What Could U.S. Budget Cuts Mean for Global Health?

Issue Brief

Key Points

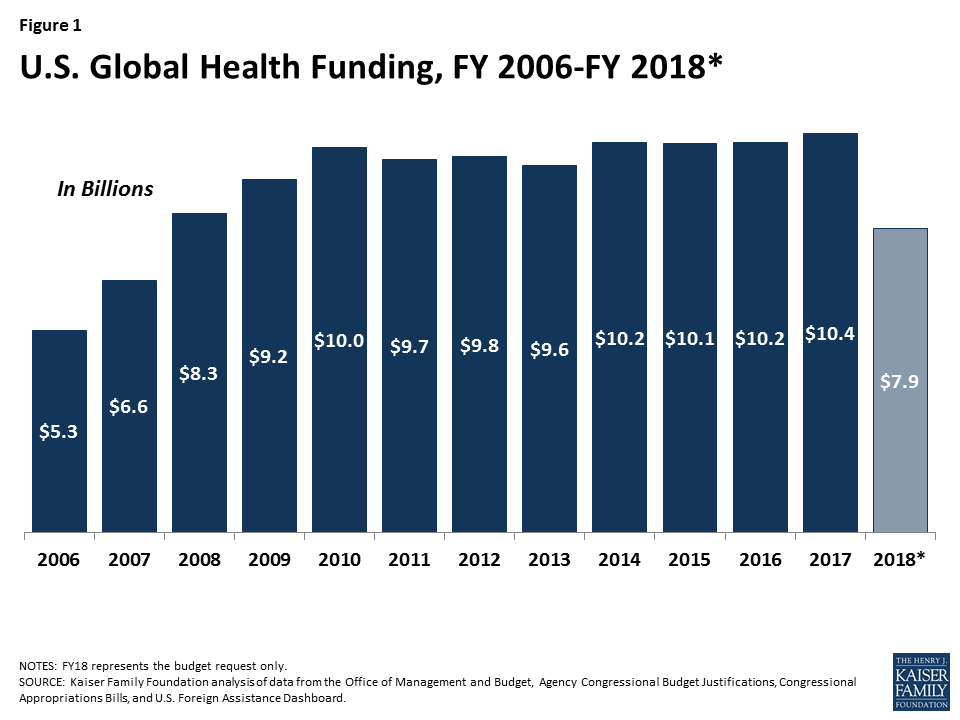

- President Trump’s FY 18 budget request to Congress includes unprecedented cuts to global health. If enacted, they would total approximately $2.5 billion and bring funding below FY 08 levels. Still, the President’s budget is just the first step in a longer process where Congress now takes center stage.

- We developed “budget impact models” to assess the impact of funding cuts. We modeled three budget scenarios – the Administration’s proposed cuts as well as two more modest decreases – in countries that receive U.S. global health assistance for HIV, TB, family planning, and maternal, newborn, and child health.

- Based on our models, the potential health impacts of these one-year cuts is significant across all three budget scenarios. For example, depending on the size of the cut, we estimate that starting next year:

- Additional new HIV infections would range from 49,100 to 198,700; the number of people on antiretrovirals could decline by more than 830,000 in the steepest budget cut scenario;

- Additional new TB cases would range from 7,600 to 31,100;

- The number of women and couples receiving contraceptives would decline, ranging from 6.2 million to almost 24 million; the increase in the number of abortions would range between 778,000 to almost 3 million; and

- Additional maternal, newborn, and child deaths would range between 7,000 and 31,300.

- While the fate of this year’s global health budget remains uncertain, these models illustrate the relationship between such decisions and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries and provide one important tool for assessing future budget choices.

Introduction

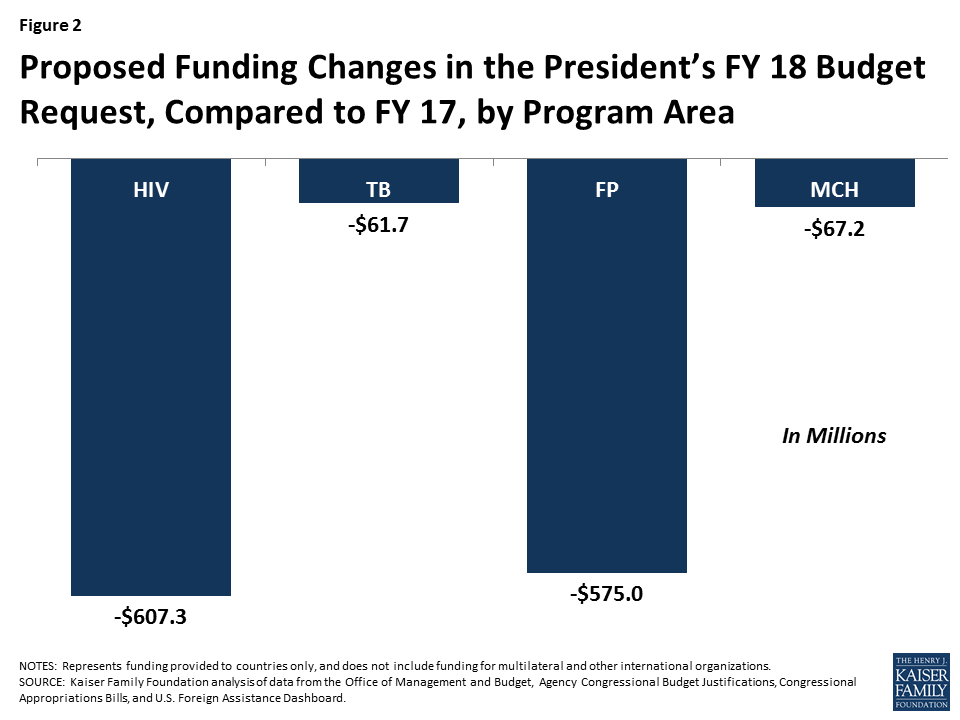

President Trump’s FY 18 budget request to Congress includes significant cuts to global health. If enacted, these cuts would total approximately $2.5 billion compared to FY 17 (a 23% reduction), and bring funding below FY 2008 levels (see Figure 1). For some global health program areas, the cuts are particularly steep. For example, PEPFAR funding to countries is cut by more than $600 million in the request and all $575 million for bilateral family planning1 is eliminated (see Figure 2). Still, the President’s budget is just the first step in a longer process where Congress now takes center stage and already, many members of Congress have indicated that they do not support cuts of this magnitude.2 At the same time, the proposed cuts – which represent the Administration’s statement of its policy priorities and set the initial framework for budget discussions in the coming year – in an already difficult budget environment suggest that the road ahead may be difficult for U.S. global health programs and the people they serve.

As Congress begins considering the request, it is important to understand how different budget choices could affect the health of those served by U.S. efforts. To do so, we developed “budget impact models” to examine the relationship between funding levels in U.S.-supported countries and health outcomes. We looked at four program areas of U.S. support – HIV, TB, family planning, and maternal, newborn, and child health. For each, we ran three budget scenarios, including the Administration’s proposed cuts as well as two more modest decreases (see Tables 1-4). We include only bilateral funding provided to countries; funding for multilateral and other international organizations was not included in our assessment. To the extent that support for these organizations is also cut (as proposed for several in the budget request), this approach would understate the impact.

Results

Our models show that any cuts to global health funding by the U.S. will affect health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, though they range significantly by budget scenario. (see Tables 1-4). For example, depending on the size of the cut, our models estimates that starting next year:

- Additional new HIV infections would range from approximately 49,100 to 198,700; similarly, additional HIV deaths would range from 22,300 to 90,500, and the number of people on antiretrovirals could decline by more than 830,000 in the steepest budget cut scenario.

- Additional new TB cases would range from 7,600 to 31,100 and TB deaths would range from 1,700 to 6,800;

- Decreases in the number of women and couples receiving contraceptives would range from approximately 6.2 million to almost 24 million; the increase in the number of abortions (most of which are unsafe 3 ) would range between 778,000 to almost 3 million; and

- Additional maternal, newborn, and child deaths would range between 7,000 and 31,300.

These estimates are based on one-year budget cuts only; if funding levels remain at the new, reduced level in the subsequent year, the cumulative impact would be doubled.

It is important to note that, while based on the latest available data, these models are intended to be illustrative only. They rely on certain assumptions that may or may not bear out in reality. For example, they assume that a change in U.S. funding will not result in a change in funding decisions made by other donors or host governments. In addition, they assume that any change in funding in a given program area is distributed proportionally, according to current spending allocations by country and type of intervention. Still, they provide one way to gauge the magnitude and direction of different budget choices. While the fate of this year’s global health budget remains uncertain, these models illustrate the relationship between such decisions and the health of those in low- and middle-income countries and provide one important tool for assessing future budget choices.

| TABLE 1: BUDGET IMPACT: PEPFAR HIV | |||

| Funding Change Scenarios FY17-18 | |||

| Scenario 1:$150Million cut | Scenario 2:$300Million cut | Scenario 3:$607.3Million cut(Administration Proposal) | |

| HIV Infections | +49,100 | +98,200 | +198,700 |

| HIV-Related Deaths | +22,300 | +44,700 | +90,500 |

| People on ARVs | -207,000 | -414,000 | -838,000 |

| NOTES: All figures are rounded. Scenario 3 (the Administration’s proposal) is based on analysis of bilateral funding provided to countries only, and includes funding provided through the Global Health Programs account at State and USAID; funding provided to CDC, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, IAVI, microbicides, UNAIDS, and for technical assistance and oversight, was not included.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. | |||

| TABLE 2: BUDGET IMPACT: TB | |||

| Funding Change Scenarios FY17-18 | |||

| Scenario 1:$15Million cut | Scenario 2:$30Million cut | Scenario 3:$61.7Million cut(Administration Proposal) | |

| TB Cases | +7,600 | +15,100 | +31,100 |

| TB-Related Deaths | +1,700 | +3,300 | +6,800 |

| NOTES: All figures are rounded. Scenario 3 (the Administration’s proposal) is based on analysis of bilateral funding provided to countries only, and includes funding provided through the Global Health Programs and ESF accounts at USAID (ESF funding was estimated for FY17); funding provided to CDC, the TB Drug Facility and for MDR Financing was not included.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. | |||

| TABLE 3: BUDGET IMPACT: FAMILY PLANNING | |||

| Funding Change Scenarios FY17-18 | |||

| Scenario 1:$150Million cut | Scenario 2:$300Million cut | Scenario 3:$575Million cut(Administration Proposal) | |

| Couples/Women Receiving Contraception | -6,218,200 | -12,436,500 | -23,836,600 |

| Unintended Pregnancies | +1,847,700 | +3,695,300 | +7,082,700 |

| Abortions | +777,500 | +1,555,100 | +2,980,500 |

| Maternal Deaths | +3,700 | +7,400 | +14,200 |

| NOTES: All figures are rounded. Scenario 3 (the Administration’s proposal) is based on analysis of bilateral funding provided to countries only, and includes funding provided through the Global Health Programs and ESF accounts at USAID.SOURCE: Guttmacher Institute, Just the Numbers: The Impact of U.S. International Family Planning Assistance, July 2017; Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. | |||

| TABLE 4: BUDGET IMPACT: MATERNAL, NEWBORN, & CHILD HEALTH | |||

| Funding Change Scenarios FY17-18 | |||

| Scenario 1:$15Million cut | Scenario 2:$30Million cut | Scenario 3:$67.2Million cut(Administration Proposal) | |

| Maternal/Newborn/Child Deaths | +7,000 | +14,000 | +31,300 |

| NOTES: All figures are rounded. Scenario 3 (the Administration’s proposal) is based on analysis of bilateral funding provided to countries only, and includes funding provided through the Global Health Programs and ESF accounts at USAID (ESF funding was estimated for FY17); funding provided to GAVI and the Global Development Lab was not included.SOURCE: Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. | |||

Appendix

Methods Appendix

Below are methodological details for each budget impact model. Our approach was similar across program areas: we identified estimated cost and health impacts of interventions and linked changes in funding to health outcomes. For each area, we examined changes in U.S. bilateral funding proposed in the FY 18 budget request compared to FY 17 levels in countries that receive U.S. support. We assume that the effect of a loss of funding is equal to the effect of a similar gain in funding. We excluded funding provided to multilateral and other international organizations and, where identifiable, funding provided for administrative/headquarters purposes. By excluding the former, we are likely to under- (in the case of cuts) or over- (in the case of increases) estimate health impacts. It is important to note that the models do not consider interactions between program areas, which could have multiplier effects. For example, decreases in PEPFAR funding could lead to fewer HIV positive pregnant women receiving services to prevent mother-to-child transmission, which in turn would lead to additional new child infections and child deaths.

HIV Budget Impact Model

The HIV budget impact model was developed with Avenir Health and uses data from Stover J, Bollinger L, Izazola JA, Loures L, DeLay P, Ghys PD, “What is Required to End the AIDS Epidemic as a Public Health Threat by 2030? The Cost and Impact of the Fast-Track Approach” (2016) PLoS ONE 11(5):e0154893 (available at http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0154893). Stover et al. model the impact of scaling up the global response to HIV, using the Spectrum Goals and Resource Needs models (for further details, see original article and http://www.avenirhealth.org/software-spectrum.php). They compare the cost of scaling up HIV interventions in low-and middle-income countries over a five-year period (2015-2020) to a constant level of coverage to determine the incremental cost of scaling up. They also compare the impact of scaling up on new HIV infections, deaths, and number on antiretrovirals (ARTs) to constant coverage levels. The impacts over the 5-year period are used to determine average annual impacts. Data inputs for each country were drawn from national surveys and national progress reports and adjusted to match the prevalence trends from national estimates. Country-specific coverage rates were used. When country-specific data were not available, regional averages were used. Costs were estimated by intervention and year, country, and intervention (see article for additional detail).

For purposes of the HIV budget impact model, only data from the 31 countries that received funding from PEPFAR in FY 2016 and are required to submit a Country Operational Plan (COP)4 were used to assess an estimated cost per infection averted, cost per death averted, and cost per person on ART in PEPFAR countries. Each of these unit costs was used to assess how changes in funding would affect outcomes. It is important to note that the cost data used for PEPFAR countries represent average total costs per intervention, not USG-specific costs. In some cases, PEPFAR may only be supporting one component of an intervention (e.g., ARV drugs) but the total cost per patient (drugs, tests, personnel) is used. However, since PEPFAR is the largest source of funding in most of these countries, this assumption does not significantly distort the impact estimate; additionally, it is likely that in many cases, without the PEPFAR component, the full service would not be provided. The model also assumes that any funding change is distributed proportionately according to the current allocation of funding by service and by country. Finally, the health impacts modeled in PEPFAR countries represent estimated outcomes based on a one-year funding change (e.g., additional deaths that would not have occurred if there had been no cut), although some of these outcomes may take longer than one year to occur. If funding levels remain at the new reduced level in the subsequent year, the cumulative impact compared to the baseline level would be doubled.

TB Budget Impact Model

The TB budget impact model was developed with Avenir Health and uses data from The Global Plan to End TB 2016–2020 (available at: http://www.stoptb.org/global/plan/plan2/). The Global Plan models the impact of scaling up the global response to the TB epidemic, based on the SPECTRUM TB Impact Model and Estimates (TIME) model (for further details, see Global Plan appendix and http://www.avenirhealth.org/software-spectrum.php). The Global Plan compares the cost of scaling up TB interventions over a five-year period (2016-2020) to a constant level of coverage to determine the incremental cost of scaling up. It also compares the impact of scaling up on new TB cases and new TB deaths to constant coverage levels. Data inputs from India, China and 7 other countries, representing 7 different TB contexts, were used to model the impact of the Global Plan. The results were then extrapolated to produce estimates for 154 countries in total, representing most of the global TB burden.

For purposes of the TB budget impact model, only data from the 22 countries that received funding from the USAID TB program in FY 2016 are used, resulting in an estimated cost per TB case averted and cost per TB death averted in USAID TB countries. It is important to note that the cost data used for these countries represent average total costs per intervention, not USG-specific costs. In some cases, USAID may only be supporting one component of an intervention but the total cost per patient is used. Where USG support is critical to the provision of the entire service, this approach would not significantly distort the impact estimate. Where USG support does not affect the overall provision of a service, this approach could overestimate the impact. The model also assumes that any funding change is distributed proportionately according to the current allocation of funding by service and country. Finally, the health impacts modeled in TB countries represent estimated outcomes based on a one-year funding change (e.g., additional deaths that would not have occurred if there had been no cut), although some of these outcomes may take longer than one year to occur. If funding levels remain at the new reduced level in the subsequent year, the cumulative impact compared to the baseline level would be doubled.

Family Planning Budget Impact Model

Family planning budget impacts are based on unrounded estimates provided by the Guttmacher Institute from their analysis in Just the Numbers: The Impact of U.S. International Family Planning Assistance, July 2017. They estimated country-level costs (direct and indirect) per use of modern contraceptive methods and impacts of changes in levels of use on unintended pregnancies, abortions, and maternal deaths. These were applied to country-level funding provided by the U.S. family planning program in FY16 to estimate the number of women/couples receiving contraceptive services and supplies from USG funding, and the subsequent impacts on unintended pregnancies, induced abortions, and maternal deaths. It is important to note that the cost data used for these countries represent average total costs, not USG-specific costs. Where USG support is critical to the provision of the entire service, this approach would not significantly distort the impact estimate. Where USG support does not affect the overall provision of a service, this approach could overestimate the impact.

Maternal and Child Health Budget Impact Model

The Maternal and Child health budget impact model was developed with Avenir Health and in consultation with researchers at Johns Hopkins University. A review of the literature* was used to obtain estimates of the cost per maternal, neonatal, or child life saved in low- and middle- income countries based on multi-country analyses. A median cost estimate across these studies was used. The change in funding provided by USAID for maternal and child health programs in countries was used to estimate the additional maternal, neonatal, or child death in these countries. It is important to note that the cost data used for these countries represent average total costs, not USG-specific costs. In addition, it was not possible to separate out the effects of funding changes on neonatal, child, and maternal deaths, given their intersectional nature. However, it is expected that most of the effect would be on child (under five) mortality.

*Bhutta Z et al., “Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost?” Lancet 2014, 384: 347–70; Darmstadt et al., “Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save?”, Lancet 2005, 365: 977–88; Bartlett et al., “The Impact and Cost of Scaling up Midwifery and Obstetrics in 58 Low- and Middle-Income Countries”, PLoS ONE 2014, 9(6): e98550; Murray C, Chambers R, “Keeping score: fostering accountability for children’s lives”, Lancet 2015, Vol 386: 3-5.

Endnotes

- “Family Planning” is used here to describe the USAID Family Planning and Reproductive Health Program. ↩︎

- See, for example: Rogin J, “Trump’s national security team could make a comeback”, Washington Post, June 11, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/trumps-national-security-team-could-make-a-comeback/2017/06/11/57564c50-4d43-11e7-9669-250d0b15f83b_story.html?utm_term=.2d92472715ed; Rogin J, “Lindsey Graham: Trump’s State Department budget could cause ‘a lot of Benghazis’” Washington Post, May 23, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/josh-rogin/wp/2017/05/23/lindsey-graham-trumps-state-department-budget-could-cause-a-lot-of-benghazis/?utm_term=.4d672739a095; Tritten T, “43 senators rally against Trump’s foreign aid cuts”, Washington Examiner, April 27, 2017, http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/43-senators-rally-against-trumps-foreign-aid-cuts/article/2621494. ↩︎

- Guttmacher Institute, Just the Numbers: The Impact of U.S. International Family Planning Assistance, May 2016. ↩︎

- Any country that receives $5 million or more in annual PEPFAR funding prepares a COP. See: US Department of State, PEPFAR Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) 2017 Guidance, January 2017. ↩︎