The Uninsured at the Starting Line in California: California findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA

This report presents data on the population targeted for coverage expansions under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in California, and aims to help policymakers target early efforts and evaluate the ACA’s longer-term effects. The report is part of an ongoing series of comprehensive surveys nationally and in select states that will provide data on these groups’ experience with health coverage, current patterns of care, and family finances. The California report, based on the baseline 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, provides a snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults in California across the income spectrum at the starting line of ACA implementation.

Executive Summary

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect. These provisions include the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces (known in California as Covered California) where low and moderate income families can receive premium tax credits to purchase coverage and, in states that opted to expand their Medicaid (known in California as Medi-Cal) programs, the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). The ACA has the potential to reach many of the 47 million Americans who lack insurance coverage, including 7 million in California, as well as millions of insured people who face financial strain or coverage limits related to health insurance.

California was one six states that opted to expand health coverage early to low-income adults in preparation for the ACA.1 The state did so through its §1115 Bridge to Reform Medicaid waiver, which created the Low-Income Health Program (LIHP).2 LIHP reached many uninsured adults, and millions more are eligible for coverage through the Medi-Cal expansion or through Covered California.3 Though implementation is underway in California and across the country and people are already enrolling in coverage, policymakers continue to need information to inform the early stages of these coverage expansions. Data on Californians targeted for coverage expansions’ experience with health coverage, current patterns of care, and family situation can help state policymakers target early efforts and provide insight into some of the challenges that are arising in the first months of new coverage.

This report, based on findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, provides a snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured California adults across the income spectrum at the starting line of ACA implementation. The survey, conducted between July and September 2013, is a nationally representative survey that also includes a state-representative sample of over 2,500 nonelderly (age 19-64) adults in California. It was designed to focus on the low- and moderate-income populations in the state and includes over-samples of people in the income range for financial assistance under the ACA (≤ 138% FPL for Medi-Cal and 139-400% FPL for Covered California), as well as a comparison group with incomes over 400% FPL. The survey includes adults with employer coverage, nongroup, Medi-Cal, and other sources of coverage, as well as those with no health insurance. The California component of the survey and report on its findings complements a report on similar findings for the nation.4

This survey and report provides new data to help policymakers further understand early challenges in implementing health reform and assist outreach and enrollment workers, health plans, and providers and health systems. This survey also provides a baseline for future assessment of the impact of the ACA in California on health coverage, access, and financial security of low- and moderate-income individuals. Detailed information on the survey design, sample, and analysis can be found in the Methods section at the end of the full report.

Background: The Challenge of Expanding Health Coverage in California

Prior to implementation of the ACA, nearly 7 million Californians—21% of the state’s nonelderly population—were without health insurance coverage. Because publicly-financed coverage has already been expanded to most low-income children and Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly, the vast majority of uninsured people in California and across the country are nonelderly adults.5 The main barrier that people have faced in obtaining health insurance coverage is cost: health coverage is expensive, and few people can afford to buy it on their own. While most Americans traditionally obtain health insurance coverage as a fringe benefit through an employer, not all workers are offered employer coverage. Medi-Cal covers many low-income children, but eligibility for parents and adults without dependent children was limited before the ACA, leaving many adults without affordable coverage.

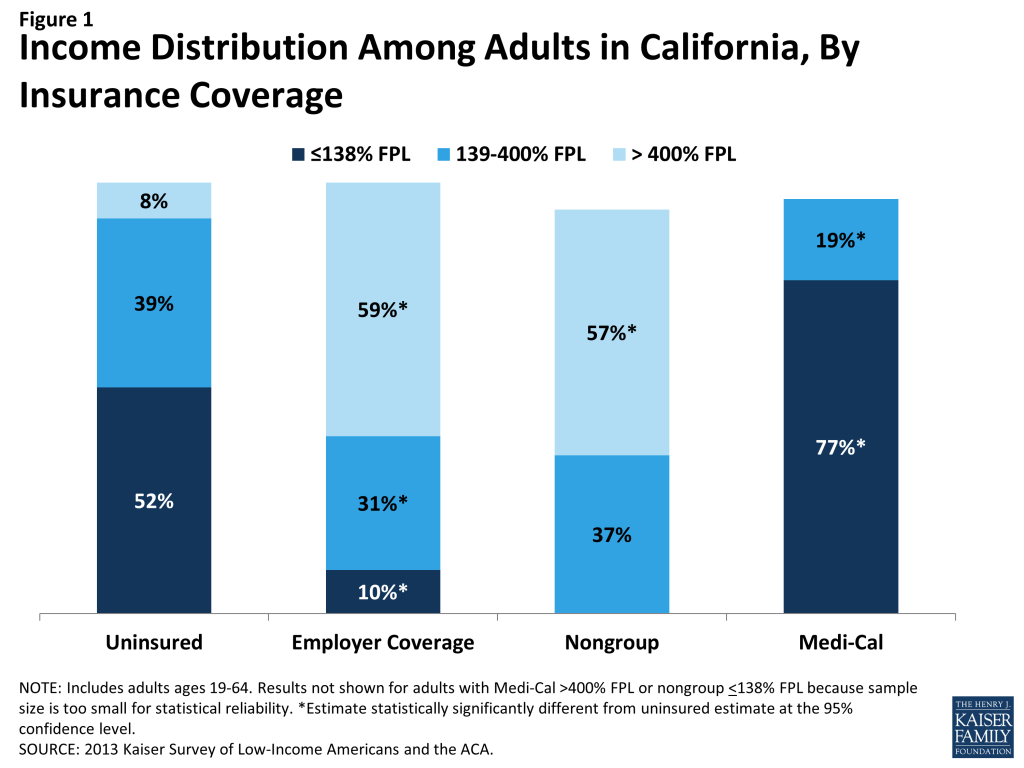

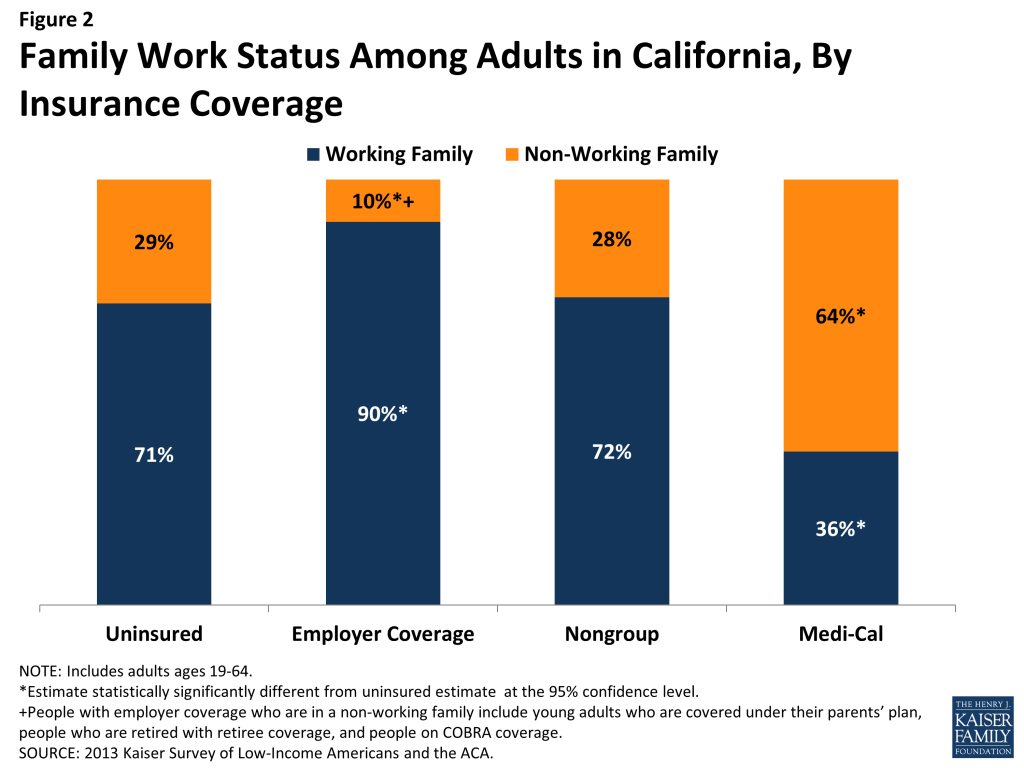

Barriers to coverage are reflected in the characteristics of the uninsured population in California. Uninsured California adults are more likely to be low-income than Californians with private health insurance (including employer coverage and nongroup coverage), while adults with Medi-Cal coverage are particularly low-income (reflecting pre-ACA eligibility limits). Though the majority of uninsured adults are in a family with either a full- or part-time worker, uninsured California adults are less likely than privately insured adults to be in families with either a full- or part-time worker. The unique demographics of the state population also play a role in shaping the profile of uninsured Californians. California is a highly-diverse state, with 60% of the state population identifying as a race other than White, and the state is home to more than 10 million immigrants. The state also has the largest number of undocumented immigrants in the nation. While these demographics characterize the entire state population, the majority of uninsured adults in California are people of color (74%), and over a third (36%) are not U.S. citizens. These demographics have implications for outreach efforts as well as eligibility, since non-citizens may face restrictions on eligibility depending on their documentation status.

I. Patterns of Coverage and the Need for Assistance

Examining patterns of coverage and the reasons the uninsured lack coverage can inform both outreach avenues and potential barriers to outreach and enrollment. Key survey findings on access to coverage include:

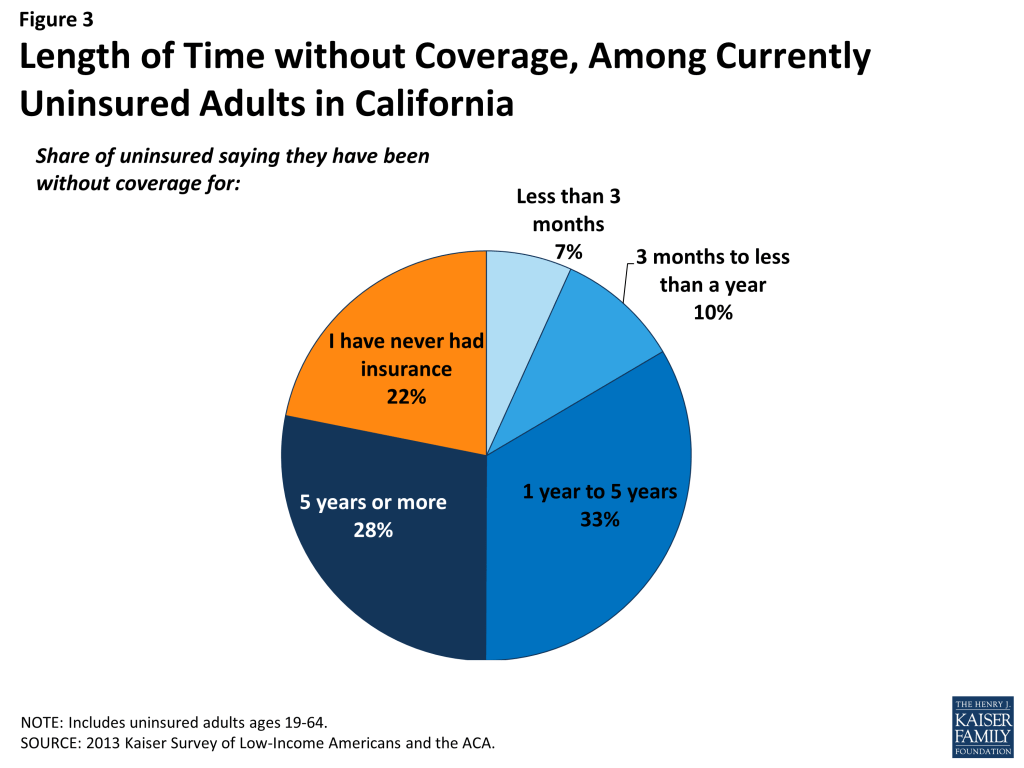

For most currently uninsured adults in California, lack of coverage is a long-term issue. While some people experience short spells of uninsurance due to job changes, income fluctuations, or renewal issues, for most uninsured California adults, lack of coverage is a chronic issue. The survey shows that half (50%) of uninsured adults report being uninsured for 5 years or more, including 22% of the uninsured who report that they have never had coverage in their lifetime.

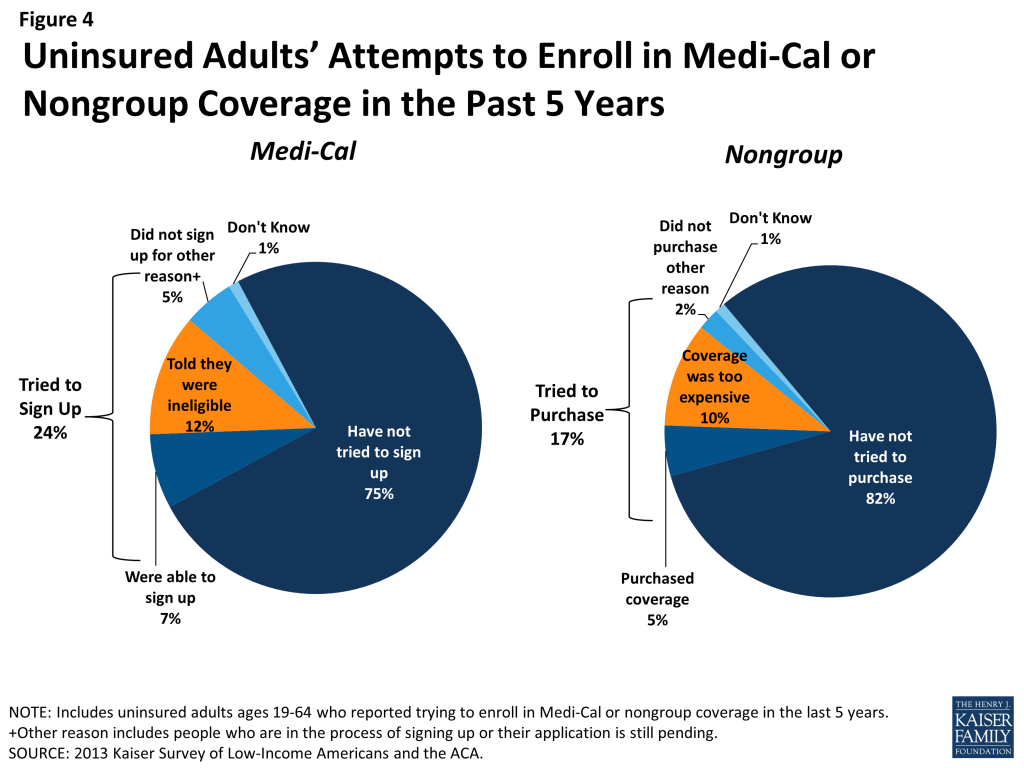

Many uninsured adults in California report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage. Prior to the ACA, California’s uninsured reported difficulty gaining insurance coverage due to the high cost of coverage and limits on Medi-Cal eligibility for adults. More than eight in ten (82%) uninsured adults report no access to employer insurance, and the majority of people who had access to coverage through an employer report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable. One-quarter of uninsured California adults (24%) reported trying to sign up for Medi-Cal in the past five years, and the majority of them were unsuccessful because they were told they were ineligible. And one in six uninsured California adults (17%) reported trying to obtain nongroup coverage in the past five years, with most not purchasing a plan because the policy they were offered was too expensive.

Health insurance coverage is not always stable. For most insured adults in California, coverage is continuous throughout the year and over time, but a sizable number have a gap or change in coverage. When accounting for both insured Californians with a gap in their coverage and uninsured Californians who recently lost coverage, the survey indicates that 8% of adults in California, or almost 2 million people, lose or gain coverage over the course of a year. In addition to those who lose or gain coverage over the course of a year, 1.4 million continuously insured adults report having a change in their health insurance plan. The most common reasons for a change in coverage appear to be related to employment. Last, a small number of insured California adults report challenges in either renewing or keeping their coverage, another indication of instability in coverage throughout the year.

Informing California’s ACA Implementation: Many of the barriers to coverage that California’s uninsured reported facing in the past are addressed by the ACA’s provisions to expand Medi-Cal and provide premium tax credits for Covered California coverage. However, some uninsured adults may continue to face financial barriers to coverage, as undocumented immigrants are excluded from receiving financial assistance under the ACA. Californians targeted by the ACA have varying levels of experience with the insurance system. A large share of uninsured adults in California has been outside the insurance system for quite some time, and the long-term uninsured may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate their new health insurance. In addition, people who have attempted to obtain coverage in the past may be unaware that rules and costs have changed under the ACA; outreach and education will be needed to inform people that eligibility rules have changed and that financial assistance is available to offset the cost of coverage.

While there has been much focus on enrolling currently uninsured people into Medi-Cal or Covered California coverage, survey findings demonstrate that people will continue to move around within the insurance system throughout the year as their income or job situations change. Thus, implementation is not a “one shot” effort that will be done once Californians are enrolled or transferred to Medi-Cal or Covered California in the early part of 2014, but rather will require a continuous effort to enroll and keep people in coverage. With this challenge in mind, California has sought federal grants and other investments for ongoing outreach, enrollment, and education efforts. However, efforts at all levels within the state will need to be sustained looking forward.

II. What to Look for in Enrolling in New Coverage

While many currently uninsured adults in California have limited experience in signing up for and using health coverage, the past successes and challenges of insured low-and moderate income adults can inform the experiences of those seeking coverage under the ACA. Key survey findings related to plan enrollment and plan choice are:

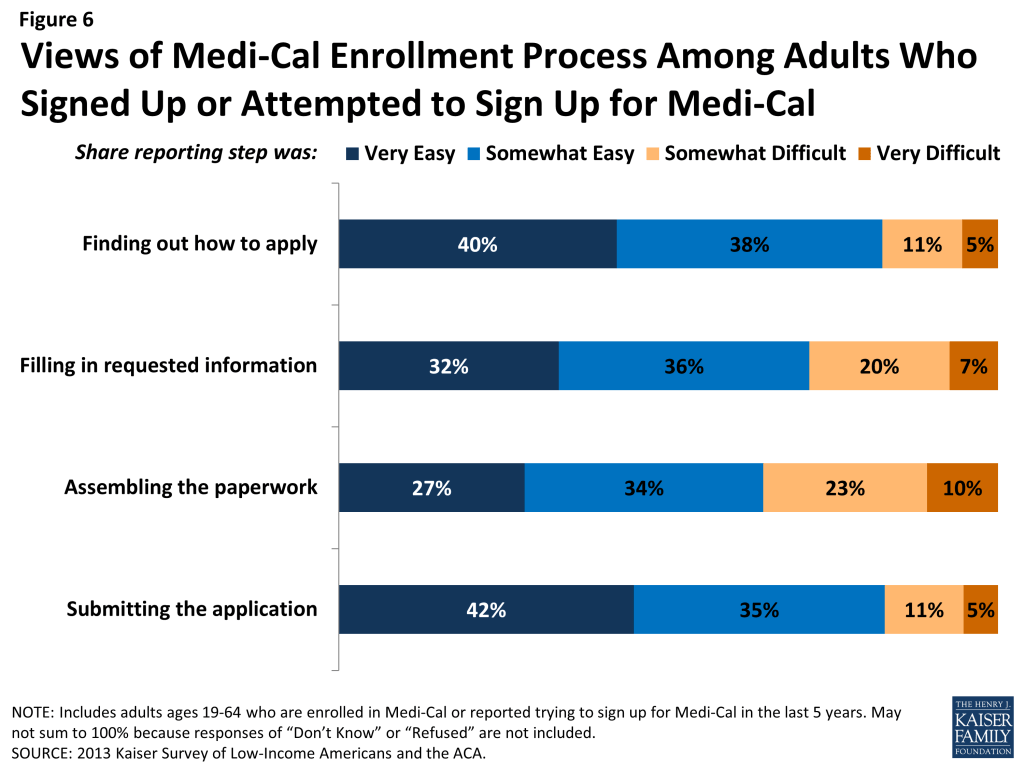

While many adults in California report facing no difficulty in applying for Medi-Cal coverage prior to the ACA, some encountered difficulties in the process of applying for public coverage in the past. California adults who currently have Medi-Cal or who have attempted to enroll in the past five years reported little difficulty in taking steps to enroll in Medi-Cal, with almost half (48%) saying the entire process was very or somewhat easy. However, the rest found at least one aspect of the process – finding out how to apply, filling out the application, assembling the required paperwork, or submitting the application – to be somewhat or very difficult. The most commonly-reported difficulty was assembling the required paperwork, which about a third of Californians who applied or enrolled said was somewhat or very difficult.

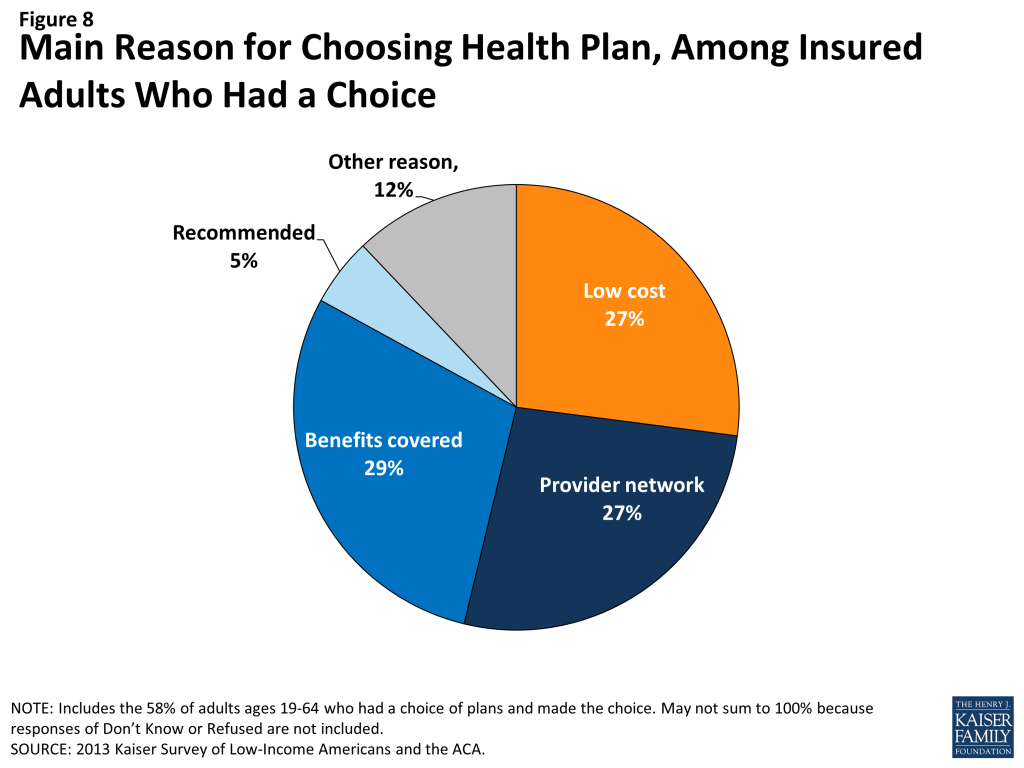

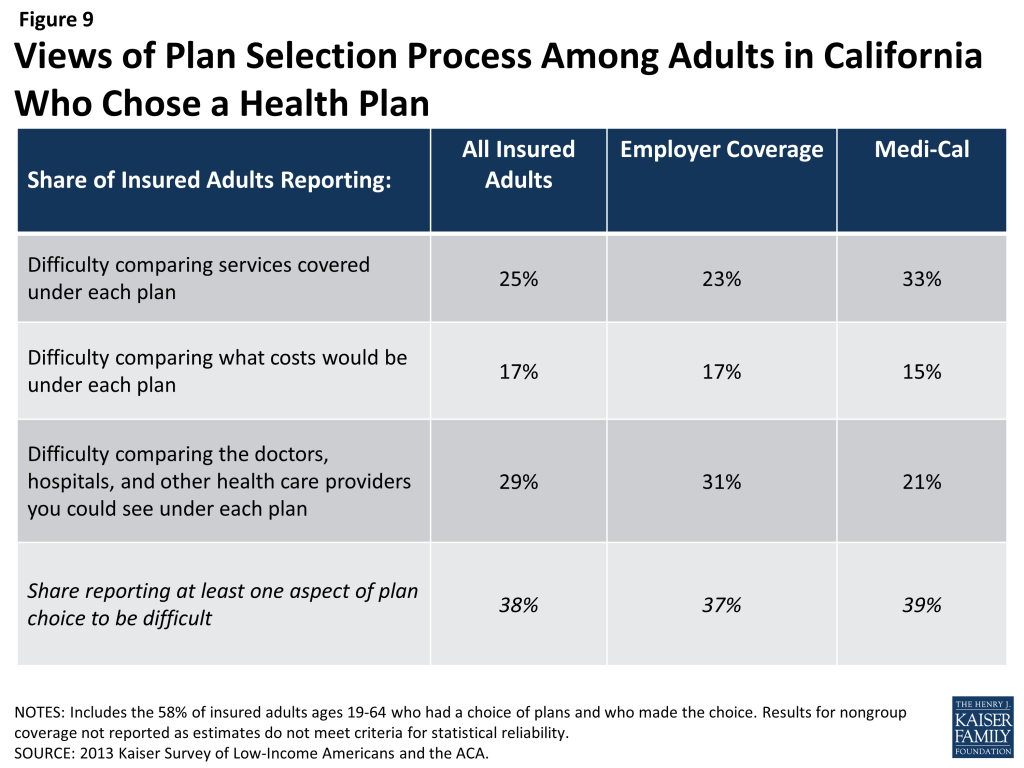

When adults with Medi-Cal or private insurance have a choice of plan, they do not always prioritize costs over other plan features in making that choice, and many find some aspect of the plan choice process to be a challenge. Adults chose health plans for various reasons, with 29% of those who had and made a choice of plan reporting that they chose their plan because it covered a wide range of benefits or a specific benefit that they need, 27% because their costs would be low, and 27% because the plan had a broad selection of providers or included their doctor. In choosing a plan, even if they have limited options, Californians may face challenges in comparing costs, services, and provider networks, as these factors have typically varied greatly across plans in the past. In general, insured adults in California report that they did not have difficulty in comparing their plan choices, but 38% found some aspect of plan choice—comparing services, comparing costs, and comparing providers— to be difficult.

Overall, adults in California with employer coverage, nongroup, or Medi-Cal report satisfaction with their current coverage but also report gaps in covered services and problems when using their coverage. Most (85%) insured adults in California rate their pre-ACA coverage as excellent or good, but they also report gaps in services that are covered by their current insurance. One in five (20%) insured adults in California report needing a service that is not covered by their current plan, typically ancillary services, such as dental, vision care, and chiropractor services. Many insured adults in California reported experiencing a problem with their current insurance plan covering a specific benefit, either because they were denied coverage for a service they thought was covered (24%) or their out-of-pocket costs for a service were higher than they expected (35%).

Informing ACA Implementation. The ACA includes provisions to simplify the Medi-Cal application and enrollment process for coverage. The ACA also requires plans in the Covered California Marketplace to provide detailed, standardized plan information for people to compare coverage options. Uninsured California adults applying for coverage after these new processes are implemented should encounter fewer challenges in navigating enrollment and plan choice than applicants have in the past. However, in evaluating the success of plan enrollment, it is important to bear in mind that, even prior to the ACA, insured adults faced some challenges in comparing and selecting insurance coverage. While provisions in the ACA could address these challenges, some are inherent to the complexity of insurance coverage. Ongoing efforts in the state are also trying to make the process of enrolling in Medi-Cal coverage a more positive and welcoming experience, which calls for a culture shift to reorient Medicaid management, systems, and caseworker training away from welfare-style “gatekeeping” and toward encouraging participation.6 It is also important to remember that people place utility on a range of factors related to insurance, including scope of services and provider networks. Assessments of whether people are choosing the optimal plan for themselves and their family will need to consider the multiple priorities that people balance in plan selection. Last, while the ACA aims to ensure coverage of at least a basic set of essential health benefits (EHB), many of the ancillary services that people report needing coverage for—such as dental services—are not included in the EHB. Newly-insured Californians may be surprised to learn that some ancillary services are not included in their plan, and education efforts will be needed to help Californians understand their coverage.

III. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

As uninsured adults in California gain coverage, there are likely to be changes in how often they seek care, what type of care they seek, and where they seek care. By comparing their current interactions with the health care system to their insured counterparts, the survey can provide insight into likely changes. Key findings in this area include:

A large segment of the uninsured in California has little or no connection to the health care system. Most uninsured adults report few connections to the health care system. Only 49% of uninsured adults report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when they are sick or need advice about their health, and only 23% of uninsured adults say they have a regular doctor, one-third of the rate of insured adults in California. This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults to go without care. Nearly five in ten uninsured adults in California (49%) reported no health care visits in the past year, compared to 15% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries and 14% of adults with employer coverage.

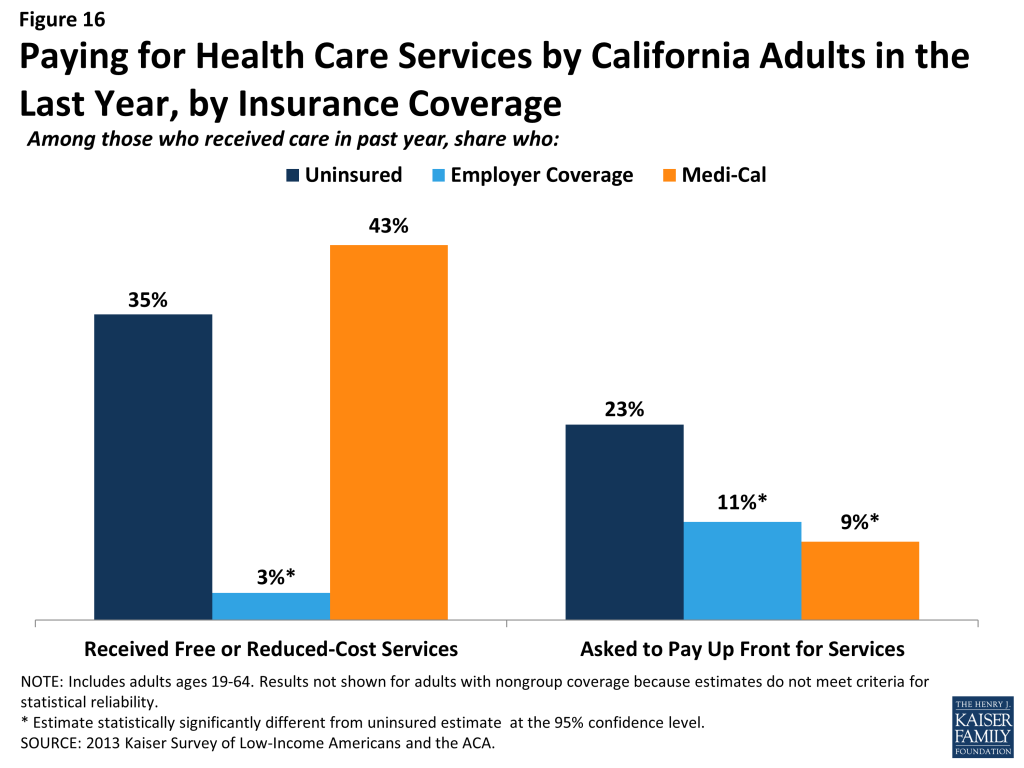

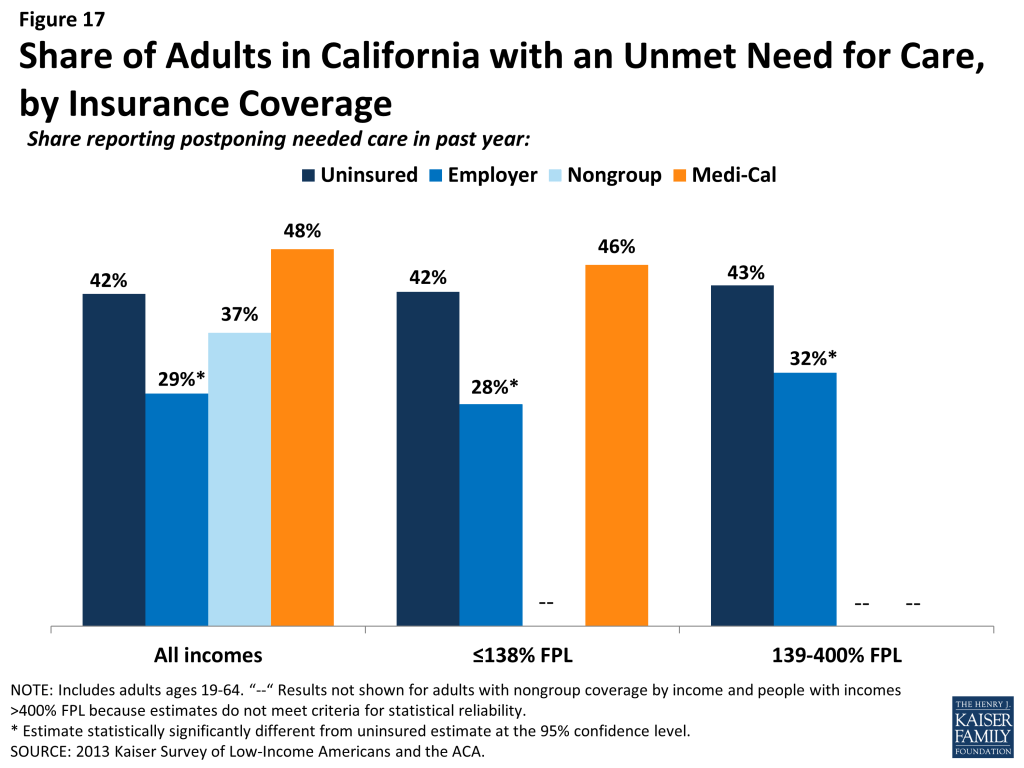

Many uninsured Californians have health needs, many of which are unmet or only met with difficulty. Uninsured adults are less likely than their insured counterparts to report receiving care for an ongoing health condition. When uninsured individuals do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority who use services do not. More than four in ten (42%) of the uninsured and almost half (48%) of Medi-Cal beneficiaries in California report needing but postponing care, compared to 29% of adults with employer coverage. The most common reason for postponing care among the uninsured is cost, as the uninsured have no coverage to help them with the cost of care.

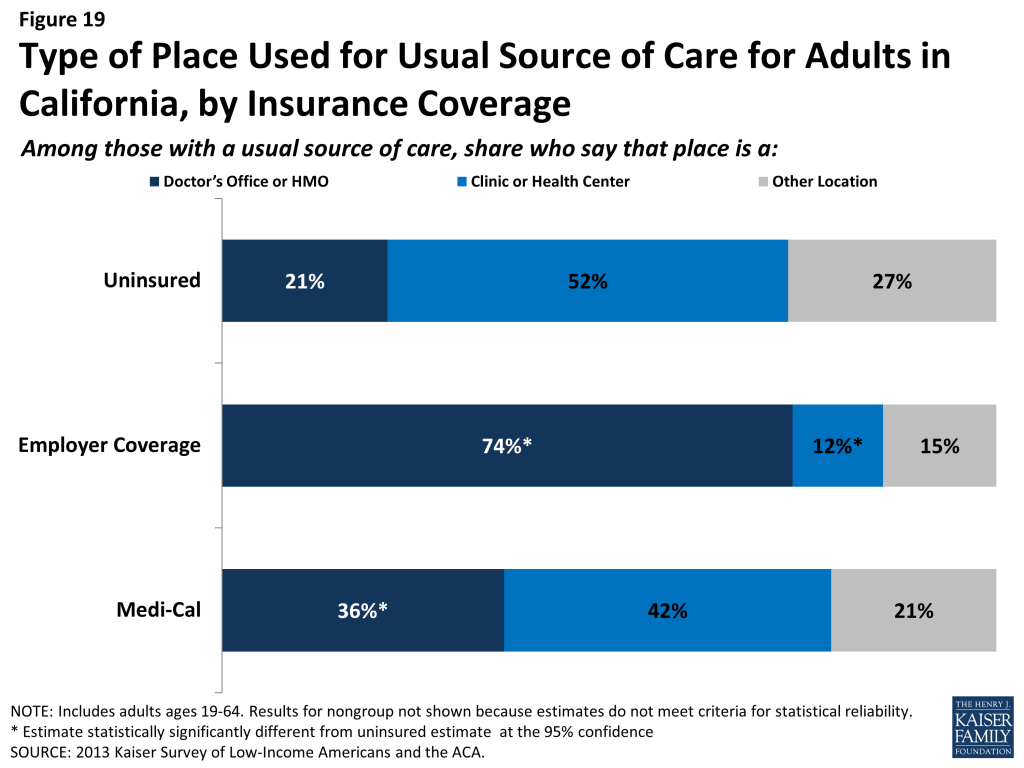

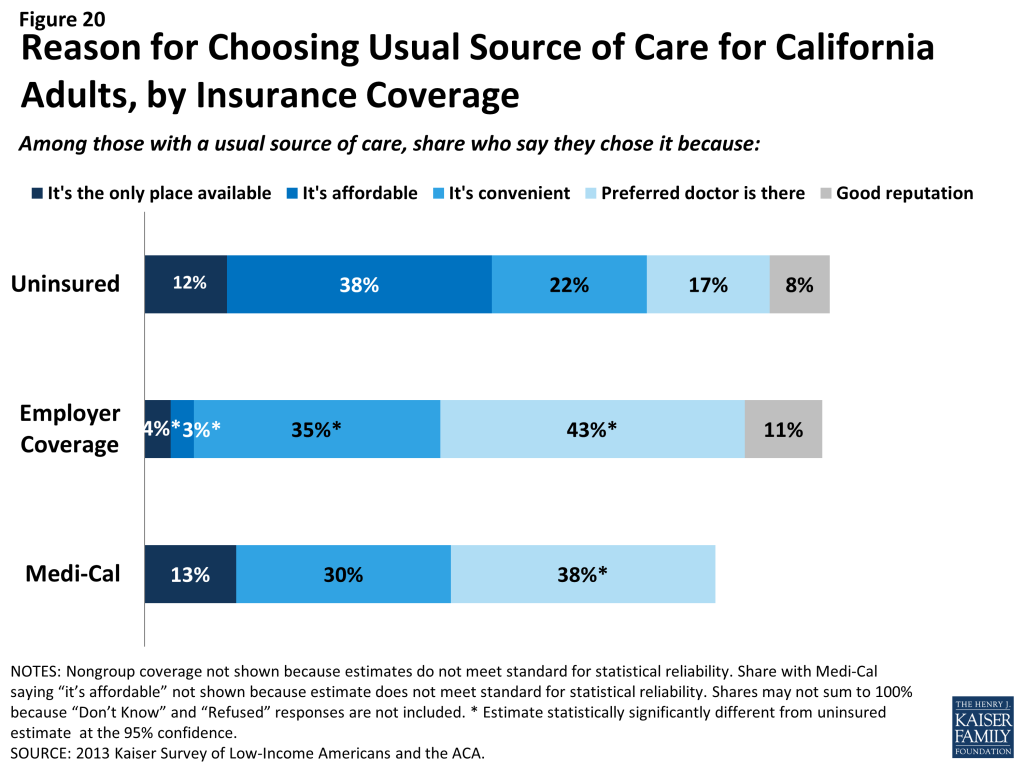

Many uninsured Californians report limited options for receiving health care when they need it. Uninsured adults in California are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician’s office when they do get care. Uninsured adults and adults with Medi-Cal are more likely than privately-insured adults to report that they have limited options for their usual source of care, with 12% of the uninsured and 13% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries reporting that they chose their usual source of care because it is the only option available to them, compared to 4% with employer coverage.

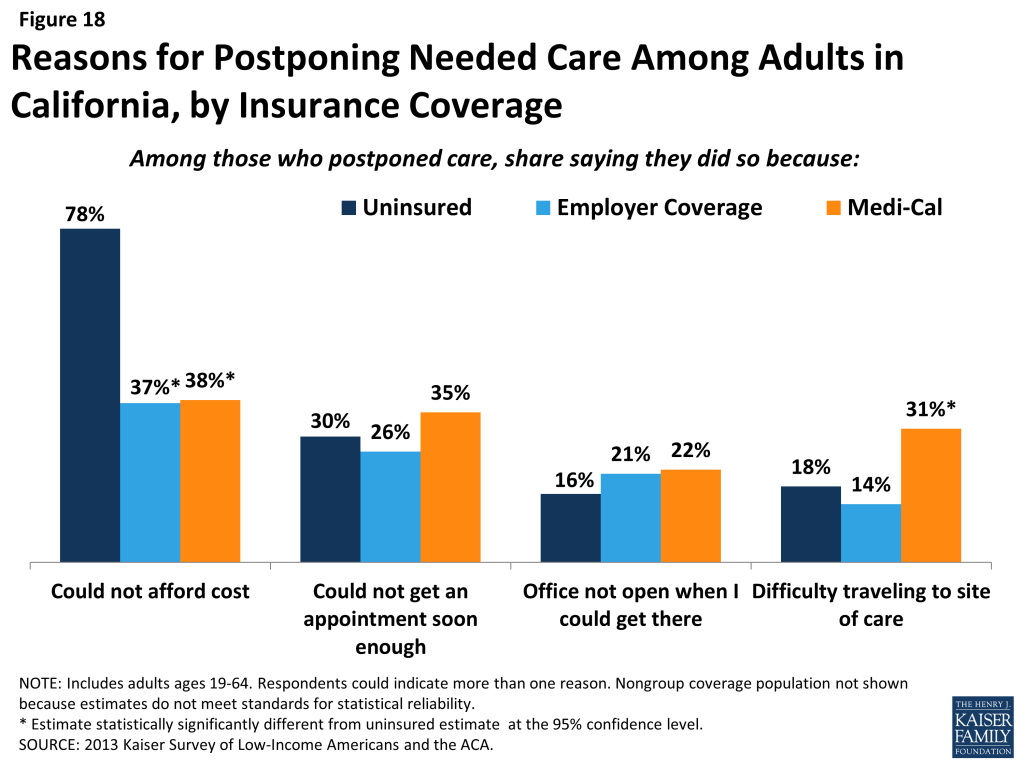

Informing ACA Implementation: The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage. Thus, gaining coverage is likely to connect many currently uninsured California adults to the health care system. Given the health profile of California’s currently uninsured population, there is likely to be some pent-up demand for health care services among the newly-covered. However, outreach may be needed to link the newly-insured to a regular provider and help them establish a pattern of regular preventive care. In particular, some individuals who have relied on emergency rooms or urgent care centers as their usual source of care may require help in establishing new patterns of care and navigating the primary care system. While California’s uninsured may have more options for where to receive their care once they obtain coverage under the ACA, clinics and hospitals that already see a large share of uninsured adults may continue to play an important role in serving this population once they gain insurance. Last, while coverage gains may reduce cost barriers to care, it will be important to monitor whether other barriers to care among the low-income population—such as transportation or wait times for appointments—continue to pose a challenge for access.

IV. Health Coverage and Financial Security

In addition to facilitating access to health care, health insurance serves primarily to protect people from high, unexpected medical costs. However, for low-income families in California, health costs can still be a burden, even if they have insurance. Understanding these issues can help policymakers monitor ongoing financial barriers to health services.

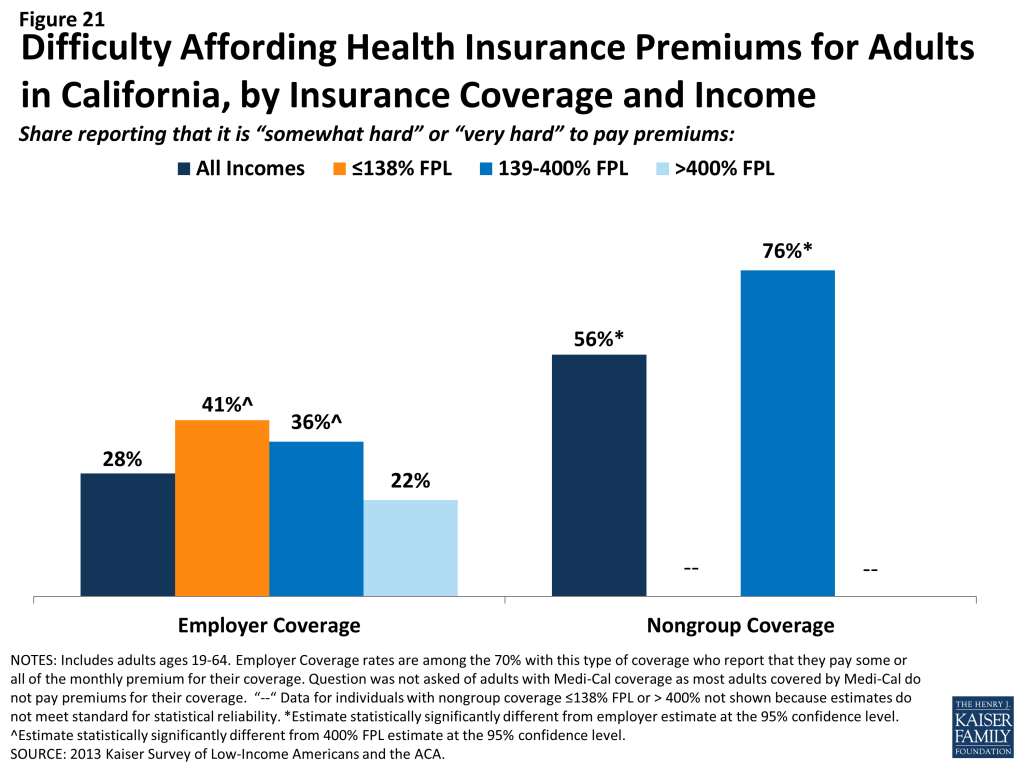

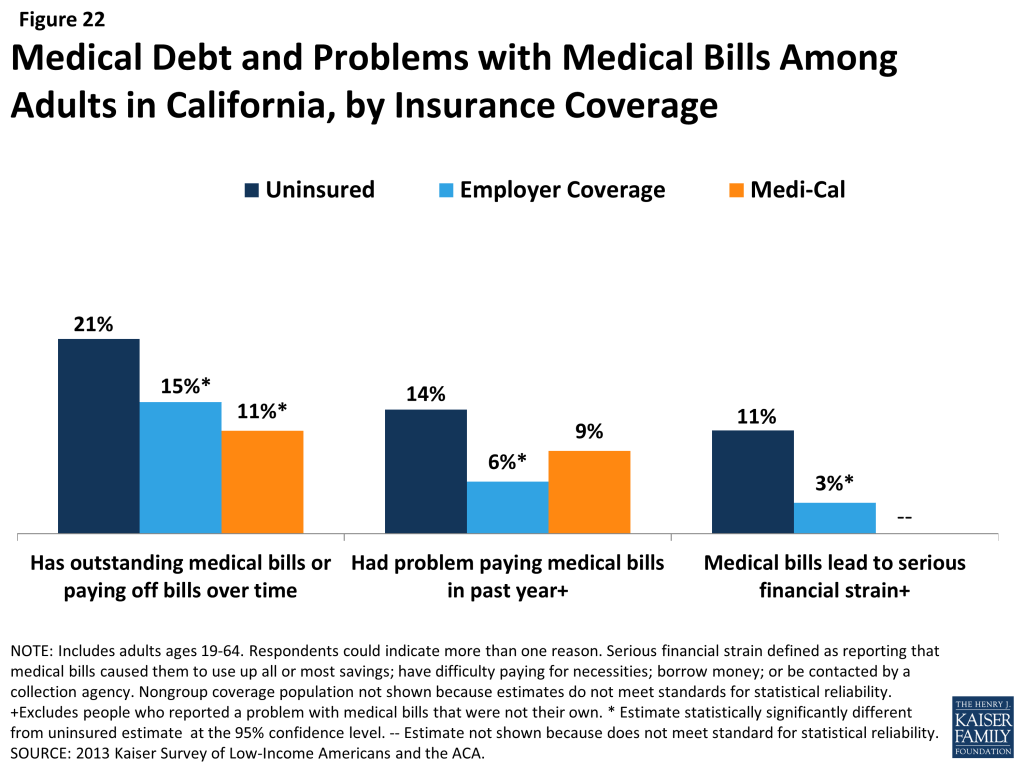

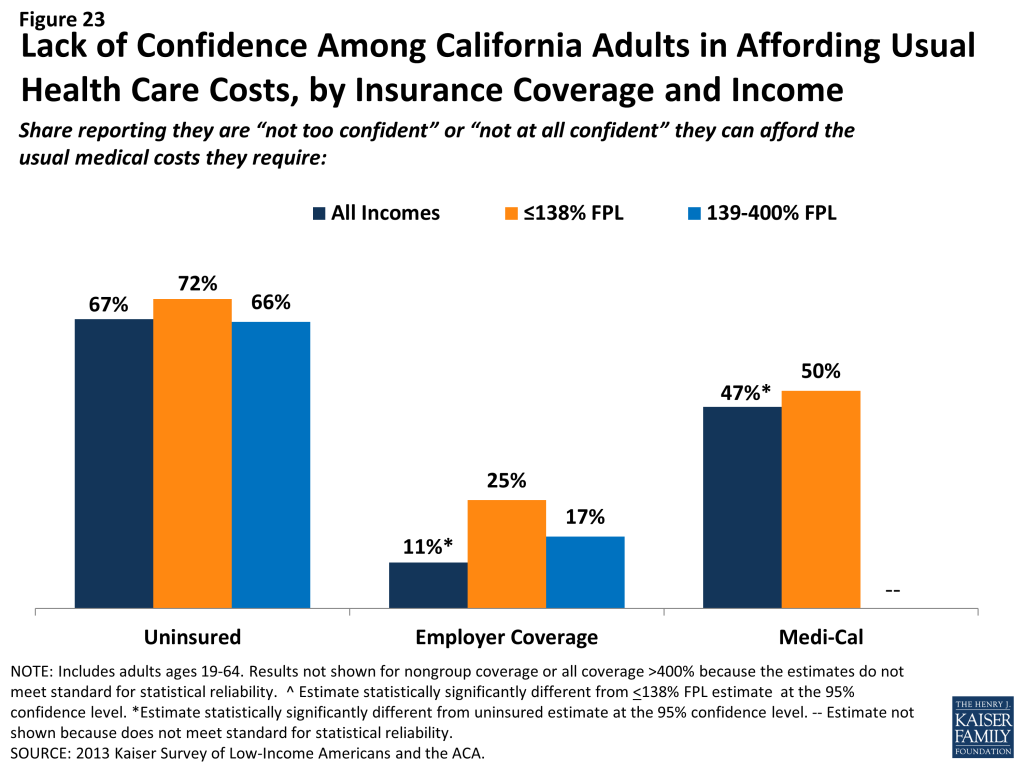

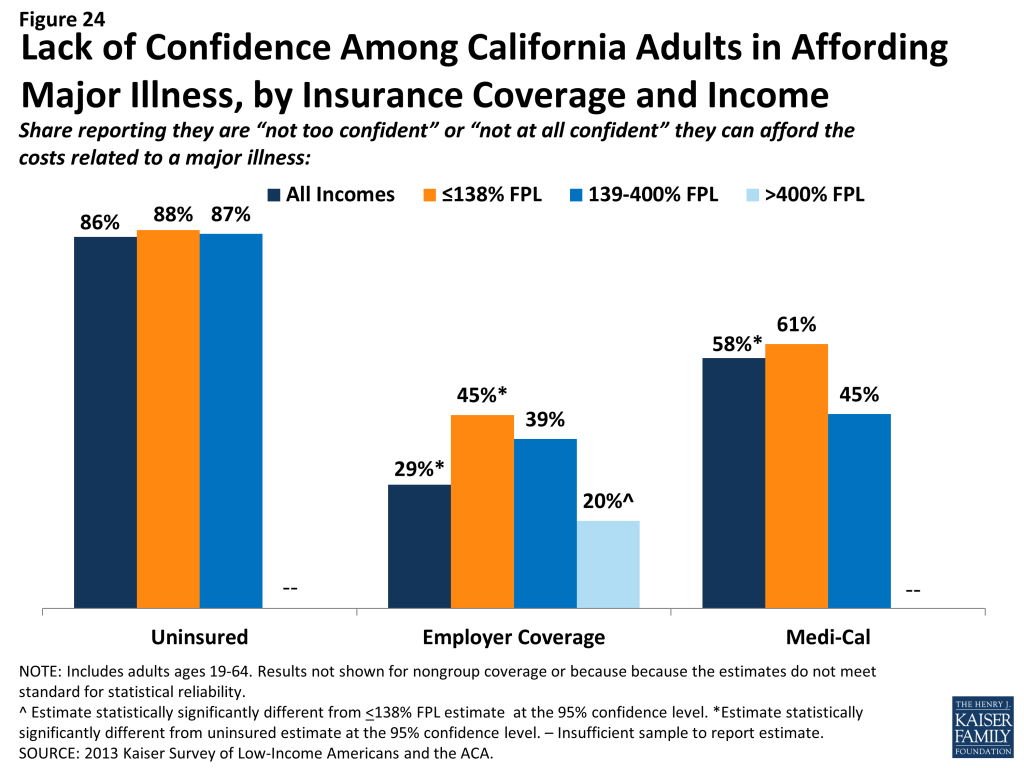

Health care costs pose a challenge for low- and moderate-income families in California, even if they have insurance coverage. Even among those with insurance, health care costs can be a burden, particularly for low- and moderate-income adults. About a third of low- and moderate-income adults in California who are covered by employer coverage report that their share of the premium is somewhat hard or very hard for them to afford, and three-quarters (76%) of moderate-income adults in California with nongroup coverage report difficulty paying their premiums. Health care costs translate to medical debt for many l0w-income adults, and these medical bills can cause serious financial strain. Notable shares of low-income insured adults also report that they lack confidence in their ability to afford health care, given their current finances and health insurance situation.

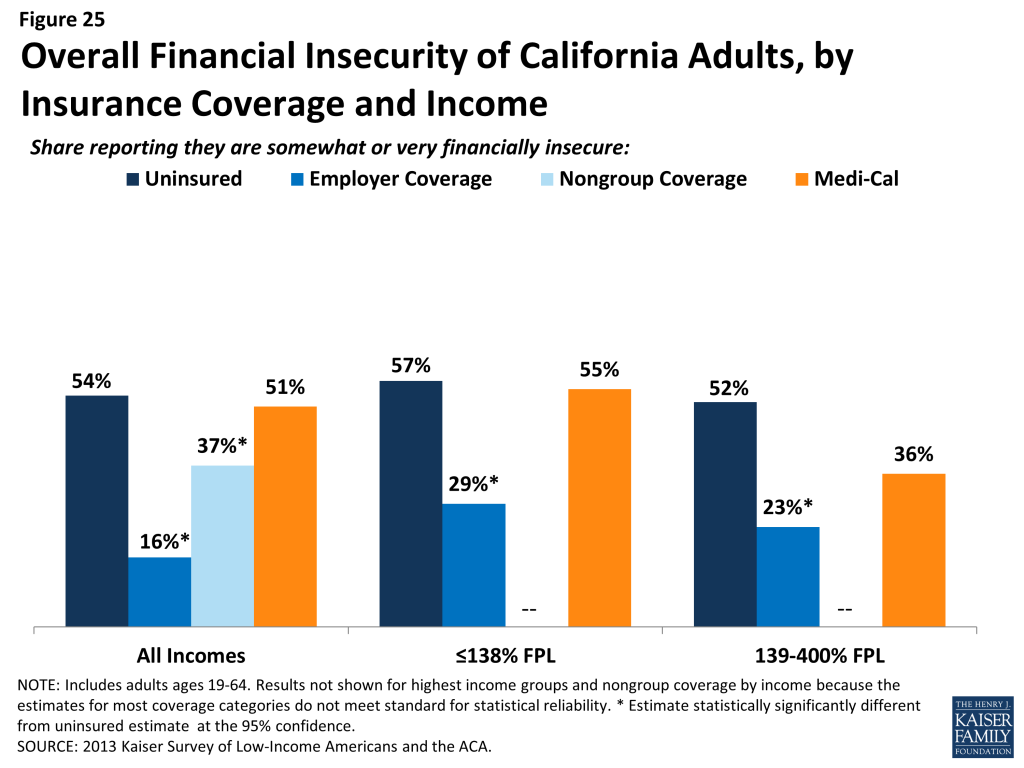

Low-income families face fragile financial circumstances. Low- and moderate-income adults in California across coverage groups report not being financially secure. However, adults who are low-income and uninsured or covered by Medi-Cal are particularly vulnerable to financial insecurity even outside of health care. General financial insecurity translates to concrete financial difficulties in making ends meet. Uninsured adults and those enrolled in Medi-Cal are more likely than privately-insured adults to have difficulty paying for other necessities, such as food, housing, or utilities, with 59% of the uninsured and 66% of those on Medi-Cal reporting such difficulty compared to 18% of those with employer coverage and 31% of those with nongroup coverage. While low-income adults across the coverage spectrum report high rates of difficulty paying for necessities, those with employer coverage report the lowest rates in this income group. These individuals may have stronger or more stable ties to employment than their counterparts with other or no insurance coverage. Higher rates of financial insecurity among Medi-Cal enrollees may reflect pre-ACA Medicaid eligibility rules, which targeted very vulnerable adults.

Informing ACA Implementation: Both insured and uninsured low-income adults in California struggle with medical bills and debt, and coverage expansions, assistance with premium costs and, for some, cost-sharing, and limits on out-of-pocket costs under the ACA have the potential to ameliorate the financial issues associated with the cost of health care. However, given survey findings that many low-income insured Californians continue to face financial challenges related to health care, it will be important to track whether there are ongoing financial barriers as people enroll in coverage and seek care. While insurance coverage can provide financial protection in the event of illness or injury, it is not curative of all of the financial burdens faced by low-income families. Given their overall situation, health insurance alone may not lift low-income Californians out of poverty, and many low-income California adults may continue to face financial challenges even after gaining coverage.

V. Low- and Moderate-income Uninsured California Adults’ Readiness for the ACA

As outreach and enrollment efforts are underway in California, information on low- and moderate-income adults’ access to tools for signing up for coverage and connections to outreach avenues can be helpful in addressing barriers. Key survey findings in this area include:

A majority of uninsured adults in California who are income eligible for coverage expansions reported knowing little or nothing about Medi-Cal and Covered California programs prior to the start of open enrollment. Despite ongoing media attention on the ACA, three-quarters (76%) of uninsured adults in California with incomes in the Medi-Cal target range (≤138% FPL) said they knew nothing at all or only a little about the Medi-Cal program, and five out of six (84%) uninsured adults in the income range for Covered California subsidies (139-400% FPL) reported that they knew nothing at all or only a little about Covered California. More recent national polling data indicates that lack of awareness remains high despite recent media attention on the ACA.

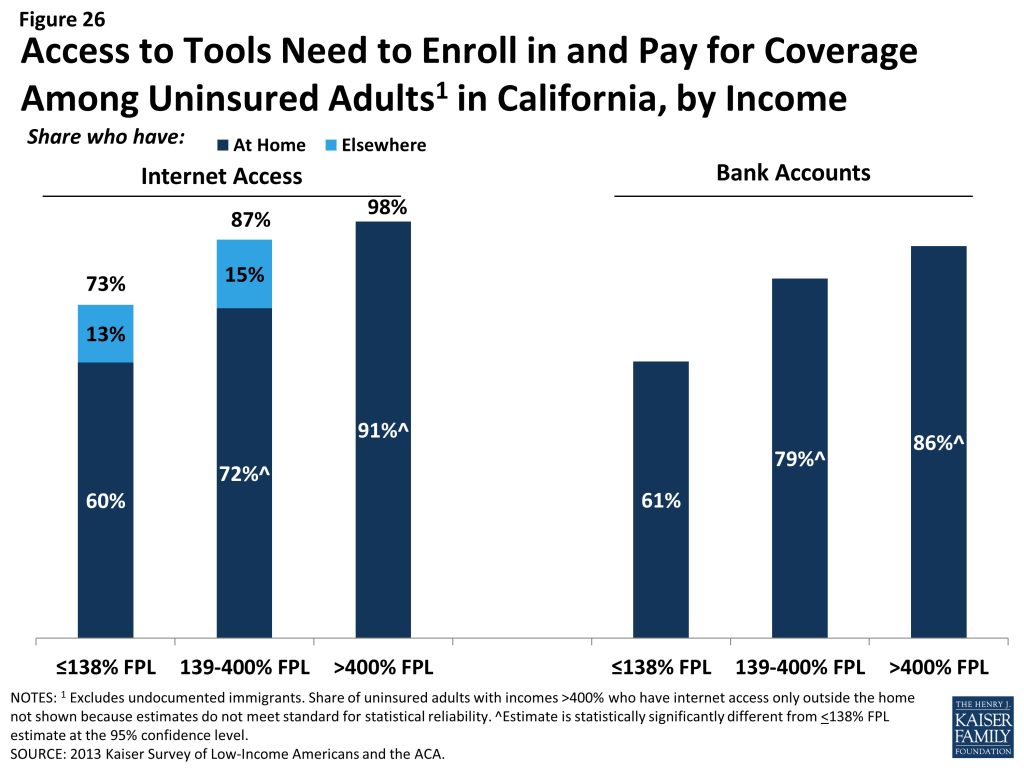

While most uninsured adults in California have the necessary tools for enrolling in coverage, some will experience additional logistical issues in signing up. Under the ACA, internet access is an important tool in accessing coverage. While the majority of uninsured adults have access to the internet either at home or outside the home, 27% of low-income (≤138% FPL) and 13% of moderate income (139-400% FPL) uninsured adults report that they do not have internet access readily available. For Covered California coverage, people will require a means to pay their premiums on a regular basis. While plans must accept various forms of payment, direct withdrawal from a checking account is a simple and reliable way to ensure that premiums are paid on time. However, over a fifth (21%) of uninsured adults in the income range for Covered California subsidies report that they do not have a checking or savings account.

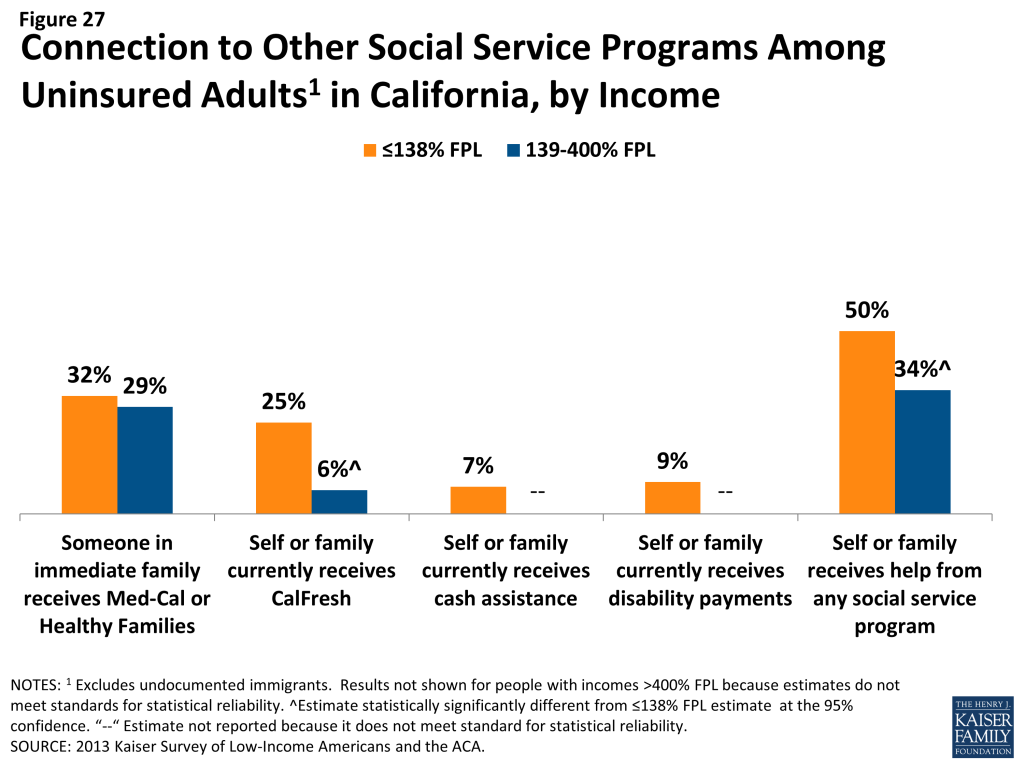

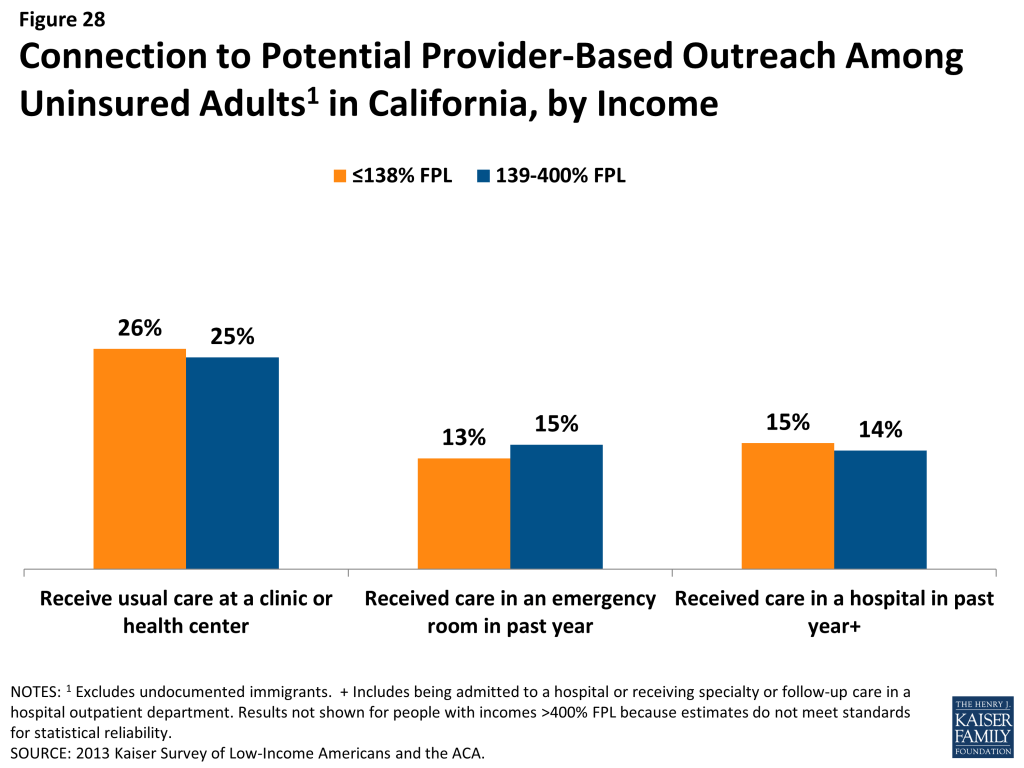

Many uninsured adults in California could be reached through targeted outreach avenues. Among uninsured adults in California with incomes in the range for Medi-Cal eligibility (≤138% FPL), half (50%) report that they or someone in their immediate family receives either CalFresh (California’s Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program), cash assistance, disability payments, or Medi-Cal, making “fast track” enrollment efforts through using information collected by other agencies a promising avenue for outreach. For those without a connection to social services agencies, outreach through providers may be a promising approach, as about one-quarter of low- or moderate-income uninsured adults in California report that they use a clinic or health center as their usual source of care. While fewer report using a hospital outpatient department for regular care, hospitals reach many uninsured California adults through periodic visits.

Informing ACA Implementation: Both survey findings and more recent polling data indicate that there is a great need for education about new coverage options among Californians targeted for expansions. Even once eligible individuals learn about coverage options, they may face logistical challenges in signing up. Californians without internet access may be able to enroll through other more traditional avenues, such as over the phone or in person at county or provider offices, but efforts may be needed to inform people of these other application routes, and some using them may experience a slower enrollment process than they would if they applied online. Finally, “fast track” enrollment efforts are a promising approach to facilitating enrollment, but broader efforts will also be needed to reach California’s eligible uninsured population. Replicating successful outreach and “inreach” strategies involving service providers and advocacy groups used during LIHP enrollment may be useful for reaching individuals for and Medi-Cal enrollment.7 Prior barriers to Medi-Cal and LIHP enrollment efforts, including language and cultural barriers, immigration status, and misconceptions about the programs, may continue to be challenges during the current and future enrollment efforts.

Report: Introduction

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect in California and across the country. These provisions include the creation of a new Health Insurance Marketplace, known in the state as Covered California, where moderate income families can receive premium tax credits to purchase coverage and, in states like California that opted to expand their Medicaid program, the expansion of Medi-Cal eligibility to low-income adults. With these coverage provisions, the ACA has the potential to reach many of the 7 million uninsured Californians. The ACA also makes improvements to coverage for people who already have insurance by setting new requirements for health plans.

To help the state prepare for the 2014 ACA coverage expansions, the federal government approved California’s five-year “Bridge to Reform” §1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waiver in 2010. In addition to other provisions,8 the waiver allows for federal matching funds for the creation of a county-based coverage expansion program for low-income adults not otherwise eligible for Medi-Cal, known as the Low Income Health Program (LIHP). This waiver coverage was intended to seamlessly transition to the ACA coverage expansions when they took effect. The majority of counties in the state participated in the LIHP program, and as of 2014 these enrollees were transitioned to Medi-Cal or Covered California coverage.9 ,10

LIHP reached many uninsured adults, and millions more are eligible for coverage through the Medi-Cal expansion or through Covered California.11 Though the ACA implementation is underway and people are already enrolling in coverage, policymakers in California continue to need information to inform the early stages of these coverage expansions. Reports of difficulties in enrolling in coverage and continued confusion and lack of information about the law point to some early challenges with implementation. Detailed data on the population targeted for coverage expansions and their past experiences with health coverage, current patterns of care, and family situation, can help policymakers target early efforts and provide insight into some of the challenges that are arising in the first months of new coverage.

Based on findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, this report provides a snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults in California at the starting line of ACA implementation and discusses how these findings can inform early implementation. The survey, conducted between July and September 2013, is a nationally representative survey that also includes a state-representative sample of over 2,500 nonelderly (age 19-64) adults in California. It was designed to focus on people targeted for financial assistance under the ACA and includes nonelderly adults with low incomes (≤138% FPL, or about $27,000 for a family of three in 2014) or moderate incomes (139-400% FPL, between approximately $27,000 and $79,000 for a family of three), as well as a comparison group with incomes over 400% FPL. The survey includes adults with employer coverage, nongroup, Medi-Cal, and other sources of coverage, as well as those with no health insurance. The California component of the survey and report on its findings complements a report on similar findings for the nation.12 This survey and report provides new data to help policymakers further understand early challenges in implementing health reform and assist outreach and enrollment workers, health plans, and providers and health systems. The survey also provides a baseline for future assessment of the impact of the ACA on health coverage, access, and the financial security of low- and moderate-income individuals in California. A detailed explanation of the methods underlying the survey and analysis is available in the Methods section of the report.

Report: Background: The Challenge Of Expanding Health Coverage In California

Lack of insurance coverage has been a longstanding policy challenge both nationwide and in California. Not having health insurance has well-documented adverse effects on people’s use of health care, health status, and mortality, as the uninsured are more likely to delay or forgo needed care leading to more severe health problems.13 Lack of insurance coverage also has implications for people’s personal finances, providers’ revenue streams, and system-wide financing.14 ,15 ,16 Because public coverage has been extended to many children and Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly, the vast majority of uninsured people are non-elderly adults. To address the challenge of the uninsured, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes an expansion of Medicaid (known in California as Medi-Cal) and the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces (known in California as Covered California).

California, the nation’s most populous state, has the largest number of uninsured of any state across the country. In 2012, twenty-one percent of the state’s nonelderly population was uninsured, or about 7 million people, which accounts for 15% of the uninsured nationwide.17 Los Angeles County alone, which has a population the size of many states, has a greater number of uninsured residents (2.2 million) than found in any state except New York, Florida, or Texas.18 Therefore, California’s actions to expand coverage through the Medi-Cal expansion and Covered California have implications not only for health coverage and access within the state but also for national goals of reducing the total number of uninsured.

California also is a highly diverse state, with 60% of the state identifying as a race other than White.19 The state is home to more than 10 million immigrants,20 including more than five million non-citizens, and has the largest number of undocumented immigrants in the nation.21 These unique characteristics of the state shape the challenge of extending health coverage and in implementing the ACA.

California’s Health Insurance Environment

Prior to the ACA, California had one of the highest uninsured rates in the nation and, correspondingly, one of the lowest rates of private insurance coverage, which includes group coverage obtained through an employer and individual coverage purchased directly from an insurance company (nongroup).22 One reason for the low rate is coverage is California’s unemployment rate, which at 8.7% is higher than the national average (7.3%).23 However, many workers in California lack health insurance: in 2012, one in four California workers was uninsured.24 Workers lack coverage for a variety of reasons, including not being offered coverage by their employer and not being able to afford coverage. Premiums and copayments for health coverage in California have been steadily rising over the past decade, and average premiums for nongroup coverage in California are higher than the national average ($572 per month in California compared to $490 per month nationally).25

Still, as in other states, private coverage is the main source of insurance among those with coverage in California, and the private insurance market accounts for nearly three quarters of covered lives in California (excluding the elderly population).26 California has a concentrated private insurance market, with six insurers accounting for three-quarters of the market in 2011.27 The state also has a long history of managed care, with the majority of enrollees receiving coverage through a managed care plan.28

Medi-Cal is a large player in the state, accounting for over a quarter of nonelderly covered lives, or about 7.3 million individuals.29 While Medi-Cal covers children in families with incomes up to 250% FPL[endnote 102550-49], eligibility for parents and adults without dependent children was more limited prior to the ACA and LIHP, leaving many adults without affordable coverage. Specifically, Medi-Cal was available only to parents with incomes up to the poverty level, and non-disabled adults without children were ineligible for coverage. The state also had adopted the option to eliminate the five year waiting period for coverage for eligible lawfully residing pregnant women and children and adopted the unborn child option to provide care to pregnant women, regardless of immigration status.30 However, other lawfully residing immigrants remained subject to a five-year waiting period before they could enroll in coverage, and undocumented immigrants remained ineligible to enroll in coverage.

California has the lowest Medicaid payment rates to physicians in the nation. In 2012, Medi-Cal payment rates to physicians for primary care services were 43% of Medicare rates, compared to a national average of 59%.31 Due to budget shortfalls, the state passed a 10% provider rate cut for most Medi-Cal providers, and this cut was implemented in January 2014.32 ,33 Simultaneously, under the ACA, California is required to pay certain physicians Medi-Cal fees that are at least equal to Medicare’s for a list of 146 primary care services; this fee increase is in place for 2013 and 2014, and the federal government will pay 100% of the cost of the difference between the increased rate and the state’s rate in place in 2009.34 ,35 Thus, fees paid to certain physicians for primary care services will be protected from the Medi-Cal rate cut in 2014 (because the federal government will fund the difference between the state’s rates and Medicare rates), but this federal funding and protection from rate cuts ends in 2015.

For uninsured residents in California, health care services are primarily financed and administered at the county level. Under California law, the state’s counties are “providers of last resort” for health services to low-income uninsured adults without other sources of care. California’s counties, therefore, have a history of financing, and in some instances delivering, health care to low-income, underserved, and uninsured individuals. All of California’s 58 counties have at least one health program for Medically Indigent Adults (MIA), and counties vary on the quantity and scope of health services covered.36 California also has a robust network of county hospitals, community health centers, and community clinics that make up a significant share of the state’s safety net system.37 These providers will play an important role in reaching, educating, and enrolling newly eligible individuals into coverage under the ACA.

Health Reform in California

Under the ACA, California will extend Medi-Cal coverage to citizens and eligible legal immigrants (those who have been U.S. residents for more than five years) with incomes up to 138% FPL ($16,105 for an individual or $27,210 for family of three in 2014). It is estimated that between 990,000 and 1.4 million Californians will enroll in Medi-Cal under the expansion by 2019.38

To assist the state in preparing for the Medi-Cal expansion in 2014, the federal government approved California’s five-year “Bridge to Reform” Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waiver in November 2010.39 The waiver provides the opportunity for California’s safety net hospitals, including county and University of California hospitals, to draw down federal matching funds to develop new programs and innovative approaches to improve quality of care through the creation of the Delivery System Reform Incentive Program (DSRIP). Federal funds are available for four priority areas, including (1) infrastructure development, (2) innovation and redesign, (3) population-focused improvement, and (4) urgent improvement in care.40 Twelve of California’s 21 designated safety net hospitals are participating in DSRIP, and each has developed a plan that describes specific improvement projects and related milestones. Milestones are reported to the state through semi-annual reports, incentive payments are tied to achieving each milestone.41

In addition to DSRIP and authority to transition Medi-Cal-only seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs) to managed care arrangements,42 the Bridge to Reform waiver allowed the state to draw down federal matching funds to expand coverage to low-income uninsured adults through the creation of a county-based Low-Income Health Program (LIHP). LIHP consisted of two programs: the Medicaid Coverage Expansion (MCE) for non-elderly, non-pregnant adults with family incomes at or below 133% FPL and the Health Care Coverage Initiative (HCCI) for non-elderly, non-pregnant adults with family incomes between 133-200%.43 Counties could elect to participate in LIHP and, if participating, decide whether to expand coverage to individuals with family incomes up to 133% FPL or up to 200% FPL (or a lower threshold set by the county). As of September 2013, 53 of the state’s 58 counties were participating in the LIHP program, and over 667,000 adults were enrolled.44 ,45 The state worked with the counties to transition LIHP enrollees to coverage options available under the ACA as of January 2014, transitioning nearly 644,000 beneficiaries to Medi-Cal and 24,000 beneficiaries to Covered California coverage in 2014.46 ,47

Also under the ACA, people with incomes up to 400% FPL who do not have an affordable offer of coverage are eligible to receive tax credits to purchase coverage through Health Insurance Marketplaces; citizens and legal immigrants who are not eligible for tax credits can purchase unsubsidized coverage. California was the first state in the country to pass legislation to create a state-based Marketplace under the ACA. The Marketplace, called Covered California, is governed by an appointed five-member board and operates as an independent public agency. Since its inception, Covered California has actively pursued grant funding to assist with planning and operations and received about $910 million in federal grants.48 Covered California enrollees can select among the plans offered by the participating 13 commercial health plans.49 Over three million Californians are estimated to be eligible to purchase coverage through Covered California, with about two million of those individuals eligible for premium tax credits.50

California’s early efforts enabled the state to reach many uninsured targeted for coverage expansions early in ACA implementation. For example, by September 2013, nearly all (almost 70,000) individuals eligible for the Medi-Cal expansion had enrolled in LIHP in Alameda County.51 However, many eligible uninsured remain across the state. For these individuals, outreach and enrollment efforts are essential to help educate them about coverage options and help them successfully complete an application. There are a range of outreach and education efforts underway in the state, including statewide marketing campaigns, community mobilization to reach people at the local level, provider training, outreach to transition people from LIHP coverage to Medi-Cal, and targeted efforts to reach vulnerable populations who may be newly-eligible for Medi-Cal.52 For example, the California Department of Health Care Services and The California Endowment, a private grant-making foundation, have been awarded federal matching funds for a $23 million Outreach and Enrollment Grant to enhance outreach and increase Medi-Cal enrollment, including support for Certified Enrollment Counselors.53 The funds will be distributed by the state to 36 county and regional organizations that must use the funds to target uninsured people who are difficult to reach or enroll, such as those with mental health needs, substance abuse disorders, the homeless, young men of color, as well as people with limited English proficiency.54 In addition, 125 health centers operating over 1,000 sites throughout the state received $25.1 million in federal grants in fiscal years 2013 and 2014 to help with outreach and enrollment assistance.55

Covered California is also investing heavily in outreach and enrollment efforts. For example, Covered California is using federal funding for an Outreach and Education Grant Program to engage the state’s uninsured population and increase awareness and understanding of health coverage options.56 ,57 The program has allocated $43 million in grants to 48 community organizations, including $37 million that was distributed in 2013 and $6 million allotted for 2014.58 These grants were primarily to organizations targeting individuals but also include some organizations targeting small businesses or providers.59 Covered California also established an Assisters Program and is working with community organizations to provide direct assistance to consumers to help them enroll in coverage. To further expand marketing and outreach, especially efforts aimed at uninsured young adults and uninsured Hispanics to bolster enrollment assistance and to sustain Marketplace operations, Covered California was awarded a $155 million federal grant in January 2014.60 These efforts overlay other state and local campaigns and ongoing outreach and enrollment activities.

A Profile of The Uninsured in California

Barriers to coverage in the past and state demographics are reflected in the characteristics of the uninsured population in California. For example, a majority of uninsured adults (52%) are low-income, in contrast to 10% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 1 and Appendix Table A1). Adults with Medi-Cal are the most likely of any coverage group to be low-income, reflecting the fact that prior to the ACA, adult income eligibility was limited. Further, the majority of uninsured Californians live in families where they or their spouse are working (71%)(Figure 2). However, not surprisingly, uninsured adults in California are less likely than adults with employer coverage to be in a working family.

Uninsured adults in California also differ from insured adults with regards to demographic characteristics, often reflecting association with income or work status. Uninsured adults are likely to be younger than insured adults, as younger adults have lower incomes and looser ties to employment than older adults. Two-thirds (66%) of uninsured adults are ages 19-44 as compared to 56% of adults with employer coverage or 52% with Medi-Cal (Appendix Table A1). There also are significant racial and ethnic differences in health coverage among nonelderly adults, primarily reflecting differences in income by race/ethnicity. For example, uninsured adults are more likely to be Hispanic – 52% of uninsured adults are Hispanic – than adults with employer coverage (26%). Over one third of uninsured adults in the state are noncitizens (36%), compared to 20% of adults with Medi-Cal or 10% of adults with employer coverage. Citizenship status may leave many uninsured adults ineligible for assistance, increasing the likelihood they will remain uninsured.

As efforts continue to reach, educate, and enroll individuals into health coverage under the ACA, it is important to remember who the ACA aims to help and how their characteristics and previous interactions with the health system may inform efforts to connect with them.

Report: I. Patterns Of Coverage And The Need For Assistance

Coverage Dynamics among the Insured and Uninsured

Health insurance coverage is dynamic, and every year thousands of Californians gain, lose, or change their health coverage. However, for most uninsured adults in California, lack of coverage is a long-term issue that spans many years. Many uninsured adults in California reported trying to obtain coverage in the past but were unsuccessful due to barriers such as ineligibility for public coverage or high costs of private coverage. Under the ACA, millions of uninsured are projected to gain coverage as those barriers are removed, but some may continue to experience gaps or changes in coverage.

For most currently uninsured adults in California, lack of coverage is a long-term issue.

While some people lack health insurance coverage during short periods of unemployment or job transitions, for many uninsured adults in California, lack of coverage is a chronic problem. The survey shows that a large share of uninsured adults in California have been without insurance for a very long period of time: half (50%) reported being uninsured for 5 years or more, including 22% of the uninsured who reported that they have never had coverage in their lifetime (Figure 3). The length of time adults have been uninsured does not differ significantly by income in California (see Appendix Table A2). However, Hispanic uninsured adults were more likely than non-Hispanic uninsured adults to report that they have never had coverage in their lifetime (data not shown).

It is important for policymakers in California implementing coverage expansions to be aware that people targeted by the ACA have varying levels of experience with the insurance system. While some previously had coverage, a large share of uninsured adults in California has been outside the insurance system for quite some time. The long-term uninsured may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate their new health insurance. As enrollment has lagged among the Hispanic population in California, it is particularly important to ensure that translation issues or lack of clarity on use of immigration information does not impede outreach and education efforts.61 Special efforts in the state to target the Hispanic population, as well as others who have been outside the health coverage system, are therefore particularly important.

Many uninsured adults in California report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage.

The uninsured report a desire to obtain coverage, but prior to implementation of the ACA in California, options for coverage—particularly for the low-income—were limited. The vast majority of uninsured adults in California do not have access to employer coverage. More than eight in ten (82%) uninsured adults in California report no access to employer coverage, either because no one in their family is working for an employer, their or their spouse’s employer does not offer coverage, or they are ineligible for that coverage (Table 1). For example, 45% of uninsured adults in California are in a family without an employer, meaning both they and their spouse (if married) are either not working or are working but are self-employed. Over a quarter (28%) of uninsured adults are in a family that has an employer who does not offer coverage to any workers, and nearly one in ten (8%) are in a family that works for an employer who offers coverage but they are ineligible for that coverage. Most of whom are ineligible because they work part-time or are in a waiting period. About one in five (18%) uninsured adults in California does have access to coverage through an employer, but the majority report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable.

| Table 1: Access to Employer Health Coverage Among Uninsured Adults in California | ||||

| All | By Income | |||

| ≤138% FPL | 139-400% FPL | |||

| % | % | % | ||

| No Access to ESI | 82% | 84% | 79% | |

| No one in family has an employer* | 45% | 53% | 33%^ | |

| Firm doesn’t offer coverage | 28% | 25% | 35%^ | |

| Not eligible for coverage | 8% | — | 11% | |

| Access to ESI | 18% | 16% | 21% | |

| Cannot afford premium | 10% | 8% | 13% | |

| Don’t think need coverage | — | — | — | |

| Some other reason | 6% | 6% | 6% | |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown, they account for less than 5% of the uninsured population.* Individuals who are self-employed without other employment are treated as not having an employer.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or unweighted cell sizes below 30 are not provided.^ Estimate statistically significantly different from ≤138% FPL at the 95% confidence level.SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | ||||

Similarly, low-income adults had limited access to coverage through Medi-Cal prior to the ACA. While the state had expanded eligibility to children through Medi-Cal and Healthy Families (California’s former Children’s Health Insurance Program, which has now been consolidated into Medi-Cal), Medi-Cal eligibility for adults remained very limited (see Background for more detail). Prior to the state’s early expansion efforts through the LIHP, Medi-Cal eligibility for parents was limited to those with incomes below poverty, and non-disabled adults without dependent children were ineligible regardless of their income.62 While eligibility for low-income adults began to be expanded through the creation of the LIHP in 2010, county participation in the program was phased in and the income level at which individuals were covered varied across counties. In addition, some individuals who were eligible for Medi-Cal remained uninsured because they were not aware that they were eligible for coverage or they faced application or enrollment barriers. While California had already adopted many enrollment simplifications for children prior to the ACA, the enrollment processes for adults remained more burdensome than those for children.63

The previous gaps in Medi-Cal eligibility for adults and difficulties with the enrollment process posed barriers for many low-income adults seeking coverage. Nearly one quarter of uninsured adults in California (24%) reported trying to sign up for Medi-Cal in the past five years (Figure 4 and Appendix Table A2). The majority of adults in California who tried to sign up for Medi-Cal were unsuccessful, and among those, most (12% of the uninsured) were unable to sign up because they were told they were ineligible (Figure 4). Notably, results are similar when looking at just uninsured Californian adults in the income range for Medi-Cal expansion under the ACA (≤138% FPL). While some of the individuals who were told they were ineligible for Medi-Cal may have been eligible for other programs, such as LIHP, most likely remained ineligible for public coverage until the ACA expansion in January 2014, barring a change in their income.64

Prior to the ACA, there were also barriers to obtaining coverage on the nongroup, or individual, market. This type of coverage was not guaranteed in California, and insurance companies could charge higher premiums for sicker or older individuals, making coverage unaffordable for many uninsured adults.65 Uninsured Californians also report trying to obtain nongroup coverage. One in six uninsured adults in California (17%) reported trying to obtain nongroup coverage in the past five years. Most of these Californians (10% of the uninsured) did not purchase a plan because the policy they were offered was too expensive (Figure 4).

Many of the barriers to coverage that the uninsured have reported facing in the past are addressed by the ACA. Large employers (>50 workers) face penalties if they do not offer affordable coverage to their workers,66 and in states that chose to expand Medicaid such as California, eligibility for Medicaid includes most adults with incomes at or below 138% FPL. Further, millions of uninsured families are now able to purchase coverage in the Marketplaces and receive premium tax credits to reduce the cost. Insurers are no longer able to deny coverage based on health status and are limited in what they charge people based on age, location, and tobacco use status. However, some uninsured adults may continue to face barriers to coverage. As was the case before the ACA, undocumented immigrants remain ineligible to enroll in Medicaid, and recent lawfully residing immigrants are subject to certain Medicaid eligibility restrictions. One in five uninsured adults in California is an undocumented immigrant67 and will not have access to coverage under the ACA.

For those who are eligible for assistance, education efforts regarding new coverage options are important. People who have attempted to obtain coverage in the past may be unaware that rules and costs have changed under the ACA. Outreach and education will be needed to inform people that eligibility rules have changed and that financial assistance is available to offset the cost of coverage.

Health coverage is not always stable.

For most insured adults in California, coverage is continuous throughout the year and over time. However, when accounting for both insured people with a gap in their coverage and uninsured people who recently lost coverage, the survey indicates that sizeable shares of adults in California lose or gain coverage over the course of a year.

Among California adults who were insured at the time of the survey, 5% reported being uninsured at some point in the past year (see Table 2), and those who had a gap in coverage were uninsured for nearly half the year (7.4 months) on average (data not shown). Further, some currently uninsured adults had coverage at some point within the past year. Among uninsured adults in California, nearly one in six (16%) reported having lost coverage within the last year. Among both those with a gap in coverage or who recently lost coverage, the majority reported that they most recently had employer coverage (data not shown).

In addition to those who lose or gain coverage over the course of a year, many adults in California who have coverage throughout the entire year have a change in their health insurance plan. Among adults with insurance coverage, 9% had coverage for the entire year but reported that they had a change in their coverage (Table 2). Coverage changes may be due to a number of different factors including changes in employment, changes in eligibility for public programs, or simply a change in plan or insurance carrier. The most common reasons for a change in coverage appear to be related to changes in employment or changes in plans during open enrollment, as most Californians with coverage change reported changing from an employer plan to another employer plan.

| Table 2: Coverage Dynamics Among Insured and Uninsured Adults In California, by Income and Current Coverage | |||||||||

| All | By Income | By Current Coverage | |||||||

| ≤138% FPL | 139-400% FPL | >400% FPL | Employer | Nongroup | Medi-Cal | ||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |||

| Insured Adults | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Gap in Coverage in Past Year | 5% | 10% | 7% | — | 3% | — | 13% | ||

| Changed Coverage During Year | 9% | — | 8% | 9% | 8% | — | — | ||

| Same Coverage for Full Year | 87% | 82% | 85% | 90%^ | 89% | 85% | 80% | ||

| Uninsured Adults | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Uninsured Full Year | 83% | 84% | 84% | 76% | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Lost Coverage Within Past Year | 16% | 16% | 16% | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs. “–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or unweighted cell sizes below 30 are not provided.^ Estimate is statistically significantly different from ≤138% FPL estimate at the 95% confidence level.SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||||||

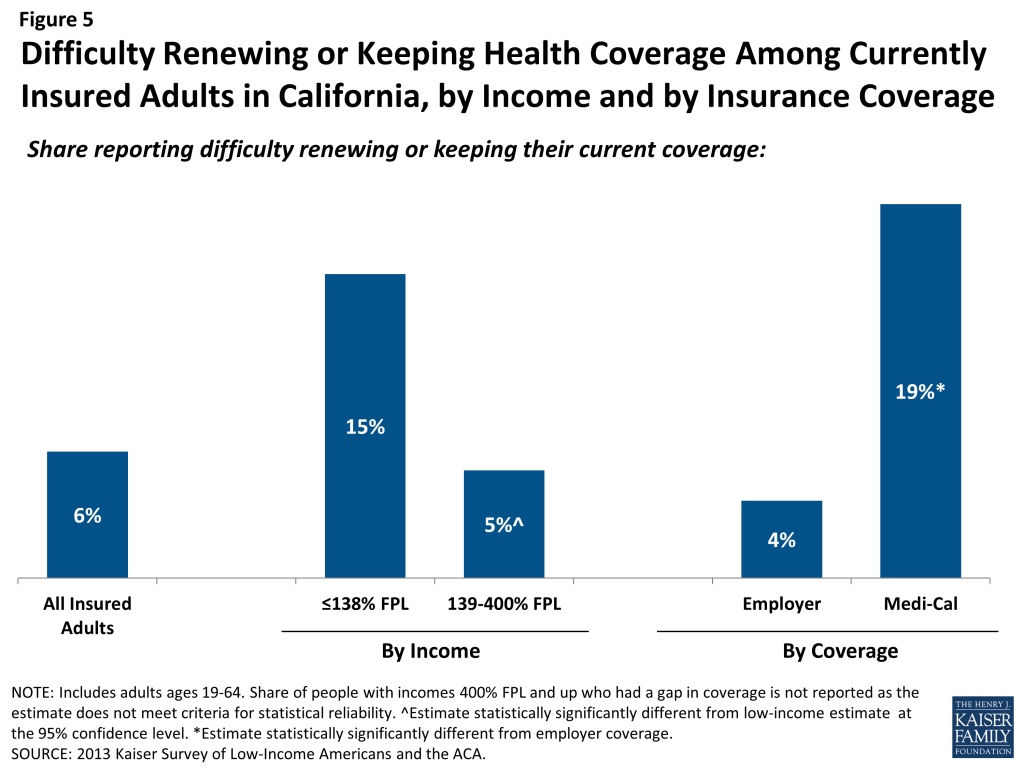

Last, a small number of insured adults in California reported challenges in either renewing or keeping their coverage, another indication of instability in coverage throughout the year. Reflecting eligibility rules, adults with Medi-Cal are the most likely to report a challenge (19%) compared to adults with other insurance types (Figure 5). Medi-Cal eligibility is closely tied to income, and adults’ income may fluctuate throughout the year; adults must report changes in income that may affect their eligibility throughout the year, and low-income people are very likely to have part-time or seasonal work that leads to income fluctuations over the course of a year. In addition, adults must renew their Medi-Cal coverage either in person or online at least annually.

The survey findings on changes in insurance coverage during the year have implications for implementation of health reform in California. While there has been much focus on enrolling currently uninsured people into Medi-Cal or Covered California coverage, survey findings demonstrate that people will continue to move around within the insurance system throughout the year. Many people lose or gain employer coverage over the course of a year due to changing economic conditions and the delicate relationship between employment and health insurance. Further, there is some churning in insurance coverage resulting from Medi-Cal income eligibility limits: as adults’ income fluctuates, they may gain or lose Medi-Cal eligibility. Adults may also experience gaps in Medi-Cal coverage due to renewal requirements.

Gaps in coverage can cause people to postpone or forgo health care or accumulate medical bills,68 and changes in insurance plans may disrupt continuity of treatment. By providing for insurance options across the income spectrum and facilitating coverage outside the employment-based system, the ACA may help adults have coverage continuously throughout the year. Renewal simplifications for Medi-Cal coverage enacted as part of the ACA may also address issues in coverage disruptions: whereas previously all adults in California had to submit a paper form and documentation of income for Medi-Cal renewal, provisions under the ACA provide new options for them to renew on-line or by phone and use pre-populated forms when possible to reduce the need for paper documentation.69

However, even after implementation, adults are likely to experience coverage changes due to job changes or income fluctuation. To further help reduce churning on and off of Medicaid coverage, CMS has offered states the ability to adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for parents and other adults through Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration authority, and the federal government is finalizing policies regarding matching funds for this provision. Though many states use continuous eligibility for children in Medicaid, as of fall 2013, no state, including California, had adopted this strategy for adults. Other potential efforts to address churning in insurance coverage include plan coordination across Medi-Cal and Covered California—for example, requiring plans to provide for transition plans, engage in information sharing, or align provider networks—and having an ongoing presence of application assistants to help with coverage transitions.70 Because implementation is not a “one shot” effort that will be done once Californians are enrolled or transferred to Medi-Cal in the early part of 2014, it will be important to have ongoing efforts to enroll and keep people in coverage.

Report: Ii. What To Look For In Enrolling In New Coverage

How Low-and Moderate-Income Adults in California Sign Up For and View Their Coverage

While many currently uninsured adults in California have limited experience in signing up for and using health coverage, past successes and challenges of insured low- and moderate-income adults can inform the experiences of those seeking coverage under the ACA. A majority of insured Californians do not experience problems choosing, enrolling in, and using their coverage, and this pattern holds true for both those in Medi-Cal and private insurance. Still, based on the experience of their insured counterparts, the uninsured population in California that is being targeted by the ACA coverage expansions is likely to encounter some barriers in the process of choosing and enrolling in coverage. While the ACA aims to make the process smoother, it is likely that some challenges inherent in the complexity of health coverage will require concerted efforts to address.

While many adults in California reported facing no difficulty in applying for Medi-Cal coverage prior to the ACA, some encountered difficulties in the process of applying for public coverage in the past.

In comparison to the process for gaining coverage through an employer—which is typically facilitated by the firm or a representative and may require limited action on the part of the insured—applying for publicly-financed coverage typically requires proactive steps to gain coverage. Adults in California who currently have Medi-Cal or who have attempted to enroll in the past five years reported little difficulty in enrolling in Medi-Cal. Almost half of adults (48%) who applied to Medi-Cal said the entire process was very or somewhat easy. However, the rest found at least one aspect of the process – finding out how to apply, filling out the application, assembling the required paperwork, or submitting the application – to be somewhat or very difficult. The most commonly reported difficulty was assembling the required paperwork, which over a third (34%) of Californians who enrolled or applied said was somewhat or very difficult (Figure 6 and Appendix Table A3).

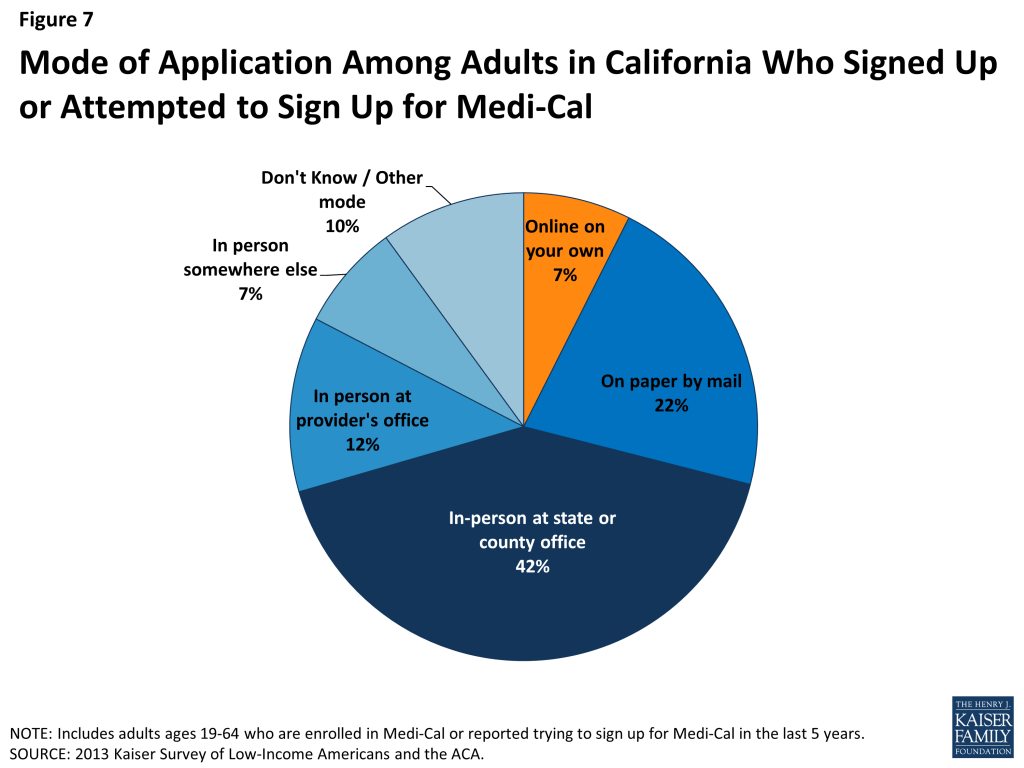

In recent years, California, along with many other states, has made strides towards providing individuals multiple avenues to enroll in coverage, including through online applications to facilitate access to coverage and ease administrative burdens.71 However, more than four in ten California adults (42%) who have applied to Medi-Cal in the past five years reported that they did so through traditional routes—that is, in person at a state or county government office—and only 7% reported using an online application (Figure 7).

The ACA includes provisions to further simplify the application, enrollment, and renewal process for coverage in all states. These requirements include the adoption of a single streamlined application that is available online, by phone, and on paper and that screens for all health coverage options; electronic transfers of accounts between agencies to facilitate transitions across health coverage programs; and reliance on trusted sources of electronic data, rather than requesting paper documentation, to verify eligibility criteria.72 As of late 2013, California and other states were still in the process of implementing many of these changes and coordinating enrollment processes with Covered California.73 Ongoing efforts in the state are also trying to make the process of enrolling in Medi-Cal coverage a more positive and welcoming experience, which calls for a culture shift to reorient Medicaid management, systems, and caseworker training away from welfare-style “gatekeeping” and toward encouraging participation.74

In addition, state and county investments are being made to train professionals and dedicate resources to assist with enrollment into new Medi-Cal and Covered California coverage options. Through federal grant funds, private investments, and dedicated local efforts, California has developed a robust outreach network that relies heavily on community organizations, such as community health centers. In-Person Assisters, referred to in California as certified enrollment counselors, and Navigators are being trained by Covered California to help individuals and families enroll in both public and private coverage. However, backlogs in certifying enrollment counselors have delayed the rollout of assistance available at the local level.75 It is possible that uninsured Californians applying for coverage after these new processes are implemented and the full range of assistance is in place will encounter fewer challenges in navigating the enrollment process than applicants have in the past.

When adults with Medi-Cal or private insurance plan have a choice of plan, they do not always prioritize costs over other plan features in making that choice, and many find some aspect of the plan choice process to be a challenge.

As Californians gain coverage, many will have the option to select an insurance plan. People may chose a particular plan for a variety of reasons, including low cost, choice of providers, recommendations from friends and family, or coverage of a particular benefit. Among the 58% of insured adults in California who had a choice of plans,76 roughly three in ten (27%) reported that they chose their plan because their costs would be low, 29% because it covered a wide range of benefits or a specific benefit that they need, and 27% because of its provider network (Figure 8 and Appendix Table A4).

In choosing a plan, Californians may face challenges in comparing costs, services, and provider networks across plans, as these factors typically varied greatly across plans in the past. In general, insured adults in California reported that they did not have difficulty in comparing their plan choices, but 38% found some aspect of plan choice—comparing services, comparing costs, and comparing providers— to be difficult (Figure 9 and Appendix Table A4). Insured adults in California were least likely to report difficulty comparing costs (versus providers or services) across plans (17%).

As enrollment numbers for particular plans are released and policymakers in California begin to assess plan choice among new enrollees, these findings can inform evaluations of plan choice under the ACA. While California has a concentrated private health insurance market, with six insurance carriers accounting for three-quarters of business, each offers a variety of plans to choose from. In Medi-Cal, not all enrollees have a choice of plans,77 and those that do have a choice face a limited number of standardized options. Still, people may face challenges in choosing among even limited options. While the ACA requires health plans in Covered California to provide a standard set of benefits and provide detailed information about what services are covered, which could make it easier for individuals to select a plan, it is important to bear in mind that, even before the ACA, insured adults faced some challenges in comparing and selecting insurance coverage. While provisions in the ACA could address these challenges, some are inherent to the complexity of insurance coverage. In particular, low-income adults who receive Medi-Cal may require assistance in navigating plan choices if they live in counties that have more than one plan, as provisions requiring comparable information on plans do not apply to Medi-Cal.

Further, contrary to expectations that people may opt for the lowest cost plan,78 survey findings indicate that Californians place value on a range of factors related to insurance, including scope of services and provider networks. Thus, assessments of whether people are choosing the optimal plan for themselves and their families will need to consider the multiple priorities that people balance in plan selection.

Overall, insured adults in California reported satisfaction with their current coverage but also reported gaps in covered services and problems when using their coverage.

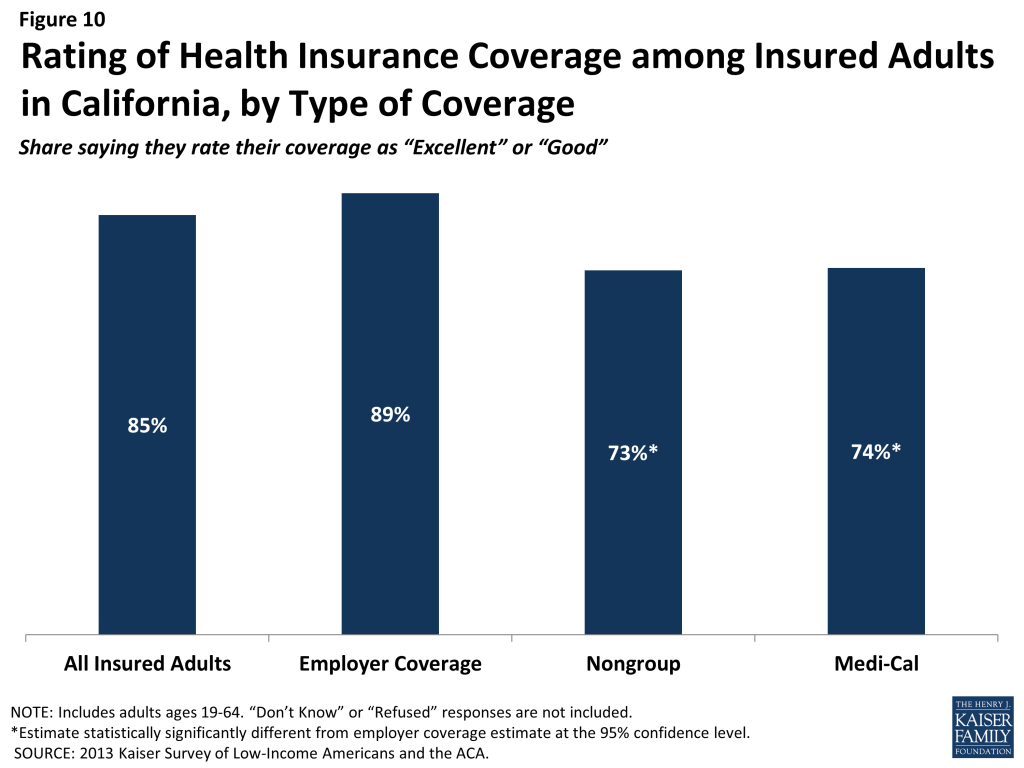

Most insured adults in California reported high levels of satisfaction with their current coverage, but they also reported gaps in services that are covered by their current insurance. Eighty-five percent of insured adults in California rate their coverage as excellent or good (Figure 10). Adults with employer coverage gave plans high ratings, with 89% grading their plans as excellent or good. Adults with Medi-Cal or nongroup coverage were less likely to give their plans high ratings, but nearly three-quarters in each coverage group (74% and 73%, respectively) rated their plans as excellent or good.

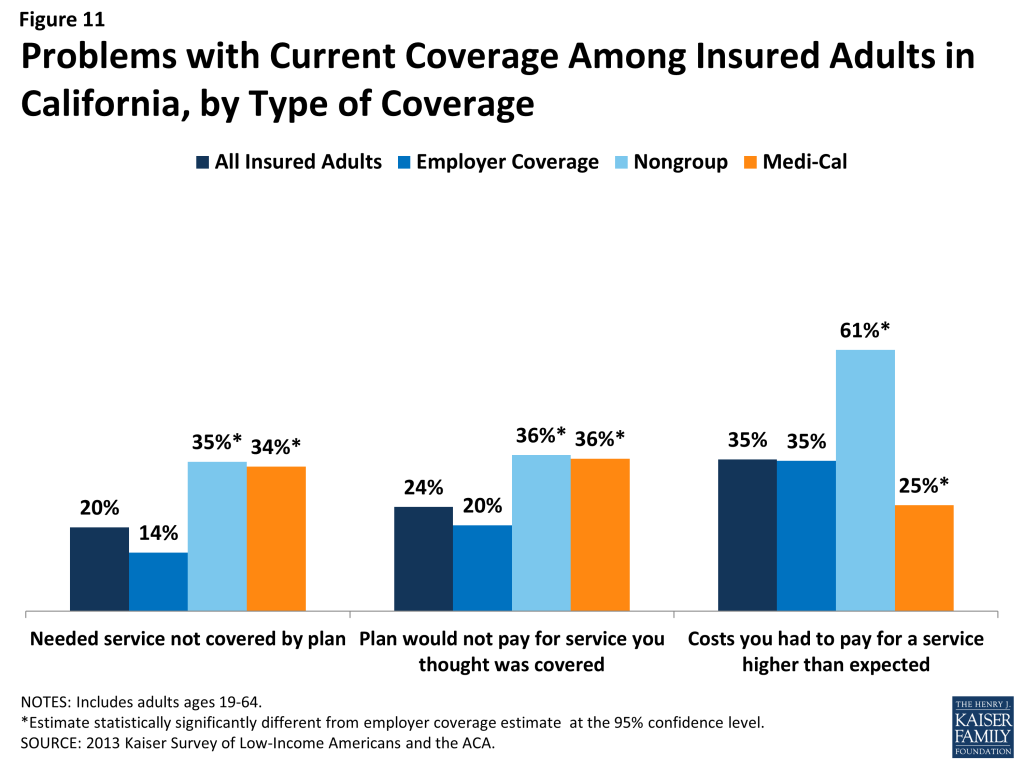

Despite the high ratings, notable shares of insured adults in California reported a problem with their plan. Specifically, one in five (20%) insured adults reported needing a service that is not covered by their current plan (Figure 11 and Appendix Table A5). People with Medi-Cal coverage (34%) or nongroup coverage (35%) are more likely to report that their plan does not cover certain services compared to those with employer coverage (14%). The most frequently reported services people say they need but lack coverage for are ancillary services, such as dental, vision care, and chiropractor services. In private health coverage, these ancillary services are often covered under stand-alone private insurance policies that must be purchased separately from health coverage, and in Medicaid, most are not federally-required benefits, but rather are covered at state option. Lack of coverage for adult dental services in Medicaid—the most frequently reported service needed but excluded from coverage—has been a longstanding issue facing beneficiaries and providers, despite a particularly high need among the low-income population.79 In SFY2010, California had eliminated most adult dental services in Medi-Cal due to budget restrictions,80 though the state plans to restore this benefit as of May 2014.81

Insured adults in California also reported experiencing other problems with their insurance plans. Many insured adults reported facing a problem with their current insurance plan covering a specific benefit, either because they were denied coverage for a service they thought was covered (24%) or their out-of-pocket costs for a service were higher than they expected (35%). Some of these services may be over-the-counter products, which are excluded from the majority of insurance plans but which people may believe their plans should cover. Reports of these difficulties varied by insurance coverage. California adults with Medi-Cal or with nongroup coverage (both 36%) were more likely than those with employer coverage (20%) to report they were surprised that their plan would not cover a service they believed was covered. Pre-ACA, adults with Medi-Cal coverage had particularly high health needs, which could explain why they reported relatively high rates of problems. In contrast, the results for nongroup could reflect limits on coverage. Adults with Medi-Cal (25%) were less likely to report facing higher costs than expected than privately insured adults (35% among those employer coverage and 61% among those with nongroup). This pattern most likely reflects the nominal out of pocket costs Medi-Cal beneficiaries are required to pay compared to the high cost-sharing of many private plans.

Among the goals of the ACA was ensuring that the coverage people gained provided at least a basic level of coverage and that the Marketplaces helped people navigate their insurance coverage. Thus, new coverage must include a set of essential health benefits (EHB), and participating plans in Covered California must report information on claims payment policies, cost-sharing requirements, out-of-network policies, and enrollee rights in plain language. These provisions may address some of the problems that insured adults in California have experienced with their coverage in the past. However, many of the services that people report needing coverage for—such as dental services—are not included in the EHB. Many newly-insured Californians may be surprised to learn that some ancillary services are not included in their plan, and education efforts will be needed to make sure people understand their coverage. In addition, some uninsured people who gain coverage may need help with plan selection, having not navigated the process before. Despite these possible challenges, most insured people—even those who reported difficulties—are overall satisfied with their coverage.

Report: Iii. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

How New Insurance Coverage Could Change How Californians Use Health Care

Uninsured adults in California generally do not seek or receive health care services at the same rate as insured adults, even when they have a need for care. Many uninsured adults have substantial health care needs that are not monitored by a physician. Cost is the main reason uninsured Californians do not receive care when needed, and many lack a regular provider to facilitate follow-up or ongoing care. When uninsured adults do receive care, they often have limited options. As coverage expands under the ACA, uninsured adults are likely to get care more frequently and establish relationships with providers. Patterns of care may shift, and providers may see an increase in patients who may have previously untreated or undiagnosed health care problems.

A large segment of the uninsured in California has little or no connection to the health care system.

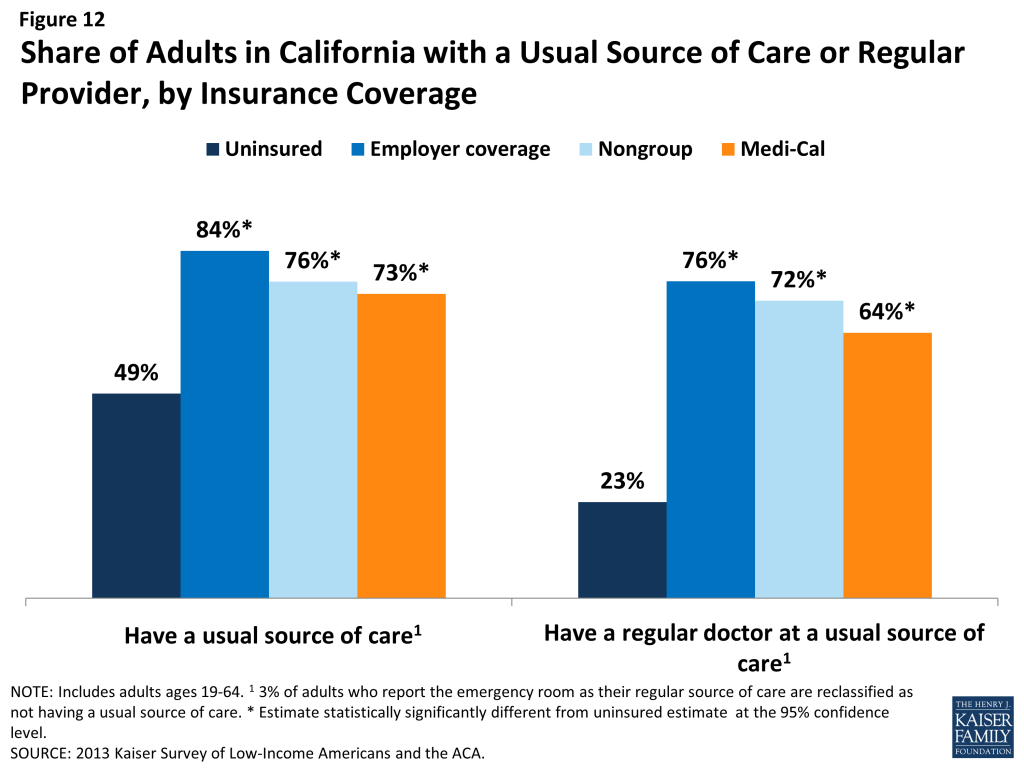

While some uninsured adults in California did report receiving health care services, most reported few connections to the health care system. Only about half of uninsured adults in California (49%) report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room). Having a usual source of care is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. In comparison, nearly all insured adults in California —84% of those with employer coverage, 76% of those with nongroup coverage, and 73% of those with Medi-Cal coverage— have a usual source of care (Figure 12). In addition, uninsured adults in California are less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care, with only about one-quarter (23%) of uninsured adults reported having a regular doctor, about one third the rate of insured adults. Notably, low-income uninsured adults in California are the least likely to have a usual source of care or a regular physician (Table 3).

| Table 3: Share of Adults in California with Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medi-Cal | |||

| Has a usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 49% | 84%* | 76%* | 73%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| ≤138% FPL | 50% | 64%* | — | 74%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 50% | 81%* | 76%* | 71%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 89% | 76% | — | |

| Has a regular provider at usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 23% | 76% | 72% | 64% | |

| By Income | |||||

| ≤138% FPL | 21% | 47%* | — | 65%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 25% | 75%* | 69% | 61%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 82% | 73% | — | |

| NOTES: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or unweighted cell sizes below 30 are not provided.^ 3% of adults who report the emergency room as their regular source of care are reclassified as not having a usual source of care. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.*Estimate is statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level.SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||

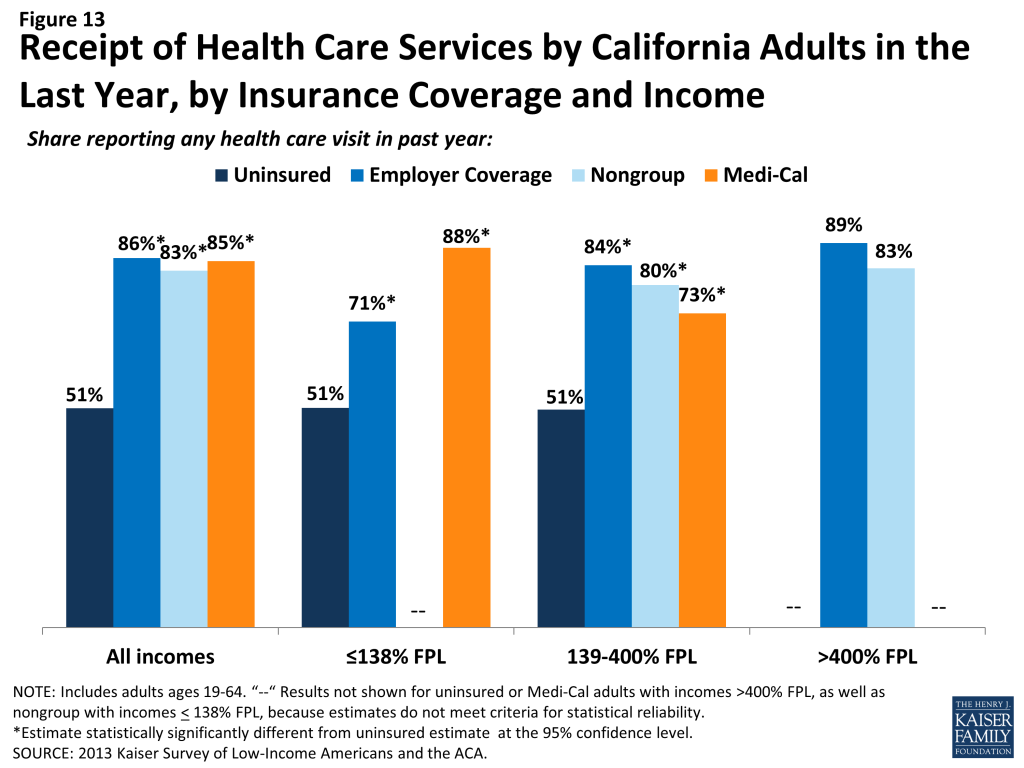

This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults in California to go without care. Nearly half of uninsured adults in California (49%) reported no health care visits—including hospital visits, doctor’s office or clinic visits, mental health services, or trips to the emergency room— in the past year, compared to 15% of Medi-Cal beneficiaries and 14% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 13). This pattern holds across all income groups. Of particular concern is the lack of preventive visits among uninsured Californians. One third (33%) of uninsured adults reported a preventive visit with a physician in the last year, compared to 75% of adults with employer coverage and 62% of adults with Medi-Cal (data not shown).