Medicaid Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Overview and Key Issues in Medicaid Expansion Waivers

Issue Brief

Medicaid’s non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit facilitates access to care for low income beneficiaries who otherwise may not have a reliable affordable means of getting to health care appointments. NEMT also assists people with disabilities who have frequent appointments and people who have limited public transit options and long travel times to health care providers, such as those in rural areas. NEMT expenses eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds include a broad range of services, such as taxicabs, public transit buses and subways, and van programs. Although comprehensive data about Medicaid NEMT expenditures do not exist because states are not required to separately report on this item, the Transit Cooperative Research Program, a federally funded independent research entity, estimates NEMT spending at $3 billion annually, less than one percent of total Medicaid expenditures.1 This issue brief describes the NEMT benefit, how states administer it, and the reasons that beneficiaries frequently use NEMT. It also explores current policy issues related to NEMT in the context of alternative Medicaid expansion waivers.

What is Medicaid’s Non-Emergency Medical Transportation Benefit?

State Medicaid programs are required to provide necessary transportation for beneficiaries to and from providers. NEMT services are not included in the statutory list of mandatory Medicaid benefits but are required by a long-standing federal regulation,2 based on the Department of Health and Human Services’ statutory authority to require state Medicaid plans to provide for methods of administration necessary for their proper and efficient operation.3 Additionally, as part of the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, states are required to offer children from birth to age 21 and their families “necessary assistance with transportation” to and from providers.4

How is the Medicaid NEMT Benefit Administered?

State Medicaid agencies have considerable latitude in how they administer NEMT benefits. Federal law contains a broad guideline that state Medicaid plans must specify the methods used to provide NEMT.5 Most states utilize third-party brokerage firms to coordinate transportation for beneficiaries in return for a capitated payment, while some states deliver NEMT directly via fee-for-service reimbursements, and still others rely on a mix of capitated brokerage, direct delivery, and public transit voucher programs as appropriate based on geographic and beneficiary needs.6

State spending for Medicaid NEMT services can be reimbursed as an administrative expense or as a medical service expense. Reimbursement as an administrative expense caps the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), or the amount of federal matching funds available, at 50% like other administrative expenses. Claiming as an administrative expense affords states greater flexibility in delivery system design and eliminates the free choice of provider requirement, allowing for contracts with a single provider and alternative payment models, like vouchers. Claiming NEMT as a medical service expense allows for reimbursement at the state’s regular FMAP, which ranges from 50 to 74.63% in FY 2017, depending on state per capita income, for most populations.7 Claiming as a medical service expense generally makes NEMT subject to additional guidelines, including offering beneficiaries free choice of providers and covering travel for attendant care providers. However, the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005 added an option for states to include NEMT brokerage programs in their Medicaid state plans where cost-effective.8 States using the DRA option can claim NEMT as a medical expense, accessing their regular FMAP, while also limiting beneficiaries’ free choice of provider and varying NEMT programs by geographic region and in amount, duration, and scope.9

Why Do Medicaid Beneficiaries Use NEMT?

NEMT can be a cost-effective means of facilitating access to care for Medicaid beneficiaries. One study estimated that at least 3.6 million people miss or delay medical care each year because they lack available or affordable transportation.10 This study found that improved access to NEMT for this population is cost-effective or cost-saving for all 12 medical conditions analyzed, including preventive services such as prenatal care, and chronic conditions such as asthma, heart disease, and diabetes.11 Another study found that adults who lack transportation to medical care are more likely to have chronic health conditions that can escalate to a need for emergency care if not properly managed.12 This study also noted that adults who lack transportation to medical care are disproportionately poor, elderly, and disabled and more likely to have multiple health conditions.13 Most recently, a report for the Arkansas Health Reform Task Force cited national studies showing a positive return on investment for NEMT and recommended that the state retain its current Medicaid NEMT benefit structure as it has proven cost effective.14

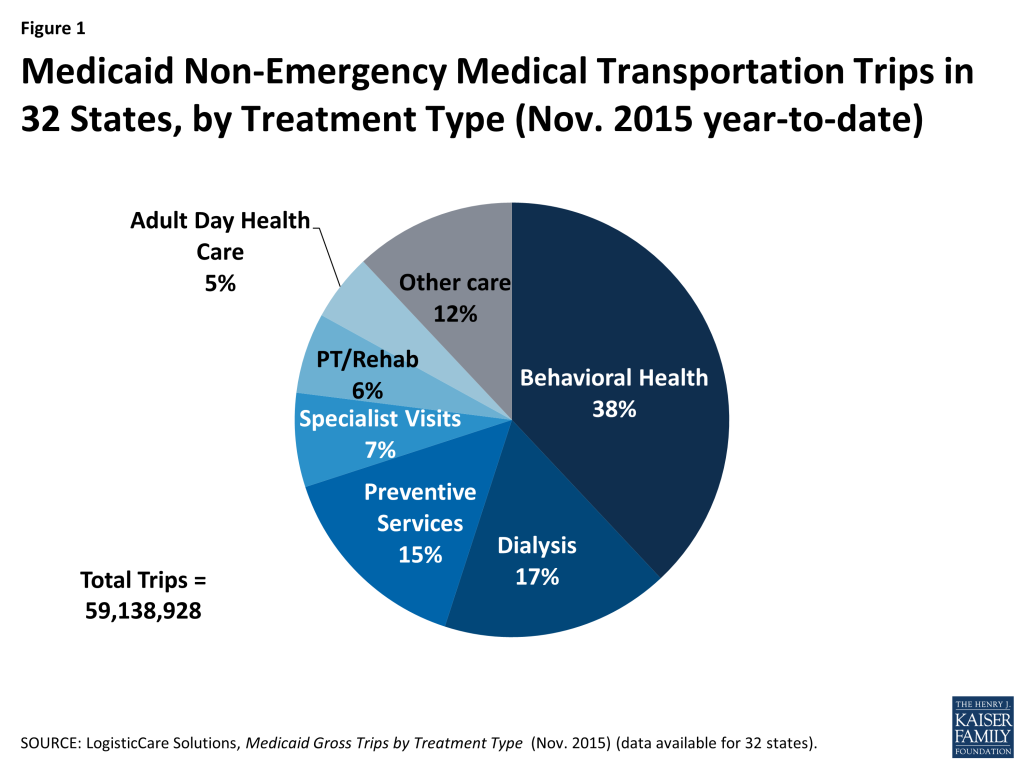

Beneficiaries frequently use NEMT to access behavioral health services, preventive health services, and care for chronic conditions. While there are no comprehensive national data about beneficiary use of NEMT (because states are not required to separately report this data), information from one company that provides Medicaid NEMT services in 32 states indicates that the most frequently cited reasons for using NEMT are accessing behavioral health services (including mental health and substance abuse treatment), dialysis, preventive services (including doctor visits), specialist visits, physical therapy/rehabilitation, and adult day health care services.15 (Figure 1)

Adult Medicaid beneficiaries frequently use NEMT to access behavioral health services. For example, data about NEMT use in 2 states (Nevada and New Jersey) that adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion show that both expansion adults and those who were eligible for Medicaid prior to the ACA most frequently use NEMT to access mental health and substance abuse treatment services (over 40% of total trips for both groups in NJ, and over 30% of total trips for both groups in NV, from Feb. to April 2014).16 These data also indicate that expansion adults’ use of NEMT has grown over time (from 1.9% to 5.1% from Feb. 2014 through April 2015 in NJ, and from 1.5% to 5.2% from March 2014 through April 2015 in NV).17 This could be due to beneficiaries learning about the availability of these services as they are enrolled longer and have more experience with using and understanding the Medicaid program.

Expansion adults and children in particular frequently use NEMT to access preventive care. When considering the top ten reasons for NEMT use, expansion adults in Nevada and New Jersey were more likely than traditional Medicaid beneficiaries to use NEMT to access preventive services (54% greater utilization for preventive services in NJ from Feb. 2014 to April 2015, and 53% greater utilization for preventive services in NV from March 2014 to April 2015).18 Another study found that children who used Texas’s Medicaid NEMT program were significantly more likely to access EPSDT’s preventive services, at a rate of almost one more visit per year.19 These services can help to address health disparities in early childhood, such as those resulting from socioeconomic factors. NEMT services also facilitated Texas children’s access to periodic appointments, such as routine immunizations, vision screenings, and neonatal visits.

What is NEMT’s Role in Medicaid Expansion Waivers?

Adults who are eligible for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act’s expansion up to 138% FPL must receive a benefit package that includes NEMT.20 As with other beneficiaries, NEMT for expansion adults can be considered an administrative expense or a medical service expense for purposes of claiming federal matching funds. NEMT claimed as a medical service expense for expansion adults is subject to the ACA’s enhanced FMAP, which is substantially higher than states’ regular FMAPs, 100% until 2016, and gradually decreasing to 90% by 2020, where it remains indefinitely.21

Two states (Iowa and Indiana) with approved Section 1115 demonstrations to expand Medicaid in ways that differ from existing federal law are implementing time-limited waivers of NEMT.22 (Pennsylvania’s demonstration also included a limited NEMT waiver, although Pennsylvania subsequently transitioned to a traditional Medicaid expansion, and its demonstration is no longer being implemented.23 ) Iowa and Indiana’s NEMT waivers exclude medically frail individuals. These states sought waivers because they are seeking to offer a benefit package to expansion adults similar to private insurance coverage, which does not include NEMT.

Some other states are interested in waiving NEMT as part of Medicaid expansion demonstrations. Arizona has an application pending with CMS that seeks a one year waiver of NEMT for expansion adults from 101-138% FPL.24 NEMT waivers also were part of the Medicaid expansion proposals debated in Utah and Tennessee, although no waiver applications from those states have been submitted to CMS to date.25

Another Medicaid expansion waiver state, Arkansas, decided to keep its NEMT benefit as the state believes its brokerage model has proven cost-effective. When amending its Medicaid expansion waiver, Arkansas sought authority to limit NEMT for expansion adults but subsequently established a prior authorization process for NEMT that did not require waiver authority.26 Arkansas provides NEMT to expansion adults as a wrap-around benefit on a fee-for-service basis because its entire Medicaid expansion population is required to enroll in Marketplace premium assistance, and NEMT is not offered in Marketplace plans.27 A recent report for the Arkansas Health Reform Task Force (described above) recommended that the state keep NEMT in place because there is a “very effective brokerage model for non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) with a capitated benefit structure that manages the program in a cost effective manner.”28

In response to a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) study, states cited “consider[ing] the NEMT benefit crucial to ensuring enrollees’ access to care” and “want[ing] to align benefits for the newly eligible enrollees with those offered to enrollees covered under the traditional Medicaid state plan” as among the reasons offered for maintaining the NEMT benefit for expansion adults.29 Of the 30 Medicaid expansion states studied by the GAO in September, 2015, 25 reported that they did not seek to exclude NEMT when they implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and were not considering doing so.30 The GAO found that state efforts to exclude NEMT from Medicaid expansion adults are “not widespread.”31

What is the Impact of Waiving NEMT for Expansion Adults?

CMS conditioned extension of Iowa and Indiana’s NEMT waivers on an evaluation of the waiver’s impact on beneficiary access to care.32 Iowa’s initial NEMT waiver was approved from January through December 2014, and its Medicaid expansion demonstration expires on December 31, 2016. Indiana’s initial NEMT waiver was approved from January, 2015 through January, 2016, and its Medicaid expansion demonstration expires in January, 2018.

Preliminary state data evaluating the impact of Iowa’s NEMT waiver indicate that the waiver may have adverse implications for beneficiary access to care. A fall 2014 beneficiary survey found that Iowa Medicaid beneficiaries whose benefit package does not include NEMT are more likely than those with access to NEMT to need assistance with travel to a health care visit.33 CMS noted that these data “raised concerns about beneficiary access [to care,] particularly for those with incomes below 100 percent of the [federal poverty level,] FPL.”34

CMS has extended Iowa’s and Indiana’s NEMT waivers, pending additional evaluation results. Iowa’s waiver was extended through July 31, 2015, and again through March 31, 2016. Indiana’s waiver has been temporarily extended through November 30, 2016.

Additional data from the NEMT waiver evaluations are expected but not yet publicly available. After reviewing the preliminary evaluation results, CMS instructed Iowa to conduct another survey to compare with the fall 2014 data.35 By December 31, 2015, Iowa was to provide CMS with the results of this survey and its draft interim demonstration evaluation comparing utilization outcomes for beneficiaries who have an unmet transportation need and who do not have access to NEMT with other beneficiaries. Iowa also was to submit a readiness plan for beginning NEMT services in the event that CMS does not extend the NEMT waiver beyond March, 2016.36 Indiana is due to submit state survey data and analyses evaluating its NEMT waiver to CMS by February 29, 2016. In addition to the state evaluation findings, CMS noted that it will consider beneficiary survey data from the federal demonstration evaluation in Indiana, when determining whether to extend Indiana’s waiver, due to CMS’s concerns about sample sizes and limited use of control groups in the state evaluation.37

The recent GAO report identifies decreased access to care and increased costs of care as potential implications of waiving NEMT for expansion adults.38 The research and advocacy groups interviewed by the GAO as part of its study cited access to care issues particularly for those living in rural or underserved areas and for those with chronic health conditions.39 While expansion adults who qualify as medically frail in Iowa and Indiana must receive NEMT, some interviewees noted that medical frailty determinations may be too limited in terms of which people with chronic health conditions can qualify and may involve long waits.40 GAO’s interviewees also noted that those “without access to transportation may forgo preventive care or health services and end up needing more expensive care, such as ambulance services or emergency room visits.”41

Looking Ahead

Medicaid beneficiaries rely on NEMT in the absence of other affordable available transportation to necessary medical care. Evidence supports this service as a cost-effective or cost-saving measure for facilitating access to care for beneficiaries with low incomes, including people seeking preventive services as well as those with disabilities and chronic conditions that require more frequent regular care. States have flexibility in how they administer NEMT under existing law, and recent demonstrations have allowed Iowa and Indiana to test whether waiving this benefit for expansion adults adversely affects access to care. CMS has extended these waivers pending the availability of additional data, while noting that early data from Iowa raises concerns about an adverse impact on beneficiary access to care. Other states, such as Arkansas, have determined that providing NEMT to expansion adults is cost-effective, and data from Nevada and New Jersey indicate that expansion adults are using NEMT to access behavioral health services at a similar rate and preventive care at a greater rate compared to the traditional Medicaid population. Given the interest in NEMT waivers for expansion adults in other states, following developments in this area will be important in evaluating NEMT’s role in facilitating Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to care and its impact on health outcomes.

Endnotes

- Transit Cooperative Research Program, Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Assessment for Transit Agencies at 2 (Oct. 2014), http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rrd_109.pdf. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 431.53. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(4)(A). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 441.62; see also 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(43) (requiring state to arrange for screening services and corrective treatment for EPSDT beneficiaries). ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 431.53. ↩︎

- See, e.g., J. Kim et al., “Transportation Brokerage Services and Medicaid Beneficiaries’ Access to Care,” 44 Health Serv. Res. 145-161 (2009), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2669622/; see also Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services., EPSDT-A Guide for States: Coverage in the Medicaid Benefit for Children and Adolescents (2014), http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Downloads/EPSDT_Coverage_Guide.pdf. ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and Multiplier Data Source: FY 2017: 80 Fed. Reg. 73779 (Nov. 25, 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/federal-matching-rate-and-multiplier/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(70); 42 C.F.R. § 440.170(a)(4). ↩︎

- S. Rosenbaum, et al., Medicaid’s Medical Transportation Assurance: Origins, Evolution, Current Trends, and Implications for Health Reform (July 2009), http://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1035&context=sphhs_policy_briefs. ↩︎

- P. Hughes-Cromwick and R. Wallace, et al., Cost-Benefit Analysis of Providing Non-Emergency Medical Transportation, Transit Cooperative Research Program (Oct. 2005), http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_webdoc_29.pdf. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Richard Wallace, et al, “Access to Health Care and Nonemergency Medical Transportation: Two Missing Links,” 1924 Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 76-84 (2005), http://www.researchgate.net/publication/39967547_ Access_to_Health_Care_and_Nonemergency_Medical_Transportation_Two_Missing_Links. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- The Stephen Group, Volume II: Recommendations to the Arkansas Health Reform Task Force (Oct. 2015), http://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/assembly/2015/Meeting%20Attachments/836/ I14099/TSG%20Volume%20II%20Recommendations.pdf. ↩︎

- LogistiCare Solutions, Medicaid Gross Trips by Treatment Type (Nov. 2015) (on file with authors). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- LogistiCare Solutions, NJ Expansion Analysis (on file with authors); LogistiCare Solutions, NV Expansion Analysis (on file with authors). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- S. Borders, Transportation Barriers to Health Care: Assessing the Texas Medicaid Program, Dissertation submitted to Texas A&M University Office of Graduate Studies (May 2006), http://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/bitstream/handle/1969.1/6016/etd-tamu-2006A-URSC-Borders.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. ↩︎

- 42 C.F.R. § 440.390. The Affordable Care Act requires states to expand Medicaid to adults with income up to 138% FPL as of 2014. However, the Supreme Court’s decision on the constitutionality of this provision effectively made expansion a state option. See Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, A Guide to the Supreme Court’s Decision on the Medicaid Expansion (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Aug. 2012), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/a-guide-to-the-supreme-courts-decision/. Expansion adults receive an alternative benefit plan. 42 U.S.C. § 1396(k)(1). ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Financing Medicaid Coverage Under Health Reform: What is in the Law and the New FMAP Rules (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, May 2013), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/financing-medicaid-coverage-under-health-reform-the-role-of-the-federal-government-and-states/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Nov. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-medicaid-expansion-waivers/ . To date, 32 states (including DC) have implemented the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, most of which have done so through a traditional state plan amendment instead of a waiver. Kaiser Family Foundation State Health Facts, Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision Data Source: Based on KCMU tracking and analysis of state executive activity (Jan. 12, 2016), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion in Pennsylvania: Transition from Waiver to Traditional Coverage (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Aug. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-pennsylvania/. ↩︎

- Arizona expanded Medicaid in 2014 as envisioned in the ACA but is now seeking changes through waiver authority as required by state law. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Proposed Changes to Medicaid Expansion in Arizona (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Nov. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/proposed-changes-to-medicaid-expansion-in-arizona/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Proposed Medicaid Expansion in Tennessee (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Jan. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/proposed-medicaid-expansion-in-tennessee/; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Proposed Medicaid Expansion in Utah (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Jan. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/proposed-medicaid-expansion-in-utah/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Nov. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-medicaid-expansion-waivers/. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, A Look at the Private Option in Arkansas, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Aug. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/a-look-at-the-private-option-in-arkansas/; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion in Arkansas (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Feb. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-arkansas/. ↩︎

- The Stephen Group, Volume II: Recommendations to the Arkansas Health Reform Task Force (Oct. 2015), http://www.arkleg.state.ar.us/assembly/ 2015/Meeting%20Attachments/836/I14099/TSG%20Volume%20II%20Recommendations.pdf. ↩︎

- GAO did not ask states to provide their reasons for not seeking to exclude NEMT from expansion adults, but 14 states offered reasons. Eight reported considering NEMT critical to ensuring access to care, four reported wanting to align new adult and traditional Medicaid benefit packages, and two reported seeing no need to alter the benefit as expansion did not significantly increase program enrollment. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Requesters, Medicaid, Efforts to Exclude Nonemergency Transportation Not Widespread, but Raise Issues for Expanded Coverage,GAO-16-221 at 10 (Jan. 2016), http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-221. ↩︎

- Three states (AZ, IA, and IN) indicated that they were pursuing efforts to exclude NEMT for expansion adults. Two states (NJ and OH) did not respond to GAO, but CMS confirmed that neither had sought to exclude NEMT as part of their Medicaid expansions. Id. at 6. ↩︎

- Id.at GAO Highlights page. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, The ACA and Medicaid Expansion Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Nov. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-medicaid-expansion-waivers/ ; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion in Iowa (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Nov. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-iowa/; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion in Indiana (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Feb. 2015), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-indiana/. ↩︎

- Letter from Cindy Mann, Director, CMCS, CMS to Julie Lovelady, Interim Medicaid Director, State of Iowa (Dec. 30, 2014), http://medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ia/ia-marketplace-choice-plan-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Letter from Vicki Wachino, Director, CMCS, CMS to Mikki Stier, Medicaid Director, State of Iowa (July 31, 2015), http://medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ia/ia-marketplace-choice-plan-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- CMS Special Terms and Conditions, Iowa Wellness Plan, Section VII. 41 (p. 14) (Jan. 1, 2014-Dec. 31, 2016, amended July 31, 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/ia/ia-wellness-plan-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- Letter from Eliot Fishman, Director, CMS to Joseph Moser, Medicaid Director, Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (Dec. 22, 2015), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/Healthy-Indiana-Plan-2/in-healthy-indiana-plan-support-20-response-ltr-12222015.pdf. ↩︎

- GAO at 15. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id.at 15, n.32. ↩︎

- Id. at 15. ↩︎