The Role of Community Health Centers in Addressing the Opioid Epidemic

Issue Brief

Executive Summary

Community health centers play an important role in efforts to address the opioid epidemic. In many communities, they are on the front lines of the epidemic and have become an important source of treatment for those with opioid use disorder (OUD). This issue brief presents findings from a 2018 survey of community health centers on health center activities related to the prevention and treatment of OUD. Survey responses indicated that health centers have expanded treatment services in response to the escalating crisis, yet treatment capacity challenges remain. Additionally, health centers in Medicaid expansion states seem to be more equipped to respond to the epidemic in their states than are those in non-expansion states. Key findings include:

- Most health centers reported an increase in the number of patients with OUD in the past three years. Nearly seven in ten said they saw more patients with prescriptiion OUD while 63 percent said the number of patients with nonprescription OUD had increased.

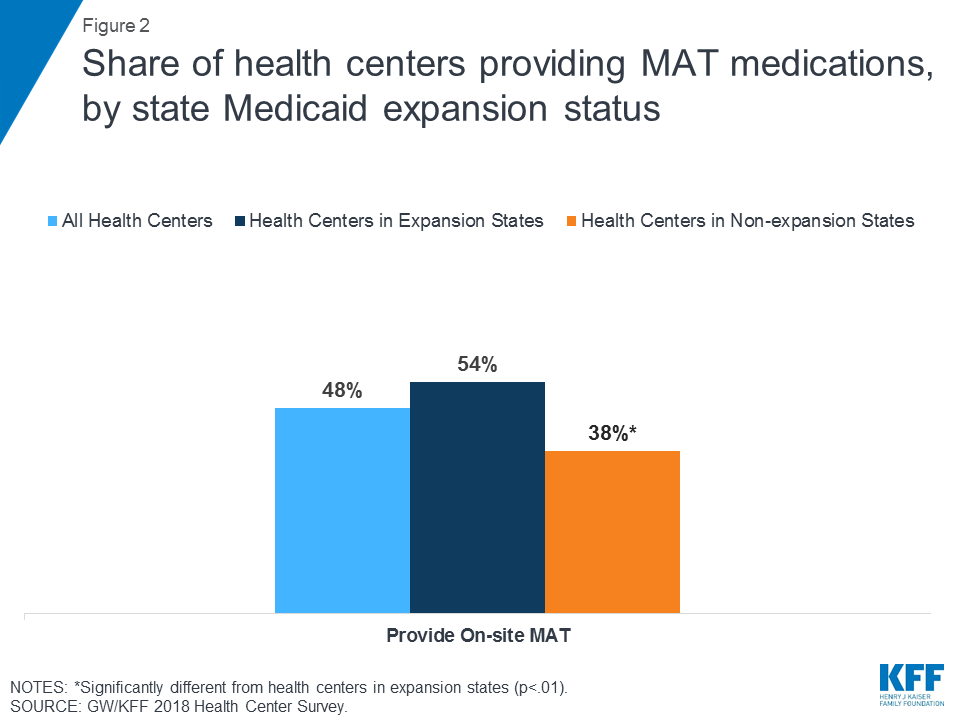

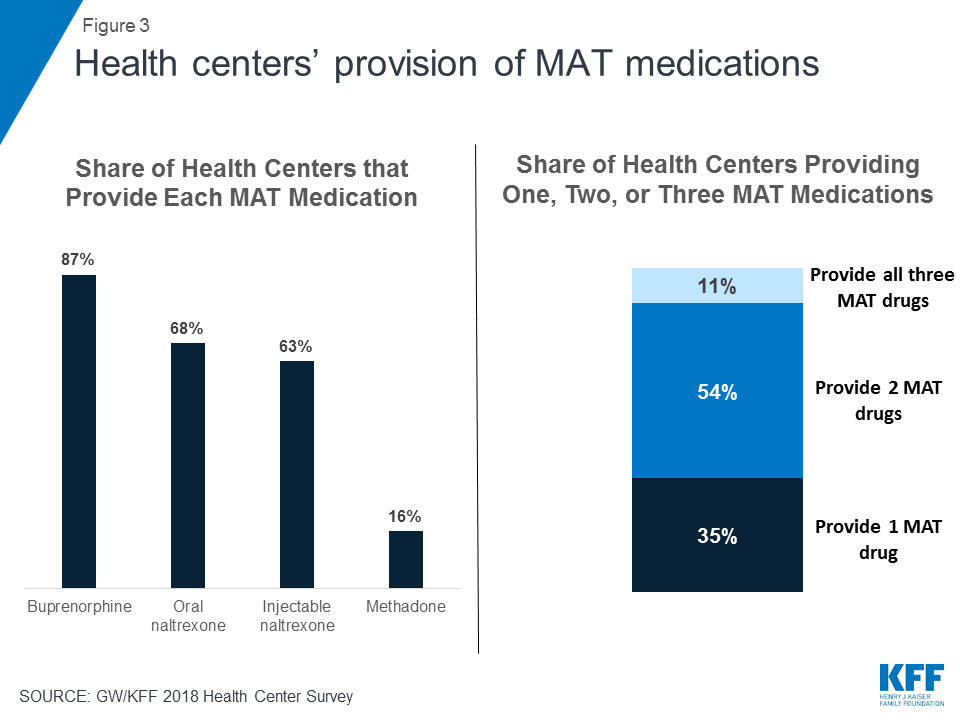

- Nearly half (48%) of health centers provide medications as part of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), considered to be the most effective OUD treatment. Among health centers that provide MAT, nearly two-thirds (65%) offer at least two of the three MAT medications. Buprenorphine is the most commonly prescribed MAT medication, available at 87 percent of health centers that provide MAT, and 71 percent of health centers have increased the number of providers who have waivers to prescribe it.

- Health centers in Medicaid expansion states are more likely to provide MAT than those in non-expansion states (54% vs. 38%).They are also more likely to provide injectable naltrexone, a longer-acting MAT medication.

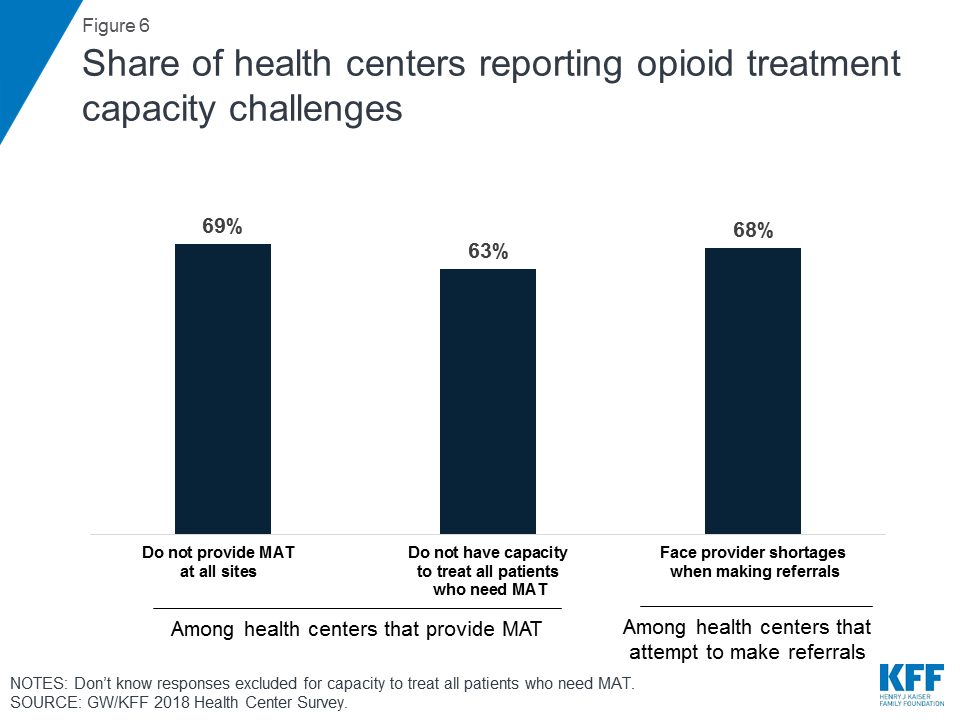

- Health centers face many treatment capacity challenges in responding to the opioid epidemic. Among those that provide MAT, 69 percent do not provide MAT services at all of their sites, and 63 percent report not having the capacity to treat all patients with OUD. Among health centers that attempt to refer patients for MAT services, 68 percent said they face provider shortages when doing so.

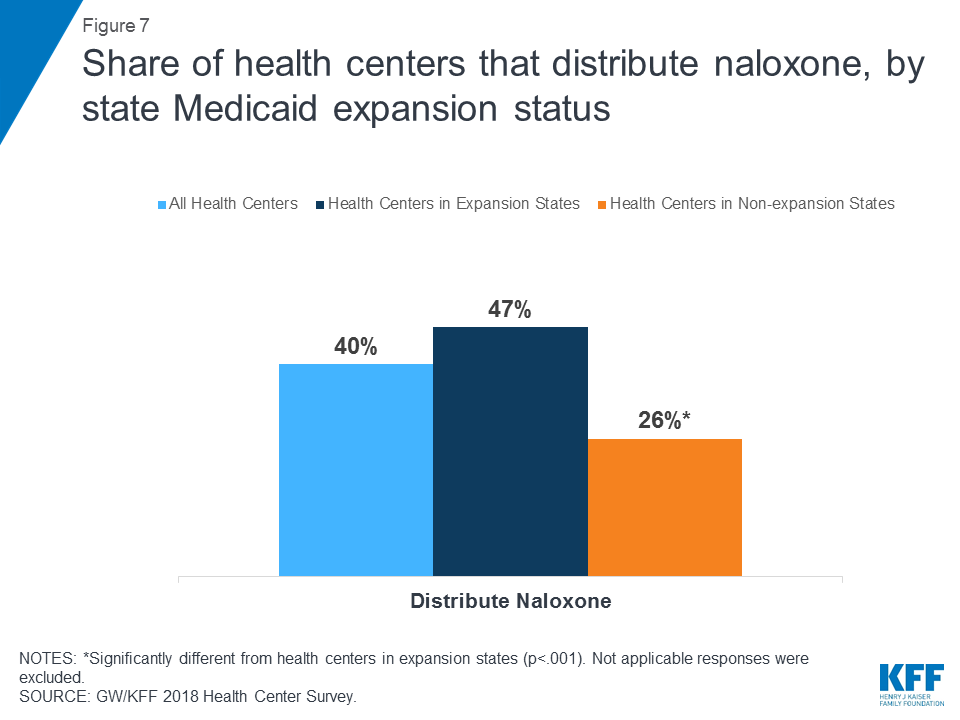

- Many health centers (40%) distribute naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug. Those in expansion states are nearly twice as likely as those in non-expansion states to provide the drug (47% vs. 26%).

Health centers play a critical role in addressing the opioid epidemic and many rely on Medicaid, especially in expansion states, to increase their ability to respond to the crisis.

Introduction

Community health centers are on the front lines of addressing the opioid epidemic, which affected two million Americans and resulted in 42,249 opioid overdose deaths in 2016.1 Health centers are located in medically underserved rural and urban areas, where the impact of the opioid epidemic has been especially devastating. As providers of comprehensive primary care services, they are increasingly meeting the treatment needs of their patients with substance use disorders (SUD), including those with OUD. The share of health centers providing SUD services has risen. In 2016, 388 (28%) health centers provided these services, which was a substantial increase from 20 percent in 2010.2 Health centers also remove affordability barriers to accessing needed treatment services, particularly for people with OUD who are more likely to have low incomes compared to the general population and are disproportionately covered by Medicaid or are uninsured.3

Based on a survey of health centers conducted in early 2018, this brief presents findings on health center activities related to the prevention and treatment of OUD as well as health centers’ provision of medication for opioid overdose reversal. This brief includes data from these survey questions and discusses the differences between opioid-related activities at health centers in Medicaid expansion states and in non-expansion states.

Opioid Use Disorder among Health Center Patients

Many health centers reported increases in the number of patients with OUD in the previous three years. Over seven in 10 (73%) health centers reported an increase in any opioid use disorder (Figure 1). Health centers were more likely to report an increase in the number of patients with an addiction to prescription opioids (69%) than they were to report an increase in the number of patients with an addiction to nonprescription opioids, such as heroin or fentanyl (63%) (Figure 1). These findings are consistent with national trends, which show substantial increases in the prevalence of OUD in recent years.4

Health centers in Medicaid expansion states were more likely to report an increase in the number of patients with OUD than those in non-expansion states; however, this difference disappears when limiting the comparison to health centers in states hard hit by the epidemic. Over three-quarters (76%) of health centers in expansion states reported an increase in the number of patients with an addiction to opioids, compared to two-thirds (67%) of health centers in non-expansion states. When limiting this analysis to states that were hit especially hard by the opioid epidemic, defined as those with above-average opioid overdose rates, the difference in the share of health centers reporting increases in opioid use disorder between those in expansion and non-expansion states was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that the observed differences between health centers in expansion and non-expansion states likely reflect geographic trends in the prevalence of OUD, which has hit Appalachia and parts of New England particularly hard. Many states in these regions have expanded Medicaid.5 Additionally, health centers in expansion states may be seeing an increasing number of patients with OUD as more people seek treatment, in part due to broad Medicaid coverage of treatment services and efforts by these health centers to expand access to these services.

Opioid Use Disorder Treatment at Health Centers

Staffing and Service Patterns

Provision of on-site SUD services at health centers has increased considerably in recent years. As the opioid epidemic has intensified, health centers have responded by adding or expanding SUD services. SUD services are defined in the Uniform Data System (UDS) as those that are provided by SUD workers, including “psychiatric nurses, psychiatric social workers, mental health nurses, clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, family therapists and other individuals providing alcohol or drug use disorder counseling and/or treatment services.”6 From 2010 to 2016, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) health center staff providing SUD services increased 36 percent from 854 to 1,163, and the number of patients receiving these services increased 43 percent from 98,760 to 141,569.7

It should be noted, however, that these numbers likely underestimate the true magnitude of on-site SUD service provision at health centers. The UDS does not include SUD services provided by physicians and advanced practice clinicians in these totals, and instead codes them as medical visits.8 Additionally, some health centers may also classify visits for both mental health and SUD services as “mental health visits” for purposes of UDS reporting.

Provision of Medication-Assisted Treatment

Health centers are addressing the opioid epidemic by providing on-site MAT services, particularly in Medicaid expansion states. MAT, which includes counseling along with one of three medications (methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone), is the standard of care for the treatment of OUD.9 Nearly half (48%) of health centers provide MAT medications and the large majority of these health centers provide counseling as well (Figure 2). Health centers in Medicaid expansion states are significantly more likely than those in non-expansion states to provide on-site MAT services (54% vs. 38%). This finding holds even among health centers in states hit especially hard by the opioid epidemic (63% vs. 40%) (Appendix Table 1). These differences are likely related to more sustainable Medicaid reimbursement for services in expansion states enabling health centers to provide a broader array of services,10 including MAT. Workforce shortages and regulatory barriers in some states may also be factors.

Most health centers that provide MAT services provide more than one medication. Among health centers that provide MAT services, roughly one in 10 (11%) offer all three MAT medications–methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone (oral and/or injectable). Over half (54%) offer two MAT drugs, while roughly a third (35%) offer only one drug (Figure 3). Buprenorphine is the most widely available MAT drug, with 87 percent of health centers that provide MAT medications reporting they provide it. Slightly smaller shares report providing oral naltrexone (68%) or injectable naltrexone (63%), while fewer than one in five (16%) provide methadone (Figure 3). Facilities must be certified as opioid treatment programs in order to dispense methadone, while buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in any setting.11 Additionally, all state Medicaid programs cover buprenorphine12 and almost all (49) cover naltrexone,13 while only 36 state programs cover methadone.14 As part of a broader initiative to combat the opioid epidemic, the Trump administration included a proposal to require states to cover all three MAT drugs, although it has not yet been implemented.15

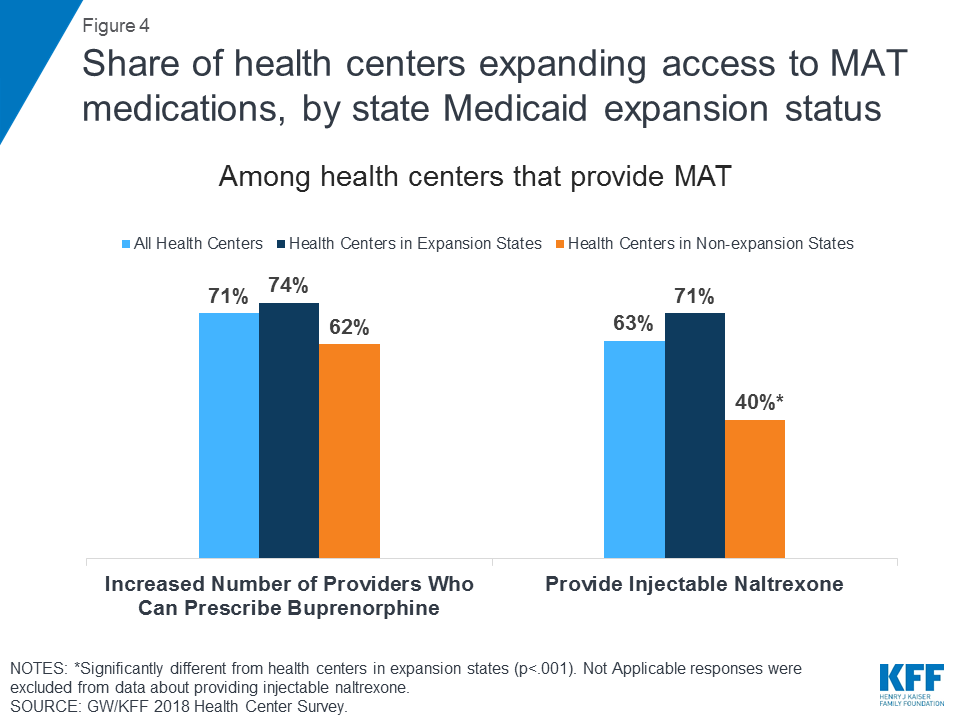

As the opioid epidemic has worsened, health centers have increased access to buprenorphine to treat OUD. Over seven in ten health centers that provide MAT have increased the number of providers who are able to prescribe buprenorphine in the past year (Figure 4). Because buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist, providers must obtain a Drug Abuse Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA) waiver from the federal government and complete additional training requirements in order to prescribe it.16 In 2016, health centers reported 1,700 on-site or contracted physicians with a data waiver and 39,075 patients who received MAT from a physician with a DATA waiver.17 Previously, only physicians could obtain a DATA waiver, but the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA), enacted in 2016, enables physician assistants and nurse practitioners to obtain waivers as well.18

Compared to health centers in non-expansion states, those in expansion states are significantly more likely to provide injectable naltrexone. In 2018, among health centers that provide MAT, 40 percent of health centers in non-expansion states provided injectable naltrexone compared to 71 percent of health centers in expansion states (Figure 4). Similar trends were observed when examining only health centers in hard-hit states (45% vs. 78%) (Appendix Table 1). Providing naltrexone is more expensive than providing other MAT drugs,19 and that may be a factor limiting its availability at health centers in non-expansion states. While Medicaid covers naltrexone in nearly all states, fewer patients receiving MAT services at health centers in non-expansion states are likely to be covered by Medicaid.20 Naltrexone is advantageous in that it does not have to be prescribed in a certified opioid treatment program and providers do not have to obtain waivers to prescribe it, though patients have to detox fully from opioids before they can be given naltrexone. Furthermore, injectable naltrexone only has to be administered once per month, which has been shown to increase patients’ treatment adherence.21 Therefore, health centers, particularly those in expansion states, play an important role in facilitating access to injectable naltrexone and ultimately helping to curb the opioid epidemic.

Provider Training

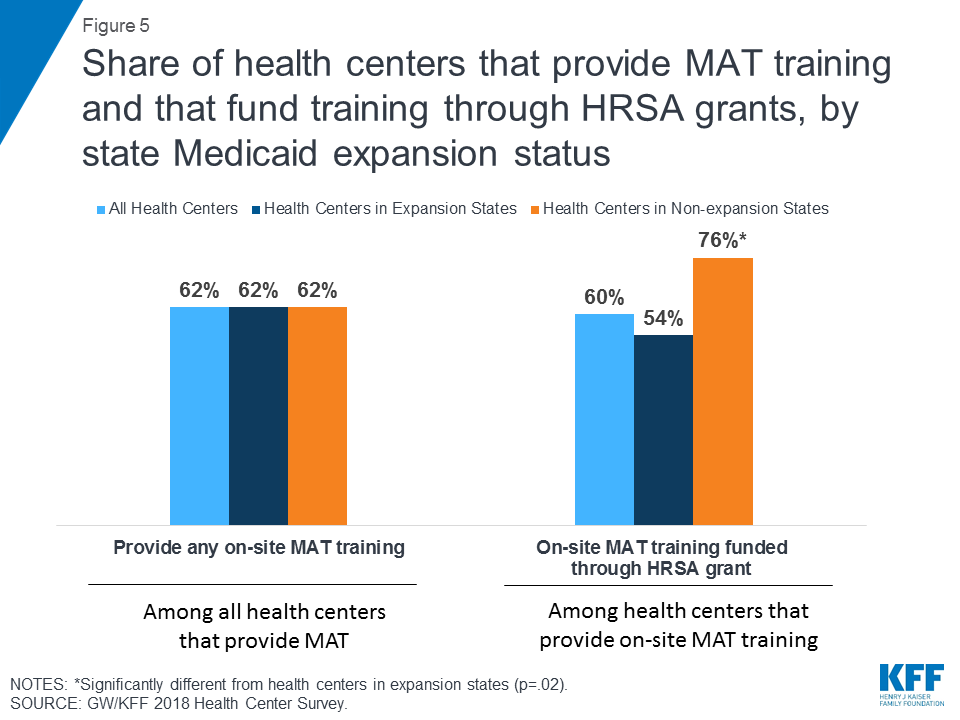

Health centers that provide MAT in expansion states and non-expansion states are equally likely to provide training to providers, but those in non-expansion states may be more dependent on federal funds to finance these trainings. Provider training is an integral part of effective MAT, and just over six in ten (62%) health centers provide on-site training to providers on prescribing medications as part of MAT (Figure 5). However, financing the on-site training can be challenging, particularly for smaller health centers that have more limited capacity. Of the health centers that provide on-site training, six in ten reported funding the training with a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) grant. Health centers in non-expansion states were significantly more likely than those in expansion states to report funding their provider MAT training with a HRSA grant (76% vs. 54%) (Figure 5). This finding was particularly pronounced among health centers in hard-hit states (86% vs. 51%) (Appendix Table 1).

Treatment Capacity Challenges

Health centers face challenges in meeting the high demand for treatment among their patients with OUD. Due to staffing and other resource constraints, nearly seven in ten (69%) health centers that provide MAT services do not provide them at all sites (Figure 6). Overall, over six in ten (63%) health centers that provide MAT report not having the capacity to treat all patients who seek these services. Among health centers that attempt to refer patients to other MAT providers (including both those that provide MAT services and those that do not), 68% face provider shortages that limit access to treatment for their patients. These challenges are likely the result of system-wide treatment shortages22 and the surging prevalence of OUD.23 In 2016, fewer than three in ten (29%) adults with OUD received any treatment, and this percentage was even lower (23%) for patients who were uninsured.24

To support the expansion of SUD treatment services, including services to treat OUD, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has provided additional funding to health centers. HRSA awarded $94 million to 271 health centers in 45 states and DC in March 2016 and an additional $200 million to 1,178 health centers in all 50 states and DC in September 2017.25 ,26 These grants funded additional staff, services, and provider training. More recently, in June 2018, HRSA announced the availability of $350 million in supplemental grant funding (including $200 million in one-time grants) to enable health centers to continue to strengthen their services, using a comprehensive, team-centered approach to care.27

Opioid Overdose Reversal

Many health centers distribute naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of an overdose, and benefit from pharmacy benefit management (PBM) strategies to increase access to naloxone. Overall, four in 10 health centers reported distributing naloxone and health centers in expansion states were almost twice as likely as those in non-expansion states to do so (47% vs. 26%) (Figure 7). Among health centers in states that were hit hard by the opioid epidemic, those in expansion states were also significantly more likely to distribute naloxone (51% vs. 32%) (Appendix Table 1). With dramatic increases in opioid overdose deaths in recent years, naloxone has become a critical tool in minimizing fatalities due to the opioid epidemic.28 Most state Medicaid programs have PBM strategies in place to increase access to naloxone for enrollees, such as making some formulations of naloxone available without prior authorization or allowing family or friends to obtain naloxone prescriptions on a Medicaid enrollee’s behalf. Medicaid programs in expansion states are more likely than those in non-expansion states to cover the atomizer for the nasal spray (53% vs. 16%) and the auto-injector (28% vs. 5%) without prior authorization (Table 1).29 They are also more than twice as likely (25% vs. 11%) to cover naloxone for family or friends of an enrollee.30

| Table 1: Medicaid Coverage of Naloxone, by Medicaid Expansion Status | |||

| Overall | Expansion State | Non-expansion State | |

| State Medicaid program covers atomizer without prior authorization | 38% | 53% | 16%* |

| State Medicaid program covers auto-injector without prior authorization | 19% | 28% | 5%* |

| State Medicaid program covers naloxone for friends/family of enrollee | 21% | 25% | 11% |

| *Significantly different from expansion states at p<.05. Source: 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey. | |||

Safer Prescribing Practices

Most health centers have made efforts to make prescribing practices safer. Nearly nine in ten (87%) health centers reported having written policies and procedures regarding the use of prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMP) before writing prescriptions for opioids. PDMPs are electronic databases that enable providers to track controlled substance prescriptions for patients in their state in order to prevent overprescribing to an individual patient.31 Because of their complex health needs, many Medicaid enrollees and other health center patients may be more likely than the general population to need prescription opioids to treat pain. The large share of health centers with policies and procedures regarding the use of PDMPs helps to maximize the likelihood that patients are receiving prescription opioids only when medically necessarily.

Looking Ahead

As the primary source of health care for many low-income Americans, health centers play a critical role in addressing the opioid epidemic, through prevention, treatment, overdose reversal, and safe prescribing practices. The majority of health centers reported an increase in the share of patients with an OUD, and nearly half provide on-site MAT. Many health centers also distribute naloxone for opioid overdose reversal and prioritize the use of PDMPs. Because of enhanced federal funding from Medicaid expansion, as well as the broad coverage of treatment services through Medicaid, health centers in expansion states appear to be better equipped to address the opioid epidemic. Compared to health centers in non-expansion states, those in expansion states are more likely to provide on-site MAT, and to distribute naloxone.

As the opioid epidemic continues to escalate, health centers will face ongoing challenges in meeting the demand for OUD treatment. Grant funding plays an important but somewhat limited role in this regard. One-time grants can bolster existing services and support service expansions, but the funding per health center grantee is often modest. Health centers rely heavily on Medicaid as an ongoing revenue source in order to continue to meet patients’ needs. Given Medicaid’s role in supporting efforts to expand access to treatment and overdose prevention, decisions by more states to expand Medicaid coverage could increase health centers’ capacity to address the epidemic and to provide long-term recovery support to patients.

Because Medicaid is so important to health centers’ ability to build sustainable treatment and recovery programs, states’ efforts to use Section 1115 waivers to impose work or community engagement, premium, and drug testing requirements for Medicaid enrollees bear close watching. Such demonstrations could create barriers to Medicaid coverage for health center patients with OUD. Even in the case of demonstrations that exempt people receiving SUD treatment, states have not yet defined the concept of active treatment, which could exclude important long-term recovery care. Health centers rely heavily on Medicaid revenue and if patients lose their Medicaid coverage, health centers could be limited in their ability to respond to the epidemic. Additionally, work, premium, and drug testing requirements would create administrative burdens for health centers as they help their patients navigate these requirements, which could interfere with their capacity to provide comprehensive care.

| Methods The 2018 Survey of Community Health Centers’ Experiences and Activities under the Affordable Care Act was conducted by researchers at the Geiger Gibson Program in Community Health Policy at the George Washington University (GW) and the Kaiser Family Foundation Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured, with support and input from the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC) and the RCHN Community Health Foundation. This brief used data from the questions about how health centers are approaching the opioid crisis and the treatment options that are available. The online survey was emailed to all CEOs of federally funded community health centers in the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) identified in the 2016 Uniform Data System (UDS) (n=1,337), to which all health centers must report annually. The survey was fielded from early January to late February 2018. There were a total of 489 survey responses from 49 states and DC, resulting in a response rate of 37%. Bivariate analyses (chi-squared tests) were conducted to test for significant differences by health centers’ location in Medicaid expansion or non-expansion states. Findings are presented for all respondents and by location in states that expanded Medicaid and non-expansion states. For findings with statistically significant differences between expansion and non-expansion states, additional analyses were conducted for a smaller subset of health centers located in states with above-average opioid overdose death rates. Again, chi-squared tests were conducted to test for significant differences by health centers’ location in Medicaid expansion or non-expansion states. |

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: Differences between Health Centers in Medicaid Expansion and Non-expansion States in States With Above-Average Opioid Overdose Death Rates | |||

| Health Centers in Hard-hit States | Health Centers in Hard-hit Expansion States | Health Centers in Hard-hit Non-expansion States | |

| Increase in opioid use disorder in past three years | 81% | 83% | 75% |

| Provide on-site medication-assisted treatment | 56% | 63% | 40%* |

| Provide injectable naltrexone | 71% | 78% | 45%* |

| Distribute naloxone | 45% | 51% | 32%* |

| Fund MAT training with HRSA grant | 60% | 51% | 86%* |

| *Significantly different from health centers in hard-hit expansion states at p<.05. Source: GW/KFF 2018 Health Center Survey | |||

Endnotes

- Seth, P., Scholl, L., Rudd, R. A., & Bacon, S. (2018). Overdose Deaths Involving Opioids, Cocaine, and Psychostimulants-United States, 2015-2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(12), 349-358. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6712a1.htm?s_cid=mm6712a1_w#T1_down ↩︎

- Rosenbaum, S., Tolbert, J., Sharac, J., Shin, P., Gunsalus, R. & Zur, J. (2018). Community Health Centers: Growing Importance in a Changing Health Care System. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-a-changing-health-care-system/ ↩︎

- Julia Zur and Jennifer Tolbert, “The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed June 2018, https:/”modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-bief/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-facilitating-access-to-treatment/. ↩︎

- “The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Treatment: A Look at Changes Over Time,” Kaiser Family Foundation,” accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/slideshow/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-treatment-a-look-at-changes-over-time/ ↩︎

- “Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision,” accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration, “Uniform Data System: Reporting Instructions for 2016 Health Center Data,” (p. 54), accessed June 2018, https://www.bphc.hrsa.gov/datareporting/reporting/2016udsreportingmanual.pdf. ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration, “2010 Health center data: National data,” accessed June 2018, https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/view.aspx?q=tall&year=2010&state; Health Resources and Services Administration, “2016 health center data: National data,” accessed June 2018, https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/view.aspx?q=tall&year=2016&state=. ↩︎

- “Medical providers treating patients with substance use diagnoses remain reported on Lines 1 through 10 (p. 54).” “Because substance abuse is also seen as a mental health diagnosis, it is permissible to count the visit under mental health (p. 63).” Health Resources and Services Administration, “Uniform Data System: Reporting Instructions for 2016 Health Center Data,” accessed June 2018, https://www.bphc.hrsa.gov/datareporting/reporting/2016udsreportingmanual.pdf. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)” https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment (accessed June 4, 2018). ↩︎

- Rosenbaum, S., Tolbert, J., Sharac, J., Shin, P., Gunsalus, R. & Zur, J. (2018). Community Health Centers: Growing Importance in a Changing Health Care System. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-a-changing-health-care-system/ ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT)” https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment (accessed June 4, 2018). ↩︎

- Colleen M. Grogan, et al., “Survey Highlights Differences in Medicaid Coverage for Substance Use Treatment and Opioid Use Disorder Medications,” Health Affairs 35, no. 12 (Dec. 2016):2289-2296, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/12/2289.full ↩︎

- Kathleen Gifford et al., Medicaid Moving Ahead in Uncertain Times: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-moving-ahead-in-uncertain-times-results-from-a-50-state-medicaid-budget-survey-for-state-fiscal-years-2017-and-2018/. ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Office of Management and Budget, “Efficient, Effective, Accountable: An American Budget,” accessed June 2018, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/budget-fy2019.pdf. ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Buprenorphine Waiver Management,” https://www.samhsa.gov/programs-campaigns/medication-assisted-treatment/training-materials-resources/buprenorphine-waiver (accessed June 4, 2018). ↩︎

- Health Resources and Services Administration, “Electronic Health Record Capabilities and Quality Recognition: National data,” accessed June 2018, https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=tehr&year=2016&state=&fd=. ↩︎

- U.S. Congress, Senate, Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, S.524, 114th Congress, https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ198/PLAW-114publ198.pdf. ↩︎

- Heide Jackson et al., “Cost Effectiveness of Injectable Extended Release Naltrexone Compared to Methadone Maintenance and Buprenorphine Maintenance Treatment for Opioid Dependence,” Substance Abuse 36, no. 2 (2015):226-231, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4470733/ ↩︎

- Rosenbaum, S., Tolbert, J., Sharac, J., Shin, P., Gunsalus, R. & Zur, J. (2018). Community Health Centers: Growing Importance in a Changing Health Care System. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-a-changing-health-care-system/ ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, An Introduction to Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone for the Treatment of People with Opioid Dependence (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012), https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/Intro_To_Injectable_Naltrexone.pdf ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Report to Congress on the Nation’s Substance Abuse and Mental Health Workforce Issues (Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, January 2013), https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/PEP13-RTC-BHWORK/PEP13-RTC-BHWORK.pdf. ↩︎

- “The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Treatment: A Look at Changes Over Time,” Kaiser Family Foundation,” accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/slideshow/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-treatment-a-look-at-changes-over-time/ ↩︎

- Julia Zur and Jennifer Tolbert, “The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid’s Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-bief/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-facilitating-access-to-treatment/. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “HHS awards $94 million to health centers to help treat the prescription opioid abuse and heroin epidemic in America,” accessed June 5, 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/blog/2016/03/17/hhs-awards-94-million-to-health-centers-to-help-treat-the-prescription-opioid-abuse-and-heroin-epidemic-in-america.html ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “HRSA awards $200 million to health centers nationwide to tackle mental health and fight the opioid overdose crisis,” accessed June 5, 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/09/14/hrsa-awards-200-million-to-health-centers-nationwide.html ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “FY 2018 expanding access to quality substance use disorder and mental health services (SUD-MH) supplemental funding technical assistance (HRSA-18-118),” accessed July 10, 2018, https://bphc.hrsa.gov/programopportunities/fundingopportunities/sud-mh/index.html ↩︎

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Naloxone” https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/naloxone (accessed June 4, 2018). ↩︎

- “States Reporting Medicaid FFS Pharmacy Benefit Management Strategies for Naloxone in Place,” Kaiser Family Foundation, accessed June 2018, https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/states-reporting-medicaid-ffs-pharmacy-benefit-management-strategies-for-naloxone-in-place ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “What States Need to Know about PDMPs,” https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html (accessed June 4, 2018). ↩︎