Key State Policy Choices About Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services

Executive Summary

Medicaid continues to be the primary payer for long-term services and supports (LTSS), with these services typically unavailable or unaffordable through Medicare or private insurance. State Medicaid programs must cover LTSS in nursing homes, while most home and community-based services (HCBS) are optional, which results in considerable differences among states in HCBS eligibility, scope of benefits, and delivery systems. This issue brief illustrates current variation and trends in Medicaid HCBS state policy choices, using the latest data (FY 2018) from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s 18th annual 50-state survey. A related brief presents state-level HCBS enrollment and spending data. Key findings include:

State HCBS programs reflect states’ substantial flexibility in choosing among optional authorities.

- States have flexibility to target HCBS to certain populations. All states serve people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD), seniors, and adults with physical disabilities through HCBS waivers, while fewer states offer waivers for people with traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries (TBI/SCI), children who are medically fragile, people with mental illness, and those with HIV/AIDS. People with mental illness and those with I/DD are the populations most commonly served under Section 1915 (i) programs, which provide HCBS to people with functional needs below an institutional level of care.

- States generally use the same income and functional eligibility criteria for HCBS waivers and institutional care, placing access to HCBS on equal footing with nursing homes. Over three-quarters of states set HCBS waiver income limits at the federal maximum, and a notable minority of HCBS waivers do not include an asset limit.

- Medicaid HCBS benefit packages vary, reflecting the optional nature of most HCBS. Two-thirds of states offer the personal care state plan option, while fewer elect other optional state plan authorities. All states offer at least one HCBS waiver, with home-based services and equipment/technology/modifications as the most commonly offered waiver benefits across states and target populations. Waivers targeting seniors and/or adults with physical disabilities and people with TBI/SCI are the most likely to offer enrollees the option to self-direct services, while waivers serving people with mental illness are least likely to do so.

- Over three-quarters of states report an HCBS waiver waiting list. Waiting list enrollment totals nearly 820,000 people nationally with an average wait time of 39 months. All individuals on waiting lists ultimately may not be eligible for waiver services. Notably, the eight states that do not screen for waiver eligibility before placing an individual on a waiting list comprise 61% of the total waiting list population.

- All states monitor HCBS waiver quality, but no standardized measure set is used across programs. Most states measure beneficiary quality of life and/or community integration, while about half use an LTSS rebalancing measure.

Over half of states have capitated managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) programs.

- Most states already have adopted policies to follow the 2016 changes in the federal Medicaid managed care rule. For example, over three-quarters of capitated MLTSS states have network adequacy standards for HCBS providers, with time and distance as the most common.

- Value-based payment for HCBS is an emerging area of interest. Over one-quarter of capitated MLTSS states currently use VBP models, and more states are planning to do so.

States are working to implement new policies in response to federal laws and regulations affecting HCBS.

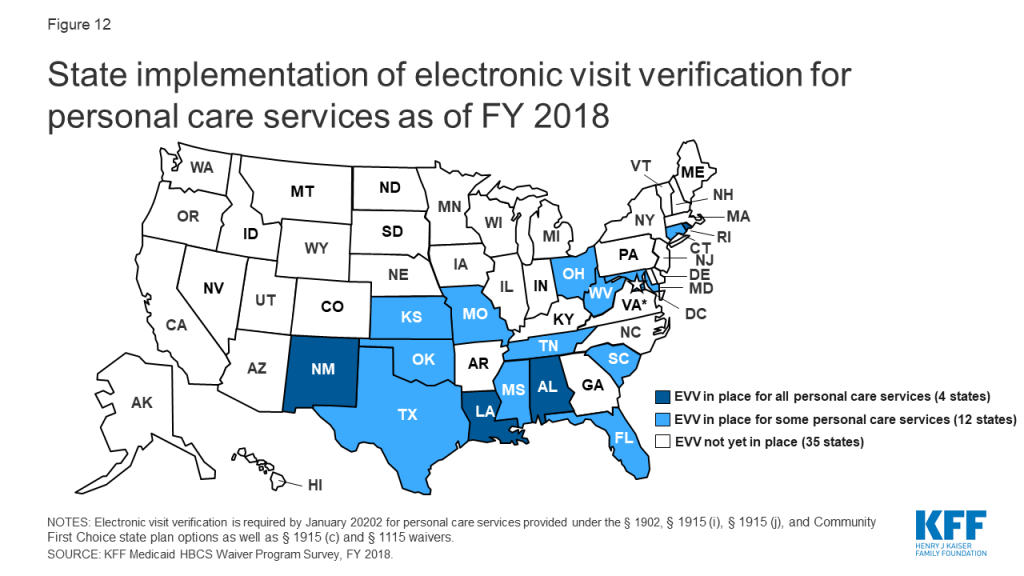

- Few states have fully implemented electronic visit verification (EVV) systems to date, with a majority of states reporting challenges in this area. EVV is required for personal care services in January 2020, and home health services in January 2023, though states can seek a one year exemption.

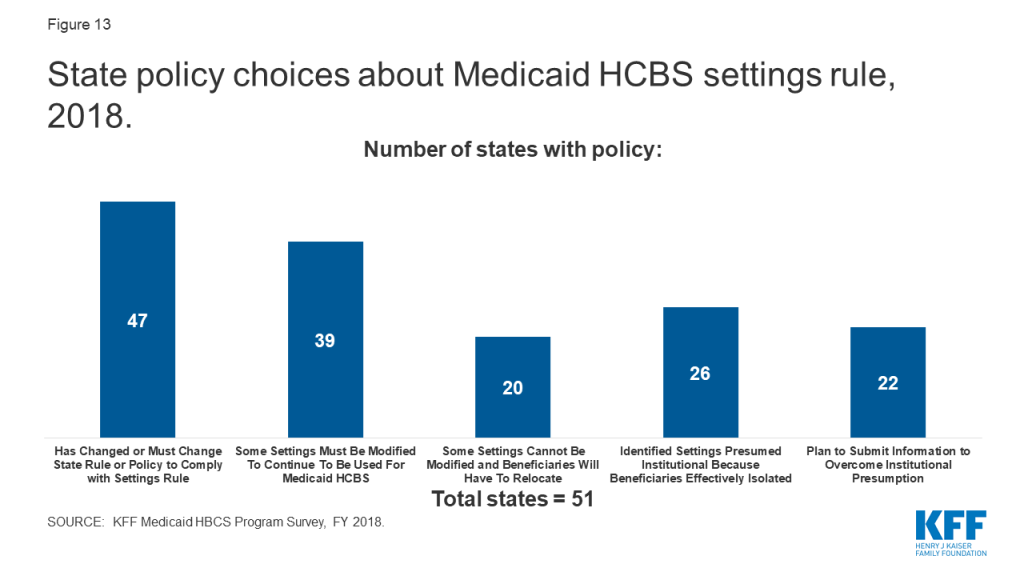

- Nearly all states already have or plan to change policy to meet CMS’s home and community-based settings rule. Most changes relate to settings that must be modified to continue to be used for Medicaid-funded HCBS, while 20 states have identified settings that cannot be modified and will require beneficiaries to relocate.

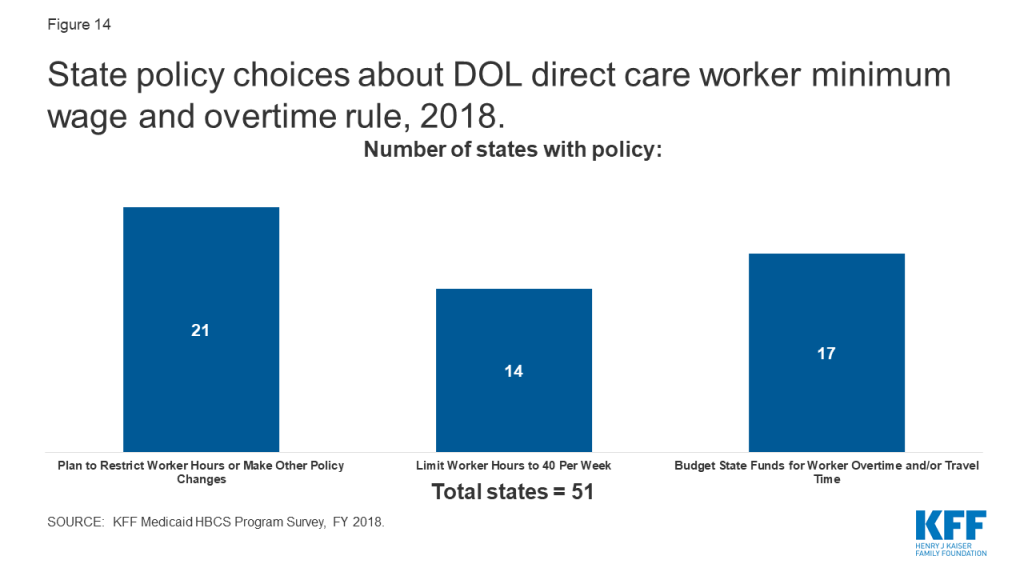

- Less than half of states already have or plan to restrict direct care worker hours or make other policy changes in response to the U.S. Department of Labor minimum wage and overtime rules. One-third of states have budgeted funds for worker overtime and/or travel time.

States will face increasing pressure to meet the health and LTSS needs of a growing elderly population in the near future. Understanding the variation in Medicaid HCBS state policies is important for analyzing the implications of this demographic change as well as the implications of a range of policy changes that could fundamentally restructure federal Medicaid financing or the larger U.S. health care system. For example, substantially cutting and capping the federal Medicaid funds available to states through a block grant or per capita cap could put pressure on states to eliminate optional covered populations and services, such as those that authorize and expand the availability of HCBS. While all states could face challenges in this scenario to varying degrees, those with certain characteristics – such as existing restrictive Medicaid policies; demographics like poverty, old age, or poor health status that reflect high needs; high cost health care markets; or low state fiscal capacity – could face greater challenges. On the other hand, moving to a Medicare-for-all system would eliminate existing state variation in favor uniform coverage of HCBS for all Americans. Unlike Medicaid, HCBS would be required and explicitly prioritized over institutional services under current Medicare-for-all proposals. As these policy debates develop, there will be continued focus on Medicaid’s role in providing HCBS for seniors and people with disabilities.

Issue Brief

Introduction

State Medicaid programs must cover long-term services and supports (LTSS) provided in nursing homes, while most home and community-based services (HCBS) are optional.1 Joint federal and state Medicaid spending across the main HCBS authorities totaled $92 billion in FY 2018, with most spending and enrollment in optional authorities.2 In addition to choosing which HCBS to offer, states have flexibility to determine a number of policies that shape these benefits in important ways for the seniors and people with disabilities and chronic illnesses who rely on them to live independently in the community.

This issue brief presents the latest (FY 2018) data on key state policy choices from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s 18th annual survey of Medicaid HCBS programs in all 50 states and DC. Our survey encompasses home health, personal care, Community First Choice, and Section 1915 (i) state plan benefits as well as Section 1915 (c) and Section 1115 waivers (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1). We include findings related to state choices about scope of benefits, self-direction, capitated managed care delivery systems, provider policies and reimbursement rates, financial and functional eligibility criteria, HCBS waiver waiting lists and other utilization controls, and quality measures. We also report on state progress in implementing notable regulations, including the LTSS provisions in the Medicaid managed care rule, the electronic visit verification rule, the home and community-based settings rule, and the U.S. Department of Labor direct care worker minimum wage and overtime rule. Appendix Tables contain detailed state-level data. A related brief presents the latest state-level Medicaid HCBS enrollment and spending data.

Home Health State Plan Benefit Policies

All states offer home health state plan services, the only HCBS that is not provided at state option. At minimum, the home health state plan benefit includes nursing services, home health aide services, and medical supplies, equipment, and appliances. Home health aides typically assist individuals with self-care tasks, such as bathing or eating. While all state Medicaid programs must offer home health state plan services, states have substantial flexibility in designing this benefit. Key state home health policy choices are described below and summarized in Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2.

Nearly all states choose to expand the scope of their home health state plan benefit by including optional therapy services (physical, occupational, and/or speech-language) (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2). Oklahoma is the only state that does not cover any form of optional therapy services as part of its home health state plan benefit. A minority of states choose to include assistance with household activities, such as preparing meals or housekeeping, within their home health state plan benefit. A dozen states cover other optional services within their home health state plan benefit, such as social work, counseling, nutrition/dietitian services, case management, telehealth (remote monitoring), and emergency support/caregiver respite (no data shown).

Few states allow beneficiaries to self-direct home health state plan services (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2). Self-direction typically allows beneficiaries to select and dismiss their direct care workers, determine worker schedules, set worker payment rates, and/or allocate their service budgets. The states that offer self-direction for home health state plan services are California, Nebraska,3 and New Jersey. States may be less likely to offer self-direction for home health services compared to personal care services (discussed below) at least in part because home health services may be used by some beneficiaries for shorter periods of time. Nebraska is the only state that allows self-direction for home health services but not for personal care services (Appendix Tables 2 and 3).

Just over half of states apply utilization controls to their home health state plan benefit (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2). Specifically, 25 states cap the number of home health service hours or visits that a beneficiary can receive, and three states cap the daily amount that can be spent on home health services for an individual. Among states applying utilization controls, all choose either hour/visit caps or spending caps, except Oregon, which applies both types of utilization controls. Thirteen states allow exceptions to their hour/visit limits, while two states (AK and RI) do not.4 Among the three states that offer self-direction for home health services, two (CA and NJ) apply their hour/visit limits to both self-directed and other (e.g., agency-provided) services, while Nebraska does not apply its cost cap to self-directed services. Applying hour or cost caps to self-directed services can have implications for beneficiary access to needed service hours as well as the direct care worker overtime rule (discussed below).

Ten states require a copayment for home health state plan services (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 2).5 Copayment amounts range from $1 to $4 per visit,6 with most states (7 of 10) charging about $3.7 Maine’s copayments are capped at $30 per month, while South Carolina and Virginia note that if more than one home health service is provided on the same day, the individual is only assessed one copay. Kansas’s copayment applies only to individuals enrolled in fee-for-service Medicaid (about 2% of the population) and not to those enrolled in a capitated managed care plan.

Over half of states deliver some or all home health state plan services through capitated managed care (Figure 2).8 A Section 1115 demonstration waiver is the most frequently used Medicaid managed care authority for these services (12 states), while fewer states use a Section 1915 (b) managed care waiver (5 states), the Section 1932 managed care state plan option (4 states), or a combination of Medicaid managed care authorities (5 states) (no data shown).9

The average provider reimbursement rate for home health agency services is $102.85 per visit (Appendix Table 2).10 Agency reimbursement rates account for a range of home health providers, such as registered nurses; home health aides; physical, occupational, and speech-language therapists; and social workers. In the 37 states with direct payment or mandated rates for registered nurses providing home health services, the average rate per visit is $89.89.11 In the 39 states with direct payment or mandated rates for home health aides, the average rate per visit is $46.80.12

Personal Care State Plan Benefit Policies

Thirty-four states offer personal care services as an optional state plan benefit (Appendix Table 3). Delaware discontinued its personal care state plan benefit in FY 2018, and instead now covers those services under its home health state plan benefit.13 Personal care services “may include a range of human assistance. . . [that] enables [individuals] to accomplish tasks that they would normally do for themselves if they did not have a disability.”14 These services typically assist individuals with self-care tasks, such as eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, and maintaining continence, and household activities, such as personal hygiene, light housework, laundry, meal preparation, transportation, grocery shopping, using the telephone, medication management, and money management.15 The scope of personal care services “may be in the form of hands-on assistance (actually performing a personal care task for a person) or cuing so that the person performs the task by him/herself.”16 Key state policy choices about personal care state plan benefits are summarized in Figure3 and Appendix Table 3 and described below.

All states (of 32 responding)17 that elect the personal care state plan option include assistance with self-care activities, and most include homemaker/chore services to assist with household activities. Over half of personal care states cover cueing or monitoring, in addition to hands-on assistance (Figure 3). Fifteen states provide transportation as part of their personal care benefit, and a dozen include tasks delegated by a nurse, such as injections (no data shown). About one-third of states cover other services within their personal care state plan benefit, such as respite, case management, medical escort, life skills training,18 and assistive technology (no data shown).

In addition to a beneficiary’s residence, about three-quarters of states electing the personal care state plan option offer services at an individual’s work site (Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3). Two-thirds of personal care states provide services elsewhere in the community outside of a home or work setting. Providing services at a work site or elsewhere in the community can increase the extent to which beneficiaries are integrated into the community. About one-third of personal care states provide services at other residential settings, such as residential care, foster care, or assisted living facilities; the residence of family or friends; or dormitories for full-time students (no data shown). California allows for services to be provided out-of-state on a limited basis, to enable individuals to go on vacation or attend a funeral.

Over half of personal care states allow individuals to self-direct these services (Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3), almost seven times the number that do so for home health state plan services. As noted above, self-direction typically allows beneficiaries to select and dismiss their direct care workers, determine worker schedules, set worker payment rates, and/or allocate their service budgets.

Over one-third of personal care states allow individuals to choose among both agency and independent providers, while few states allow legally responsible relatives to be paid providers (Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3). Covering more provider types can help to increase access to personal care services, which is especially critical as individuals often rely on these services for basic daily needs. Just under half of personal care states cover only agency providers, and three states (CA, MA and VT) offer only independent providers. The states that allow legally responsible relatives, such as a spouse or parent, to be paid providers are Alaska,19 California, Louisiana,20 Minnesota, and Oregon.

Nearly all personal care states use a standardized assessment tool to determine functional needs for personal care state plan services. The two states that do not base the functional needs assessment on a standardized tool are New Hampshire and Utah. Among states using a standardized assessment tool, 25 describe it as a state-specific or “another” tool,21 while five states report using the Inter-RAI tool (LA, MD, MO, NM and SD).

Just under half of personal care states rely on a state or local government agency to perform the functional needs assessment for personal care state plan services. Two states (CO and WI) rely on health care providers to assess functional needs; one state (NJ) relies on managed care plans; and one state (VT) uses community-based organizations. The remaining dozen states use “another entity,” which could include a combination of state staff and providers, community-based organizations, and/or health plans. Nearly three-quarters of personal care states have an exceptions process if individuals disagree with the assessment results (no data shown).

Over half of personal care states apply utilization controls to these services (Figure 3 and Appendix Table 3), while one state requires a copayment. Among the states with utilization controls, 20 cap the number of hours that an individual can receive, and two states (FL and MO) cap the amount spent on personal care services that an individual can receive. All states with utilization controls choose either hour or cost caps, except Florida, which applies both. Among the 11 states with hourly caps that also allow self-direction, seven (AR, ID, MI, MN, MT, NV, and NJ) apply hourly caps to both self-directed and other (e.g., agency-provided) services, three (DC, MA, and VT) apply hourly caps only to self-directed services, and one (CA) applies hourly caps only to non-self-directed services. Applying hourly caps to self-directed services can have implications for beneficiary access to needed service hours as well as the direct care worker overtime rule (discussed below). Maine is the only state that requires a copayment, of $3 per day (capped at $30/month), for personal care state plan services.

Over one-third of personal care states deliver some or all of these services through capitated managed care.22 States’ choice of Medicaid managed care authority varies, with three states using a Section 1115 demonstration waiver, three states using the Section 1932 managed care state plan option, two states using a Section 1915 (b) managed care waiver, one state using Section 1915 (a) managed care authority, and three states using a combination of managed care authorities (no data shown).

The average provider reimbursement rate paid to personal care agencies is $19.90 per hour (Appendix Table 3).23 In the 15 states that report paying personal care service providers directly or mandating their reimbursement rates, the average rate is $17.26 per hour.

Community First Choice State Plan Benefit Policies

Eight states offer attendant services and supports under the Community First Choice (CFC) state plan option (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1).24 These states include CA, CT, MD, MT, NY, OR, TX, and WA. States providing CFC services receive enhanced federal matching funds at an additional six percent. Key state policy choices about CFC financial eligibility and services are described below.

Nearly all CFC states choose to expand financial eligibility to beneficiaries who qualify for Medicaid under an HCBS waiver.25 All states electing the CFC option must provide services to individuals who either (1) are eligible for Medicaid in a state plan coverage group that includes nursing home services in the benefit package, or (2) have income at or below 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL, $18,735/year for an individual in 2019).26 States can choose to expand CFC eligibility to individuals who are eligible for Medicaid under an HCBS waiver; these waivers (described below) enable states to expand Medicaid financial eligibility up to 300% SSI ($27,756/year for an individual in 2019).27 Montana is the only CFC state that does not opt to expand financial eligibility to individuals who qualify for Medicaid under an HCBS waiver. In addition to meeting financial eligibility criteria, individuals receiving CFC services must have functional needs that would otherwise require an institutional level of care.

Half of CFC states choose to offer additional services beyond the minimum CFC benefit package. CFC services must include assistance with self-care, household activities, and health-related tasks,28 self-direction opportunities, and back-up systems.29 States also have the option to cover additional CFC services, including institutional to community transition costs30 and supports that increase or substitute for human assistance.31 Four states (CT, MD, OR, and WA) cover both types of optional CFC services, while three states offer the basic CFC benefit package (CA, MT, and TX).32

Section 1915 (i) State Plan Benefit Policies

Eleven states offer the Section 1915 (i) HCBS state plan option in FY 2018, and two more states newly added this option effective in FY 2019 (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1). The 11 Section 1915 (i) states responding to the FY 2018 policy survey include CA, CT, DE, DC, ID, IN, IA, MS, OH, NV, and TX. In addition, Michigan has a new Section 1915 (i) HCBS state plan option, effective October 2018,33 and Arkansas newly elected the Section 1915 (i) HCBS state plan option, effective March 2019. Section 1915 (i) allows states to offer HCBS as part of their Medicaid state plan benefit package instead of through a waiver. Key state policy choices about Section 1915 (i) target populations, services, and eligibility are described below.

People with mental illness and those with intellectual or developmental disabilities (I/DD) are the target populations most commonly served under Section 1915 (i). Like waivers, states can target Section 1915 (i) services to a particular population. Four states (IA, IN, OH, and TX) target people with mental illness, four states (CA, DE, ID, and MS) target people with I/DD, and three states target seniors and/or people with physical disabilities (CT-seniors only, DC, and NV). Three states (ID, IN, and NV) have more than one Section 1915 (i) program serving different sub-populations.34

Home-based services are the most frequently covered type of service across all Section 1915 (i) target populations (in 8 of 10 states reporting)35 (Appendix Table 4). Other frequently covered Section 1915 (i) services include case management (7 states), day services (7 states), supported employment (6 states), and other mental/behavioral health services (6 states). Nursing/therapy services, round-the-clock services, and equipment/technology/modifications are less frequently covered under Section 1915 (i) (4 states), which likely reflects the fact that Section 1915 (i) functional eligibility is less than an institutional level of care. Box 1 lists the nine service categories included in our survey.

Box 1: Service Categories for Section 1915 (i) and Section 1915 (c) HCBS

States provide a range of different HCBS through the Section 1915 (i) state plan option and Section 1915 (c) waivers, which our survey groups into nine categories that reflect CMS’s HCBS Taxonomy:36 (1) case management; (2) home-based services (including personal care, companion services, home health, respite, chore/homemaker services, and home-delivered meals); (3) day services (including day habilitation and adult day health services); (4) nursing/other health/therapeutic services; (5) round-the-clock services (including in-home residential habilitation, supported living, and group living); (6) supported employment/training; (7) other mental health and behavioral services (including mental health assessment, crisis intervention, counseling, peer specialist); (8) equipment/technology/modifications (such as personal emergency response systems, home and/or vehicle accessibility adaptions); and (9) other services (including non-medical transportation, community transition services, payments to managed care, and goods and services).

States’ Section 1915 (i) benefit packages vary by target population (Appendix Table 4). For people with I/DD, home-based services, day services, and supported employment are the most frequently provided Section 1915 (i) services (in 3 of 4 states covering this population), while nursing/therapy and round-the-clock services are the least likely to be covered (1 of 4 states). For people with mental illness, Section 1915 (i) states most frequently provide case management, home-based, and other mental/behavioral health services (3 of 4 states covering this population) and are less likely to provide round-the-clock services and equipment/technology/modifications (1 of 4 states). Home-based services, day services, case management, and round-the-clock services are the most frequently covered Section 1915 (i) services for seniors/people with physical disabilities (2 of 3 states reporting).37

Two states opt to extend Section 1915 (i) financial eligibility to the federal maximum of 300% of SSI for certain individuals. Specifically, Idaho expands financial eligibility for both of its Section 1915 (i) programs (children with I/DD and adults with I/DD), while Indiana expands financial eligibility for one of its three programs (people with mental illness receiving behavioral health and primary care coordination).38 The other nine states provide Section 1915 (i) services to people with income up to 150% FPL. Under Section 1915 (i), states can cover (1) people who are eligible for Medicaid under the state plan up to 150% FPL, with no asset limit, who meet functional eligibility criteria; and also may cover (2) people up to 300% SSI who would be eligible for Medicaid under an existing HCBS waiver.

Idaho began using Section 1915 (i) as an independent Medicaid coverage pathway in FY 2018, joining two other states (IN and OH) electing this option. Idaho applies this policy to one of its two Section 1915 (i) target populations (children with developmental disabilities). Indiana applies this policy to one of its three Section 1915 (i) target populations (people with mental illness receiving behavioral health and primary care coordination). Ohio’s Section 1915 (i) option provides an independent eligibility pathway for people with mental illness. This option within Section 1915 (i) allows individuals who are not otherwise eligible under the state plan or a waiver to gain Medicaid coverage. The other eight states use Section 1915 (i) to authorize HCBS but require beneficiaries to be otherwise eligible for Medicaid through another coverage pathway.

Since adopting Section 1915 (i), no state has applied the option to restrict functional eligibility criteria to control enrollment. Unlike waivers, states are not permitted to cap enrollment or maintain a waiting list for Section 1915 (i) state plan HCBS. However, states can manage enrollment under Section 1915 (i) by restricting functional eligibility criteria if the state will exceed the number of beneficiaries that it anticipated serving. Functional eligibility for Section 1915 (i) HCBS requires beneficiaries to have needs that are less than what the state requires to qualify for an institutional level of care.

Section 1915 (c) and Section 1115 HCBS Waiver Policies

All states operate a total of 277 waivers to expand financial eligibility and offer HCBS to meet the needs of seniors and people with disabilities in the community. Nearly all of these waivers (265) are authorized under Section 1915 (c) (Appendix Table 5), while a minority (12) use Section 1115 to authorize HCBS (Appendix Table 6).39 Nine states (CA, DE, HI, NJ, NM, NY, TN, TX, and WA) serve some HCBS populations under a Section 1115 waiver and other HCBS populations through Section 1915 (c) waivers. Three other states (AZ, RI, and VT) use a Section 1115 waiver to provide HCBS to all covered populations and do not offer any Section 1915 (c) waivers. Both of these waiver authorities allow states to expand Medicaid financial eligibility and offer HCBS to seniors and people with disabilities who would otherwise qualify for an institutional level of care, target benefit packages to a particular population, and limit the number of people served.

Most states using a Section 1115 HCBS waiver require individuals to enroll in capitated managed care. The exception is Washington, which provides Section 1115 HCBS on a fee-for-service basis.40 Unlike Section 1915 (c) waivers, Section 1115 waivers can be used to authorize both HCBS and mandatory managed care enrollment. Alternatively, states can combine a Section 1915 (c) waiver with another managed care authority to permit or require HCBS beneficiaries to enroll in capitated managed care.41

CMS appears to be moving toward requiring states to operate joint Section 1915 (c)/1115 waivers if states want to require HCBS beneficiaries to enroll in capitated managed care. From 2008 to 2014, nine states eliminated Section 1915 (c) waivers and instead used Section 1115 waivers to authorize HCBS along with mandatory managed care (Figure 4). More recently, Kansas42 and North Carolina43 have been granted Section 1115 waiver authority to require beneficiaries to enroll in capitated managed care but continue to operate concurrent Section 1915 (c) waivers that authorize HCBS, instead of moving the HCBS authority to Section 1115. In addition, Rhode Island’s latest Section 1115 waiver renewal requires the state to transition HCBS authorized under Section 1115 to a Section 1915 (c) waiver or Section 1915 (i) state plan authority to the extent possible.44 Rhode Island’s waiver renewal also provides that any new HCBS that the state wants to implement after January 1, 2019 must be authorized under Section 1915 (c) or Section 1915 (i).45

The number of Section 1915 (c) waivers averages five per state and ranges from one to 11, depending on the number of populations served and how the state groups those populations (Appendix Table 5). Three states (DE, HI, and NJ) operate one Section 1915 (c) waiver and use Section 1115 waivers for all other HCBS populations. At the other end of the range, Connecticut and Colorado each operate 11 Section 1915 (c) waivers, and two states (MA and PA) each offer 10 Section 1915 (c) waivers targeted to different populations. By contrast, all 12 states using stand-alone Section 1115 HCBS waivers serve multiple populations under a single waiver (Appendix Table 6).

Two states added new HCBS waivers to serve additional enrollees in FY 2018, while one state discontinued a waiver that is expected to result in fewer people receiving HCBS.46 California added a new Section 1915 (c) waiver to serve individuals with I/DD, while Washington added a Section 1115 waiver providing HCBS to multiple populations, including seniors and people with physical disabilities, mental health disabilities, and TBI. Colorado is the state that anticipates an overall decline in the number of HCBS enrollees as a result of eliminating its Section 1915 (c) waiver targeted to young children with autism (I/DD).

Population served

All states serve people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD),47 seniors, and nonelderly adults with physical disabilities48 through HCBS waivers (Figure 5, Appendix Tables 5 and 6). Fewer states use HCBS waivers to serve people with traumatic brain and/or spinal cord injuries (TBI/SCI),49 children who are medically fragile or technology dependent,50 people with mental health disabilities,51 and people with HIV/AIDS.52

Financial eligibility and post-eligibility treatment of income

Over three-quarters of HCBS waivers set the income eligibility limit at the federal maximum (Figure 6 and Appendix Table 7). States can use waivers to expand HCBS financial eligibility to a maximum monthly income of 300% of SSI ($2,313/month for an individual in 2019). A minority of HCBS waivers (15 in 4 states) set the monthly income limit at 100% of SSI ($771/month for an individual in 2019).

Nearly all HCBS waivers set income eligibility limits at or above the nursing home limit. Most HCBS waivers (248 in 43 states) waivers use the same income eligibility criteria as are required for nursing home eligibility (no data shown). Another 17 HCBS waivers in six states use income limits that are less stringent than those required for institutional care. A minority of waivers (12 in five states, MD, MI, MO, OR, TX) use income limits that are more restrictive than those required for institutional care, which could incentivize institutional care over HCBS. Using the same income limits for HCBS waivers and institutional care removes any potential bias in favor of institutional care, which can occur if an individualmust have less income and/or assets to receive HCBS than to receive institutional services.

Over three-quarters of HCBS waivers apply the federal SSI asset limit of $2,000 for an individual, while a notable minority do not have any asset limit (Figure 6). The 24 waivers without an asset limit are in seven states (CO, IN, MA, MO, NE, ND, and WI). Colorado does not apply an asset limit to any of its 11 HCBS waivers, while the other six states remove asset limits for only some waiver populations, most frequently medically fragile children and children with I/DD.53 In addition, 23 waivers in eight states (DC, MD, MN, MS, ND, NE, NH, RI) have an asset limit that is higher than the SSI amount, ranging from $2,500 to $4,000.54 Five states apply this higher asset limit to all waiver populations (DC, MN, MS, NH, and RI), while three states apply the higher asset limit to some but not all waiver populations.55 Connecticut is the only state that applies an asset limit lower than the federal SSI amount ($1,600 per individual).56

Once eligible for an HCBS waiver, over half (27) of states require an individual to contribute a portion of their monthly income to the cost of their care (no data shown). Certain beneficiaries receiving home and community-based waiver services57 must contribute a portion of their income to their cost of care, although states generally allow them to retain a monthly maintenance needs allowance, recognizing that recognizing that they must pay for room and board as well as other basic needs that Medicaid does not cover, such as clothing. There is no federal minimum maintenance needs allowance for HCBS waiver enrollees; instead, states may use any amount as long as it is based on a “reasonable assessment of need” and subject to a maximum that applies to all enrollees under the waiver.58 Eight states set the monthly maintenance needs allowance at $2,250 (300% of SSI) for at least one waiver,59 while four states use $1,012 (100% FPL).60 The remaining states report another amount, ranging from $100 in Montana to $2,082 in Maine.61 Amounts vary within some states by waiver program and/or living arrangement. For example, only individuals in assisted living facilities are required to contribute to their cost of care in Delaware and Maryland. The maintenance needs allowance established by states play a critical role in determining whether individuals can afford to remain in the community, as Medicaid HCBS does not cover room and board, and avoid or forestall institutional placement.

Functional eligibility

Nearly all (273 of 277) HCBS waivers use functional eligibility criteria that are the same as or less stringent than the criteria to qualify for nursing home services (no data shown). Most (253 in 51 states) HCBS waivers use the same functional eligibility criteria as are required for nursing facility eligibility, treating HCBS and institutional care equally. A minority of waivers (20 in 11 states) use functional eligibility criteria that are less stringent than those required for institutional care. Very few waivers (four in three states, CA, OK, and OR) use functional eligibility criteria that are more restrictive than those required for institutional care. Each of these four waivers serves medically fragile children and sets financial eligibility the same as for institutions, even though functional eligibility is more restrictive. Functional eligibility criteria typically include the extent of assistance needed to perform self-care (such as eating, bathing, or dressing) and/or household activities (such as preparing meals or managing medications). Using the same functional eligibility for HCBS waivers and institutional care removes any potential bias in favor of institutional care, which can occur if an individual must have greater functional needs to receive HCBS than to receive institutional services.

The majority of states (40 of 49 responding) rely on state or local government agencies to perform the functional needs assessment for waiver services, and most (32 of 49 responding) states rely on a combination of entities across waiver programs (no data shown).62 Thirteen states rely solely on state or local government agencies to perform assessments. Other entities include community-based organizations (11 states), health care providers (8 states), and managed care plans (4 states).

Nearly all (46 of 48 responding) states rely on state-specific tools to conduct the functional needs assessment for HCBS waivers (no data shown).63 Thirty-five states use multiple tools across different waiver programs to assess functional need. Some states rely on nationally recognized assessment tools, including Inter-RAI (16 states), OASIS (AL), and CHOICES (AR). Nearly all (47 of 48 responding) states have an exceptions process in place for beneficiaries to appeal functional assessment results.64

Waiver services

Home-based services and equipment/technology/modifications are among the most commonly offered waiver services across all states and target populations.65 Other frequently offered services across all states and waivers include day services, nursing/therapy, and case management. Box 1 above lists the nine service categories included in our survey.

Some services are more common in waivers that target certain populations. For example, supported employment services are offered in nearly three-quarters of all I/DD waivers and over half of TBI/SCI waivers, compared to about one-quarter of waivers targeting seniors and adults with physical disabilities. Case management services are included in three-quarters of waivers serving medically fragile or technology dependent children but less than half of mental health waivers. Mental health/behavioral services are offered in two-thirds of waivers targeting individuals with mental illness, compared to less than half of TBI/SCI waivers and just over a quarter of waivers targeting seniors and adults with physical disabilities. The variation in waiver benefit packages reflects state flexibility in designing benefit packages targeted to particular populations’ needs. Table 1 presents the share of waivers that cover each service category by target population.

| Table 1: Share of HCBS Waivers that Provide Key Services, By Target Population, FY 2018 | ||||||||

| Target Population | Case Mgmt. | Home-based Services | Day Services | Nursing/Therapy Services | Round-the-Clock Services | Supported Employment | Other Mental Health/Behavioral Services | Equipment/Technology/Modifications |

| I/DD | 54% | 88% | 75% | 68% | 51% | 74% | 69% | 86% |

| Seniors & People with Disabilities | 62% | 85% | 61% | 70% | 40% | 24% | 27% | 78% |

| Medically Fragile/Tech. Dependent Children | 75% | 67% | 17% | 46% | 17% | 21% | 17% | 63% |

| Mental Illness | 42% | 75% | 17% | 33% | 25% | 42% | 67% | 50% |

| HIV/AIDS | 60% | 100% | 40% | 100% | 20% | 0% | 40% | 80% |

| TBI/SCI | 58% | 81% | 65% | 58% | 54% | 62% | 38% | 85% |

| NOTES: Includes both § 1915 (c) and 1115 waivers. Section 1115 waiver services were assigned to the main population targeted by the waiver: seniors/adults with physical disabilities and/or people with I/DD.SOURCE: KFF Medicaid HCBS Waiver Survey, FY 2018. | ||||||||

Self-direction and provider type

Waivers targeting seniors and/or adults with physical disabilities and people with TBI/SCI are most likely to offer enrollees the option to self-direct services, while mental health waivers are least likely to do so (Figure 7). Nearly all states allow beneficiaries in at least one HCBS waiver to self-direct services (Appendix Table 8).66 The exception is Alaska. In all 50 self-direction states, beneficiaries can select, train, and dismiss their direct care workers and set worker schedules.67 In 39 states, beneficiaries also can determine worker pay rates, and in 33 states, beneficiaries can decide how to allocate their service budgets.

Almost all states enable waiver enrollees to choose either agency-employed or independent providers, and over half of states allow legally responsible relatives to be paid providers (Appendix Table 8). All states offer agency-employed providers, and all but two states (DC and RI) offer independent providers. Thirty states allow certain legally responsible relatives (e.g. spouse, parent) to be paid providers.68

Utilization controls

Waiting lists

More than three-quarters of states (41 of 51) report an HCBS waiver waiting list for at least one waiver target population (Appendix Table 9). In addition to expanding financial eligibility and offering benefits targeted to a particular population, HCBS waivers allow states to choose – and limit – how many people are served. States’ ability to cap HCBS waiver enrollment can result in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the number of waiver slots available. The 10 states without any waiver waiting lists are AZ, DC, DE, HI, ID, MA, NJ, RI, VT, and WA.

Nearly 820,000 people are on HCBS waiver waiting lists nationally (Figure 8 and Appendix Table 9).69 Waiting lists are a function of the populations a state chooses to serve and how the state defines those populations; both of these factors vary among states, making waiting lists an incomplete measure of state capacity and demand for HCBS and not directly comparable among states. While all states have waivers serving people with I/DD, seniors, and adults with physical disabilities, fewer states offer waiver services for other target populations. Consequently, there may be a particular population in need of services, but the state does not keep a waiting list because it does not offer a waiver for that population. In addition, as described above, all states do not define the eligibility criteria for their waiver target populations in the same way.

All individuals on waiting lists ultimately may not be eligible for waiver services. For example, 33 states with waiting lists screen individuals for waiver eligibility before they are placed or while they are on a waiting list, while eight states do not. Notably, the eight states that do not screen for waiver eligibility comprise 61% (499,000) of the total waiting list population.70 Box 2 provides examples of recent changes in state waiver waiting list assessment policies.

Box 2: State Waiver Waiting List Policy Changes

Two states reported new waiver waiting list policies in FY 2018. Ohio adopted a new assessment tool in an effort to better understand the current needs of individuals on its I/DD waiver waiting lists.71 Ohio’s new assessment is in response to a study finding that 45% of its I/DD waiting list population had no current areas of unmet need; rather, individuals were joining the waiting list “well in advance of their need” for waiver services because they anticipated a lengthy wait.72 Another new Ohio policy requires county boards of developmental disabilities to address a person’s immediate needs within 30 days, through community resources, local funds, state plan services, or waiver services. Louisiana also adopted a new assessment tool to determine if individuals on its I/DD waiver waiting list require services now or in the near future to avoid institutionalization.73 Those with the highest scores on the new assessment are offered a waiver slot, and others will be rescreened at regular intervals or upon request.

Waiver waiting lists increased by 16 percent from FY 2017 to FY 2018, attributed primarily to the increase in Texas (Figure 8 and Appendix Table 10).74 This is higher than the average annual percent change in waiting list enrollment over the last 16 years, which was 10 percent. It also represents the highest annual percent increase since FY 2011, when waiting lists grew by 19 percent. Texas’ waiting list growth accounts for over 90% of the overall national increase in waiver waiting lists. In FY 2017, Texas’ waiver waiting list was 40% of the national waiting list total. In FY 2018, Texas’ share increased to nearly half (47%) of the national total. Texas does not determine eligibility before putting an individual on a waiting list, which is a possible contributing factor to the state’s increase.

Overall, 18 states reported an increase in total waiting lists from FY 2017 to FY 2018, and 15 states reported a decrease from FY 2017 to FY 2018, indicating state-level variation in waiting list trends (Appendix Table 10). Three states reported no notable change in waiver waiting lists from FY 2017 to FY 2018.75 Waiting list changes also varied by population, with growth occurring among waivers targeting individuals with I/DD (25%), seniors (19%), and individuals with mental health disabilities (10%). In contrast, waivers serving individuals with TBI/SCI, medically fragile children, and seniors and adults with physical disabilities experienced declines (-51%, -6% and -1% respectively) in the number of individuals on waiting lists for services between FY 2017 and FY 2018.

Although some people joined waiver waiting lists between FY 2017 and FY 2018, others left a waiting list and began receiving waiver services during this period. For example, 53,000 people moved off waiting lists and began receiving services in FY 2018, in the 33 (of 41) states that could report this data.76 People may move off a waiting list and begin receiving services when a state increases waiver capacity by funding new slots or when an existing waiver enrollee stops receiving services due to a change in income, functional need, age, state residency, or another reason relevant to waiver eligibility.

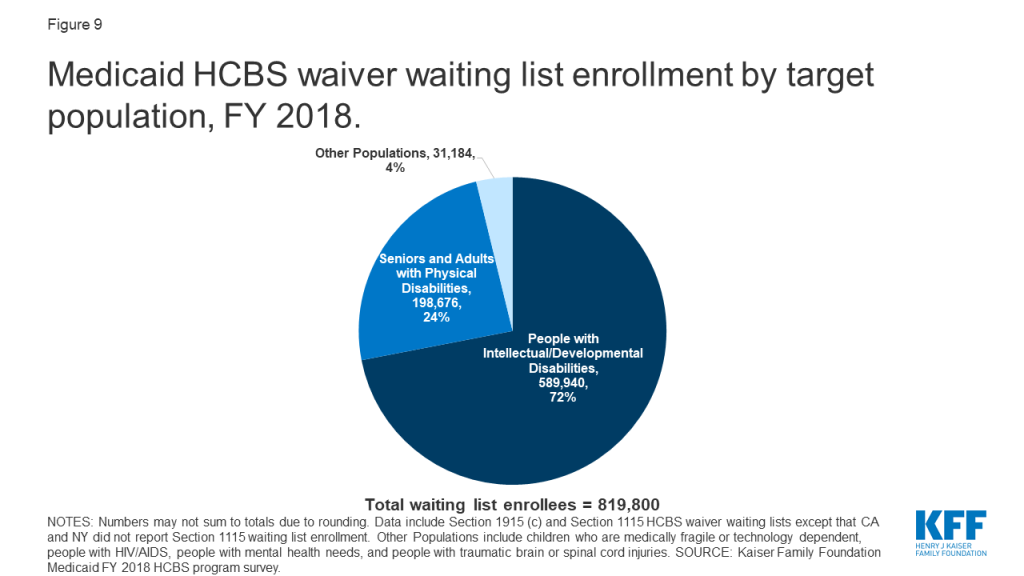

People with I/DD comprise over 70 percent (about 590,000 in 37 states)77 of total waiver waiting lists (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 9). Seniors and adults with physical disabilities account for about one-quarter (about 199,000 in 20 states)78 of total waiting lists. The remaining four percent of waiver waiting lists is spread among other populations, including children who are medically fragile or technology dependent (about 27,000 in five states),79 people with traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries (TBI/SCI, about 1,700 in seven states),80 people with mental illness (about 1,500 in four states),81 and people with HIV/AIDS (about 80 in 1 state).82

The waiting period for waiver services averages 39 months across all waivers with waiting lists, with substantial variation by target population (Appendix Table 11).83 The average waiting period by population ranged from one month for a waiver targeting people with HIV/AIDS (in 1 state) to 71 months for waivers targeting people with I/DD.

Almost all (38 of 41) states with waiting lists prioritize individuals with certain characteristics to receive services when slots become available.84 For example, 27 states offer waivers that give priority to individuals who meet specific crisis or emergency criteria, 24 states prioritize people who are moving from an institution to the community, and 22 states prioritize people who are at risk of entering an institution without waiver services (no data shown). Fewer states prioritize individuals based on assessed level of need (16) or age (5). Other reasons states use to prioritize individuals on waiting lists include aging caregiver, loss of primary caregiver, child in foster care, homelessness, or danger to self or others. Thirty-two states use more than one priority group.85

All states with waiting lists provide non-waiver Medicaid services (i.e., state plan services) to people who are waiting for waiver services. Medicaid state plan services can include some HCBS, such as home health, personal care, or case management. Some states also may provide services funded with state dollars that are allocated to county-based programs to individuals on a Medicaid waiver waiting list. Nearly all (94%) of people on waiver waiting lists currently live in the community in 27 (of 41) states reporting this data.86

Hour, cost, and geographic limits

Nearly three-quarters of states use hour, cost, or geographic limits to control utilization in their HCBS waivers (Appendix Table 12).87 Among these states, 19 use more than one type of utilization control, including 16 states with caps on both the number of service hours and the amount spent per enrollee, one state (CO) with both spending and geographic limits, and two states (CA and OH) with all three of these utilization controls. Another 15 states use only spending caps, such as such as limiting the cost of HCBS to a percentage of the nursing facility reimbursement rate or applying a maximum service cost based on a functional needs assessment score. Two states (AR and DC) use only hourly service caps, such as day, week, or annual limits. Services to which states apply hourly service caps include supported living, day habilitation, case management, respite, home modifications/environmental accessibility, skilled nursing, peer support, medical supplies, supported employment, and transition assistance. Most states (15 of 20 with hour caps88 and 25 of 34 with cost caps)89 allow exceptions to their utilization limits. The remaining 14 states do not apply any of these HCBS waiver service utilization controls.

States with utilization controls typically apply them to both self-directed and non-self-directed (e.g., agency-provided) services. Among the 20 states with both hourly caps and self-direction, most (14) apply these caps to both self-directed services and other services. Four states (LA, MO, MT, and NY) apply hourly limits only to non-self-directed services, and two states (ND and PA) apply hourly limits only to self-directed services. Similarly, most states (25 of 34) apply cost caps (typically per year) to both self-directed and other services, while nine states apply cost caps to only non self-directed services. No state applies a cost cap only to self-directed services.

Application of state utilization controls varies by waiver target population, with at least half of all waivers that serve people with TBI/SCI (58%), HIV/AIDS (60%), and mental illness (50%) applying at least one utilization control. Other waiver populations see smaller rates of utilization control application, with one-third of waivers that serve medically fragile children applying at least one utilization control. All target populations have some waivers that apply spending caps or service hour limits, except that waivers serving people with HIV/AIDS apply spending caps but not service hour limits. Spending caps are a more common utilization control than service hour limits across all target populations, with about twice as many waivers applying spending caps as service hour limits.

Quality measures

All states monitor HCBS waiver quality, but no set of standardized measures is used across programs. Most HCBS waiver quality measures are based on CMS reporting requirements for Section 1915 (c) waivers, and these measures tend to be process, not outcome, oriented. For example, states must identify Section 1915 (c) waiver performance measures to evaluate level of care determinations, provider qualifications, service plans, enrollee health and welfare, and financial compliance.90 In recent years, states have begun to expand HCBS quality measures to add beneficiary experience measures, such as quality of life, community integration, and LTSS rebalancing, described below.

Forty-six states measure beneficiary quality of life when monitoring HCBS waiver quality (Appendix Table 12). Quality of life measures include assessing an individual’s level of satisfaction with their current living situation, degree of control over their daily activities, and whether services are adequate to their support needs. Among these specific quality of life measures, level of satisfaction with current living situation (22 states) was the most commonly reported measure. States measuring quality of life most commonly rely on the National Core Indicators (NCI) surveys for seniors and adults with physical disabilities91 and/or for individuals with I/DD92 (30 states). Ten states use other state-specific tools, and four states (CT, OH, PA, and WV) use the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) HCBS survey.93 States can use more than one tool to measure quality of life.94

Forty-four states have waiver quality measures to assess community integration (Appendix Table 12). Community integration measures include the ability to choose where one lives or the amount of community involvement in work and/or leisure activities. Among these specific community integration measures, the ability to choose where an enrollee lives (19 states) was the most commonly reported measure. States measuring community integration most commonly use the NCI surveys (21 states), followed by state-specific tools (13 states), and the CAHPS survey (3 states, CT, PA, WV).95

Twenty-five states measure LTSS rebalancing when assessing HCBS waiver quality (Appendix Table 12). To do so, states may collect information on the number of enrollees in institutions versus the community, the number of individuals transitioning from institutions to the community, and/or the number of individuals transitioning from the community to institutions. Among these specific rebalancing measures, the number of individuals transitioning from institutions to the community (9 states) was the most commonly reported measure. No state reported measuring the number of individuals transitioning from the community to institutions. States measuring rebalancing utilize various tools including Money Follows the Person program benchmarks (12 states), state-specific tools (6 states), and the NCI-IDD survey (one state).96

Ombuds programs

Forty-one states have an HCBS waiver ombudsman program, typically as part of state government, to assist waiver enrollees (Appendix Table 12).97 Thirty-two states have an ombuds program that is solely within state government, while four (HI, IN, TN, and WI) have ombuds programs that include both state government and non-governmental entities. For example, in Wisconsin, ombuds services for seniors are provided through a governmental entity (the Board on Aging and Long-Term Care), while ombuds services for non-elderly adults with disabilities are provided through a contract with a community-based organization (the state’s protection and advocacy agency for people with disabilities). Tennessee uses governmental agencies (Area Agencies on Aging and Disability) to provide ombuds services for individuals receiving community-based residential alternatives and also contracts with a community-based organization (the state’s protection and advocacy agency) to provide broader ombuds services. Two states (AZ and RI) have ombudsman programs solely operated by a community-based agency, and three states (LA, NY, and VT) rely solely on another type of entity. Ombudsman programs may provide enrollment options counseling, assist beneficiaries with health plan appeals, offer information about state fair hearings, track beneficiary complaints, train health plans and providers about community-based services and supports that can be linked with Medicaid-covered services, and report data and systemic issues to states.98

Medicaid Capitated Managed LTSS (MLTSS) Programs

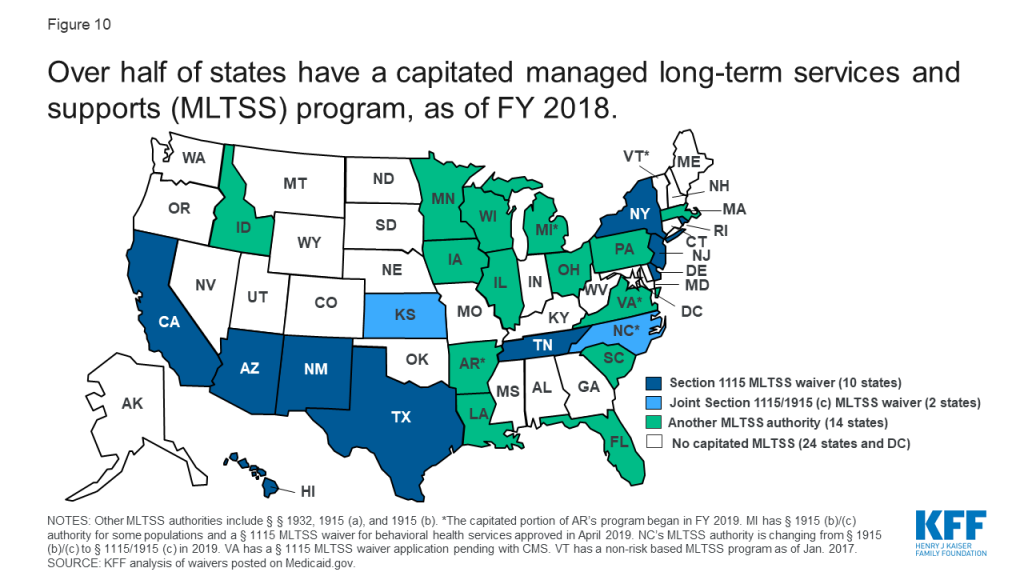

Twenty-five states deliver some or all HCBS through capitated (risk-based) managed long-term services and supports (MLTSS) programs (Figure 10 and Appendix Table 13).99 In addition, survey findings in this section include responses from Arkansas, which implemented the capitated portion of its MLTSS program for people with I/DD and behavioral health needs in FY 2019,100 for a total of 26 states reporting MLTSS policies. About half of MLTSS states implement capitated managed care through a Section 1115 waiver, while the remaining states use another managed care authority, such as a Section 1915 (b) waiver, the Section 1932 state plan option, or Section 1915 (a) authority. Two states implemented new MLTSS programs in FY 2018: Louisiana has a joint Section 1915 (b)/(c) waiver providing specialty behavioral health services and HCBS for children with serious emotional disturbance effective February 2018,101 and Pennsylvania has a joint Section 1915 (b)/(c) waiver that includes individuals with I/DD, seniors, adults with physical disabilities, and individuals with TBI, with enrollment effective January 2018.102 In addition, one state, North Carolina, is in the process of changing its MLTSS authority from joint Section 1915 (b)/(c) waivers to joint Section 1115/1915 (c) waivers for people with I/DD and TBI.103

Rebalancing incentives in MLTSS programs

About half of capitated MLTSS states use financial incentives for health plans to offer HCBS instead of institutional care (Appendix Table 13). The most common type of rebalancing incentive is a blended capitation rate that includes both institutional and home and community-based LTSS, used in 11 states. Two states (FL and SC) offer bonus payments to health plans based on institutional to community transitions.104 Six MLTSS states do not include financial incentives for HCBS over institutional services.105

Value-based payment in MLTSS programs

Seven capitated MLTSS states currently are using value-based payment (VBP) models for HCBS,106 and 10 states plan to implement new or expanded VBP models for HCBS in the future107 (Appendix Table 13). Among the states with current models, four require health plans to use VBP arrangements (AZ, AR, TN, and WI), and two encourage health plans to use VBP arrangements (NY and VA). For example, Arizona requires its health plans to have a certain proportion of provider payments made through VBP; the target percentage varies by provider type and population, ranging from 35 percent for seniors and adults with physical disabilities to five percent for adults with I/DD. The remaining state, Iowa, encourages VBP arrangements for all waiver populations, except for individuals with HIV/AIDS and seniors where VBP is required. VBP models generally include any initiative in which a state Medicaid program seeks to hold providers and/or health plans accountable for the cost and quality of care that they provide or finance.108 These models seek to shift the focus away from payment based solely on the provision of individual services, as in the fee-for-service model, which is critiqued as incentivizing service volume. Instead, VBP seeks to account for the value and quality of services delivered through shared savings/shared risk arrangements, episode-based payments, or other alternative payment models.109

The most commonly used VBP model for HCBS is pay for performance, used by four of seven states (AZ, AR, IA & WI).110 A pay for performance model seeks to improve care coordination and care quality and reduce overall spending by tying payment to care that meets specific goals or quality standards. For example, Wisconsin’s Family Care pay for performance model bases payments on results from an enrollee survey and competitive integrated employment. In Arkansas, the Provider-led Arkansas Shared Savings Entity (PASSE) program, serving individuals with I/DD or mental illness, will use both shared savings and incentive payments that are tied to reporting/achieving certain outcome or quality measures.111 Tennessee uses an outcome-based reimbursement model for supported employment services provided to people with I/DD. Tennessee’s program includes outcome-based reimbursement for up-front services leading to employment; tiered outcome-based reimbursement for job development and self-employment start-up services based on the individual’s acuity level and paid in phases to support job tenure; and tiered reimbursement for job coaching, based on acuity and taking into account the length of time the person has held the job and the amount of paid support required as a percentage of hours worked, with the goal of paid supports fading over time. Virginia encourages its health plans to establish VBP arrangements with all provider types, including HCBS, but does not require a specific model.

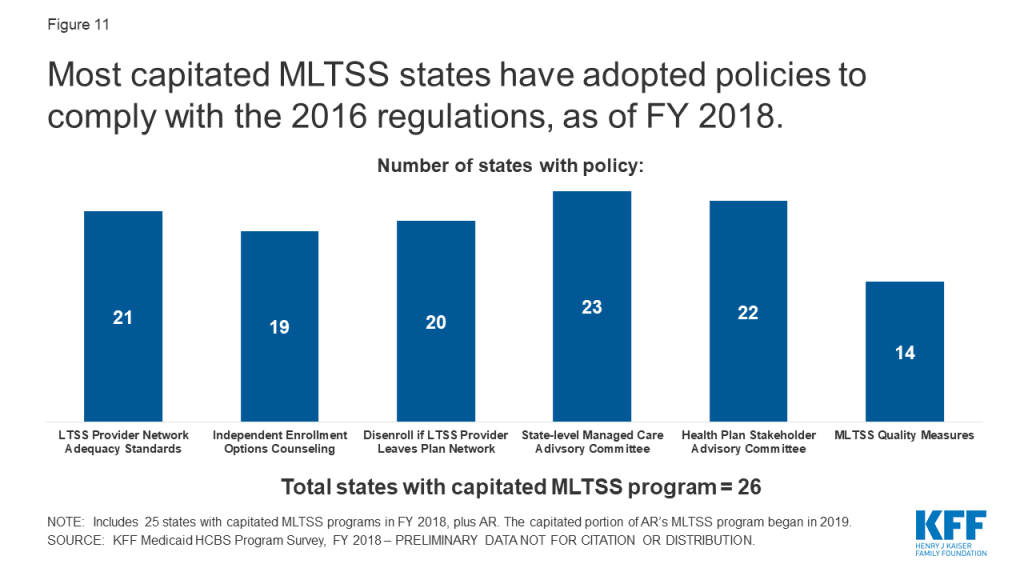

LTSS provisions in the 2016 Medicaid managed care rule

Most capitated MLTSS states have adopted policies to comply with the 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations (Figure 11 and Appendix Table 13). The 2016 regulations, issued under the Obama Administration, addressed MLTSS for the first time and included new provisions for LTSS provider network adequacy standards, independent enrollment choice counseling, disenrollment for cause if an LTSS provider leaves the health plan network, stakeholder advisory committees, and LTSS quality measures; different provisions of the regulations had different effective dates.112 However, in November 2018, under the Trump Administration, CMS proposed some changes to the 2016 regulations, most notably to the network adequacy standards.113 The public comment period closed in January 2019, and the proposed changes have not yet been finalized. CMS also issued a June 2017 informational bulletin indicating that it “intends to use [its] enforcement discretion. . . when states are unable to implement new and potentially burdensome requirements of the final [managed care] rule by the required compliance date, particularly provisions with a compliance deadline of contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017,” while changes to the managed care regulations are pending.114

LTSS Network Adequacy Standards

Over three-quarters of capitated MLTSS states require network adequacy standards for HCBS providers (Figure 11 and Table 2).115 The 2016 managed care regulations require states to develop time and distance standards for MLTSS providers when the enrollee must travel to the provider, and network adequacy standards other than time and distance standards for MLTSS providers that travel to the enrollee to deliver services. These standards are required for health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2018. However, CMS’s November 2018 proposed rule would remove the requirement for time and distance standards and instead would allow states to choose another quantitative standard, such as minimum provider-to-enrollee ratios, maximum travel time or distance to providers, minimum percentage of contracting providers accepting new patients, maximum wait times for an appointment, orhours of operation requirements.116

The most commonly used HCBS network adequacy standard is based on time and distance, when the enrollee must travel to the provider, used by 14 states (Table 2). Over half of capitated MLTSS states with HCBS network adequacy standards (12 of 21) include more than one type of standard.117 For example, Tennessee includes time and distance to provider (for site-based services, such as adult day services), minimum provider to enrollee ratio, and maximum travel time or distance (including a choice of providers for every service in every county), while Texas includes time and distance to provider, hours of operation requirements, and maximum wait time for an appointment. No state reported requiring a minimum percentage of contracting providers who are accepting new patients.

| Table 2: State MLTSS Network Adequacy Standards for HCBS Providers, FY 2018 | |

| Standard | Number of States Adopting, out of 26 Capitated MLTSS States: |

| Time and Distance to Provider | 14 states (AZ, DE, FL, ID, KS, LA, MI, NM, PA, SC, TN, TX, VA, WI) |

| Minimum Provider to Enrollee Ratio | 8 states (AR, FL, HI, ID, OH, SC, TN, WI) |

| Maximum Travel Time or Distance to Provider | 6 states (ID, LA, NY, SC, TN, VA) |

| Hours of Operation Requirements | 5 states (AZ, FL, LA, NY, TX) |

| Maximum Wait Time for an Appointment | 4 states (DE, LA, NY, TX) |

| Another Standard | 9 states (AZ, DE, IA, MI, MN, NJ, SC, TN, TX) |

| No Network Adequacy Standard Reported | 5 states (CA, IL, MA, NC, RI) |

| SOURCE: KFF Medicaid HCBS Program Survey, FY 2018. | |

Independent Enrollment Options Counseling

Most MLTSS states offer independent enrollment options counseling (Figure 11 and Appendix Table 13). States most often contract with a third party enrollment broker for options counseling (8 states), while others rely on community-based organizations (5 states) or another entity (4 states).118 In addition, Arizona provides options counseling through the state Medicaid agency instead of a third-party entity.119 CMS’s 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations require all states to offer enrollee choice counseling through the independent beneficiary support system required in health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2018.120 Options counseling seeks to help MLTSS enrollees select a health plan; this population may not be familiar with that process because they traditionally have been enrolled in the fee-for-service delivery system. MLTSS enrollees also may seek assistance with choosing a health plan to find a provider network that best meets their various needs – which may go beyond primary care to include specialists, behavioral health providers, durable medical equipment suppliers, and personal care attendants – and preserves their existing provider relationships to the extent possible.

Disenrollment If LTSS Provider Leaves Plan Network

Most MLTSS states allow individuals to disenroll from their health plan if their residence or employment would be disrupted as a result of an LTSS provider leaving the health plan network (Figure 11 and Appendix Table 13).121 Under the 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations, states must consider these circumstances as good cause for disenrollment for health plan contracts beginning or after July 1, 2017.122 Another state, Arizona, does not allow individuals to disenroll from a health plan for employment disruptions; however, if a skilled nursing facility or assisted living facility leaves the health plan provider network, Arizona requires the health plan to continue pay for those services until the individual’s next open enrollment period in order to mitigate disruption in residential placement.

Stakeholder Advisory Committees

Nearly all MLTSS states have a state-level managed care advisory committee and require health plans to have a stakeholder advisory committee (Figure 11 and Appendix Table 13).123 The 2016 Medicaid managed care regulations require states to create and maintain a stakeholder group to solicit and address the opinions of beneficiaries, individuals representing beneficiaries, providers, and other stakeholders in the design, implementation, and oversight of a state’s MLTSS program. In addition, health plans providing MLTSS must have a member advisory committee that includes at least a reasonably representative sample of the populations receiving LTSS covered by the plan or other individuals representing those enrollees. These provisions are effective for health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017.124

MLTSS Quality Measures

Over half of MLTSS states have adopted at least one MLTSS quality measure (Figure 11 and Table 3).125 The 2016 Medicaid managed care rule requires states that provide MLTSS to identify standard performance measures related to quality of life, rebalancing, and community integration for health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017.126 To assist states in this area, CMS developed eight MLTSS quality measures, with the goal of creating nationally standardized measures to enable comparisons of state MLTSS programs performance.127 Most of these states (10 of 14) are using at least one of CMS’s recommended measures, while the remaining states are using other state-specific measures (MI, NJ, VA, and WI). Among these 10 states using CMS recommended measures, nearly all have adopted three or more of the eight measures. The exception is New Mexico, which has adopted one of the recommended measures.

| Table 3: State Use of MLTSS Quality Measures, FY 2018 | |

| Measure Type | Number of States Adopting Measure, out of 26 Capitated MLTSS States: |

| CMS Recommended Measures | |

| Comprehensive Assessment | 9 states (AZ, DE, FL, IA, MN, PA, RI, SC, TN) |

| Comprehensive Care Plan and Update | 9 states (AZ, DE, FL, IA, MN, PA, RI, SC, TN) |

| Screening, Risk Assessment and Plan of Care to Prevent Future Falls | 5 states (DE, IA, MN, PA, SC) |

| Successful Transition After Long-Term Institutional Stay | 5 states (DE, IA, NM, PA, SC) |

| Re-Assessment/Care Plan Update After Inpatient Discharge | 4 states (FL, IA, PA, TN) |

| Shared Care Plan with Primary Care Practitioner | 4 states (AZ, FL, IA, TN) |

| Admission to Institution from the Community | 3 states (DE, IA, PA) |

| Minimizing Institutional Length of Stay | 2 states (IA, SC) |

| Another Measure | 4 states (MI, NJ, VA, WI) |

| No Measure | 12 states (AR, CA, HI, ID, IL, KS, LA, MA, NY, NC, OH, TX) |

| SOURCE: KFF Medicaid HCBS Program Survey, FY 2018. | |

Electronic Visit Verification Rule

States are working to meet electronic verification visit (EVV) requirements for all Medicaid personal care services and home health services that require an in-home visit by a provider.128 This new policy requires electronic verification of the type of service performed; the individual receiving the service; the service date; the location of service delivery; the individual providing the service; and the time the service begins and ends.129 EVV seeks to reduce unauthorized services, fraud, waste, and abuse and improve service quality.130 The EVV requirement is part of the 21st Century Cures Act and applies to all personal care and home health services provided under state plan or waiver authority.131 States are required to implement EVV for personal care services by January 1, 2020, and home health services by January 1, 2023.132

Four states already have EVV systems in place for all personal care state plan and waiver services, and another 12 states have implemented EVV for some but not all personal care services (Figure 12 and Appendix Table 14). In general, states report wide variation in EVV implementation across their personal care state plan and waiver programs, with few states having EVV systems in place for personal care services provided under all authorities. The states that have implemented EVV for all personal care services to date are Alabama, Louisiana, New Mexico, and Rhode Island. Eighteen percent (6 of 34 states)133 of state plan personal care programs and 19 percent of all waivers offering personal care services (41 of 216 waivers in 15 states) had an EVV system in place for personal care services inFY 2018.

About half of states expect to have EVV in place for some or all personal care services by the January 2020 deadline (Appendix Table 14). Seven of these states (AR, ME, NV, SD, VT, WA, and WV) expect to have EVV in place for all personal care state plan and waiver authorities, and the remainder expect to have EVV in place for some but not all personal care authorities. States that fail to implement EVV for personal care services by January 2020 are subject to incremental reductions in federal Medicaid matching funds, up to one percent.134 However, CMS can grant an exemption from federal funding reductions to states that make a good faith effort to comply but encounter unavoidable delays, though the exemption authority only applies to 2020.135 Most states already have requested or plan to request such an exemption. CMS began accepting exemption requests in July 2019, and as of February 2020, 40 states had been approved.136

Few states already have EVV systems in place for home health state plan services, although most expect to do so by the January 2023 deadline (Appendix Table 14). Among the states that have not yet implemented EVV for home health services, a dozen expect to do so prior to the 2023 deadline. As for personal care services, states that do not implement EVV for home health services by January 2023 are subject to incremental reductions in federal matching funds, although CMS can grant a one year exemption from these reductions to states that have made a good faith effort to comply but have encountered unavoidable delays.137

Nearly all states have selected an EVV model for personal care services (46 of 51)138 and home health services (41 of 51),139 with an open vendor model as the most common choice (Appendix Table 14). States have flexibility to choose their EVV model.140 Eighteen states are using an open vendor model for personal care services, and 16 are doing so for home health services. In an open vendor model, the state contracts with a single vendor or builds its own EVV system but also allows providers and health plans to use other vendors. Seven states are using a state mandated external vendor model for personal care services and six are doing so for home health services. In this model, the state contacts with a single EVV vendor that all providers must use. Six states are using a provider choice model for personal care services, and seven are doing so for home health services. In a provider choice model, providers select an EVV vendor and fund system implementation. One state (LA) is using a state-mandated in-house system for home health EVV, which involves the state creating and managing its own EVV system. The remaining states report using “another” model, which could include a hybrid approach. For example, Tennessee is allowing health plans to select an EVV vendor and fund its implementation. Most states have selected the same EVV model for personal care and home health services, although seven states have selected different models.141

Over half of states (32 of 51) states report challenges with meeting the EVV requirements for personal care and/or home health services. Common challenges include issues related to provider outreach and education (22 states), establishing an EVV system in rural areas (21 states), accommodating enrollees who self-direct services (21 states), and enrollee outreach and education (18 states). About half (24) of states cite multiple challenges with EVV implementation. Provider outreach and education can be challenging given the diversity and often high turnover rate of HCBS providers. Challenges in rural areas include establishing systems that can accommodate enrollees and providers who may lack cellphone or internet access. EVV for enrollees who self-direct services can be challenging to align with the system used by fiscal agents.

HCBS Settings Rule

Nearly all states (47 of 51) already have changed or anticipated having to change a rule or policy to come into compliance with the home and community-based settings rule (Figure 13 and Appendix Table 15).142 This includes 38 states that made changes prior to FY 2018, and 33 states that were making new or additional changes in FY 2018. The January 2014 rule defines the qualities of residential and non-residential settings in which Medicaid-funded HCBS can be provided.143 To be considered community-based, a setting must support an individual’s full access to the greater community; be selected by the individual from options including non-disability specific settings; ensure individual privacy, dignity, respect and freedom from coercion or restraint; optimize individual autonomy in making life choices; and facilitate individual choice regarding services and providers. Additional criteria apply to provider-owned or controlled settings. CMS extended the original state compliance deadline by three years, to March 2022, and states’ transition plans were due in March 2019.144 As of February 2020, 15 states have received final CMS approval on their transition plan,145 and another 30 states have received initial approval.146

Among the policy changes states are making to comply with the settings rule, most are related to settings that do not meet the rule’s requirements and need to be modified in some way to continue to be used for Medicaid-funded HCBS. To date, 39 states have identified settings that need to be modified (Figure 13).147 The number of settings that must be modified varies substantially by state, ranging from the single digits in Alabama, Arkansas, and Wyoming, to several hundred in other states, to one thousand or more in Hawaii, Indiana, Michigan, New Hampshire, Oregon, and South Carolina (Appendix Table 15).148

Additionally, 20 states have identified settings that cannot be modified to meet the settings rule and consequently will require beneficiaries to be relocated to continue receiving Medicaid-funded HCBS (Figure 13).149 Relatively few settings per state fall into this category, ranging from one in Delaware and Florida to 20 in North Carolina (Appendix Table 14),150 although any relocation has the potential to be disruptive to the affected beneficiaries.

Over half of states have identified settings that are presumed institutional because they effectively isolate beneficiaries as a result of the settings rule (Figure 13).151 Most states have relatively few settings in this category, with the exception of Michigan, which has identified over 1,000 settings that may isolate individuals with I/DD (Appendix Table 15).152 The settings rule presumes that certain settings are not community-based because they have institutional qualities, such as those in a facility that provides inpatient treatment, those on the grounds of or adjacent to a public institution, and those that have the effect of isolating individuals from the broader community.