The Uninsured at the Starting Line: Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA

Executive Summary

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect. These provisions include the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces where low and moderate income families can receive premium tax credits to purchase coverage and, in states that opted to expand their Medicaid programs, the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to almost all adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). The ACA has the potential to reach many of the 47 million Americans who lack insurance coverage, as well as millions of insured people who face financial strain or coverage limits related to health insurance.

Though implementation is underway and people are already enrolling in coverage, policymakers continue to need information to inform coverage expansions. Data on the population targeted for coverage expansions can help policymakers target early efforts, provide insight into some of the challenges that are arising in the first months of new coverage, and evaluate the ACA’s longer-term effects. The Kaiser Family Foundation has launched a new series of comprehensive surveys of the low and moderate income population to provide data on these groups’ experience with health coverage, current patterns of care, and family situation. This report, based on the baseline 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, provides a snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults across the income spectrum at the starting line of ACA implementation. The report also examines how findings from the baseline survey can help policymakers understand and address early challenges in implementing health reform. Detailed information on the survey design, sample, and analysis can be found in the Methods section at the end of the full report.

Background

Prior to implementation of the ACA, over 47 million Americans—nearly 18% of the population—were without health insurance coverage. Because publicly-financed coverage has been expanded to most low-income children and Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly, the vast majority of uninsured people are nonelderly adults.1 The main barrier that people have faced in obtaining health insurance coverage is cost: health coverage is expensive, and few people can afford to buy it on their own. While most Americans traditionally obtain health insurance coverage as a fringe benefit through an employer, not all workers are offered employer coverage, and not all adults are working. Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) cover many low-income children, but eligibility for parents and adults without dependent children is limited, leaving many adults without affordable coverage.

These barriers to coverage are reflected in the characteristics of the uninsured population. Uninsured adults are more likely to be low-income than people with private health insurance, while adults with Medicaid coverage are particularly low-income (reflecting very low pre-ACA eligibility limits). Corresponding to their lower incomes, uninsured adults are less likely than privately insured adults to be in a working family; however, the majority of uninsured adults are in a family with either a full- or part-time worker. Uninsured adults also differ from insured adults with regards to other demographic characteristics, often reflecting association with income or work status. For example, they are more likely to be younger than insured adults, as younger adults have lower incomes and looser ties to employment than older adults. There also are significant racial and ethnic differences in health coverage among nonelderly adults, primarily reflecting differences in income by race/ethnicity.

I. Patterns of Coverage and the Need for Assistance

Examining patterns of coverage and the reasons the uninsured lack coverage can inform both outreach avenues and potential barriers to outreach and enrollment. Key survey findings on access to coverage include:

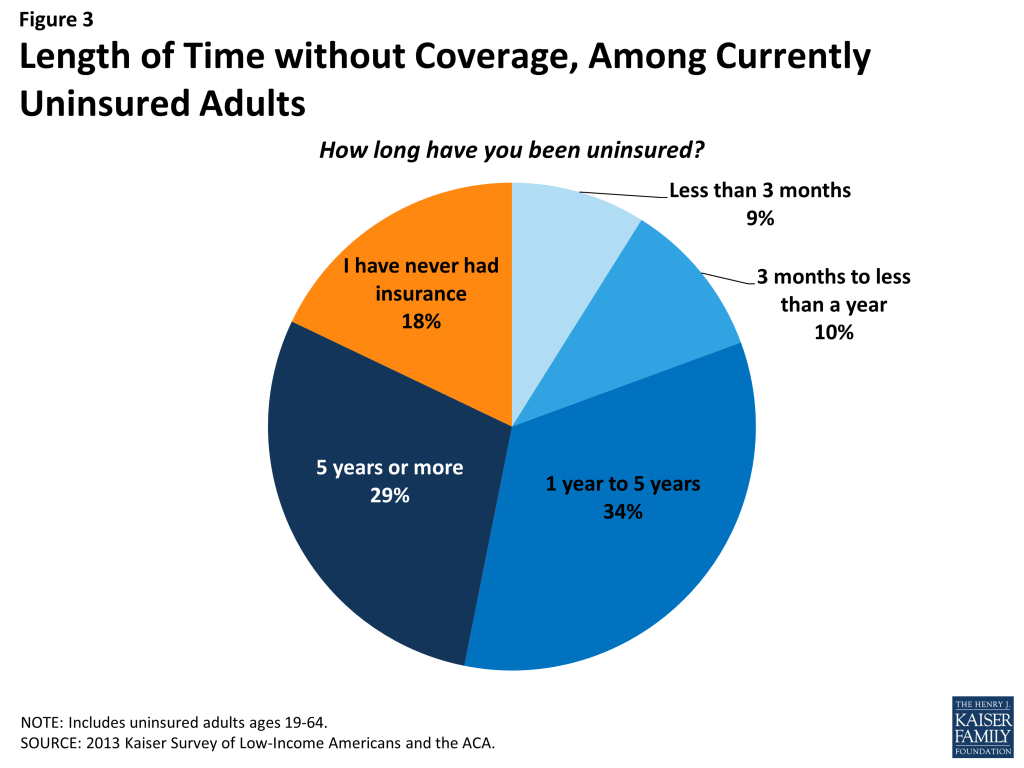

For most currently uninsured adults, lack of coverage is a long-term issue. While some people experience short spells of uninsurance due to job changes, income fluctuations, or renewal issues, for most uninsured adults, lack of coverage is a chronic issue. The survey shows that almost half (47%) of uninsured report being uninsured for 5 years or more, and 18% report that they have never had coverage in their lifetime.

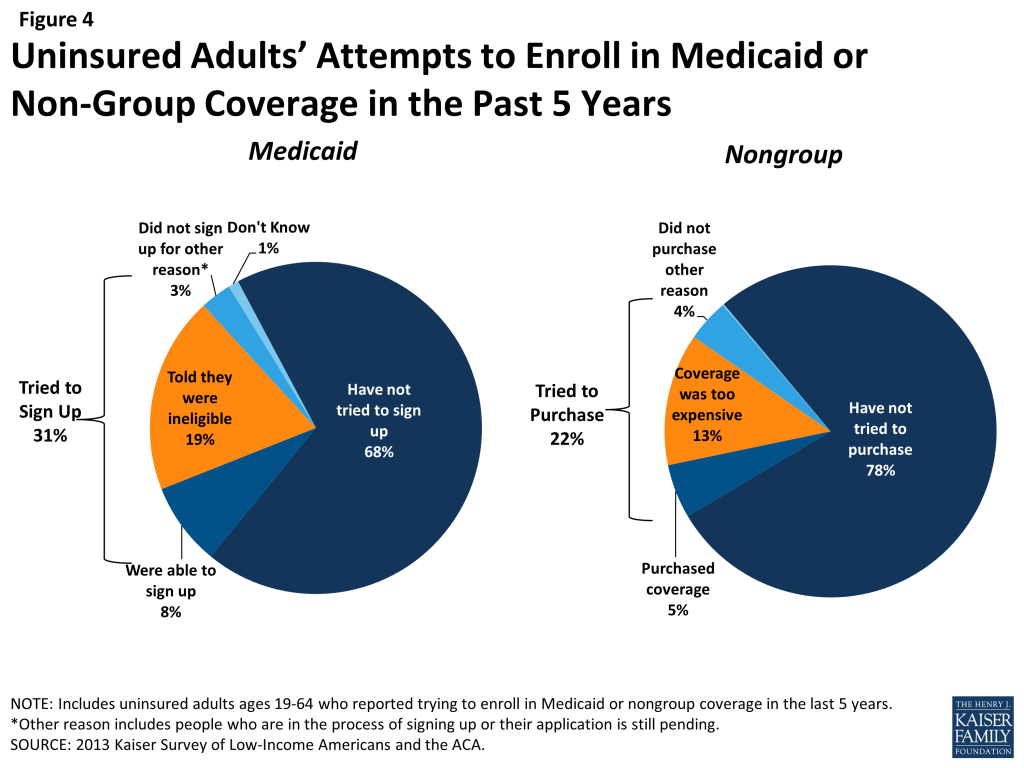

Many uninsured adults report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage. Prior to the ACA, the uninsured reported difficulty gaining insurance coverage due to the high cost of coverage and limits on Medicaid eligibility for adults. Eight in ten uninsured adults report no access to employer insurance, and the majority of people who had access to coverage through an employer report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable. One in three uninsured adults (31%) reported trying to sign up for Medicaid in the past five years, and the majority of them were unsuccessful because they were told they were ineligible. And one in five uninsured adults (22%) reported trying to obtain non-group coverage in the past five years, with most not purchasing a plan because the policy they were offered was too expensive.

Health insurance coverage is not always stable. For most insured adults, coverage is continuous throughout the year and over time, but a sizable number have a gap or change in coverage. When accounting for both insured people with a gap in their coverage and uninsured people who recently lost coverage, the survey indicates that nearly 18 million adults lose or gain coverage over the course of a year. In addition to those who lose or gain coverage over the course of a year, 17 million continuously insured adults have a change in their health insurance plan. The most common reasons for a change in coverage appear to be related to employment. Last, a small number of insured adults report challenges in either renewing or keeping their coverage, another indication of instability in coverage throughout the year.

Informing ACA Implementation: Many of the barriers to coverage that the uninsured report facing in the past are addressed by the ACA’s provisions to expand Medicaid and provide premium tax credits for Marketplace coverage. However, some uninsured adults may continue to face barriers to coverage, as not all employers are required to offer coverage and not all states are expanding their Medicaid programs. People targeted by the ACA have varying levels of experience with the insurance system. A large share of uninsured adults has been outside the insurance system for quite some time, and the long-term uninsured may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate their new health insurance. In addition, people who have attempted to obtain coverage in the past may be unaware that rules and costs have changed under the ACA; outreach and education will be needed to inform people that eligibility rules have changed and that financial assistance is available to offset the cost of coverage.

Survey findings on changes in insurance coverage over the course of the year indicate that, even after implementation, adults are likely to experience coverage changes due to job changes or income fluctuation. While there has been much focus on the early effort to enroll currently uninsured people in coverage, these findings demonstrate that implementation is not a “one shot” effort that will be done once people are enrolled in the early part of 2014 but rather will require a continuous effort to enroll and keep people in coverage.

II. What to Look for in Enrolling in New Coverage

While many currently uninsured adults have limited experience in signing up for and using health coverage, the past successes and challenges of insured low-and moderate income adults can inform the experiences of those seeking coverage under the ACA. Key survey findings related to plan enrollment and plan choice are:

Most adults did not report problems in applying for and enrolling in Medicaid coverage prior to the ACA, but some encountered difficulties in the process of gaining public coverage in the past. Adults who currently have Medicaid or who have attempted to enroll in the past five years report little difficulty in taking steps to enroll in Medicaid, with half saying the entire process was very or somewhat easy. However, the rest found at least one aspect of the process – finding out how to apply, filling out the application, assembling the required paperwork, or submitting the application – to be somewhat or very difficult.

In choosing their Medicaid or private insurance plan, adults do not always prioritize costs, and many find some aspect of the plan choice process to be a challenge. Adults choose health plans for various reasons, with 32% reporting that they chose their plan because it covered a wide range of benefits or a specific benefit that they need, 29% because their costs would be low, and 22% because the plan had a broad selection of providers or included their doctor. In choosing a plan, people may face challenges in comparing costs, services, and provider networks, as these factors typically varied greatly across plans in the past. In general, insured adults report that they did not have difficulty in comparing their plan choices, but 36% found some aspect of plan choice—comparing services, comparing costs, and comparing providers— to be difficult.

Overall, insured adults report satisfaction with their current coverage but also report gaps in covered services and problems when using their coverage. Most (85%) insured adults rate their pre-ACA coverage as excellent or good, but they also report gaps in services that are covered by their current insurance. One in six (17%) insured adults report needing a service that is not covered by their current plan, typically ancillary services such as dental, vision care, and chiropractor services. Many insured adults reported experiencing a problem with their current insurance plan covering a specific benefit, either because they were denied coverage for a service they thought was covered (25%) or their out-of-pocket costs for a service were higher than they expected (37%).

Informing ACA Implementation. The ACA includes provisions to simplify the Medicaid application and enrollment process for coverage in all states, regardless of whether they are expanding their Medicaid program. The ACA also requires plans in the Marketplace to provide detailed, standardized plan information for people to compare coverage options. Uninsured adults applying for coverage after these new processes are implemented should encounter fewer challenges in navigating enrollment and plan choice than applicants have in the past. However, in evaluating the success of plan enrollment, it is important to bear in mind historical challenges people have faced in comparing and selecting insurance coverage. It is also important to remember that people place utility on a range of factors related to insurance, including scope of services and provider networks. Assessments of whether people are choosing the optimal plan for themselves and their family will need to consider the multiple priorities that people balance in plan selection. Last, while the ACA aims to ensure coverage of at least a basic set of essential health benefits (EHB), many of the ancillary services that people report needing coverage for—such as dental services—are not included in the EHB. Newly-insured people may be surprised to learn that some ancillary services are not included in their plan, and education efforts will be needed to make sure people understand their coverage.

III. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

As uninsured adults gain coverage, there are likely to be changes in how often they seek care, what type of care they seek, and where they seek care. By comparing their current interactions with the health care system to their insured counterparts, the survey can provide insight into likely changes. Key findings in this area include:

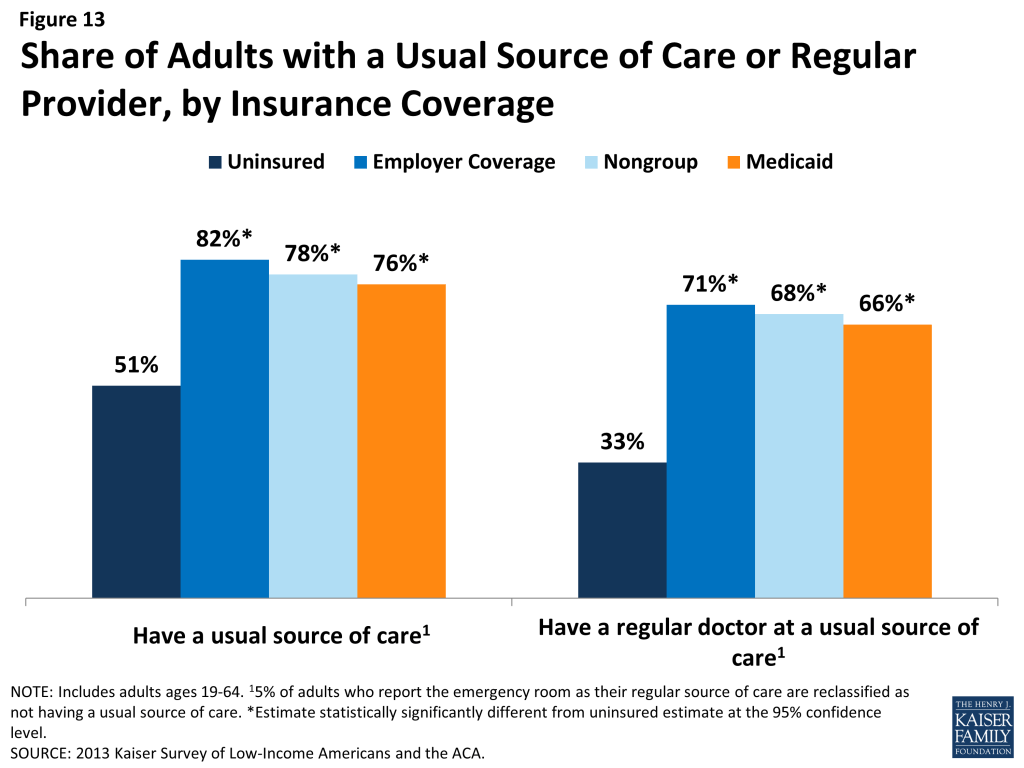

A large segment of the uninsured has little or no connection to the health care system. Most uninsured adults report few connections to the health care system. Only 51% of uninsured adults report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health, and only 33% of uninsured adults have a regular doctor, half the rate of insured adults. This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults to go without care. More than four in ten uninsured adults (41%) reported no health care visits in the past year, compared to 10% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 13% of adults with employer coverage.

A substantial share of the uninsured has health needs, many of which are unmet or only met with difficulty. Despite being as likely as those with private insurance to report having an ongoing health condition, uninsured adults are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care. When uninsured individuals do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority who use services do not. Almost half (49%) of the uninsured report needing but postponing care compared to 28% of adults with employer coverage, 36% with nongroup coverage, and 41% of Medicaid beneficiaries. The most common reason for postponing care among the uninsured is cost, as the uninsured must pay the full cost of their care.

Many of the uninsured report limited options for receiving health care when they need it. Uninsured adults are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician office when they do get care. Uninsured adults are more likely than other adults to report that they have limited options for their usual source of care, with 18% of uninsured people reporting that they chose their usual source of care because it is the only option available to them, compared to 10% of adults with Medicaid and 4% with employer coverage.

Informing ACA Implementation: The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage. Thus, gaining coverage is likely to connect many currently uninsured adults to the health care system. Given the health profile of the currently uninsured population, there is likely to be some pent-up demand for health care services among the newly-covered. However, outreach may be needed to link the newly-insured to a regular provider and help them establish a pattern of regular preventive care. In particular, some individuals who have relied on emergency rooms or urgent care centers as their usual source of care may require help in establishing new patterns of care and navigating the primary care system. While the uninsured may have more options for where to receive their care once they obtain coverage under the ACA, clinics and hospitals that already see a large share of uninsured adults may play an important role in serving this population once they gain insurance. Last, while coverage gains may reduce cost barriers to coverage, it will be important to monitor whether other barriers to care among the low-income population—such as transportation or wait times for appointments—continue to pose a challenge for access.

IV. Health Coverage and Financial Security

In addition to facilitating access to health care, health insurance serves primarily to protect people from high, unexpected medical costs. However, for low-income families, health costs can still be a burden, even if they have insurance. Understanding these issues can help policymakers monitor ongoing financial barriers to health services.

Health care costs pose a challenge for low- and moderate-income families, even if they have insurance coverage. Even among those with insurance, health care costs can be a burden, particularly for low- and moderate-income adults. About a third low- and moderate-income adults covered by employer coverage report that their share is somewhat hard or very hard for them to afford, and 76% of the low-income and 58% of moderate income adults with nongroup coverage report such difficulty. Health care costs translate to medical debt for many l0w-income adults, and these medical bills can cause serious financial strain. Among those who reported a problem with medical bills, the vast majority in every coverage and income category reported that medical bills caused them to either use up all or most of their savings, have difficulty paying for necessities, borrow money, or be contacted by a collection agency. Notable shares of low-income insured adults also report that they lack confidence in their ability to afford health care, given their current finances and health insurance situation. Of particular note is the finding that about half of adults with nongroup coverage do not feel confident that they could afford costs related to a major illness given their coverage and financial situation.

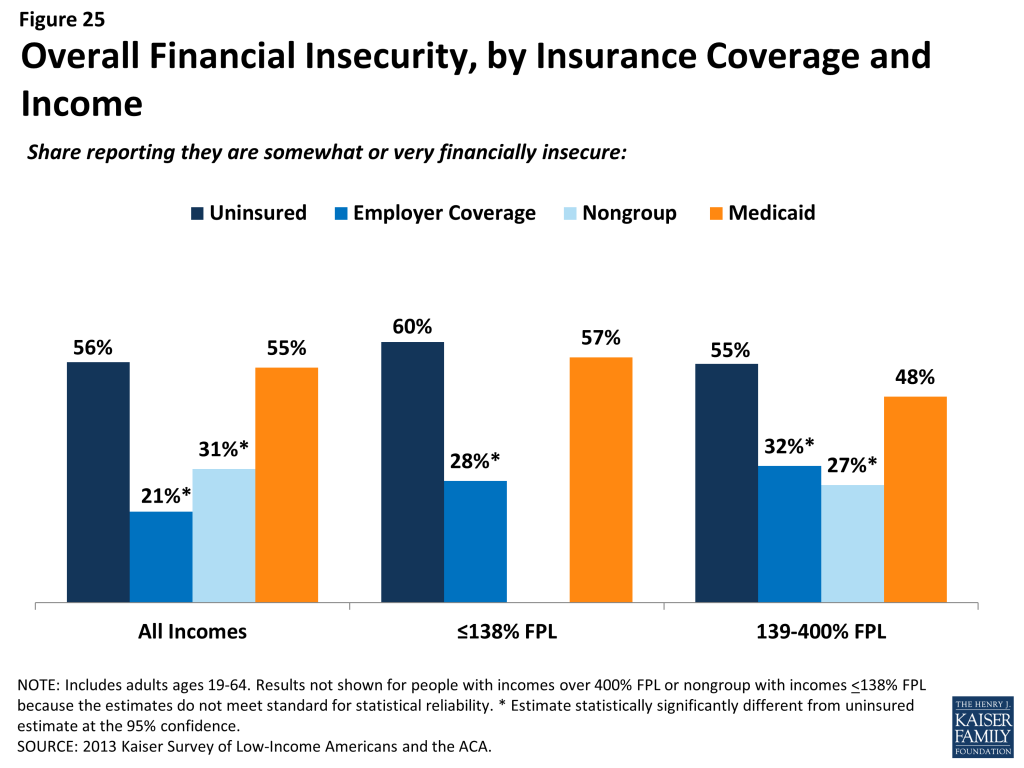

Low-income families face fragile financial circumstances. Low- and moderate-income adults across coverage groups report not being financially secure. However, adults who are low-income and uninsured or covered by Medicaid are particularly vulnerable to financial insecurity even outside of health care. General financial insecurity translates to concrete financial difficulties in making ends meet. Uninsured adults and those on Medicaid are more likely than privately-insured adults to have difficulty paying for other necessities such as food, housing, or utilities, with 58% reporting such difficulty compared to 19% of those with employer coverage and a quarter of those with nongroup coverage. While low-income adults across the coverage spectrum report high rates of difficulty paying for necessities, those with employer coverage report the lowest rates in this income group. These individuals may have the stronger or more stable ties to employment than their counterparts with other or no insurance coverage.

Informing ACA Implementation: Both insured and uninsured low-income adults struggle with medical bills and debt, and coverage expansions, assistance with premium costs, and limits on out-of-pocket costs under the ACA have the potential to ameliorate the financial issues associated with the cost of health care. However, given survey findings that many low-income insured people continue to face financial challenges related to health care, it will be important to track whether there are ongoing financial barriers as people enroll in coverage and seek care. While insurance coverage can provide financial protection in the event of illness or injury, it is not curative of all of the financial burdens faced by low-income families. Given their overall situation, health insurance alone may not lift low-income people out of poverty, and many low-income adults may continue to face financial challenges even after gaining coverage.

V. Low- and Moderate-income Uninsured Adults’ Readiness for the ACA

As outreach and enrollment efforts are underway, information on low- and moderate-income adults’ access to tools for signing up and connections to outreach avenues can be helpful in addressing barriers. Key survey findings in this area include:

A majority of uninsured adults who are income eligible for coverage expansions reported knowing little or nothing about Medicaid and Marketplace programs prior to the start of open enrollment. Despite ongoing media attention to the ACA, seven in ten uninsured adults with incomes in the Medicaid target range (<138% FPL) said they knew nothing at all or only a little about their state’s Medicaid program, and eight in ten uninsured adults in the income range for Marketplace subsidies (139-400% FPL) reported that they knew nothing at all or only a little about the Marketplaces. More recent polling data indicates that lack of knowledge remains high despite recent media attention to the ACA.

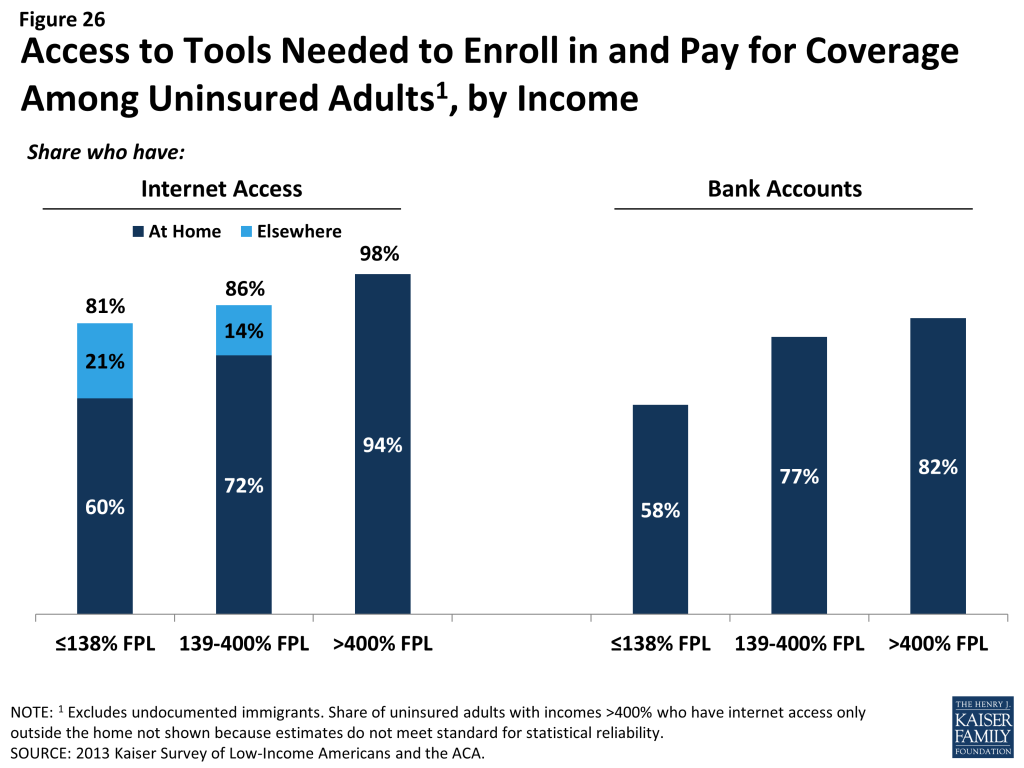

While most uninsured adults have the necessary tools for enrolling in coverage, some will experience additional logistical issues in signing up. Under the ACA, internet access is an important tool in accessing coverage. While the majority of uninsured adults have access to the internet either at home or outside the home, 19% of low-income (<138% FPL) and 14% of moderate income (139-400% FPL) uninsured adults report that they do not have internet access readily available. For Marketplace coverage, people will require a means to pay their premiums on a regular basis. While plans must accept various forms of payment, direct withdrawal from a checking account is a simple and reliable way to ensure that premiums are paid on time. However, nearly a quarter (23%) of uninsured adults in the income range for Marketplace subsidies report that they do not have a checking or savings account.

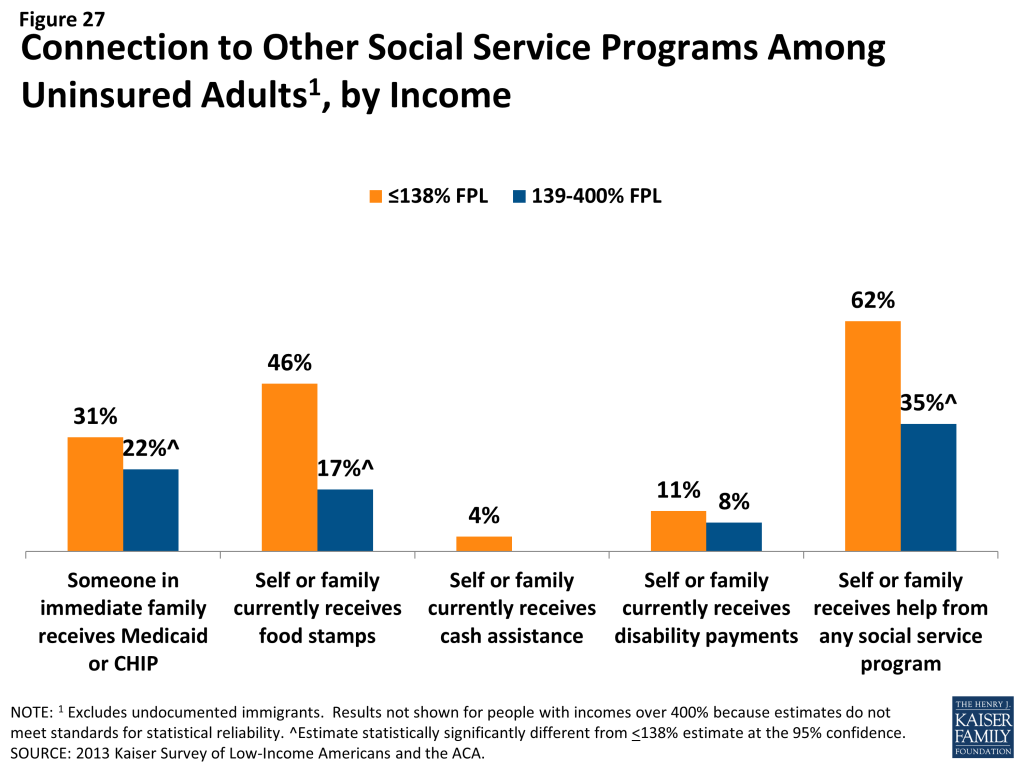

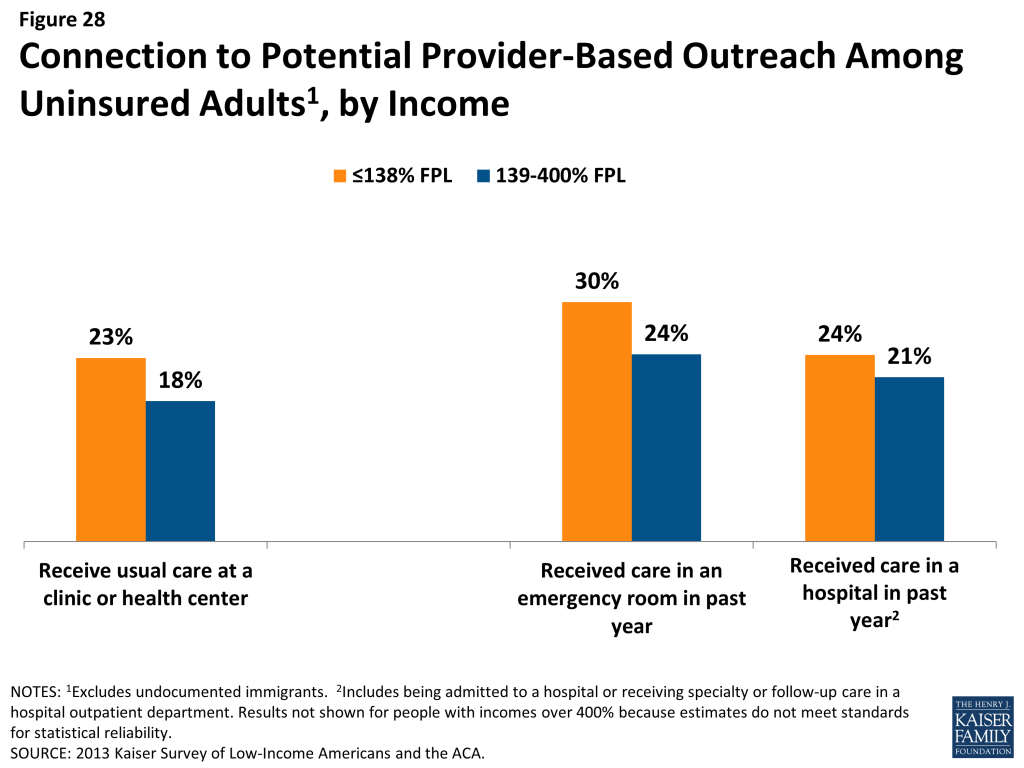

Many uninsured adults could be reached through targeted outreach avenues. Among uninsured adults with incomes in the range for Medicaid eligibility (<138% FPL), over six in ten (62%) report that they or someone in their immediate family receives either SNAP, cash assistance, disability payments, or Medicaid or CHIP, making “fast track” enrollment efforts through using information collected by other agencies a promising avenue for outreach. For those without a connection to social services agencies, outreach through providers may be a promising approach, as about one in five low- or moderate-income uninsured adults report that they use a clinic or health center as their usual source of care. While fewer report using a hospital outpatient department for regular care, hospitals reach many uninsured adults through periodic visits.

Informing ACA Implementation: Both survey findings and more recent polling data indicate that there is a great need for education of new coverage options among people targeted for expansions. Even once eligible individuals learn about coverage options, they may face logistical challenges in signing up. People without internet access via a computer may be able to enroll through other more traditional avenues such as over the phone or in person at county offices or providers, but efforts may be needed to inform people of these other application routes, and some using them may experience slower enrollment process than they would if they applied online. Finally, “fast track” enrollment efforts are a promising approach to facilitating enrollment, but broader efforts will also be needed to reach the eligible uninsured population.

Report: Introduction

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect. These provisions include the creation of new Health Insurance Marketplaces where low and moderate income families can receive premium tax credits to purchase coverage and, in states that opted to expand their Medicaid programs, the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to almost all adults with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($15,856 for an individual or $26,951 for family of three in 2013). With these coverage provisions, ACA has the potential to reach many of the 47 million Americans who lack insurance coverage, as well as millions of insured people who face financial strain or coverage limits related to health care.

Though ACA implementation is underway and people are already enrolling in coverage, policymakers continue to need information to inform coverage expansions. Reports of difficulties in enrolling in coverage, continued confusion and lack of information about the law point to challenges in the early stages of implementation. In the future, data will be needed to assess whether and how the ACA is helping low- and moderate-income families gain affordable coverage, access needed care, and obtain financial security. Detailed data on the population targeted for coverage expansions’ experience with health coverage, current patterns of care, and family situation can help policymakers target early efforts, provide insight into some of the challenges that are arising in the first months of new coverage, and evaluate the ACA’s longer-term affects.

To that end, the Kaiser Family Foundation has launched a new series of comprehensive surveys of the low and moderate income population. This report, based on the baseline 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, provides a snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults across the income spectrum at the starting line of ACA implementation. It also provides a baseline for future assessment of the impact of the ACA on health coverage, access, and financial security of low- and moderate-income individuals nationwide. Future reports using this baseline survey will provide additional in-depth analysis of issues in ACA implementation, such as differences between states expanding their Medicaid programs and those not expanding; in-depth analysis of issues in affordability of health care and family finances; Medicaid’s role in facilitating access to care; and challenges facing part-time workers, among others. Forthcoming separate state reports focusing on California, Missouri, and Texas will analyze these issues in the context of state-specific efforts to implement the law.

This report examines how findings from the baseline survey can help policymakers understand and address early challenges in implementing health reform. Throughout sections that focus on findings related to i) patterns of insurance coverage, ii) the process of selecting and enrolling in health coverage, iii) interactions with the health care system, iv) financial security, and v) readiness for ACA coverage expansions, the report highlights findings that can inform outreach and enrollment workers, health plans, and providers and health systems. A detailed explanation of the methods underlying the survey and analysis is available in the Methods section of the report.

Report: Background: The Challenge Of Gaining Insurance Coverage Prior To The Aca

Prior to implementation of the ACA, over 47 million Americans—nearly 18% of the population—were without health insurance coverage. Because publicly-financed coverage has been expanded to most low-income children and Medicare covers nearly all of the elderly, the vast majority of uninsured people are nonelderly adults.2 Not having health insurance has well-documented adverse effects on people’s use of health care, health status, and mortality, as the uninsured are more likely to delay or forgo needed care leading to more severe health problems.3 Lack of insurance coverage also has implications for people’s personal finances, providers’ revenue streams, and system-wide financing.4 ,5 ,6 The coverage provisions in the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to address these issues by making coverage more available and affordable, particularly for people with low or moderate incomes.

The main barrier that people have faced in obtaining health insurance coverage is cost: health coverage is expensive, and few people can afford to buy it on their own. While most Americans traditionally obtain health insurance coverage as a fringe benefit through an employer, not all workers are offered employer coverage, and not all adults are working. Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) cover many low-income children, but eligibility for parents and adults without dependent children is limited, leaving many adults without affordable coverage.

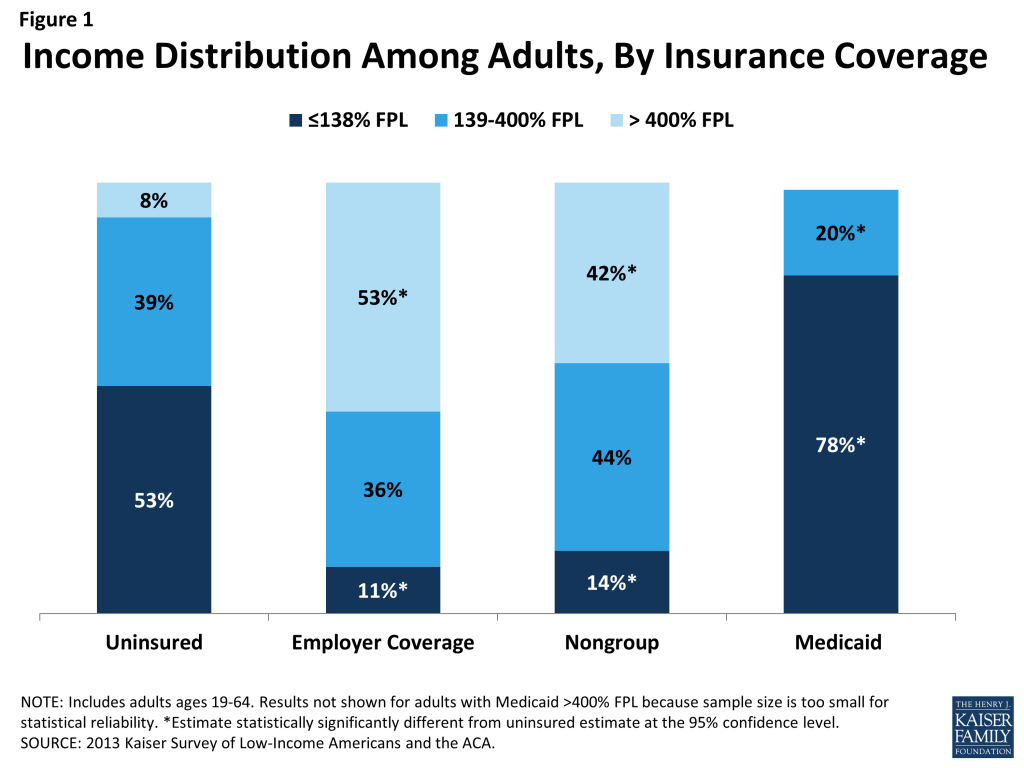

These barriers to coverage are reflected in the characteristics of the uninsured population. Compared to those with private coverage, uninsured adults are more likely to be low-income (Figure 1). A majority of uninsured adults (53%) are low-income, or have incomes at or below 138% FPL, in contrast to 11% of adults with employer coverage and 14% of adults with nongroup. Adults with Medicaid are the most likely of any coverage group to be low-income, reflecting the fact that prior to the ACA, adult income eligibility limits were generally very low (often below half the poverty level). Less than one in ten uninsured adults have incomes greater than 400% FPL, compared to over half of adults with employer coverage (53%) and 42% of adults with nongroup coverage.

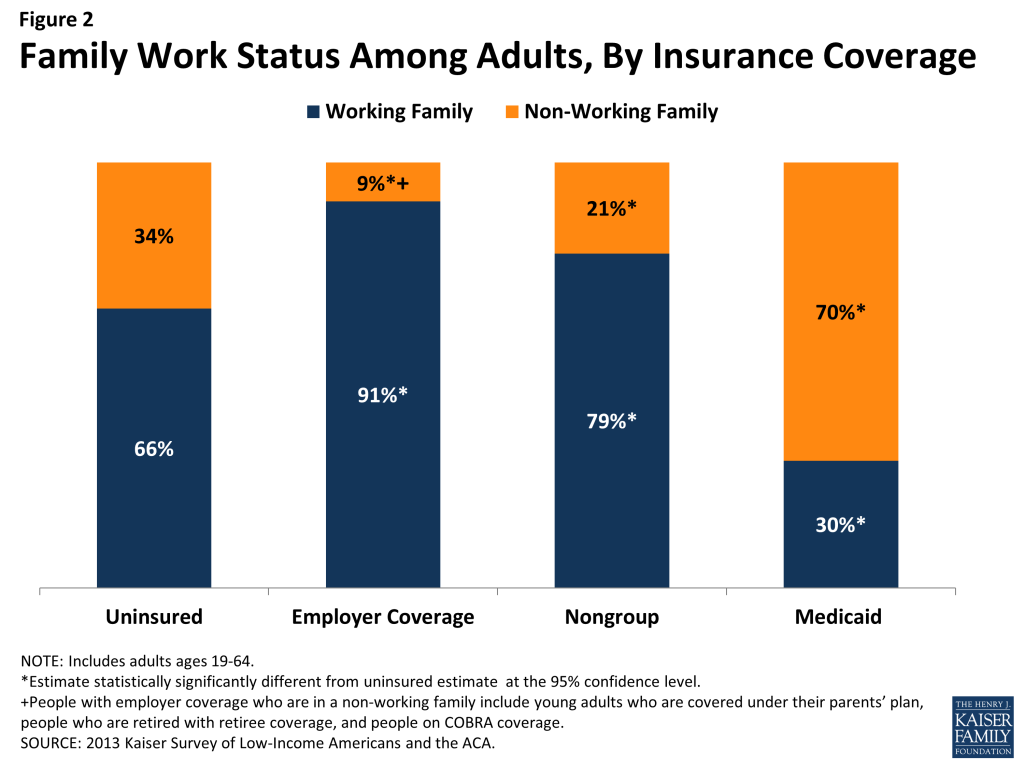

Corresponding to their lower incomes, uninsured adults are less likely than privately insured adults to be in a working family; however, the majority of uninsured adults are in a family with either a full- or part-time worker. About two-thirds (66%) of uninsured adults are in a working family (that is, either they, or their spouse if they are married, report working either full or part-time), in contrast to 91% of adults with employer coverage and 79% of adults with nongroup coverage (Figure 2). Adults with Medicaid are the least likely to be in a working family (30%), again reflecting very low income eligibility limits for adults prior to the ACA.

Uninsured adults also differ from insured adults with regards to other demographic characteristics. Uninsured adults are likely to be younger than insured adults, as younger adults have lower incomes and looser ties to employment than older adults. Two-thirds (67%) of uninsured adults are ages 19-44 as compared to 56% of adults with employer coverage or Medicaid and 41% of adults with nongroup coverage (Appendix Table A1).

There also are significant racial and ethnic differences in health coverage among nonelderly adults. For example, uninsured adults are more likely to be Hispanic – 30% of uninsured adults are Hispanic – than adults with employer coverage (11%), nongroup coverage (9%), or Medicaid (18%). About half (49%) of uninsured adults are White, non-Hispanic, compared to 75% of adults with nongroup coverage, and 70% of adults with employer sponsored insurance. Racial and ethnic differences in coverage rates, which are reflective of differences in income and work status by race/ethnicity, have implications for efforts to address health care disparities. Also, about one in five uninsured adults is a noncitizen (19%), compared to less than 7% of adults with Medicaid or employer coverage. Citizenship status may leave many uninsured adults ineligible for Medicaid, increasing the likelihood they will remain uninsured.

Among the primary goals of the ACA were filling in gaps in the availability of public coverage by expanding Medicaid eligibility for low-income adults and making private coverage more affordable for moderate-income adults who lack access to coverage through a job. The ACA also aims to simplify and coordinate eligibility and enrollment across programs, ensure coverage for a basic package of health benefits, and facilitate innovations in service delivery. As policymakers embark on early implementation of the law, it is important to remember who the ACA aims to help and how their characteristics may inform efforts to reach them.

Report: I. Patterns Of Coverage And The Need For Assistance

Coverage Dynamics among the Insured and Uninsured

Health insurance coverage is dynamic, and every year millions of Americans gain, lose, or change their health coverage. However, for most uninsured adults, lack of coverage is a long-term issue that spans many years. Many uninsured adults report trying to obtain coverage in the past but were unsuccessful due to barriers such as ineligibility for public coverage or high costs of private coverage. Under the ACA, millions of uninsured are projected to gain coverage as those barriers are removed, but some may continue to experience gaps or changes in coverage.

For most currently uninsured adults, lack of coverage is a long-term issue.

While some people lack health insurance coverage during short periods of unemployment or job transitions, for many uninsured adults, lack of coverage is a chronic problem. The survey shows that a large share of uninsured adults have been without insurance for a very long period of time: Almost half (47%) report being uninsured for 5 years or more, and 18% report that they have never had coverage in their lifetime (Figure 3 and Appendix Table A2).

Perhaps not surprisingly, adults who have been without insurance coverage for at least five years are, on average, older than those who have been uninsured for shorter periods of time. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of adults who have been uninsured for five years or more are ages 35-64, compared to just 47% of adults who have been uninsured for less than a year (data not shown). However, on other characteristics, such as race, gender, citizenship, income, and health status, long-term and short-term uninsured adults resemble each other.

“I don’t know how to go about getting insurance.”

Alexa (TX), long-term uninsured

It is important for policymakers implementing coverage expansions to be aware that people targeted by the ACA have varying levels of experience with the insurance system. While some only recently lost coverage, a large share of uninsured adults has been outside the insurance system for quite some time. The long-term uninsured may require targeted outreach and education efforts to link them to the health care system and help them navigate their new health insurance.

Many uninsured adults report trying to obtain insurance coverage in the past, but most did not have access to affordable coverage.

The uninsured report a desire to obtain coverage, but prior to implementation of the ACA, options for coverage—particularly for the low-income—were limited. The vast majority of uninsured adults do not have access to employer coverage. Eight in ten uninsured adults report no access to employer insurance, either because no one in their family is working for an employer, their or their spouse’s employer does not offer coverage, or they are ineligible for that coverage (Table 1). For example, 47% of uninsured adults are in a family without an employer, meaning both they and their spouse (if married) are either not working or are working but are self-employed. A quarter of uninsured adults are in a family that has an employer who does not offer coverage to any workers, and 10% are in a family that works for an employer who offers coverage but they are ineligible for that coverage. Most are ineligible because they work part-time or are in a waiting period. Less than one in five (18%) uninsured adults does have access to coverage through an employer, but the majority of those people report that the coverage offered to them is not affordable.

| Table 1: Access to Employer Health Coverage Among Uninsured Adults | |||||

| All Uninsured | Uninsured by Income | ||||

| <138% FPL | 139-400% FPL | >400% FPL | |||

| % | % | % | % | ||

| No Access to ESI | 82% | 86% | 78%^ | 78% | |

| No one in family has an employer* | 47% | 54% | 37%^ | 51% | |

| Firm doesn’t offer coverage | 25% | 25% | 30% | — | |

| Not eligible for coverage | 10% | 7% | 12% | — | |

| Access to ESI | 18% | 14% | 22%^ | — | |

| Cannot afford premium | 11% | 8% | 12% | — | |

| Don’t think need coverage | — | — | — | — | |

| Some other reason | 6% | 5% | 9% | — | |

| Note: Don’t Know and Refused responses are not shown, they account for less than 3% of the uninsured population.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided.NA: Not applicable* Individuals who are self-employed without other employment are treated as not having an employer.^ Estimate statistically significantly different from <138% FPL estimate at the 95% confidence level.SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||

Prior to the ACA, Medicaid eligibility for adults was very limited in most states. Eligibility generally was limited to parents with very low incomes (often below about half the federal poverty level), and in all but a handful of states, adults without dependent children were ineligible for Medicaid regardless of their income.7 Further, application processes were sometimes very complex, requiring face-to-face interviews, assessments of assets, or paper documentation.8 Eligibility and application processes posed barriers for many low-income adults seeking Medicaid coverage.

One in three uninsured adults (31%) reported trying to sign up for Medicaid in the past five years (Figure 4). Low-income uninsured adults (those with family income up to 138% FPL) were more likely than those with moderate incomes to report trying to sign up for Medicaid (38%) (see Appendix Table A2). The majority of adults who tried to sign up for Medicaid (22% of the uninsured) were unsuccessful, and among those, most (19% of the uninsured) were unable to sign up because they were told they were ineligible. Notably, a quarter of uninsured adults in the income range for Medicaid expansion under the ACA (<138% FPL) have tried to sign up for Medicaid in the past but were told they were ineligible.

Prior to the ACA, there were also barriers to obtaining coverage on the non-group, or individual market. This type of coverage was not guaranteed in all states, and insurance companies could often charge higher premiums for sicker individuals or place limits on coverage for pre-existing conditions, making coverage unaffordable for many uninsured adults. The uninsured also report trying to obtain non-group coverage prior to the ACA. One in five uninsured adults (22%) reported trying to obtain non-group coverage in the past five years. Most of these adults (13% of the uninsured) did not purchase a plan because the policy they were offered was too expensive (Figure 4).

“We are very lucky that we have not had any catastrophic incidents, because we could not afford the catastrophic insurance premiums [for nongroup coverage] that we were quoted.”

Jose (FL), on trying to buy coverage on his own before the ACA

Many of the barriers to coverage that the uninsured report facing in the past are addressed by the ACA. Large employers (>50 workers) face penalties if they do not offer affordable coverage to their workers, and in states that chose to expand Medicaid, eligibility for Medicaid includes almost all adults with incomes at or below 138% FPL. Further, millions of uninsured families are now able to purchase coverage in the Marketplaces and receive premium tax credits to reduce the cost. Insurers are no longer able to deny coverage based on health status and are limited in what they charge people based on age, location, and tobacco use status. However, some uninsured adults may continue to face barriers to coverage. Employers are not required to offer coverage to part-time employees, and only large businesses will be subject to a fine for not offering affordable coverage to full-time employees, beginning in 2015. In states that did not expand Medicaid, eligibility remains limited, leaving many ineligible for Medicaid and without an affordable coverage option. Last, people who have attempted to obtain coverage in the past may be unaware that rules and costs have changed under the ACA. Outreach and education will be needed to inform people that eligibility rules have changed and that financial assistance is available to offset the cost of coverage.

Health insurance coverage is not always stable.

For most insured adults, coverage is continuous throughout the year and over time, but a sizable number experience a gap or change in coverage. When accounting for both insured people with a gap in their coverage and uninsured people who recently lost coverage, the survey indicates that nearly 18 million adults lose or gain coverage over the course of a year.

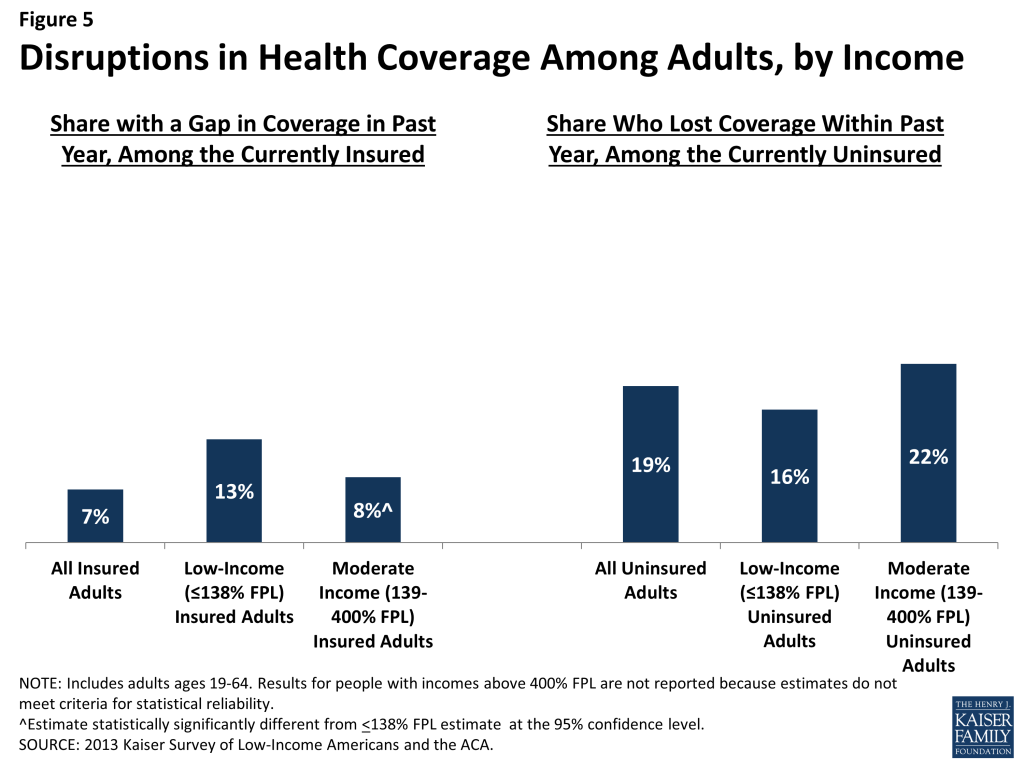

Among adults who were insured at the time of the survey, 7% reported being uninsured at some point in the past year (see Figure 5 and Table 2), and those who had a gap in coverage were uninsured for nearly half the year (5.7 months) on average (data not shown). Low-income insured adults (those with family income up to 138% FPL) are particularly vulnerable to gaps in coverage, with 13% reporting a coverage gap in the past 12 months compared to 8% of those with incomes between 139 and 400% FPL (Figure 5).

Further, some currently uninsured adults had coverage at some point within the past year. Among uninsured adults, nearly one in five (19%) report having lost coverage within the last year. Among both those with a gap in coverage or who recently lost coverage, the majority report that they most recently had employer coverage (data not shown).

| Table 2: Coverage Dynamics among Insured and Uninsured Adults, by Income and Current Coverage | |||||||||

| All | By Income | By Current Coverage | |||||||

| <138% FPL | 139-400% FPL | >400% FPL | Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | ||||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |||

| Insured Adults | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Gap in Coverage in Past Year | 7% | 13% | 8%^ | — | 5%* | — | 13% | ||

| Changed Coverage During Year | 12% | 7% | 11%^ | 16%^ | 14%* | — | 3% | ||

| Same Coverage for Full Year | 81% | 79% | 81% | 82% | 80% | 84% | 81% | ||

| Uninsured Adults | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Uninsured Full Year | 80% | 83% | 78% | 75% | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Lost Coverage Within Past Year | 19% | 16% | 22% | — | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided.NA: Not applicable.^ Estimate statistically significantly different from <138% FPL estimate at the 95% confidence level.* Estimate statistically significantly different from Medicaid estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||||||

In addition to those who lose or gain coverage over the course of a year, millions of adults who have coverage throughout the entire year have a change in their health insurance plan. Among adults with insurance coverage, 12% (17 million people) had coverage for the entire year but report that they had a change in their coverage (Table 2). Coverage changes may be due to a number of different factors including changes in employment, changes in eligibility for public programs, or simply a change in insurance carrier. The most common reasons for a change in coverage appear to be related to employment, as most people with a coverage change report changing from an employer plan to another employer plan.

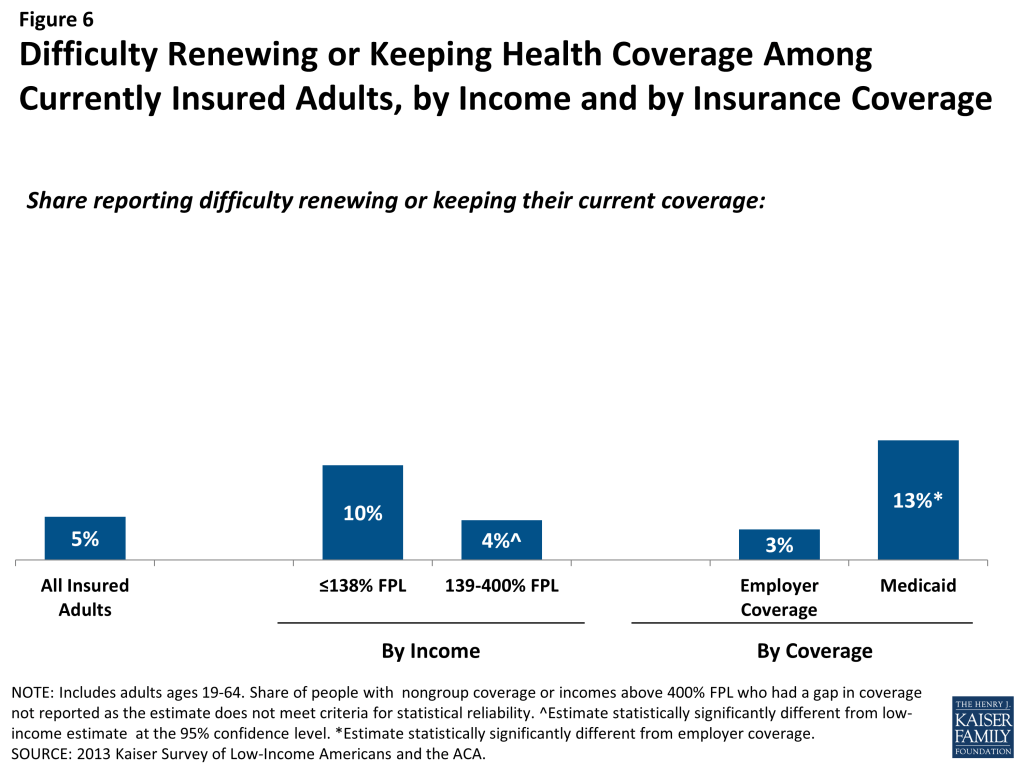

Last, a small number of insured adults report challenges in either renewing or keeping their coverage, another indication of instability in coverage throughout the year. Reflecting eligibility rules and sometimes burdensome renewal processes, adults with Medicaid are the most likely to report a challenge (13%) compared to adults with employer coverage (Figure 6). Medicaid eligibility is closely tied to income, and adults’ income may fluctuate throughout the year; in addition, adults must renew their Medicaid coverage annually.

“So there for a while, for a few weeks, a month, 6 weeks, I’m without insurance. And then during that time, I cannot get medical care.”

Julie (MO), on having gaps in coverage

The survey findings on changes in insurance coverage over the course of the year have implications for implementation of health reform. Prior to the ACA, many people lost and gained employer coverage over the course of a year, due to changing economic conditions and the delicate relationship between employment and health insurance. Further, there was some churning in insurance coverage resulting from Medicaid income eligibility limits: as adults’ income fluctuates, they may gain or lose Medicaid eligibility. Adults also experienced gaps in Medicaid coverage due to frequent renewal requirements. Gaps in coverage can cause people to postpone or forgo health care or accumulate medical bills.9 By providing for insurance options across the income spectrum and facilitating coverage outside the employment-based system, the ACA may help adults have coverage continuously throughout the year. However, even after implementation, adults are likely to experience coverage changes due to job changes or income fluctuation. While there has been much focus on the early effort to enroll currently uninsured people in coverage, these findings demonstrate that people will continue to move around within the insurance system throughout the year. Thus, implementation is not a “one shot” effort that will be done once people are enrolled in the early part of 2014 but rather will require a continuous effort to enroll and keep people in coverage.

Report: Ii. What To Look For In Enrolling In New Coverage

How Low and Moderate Income Adults Sign Up For and View Their Coverage

While many currently uninsured adults have limited experience in signing up for and using health coverage, the past successes and challenges of insured low-and moderate income adults can inform the experiences of those seeking coverage under the ACA. A majority of insured adults do not experience problems in choosing, enrolling in, and using their coverage, and this pattern holds true for both people with Medicaid and private insurance. Still, based on the experience of their insured counterparts, the uninsured population targeted by the ACA coverage expansions is likely to encounter some barriers in the process of choosing and enrolling in coverage. While the ACA aims to make the process smoother, it is likely that some challenges inherent in the complexity of health coverage will require concerted efforts to address.

Most adults did not report problems in applying for and enrolling in Medicaid coverage prior to the ACA, but some encountered difficulties in the process of gaining public coverage in the past.

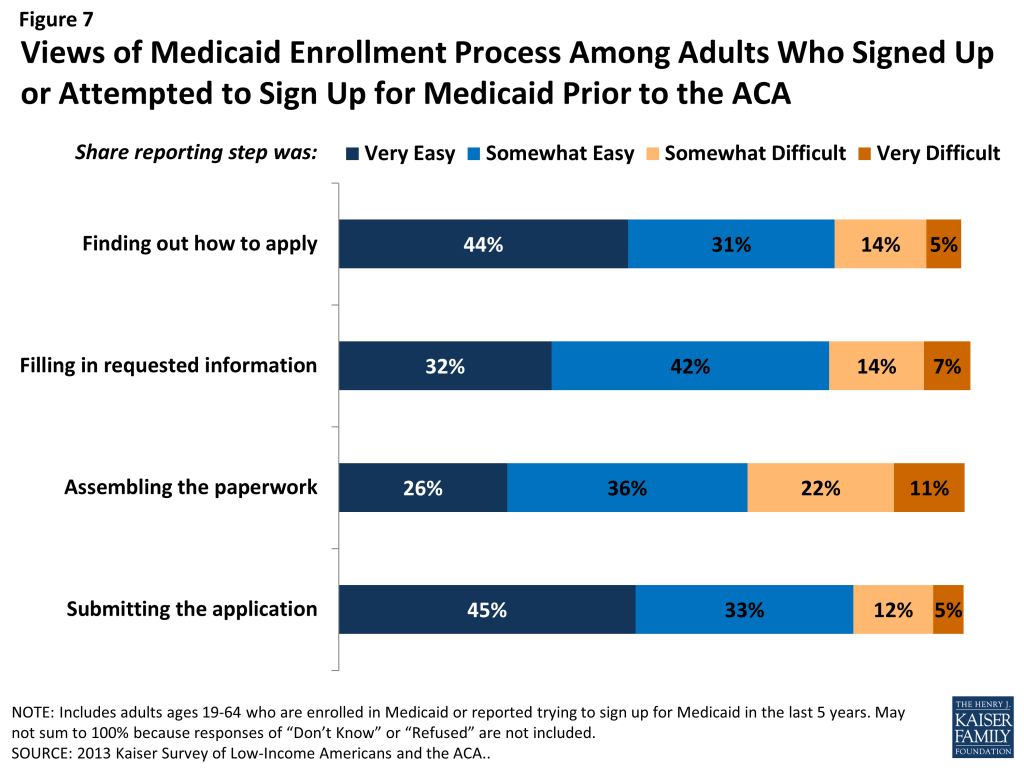

In comparison to the process for gaining coverage through an employer—which is typically facilitated by the firm or a representative and may require limited action on the part of the insured—applying for publicly-financed coverage typically requires proactive steps to gain coverage. Adults who currently have Medicaid or who have attempted to enroll in the past five years report little difficulty in taking steps to enroll in Medicaid. Half of adults (50%) who applied to Medicaid said the entire process was very or somewhat easy. However, the rest found at least one aspect of the process – finding out how to apply, filling out the application, assembling the required paperwork, or submitting the application – to be somewhat or very difficult. The most commonly reported difficulty was assembling the required paperwork, which a third (33%) of people who enrolled or applied said was a somewhat or very difficult (Figure 7 and Appendix Table A3).

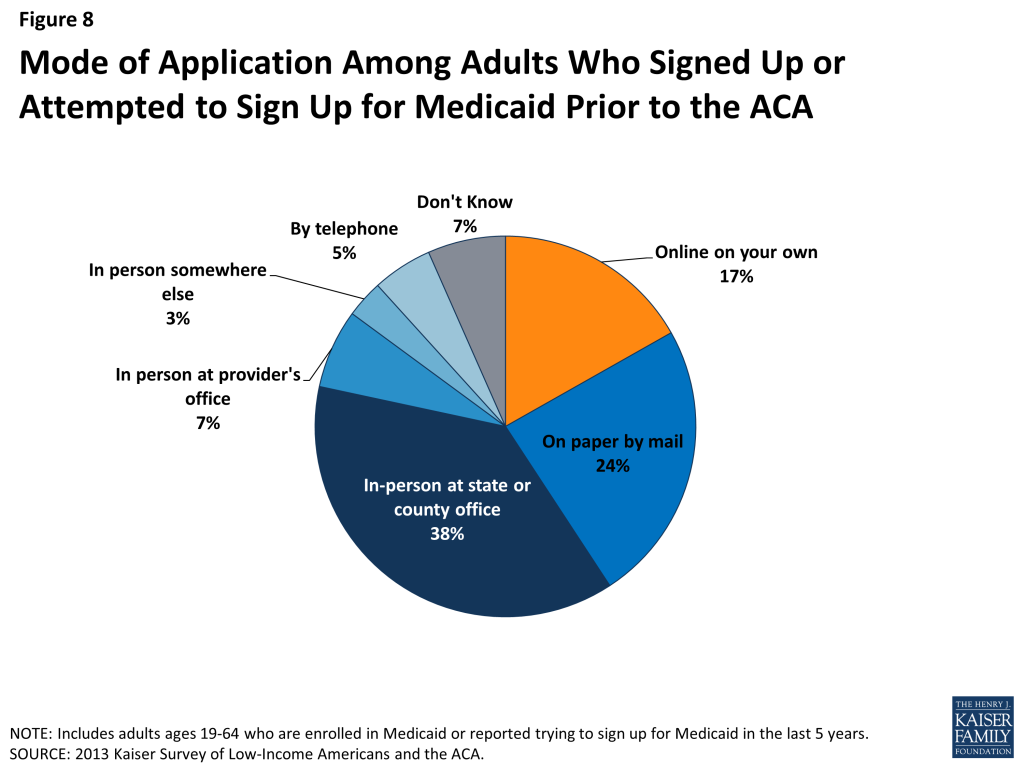

Historically, the Medicaid application process often required in-person visits to state or county welfare offices and completion of paper-based applications. In recent years, most states have made strides towards developing web-based applications to facilitate access to coverage and ease administrative burdens.10 However, a plurality (38%) of people who have applied to Medicaid in the past five years report that they did so through traditional routes—that is, in person at a state or county government office—and only 17% reported using an online application (Figure 8).

The ACA includes provisions to simplify the application and enrollment process for coverage in all states, regardless of whether they are expanding their Medicaid program. For example, the ACA establishes new requirements for simplifying the Medicaid application, coordinating enrollment across programs, and moving toward paperless verification of eligibility. These requirements include state adoption of a single streamlined application that is available online, by phone, and on paper and that screens for all health coverage options; electronic transfers of accounts between agencies to facilitate coordination across health coverage programs; and reliance on trusted sources of electronic data rather than requesting paper documentation to verify eligibility criteria.11 Further, under the ACA, assisters are available in each state to help individuals and families enroll in coverage. Thus, uninsured adults applying for coverage should encounter fewer challenges in navigating the enrollment process than applicants have in the past. However, in states that do not expand their Medicaid programs, few adults applying for coverage are likely to be eligible, given very low income eligibility limits in those states. As a result, the primary barrier of lack of eligibility will remain.

In choosing their Medicaid or private insurance plan, adults do not always prioritize costs, and many find some aspect of the plan choice process to be a challenge.

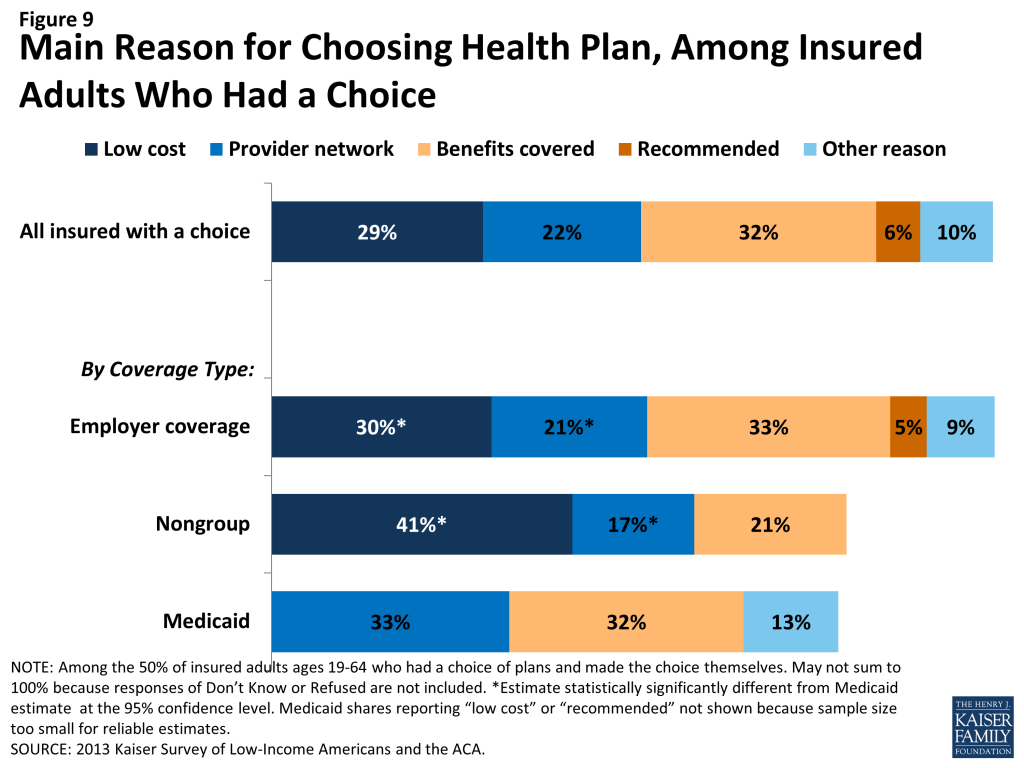

As people gain coverage, many will have the option to select an insurance plan. People may chose a particular plan for a variety of reasons, including low cost, choice of providers, recommendations from friends and family, or coverage of a particular benefit. Among the 50% of insured adults who chose a health plan,[endnote 101630-5] 32% reported that they chose their plan because it covered a wide range of benefits or a specific benefit that they need, while 29% reported that they chose their plan because their costs would be low and 22% because the plan had a broad selection of providers or included their doctor (Figure 9). This pattern differs by coverage type (see Appendix Table A4). For example, among Medicaid beneficiaries who had a plan choice, 33% reported provider network as the main reason for plan choice compared to 17% of adults with non-group coverage and 21% with employer coverage. These findings may reflect the fact that Medicaid benefits and costs are largely standardized across plans, while networks may vary.

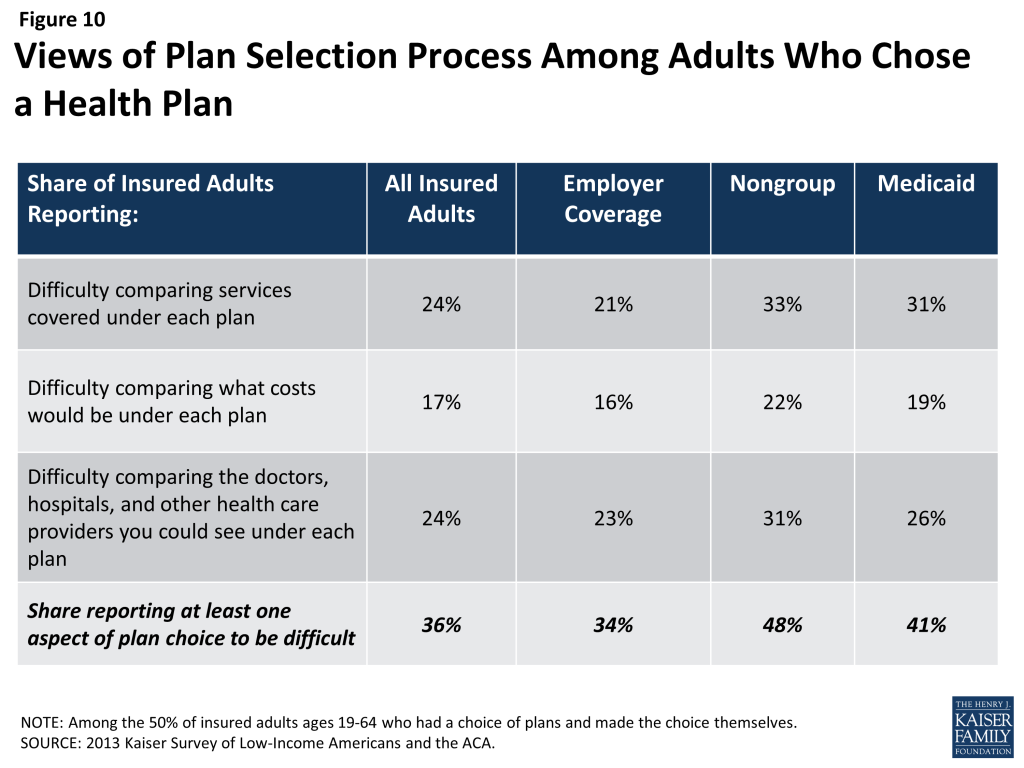

In choosing a plan, people may face challenges in comparing costs, services, and provider networks, as these factors typically varied greatly across plans in the past. In general, insured adults report that they did not have difficulty in comparing their plan choices, but 36% found some aspect of plan choice—comparing services, comparing costs, and comparing providers— to be difficult (Figure 10 and Appendix Table A4). Insured adults were least likely to report difficulty comparing costs across plans (17%). This finding is particularly interesting as most people reported choosing their plan based on covered services or benefits as compared to costs. As enrollment numbers for particular plans are released and policymakers begin to assess plan choice among new enrollees, these findings can inform evaluations of plan choice under the ACA. Contrary to expectations that people may opt for the lowest cost plan,12 survey findings indicate that people place value on a range of factors related to insurance, including scope of services and provider networks. Thus, assessments of whether people are choosing the optimal plan for themselves and their families will need to consider the multiple priorities that people balance in plan selection. Further, while ACA provisions requiring plans in the Marketplace to provide a standard set of benefits as well as more detailed information on what is included in plans could potentially increase the ease of plan selection, it is important to bear in mind historical challenges people have faced in comparing and selecting insurance coverage. In particular, low-income adults who receive Medicaid may require assistance in navigating plan choices, as provisions requiring comparable information on plans for coverage in the Marketplaces do not apply to Medicaid. However, states can make such information available to Medicaid enrollees as part of an effort to improve the plan selection process.

Overall, insured adults report satisfaction with their current coverage but also report gaps in covered services and problems when using their coverage.

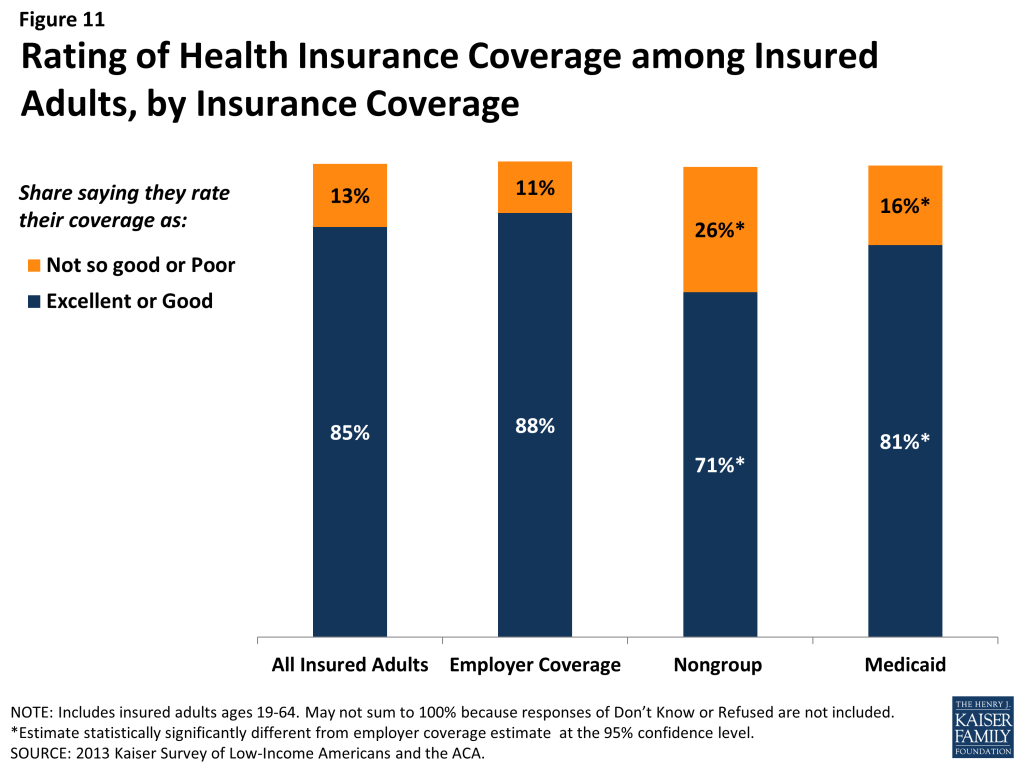

Most insured adults report high levels of satisfaction with their current coverage, but they also report gaps in services that are covered by their current insurance. Nearly 85% of insured adults rate their coverage as excellent or good, while 13% rate their coverage as not so good or poor (Figure 11). Adults with employer coverage gave their plans the highest ratings, 88% grading their plans as excellent or good. Adults with nongroup coverage or Medicaid were less likely to give their plans high ratings, but a majority (71% and 81%, respectively) still rates their plans as excellent or good.

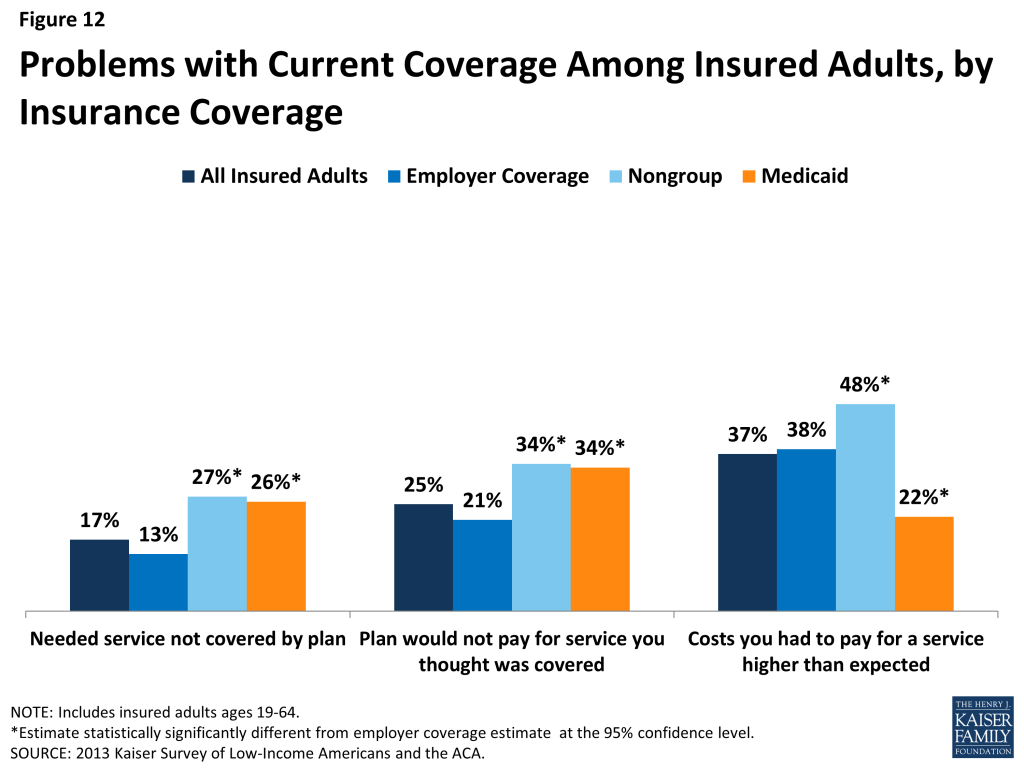

Despite the high ratings, notable shares of insured adults report a problem with their plan. Specifically, one in six (17%) insured adults report needing a service that is not covered by their current plan (Figure 12 and Appendix Table A5). People with Medicaid coverage (26%) or non-group coverage (27%) are more likely to report that their plan does not cover certain services compared to those with employer coverage (13%). The most frequently-reported services people say they need but lack coverage for are ancillary services such as dental, vision care, and chiropractor services. In private health coverage, these ancillary services are often covered under stand-alone private insurance policies that must be purchased separately from health coverage. In Medicaid, most are not federally-required benefits for adults but rather are covered at state option; while states must provide a broad spectrum of Medicaid benefits for children, they have more flexibility in designing benefits for adults. Lack of coverage for adult dental services in Medicaid—the most frequently reported service needed but excluded from coverage—has been a longstanding issue facing beneficiaries and providers, despite a particularly high need among the low-income population.13

Insured adults also report experiencing other problems with their insurance plan. Many insured adults reported experiencing a problem with their current insurance plan covering a specific benefit, either because they were denied coverage for a service they thought was covered (25%) or their out-of-pocket costs for a service were higher than they expected (37%). Some of these services may be over-the-counter products, which are excluded from the majority of insurance plans but which people believe their plan should cover. Reports of these difficulties varied by insurance coverage. Adults with Medicaid or with nongroup coverage (both 34%) were more likely than those with employer coverage (21%) to report they were surprised that their plan would not cover a service they believed was covered. However, adults with Medicaid (22%) were less likely to report facing higher costs than expected than privately insured adults (38% among those employer coverage and 48% among those with non-group). This pattern most likely reflects the nominal out of pocket costs Medicaid beneficiaries are required to pay compared to the high cost-sharing of many private plans.

Among the goals of the ACA are ensuring that the coverage people gain provides at least a basic level of coverage and that new ways of purchasing coverage via the Marketplaces make it easier for people to navigate the insurance system. Thus, new coverage must include a set of essential health benefits (EHB), and participating plans in the Marketplace must report information on claims payment policies, cost-sharing requirements, out-of-network policies, and enrollee rights in plain language. These provisions may address some of the problems that insured adults have experienced with their coverage in the past, but uninsured adults—particularly those with limited experience enrolling in coverage—may need more help with plan selection. Further, many of the services that people report needing coverage for—such as dental and vision services—are not included in the EHB. Many newly-insured people may be surprised to learn that some ancillary services are not included in their plan, and education efforts will be needed to make sure people understand their coverage. Despite these possible challenges, most insured people—even those who report difficulties—are satisfied with their coverage overall.

Report: Iii. Gaining Coverage, Getting Care

How New Insurance Coverage Could Change How People Use Health Care

Uninsured adults generally do not seek or receive health care services at the same rate as insured adults, even when they have a need for care. Many uninsured adults have substantial health care needs that are not monitored by a physician. Cost is the main reason the uninsured do not receive care when needed, and many lack a regular provider to facilitate follow-up or ongoing care. When uninsured adults do receive care, they often have limited options. As coverage expands under the ACA, uninsured adults are likely to get care more frequently and establish relationships with physicians. Patterns of care may shift, and providers may see an increase in patients who may have previously untreated or undiagnosed health care problems.

A large segment of the uninsured has little or no connection to the health care system.

While some uninsured adults do report receiving health care services, most uninsured adults report few connections to the health care system. Only about half of uninsured adults (51%) report that they have a usual source of care, or a place to go when sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room). Having a usual source of care is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. In comparison to the uninsured, most insured adults—82% of those with employer coverage, 78% of those with nongroup coverage, and 76% of those with Medicaid coverage— have a usual source of care (Figure 13). Uninsured adults also are less likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care – only 33% of uninsured adults have a regular doctor, half the rate of insured adults. Notably, low-income uninsured adults are the least likely to have a usual source of care or a regular physician (Table 3).

| Table 3: Share of Adults with Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | |||

| Has a usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 51% | 82%* | 78%* | 76%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 49% | 67%* | 73%* | 74%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 51% | 81%* | 69%* | 80%* | |

| >400% FPL | 67% | 85% | 89% | — | |

| Has a regular provider at usual source of care^ | |||||

| All | 33% | 71%* | 68%* | 66%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 27% | 56%* | 61%* | 64%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 36% | 70%* | 56%* | 71%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 74% | 84%* | — | |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided.^ 5% of adults who report the emergency room as their regular source of care are reclassified as not having a usual source of care.* Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level. SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||

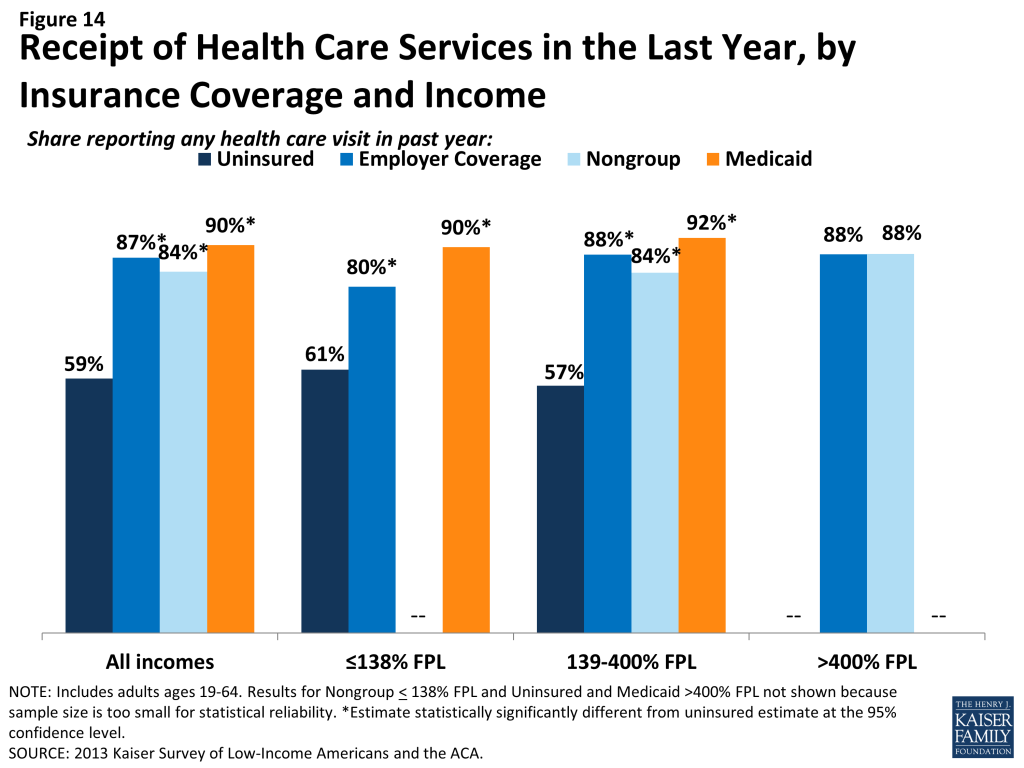

This lack of a connection to the health care system leads many uninsured adults to go without care. More than four in ten uninsured adults (41%) reported no health care visits (including hospital visits, doctors’ or clinic visits, mental health services, or trips to the emergency room) in the past year, compared to 10% of Medicaid beneficiaries and 13% of adults with employer coverage (Figure 14). This pattern holds across income groups. Of particular concern is the lack of preventive visits among the uninsured. Only 1 in 3 uninsured adults (33%) reported a preventive visit with a physician in the last year (data not shown), compared to 74% of adults with employer coverage and 67% of adults with Medicaid.

The survey findings reinforce conclusions based on prior research: having health insurance affects the way that people interact with the health care system, and people without insurance have poorer access to services than those with coverage.14 ,15 ,16 Thus, gaining coverage is likely to connect many currently uninsured adults to the health care system. However, outreach may be needed to link the newly-insured to a regular provider and help them establish a pattern of regular preventive care.

A substantial share of the uninsured has health needs, many of which are unmet or only met with difficulty.

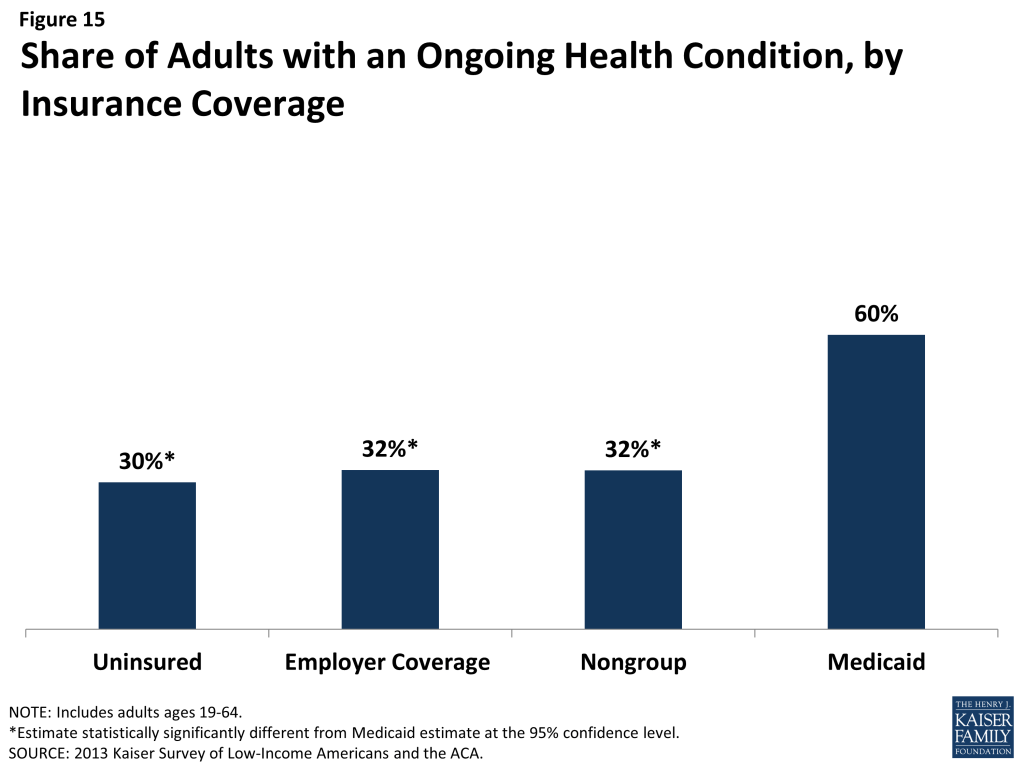

People who lack health insurance still have health care needs. In fact, uninsured adults in the survey were just as likely as those with private insurance to report having an ongoing health condition, with about 3 in 10 uninsured (30%) and privately insured adults (32% for both employer and nongroup coverage) reporting having an ongoing health condition (Figure 15). Given that the uninsured are more likely than people with coverage to have undiagnosed illness,17 actual rates of illness among the uninsured may be even higher. In contrast to those with private insurance, adults with Medicaid are twice as likely as uninsured adults to report having a health condition, with 60% of Medicaid beneficiaries reporting an ongoing health condition. This finding, which holds across income groups (Table 4) reflects Medicaid’s pre-ACA role in caring for people with substantial health needs (such as individuals with disabilities or people who become impoverished due to high health care expenses). As low-income uninsured gain coverage under reform, Medicaid’s role will expand to include a broader scope of the adult population.

| Table 4: Health Status of Adults by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | |||

| Fair or poor overall health | |||||

| All | 32% | 12%* | 14%* | 45%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 37% | 18%* | — | 47%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 29% | 14%* | — | 35% | |

| >400% FPL | — | 9%* | — | — | |

| Fair or poor mental health | |||||

| All | 18% | 6%* | — | 34%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 21% | 12%* | — | 33%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 18% | 9%* | — | 38%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | — | — | — | |

| Have an ongoing health condition that needs to be monitored regularly orneeds regular care | |||||

| All | 30% | 32% | 32% | 60%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 32% | 23%* | — | 63%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 29% | 30% | 33% | 50%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 36% | 27% | — | |

| Take prescription medication on regular basis^ | |||||

| All | 28% | 42%* | 45%* | 71%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 31% | 34% | — | 71%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 28% | 37%* | 43% | 74%* | |

| >400% FPL | — | 47% | 45% | — | |

| Notes: Don’t Know and Refused responses not shown. Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided.^ Excludes birth control.* Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level.Source: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||

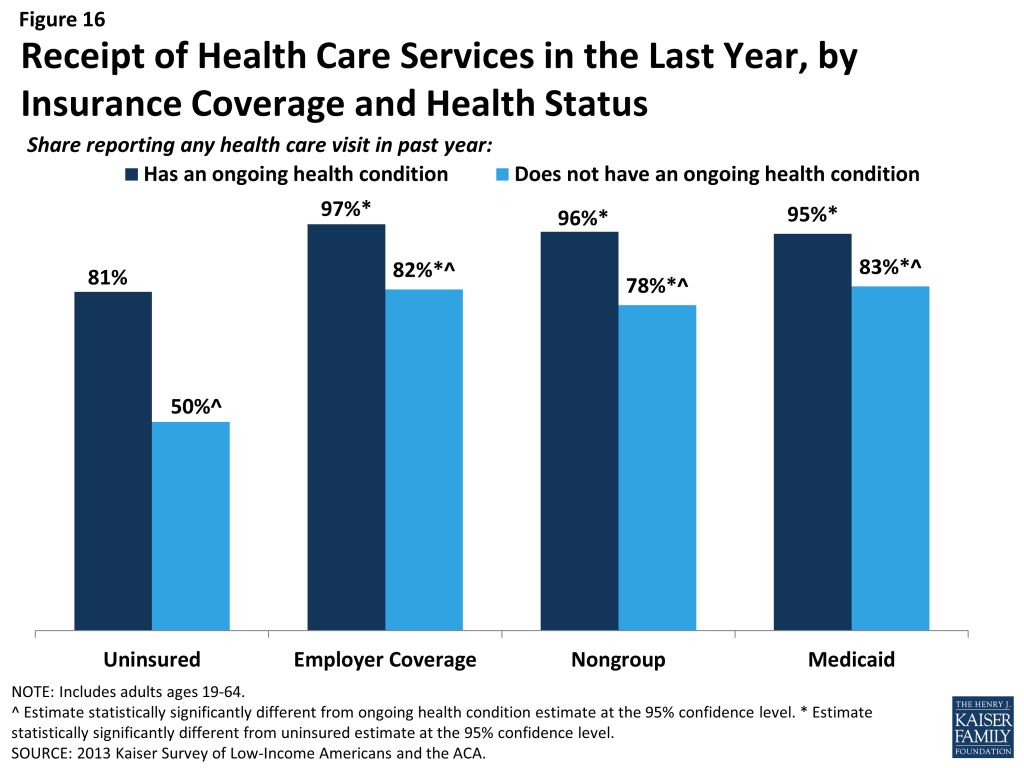

While uninsured individuals with an ongoing health condition are more likely than those without to report receiving services (Figure 16), they are still less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care. Half (50%) of uninsured adults without an ongoing health condition, received services in the past year compared to 81% of uninsured adults with a health condition. However, this rate is still lower than adults who have a health condition and have employer coverage, nongroup coverage, or Medicaid, nearly all of whom (97%, 96%, and 95%, respectively) received medical services over the course of the year.

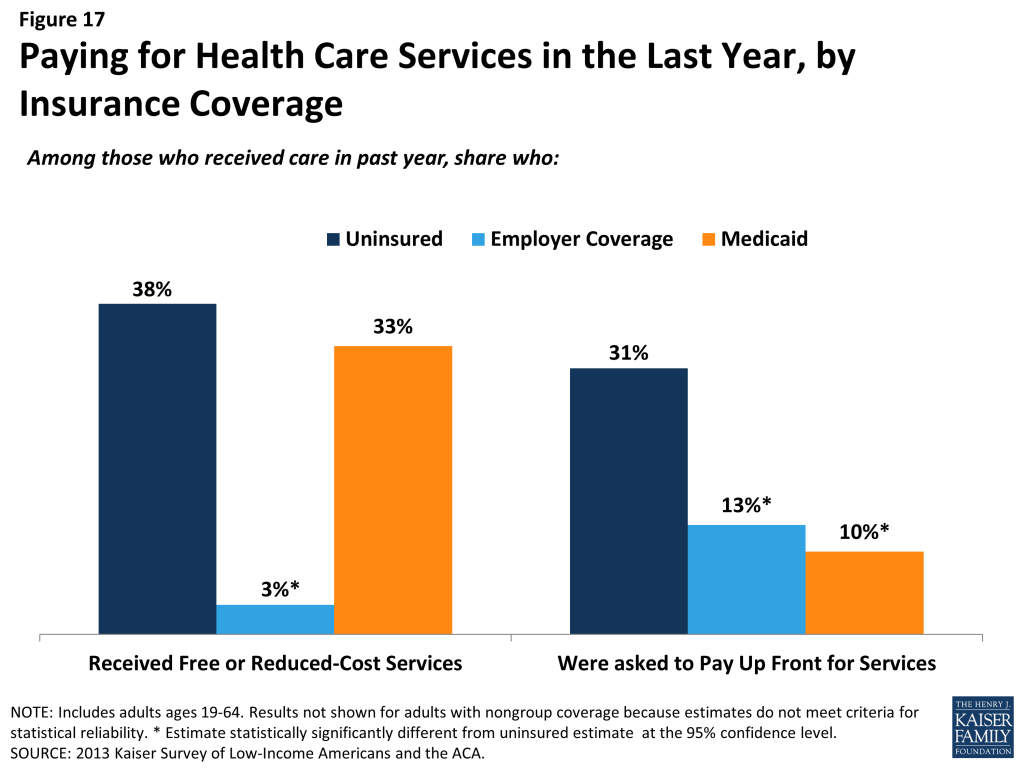

When uninsured individuals do receive care, they sometimes receive free or reduced-cost care, though the majority who use services do not. Among adults who reported that they received a health care service in the past year, 38% of uninsured adults report receiving free or reduced cost care, versus just 3% of those with employer coverage (Figure 17). Notably, about a third of adults with Medicaid who received services reported that they received free or reduced cost care. They may have done so during a period of uninsurance in the previous year or may associate the fact that they pay little or no costs when they see a provider as receiving “free or reduced cost” care. Uninsured adults who received care were much more likely than their insured counterparts to be asked to pay up front for care: nearly a third (31%) report being asked to pay for the full cost of medical care (not counting copayments) before they could see the doctor or provider, versus just 13% of those with employer coverage and 10% of adults with Medicaid. Again, insured adults may have experienced these issues during a period in the past year when they lacked coverage.

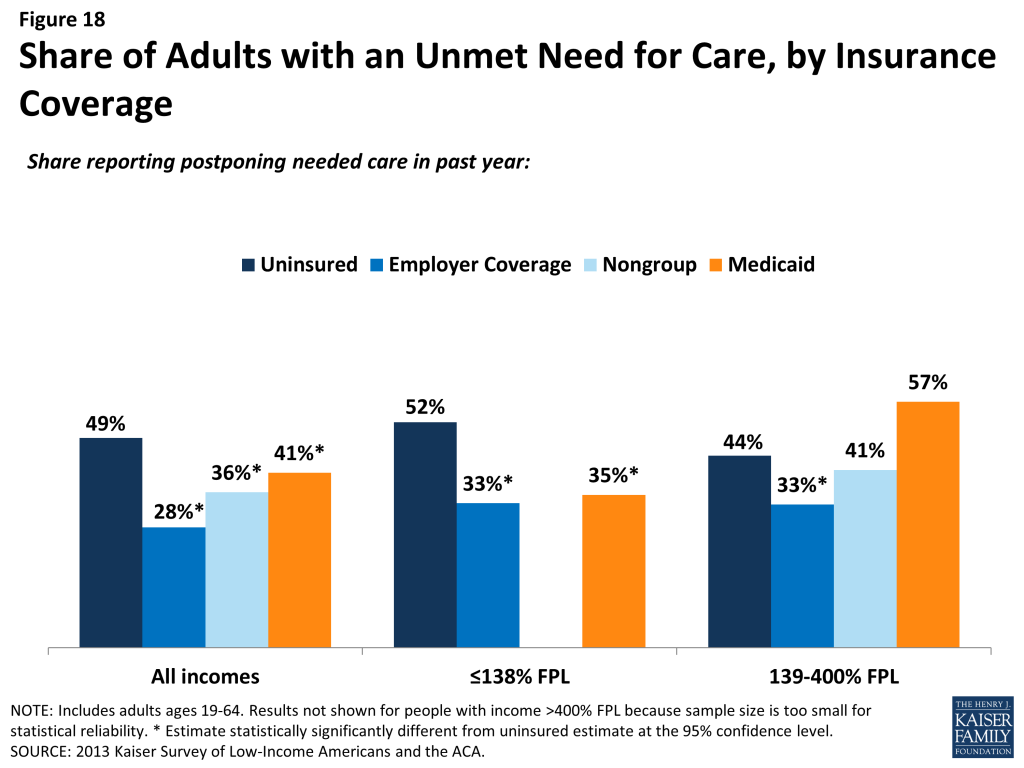

Despite some uninsured adults reporting that they receive free or reduced cost services, a larger share report an unmet need for care. Almost half (49%) of the uninsured report needing but postponing care compared to 28% of adults with employer coverage, 36% with nongroup coverage, and 41% of Medicaid beneficiaries (Figure 18). The relatively high rate among Medicaid beneficiaries reflects higher need: among Medicaid beneficiaries without a disability or ongoing health condition, rates of unmet need are similar to adults with other sources of coverage (data not shown).

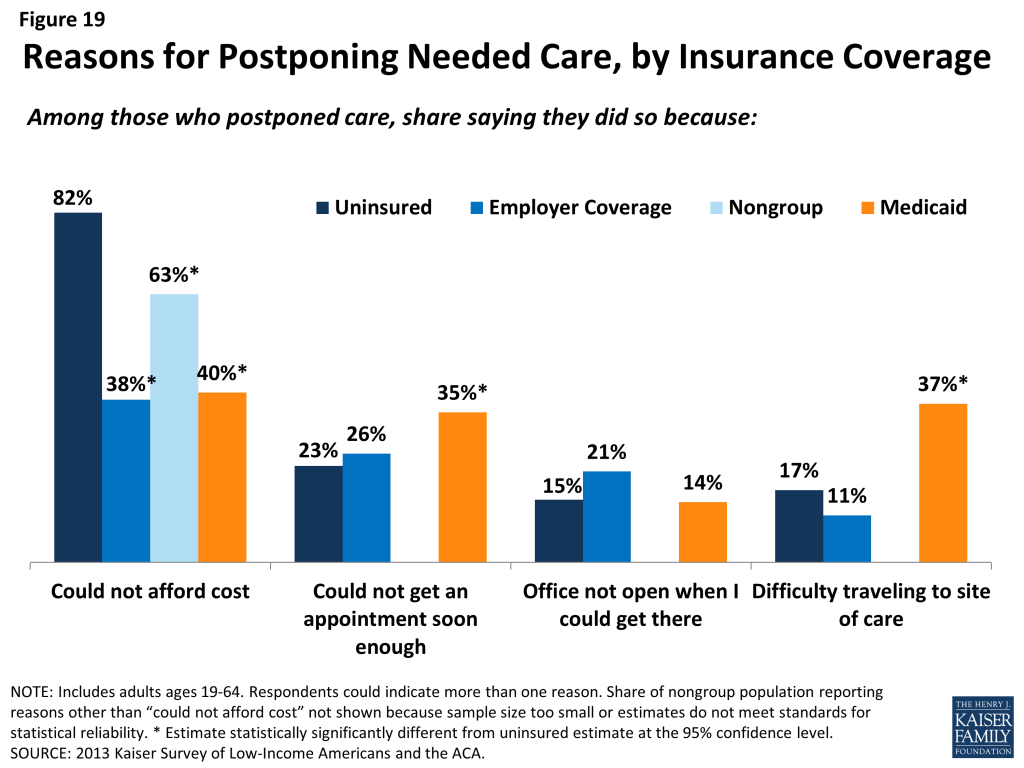

The most common reason for postponing care among the uninsured is cost, as the uninsured must pay the full cost of their care. Adults with employer coverage (38%), nongroup coverage (63%) or Medicaid (40%) are less likely to report cost as a reason for postponing care because presumably their insurance pays most or all of that cost (Figure 19). However, adults with Medicaid were more likely than other adults to report that they postponed care because they were unable to get an appointment soon enough or because they had difficulty traveling to the doctor’s office or clinic. These issues may reflect problems with provider participation in Medicaid, limits on Medicaid coverage of transportation services, or transportation barriers unique to the low-income population (such as not having a car). The only barrier that adults with employer coverage were more likely than other adults to report is the clinic or doctor’s office not being open at times when they could get there. This issue is a particular challenge for low-income workers, who often lose income when they take time off for a medical appointment during the day.

Given the health profile of the currently uninsured population, there is likely to be some pent-up demand for health care services among the newly-covered. Health systems may see increases in adults seeking care and will need to prepare for the newly insured. As people gain coverage under the ACA, the cost barriers to health care services will be reduced, but other barriers such as transportation or wait times for appointments may remain. The ACA included funds to expand service capacity in medically underserved areas, including expansion of community health centers, nurse-managed health centers and school-based clinics. To meet the health care needs of both insured and uninsured individuals, it is important that these systems develop flexible treatment times to accommodate people’s availability and expand capacity in areas where low-income individuals reside or seek care.

Many of the uninsured report limited options for receiving health care when they need it.

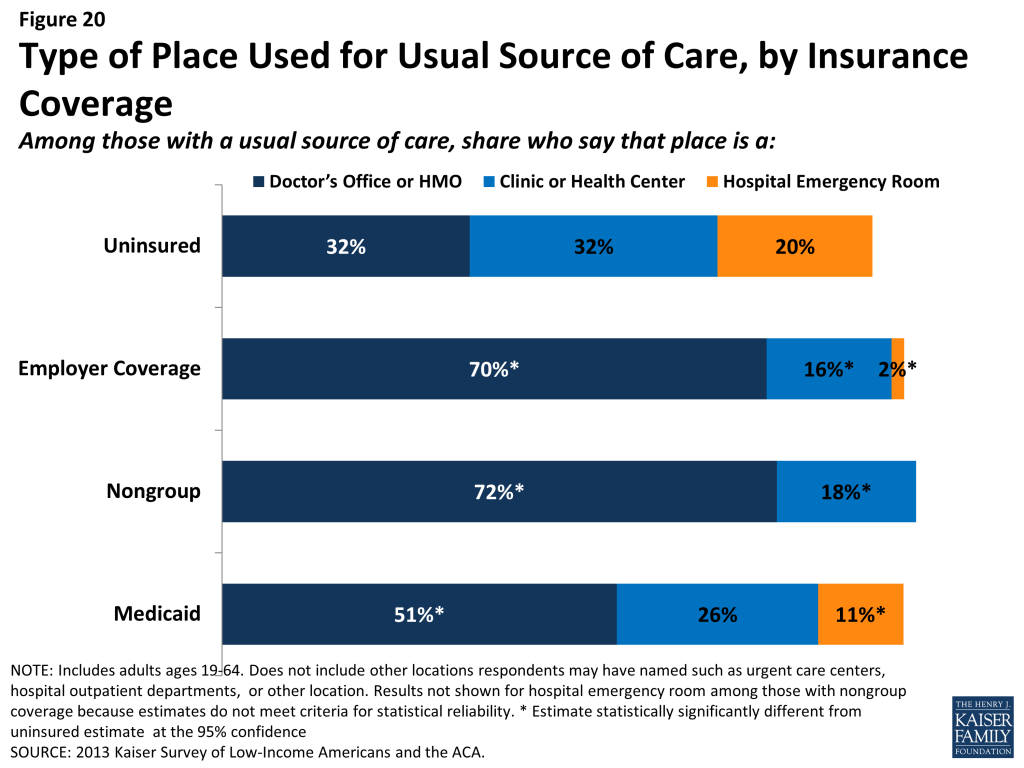

Uninsured adults are less likely than their insured counterparts to receive care in a private physician office when they do get care. About a third of uninsured adults (32%) report that a physician’s office or HMO is their regular source of care, compared to 70% of adults with employer coverage and more than half with Medicaid or other coverage (Figure 20). A third of uninsured adults who have a regular source of care (32%) report clinics or health centers as their usual source of care, twice as high as adults with employer coverage (16%). Notably, 20% of uninsured adults report the emergency room as their usual source of care – almost double the share of adults with Medicaid and ten times higher than adults with employer coverage (2%).

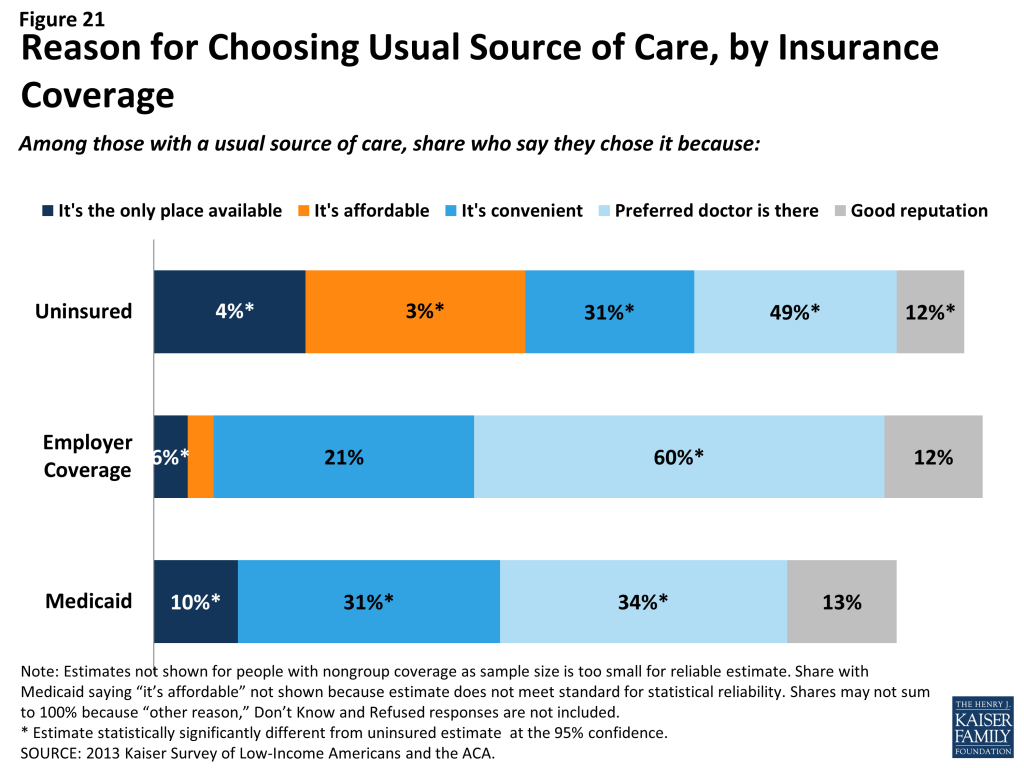

Uninsured adults are more likely than other adults to report that they have limited options for their usual source of care. Among people with a usual source of care, 18% of uninsured people report that they chose their usual source of care because it is the only option available to them, compared to 10% of adults with Medicaid and 4% with employer coverage (Figure 21). Of uninsured adults who say they had only one choice for care, almost half say that choice was the emergency department (data not shown). Uninsured adults are also more likely than other adults to choose their usual source of care because it’s affordable and less likely than other adults to choose their site of care because of convenience or ability to see their preferred provider. Most of those who say they chose their usual source of care based on cost say they chose a clinic or health center, reflecting that these providers often have a mission to serve low-income populations and offer services on a sliding scale.18

Based on the experience of their insured counterparts, the uninsured may have more options for where to receive their care once they obtain coverage under the ACA. Clinics and hospitals that already see a large share of uninsured adults may play an important role in enrolling this population in coverage and serving them once they gain insurance. However, these providers’ ongoing role—and people’s continuity of treatment— will depend in part on whether they are included in plan networks under both Medicaid and Marketplace plans. Further, many uninsured adults live in medically underserved areas, and it will be important to monitor whether coverage provisions are accompanied by delivery system reforms and new resources for primary care to expand access. Some individuals who have relied on emergency rooms or urgent care centers as their usual source of care may require help in establishing new patterns of care and navigating the primary care system. Last, in states that do not expand Medicaid, clinics and hospitals may continue to see high levels of the uninsured population and will remain the “safety net” for people who lack financial resources but need care.

Report: Iv. Health Coverage And Financial Security

How the ACA Might Affect Low and Moderate Income People’s Financial Situation

Low-income families face multiple financial challenges on a daily basis, but a major challenge is the cost of health care. Insurance provides some financial protection for many low-income adults, but many still struggle to pay their share of premiums or other costs associated with care. Low-income adults without coverage are particularly vulnerable, facing even more financial strain than their insured counterparts. Both insured and uninsured low-income adults struggle with medical bills and debt, and coverage expansions, assistance with premium costs, and limits on out-of-pocket costs under the ACA have the potential to ameliorate the financial issues associated with the cost of health care.

Health care costs pose a challenge for low- and moderate-income families, even if they have insurance coverage.

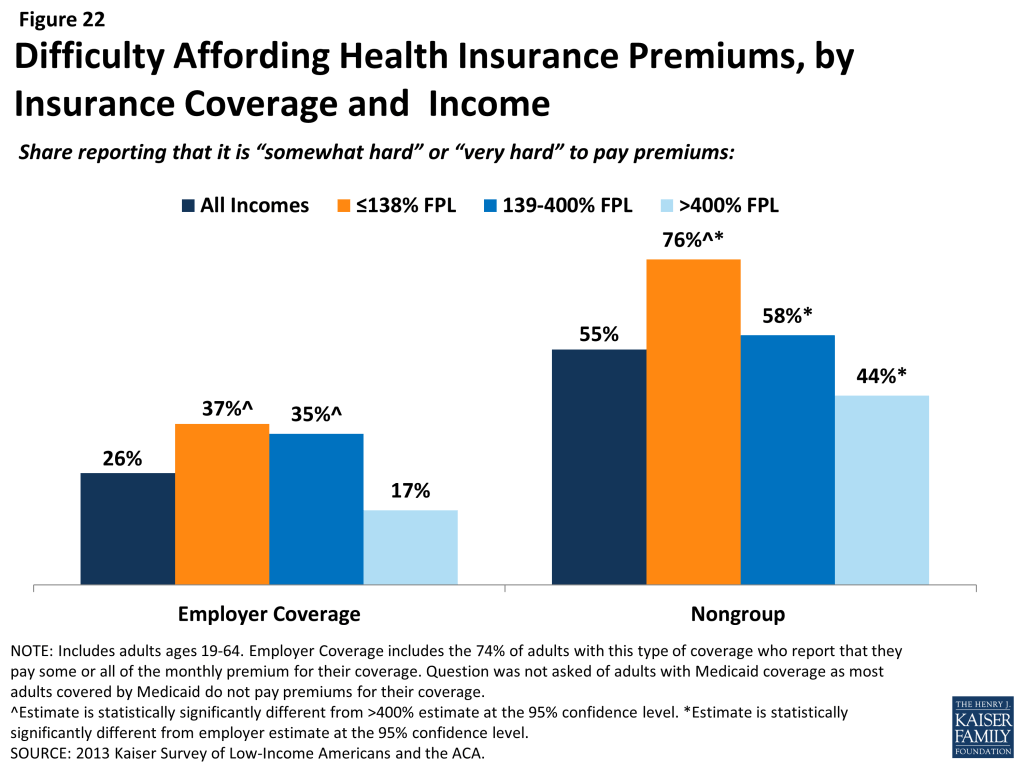

Health care accounts for a major budget item for low-income families, and affordability is a concern for many. Even among those with insurance, costs can be a burden. One source of cost burden is the cost of insurance itself. Nearly three-quarters of adults with employer coverage (74%) say they pay at least some part of their premium (data not shown), and adults with non-group coverage pay premiums directly to insurers themselves. Of adults who pay at least some portion of their premium, those with low incomes are most likely to report difficulty paying these costs (Figure 22). Thirty-seven percent of low-income (< 138% FPL) adults and 35% of moderate-income adults (139%-400% FPL) who pay a share of the premium for employer coverage report that their share is somewhat hard or very hard for them to afford, compared to 17% of higher-income (>400% FPL) adults with this coverage. For adults with non-group coverage, the rates are higher, with 76% of the low-income, 58% of the moderate income, and 44% of the higher income reporting difficulty paying their premiums. Since most adults with employer coverage share the cost of the premium with their employer, it is not surprising that rates of difficulty are higher among those with non-group coverage, who all pay the entire cost themselves.

Health care costs translate to medical debt for many l0w-income adults. While uninsured adults of all incomes are most likely to have outstanding medical bills, many low- and moderate-income insured adults also report high rates of medical bills that are unpaid or being paid off over time (Table 5). For example, 26% of low-income (<138% FPL) adults with employer coverage and 28% of low-income adults with Medicaid coverage report having medical debt. Some of these bills may reflect people’s coverage not covering all of their medical expenses, and some have been incurred during periods of uninsurance: 34% of insured adults with a gap in coverage have outstanding medical bills, compared to 23% with no gaps in coverage (data not shown). Some adults with Medicaid may have become eligible for their coverage as a result of having high medical bills, qualifying through a “medically needy” pathway for people who have high medical expenses.19 Once uninsured adults gain coverage, they may still have lingering medical bills from the past.

Regardless of coverage, medical bills can cause serious financial strain. People may report medical debt but not have a problem paying that debt. However, when asked directly whether they had problems paying medical bills in the past year, notable shares of low- and moderate-income adults reported that they did (Table 5). In many cases, the problems people had paying medical bills were severe. Adults in every coverage and income category reported that medical bills caused them to use up all or most of their savings, have difficulty paying for necessities, borrow money, or be contacted by a collection agency (Table 5).

| Table 5: Medical Debt and Problems with Medical Bills among Adults, by Income and Coverage | |||||

| Uninsured | Insured | ||||

| Employer | Nongroup | Medicaid | |||

| Has Outstanding Medical Bills or Paying Off Bills Over Time | |||||

| All | 39% | 21%* | 28%* | 30%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 40% | 26%* | — | 28%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 38% | 28%* | 31% | — | |

| >400% FPL | — | 15% | — | — | |

| Had Problem Paying Medical Bills in Past Year^ | |||||

| All | 22% | 9%* | 12%* | 15%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 25% | 18% | — | 17%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 17% | 13% | — | — | |

| >400% FPL | — | 4% | — | — | |

| Medical Bills Led to Serious Financial Strain^,^^ | |||||

| All | 20% | 7%* | 11%* | 12%* | |

| By Income | |||||

| <138% FPL | 23% | 13%* | — | 14%* | |

| 139-400% FPL | 15% | 11% | — | — | |

| >400% FPL | — | — | — | — | |

| Notes: Excludes people covered by other sources, such as Medicare, VA/CHAMPUS, or other state programs.”–“: Estimates with relative standard errors greater than 30% or cell sizes below 50 are not provided.^ Excludes people who reported a problem with medical bills that were not their own.^^ Defined as reporting that medical bills caused them to use up all or most savings; have difficulty paying for necessities; borrow money; or be contacted by a collection agency.* Estimate statistically significantly different from uninsured estimate at the 95% confidence level.SOURCE: 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA. | |||||

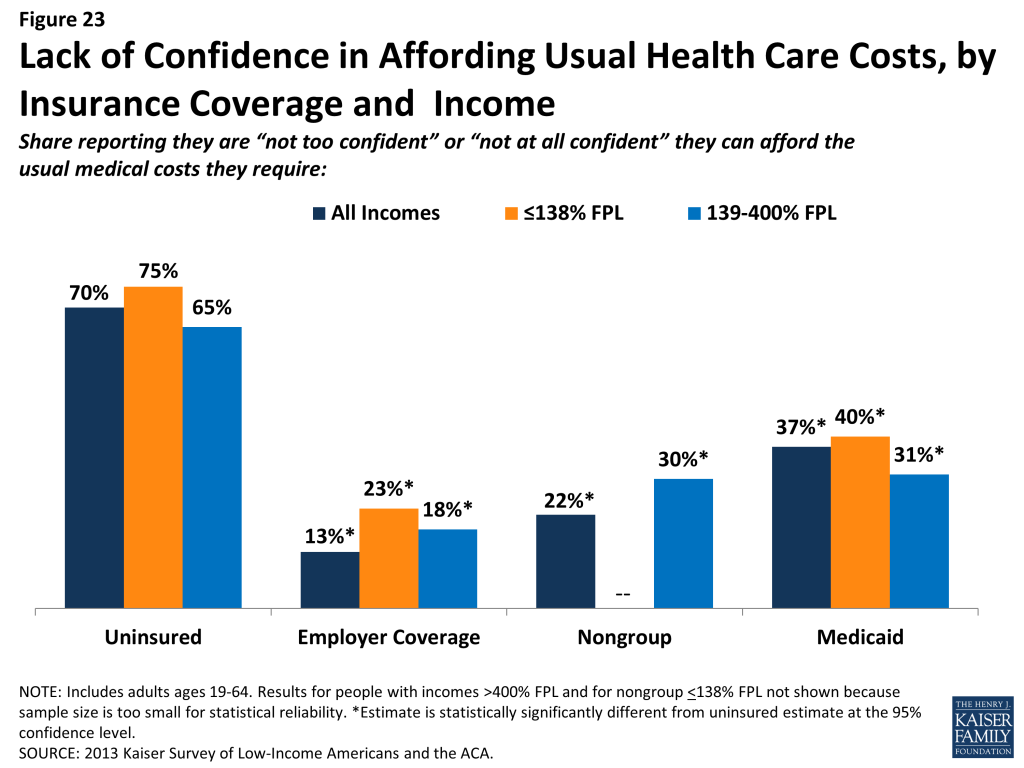

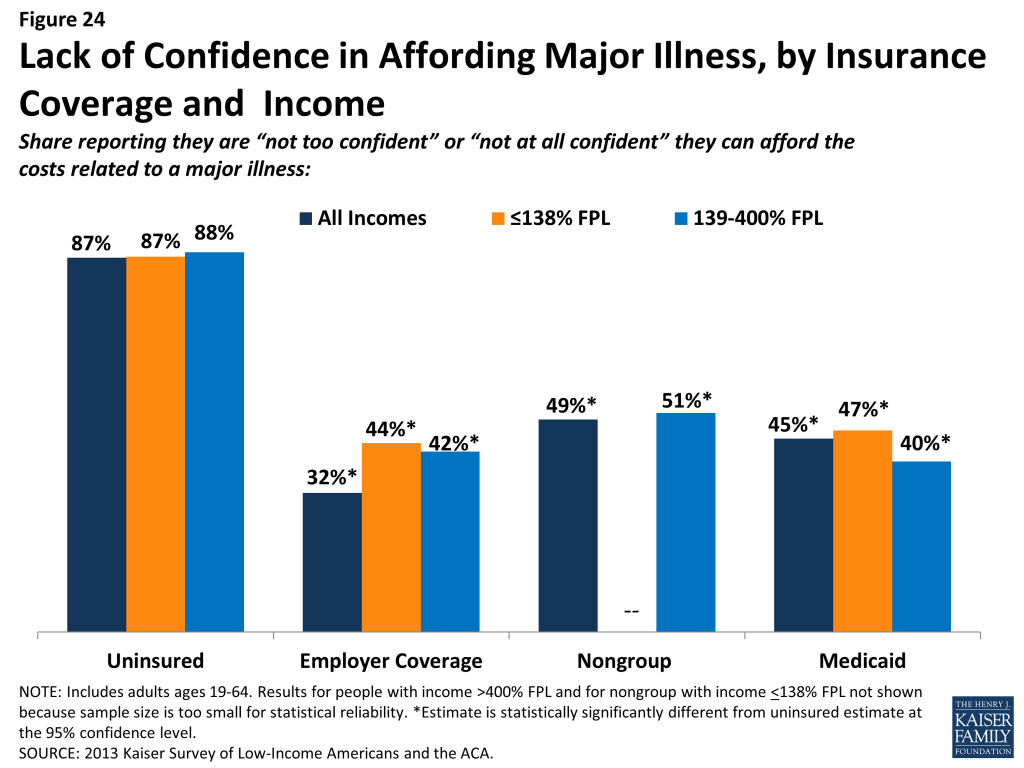

In addition to many low-income adults reporting that they have experienced financial strain or difficulty with health care costs, many live with worry about their ability to afford costs in the future. The vast majority of low- and moderate-income uninsured adults report that they lack confidence that they could afford either the cost of care for services they typically require (Figure 23) or the cost of care should they face a major illness (Figure 24). While not surprising, this finding indicates that uninsured adults are aware of the high cost of health care services, as even those with moderate or high incomes do not believe they can afford these costs. One role of insurance coverage is to protect people against these costs, particularly unexpected costs related to major illnesses or accidents. However, notable shares of low-income insured adults report that they lack confidence in their ability to afford health care, given their current finances and health insurance situation. Over a third of adults on Medicaid report lack of confidence in affording usual costs, a finding that appears to be driven by higher need among Medicaid beneficiaries (as those with disabilities report particularly high rates) or worry about keeping coverage (as those who had problems with renewal also report high rates) (data not shown). Of particular note is the finding that about half of adults with nongroup coverage do not feel confident that they could afford costs related to a major illness given their coverage and financial situation. This lack of confidence may reflect worry about affording out-of-pocket costs or concerns over limits on coverage.