Implications of the ACA Medicaid Expansion: A Look at the Data and Evidence

Issue Brief

More than four years after the implementation of the Medicaid expansion included in the Affordable Care Act, debate and controversy around the implications of the expansion continue. Despite a large body of research that shows that the Medicaid expansion results in gains in coverage, improvements in access and financial security, and economic benefits for states and providers, some argue that the Medicaid expansion has broadened the program beyond its original intent diverting spending from the “truly needy”, offers poor quality and limited access to providers, and has increased state costs. New proposals allow states to implement policies never approved before including conditioning Medicaid eligibility on work or community engagement. New complex requirements run counter to the post-ACA movement of Medicaid integration with other health programs and streamlined enrollment processes. This brief examines evidence of the effects of the Medicaid expansion and some changes being implemented through waivers. Many of the findings on the effects of expansion cited in this brief are drawn from the 202 studies included in our comprehensive literature review that includes additional citations on coverage, access, and economic effects of the Medicaid expansion. Key findings include the following:

- Coverage: Research and data show that Medicaid expansion has resulted in coverage gains without diverting coverage from traditional groups; for example, data do not support a relationship between states’ expansion status and community-based services waiver waiting lists. Reductions in Medicaid coverage would result in an increase in the uninsured population.

- Access, Affordability, and Health Outcomes: Research demonstrates that Medicaid generally, and expansion specifically, positively affects access to care, utilization of services, the affordability of care, and financial security among the low-income population. While there is a growing body of evidence on Medicaid and outcomes, further research is needed to more fully determine the health effect of expansion on outcomes given that measureable changes take time to occur.

- Economic Effects: Analyses find positive economic effects of expansion largely tied to the infusion of federal dollars, despite Medicaid enrollment growth initially exceeding projections in many states. Some studies look at 2014-2016 when expansion costs were 100% financed by the federal government, others studies project net fiscal gains even after states start to pay a share of expansion costs (up to 10% by 2020). Studies also show that Medicaid expansion resulted in reductions in uninsured visits and uncompensated care costs for hospitals, clinics, and other providers.

- Expansion and Work: Studies find that Medicaid expansion has had positive or neutral effects on employment and the labor market and new work requirement proposals add complexity and could result in coverage losses for many who are working or face barriers to work.

Coverage

Research and data show that Medicaid expansion has resulted in coverage gains without diverting coverage from traditional groups.

Coverage changes: Studies show that Medicaid expansion states experienced significant coverage gains and reductions in uninsured rates compared to non-expansion states for the low-income population broadly (Figure 1).1 ,2 ,3 Under the original 1965 Medicaid law, Medicaid eligibility was tied to cash assistance, but over time, Congress has expanded federal minimum requirements and provided broader coverage options for states especially for children, pregnant women, and people with disabilities. The Medicaid expansion in the ACA built on earlier efforts to extend Medicaid coverage to low-income uninsured adults, many of whom are working but lack access to employer or other affordable health coverage. Studies also show that Medicaid expansion has resulted in coverage gains in a number of vulnerable populations, increased coverage for children as parents have gained coverage, and disproportionately positive coverage impacts in rural areas in expansion states.4 ,5 ,6 ,7 ,8 Coverage benefits of expansion have occurred across the major racial/ethnic categories.9 ,10

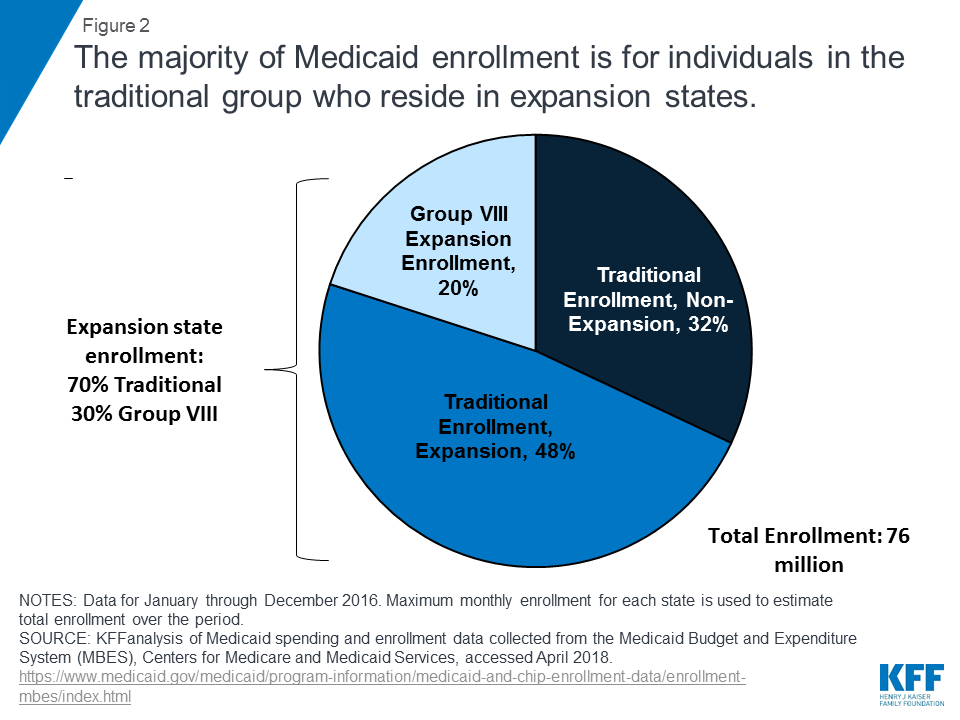

Distribution of Medicaid enrollees: The latest administrative data available show that there were 76 million Medicaid enrollees in 2016, with 15 million (20%) expansion (Group VIII) enrollees (including 12 million newly eligible enrollees). While expansion enrollment has increased since implementation of the ACA, the large majority (80%) of enrollees are in traditional (non-expansion population) enrollment categories. Expansion states account for 52 million Medicaid enrollees (68% of nationwide enrollment), and 70% of enrollees in expansion states are in traditional groups. The largest share of enrollees overall and in expansion states are traditional Medicaid enrollees that include children, low-income parents, elderly and people with disabilities (Figure 2).

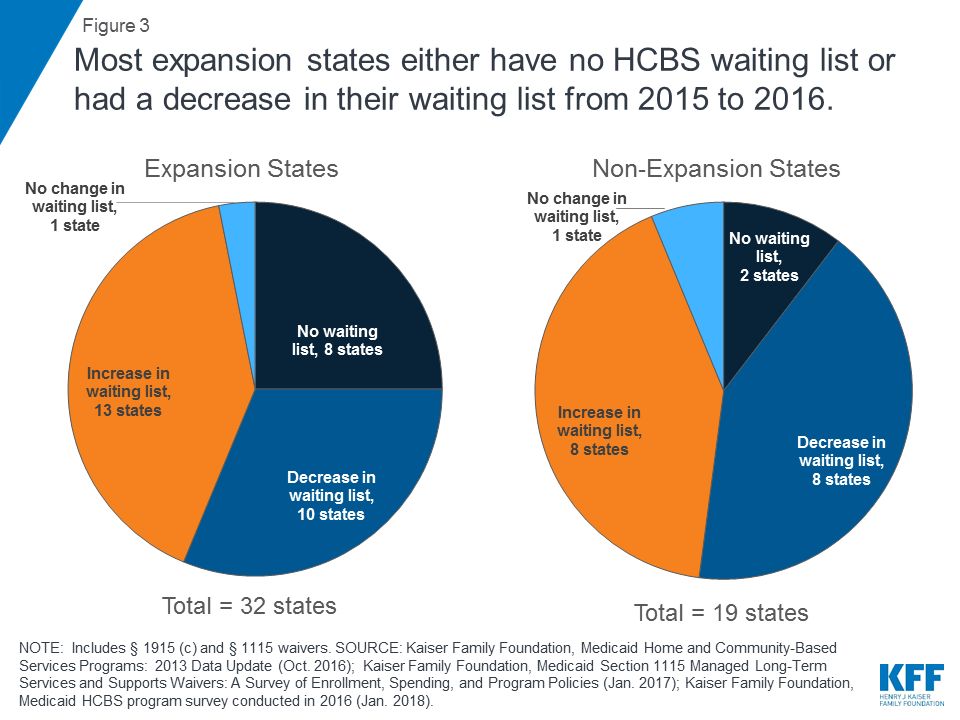

HCBS waiting lists: Nearly all home- and community-based services (HCBS) for long-term care are provided at state option, and all states offer at least one HCBS waiver for seniors and people with disabilities today. States choose how many people to serve under these waivers, and their ability to limit enrollment has resulted in waiting lists when the number of people seeking services exceeds the number of waiver slots. Such waiting lists predate the ACA Medicaid expansion. While some argue that state choices about whether to adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion come at the expense of providing Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS), data do not support a relationship between states’ expansion status and community-based services waiver waiting lists. Among the 21 states that experienced an HCBS waiver waiting list increase from 2015 to 2016, the average increase was lower in expansion states compared to non-expansion states and most expansion states either had no HCBS waiver waiting list or had a decrease in their waiting list from 2015 to 2016 (Figure 3). In addition, the Medicaid expansion has enabled some people who were not previously eligible for coverage to access needed HCBS, such as home health or personal care state plan services.11

Access, affordability, and health outcomes

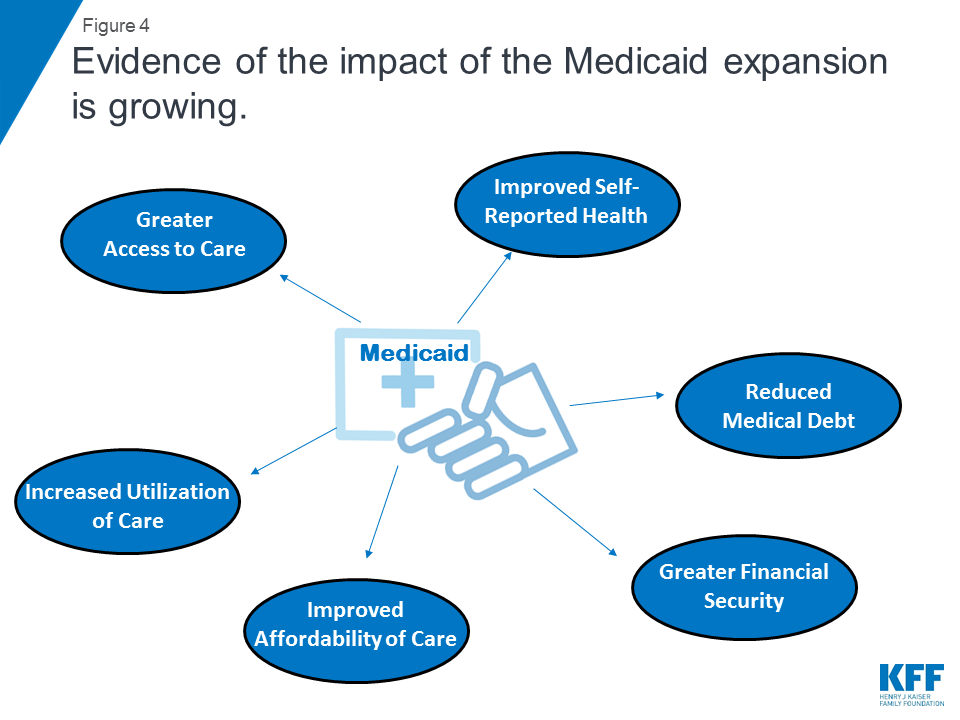

Research demonstrates that Medicaid expansion has positively affected access to care, utilization of services, the affordability of care, financial security, self-reported health, and certain measures of health outcomes among the low-income population (Figure 4). However, further research is needed to more fully determine effect of expansion on health outcomes given that measureable changes take time to occur.

Access: A large body of research points to expansion-related improvements across a wide range of measures of access to care and utilization of medications and services. For example, studies find that Medicaid expansion was associated with increases in cancer diagnosis rates (especially early-stage diagnosis rates), improvements in access to medications and services for the treatment of behavioral and mental health conditions, increases in the number of adults receiving consistent care for a chronic condition, and improvements in surgical care.12 ,13 ,14 ,15 ,16 Findings on expansion’s effect on provider capacity are mixed, with some studies suggesting that provider shortages are a challenge in certain contexts and others suggesting that providers have expanded capacity and are meeting increased demands for care.17 ,18 ,19

Affordability: Research examining expansion enrollees or low-income populations more broadly suggests that Medicaid expansion results in significant reductions in out-of-pocket medical spending, unmet medical need due to cost, and trouble paying as well as worry about paying future medical bills.20 ,21 ,22 Medicaid expansion has significantly reduced the percentage of people with medical debt, reduced the average size of medical debt, reduced the average number of collections, improved credit scores, reduced the probability of having one or more medical bills go to collections in the past six months, and reduced the probability of a new bankruptcy filing, among other improvements in measures of financial security.23 ,24 ,25 For example, a study of Ohio’s Medicaid expansion found that the percentage of expansion enrollees with medical debt fell by nearly half since enrolling in Medicaid (55.8% had debt prior to enrollment, 30.8% had debt at the time of the study).26

Health outcomes: More broadly, the purpose of health insurance is to facilitate access to care and provide protection against high out-of-pocket costs. Direct evidence that Medicaid or any other type of health coverage improves not just access to care, but ultimately health outcomes, is limited. Research has documented that Medicaid coverage of pregnant women and children contributed to dramatic declines in infant and child mortality in the United States.27 A growing number of studies show that Medicaid eligibility during childhood also has long-term positive impacts, including reduced teen mortality, reduced disability, improved long-run educational attainment, and lower rates of emergency department visits and hospitalization in later life.28 In addition, Medicaid eligibility during childhood appears to yield downstream benefits to the economy, in the form of reduced earned income tax credit payments and increased tax collections due to higher earnings in adulthood.29 With regard to expansion, studies show improved self-reported health following expansion, and multiple new studies demonstrate a positive association between expansion and health outcomes (including findings of improved outcomes for cardiac surgery patients and reduced infant mortality rates (especially among African-Americans)).30 ,31 ,32 ,33 Further research is needed to more fully determine expansion’s effects on outcomes given that it may take additional time for measureable changes in health outcomes occur over a longer time horizon.

Economic measures

Analyses find positive effects of expansion on numerous economic outcomes, despite Medicaid enrollment growth initially exceeding projections in many states and Medicaid growing faster than other programs in state budgets (Figure 5). Studies show that Medicaid expansions result in reductions in uncompensated care costs for hospitals, clinics, and other providers.

State budget effects: Data supports a net fiscal benefit for states from Medicaid expansion. National research found that there were no significant increases in spending from state funds as a result of Medicaid expansion and no significant reductions in state spending on education, transportation, or other state programs as a result of expansion during FYs 2010-2015.34 Multiple studies suggest that Medicaid expansion can result in state savings by offsetting state costs in other areas, including state costs related to behavioral health services, crime and the criminal justice system, and the Supplemental Security Income program.35 ,36 ,37 ,38 ,39 New state reports from Montana and Louisiana estimate positive economic effects tied to increased federal revenue from expansion.40 ,41 Some studies look at experience to date with the expansion when costs were 100% matched by the federal government (so savings estimates could change), but other studies project net fiscal benefit even when states begin to pay for a share of the costs. For example, the Montana study anticipates net fiscal benefit due to cost savings and increased revenue that hold even after the state share of expansion costs increases to 10 percent in 2020.

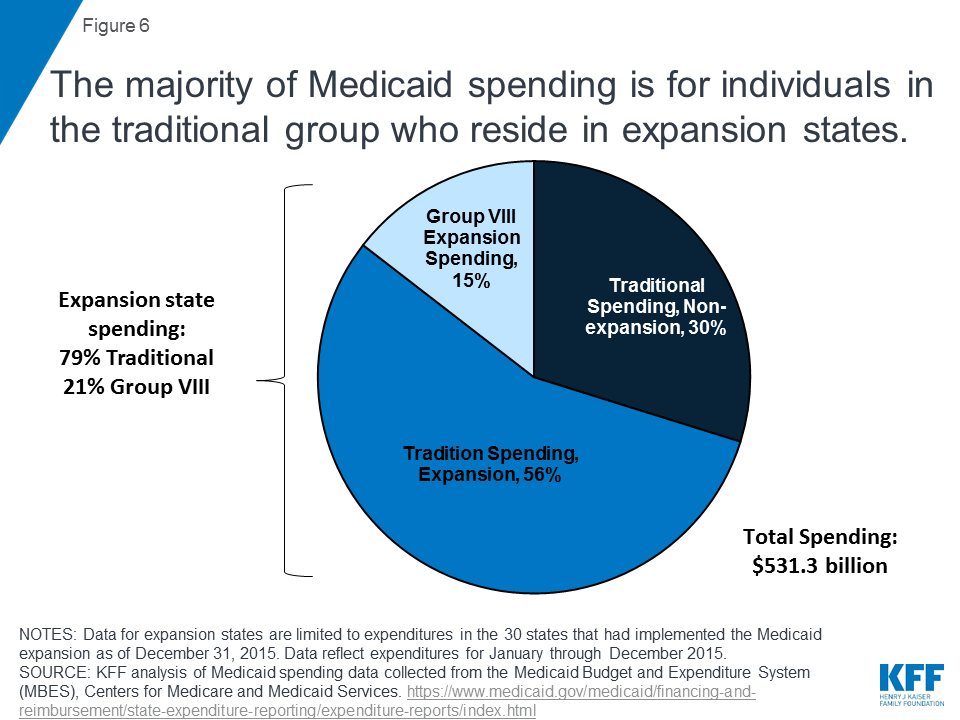

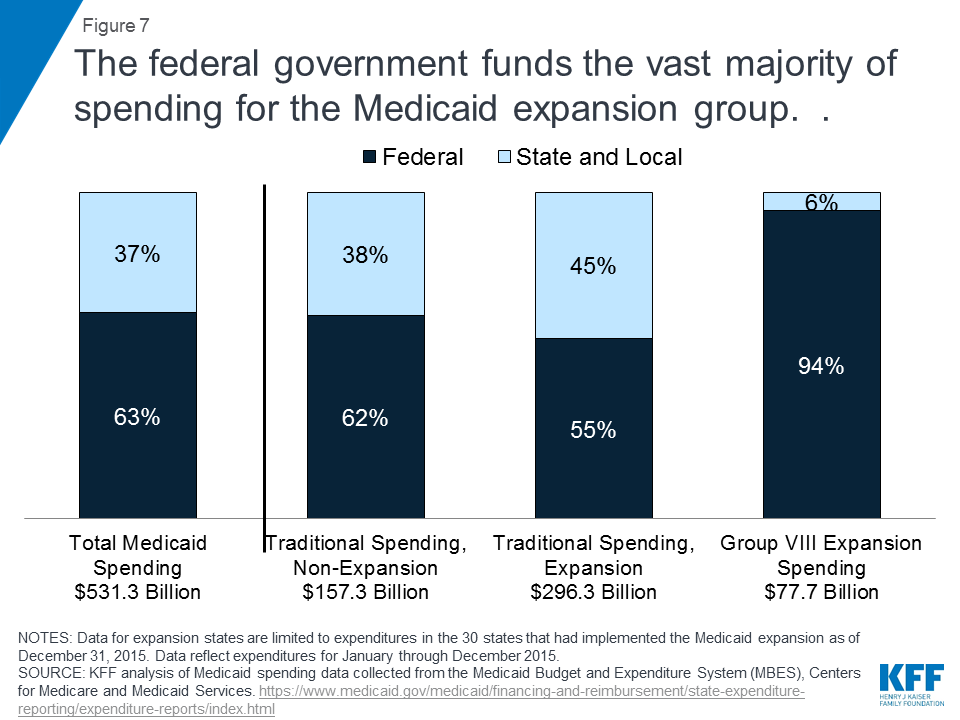

Medicaid expansion spending: In calendar year 2015, total Medicaid spending was $531 billion. Most spending (86%) was for traditional Medicaid populations and 15% ($78 billion) for the expansion group (Figure 6).42 Overall, the federal share of Medicaid spending in 2015was 63%, but the federal government pays the vast majority of spending for the expansion group.43 Under the ACA, the federal government paid 100% of the costs of those newly eligible from 2014-2016 and then the federal share gradually phases down from 95% in 2017 to 90% by 2020. Some states pay a small share of costs for individuals in the expansion group who are not newly eligible (Figure 7).

States report that that they are financing the state share of costs through general fund resources, offsetting savings in other budget areas, or dedicated provider taxes.44 In January, voters in Oregon voted on a ballot initiative to finance the state share of the Medicaid expansion through a provider tax; the vote ensured continuation of the Medicaid expansion.45 While other states use provider taxes, Oregon is the only state to put financing of the expansion to the voters.

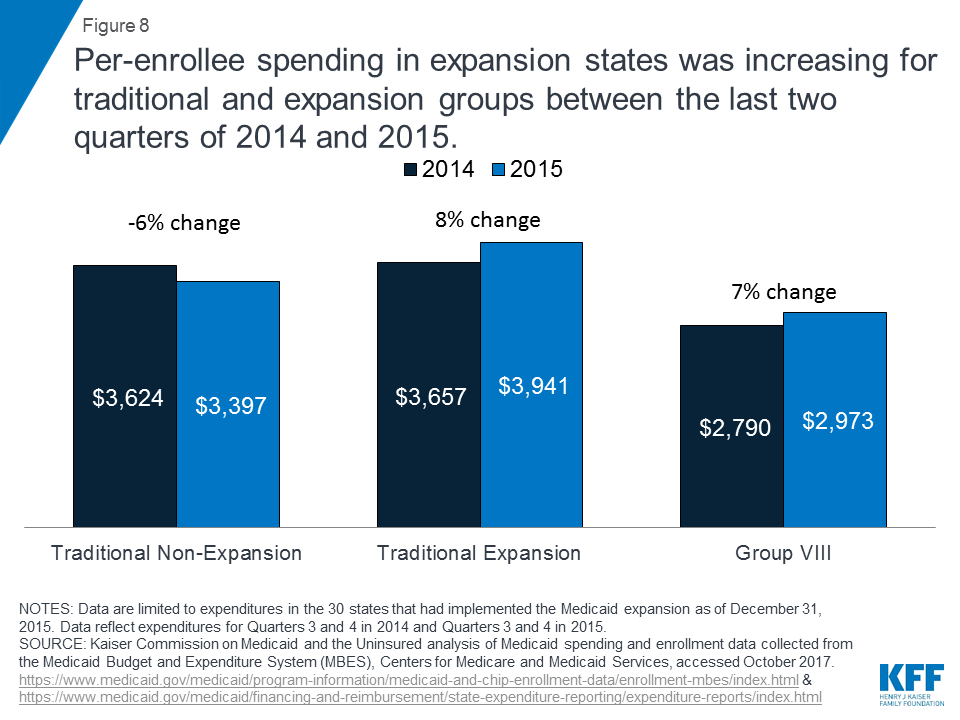

Medicaid spending per enrollee: Data also show that new coverage is not associated with diminished spending or coverage for traditional Medicaid populations. Rather, per enrollee spending increases for traditional populations in expansion states were larger than those for expansion populations or for traditional populations in non-expansion states. While per enrollee spending for expansion enrollees increased rapidly in Q1-2 2014 as the expansion ramped up, it had stabilized by Q3-4 2014. Between the last two quarters of 2015 and a similar period in 2015, per enrollee spending for Group VIII grew 7% compared to 8% for traditional enrollees in expansion states. (Figure 8).46

Providers: Studies also show that Medicaid expansions resulted in reductions in uncompensated care costs for hospitals, clinics, and other providers. The large body of literature supporting this finding includes studies pointing to declines in uninsured visits and uncompensated care (along with increases in Medicaid-covered visits) in hospitals broadly, hospital emergency departments, substance use disorder treatment facilities, community health centers, and physician offices.47 ,48 ,49 Medicaid expansion was also associated with improved hospital financial performance and significant reductions in the probability of hospital closure, especially in rural areas and areas with higher pre-ACA uninsured rates.50

Work

Studies find that Medicaid expansion can promote work and employment and has had positive or neutral effects on the labor market; however, new work requirements in Medicaid proposals could hamper coverage and increase complexity for many who are working or face barriers to work.

State-specific studies in Colorado, Kentucky, Michigan, Pennsylvania and most recently Montana and Louisiana have documented or predicted significant job growth resulting from expansion.51 ,52 ,53 ,54 ,55 ,56 No studies have found negative effects of expansion on employment or employee behavior. In an analysis of Medicaid expansion in Ohio, most expansion enrollees who were unemployed but looking for work reported that Medicaid enrollment made it easier to seek employment, and over half of expansion enrollees who were employed reported that Medicaid enrollment made it easier to continue working.57 Another study found an association between Medicaid expansion and increased volunteer work in expansion states.58

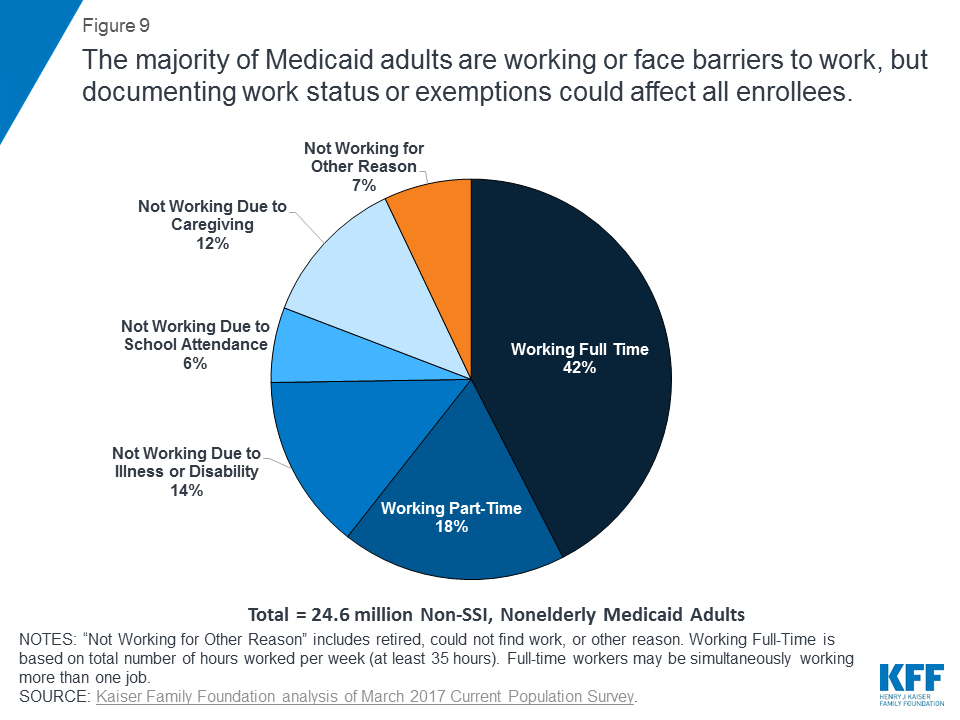

Six in ten Medicaid adults are already working. Among those who are not working, most report illness or disability, caregiving responsibilities, or going to school as reasons for not working.59 Many of these reasons would likely qualify as exemptions from work requirement policies. This would leave 7% of the population to whom work requirement policies could be directed, including those who report they are not working because they are looking for work and unable to find a job (Figure 9). However, work requirements have implications for all populations covered under these demonstrations. Those who are already working will need to successfully document and verify their compliance and those who qualify for an exemption also must successfully document and verify their exempt status, as often as monthly. States would incur costs to pay for the staff and systems to track work verification and exemptions.

While there is evidence to support an association of unemployment with poorer health status, researchers caution against using these findings to infer that the opposite relationship (employment causing improved health) exists.60 ,61 Studies on work and health have found that the quality and stability of work is a key factor in this relationship: low-quality, unstable, or poorly-paid jobs could have adverse effects on health.62 ,63 ,64 This may suggest that if there are not enough high-quality and stable employment opportunities available to the population subject to Medicaid work requirements, this population could face a difficult choice between accepting a low-wage, low-quality job option to meet the weekly/monthly hours requirement or losing access to health insurance coverage and care. As a 2006 literature review on the relationship between work, health, and well-being found, “Interventions which encourage and support claimants to come off benefits and successfully get them (back) into work are likely to improve their health and well-being; interventions which simply force claimants off benefits are more likely to harm their health and well-being.”65 In addition, studies point to negative impacts of work requirements in TANF and SNAP including modest increases in employment that faded over time; unstable employment, and disproportionate harm to people with disabilities and African Americans.66 ,67 ,68

Endnotes

- Frederic Blavin, Michael Karpman, Genevieve Kenney, and Benjamin Sommers, “Medicaid Versus Marketplace Coverage for Near-Poor Adults: Effects on Out-Of-Pocket Spending and Coverage,” Health Affairs 37 no. 2 (January 2018): 122-129 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1166 ↩︎

- Kevin Griffith, Leigh Evans, and Jacob Bor, “The Affordable Care Act Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Care Access,” Health Affairs 36 no. 8 (August 2017), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0083 ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting this finding, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Aparna Soni, Lindsay Sabik, Kosali Simon, and Benjamin Sommers, “Changes in Insurance Coverage Among Cancer Patients Under the Affordable Care Act,” Journal of the American Medical Association 4, no. 1 (January 2018): 122-124, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/article-abstract/2657670?redirect=true&redirect=true ↩︎

- Julie Hudson and Asako Moriya, “Medicaid Expansion for Adults Had Measureable ‘Welcome Mat’ Effects on Their Children,” Health Affairs, 36 no. 9 (September 2017), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347 ↩︎

- Michael Dworsky, Carrie Farmer, and Mimi Shen, Veterans’ Health Insurance Coverage Under the Affordable Care Act and Implications of Repeal for the Department of Veterans Affairs, (RAND Corporation, 2017), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1955.html ↩︎

- Jack Hoadley, Karina Wagnerman, Joan Alker, and Mark Holmes, Medicaid in Small Towns and Rural America: A Lifeline for Children, Families, and Communities (Washington, DC: Georgetown Center for Children and Families, June 2017), https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Rural-health-final.pdf ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting this finding, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Thomas Buchmueller, Zachary Levinson, Helen Levy, and Barbara Wolfe, “Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage,” American Journal of Public Health (May 2016), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27196653 ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- MaryBeth Musumeci, Data Note: Data Do Not Support Relationship Between States’ Medicaid Expansion Status and Community-Based Services Waiver Waiting Lists (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-data-do-not-support-relationship-medicaid-expansion-hcbs-waiver-waiting-lists/ ↩︎

- Aparna Soni, Kosali Simon, John Cawley, and Lindsay Sabik, “Effect of Medicaid Expansions of 2014 on Overall and Early-Stage Cancer Diagnoses,” American Journal of Public Health epub ahead of print (December 2017), http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304166 ↩︎

- United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), Medicaid Expansion: Behavioral Health Treatment Use in Selected States in 2014 (Washington, DC: GAO Report to Congressional Requesters, June 2017), https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/685415.pdf ↩︎

- Benjamin Sommers, Robert Blendon, E. John Orav, Arnold Epstein, “Changes in Utilization and Health Among Low-Income Adults After Medicaid Expansion or Expanded Private Insurance,” The Journal of the American Medical Association 176 no. 10 (October 2016): 1501-1509, http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2542420 ↩︎

- Andrew Loehrer et al., “Association of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion with Access to and Quality of Care for Surgical Conditions,” Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery, epub ahead of print (January 2018), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/article-abstract/2670459?redirect=true ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Sarah Miller and Laura Wherry, “Health and Access to Care During the First 2 Years of the ACA Medicaid Expansions,” The New England Journal of Medicine 376 no. 10 (March 2017), http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1612890 ↩︎

- Molly Candon et al., Primary Care Appointment Availability and the ACA Insurance Expansions (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, March 2017), https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/primary-care-appointment-availability-and-aca-insurance-expansions ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Frederic Blavin, Michael Karpman, Genevieve Kenney, and Benjamin Sommers, “Medicaid Versus Marketplace Coverage for Near-Poor Adults: Effects on Out-Of-Pocket Spending and Coverage,” Health Affairs 37 no. 2 (January 2018): 122-129 https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1166 ↩︎

- Kenneth Brevoort, Daniel Grodzicki, and Martin Hackmann, Medicaid and Financial Health (National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 24002, November 2017), http://www.nber.org/papers/w24002 ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Kyle Caswell and Timothy Waidmann, The Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions and Personal Finance (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, September 2017), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/affordable-care-act-medicaid-expansions-and-personal-finance ↩︎

- Luojia Hu, Robert Kaestner, Bhashkar Mazumder, Sarah Miller, and Ashley Wong, The Effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions on Financial Well-Being (Working Paper No. 22170, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2016), http://www.nber.org/papers/w22170?utm_campaign=ntw&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ntw ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- The Ohio Department of Medicaid, Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the Ohio General Assembly (The Ohio Department of Medicaid, January 2017), http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Assessment.pdf ↩︎

- Julia Paradise, Data Note: Three Findings about Access to Care and Health Outcomes in Medicaid (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-three-findings-about-access-to-care-and-health-outcomes-in-medicaid/ ↩︎

- Julia Paradise, Data Note: Three Findings about Access to Care and Health Outcomes in Medicaid (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-three-findings-about-access-to-care-and-health-outcomes-in-medicaid/ ↩︎

- Julia Paradise, Data Note: Three Findings about Access to Care and Health Outcomes in Medicaid (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/data-note-three-findings-about-access-to-care-and-health-outcomes-in-medicaid/ ↩︎

- Benjamin Sommers, Bethany Maylone, Robert Blendon, E. John Orav, and Arnold Epstein, “Three-Year Impacts of the Affordable Care Act: Improved Medical Care and Health Among Low-Income Adults,” Health Affairs epub ahead of print (May 2017), http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2017/05/15/hlthaff.2017.0293 ↩︎

- Eric Charles et al., “Impact of Medicaid Expansion on Cardiac Surgery Volume and Outcomes,” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery (June 2017), http://www.annalsthoracicsurgery.org/article/S0003-4975(17)30552-0/pdf ↩︎

- Chintan Bhatt and Consuelo Beck-Sague, “Medicaid Expansion and Infant Mortality in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health (January 2018) e1-e3, http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304218 ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Benjamin Sommers and Jonathan Gruber, “Federal Funding Insulated State Budgets From Increased Spending Related To Medicaid Expansion,” Health Affairs epub ahead of print (April 2017), http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/early/2017/04/10/hlthaff.2016.1666.full ↩︎

- April Grady, Deborah Bachrach, and Patti Boozang, Medicaid’s Role in the Delivery and Payment of Substance Use Disorder Services in Montana, (Manatt Health, March 2017), http://mthcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Medicaid-Role-in-Substance-Use-Disorder-Services-in-Montana_Final.pdf ↩︎

- Aparna Soni, Marguerite Burns, Laura Dague, and Kosali Simon, “Medicaid Expansion and State Trends in Supplemental Security Income Program Participation,” Health Affairs 36 no. 8, (August 2017): 1485-1488, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/36/8/1485.full?sid=982b20c0-0a17-4dc4-a35a-b0302d4ec289 ↩︎

- Jacob Vogler, Access to Health Care and Criminal Behavior: Short-Run Evidence from the ACA Medicaid Expansions (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, November 2017), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3042267 ↩︎

- Deborah Bachrach, Patricia Boozang, Avi Herring, and Dori Glanz Reyneri, States Expanding Medicaid See Significant Budget Savings and Revenue Gains, (Manatt Health Solutions, prepared by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s State Health Reform Assistance Network, March 2016), http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2016/rwjf419097 ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Bryce Ward and Brandon Bridge, The Economic Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Montana (Missoula, MT: University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research, April 2018), https://mthcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BBER-MT-Medicaid-Expansion-Report_4.11.18.pdf ↩︎

- James Richardson, Jared Llorens, and Roy Heidelberg, Medicaid Expansion and the Louisiana Economy (Public Administration Institute at Louisiana State University, prepared for the Louisiana Department of Health, March 2018), http://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/MedicaidExpansion/MedicaidExpansionStudy.pdf ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Medicaid spending and enrollment data collected from the Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System (MBES), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accessed October 2017. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz and Allison Valentine, Medicaid Enrollment & Spending Growth: FY 2017 and 2018, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-spending-growth-fy-2017-2018/ At least six states (including AR, AZ, CO, IN, LA, NH) reported funding all or part of the state share of Medicaid expansion costs with provider taxes as of Summer 2017. Data on financing of the state share of expansion costs were collected as part of the FY 2017 and 2018 budget survey of Medicaid officials conducted by KFF and HMA but were not published in the associated spending and enrollment growth report. ↩︎

- Ballotpedia, “Oregon Measure 101, Healthcare Insurance Premiums Tax for Medicaid Referendum,” (January 2018), https://ballotpedia.org/Oregon_Measure_101,_Healthcare_Insurance_Premiums_Tax_for_Medicaid_Referendum_(January_2018) ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Medicaid spending and enrollment data collected from the Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System (MBES), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accessed October 2017. ↩︎

- Fredric Blavin, How Has the ACA Changed Finances for Different Types of Hospitals? Updated Insights from 2015 Cost Report Data (The Urban Institute, April 2017), http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2017/rwjf436310 ↩︎

- Kurt Gillis, Physicians’ Patient Mix – A Snapshot from the 2016 Benchmark Survey and Changes Associated with the ACA (American Medical Association, October 2017), https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/health-policy/PRP-2017-physician-benchmark-survey-patient-mix.pdf ↩︎

- For additional study citations supporting these findings, see: Larisa Antonisse, Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Samantha Artiga, The Effects of Medicaid Expansion under the ACA: Updated Findings from a Literature Review (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018/ ↩︎

- Richard Lindrooth, Marcelo Perraillon, Rose Hardy, and Gregory Tung, “Understanding the Relationship Between Medicaid Expansions and Hospital Closures,” Health Affairs epub ahead of print (January 2018), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0976 ↩︎

- The Colorado Health Foundation, Assessing the Economic and Budgetary Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Colorado, (The Colorado Health Foundation, March 2016). ↩︎

- Deloitte Development LLC, Commonwealth of Kentucky Medicaid Expansion Report (February 2015). ↩︎

- John Ayanian, Gabriel Ehrlich, Donald Grimes, and Helen Levy, “Economic Effects of Medicaid Expansion in Michigan,” The New England Journal of Medicine epub ahead of print (January 2017), http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1613981 ↩︎

- Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Medicaid Expansion Report (Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, January 2017), http://www.dhs.pa.gov/cs/groups/webcontent/documents/document/c_257436.pdf ↩︎

- Bryce Ward and Brandon Bridge, The Economic Impact of Medicaid Expansion in Montana (Missoula, MT: University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research, April 2018), https://mthcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BBER-MT-Medicaid-Expansion-Report_4.11.18.pdf ↩︎

- James Richardson, Jared Llorens, and Roy Heidelberg, Medicaid Expansion and the Louisiana Economy (Public Administration Institute at Louisiana State University, prepared for the Louisiana Department of Health, March 2018), http://gov.louisiana.gov/assets/MedicaidExpansion/MedicaidExpansionStudy.pdf ↩︎

- The Ohio Department of Medicaid, Ohio Medicaid Group VIII Assessment: A Report to the Ohio General Assembly (The Ohio Department of Medicaid, January 2017), http://medicaid.ohio.gov/Portals/0/Resources/Reports/Annual/Group-VIII-Assessment.pdf ↩︎

- Heeju Sohn and Stefan Timmermans, “Social Effects of Health Care Reform: Medicaid Expansion under the Affordable Care Act and Changes in Volunteering,” Socius: Socialogical Research for a Dynamic World 3 (March 2017): 1-12, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023117700903 ↩︎

- Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Anthony Damico, Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work/ ↩︎

- Steve Crabtree, “In U.S., Depression Rates Higher for Long-Term Unemployed,” Gallup (June 2014), http://news.gallup.com/poll/171044/depression-rates-higher-among-long-term-unemployed.aspx ↩︎

- Gordon Waddell and A. Kim Burton, Is Work Good for your Health and Well-Being?, (2006). ↩︎

- Pekka Virtanen et al., “Temporary Employment and Health: A Review,” International Journal of Epidemiology 34 (2005): 610-622. ↩︎

- Pekka Virtanen, Urban Janlert, and Anne Hammarstrom, “Exposure to temporary employment and job insecurity: A Longitudinal Study of the Health Effects,” Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 68, no. 8 (August 2011): 570-574. ↩︎

- Gordon Waddell and A. Kim Burton, Is Work Good for your Health and Well-Being?, (2006). ↩︎

- Gordon Waddell and A. Kim Burton, Is Work Good for your Health and Well-Being?, (2006). ↩︎

- MaryBeth Musumeci and Julia Zur, Medicaid Enrollees and Work Requirements: Lessons from the TANF Experience (Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation, August 2017), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollees-and-work-requirements-lessons-from-the-tanf-experience/ ↩︎

- Heather Hahn et al., Work Requirements in Social Safety Net Programs (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, December 2017), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/95566/work-requirements-in-social-safety-net-programs.pdf ↩︎

- LaDonna Pavetti, Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2016), https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/work-requirements-dont-cut-poverty-evidence-shows ↩︎