Understanding the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program

Issue Brief

Drug prices are at the center of health policy debates at both the state and federal levels. Medicaid provides health coverage for millions of Americans, including many with substantial health needs. Prescription drug coverage is a key component of Medicaid for many beneficiaries who rely on medications for both acute problems and for managing ongoing chronic or disabling conditions. Without Medicaid, many prescription drugs would be prohibitively expensive to low-income beneficiaries. Both state and federal policymakers are undertaking efforts to control prescription drug costs, and there is renewed policy interest in the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) as part of these efforts. Policymakers are also currently debating significant changes to payment for prescription drugs through Medicare and commercial insurers that may also have implications for Medicaid and the MDRP as well. This brief explains the MDRP to help policymakers and others understand how Medicaid pays for drugs and any potential consequences of policy changes for the program by answering the following questions:

- What is the MDRP and how does it work?

- What is the impact of the MDRP?

- What is the role of managed care plans and pharmacy benefit managers in Medicaid rebates?

- How does the 340B program interact with the MDRP?

- What are policy proposals related to the MDRP?

What is the Medicaid drug rebate program and how does it work?

In response to rising drug prices and projected increased Medicaid spending, the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) was created in 1990 by the Omnibus Reconciliation Act.1 ,2 Under the program, a manufacturer who wants its drug covered under Medicaid must enter into a rebate agreement with the Secretary of Health and Human Services stating that it will rebate a specified portion of the Medicaid payment for the drug to the states, who in turn share the rebates with the federal government. Manufacturers must also enter into agreements with other federal programs that serve vulnerable populations. In exchange, Medicaid programs cover nearly all of the manufacturer’s FDA-approved drugs, and the drugs are eligible for federal matching funds. Though the pharmacy benefit is a state option, all states cover it, but, within federal guidelines about pricing and rebates, administer pharmacy benefits in somewhat different ways.

The MDRP affects state and federal Medicaid payment for prescription drugs, while Medicaid beneficiaries’ out of pocket cost for drugs is limited to nominal amounts set in statute. Due to Medicaid’s role in financing coverage for high-need populations with low incomes, it is designed to provide access to prescription drugs with little cost to enrollees. Federal rules limit beneficiary cost-sharing to nominal amounts: up to $4 for preferred drugs and $8 for non-preferred drugs, for individuals with incomes at or below 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and slightly higher for those with higher incomes.3 Not all states impose cost-sharing for prescription drugs,4 and some beneficiary groups are exempt from cost-sharing requirements.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made significant changes to the prescription drug rebate program. The law increased the rebate amount for both brand drugs and generic drugs. It also extended rebates to outpatient drugs purchased for beneficiaries covered by Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs).5 Previously only drugs purchased through Medicaid fee-for-service were eligible for rebates even though most states contract with MCOs to provide services to Medicaid beneficiaries.6

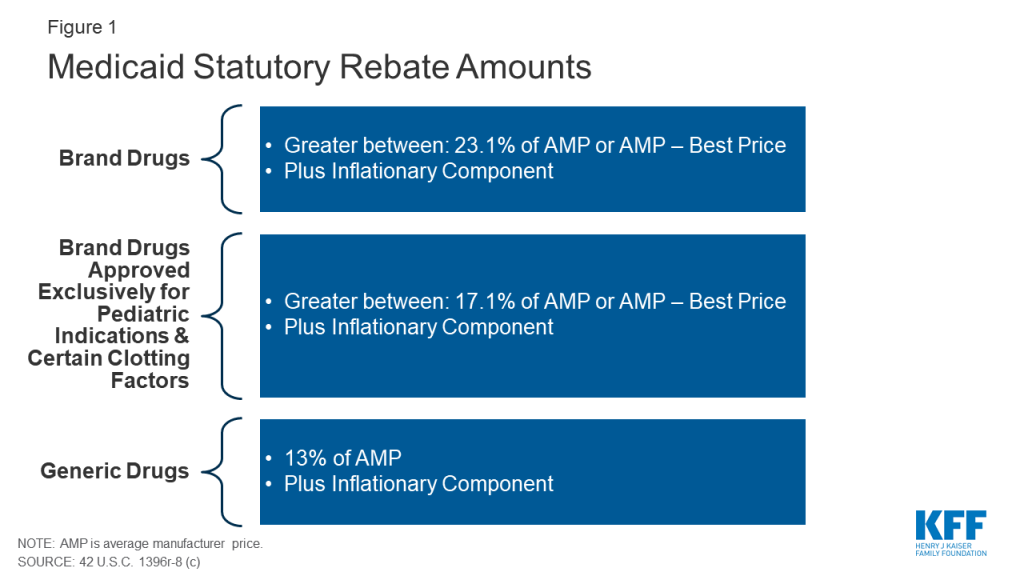

The Medicaid rebate amount is set in statute and ensures that the program gets the lowest price (with some exceptions).7 The formula for rebates varies by type of drug: brand8 or generic. The rebate formula is the same regardless of whether states pay for drugs on a fee-for-service basis or through payments to managed care plans. The specific rebate on a given drug is considered proprietary. For brand name drugs, the rebate is 23.1% of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) or the difference between AMP and “best price,” whichever is greater. Certain pediatric and clotting drugs have a lower rebate amount of 17.1% (Figure 1). Best price is defined as the lowest available price to any wholesaler, retailer, or provider, excluding certain government programs, such as the health program for veterans.9 AMP is defined as the average price paid to drug manufacturers by wholesalers and retail pharmacies.10 ,11 For generic drugs, the rebate amount is 13% of AMP, and there is no best price provision.

The rebate calculation also includes an additional inflationary component to account for rising drug prices over time. This rebate is calculated as the difference between the drug’s current quarter AMP and its baseline AMP adjusted to the current period by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).12 In other words, if a drug’s price increases faster than inflation, the manufacturer has to rebate the difference to Medicaid. The inflationary component is an increasing share of brand drug rebates, accounting for more than half of the total brand drug rebate amounts in 2012.13 Because of the inflationary component, the calculated rebate on a drug whose price increases quickly over time could be greater than the AMP for that drug. However, the total rebate amount currently is capped at 100% of AMP.14

In addition to federal statutory rebates, most states negotiate with manufacturers for supplemental rebates. As of June 2019, 47 states and DC had supplemental rebate agreements in place.15 These supplemental rebates are not subject to the best price floor. States often use placement on a preferred drug list (PDL) as leverage to negotiate supplemental rebates with manufacturers. States encourage providers to prescribe drugs on the PDL over other drugs and create incentives for them to do so if possible. For example, a state may require a prior authorization for a drug not on a preferred drug list. Often, drugs on PDLs are cheaper or include drugs for which a manufacturer has provided supplemental rebates. A few states have used their supplemental rebate authority to negotiate alternative payment models with manufacturers. States have also formed multi-state purchasing pools when negotiating supplemental Medicaid rebates to increase their negotiating power. More than half of states participate in a multi-state supplemental rebate pool.16 In addition, Medicaid managed care plans may negotiate their own supplemental rebate agreements with manufacturers.

Both states and the federal government play a role in administering the MDRP. Manufacturers must report AMP for all covered outpatient drugs to HHS and report their best price for brand name drugs. HHS uses this price data to calculate the unit rebate amount (URA) based on the rebate formula and inflationary component and provides the URA to states.17 States multiply the units of each drug purchased by the URA and invoice the manufacturer for that amount. Manufacturers then pay states the statutory rebate amount as well as any negotiated supplemental rebates.

Prescription drug rebates are shared between the federal and state governments. States and the federal government share in the statutory rebate amount based on the federal medical assistance percentages (FMAP), which is the share of Medicaid spending in each state paid for by the federal government. Manufacturers submit rebates directly to states.18 The ACA increased rebate amounts from 15.1% to 23.1% for brand drugs and from 11% to 13% for generics, but the state share is only calculated off the pre-ACA rebate amount, which means the federal government now gets a bigger share of the rebates.19

What is the role of managed care plans and pharmacy benefit managers in Medicaid rebates?

As more states have enrolled additional Medicaid populations into managed care arrangements over time, managed care organizations (MCOs) have played an increasingly significant role in administering the Medicaid pharmacy benefit. More than two-thirds of Medicaid beneficiaries received their coverage through MCOs in 2017.20 States pay MCOs a monthly fee (capitation rate) to cover the cost of services provided to enrollees and any administrative expenses. States may include all Medicaid services in these contracts or they may “carve-out” certain services, like prescription drugs, from capitation rates. Managed care plans whose contracts include coverage for prescription drugs are allowed to negotiate their own rebates with manufacturers. As with supplemental rebates negotiated by states, additional rebates for managed care plans can be used to determine placement on the PDL.

The ACA extended federal statutory rebates to prescription drugs provided under Medicaid managed care arrangements, and most states now “carve in” prescription drugs. Prior to the ACA, manufacturers only had to pay rebates for outpatient drugs purchased on a fee-for-service basis, not those purchased through managed care. This encouraged states to “carve out” prescription drugs so they would be able to get rebates. Extending rebates to drugs purchased through managed care has resulted in more states carving drug coverage back into managed care. Of the 40 states contracting with comprehensive risk-based MCOs in 2018, 35 states reported that the pharmacy benefit was carved in, with some states reporting exceptions such as high-cost or specialty drugs.21

Many states also use pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in their Medicaid prescription drug programs. PBMs perform financial and clinical services for the program, administering rebates, monitoring utilization, and overseeing preferred drug lists.22 PBMs may be used regardless of whether the state administers the benefit through managed care or on a fee-for-service basis. Some states are reassessing their use of PBMs in managed care due to issues with the lack of transparency around PBM payments and the prevalence of “spread pricing.” Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy.23 In the past, PBMs have been able to keep this “spread” as profit, but a number of states are implementing policies to curb or altogether prohibit this practice.24

How does the 340B program interact with the MDRP?

The Medicaid rebate program interacts with other programs that receive manufacturer discounts on drugs. As a condition of participation in the Medicaid Drug Rebate program, manufacturers must also participate in the federal 340B program. The 340B program offers discounted drugs to certain safety net providers that serve vulnerable or underserved populations, including Medicaid beneficiaries.25 340B ceiling prices are calculated to match Medicaid prices net of the rebate, but manufacturers can provide additional discounts to 340B providers that are not subject to the best price rule.26

Because the 340B program is administered separately, as stipulated by federal law, states and safety net providers must ensure that manufacturers do not pay duplicative discounts for Medicaid beneficiaries.27 Safety net providers eligible for 340B discounts can choose whether or not they provide drugs purchased with the program discounts to Medicaid beneficiaries within state guidelines.28 ,29 States may require providers to make the same decision for FFS and managed care enrollees to streamline the process of determining which claims are eligible for rebates. To avoid charging manufacturers a duplicate discount, state Medicaid programs reference a list of safety net providers that provided drugs under 340B to Medicaid beneficiaries, and the Medicaid program will exclude their drug claims from their invoices to manufacturers.30 The file does not include drugs paid for by managed care plans or those dispensed at contract pharmacies, but MCOs also are required to exclude 340B claims from reports they provide to states for rebate purposes.31 ,32 There are concerns the list can be out of date or inaccurate, so some states maintain their own lists or use claims data to avoid duplicate discounts. Although Medicaid best price and 340B ceiling prices are closely related, the rules states set for how they reimburse pharmacies may have implications for drug costs.33 ,34

What is the impact of the MDRP?

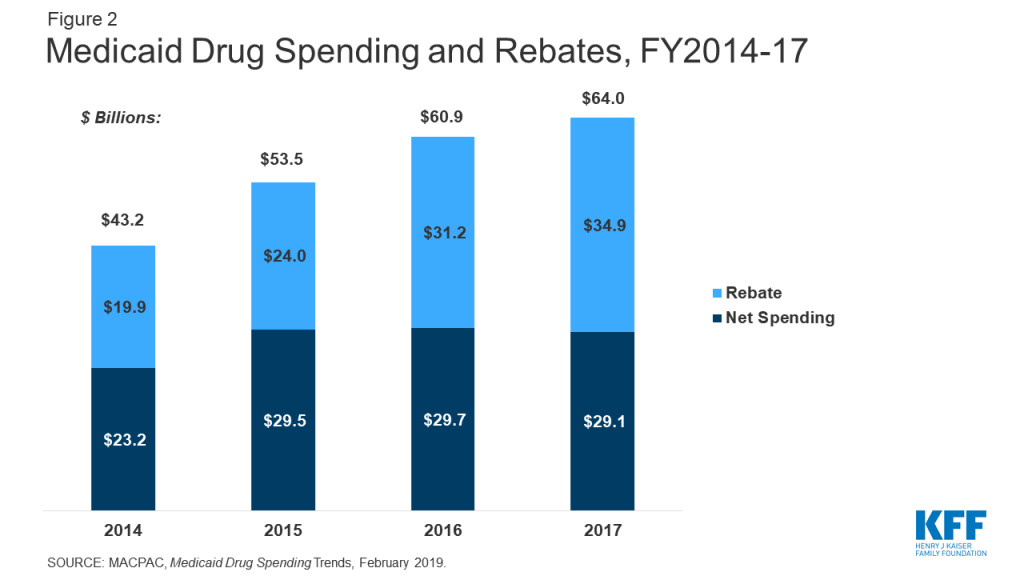

The rebate program offsets Medicaid costs and reduces federal and state spending on drugs. In 2017, Medicaid spent $64 billion on drugs and received nearly $35 billion in rebates. Net spending on outpatient drugs comprises 5% of total Medicaid benefits spending. While gross prescription drug spending has increased substantially over time (from $43 billion in 2014 to $64 billion in 2017) rebates have held net spending growth to a much lower rate (Figure 2). Gross spending on drugs increased 48% from 2014-2017, while net spending only increased 25% over the same time period. Net spending actually declined from 2016-2017.35 In comparison to other programs, like Medicare Part D, rebates in Medicaid are a much larger share of drug spending. Medicare actuaries predicted Medicare Part D rebates to reach 23% of drug spending in 2017 and 25% in 2018.36 In contrast, Medicaid rebates accounted for 55% of drug spending in 2017.

The structure of the rebate program essentially creates an open formulary. When a manufacturer enters into a rebate agreement with HHS, Medicaid agrees to cover nearly all FDA-approved drugs from that manufacturer. This approach is different from private insurers who can enter into negotiations with manufacturers about whether or not drugs will be on their formularies, leveraging rebates for drugs that are included or covered with lower patient cost-sharing. While the Medicaid rebate structure enables beneficiaries to access a wide range of drugs, it also places some limits on states’ ability to negotiate with manufacturers. This challenge is particularly acute for new, blockbuster drugs that Medicaid programs must cover with little leverage to negotiate lower costs.

Medicaid prices and the rebate program may have implications for prices paid by other payers. There has been increased attention by policymakers and the public to high list prices, with some brand name drugs launching with price tags of hundreds of thousands of dollars or more. Amidst the discussion of high launch prices, analyses of potential solutions have highlighted the role of the MDRP in the larger drug pricing system. Some have suggested that the “best price” provision and the rebate requirements inflate launch prices to account for the rebate and reduce rebates for other payers (like private insurers) to avoid triggering the best price provision. Medicare Part D rebates are not included in the best price calculation. An analysis from CBO was conducted in 1996, shortly after the creation of the Rebate Program, and showed some initial price increases but found increases due to MDRP ceased within a few years.37 In analyzing the potential impact of the ACA rebate provisions, which increased the rebate amount, CBO estimated a small impact on launch prices.38

What are policy debates and proposals about the MDRP?

There is renewed policy interest in the MDRP as states and the federal government explore policies related to drug costs. Proposals at both the state and federal level would make changes directly to the MDRP, and proposed changes to other programs may have implications for Medicaid as well.

Increasing the Effective Rebate Amount in the MDRP

Because the MDRP is a complex program that has evolved over time, it contains some technical issues and provisions that lower the rebate amount paid for some drugs. Policymakers are considering several changes to address these issues and increase the effective rebate amount. While these changes would produce savings for both the federal and state government, authority for undertaking them rests at the federal level, since the MDRP is in federal statute.

One proposed approach is to lift the cap on rebates, which is currently 100% of AMP. Because of rising prices over time, a number of drugs have reached the rebate cap. Increasing or eliminating the cap would generate savings for the program and lower revenues for drug manufacturers.39 The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Advisory Commission (MACPAC) recommended eliminating the cap entirely.40 A bipartisan bill addressing drug costs passed out of the Senate Finance Committee includes a provision to increase the cap to 125% of AMP.

Another policy proposal to increase the Medicaid rebate amount is to change the rebate calculation. Some manufacturers have reduced their rebate obligations by blending the price of an authorized generic with a brand name drug, which reduces the AMP of the brand drug. This occurs when a brand drug manufacturer also produces the authorized generic and the price of both drugs is included in the brand drug’s AMP. Because the rebate calculation is based on AMP, an artificially low AMP reduces the rebate a manufacturer pays. Legislation enacted in Fall 2019 prohibits manufacturers from engaging in this practice.41 ,42 Preventing this practice is projected to save about $3.1 billion over the next decade.43 ,44

A third set of technical changes to MDRP relates to data and reporting. The rebate calculation relies on price data and product information submitted by manufacturers to CMS. Misclassified drugs or inaccurate price information in these files affects the rebate calculation. A number of policy proposals would strengthen price enforcement mechanisms at the federal level to improve the accuracy of information and ensure appropriate rebates are paid and allow for penalties for reporting inaccurate information. Proposals include providing the Secretary of HHS with the authority to reclassify drugs that are incorrectly classified, increasing oversight of rebates by requiring CMS to conduct regular audits of drug manufacturers’ pricing information, providing the Secretary additional authority to impose a penalty on manufacturers that submit inaccurate information and increasing the penalties for not complying with reporting requirements.45 ,46

Increasing Supplemental Rebates

Due to the structure of the MDRP, state levers to negotiate supplemental rebate agreements have primarily been limited to PDL placement. In addition, as statutory rebates have increased over time, state supplemental rebates have grown much more slowly and declined as a share of total rebates.47 ,48 In recent years, states have been exploring new approaches to try to obtain larger supplemental rebates from manufacturers.

Some policy proposals focus on increasing purchasing power to negotiate additional supplemental rebates. For example, aligning PDLs across FFS and MCOs may provide more leverage for a state negotiating with a manufacturer. As of fiscal year 2019, at least 17 states had a uniform PDL for one or more drug classes.49 California has proposed negotiating rebates across all state programs, not just Medicaid.50

PBMs have been another area of focus for state efforts to increase supplemental rebates. Much activity in this area involves increased transparency about PBM practices by, for example, requiring PBMs to report their discounts, rebates and profits to the state to ensure that the state is receiving the maximum rebates possible. More than half of states have passed a law addressing some aspect of PBM practices and transparency.51 Other states have enacted or are considering broader transparency laws to obtain pricing information from manufacturers in an effort to better understand prices paid by different parties in the production and payment chain for prescription drugs.

Other state efforts include expanding the scope of supplemental rebates—for example, by extending supplemental rebates to MCOs—or adding an inflationary component to supplemental rebates.52 ,53

Value-Based Purchasing

A final way in which states have been pursuing supplemental rebates is through value-based purchasing. With the increasing number of high-price, breakthrough drugs that cost hundreds of thousands up to millions of dollars, states are examining ways to pay for these therapies within their constrained budgets. Some states are pursuing alternative payment methods, or paying for value, as possible solutions. States have authority to pursue these agreements, but they must fit within the parameters of the MDRP. Given the best price provision, which leads manufacturers to hesitate to offer lower prices, states have opted to craft their arrangements under the umbrella of supplemental rebates, which are exempt from best price. While referred to colloquially as “value-based payment,” most agreements so far do not condition payment on clinical outcomes.

As of October 2019, six states have approval to implement alternative payment models via supplemental rebates.54 These states include Louisiana and Washington, both of which are implementing a subscription model (also known as the “Netflix model”) to pay for hepatitis C drugs. Some legislative proposals would provide further authority for states to enter into risk-sharing, value-based contracts with manufacturers for outpatient drugs that are potentially curative treatments.55 ,56 These agreements would be treated like supplemental rebates for the purpose of calculating AMP and best price.

Opting Out of the MDRP

Some policy discussion in recent years has been about opting out of or eliminating the MDRP, which essentially creates an open formulary, to allow states to use closed formularies in Medicaid, under which only specific drugs in each therapeutic class are covered. Some argue that allowing states to implement these “widely-used commercial tools”57 would allow states to negotiate greater rebates, because each manufacturer would want their drug to be included as one of the few drugs for the therapeutic class. The Trump Administration has expressed interest in this approach, and the FY 2019 budget called for a new Medicaid demonstration authority to enable up to five state Medicaid programs to create their own formularies and negotiate directly with manufacturers instead of participating in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.58 ,59 States are showing limited interest in the idea, though some states have expressed interest in a closed formulary that still obtains MDRP rebates.60 ,61 However, as of October 2019, the federal government has not approved waiver requests for this approach.62

Changing Rebates or Prices in Other Programs

While not specifically targeted to Medicaid or MDRP, policy proposals to change the structure of rebates or prices in Medicare and the private market also affect Medicaid. These indirect effects occur because many proposals affect list prices or AMP, which in turn affect Medicaid rebate calculations. For example, in early 2019, the Trump administration released a proposed rule that would have excluded rebate payments by drug manufacturers to PBMs, Medicare Part D plan sponsors, and Medicaid managed care organization (MCO) plan sponsors from “safe harbor” protections that make these payments exempt from anti-kickback penalties. The Administration withdrew the idea, but analyses of the proposal at the time indicated that it would increase Medicaid spending. This outcome would occur through decreased list prices by manufacturers, which would lower the inflationary Medicaid rebate.63 Similarly, proposals (such as those made by the Administration64 and by House Democrats) to align Medicare drug prices more closely with drug prices in other countries could have implications for Medicaid rebates and ultimately Medicaid drug spending by changing drug list prices. Policy changes that would allow the federal government to negotiate Medicare prices also may have implications for Medicaid, depending on how the price applies to the wider marketplace and the prices used to set Medicaid rebates.65

Summary

The MDRP helps offset federal and state costs of most outpatient prescription drugs dispensed to Medicaid beneficiaries and ensures access to medication for Medicaid beneficiaries. While gross prescription drug costs continue to grow, the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program has held net Medicaid costs largely flat over the past few years. There continues to be growing national attention around the issue of high drug prices and as a result, both states and the federal government are considering a variety of policies to address prescription drug costs. Because of the key role Medicaid plays in providing drugs for beneficiaries and setting the floor for prices, it is important for policy makers to understand the implications of any proposed policies for the rebate program.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Endnotes

- United States Senate Special Committee on Aging, Prescription Drug Pricing: Are We Getting Our Money’s Worth? (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989), https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/reports/rpt289.pdf. ↩︎

- Ramsey Baghdadi, “Medicaid Best Price,” Health Affairs (August 2017), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20171008.000173/full/. ↩︎

- For individuals with incomes above 150% of the FPL, rules allow states to establish higher cost sharing, including coinsurance of up to 20% of the cost of the drug, for non-preferred drugs. See 78 Federal Register 42159-42322 (July 15, 2013), and Laura Snyder and Robin Rudowitz, Premiums and Cost-sharing in Medicaid (Kaiser Family Foundation, February 2013), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/premiums-and-cost-sharing-in-medicaid-a-review-of-research-findings/. ↩︎

- State Health Facts, “Medicaid Benefits: Prescription Drugs, 2018,” KFF, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/prescription-drugs. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396b (m)(2)(A)(xiii) ↩︎

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicaid’s Prescription Drug Benefit: Key Facts (KFF, May 2019), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaids-prescription-drug-benefit-key-facts/. ↩︎

- Medicaid statute defines Best Price as “the lowest price available from the manufacturer during the rebate period to any wholesaler, retailer, provider, health maintenance organization, nonprofit entity, or government entity within the United States.” There are many important exclusions, including the Department of Veterans Affairs, the 340B program, the Department of Defense, the Public Health Service, the Indian Health Service. The Best Price includes rebates in general, but not Medicaid supplemental rebates or rebates provided through the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. 42 U.S.C. 1396r-8 (c)(1)(C). ↩︎

- Single source drugs and multiple source innovator drugs are those approved under a “new drug” application with the FDA. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (c) (1)(C) ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (k) (1)(A) ↩︎

- This price does include discounts provided to retail pharmacies but does not include service fees or rebates or discounts to other purchasers (like MCOs and PBMs), see 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (k) (1)(B). ↩︎

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, Medicaid Payment for Outpatient Prescription Drugs (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Medicaid-Payment-for-Outpatient-Prescription-Drugs.pdf. ↩︎

- Office of the Inspector General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Medicaid Rebates for Brand-name Drugs Exceeded Part D Rebates by a Substantial Margin, OEI-03-13-00650 (HHS OIG, April 2015), https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-13-00650.pdf. ↩︎

- Due to rising costs over time, some rebates could exceed 100% of AMP. ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Pharmacy Supplemental Rebate Agreements (SRA), As of June 2019,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/prescription-drugs/downloads/xxxsupplemental-rebates-chart-current-qtr.pdf. ↩︎

- Richard Cauchi, Pharmaceutical Bulk Purchasing (National Council of State Legislatures, May 2019), http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/bulk-purchasing-of-prescription-drugs.aspx. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (b) (3) ↩︎

- States retain a portion of the rebate based on their FMAP, and the remainder that is owed to the federal government is subtracted from federal payments to states. ↩︎

- This includes the state share. See Cindy Mann, “Re: Medicaid Prescription Drugs, Methodology for Calculating the Estimated Quarterly Rebate Offset Amount,” CMS, https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD10019.pdf. ↩︎

- State Health Facts, “Total Medicaid MCO Enrollment, 2017”, KFF, https://modern.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-medicaid-mco-enrollment/. ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Barbara Coulter Edwards, Aimee Lashbrook, Elizabeth Hinton, Larisa Antonisse, and Robin Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2018-and-2019/. ↩︎

- States that use PBMs in administering the prescription drug benefit in a fee-for-service setting pay the PBM administrative fees for these services. See Magellan Health, Medicaid Pharmacy Trend Report, Second Edition (Magellan Rx Management, 2017), https://www1.magellanrx.com/media/671872/2017-mrx-medicaid-pharmacy-trend-report.pdf. ↩︎

- Sarah Lanford and Maureen Hensley-Quinn, New PBM Laws Reflect States’ Targeted Approaches to Curb Prescription Drug Costs (National Academy for State Health Policy, August 2019), https://nashp.org/new-pbm-laws-reflect-states-targeted-approaches-to-curb-prescription-drug-costs/. ↩︎

- Lanford and Hensley-Quinn, New PBM Laws Reflect States’ Targeted Approaches to Curb Prescription Drug Costs (NASHP, August 2019), https://nashp.org/new-pbm-laws-reflect-states-targeted-approaches-to-curb-prescription-drug-costs/. ↩︎

- Eligible covered entities include the following: federally qualified health centers, federally qualified health center look-alikes, native Hawaiian health centers, tribal/urban Indian health centers, Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program grantees, children’s hospitals, critical access hospitals, disproportionate share hospitals, freestanding cancer hospitals, rural referral centers, sole community hospitals, black lung clinics, comprehensive hemophilia diagnostic treatment centers, Title X family planning clinics, sexually transmitted disease clinics, and tuberculosis clinics. See MACPAC, The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact (MACPAC, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/340B-Drug-Pricing-Program-and-Medicaid-Drug-Rebate-Program-How-They-Interact.pdf. ↩︎

- Mike McCaughan, “The 340B Drug Discount Program, Health Affairs (September 2017), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20171024.663441/full/. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1396r-8 (a) (5) ↩︎

- Providers can choose whether they “carve in” — use drugs purchased under the 340B program for Medicaid beneficiaries — or “carve out” — the provider does not use drugs purchased under 340B and the drugs are eligible for the Medicaid Rebate Program. HRSA uses a Medicaid Exclusion File to track drugs purchased under 340B but, this method only applies to FFS Medicaid. States must have their own methods for managed care beneficiaries. See Office of Pharmacy Affairs, Clarification on Use of the Medicaid Exclusion File (HHS Health Resources and Services Administration, December 2014), https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/opa/programrequirements/policyreleases/clarification-medicaid-exclusion.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact (MACPAC, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/340B-Drug-Pricing-Program-and-Medicaid-Drug-Rebate-Program-How-They-Interact.pdf. ↩︎

- The Medicaid Exclusion File (MEF) is maintained by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). See MACPAC, The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact (MACPAC, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/340B-Drug-Pricing-Program-and-Medicaid-Drug-Rebate-Program-How-They-Interact.pdf. ↩︎

- 42 Federal Register 27497-27901, (May 6, 2016). ↩︎

- HRSA guidance states that contract pharmacies are prohibited from dispensing 340B drugs to Medicaid beneficiaries unless the covered entity, contract pharmacy, and Medicaid agency establish “an arrangement to prevent duplicate discounts” and notify HRSA of the arrangement. See Office of Pharmacy Affairs, Clarification on Use of the Medicaid Exclusion File (HHS Health Resources and Services Administration, December 2014), https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/opa/programrequirements/policyreleases/clarification-medicaid-exclusion.pdf. ↩︎

- The Covered Outpatient Drug final rule requires states to reimburse 340B covered entities at actual acquisition cost (AAC) plus a professional dispensing fee (PDF) up to the 340B ceiling price. AAC for 340B drugs may be lower than Medicaid prices but these “below-ceiling” prices may be difficult for states to obtain. The AAC requirement only applies to FFS Medicaid drugs, drugs covered by MCOs in Medicaid are not subject to this requirement. See 81 Federal Register 5169-5357, (February 1, 2016) and CMS, Covered Outpatient Drug Final Rule with Comment (CMS-2345-FC) Frequently Asked Questions (CMS, July 2016), https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/faq070616.pdf. ↩︎

- For covered entities that carve in to 340B, the AAC would generally be the 340B ceiling price. There is some potential for spread pricing in Medicaid if a covered entity purchases drugs at sub-ceiling prices. See MACPAC, The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact (MACPAC, May 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/340B-Drug-Pricing-Program-and-Medicaid-Drug-Rebate-Program-How-They-Interact.pdf. ↩︎

- Totals include state and federal spending. See MACPAC, Medicaid Drug Spending Trends (MACPAC, February 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Medicaid-Drug-Spending-Trends.pdf. ↩︎

- Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, 2018 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds (CMS, June 2018), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2018.pdf. ↩︎

- Congressional Budget Office, How the Medicaid Rebate on Prescription Drugs Affects Pricing in the Pharmaceutical Industry (CBO, January 1996), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/104th-congress-1995-1996/reports/1996doc20.pdf ↩︎

- Douglas W. Elmendorf, Letter to Hon. Paul Ryan, Ranking Member on the Committee on the Budget (Congressional Budget Office, November 2010), https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/reports/11-04-drug_pricing.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Next Steps in Improving Medicaid Prescription Drug Policy (MACPAC, June 2019), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Next-Steps-in-Improving-Medicaid-Prescription-Drug-Policy.pdf. ↩︎

- Fair AMP Act, H.R.3276, 116th Congress (2019). ↩︎

- Continuing Appropriations Act, 2020, and Health Extenders Act of 2019, H.R.4378, 116th Congress (2019). ↩︎

- CBO, Proposals Affecting Health Programs in Budget Function 550 – CBO’s Estimate of the President’s Fiscal Year 2020 Budget (CBO, May 2019), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/55208-healthprograms.pdf. ↩︎

- Jay Hancock and Sydney Lupkin, “Drugmakers Master Rolling Out Their Own Generics To Stifle Competition,” Kaiser Health News (August 5, 2019), https://kffhealthnews.org/news/drugmakers-now-masters-at-rolling-out-their-own-generics-to-stifle-competition/. ↩︎

- MACPAC, Improving Operations of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MACPAC, June 2018), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Improving-Operations-of-the-Medicaid-Drug-Rebate-Program.pdf. ↩︎

- MACPAC recommendations include providing the Secretary with the authority to reclassify drugs that are incorrectly classified as well as to levy intermediate monetary penalties. The Senate Finance Committee Bill would increase oversight of rebates by requiring CMS to conduct regular audits of drug manufacturers’ pricing information and submit those audits to Congress. The Secretary of HHS would have the authority to impose a penalty on manufacturers that submit inaccurate information and would increase penalties for not complying with reporting requirements. See: https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL%20Description%20of%20the%20Chairman’s%20Mark%20for%20the%20Prescription%20Drug%20Pricing%20Reduction%20Act%20of%202019.pdf. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of CMS-64 data. ↩︎

- Office of Inspector General, HHS, States’ Collection of Offset and Supplemental Medicaid Rebates (HHS OIG, December 2014), https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-12-00520.pdf. ↩︎

- Gifford, Ellis, Edwards, Lashbrook, Hinton, Antonisse, and Rudowitz, States Focus on Quality and Outcomes Amid Waiver Changes: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019 (KFF, October 2018), https://modern.kff.org/report-section/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-pharmacy-and-opioid-strategies/. ↩︎

- Gabriel Petek, The 2019-20 Budget: Analysis of the Carve Out of Medi-Cal Pharmacy Services From Managed Care (California State Legislative Analyst’s Office, April 2019), https://lao.ca.gov/Publications/Report/3997. ↩︎

- Lanford and Hensley-Quinn, New PBM Laws Reflect States’ Targeted Approaches to Curb Prescription Drug Costs (NASHP, August 2019), https://nashp.org/new-pbm-laws-reflect-states-targeted-approaches-to-curb-prescription-drug-costs/. ↩︎

- Pew Charitable Trusts, Use of State Medicaid Inflation Rebates Could Discourage Drug Price Increases (Pew, June 2018), https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/06/implementingstatemedicaidinflationrebatescoulddiscouragedrugpriceincreases_factsheet.pdf. ↩︎

- An Act to Improve Health Care by Investing in Value, Massachusetts Bill H.4134, 191st Legislature (2019). ↩︎

- Two states have moved forward with a subscription-based model: Louisiana reached an agreement with Gilead to treat more than 31,000 people in the state with hepatitis C under a modified subscription model over the next five years. The agreement allows the state to cap gross spending at a fixed amount. Washington state received approval from CMS to negotiate a fixed annual amount to pay for hepatitis C drugs and entered into a contract with AbbVie. Oklahoma has executed four alternative payment model agreements with manufacturers related to financial outcomes, including adherence, costs and hospitalizations. If the drug fails to meet certain benchmarks, the manufacturer will make additional payments to the state in the form of a supplemental rebate. Massachusetts, Colorado, and Michigan have received approval from CMS to enter into value or outcomes-based supplemental rebate agreements with drug manufacturers. ↩︎

- U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, Description of the Chairman’s Mark: The Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act (PDPRA) of 2019 (Senate Finance, July 2019), https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL%20Description%20of%20the%20Chairman’s%20Mark%20for%20the%20Prescription%20Drug%20Pricing%20Reduction%20Act%20of%202019.pdf. ↩︎

- Rachel Sachs, “Understanding the Senate Finance Committee’s Drug Pricing Package,” Health Affairs (July 26, 2019), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190726.817822/full/. ↩︎

- Office of Medicaid, Executive Office of Health and Human Services, MassHealth Section 1115 Demonstration Amendment Request (Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOHHS, Office of Medicaid, September 2017), https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/10/27/masshealth-section-1115-demonstration-amendment-request-09-08-17.pdf. ↩︎

- Prices negotiated through this demonstration would be exempt from Best Price. These states would also maintain an appeals process for non-covered drugs. ↩︎

- HHS, Putting America’s Health First: FY 2019 President’s Budget for HHS (HHS, February 2018), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2019-budget-in-brief.pdf. ↩︎

- Office of Medicaid, EOHHS, MassHealth Section 1115 Demonstration Amendment Request (Commonwealth of Massachusetts EOHHS, Office of Medicaid, September 2017), https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/10/27/masshealth-section-1115-demonstration-amendment-request-09-08-17.pdf. ↩︎

- Division of TennCare, TennCare II Demonstration: Amendment 42 DRAFT (Division of TennCare, September 2019), https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents2/TennCareAmendment42.pdf. ↩︎

- Virgil Dickson, “CMS denies Massachusetts’ request to choose which drugs Medicaid covers,” Modern Healthcare (June 27, 2018), https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180627/NEWS/180629925/cms-denies-massachusetts-request-to-choose-which-drugs-medicaid-covers. ↩︎

- CBO, Incorporating the Effects of the Proposed Rule on Safe Harbors for Pharmaceutical Rebates in CBO’s Budget Projections (CBO, May 2019), https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-05/55151-SupplementalMaterial.pdf. ↩︎

- 83 Federal Register 54546-54561, (October 30, 2018). ↩︎

- Office of the Actuary, Financial Impact of Titles I and II of H.R. 3, “Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019 (CMS, October 2019), https://www.scribd.com/document/429847530/HR3-TitleI-II-Memo. ↩︎