2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey

Abstract

This annual survey of employers provides a detailed look at trends in employer-sponsored health coverage including premiums, employee contributions, cost-sharing provisions, offer rates, wellness programs, and employer practices. The 2018 survey included 2,160 interviews with non-federal public and private firms. Annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage reached $19,616 this year, up 5% from last year, with workers on average paying $5,547 toward the cost of their coverage. The average deductible among covered workers in a plan with a general annual deductible is $1,573 for single coverage. Fifty-six percent of small firms and 98% of large firms offer health benefits to at least some of their workers, with an overall offer rate of 57%. Survey results are released in several formats, including a full report with downloadable tables on a variety of topics, a summary of findings, and an article published in the journal Health Affairs.

News release

- A news release announcing the publication of the 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey is available here.

Summary of findings

- The Summary of Findings provides an overview of the 2018 survey results and is available under the Summary of Findings section.

Full report

- The complete Employer Health Benefits Survey report includes over 200 exhibits and is available under the Report The “Report” section contains 14 separate sections. Users can view each section separately or download the section exhibits from the right side of the respective section page.

Health affairs

- The peer-reviewed journal Health Affairs has published an article with key findings from the 2018 survey: Health Benefits In 2018: Modest Growth in Premiums, Higher Worker Contributions at Firms with More Low-Wage Workers, More Workers Face a Deductible.

Related analysis

- This related brief on the Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker examines employer claims data to measure the uptake of telemedicine services by employees and their family members.

Web briefing

- On Wednesday, October 3rd, 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation held a reporters-only web briefing to release the 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey.

Interactive graphic

- This graphing tool allows users to look at changes in premiums and worker contributions for covered workers at different types of firms over time: Premiums and Worker Contributions Among Workers Covered by Employer-Sponsored Coverage, 1999-2018.

Key exhibits-chartpack

- Nearly thirty overview slides from the 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey are available as a slideshow or PDF.

Additional resources

- Standard errors for selected estimates are available in the Technical Supplement here.

- Employer Health Benefits Surveys from 1998–2017 are available here. Please note that historic survey reports have not been revised with methodological changes.

- Researchers may request a public use dataset by going to Contact Us and choosing “TOPIC: Health Costs.”

Researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation and NORC at the University of Chicago designed and analyzed the survey.

Summary Of Findings

Employer-sponsored insurance covers over half of the non-elderly population; approximately 152 million nonelderly people in total.1 To provide current information about employer-sponsored health benefits, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) conducts an annual survey of private and non-federal public employers with three or more workers. This is the twentieth survey and reflects employer-sponsored health benefits in 2018.

HEALTH INSURANCE PREMIUMS AND WORKER CONTRIBUTIONS

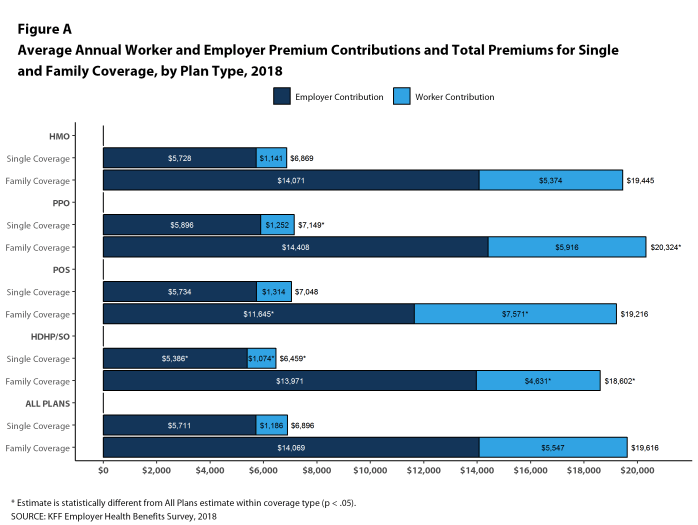

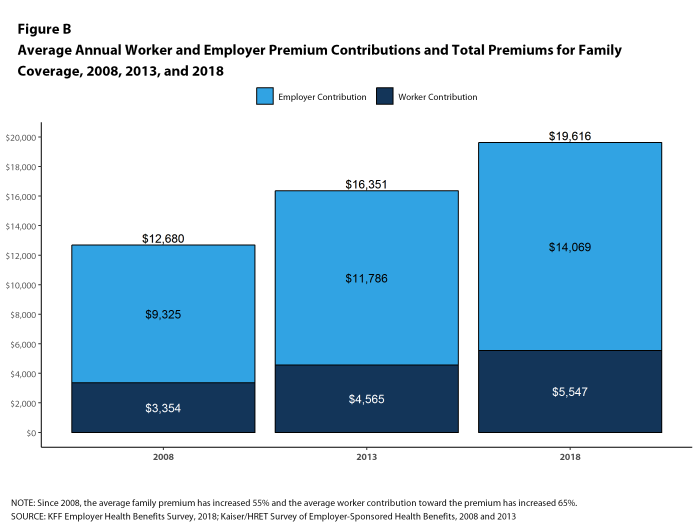

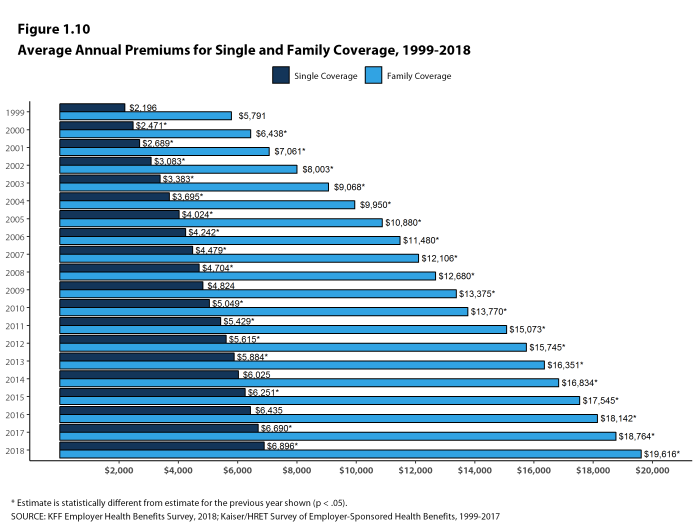

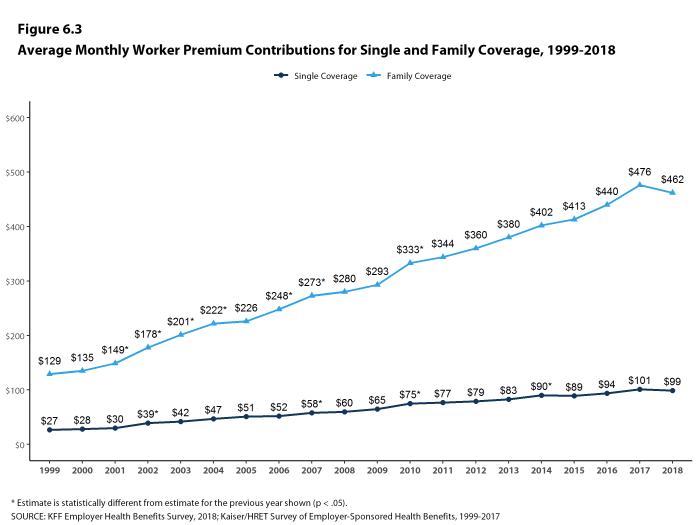

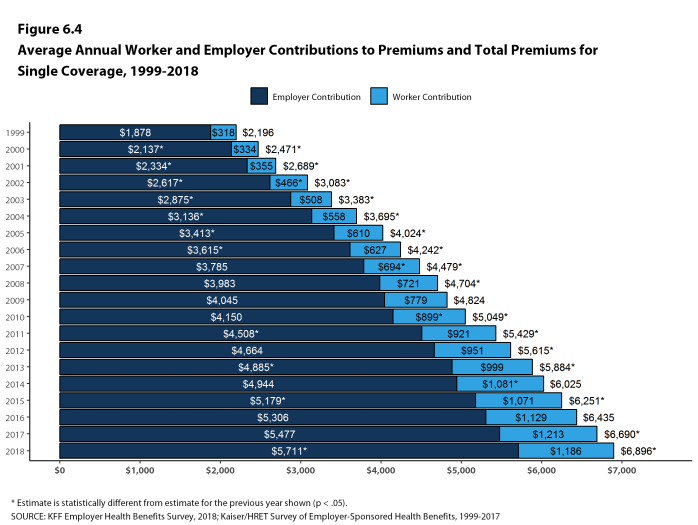

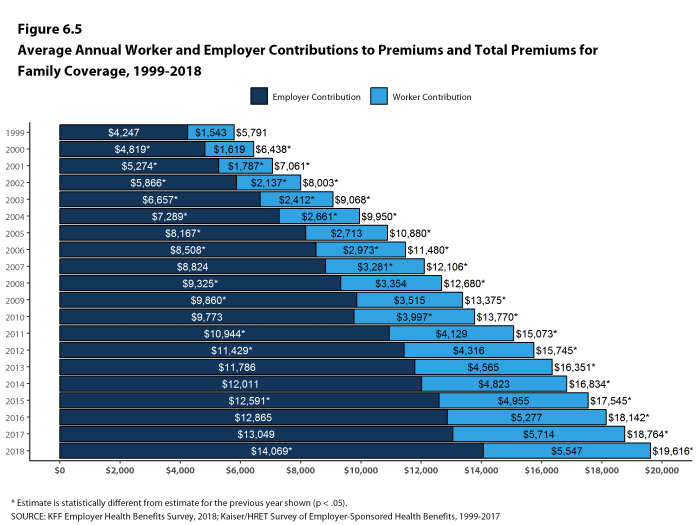

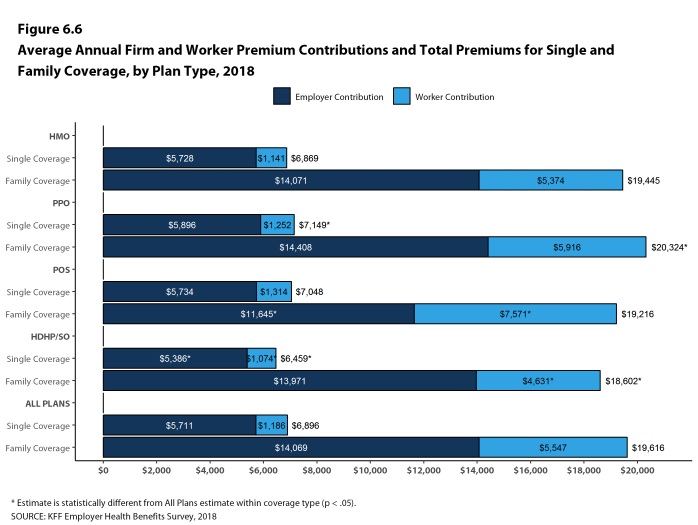

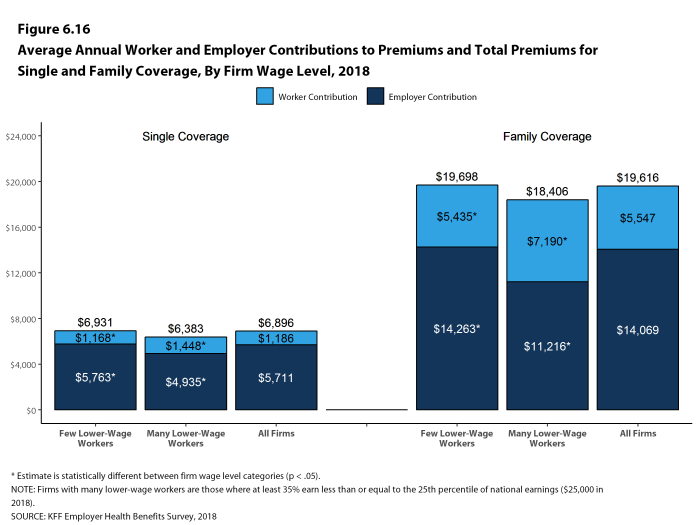

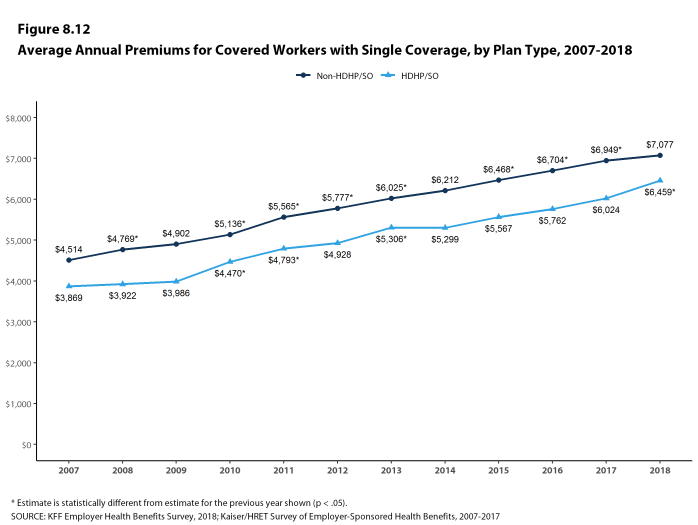

The average annual premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance in 2018 are $6,896 for single coverage and $19,616 for family coverage [Figure A]. Over the past year, the average single premium increased 3% and the average family premium increased 5%. Workers’ wages increased 2.6% and inflation increased 2.5% over the past year.2 The average premium for family coverage has increased 20% since 2013 and 55% since 2008 [Figure B].

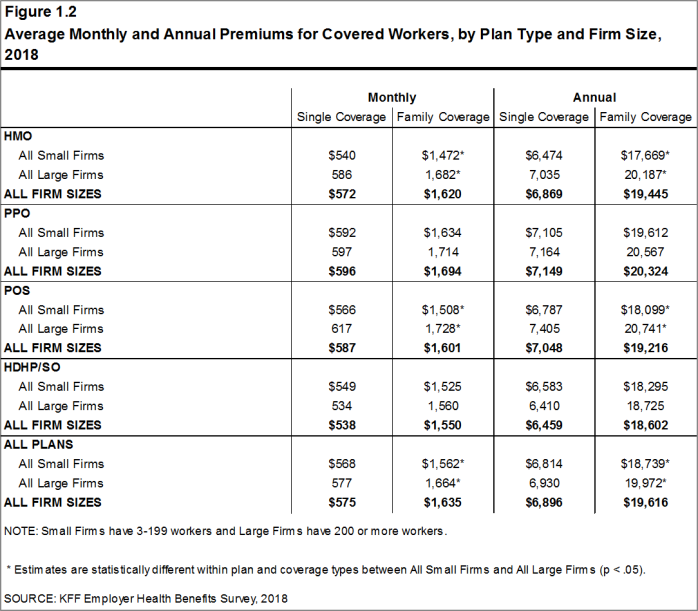

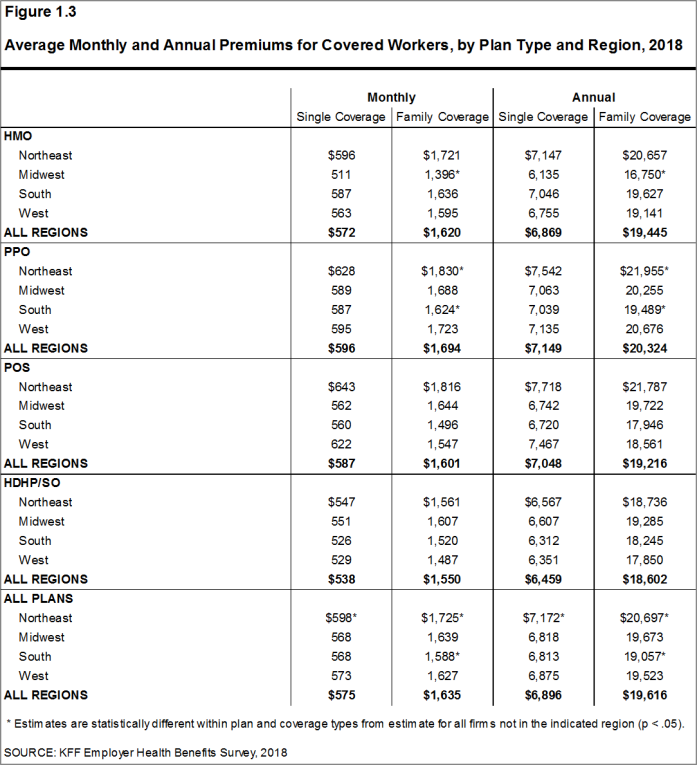

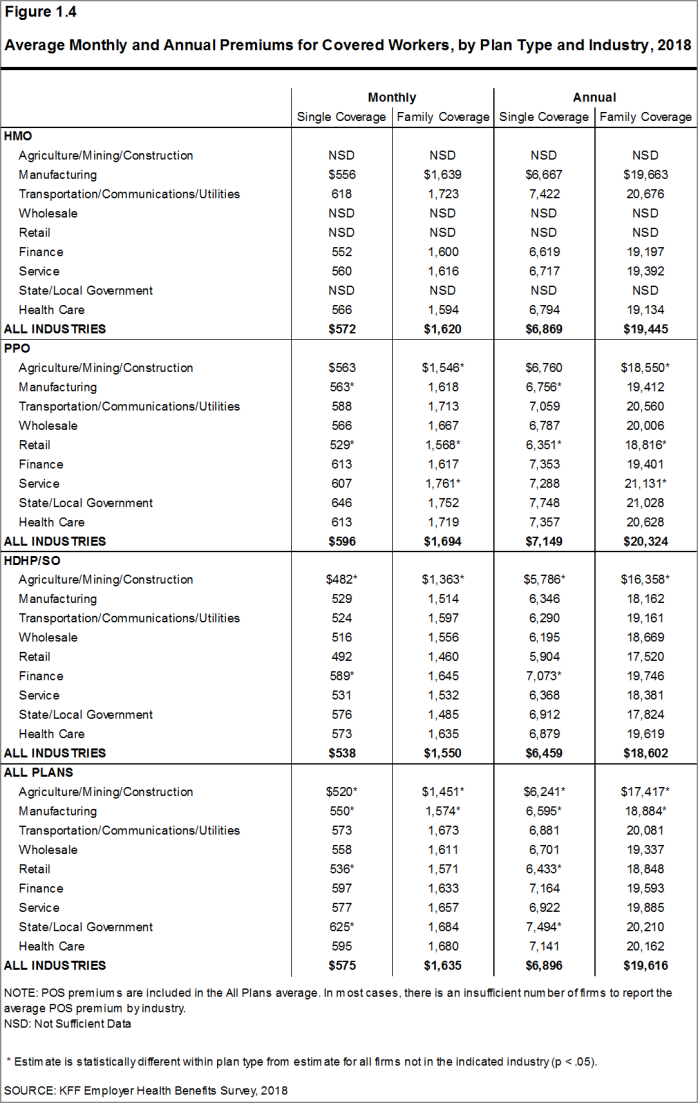

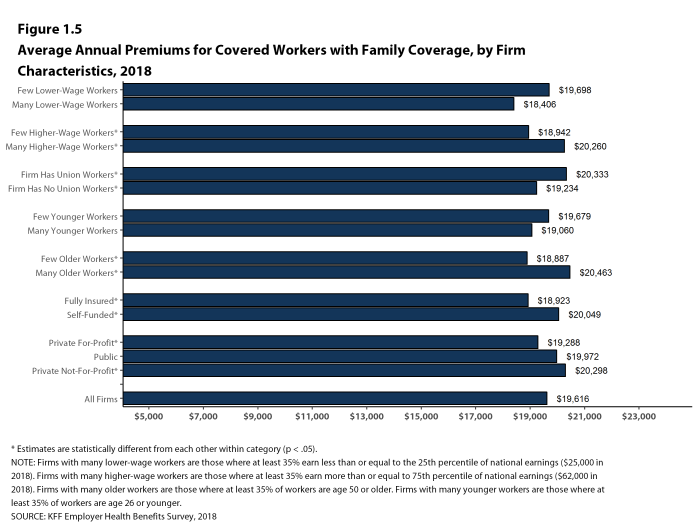

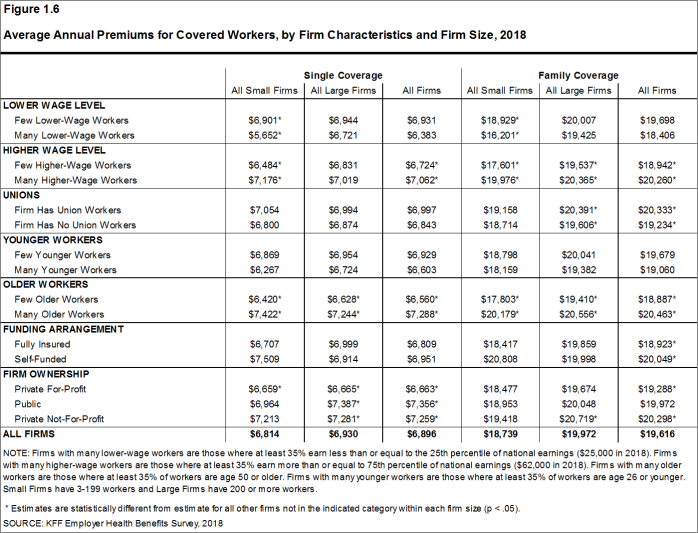

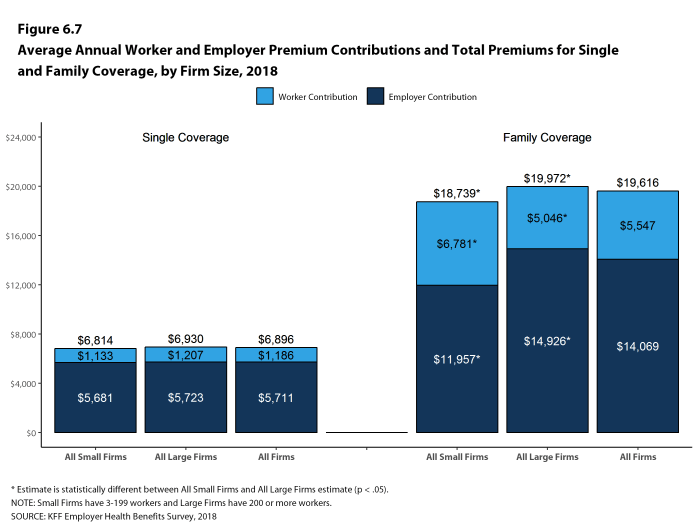

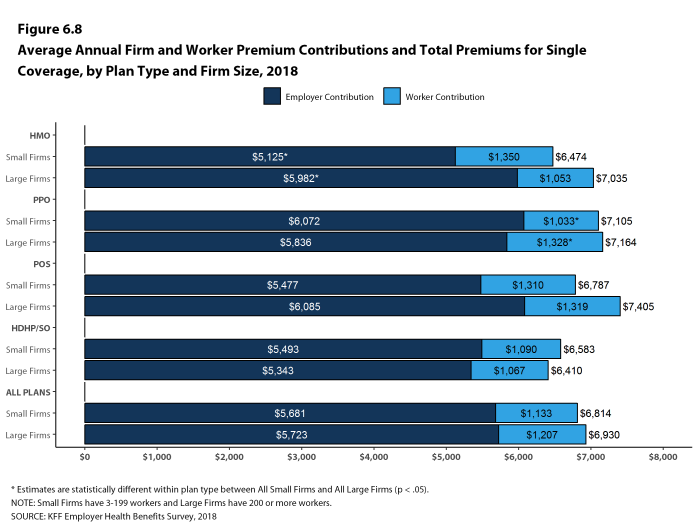

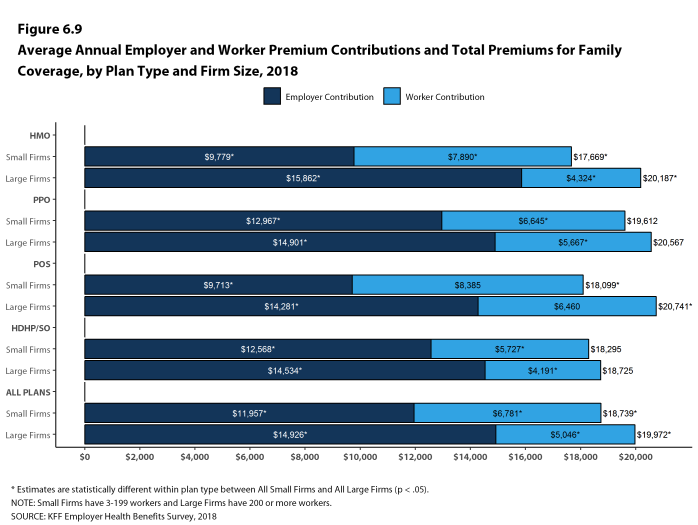

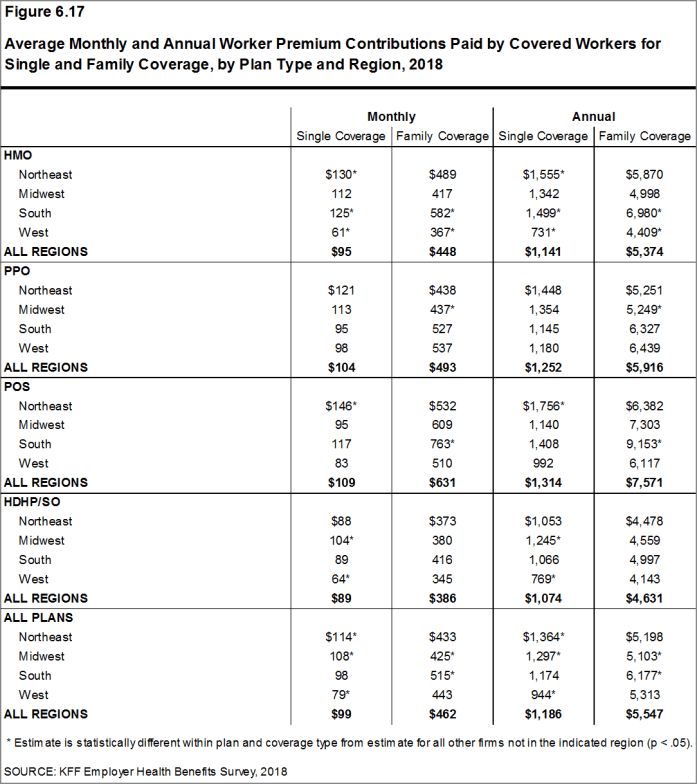

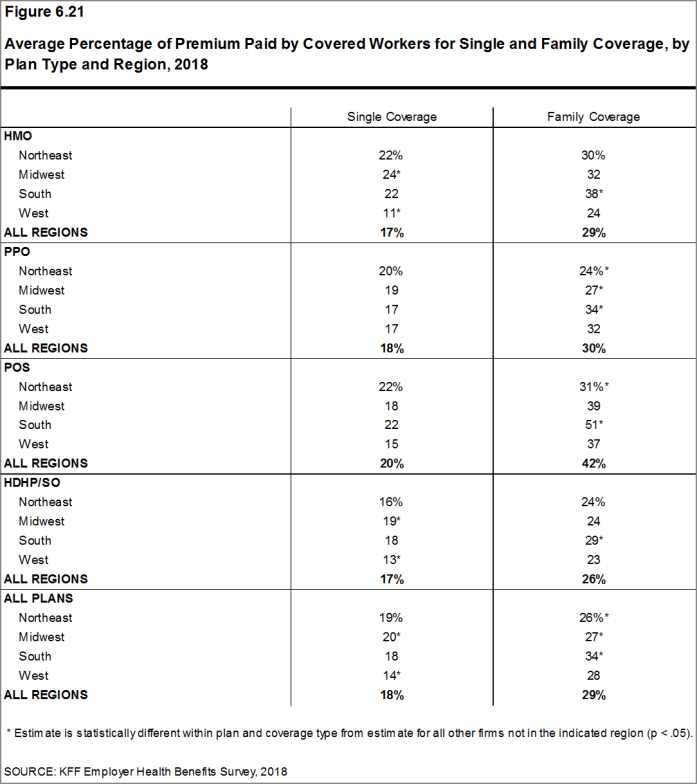

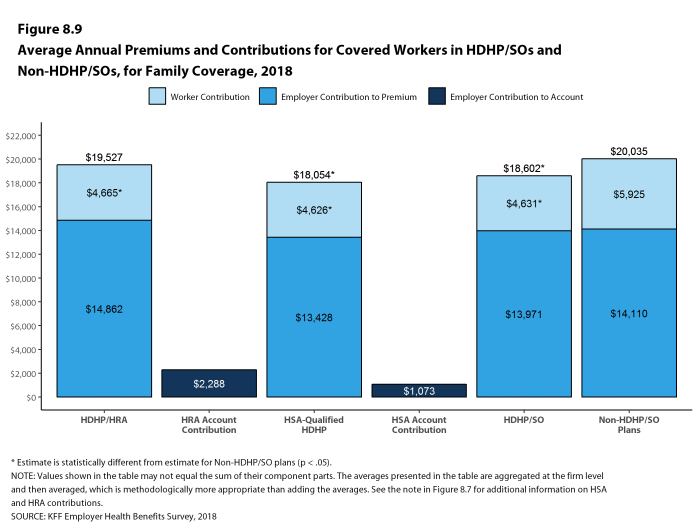

While covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) and large firms (200 or more workers) have similar average premiums for single coverage, covered workers in small firms have a lower average premium for family coverage ($18,739 vs. $19,972). Average premiums for high-deductible health plans with a savings option (HDHP/SOs) are considerably lower than the overall average for all plan types for both single and family coverage, at $6,459 and $18,602, respectively [Figure A]. The average premiums for covered workers in the Northeast are higher than the average premiums for workers in other regions for both single and family coverage; the average family premium for covered workers in the South is relatively low. Covered workers at private for-profit firms have lower average annual premiums than covered workers at public firms or private not-for-profit firms for both single and family coverage.

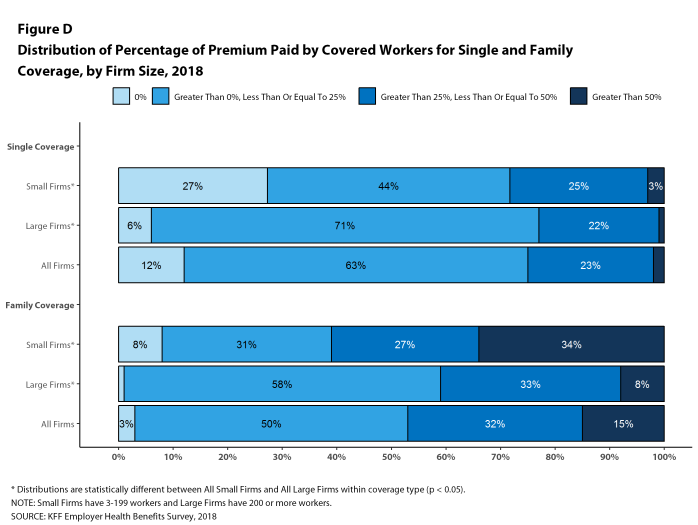

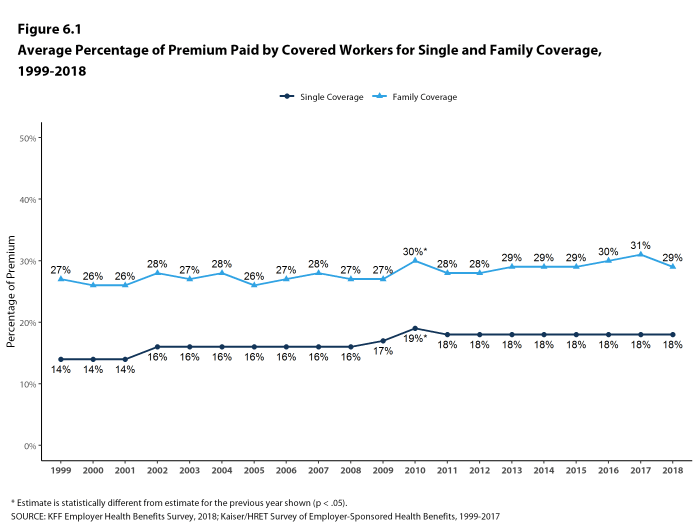

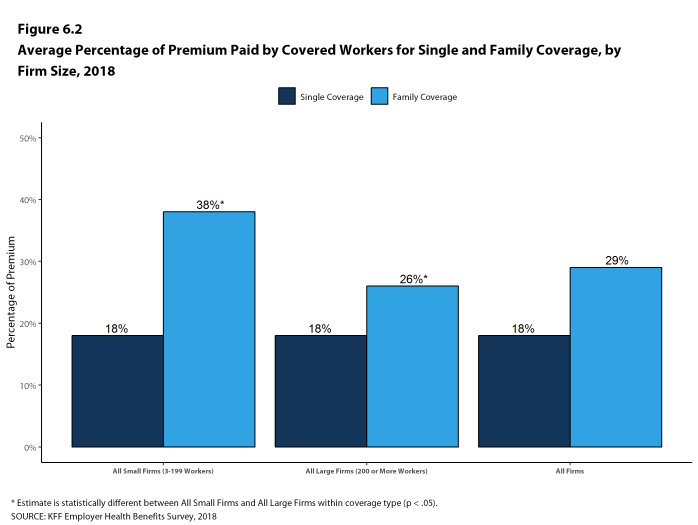

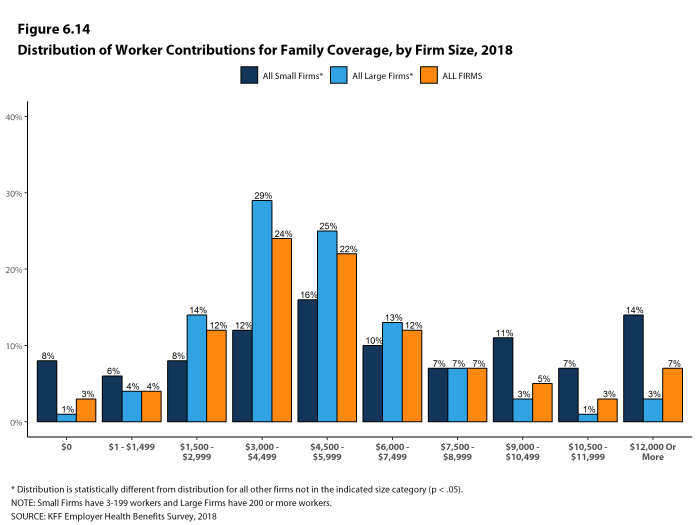

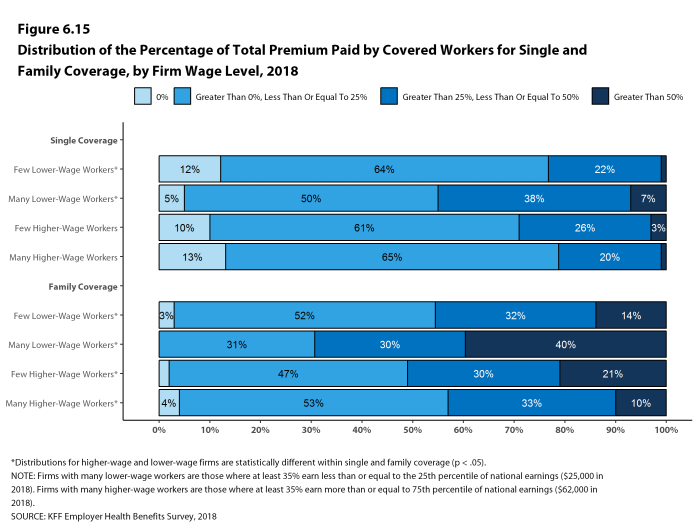

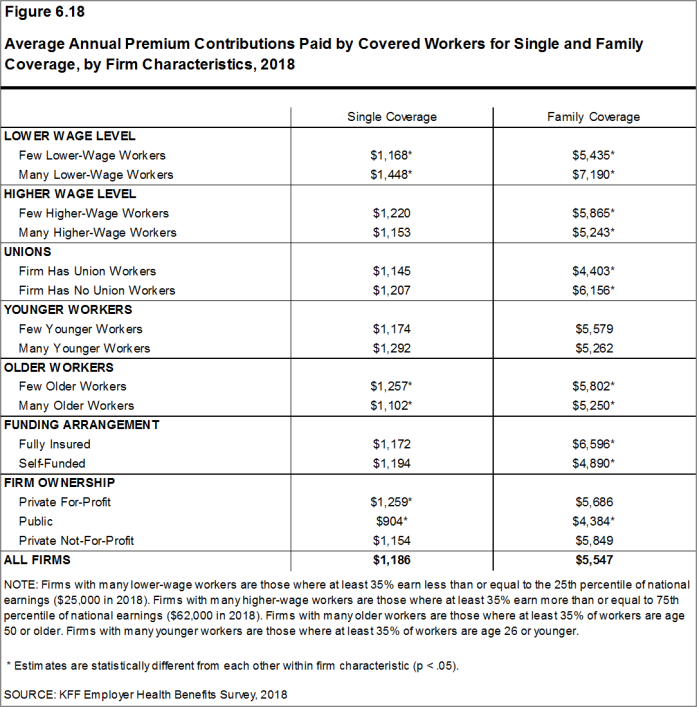

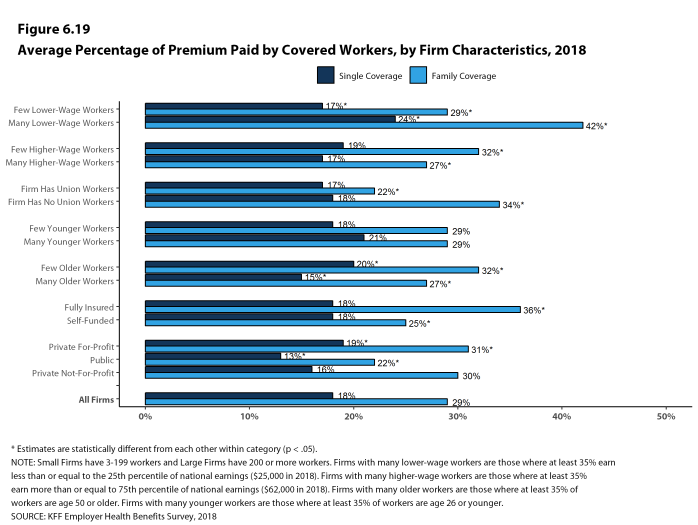

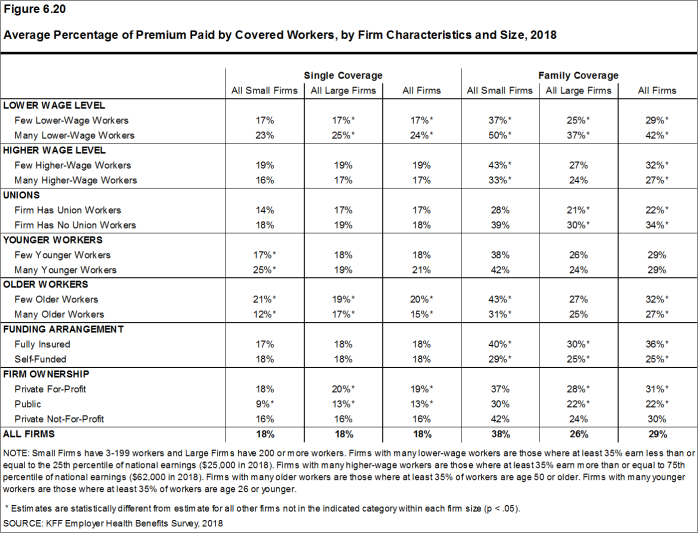

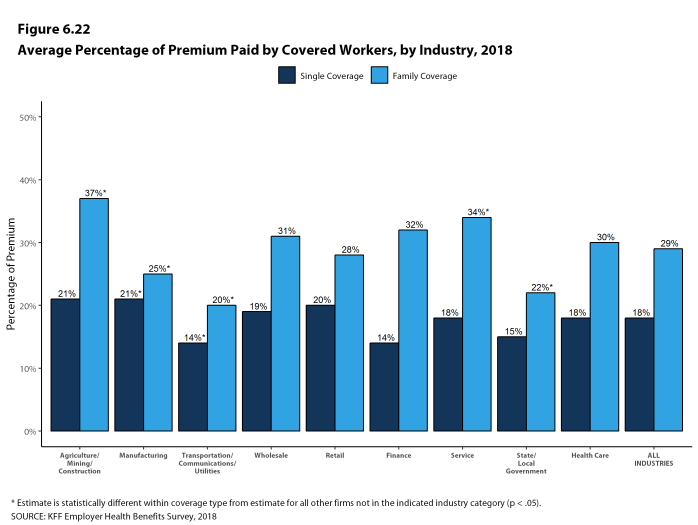

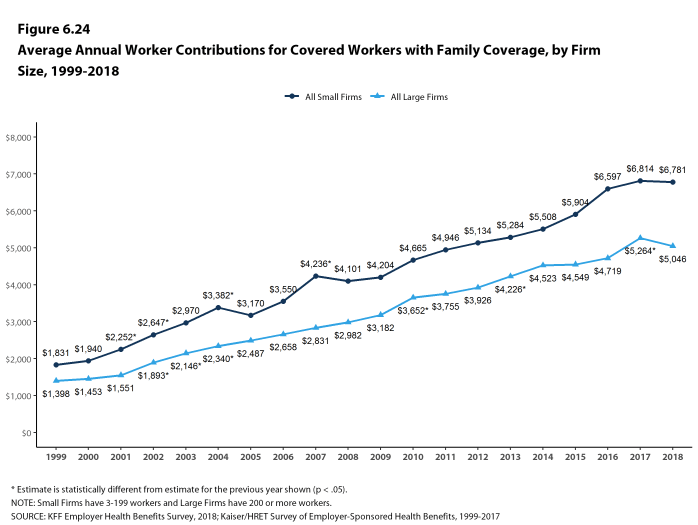

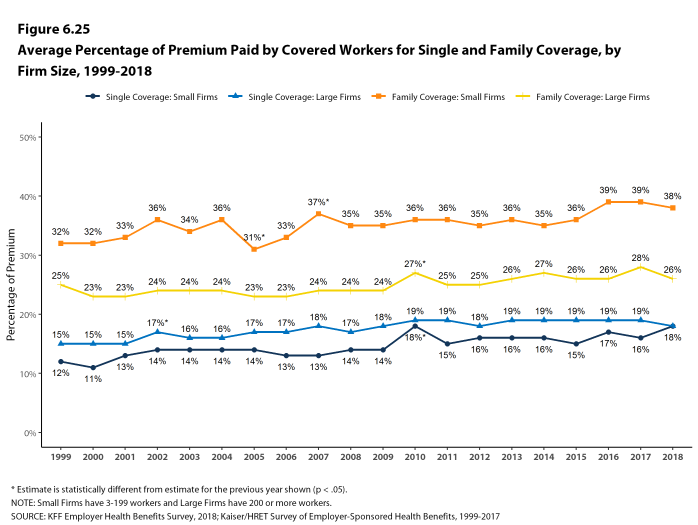

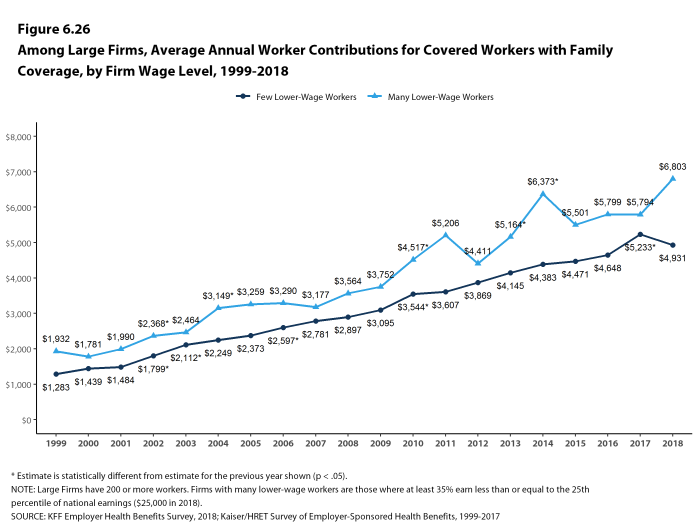

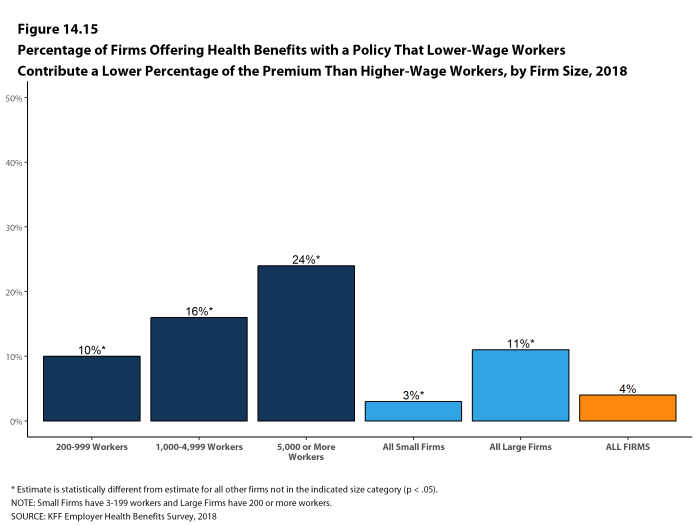

Most covered workers make a contribution toward the cost of the premium for their coverage. On average, covered workers contribute 18% of the premium for single coverage and 29% of the premium for family coverage. Workers in small firms contribute a higher average percentage of the premium for family coverage than workers in large firms (38% vs. 26%). On average, covered workers in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers (where at least 35% of workers earn $25,000 a year or less) have higher contribution rates for single coverage (24% vs. 17%) and family coverage (42% vs. 29%) than those in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers.3

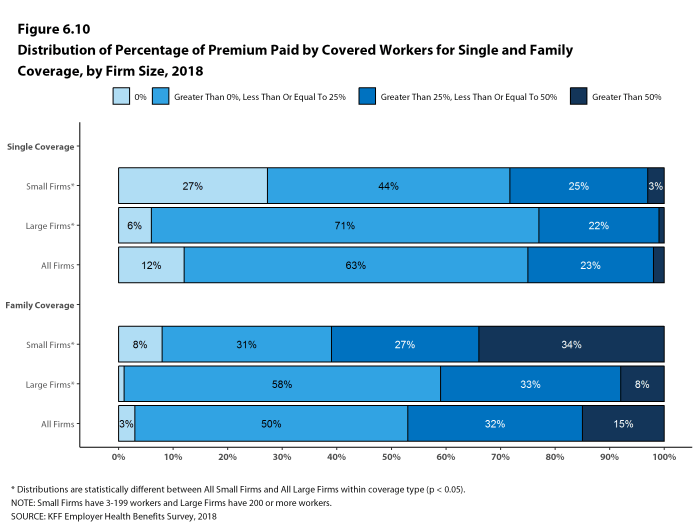

Twenty-seven percent of covered workers in small firms are in a plan where the employer pays the entire premium for single coverage, compared to 6% of covered workers in large firms. In contrast, 34% of covered workers in small firms are in a plan where they must contribute more than one-half of the premium for family coverage, compared to 8% of covered workers in large firms [Figure D].

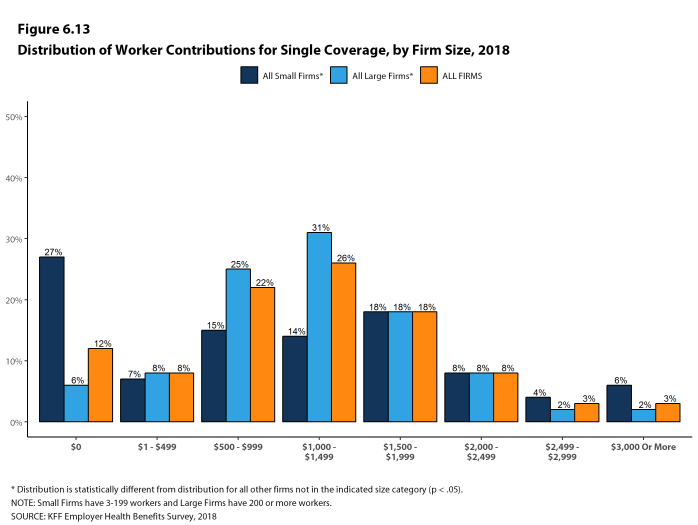

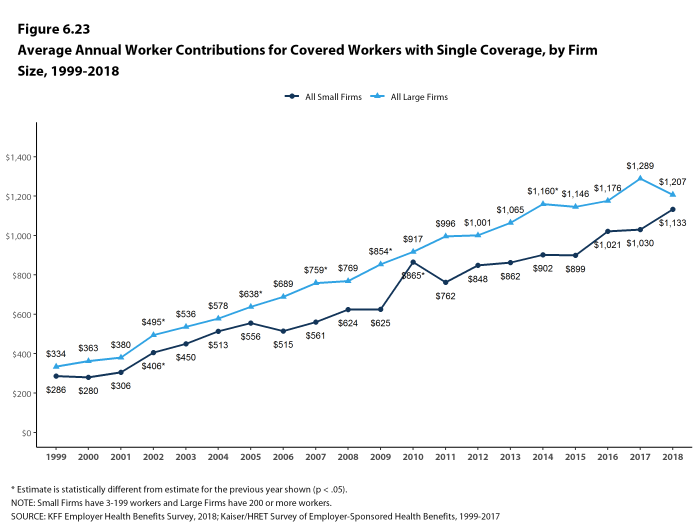

The average annual dollar amounts contributed by covered workers for 2018 are $1,186 for single coverage and $5,547 for family coverage, similar to the amounts last year. The average dollar contribution for family coverage has increased 21% since 2013 and 65% since 2008 [Figure B]. Average contribution amounts for covered workers in HDHP/SOs are lower than average for both single and family coverage [Figure A]. Seven percent of covered workers, including 14% of covered workers in small firms, are in a plan with a worker contribution of $12,000 or more for family coverage.

Figure A: Average Annual Worker and Employer Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2018

Figure B: Average Annual Worker and Employer Premium Contributions and Total Premiums for Family Coverage, 2008, 2013, and 2018

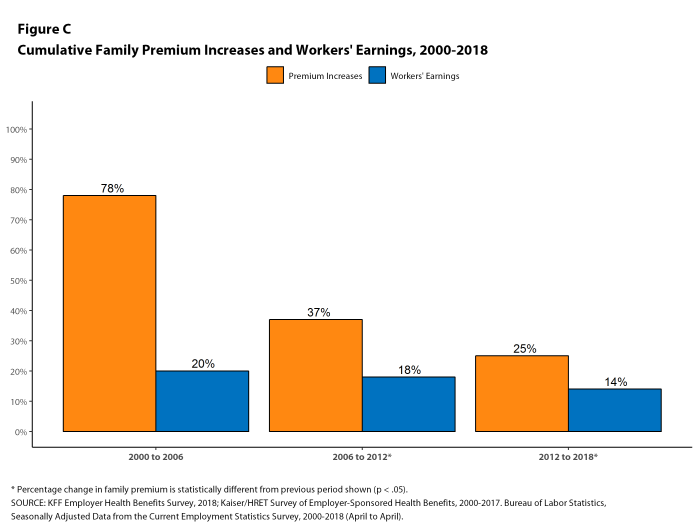

Figure C: Cumulative Family Premium Increases and Workers’ Earnings, 2000-2018

Figure D: Distribution of Percentage of Premium Paid by Covered Workers for Single and Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 2018

PLAN ENROLLMENT

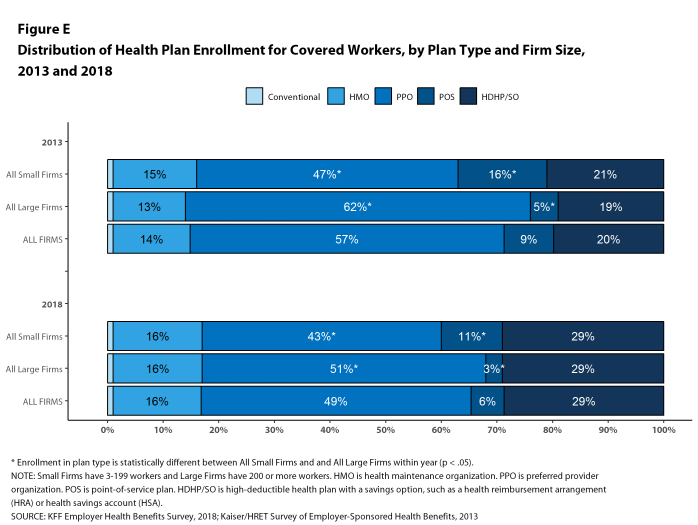

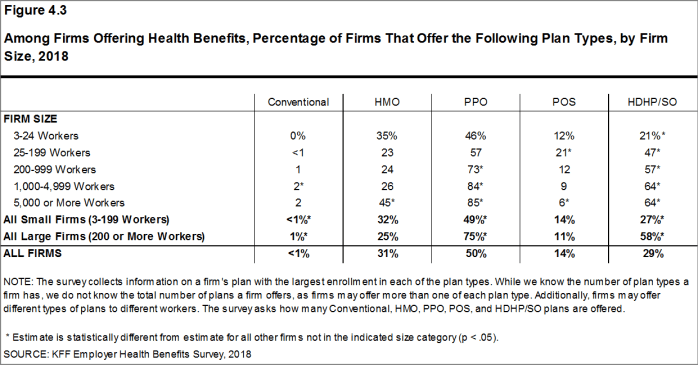

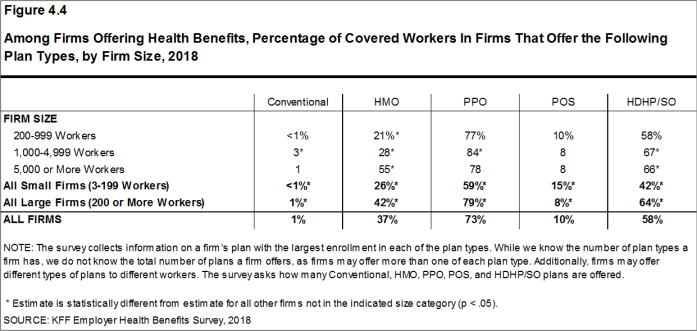

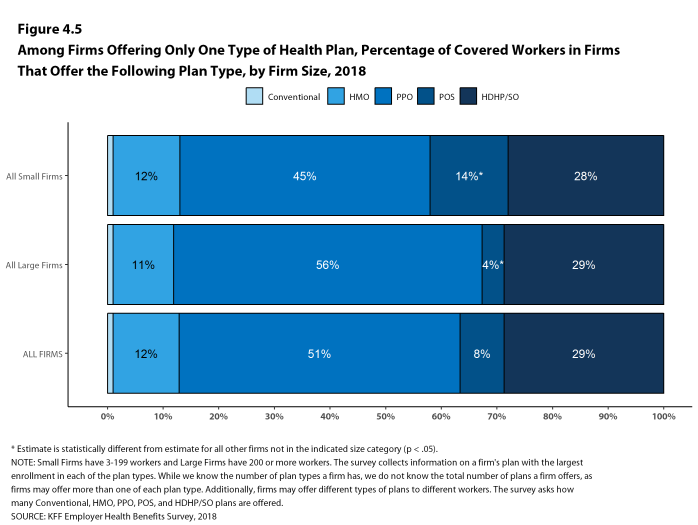

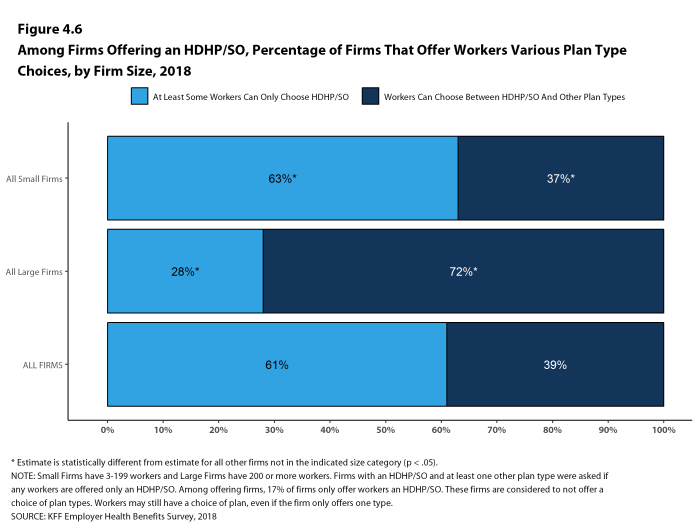

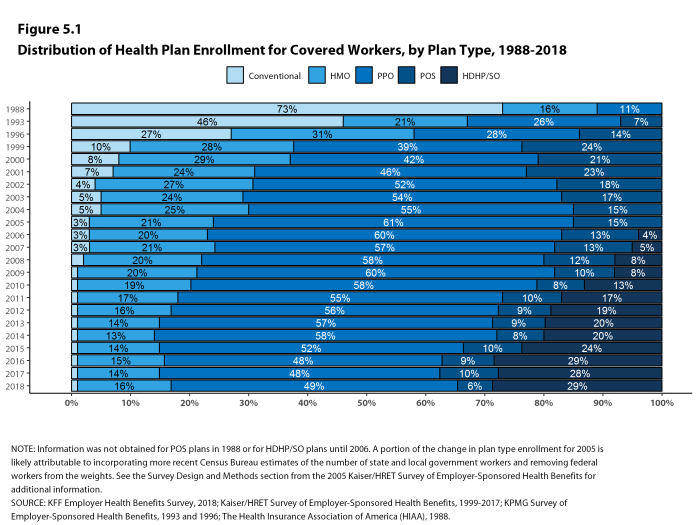

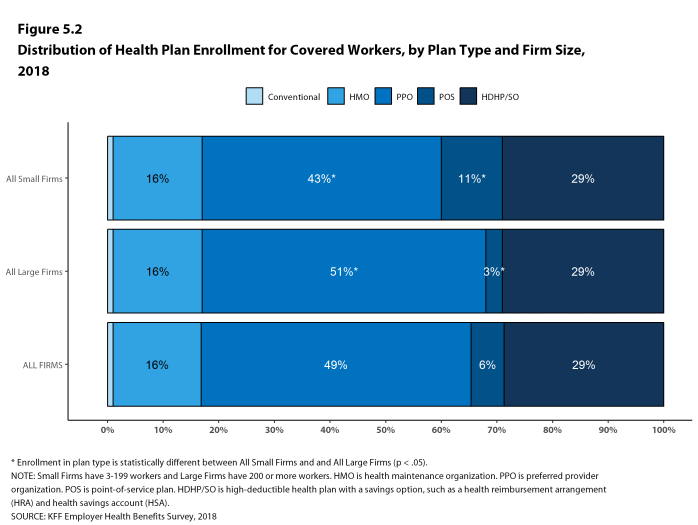

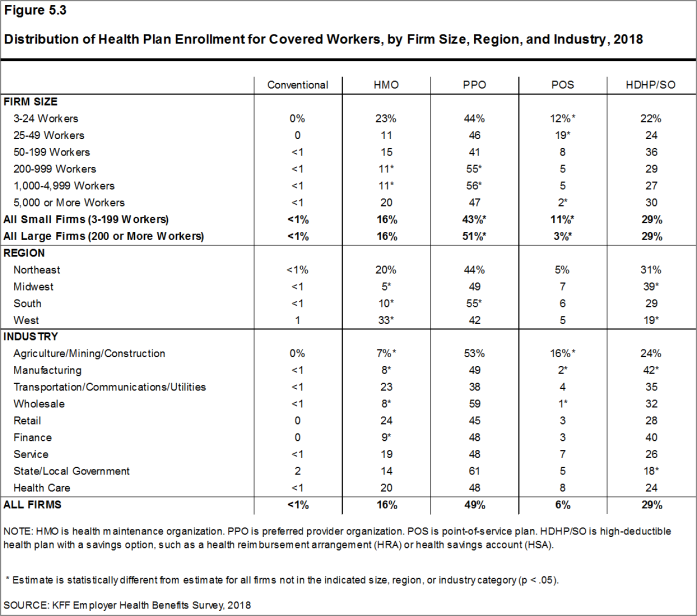

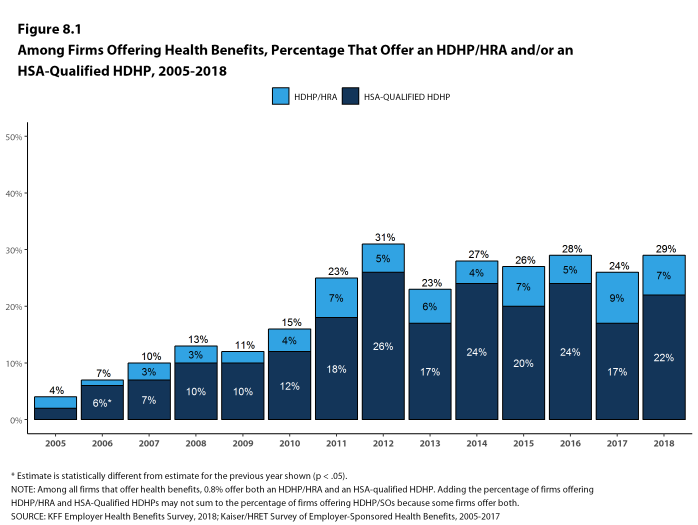

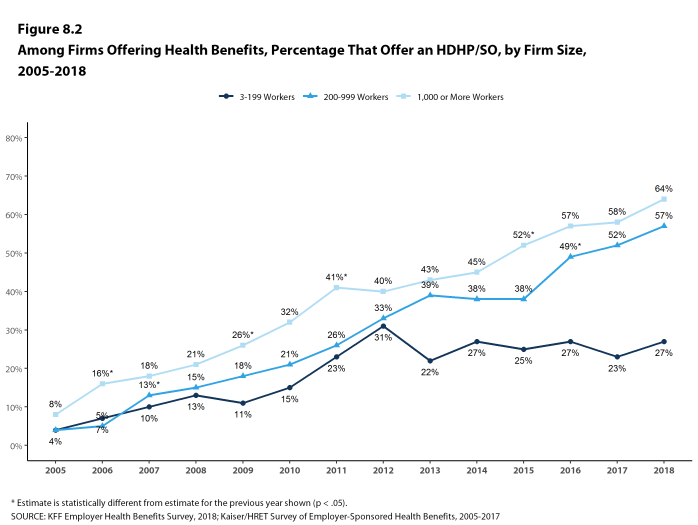

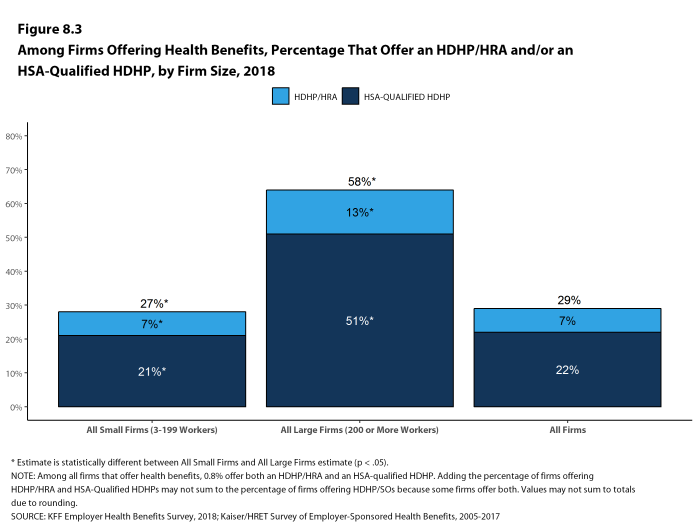

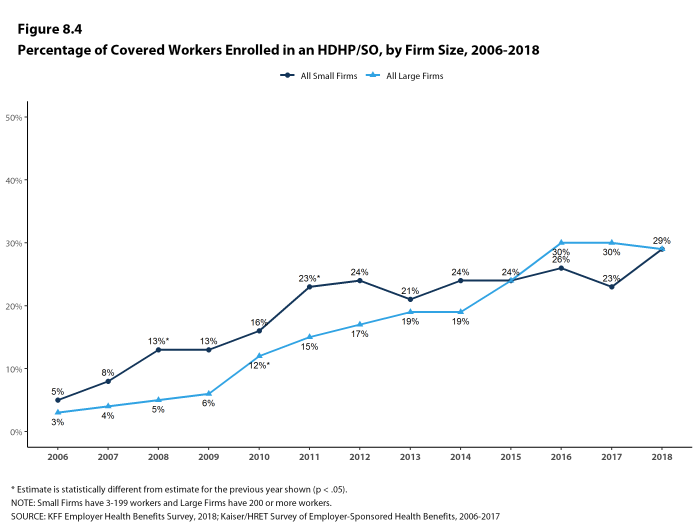

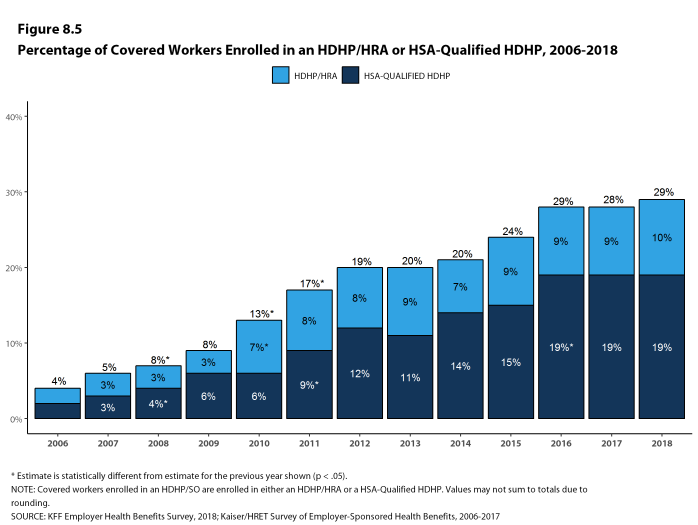

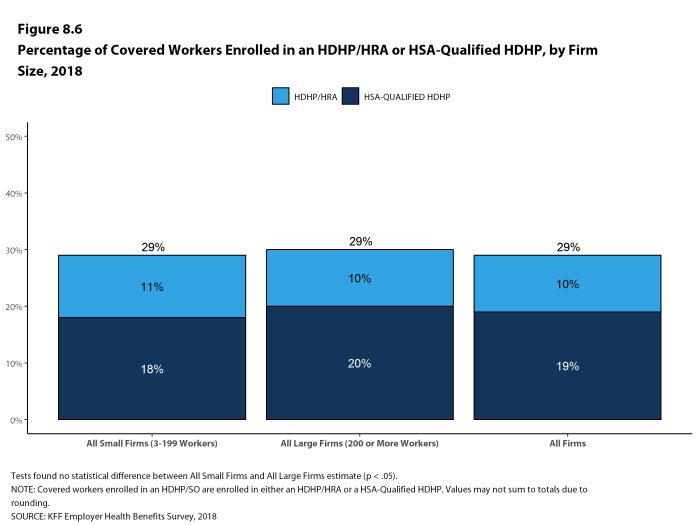

PPOs continue to be the most common plan type, enrolling 49% of covered workers in 2018. Twenty-nine percent of covered workers are enrolled in a high-deductible plan with a savings option (HDHP/SO), 16% in an HMO, 6% in a POS plan, and less than one percent in a conventional (also known as an indemnity) plan [Figure E]. Covered workers in the South (55%) are more likely to be enrolled in PPOs than workers in other regions. Covered workers in the Midwest (39%) are more likely to be enrolled in HDHP/SOs than workers in other regions, while covered workers in the West (19%) are less likely to be enrolled in HDHP/SOs. The share of covered workers enrolled in POS plans decreased from 10% in 2017 to 6% this year.

Figure E: Distribution of Health Plan Enrollment for Covered Workers, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2013 and 2018

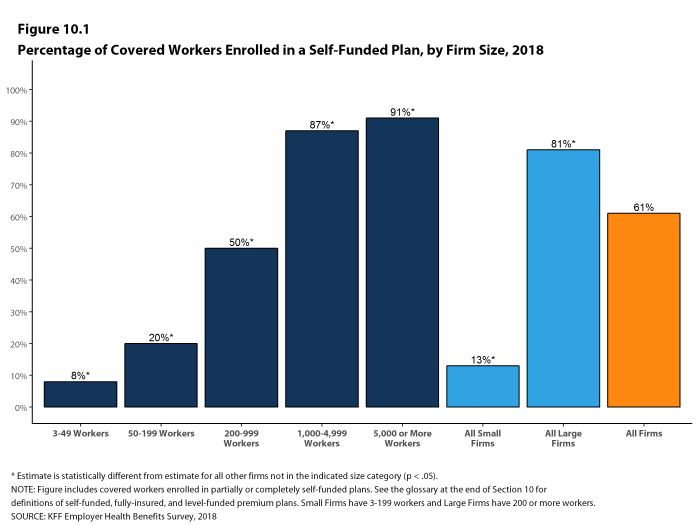

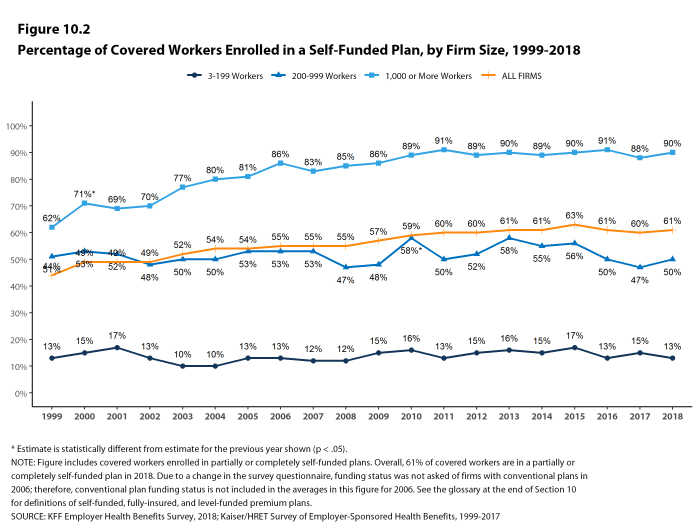

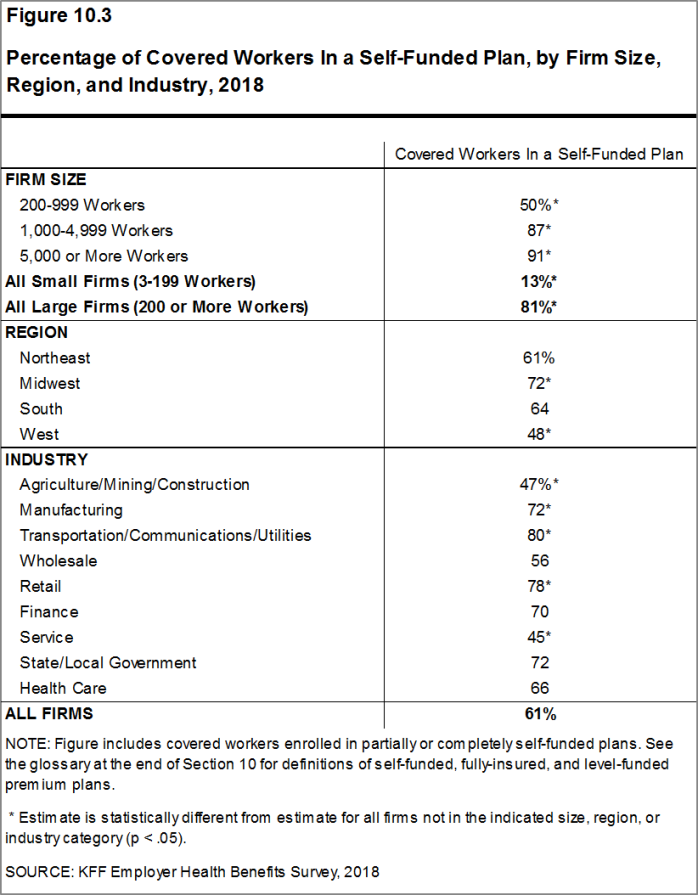

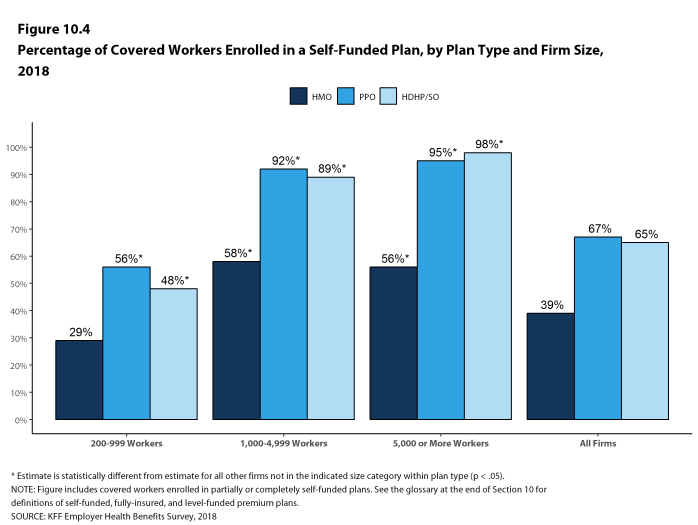

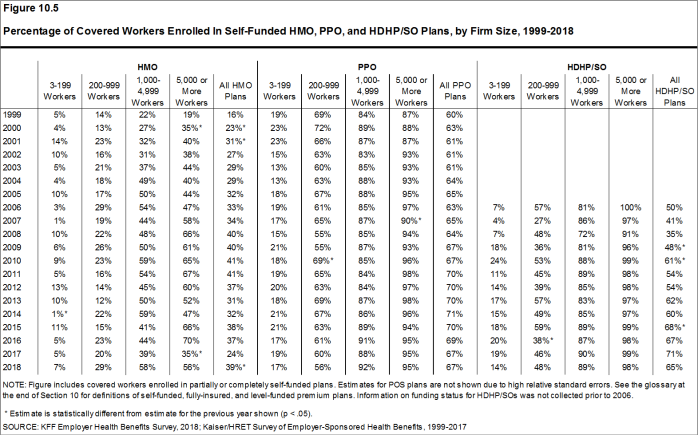

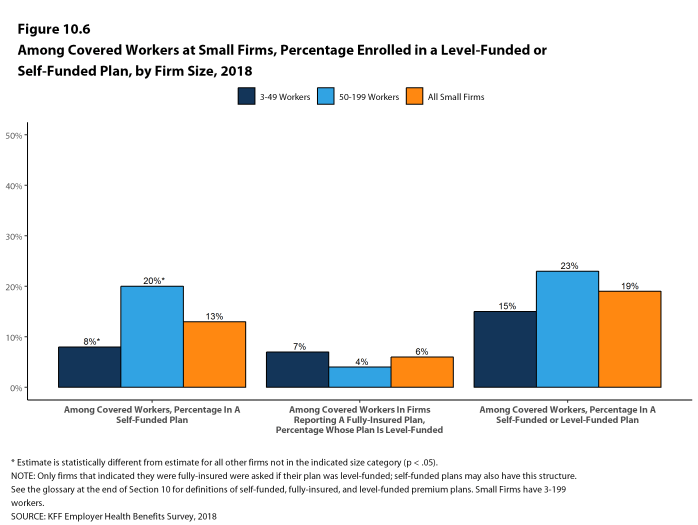

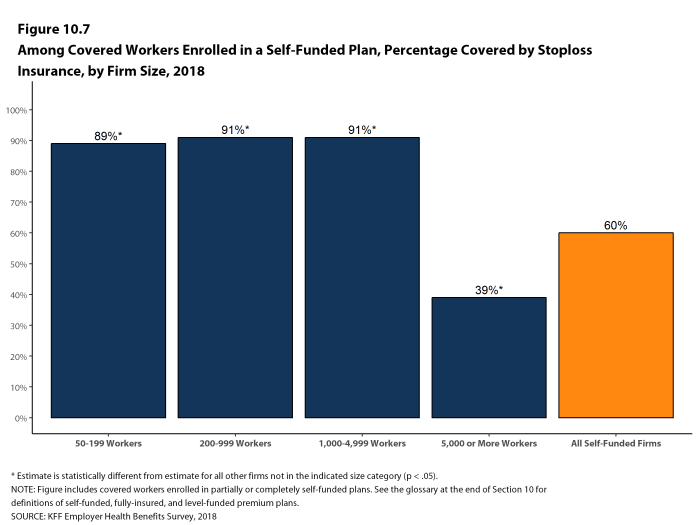

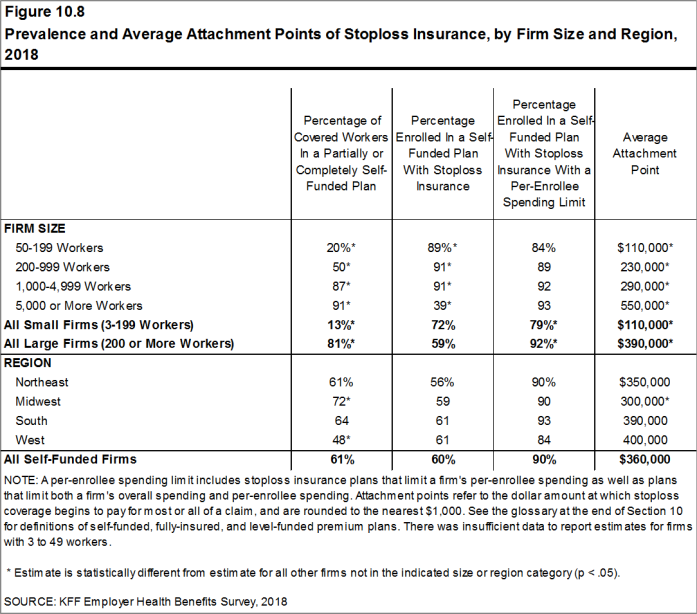

Self-Funding. Sixty-one percent of covered workers, including 13% of covered workers in small firms and 81% in large firms, are enrolled in plans that are either partially or completely self-funded. The percentage of covered workers in self-funded plans increases as the number of workers in a firm increases. The percentages of small and large firms with self-funded plans are similar to those last year.

In recent years, insurers have begun offering health plans that provide a nominally self-funded option for small or mid-sized employers that incorporates stoploss insurance with relatively low attachment points. These plans are sometimes referred to as level-funded plans because insurers calculate an expected monthly expense for the employer that includes a share of the estimated annual expense for benefits, the premiums for the stoploss protection, and an administrative fee. Due to the complexity of the funding (and regulatory status) of these plans, and because employers often pay a monthly amount that resembles a premium, they may be confused as to whether or not their health plan is self-funded or insured. To test this, we asked employers with fewer than 200 workers that responded that they had an insured health plan whether they had a level-funded plan. Among small firms that responded that they had an insured plan, 6% reported that they had a level-funded plan.

EMPLOYEE COST SHARING

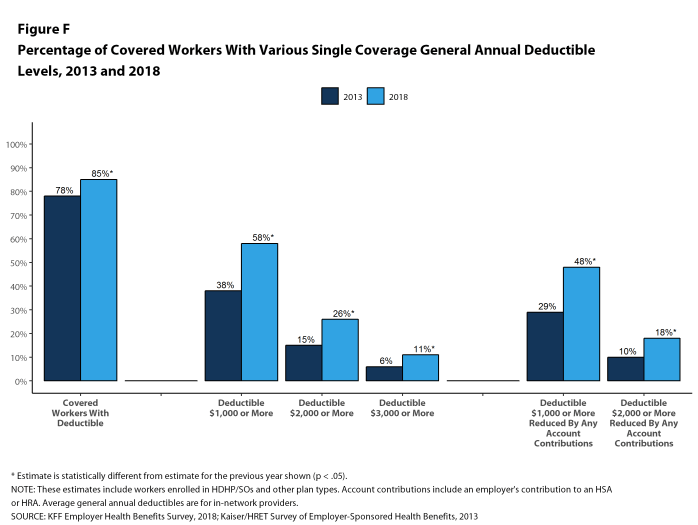

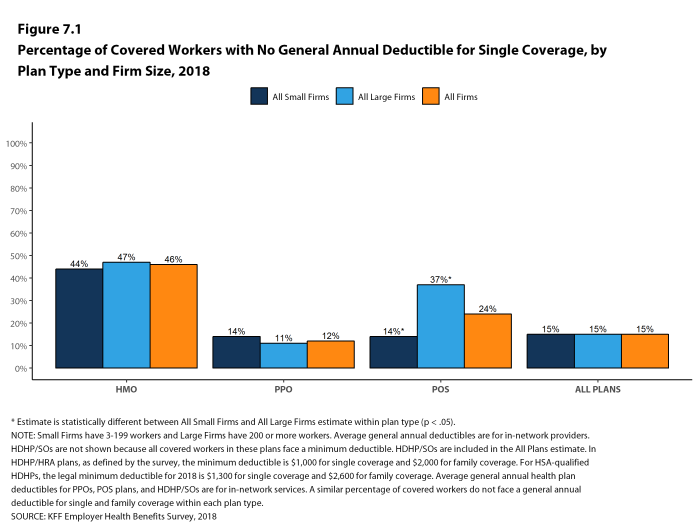

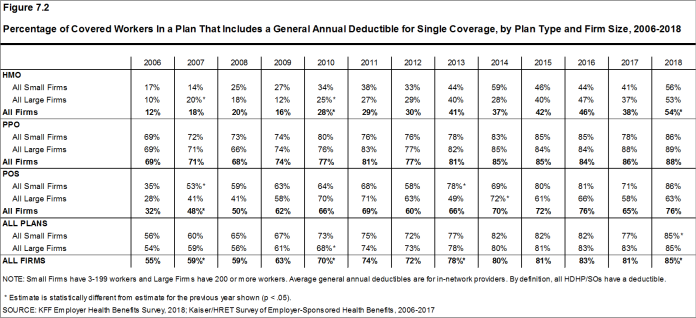

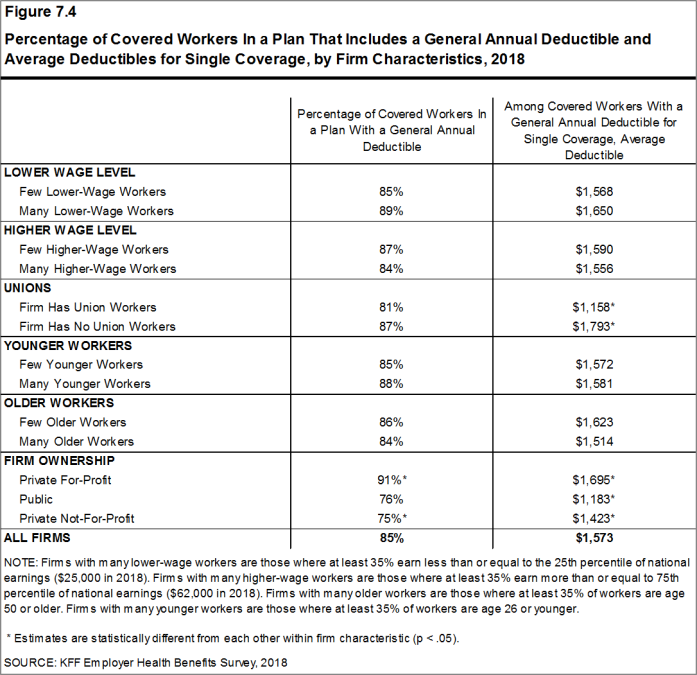

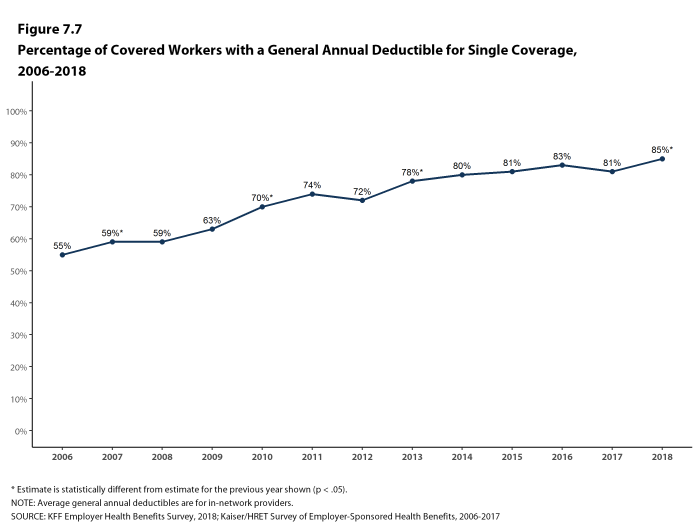

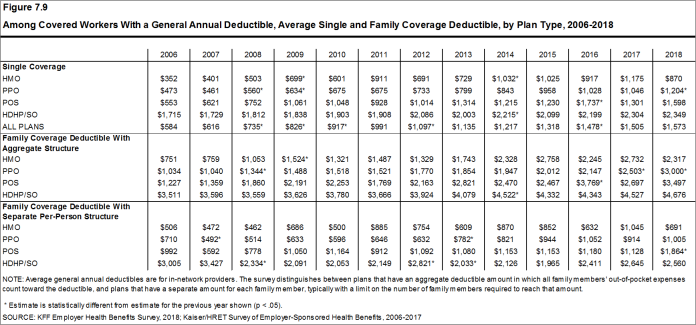

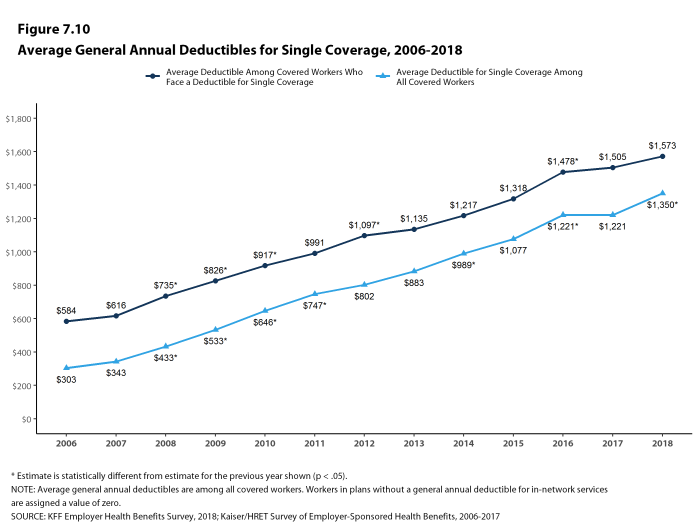

Most covered workers must pay a share of the cost when they use health care services. Eighty-five percent of covered workers have a general annual deductible for single coverage that must be met before most services are paid for by the plan, an increase from last year [Figure F]. Even workers without a general annual deductible often face other types of cost sharing when they use services, such as copayments or coinsurance for office visits and hospitalizations.

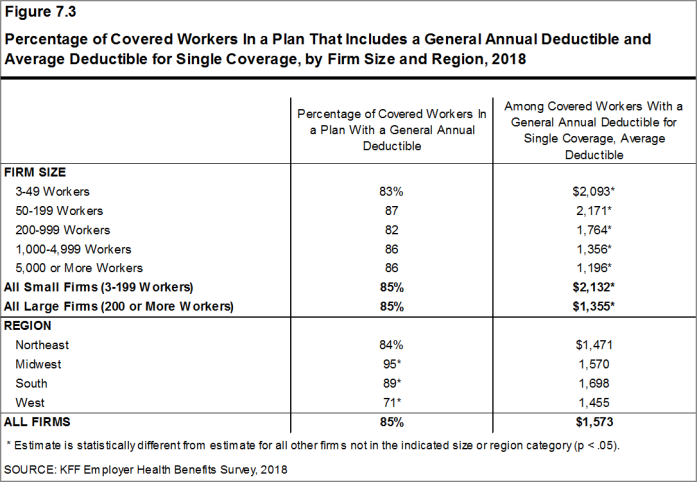

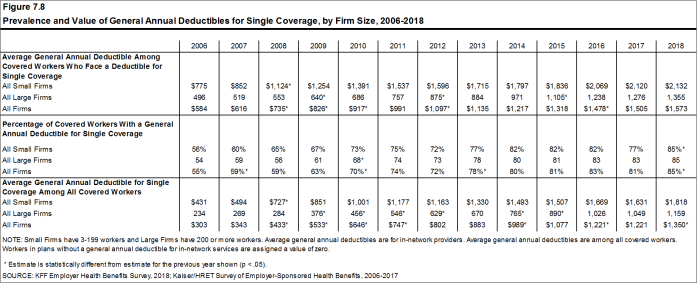

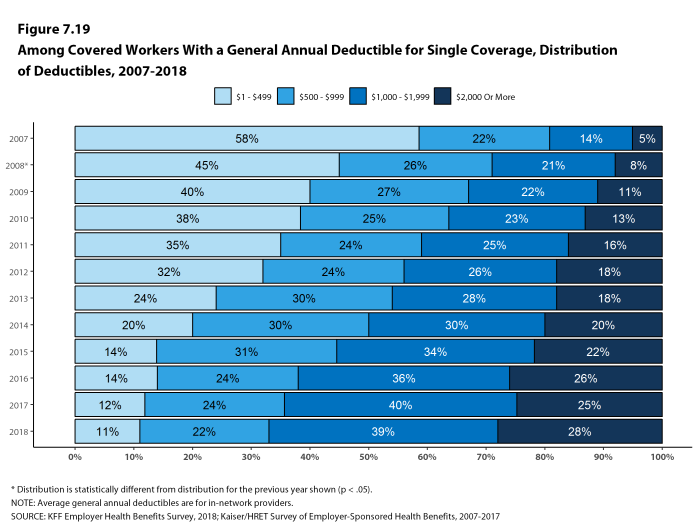

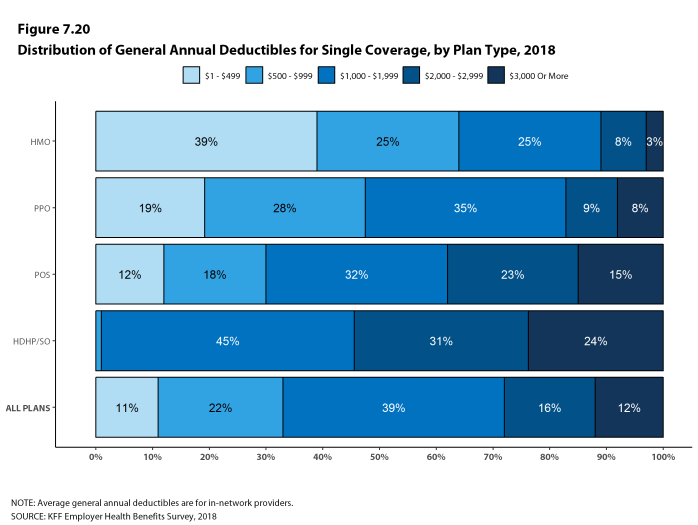

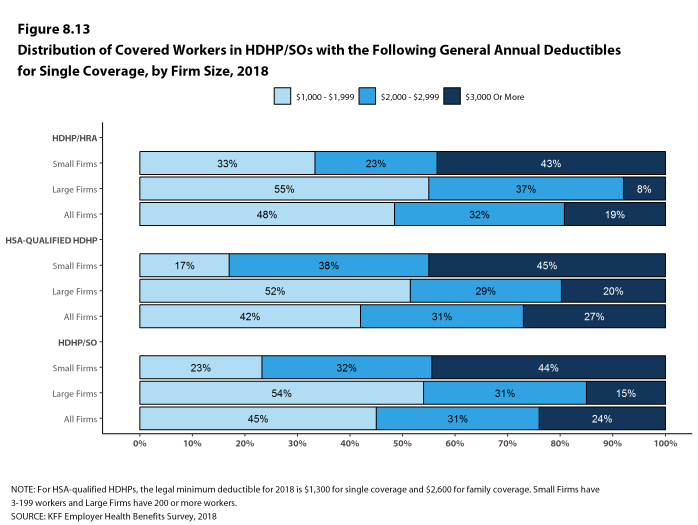

Among covered workers with a general annual deductible, the average deductible amount for single coverage is $1,573, similar to the average deductible last year. The average deductible for covered workers is higher in small firms than large firms ($2,132 vs. $1,355).

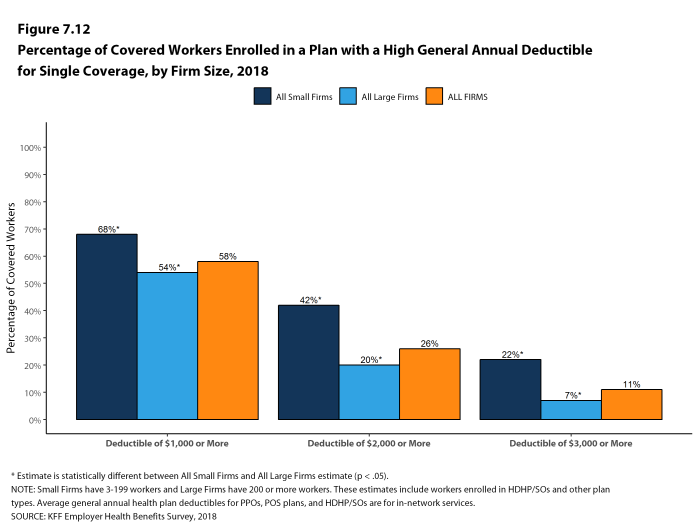

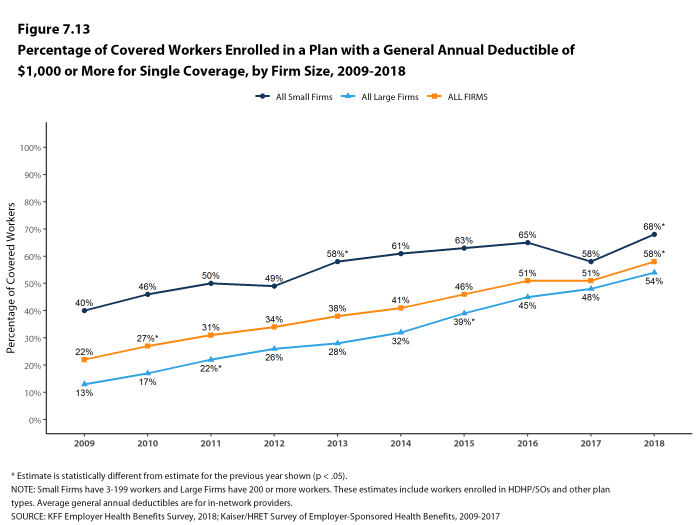

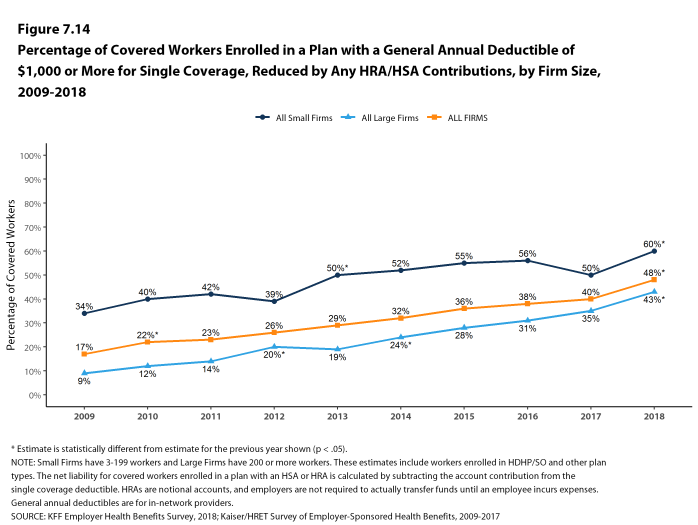

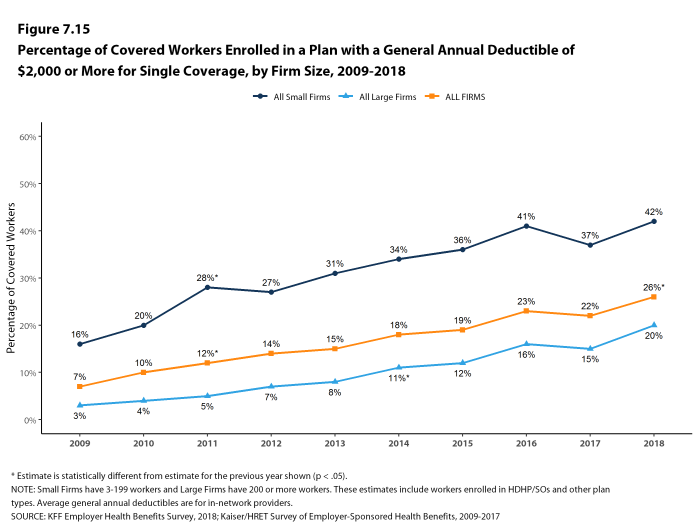

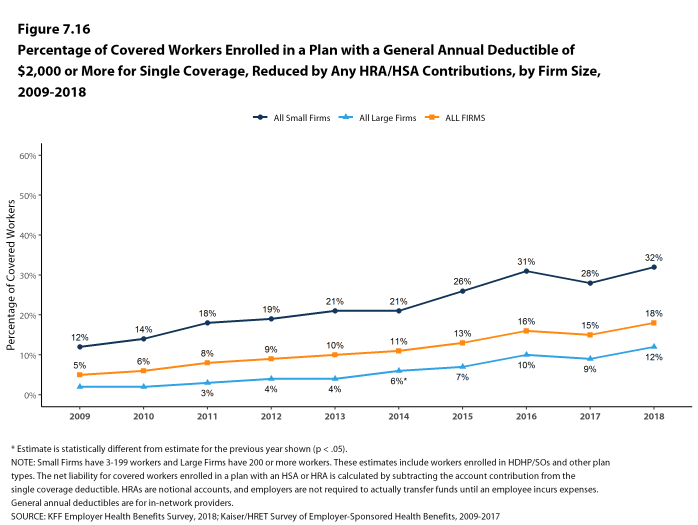

Assigning a zero deductible amount to those in plans without a general annual deductible, the average deductible among all covered workers is $1,350, an increase from the amount last year ($1,221). Over the past five years, the average annual deductible among all covered workers has increased 53%. Forty-two percent of covered workers in small firms and 20% of covered workers in large firms are in a plan with a deductible of at least $2,000 for single coverage, similar to the percentages last year.

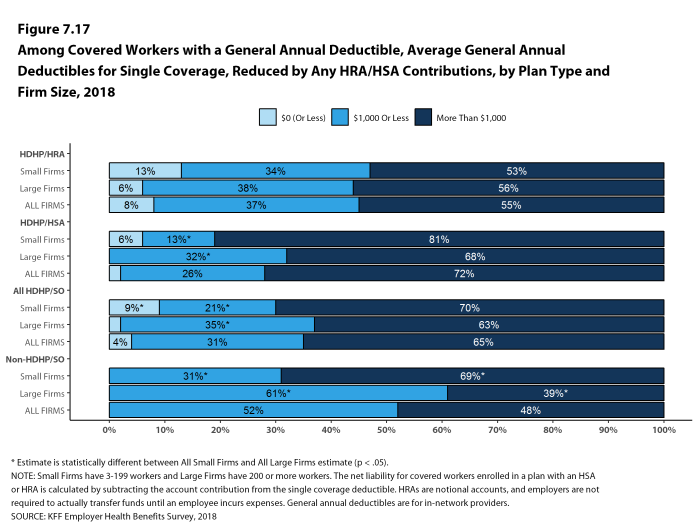

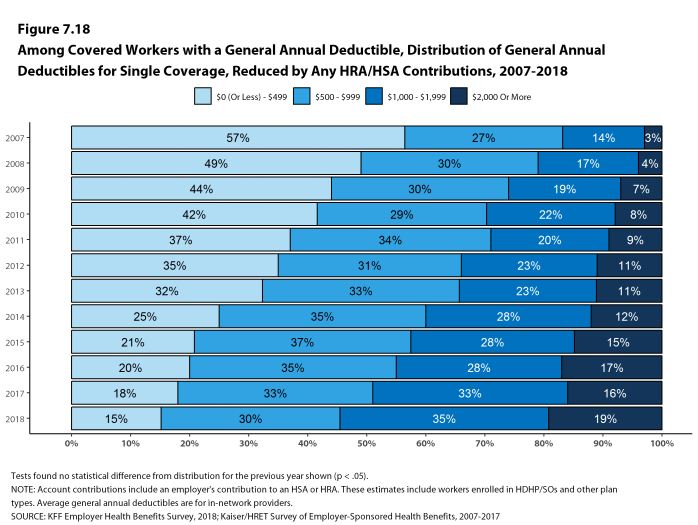

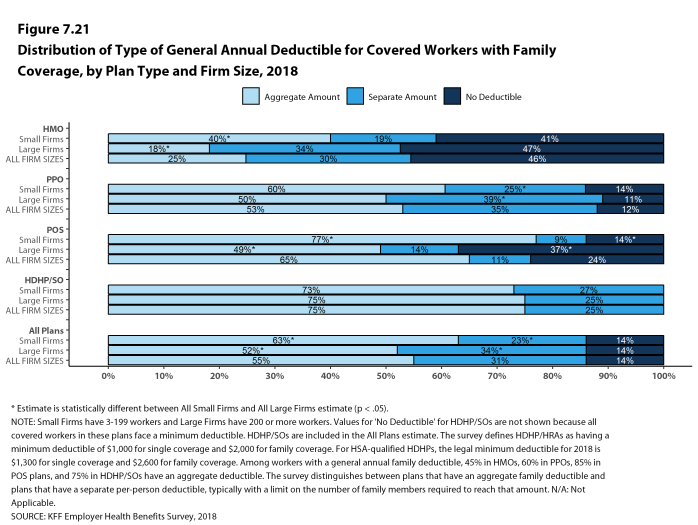

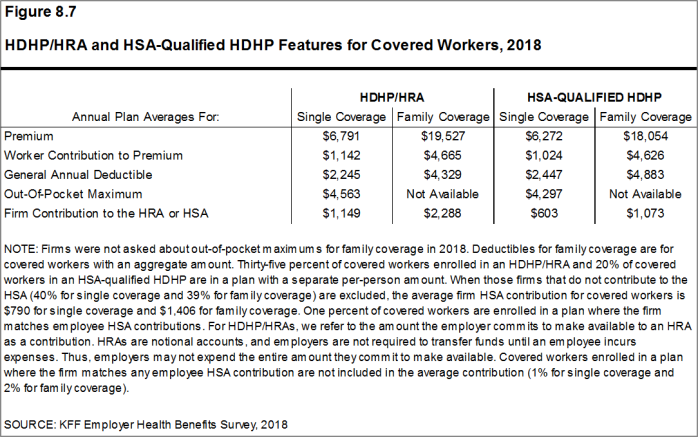

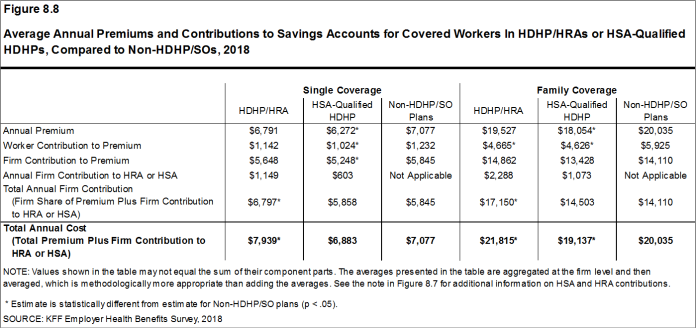

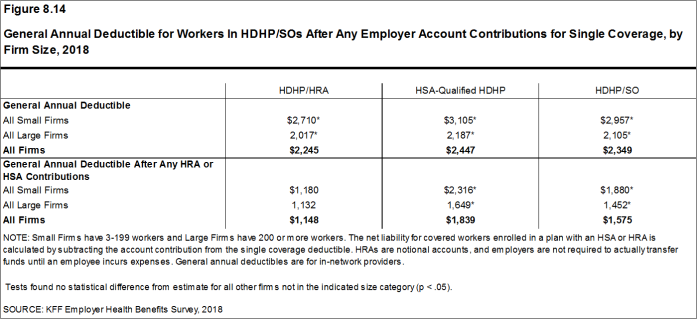

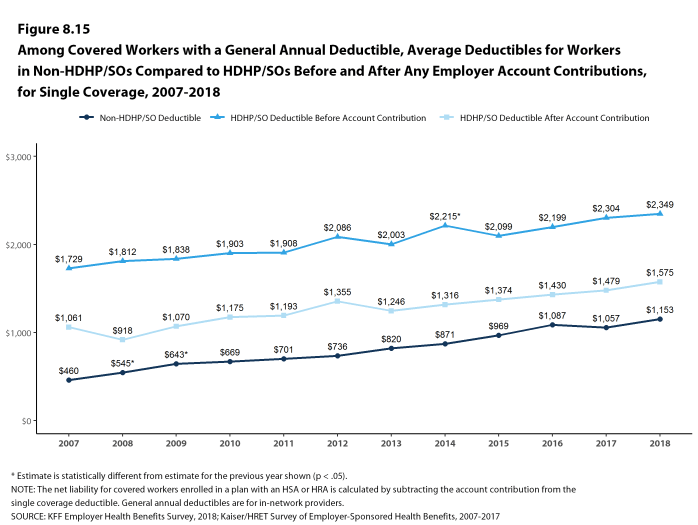

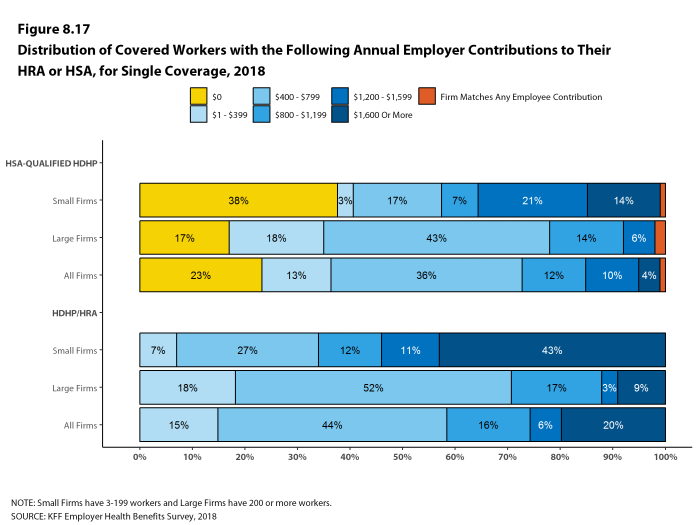

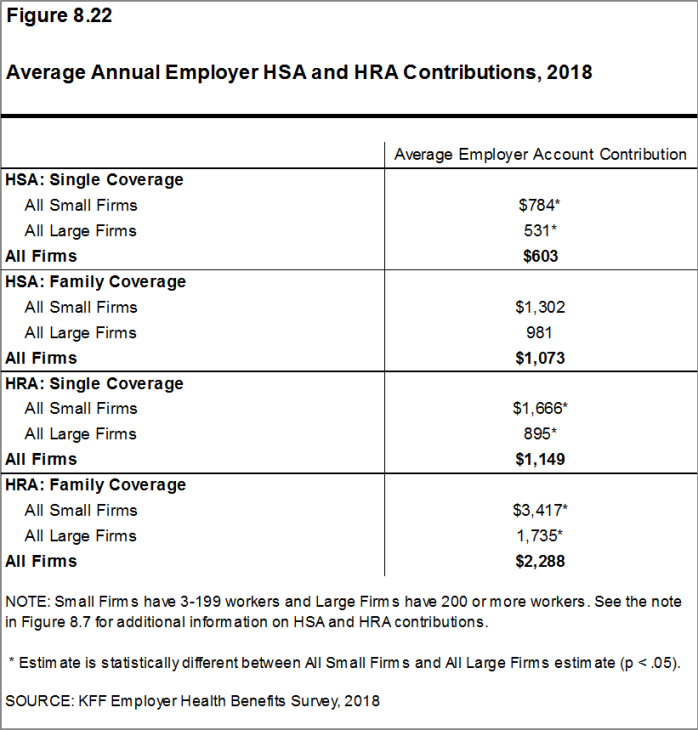

Deductibles have increased in recent years due to higher deductibles within plan types and higher enrollment in HDHP/SOs. While growing deductibles in PPOs and other plan types generally increase enrollee out-of-pocket liability, the shift in enrollment to HDHP/SOs does not necessarily do so because most HDHP/SO enrollees receive an account contribution from their employers. Eight percent of covered workers in an HDHP with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) and 2% of covered workers in a Health Savings Account (HSA)-qualified HDHP receive an account contribution for single coverage at least equal to their deductible, while another 37% of covered workers in an HDHP with an HRA and 26% of covered workers in an HSA-qualified HDHP receive account contributions that, if applied to their deductible, would reduce their deductible to less than $1,000.

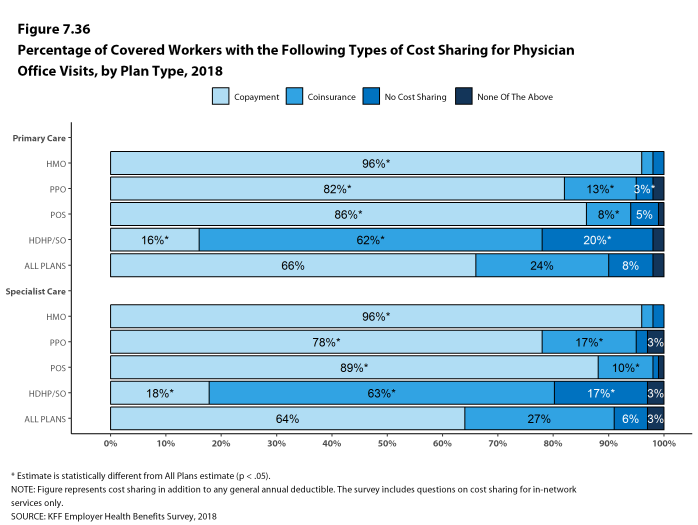

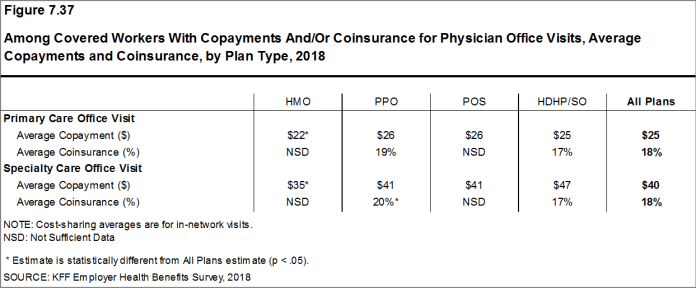

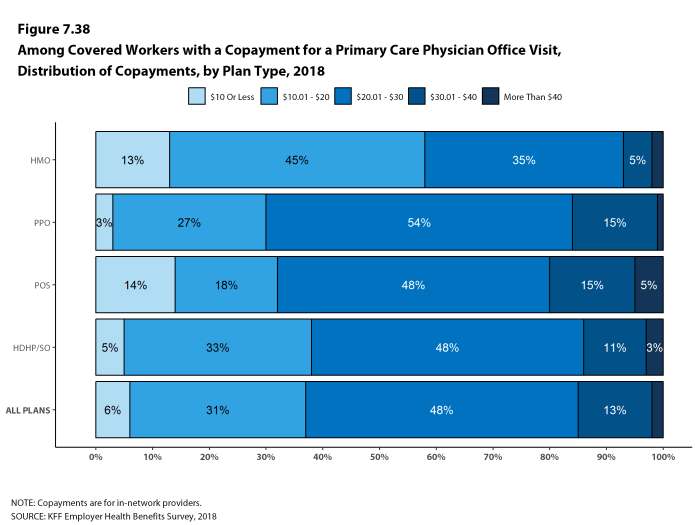

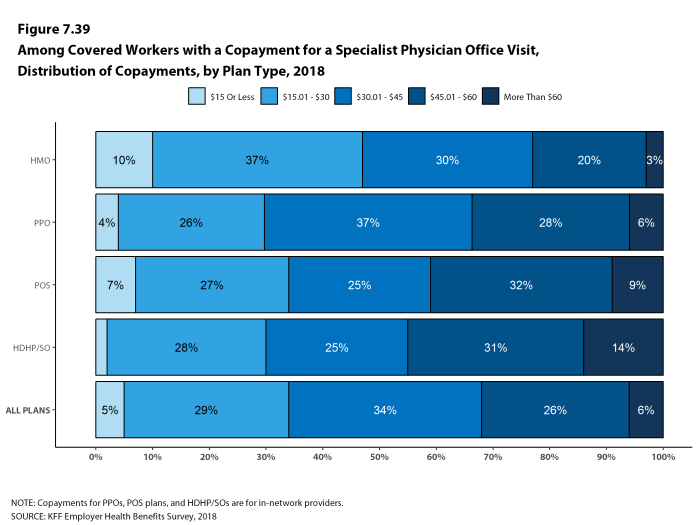

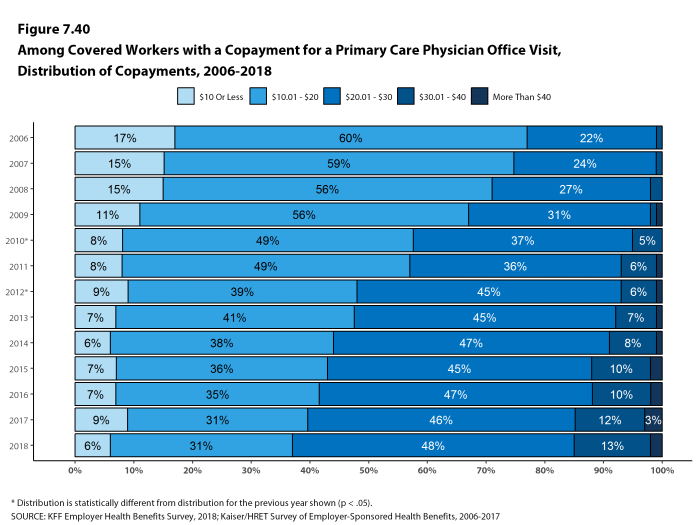

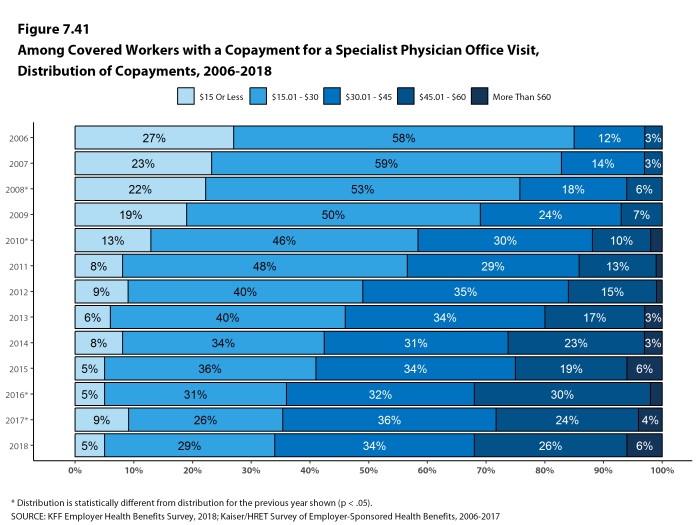

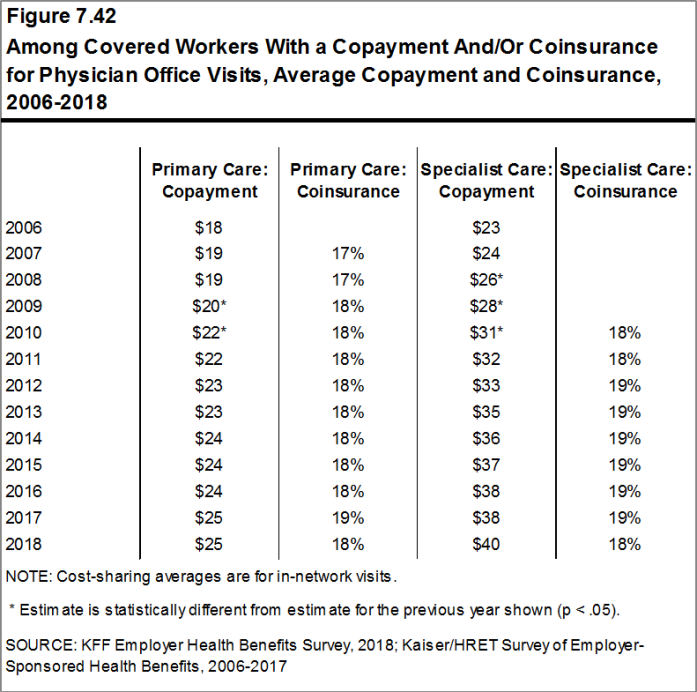

Whether they face a general annual deductible or not, a large share of covered workers also pay a portion of the cost when they visit an in-network physician. For primary care, 66% of covered workers have a copayment (a fixed dollar amount) when they visit a doctor and 24% have coinsurance (a percentage of the covered amount). For specialty care, 64% face a copayment and 27% face coinsurance. The average copayments are $25 for primary care and $40 for specialty care. The average coinsurance is 18% for both primary and specialty care. These amounts are similar to those in 2017.

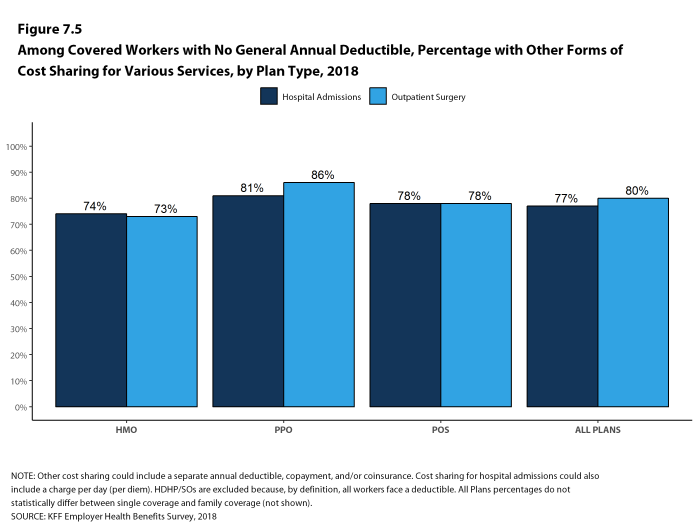

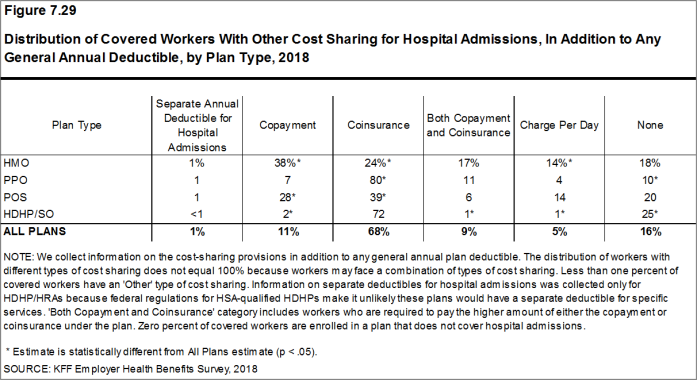

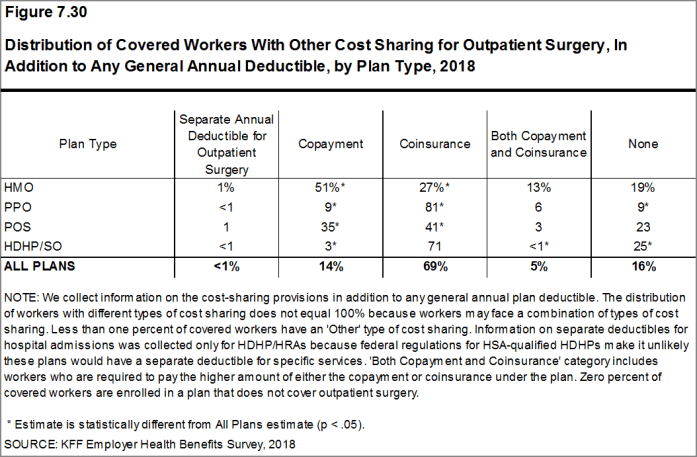

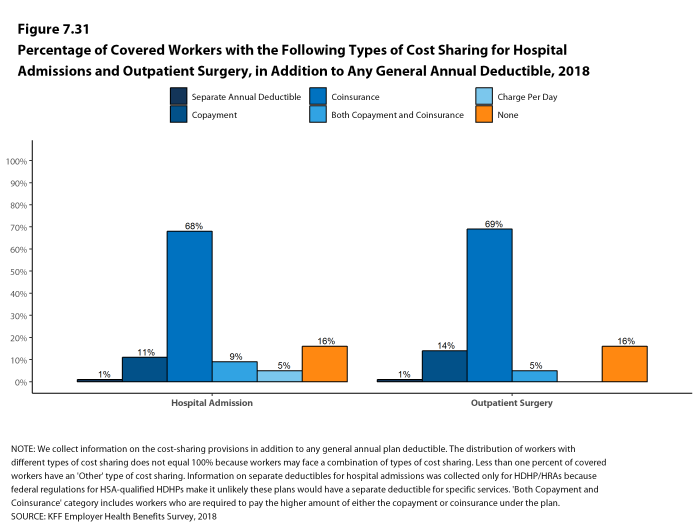

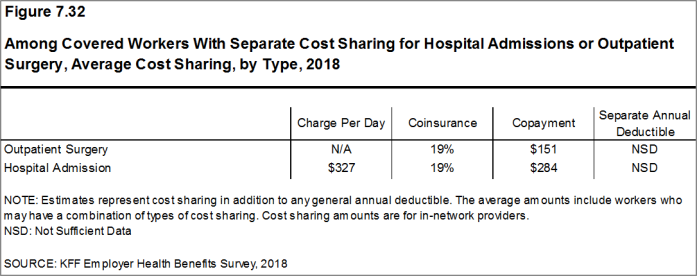

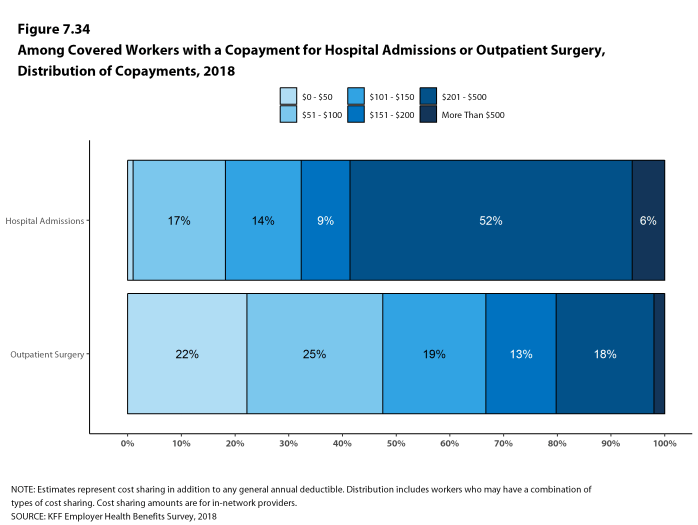

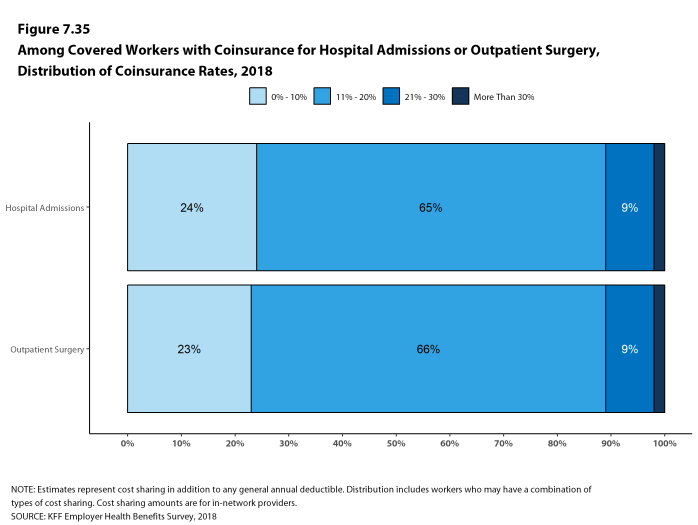

Most workers also face additional cost sharing for a hospital admission or outpatient surgery. After any general annual deductible is met, 68% of covered workers have coinsurance and 11% have a copayment for hospital admissions. The average coinsurance rate for a hospital admission is 19% and the average copayment is $284 per hospital admission. The cost-sharing provisions for outpatient surgery follow a similar pattern to those for hospital admissions.

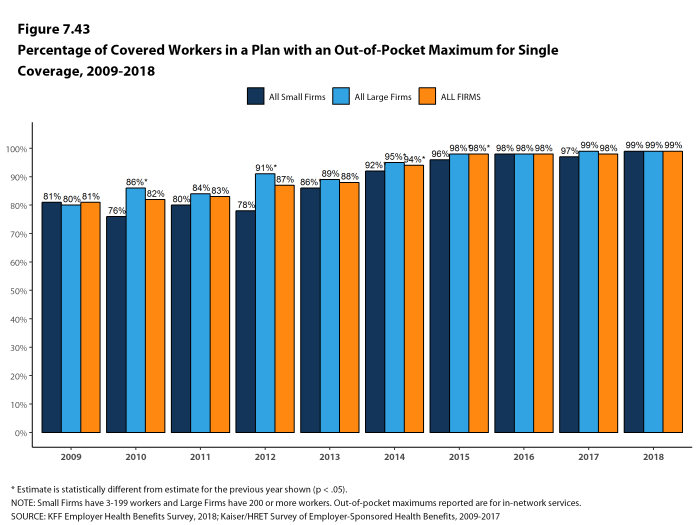

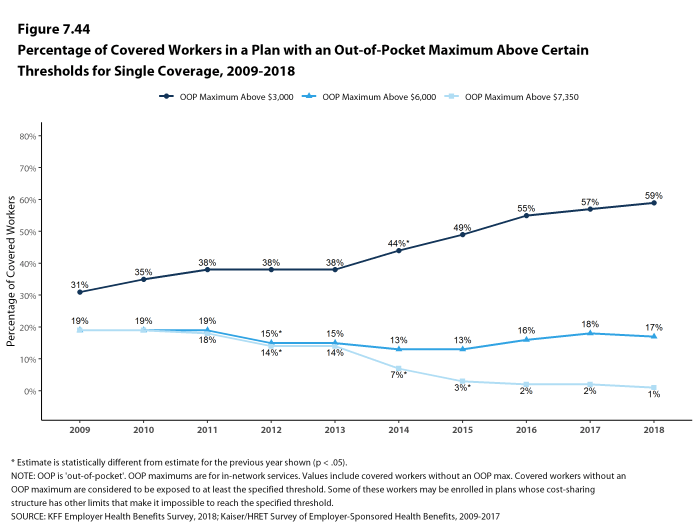

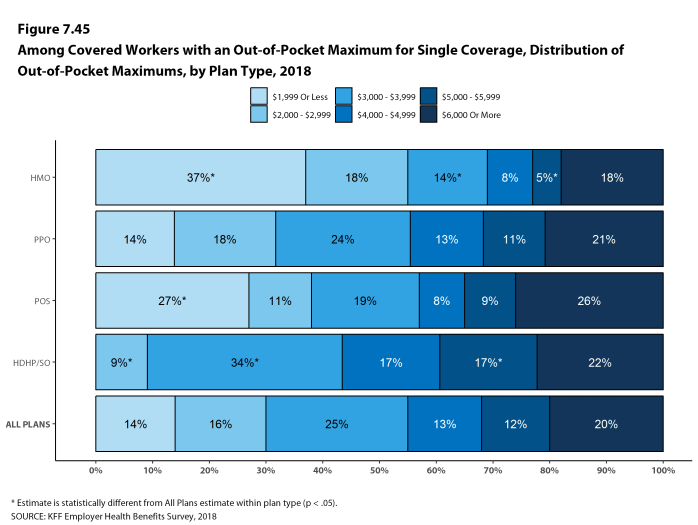

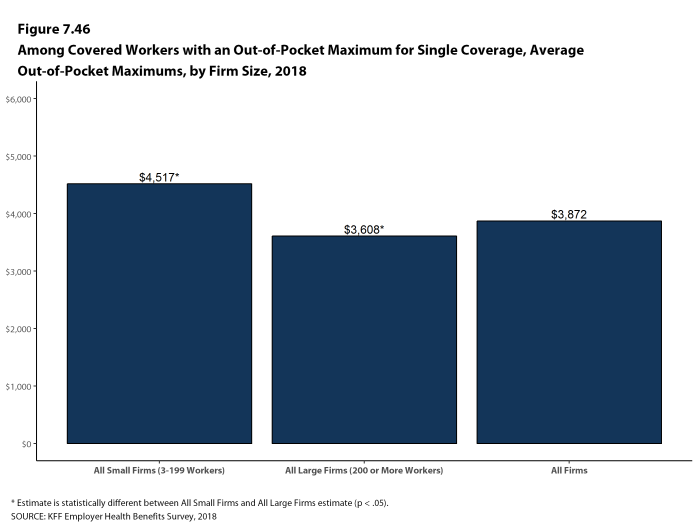

While almost all (99%) covered workers are in plans with a limit on in-network cost sharing (called an out-of-pocket maximum) for single coverage, there is considerable variation in the actual dollar limits. Fourteen percent of covered workers in plans with an out-of-pocket maximum for single coverage have an out-of-pocket maximum of less than $2,000, while 20% have an out-of-pocket maximum of $6,000 or more.

Figure F: Percentage of Covered Workers With Various Single Coverage General Annual Deductible Levels, 2013 and 2018

AVAILABILITY OF EMPLOYER-SPONSORED COVERAGE

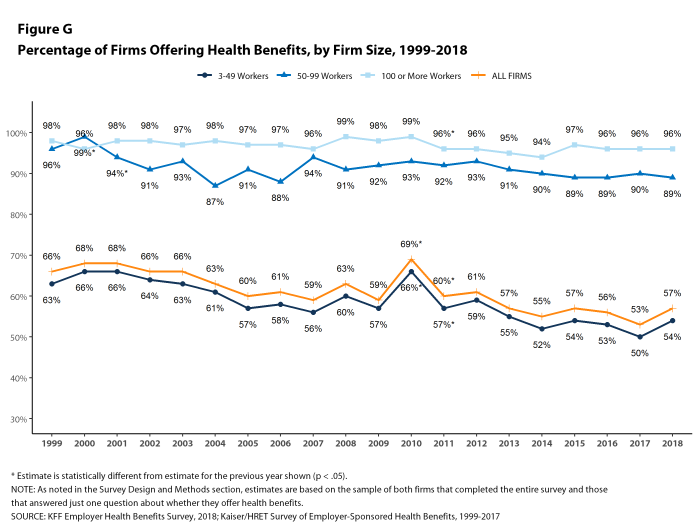

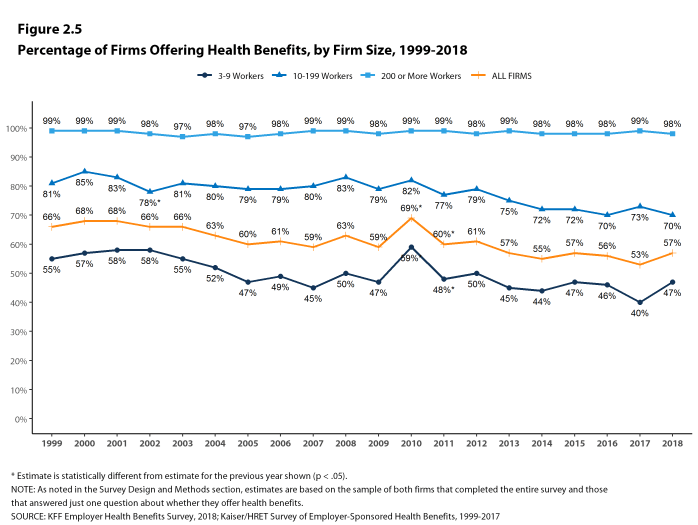

Fifty-seven percent of firms offer health benefits to at least some of their workers, similar to the percentage last year [Figure G]. The likelihood of offering health benefits differs significantly by firm size; for example, only 47% of firms with 3 to 9 workers offer coverage, while virtually all firms with 1,000 or more workers offer coverage.

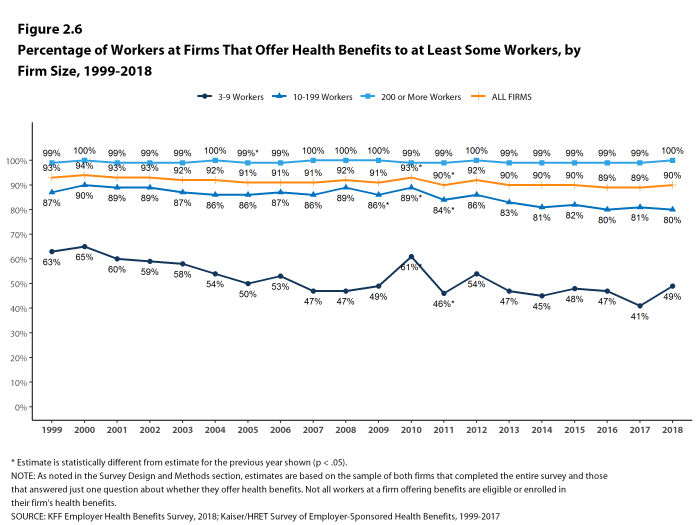

While the vast majority of firms are small, most workers work for large firms that offer coverage. In 2018, 90% of workers are employed by a firm that offers health benefits to at least some of its workers.

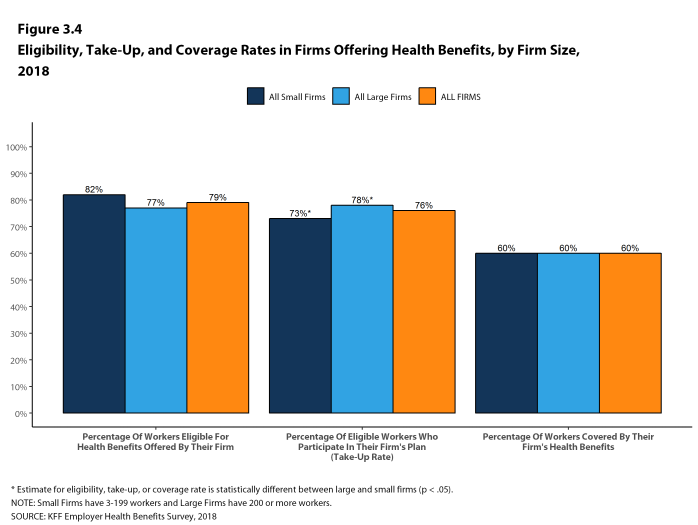

Even in firms that offer health benefits, some workers are not eligible to enroll (e.g., waiting periods or part-time or temporary work status) and others who are eligible choose not to enroll (e.g., they feel the coverage is too expensive or they are covered through another source). In firms that offer coverage, 79% of workers are eligible for the health benefits offered, and of those eligible, 76% take up the firm’s offer, resulting in 60% of workers in offering firms enrolling in coverage through their employer. All of these percentages are similar to 2017.

Looking across workers both in firms that offer and those that do not offer health benefits, 53% of workers are covered by health plans offered by their employer, similar to the percentage last year.

Coverage for Family Members. Among firms offering health benefits, 97% of small firms and 99% of large firms offer coverage to spouses of eligible workers. Similarly, 95% of small firms and 100% of large firms offering health benefits offer coverage to other dependents of their eligible workers, such as children.

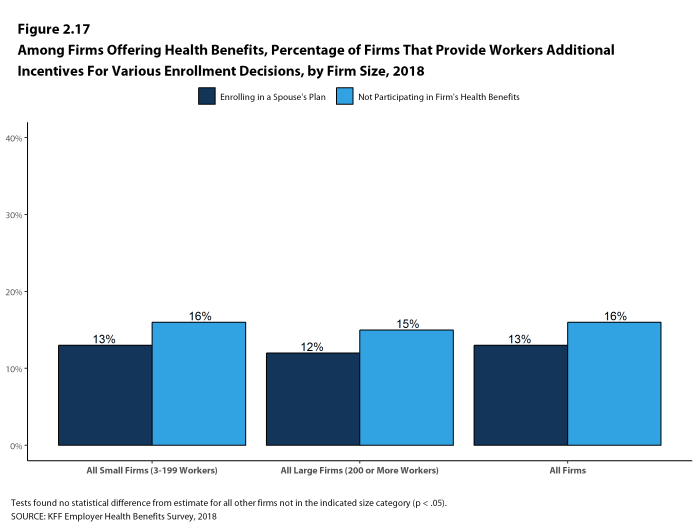

Inducements Not to Enroll. Among all firms that offer health benefits, 13% provide additional compensation or benefits to employees if they enroll in a spouse’s plan, and 16% provide additional compensation or benefits to employees if they do not participate in the firm’s health benefits.

Figure G: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

HEALTH AND WELLNESS PROGRAMS

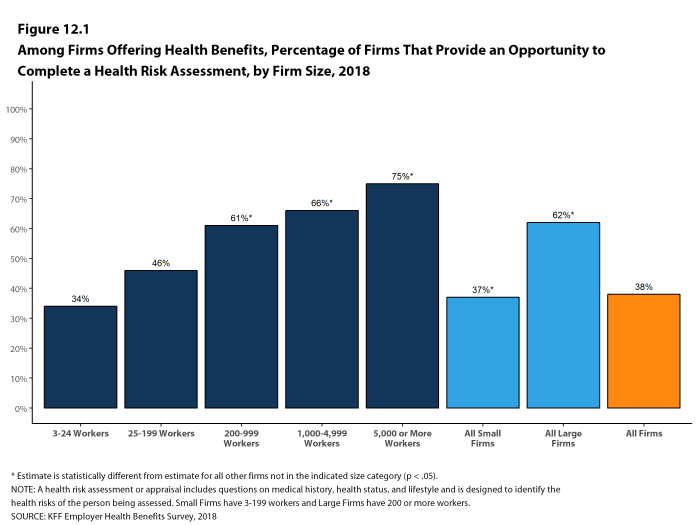

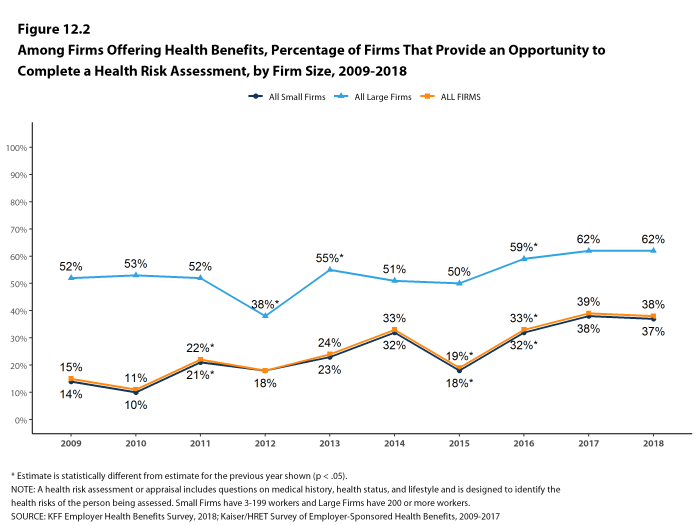

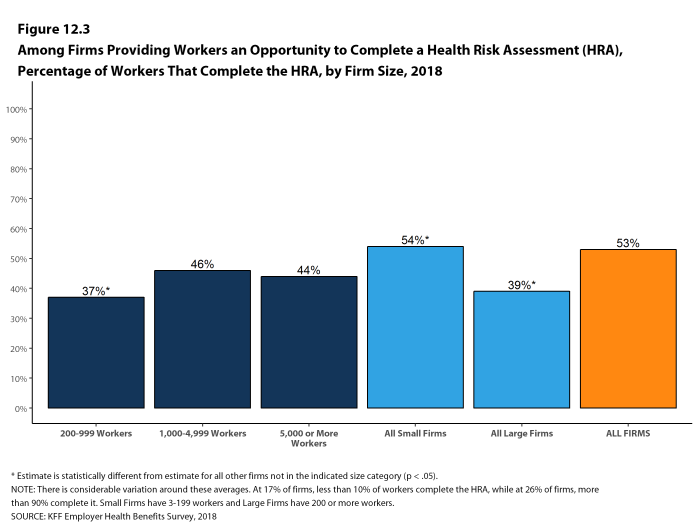

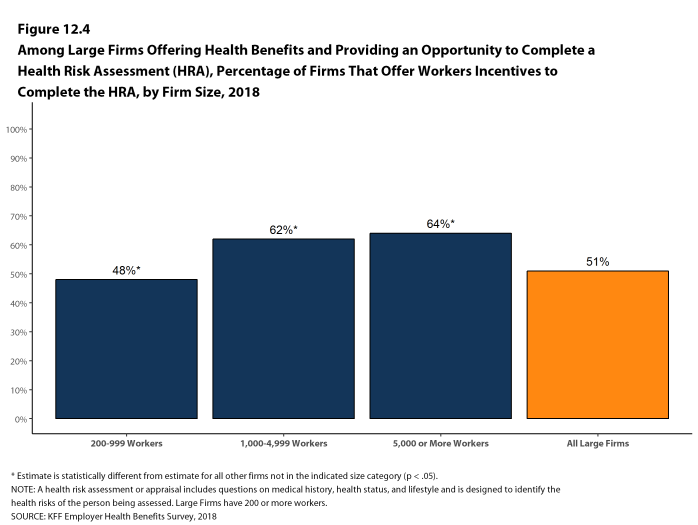

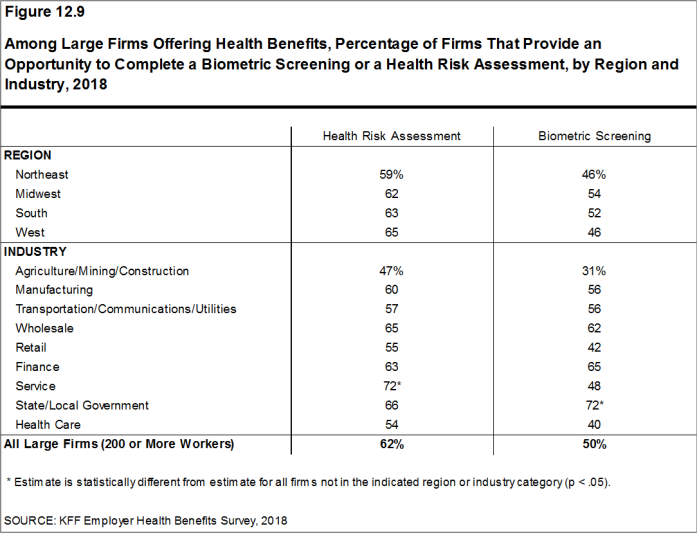

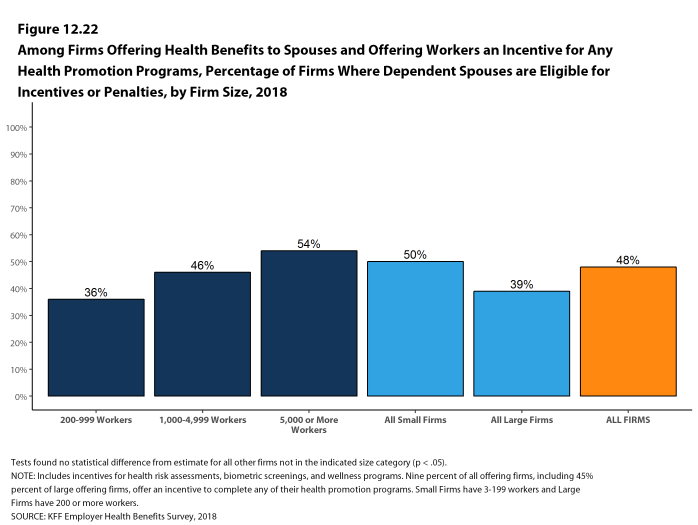

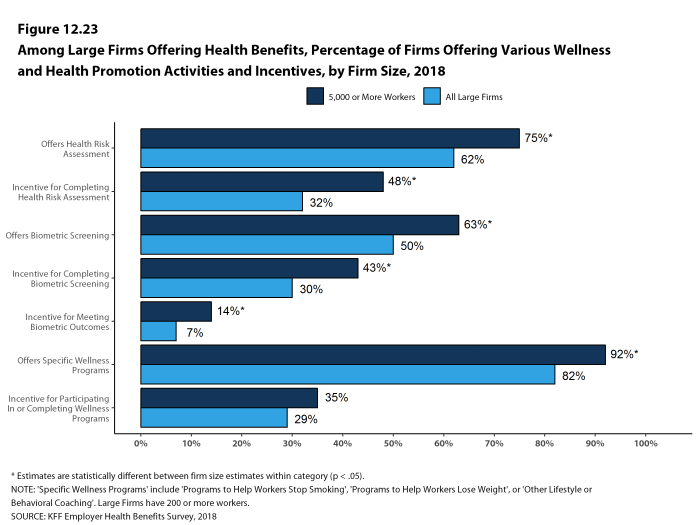

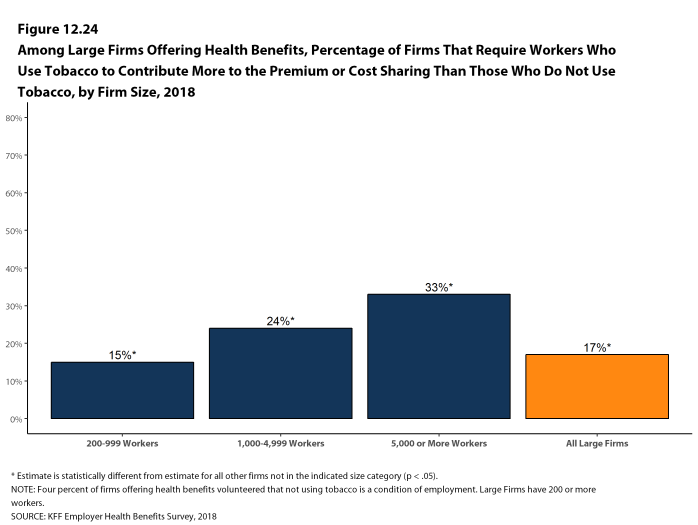

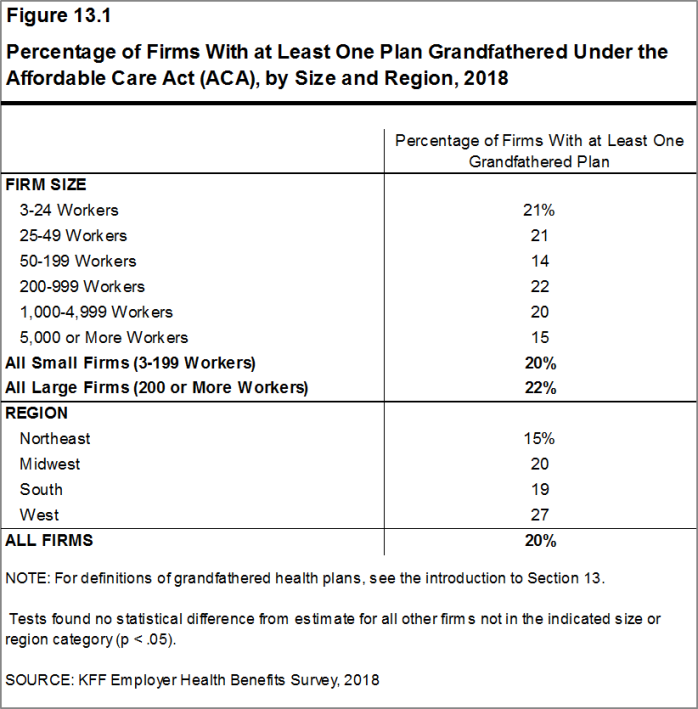

Firms continue to show considerable interest in programs that help workers identify health issues and manage chronic conditions, including health risk assessments, biometric screenings, and health promotion programs.

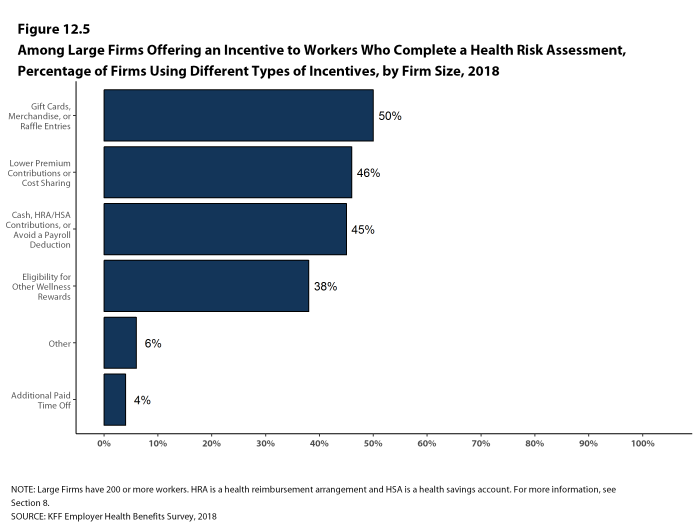

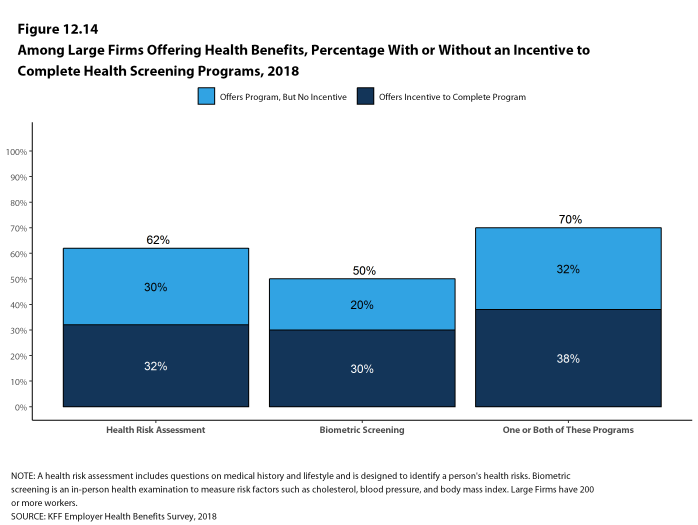

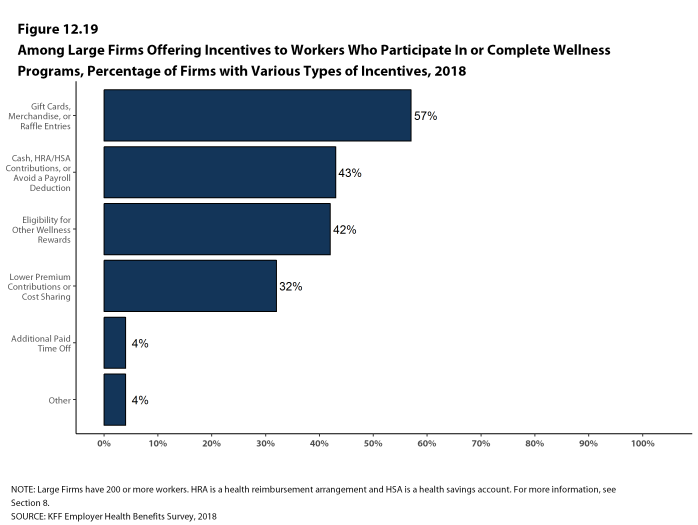

Health Risk Assessments. Among firms offering health benefits, 37% of small firms and 62% of large firms provide workers the opportunity to complete a health risk assessment. A health risk assessment includes questions about a person’s medical history, health status, and lifestyle. Fifty-one percent of large firms with a health risk assessment program offer an incentive to encourage workers to complete the assessment. Incentives may include: gift cards, merchandise or similar rewards; lower premium contributions or cost sharing; and financial rewards, such as cash, contributions to health-related savings accounts, or avoiding a payroll fee.

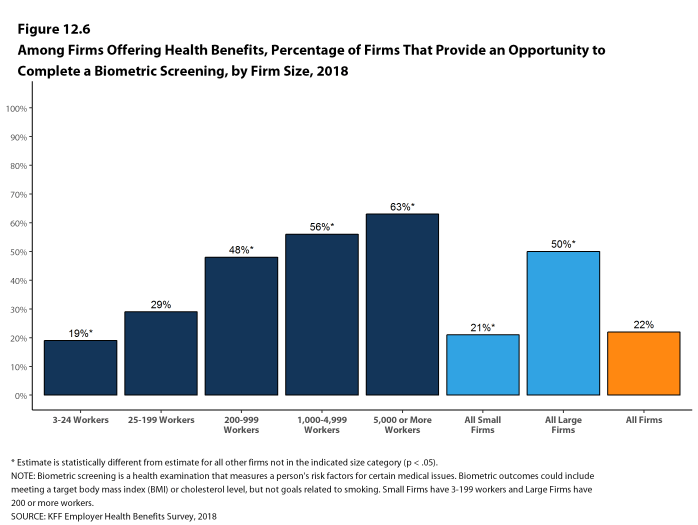

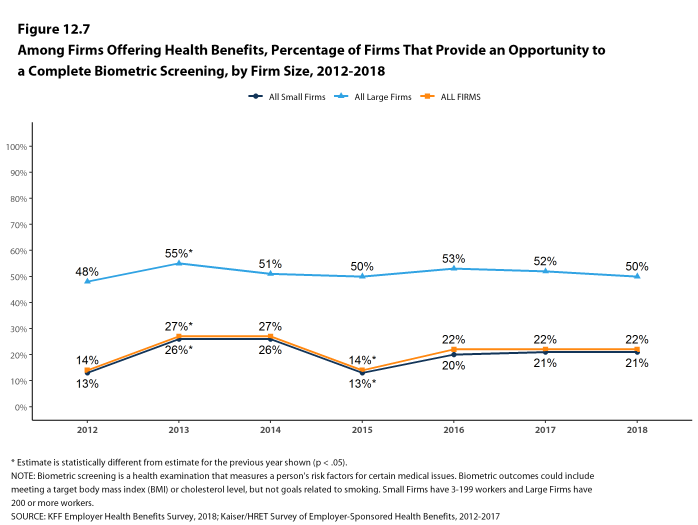

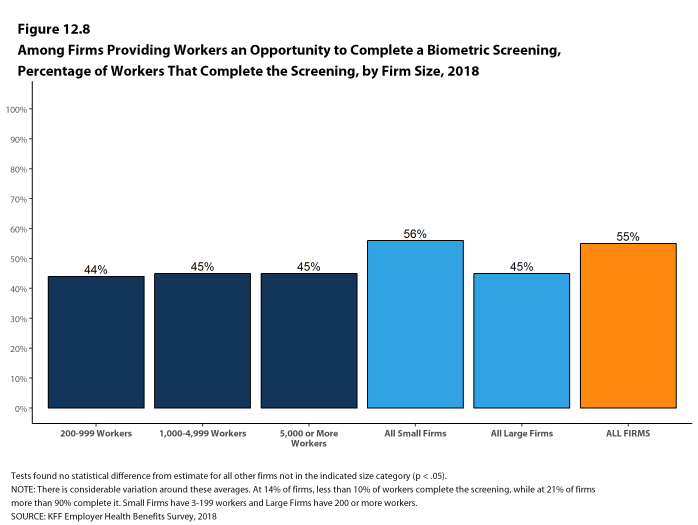

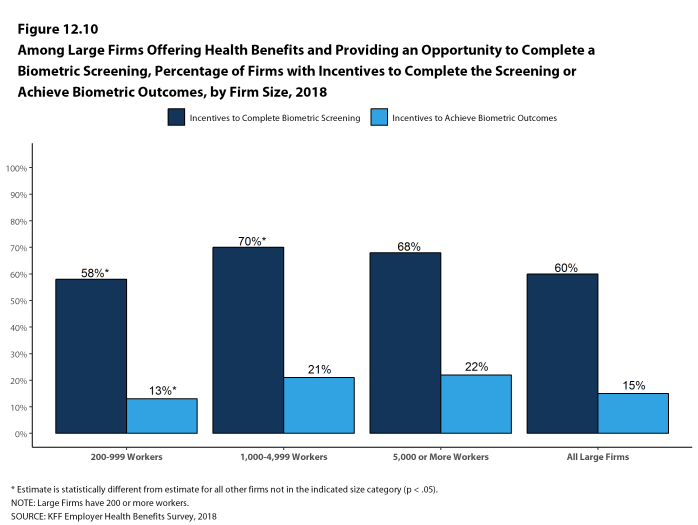

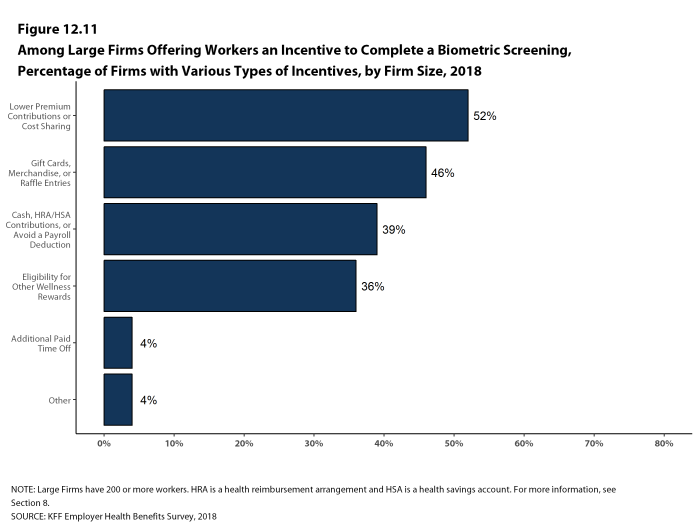

Biometric Screenings. Among firms offering health benefits, 21% of small firms and 50% of large firms provide workers the opportunity to complete a biometric screening. A biometric screening is an in-person health examination that measures a person’s risk factors, such as body mass index (BMI), cholesterol, blood pressure, stress, and nutrition. We do not consider preventive health services covered by the plan to be biometric screening. Sixty percent of large firms with biometric screening programs offer workers an incentive to complete the screening, similar to the incentives for completing health risk assessments.

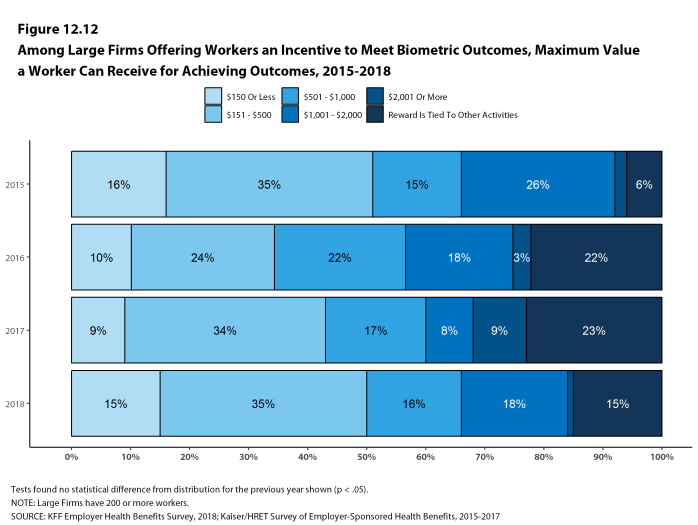

Additionally, among large firms with biometric screening programs, 15% reward or penalize workers based on achieving specified biometric outcomes (such as meeting a target BMI). The size of these incentives varies considerably: among large firms offering a reward or penalty for meeting biometric outcomes, the maximum reward is valued at $150 or less in 15% of firms and more than $1,000 in 19% of firms.

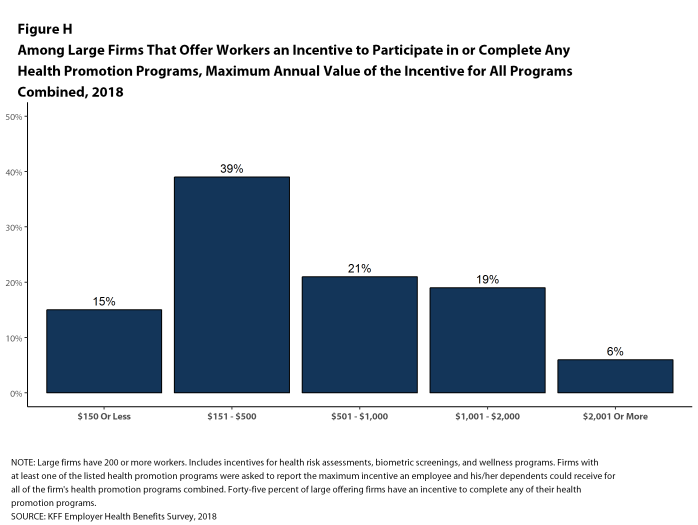

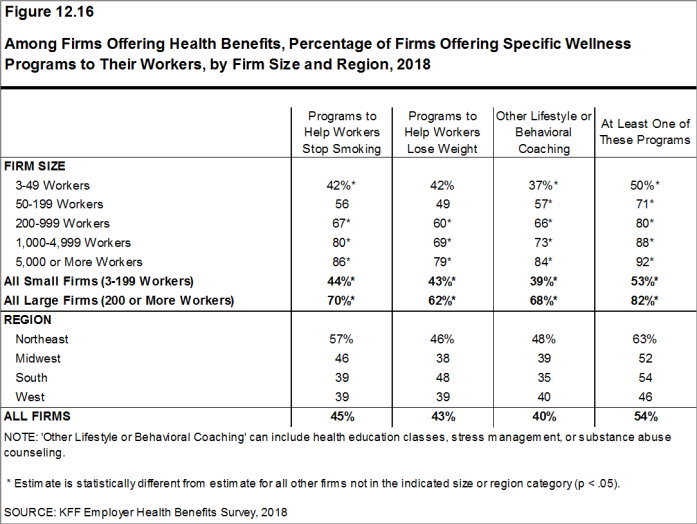

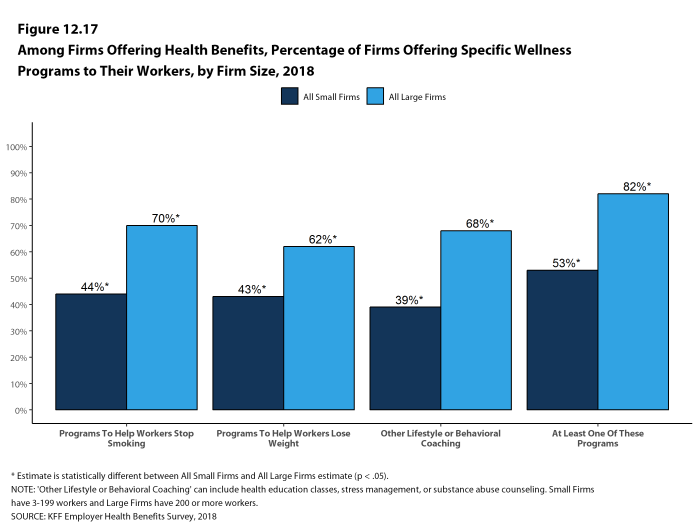

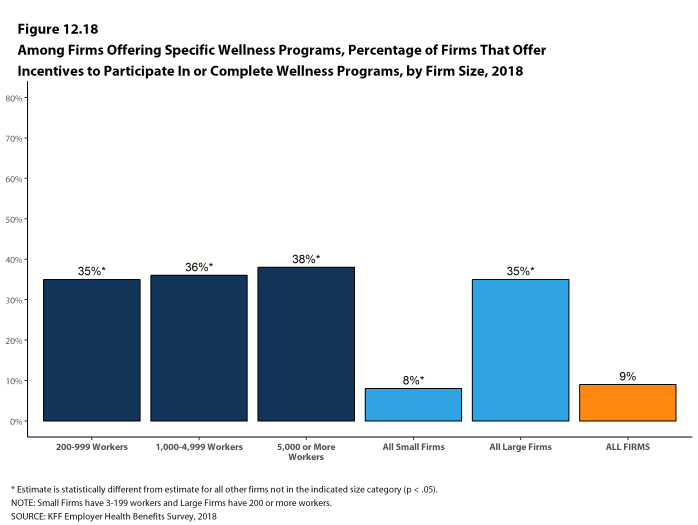

Health and Wellness Promotion Programs. A majority of firms offering health benefits offer programs to help workers identify health risks and unhealthy behaviors, and improve their lifestyles. Fifty-three percent of small firms and 82% of large firms offer a program in at least one of these areas: smoking cessation; weight management; and behavioral or lifestyle coaching. Among large firms offering at least one of these programs, 35% offer workers an incentive to participate in or complete the program.

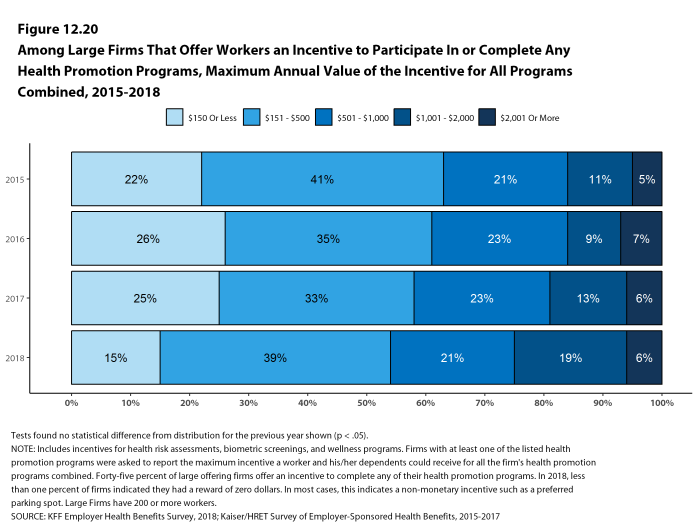

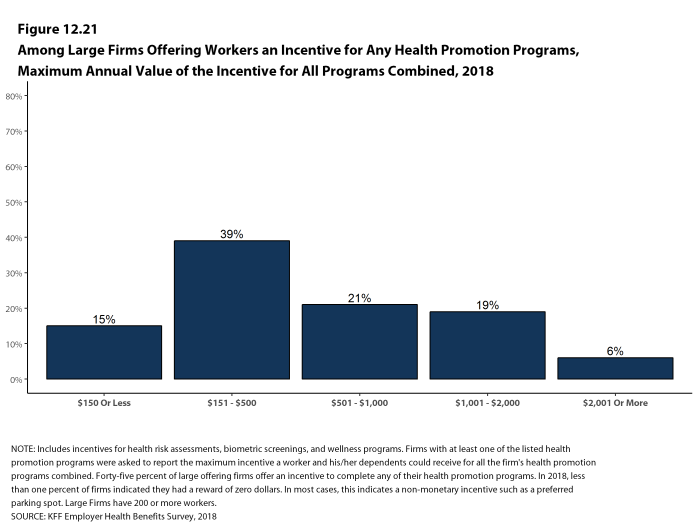

As health screenings and wellness programs have become more complex, incentives have become more sophisticated and may involve participating in or meeting goals in different programs (e.g., completing an assessment and participating in a health promotion activity). To better understand the combined incentives or penalties facing program participants, we asked large firms that had any incentives for health risk assessments, biometric screenings, or the specified health and wellness promotion programs what the maximum incentive was for a worker for all of their programs combined. Among large firms with any type of incentive, 15% have a maximum incentive of 150 or less; 39% have a maximum incentive between $151 and $500; 21% have a maximum incentive between $501 and $1,000; 19% have a maximum incentive between $1,001 and $2,000; and 6% have a maximum incentive of more than $2,000 [Figure H].

Figure H: Among Large Firms That Offer Workers an Incentive to Participate In or Complete Any Health Promotion Programs, Maximum Annual Value of the Incentive for All Programs Combined, 2018

SITES OF CARE

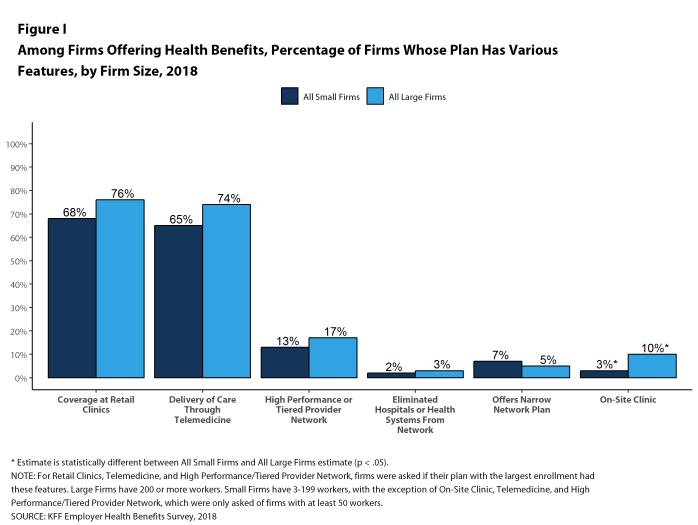

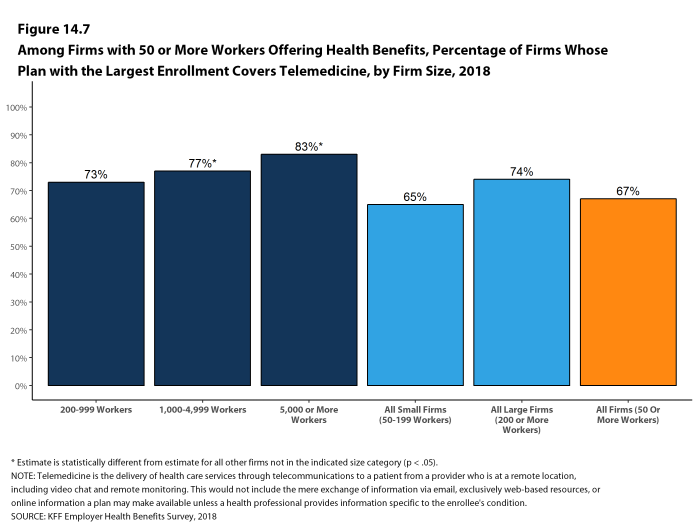

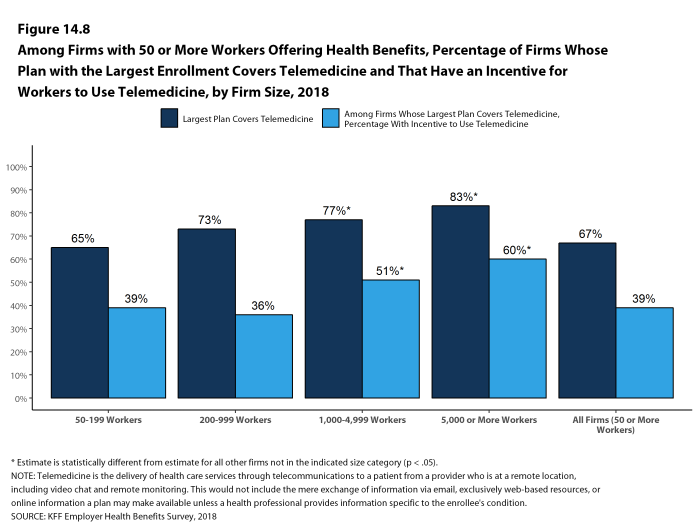

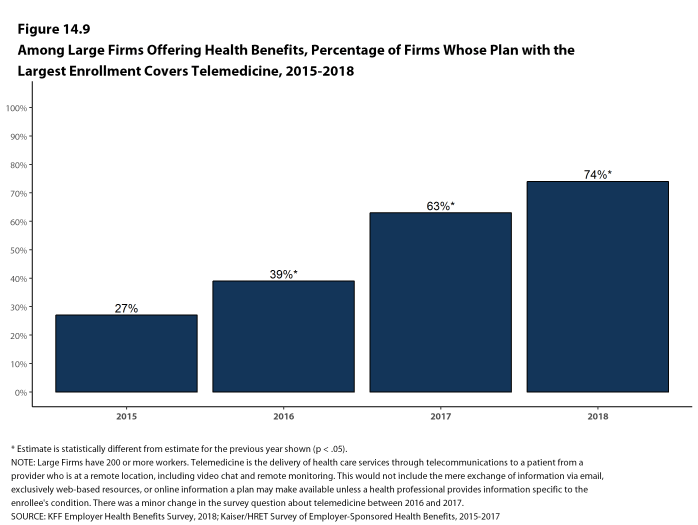

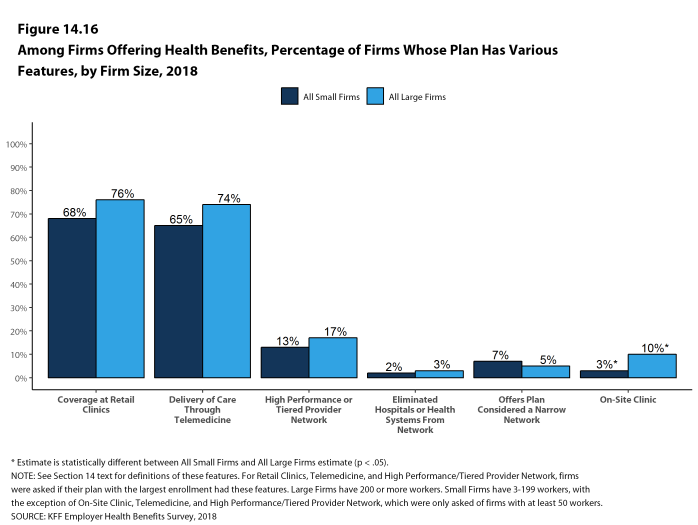

Telemedicine. Seventy-four percent of large firms offering health benefits cover the provision of health care services through telemedicine in their largest health plan [Figure I]. Telemedicine is the delivery of health care services through telecommunications to a patient from a provider who is at a remote location, including video chat and remote monitoring. Firms with 1,000 or more workers are more likely to cover services provided through telemedicine than smaller firms.

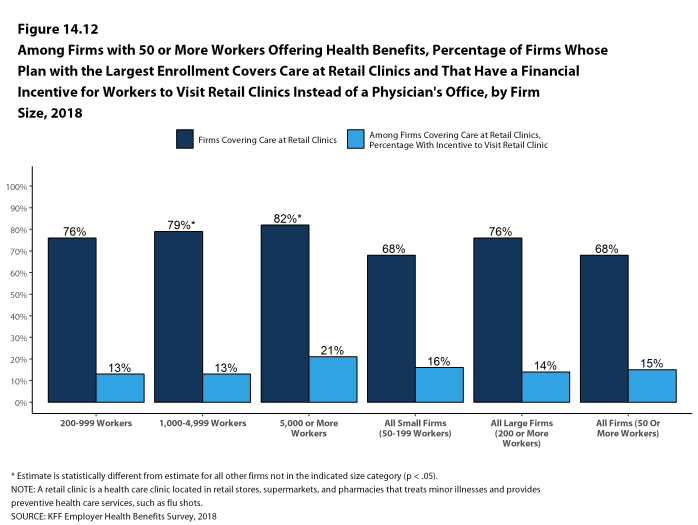

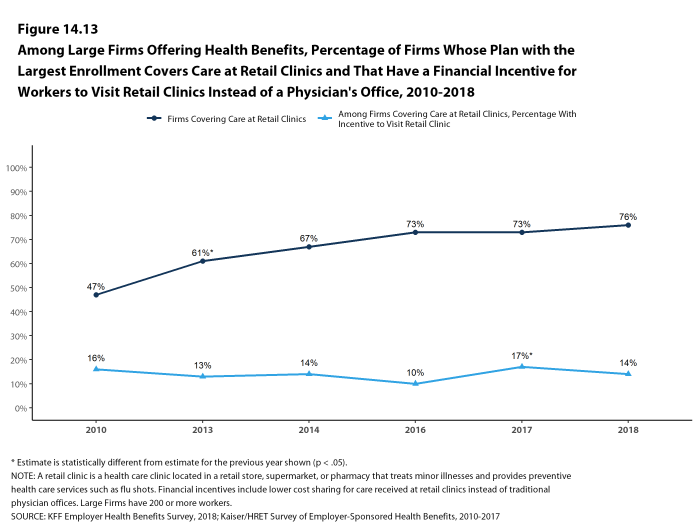

Retail Health Clinics. Seventy-six percent of large firms offering health benefits cover health care services received in retail clinics, such as those located in pharmacies, supermarkets and retail stores, in their largest health plan [Figure I]. These clinics are often staffed by nurse practitioners or physician assistants and treat minor illnesses and provide preventive services.

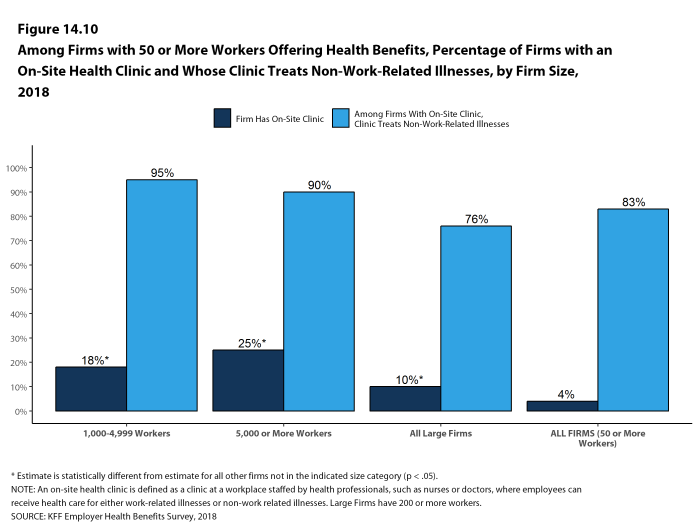

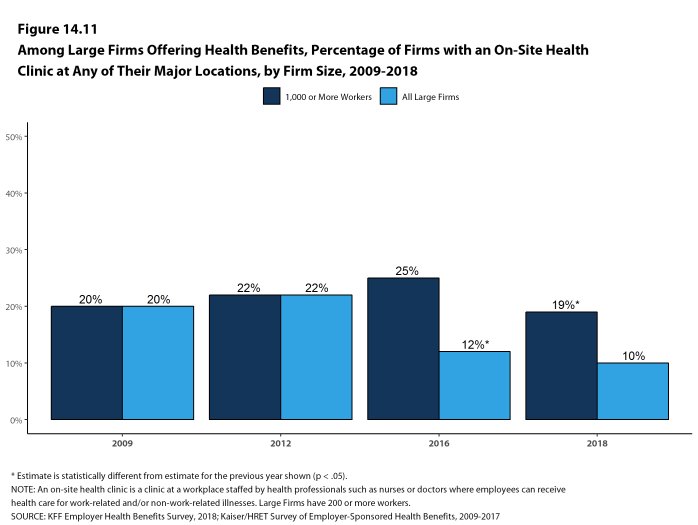

On-Site Health Clinics Only 10% of large firms offering health benefits have an on-site health clinic for their employees at one or more of their major locations. A large share of these firms report that employees can receive treatment for non-work-related illnesses at their on-site clinics.

PROVIDER NETWORKS

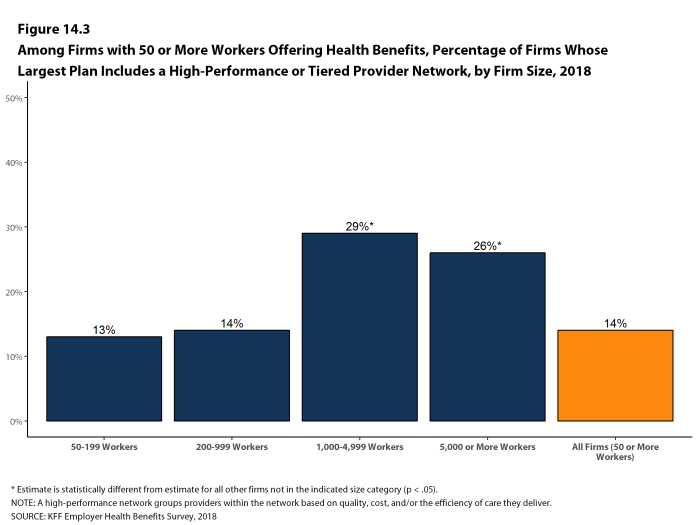

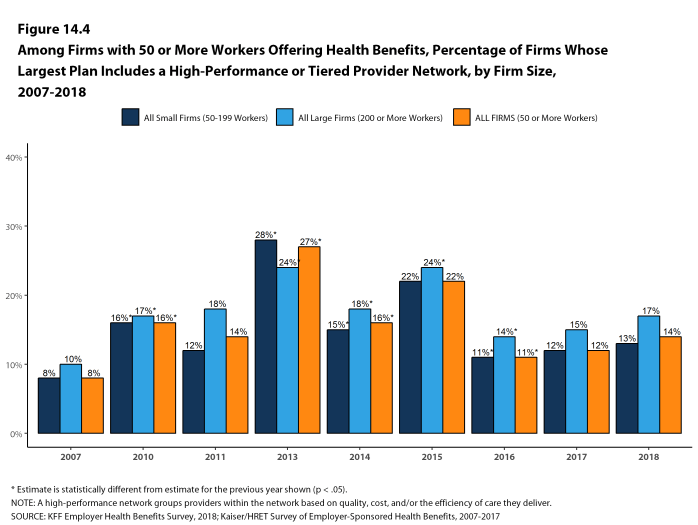

High Performance or Tiered Networks. Seventeen percent of large firms that offer health benefits include a high-performance or tiered provider network in their health plan with the largest enrollment, a similar percentage to last year [Figure I]. These arrangements identify providers that are more efficient and generally provide financial or other incentives for enrollees to use the selected providers. Firms with 1,000 or more workers are more likely than smaller firms to incorporate a high-performance or tiered network into their largest plan.

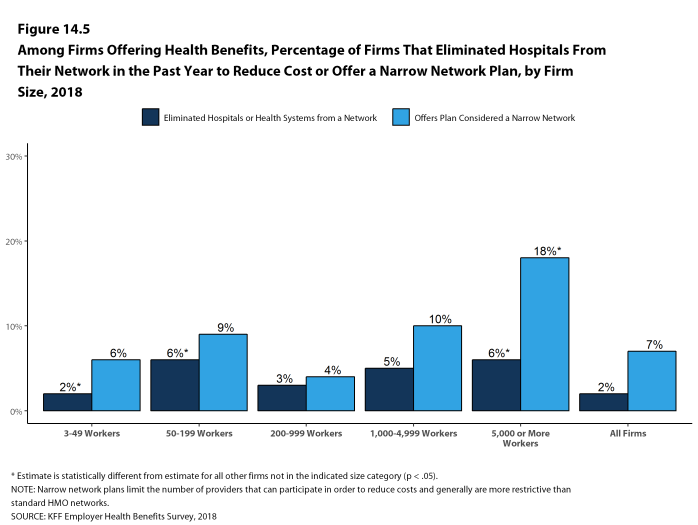

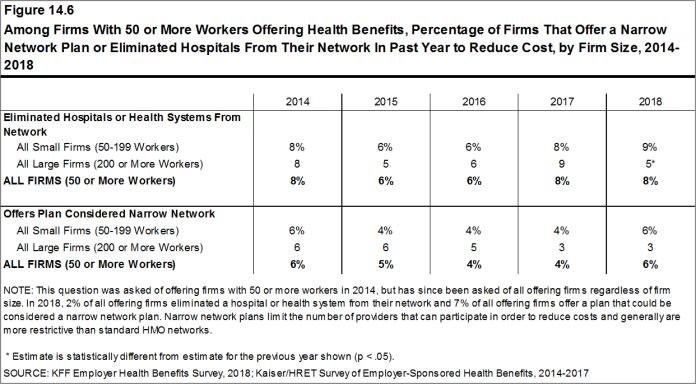

Narrow Networks. Five percent of large firms offering health benefits offer a plan they consider to be a narrow network plan, similar to the percentages for the past two years [Figure I]. Narrow network plans limit the number of providers who can participate in order to reduce costs, and are generally more restrictive than standard HMO networks. Firms with 5,000 or more workers offering health benefits are more likely than firms of other sizes to offer at least one plan with a narrow network.

Eliminated Hospitals or Health Systems. Only 3% of large firms report that they or their health plan eliminated a hospital or health system in the past year in order to reduce the costs of their plan, similar to the percentage reported last year [Figure I]. Firms with 5,000 or more workers offering health benefits are more likely to say that either they or their insurer eliminated a hospital or health system from a provider network to reduce costs than firms of other sizes.

Figure I: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms Whose Plan Has Various Features, by Firm Size, 2018

REPEAL OF TAX PENALTY FOR INDIVIDUALS WITHOUT HEALTH INSURANCE

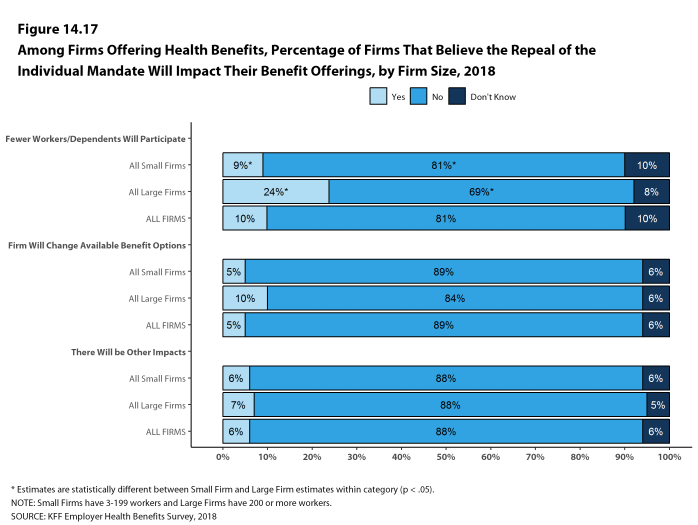

The 2017 tax law eliminated the tax penalty for people who do not have health insurance (sometimes called the ‘individual mandate’) beginning in 2019. Nine percent of small firms and 24% of large firms report that they expect fewer employees and dependents to participate in their health plans as result of the change. Additionally, 5% of small firms and 10% of large firms said that they expect to change the benefit options for at least some employees as a result of the change.

CONCLUSION

This year continues a period of stability and relatively low cost growth for employer-provided coverage. While premium growth continues to exceed increases in earnings and inflation, the differences are small compared to recent periods which, along with low underlying health spending growth, may help explain the apparent reluctance of employers and plans to make many changes in the market [Figure C].

The one area where we have seen change is higher deductibles – the average deductible for single coverage among all workers increased 53% since 2013, driven in part by a 50% increase in HDHP/SO enrollment over that period. Higher deductibles have helped to keep premium increases relatively low, but it is unclear how long that trend will continue. Given the importance of health benefits to workers and prospective workers, employers may find it increasingly difficult to impose higher cost sharing in what is essentially a full employment economy. The growth in HDHP/SO enrollment has stalled over the past three years, which may be a sign of employer reluctance to rock the benefit boat for their workers. If underlying health care prices and service use begin to grow as part of stronger economic growth, employer and health plans may need to look for tools other than higher cost sharing to address the pressures that would lead to higher premium growth.

METHODOLOGY

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey reports findings from a telephone survey of 2,160 randomly selected non-federal public and private employers with three or more workers. Researchers at NORC at the University of Chicago and the Kaiser Family Foundation designed and analyzed the survey. National Research, LLC conducted the fieldwork between January and July 2018. In 2018, the overall response rate is 32%, which includes firms that offer and do not offer health benefits. Among firms that offer health benefits, the survey’s response rate is also 32%. To improve estimates for small firms, the 2018 survey had a significantly larger sample than in previous years; the increased sample size led to both more firms completing the survey and a lower response rate than in years past. Unless otherwise noted, differences referred to in the text and figures use the 0.05 confidence level as the threshold for significance. Values below 3% are not shown on graphical figures to improve the readability of those graphs.

For more information on the survey methodology, please visit the Survey Design and Methods section at http://ehbs.kff.org/.

Filling the need for trusted information on national health issues, the Kaiser Family Foundation is a nonprofit organization based in San Francisco, California.

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. The uninsured: A primer – Key facts about health insurance and the uninsured in the era of health reform: Supplemental Tables. Washington (DC): The Commission; 2017 Dec (cited 2018 Jul 23). https://files.kff.org/attachment/Supplemental-Tables-The-Uninsured-A-Primer-Key-Facts-about-Health-Insurance-and-the-Uninsured-Under-the-Affordable-Care-Act. See Table 1: 271.1 million nonelderly people, 56.2% of whom are covered by employer-sponsored insurance.↩

- Inflation values are not seasonally adjusted. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers (April to April): Department of Labor; 2018 (cited 2018 Jul 20). https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0. Wage data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and based on the change in total average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees. Employment, hours, and earnings from the Current Employment Statistics survey: Department of Labor; 2018 (cited 2018 July 20). https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES0500000008↩

- This threshold is based on the twenty-fifth percentile of workers’ earnings, using data for 2017 (April to April). Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2017 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates: United States. Washington (DC): BLS; (last modified 2018 Apr 27; cited 2018 Jul 23). Available from: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm↩

Survey Design And Methods

The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) has conducted this annual survey of employer-sponsored health benefits since 1999. KFF works with NORC at the University of Chicago (NORC) and National Research, LLC (NR) to field and analyze the survey. From January to July 2018, NR completed telephone interviews with human resource and benefits managers at 2,160 firms.

SURVEY TOPICS

The survey includes questions on the cost of health insurance, health benefit offer rates, coverage, eligibility, plan type enrollment, premium contributions, employee cost sharing, prescription drug benefits, retiree health benefits, and wellness benefits.

Firms that offer health benefits are asked about the plan attributes of their largest health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), point-of-service (POS) plan, and high-deductible health plan with a savings option (HDHP/SO).4 We treat exclusive provider organizations (EPOs) and HMOs as one plan type and report the information under the banner of “HMO”. Since 2013, plan information for conventional (or indemnity) plans was collected within the PPO battery. Less than one percent of firms that completed the PPO section had more enrollment in a conventional plan than in a PPO plan. Firms with 50 or more workers were asked: “Does your firm offer health benefits for current employees through a private or corporate exchange?” Employers were still asked for plan information about their HMO, PPO, POS and HDHP/SO plan regardless of whether they purchased health benefits through a private exchange or not.

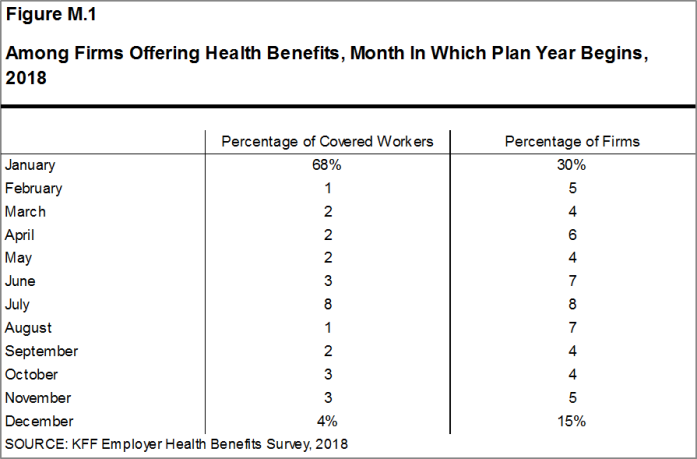

Firms are asked about the attributes of their current plans during the interview. While the survey’s fielding period begins in January, many respondents may have a plan whose 2018 plan year lags behind the calendar year [Figure M.1]. In some cases, plans may report the attributes of their 2017 plans and some plan attributes (such as HSA deductible limits) may not meet the calendar year regulatory requirements.

Figure M.1: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Month In Which Plan Year Begins, 2018

SAMPLE DESIGN

The universe is defined by the U.S. Census’ 2014 Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) for private firms and the 2012 Census of Governments (COG) for non-federal public employers. At the time of the sample design (December 2017), these data represented the most current information on the number of public and private firms nationwide with three or more workers. As in the past, the post-stratification is based on the most up-to-date Census data available (the 2015 SUSB). We determine the sample size based on the number of firms needed to ensure a target number of completes in six size categories.

We attempted to repeat interviews with prior years’ survey respondents (with at least ten employees) who participated in either the 2016 or the 2017 survey, or both. Firms with 3-9 employees are not included in the panel to minimize the impact of panel effects. As a result, 1,529 of the 2,160 firms that completed the full survey also participated in either the 2016 or 2017 surveys, or both. In total, 150 firms participated in 2016, 416 firms participated in 2017, and 963 firms participated in both 2016 and 2017. In addition non-panel firms are randomly selected to participate in the survey.

Since 2010, the sample has been drawn from a Research Now SSI list (based on an original Dun and Bradstreet list) of the nation’s private employers and the COG for public employers. To increase precision, we stratified the sample by ten industry categories and six size categories. The federal government and business with fewer than three employees are not included in the sample frame. Education is a separate sampling category for the purposes of sampling, rather than a subgroup of the Service category. Education is controlled for during post-stratification, and adjusting the sampling frame to also control for Education allows for a more accurate representation of both the Education and Service industries. For information on changes to the sampling methods over time, please consult the Survey Design and Methods Sections of prior Employer Health Benefits Surveys (https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/employer-health-benefits-annual-survey-archives/).

RESPONSE RATE

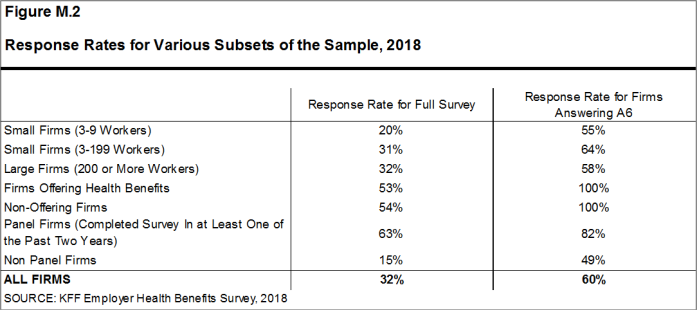

Response rates are calculated using a CASRO method, which accounts for firms that are determined to be ineligible in its calculation. The overall response rate is 32% [Figure M.2].5 The response rate for panel firms is higher than the response rate for non-panel firms [Figure M.2]. Similar to other employer and household surveys, the Employer Health Benefits Survey has seen a general decrease in response rates over time. Since 2017, we have attempted to increase the number of completes by increasing the number of non-panel firms in the sample. While this generally increases the precision of estimates by ensuring a sufficient number of respondents in various sub-groups, it has the effect of reducing the overall response rate.

To increase response rates, some firms with 3-9 employees were offered an incentive for participating in the survey. A third of these firms were sent a $5 Starbucks gift card in the advance letter, a third were offered both a $5 Starbucks gift card in the advance letter and an incentive of $25 in cash or as a donation to a charity of their choice after completing the full survey, and a third of firms were offered no incentive at all. Our analysis does not show significant differences in responses to key variables or participation rates among these incentive groups.

The vast majority of questions are asked only of firms that offer health benefits. A total of 1,872 of the 2,160 responding firms indicated they offered health benefits. The response rate for firms that offer health benefits is also 32%.

We asked one question of all firms in the study with which we made phone contact but where the firm declined to participate. The question was A6: “Does your company offer a health insurance program as a benefit to any of your employees?”. A total of 4,070 firms responded to this question (including 2,160 who responded to the full survey and 1,910 who responded to this one question). These responses are included in our estimates of the percentage of firms offering health benefits.6 The response rate for this question is 60% [Figure M.2].

Figure M.2: Response Rates for Various Subsets of the Sample, 2018

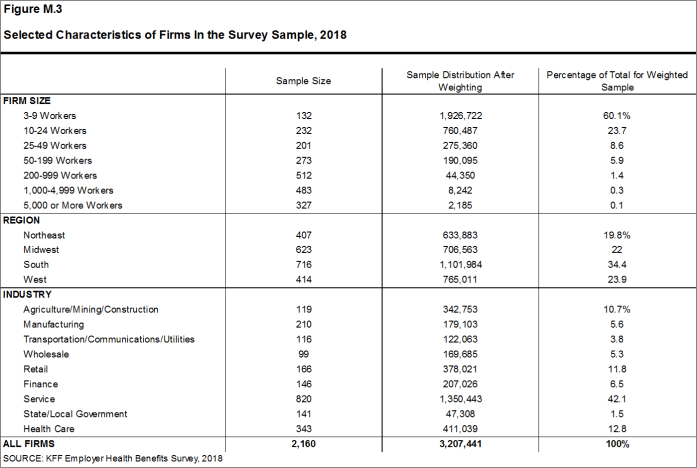

FIRM SIZE CATEGORIES AND KEY DEFINITIONS

Throughout the report, figures categorize data by size of firm, region, and industry. Unless otherwise specified, firm size definitions are as follows: small firms: 3 to 199 workers; and large firms: 200 or more workers. Figure M.3 shows selected characteristics of the survey sample. A firm’s primary industry classification is determined from Research Now SSI’s designation on the sampling frame and is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). A firm’s ownership category and other firm characteristics used in figures such as 3.5 and 6.18 are based on respondents’ answers. While there is considerable overlap in firms in the “State/Local Government” industry category and those in the “public” ownership category, they are not identical. For example, public school districts are included in the service industry even though they are publicly owned.

Figure M.3: Selected Characteristics of Firms In the Survey Sample, 2018

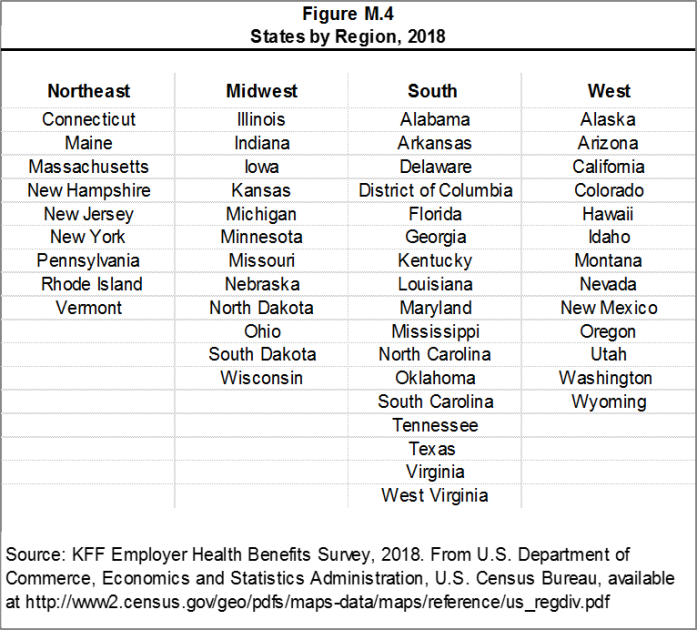

Figure M.4 presents the breakdown of states into regions and is based on the U.S Census Bureau’s categorizations. State-level data are not reported both because the sample size is insufficient in many states and we only collect information on a firm’s primary location rather than where all workers may actually be employed. Some mid- and large-size employers have employees in more than one state, so the location of the headquarters may not match the location of the plan for which we collected premium information.

Figure M.4: States by Region, 2018

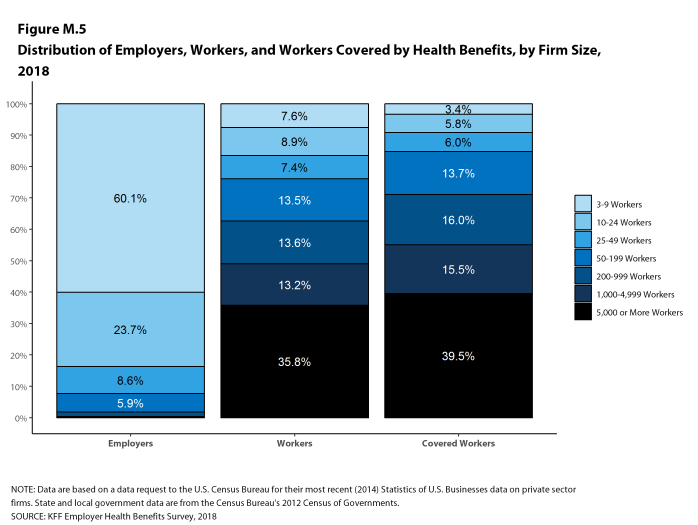

Figure M.5 displays the distribution of the nation’s firms, workers, and covered workers (employees receiving coverage from their employer). Among the three million firms nationally, approximately 60.1% employ 3 to 9 workers; such firms employ 7.6% of workers, and 3.4% of workers covered by health insurance. In contrast, less than one percent of firms employ 5,000 or more workers; these firms employ 35.8% of workers and 39.5% of covered workers. Therefore, the smallest firms dominate any statistics weighted by the number of employers. For this reason, most statistics about firms are broken out by size categories. In contrast, firms with 1,000 or more workers are the most influential employer group in calculating statistics regarding covered workers, since they employ the largest percentage of the nation’s workforce. Statistics among small firms and those weighted by the number of firms tend to have more variability.

Figure M.5: Distribution of Employers, Workers, and Workers Covered by Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 2018

Throughout this report, we use the term “in-network” to refer to services received from a preferred provider. Family coverage is defined as health coverage for a family of four. Definitions of the health plan types are available in Section 4, and a detailed explanation of the HDHP/SO plan type is in Section 8.

The survey asks firms what percentage of their employees earn more or less than a specified amount in order to identify the portion of a firm’s workforce that has relatively lower or higher wages. This year, the income threshold is $25,000 per year for lower-wage workers and $62,000 for higher-wage workers. These thresholds are based on the 25th and 75th percentile of workers’ earnings as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics using data from the Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) (2017).7 The cutoffs were inflation-adjusted and rounded to the nearest thousand. Prior to 2013, wage cutoffs were calculated using the now-eliminated National Compensation Survey.

ROUNDING AND IMPUTATION

Some figures in the report do not sum to totals due to rounding. In a few cases, numbers from distribution figures may not add to the numbers referenced in the text due to rounding. Although overall totals and totals for size and industry are statistically valid, some breakdowns may not be available due to limited sample sizes or a high relative standard error. Where the unweighted sample size is fewer than 30 observations, figures include the notation “NSD” (Not Sufficient Data). Estimates with high relative standard errors are reviewed and in some cases not published. Many breakouts by subsets may have a large standard error, meaning that even large differences are not statistically different.

To control for item nonresponse bias, we impute values that are missing for most variables in the survey. On average, 5% of observations are imputed. All variables are imputed following a hotdeck approach. The hotdeck approach replaces missing information with observed values from a firm similar in size and industry to the firm for which data are missing. In 2018, there were eleven variables where the imputation rate exceeded 20%; most of these cases were for individual plan level statistics. When aggregate variables were constructed for all of the plans, the imputation rate was usually much lower. There are a few variables that we have decided not to impute; these are typically variables where “don’t know” is considered a valid response option. Some variables are imputed based on their relationship to each other. For example, if a firm provided a worker contribution for family coverage but no premium information, a ratio between the family premium and family contribution was imputed and then the family premium was calculated. In addition, there are several variables in which missing data are calculated based on respondents’ answers to other questions (for example, employer contributions to premiums are calculated from the respondent’s premium and the worker contribution to premiums).

Since 2014, we estimate separate single and family coverage premiums for firms that provide premium amounts as the average cost for all covered workers, instead of differentiating between single and family coverage. This method more accurately accounts for the portion that each type of coverage contributes to the total cost for the less than one percent of covered workers who are enrolled at firms affected by this adjustment.

To ensure data accuracy we have several processes to review outliers and illogical responses. Every year several hundred firms are called back to confirm or correct responses. In some cases, answers are edited based on responses to open-ended questions or based on established logic rules.

WEIGHTING

Because we select firms randomly, it is possible through the use of statistical weights to extrapolate the results to national (as well as firm size, regional, and industry) averages. These weights allow us to present findings based on the number of workers covered by health plans, the number of total workers, and the number of firms. In general, findings in dollar amounts (such as premiums, worker contributions, and cost sharing) are weighted by covered workers. Other estimates, such as the offer rate, are weighted by firms. Specific weights were created to analyze the HDHP/SO plans that are offered with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) or that are Health Savings Account (HSA)-qualified. These weights represent the proportion of employees enrolled in each of these arrangements.

Calculation of the weights follows a common approach. The employer weight was determined by calculating the firm’s probability of selection. This weight was adjusted for nonresponse bias and trimmed of overly influential weights. Finally, we calibrated the weights to U.S. Census Bureau’s 2015 Statistics of U.S. Businesses for firms in the private sector, and the 2012 Census of Governments as the basis for calibration / post-stratification for public sector firms. Historic employer-weighted statistics were updated in 2011. The worker weight was calculated by multiplying the employer weight by the number of workers at the firm and then following the same weight adjustment process described above. The covered-worker weight and the plan-specific weights were calculated by multiplying the percentage of workers enrolled in each of the plan types by the firm’s worker weight. These weights allow analyses of all workers covered by health benefits and of workers in a particular type of health plan.

The trimming procedure follows the following steps: First, we grouped firms into size and offer categories of observations. Within each strata, we identified the median and the interquartile range of the weights and calculated the trimming cut point as the median plus six times the interquartile range (M + [6 * IQR]). Weight values larger than this cut point are trimmed to the cut point. In all instances, very few weight values were trimmed.

As in past years, we conducted a small follow-up survey of those firms with 3-49 workers that refused to participate in the full survey. Based on the results of a McNemar test, we were not able to verify that the results of the follow-up survey were comparable to the results from the original survey, and weights were not adjusted using the nonresponse adjustment process described in previous years’ methods. In 2010, 2015, and 2017, the results of the McNemar test were also significant and we did not conduct a nonresponse adjustment.

The survey collects information on primary and specialty care physician office visits for each plan type. Different plan types at the same firm may have different cost-sharing structures (e.g., copayments or coinsurance). Because the composite variables (using data from across all plan types) are reflective of only those plans with that provision, separate weights for the relevant variables were created in order to account for the fact that not all covered workers have such provisions.

To account for design effects, the statistical computing package R and the library package “survey” were used to calculate standard errors.

STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE

All statistical tests are performed at the .05 confidence level. For figures with multiple years, statistical tests are conducted for each year against the previous year shown, unless otherwise noted. No statistical tests are conducted for years prior to 1999.

Statistical tests for a given subgroup (firms with 25-49 workers, for instance) are tested against all other firm sizes not included in that subgroup (all firm sizes NOT including firms with 25-49 workers, in this example). Tests are done similarly for region and industry; for example, Northeast is compared to all firms NOT in the Northeast (an aggregate of firms in the Midwest, South, and West). However, statistical tests for estimates compared across plan types (for example, average premiums in PPOs) are tested against the “All Plans” estimate. In some cases, we also test plan-specific estimates against similar estimates for other plan types (for example, single and family premiums for HDHP/SOs against single and family premiums for HMO, PPO, and POS plans); these are noted specifically in the text. The two types of statistical tests performed are the t-test and the Wald test. The small number of observations for some variables resulted in large variability around the point estimates. These observations sometimes carry large weights, primarily for small firms. The reader should be cautioned that these influential weights may result in large movements in point estimates from year to year; however, these movements are often not statistically significant. Standard Errors for most key statistics are available in a technical supplement available at http://www.kff.org/ehbs.

2018 SURVEY

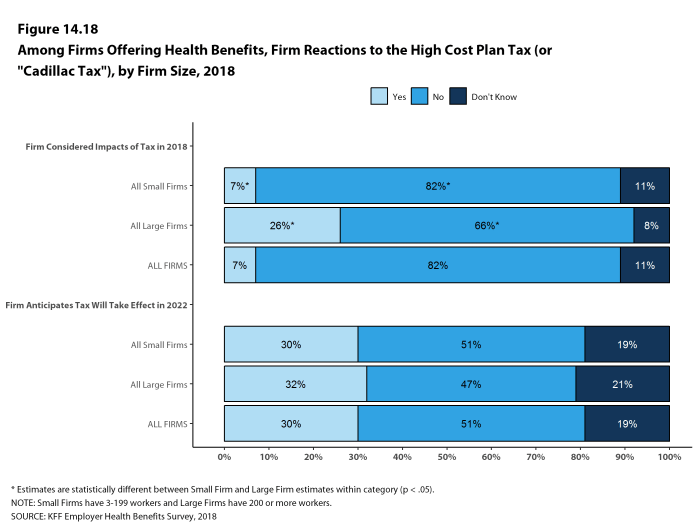

In light of a number of regulatory changes and policy proposals, we included new questions on the anticipated effects of the ACA’s individual mandate penalty repeal on the firm’s health benefits offerings, and the impact of the delay of the high cost plan tax, also known as the Cadillac tax, on the firm’s health benefits decisions. Also new in 2018 are questions asking about smaller firms’ use of level-funded premium plans, an alternative self-funding method with integrated stop loss coverage and a fixed monthly premium.

The 2018 survey also expands on retiree health benefits questions, asking firms about cost reduction strategies, whether they contribute to the cost of coverage, and how retiree benefits are offered (e.g., through a Medicare Advantage contract, a traditional employer plan, private exchange, etc.).

In 2018, we moved the battery of worker demographics questions from near the beginning of the survey to the end of the survey in an effort to improve the flow. There is no evidence that this move has impacted our survey findings and we will continue to monitor any suspected impacts.

Starting in 2018, we allowed respondents who did not know the combined maximum incentive or penalty an employee could receive for health screening and/or wellness and health promotion to answer a categorical question with specified ranges. This method is consistent with how we handle the percent of low-wage and high-wage workers at a firm. In 2018, 18% of respondents did not know the dollar value of the their incentive or penalty and 39% were able to estimate a range.

Starting in 2018, the survey began asking small firms who indicated that their plan was fully-insured whether the plan was level-funded. In a level-funded plan, employers make a set payment each month to an insurer or third party administrator which funds a reserve account for claims, administrative costs, and premiums for stop-loss coverage. These plans are often integrated and firms may not understand the complexities of the self-funded mechanisms underlying them. Some small employers who indicate that their plan is self-funded may also offer a plan that meets this definition. Respondents offering level funded plans were asked about any attachment points applying to enrollees. These firms were not less likely to answer this question, and including them doesn’t not substantially change the average. Prior to 2018, all firms reporting coverage as underwritten by an insurer were excluded from the stop-loss calculations.

For prescription drug coverage, similar to years past, if the firm reports that the worker pays the full cost for drugs on a particular tier and/or that the plan only offers access to a discount program, we do not consider this as offering covering for that drug tier. Hospital, outpatient surgery and prescription drug cost-sharing was only asked of a firm’s largest plan type.

The response option choices for the type of incentive or penalty for completing biometric screening or a health risk assessment changed from 2017 to 2018.

Values below 3% are not shown on graphical figures to improve the readability of those graphs. The underlying data for all estimates presented in graphs are available at http://www.kff.org/ehbs.

Annual inflation estimates are usually calculated from April to April. The 12 month percentage change for May to May was 2.5%.8

HISTORICAL DATA

Data in this report focus primarily on findings from surveys conducted and authored by the Kaiser Family Foundation since 1999. Between 1999 and 2017, the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) co-authored this survey. HRET’s divestiture had no impact on our survey methods, which remain the same as years past. Prior to 1999, the survey was conducted by the Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA) and KPMG using a similar survey instrument, but data are not available for all the intervening years. Following the survey’s introduction in 1987, the HIAA conducted the survey through 1990, but some data are not available for analysis. KPMG conducted the survey from 1991-1998. However, in 1991, 1992, 1994, and 1997, only larger firms were sampled. In 1993, 1995, 1996, and 1998, KPMG interviewed both large and small firms. In 1998, KPMG divested itself of its Compensation and Benefits Practice, and part of that divestiture included donating the annual survey of health benefits to HRET.

This report uses historical data from the 1993, 1996, and 1998 KPMG Surveys of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits and the 1999-2017 Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits. For a longer-term perspective, we also use the 1988 survey of the nation’s employers conducted by the HIAA, on which the KPMG and KFF surveys are based. The survey designs for the three surveys are similar.

Additional information on the 2018 Employer Health Benefit Survey is available at http://www.kff.org/ehbs, including an article in the Journal Health Affairs, an interactive graphic, historic reports and a technical supplement. Researchers may also request a public use dataset here: https://www.kff.org/contact-us/

Published: October 3rd, 2018. Last Updated: September 27, 2018.

- HDHP/SO includes high-deductible health plans with a deductible of at least $1,000 for single coverage and $2,000 for family coverage and that offer either a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA) or a Health Savings Account (HSA). Although HRAs can be offered along with a health plan that is not an HDHP, the survey collected information only on HRAs that are offered along with HDHPs. For specific definitions of HDHPs, HRAs, and HSAs, see the introduction to Section 8.↩

- Response rate estimates are calculated by dividing the number of completes over the number of refusals and the fraction of the firms with unknown eligibility to participate estimated to be eligible. Firms determined to be ineligible to complete the survey are not included in the response rate calculation.↩

- Estimates presented in Figures 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6 are based on the sample of both firms that completed the entire survey and those that answered just one question about whether they offer health benefits.↩

- General information on the OES can be found at http://www.bls.gov/oes/oes_emp.htm#scope. A comparison between the OES and the NCS is available at https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2013/article/lettau-zamora.htm↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, U.S. City Average of Annual Inflation, 1998-2018; (cited 2018 July 20). https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CUUR0000SA0.↩

Section One: Cost Of Health Insurance

The average annual premiums in 2018 are $6,896 for single coverage and $19,616 for family coverage. The average premium for single coverage increased by 3% since 2017 and the average premium for family coverage increased by 5%. The average family premium has increased 55% since 2008 and 20% since 2013. The average family premium for covered workers in small firms (3-199 workers) ($18,739) is significantly lower than average family premiums for workers in large firms (200 or more workers) ($19,972).

This graphing tool allows users to look at changes in premiums and worker contributions for covered workers at different types of firms over time: https://www.kff.org/interactive/premiums-and-worker-contributions/

PREMIUMS FOR SINGLE AND FAMILY COVERAGE

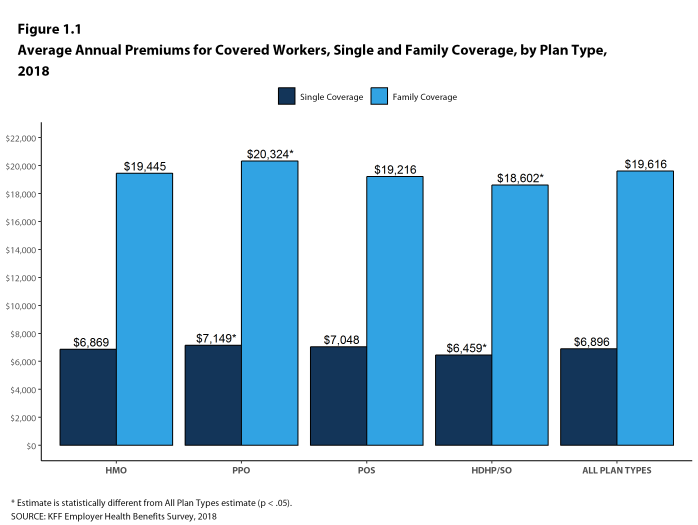

- The average premium for single coverage in 2018 is $6,896 per year. The average premium for family coverage is $19,616 per year [Figure 1.1].

- The average annual premium for family coverage for covered workers in small firms ($18,739) is lower than the average premium for covered workers in large firms ($19,972) [Figure 1.2].

- The average annual premiums for covered workers in HDHP/SOs are lower for single coverage ($6,459) and family coverage ($18,602) than overall average premiums. The average premiums for covered workers enrolled in PPOs are higher for single ($7,149) and family coverage ($20,324) than the overall plan average [Figure 1.1].

- The average premium for covered workers with single coverage is higher in the Northeast ($7,172) than in all other regions. Compared to the average premium for family coverage for covered workers in other regions, the average family premium for covered workers in the Northeast ($20,697) is higher and the average family premium for covered workers in the South is lower ($19,057) [Figure 1.3].

- The average premiums for covered workers vary across industries. The average premiums for covered workers in the Agriculture/Mining/Construction industry category are relatively lower for single ($6,241) and family ($17,417) coverage [Figure 1.4].

- The average premiums for covered workers in firms with a relatively large share of older workers (where at least 35% of the workers are age 50 or older) are higher than the average premiums for covered workers in firms with a smaller share of older workers ($7,288 vs. $6,560 for single coverage and $20,463 vs. $18,887 for family coverage) [Figure 1.6].

- The average premiums for covered workers in firms with at least some union workers are higher than the average premiums for covered workers in firms without union workers for family coverage ($20,333 vs. $19,234) [Figure 1.5].

- Premiums also vary by type of firm ownership. For both single and family coverage, covered workers at private for-profit firms have lower average annual premiums than covered workers at public firms or private not-for-profit firms [Figure 1.6].

Figure 1.1: Average Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, Single and Family Coverage, by Plan Type, 2018

Figure 1.2: Average Monthly and Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, by Plan Type and Firm Size, 2018

Figure 1.3: Average Monthly and Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, by Plan Type and Region, 2018

Figure 1.4: Average Monthly and Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, by Plan Type and Industry, 2018

Figure 1.5: Average Annual Premiums for Covered Workers With Family Coverage, by Firm Characteristics, 2018

Figure 1.6: Average Annual Premiums for Covered Workers, by Firm Characteristics and Firm Size, 2018

PREMIUM DISTRIBUTION

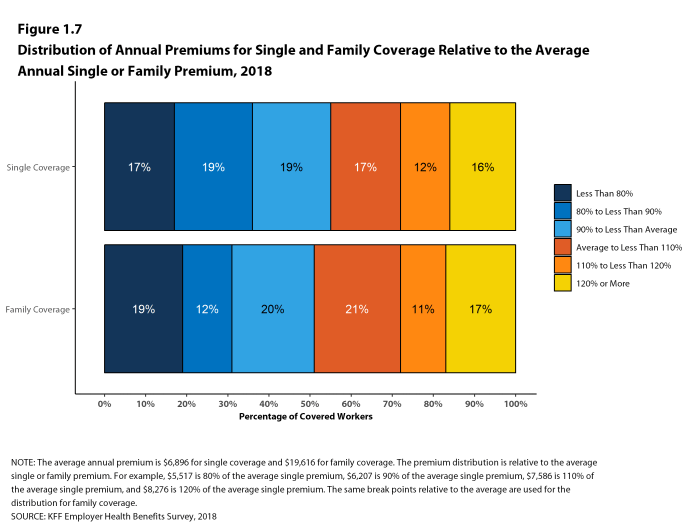

- There is considerable variation in premiums for both single and family coverage.

- Sixteen percent of covered workers are employed in a firm with a single premium at least 20% higher than the average single premium, while 17% of covered workers are in firms with a single premium less than 80% of the average single premium [Figure 1.7].

- For family coverage, 17% of covered workers are employed in a firm with a family premium at least 20% higher than the average family premium, while 19% of covered workers are in firms with a family premium less than 80% of the average family premium [Figure 1.7].

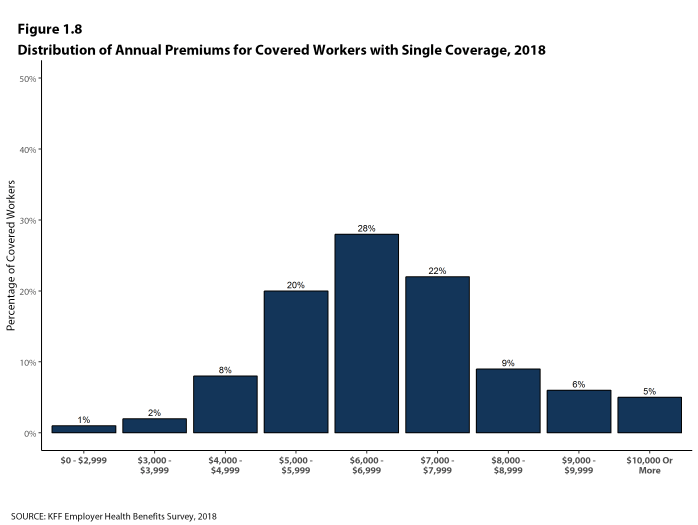

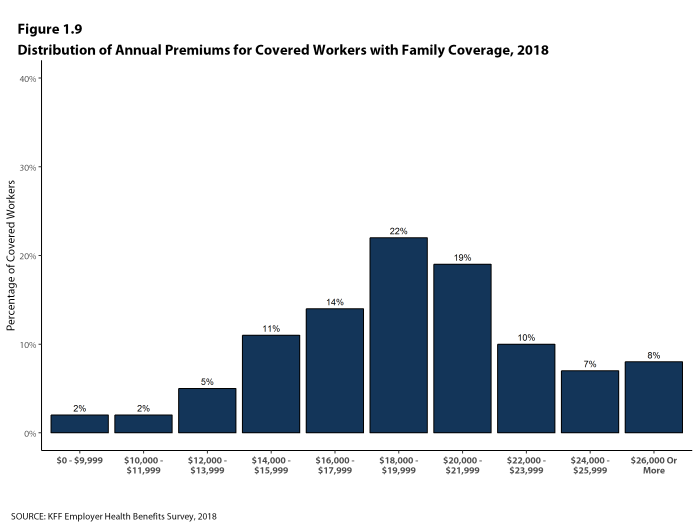

- Five percent of covered workers are in a firm with an average annual premium of at least $10,000 for single coverage [Figure 1.8]. Eight percent of covered workers are in a firm with an average annual premium of at least $26,000 for family coverage [Figure 1.9].

Figure 1.7: Distribution of Annual Premiums for Single and Family Coverage Relative to the Average Annual Single or Family Premium, 2018

Figure 1.8: Distribution of Annual Premiums for Covered Workers With Single Coverage, 2018

Figure 1.9: Distribution of Annual Premiums for Covered Workers With Family Coverage, 2018

PREMIUM CHANGES OVER TIME

- The average premium for single coverage is 3% higher than the single premium last year, and the average premium for family coverage is 5% higher than the average family premium last year.

- The average premium for single coverage has grown 17% since 2013 and the average premium for family coverage has grown 20% over the same period.

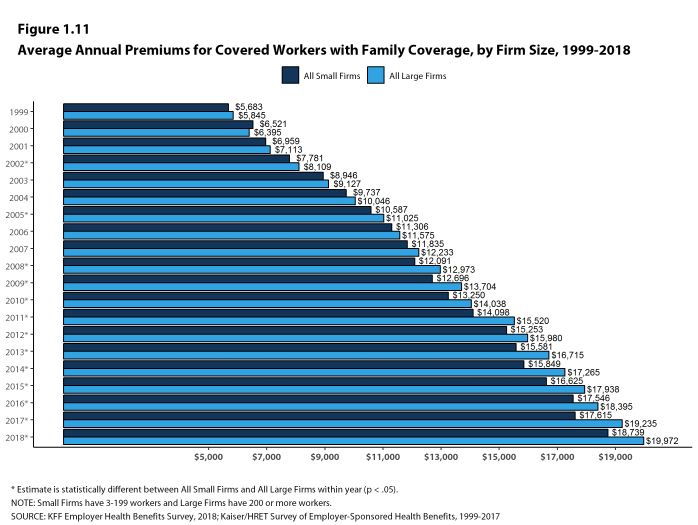

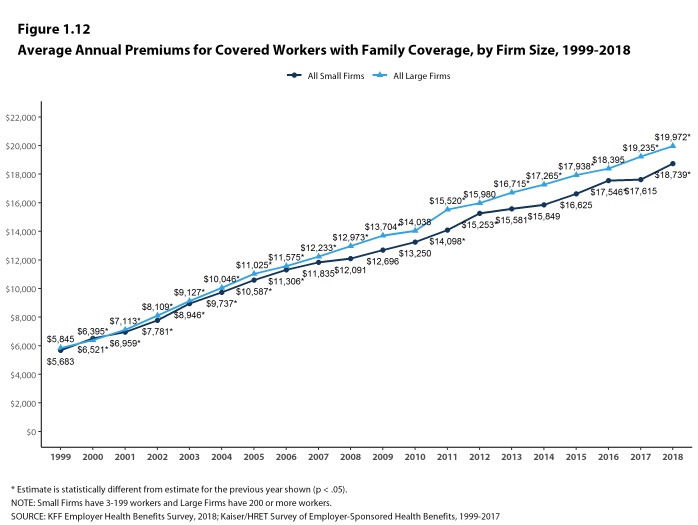

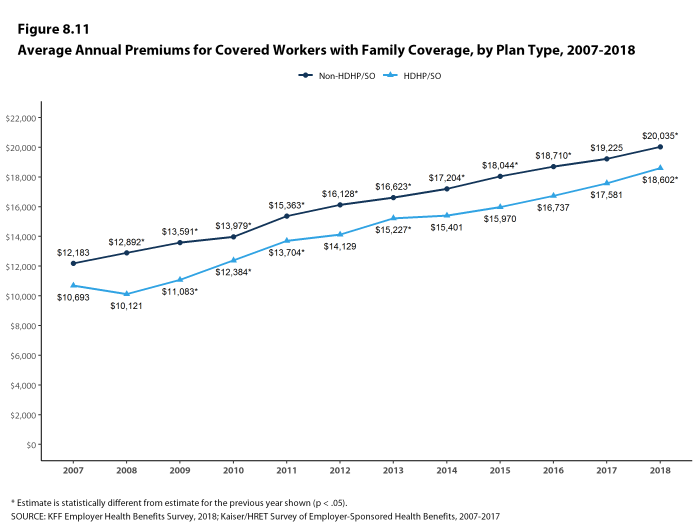

- The average family premiums for both small and large firms have increased at similar rates since 2013 (20% for small firms and 19% for large firms). For small firms, the average family premium rose from $15,581 in 2013 to $18,739 in 2018. For large firms, the average family premium rose from $16,715 in 2013 to $19,972 in 2018 [Figures 1.11 and 1.12].

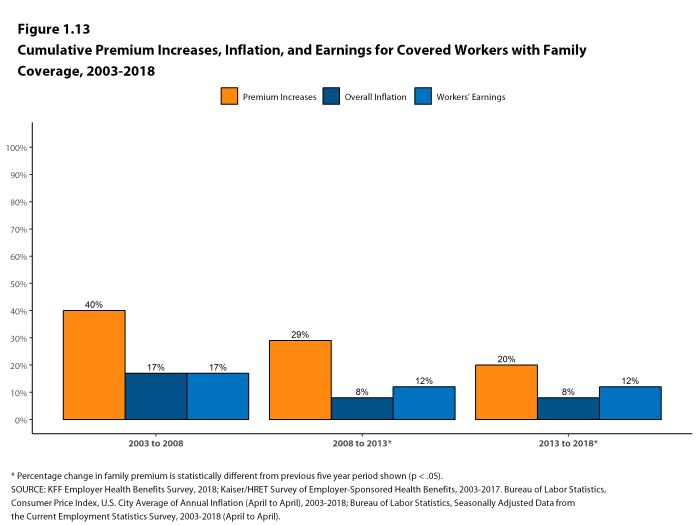

- The $19,616 average family premium in 2018 is 20% higher than the average family premium in 2013 and 55% higher than the average family premium in 2008. The 20% family premium growth in the past five years is smaller than the 29% growth between 2008 and 2013, or the 40% premium growth between 2003 and 2008 [Figure 1.13].

- The average family premiums for both small and large firms have increased at similar rates since 2008 (55% for small firms and 54% for large firms). For small firms, the average family premium rose from $12,091 in 2008 to $18,739 in 2018. For large firms, the average family premium rose from $12,973 in 2008 to $19,972 in 2018 [Figures 1.11 and 1.12].

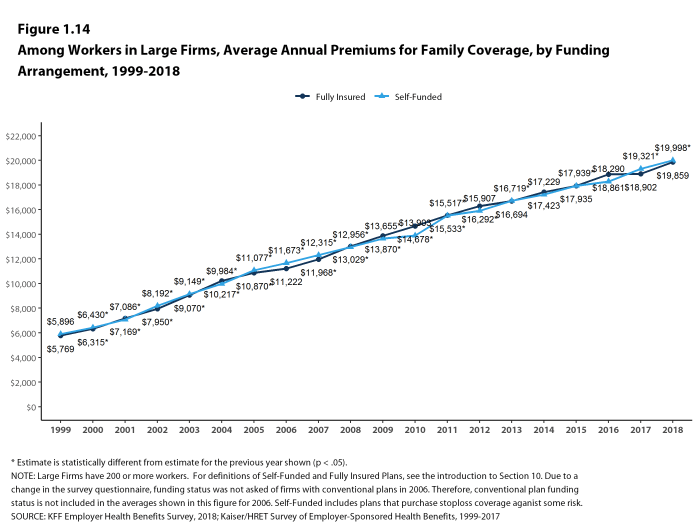

- For covered workers in large firms, over the past five years, the average family premium in firms that are fully insured has grown at a similar rate to the average family premium for covered workers in fully or partially self-funded firms (19% for fully insured plans and 20% for self-funded firms) [Figure 1.14].

Figure 1.10: Average Annual Premiums for Single and Family Coverage, 1999-2018

Figure 1.11: Average Annual Premiums for Covered Workers With Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

Figure 1.12: Average Annual Premiums for Covered Workers With Family Coverage, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

Figure 1.13: Cumulative Premium Increases, Inflation, and Earnings for Covered Workers With Family Coverage, 2003-2018

Figure 1.14: Among Workers In Large Firms, Average Annual Premiums for Family Coverage, by Funding Arrangement, 1999-2018

Section Two: Health Benefits Offer Rates

While nearly all large firms (200 or more workers) offer health benefits to at least some workers, small firms (3-199 workers) are significantly less likely to do so. The percentage of all firms offering health benefits in 2018 (57%) is similar to the percentages of firms offering health benefits last year (53%) and five years ago (57%), but lower than the percentage of firms offering health benefits ten years ago (63%). As we reported last year, there has been a long-term decline in the offer and coverage rates for employer-provided coverage, particularly among smaller firms.9

Almost all firms that offer coverage offer to dependents such as children and the spouses of eligible employees. Firms not offering health benefits continue to cite cost as the most important reason they do not do so.

FIRM OFFER RATES

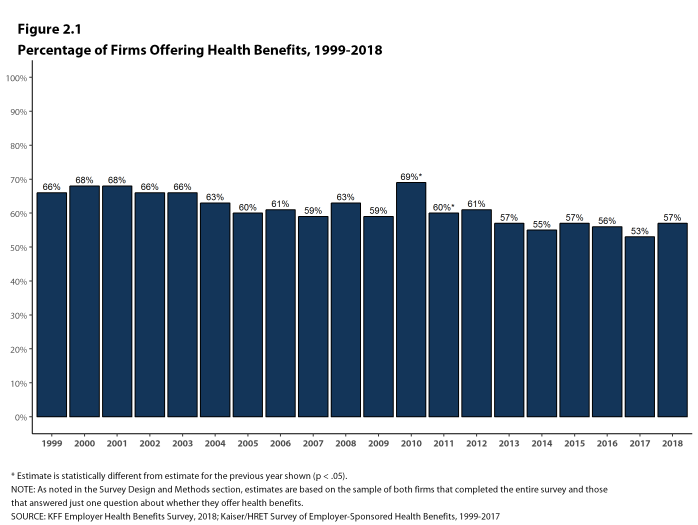

- In 2018, 57% of firms offer health benefits, similar to the 53% who reported doing so in 2017 [Figure 2.1]. Because surveys only collect information from a sample of the total number of firms in the country, there is uncertainty in any estimate. Since there are so many small firms, sometimes even seemingly large differences are not statistically different.10

- The overall percentage of firms offering coverage in 2018 is the same as the percentage offering coverage in 2013 (57%) but lower than the percentage in 2008 (63%) [Figure 2.1].

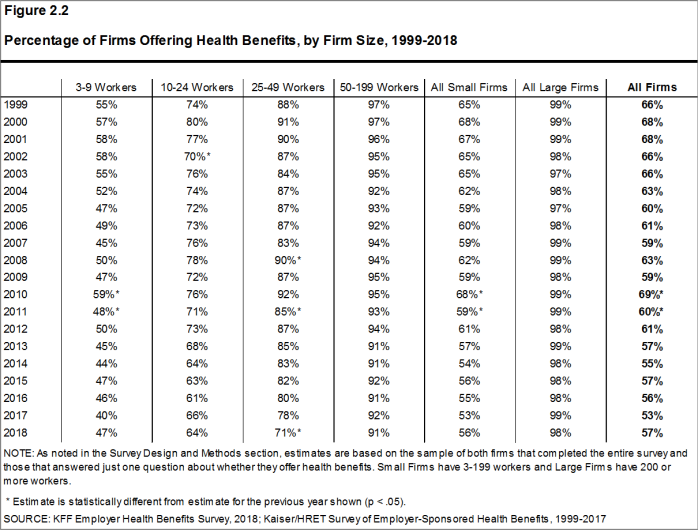

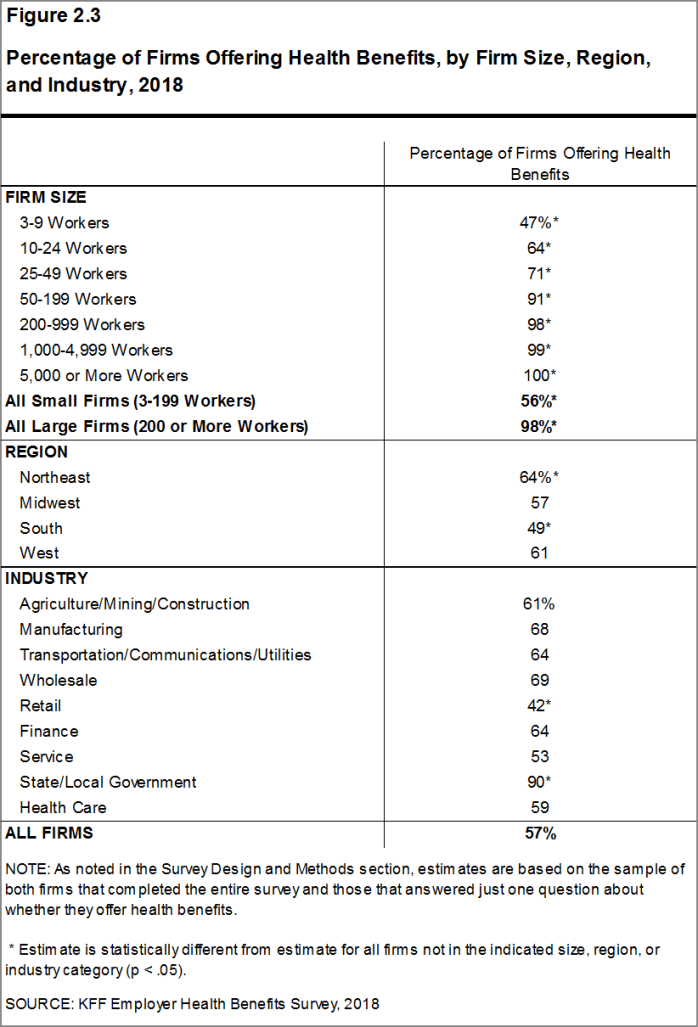

- Ninety-eight percent of large firms offer health benefits to at least some of their workers. In contrast, only 56% of small firms offer health benefits [Figures 2.2 and 2.3]. The percentages of both small and large firms offering health benefits to at least some of their workers are similar to last year [Figure 2.2].

- The smallest-sized firms are least likely to offer health insurance: 47% of firms with 3-9 workers offer coverage, compared to 71% of firms with 25-49 workers, and 91% of firms with 50-199 workers [Figure 2.3]. Since most firms in the country are small, variation in the overall offer rate is driven largely by changes in the percentages of the smallest firms (3-9 workers) offering health benefits. For more information on the distribution of firms in the country, see the Survey Design and Methods Section and Figure M.4.

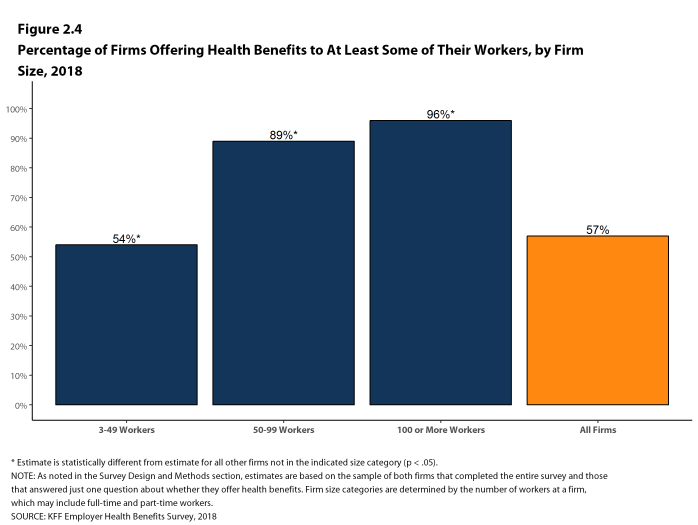

- Ninety-six percent of firms with 100 or more workers offer health benefits to at least some of their workers. Eighty-nine percent of firms with 50-99 workers offer benefits to at least some workers [Figure 2.4].

- Ninety percent of all workers are employed by a firm that offers health benefits to at least some of its workers [Figure 2.6].

Figure 2.1: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, 1999-2018

Figure 2.2: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

Figure 2.3: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2018

Figure 2.4: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits to at Least Some of Their Workers, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 2.5: Percentage of Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

Figure 2.6: Percentage of Workers at Firms That Offer Health Benefits to at Least Some Workers, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

PART-TIME AND TEMPORARY WORKERS

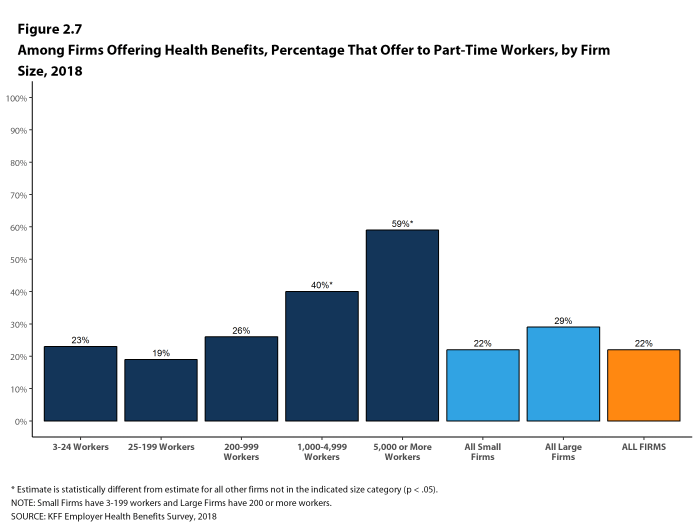

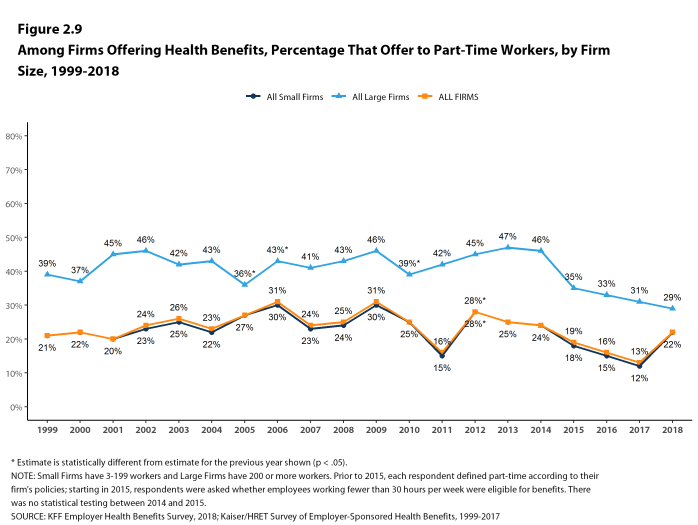

- Among firms offering health benefits, relatively few offer benefits to their part-time and temporary workers.

Beginning in 2015, we modified the survey to explicitly ask employers whether they offered benefits to employees working fewer than 30 hours. Our previous question did not include a definition of “part-time”. For this reason, historical data on part-time offer rates are shown, but we did not test whether the differences between 2014 and 2015 were significant. Many employers may work with multiple definitions of part-time; one for their compliance with legal requirements and another for internal policies and programs.

- The Affordable Care Act (ACA) defines full-time workers as those who on average work at least 30 hours per week, and part-time workers as those who on average work fewer than 30 hours per week. The employer shared responsibility provision of the ACA requires that firms with at least 50 full-time equivalent employees offer most full-time employees coverage that meets minimum standards or be assessed a penalty.11

- In 2018, 22% of all firms that offer health benefits offer them to part-time workers. Small firms and large firms have similar rates of offering to part-time workers [Figure 2.7].

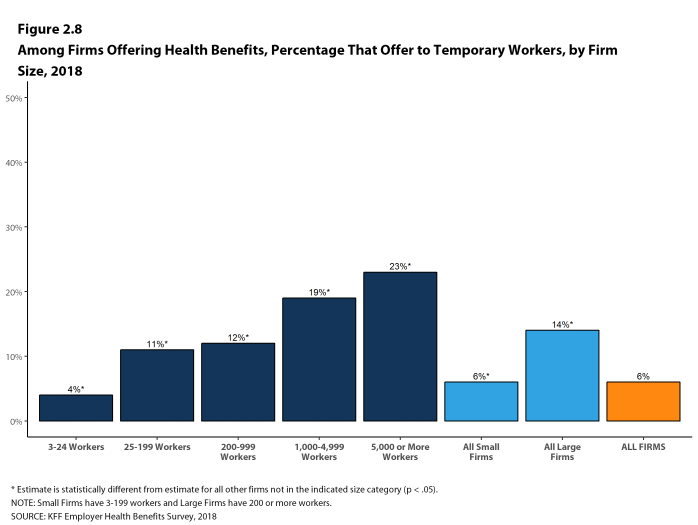

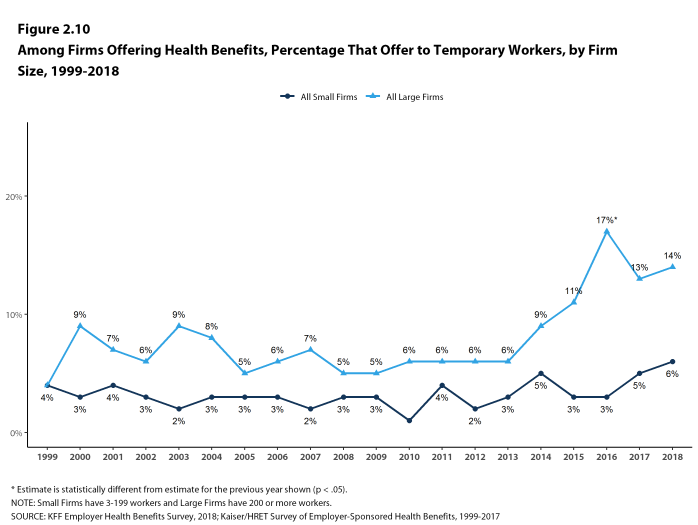

- A small percentage (6%) of firms offering health benefits offer them to temporary workers [Figure 2.8].

- Among firms offering health benefits, large firms are more likely than small firms to offer benefits to temporary workers (14% vs. 6%) [Figure 2.8].

- The percentage of large firms offering health benefits to temporary workers is not statistically different from the 13% reported in 2017, but is an increase from ten years ago (5%) [Figure 2.10].

Figure 2.7: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Part-Time Workers, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 2.8: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Temporary Workers, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 2.9: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Part-Time Workers, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

Figure 2.10: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Temporary Workers, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

SPOUSES, DEPENDENTS, AND DOMESTIC PARTNER BENEFITS

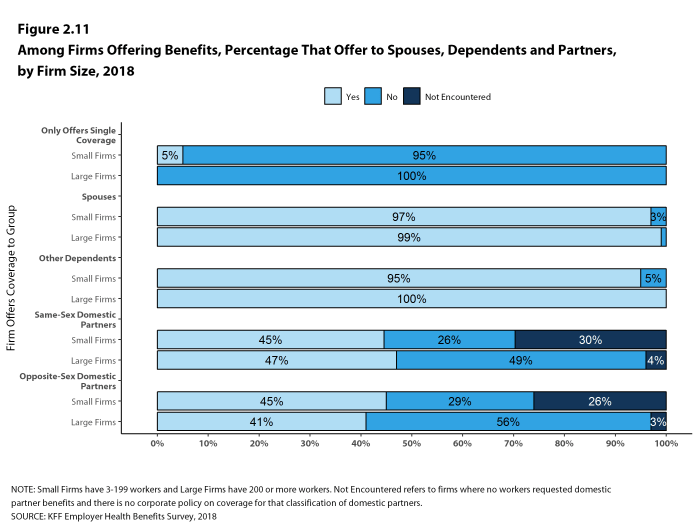

- The majority of firms offering health benefits offer to spouses and dependents, such as children.

- In 2018, 97% of small firms and 99% of large firms offering health benefits offer coverage to spouses, similar to the percentages last year [Figure 2.11].

- Ninety-five percent of small firms and 100% of large firms offering health benefits cover other dependents, such as children, similar to last year [Figure 2.11].

- Five percent of small firms offering health benefits offer only single coverage to their workers [Figure 2.11].

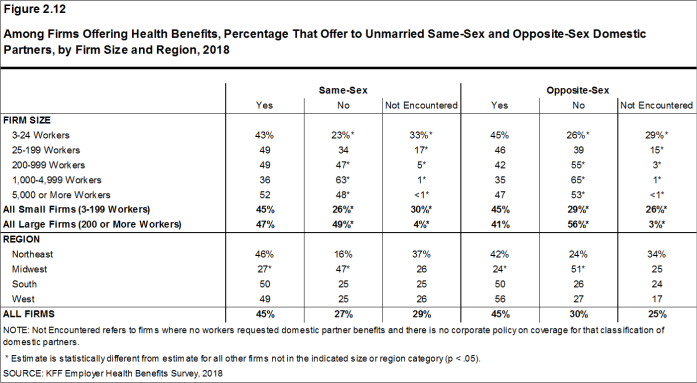

- Firms were also asked whether they offer health benefits to same-sex or opposite-sex domestic partners. While definitions may vary, employers often define domestic partners as an unmarried couple who has lived together for a specified period of time. Firms may define domestic partners separately from any legal requirements a state may have.

- Forty-five percent of firms offering health benefits offer coverage to opposite-sex domestic partners, similar to the 36% that did so last year.

- Forty-five percent of firms offering health benefits offer coverage to same-sex domestic partners, similar to the 40% that did so last year.

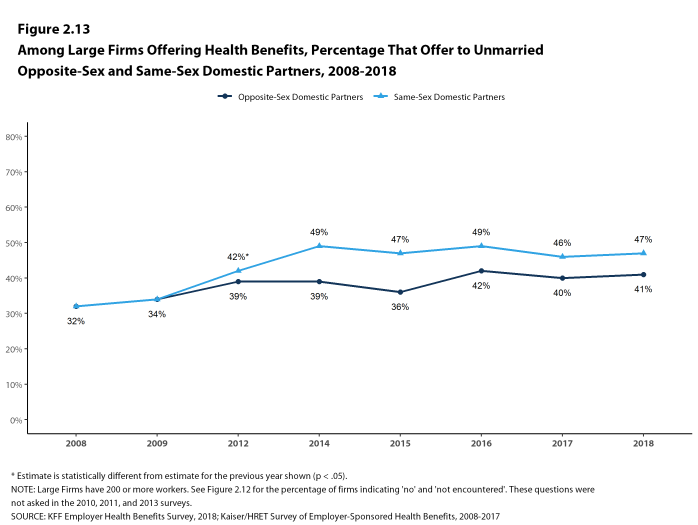

- Forty-one percent of large firms offering health benefits offer coverage to opposite-sex domestic partners, similar to the 40% that did so last year [Figure 2.13].

- Forty-seven percent of large firms offering health benefits offer coverage to same-sex domestic partners, similar to the 46% that did so last year [Figure 2.13].

- When firms are asked if they offer health benefits to opposite or same-sex domestic partners, many small firms report that they have not encountered this issue. These firms may not have formal human resource policies on domestic partners simply because none of the firm’s workers have asked to cover a domestic partner. Regarding health benefits for opposite-sex domestic partners, 26% of small firms report that they have not encountered this request or that the question was not applicable. Similarly, for health benefits for same-sex domestic partners, 30% of small firms report that they have not encountered the request or that the question was not applicable [Figure 2.12].

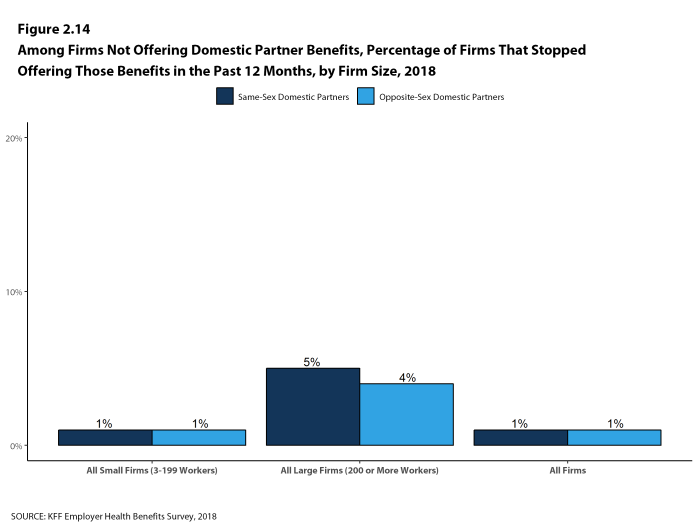

- Among large firms not offering health benefits to same-sex domestic partners, 5% stopped offering them within the past 12 months [Figure 2.14].

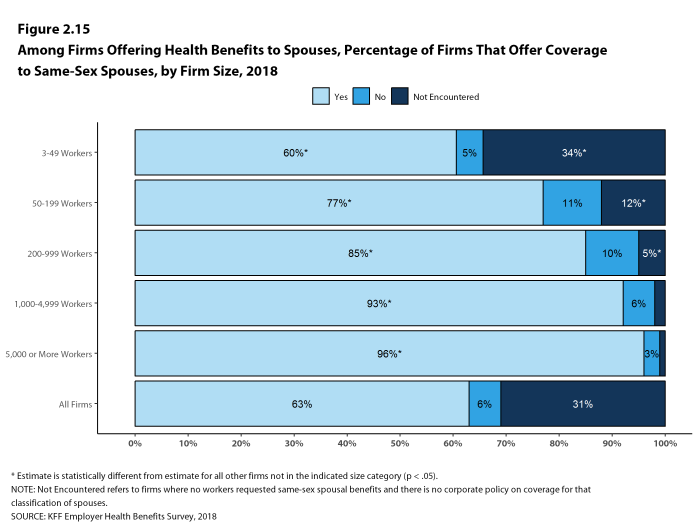

- Over half (63%) of firms that offer health benefits to spouses also offer coverage to same-sex spouses [Figure 2.15].

- Large firms are more likely than small firms to offer coverage to same-sex spouses (87% vs. 62%).

- Small firms are more likely than large firms to report that this request has not been encountered (32% vs. 4%).

- Among all firms that offer health benefits, 13% report providing additional compensation or benefits to employees if they enroll in a spouse’s plan, and 16% provide additional compensation or benefits to employees if they do not participate in the firm’s health benefits [Figure 2.17].

Figure 2.11: Among Firms Offering Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Spouses, Dependents and Partners, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 2.12: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Unmarried Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex Domestic Partners, by Firm Size and Region, 2018

Figure 2.13: Among Large Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage That Offer to Unmarried Opposite-Sex and Same-Sex Domestic Partners, 2008-2018

Figure 2.14: Among Firms Not Offering Domestic Partner Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Stopped Offering Those Benefits In the Past 12 Months, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 2.15: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits to Spouses, Percentage of Firms That Offer Coverage to Same-Sex Spouses, by Firm Size, 2018

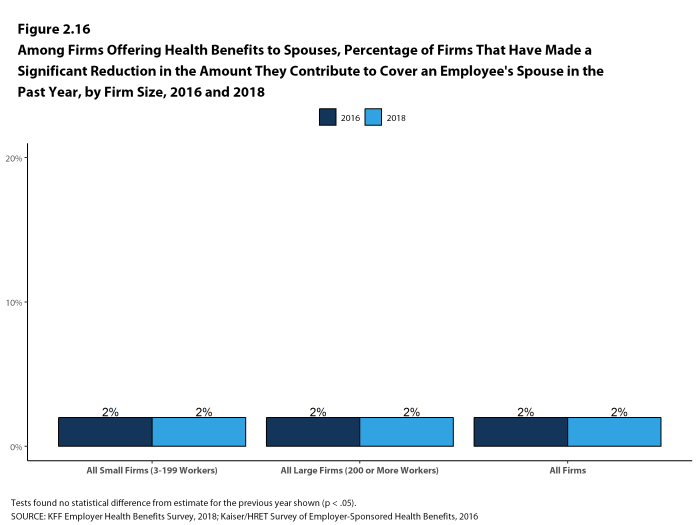

Figure 2.16: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits to Spouses, Percentage of Firms That Have Made a Significant Reduction In the Amount They Contribute to Cover an Employee’s Spouse In the Past Year, by Firm Size, 2016 and 2018

Figure 2.17: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Provide Workers Additional Incentives for Various Enrollment Decisions, by Firm Size, 2018

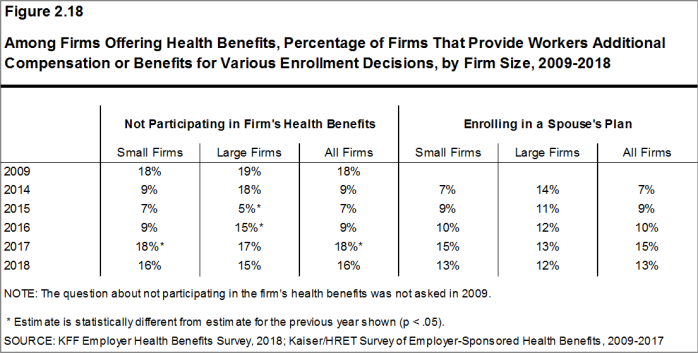

Figure 2.18: Among Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Provide Workers Additional Compensation or Benefits for Various Enrollment Decisions, by Firm Size, 2009-2018

FIRMS NOT OFFERING HEALTH BENEFITS

- The survey asks firms that do not offer health benefits if they have offered insurance or shopped for insurance in the recent past, and about their most important reasons for not offering coverage. Because such a small percentage of large firms report not offering health benefits, we present responses for small non-offering firms only.

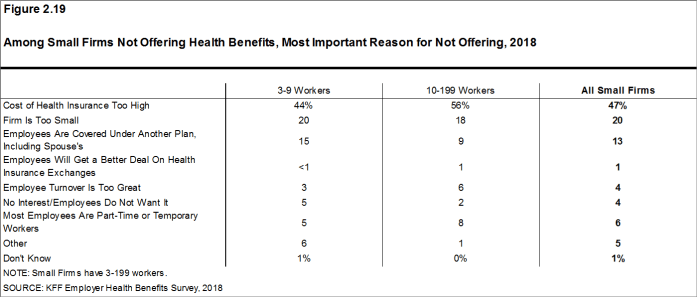

- The cost of health insurance remains the primary reason cited by firms for not offering health benefits. Among small firms not offering health benefits, 47% cite high cost as “the most important reason” for not doing so, followed by “the firm is too small” (20%). Few small firms indicate that they do not offer because they believe employees will get a better deal on the health insurance exchanges (1%) [Figure 2.19].

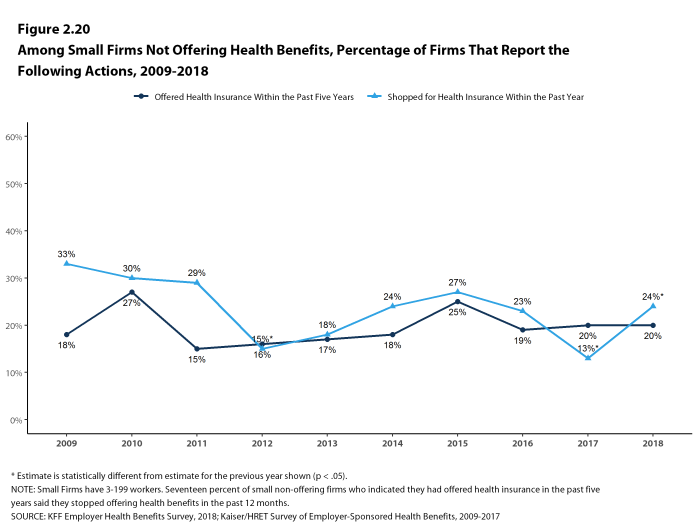

- Many small non-offering firms have either offered health insurance in the past five years or shopped for health insurance in the past year.

- Twenty percent of small non-offering firms have offered health benefits in the past five years, the same percentage reported last year [Figure 2.20].

- Twenty-four percent of small non-offering firms have shopped for coverage in the past year, an increase from last year (13%) [Figure 2.20].

- Among small non-offering firms that report they stopped offering coverage within the past five years, 17% stopped offering coverage within the past year, similar to the percentage reported last year.

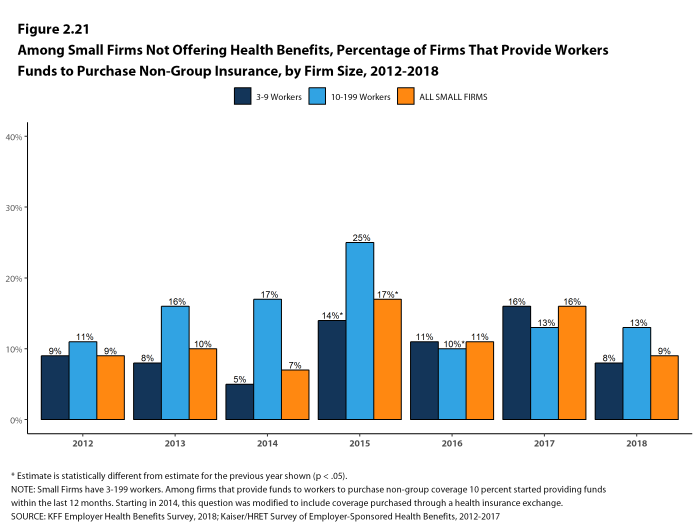

- Among small non-offering firms, 9% report that they provide funds to their employees to purchase health insurance on their own in the individual market or through a health insurance exchange [Figure 2.21].

Figure 2.19: Among Small Firms Not Offering Health Benefits, Most Important Reason for Not Offering, 2018

Figure 2.20: Among Small Firms Not Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Report the Following Actions, 2009-2018

Figure 2.21: Among Small Firms Not Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Firms That Provide Workers Funds to Purchase Non-Group Insurance, by Firm Size, 2012-2018

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Diminishing offer and coverage rates among private sector employees. Menlo Park, (CA): KFF; 2016 Sep (cited 2017 Jul 13). Available from: http://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/diminishing-offer-and-coverage-rates-among-private-sector-employees/↩

- For more information on the Employer Health Benefits Survey’s weighting and design please see the Survey Design and Methods section.↩

- Internal Revenue Code. 26 U.S. Code § 4980H – Shared responsibility for employers regarding health coverage. 2011. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2011-title26/pdf/USCODE-2011-title26-subtitleD-chap43-sec4980H.pdf↩

Section Three: Employee Coverage, Eligibility, And Participation

Employers are the principal source of health insurance in the United States, providing health benefits for about 152 million non-elderly people in America.12 Most workers are offered health coverage at work, and the majority of workers who are offered coverage take it. Workers may not be covered by their own employer for several reasons: their employer may not offer coverage, they may not be eligible for the benefits offered by their firm, they may elect to receive coverage through their spouse’s employer, or they may refuse coverage from their firm. In 2018, 60% of covered workers in firms offering health benefits are covered by their own firm, similar to the percentage in recent years, but lower than the percentage ten years ago (65%).

Before eligible workers may enroll in benefits at their firm, 71% of covered workers face a waiting period.

ELIGIBILITY

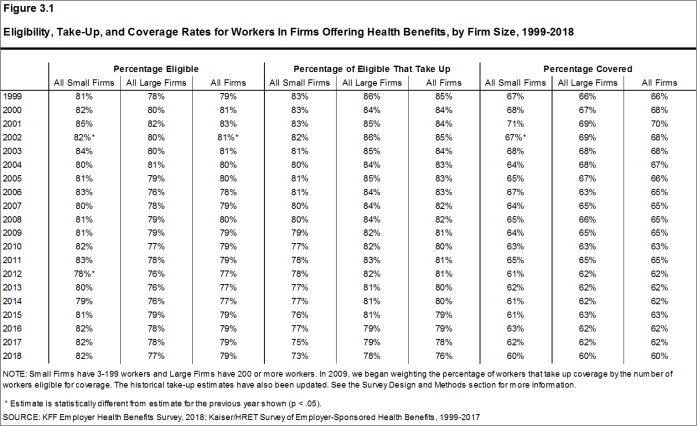

- Even in firms that offer health benefits, some workers may not be eligible to participate.13 Many firms, for example, do not offer coverage to part-time or temporary workers. Among workers in firms offering health benefits in 2018, 79% are eligible to enroll in the benefits offered by their firm, similar to the percentages last year and the recent past for both small and large firms [Figure 3.1].

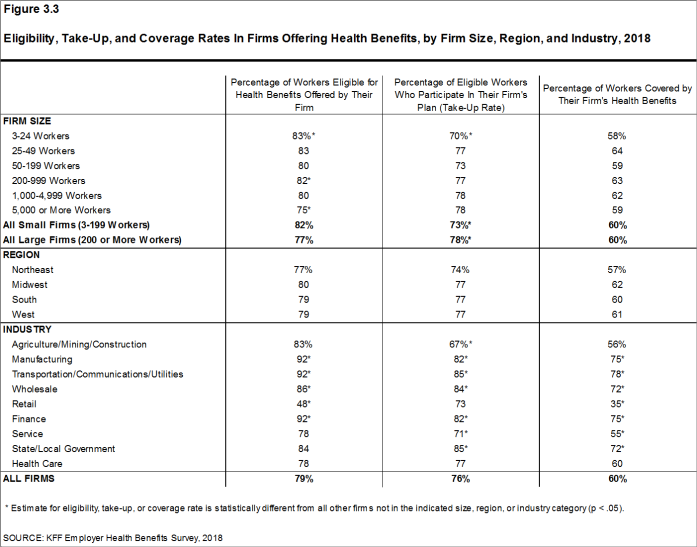

- The percentage of workers eligible to enroll in health benefits at their firm is relatively higher in firms with 3-24 workers (83%) and firms with 200-999 workers (82%), and relatively lower in firms with 5,000 or more workers (75%) [Figure 3.3].

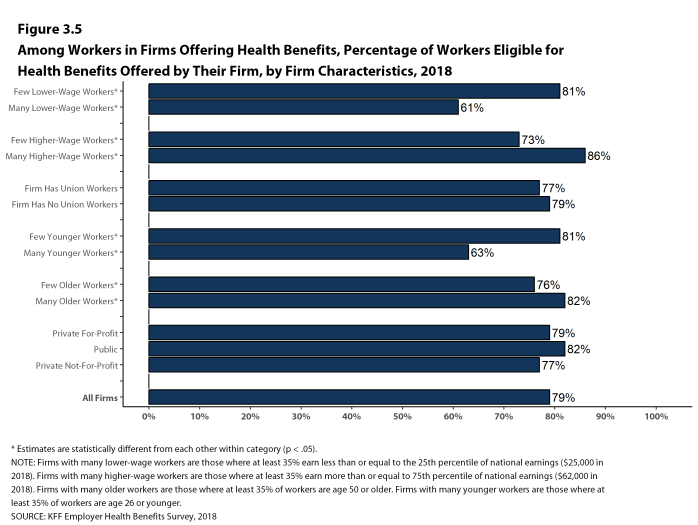

- Eligibility varies considerably by firm wage level. Workers in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers (where at least 35% of workers earn $25,000 a year or less) are less likely to be eligible for health benefits than workers in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers (61% vs. 81%) [Figure 3.5].

- Workers in firms with a relatively large share of higher-wage workers (where at least 35% earn $62,000 or more annually) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than workers in firms with a smaller share of higher-wage workers (86% vs. 73%) [Figure 3.5].

- Eligibility also varies by the age of the workforce. Those in firms with a relatively small share of younger workers (where fewer than 35% of the workers are age 26 or younger) are more likely to be eligible for health benefits than those in firms with a larger share of younger workers (81% vs. 63%) [Figure 3.5].

- Eligibility rates vary considerably for workers in different industries. The average eligibility rate is particularly low in retail firms (48%) [Figure 3.3].

Figure 3.1: Eligibility, Take-Up, and Coverage Rates for Workers In Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

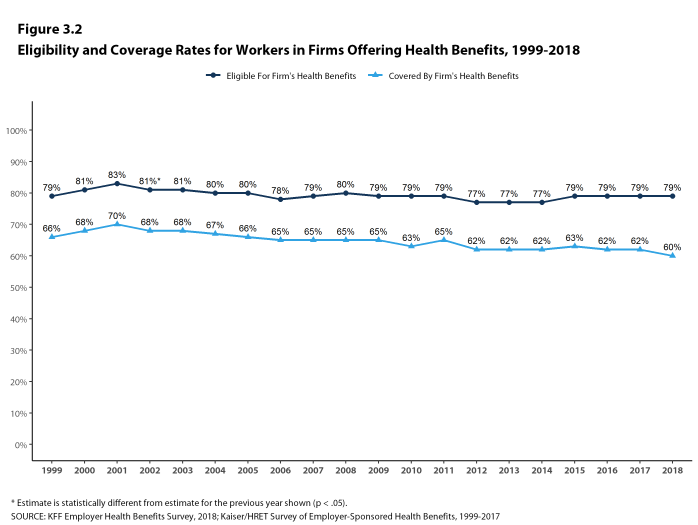

Figure 3.2: Eligibility and Coverage Rates for Workers In Firms Offering Health Benefits, 1999-2018

Figure 3.3: Eligibility, Take-Up, and Coverage Rates In Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, Region, and Industry, 2018

Figure 3.4: Eligibility, Take-Up, and Coverage Rates In Firms Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 2018

Figure 3.5: Among Workers In Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Eligible for Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2018

TAKE-UP RATE

- Seventy-six percent of eligible workers take up coverage when it is offered to them, similar to the percentage last year [Figure 3.1].14 Eligible workers in large firms (200 or more workers) are more likely to take up coverage when offered than eligible workers in small firms (3-199 workers) (78% vs. 73%) [Figure 3.3].

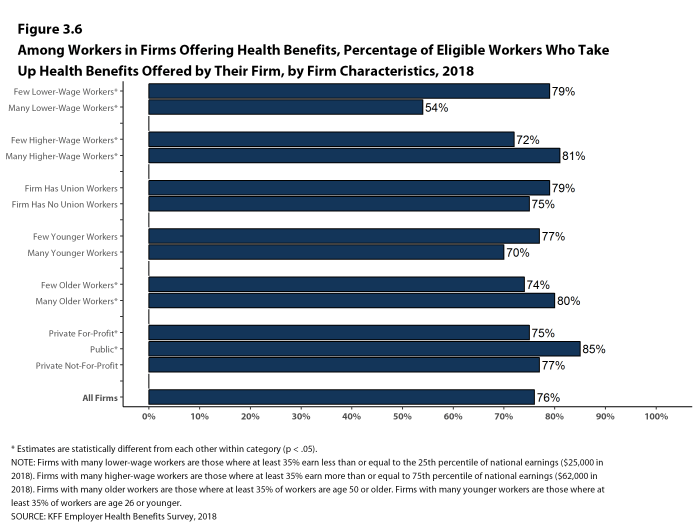

- The likelihood of a worker accepting a firm’s offer of coverage varies by firm wage level. Eligible workers in firms with a relatively small share of lower-wage workers are more likely to take up coverage than eligible workers in firms with a larger share of lower-wage workers (79% vs. 54%) [Figure 3.6].

- Eligible workers in firms with a relatively large share of higher-wage workers are more likely to take up coverage than those in firms with a smaller share of higher-wage workers (81% vs. 72%) [Figure 3.6].

- Eligible workers in firms with a relatively large share of older workers (where at least 35% of the workers are age 50 or older) are more likely to take up coverage than those in firms with a smaller share of older workers (80% vs. 74%) [Figure 3.6].

- The percentage of eligible workers taking up benefits in offering firms also varies considerably by industry. The average take-up rate is lower in agriculture/mining/construction firms (67%) than firms of other industries [Figure 3.3].

- The share of eligible workers taking up benefits in offering firms (76%) has decreased over time, from 80% in 2013 and 82% in 2008 [Figure 3.1].

Figure 3.6: Among Workers In Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Eligible Workers Who Take Up Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2018

COVERAGE

- In 2018, the percentage of workers at firms offering health benefits covered by their firm’s health plan is 60%, similar to the percentage last year [Figures 3.1 and 3.2].

- The coverage rate at firms offering health benefits is the same for small firms and large firms in 2018. These rates are similar to the rates last year for both small firms and large firms [Figure 3.1].

- There is significant variation by industry in the coverage rate among workers in firms offering health benefits. The average coverage rate is particularly low in retail (35%) and service (55%) industries [Figure 3.3].

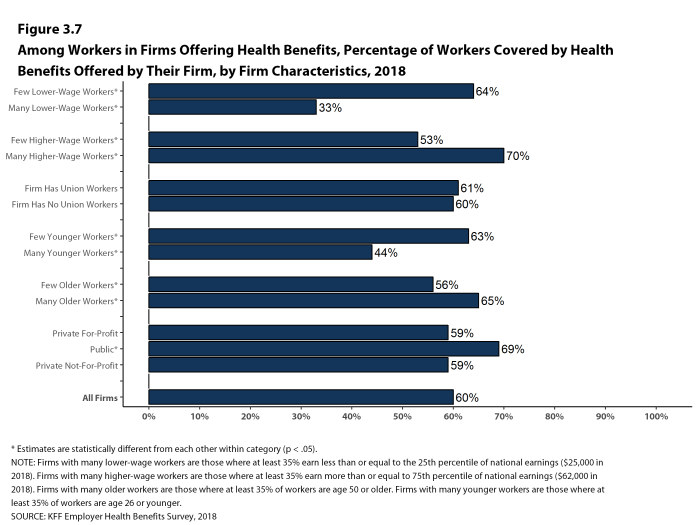

- There also is variation by firm wage levels. Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with a relatively large share of lower-wage workers are much less likely to be covered by their own firm than workers in firms with a smaller share of lower-wage workers (33% vs. 64%). A comparable pattern exists in firms with a relatively large share of higher-wage workers, with workers in these firms being more likely to be covered by their employer’s health benefits than those in firms with a smaller share of higher-wage workers (70% vs. 53%) [Figure 3.7].

- The age profile of workers is also related to variation in coverage rates. Among workers in firms offering health benefits, those in firms with a relatively small share of younger workers are more likely to be covered by their own firm than those in firms with a larger share of younger workers (63% vs. 44%). Similarly, workers in offering firms with a relatively large share of older workers are more likely to be covered by their own firm than those in firms with a smaller share of older workers (65% vs. 56%) [Figure 3.7].

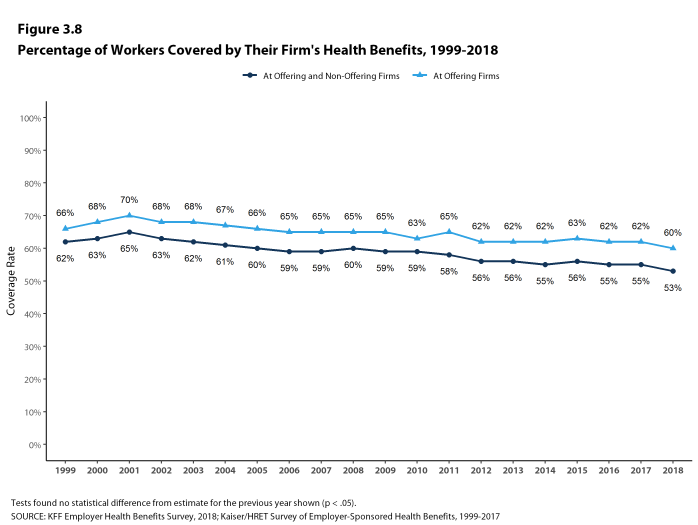

- Among workers in all firms, including those that offer and those that do not offer health benefits, 53% are covered by health benefits offered by their employer, similar to last year, but lower than the coverage rate in 2008 (60%) [Figure 3.8].

Figure 3.7: Among Workers In Firms Offering Health Benefits, Percentage of Workers Covered by Health Benefits Offered by Their Firm, by Firm Characteristics, 2018

Figure 3.8: Percentage of Workers Covered by Their Firm’s Health Benefits, 1999-2018

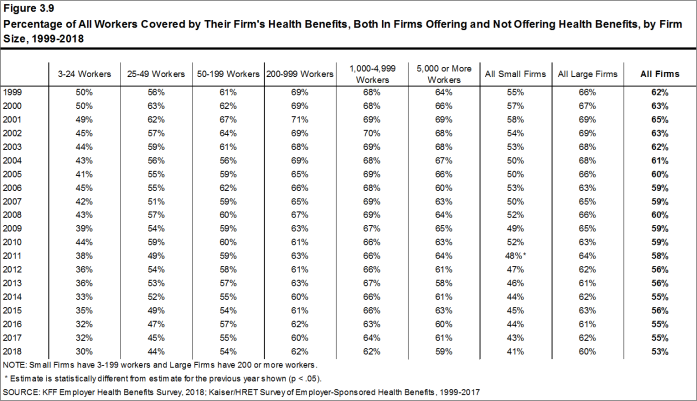

Figure 3.9: Percentage of All Workers Covered by Their Firm’s Health Benefits, Both In Firms Offering and Not Offering Health Benefits, by Firm Size, 1999-2018

WAITING PERIODS

- Waiting periods are a specified length of time after beginning employment before workers are eligible to enroll in health benefits. With some exceptions, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires that waiting periods cannot exceed 90 days.15 For example, employers are permitted to have orientation periods before the waiting period begins which, in effect, means a worker is not eligible for coverage three months after being hired. If a worker is eligible to enroll on the 1st of the month after three months of employment, this survey rounds up and considers the firm’s waiting period four months. For these reasons, some employers still have waiting periods exceeding the 90-day maximum.

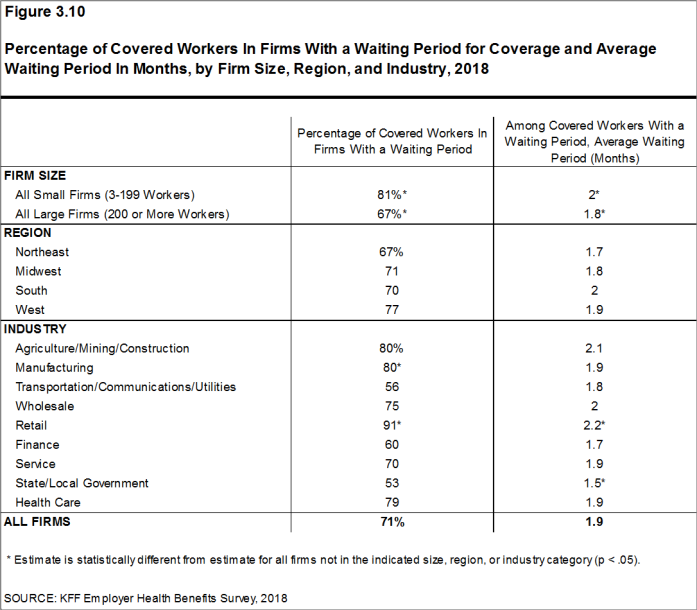

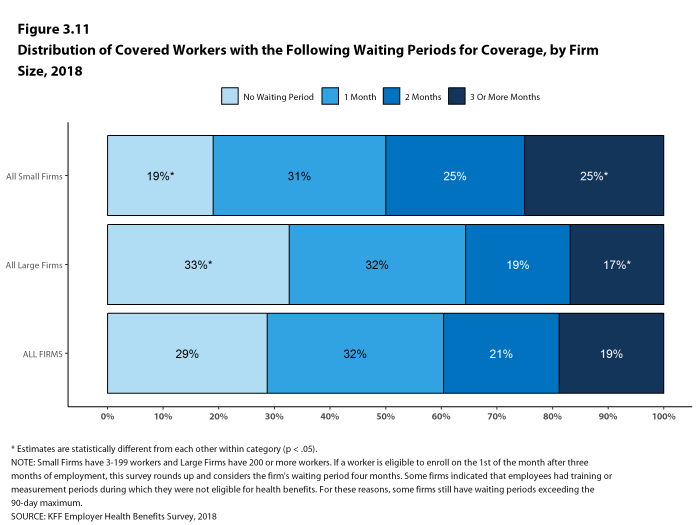

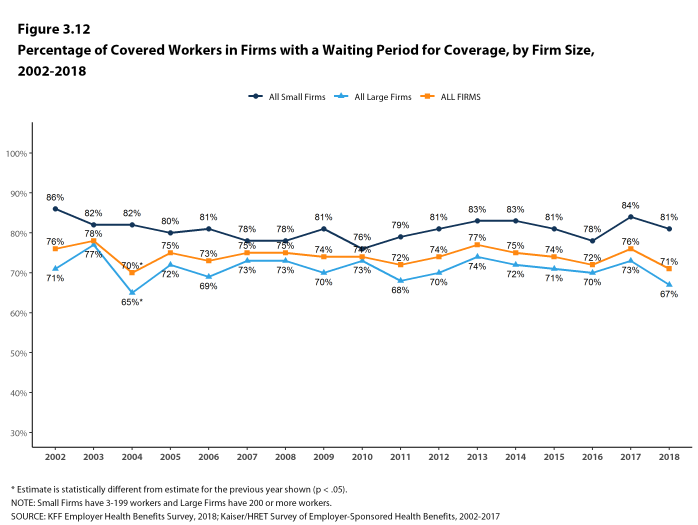

- Seventy-one percent of covered workers face a waiting period before coverage is available, similar to last year [Figure 3.12]. Covered workers in small firms are more likely than those in large firms to have a waiting period (81% vs. 67%) [Figure 3.10].