Getting into Gear for 2014: Shifting New Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies into Drive

On January 1, 2014, many key provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will start to go into effect, including the expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults and the launch of new Medicaid eligibility and enrollment processes, which are designed to move toward a coordinated enrollment system across health coverage programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, and the new Health Insurance Marketplaces. Over the past year, states have made steady and significant progress preparing for these changes, but readiness varies considerably as 2014 nears, and implementation work and ongoing process improvements will continue into the foreseeable future. To provide greater insight into the status of implementation, this report provides an overview of key state Medicaid eligibility and enrollment policies slated to go into effect, based on data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The data provide insight into who will be eligible for Medicaid and CHIP across states and how individuals will enroll in coverage.

Executive Summary

On January 1, 2014, many key provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will start to go into effect, including the expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults and the launch of new Medicaid eligibility and enrollment processes, which are designed to move toward a coordinated enrollment system across health coverage programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, and the new Health Insurance Marketplaces. Over the past year, states have made steady and significant progress preparing for these changes, but readiness varies considerably as 2014 nears, and implementation work and ongoing process improvements will continue into the foreseeable future. To provide greater insight into the status of implementation, this report provides an overview of key state Medicaid eligibility and enrollment policies slated to go into effect based on data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). (See the Appendix Tables for state-specific data.)

Medicaid Eligibility as of January 2014

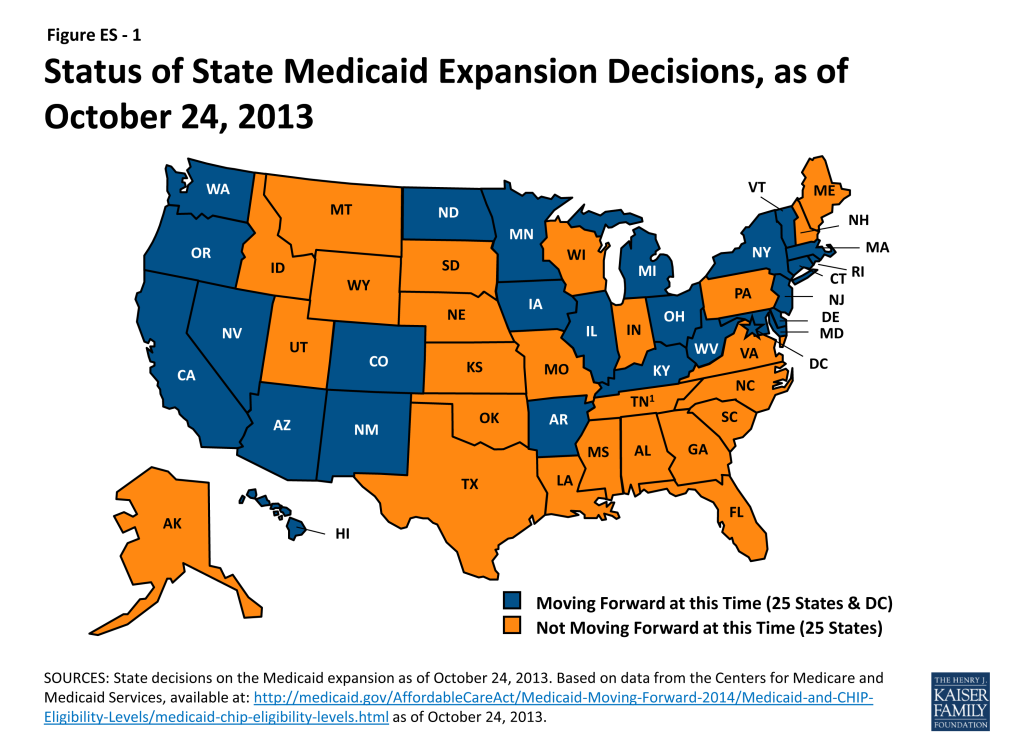

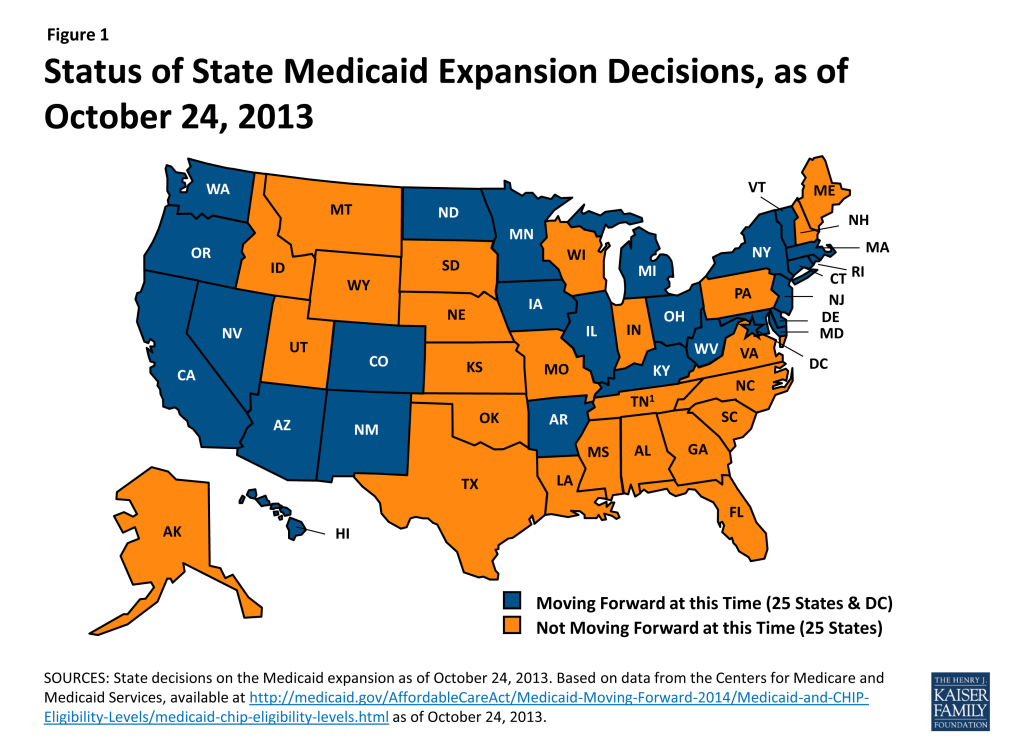

The ACA, as enacted, expands Medicaid to nearly all adults at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) as of January 1, 2014. This expansion, however, was effectively made a state option as a result of the Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of the ACA, and as of October 24, 2013, 26 states, including DC, are moving forward with the expansion, while the remaining 25 states are not moving forward at this time (Figure ES-1). There is no deadline for states to adopt the expansion, and several states are still actively considering it.

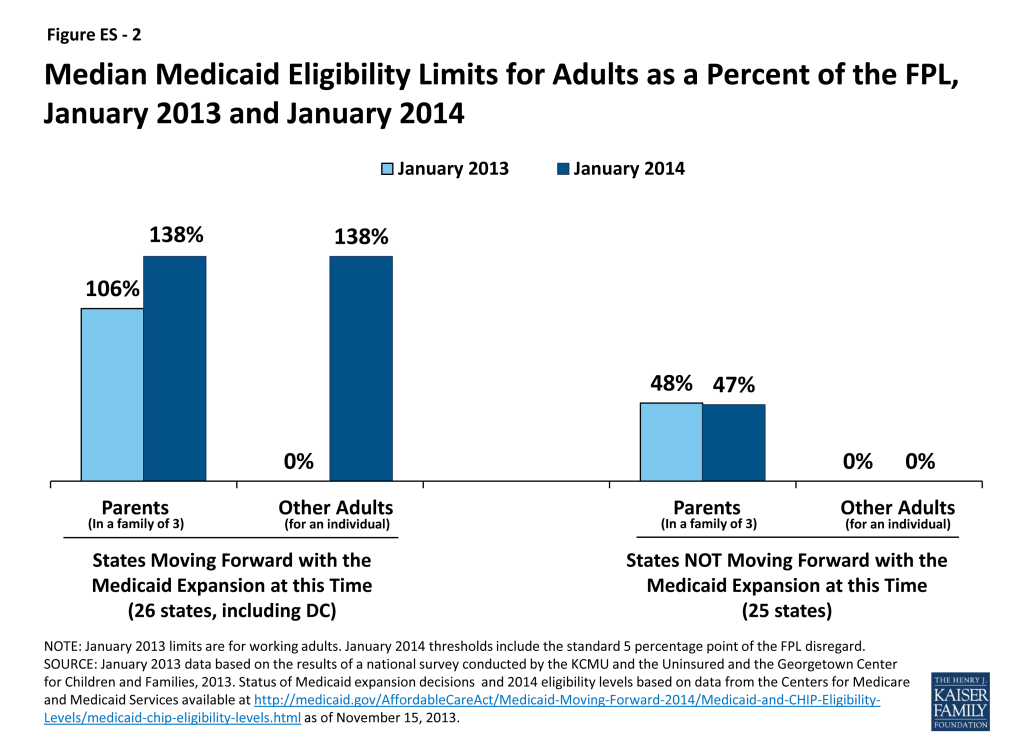

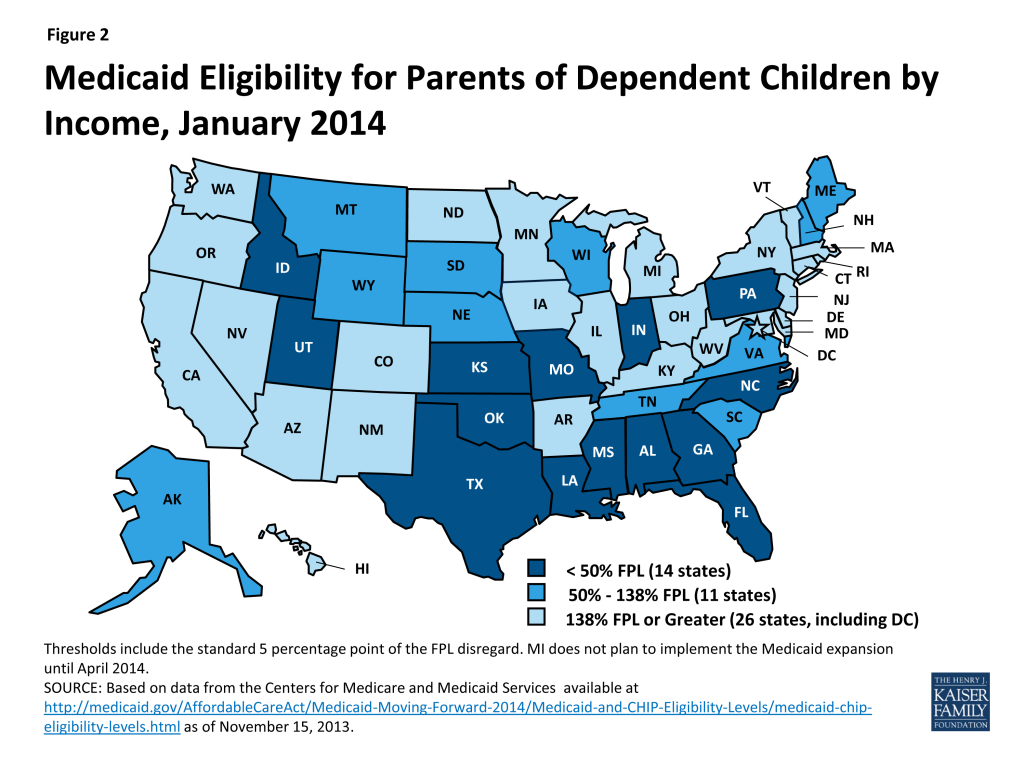

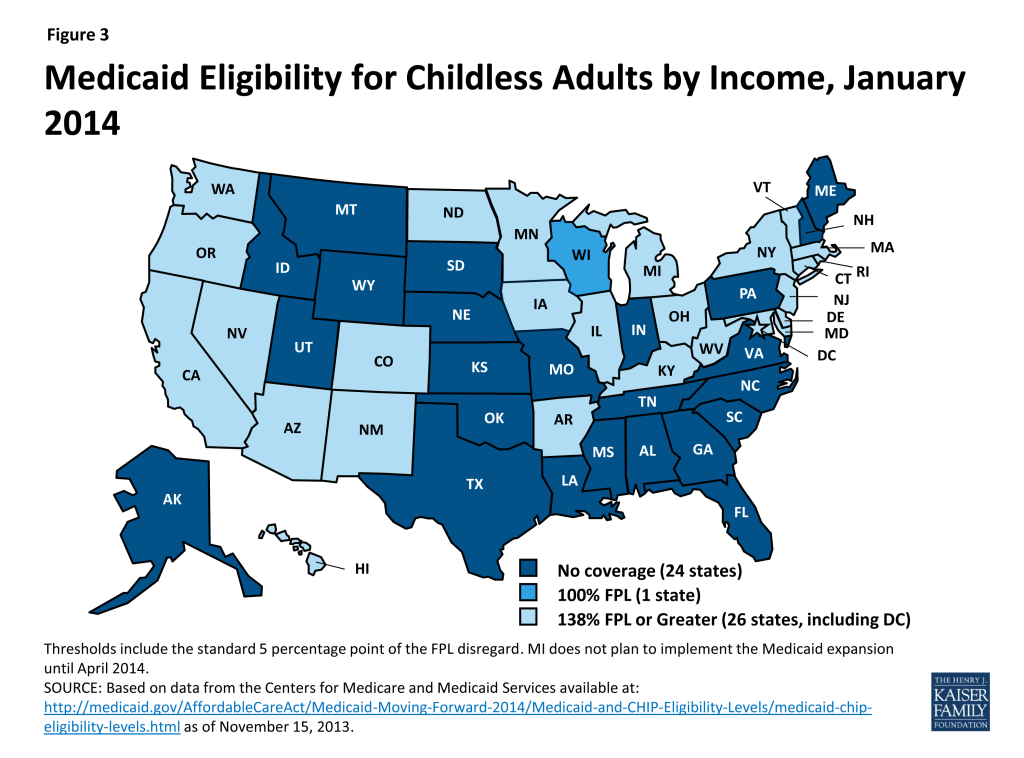

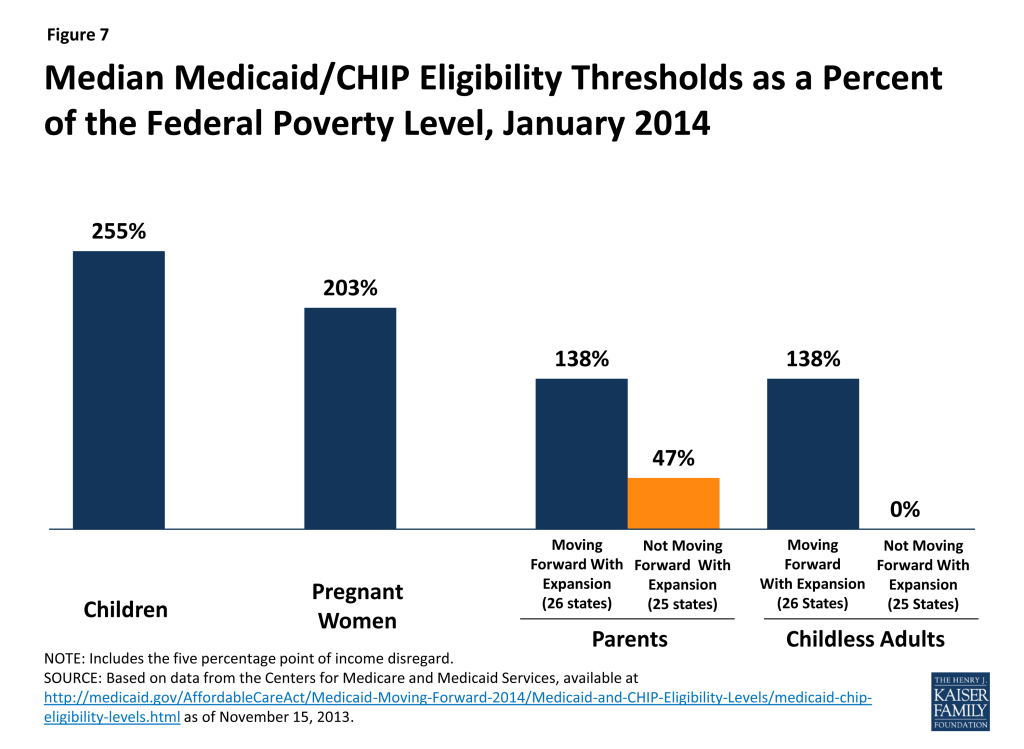

Eligibility levels for parents and other adults will significantly increase in states implementing the Medicaid expansion, while large coverage gaps will remain in states not expanding at this time. In the 26 states expanding Medicaid, the median eligibility threshold for parents will increase from 106 to 138 percent of the FPL and the median limit for adults without dependent children will significantly rise from 0 to 138 percent of the FPL (Figure ES-2). However, many poor parents and other adults will remain ineligible in the 25 states not expanding at this time. In 21 states, parent eligibility levels will remain below 100 percent of the FPL, with eligibility levels below half of poverty in 14 states. Overall, the median eligibility level for parents in these states will be just 47 percent of the FPL and only Wisconsin will provide full Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children. Parents and other adults with incomes above these limited Medicaid eligibility levels but below 100 percent of the FPL will fall into a coverage gap, since they will earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to qualify for premium tax credits in the Marketplaces, which begin at 100 percent of the FPL. This gap will leave nearly five million uninsured adults without a new coverage option.

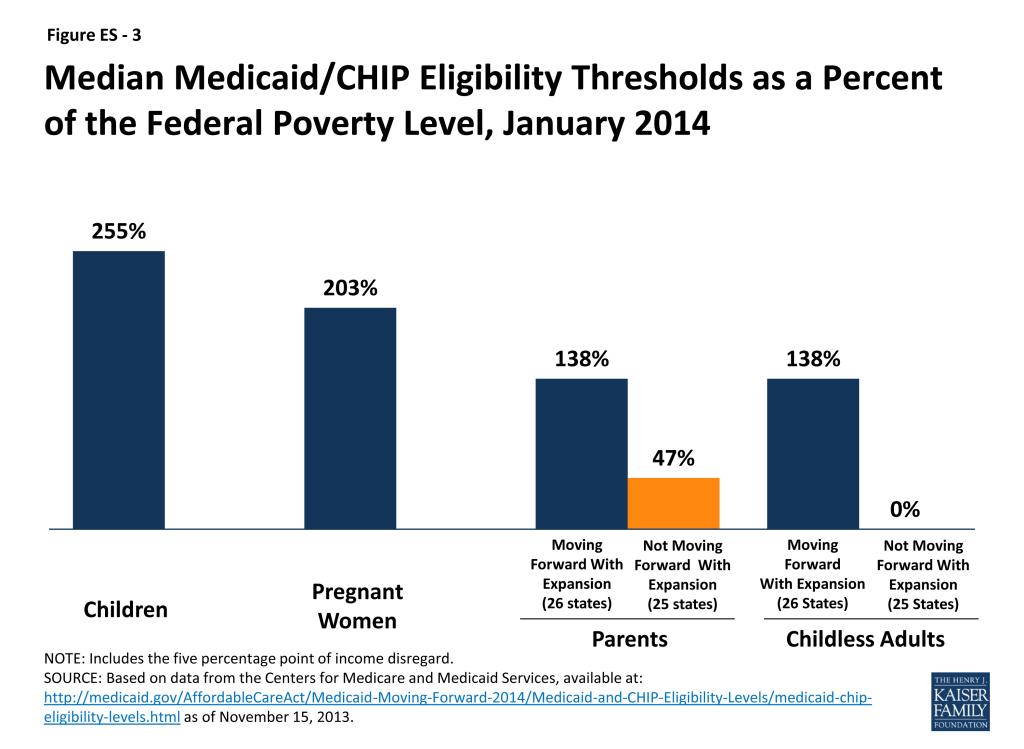

Coverage for children and pregnant women through Medicaid and CHIP will remain strong in 2014. More than half of the states (30, including DC) will cover children in families with incomes at or above 250 percent of the FPL and 20, including DC, will cover children in families with incomes at or above 300 percent of the FPL. Moreover, despite some eligibility reductions for pregnant women, as of January 1, 2014, 32 states, including DC, will cover pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the FPL. As such, while coverage for parents and childless adults will markedly improve in states implementing the Medicaid expansion, their median eligibility level will still remain lower than that of children and pregnant women (Figure ES-3). These disparities in eligibility across groups will be even starker in states that are not expanding Medicaid.

Connecting People to Coverage through Streamlined Enrollment Processes

The ACA envisions seamless and timely access to the continuum of health coverage options regardless of where or how someone applies. To achieve these objectives, the ACA establishes new expectations for simplifying the application process, coordinating enrollment, and moving toward paperless verification of eligibility. These include state adoption of a single streamlined application that screens for all health coverage options, electronic transfers of accounts between agencies to facilitate transitions across health coverage programs, and reliance on trusted sources of electronic data rather than requesting paper documentation to verify eligibility criteria.

As of October 1, 2013, 43 of 50 reporting states have deployed a single, streamlined application through their Medicaid agency. The seven remaining reporting states are in the process of developing their single, streamlined application, and nearly all anticipate having it in place by January 2014. In the interim, these states are utilizing their existing Medicaid applications and individuals who may be eligible for premium tax credits are being directed to apply through the federal Marketplace. Among the 43 Medicaid agencies that have a single streamlined application as of October 1, 2013, all had a paper version available while 36 had an online version. Looking ahead, states will continue work to make the application available through multiple modes, including online, phone, in-person, or mail. Moreover, in 32 states, further revisions will be made to their single streamlined application to meet the ACA standards, for example, by removing questions that are not relevant to eligibility.

The ability to electronically transfer individual accounts between state Medicaid/CHIP agencies and Marketplaces to coordinate enrollment is in various stages of development. Among the 17 states with State-based Marketplaces (SBMs), all but two (2) have an integrated or linked technology system that determines eligibility for all insurance affordability options and facilitates the next steps for enrollment. However, in states using the Federally-Facilitated Marketplace (FFM), electronic transfers of individual accounts between the FFM and Medicaid/CHIP agencies are essential for coordinating enrollment. Due to ongoing technological challenges with the FFM, these transfers have been delayed and alternative strategies have been put into place. For example, until the FFM can begin transferring electronic accounts to state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, it is sending batches of basic data on individuals the FFM has determined or assessed as potentially eligible for Medicaid/CHIP. Similarly, if a state Medicaid/CHIP agency is unable to transfer an account to the FFM, it can direct individuals to apply directly through the FFM. Moving forward, implementing electronic account transfers will be key to minimizing burdens on consumers and ensuring they are successfully enrolled in the coverage for which they are eligible regardless of where they apply, providing “no wrong door” access to coverage envisioned by the ACA.

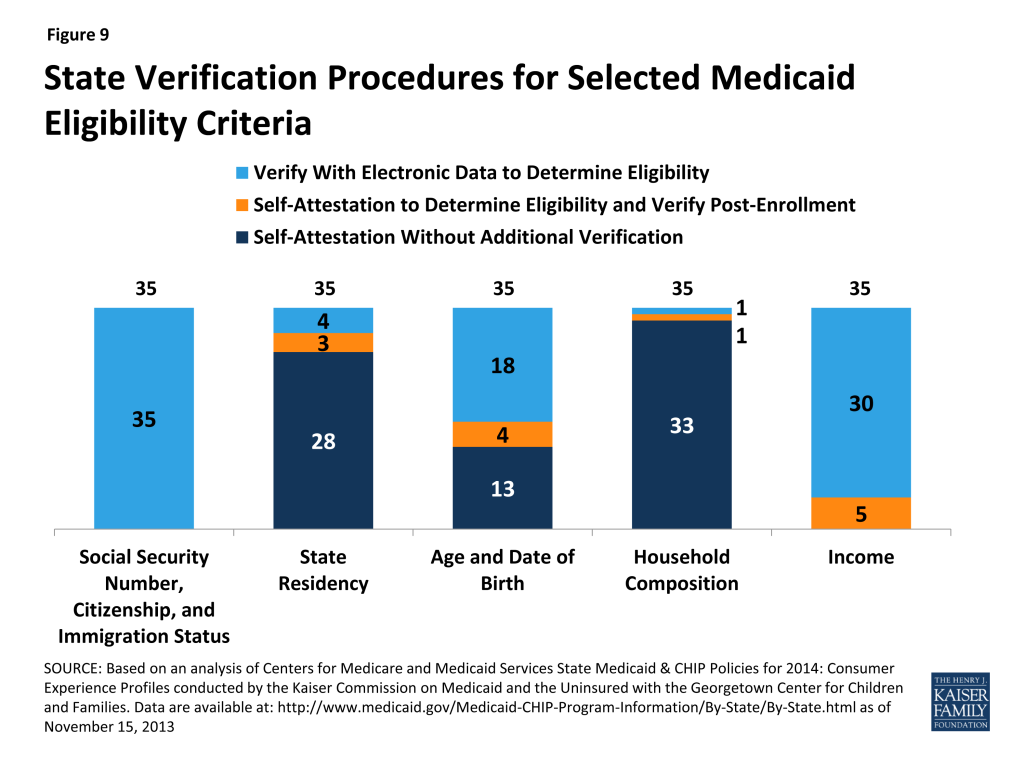

States are submitting verification plans to CMS that outline the electronic data sources and procedures they will use to verify eligibility criteria. As of November 15, 2013, 35 verification plans have been approved by CMS and made publicly available. States continue to have the option to accept self-attestation without additional verification for non-financial eligibility criteria except for Social Security Numbers, citizenship, and immigration status, which states are required to verify under law. The majority of reporting states will rely on self-attestation of state residency (28 of 35), and household composition (33 of 35), while fewer will do so for age and date of birth (13 of 35). The remaining states will either verify these criteria to determine eligibility or post-enrollment. For income, states must verify financial information from an electronic data source; however, this can be done post-enrollment after the state determines eligibility based on the individual’s attestation. All 35 reporting states will verify income through electronic sources, with 30 states doing so to determine eligibility and five (5) states verifying income post-enrollment. In addition, 23 states will conduct routine ongoing post-enrollment checks of financial information, although consumers also are required to report changes that may affect eligibility.

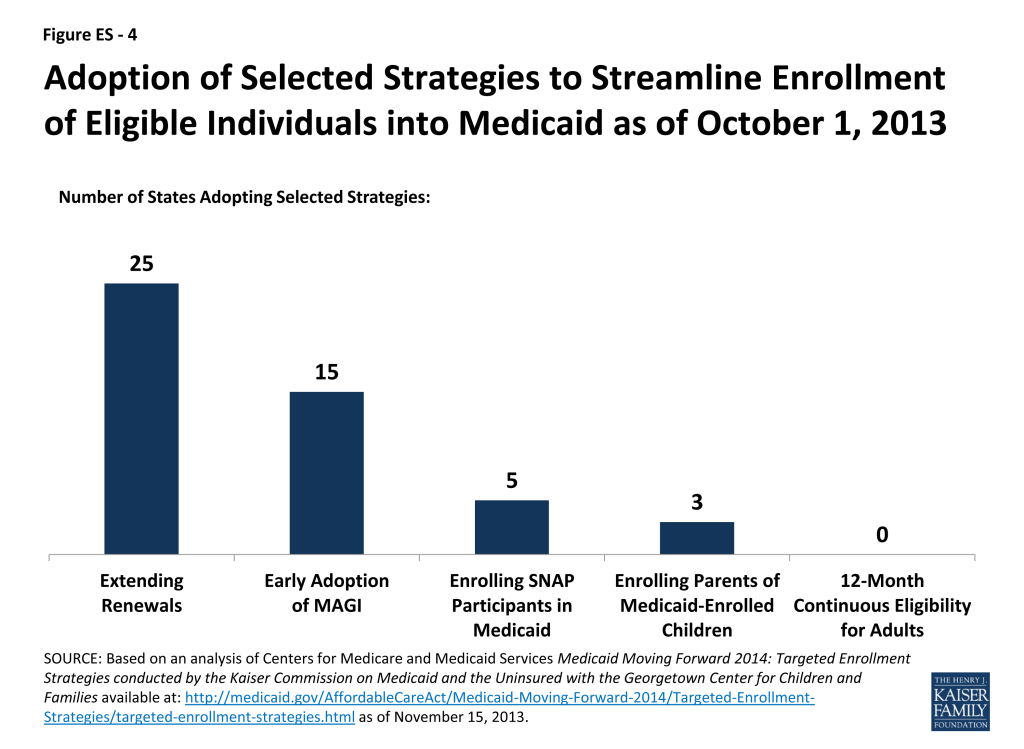

New Options to Facilitate Enrollment and Renewal

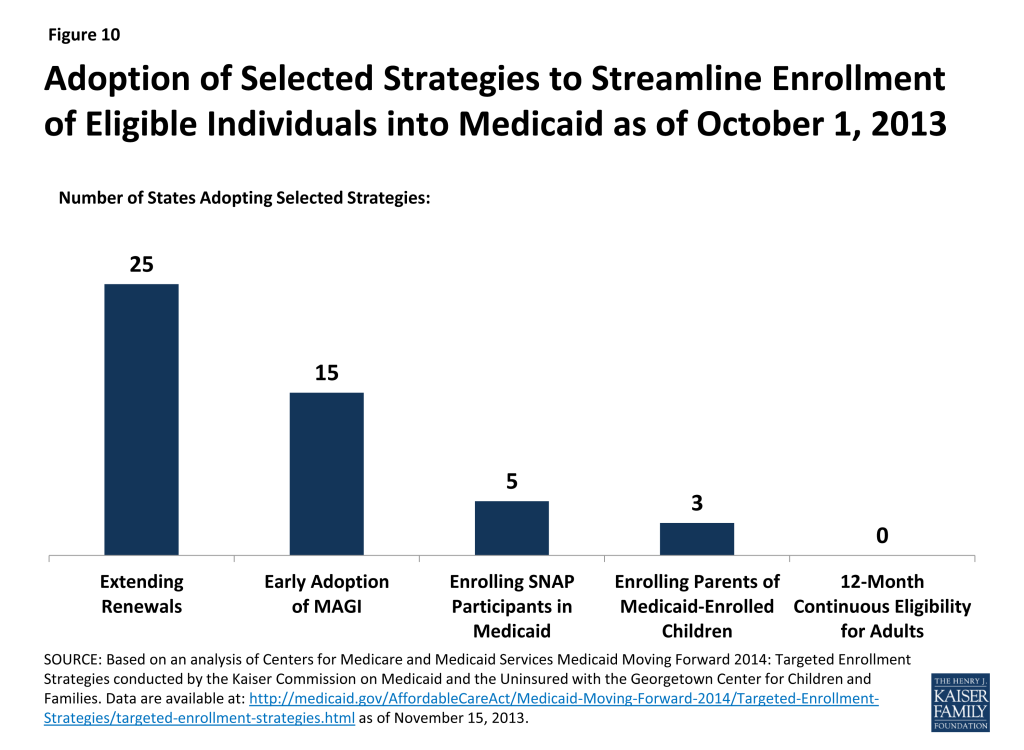

CMS has offered states five strategies to facilitate processing applications for large numbers of people who become newly eligible for Medicaid on January 1 and the transition to new enrollment processes. All of the approaches are intended to promote enrollment and retention, while minimizing administrative burdens for states. They include early adoption of MAGI-based eligibility standards, extending renewal periods for existing enrollees, enrolling eligible Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants in Medicaid based on available data, enrolling parents in Medicaid based on their children’s eligibility information, and providing 12-month continuous eligibility for parents and other adults. A state may adopt any of these facilitated enrollment approaches regardless of whether it plans to implement the Medicaid expansion. Nearly half (25) of states have taken up the option to extend renewals, 15 have adopted MAGI early, five (5) are enrolling individuals based on SNAP data, and three (3) are using eligibility data for children to enroll their parents (Figure ES- 4). Overall, 30 states have adopted at least one of the strategies, and 11 have adopted two or more of these approaches. Three (3) states (NJ, OR, and WV) have adopted four of the five.

Conclusion

Looking ahead to 2014, coverage for parents and other adults will significantly improve in the 26 states implementing the Medicaid expansion and eligibility levels for children and pregnant women will remain strong across states. As such, as the ACA is fully implemented, Medicaid offers the potential to significantly reduce the number of uninsured. Outreach and enrollment efforts will be key for increasing coverage and it will be important for these efforts to be ongoing throughout the year since Medicaid enrollment is not limited to the Marketplace’s open enrollment period. In contrast to gains in states expanding Medicaid, large coverage gaps will remain in the states that do not expand, leaving millions of poor uninsured adults without access to a new coverage option.

To date, states have made meaningful progress in implementing key provisions of the ACA to provide streamlined Medicaid eligibility and enrollment processes, but readiness varies considerably. Moreover, the technology problems that have hampered the launch of open enrollment through the new Marketplaces, particularly the federal Marketplace (HealthCare.gov), have led to delays in coordination across Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. However, even with these early implementation challenges, some states have been successfully enrolling people in Medicaid and several have gotten a significant jump-start through the facilitated enrollment strategies offered by CMS. In the coming months, work will continue to deploy new processes and systems to move toward the ACA’s vision of a simplified, consumer-friendly experience. As such, January 2014 will represent the first step toward a modernized, streamlined system to connect individuals to expanded coverage options as established through the ACA, but fully achieving that vision will require time, persistence, and a commitment to continual program improvement.

Introduction

As the first day of coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) approaches, states are continuing work to modernize their procedures and systems to implement key provisions of the law to simplify enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP and coordinate with the new Health Insurance Marketplaces, which opened their doors on October 1, 2013. Beginning January 1, 2014, low-income adults will become newly eligible for Medicaid in the 26 states that have chosen to implement the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Additionally, all states will transform their processes to align eligibility requirements for Medicaid, CHIP, and premium tax credits in the Marketplaces, streamline and modernize the application experience, and move toward a coordinated enrollment system across health coverage programs. Over the past year, states have made steady and significant progress preparing for these changes, but readiness varies considerably as 2014 nears, and work on implementation and process improvements will continue into the foreseeable future. This report provides an overview of key state Medicaid eligibility and enrollment policies that will be in effect as of January 1, 2014, based on data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The data provide insight into who will be eligible for Medicaid and CHIP across states and how individuals will enroll in coverage. (See Appendix Tables 1 through 9 for state-specific data on policies.)

Background

Throughout the last year, political divides continued over the ACA, but the law remains in place. With open enrollment for coverage through the new Marketplaces beginning on October 1st, the country is turning its attention to how the ACA is implemented, including a number of key provisions that impact Medicaid and CHIP eligibility and enrollment.

As enacted, the ACA extends Medicaid to nearly all adults at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) as of January 1, 2014. However, as a result of the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA, implementation of the Medicaid expansion is now effectively a state option. As of October 24, 2013, 26 states, including DC, are moving forward with the expansion (Figure 1). In some cases, CMS is working with states to develop expansion approaches under Section 1115 waiver authority (Box 1). There is no deadline for states to adopt the expansion, and several states are still actively considering the option. However, states delaying the expansion will miss out on the opportunity to receive the 100 percent federal funding for newly eligible individuals available in calendar years 2014 through 2016.

Regardless of state decisions to expand Medicaid, all states must implement new streamlined enrollment processes under the ACA. These procedures are designed to align eligibility determinations for Medicaid, CHIP, and premium tax credits in the Marketplaces. They also aim to establish a faster, more consumer-friendly enrollment experience, provide individuals multiple avenues to apply, and rely on electronic data instead of paper documentation to verify information where possible. To implement these new processes, almost all states are building new Medicaid eligibility and enrollment systems or conducting major upgrades of their existing systems. The federal government has provided time-limited 90 percent federal funding to support this system development work. CMS issued a final set of rules for these eligibility and enrollment changes in July 2013, providing guidelines for states as they were rewriting policies, revamping business processes, and developing their systems.

Box 1: Section 1115 Waivers and the Medicaid ExpansionTo date, of the states moving forward with the Medicaid expansion, three (AR, IA, and MI) are pursuing approaches that require Section 1115 waiver demonstration authority. As of November 15, 2013, Arkansas is the only state to have received approval. The state will use Medicaid funds to subsidize the purchase of coverage for Medicaid-eligible individuals through qualified health plans (QHP) in the Marketplace, with supplemental benefits and cost-sharing protections to meet minimum Medicaid standards. Iowa and Michigan await federal action their proposals. Additionally, there are a number of states with waivers that currently provide more limited coverage to parents and/or adults without dependent children. Most of these waivers are set to expire December 31, 2013, when this coverage could transition to the Medicaid expansion as it goes into effect. Some of these waivers were “bridge” waivers that were specifically designed to help states get an early start on the expansion. While most states with these expiring waivers are implementing the full Medicaid expansion, two states (Indiana and Oklahoma) not moving forward at this time. These states received approval to extend their waivers for one year, preserving their existing limited waiver coverage. However, many poor adults in these states who would have gained full Medicaid coverage under the expansion will not obtain access to a new coverage option in its absence and will likely remain uninsured.

For more details, see: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “A Look at Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers Under the ACA: A Focus on Childless Adults.” October 2013.

To further assist states in implementing the Medicaid provisions of the ACA, CMS offered new opportunities to facilitate enrollment. In May, the administration provided states five (5) new targeted enrollment and renewal strategies. These options are designed to help states accommodate application and enrollment increases as they transition to the new eligibility rules, with the hope of easing the administrative burden for states and simplifying the process for consumers.

To date, states have made significant progress in implementing these Medicaid and CHIP provisions but readiness varies considerably. Moreover, the technology problems that have hampered the launch of open enrollment through the new Marketplaces, particularly the federal Marketplace (HealthCare.gov), have led to challenges and delays with new processes designed to coordinate enrollment for Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. With 2014 quickly approaching, state implementation work remains in high gear and the coming weeks are important for states to meet specific milestones. States that will not be able to implement all of the new processes within the timeline established by the law are working with CMS to develop mitigation plans designed to help ensure individuals can still connect to coverage. Even with these early implementation challenges, some states have been successfully enrolling people into Medicaid as they have addressed technological glitches with their state Marketplace websites. Moreover, several states have gotten a significant jump-start through the facilitated enrollment strategies offered by CMS.

Medicaid And Chip Eligibility As Of January 1, 2014

Conversion to Modified Adjusted Gross Income to Determine Financial Eligibility

The ACA changes how financial eligibility will be determined for many Medicaid beneficiaries, standardizing the approach across states as well as health insurance affordability programs. Beginning January 2014, financial eligibility for parents, pregnant women, children, and the expansion adults will be based on Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI), as defined in the Internal Revenue Code. The move to MAGI for these non-elderly, non-disabled groups will result in some changes from current Medicaid rules related to calculating family size and income and will largely align Medicaid financial eligibility determinations with the standards used to determine eligibility for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions in the new Marketplaces.1 Aligning the determination requirements across all insurance affordability programs is intended to promote seamless coordination and avoid gaps or overlaps in eligibility.2

To carry out the transition to MAGI, states must convert their existing Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for these groups to MAGI-equivalent levels. Today there is significant variation across states and eligibility categories in how income disregards and deductions are applied to determine if an individual meets the financial eligibility requirements for Medicaid or CHIP. For example, a state often disregards certain income from an individual’s gross income (e.g., $90 for a working parent), deducts certain expenses (e.g., childcare), and then compares the result to a net income standard.3 When states transition to MAGI, they will discontinue the use of these disregards and deductions; instead, they will use the MAGI-equivalent income threshold that takes into account states’ previous use of disregards and deductions and apply a standard disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level in certain circumstances (Box 2). States worked with CMS to develop their converted MAGI levels using one of three available methods.4

Box 2: Use of the Five Percentage Point of the Federal Poverty Level Disregard Under MAGI

Under the new MAGI rules, a standard income disregard of five percentage points of the federal poverty level will be applied, but only if it affects an individual’s eligibility. For example, the Medicaid expansion for adults extends eligibility to 133 percent of the FPL. However, a parent with income at 138 percent of the FPL in a state implementing the expansion would be determined eligible because after the five percentage point disregard, he or she would meet the income standard of 133 percent FPL. Upper income levels reported in this brief take into account this standard disregard.

The MAGI converted thresholds are intended to approximate states’ existing eligibility levels in the aggregate to prevent individuals from losing coverage due to the transition to MAGI. While MAGI converted thresholds differ from existing levels, they are designed to result in roughly the same number of people being eligible under the new standard as would have been eligible under the old standard (Box 3). In some cases, the converted thresholds will be the income eligibility limits in place as of January 1, 2014. For example, in most of the states not implementing the Medicaid expansion, the income limit for parents will be the MAGI conversion of their existing parent eligibility level. The MAGI converted thresholds will also be used for a number of other purposes, including 1) maintaining Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children through October 1, 2019, as required by the ACA; 2) establishing minimum eligibility thresholds for parents, pregnant women, and other adults;5 3) determining the income levels at which premiums will apply; and 4) calculating the availability of the enhanced matching rate for newly-eligible adults.

Box 3: Understanding Differences Between January 2013 and January 2014 Eligibility Levels

Appendix Tables 1-3 show income eligibility levels for children, pregnant women, parents and other adults as of January 2013 and January 2014.

- In some cases, differences between the 2013 and 2014 levels represent state changes in eligibility policy, such as the Medicaid expansion to parents and other adults.

- In other cases, the differences stem from distinctions in how disregards were reflected in the January 2013 and January 2014 levels and do not represent a change in eligibility. For example, January 2013 eligibility levels for working parents reflect the maximum amount of income or earnings disregards, but not other deductions, that were applied in that state under previous rules. In contrast, the January 2014 MAGI-converted thresholds were calculated based on the average use of all disregards and deductions. For children and pregnant women, the January 2014 MAGI converted levels are higher than previously reported income thresholds because the January 2013 thresholds did not reflect states’ use of disregards or deductions.

States that had previously aligned children’s coverage levels across the different age groups merged the groups for conversion purposes in order to preserve the alignment. Otherwise, states were required to convert each eligibility category separately, including their Medicaid thresholds for infants, children ages one to five, and children ages six to eighteen. If the amount of the average disregards and/or the original threshold differed between the groups, disparate converted levels across the ages could result, as is seen in 18 states (Appendix Table 1). States have an opportunity to standardize their eligibility thresholds by adjusting the level for the older group to match that of the younger group, but only until December 31, 2013.6

Income Eligibility Limits as of January 1, 2014

Beginning in 2014, as part of the continuum of coverage, the ACA expands Medicaid to nearly all adults with incomes at or below 138 percent of the FPL. Moreover, the ACA requires states to maintain eligibility thresholds for children that are at least equal to those they had in place at the time the law was enacted through September 30, 2019. To help preserve the base of coverage upon which the ACA expansions build, states were also required to maintain eligibility levels for other groups, but this requisite will end on January 1, 2014.

Eligibility levels for parents and childless adults will significantly increase in the 26 states, including DC, that are expanding Medicaid to adults. Fifteen (15) of the 26 states moving forward with the Medicaid expansion already cover parents at or above the poverty level through Medicaid, but adults without dependent children are eligible for full Medicaid coverage in just nine (9) of these states (AZ, CO, CT, DE, DC, HI, MN, NY, and VT), of which only six (6) cover them at or above poverty (Appendix Table 2). In the expansion states, eligibility levels will increase for parents in 16 states and for childless adults in 24 states. Overall, the median eligibility threshold for parents in these states will increase from 106 to 138 percent of the FPL, while the median threshold for adults without dependent children will increase from 0 to 138 percent of the FPL. Three (3) states (CT, DC, and MN) will cover parents above the new expansion level of 138 percent of the FPL (Figure 2) and the District of Columbia and Minnesota will cover adults without dependent children above this level (Figure 3), although Minnesota will reduce eligibility levels for parents relative to its 2013 levels. In addition, four (4) other states (NJ, NY, RI, and VT) that previously extended Medicaid eligibility to parents with incomes above 138 percent of the FPL are reducing eligibility to 138 percent of the FPL as of January 2014; many of these parents will be eligible for tax credits to purchase coverage through the new Marketplaces.

In the 25 states not expanding Medicaid at this time, many poor parents and other adults will remain ineligible for coverage. In 21 of the states, eligibility levels for parents will be below 100 percent of the FPL, with eligibility levels remaining below half of poverty in 14 states. In addition, Maine and Wisconsin will reduce eligibility for parents from 133 to 105 percent of the FPL and 200 to 100 percent of the FPL, respectively, as the requirement to maintain coverage ends on January 1, 2014. Adults without dependent children generally will remain ineligible for full Medicaid coverage in non-expansion states. Overall, in these 25 states, the median eligibility level for parents will be just 47 percent of the FPL, with only four (4) states (AK, ME, TN, and WI) covering parents with incomes at or above poverty; only Wisconsin will provide full Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children. Parents and other adults with incomes above these limited Medicaid eligibility levels but below 100 percent of the FPL will fall into a coverage gap, which will leave nearly five million uninsured adults without access to a new coverage option (Box 4).

Box 4: The Coverage Gap Could Leave Nearly 5 Million Poor Adults Uninsured

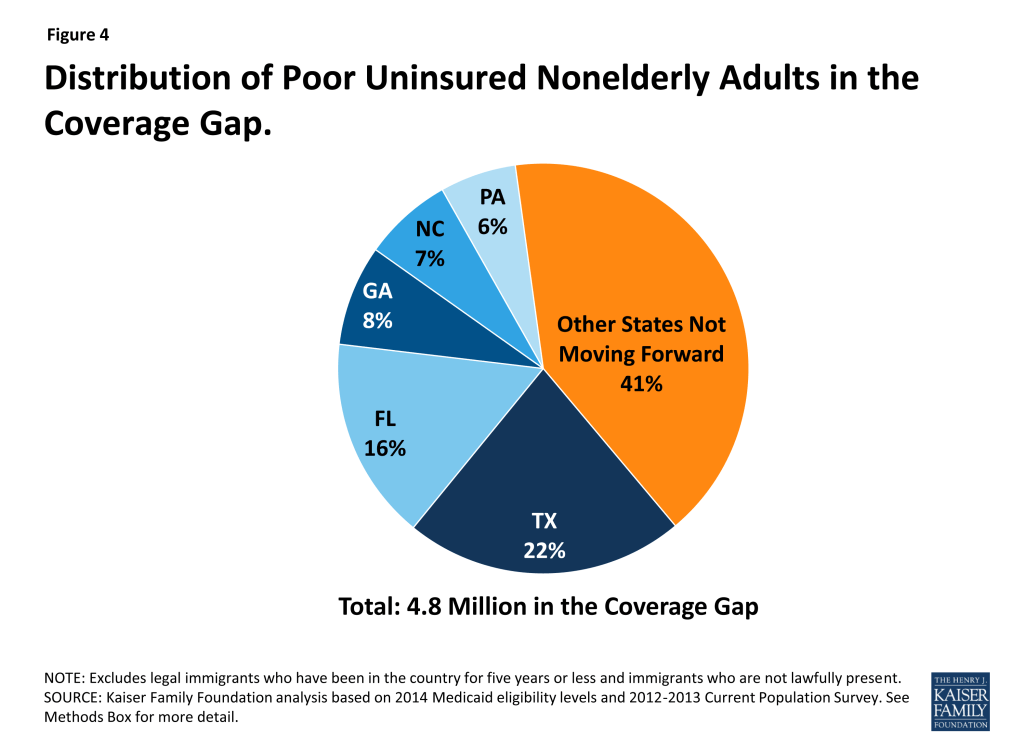

Nationally, nearly five million poor uninsured adults will fall into the “coverage gap” because they live in states that are not expanding Medicaid to adults at this time. Those in the gap earn too much to qualify under their state’s Medicaid eligibility guidelines and too little to qualify for premium tax credits to purchase coverage through the new Marketplaces. More than one-third of those falling in the gap reside in just two states – Texas (22 percent) and Florida (16 percent) (Figure 4).

See: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid.” October 2013.

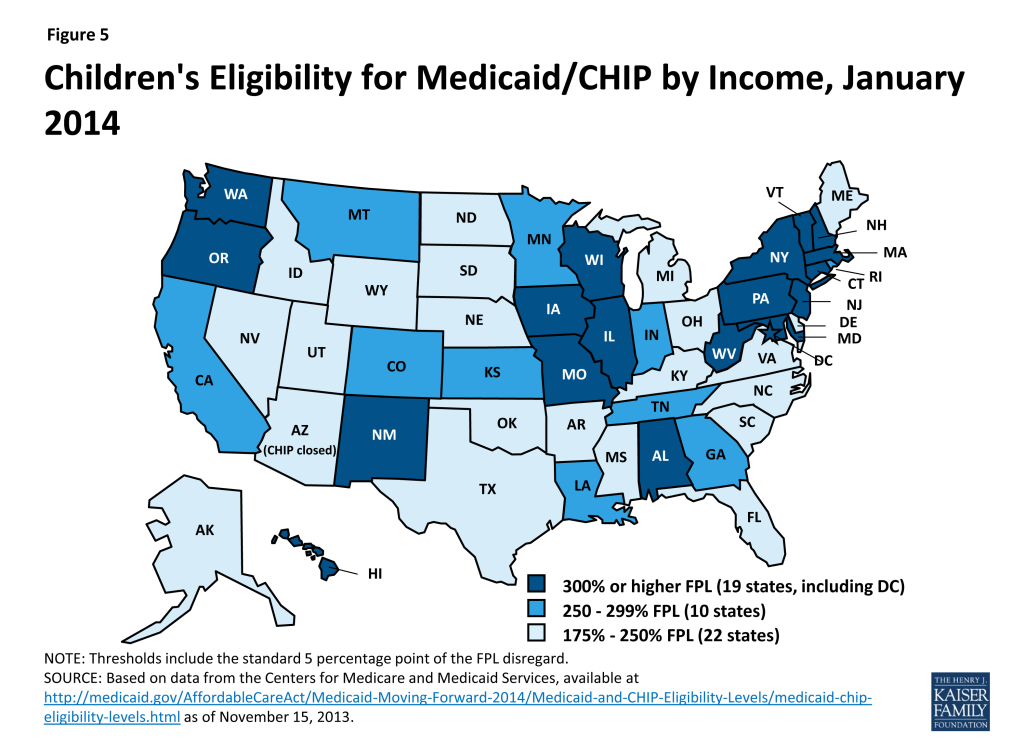

Coverage for children through Medicaid and CHIP will remain strong in 2014, with the median eligibility level at 255 percent of the FPL. More than half of the states (30, including DC) will cover children in families with incomes at or above 250 percent of the FPL and 20, including DC, will cover children in families with incomes at or above 300 percent of the FPL (Figure 5 and Appendix Table 1). Moreover, 18 states currently covering older children up to 133 percent of the FPL in separate CHIP programs will shift coverage for these children to Medicaid, as the ACA establishes a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138 percent of the FPL for all children up to age 19.7 Prior to the ACA, states were required to cover children up to age 6 with incomes up to 133 percent of the FPL through Medicaid, but the minimum eligibility level for older children was 100 percent of the FPL. This shift from CHIP to Medicaid must occur regardless of whether the state is expanding Medicaid to adults; states will continue to receive the enhanced CHIP matching rate for uninsured children in this income group. CMS has been assisting states with this shift and, in some cases, may permit an alternative transition approach, such as at a child’s next regularly scheduled renewal rather than by January 1, 2014.

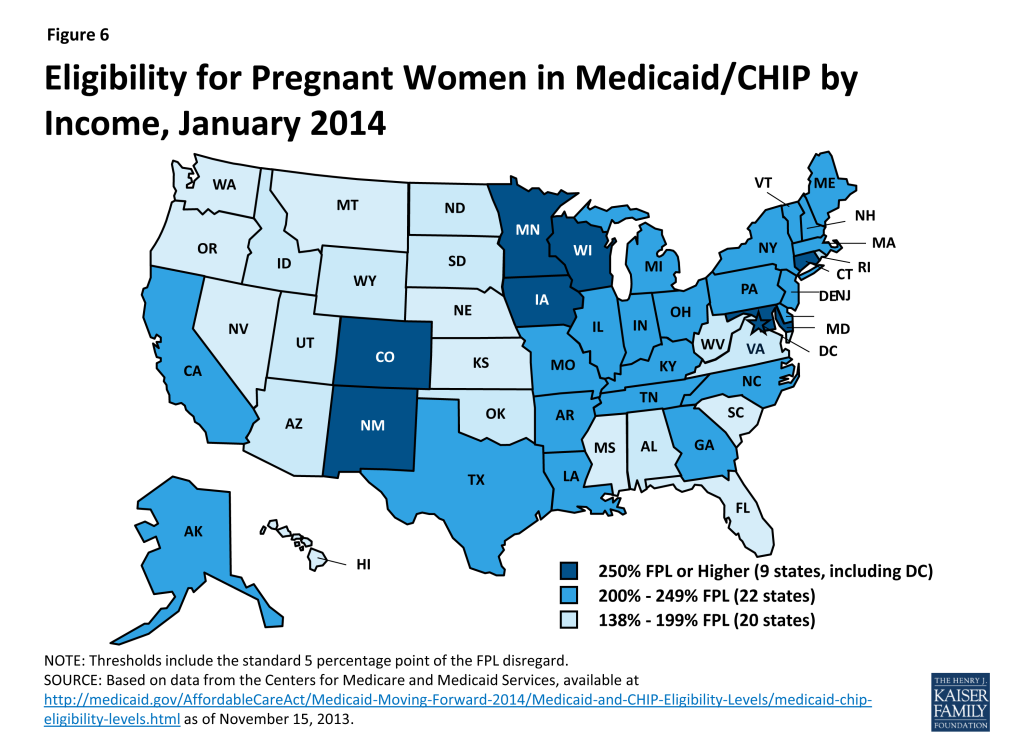

Despite two (2) states reducing eligibility, most will continue to cover pregnant women above the federal minimum standards. As of January 1, 2014, the median eligibility level for pregnant women will be 203 percent of the FPL, with 31 states, including DC, covering pregnant women at or above 200 percent of the FPL (Figure 6 and Appendix Table 3). Two states, Oklahoma and Virginia, will reduce eligibility for pregnant women from 185 to 133 percent of the FPL and 200 to 143 percent of the FPL, respectively, as the requirement to maintain coverage ends on January 1, 2014. Louisiana has also indicated plans to reduce eligibility for pregnant women as of January 1, 2014, but this change was not reflected in the data from CMS as of November 15, 2013.8

Eligibility for parents and other adults will continue to lag behind that of children and pregnant women. While coverage for parents and childless adults will markedly improve in states implementing the Medicaid expansion, their median eligibility levels will still remain significantly lower than that of children and pregnant women. These disparities in eligibility across groups will be even starker in states that are not expanding Medicaid (Figure 7).

Connecting People To Coverage Through Streamlined Enrollment Processes

The ACA envisions seamless and timely access to the continuum of coverage options regardless of where or how someone applies. To achieve these objectives, the ACA establishes new expectations for simplifying the application process, coordinating enrollment, and moving toward paperless verification of eligibility. Many of these changes accelerate successful state strategies in harnessing technology to make the process work better for both individuals and state agencies.

Applying for Coverage

The ACA requires Medicaid, CHIP, and the new health insurance Marketplaces to adopt a single, streamlined application that screens eligibility for all coverage options. To this end, HHS created a consumer-tested model application, which states can customize to better fit their programs. For example, states can substitute state agency names, logos, and phone numbers. States can also eliminate questions that aren’t applicable, such as how long a child has been uninsured in a state that does not impose a waiting period in CHIP. Alternatively, states may develop their own single, streamlined application, subject to HHS approval. However, alternative applications may only include questions relevant to the eligibility and administration of all of the insurance affordability programs, and only for individuals who are applying for coverage.

Most states (43) will use a state alternative online application, while seven (7) will adopt the HHS model online application. Fewer states (30) are using or plan to use a state alternative for their paper application (Figure 8). In 32 of the states using an alternative application, the version that is initially available will need further revisions to fully comply with the ACA standards, for example, by removing questions that are not relevant to eligibility. Notably, in 15 states, multi-benefit applications are available that allow individuals to simultaneously apply for health coverage and other benefits such as food or childcare assistance. Like the alternative application, a multi-benefit application must ask the relevant questions for all health insurance affordability programs. It must also clearly indicate which questions are optional for determining eligibility for health insurance coverage only.

State Medicaid agencies are required to make the single streamlined application available through multiple modes, including online, by phone, and on paper by January 1, 2014. As of October 1, 2013, 43 of 50 reporting states have deployed a single, streamlined application through their Medicaid agency, with 43 state Medicaid agencies having a paper version in place and 36 having launched an online version. The seven (7) remaining reporting states are in the process of developing their single, streamlined applications with nearly all anticipating completion by January 1, 2014 (Appendix Table 4). In the interim, these states are continuing to utilize their existing Medicaid applications and individuals who may be eligible for premium tax credits are being directed to apply through the federal Marketplace.9 Looking ahead states will continue work to make the single streamlined application available through all required modes, although some state agencies may not have all of these avenues available until later in 2014. In these cases, CMS is working with states to develop mitigation plans to help ensure consumers can connect to coverage.

Coordinating Enrollment Across Health Coverage Programs

Coordination between Medicaid, CHIP, and the Marketplace will be key for achieving the ACA’s no wrong door approach to coverage. States have the option to decide whether the Marketplace (State-based (SBM) or Federally-facilitated (FFM)) will determine eligibility for Medicaid and CHIP or assess potential eligibility and send the case to the Medicaid and CHIP agency for a final determination.10 To facilitate coordination across programs and prevent individuals from having to provide information more than once, state agencies and Marketplaces are expected to electronically transfer an account with all of the individual’s information promptly and without undue delay and are not allowed to request any information or documentation that the individual has already provided.

Coordination processes will vary based on whether the Marketplace has the authority to assess or determine Medicaid eligibility. For example, if an individual applies through a Marketplace that determines Medicaid/CHIP eligibility, the Marketplace will make a final eligibility determination and transfer the account of any eligible individual to the Medicaid/CHIP agency for enrollment, without a second review of eligibility. In contrast, if an individual applies through a Marketplace that assesses Medicaid/CHIP eligibility, it will transfer the account for any individual assessed as potentially eligible for Medicaid/CHIP for a final determination by the Medicaid/CHIP agency. If determined eligible for Medicaid/CHIP, the individual will be enrolled. If determined ineligible for Medicaid/CHIP, the agency will transfer the individual’s account back to the Marketplace for a review of eligibility for premium tax credits. As a result, some individuals may be transferred back and forth between coverage programs before they are determined eligible. Among the 34 federal or partnership Marketplace states, as well as Idaho and New Mexico (which are initially relying on the FFM to handle Marketplace eligibility and enrollment), the FFM will assess Medicaid/CHIP eligibility in 24 states and make final Medicaid/CHIP eligibility determinations in 12 states. In seven (7) of these 12 states, the FFM will make determinations temporarily until the state’s Medicaid/CHIP eligibility system is able to meet the ACA requirements (Appendix Table 5).

The ability to electronically transfer individual accounts between state Medicaid/CHIP agencies and the Marketplaces is in various stages of development. All but two (2) of the 17 states with SBMs share an integrated or linked technology system that determines eligibility for all insurance affordability options and facilitates the next steps for enrollment. However, in states using the FFM, electronic transfers of individual accounts between the Marketplace and Medicaid/CHIP agencies are essential for coordinating enrollment. Due to ongoing technological challenges with the FFM, these transfers have been delayed. As such, alternative strategies have been put into place. For example, until the FFM can begin transferring electronic accounts to state Medicaid and CHIP agencies, it is sending batches with basic data on individuals the FFM has assessed as potentially eligible for Medicaid/CHIP. Similarly, if a state Medicaid/CHIP agency is unable to screen for premium tax credits and transfer the account to the FFM it can advise potentially-eligible individuals to apply directly through the FFM. Moving forward, implementing electronic account transfers will be key to minimizing burdens on consumers and ensuring that they only need to submit a single application, as envisioned by the ACA’s no wrong door approach to coverage.

Verification of Eligibility Criteria

Beginning in January 2014, states are expected to rely on trusted electronic data sources rather than paper documentation to verify eligibility. Only when information cannot be obtained through an electronic data source or is not ‘‘reasonably compatible’’ with information provided by the consumer can additional information, including paper documentation, be requested. To facilitate electronic verification, states are expected to establish data linkages with federal and state data sources. A federal data hub provides access to information from multiple federal agencies including the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Social Security Administration (SSA), and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). In addition, states are commonly accessing databases that collect state wage information, unemployment compensation information, vital statistics, and eligibility data for other public programs. Ultimately the goal is for these data interfaces to provide real-time or immediate access to data, however, in some cases, data may continue to be exchanged in a process that “batches” requests for information for multiple people on a daily or other periodic basis. In these instances, data is also returned in batches, which may result in a lag before the requested data is available and can be used to verify eligibility. When this is the case, states may pend or hold the application until the data is received and reviewed. Alternatively, some states may use the data to verify eligibility after they have enrolled the individual based on his/her self-attestation.

States are submitting verification plans to CMS, which outline the electronic data sources and procedures they will use to verify eligibility criteria. For the majority of states, the heightened reliance on electronic verification requires a redesign of business practices to implement a real-time, data-driven approach to verification. Each state must file a plan with CMS describing the agency’s verification policies and procedures including the data sources used at application and renewal, the frequency of data checks, and how the state determined the usefulness of electronic data sources.11 While there is no formal process for federal approval, the verification plans are used to confirm state implementation of the new standards established by the ACA, and will be used for quality and audit purposes going forward.12 As of November 15, 35 verification plans have been approved and made publicly available.

States continue to have the option to accept self-attestation for all non-financial eligibility criteria except where otherwise required by statute. Under law, states must verify Social Security Numbers (SSNs), citizenship, and immigration status. For other non-financial aspects of eligibility (e.g., state residency, age/date of birth, and household composition), states have more flexibility and may choose 1) to rely on self-attestation without additional verification, 2) rely on self-attestation to make the eligibility determination and verify post-enrollment, or 3) verify data to determine eligibility. For pregnancy, states must accept self-attestation, although they may request verification if multiple babies are expected. If states verify non-financial eligibility criteria, they are expected to use electronic data and eliminate or minimize requirements for paper documentation at both application and renewal. Even in states accepting self-attestation without further verification, the state may have access to electronic data for some people (for example, if the consumer is also enrolled in SNAP), which may be used to confirm eligibility.13 Moreover, states always have the option to verify any data that it considers questionable. All 35 reporting states will verify SSNs, citizenship, and immigration status through federal data sources as required by law. Most states plan to rely on self-attestation of state residency (28 of 35) and household composition (33 of 35). In contrast, the majority of the reporting states (22 of 35) plan to verify age and date of birth, with 18 verifying data to make the eligibility determination and 4 doing so post-enrollment (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 6).

For income, states must verify financial information from an electronic data source; however, this can be done post-enrollment after the state determines eligibility based on the individual’s attestation.14 States also may accept self-attestation for certain types of income that cannot be verified through an electronic source. All 35 reporting states will verify income through electronic sources, with 30 states doing so to determine eligibility and five (5) states verifying income post-enrollment (Figure 9 and Appendix Table 7). In addition, 23 states will be conducting routine ongoing post-enrollment checks of financial information to identify changes in income over time, although the frequency of these checks varies. Consumers are still required to report changes that may impact their eligibility.

States are relying on a variety of data sources to verify eligibility criteria. States have latitude to determine if a particular income data source is “useful” but neither the age nor cost of obtaining the data can be used as a reason to continue requiring paper documentation. SSNs and citizenship will be verified via an electronic match with the SSA, while immigration status will be verified through the DHS Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) database. Frequently-used data sources for other non-financial eligibility criteria include the SSA, the Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS), and state databases, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV), vital statistics, and public assistance records for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) and SNAP. The most common data sources that states will use to verify income at application, renewal and post-enrollment include the IRS, SSA, state wage data, state unemployment data and commercial databases that provide payroll information for some employers, such as TALX (also known as the Work Number) (Appendix Table 8).

States may set “reasonable compatibility” standards to address situations in which self-attested income and electronic sources are inconsistent. In Medicaid and CHIP, data are always considered reasonably compatible if the individual’s self-attested income and the electronic data source are both at, below, or above the income standard—in these cases, the difference does not impact eligibility. In cases where self-attested income is above the standard and electronic data are below, or vice versa, states have flexibility to define when inconsistencies between the two sources are considered reasonably compatible. If the difference between the electronic data and the consumer’s self-attestation is within the reasonable compatibility standard, the self-attestation is used. If the data are not reasonably compatible under this standard, the state may accept a reasonable explanation of the difference and/or request paper documentation of income

- For cases in which self-attested income is below the income standard, but electronic data sources show income above the standard, 27 of the 35 reporting states have set a reasonable compatibility standard. If the data are not within the reasonable compatibility standard, 26 of the 35 states will ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference before requesting paper documentation, while nine (9) will always request paper documentation to verify income.

- For cases in which self-attested income is above the income standard, but electronic data sources show income below the standard, the vast majority of states are not setting a reasonable compatibility standard. Thirty (30) of 35 reporting states will accept the self-attestation, deny Medicaid eligibility, and screen for eligibility for premium tax credits, regardless of the size of the discrepancy between the attestation and the electronic data source. One state (NJ) will also accept self-attested income if the difference is no more than 10 percent, the state’s reasonable compatibility standard. Given that individuals may overstate their income if they are not aware that certain income and pre-tax contributions (e.g., dependent care expenses) should not be counted, this policy may result in a Medicaid denial and determination for premium tax credits even though the individual is, in fact, eligible for Medicaid. Three (3) states ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference before requesting paper documentation, while two (2) will always require paper documentation to verify income and process the eligibility determination.

| Table 1: Reasonable Compatibility Approaches Used by Medicaid Agencies at Application | |

| Total Number of States Reporting | 35 |

| If attestation and data are both | |

| Below the income limit, determined eligible for Medicaid | 35 (required) |

| Abovethe income limit, determined ineligible for Medicaid and screen for advance premium tax credits | 35 (required) |

| If attestation is below and data are above the income limit: | |

| Determine eligible for Medicaid if within reasonable compatibility standard | 27 |

| If not within the reasonable compatibility standard: | |

| Ask for reasonable explanation from individual | 26 |

| Require paper documentation of income | 9 |

| If attestation is above and data are below the income limit: | |

| Determine ineligible for Medicaid, screen for advance premium tax credits | 30 |

| Ask for a reasonable explanation of the difference from the individual* | 3 |

| Require paper documentation of income | 2 |

| *Note if the reasonable explanation is not sufficient, states may ask for paper documentation.Source: Based on analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services State Medicaid & CHIP Policies for 2014: Medicaid/CHIP Verification Plans conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured with the Georgetown Center for Children and Families. Data are available at: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-State/By-State.html | |

New Options To Facilitate Enrollment And Renewal

To facilitate processing applications for large numbers of people who become newly eligible for Medicaid on January 1, CMS has offered states five strategies to help manage the transition. Highlighted in a May 17, 2013 letter to state officials,15 these approaches are intended to promote enrollment and retention, while smoothing the administrative burden as states shift to new eligibility processes. A state may adopt any of these facilitated enrollment approaches regardless of whether it plans to implement the Medicaid expansion, and as of October 1, a number of states have taken up at least one of these options (Figure 10 and Appendix Table 9).

Overall, 30 states have adopted at least one of the strategies, and 11 have adopted two or more of these approaches. Three (3) states (NJ, OR, and WV) have adopted four of the five. These strategies include:

- Extending Renewal Periods. The ACA protects individuals currently enrolled in Medicaid from losing coverage solely as a result of the conversion to MAGI-based eligibility until March 31, 2014 or their next renewal date (whichever is later). To abide by this provision, states would need to apply both the new MAGI rules and the existing rules to determine eligibility for those whose coverage is up for renewal between before March 31, 2014. To avoid this duplication of effort, CMS offered states the option to extend renewal dates beyond this three-month transition period and begin applying only MAGI-based eligibility rules to all regularly scheduled renewals beginning on April 1, 2014. States have flexibility to structure how the delays will take place, for example, by delaying renewals for 90 days, as long as they establish a reasonable timeframe within which the renewals will be completed. Twenty-five (25) states have taken up this strategy, many adopting it over a longer timeframe than those scheduled for the first quarter of 2014.

- Early Adoption of MAGI Eligibility. Through the initial months of open enrollment (October through December 2013), all individuals applying for or renewing Medicaid/CHIP coverage should have their eligibility determined under existing rules and also be assessed for eligibility using the new MAGI-based methodologies to determine if they will be eligible for coverage as of January 1, 2014. To avoid having to utilize two sets of eligibility rules, and possibly two different eligibility systems during this time, CMS offered states the option to adopt the MAGI methodology as of October 1 for all eligibility determinations going forward, which 15 states accepted.16

- Enrolling Eligible Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants in Medicaid. This temporary option is available to states through the end of 2015, and allows them to use data available from SNAP (also known as food stamps) to enroll eligible participants in Medicaid. To qualify for SNAP, a household’s gross income cannot generally exceed 130 percent of the FPL, which aligns well with the new Medicaid threshold of 138 percent of the FPL, although states may use this option for a subset of SNAP participants. Because SNAP enrollment data include verified information for many of the criteria necessary to determine Medicaid eligibility, a state can use that information along with a signed letter or phone call as a Medicaid application and enroll individuals once certain non-financial information, including citizenship or immigration status, is verified. Five (5) states (AR, IL, NJ, OR, and WV) have adopted this approach.

- Enrolling Parents in Medicaid Based on their Children’s Eligibility Data. In 2010, 3.5 million uninsured parents who could gain Medicaid coverage under the ACA expansion already had a child who was enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP.17 CMS offered states a temporary opportunity to expedite the enrollment of these parents. States can adopt this option by reactivating recent parent applications that have been denied or by reviewing children’s cases to identify eligible parents and requesting any additional information needed to make an eligibility determination. States may also send parents a pre-populated application or ask for additional information from the parent on the child’s renewal form. Three (3) states (NJ, OR, and WV) have moved forward with this approach.

- 12-Month Continuous Eligibility for Parents and Other Adults. States have long had the option to provide 12-month continuous eligibility for children regardless of certain changes in family circumstances, including fluctuations in income. Almost half of states (23) have adopted this option in Medicaid, strengthening the continuity of care and promoting ongoing coverage of children. CMS has offered to extend this effective retention strategy to adults and is working on implementation details.18

Two of these strategies, enrolling eligible SNAP participants and enrolling parents based on their children’s eligibility data, allow states to get a jump-start on their Medicaid expansions by significantly streamlining the process and utilizing data already available to states. Experiences in the four states that have already launched these strategies indicate they can be highly successful in connecting people to coverage, reaching a significant share of adults eligible for the Medicaid expansion while minimizing burdens for both eligibility staff and individuals and reducing traffic through enrollment systems. Overall, in these four states, over 223,000 individuals have been enrolled through these strategies as of November 15, 2013.19

Conclusion

Looking ahead to 2014, coverage for parents and other adults will significantly improve in the 26 states implementing the Medicaid expansion and eligibility levels for children and pregnant women will remain strong across states. As such, as the ACA is fully implemented, Medicaid offers the potential to significantly reduce the number of uninsured. Outreach and enrollment efforts will be key for increasing coverage and it will be important for these efforts to be ongoing throughout the year since Medicaid enrollment is not limited to the Marketplace’s open enrollment period. In contrast to gains in states expanding Medicaid, large coverage gaps will remain in the states that do not expand, leaving millions of poor uninsured adults without access to a new coverage option.

To date, states have made meaningful progress in implementing key provisions of the ACA to provide streamlined Medicaid eligibility and enrollment processes, but readiness varies considerably. Moreover, the technology problems that have hampered the launch of open enrollment through the new Marketplaces, particularly the federal Marketplace (HealthCare.gov), have led to delays in coordination across Medicaid, CHIP, and Marketplace coverage. However, even with these early implementation challenges, some states have been successfully enrolling people in Medicaid and several have gotten a significant jump-start through the facilitated enrollment strategies offered by CMS. In the coming months, work will continue to deploy new processes and systems to move toward the ACA’s vision of a simplified, consumer-friendly experience. As such, January 2014 will represent the first step toward a modernized, streamlined system to connect individuals to expanded coverage options as established through the ACA, but fully achieving that vision will require time, persistence, and a commitment to continual program improvement.

Endnotes

- A number of income sources, such as child support and Social Security benefits, which are currently counted for Medicaid eligibility, are excluded from taxable income and MAGI-based determinations. States also take a different approach to determining the size of family, often based on who is applying for benefits. But under the new MAGI rules, household size will be based on the tax-filing unit, with all individuals claimed as dependents included when determining that taxpayer’s family size. ↩︎

- Despite the attempt at coordination, there will be cases in which the definitions of household and income will not align across the various coverage programs. For example, Medicaid/CHIP eligibility will still be based on monthly income, whereas eligibility for premium credits in the Marketplace will be based on annual income. Additionally, certain types of income, such as educational grants, are not included when determining eligibility in Medicaid, but are when determining eligibility for Marketplace coverage. The household composition, such as for married couples, may also be counted differently in Medicaid. However, there is a safe harbor provision for individuals and families who are determined ineligible for Medicaid by the Medicaid agency, but are found to have income below 100 percent of the FPL based on the methods used by the Marketplace. In such cases, Medicaid eligibility will be determined using the tax definition (i.e., what was used by the Marketplace), allowing the applicant(s) to secure coverage in Medicaid and avoid a gap in coverage. ↩︎

- Note that not all states apply earnings disregards or other deductions and may simply use a gross income standard. ↩︎

- CMS provided states with the option of using the HHS-standardized method or a state-proposed alternative for calculating the MAGI-equivalent standards. Most states used a standard model that simulated the average value of disregards and deductions for families with net income within 25 percentage points of a state’s upper eligibility limit. This value is expressed as a percentage of the FPL and added to the state’s existing eligibility level to create the new MAGI-equivalent standard. Alternatively, states could take this same approach using their own administrative data on the use of disregards and deductions. States could also work with HHS to develop their own methodology to more adequately fit unique circumstances, for example, to account for unusual disregards. Of the 46 MAGI conversion plans available, just three (3) states (AK, NE, and NV) chose this alternative approach. C. Mann, Director of Centers for Medicaid and CHIP Services letter to State Health Officials and State Medicaid Directors, SHO #12-003 (December 28, 2012). ↩︎

- In an attempt to simplify eligibility categories, the ACA collapses many of the existing ones into three broad groups: parents, pregnant women, and children under age 19. States will set income eligibility standards for parents, pregnant women, and children subject to federally specified minimums and maximums. The minimum eligibility level for parents is tied to states’ historical eligibility levels for Aid to Families with Dependent Children, while the minimum level for pregnant women and children generally is 133 percent of the FPL, although may be higher in some states for pregnant women. ↩︎

- In order to equalize their eligibility thresholds, states would need to use a “less restrictive methodology” for determining income, effectively disregarding the income between the two converted thresholds for the older children. This option, under section 1902(r)(2), is no longer available with the switch to the new MAGI methodology on January 1, 2014. ↩︎

- While the new mandatory minimum eligibility threshold is 133 percent of the FPL, the standard five percentage point of the FPL disregard is included to represent the highest threshold at which an older child may be eligible for Medicaid. ↩︎

- Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. “Changes to Medicaid Eligibility Criteria Effective January 1.” Friday, August 16, 2013 available at: http://www.dhh.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/newsroom/detail/2854 ↩︎

- Colorado and Maine are using a two-step process, where those who may be eligible for premium tax credits are directed to additional questions that will need to be answered to determine eligibility for premium tax credits in the marketplace. These states are considered by CMS to have a single, streamlined application. ↩︎

- If a Marketplace is operated by a non-governmental agency, the authority to conduct final Medicaid determinations is limited to MAGI-based determinations. In some cases in which the Marketplace is operated by a governmental agency, the Marketplace may be able to make non-MAGI determinations or enter into contracts with government agencies to do so. ↩︎

- Verification Plan Template – Guidance and Instructions; Phase I – MAGI-based Eligibility. ↩︎

- CMS eligibility audits through the Payment Rate Error Measurement (PERM) review and Medicaid Eligibility Quality Control (MEQC) evaluate whether eligibility determinations are made in accordance with state policy. Verification plans and other documents describing state policies and procedures are the basis for conducting the audits. ↩︎

- These states are counted under the “Self-Attestation Accepted at Application without Additional Verification” column, as this is the process they will use for the majority of their population. ↩︎

- Section 1137 of the Social Security Act requires states to have in effect an income and eligibility verification system. 42 CFR 435.948(a)(1) requires states to verify information (to the extent the agency determines such information is useful), related to wages, net earnings from self-employment, unearned income and resources from the State Wage Information Collection Agency (SWICA), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Social Security Administration (SSA), the agencies administering the State unemployment compensation laws, the State administered supplementary payment programs under section 1616(a) of the Act, and any State program administered under a plan approved under Titles I, X, XIV, or XVI of the Act. ↩︎

- C. Mann, Director of Centers for Medicaid and CHIP Services letter to State Health Officials and State Medicaid Directors, SHO #13-003 (May 17, 2013). ↩︎

- Note that Pennsylvania is adopting the early MAGI option in its Medicaid program only. ↩︎

- M. Heberlein, et al., “Medicaid Coverage for Parents under the Affordable Care Act,” Georgetown University Center for Children and Families (June 2012). ↩︎

- The option was in Arkansas’ waiver application, but because the state could not secure the 100 percent federal match for these adults for their full-year of coverage, the state chose not to go forward. The newly eligible matching rates is only applicable for individuals who meet the statutory eligibility requirements, and as such is not available to those individuals who remain enrolled but whose income or other eligibility criteria changes over the year in ways that would make them no longer eligible under the category. New York had pre-existing waiver approval to extend 12-month continuous eligibility to parents and New Mexico included the policy for all adults in its recently approved waiver, but neither state has yet implemented it. ↩︎

- J. Guyer, et al., “Fast Track to Coverage: Facilitating Enrollment of Eligible People into the Medicaid Expansion,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (November 2013). ↩︎