Low-income Californians and Health Care

Introduction

Introduction

Despite its large economy, California is also the state with the highest poverty rate (19 percent) according to the U.S. Census Bureau.1 As Governor Gavin Newsom begins his tenure in office, Californians across income groups see health care as a key issue for the new governor and legislature to address. In late 2018, the Kaiser Family Foundation and the California Health Care Foundation conducted a representative survey of the state’s residents to gauge their views on health policy priorities and their experiences in California’s health care system. This summary examines key findings from the survey among “low-income” Californians, defined here as those whose self-reported incomes are below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (approximately $49,000 for a family of four). Where relevant, they are compared to higher-income Californians — those with self-reported incomes at or above 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Half of low-income Californians say that someone in their family has delayed or forgone medical or dental treatment in the past year due to costs, this @KaiserFamFound / @CHCFNews survey finds.

Overall, the survey finds that while Californians at all income levels see health care as an important priority for the governor and legislative leaders to work on, health care affordability and access emerge as particularly prominent concerns among low-income residents of the state. Key findings include:

- Affordability of health care has affected treatment decisions for many low-income Californians, with over half saying that in the past year, they or someone in their family has delayed or forgone some type of medical or dental treatment due to costs.

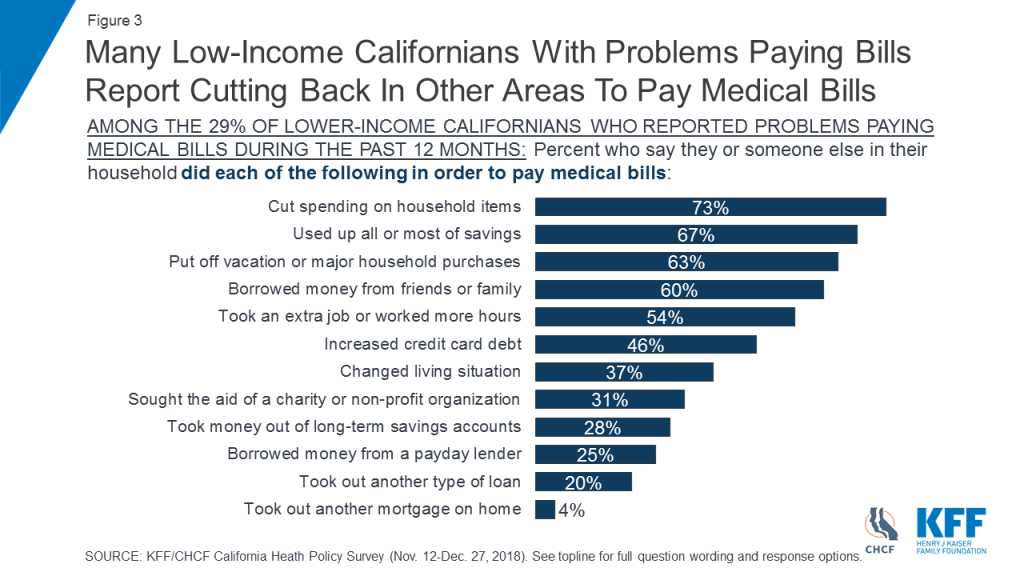

- Californians with low incomes are almost twice as likely as higher-income residents to say they have had problems paying medical bills. As a result, many of those who experienced difficulty paying medical bills say they have had to cut back spending in other areas, use savings, or borrow money.

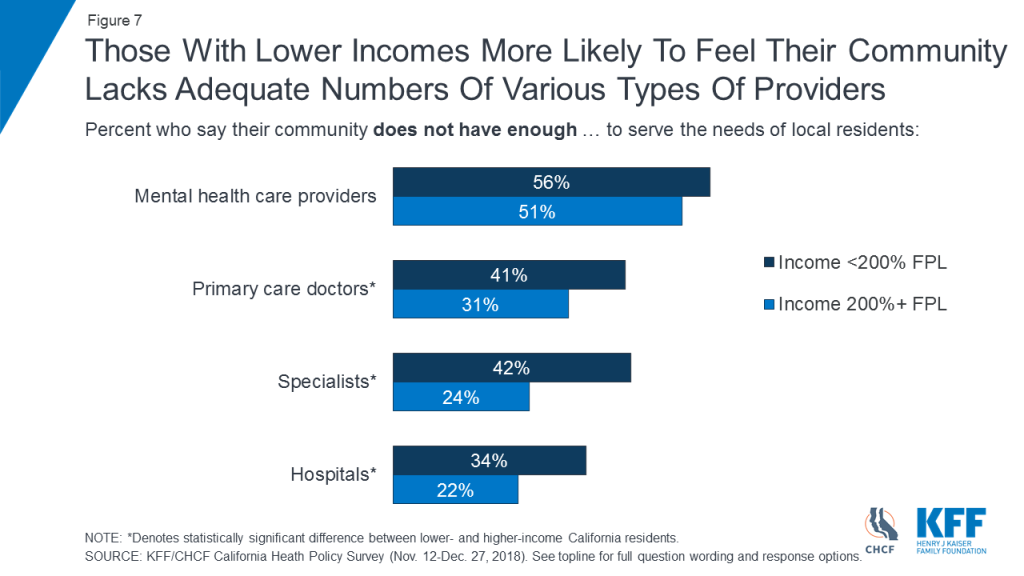

- Low-income Californians are also more likely than other residents to report nonfinancial barriers to accessing health care, such as long wait times to get an appointment. A majority of Californians with low incomes say their community does not have enough mental health providers, and about four in ten say their community lacks enough primary care doctors and specialists to meet the needs of residents.

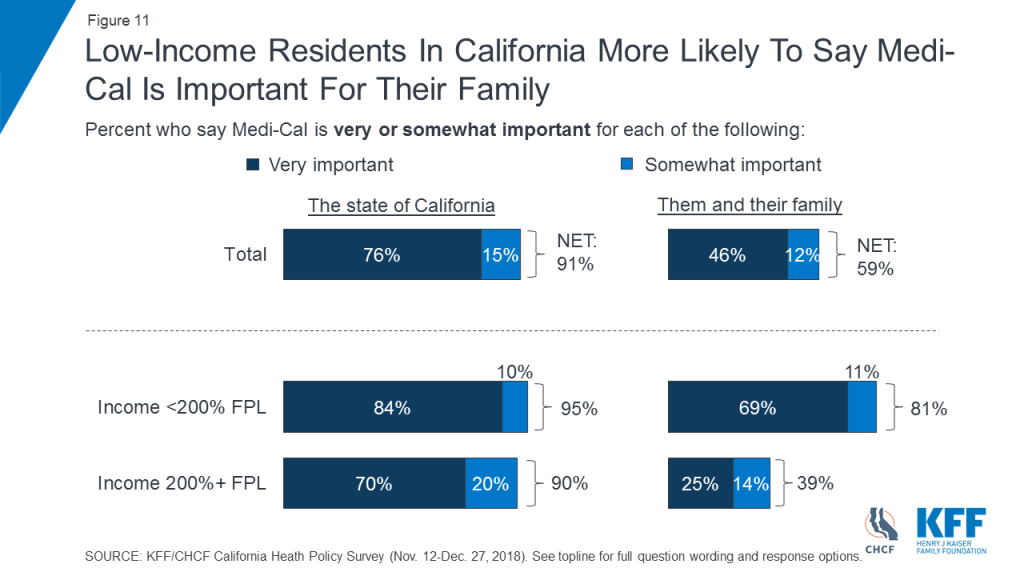

- The distinctive health care experience of low-income Californians is also evident in their attitudes toward Medi-Cal. While overwhelming majorities of Californians across income levels say Medi-Cal is important to the state, low-income Californians are twice as likely as those with higher incomes to say the program is important to them and their families.

Findings

Health Care Priorities

When asked about a number of health care issues facing the state and its residents, Californians with low incomes say most are important priorities for state political leaders to address. About half of low-income Californians say that it is “extremely important” for the governor and the legislature to work on making sure people with mental health problems can get treatment (51 percent) and to work on making sure all Californians have access to health insurance (49 percent). Nearly half say it is “extremely important” that the governor and legislature work on lowering the amount people pay for health care (46 percent) and on making sure there are enough health care providers across the state (46 percent). Sixteen percent of Californians with low incomes think it is “extremely important” for state leaders to work on decreasing state spending on health care (Figure 1). While ratings of health care priorities are similar across income levels, Californians with low self-reported incomes are more likely than those with higher incomes to say making sure there are enough health care providers across the state should be an “extremely important” priority for state leaders (46 percent versus 33 percent [not shown]).

Experiences with Health Care Affordability

Californians with low incomes are nearly twice as likely as those with higher incomes to say they or a household member had problems paying medical bills in the past 12 months (29 percent versus 15 percent) (Figure 2).

Many Californians with low incomes who had problems paying medical bills report having to cut back in other areas, dip into savings, or borrow money to help address their medical costs. Among the 29 percent of low-income Californians who report problems paying medical bills, nearly three-quarters (73 percent) say they have cut spending on household items to pay medical bills. Two-thirds (67 percent) say they used up all or most of their savings and about six in ten say they put off a vacation or major purchase (63 percent) or borrowed money from friends or family (60 percent) (Figure 3).

More than half of Californians with low incomes (55 percent) say that they or a family member living in their household delayed or went without some type of medical or dental care in the past year because they had difficulty affording the cost. This compares to 36 percent of those with higher incomes (not shown). Four in ten low-income Californians say someone in their household skipped dental care or checkups, 28 percent say they or a household member put off or postponed getting health care, and about a quarter say someone in their household skipped a recommended test or treatment (24 percent) or did not fill a prescription (24 percent) because of cost (Figure 4).

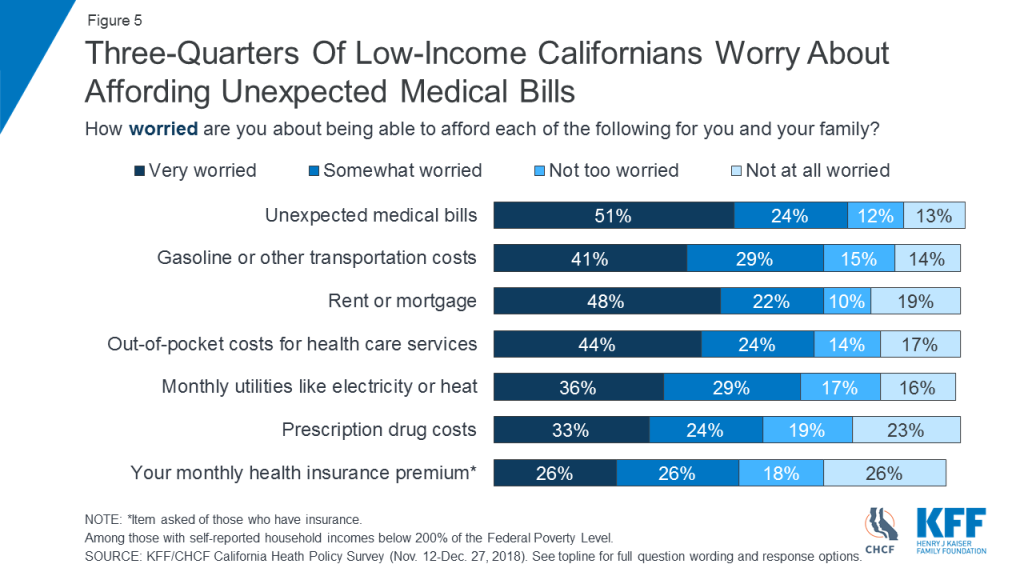

Three in four low-income Californians (75 percent) say they are very or somewhat worried about being able to afford unexpected medical bills, outranking other financial worries asked about in the survey, including paying for housing. Nearly seven in ten (68 percent) say they are worried about affording out-of-pocket costs for health care services (Figure 5).

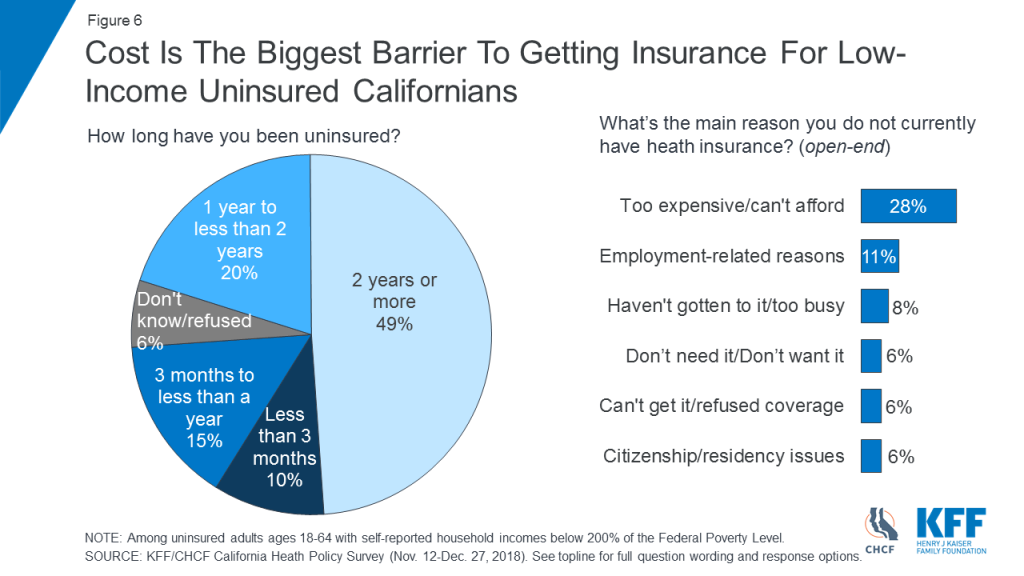

Cost concerns are also evident among low-income adults who are uninsured. Among uninsured Californians age 18–64 with low incomes, about half (49 percent) say they have been without health insurance for two years or more, and cost and affordability (28 percent) is the top reason cited for why they lack insurance (Figure 6).

Access to Providers

A majority of low-income Californians (56 percent) say their community does not have enough mental health care providers to serve the needs of local residents. Those with low incomes are more likely than Californians with higher incomes to say their community does not have enough primary care doctors (41 percent versus 31 percent), specialists (42 percent versus 24 percent), and hospitals (34 percent versus 22 percent) (Figure 7).

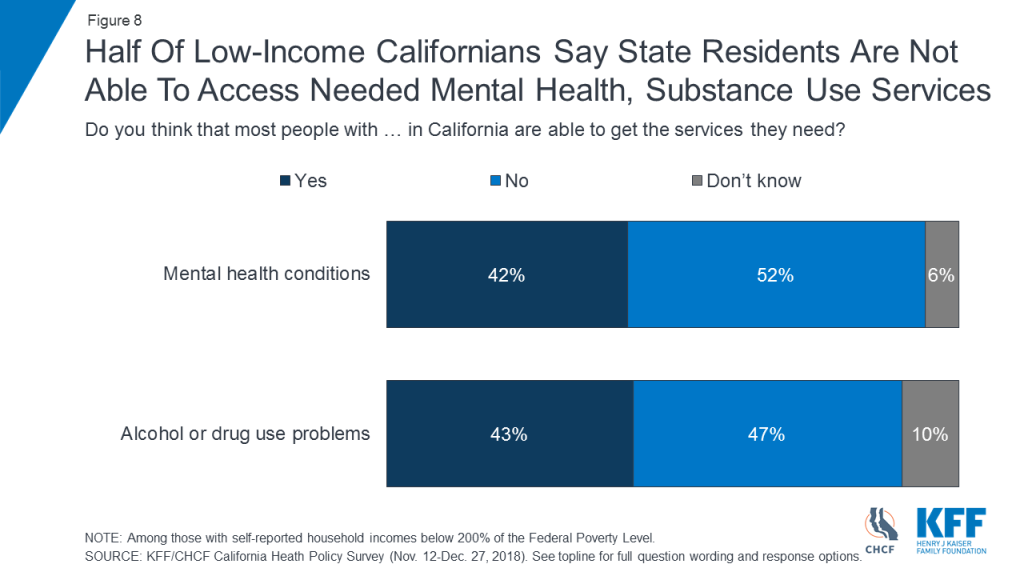

About half of Californians with low incomes (52 percent) say most people in the state with mental health conditions are not able to get the services they need. A similar share (47 percent) say those with alcohol or drug use problems in California are not able to get needed services (Figure 8).

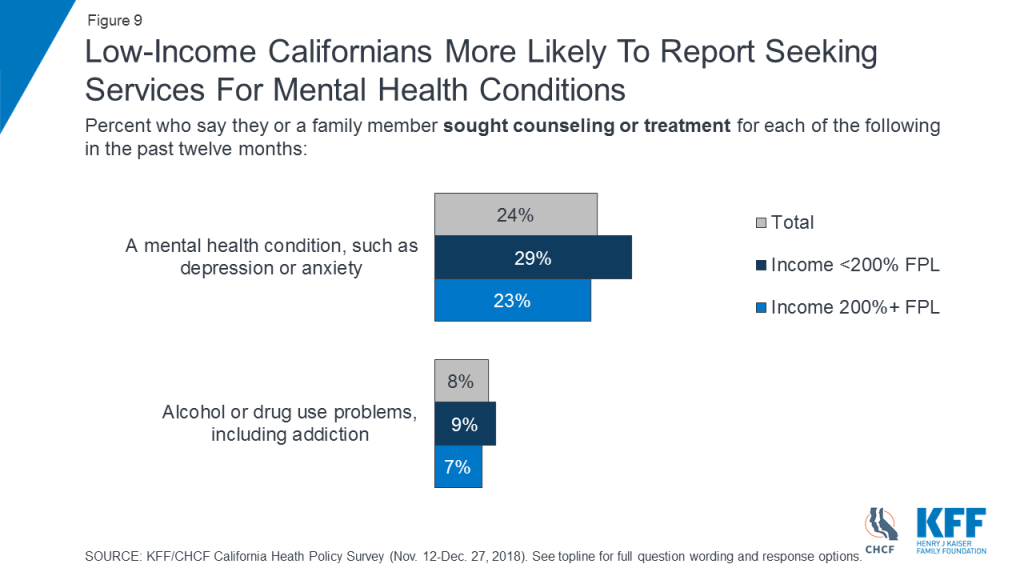

Similar shares of Californians across income levels say they or a family member have sought counseling or treatment for alcohol or drug use (Figure 9).

Californians with low incomes are slightly more likely than those with higher incomes to say they or a family member sought counseling or treatment for a mental health condition, such as anxiety or depression, in the past twelve months (29 percent versus 23 percent) (Figure 9).

Among Californians with low incomes, concerns about availability and access to providers are reflected in their personal experiences. About a quarter of low-income residents (27 percent) say there was a time in the past 12 months when they had to wait longer than they thought reasonable to get an appointment for medical care. Among low-income adults who say they or a family member sought mental health treatment in the past year, 27 percent said they had to wait longer than they thought reasonable for a mental health care appointment (Figure 10).

Among low-income Californians with Medi-Cal coverage who say they or a family member sought care, 33 percent report having to wait longer than they thought reasonable for a medical care appointment and four in ten (41 percent) say they had to wait longer than reasonable for a mental health care appointment (Figure 10).

Importance of Medi-Cal

An overwhelming majority of low-income Californians say Medi-Cal is “very important” (84 percent) or “somewhat important” (10 percent) to the state. Eight in ten (81 percent) say it is either “very important” (69 percent) or “somewhat important” (11 percent) to them and their family. While an overwhelming majority of Californians with higher incomes also see Medi-Cal as important to the state (90 percent), they are less likely than those with low incomes to say the program is important to their own families (39 percent versus 81 percent) (Figure 11).

Survey Methodology

The Kaiser Family Foundation/California Health Care Foundation California Health Policy Survey was conducted by telephone November 12 – December 27, 2018, among a random representative sample of 1,404 adults age 18 and older living in the state of California (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Figures in the report may not add to 100 due to rounding. Interviews were administered in English and Spanish, combining random samples of both landline (476) and cellular telephones (928, including 668 who had no landline telephone). Sampling, data collection, weighting and tabulation were managed by SSRS in close collaboration with Kaiser Family Foundation and California Health Care Foundation researchers. The California Health Care Foundation paid for the costs of the survey fieldwork, and Kaiser Family Foundation contributed the time of its research staff. Both partners worked together to design the survey and analyze the results.

The sampling and screening procedures were designed to increase the number of Black and Asian-American respondents and low-income respondents, including those who have health insurance through Medi-Cal or who are uninsured. This oversample allowed for sufficient numbers of respondents in these subgroups to report their results separately; weighting adjustments were made to adjust their proportions to represent their actual shares of the population in overall results (see weighting description below). The sample included 463 respondents who were reached by calling back respondents in California who had previously completed an interview on either the SSRS Omnibus poll or the Kaiser Health Tracking Polls and indicated they fit one of the oversample criteria (Black, Asian, or low-income respondents, including low-income respondents with Medi-Cal or who are uninsured, and are living in California). It also included 46 respondents with prepaid (or pay-as-you-go) cell phone numbers in California, a group that is disproportionately lower-income.

The dual frame cellular and landline phone sample was generated by Marketing Systems Group (MSG) using random digit dial (RDD) procedures. The RDD frames were stratified by income-level in order to reach more low-income respondents. To address the fact that some qualifying respondents could be reached only by their cell-phone but had an out-of-state phone number, the sample was augmented with a sample of phone numbers outside of California associated with a billing address that indicated in-state residence (n=89). Survey Sampling International (SSI) generated these numbers randomly using Smart Cell sample. All respondents were screened to verify that they resided in California. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the qualifying adult who answered the phone.

A multi-stage weighting design was applied to ensure an accurate representation of the California adult population. The first stage of weighting involved corrections for sample design, including accounting for the components, the likelihood of non-response for the re-contacted sample, and an adjustment to account for the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection. In the second weighting stage, demographic adjustments were applied, at first, to the RDD and Smart Cell sample to account for systematic non-response along known population parameters. Population parameters included gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity (broken down by nativity), educational attainment, phone status (cell phone only or reachable by landline), and state region. Demographic parameters were based on estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), and telephone use was based on data for California from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. Based on this second stage of weighting, estimates were derived for self-reported income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (less than 200%, 200% or higher) by insurance status (Medi-Cal, uninsured, all else) in the California population. The last stage of weighting included all respondents and used poverty level by insurance status, based on the previous stage’s outcomes, as an additional weighting parameter.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of interviews and margins of sampling error for the subgroups analyzed in this report are shown in the table below. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E |

| Total | 1,404 | ±3 percentage points |

| <200% FPL | 724 | ±4 percentage points |

| 200% FPL+ | 553 | ±5 percentage points |

| <200% FPL & Medi-Cal (<65) | 281 | ±7 percentage points |

| <200% FPL & Uninsured (<65) | 125 | ±10 percentage points |

Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Endnotes

- The supplemental poverty measure takes into account government programs which assist low-income individuals and expenditures of food, clothing, shelter, and utilities. Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2017. (September 2018). Retrieved April 2019, from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-265.pdf ↩︎