically, most plans include prescription drugs (93%), non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT, 77%), dental services10 (66%), or LTSS (63%) in their contract with the state (Figure 5), and over a third of plans (36%) include all four of these services (data not shown). However, plans are likely to subcontract these services for at least some of their enrollees, and only 7% of plans cover all four services and manage them internally (i.e., don’t subcontract) (data not shown). Plans are more likely to subcontract dental, NEMT, and prescription drug services than LTSS. This pattern may reflect state and plan efforts to integrate LTSS and acute care services. Notably, all specialty plans for people with disabilities or dual eligible individuals cover LTSS, and plans (specialty or not) that serve dual eligible individuals are more likely to include LTSS than plans overall (72%, data not shown).

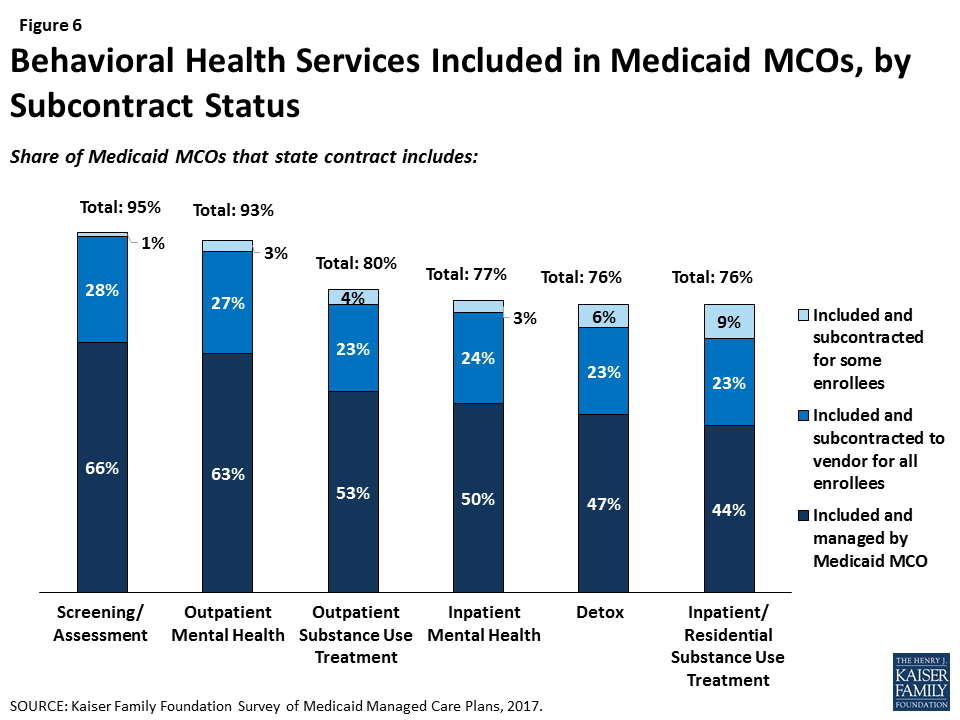

Similarly, a majority of responding plans’ contracts with states include at least some mental health or substance use treatment services, including inpatient and outpatient services (Figure 6). Plans whose state contract include behavioral health services are more likely to provide these services through their own plan (versus subcontracting), possibly indicating efforts to integrate physical and behavioral health services.

Report: Provider Networks And Access To Care

Though research indicates that, overall, most primary care providers and specialists accept Medicaid,11 provider participation in Medicaid is a subject of much debate. Providers are less likely to accept new Medicaid patients than new patients insured by other payers,12 and lower participation rates among some types of specialists remain an area of concern. In addition to provider participation, provider supply shortages in a particular state or region (especially rural areas) can affect enrollee access to care, as only 11 states currently meet at least two-thirds of their residents’ need for health professionals.13 Plan efforts to recruit and maintain their provider networks can play a crucial role in determining enrollees’ access to care through factors such as travel times, wait times, or choice of provider.

Plans report more challenges in recruiting specialty providers than primary care providers to their networks. Eight in ten plans that responded to the survey said that it is somewhat or very difficult to recruit adult (80%) or pediatric (81%) subspecialists to their networks, compared to 40% reporting such difficulty for primary care providers, 50% for obstetrician/gynecologists, and 32% for pediatricians (Figure 7). Among plans that contract with dentists, more than half reported difficulty in recruiting dentists.

Plans also reported high rates of difficulty in recruiting physician behavioral health providers to their network. Specifically, 85% of responding plans that contract with child or adolescent psychiatrists reported difficulty in recruiting these providers, and 83% that contract with general psychiatrists reported difficulty in recruiting them (Figure 8). These findings align with broader challenges with recruiting psychiatrists that extend across all payers, as psychiatrists accept Medicaid, private insurance and Medicare at lower rates than other specialists.14 In the survey, plans reported less difficulty in recruiting non-physician behavioral health providers such as clinical social workers, licensed therapists, or drug and alcohol counselors.

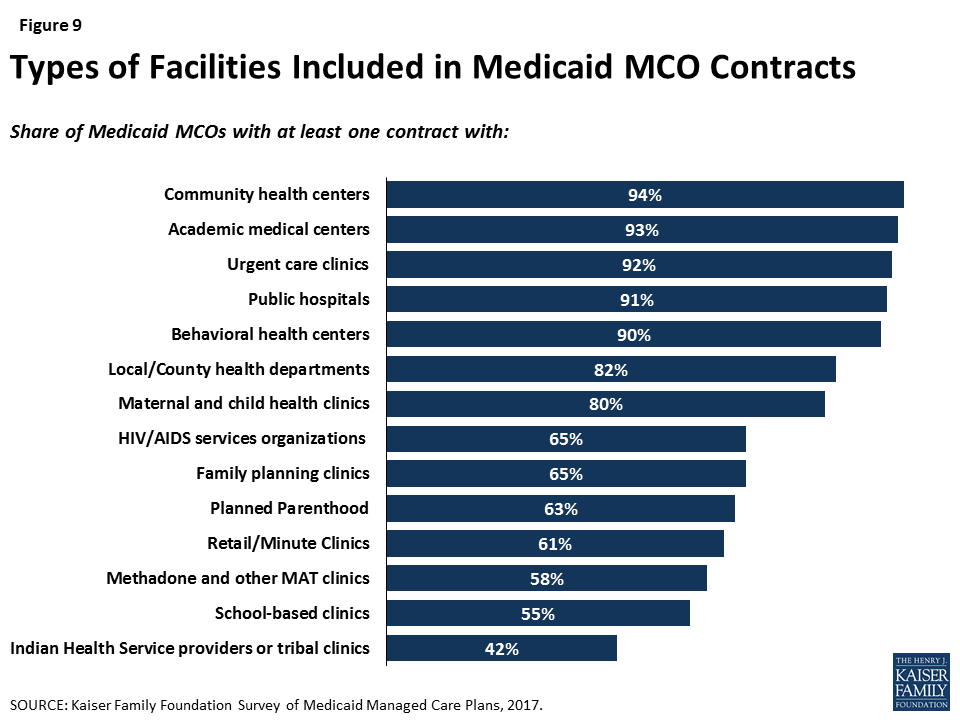

Similarly, plans reported contracting with a range of facility types, but some specialty facilities are less likely to be included in plan networks than general facilities. For example, at least nine out of ten responding plans reported contracting with general service facilities such as community health centers, academic medical centers, urgent care clinics, public hospitals, and behavioral health centers. Smaller shares — though still a majority — reported contracting with specialty facilities such as HIV/AIDS service organizations, family planning clinics or Planned Parenthood, or methadone clinics (Figure 9). While these differences may reflect plan focus or specialty to some extent, patterns remain similar when looking only at plans that provide a specialty service or serve a specialty population. For example, only two-thirds of plans that provide outpatient substance use disorder services reported contracting with methadone clinics and/or medication assistance treatment (MAT) facilities, and only 68% of plans that serve people with HIV/AIDS contract with HIV/AIDS service organizations (data not shown). It is not clear from survey results why certain facility types may not be included in plan networks; plans may exclude certain facilities or facilities may decline to contract with Medicaid MCOs.

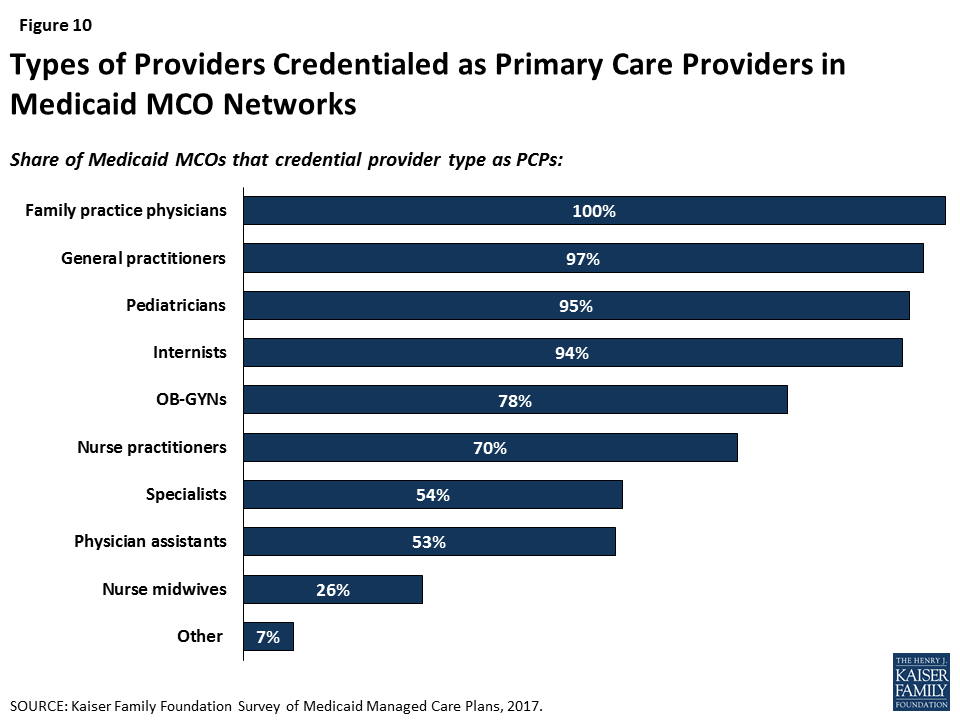

Perhaps reflecting state licensing rules, plans reported mixed use of physician extenders as primary care providers. Seven in ten plans that responded to the survey credential nurse practitioners as primary care providers, but fewer plans credential physician assistants (53%) or nurse midwives (26%) as primary care providers (Figure 10). These differences may reflect state laws about scope of practice guidelines or state Medicaid agency policy more than plan preferences. Research indicates that physician extenders may play an important role in meeting the need for primary care, particularly in areas with provider shortages. The Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) has projected a shortage of 20,400 primary care physicians in 2020, and nurse practitioners are more likely than primary care physicians to practice in underserved areas.15

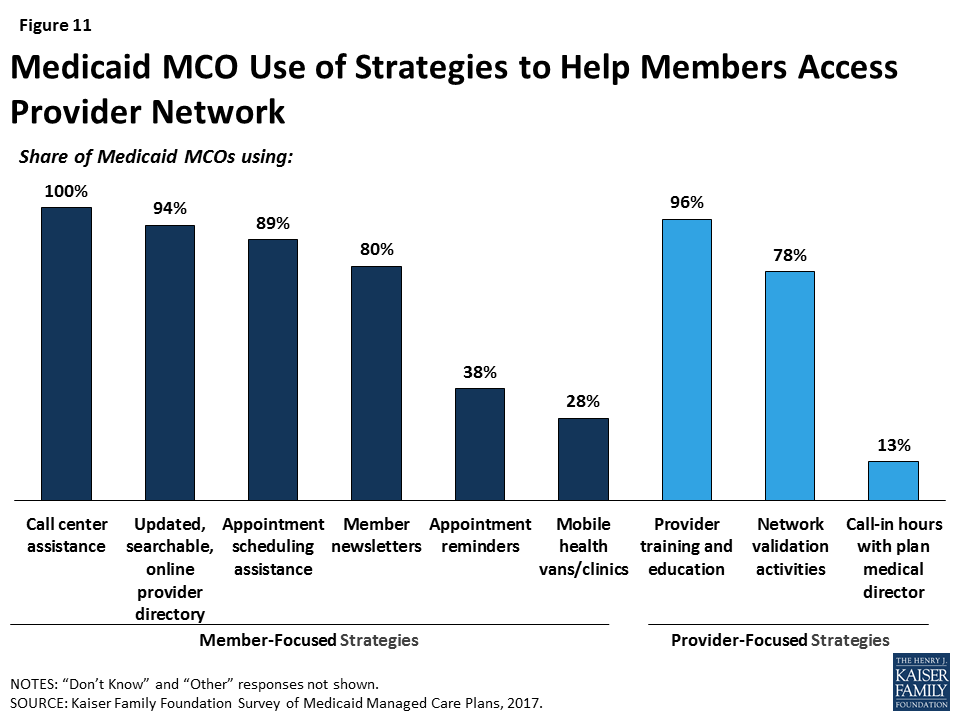

Proactive actions to identify gaps in network capacity are less common than ongoing monitoring. Currently, the most common activities plans that reported for monitoring network capacity are member/provider complaints or call center reports, feedback from regular member survey data such as CAHPS, or monitoring out-of-network visits (Table 1). Similarly, when asked about steps taken to help members access care from network providers, responding plans were more likely to report member-initiated efforts such as call center assistance (100%), searchable online directories (94%), or appointment scheduling assistance (89%) than plan-initiated strategies such as mobile vans (28%) or appointment reminders (38%) (Figure 11). Most plans also reported undertaking network validation activities and provider training.

| Table 1: Plan Activities to Monitor Network Capacity | |

| Strategy | Share of Plans Reporting |

| Member complaint and/or grievance reports | 88% |

| Provider complaints | 77% |

| CAHPS/member survey data | 72% |

| Out-of-network utilization monitoring | 67% |

| Call center reports | 56% |

| Site visits to provider offices | 53% |

| Secret shopper calls | 52% |

| Encounter data analysis to identify under-utilization | 49% |

| Emergency room utilization rate analysis | 47% |

| Inpatient admission/readmission rate analysis | 36% |

| Other | 17% |

| None | 1% |

| NOTES: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | |

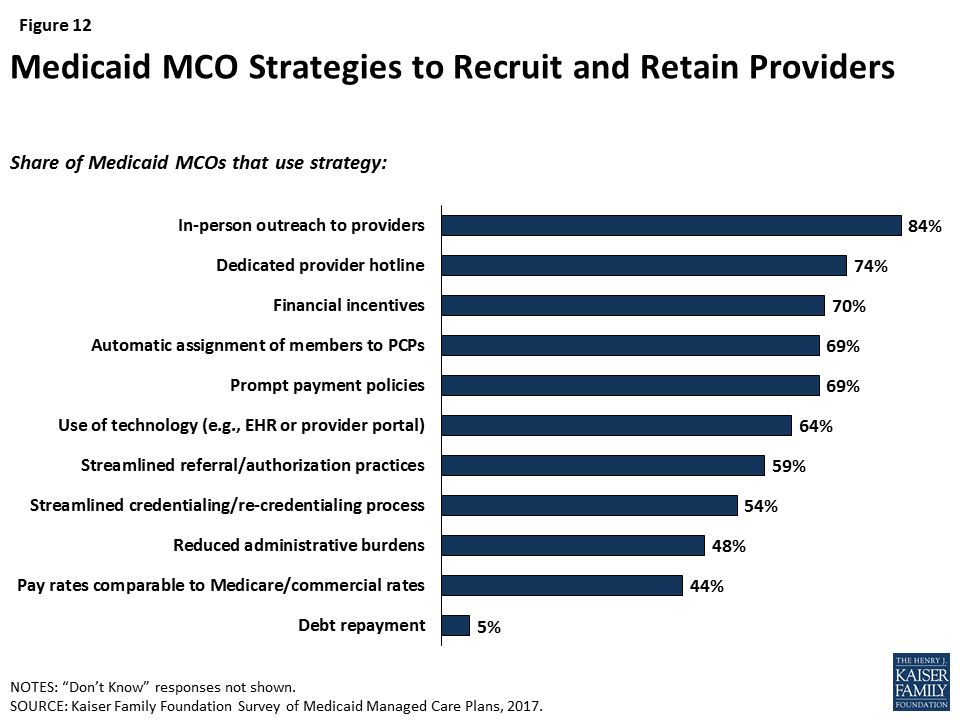

Responding plans reported a variety of strategies to address provider network issues. Among the strategies that plans use to recruit and retain providers, responding plans most frequently reported using direct outreach to providers (84%) and provider hotlines (74%), and more than half of responding plans reported using improved administrative actions (e.g., auto-assignment of enrollees, streamlined reporting or credentialing systems, or streamlined referral practices) to recruit and retain providers (Figure 12). Plans also reported using payment or financial strategies, such as sign-on bonuses (70%), prompt payment policies (69%), or payment rates comparable to Medicare or commercial insurance (44%), as incentives to recruit and retain providers. As discussed in more detail below, a majority of plans said that they either already use or plan to use enhanced payment rates for hard-to-recruit provider types, and about a third reported using or planning to use enhanced payment for providers in rural or frontier areas. Though it was not clear based on survey results whether plans are using payment levels more broadly as an incentive for provider participation, about four in ten plans reported that they directly negotiate rates with providers rather than set them based on existing Medicaid or Medicare fee schedules (data not shown).

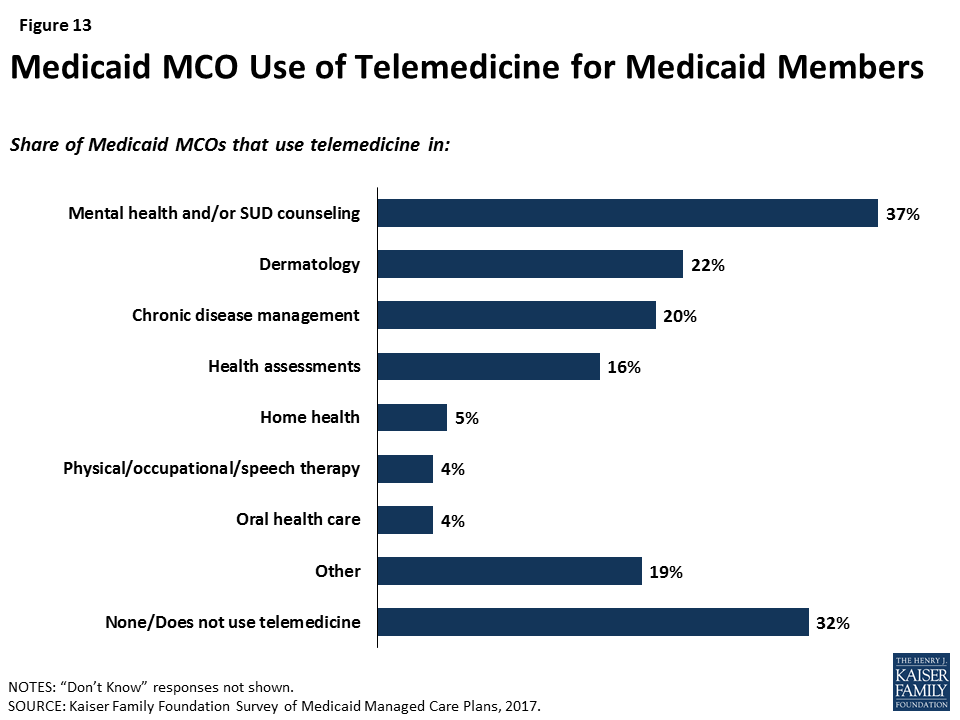

Another strategy to address network issues is the use of telemedicine. More than two-thirds (68%) of responding plans reported using telemedicine in at least one area (Figure 13), with plans most likely to use telemedicine in mental health or substance use disorder counseling. This focus could reflect particular difficulty in recruiting psychiatrists to plan networks. Under the 2016 managed care rule, CMS has noted that plans may use telemedicine to meet network adequacy requirements, though plans may be subject to state requirements related to the use of telehealth as well as state-defined (within federal parameters) network adequacy standards.16

The expansion of Medicaid under the ACA led to some concern about strains on provider capacity due to increased health coverage. Among responding plans operating in states that expanded Medicaid, more than seven in ten reported that they expanded their provider networks between January 2014 and December 2016 to serve the newly-eligible population. Plans were more likely to report adding primary care providers (59%) and specialists (56%) than mental health (48%) or substance use disorder treatment (35%) providers.17

Plans were more likely to cite provider supply shortages than low provider participation in Medicaid as a top challenge in ensuring access to care. When asked broadly about top challenges in ensuring access to care for members, provider issues were among the top issues ranked by plans (Table 2). However, plans responding to the survey were more than six times more likely to cite issues with provider supply than issues with provider participation in Medicaid, suggesting that challenges in recruitment and network adequacy are linked to broader market trends. Similarly, when asked about overall priorities, plans were much less likely to rank network-related activities (such as provider recruitment) than other issues.

| Table 2: Top Challenges and Priorities in Ensuring Access to Care | ||

| Share of Plans Reporting as One of Top Three | ||

| Challenges: | ||

| Provider supply shortages in certain specialties | 65% | |

| Provider supply shortages in certain geographic areas | 62% | |

| Capitation rate paid by the state is too low | 48% | |

| Lack of continuous eligibility for Medicaid members (i.e., “churn”) | 46% | |

| Member education about how to access care | 38% | |

| Caps on providers’ Medicaid patient panels | 11% | |

| Low physician participation in Medicaid | 10% | |

| Other | 11% | |

| Priorities: | ||

| Improve integration of physical and behavioral health | 49% | |

| Implement or expand intensive care management strategies for high-risk members | 43% | |

| Improve coordination with community-based social services organizations | 39% | |

| Improve Medicaid MCO data and information systems | 37% | |

| Implement new delivery models such as PCMHs | 26% | |

| Incentivize current network providers to accept more new Medicaid patients | 23% | |

| Contract with more mental health providers | 15% | |

| Contract with more primary care providers | 14% | |

| Contract with more specialists | 14% | |

| Expand use of non-physician providers | 13% | |

| Improve member education | 6% | |

| Contract with more substance use disorder providers | 5% | |

| Other | 10% | |

| NOTES: Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | ||

Report: Member Experience And Access To Care

One of the most direct ways that plans may facilitate access to care is to engage members directly in their care and help them navigate the health care system. For example, plans may tailor service delivery to meet members’ specific needs, link them to providers, and help members develop ongoing provider relationships. Plans’ direct contact with members builds on efforts to work with providers and include many strategies targeted to the needs of the population with Medicaid coverage.

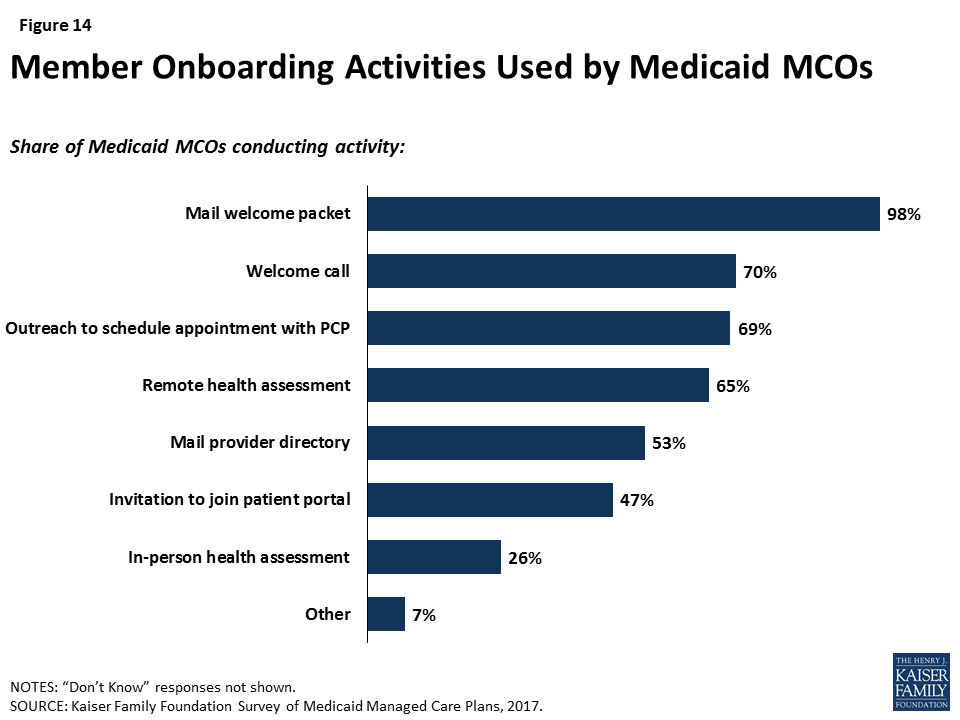

Most plans reported actively conducting health assessments or data analytics to engage members, particularly high-need members, in care. As part of onboarding (enrolling members in the plan), most responding plans (77%) reported conducting conduct a health assessment18 either in person (26%) or remotely (65%), and over two-thirds of plans (69%) suggested that members make an appointment with their primary care provider (Figure 14). In addition, all survey respondents indicated that they take some action to identify high-need or high-risk enrollees, such as medical record review or data analytics (90%) or health assessments (89%). As part of either onboarding or screening for high-need enrollees, more than half of plans (59%) reported conducting an in-person health assessment at some point during the initial enrollment period.

Reflecting state and federal eligibility rules, plans reported variation in churn or enrollment duration among different enrollment groups, which may pose a challenge to care continuity. Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women ends 60 days postpartum, and plans reported the shortest tenure of plan enrollment among pregnant women. Among responding plans that enroll pregnant women, more than a third said that pregnant women are typically enrolled for less than 12 months (Figure 15) (and excluding plans who responded “Don’t Know,” more than half said that average tenure for pregnant women is less than a year). In contrast, Medicaid eligibility for people with disabilities is often automatically linked to receipt of Supplemental Security Income, and nearly half of plans that enroll people with disabilities reported that they are typically enrolled for more than two years (again, only among plans that did not respond “Don’t Know,” this figure rises to 70%). Most plans reported that children typically remain enrolled for more than a year, but plans in states that have 12-month continuous eligibility for children were more likely to report longer average plan tenure for children than plans in states without 12-month continuous eligibility (59% of plans in states with 12-month continuous eligibility reported over 1 year of average enrollment for children vs. 40% of plans in states without 12-month continuous eligibility for children). Plans that participate in both Medicaid and Marketplaces reported moderate (31%) or insignificant (31%) churn between coverage sources (versus significant (3%) or no (6%) switching), but some plans do not track enrollment changes across their Medicaid and Marketplace products (20%) or were unable to say to what extent members moved (9%).

Health plans are broadening their scope beyond delivery of medical services to encourage healthy behaviors or address social determinants of health. Almost all plans responding to the survey reported offering incentives for “healthy behaviors,” with the most common incentives being those for well-child care, prenatal visits, and postpartum care (Table 3). Fewer plans — though still notable shares — reported offering incentives for chronic disease control (diabetes (57%), cholesterol (25%), and blood pressure (36%)). By far, the most common incentive is a voucher or gift card, with 91% of plans offering this type of incentive.

| Table 3: Plan Activities in Healthy Behavior Promotion | ||

| Share of Plans Offering | ||

| Well-child care (e.g., exams, immunizations) | 76% | |

| Prenatal visits | 73% | |

| Timely postpartum care | 73% | |

| Diabetes management | 57% | |

| Smoking cessation | 48% | |

| Adult primary care visits | 41% | |

| Weight management | 39% | |

| Blood pressure control | 36% | |

| Cholesterol control | 25% | |

| Other | 17% | |

| Do not offer incentives to encourage healthy behaviors | 11% | |

| NOTES: Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | ||

In addition, almost all plans (91%) reported activities to address social determinants of health, with housing and nutrition/food security reported as top targets and fewer plans undertaking activities related to education or employment (Table 4). The scope and depth of plan activities in these areas are not clear from the survey responses. Federal Medicaid reimbursement rules prohibit expenditures for most non-medical services, but plans may use administrative savings or state funds to provide these services.19 ,20 Nearly all plans reported working with community-based organizations to link members to social services (93%) or assessing members’ social needs (91%), and most plans also reported maintaining community or social service resource databases (81%). Again, the scope of these activities is not clear from survey responses. While some MCOs may have formal partnerships with community-based organizations, others may just make referrals to these organizations. Additionally, some of these activities are dictated by state contracts with plans: about half of MCO states required in FY 2017 (19 states) or planned to require in FY 2018 (2 states) that Medicaid MCOs screen beneficiaries for social needs and provide referrals to other services.21

| Table 4: Plan Activities Related to Social Determinants of Health | |

| Share of Plans that Addressed Social Area in Past 12 Months | |

| Housing | 77% |

| Nutrition/Food Security | 73% |

| Education | 51% |

| Employment | 31% |

| Other | 5% |

| None | 9% |

| Share of Plans Using Strategy in Past 12 Months | |

| Work with community-based organizations to link members with needed social services | 93% |

| Assess member needs | 91% |

| Maintain database of community/social service resources | 81% |

| Use community health workers | 67% |

| Use interdisciplinary community care teams | 66% |

| Offer social services such as WIC application assistance and employment counseling referrals | 52% |

| Assist justice-involved individuals with community reintegration | 20% |

| Other | 4% |

| None | 0% |

| NOTES: Responses of “Don’t Know” are not shown, and missing answers are not included in calculations.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | |

Report: Provider Payment And Delivery System Reform

There is great interest among public and private payers alike in restructuring delivery systems to be more integrated and patient-centered, along with developing concomitant initiatives to adjust provider payment models to incentivize quality. Payment reforms often include “alternative payment models” (APMs). APMs lie along on a continuum, ranging from arrangements that involve limited or no provider financial risk (e.g., pay-for-performance (P4P) models) to arrangements that place providers at more financial risk (e.g., shared savings/risk arrangements or global capitation payments). APMs often go hand-in-hand with delivery system reform initiatives, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), ACA Health Homes, and physical and behavioral health integration activities. (See Appendix Box 1 for definitions of common payment and delivery system reform models.) States may encourage or require Medicaid MCOs to implement specific delivery system and/or payment reform initiatives. Alternatively, MCOs themselves may design and implement delivery system and payment reform initiatives. As of FY 2017, more than half of the 39 states that contract with comprehensive risk-based MCOs require (13 states) or plan to require in FY 2018 (9 states) that MCOs make a target percentage of provider payments through APMs.22 Fewer states require (8 states) or plan to require (4 states) that Medicaid MCOs adopt specific APMs (e.g., episodes of care, shared savings/shared risk etc.).23

Almost all plan respondents (93%) still make fee-for-service (FFS) payments to at least some providers, but most are paying at least some primary care providers (PCPs) through methods other than FFS (such as salary, prospective payment, or capitation), and many also pay at least some specialists through non-FFS methods. Within Medicaid, states pay Medicaid MCOs per-member-per-month capitation payments for Medicaid enrollees; however, plans generally have wide latitude to determine how to pay their contracted providers. Medicaid MCOs may pay the providers in their networks on a FFS basis, capitation basis, or on other terms. Sixty-three percent of plans reported using a method other than FFS to pay at least some PCPs, while only 44% of plans reported using a method other than FFS to pay at least some specialists.

Plans are using provider payment as a policy lever to facilitate access to care. Two-thirds of plans in the survey reported that they currently use payment incentives related to access to care (Figure 16), and about an equal share plan to implement new or additional access-related payment incentives in the upcoming year. About a third of plans reported using payment incentives for providers to have same-day or after-hours appointments. A majority of plans (67%) said that they either already use (62%) or plan to use (42%) enhanced payment rates for hard-to-recruit provider types, and 34% reported using (33%) or planning to use (21%) enhanced payment for providers in rural or frontier areas.

While most plans have continued paying providers through the traditional FFS method, nearly all plans have also adopted new systems of payment by using APMs to reward providers for meeting quality and, in some cases, cost-based benchmarks. These approaches are not mutually exclusive, as APMs can build on FFS payment, and multiple APMs can be utilized simultaneously. Ninety-eight percent of plans in the survey reported using at least one APM for at least some providers (Figure 17). The vast majority of plans (93%) reported using incentives and/or bonus payments tied to specific performance measures (so-called “pay-for-performance”), which involve limited or no provider financial risk. Fewer plans reported using APMs that typically transfer more risk to providers, such as bundled or episode-based payments (38%) and shared savings and risk arrangements (44%), which may be more resource-intensive to design and implement.

Although nearly all plans report using at least one APM, the overall share of payments made to providers through APMs is modest, especially for hospital payment (Figure 18). Plans may pay any type of provider through an APM. When asked about use of APMs among PCPs and hospitals, responding plans reported that they were less likely to use APMs for hospitals than for PCPs. Nearly a third of plans (32%) said that they make no payments through APMs to hospitals, while few plans (4%) reported making no APM payments to PCPs.24 While a similar share of plans reported making between 1% and 15% of payments through APMs to PCPs (33%) and hospitals (36%), more than a third of plans (34%) reported making more than 30% of payments to PCPs through APMs, while just 10% of plans reported making more than 30% of payments to hospitals through APMs.

Plans also reported interest in delivery system models that build on new payment models, such as ACOs and PCMHs. Both ACOs and PCMHs aim to create patient-centered and coordinated care delivery systems (see Box 1 for definitions) by increasing provider responsibility for quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes. Twenty-eight percent of plans in the survey reported contracting with an ACO, and roughly one-third of remaining plans are considering contracting with ACOs in the future.25 Not surprisingly, plans contracting with ACOs are more likely than plans overall (89% versus 73%) to be using shared savings and/or shared savings and risk arrangements, which are a core feature of ACOs, and are more likely to make a larger share of payments to hospitals through APMs (41% making at least 15% of hospital payments through APMs versus 19% of all plans, data not shown). Additionally, about a third of plans that do not contract with ACOs reported using shared savings and/or shared risk arrangements. These plans may be using shared savings or shared risk payment models with other provider types and/or other delivery system reform efforts, including PCMH models. Overall, 69% of plans reported offering their beneficiaries enrollment in PCMHs.26 It is unclear how many members are covered by these new payment and delivery system arrangements. For example, while a majority of plans offer PCMH to their members, only 26% of plan respondents reported that at least half of their Medicaid members are served through such arrangements.

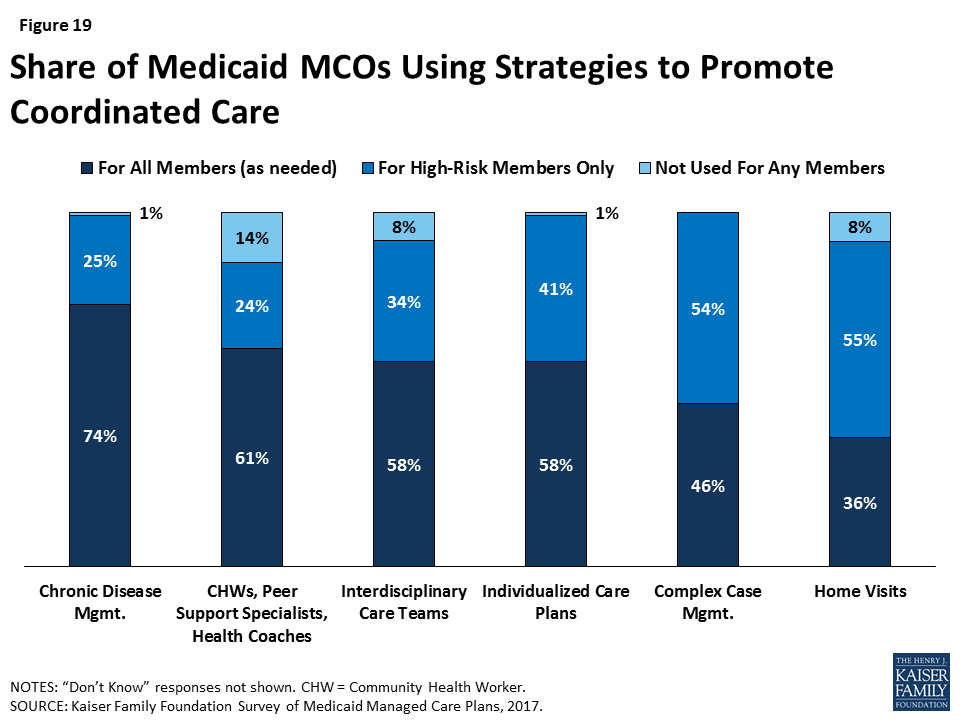

In addition to contracting with ACOs and PCMHs, plans are using a variety of other strategies to coordinate care for beneficiaries (Figure 19). Plans reported wide usage of these strategies, with most plans using chronic disease management, peer support or health coaches, interdisciplinary care teams, or individualized care plans for all members on an as-needed basis. Other strategies, such as complex case management and home visits, are more likely to be offered to high-risk members only (54% and 55% of plans, respectively). In their efforts to target high-risk members, plans also offer population-specific services (data not shown). For example, more than 80% of plans reported offering case management or care coordination to homeless individuals, and approximately three-quarters of respondents reported conducting outreach to members or potential members who are homeless to assist with health care access.

Plans are also active in promoting the integration of physical and behavioral health (Table 5). Integration of physical and behavioral health ranks as the top priority for health plans in ensuring access to care for members, with nearly half (49%) of respondents ranking it as a top three priority (Table 2). Nearly all plans (94%) reported at least one strategy to promote provider-level physical and behavioral health integration. Plans are currently more likely to pursue such integration through organizational/administrative methods, such as contracting with health systems with co-located providers (77%), offering provider training/education (64%), or facilitating medical record sharing (55%), than through payment strategies such as offering payment incentives for colocation of physical and behavioral health providers (28%) or for PCPs to screen or refer for behavioral health needs (26%). When asked about barriers to integration, no single issue was most commonly cited by plans; rather, plans gave a variety of answers for the greatest challenge to integration, indicating that such efforts may be unique to the specific circumstances and location of a plan.

| Table 5: Plan Activities to Integrate Physical and Behavioral Health Care | |

| Share of Plans Reporting | |

| Any strategy | 94% |

| Organizational/Administrative Strategies | |

| Establish care management/coordination teams with both physical and behavioral health providers | 85% |

| Contract with practices or health systems that provide co-located or integrated care | 77% |

| Offer provider training/education | 64% |

| Facilitate sharing of medical records | 55% |

| Operate or contract with Medicaid health homes for individuals with SMI and/or SUD | 46% |

| Other | 8% |

| None | 2% |

| Payment Strategies | |

| Payment incentives/financial support for co-location of physical and behavioral health providers | 28% |

| Payment incentives for PCPs to screen/refer for behavioral health needs | 26% |

| Payment incentives for behavioral health providers to screen/refer for chronic health care needs | 16% |

| Other | 8% |

| None | 45% |

| NOTES: SMI = Serious Mental Illness. SUD = Substance Use Disorder. Responses of “Don’t Know” or missing are not shown.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | |

Report: Current Medicaid Policy Debate, Mcos, And Access To Care

There have been significant federal Medicaid policy developments in recent years that have implications for Medicaid MCOs, including the introduction of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) effectively optional Medicaid expansion in 2014 and the finalization of federal regulations governing the operation of Medicaid managed care in 2016.27 Additionally, since the Trump Administration took office in 2017, there have been several legislative attempts to repeal and replace the ACA and cap federal Medicaid financing. The Trump Administration is also using administrative action, including the use of Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers,28 to make changes to the Medicaid program and longstanding Medicaid policy. These policy actions may affect the populations served by MCOs, plan operations and finances, or funding levels available for payments to MCOs.

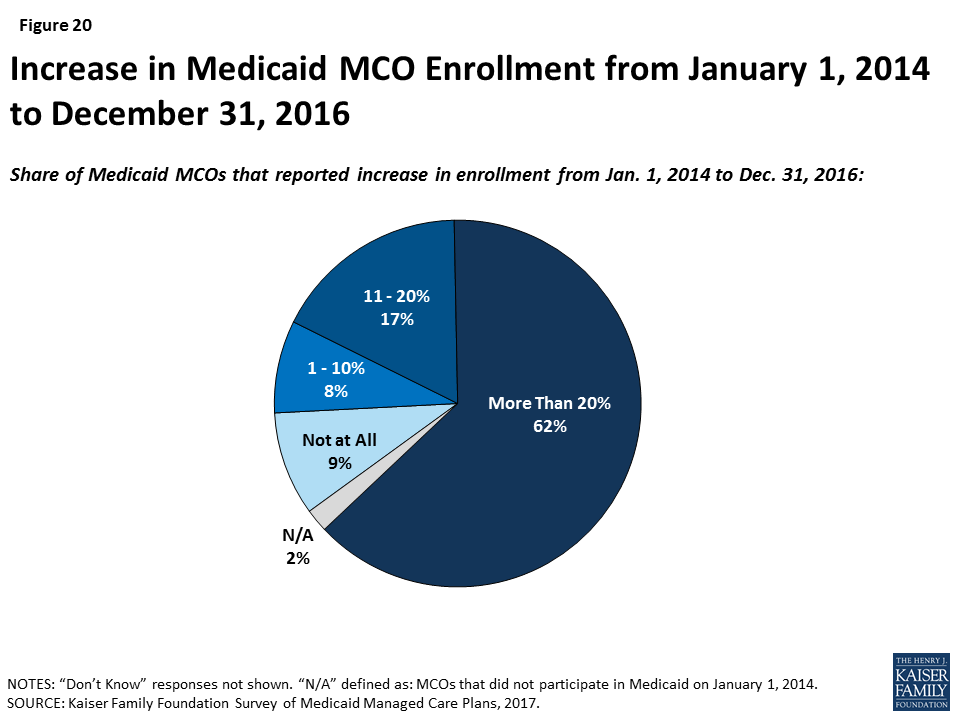

The ACA Medicaid expansion has had many positive effects on Medicaid managed care plans but does not appear to be a main driver in their decision to participate in the Medicaid market. Most Medicaid expansion states contract with MCOs to serve a large share of Medicaid beneficiaries, including those newly eligible under the ACA.29 Plans reported substantial increases in enrollment under the ACA. Across all states (i.e., expansion and non-expansion states), 62% of responding plans indicated their Medicaid MCO’s enrollment increased by more than 20% between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016 (Figure 20). Nearly two-thirds of plans in expansion states said that the expansion has had a positive effect on their financial performance. Legislative proposals introduced in 2017, as well as provisions in President Trump’s proposed FY2019 budget, included options to repeal and potentially replace the ACA, which could have significant implications for the number of lives covered by MCOs as well as the case mix of Medicaid beneficiaries served by MCOs. However, fewer than 10% of plans said that they are very or somewhat likely to rethink their participation in Medicaid if the ACA expansion were repealed, perhaps reflecting responding plans’ long tenure in the Medicaid market and participation even before the ACA was passed.

“If state Medicaid programs are subject to spending limits, either aggregate or per capita, that do not take into account actual trend in health care inflation, then it seems likely that this will have – at least – a chilling effect on provider and plan rates. This would constrain states, and by extension plans, to the point that services and enrollment might have to be curtailed.”

–“We anticipate benefit reductions would be required under federal block grants or per capita caps to states. Efforts to address the social determinants of health would also be impacted if not stopped altogether.”

Plans indicate a host of concerns related to policies debated by Congress that would restructure federal Medicaid financing as block grants or per capita caps. Legislative proposals introduced in 2017 called for fundamental changes in Medicaid financing that could limit federal financing for Medicaid through a block grant or a per capita cap.30 Plans responded to an open-ended question that asked what the most significant implications would be for MCOs if federal financing were restructured as a federal block grant or per capita cap to states. Plans were nearly universally negative about these proposals. Although several plans indicated that their response would depend on the construction of the model (including base year calculation, inflationary trend rate, etc.), generally, many MCOs indicated that they anticipate that states will not be able to make up for federal funding losses under a block grant or a per capita cap structure. As one respondent stated, “Loss of funding would negatively impact [our] ability to cover members and provide necessary benefits.” Many plans said that they expect these proposals to lead to MCO funding cuts/lower capitation rates, and MCOs anticipate that states will request more flexibility from CMS to cut eligibility levels and benefits. A few plans also specifically indicated that a block grant or per capita cap may put them at risk financially, may lead to negative margins, may compromise the actuarial soundness of capitation rates, and ultimately, may lead some MCOs to leave the market. Responses also described a multitude of anticipated beneficiary impacts. Plans enumerating anticipated beneficiary consequences most frequently cited eligibility changes that may lead to decreased enrollment, decreased or reduced benefits, and provider rate cuts that may lead to reduced provider participation/access.

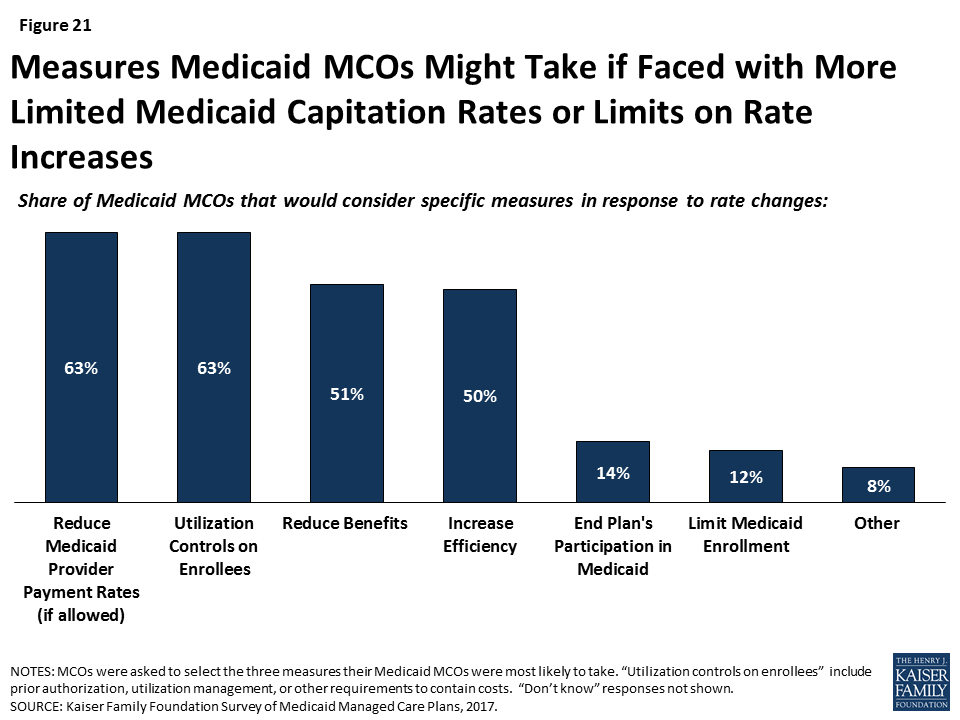

The survey also asked plans what measures they might take if they were faced with more limited Medicaid capitation rates. Many plans indicated that they would likely pass these rate cuts on through reduced payments to providers or utilization controls on enrollees (i.e., increase prior authorization, utilization management, or other requirements) (Figure 21). Examples of “other” measures specified by plans include reducing community involvement/investments, restricting provider networks, reducing member “extras,” and reducing marketing activities.

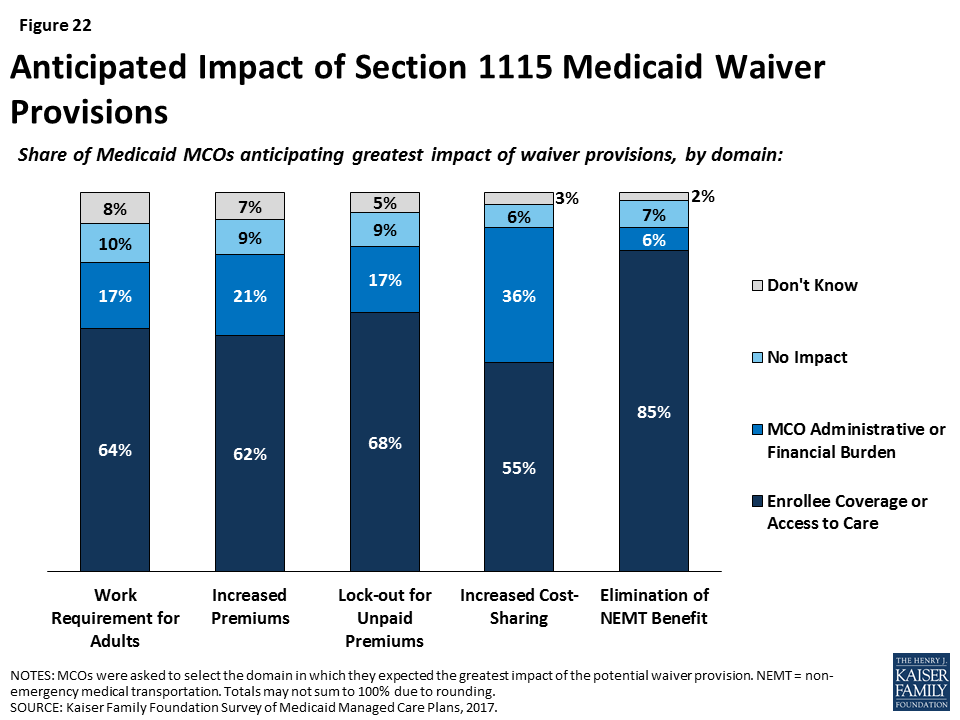

For most changes being discussed under Section 1115 waiver proposals, plans reported concern over potential implications for enrollee coverage/access. Section 1115 authority permits the Secretary of Health and Human Services to allow states to use federal Medicaid and CHIP funds in ways not otherwise allowed under the federal rules, as long as the Secretary determines that the initiative is an “experimental, pilot, or demonstration project” that “is likely to assist in promoting the objectives of the program.” Shortly after taking office in 2017, the current Administration signaled a willingness to expand the use of Section 1115 Medicaid waivers or approve waivers with provisions never approved before, including conditioning Medicaid eligibility on meeting work requirements.31 Plans were asked whether waiver provisions being considered by states, including work requirements, increased premiums, lock-outs for unpaid premiums, increased cost-sharing, or elimination of non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT), would have the greatest impact on plans or enrollees, or whether plans anticipate that these provisions would result in no impact. Fewer than 10% of plans said that they anticipate that waiver provisions will have no impact (Figure 22). Rather, most plans stated that each of the waiver provisions would have the greatest impact on enrollees through coverage or access to care, versus on plans through administrative burden or financial performance. Although relatively few plans reported that provisions would have the greatest impact on plans (versus enrollees), more than one-third of plans indicated that increasing cost-sharing would have the greatest impact on plans (administrative burden or financial performance).

A majority of plans reported needing at least some additional guidance to implement many of the 2016 Medicaid managed care final rule provisions. In May 2016, CMS issued a final rule on managed care in Medicaid and CHIP. The rule represents a major revision and modernization of federal regulations in this area.32 The general effective date of the final rule was July 5, 2016, although individual provisions of the rule take effect at different times, mostly over three years. The survey asked plans to identify the top three areas of the managed care rule that would be the most resource-intensive for them to implement (Table 6). The rule’s new quality rating system was the area that plans most commonly cited as the most and second-most resource-intensive for them to implement. Network adequacy and actuarial soundness/rate-setting were the next most common first choices, while risk adjustment and encounter data reporting were the next most common second choices. Under the new Administration, CMS announced in June 2017 that they are doing a thorough review of the managed care regulations and may use the rulemaking process33 to make modifications to the final rule. Additionally, CMS has indicated that they may offer leniency to states in meeting compliance deadlines for certain managed care regulations. 34 Plans were also asked if the change in Administration has affected their implementation timeline. Nearly three-quarters of plans reported that the change in Administration has not caused them to put a hold on activities to implement provisions of the Medicaid managed care rule.

| Table 6: Share of Plans Ranking MCO Rule Area As One of Top Three Most Resource-Intensive to Implement | |||

| Rule Area | First | Second | Third |

| Quality rating system | 22% | 26% | 17% |

| Network adequacy | 19% | 12% | 17% |

| Risk adjustment | 7% | 24% | 12% |

| Encounter data reporting | 11% | 14% | 17% |

| Mental health parity | 6% | 11% | 19% |

| Actuarial soundness/rate-setting | 18% | 6% | 7% |

| Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) | 3% | 6% | 7% |

| Other | 2% | 1% | 2% |

| Don’t Know | 11% | 1% | 2% |

| SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans, 2017. | |||

Report: Discussion

Managed care plans are on the front lines of efforts to facilitate access to care for Medicaid enrollees. In this role, plans both work directly with providers and enrollees and also undertake efforts to facilitate connections between providers and enrollees. While many of these activities stem from contract provisions between states and plans, others are plan-initiated. For example, less than half of states using comprehensive managed care require plans to conduct strategies to address social determinants of health, and several states report35 that their MCOs provide enhanced services beyond those contractually required.

Survey results indicate that plans serving Medicaid enrollees are typically focused on serving the low-income population and have extensive experience in this market. This focus and experience may explain high rates of plan activity to address non-medical (social) barriers to health common among the Medicaid population, such as inadequate housing and food insecurity. In addition, many plans are serving high-risk or high-need populations and have developed screening or other programs to identify and engage these groups.

Many plan efforts to address issues in member access — whether they are focused on provider network adequacy, access outcomes, or efforts to integrate care — use provider payment as an incentive. Payment can be a powerful tool and, in most cases, is at the discretion of plans. Survey findings show that plans are developing APMs to provide incentives for providers to modify practices to provide high-quality, easily-accessed, and low-cost care. Though APMs with low provider risk (such as pay-for-performance) are most common, plans may be turning their focus to investment in total cost of care/shared savings (and risk) models such as ACOs or global payment models. Take-up of these models may vary by provider market characteristics and provider readiness to make organizational changes. In addition, there may be limits to plans’ ability to create payment incentives within the capitation payments that they receive from states. Currently, evidence of the effects of ACOs, episode-based payments, and global budget models on spending and quality of care is limited. States and MCOs will monitor current and future evaluations of the effectiveness of these models, especially for the Medicaid population specifically, as Medicaid beneficiaries tend to have complex medical and social needs that may differ from other payers’ patient populations. Many responding plans also reported using non-payment methods, such as incentives geared directly to enrollees (through healthy behavior programs) or steps to ease administrative burden on providers, in their efforts to facilitate access to care.

Survey results also provide a window into the current state of service integration and the shift to patient-centered care. Plans reported relatively high rates of carving in long-term services and supports (LTSS) and behavioral health services to their contracts, which aligns with other survey results indicating plans’ efforts to pursue co-located behavioral and physical health care providers or to establish integrated care coordination teams. However, despite a majority of plans reporting that their state contract included a broad range of services such as prescription drugs, NEMT, and substance use disorder services, many plans reported subcontracting for these services, which may run counter to integration goals.

Several survey findings point to external forces that pose a challenge to plans’ ability to facilitate access. Most notably, plans reported high rates of difficulty in recruitment for some specialties and listed provider supply as a leading challenge. Provider supply (especially among psychiatrists36 ) is a challenge for all payers, including private insurers and Medicare. While payment is one tool to address provider network issues, it can be limited if the market simply does not include sufficient providers. Regulation37 of network adequacy reflect this challenge and may allow states to exempt certain specialties from network adequacy requirements;38 however, enrollee need for these services remains. Many plans are turning to telehealth as an option, although plans are bound by state rules regarding telemedicine. Another external force affecting plans is Medicaid eligibility, as enrollee tenure in plans aligns with Medicaid eligibility rules. Longer plan enrollment may facilitate successful patient-provider relationships and allow for plans to reap the benefits of initiatives whose effects are not immediate. However, recently proposed policies, such as waiver provisions that allow disenrollment or lock-out periods for failure to comply with new rules, could exacerbate enrollee churn. A final area of external forces affecting plans’ ability to ensure access is proposed policy change to Medicaid financing or use of Medicaid waivers. Though plans are likely to remain in the Medicaid market even if the ACA is repealed, plans expressed high rates of concern about the implications of proposed changes, such as waivers or per capita caps, for enrollee access to care. Most plans reported that they would consider policy changes that could impede access (e.g., payment cuts or utilization control) if faced with lower capitation payments under Medicaid reform.

The 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations39 include new federal requirements for how states operate their Medicaid managed care programs. For example, the managed care regulations strengthen network adequacy requirements, such as time and distance standards, and clarify states’ authority to require MCOs to implement value-based purchasing or participate in delivery system reforms. The managed care final rule also broadens federal standards for care coordination to include coordination between settings, with services provided outside the plan, and with community and social support providers. In light of the surveyed plans’ reported difficulty recruiting certain providers, such as specialists and subspecialists, the 2016 regulations could increase pressure on plans to focus energy in this area. Additional CMS resources that guide plans on compliance with the regulations also place considerable emphasis on provider networks and access standards.40 Plans are moving ahead with actions to come into compliance with the regulations, despite federal signals that they will revisit the regulations.

While MCOs in this survey have long experience serving Medicaid enrollees, they face an uncertain future as they navigate how to move forward with new initiatives in the context of potential budget cuts, waivers, and changes to federal regulations. This survey was in the field between April and September 2017, when the fate of specific legislative efforts to repeal and replace the ACA and to restructure federal Medicaid financing was unknown. As 2018 begins, there is a focus on administrative actions using Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waivers, state actions on Medicaid expansion, and other federal health care priorities. Medicaid in 2018 is also likely to continue to be part of both federal and state budget deliberations. Key findings from our survey illustrate that plans are active in many areas, including pursuing strategies to improve access to care, implementing payment and delivery system reform models, developing linkages to non-medical social services, and coming into compliance with the Medicaid managed care rule. Plans are moving forward in these areas despite a broader environment of uncertainty, driven by federal proposals to restructure Medicaid financing and repeal the ACA as well as administrative actions such as the approval of the first work requirements in Medicaid. Findings from our survey of Medicaid managed care plans can provide important context for ongoing Medicaid policy discussions and debates involving legislative and administrative action, as plans represent an important stakeholder in the Medicaid program.

Appendix

Definitions of Payment and Delivery System Reform Models

PAYMENT MODELS

Fee-for-Service (FFS): In a FFS system, payers establish the fee levels for covered services and pay participating providers directly for each service they deliver. Providers do not bear any financial risk.

Pay-for-Performance (P4P): P4P is a health care payment model that rewards providers financially for achieving or exceeding specified quality benchmarks or other goals. P4P payments may be made based on performance on structure, process, and/or outcome measures, with providers evaluated against benchmarks or by comparison with other providers.

Shared Savings Arrangements: Under shared savings arrangements, organizations or ACOs have an opportunity to share in any net savings that accrue to a payer for a defined panel of patients over a specified time period (usually 12 months). Actual costs for the patient panel are compared to a pre-established benchmark that is determined using historical utilization and/or cost data for the patient panel or a similar population. To be eligible for savings, provider organizations/ACOs must meet performance/quality requirements while also reducing costs.

Shared Risk Arrangements: Entities that enter into shared savings arrangements with payers may also agree to share in losses. Risk-sharing is often added to shared savings arrangements after some experience has been accumulated. Under a shared risk arrangement, if actual costs for the defined patient population exceed the benchmark, the provider group/entity is accountable for a portion of the excess costs and must return funds to the payer.

Episode of Care Payment: Episode of care payments are single, pre-established amounts paid to providers for the set of services involved in treating a patient’s health event, such as a knee replacement, or a particular health condition, such as asthma, over a specified period of time. Episodes have a defined beginning and end and usually involve payment for multiple services and providers. Episode of care payments can be prospective or retrospective.

Global Payments/Bundling: Global bundling involves a single, pre-set payment for a wide range of services delivered to an individual over a defined period of time, usually one year. Global payment amounts are risk-adjusted based on the patient’s health and other characteristics that may affect the services needed, such as age or gender. In addition, global payment models incorporate outcome or quality measures to safeguard against under-service and reward high performance.

DELIVERY SYSTEM MODELS

Accountable Care Organization (ACO): There is currently no uniform federal definition of an ACO, and the concept continues to evolve. Generally, an ACO is a group of health care providers that agrees to share responsibility for the health care delivery and outcomes for a defined population. The organizational structure of ACOs varies, but, in concept, ACOs generally include primary and specialty care providers and at least one hospital. Providers in an ACO are expected to coordinate care for their shared patients to enhance quality and efficiency, and the ACO as an entity is accountable for that care, specifically for the quality and total cost of care.

Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH): Under a PCMH model, a physician-led, multi-disciplinary care team holistically manages the patient’s ongoing care, including recommended preventive services, care for chronic conditions, and access to social services and supports. Generally, providers or provider organizations that operate as a PCMH seek recognition from organizations like the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA).

Health Home (HH): Section 2703 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicaid health home (HH) program. The Medicaid HH model builds on the patient-centered medical home concept. Targeted to individuals with multiple chronic conditions, including serious mental illness, HHs are designed to be person-centered systems of care that facilitate access to and coordination of the full array of primary and acute physical health services, behavioral health care, long-term services and supports, and social service supports. HHs establish care plans for Medicaid beneficiaries, and coordinate and integrate clinical and non-clinical services. HH providers are required to report quality measures established by CMS.

Physical and Behavioral Health Integration: There are a continuum of activities that facilitate the integration of physical and behavioral health care, including information sharing between providers to co-location of providers.

Methods

The Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) was fielded from April to September 2017 to investigate how MCOs provide and monitor access to care for Medicaid enrollees. In particular, the survey aimed to capture information about MCO policies, procedures, and strategies for ensuring optimal access to care, as well as MCOs’ top challenges and priorities in regards to access. The survey also collected information on key characteristics of MCOs, such as the populations enrolled and the delivery systems and payment models used, and the impact of current policy developments on MCO operations. The Kaiser Family Foundation contracted with NORC at the University of Chicago to develop and field the web-based survey.

Survey Sample

The target population included all comprehensive Medicaid MCOs in the 39 U.S. states (including the District of Columbia) that use comprehensive managed care for any Medicaid enrollees. Eligible plans included any plan that had a 2016 Medicaid MCO contract (as several survey questions referred to plan operations in 2016) and was active during the data collection period in 2017 (as some survey questions referred to future/current plan operations). The final sample frame comprised 280 MCOs.41 MCO executives, such as Presidents, Chief Executive Officers (CEOs), Chief Operating Officers (COOs), Directors of State Programs, Directors of Medicaid Programs, Directors of Marketing and/or Communications, and Directors of Government Regulations or Government Affairs, were asked to complete the survey on behalf of their MCO. Each MCO was provided with a unique survey link, and multiple individuals within each MCO could collaborate to complete the survey.

Field Period

Data collection began on April 17, 2017 and concluded on September 21, 2017. The survey was distributed by email to executives at each MCO. Outreach to plan contacts occurred multiple times throughout the field period to encourage participation. The survey was offered in English only. A PDF of the survey instrument was provided to all respondents along with a link to the web-based survey.

Survey Response Rate and Sample Representation

The response rate was calculated using American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) standards for establishment surveys, which is the number of completes divided by the number of eligible reporting units (which in turn is the sum of complete and partial interviews, refusals, non-contacts, and other sample units). Out-of-scope cases are excluded as they are incapable of participating.

In data processing, NORC identified three cases that had complete survey data or were missing only data for the first section (respondent contact information) but did not formally complete the survey by hitting “Save and Submit.” These cases were re-coded as completes at the end of data collection. All other cases with questionnaire responses were classified as Partial Completes. Cases that had timestamp data indicating that they reviewed the web survey, but did not respond to any survey questions, were classified as Non Response.

The final plan participation calculations are as follows:

| Table A1: Sample Definition and Plan Participation Rate | |

| Invited MCOs | 280 |

| Eligible Plans Not Inviteda | 2 |

| Invited Plans Excludedb | 5 |

| Eligible Plans | 277 |

| Complete Surveys | 95 |

| Survey Response Rate | 34.3% |

| Partially Complete Surveysc | 3 |

| a Two MCOs were identified post-data collection as having been eligible for inclusion in the survey. These two plans were not included in the final sample frame nor were they invited to participate during the data collection period; however, they are included in the final data file and response rate calculations. b Five plans were dropped from the sample frame as they were found to be ineligible after the initial email was sent. These plans were excluded due to being purchased by another plan already on the sample frame or ceasing to operate as a Medicaid MCO in the state. c These plans completed a majority of survey sections and were included in the analysis but not the survey response rate. | |

Reported results are not weighted. In reporting data, we further included data from three partial complete plans that completed the majority of the survey (partial completes that did not complete a majority of the survey were dropped from the analysis). Comparison of plans represented in data reporting to the universe of eligible plans (Table A2) indicates that included plans represent 31 of 39 states and 38% of total comprehensive Medicaid managed care enrollment.42 Reporting plans were slightly more likely than the universe of plans to be non-profit and to operate in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA. Compared to the universe of eligible plans, reporting plans were similar in average Medicaid enrollment, geographic distribution, and state Medicaid MCO penetration. When appropriate, we interpret findings in light of the higher likelihood of responding plans being non-profit plans in Medicaid expansion states.

| Table A2: Comparison on Plans in Survey and Universe of Plans | ||

| All MMC Plans | Plans in Survey | |

| Number of states | 39 | 31 |

| Total MMC enrollmenta | 48 million | 18 million |

| Profit Statusb Non-Profit For-Profit | 48% 47% | 64% 34% |

| In Medicaid expansion state | 72% | 68% |

| Average plan enrollmenta | 185,130 | 172,908 |

| Geographic Region Northeast South Midwest West | 19% 28% 24% 30% | 18% 31% 25% 26% |

| At least 80% of state Medicaid population enrolled in Medicaid MCO | 57% | 57% |

| NOTES a Based on plans for which enrollment is known. Approximately 14% of all plans have unknown enrollment. See: The Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts. Medicaid MCO Enrollment. Data Source: State Medicaid managed care enrollment reports for the timeframe indicated unless otherwise noted; available at: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/medicaid-enrollment-by-mco/.b Approximately 5% of all plans profit status could not be determined based on online searches. | ||

Endnotes

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book (Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, December 2017), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-29.-Percentage-of-Medicaid-Enrollees-in-Managed-Care-by-State-July-1-2015.pdf, p. 83. ↩︎

- Share of plans operating statewide may be underrepresented due to the over representation of non-profit plans among survey respondents. Only 54% of responding for-profit plans do not operate statewide. ↩︎

- Dental care is covered for all children in Medicaid under EPSDT, but adult dental benefits are offered at state option. However, MCOs have flexibility to use administrative savings within their capitation rates to provide services beyond Medicaid benefits required under their contracts. Other surveys indicate that many plans provide dental services as an additional service outside their state Medicaid contract. See: Health Management Associates and Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Moving Ahead in Uncertain Times: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018 (Lansing, MI: Health Management Associates and Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, Oct. 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-moving-ahead-in-uncertain-times-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2017-and-2018/. ↩︎

- Health Management Associates and Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid Moving Ahead in Uncertain Times: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018 (Lansing, MI: Health Management Associates and Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, Oct. 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-moving-ahead-in-uncertain-times-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2017-and-2018/, p.2. ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, MACStats: Medicaid and CHIP Data Book (Washington, DC: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, December 2017), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EXHIBIT-29.-Percentage-of-Medicaid-Enrollees-in-Managed-Care-by-State-July-1-2015.pdf, p.83. ↩︎

- Eligible plans included any plan that had a 2016 Medicaid MCO contract (as several survey questions referred to plan operations in 2016) and was active during the data collection period in 2017 (as some survey questions referred to future/current plan operations). For more information about eligible plans, see “Methods” section. ↩︎

- Some plans in MCHIP states responded that they offer Children’s Medicaid Insurance Program (CHIP) as a line of business. Of plans that serve children in SCHIP states, 71% responded that they offer Children’s Medicaid Insurance Program (CHIP) as a line of business. ↩︎

- Share of plans operating statewide may be underrepresented due to the over representation of non-profit plans among survey respondents. Only 54% of responding for-profit plans do not operate statewide. ↩︎

- “Other” organization types identified by plans include: public agency; quasi-government; joint powers agency not-for-profit public entity; government/local health initiative; non-profit, public agency; independent public agency; public for-profit; private LLC; publicly traded; and private mutual. ↩︎