Coverage Expansions and the Remaining Uninsured: A Look at California During Year One of ACA Implementation

Executive Summary

Under the ACA, millions of individuals have gained coverage through new provisions, effective as of January 2014, to expand Medicaid and provide premium tax credits for coverage purchased through Health Insurance Marketplaces. In California, coverage gains were substantial, with 2.7 million people gaining Medi-Cal coverage and nearly 1.7 million people determined eligible for enrollment through Covered California between October 2013 and September 2014.1 California is a bellwether state for understanding the impact of the ACA. The state’s sheer size and its high rate of uninsured prior to ACA implementation means that its experience in implementing the ACA has implications for national coverage goals. In addition, California was an early and enthusiastic adopter of the ACA; the state implemented an early Medicaid expansion through its Low-Income Health Program (LIHP) and was the first to create a state-based Marketplace.

While much attention has been paid to enrollment in new coverage options and changes in the uninsured over the past year, less is known about how this coverage has affected people’s lives. To help fill this gap, the Kaiser Family Foundation is conducting a series of comprehensive surveys of the low and moderate-income population. This report uses the California sample of the 2014 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, funded by the Blue Shield of California Foundation, to examine Californian adults that gained coverage and remained uninsured in 2014. It also provides information on how the newly insured view their coverage and any problems they have encountered in using their coverage; how the remaining uninsured and newly insured fare with respect to access to medical care and financial burden; and why people in California continue to lack coverage and their plans for obtaining coverage in 2015. Additional detail on the survey methods is available online.

Background: ACA Implementation in California

Leading up to full implementation of the ACA and during the first year of major coverage expansions, California actively pursued opportunities to expand coverage for residents, conducted outreach and enrollment to bring people into new coverage options, and organized systems to deliver care. The state’s 2010 “Bridge to Reform” §1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waiver included early expansion of Medicaid in most counties through the Low-Income Health Program (LIHP), and in 2014, Medi-Cal coverage was expanded statewide to low-income citizens and legal immigrants. As of 2014, middle-income residents are eligible for premium subsidies to purchase coverage through Covered California. The state took steps to simplify and streamline enrollment such as automatically transitioning individuals from LIHP to Medi-Cal, creating a single online portal for Covered California and Medi-Cal applications, and adopting the Express Lane Enrollment Project to target adults and children enrolled in California’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. The state also invested heavily in outreach and enrollment efforts for both Medi-Cal and Covered California. These included statewide marketing campaigns, community mobilization and targeted efforts to reach vulnerable populations.

Despite all these efforts, the state—like all states—experienced outreach and enrollment challenges in 2014. Organizations and individuals in California cited a shortage of in-person assisters, problems with cultural and linguistic resources, technological issues with the Covered California website, and a Medi-Cal backlog, which led to delayed or abandoned applications. The agency received criticism for not doing more to reach hard-to-reach populations, particularly Hispanics and immigrants with Limited English Proficiency (LEP). These challenges notwithstanding, the state enrolled unexpectedly large numbers of people in 2014. In late 2014 and 2015, the state was taking action to address many of the challenges it faced during the first open enrollment period.

Who gained coverage and who remained uninsured?

Examining characteristics of the previously insured, newly insured and remaining uninsured are important to understanding who gained and who was left out of coverage in 2014 and targeting ongoing outreach.

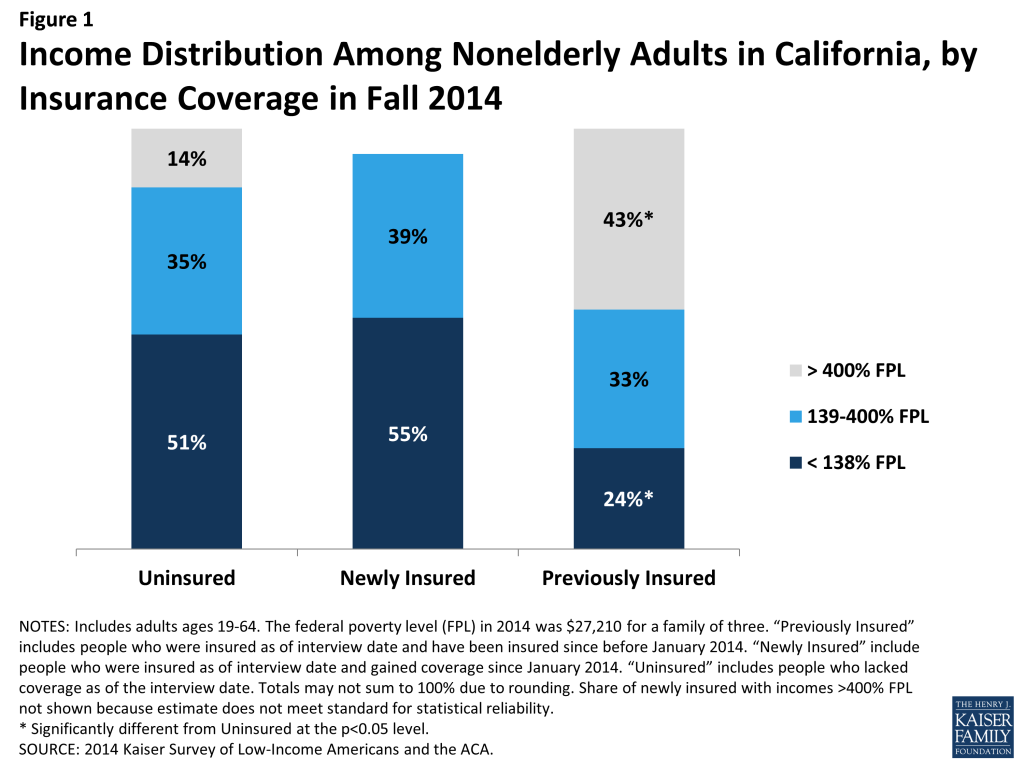

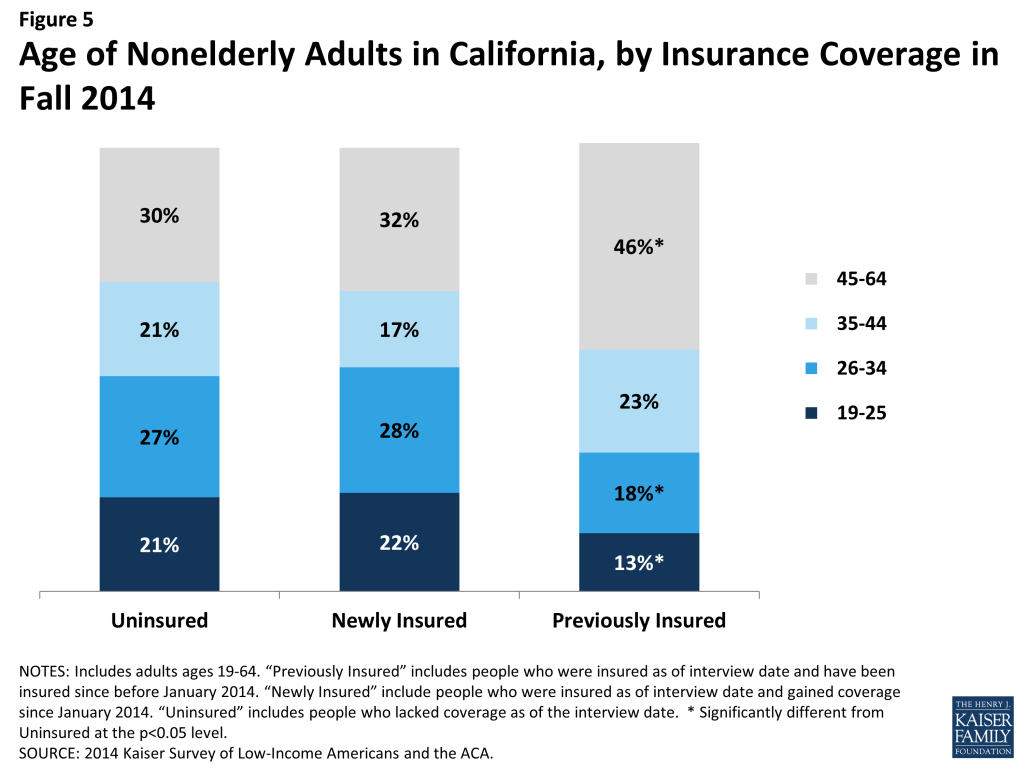

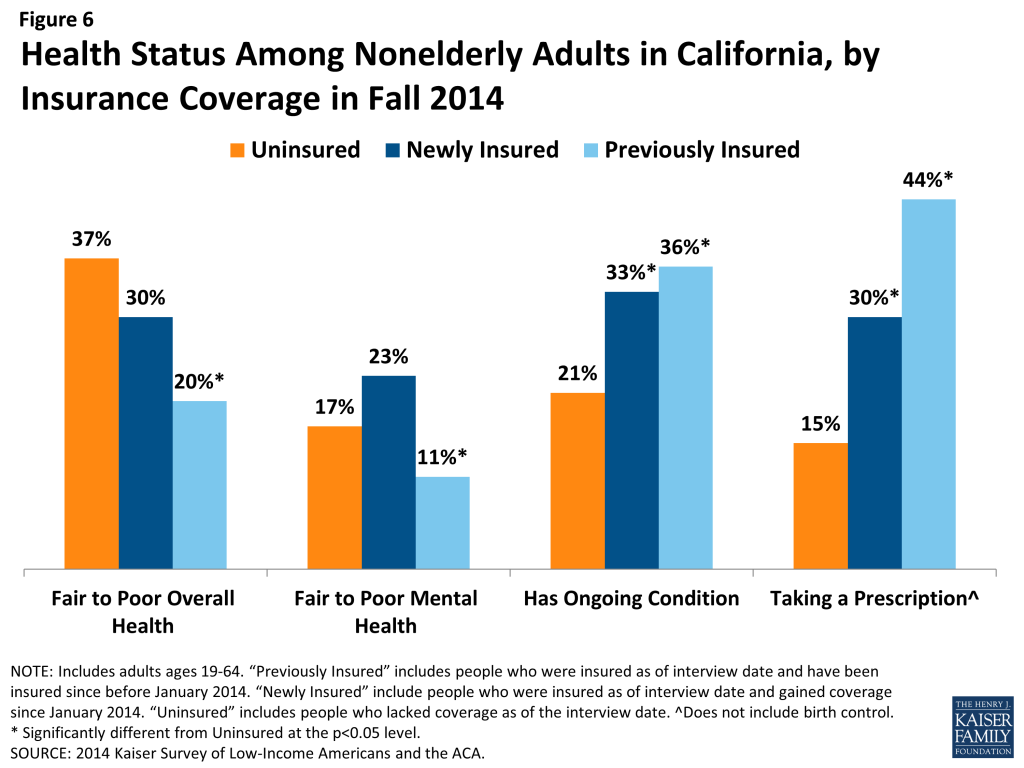

The newly insured and remaining uninsured populations resemble each other with respect to income, age, and health status and have different characteristics from the previously insured. The vast majority of newly insured (94%) and uninsured adults (86%) in California meet the income requirements for Medi-Cal or subsidies in Covered California (below 400% FPL), compared to just over half of the previously insured (57%). In addition, the share of uninsured (21%) and newly insured (22%) who are young adults (age 19-25) were about the same, while previously insured were less likely to be young adults (13%). While there are no significant differences in the share of uninsured (37%) and newly insured adults (30%) who say their health is fair or poor, uninsured adults are less likely than adults with coverage to have a diagnosed medical condition. These patterns indicate that older or sicker individuals did not disproportionately take up coverage in 2014.

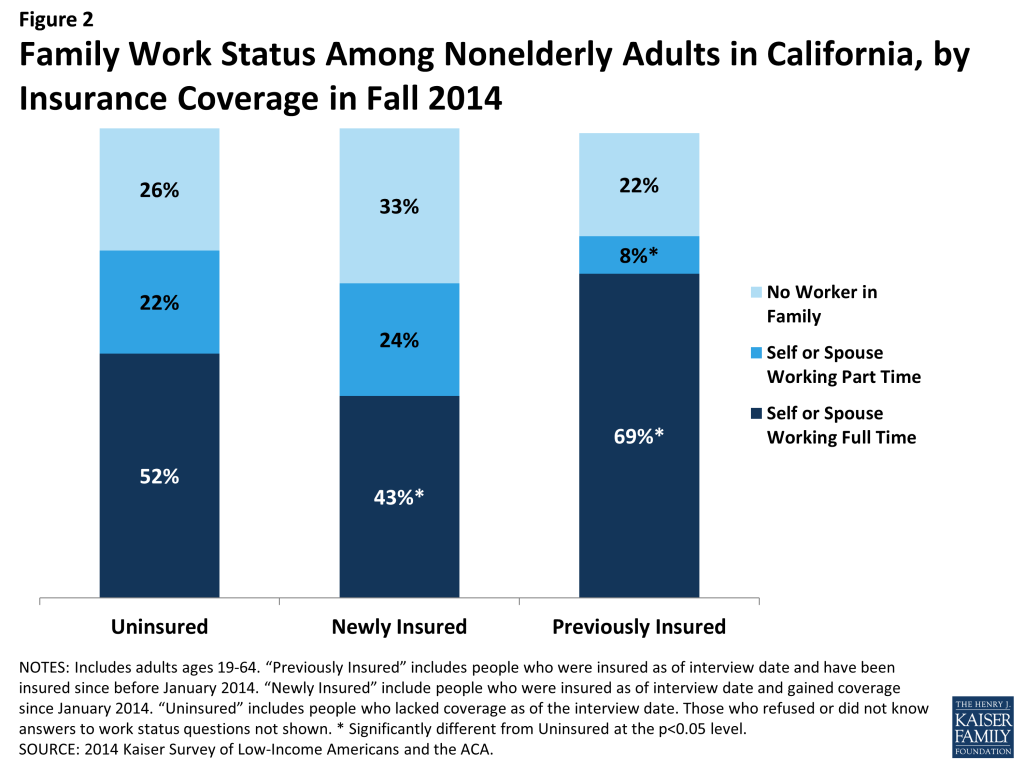

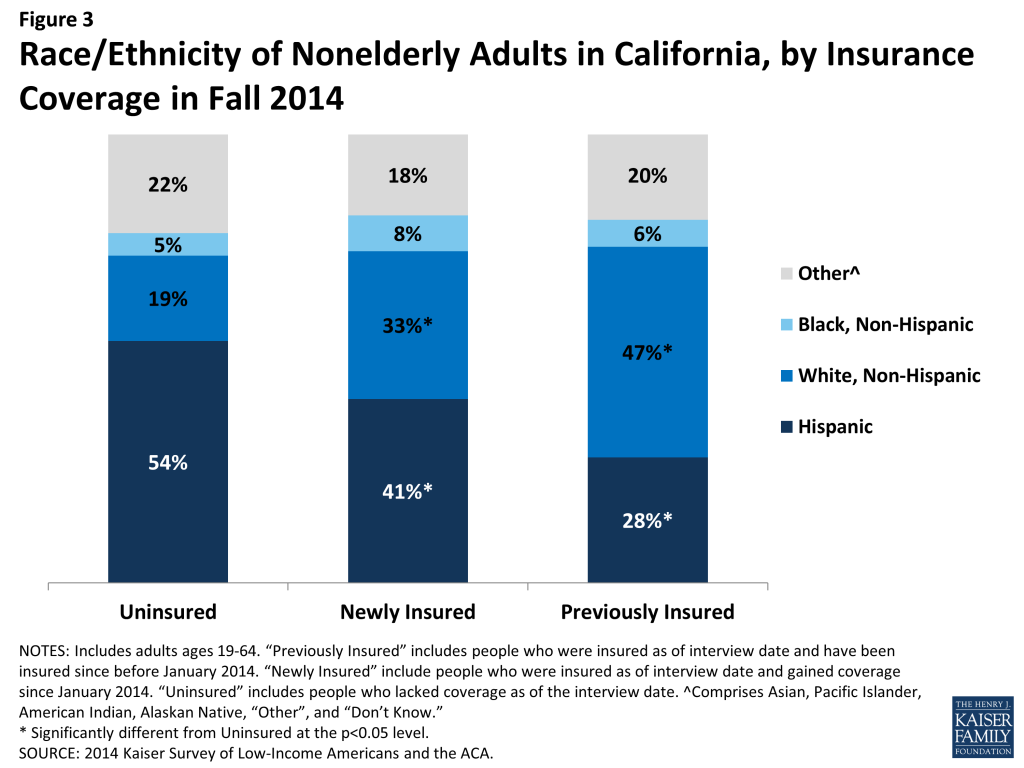

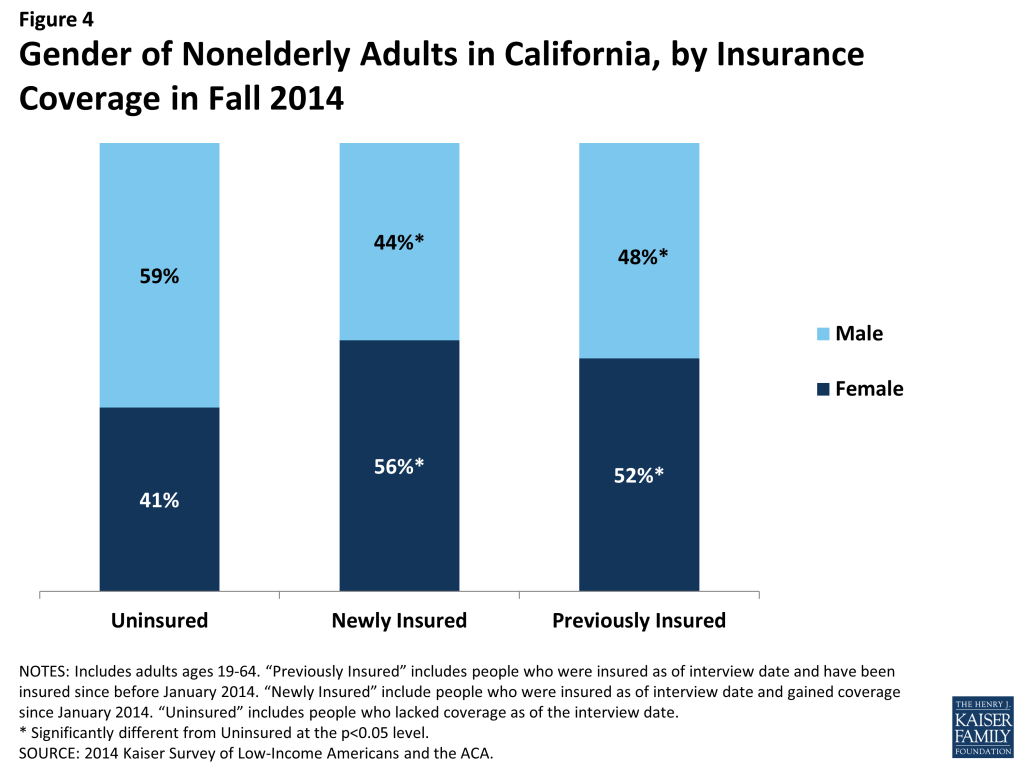

However, the insured and uninsured populations in California differ on some important factors, such as race/ethnicity, work status, gender and immigration status. Mirroring historical patterns and legal barriers to coverage, the remaining uninsured population is more likely than the insured to be Hispanic, to be male and to be undocumented. The high share of remaining uninsured who are Hispanic may reflect barriers in outreach to this population or eligibility limits based on immigration. Though most newly insured and uninsured adults are in a family with a full or part-time worker, the specific work profile differs between groups: newly insured adults are less likely than remaining uninsured adults to be in a family with a full-time worker (versus only a part-time worker). With new coverage provisions in place as of 2014, there were more options for health insurance outside employment, and groups traditionally left out of the employer based system—such as part-time workers or low-wage workers—had new avenues for coverage.

Who is covered by different programs in California?

Understanding the profile of the population covered by different types of insurance in the state is essential to designing effective health plans to serve their needs. With the expansion of Medi-Cal, the program grew to include individuals not traditionally covered by the program, which has changed the profile of the overall program in some ways. The profile of Covered California enrollees shows that the program is playing an essential role in covering groups that have been left out of coverage expansions in the past.

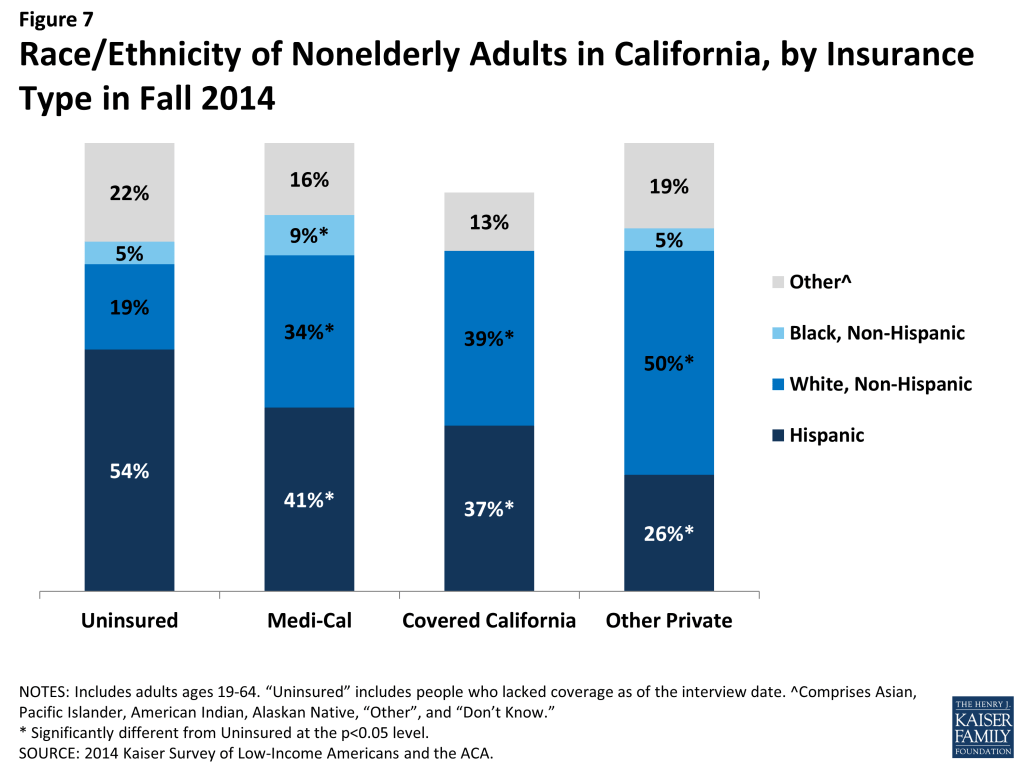

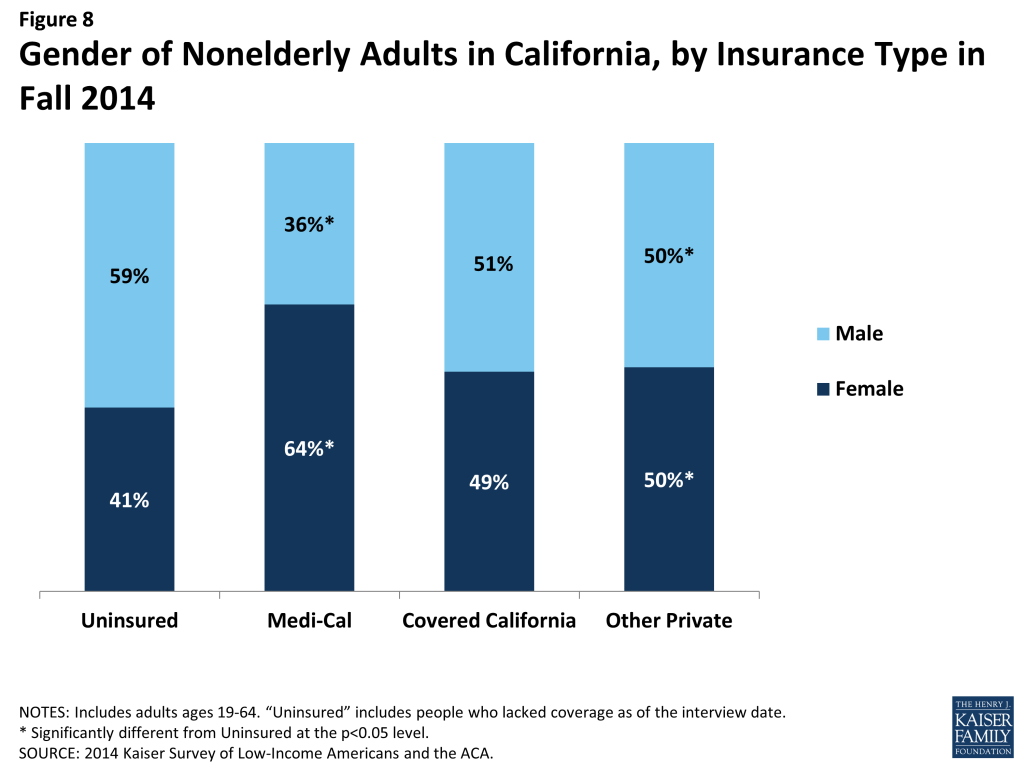

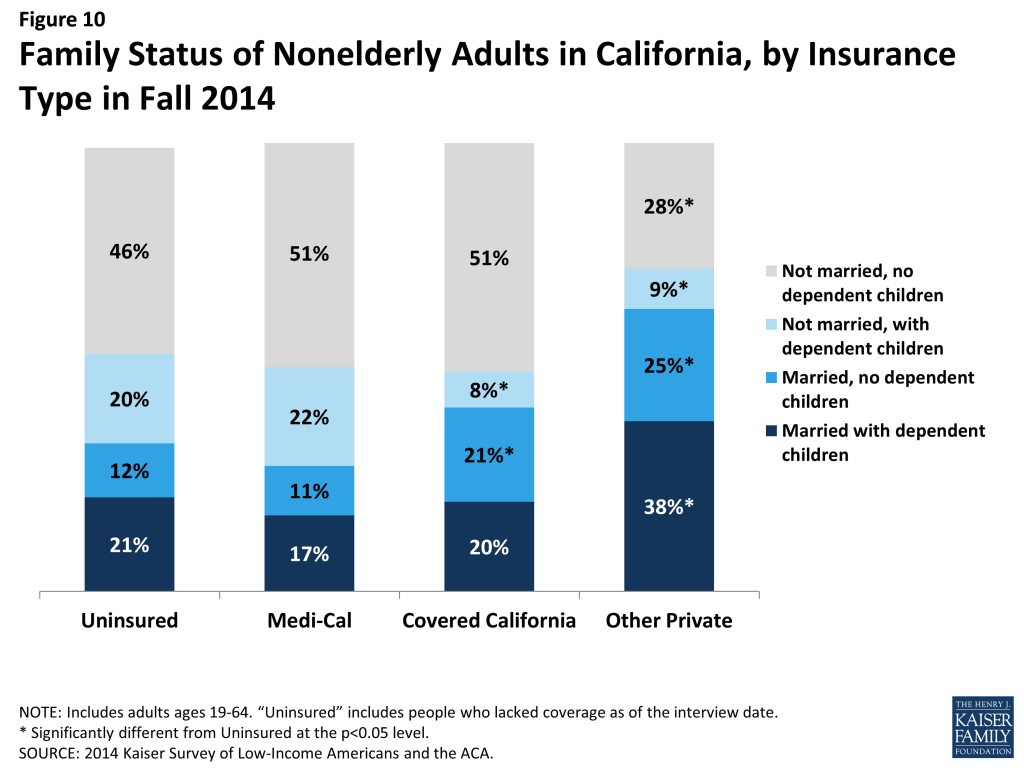

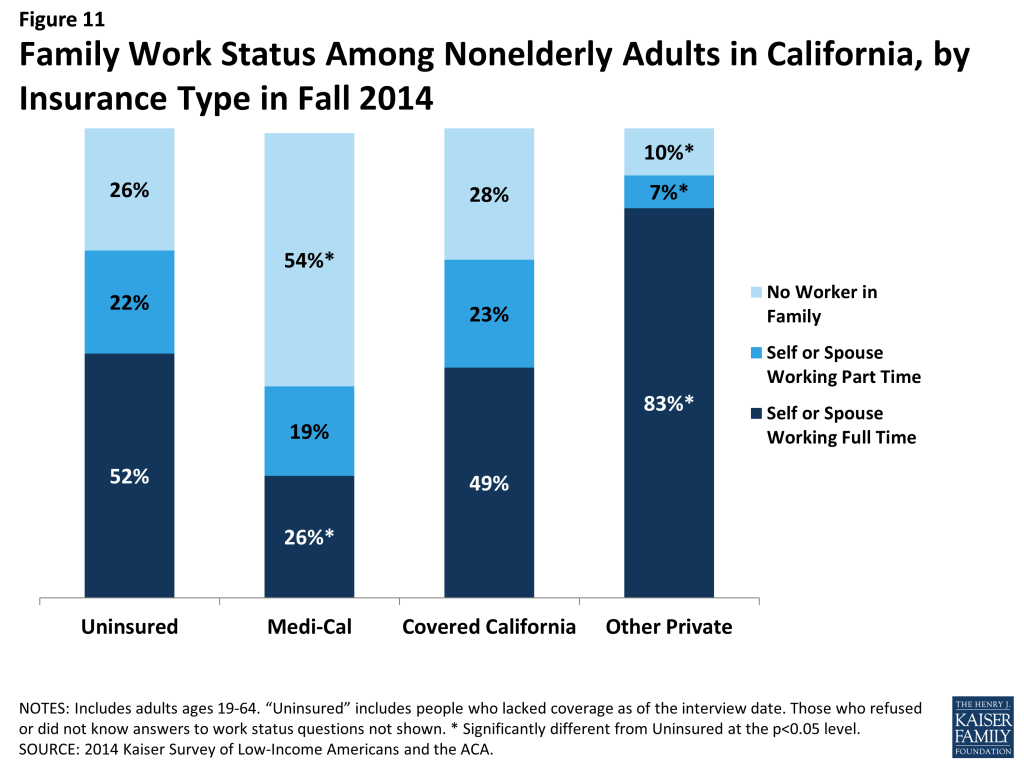

Medi-Cal and Covered California enrollees are more likely to be racially diverse, and are made up primarily of working adults without dependent children. Whereas half of those with other private insurance identify as White Non-Hispanic, two-thirds of Medi-Cal and 60% of Covered California enrollees identify as a person of color. Adults without dependent children have generally been excluded from public coverage and assistance in the past, but in 2014, 62% of adult Medi-Cal enrollees and 72% of adult Covered California enrollees did not have dependents. Further, about half of Medi-Cal and nearly three-quarters of Covered California adults are in a working family, though a larger share of adults in Covered California are in a family with a full-time (49% vs. 26%) or part-time (23% vs. 19%) worker. By gender, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults covered by Medi-Cal are female, compared with about half of adults with Covered California or other private coverage.

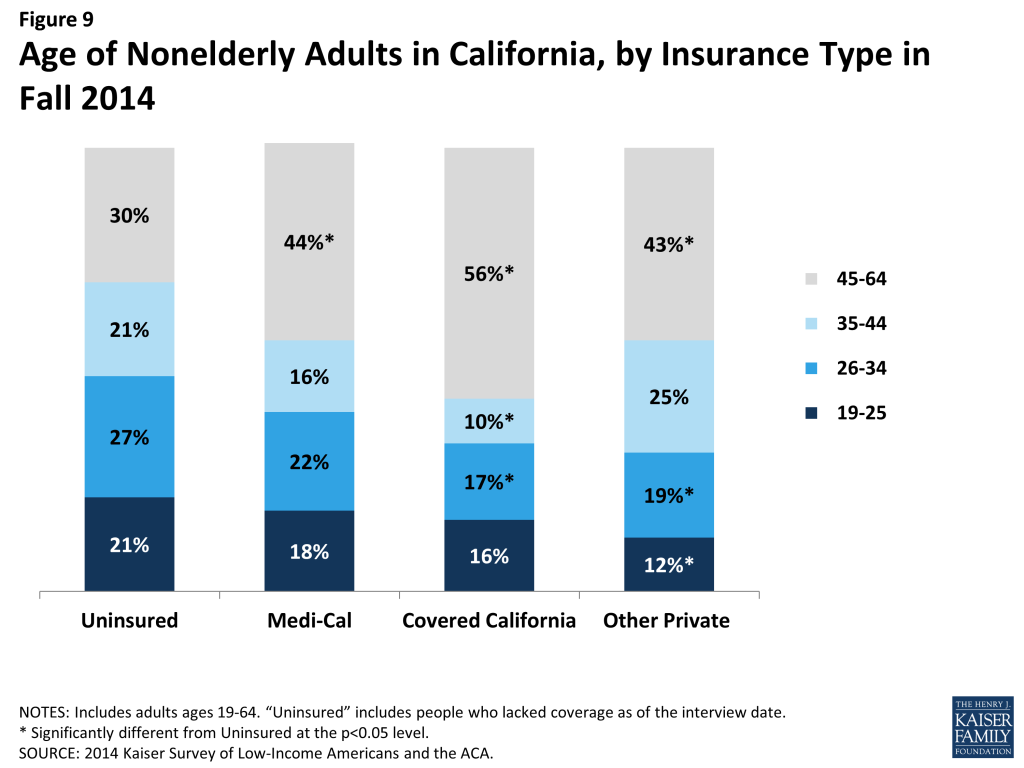

Though the adult Medi-Cal population is younger than that of other coverage groups, enrollees have poorer health status. Forty percent of adult Medi-Cal enrollees are under age 34, compared to about a third of Covered California adults and adults with other private coverage. Notably, more than half of adults enrolled in Covered California are over age 45. Nonetheless, Medi-Cal retains many of its traditional roles of serving many individuals with substantial health needs: In 2014, Medi-Cal beneficiaries were more likely than adults with other types of coverage to say their physical health or mental health was fair or poor and more likely to have an ongoing health condition.

What has happened to access to care for the insured and remaining uninsured?

The ultimate goal of expanding health insurance coverage is to help people access the medical services that they need. The survey findings reinforce a large body of literature showing that adults with coverage have better access to care than those who remain without coverage.

Newly insured adults were more likely to change where they usually go for care than their previously insured counterparts, but clinics remain an important source of care for newly insured adults. Newly insured adults were more likely than those who remained uninsured to have a usual source of care and a regular doctor at their usual source of care. Of those, nearly a fifth (19%) reported changing where they usually go for care since gaining coverage, and most said it was due to their insurance. These rates were higher than those among the previously insured. Still, both uninsured and newly insured adults with a usual source of care are most likely to use a clinic or health center for that care, compared with previously insured adults who were most likely to use a doctor’s office or HMO. When asked why they chose their site of care, more than a third (37%) of uninsured adults say they use their usual source of care because it is affordable, compared with 40% of newly insured who chose it because it was convenient.

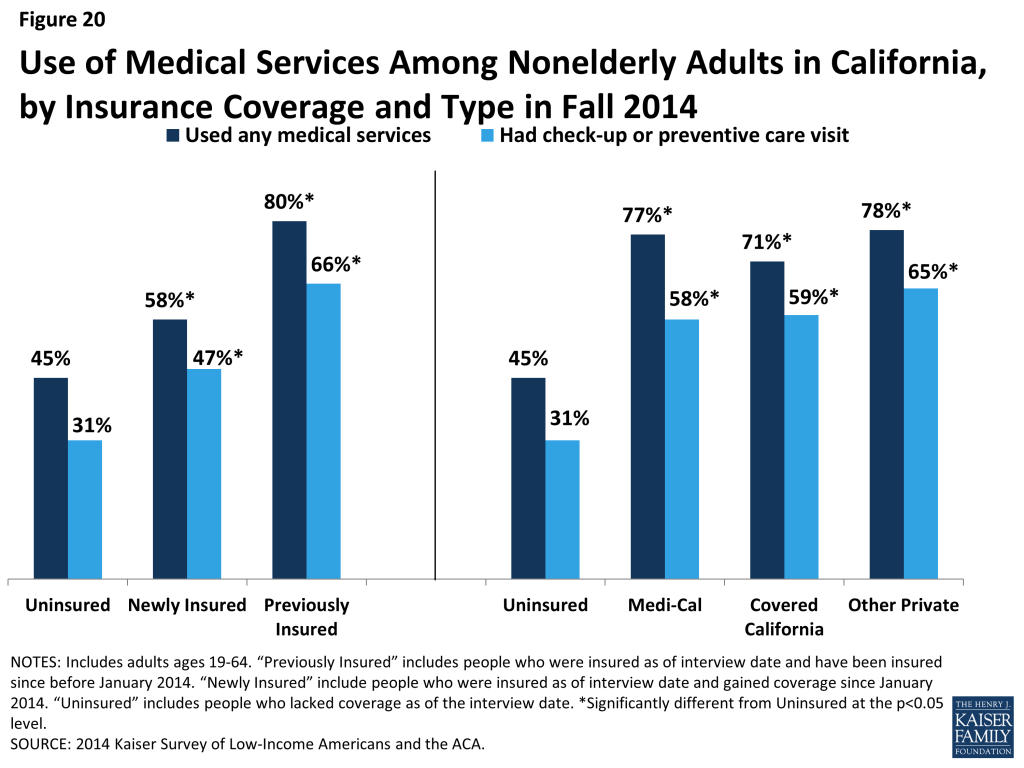

Adults with insurance coverage were more likely than the uninsured to have used medical services or received preventive care. More than half (58%) of newly insured adults said that they used at least one medical service since gaining their coverage, and nearly half (47%) had received a preventive visit or check-up. Still reflecting some unmet need, more than a third of newly insured adults (35%) reported that they postponed or went without needed care, the same share as the uninsured. Among those who do have coverage, postponing care could be related to several factors, including difficulty finding a provider, problems navigating the health system and health insurance networks, misunderstanding of how to use coverage and when to seek care, or concerns about out-of-pocket costs.

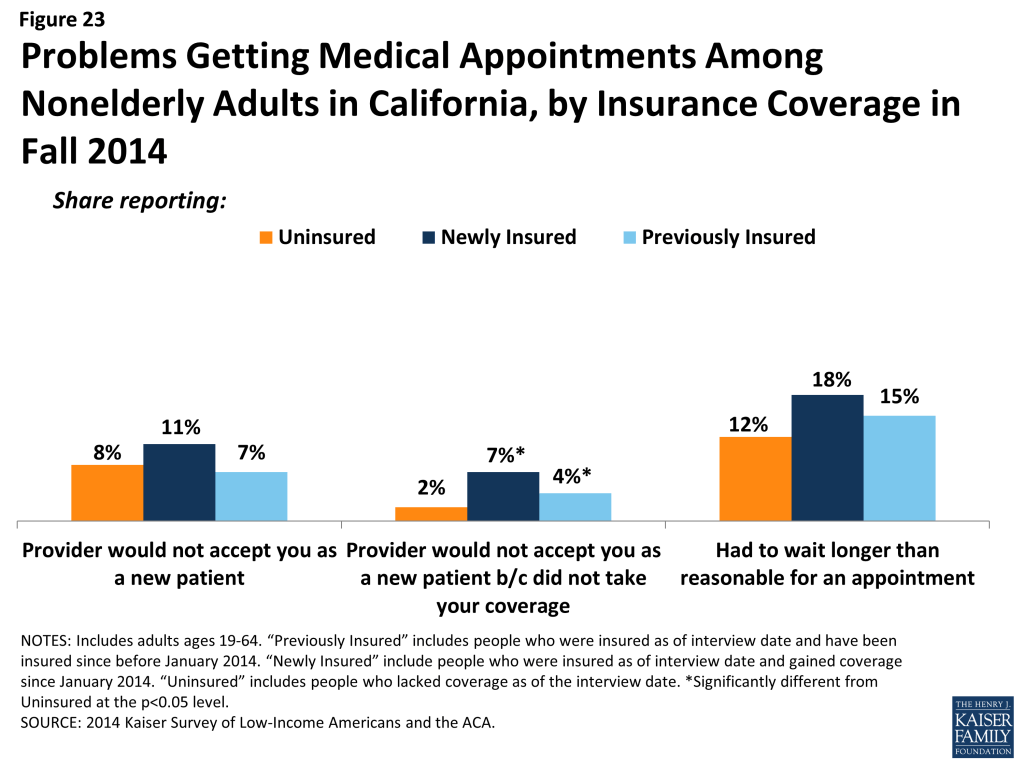

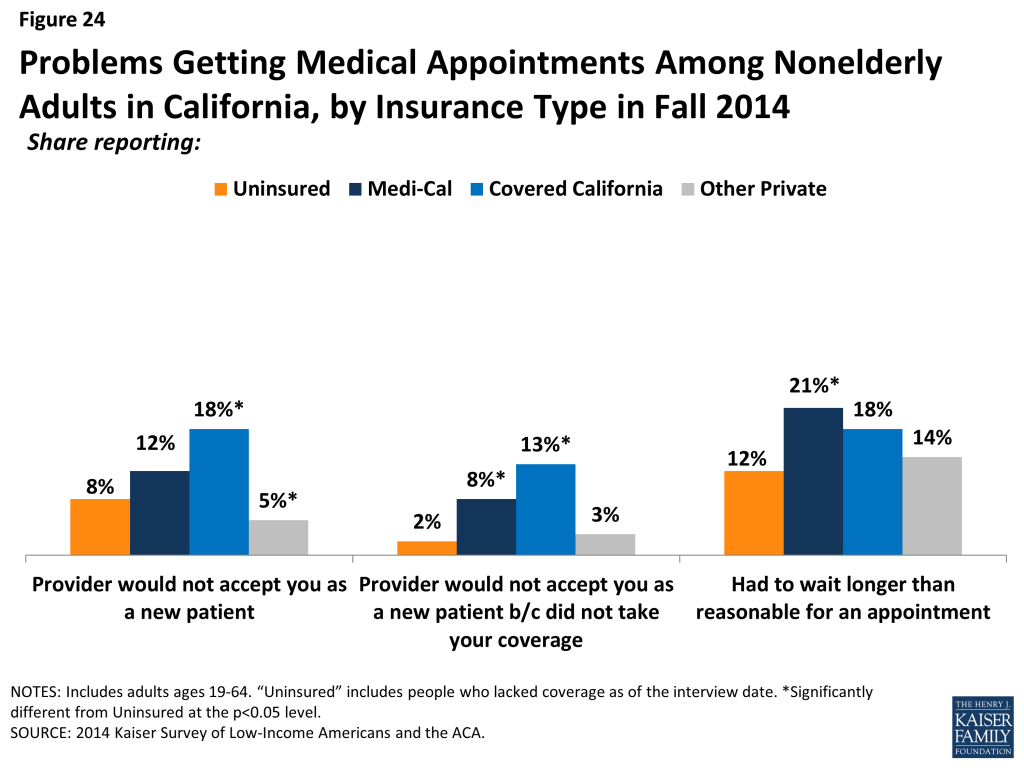

Though most adults did not report problems getting appointments, adults with Covered California or Medi-Cal were more likely than those with other private coverage to say a provider would not see them due to coverage. Compared to only 3% of adults with other private coverage, 13% of adults with Covered California and 8% of adults with Medi-Cal say a provider would not take them as a patient because of their coverage. Medi-Cal enrollees also reported higher rates of long waits for appointments (21%) than those with other private coverage. Like the forces underlying choice of usual source of care, these issues may reflect continuing problems with network adequacy, despite the existence of state standards for network adequacy and patient access.

How do people view their coverage?

People’s views of their plan may affect not only their use of their coverage but also the likelihood that they re-enroll in coverage or change plans. Survey findings indicate that, while most people do not report problems with their plan, additional education may be needed to help newly insured people understand their coverage.

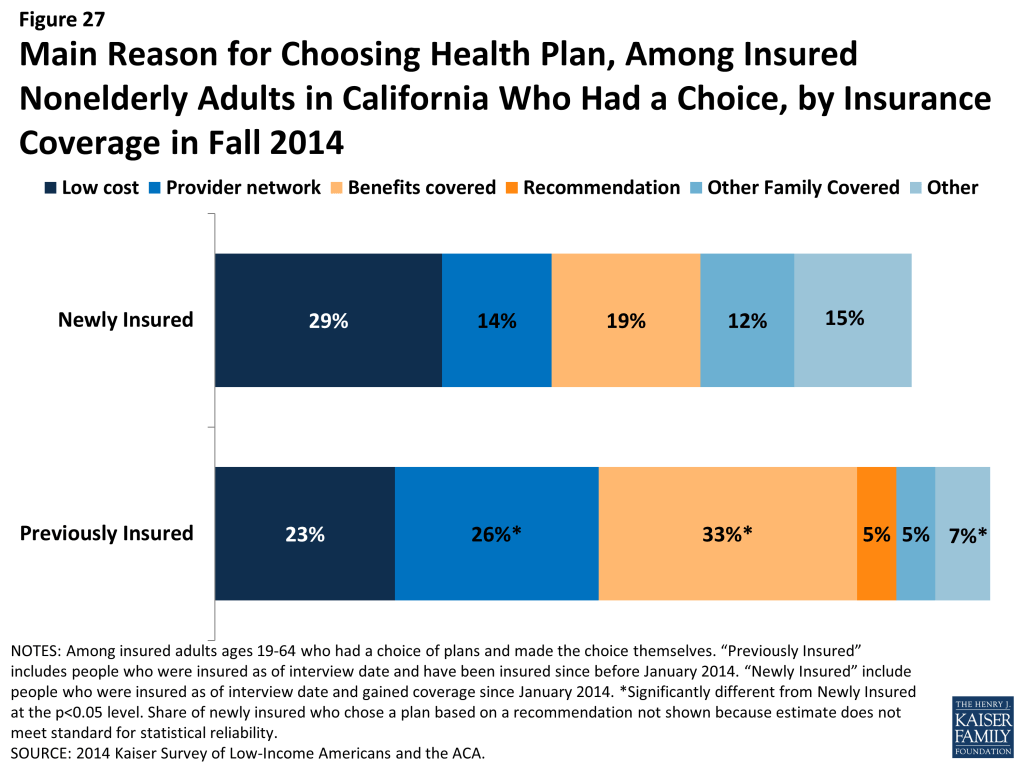

Newly insured adults were less likely to prioritize scope of coverage or provider networks in choosing their plan than previously insured adults. Less than a fifth (19%) of newly insured adults say they chose their plan because of the benefits covered, compared to 33% of previously insured adults, and only 14% say they chose their plan based on provider network (versus 26% of previously insured). Rather, newly insured adults were most sensitive to price when choosing their plan, with nearly a third saying they chose based on price. These patterns likely reflect regulations requiring similar scope of benefits across new plans and ongoing price sensitivity among low and middle income adults.

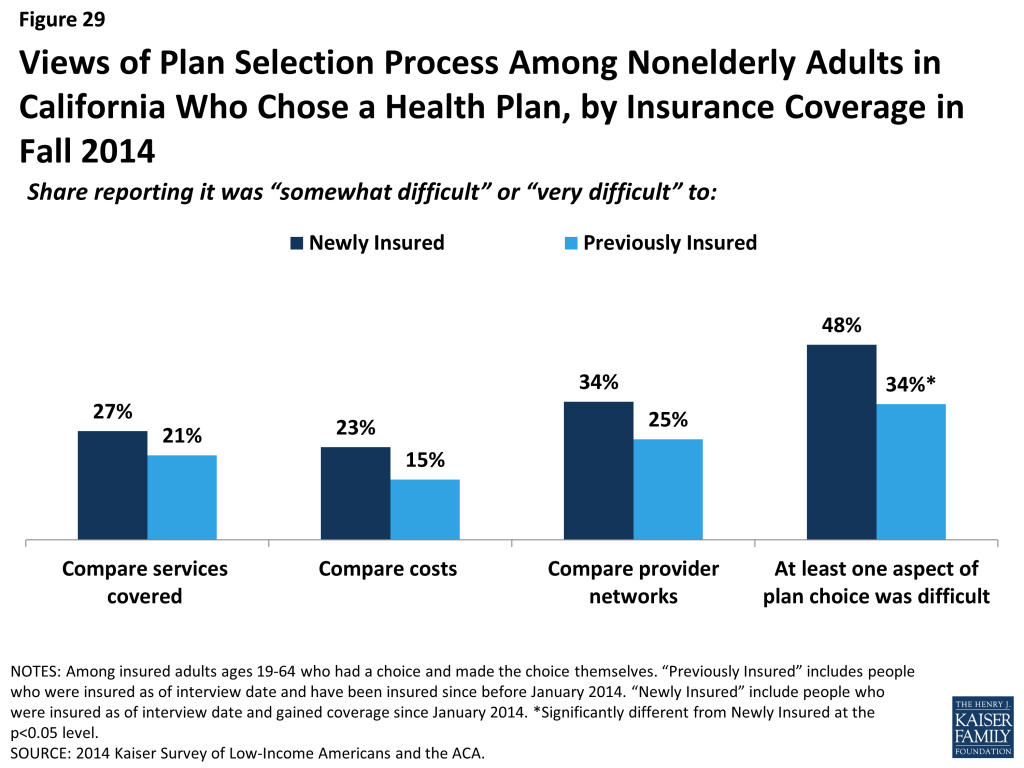

Across coverage groups, most insured adults did not report having difficulty with the plan selection process or other specific problems with their health plan. There were no significant differences across groups comparing services, costs, or provider networks across plans, though the newly insured were more likely than the previously insured to report at least one difficulty (48% versus 34%). When asked specifically if they encountered various problems with their coverage, such as scope of coverage, costs, or customer service, newly insured adults reported similar or lower rates than previously insured.

Newly insured adults were less likely than previously insured to understand the details of their plan and to give their health plan high ratings. Compared with the previously insured, newly insured adults were less likely to say they understand the services their plan covers (65% vs. 80%) or how much they would have to pay when they visit a health care provider (66% vs. 84%) “very well” or “somewhat well.” Though 70% of newly insured adults rate their coverage as “excellent” or “good” (versus “not so good” or “poor”), this rate was lower than that among previously insured adults (87%). It is possible that newly insured adults face challenges in understanding the complexity of insurance coverage, especially since many adults who were uninsured before the ACA reported that they had never had health insurance.

How does coverage affect financial security?

Health care costs can be a major burden for low-income families. Survey findings indicate that while coverage can ameliorate some of the financial challenges that low and moderate income adults face, many will continue to face financial challenges in other areas of their lives.

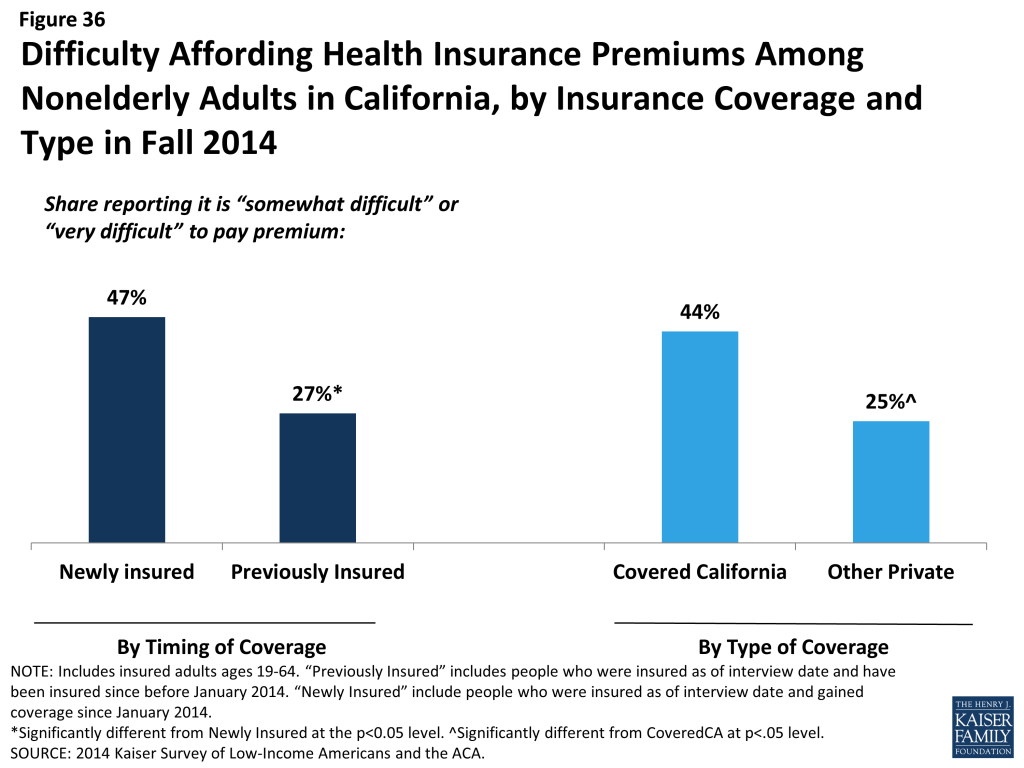

Many Covered California enrollees report difficulty paying their monthly premium. Nearly half of newly insured adults (47%) say it is somewhat or very difficult to afford their monthly premium, compared to just 27% of adults who were insured before 2014. Further, 44% of Covered California enrollees report difficulty paying their monthly premium, versus a quarter of adults with other types of private coverage.

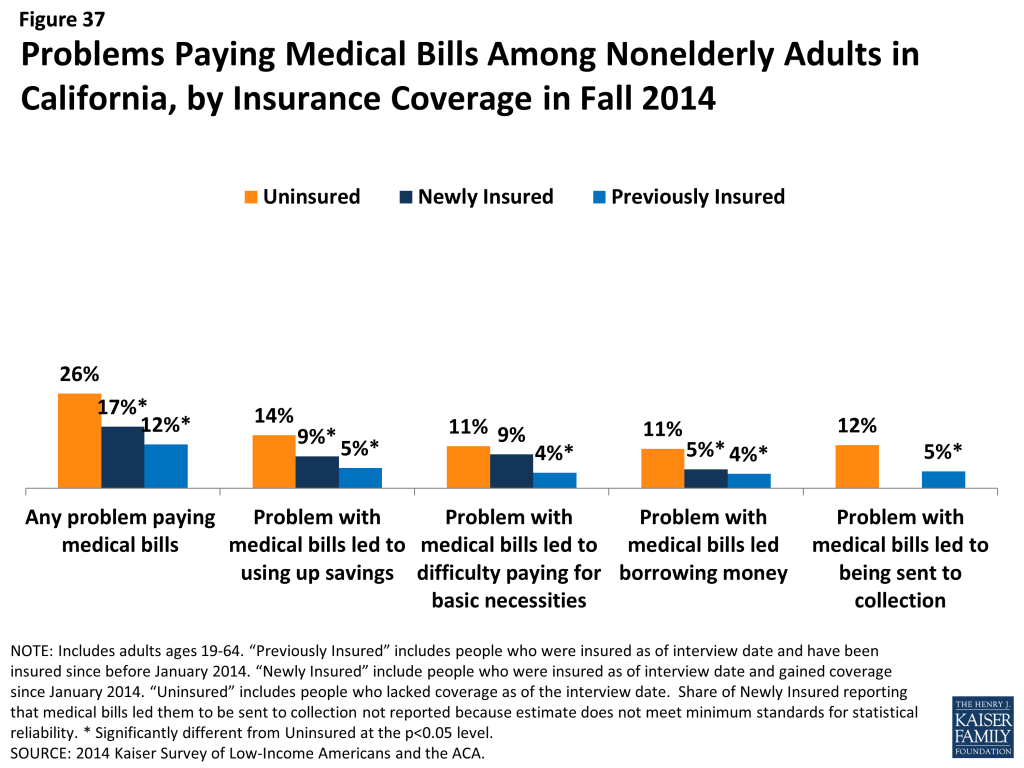

However, coverage does provide financial protection from medical bills and eases concern over affording medical care. Compared to the uninsured, both newly insured and previously insured adults report lower rates of difficulty paying medical bills and living with worry about their ability to afford medical care in the future.

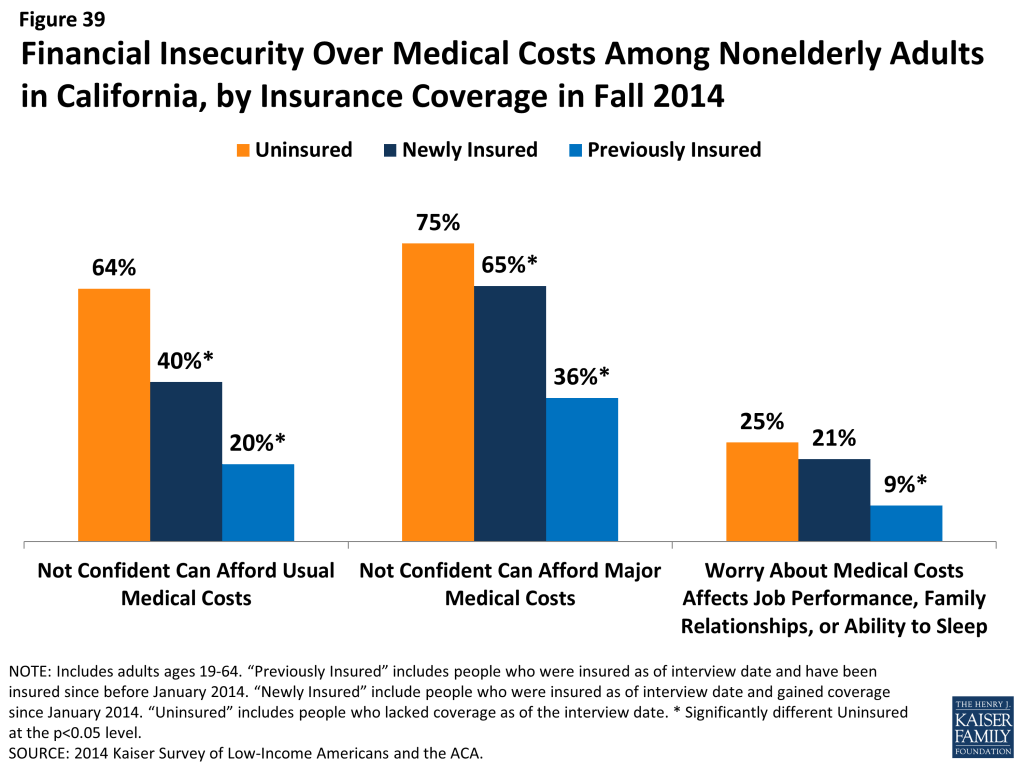

Many newly insured adults still face financial insecurity in areas outside of health care costs. While coverage provides some financial protection from medical bills, there were no significant differences in the share of uninsured and newly insured adults reporting difficulty paying for necessities, saving money, or paying off debt. Previously insured adults were less likely than uninsured to report these challenges.

Why are people still uninsured and what are their coverage options?

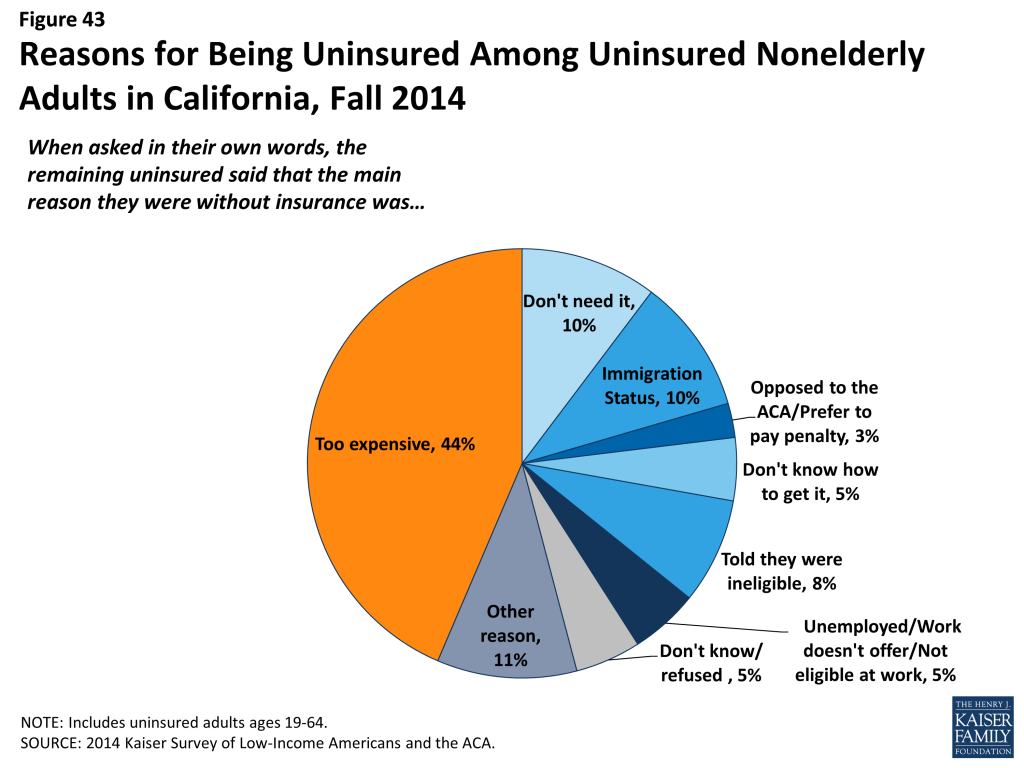

Though much attention was paid to the difficulties with the application and enrollment process during the 2014 open enrollment period, logistical issues were not a leading reason why people went without insurance in 2014. Rather, lack of awareness of new coverage options and financial assistance appear to be a major barrier.

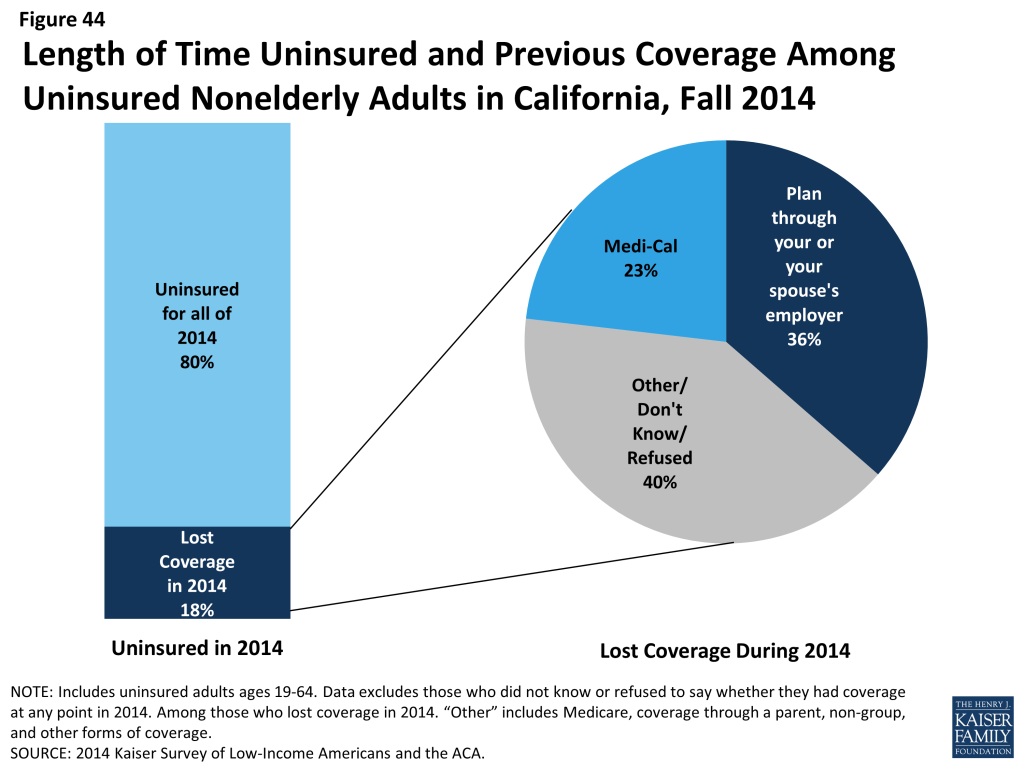

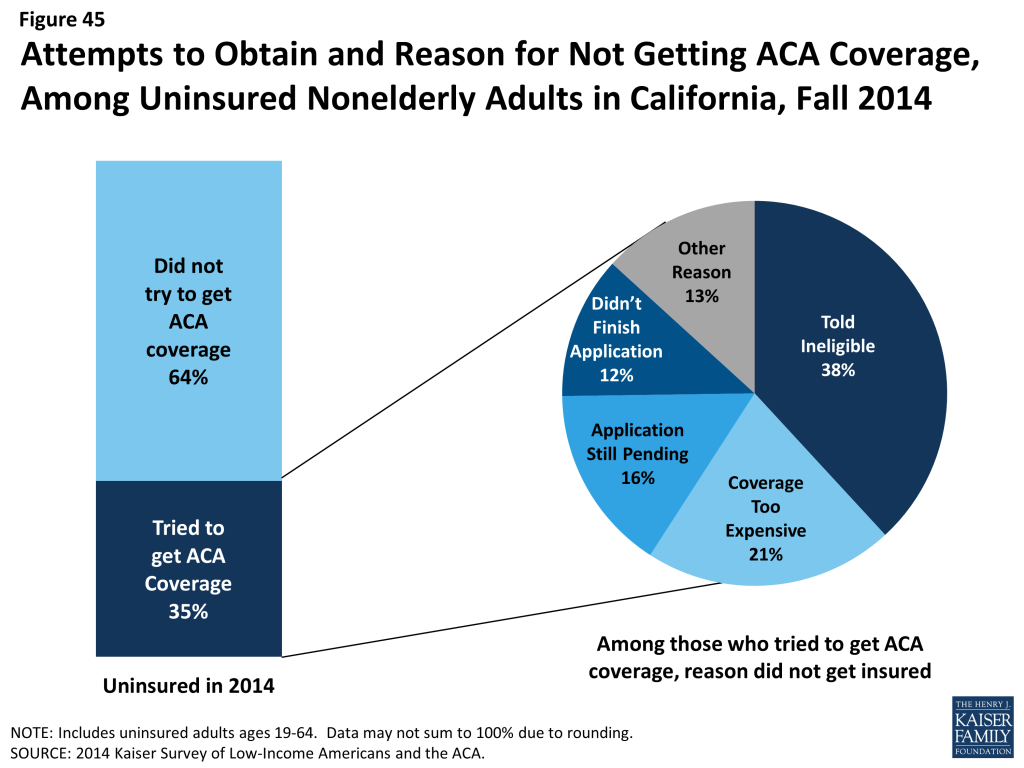

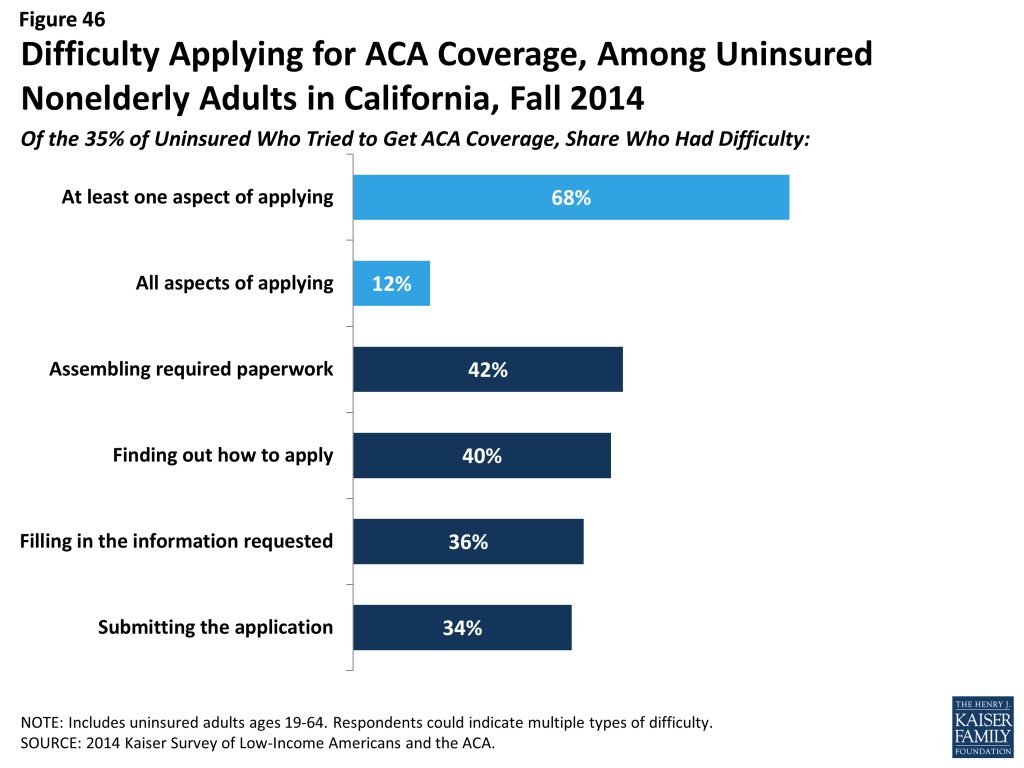

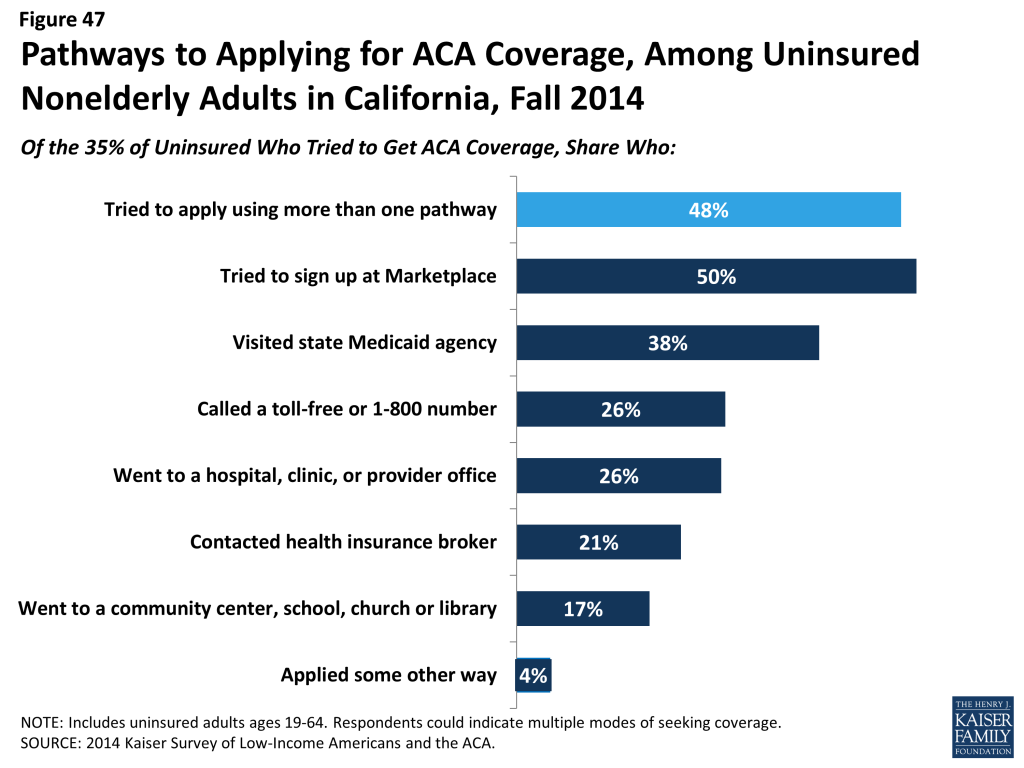

Most adults who were uninsured in fall 2014 had not tried to get ACA coverage, and perceptions of cost and eligibility were a common reason for not obtaining coverage. The main reason that all uninsured gave for why they lack coverage is that it is too expensive (44%). Among the roughly one-third of uninsured who tried to sign up for ACA coverage, the most common reason people gave for not having ACA coverage was being told they were ineligible (38%) or because it was too expensive (21%). Still, when asked directly about application difficulty, most uninsured adults who sought ACA coverage reported difficulty with at least one aspect of the process, and most tried more than one avenue.

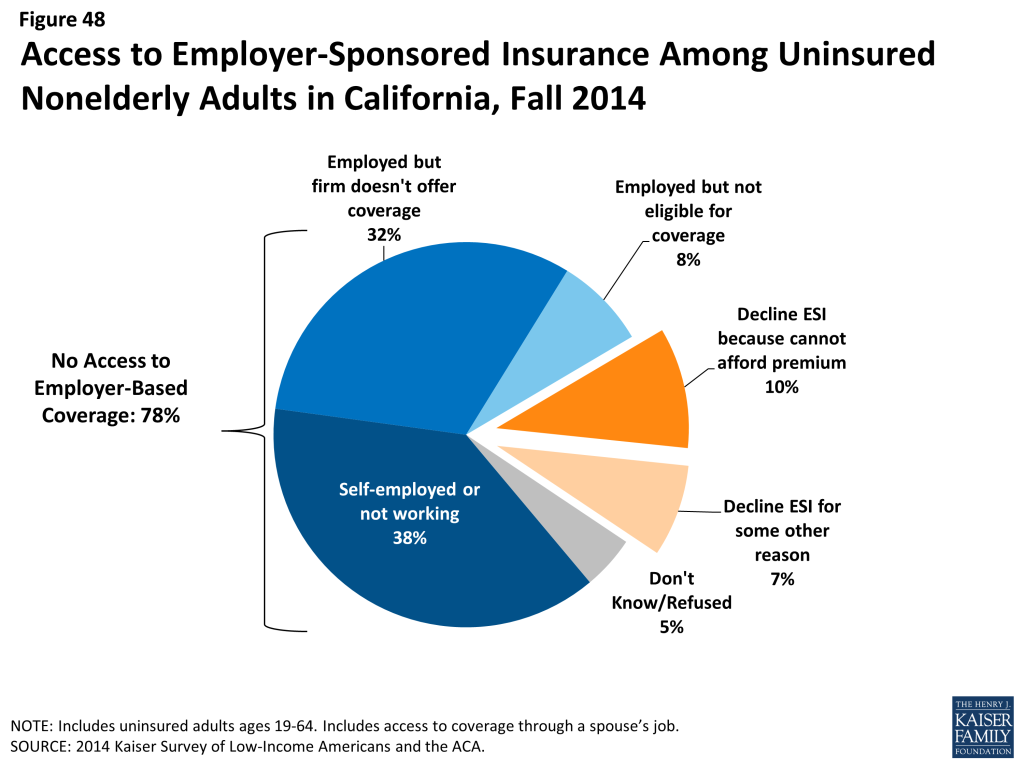

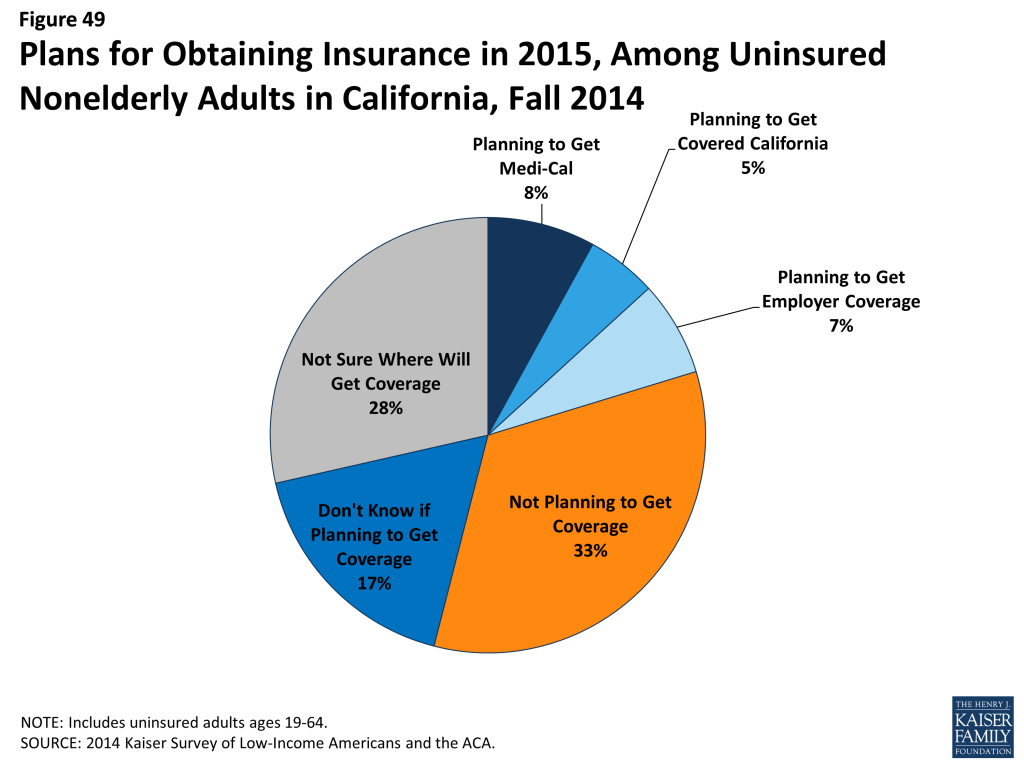

Few adults who were uninsured at the end of 2014 had plans to obtain ACA coverage in 2015. Only about half of uninsured adults indicated that they plan to get coverage in 2015, and few who do identified Medicaid or Marketplace coverage as their goal. Rather, higher shares indicate that they don’t know where they will get coverage or plan to get coverage through a job. However, few are likely to gain coverage through an employer either because they are self-employed or not in a working family (38%), or because the employer does not offer coverage (32%) or coverage for which they are eligible (8%).

Policy Implications

As we enter the second year of new coverage under the ACA, information on people’s experience during the first year can inform ongoing efforts to extend and improve health coverage in California.

Covering the Remaining Uninsured

Cost continues to prevent many uninsured adults from seeking coverage. While some uninsured adults are ineligible for assistance, most can receive some help under the law. Thus, there may be a continuing lack of awareness of new coverage options and financial assistance. Messages that focus on low-cost or free coverage being available to most uninsured may help address these barriers to seeking and obtaining coverage.

Given the high share of remaining uninsured who are Hispanic, targeted outreach to this group is appropriate. In the early stages of ACA implementation in the state, there was much attention to the Hispanic population but administrative barriers in reaching them. In 2015, the state made efforts to reach this population, resulting in higher enrollment among this population. Still, ongoing efforts are needed to enroll eligible Hispanics and to serve those who may be ineligible for coverage due to their immigration status.

Community outreach may help engage many remaining uninsured. A minority of uninsured adults who sought ACA coverage had contact with a provider, community group, or other outreach worker, and many hard-to-reach groups, such as young adults, immigrants, and people with limited English proficiency, require such one-on-one assistance. In 2015, outreach resources will shrink, making these efforts more difficult.

Providing needed services to the remaining uninsured

Clinics and health centers remain core providers for the uninsured and will require ongoing support to serve this population. Safety net providers are likely to play an important, ongoing role in serving the uninsured. However, experts note that these providers are also adapting to meet the changing health care environment, including becoming “providers of choice” to retain patients as they gain coverage.

While some uninsured are able to navigate the system when they need care, most are not and face serious consequences as a result. Experts noted that access to care for the uninsured varies by region within the state. Particularly in rural areas, provider shortages exist for both insured and uninsured people. In addition, not all counties provide services to the undocumented, and those that do vary greatly in the scope of these services. Since people will continue to lack coverage under the ACA, planned efforts to deliver services to the underserved may be necessary.

Improving care for the insured

While most adults with coverage have positive views and experience with their health plan across coverage type, consumer education about health insurance and health care may be needed. According to experts in the state, during outreach, assistors noted that many people appeared to not understand basic aspects of their health plan. While initial outreach efforts were focused on enrollment, education about coverage and health care is the next phase of bringing people into the health care system.

While coverage eases financial strain of health care, many newly insured adults are in precarious financial situations and still report affordability problems. While premium and cost-sharing subsides in Covered California are set at the federal level, continued attention to whether affordability measures are sufficient may provide insight into people’s take-up and use of new coverage.

Continued attention is needed to ensure those who have coverage are able to access care. Some newly insured adults still report access barriers. These barriers could be related to several factors, including network adequacy or difficulty finding a provider, problems navigating the health system and insurance networks, misunderstanding of how to use coverage and when to seek care, or concerns about out-of-pocket costs.

Introduction

In January 2014, the major coverage provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) went into full effect in California and across the country. These provisions include the creation of a new Health Insurance Marketplace, known in the state as Covered California, where middle income families (between around $27,000 and $79,000 for a family of three in 2014) can receive premium tax credits to purchase coverage and, in states like California that opted to expand their Medicaid program, the expansion of Medi-Cal eligibility to low-income adults (about $27,000 or less for a family of three in 2014). With these provisions, millions have gained coverage and access to needed health care services.

While much attention has been paid to enrollment in new coverage options and changes in the uninsured over the past year, less is known about how this coverage has affected people’s lives. To help fill this gap, the Kaiser Family Foundation is conducting a series of comprehensive surveys of the low and moderate-income population. These projects include both national surveys and a specific focus on California.

California is a bellwether state for understanding the impact of the ACA. Through a Medicaid waiver, the state was an early adopter of the Medicaid expansion, covering over 650,000 people by 2013 through its Low-Income Health Program (LIHP). The state was also the first to create a state-based Marketplace, and California engaged in an aggressive, multi-faceted outreach and enrollment campaign to reach and enroll individuals eligible for Medi-Cal or Covered California. The state’s efforts have led to substantial gains in coverage: Medi-Cal enrollment grew by 30% (2.8 million people) between the pre-open enrollment period in the fall of 2013 and the end of 2014,2 and roughly 1.7 million people applied and were determined eligible for Covered California health plans between October 2013 and October 2014.3 In addition, California’s sheer size means that the state’s experience in implementing the ACA has implications for national goals of reducing the total number of uninsured.

Findings from the 2013 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, fielded prior to the start of open enrollment for 2014 ACA coverage, provided a baseline snapshot of health insurance coverage, health care use and barriers to care, and financial security among insured and uninsured adults at the starting line of ACA implementation and discussed how those findings could inform early implementation.4 The 2013 survey included both a national sample and a California sample, funded by the Blue Shield of California Foundation. In fall 2014, we conducted a second wave of the Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA nationally and in California (again with support from the Blue Shield of California Foundation) to understand how these factors have changed under the first year of the law’s main coverage provisions. The survey, which included a state-representative sample of 4,555 nonelderly (age 19-64) California adults, was conducted between September 2 and December 15, 2014, with the majority of interviews (67%) conducted prior to November 15, 2014 (the start of open enrollment for 2015 Marketplace coverage; Medicaid enrollment is open throughout the year). In addition to the survey, qualitative interviews were conducted with key stakeholders throughout the state to provide policy context and insight into survey findings. Additional detail on the survey methods is available online.

This report, based on the California sample of the 2014 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA, examines the populations that gained coverage and remained uninsured in 2014. It describes the characteristics of these groups in California, comparing them to those who had coverage before 2014. It also provides information on how the newly insured view their coverage and any problems they have encountered in using their coverage; examines how the remaining uninsured and newly insured fare with respect to access to medical care and financial burden; and analyzes why people in California continue to lack coverage and their plans for obtaining coverage in 2015. Where relevant, the report also includes trended data from 2013.

Report: Background: Aca Implementation In California

As the nation’s most populous state, California faced a daunting challenge in expanding coverage under the ACA. Prior to ACA implementation, California had the largest number of uninsured of any state in the country. In 2010, when the ACA was passed, 6.8 million people in the state (or 18.5%) were uninsured,5 and California alone accounted for 14% of all uninsured people nationwide. Private coverage rates in the state were low due to a combination of high unemployment (which limited access to employer coverage) and high premium costs for non-group coverage6 (which made such coverage unaffordable for many). Public coverage through the state’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, was limited to only some groups of low-income adults, leaving many without an affordable coverage option. California is also a highly diverse state, with a majority of the population identifying as a race other than White7 and nearly half of residents speaking a language other than English in the home.8 Services for the uninsured in the state were largely devolved to California’s 58 counties, leading to variation in existing financing and availability of services for residents who lacked insurance coverage or regular care.

Leading up to full implementation of the ACA and during the first year of major coverage expansions, California actively pursued opportunities to expand coverage for residents, conducted outreach and enrollment to bring people into new coverage options, and organized systems to deliver care. While these efforts resulted in substantial coverage gains, the state—like all states—faced some early challenges under the ACA.

Early Implementation Efforts and Coverage Gains

California was one of a handful of states to undertake an early expansion of its Medicaid program in anticipation of full expansion in 2014. The state did so under its five-year “Bridge to Reform” §1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waiver, which was approved by the federal government in 2010. In addition to other provisions, the waiver allowed for federal matching funds for the creation of a county-based coverage expansion program for low-income adults not otherwise eligible for Medi-Cal, known as the Low Income Health Program (LIHP). The majority of counties participated in LIHP, and by the end of 2013, over 650,000 people were enrolled in the program.9 As discussed below, these individuals were either auto-enrolled in Medi-Cal or transferred to Covered California when these options became available in January 2014.10

LIHP also enacted innovative strategies to redesign the delivery of health care within California’s safety net system, including the development of robust provider networks and the integration of physical and behavioral health care, among others.11 As part of the “Bridge to Reform” waiver, California was also the first state in the country to adopt the Delivery System Reform Incentive Program (DSRIP) to assist California’s safety-net hospitals expand access to primary care, improve care and health outcomes, and increase efficiency.12

Even with the availability of coverage through LIHP, millions of Californians lacked coverage at the end of 2013. Some of these individuals are ineligible for assistance due to their immigration status (estimates revealed that about a fifth of uninsured California adults in 2013 were undocumented immigrants13 ), but many were likely eligible for Medi-Cal or Covered California subsidies. A majority of uninsured adults on the eve of full ACA implementation (52%) had family income below 138% of poverty, and most (71%) were either working themselves or had a spouse who worked. Compared to insured adults in the state, uninsured adults were more likely to be Hispanic and more likely to be young adults. These characteristics helped shape efforts to reach the eligible uninsured in 2014 and provide needed services to the ineligible population.

Medi-Cal Expansion and Covered California

As of January 2014, California expanded Medi-Cal statewide to cover low-income adults. In addition, subsidized coverage was available for moderate income adults who purchased insurance through the state’s health insurance marketplace, Covered California.

Under the Medi-Cal expansion, Medi-Cal was extended to all citizens and legal immigrants who have been in the country for over five years with income below 138% FPL ($16,105 for an individual or $27,210 for a family of three in 2014). Eligible lawfully residing immigrant pregnant women in this income range are exempt from the five year waiting period for coverage and can receive full-scope Medi-Cal14 and pregnant women with incomes between 109% and 208% FPL are eligible for Medi-Cal pregnancy-only coverage.15 Income-eligible legal immigrants who have been in the country less than five years became eligible for full-scope, state-only funded Medi-Cal beginning in January 2014 and were scheduled to transition to Covered California in January 2015;16 however, this transition has been delayed.17 When the transition takes place, these individuals will receive an affordability wraparound, ensuring that premiums, out-of-pocket costs, and covered services are the same as if they were enrolled in Medi-Cal. Undocumented immigrants who satisfy the income and residency requirements are eligible for limited scope Medi-Cal benefits, including emergency room services, long-term care, kidney dialysis, and prenatal care.18

California operates its own insurance marketplace, known as “Covered California,” as an independent public agency. Through Covered California, individuals who do not have access to another source of affordable coverage are eligible to purchase individual coverage directly from insurers. People with incomes between 139% and 400% of poverty are eligible for premium tax credits, and people with incomes between 139 and 250% of poverty are also eligible for cost-sharing subsidies. In addition, small businesses (up to 50 workers) can offer coverage to their workers via Covered California’s Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP). Legal, permanent residents who have been living in the country for less than five years may purchase health insurance through Covered California and may receive subsidies. Undocumented immigrants are prohibited from purchasing insurance in the Marketplace. Statewide, the average premium rate for the lowest Bronze plan was $219 per month in 2014 and $304 per month for the lowest cost silver plan.19

Covered California received federal funding to create a single online portal, available in Spanish and English, where users can apply and receive eligibility determinations for Medi-Cal or Marketplace insurance. The application can also be completed in-person, by phone, fax or mail, and paper applications are available in thirteen languages. In addition, individuals may continue to apply for Medi-Cal through their county Medi-Cal office. Covered California’s online application system, also known as the California Health Care Eligibility, Enrollment and Retention System (CalHEERs), coordinates with counties’ social services department through an online system called Statewide Automated Welfare Systems (SAWS).

On October 1, 2013, individuals and small businesses could begin shopping for health insurance plans. Coverage purchased through Covered California and coverage under the Medi-Cal expansion started in January 2014. Individuals who had gained coverage under the early LIHP expansion were auto-enrolled in coverage. Specifically, roughly 630,000 LIHP members were auto-enrolled in Medi-Cal, and an additional 25,000 were transitioned into Covered California.20 Open enrollment for Covered California ended on March 15, 2014 (though applications in progress were granted an extension21 ), while Medi-Cal enrollment was open throughout the year.

Outreach and Enrollment Throughout 2014

Leading up to and throughout ACA implementation, the state invested heavily in outreach and enrollment efforts for both Medi-Cal and Covered California. These efforts included statewide marketing campaigns, community mobilization, provider training, and targeted efforts to reach vulnerable populations who may be newly-eligible for coverage. Covered California also established an Assisters Program and worked with community organizations to provide direct assistance to consumers to help them enroll in coverage. In addition, the state received extensive federal funds and funds from private foundations, including $23 million from the California Endowment,22 most of which were distributed to localities, for local outreach efforts. These local outreach efforts included (among other things) support for Medi-Cal Certified Enrollment Counselors, outreach to hard-to-reach populations, and marketing to increase awareness and understanding of new coverage options.23 , 24 , 25 Experts believe that the local efforts to enroll eligible individuals were a key factor in driving high enrollment rates. In addition, 125 health centers operating over 1,000 sites throughout the state received federal grants to help with outreach and enrollment assistance,26 and experts noted that these providers were also crucial to enrollment efforts.

Alongside its extensive outreach efforts, California also took various steps to simplify and streamline enrollment. In addition to transitioning people from LIHP to Medi-Cal, the state also uses Hospital Presumptive Eligibility (PE) and adopted the Express Lane Enrollment Project. Under the PE program, hospitals can assist patients who are receiving services in the hospital in applying for temporary Medi-Cal benefits, producing an immediate eligibility determination based on the information provided in the application.27 The Express Lane Enrollment Project targeted adults and children enrolled in CalFresh, California’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Through a waiver the state was able to use CalFresh income eligibility to grant Medi-Cal eligibility to CalFresh enrollees without the need for an application or a determination for 12 months.28

Despite all these efforts, the state experienced some challenges in enrollment in 2014. Organizations and individuals encountered challenges with the Covered California in-person assister training process, including an insufficient number of training sessions, which led to a shortage of Certified Enrollment Counselors (CECs).29 In addition, educators and enrollment counselors cited problems with cultural and linguistic resources, including poorly translated materials that left many people confused, and a shortage of linguistically-appropriate materials.30 Some of these issues were addressed toward the end of open-enrollment and leading up to the second enrollment period, which began in the fall of 2014.31 In particular, Covered California made improvements to its Spanish-language website, added more bi-lingual employees and held community events in areas with large Latino populations.

In addition, though people began applying for coverage on October 1, 2013, the interface between CalHEERS and SAWS was not functional until late January 2014,32 thus delaying the enrollment process for consumers and health plans. A combination of technological issues as well as pending documentation on the part of applicants resulted in a Medi-Cal backlog of approximately 900,000 applications by May of 2014. The agency did its best to work through these applications; however, as recently as February of 2015, roughly 45,000 applications were still awaiting eligibility determinations and had gone unanswered.33

The Covered California website also contained small technical glitches across both the English and Spanish versions of the site that sometimes made navigating the site difficult or impossible. For example, the site would shut down while undergoing updates. Consumers and counselors reported long waits when seeking assistance through Covered California’s telephone hotlines, and counselors reported dropped calls while waiting to be transferred to multilingual call center representatives.34 The agency received criticism for not offering the Spanish-language paper applications until half-way through open-enrollment, posing a problem for users who did not have access to high-speed internet.35

These challenges notwithstanding, the state enrolled unexpectedly large numbers of people in 2014. By October 2014, nearly 1.7 million people applied and were determined eligible for Covered California health plans, doubling base projections of 816,00036 and representing about half of the marketplace-eligible population.37 The vast majority (83%) of people who enrolled received financial assistance (compared to 85% nationally).38 Los Angeles County alone accounted for over 400,000 enrollees.39 More than half of all enrollees into Covered California received enrollment help from a Certified Insurance Agents (36%), Certified Enrollment Counselor (8%), Service Center Representatives (10%), or other assister or navigator.40 Though ten health insurance companies offered plans in the Marketplace, the vast majority of people in Covered California chose a plan offered by one of the state’s four largest insurers—Anthem, Blue Shield of California, Kaiser Permanente or Health Net.41

Enrollment in the Medi-Cal program grew by 30%, or 2.8 million people, between October 2013 and the end of 2014.42 Of the approximately 1.9 million who enrolled in Medi-Cal between October 2013 and the end of the open enrollment period (March 15, 2014), 1 million applied through the Covered California portal and county offices, 630,000 transitioned from LIHP, and 180,000 applied through the state’s Express Lane Program.43 While some enrollees may have been eligible for Medi-Cal before the ACA, more than half (59%) are likely newly-eligible under the expansion.44

Despite the various challenges, California made substantial gains in reaching and enrolling millions of people throughout the state during the first year of coverage expansions under the ACA. In 2015, the state is building on these gains and addressing many of the issues that arose in the first year.

Report: Who Gained Coverage And Who Remained Uninsured?

In many ways, the “newly insured” population (those who gained coverage in 2014 and were uninsured before gaining that coverage) and “remaining uninsured” population (those who lacked coverage in fall 2014) resemble each other. For example, they are similar with respect to income, age, and health status, and they have different characteristics from the “previously insured” population (people who had coverage before 2014 and still had it in 2014). These patterns likely reflect the characteristics of the population that has historically lacked coverage. However, the insured and uninsured populations in California differ on some important factors, such as race/ethnicity, work status, gender, immigration status, and family status. These differences are important to understanding who was left out of coverage expansions in 2014 and targeting ongoing outreach to the remaining uninsured.

More than half of the newly insured and remaining uninsured populations have family income at or below 138% of poverty, the income range for the Medicaid expansion. As was the case before 2014,45 more than half of uninsured adults (51%) have family incomes at or below 138% of poverty, or about $27,000 for a family of three. Over a third (35%) has family incomes in the range for tax credits (139 to 400% of poverty). This distribution is similar to the newly insured population, the vast majority of whom (94%) had incomes in the range for financial assistance under the ACA. In contrast, the previously insured population is significantly less likely than either the uninsured or newly insured to be low-income and significantly more likely to be higher income (greater than 400% of poverty). This pattern reflects the longstanding association between having low income and lacking insurance coverage. Provisions in the ACA aim to make coverage more affordable for low and middle-income families.

A majority of both the remaining uninsured and newly insured are in a family with at least one worker. Nearly three quarters of uninsured adults are in a family in which either they or their spouse is working, a pattern that has held since before the ACA.46 More than half (52%) are in a family with a full-time worker. While there is no difference in the share of newly insured adults in a working family overall, newly insured adults are less likely than remaining uninsured adults to be in a family with a full-time worker. Those who have been insured since before 2014 are more likely to have a full-time worker and less likely to have a part-time worker in the family. These patterns reflect the historical ties between work and health insurance, since most people who had coverage before the ACA obtained that coverage through a job. With new coverage provisions in place as of 2014, there were more options for health insurance outside employment, and groups traditionally left out of the employer based system—such as part-time workers or low-wage workers—had new avenues for coverage.

Hispanics are disproportionately represented among the remaining uninsured population. Reflecting historical patterns of the uninsured being more likely to be people of color than the insured,47 the remaining uninsured and the newly insured are both more likely than the previously insured to be Hispanic and less likely to be White. However, the remaining uninsured population is more likely to be Hispanic than either the newly insured or previously insured population: 54% of the remaining uninsured population is Hispanic, a share significantly higher than among the newly insured or previously insured. This pattern likely reflects a combination of factors, including language barriers and immigration policy. Experts believe that lower enrollment among Hispanics may be related to the delay in having accurate Spanish-language enrollment materials.48 Another notable barrier was fear among some mixed-immigration status families that applying for coverage for eligible family members may expose other family members to risk of deportation. Last, the higher share of remaining uninsured who are Hispanic may reflect eligibility limits based on immigration status.

The newly insured population is more likely to be female than their counterparts who remained without coverage. More than half (56%) of the newly insured population is female, a share significantly higher than that among the remaining uninsured (41%) but not significantly different from the previously insured. This pattern may reflect different take-up rates between men and women: Compared to 2013, the uninsured population in 2014 is more likely to be male.49 Women have historically had a lower uninsured rate than men, and the gender patterns in who gained coverage in California may reflect this historical and national pattern.50

The remaining uninsured population is of similar age distribution as adults who gained coverage in 2014. While many were concerned that younger adults would disproportionately opt not to enroll in coverage, the share of uninsured and newly insured who were young adults (age 19-25) were about the same, and the share of the uninsured who were young adults in 2014 was the same as in 2013.51 However, both the uninsured and the newly insured populations were younger than the group of adults who were previously insured. About a fifth of the uninsured (21%) and newly insured (22%) populations were young adults, ages 19 through 25, compared to just 13 percent of the previously insured. About half of the uninsured and about half of the newly insured were under age 35, compared to just 31 percent of the continuously insured. This pattern reflects the fact that those who lacked coverage prior to 2014 were more likely to be young, since younger adults have looser ties to employment and lower incomes.

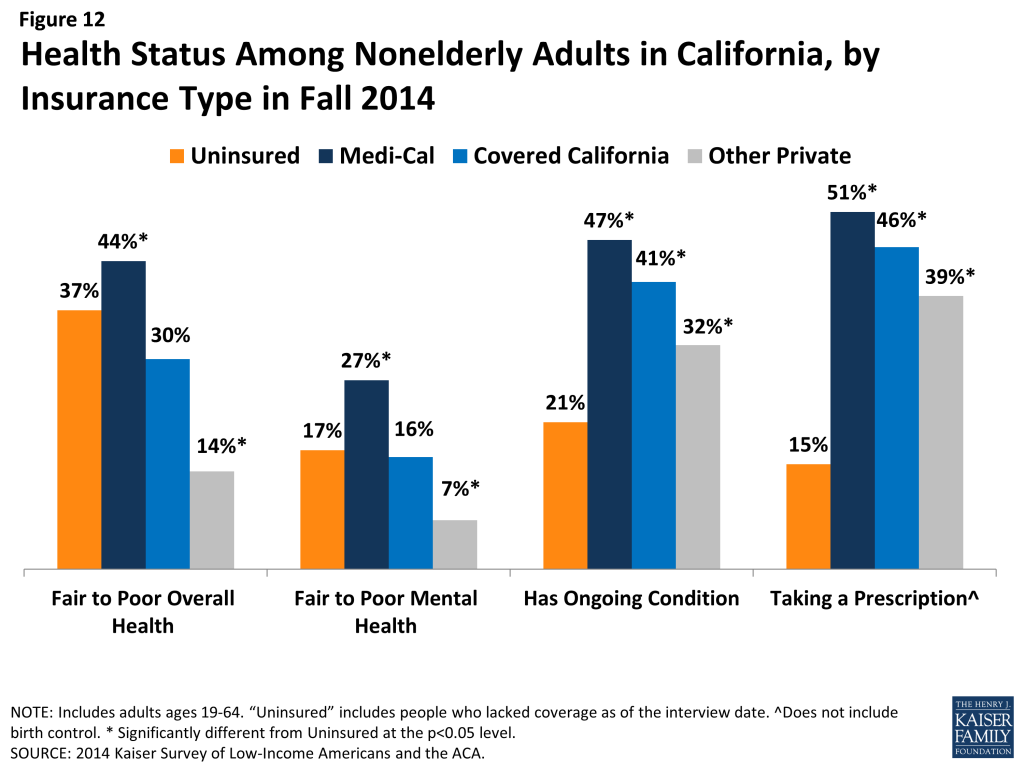

While there are no significant differences in the share of uninsured and newly insured adults who say their health is fair or poor, uninsured adults are less likely than adults with coverage to have a diagnosed medical condition. Compared to 2013, the uninsured in 2014 have a similar health profile;52 more than a third of uninsured adults (37%) and 30% of newly insured adults rate their overall health as fair or poor, in contrast to just 20% of previously insured adults. About a fifth (17% or uninsured and 23% of newly insured) report their mental health is fair or poor, compared to just 11% of the previously insured. However, the remaining uninsured are less likely than either the newly insured or previously insured to report being under care for a chronic condition: Insured adults are more likely than the uninsured to say that they have an ongoing medical condition that requires regular care, and both newly insured and previously insured adults are more likely than the uninsured to say they take a prescription on a regular basis. Comparing the newly insured and previously insured populations reveals that the previously insured are less likely to report fair/poor physical or mental health and are more likely to take a prescription. These patterns may reflect the fact that uninsured individuals are more likely than insured to have undiagnosed illnesses,53 and people with stable insurance coverage are more likely to receive regular and specialty care.54

Report: Who Is Covered By Different Programs In California?

Understanding the profile of the population covered by different types of insurance in the state is essential to designing effective health plans to serve their needs. Historically, the adult population served by Medicaid was primarily made up of parents with very low incomes, individuals with disabilities, and pregnant women. With the expansion of Medi-Cal, the program grew to include individuals not traditionally covered by the program (such as non-disabled, non-parents), which has changed the profile of the overall program somewhat. However, given that new enrollment built off a much larger base, Medi-Cal retains many of its traditional roles of serving many individuals with substantial needs. The profile of Covered California enrollees shows that the program is playing an essential role in covering groups that have been left out of coverage expansions in the past.

Medi-Cal and Covered California enrollees are more racially diverse than the group of Californians with other private coverage. As in the past, a majority (two-thirds) of Medi-Cal enrollees identify as a person of color: 41% are Hispanic, 9% are Black, and 16% identify as Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, or other race. Covered California enrollees are also racially diverse, with 60% identifying as a race/ethnicity other than white, 37% of whom are Hispanic. In contrast, about half of adults with other private coverage in the state are White, non-Hispanic. This diversity indicates the need for these programs to design culturally-appropriate outreach and enrollment materials and to be sensitive to cultural issues in designing coverage and provider networks. It also highlights the importance of these programs for addressing long-standing disparities in health coverage and access for minority populations.

Medi-Cal enrollees are more likely to be female than adults with other types of coverage. Whereas about half of adults with Covered California or other private coverage are female, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults covered by Medi-Cal are female, a share equivalent to that in 2013.55 This difference may reflect pre-ACA eligibility restrictions for Medi-Cal, which limited adult coverage to custodial parents, pregnant women, and individuals with disabilities.

The adult Medi-Cal population is younger than that of other coverage groups, particularly Covered California enrollees. Forty percent of adult Medi-Cal enrollees are under age 34, compared to about a third of adults in Covered California or with other private coverage. Since 2013, the share of adults covered by Medi-Cal who are under age 34 has increased.56 This pattern may reflect income, since younger adults have looser ties to employment and thus lower incomes. Notably, more than half of adults enrolled in Covered California are over age 45, an age at which obtaining non-group coverage outside the Marketplace or without financial assistance could be difficult or costly.

A majority of adult enrollees in both Medi-Cal and Covered California are adults without dependent children, a group that has generally been excluded from publicly-financed health coverage in the past. More than six in ten (62%) adult Medi-Cal enrollees and more than seven in ten (72%) adult Covered California enrollees do not have dependent children. In the past, adults without dependent children could only qualify for Medi-Cal if they were disabled or pregnant, though many non-parent adults gained LIHP coverage before 2014. Adults with other private coverage in 2014 were most likely to be married, perhaps reflecting the availability of family coverage in the private market.

About half of Medi-Cal and nearly three-quarters of Covered California adults are in a working family. Because Medi-Cal is designed to reach people at the lowest end of the income spectrum, it is not surprising that a smaller share of adults covered by the program is in a working family than that for other types of coverage. About a quarter (26%) of Medi-Cal adults are either working full-time or have a spouse who works full-time, and about a fifth (19%) are working part-time or have a spouse who works part-time. Given these individuals’ low incomes, they are likely working in jobs that pay low wages, and they are unlikely to have access to coverage through their job. Notably, the share of adults with Medi-Cal coverage who are in a working family increased significantly between 2013 and 2014,57 reflecting both new eligibility pathways for working adults and the improving economy. A larger share of adults in Covered California are in a family with a full-time (49%) or part-time (23%) worker; to meet eligibility for subsidized coverage, these individuals do not have access to affordable coverage through a job. Not surprisingly, most people with other private coverage are working.

Reflecting Medi-Cal’s role in caring for people with substantial health needs, Medi-Cal enrollees have poorer health status than adults with other types of coverage. Medi-Cal beneficiaries were more likely than adults with other types of coverage to say their physical health or mental health was fair or poor; they were also more likely to have an ongoing health condition or be taking a prescription on a regular basis. As Medi-Cal’s scope has expanded under the ACA, the share who report health problems has declined significantly.58 Covered California adults were more likely to have health problems than adults with private health coverage; many of these adults were uninsured before gaining coverage and may have health problems that accumulated while they lacked coverage.

Report: What Has Happened To Access To Care For The Insured And Remaining Uninsured?

The ultimate goal of expanding health insurance coverage is to help people access the medical services that they need. A large body of literature has documented that people with insurance are more likely to be linked to regular care, are less likely to postpone care when they need it, and have an easier time accessing services. The survey findings reinforce those findings, indicating that adults who gained coverage in 2014 have better access to care than those who remained without coverage. In addition, the survey findings provide insight into patterns of care among the newly insured and remaining uninsured. While some newly insured adults changed where they regularly go for care, many continue to seek services from community clinics and health centers, which have historically served under-served populations such as the uninsured.

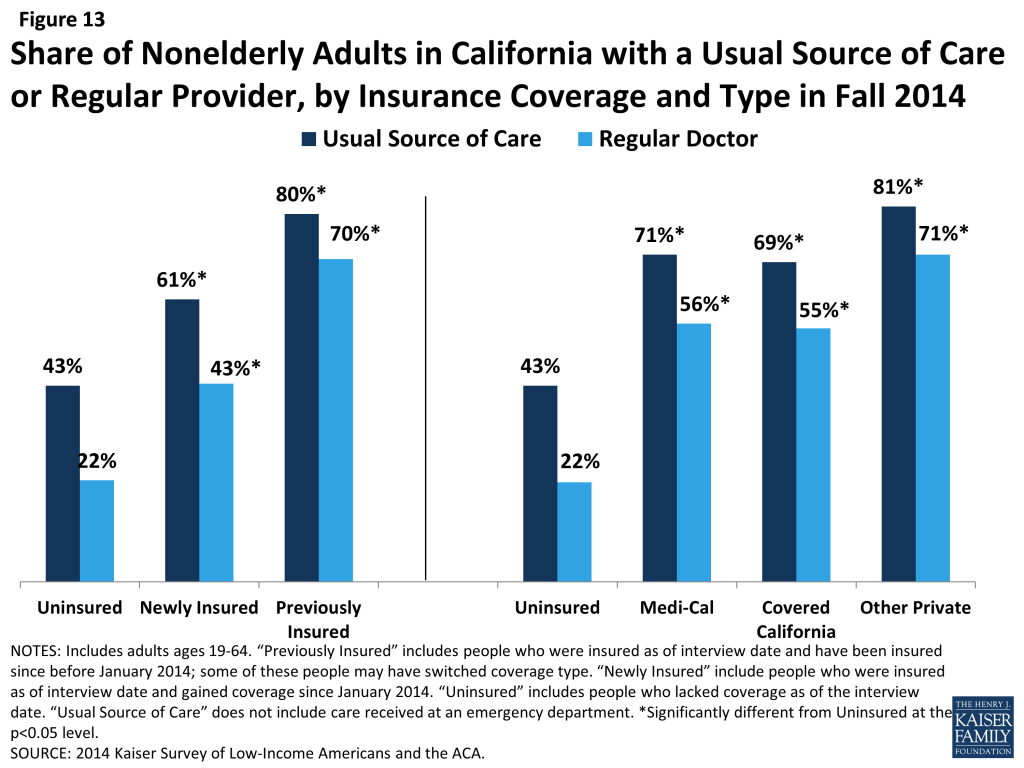

Adults who gained coverage are more likely to be linked to care than those who remained uninsured. Newly insured adults were more likely than those who remained uninsured in fall 2014 to have a usual source of care, or a place to go when they are sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room); they were also more likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care. Previously insured adults were also more likely than the uninsured to have a regular site of care and regular provider. These findings hold across coverage type. Having a usual source of care or regular doctor is an indicator of being linked to the health care system and having regular access to services. These patterns reinforce a large body of research that finds that gaining coverage is associated with improved access to care. However, results also indicate that the newly insured are less likely than the previously insured to have a usual source of care or regular doctor. This finding may indicate that newly insured adults are still navigating the health care system and are not as settled into regular care as their previously insured counterparts. Compared to 2013, there was no change in the share of Medi-Cal enrollees who reported having a usual source of care or regular doctor, while uninsured adults in 2014 were less likely than those in 2013 to say they have a usual source of care (but not a regular doctor).59

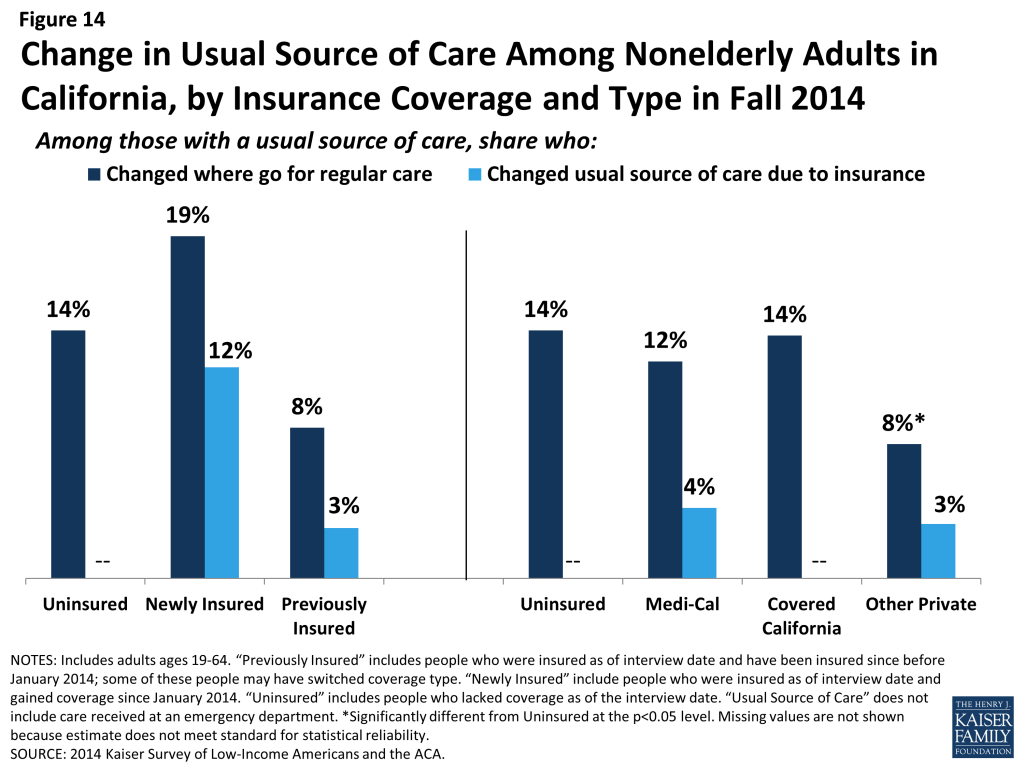

Newly insured adults were more likely to change where they usually go for care than their previously insured counterparts. Nearly a fifth (19%) of newly insured adults who have a usual source of care reported that they changed the place they usually go for care since gaining their coverage. Uninsured adults in 2014 were not significantly more likely to say they changed their usual source of care compared to uninsured adults in 2013, and there were no significant differences between the rates of uninsured and newly insured adults changing their usual source of care in 2014. However, newly insured adults in 2014 were more likely than previously insured adults to change their usual source of care. Most newly insured adults who changed their site of care reported that it was due to their insurance, a significantly higher rate than the previously insured. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of Medi-Cal or Covered California enrollees changing their usual source of care, and Medi-Cal enrollees in 2014 were no more likely than those in 2013 to say they changed where they usually go for care.

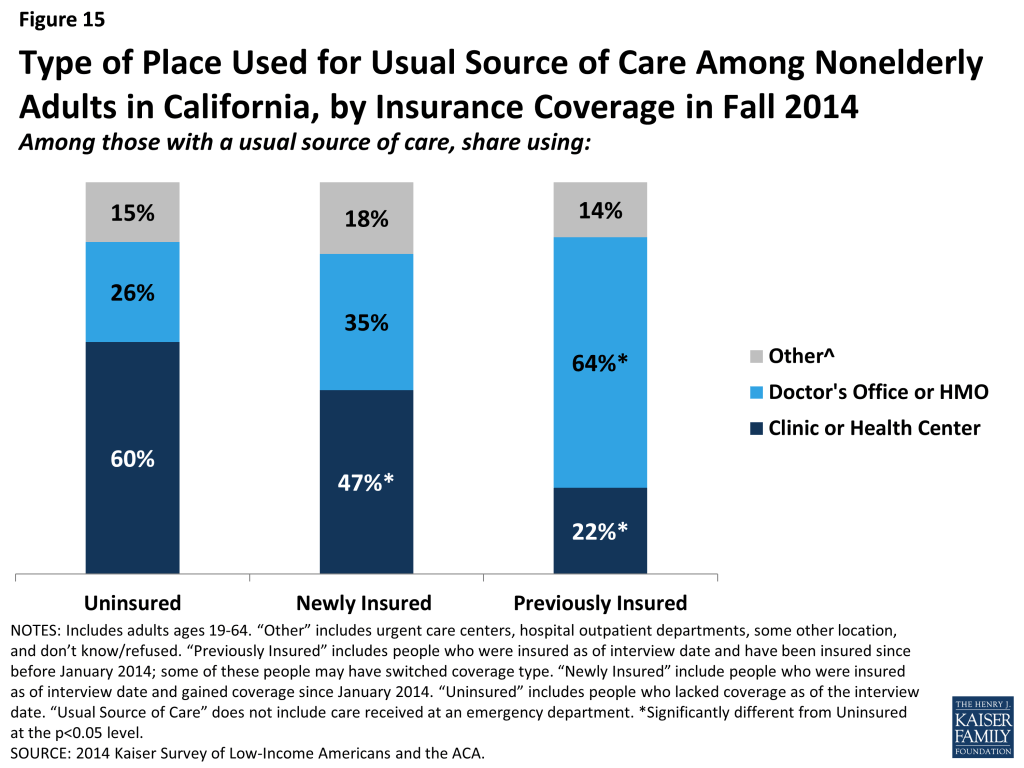

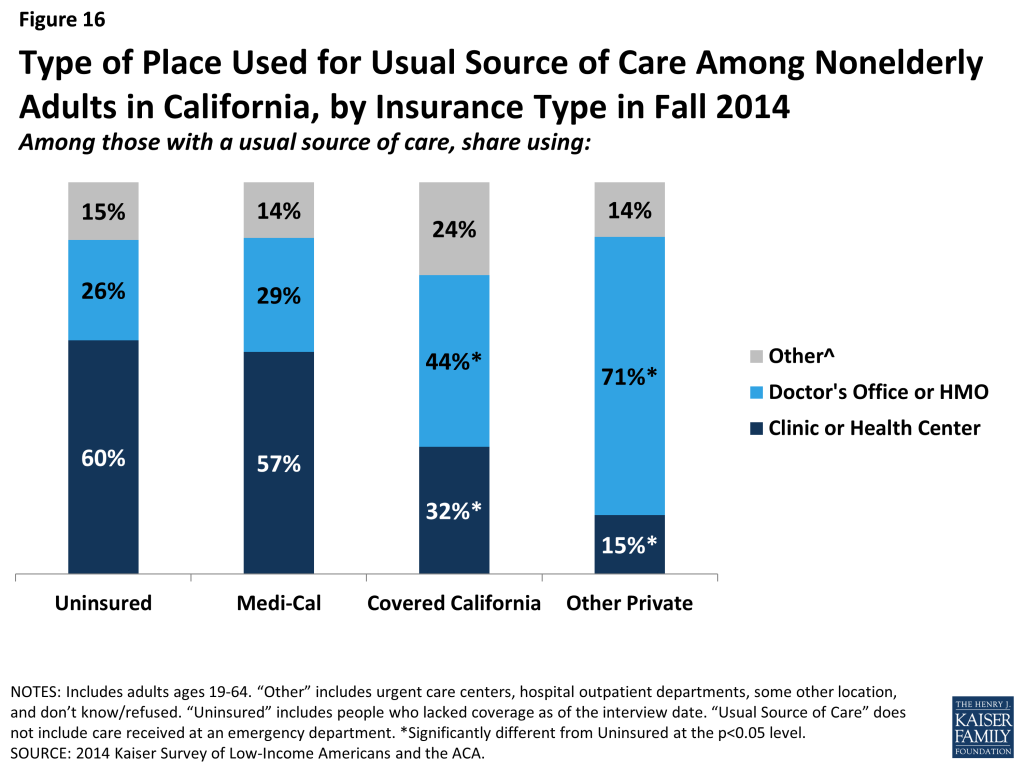

Clinics remain an important source of care for both the uninsured and the newly insured. Both uninsured and newly insured adults with a usual source of care are most likely to use a clinic or health center for that care. In contrast, previously insured adults were most likely to use a doctor’s office or HMO as their usual source of care. Historically, clinics and health centers were crucial “safety net” providers for uninsured people, and the share of uninsured adults using clinics as their usual source of care was unchanged since 2013. Though some of the newly insured have changed their source of care, many continue to rely on these providers. Experts in the state note that this pattern could reflect community health centers’ efforts to retain patients after helping them enroll in health coverage or patient preferences for these providers, which have a strong tradition and mission of culturally competent care and community environments. According to policy experts from county health systems, this pattern also may reflect lack of understanding of new health care options amongthe newly insured.

Comparing site of care by type of coverage reveals that those enrolled in Covered California (44%) or other private coverage (71%) were more likely than Medi-Cal enrollees (29%) to choose a doctor’s office as their usual source of care, with adults with other private coverage most likely to do so. Medi-Cal enrollees were most likely to use clinics or health centers for their usual care (57%). This pattern is in line with pre-ACA patterns, which showed that a plurality of adults with Medi-Cal used clinics or health centers for their regular care.60 Comparing the 2013 and 2014 surveys indicates that a significantly larger share of Medi-Cal adults with a usual source of care is relying on clinics. This change could indicate that, as uninsured adults gain Medi-Cal coverage, they still use the clinics and health centers that they relied on when they were uninsured.

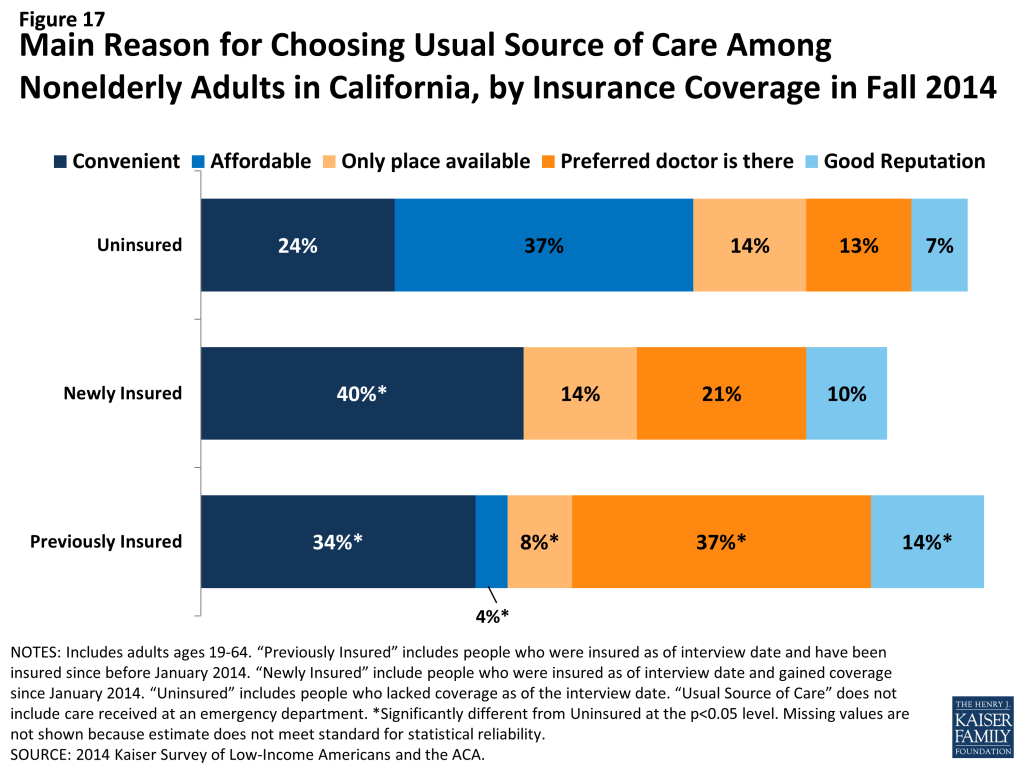

Uninsured adults are most likely to choose their site of care based on affordability, whereas newly insured adults are most likely to choose based on convenience. In the past, many uninsured adults reported that they chose their usual source of care because it was affordable, a pattern that is also seen among adults who were uninsured in 2014. More than a third (37%) of uninsured adults say they use their usual source of care because it is affordable, a share not significantly different than the uninsured in 2013 reported. In contrast, adults who gained coverage in 2014 were more likely to say they chose their usual source of care because it was convenient (40%). Previously insured adults were most likely to choose their site of care because their preferred provider is there (37%). As the newly insured establish relationships with a regular doctor at their usual source of care, it is possible that they too will begin to seek out routine care at a place where their preferred doctor is available.

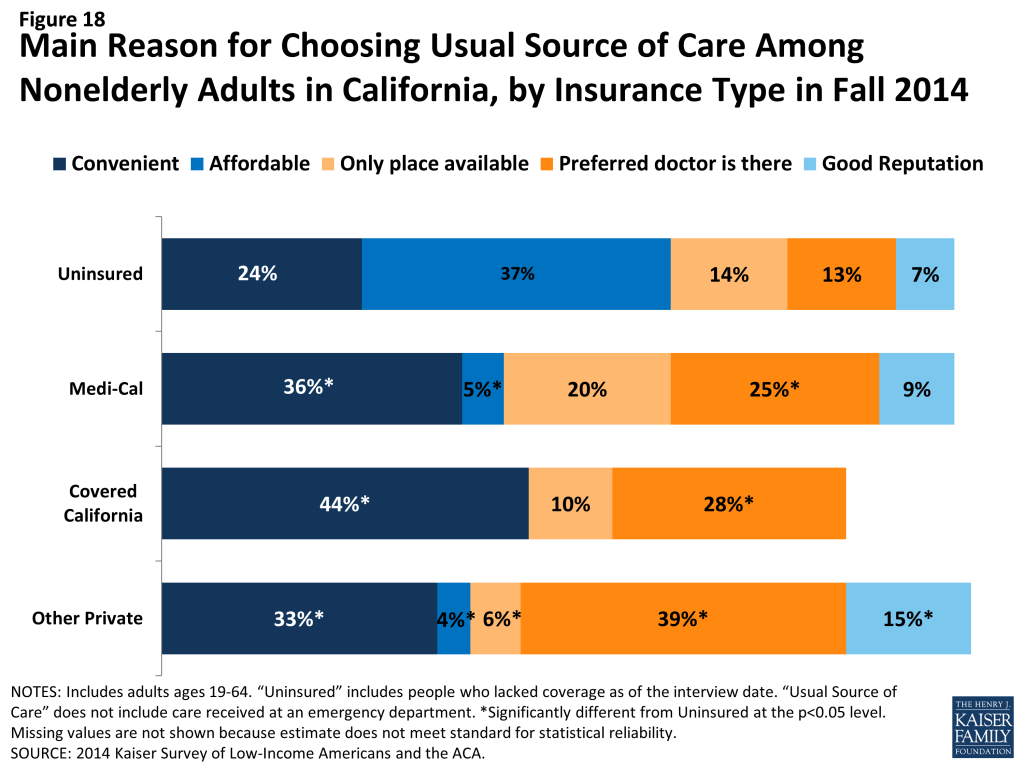

Looking at reason for choosing site of care by coverage, Medi-Cal enrollees were more likely than those in Covered California and other private insurance to report choosing their usual source of care because it was the only place available. Ten percent of Covered California enrollees reported choosing their usual source of care because it was the only place available, compared with 20% of Medi-Cal enrollees and 6% of those with other private insurance. Though Medi-Cal managed care plans are held to state standards of network adequacy and patient access, experts report that low reimbursement rates make contracting with providers difficult, especially in rural areas. There was no change from 2013 to 2014 in the share of Medi-Cal enrollees who reported they chose their usual source of care because it is the only place available. According to a state Medicaid expert, long-standing federal and state standards of network adequacy have required managed care plans to grow their network to meet demand in the past and will continue to do so as needed.

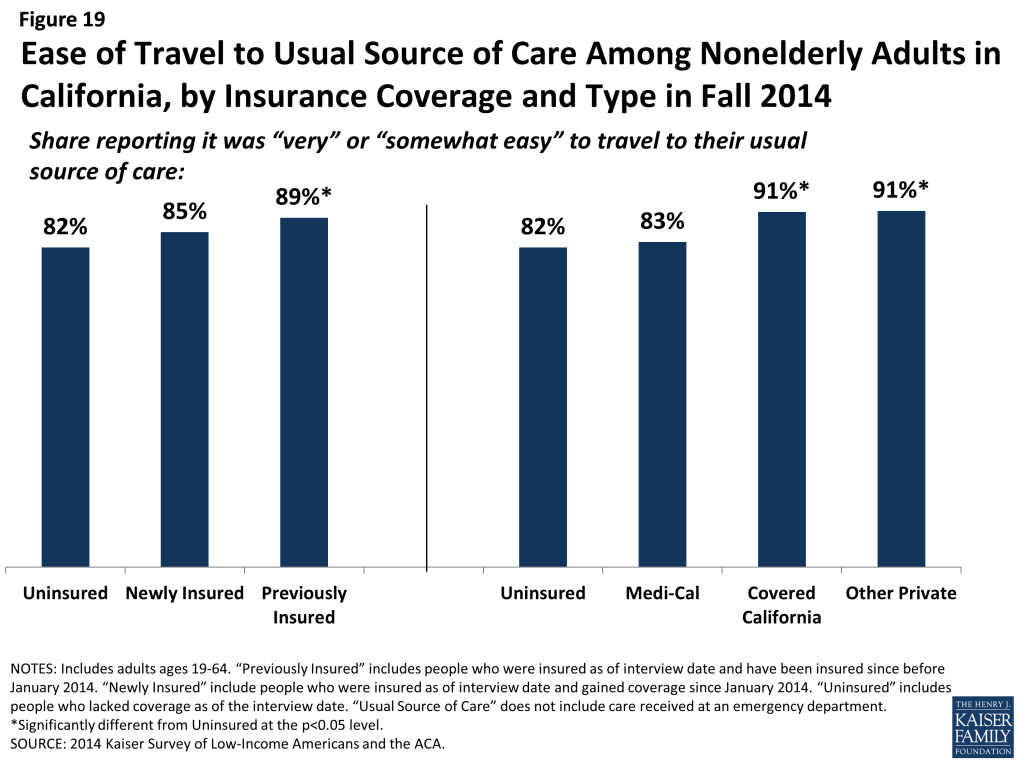

Uninsured adults and newly insured adults report greater difficulty than previously insured adults in traveling to their regular site of care. Among adults with a usual source of care, most report that it is “very easy” or “somewhat easy” to travel there. However, there was no significant difference in the share of newly insured and uninsured adults who reported ease in traveling to care, while previously insured adults were more likely than uninsured to report ease of traveling to care. Within types of coverage, adults with Covered California and other private coverage were more likely than the uninsured to say it was easy to travel to care. These patterns may reflect the need for the uninsured to find a source of care that is affordable, which may require farther travel. In addition, those with private coverage were also more likely than those with Medi-Cal to report ease of travel to their usual source of care. Taken together, these findings also suggest that the difference may be due to lower provider density in areas where those with the lowest incomes live or the need for lower-income people to rely more heavily on public transit than their own vehicle. There was no change from 2013 to 2014 in the share of uninsured or Medi-Cal enrollees reporting difficulty traveling to their usual source of care.

Mirroring patterns for being linked to care, adults with insurance coverage were more likely than the uninsured to have used medical services or received preventive care. More than half (58%) of adults who gained coverage in 2014 said that they used at least one medical service since gaining their coverage, and nearly half (47%) had received a preventive visit or check-up. These rates were significantly higher than those the uninsured reported for 2014 but were lower than the previously insured reported for 2014. There were no differences in the share of adults reporting visits by coverage type, with the exception of adults with other private coverage being more likely than adults with Medi-Cal to have a preventive visit. Again, these findings are not unexpected given the large body of research showing that people without insurance coverage are less likely to use care, including preventive care. Compared to 2013, Medi-Cal beneficiaries were less likely to report using care but no more or less likely to report using preventive care. Among uninsured adults, there were no changes in utilization rates between 2013 and 2014.

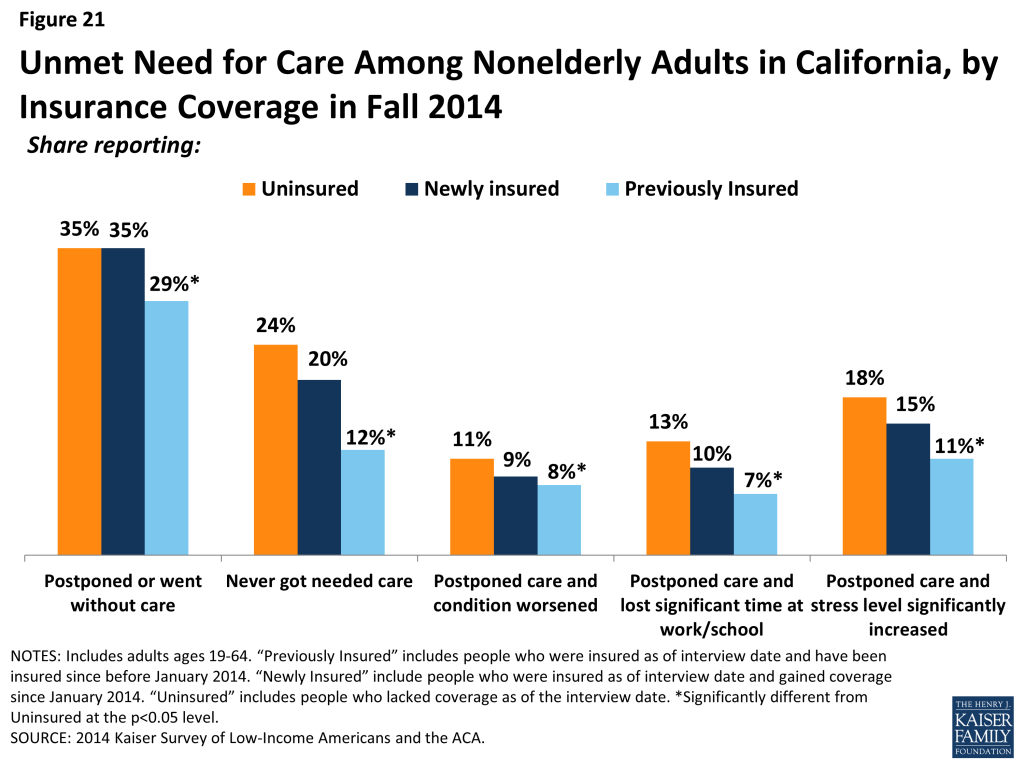

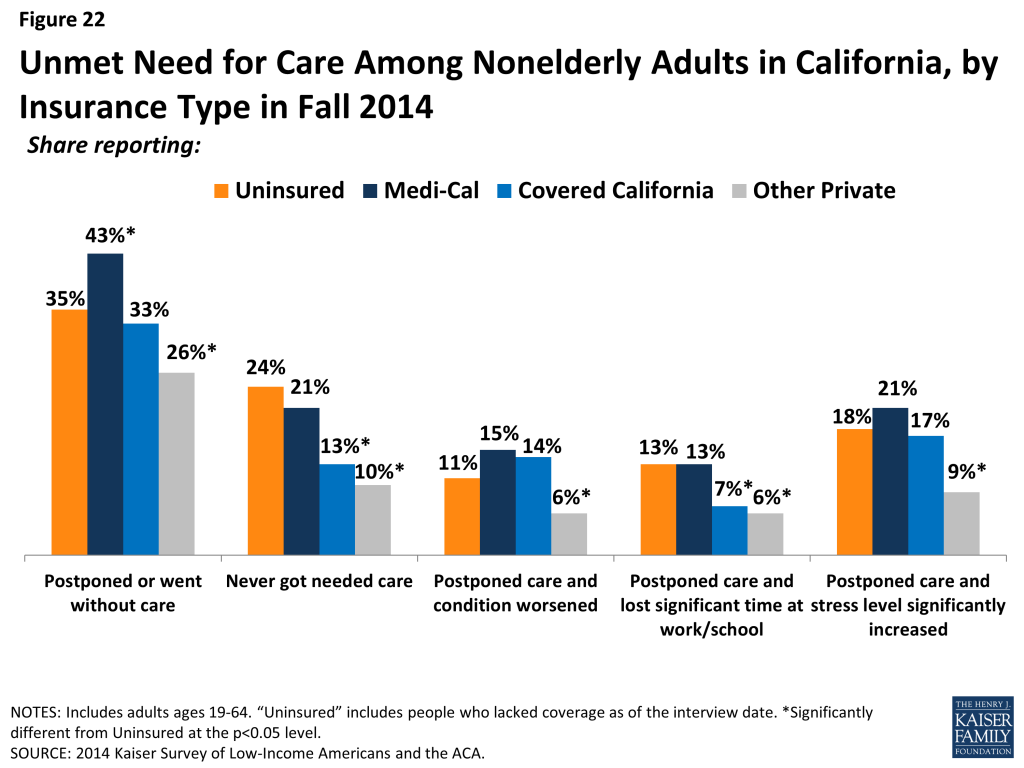

Still reflecting some unmet need, many newly insured adults reported postponing or delaying needed services. More than a third of newly insured adults (35%) reported that they postponed or went without needed care since gaining their coverage, the same share as the uninsured and a higher share than the previously insured. Similar patterns were seen for the shares reporting that they never received care or that postponing care had negative consequences such as a condition worsening, loss of time at work or school, or substantial stress. When comparing these outcomes by type of coverage, similar patterns persist, though Covered California enrollees were less likely than uninsured adults or adults in Medi-Cal to say that they never received the care they needed or that postponing care led them to miss work or school. Notably, Medi-Cal enrollees were more likely than uninsured adults to report postponing needed care; this outcome may be due to Medi-Cal enrollees’ poorer health status and the greater frequency with which they may need complex services. People with a large number of complex needs may be more likely to encounter access barriers for some services than those with more limited needs. Compared to 2013, Medi-Cal enrollees in 2014 were no more likely to say they postponed care and were less likely to say that their condition worsened or their stress increased as a result of postponing care. The high rates of unmet need among the uninsured corroborate existing evidence that this group goes without needed care due to cost, though the uninsured in 2014 were less likely to postpone care than the uninsured in 2013. Among those who do have coverage, postponing care could be related to several factors, including difficulty finding a provider, problems navigating the health system and health insurance networks, misunderstanding of how to use coverage and when to seek care, or concerns about out-of-pocket costs.

Though most adults did not report problems getting appointments, some insured adults say a provider would not take them as a patient due to coverage. Though a very small share (7%) of newly insured or previously insured (4%) adults reported this problem, both these groups were more likely than the uninsured to say a provider would not accept them as a patient due to coverage. The low rates of these problems among the uninsured (2%) likely reflect this group’s lower propensity to seek care, as detailed elsewhere, although uninsured adults in 2014 were more likely than those in 2013 to say they were told a provider would not take them as a patient. There were no significant differences in the share reporting not being taken as a new patient for any reason or reporting having to wait longer than they thought reasonable for an appointment. However, when examined by type of coverage, differences do emerge, with adults in Covered California or Medi-Cal being more likely to report being told that a provider would not take them as a patient than adults with other private coverage. Medi-Cal enrollees in 2014 were no more likely to say a provider would not take them as a patient than those in 2013. Like the forces underlying choice of usual source of care, these issues may reflect continuing problems with network adequacy, despite the existence of state standards for network adequacy and patient access.

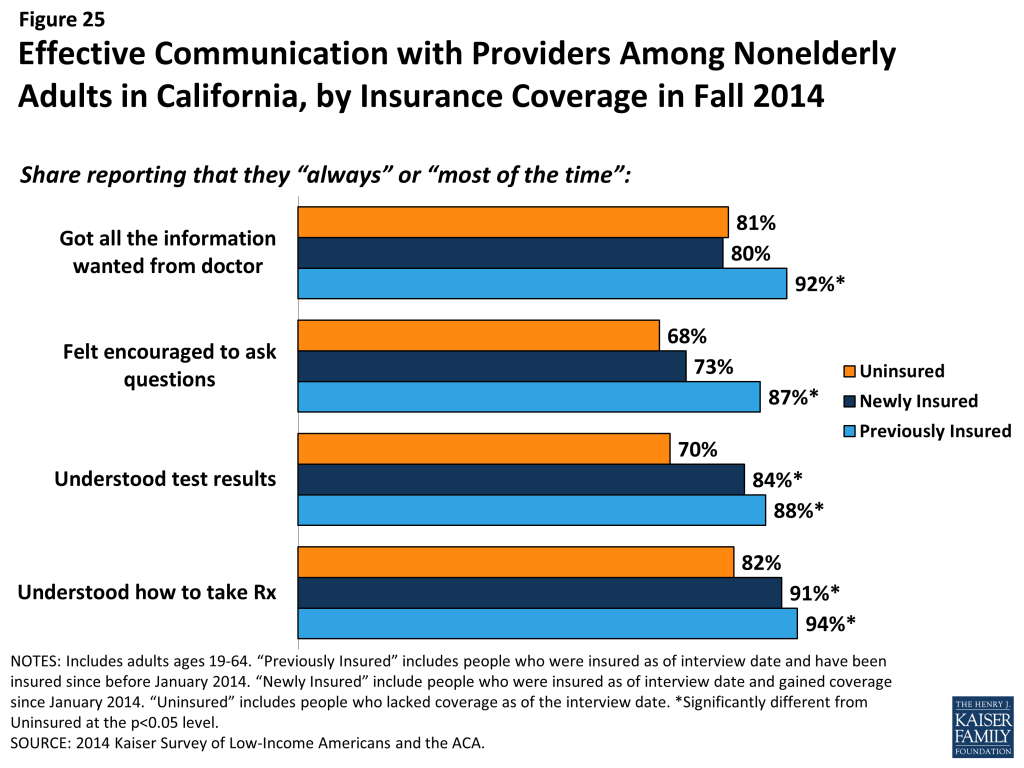

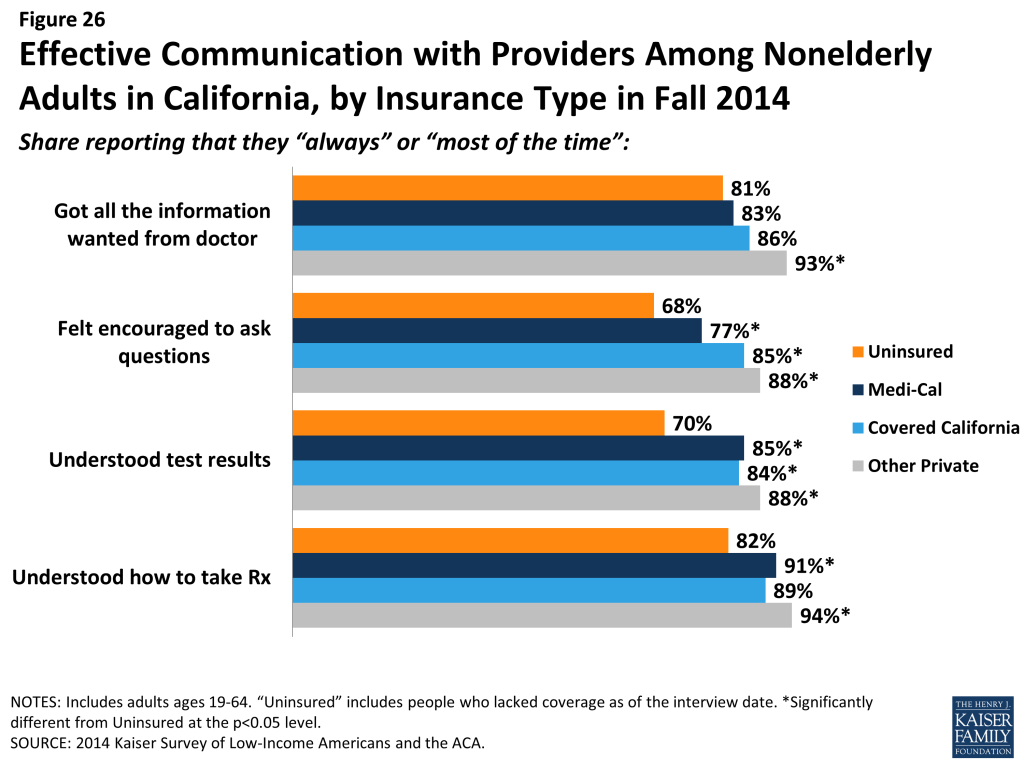

Among adults who received care, most adults across coverage types report effective communication with their providers about their care. Once people get into care, health literacy—or “patients’ ability to obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services they need to make appropriate health decisions”61 —plays an important role in how that care affects health outcomes. Health literacy depends on a range of factors related to patients (e.g., engagement in care), providers (e.g., how the information is communicated), service setting (e.g., the length of time of the interaction), and the nature of the visit (e.g., the complexity of health information). Survey results reveal that both previously insured and newly insured both reported understanding their test results or how to take their medication either “always” or “most of the time” that they saw a provider in higher proportions than the uninsured. However, on outcomes of getting all the information you wanted from the provider or feeling encouraged to ask questions, the newly insured were no more likely than the uninsured to report experiencing these always or most of the time.

Comparing results by coverage type reveals few differences, though Medi-Cal enrollees were less likely than adults with other private coverage to report getting all the information they wanted or feeling encouraged to ask questions. A statewide analysis of consumer ratings of doctor communication for all health plans found that Medi-Cal managed care plans received a “poor” rating relative to national benchmarks and thresholds, but ratings varied greatly across plans.62 This pattern may stem from income differences between the groups, since low-income Californians are less likely than higher-income Californians to give high ratings of communication with their provider, patient satisfaction, or patient engagement.63 Gaps in patient-satisfaction and engagement stem from low-income Californians reporting lower rates of feeling connected to the health care system or to seeing the same provider over time.64

Report: How Do People View Their Coverage?

People’s views of their plan may affect not only their use of their coverage but also the likelihood that they re-enroll in coverage or change plans. Survey results reveal that newly insured adults were very sensitive to cost in choosing their plan, placing a priority on cost over benefits and provider networks. A minority of all insured adults reported problems in selecting their plan or using their plan. However, newly insured adults were more likely than previously to say they do not understand the details of their plan and were more likely to give their plan a low rating. These findings indicate that additional education may be needed to help people understand their coverage.

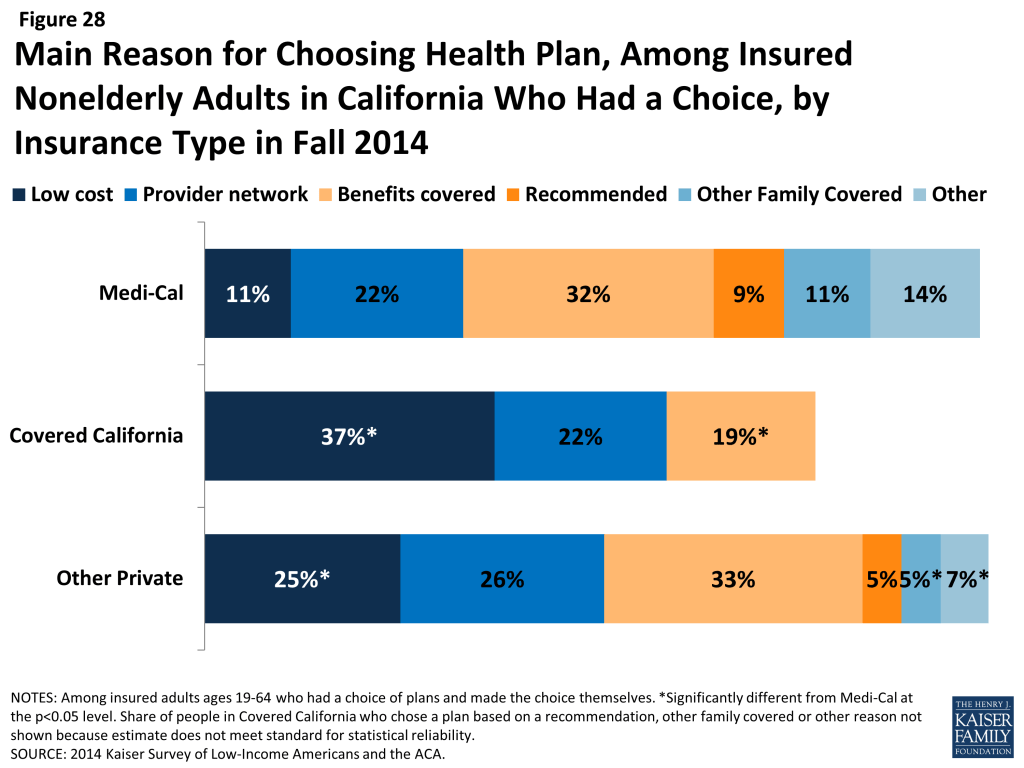

Newly insured adults were less likely to prioritize scope of coverage or provider networks in choosing their plan than previously insured adults. Among adults who say they had a choice of plans and made the choice themselves, less than a fifth (19%) of newly insured adults say they chose their plan because of the benefits covered, compared to 33% of previously insured adults, and only 14% say they chose their plan based on provider network (versus 26%) of previously insured. Newly insured adults were most likely to say they chose their plan because of low cost (29%); while this share was higher than the previously insured (23%), the difference was not statistically significant. Newly insured adults may have been less likely to choose based on benefits because new regulations set a minimum scope of coverage across new plans (so-called “essential health benefits”), but “grandfathered” pre-existing plans are not held to the same requirement. Alternatively, newly insured adults may be more sensitive to price than their previously insured counterparts, even with the availability of financial assistance for coverage.

Price was a particularly important factor in choice of plans among Covered California enrollees, 37% of whom said they chose their plan because of cost (versus 11% of Medi-Cal and 25% of adults with private coverage). In Covered California, premiums varied by region, ZIP code, metal level and age, but benefits were standardized across plans.65 Compared to other coverage groups, Medi-Cal enrollees were less likely to choose a plan based on price and more likely to choose a plan based on other factors such as other family members being enrolled in the plan. In Medi-Cal, plan benefits are largely standardized. Further, enrollees face limited or no out-of-pocket costs for services, so the small share indicating that they chose based on price may indicate confusion about their plan.

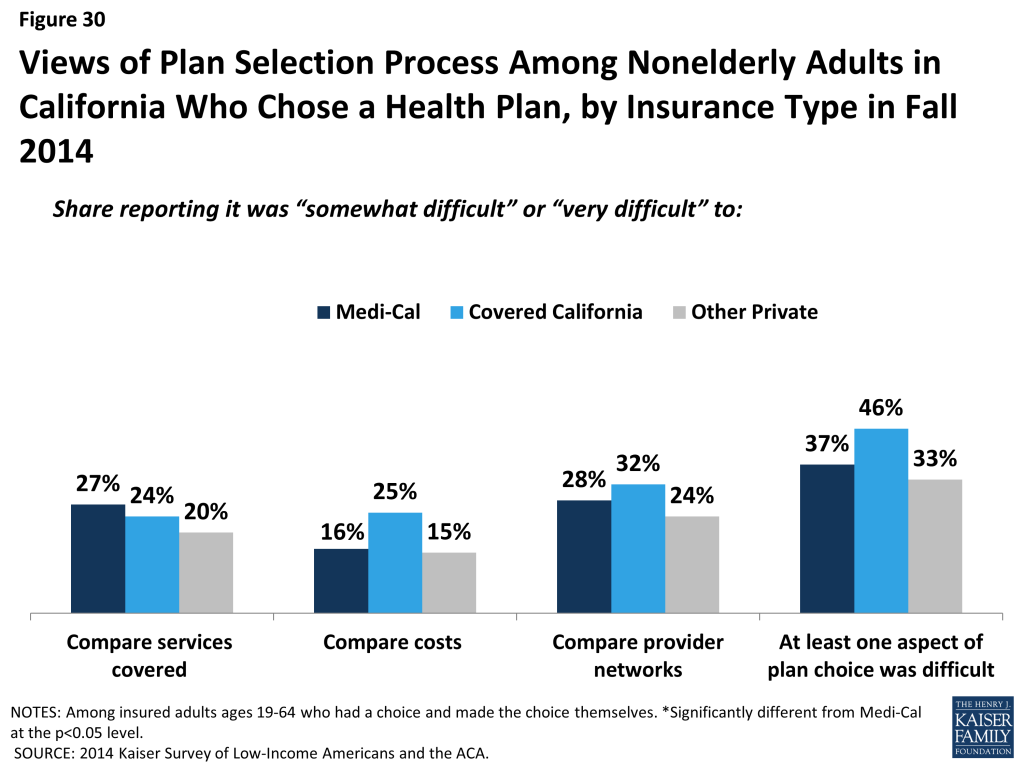

Across coverage groups, most insured adults did not report difficulty with the plan selection process. While rates of difficulty comparing services, costs, or provider networks across plans varied slightly by timing of coverage and coverage type, there were no significant differences across groups. Still, notable shares reported having difficulty with at least one aspect of plan choice, and the newly insured were more likely than the previously insured to report at least one difficulty (48% versus 34%). The most common difficulty across all coverage groups was comparing provider networks, a finding that echoes patterns nationwide. California, along with several other states, requires all participating Marketplace plans to offer standardized benefit designs, allowing consumers to accurately compare plans based on cost and network alone, since benefits are identical for all plans.66 In Medi-Cal, benefits and cost sharing are standardized across plans.

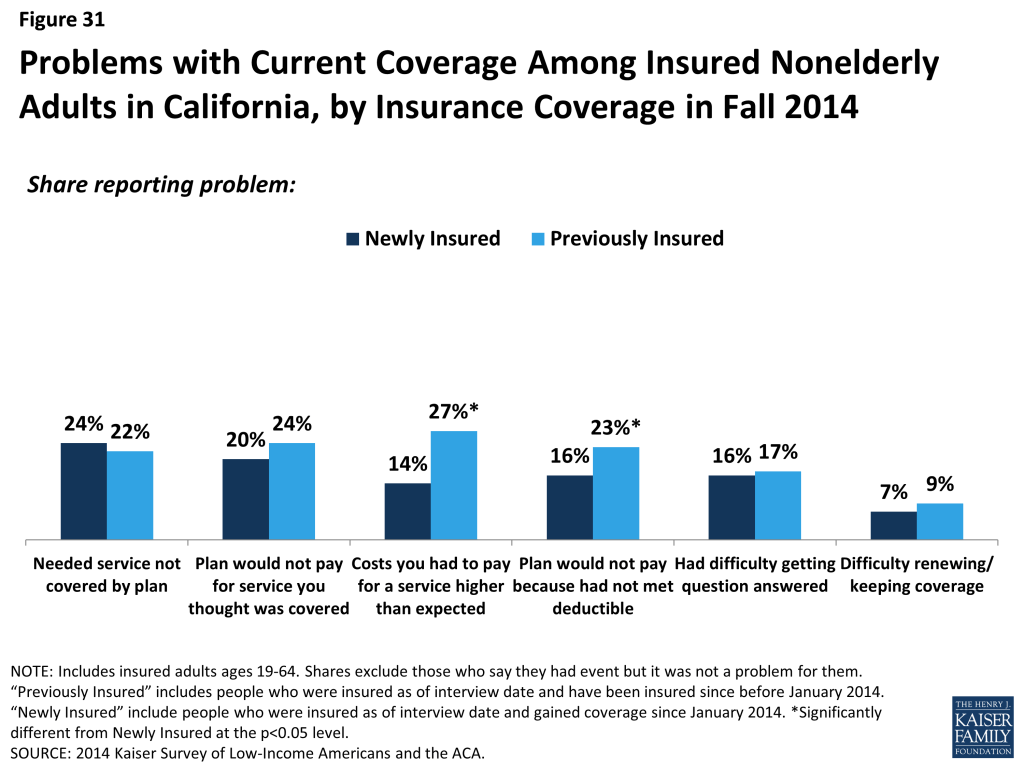

Newly insured adults were no more likely than previously insured to report a specific problem with their health plan. When asked specifically if they encountered various problems with their coverage, such as benefits, costs, or customer service, newly insured adults reported similar or lower rates than previously insured. Specifically, there were no significant differences in shares reporting needing a service that was not covered, being denied coverage for a service they thought was covered, having difficulty getting a question answered, or renewing coverage. Newly insured adults were less likely than previously insured to say they faced higher than expected out-of-pocket costs or that they had not yet met their deductible.

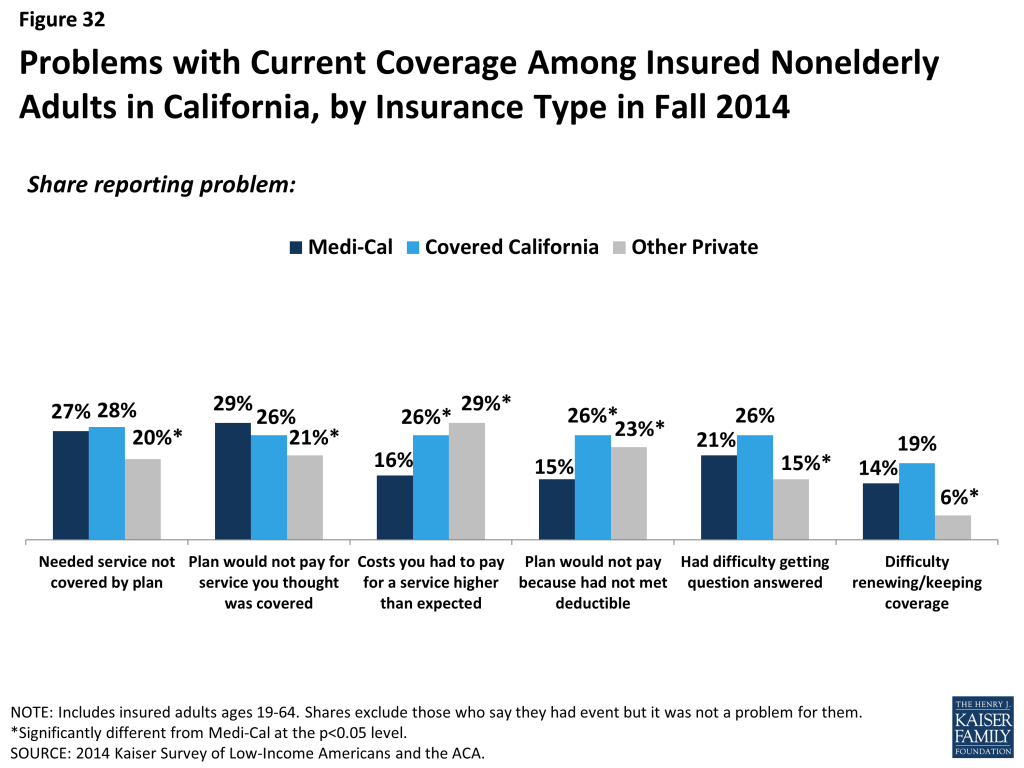

Comparing problems with plan by type of coverage reveals mixed results for different types of problems. Medi-Cal enrollees were less likely than those with Covered California or other private coverage to report cost-related problems, such as facing higher than expected costs or not meeting a deductible. In Medi-Cal, enrollees do not have deductibles and face very limited or no out-of-pocket costs; the fact that any Medi-Cal enrollees reported these problems may reflect service use outside their Medi-Cal plan or may reflect misunderstanding of their plan. On problems related to scope of coverage (e.g., needing a service not covered or being denied coverage for a service) or administrative issues (e.g., getting a question answered or renewing coverage), there were no significant differences between Medi-Cal and Covered California, but adults with other private coverage were less likely to report such problems.

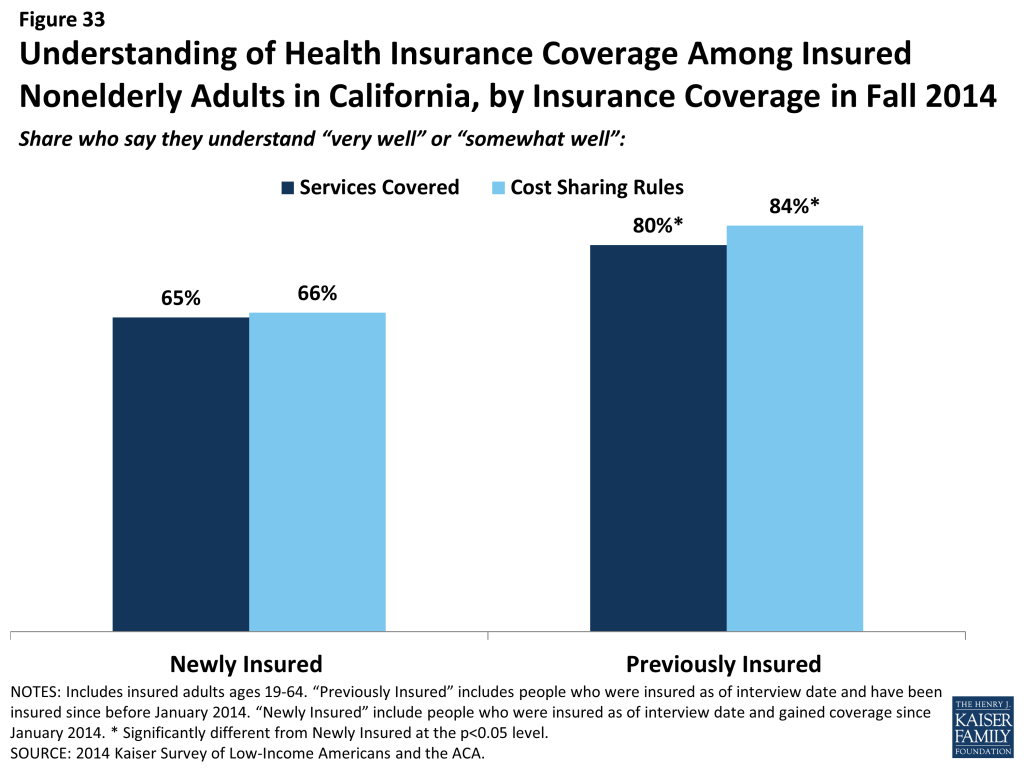

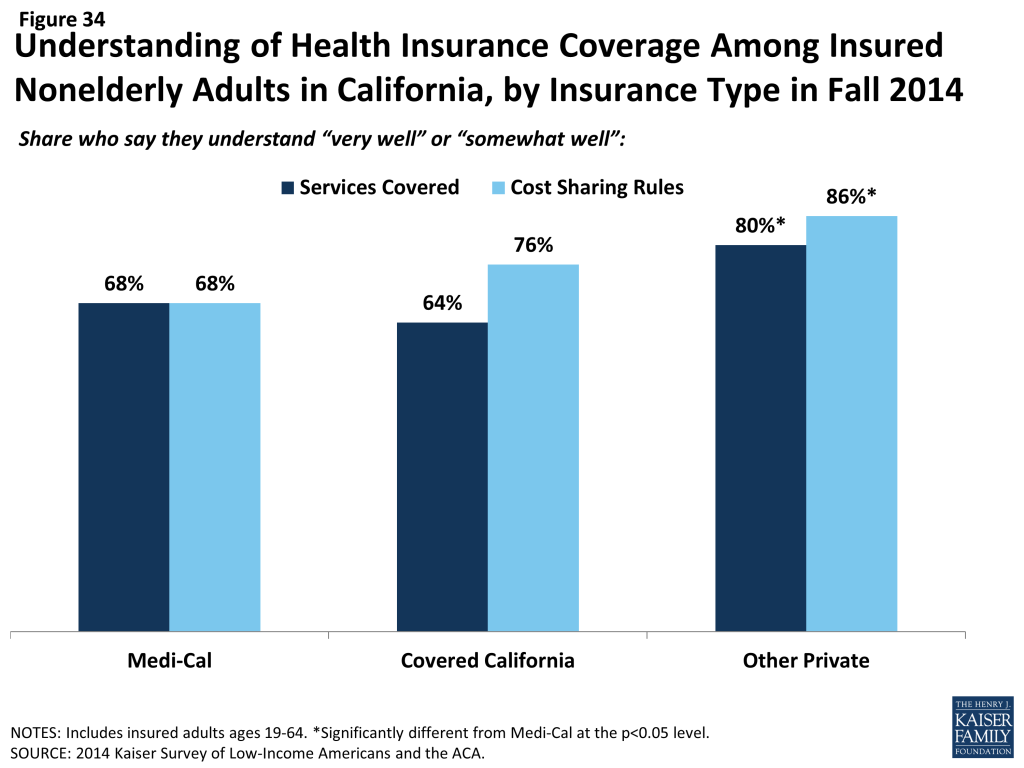

Newly insured adults were also more likely than previously insured to not understand the details of their plan. About two thirds of newly insured adults said they understand the services their plan covers (65%) or how much they would have to pay when they visit a health care provider (66%) “very well” or “somewhat well.” In contrast, previously insured adults were more likely to say they understood the scope of benefits (80%) or cost sharing rules (84%) of their plans. It is possible that newly insured adults face challenges in understanding the complexity of insurance coverage, especially since many adults who were uninsured before the ACA reported that they had never had health insurance.67 When looking by coverage type, there are no significant differences in the share of Medi-Cal or Covered California enrollees reporting understanding these features of their plans. However, adults with other private coverage (most of whom are previously insured) were more likely to understand their plan.

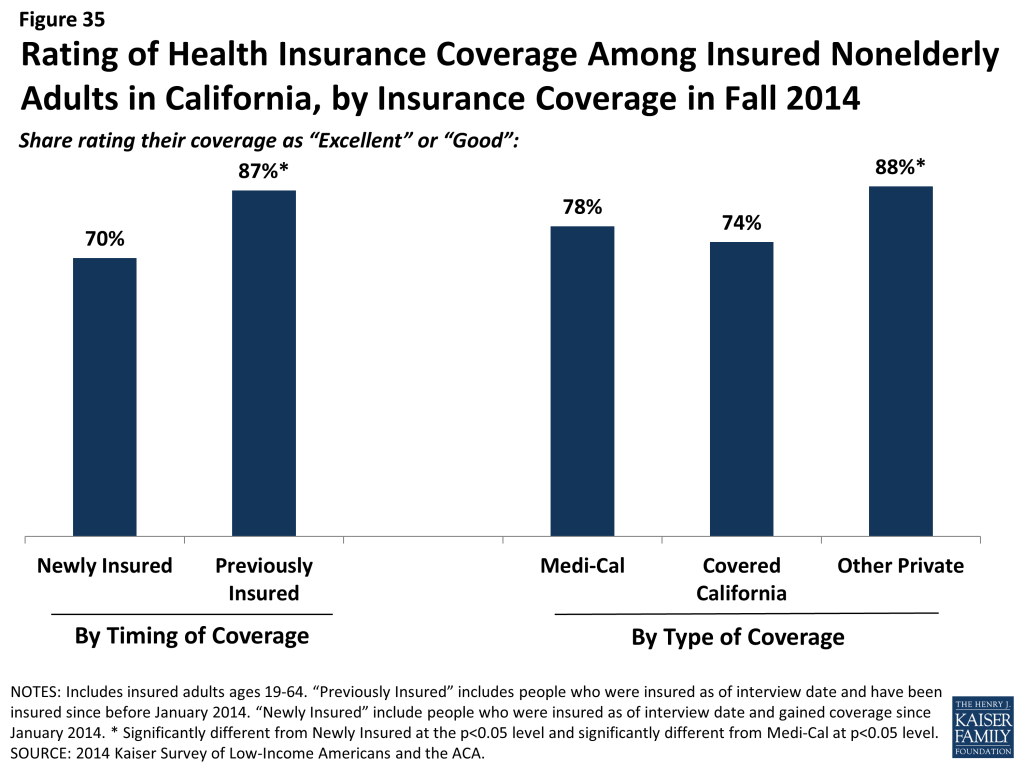

Though most newly insured adults give their health plan high ratings, they were less likely than the previously insured to do so. Seven in ten newly insured adults rate their coverage as “excellent” or “good” (versus “not so good” or “poor”). While these findings show high rates of satisfaction, adults who had coverage before 2014 were more likely to give their plan a high rating, with 87% saying their coverage was excellent or good. There were no significant differences between Medi-Cal and Covered California) in the share of people giving their plan a high rating; those with private coverage, on the other hand, were more likely to give their plan a high rating. Findings that newly insured adults were less likely to understand their plan but no more likely to have experienced difficulty with their plan indicate that health insurance literacy may be affecting plan ratings.

Report: How Does Coverage Affect Financial Security?

Health care costs can be a major burden for low-income families. While many newly insured adults report difficulty affording their monthly premium, they also report lower rates of problems with medical bills and lower rates of worry about future medical bill than their uninsured counterparts. However, newly insured adults still face financial insecurity: they are more likely than those who had coverage before 2014 to worry about future medical bills, and they face general financial insecurity at rates similar to the uninsured. These patterns may indicate that while coverage can ameliorate some of the financial challenges that low and moderate-income adults face, many will continue to face financial challenges in other areas of their lives.

Many Covered California enrollees report difficulty paying their monthly premium. Among adults who say that they pay a monthly premium for their health coverage, nearly half of newly insured adults (47%) say it is somewhat or very difficult to afford this cost, compared to just 27% of adults who were insured before 2014. When looking specifically by type of coverage, 44% of Covered California enrollees (not all of whom are newly insured) report difficulty paying their monthly premium, versus a quarter of adults with other types of private coverage. Medi-Cal enrollees do not pay monthly premiums for their coverage. Statewide, the average premium rate for the second-lowest cost silver plan in Covered California was $325 per month,68 compared to $226 nationally.69 While most people in Covered California received premium subsidies to offset some or most of this cost,70 subsidy levels are set at the federal level and do not account for the relatively high cost of living in the state that requires a greater share of family finances to go to other areas such as housing, food, or transportation.71

However, coverage does provide financial protection from medical bills and eases concern over affording medical care. Compared to the uninsured, both newly insured and previously insured adults report lower rates of difficulty paying medical bills. Despite being less likely to use services, over a quarter (26%) of uninsured adults report a problem paying medical bills, a rate higher than both the newly insured and previously insured. Uninsured adults were also more likely to report serious consequences from medical bills, such as using up their savings, having difficulty paying for necessities, borrowing money, or being sent to collection. The uninsured were significantly more likely than the previously insured to report that medical bills led to difficulty paying for basic necessities; however, compared to the newly insured, there was no significant difference in medical bills leading to problems paying for necessities.

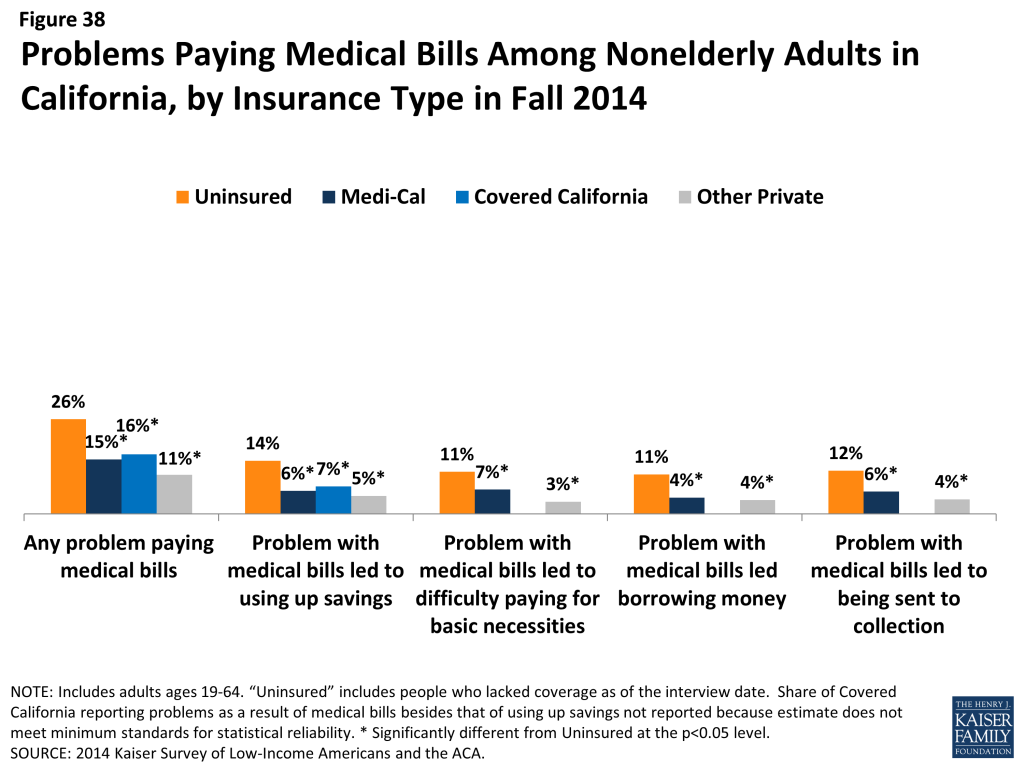

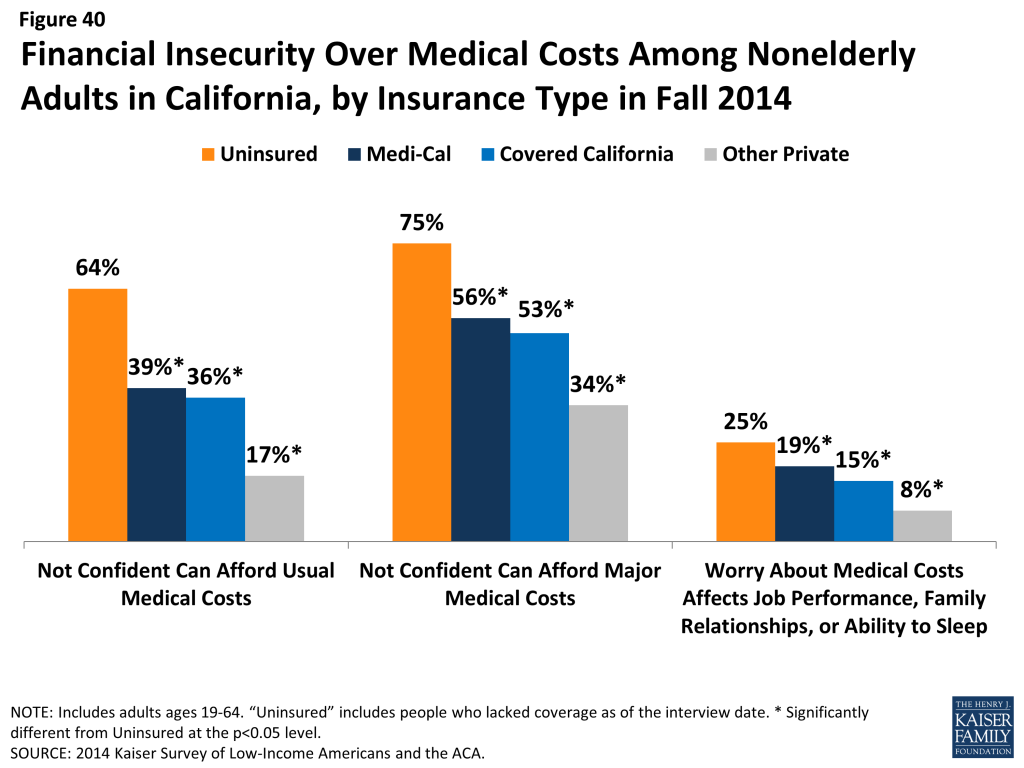

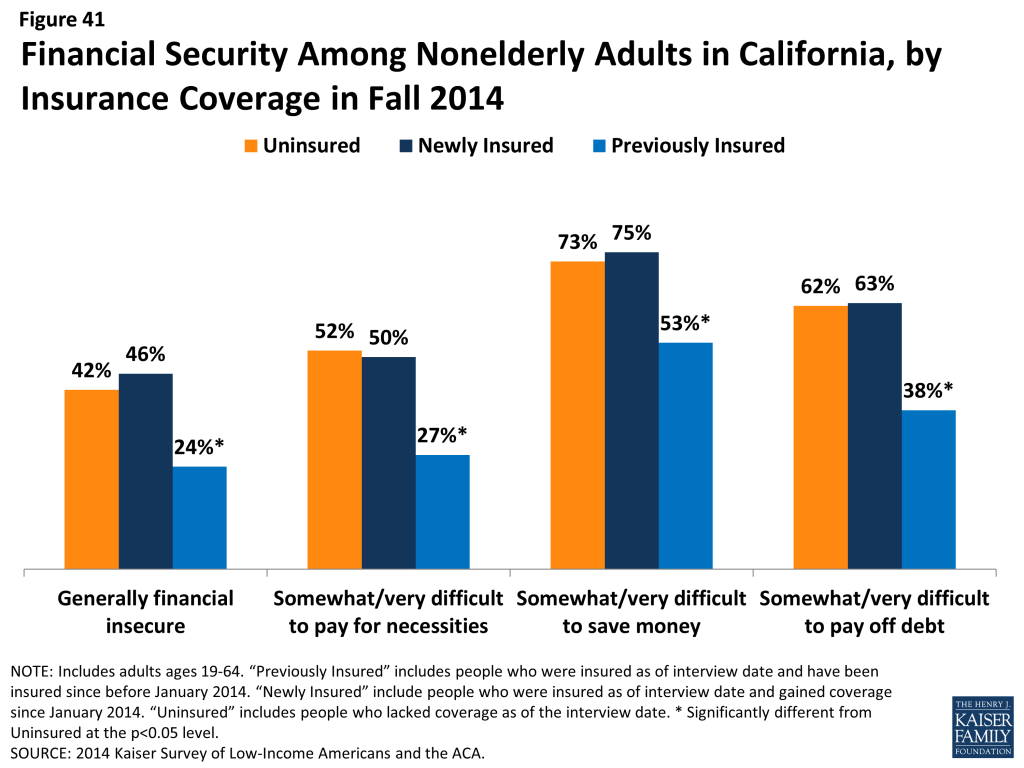

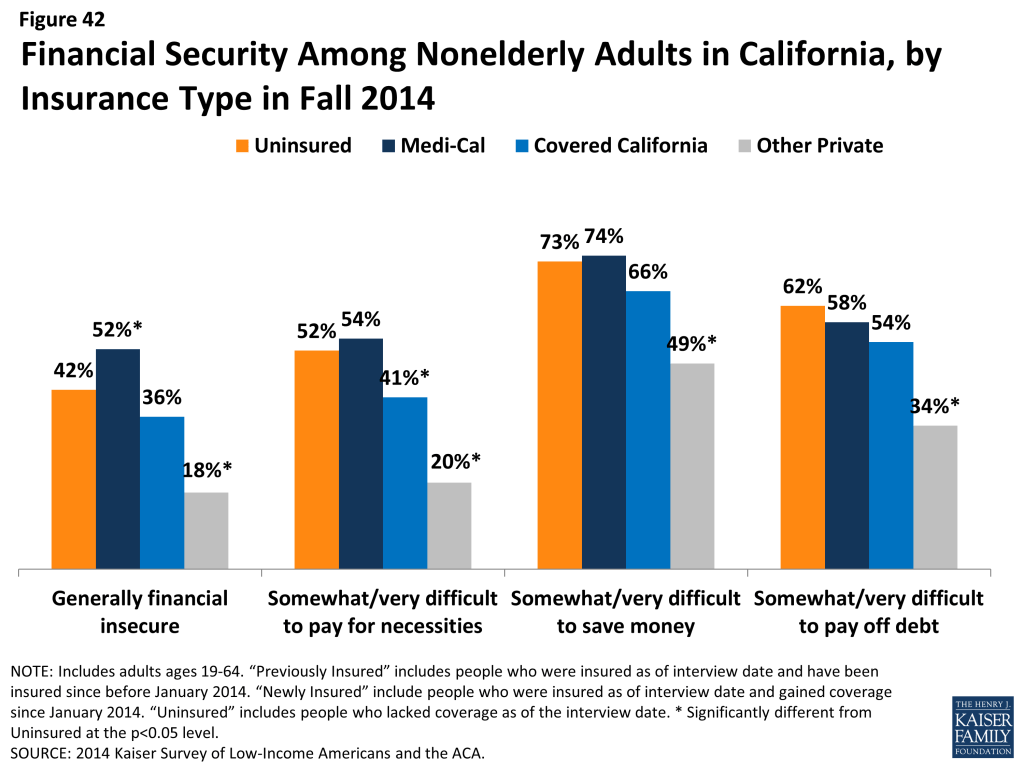

When comparing the uninsured to adults with different types of coverage, including Medi-Cal, Covered California, or other private coverage, adults with each type of coverage were less likely than the uninsured to report problems paying medical bills. However, likely reflecting differences in income between these groups, adults with Medi-Cal coverage were significantly more likely than those with other private coverage to report difficulty paying for basic necessities as a result of medical bills (7% versus 3%) and problems paying medical bills (15% versus 11%). As mentioned earlier, Medi-Cal enrollees pay nothing or very little for their medical care, so the share reporting problems related to medical bills may indicate confusion about their plan or services they received that are not covered by their plan. Compared to 2013, there was no significant change in the share of uninsured or Medi-Cal respondents reporting problems with medical bills.72