An Overview of Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Grants

Executive Summary

Given the high prevalence of chronic diseases and conditions in the United States, and the role that health risk behaviors play in contributing to chronic disease, policymakers have increasingly focused on the benefits of investing in preventive care and engaging Americans in their health behaviors. Several state Medicaid programs have implemented incentives for beneficiaries who demonstrate healthy choices, which are meant to empower individuals to change their lifestyle habits to achieve better health.

To promote and expand these incentives, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) program.1 This program provides $85 million to ten states over five years to test the effectiveness of providing incentives directly to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and change their health risks and outcomes by adopting healthy behaviors (Appendix). States must address either tobacco cessation, controlling weight, lowering cholesterol, lowering blood pressure, preventing or controlling diabetes, or a combination of these goals. In November 2013, an interim evaluation was conducted on MIPCD programs to date.2 This brief highlights key findings from the evaluation and puts them in context of past and proposed beneficiary incentive programs in Medicaid. A final evaluation of the MIPCD programs will be completed by July 2016.

States are taking various approaches to implementing MIPCD programs. Most states are targeting more than one health behavior or condition, offering money or money-equivalent (e.g. gift cards) as incentives, focusing on special populations (e.g. pregnant women or individuals with mental illness), and using randomized control trials to evaluate the programs. However, each initiative is designed differently and the range of interventions varies widely. States are using telephone helplines, counseling, educational and training programs, weight management classes, health coaches, and wellness plans combined with flexible spending accounts. Some states are offering incentives to providers to participate in the program as well. However, states faced challenges in implementing incentive programs, which led to delayed implementation in most states. As a result, data on program effectiveness is currently limited, but is expected to grow as programs expand.

In addition to the MIPCD program, other states are interested in including healthy behavior incentives in their Medicaid programs, for example, by incorporating the incentives into proposed or approved Section 1115 Medicaid expansion waivers. In general, however, pre-ACA beneficiary incentive programs and MIPCD programs tend to offer additional rewards that go beyond traditional Medicaid parameters, while states that are incorporating healthy behavior incentives into Medicaid expansion waivers are tying healthy behaviors to reduced or waived premiums and cost-sharing that are otherwise required. As states move forward, it is important to note that low-income individuals may face unique challenges that could limit their ability to participate in these programs or meet requirements to earn incentives. More evidence will be needed on the effect of beneficiary incentives in Medicaid on health care access and utilization, health outcomes, and costs.

Issue Brief: Mipcd Grants

Introduction

Faced with rising health care costs and disparities in health outcomes, policymakers have increasingly focused on the benefits of investing in preventive care. In particular, states are expanding efforts to engage Americans in their behaviors and emphasize the importance of personal choices in determining health. Several Medicaid programs have implemented incentives for beneficiaries who demonstrate healthy behaviors. Incentive programs often focus on preventative care and disease management, and some target specific behaviors such as smoking and weight loss. Programs vary by the authority under which they operate and the incentives used, such as cash, gift cards, or flexible spending accounts. To expand these programs, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) grant. This grant allows states to provide incentives to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and demonstrate changes in health risk and outcomes. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation awarded MIPCD grants to ten states in September 2011 and the program runs through January 1, 2016 (see Appendix for more details on state programs). In November 2013, an interim evaluation was conducted on MIPCD programs to date. This brief highlights key findings from the evaluation and puts them in context of past and proposed beneficiary incentive programs in Medicaid.

Background

Chronic Disease and Preventive Care in the United States

Chronic diseases and conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, are among the most common, costly, and preventable of all health problems.3 As of 2012, about half of all U.S. adults (117 million people) had one or more chronic health conditions, and one in four adults had two or more chronic health conditions.4 Health risk behaviors are unhealthy behaviors that can be changed, and four of these risk behaviors (lack of exercise or physical activity, poor nutrition, tobacco use, and overconsumption of alcohol) cause much of the illness, suffering, and early death related to chronic diseases and conditions.5

Individuals in the U.S., particularly low-income populations, face barriers to receiving the recommended amount of health care. American adults receive only half of recommended health care, including preventive care, acute care, and treatment for chronic conditions.6 Low-income populations and racial and ethnic minorities in particular face inequalities in access to and quality of services, preventive care, health outcomes, and risk of unhealthy behaviors.7 Low socioeconomic status, in part due to health care access, cost, and infrastructure barriers, has been associated with higher risks of smoking, obesity, and certain chronic conditions.8

Medicaid Beneficiary Incentive Programs Prior to the ACA

Prior to the ACA, several Medicaid programs implemented beneficiary incentive programs to engage Americans in their behaviors and emphasize the importance of personal choices in determining health.9 These programs were meant to empower individuals to change their lifestyle habits to achieve better health and often focused on preventative care, prenatal and postpartum care, smoking, obesity, and specific chronic conditions. Some of these programs, such as Idaho’s Preventative Health Assistance (PHA) Benefits10 and Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP), are still operating. Pre-ACA Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs have achieved mixed results, and some have faced criticisms or skepticism from the health policy community and patient advocates.11

Medicaid healthy behavior incentives are often offered in the form of cash reward, pre-paid debit card, or gift certificate for use towards health-related purchases, such as medicine, healthy food, or gym memberships. Some states, such as Idaho, offer beneficiaries points or credits, which may be accumulated to redeem similar rewards.12 For children in families that pay a Medicaid premium, Idaho also offers reduced premiums for keeping well-child check-ups and immunizations current. West Virginia offered enhanced or restricted benefits to promote healthy behaviors through its Mountain Health Choices program, which ended on January 1, 2014.13 Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) currently offers health savings accounts (HSAs) to pre-ACA Medicaid expansion adults. Both the state and the beneficiary contribute to this account. If beneficiaries complete all age and gender appropriate preventive services, all remaining account funds (both state and individual) are rolled over to the next year. However, if preventive services are not completed, only the individual’s prorated contribution (not the state’s) rolls over.14

Medicaid programs operate beneficiary incentive programs under various authorities. To date, most states have used Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers that include beneficiary incentives for healthy behaviors to operate their programs.15 Some states have used Section 1915(b) waivers and Medicaid managed care organizations to offer incentives.16 Other states have operated incentive programs as state plan amendments under the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA)17 or as pilot or demonstration programs.18

Some pre-ACA Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs, such as Florida’s Enhanced Benefits Reward$ and West Virginia’s Mountain Health Choices, have ended or are phasing out. Florida is currently transitioning most of its Medicaid beneficiaries into managed care through the renewal of its “Managed Medical Assistance” (MMA) Section 1115 waiver. The renewed waiver calls for the Enhanced Benefits Reward$ program to phase out, but will require managed care plans operating in MMA program counties to administer programs to encourage and reward healthy behaviors.19 West Virginia’s Mountain Health Choices required beneficiaries to sign a membership agreement promising to adhere to certain behaviors (such as keeping doctor appointments and complying with medication) and a health improvement plan. If beneficiaries complied with these agreements, they received an enhanced benefit plan, but if they did not comply with the agreements, they received a benefit plan covering fewer services than the traditional Medicaid plan.20 In 2010, federal regulations required adult enrollments into such programs to be voluntary, which resulted in the state discontinuing the program on January 1, 2014.21

Evidence on Consumer Incentive Programs

Overall (both inside and outside of Medicaid), consumer incentive programs are fairly new and research on their effectiveness in encouraging behavior change has varied. In the short run, consumer incentives can be effective for encouraging one-time or simple preventative care, such as receiving immunizations or attending a regular check-up. However, there is insufficient evidence to say if incentives are effective for promoting long-term lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation or weight management.22 Additionally, studies of consumer incentives often have limitations such as small sample sizes and limited follow-up.23 Evidence on Medicaid incentive programs specifically has varied as well. Some Medicaid programs have received positive participant feedback and have shown high rates of physician visits and preventative care, while other programs have found little evidence of beneficiary behavior change or health improvement. Many Medicaid programs have faced skepticism that incentives will encourage healthy behavior changes.24

Estimates on the cost-effectiveness of Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs have also varied. States aim to reduce Medicaid costs by encouraging the use of preventative care in order to decrease the need for future high-cost treatments and hospital use. However, government agencies, policy analysts, and patient advocates have questioned the cost-effectiveness of incentive programs given their infrastructure start-up costs, marketing costs, and administrative costs.25

Some private incentive programs offered through drug treatment programs or workplace settings have demonstrated success in improving health behaviors,26 but Medicaid programs could encounter unique challenges in implementing such incentives. Low-income individuals face obstacles that could limit their participation or hinder their ability to meet the requirements necessary to achieve incentives. For example, Medicaid beneficiaries may have difficulty affording transportation or child care to attend doctor appointments, have insufficient access to phones or computers to complete required activities, or have difficulty affording health activities or medications that may not be covered by Medicaid, but which would help them to achieve their goals, such as weight loss programs or educational classes. Additionally, private programs are likely to offer greater financial incentives, which could influence more substantial behavior change.

Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) Grants

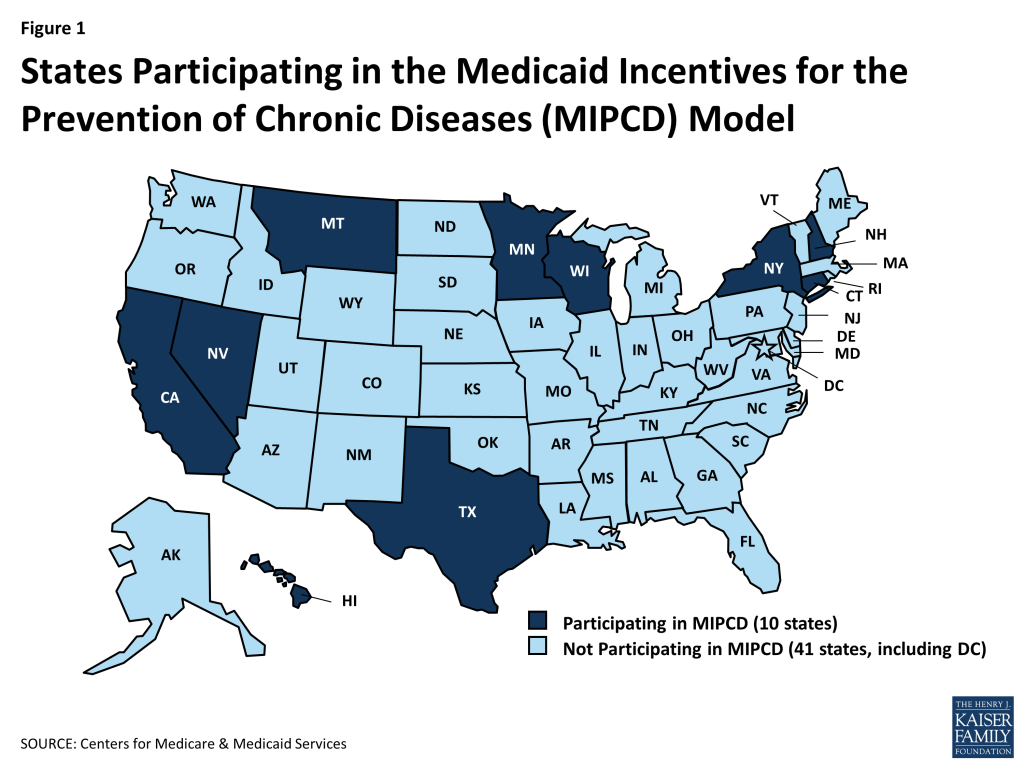

Section 4108 of the Affordable Care Act created the Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) program. The grant program provides a total of $85 million over five years to ten states to test the effectiveness of providing incentives directly to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in prevention programs and change their health risks and outcomes by adopting healthy behaviors.27 States must address at least one of the designated prevention goals: tobacco cessation, controlling or reducing weight, lowering cholesterol, lowering blood pressure, and preventing or controlling diabetes. In September 2011, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation awarded ten states demonstration grants: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, Texas, and Wisconsin (Figure 1). States are in the process of implementing their incentive programs and grant funding runs through January 1, 2016. An interim evaluation was conducted in November 2013, and a final evaluation will be completed by July 2016.

States are required to target at least one of the five designated prevention goals described above, however, six of the ten grantee states (Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, and Texas) are targeting multiple behaviors and conditions (Table 1). Montana and Nevada are each targeting four prevention goals, and Texas is targeting all five prevention goals. Some of these programs link their focuses on healthy behaviors to improved conditions. For example, Montana will monitor weight loss, lowered cholesterol, and lowered blood pressure in an effort to prevent type 2 diabetes. Other states have separate, distinct programs that focus on different goals. New Hampshire, for example, has a weight management program and a separate smoking cessation program. The goals most commonly targeted are smoking and diabetes (six states each), and the least frequently targeted goal is high cholesterol (three states). To implement their MIPCD grants, Medicaid programs are partnering with other government agencies and private organizations to more effectively address a range of health conditions and behaviors. Partners often include state departments of public health or mental health/substance abuse, universities, research institutes, community organizations, providers, and health plans.28

| Table 1: Medical Conditions and Health Behaviors Addressed by State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |||||

| State | Smoking | Diabetes | Obesity | High Cholesterol | High Blood Pressure |

| California | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | ||||

| Hawaii | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | X | |||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | |

| Nevada | X | X | X | X | |

| New Hampshire | X | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | ||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X |

| Wisconsin | X | ||||

| Total | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |||||

States are taking various approaches in their behavior-change interventions. Most programs focused on smoking cessation involve telephone helplines, in-person or telephone-based counseling, and nicotine replacement therapy or other medications. Connecticut is also using peer coaches, and New Hampshire is using a web-based decision support system in addition to the other services mentioned. Programs focused on diabetes tend to use educational and training programs focused on diabetes prevention or self-management. Some states are also using care coordination, health coaches, or incentives for attending primary care visits or filling prescriptions. Weight management programs most often provide gym memberships or access to weight loss or health promotion programs. Texas is having its beneficiaries create a personal wellness plan, receive a flexible spending account, and work with a health navigator to achieve personal health goals. Some states are training providers on specific treatment programs or incentivizing providers for participating in the MIPCD program.29

All MIPCD states are targeting adult Medicaid beneficiaries with or at risk of chronic diseases;30 however, many states are focusing on additional special populations with unique health care needs (Table 2). Five states are focusing on pregnant women and mothers of newborns, most of them with a focus on smoking cessation. Four states are focusing on individuals with mental illness, and two of these states are also addressing individuals with substance abuse disorders. Three states are focusing on racial/ethnic minorities and one state (Nevada) is focusing on children. Eight states are incorporating individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (“dual-eligibles”) into their programs. States also vary in the number of beneficiaries that they expect to reach. Connecticut hopes to enroll the most beneficiaries (28,771) in its program, while Montana is focusing on the smallest number of beneficiaries (726).31

| Table 2: Targeted Special Populations in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | ||||||

| State | Individuals with Mental Illness | Individuals with Substance Abuse Disorders | Racial/Ethnic Minorities | Pregnant Women and Mothers of Newborns | Children | Dual-Eligible Beneficiaries |

| Californiaa | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Connecticutb | X | X | X | |||

| Hawaiic | X | X | ||||

| Minnesotad | X | |||||

| Montanae | X | X | ||||

| Nevada | X | X | ||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | ||||

| New Yorkf | X | |||||

| Texasg | X | X | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | |||

| Total | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 8 |

| NOTES: a CA does not consider these populations to be a primary focus, but will be able to identify these populations and provide data on their participation;b For individuals with mental illness, CT is focusing on serious mental illness;c HI does not consider individuals with mental illness or substance abuse disorders to be a primary focus, but will be able to identify these populations and provide data on their participation. For racial/ethnic minorities, HI is focusing primarily on indigenous Native Hawaiians, immigrant Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and migrants from Compact of Freely Associated States;d MN does not consider racial/ethnic minorities to be a primary focus, but will examine the differences among racial and ethnic minorities to the extent that the data will support that level of analysis. MN will focus specifically on American Indian, African American, Somali, Latino, Hmong, Vietnamese, Korean, and other Asian immigrants;e In MT, pregnant women are ineligible for the program, but mothers of newborns who meet the eligibility criteria are eligible for the program;f NY does not consider mothers of newborns to be a primary focus, but this population may be included in its programs;g TX will focus both on serious and persistent mental illness (ex. schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder) and other behavioral health conditions (ex. anxiety disorder or substance abuse).SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | ||||||

Most states are including beneficiaries statewide, but some are focusing on targeted geographic areas (Table 3). For example, Texas, Minnesota, and Nevada are all focusing their programs in major metropolitan areas (Houston, Minneapolis-St. Paul, and Las Vegas). California and Wisconsin started their programs as a pilot in one county before rolling them out statewide. Hawaii phasing in its program by participating FQHC, and New York is phasing in its program by MCO and program focus, before both states roll their programs out statewide. Connecticut, Montana, and New Hampshire are all implementing their programs statewide with no phase-in process.32

| Table 3: Targeted Locations of State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |

| State | Location |

| California | Began implementation as a pilot in one county and rolled out statewide |

| Connecticut | Statewide (no pilot or phases)a |

| Hawaii | Phased-in implementation by FQHC, rolling out to 14 FQHCs and the larger private providers throughout the six main inhabited islands of Hawaii |

| Minnesota | Phased-in implementation by clinic, rolling out to the 7-county Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area |

| Montana | 14 health facilities across the state (no pilot or phases) |

| Nevada | Phased-in implementation by partner organization, rolling out to the Las Vegas area |

| New Hampshire | 10 community mental health centers across the state (no pilot or phases) |

| New York | Phased-in implementation by MCO and program focus, rolling out statewideb |

| Texas | 9 counties in the Houston area (no pilot or phases) |

| Wisconsin | Beginning implementation as a pilot in one county and rolling out statewide.c |

| a The peer coaching component of the initiative will be available only to participants in three selected counties.b New York is collaborating with Medicaid managed care organizations, which may operate statewide, or may be located in select geographic areas.c Wisconsin’s First Breath arm of its MIPCD program will be in Kenosha, Milwaukee, Racine, Dane, and Rock counties and will expand to additional counties, with the initial focus on those with high numbers of pregnant BadgerCare Plus members. Wisconsin’s Tobacco Quit Line arm of its MIPCD program will be implemented in Brown, Dane, Dodge/Jefferson (clinic is on border of two counties), Green, Milwaukee, Rock, and Winnebago counties where the biochemical nicotine test is currently available. Expansion to additional counties will take place in the future. SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |

States are building on traditional Medicaid incentive structures, but offering a range of options to beneficiaries. Most states are using money, or money-equivalents (such as gift cards), in their programs. Programs also offer incentives related to treatment (such as nicotine patches) or incentives related to prevention (such as gym memberships or participation in Weight Watchers). Nevada is offering points redeemable for rewards through a web-based platform, while Texas is offering its participants access to a flexible spending account. Some states are also offering participants supports to address barriers to participation. Minnesota, for example, which has its beneficiaries attend Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) self-management training sessions, offers meals and child care during training sessions, as well as transportation to the sessions. In Hawaii, participating FQHCs have flexibility to determine the form of the participant’s incentive (gift certificate, fee for gym membership, etc.).33

The maximum value of incentives varies widely by state, and may help to demonstrate if the value of incentives impacts behavior change. Because states are designing different incentive structures, the maximum value of incentives varies by state. Incentives range from $20 in California for calling a smoking cessation helpline and participating in counseling sessions, to $1,860 per year in New Hampshire for participating in a weight loss program. Eight out of the ten states offer incentives that range between $215-$600 per year. States are rewarding both participation in prevention- and treatment-related activities as well as health outcomes. All states are rewarding beneficiaries for participation or behavior change (such as attending smoking cessation or diabetes self-management programs), and seven states are also offering incentives for improved health outcomes (such as weight loss, achievement of smoking cessation or a negative CO breathalyzer test, or improved blood tests). Connecticut is offering additional incentives for repeated participation or repeated improved health outcomes. Six states are offering rewards to providers to incentivize their participation in the MIPCD program as well (Table 4). Incentives for providers include $35/individual for enrolling participants in Connecticut, $308/individual for providing services to participants in Hawaii, up to $278,000 for clinics to cover study-related costs in Minnesota, and Medicaid reimbursement for providing lifestyle interventions in Montana.34

| Table 4: Provider Incentives in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |

| State | Provider Incentives |

| California | NA |

| Connecticut | -Free online training offered for providers on smoking cessation treatment and information on Medicaid coverage for smoking cessation services and Rewards to Quit program services.-One time $35 stipend offered to providers for each new Medicaid recipient enrolled in Rewards to Quit. |

| Hawaii | Participating FQHCs and private providers may receive up to $308 per participant for providing supportive, supplemental services to patients. |

| Minnesota | Clinics receive up to $278,000 to cover study-related costs, including participants’ supports, personnel, equipment, and supplies. |

| Montana | Through an approved state plan amendment, selected licensed health care professionals can be reimbursed by Medicaid for providing the lifestyle intervention. |

| Nevada | Select providers may receive compensation for each participant for which they enter enrollment and incentive data into a web portal. Compensation is $300 per participant for YMCA, $250 per participant for Children’s Heart Center, and $275 per participant for Lied Clinic. |

| New Hampshire | NA |

| New York | NA |

| Texas | NA |

| Wisconsin | Clinics and public testing sites receive $1,000 after receiving training and conducting testing. They may also select a “per member” option, which may provide additional support of $50-75 per member. |

| SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |

States are required to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs, and seven out of ten states are structuring their programs as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard of research design (Table 5).35 Of the states not conducting RCTs, Hawaii is conducting a quasi-experimental design that lacks random assignment. Montana is using a crossover design, where, during the first 18 months of the program, seven of its 14 intervention sites will be selected to provide participants with incentives and the remaining sites will not. After that, the seven sites that did not offer incentives will provide them to new participants, and the sites that did provide incentives will no longer provide them to new participants. New Hampshire is using an equipoise-stratified randomized design, where participants select their treatment options, and then half of participants are randomized as to whether they receive incentives. Eights states are also conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis of the incentive programs. States are at different phases in their evaluations due to starting at different times. Montana, California, New Hampshire, and Texas began implementation between January-May 2012, whereas some states did not begin implementation until February-September 2013.36 States are required to submit quarterly, semi-annual (every six months), annual, and final (at the end of the grant period) reports. In addition to these state evaluations, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must procure an independent contractor to conduct a national evaluation, and submit interim and final reports of this evaluation to Congress.37

| Table 5: Evaluation Designs in State MIPCD Programs, 2013 | |||||

| State | Quasi-Experimental Designs | Randomized Controlled Trialsa | Equipoise-Stratified Randomized Designs | Crossover Designsb | Cost-Effectiveness Analysesc |

| California | X | X | X | ||

| Connecticut | X | X | |||

| Hawaii | X | X | |||

| Minnesota | X | X | |||

| Montana | X | ||||

| Nevada | X | X | |||

| New Hampshire | X | X | |||

| New York | X | ||||

| Texas | X | X | |||

| Wisconsin | X | X | |||

| Total | 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| a Wisconsin has changed its initiative from a clinical trial to a quality-improvement project; however, it is maintaining its randomized two-group design.b Hawaii is considering adopting a crossover design for use with a participating private group practice.c New York will conduct an informal cost-effectiveness study; a formal assessment of all the costs will not be undertaken.SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. | |||||

Issue Brief: Status Of Mipcd Programs To Date

The interim national evaluation of MIPCD programs, submitted by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to Congress in November 2013, provided an overview of the status of MIPCD programs and enrollment to date. States faced unforeseen challenges in the implementation process, which led to the delayed implementation of most programs. As a result, most states had been enrolling participants only for a short period of time before the interim evaluation and were below their beneficiary enrollment targets. As of August 31, 2013, Texas was the only state that had met its enrollment target of 1,250 beneficiaries. Due to the lack of evidence available at the time of the interim evaluation, no recommendation was made for or against extending the programs beyond January 2016.38

Certain challenges were common among states implementing MIPCD programs. These challenges included:

- Administrative delays and working through state bureaucracies (e.g. contracting limitations, releasing Requests for Proposals and securing contracts, creating and submitting materials to multiple institutional review boards, and trying to hire staff)

- Provider engagement and participation, for reasons such as administrative burdens associated with program oversight and data collection, agreeing to program requirements, incorporating the program into providers’ daily workflows, lack of funding to encourage provider participation, and the inclusion of some services (such as YMCA diabetes prevention classes) in the program that are not covered by Medicaid

- Provider management and oversight (especially in large states with a high number of providers participating in Medicaid, or where providers may be geographically dispersed over large distances)

- Participant identification (e.g. identifying eligible participants for the program due to lack of target population data or being uncertain whether individuals who meet the program criteria are eligible for or enrolled in Medicaid)

- Managing patient incentives (e.g. technical barriers and difficulty with vendor procurement for offering cash in the form of debit cards)

- Community perceptions of participants (particularly perceptions of participants with mental health conditions when attending community events such as Weight Watchers meetings or YMCA classes).

As a result of these challenges, states have adapted many elements of their MIPCD programs, including:

- Timelines (most states delayed implementation dates and some states modified the implementation of programs, scaling them down or staggering their roll-out)

- Beneficiary recruitment and enrollment (e.g. adopting new recruiting tools, reducing enrollment targets, changing the screening and enrollment process, expanding the target population)

- Beneficiary incentives (e.g. changes to the incentive size, type, or distribution to maximize their effectiveness)

- Provider recruitment, training, and incentives (e.g. adjusting provider training and reimbursement, or the type of provider recruited, in an effort to recruit more providers)

- Evaluation design (e.g. amending the evaluation design or selecting a new design)

The challenges faced, and changes made to MIPCD programs, have led states to learn a variety of lessons to date. Common lessons learned include:

- Flexibility: Have the ability to adapt to challenges as they arise.

- Problem-solving: Anticipate potential issues and develop alternative plans and options when things to not go as planned.

- Political support: Have high-level champions in state government to help minimize bureaucratic obstacles and establish stakeholder relations.

- Project oversight: Adequately plan program implementation, hire a capable program manager, and implement comprehensive project management systems and infrastructure.

- Collaborative partnerships: Develop partnerships during the planning phase and nurture those relationships (e.g. with local mental health authorities, care coordinators, advocacy groups, Department of Social and Health Services board members).

- Ongoing communication: Communicate frequently and in-person to build relationships with partners and providers.

- Trained providers: Determine whether there is a sufficient number of providers with the training, capacity, and practice protocols to provide the service that the state is incentivizing.

- Cultural and linguistic awareness: Incorporate translated materials into the program and include interpreters and bilingual health coaches at the clinics/project site locations.39

The Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services will submit a final national evaluation to Congress on the MIPCD programs no later than July 1, 2016. The final report should describe the effect of the initiatives on the use of health care services by Medicaid beneficiaries, the extent to which special populations (including adults with disabilities, adults with chronic illnesses, and children with special health care needs) are able to participate in the program, the level of satisfaction of Medicaid beneficiaries with the accessibility and quality of health care services provided through the program, and the administrative costs incurred by state agencies administering the program.40

Looking Ahead

Going forward, more evidence is needed on the effect of beneficiary incentive programs in Medicaid on health care utilization, health outcomes, and costs. Once programs are further underway and more participants are enrolled, the final evaluation of the MIPCD program will likely be able to incorporate more evidence on these programs. The evaluation will also incorporate a recommendation on whether to extend federal funding of these initiatives past January 2016. The existence of, or lack of, federal funding could greatly influence whether MIPCD grantee states (as well as other states with beneficiary incentives in Medicaid) continue their incentive programs.

Beyond the MIPCD program, other states are incorporating beneficiary incentives into their Medicaid programs as part of Medicaid expansion waivers. Michigan and Iowa have approved Section 1115 demonstration waivers and Indiana and Pennsylvania have Section 1115 waivers pending approval with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for alternative Medicaid expansion plans that include healthy behavior incentives.41 Iowa and Michigan received approval, and Pennsylvania is seeking approval, to charge premiums to certain Medicaid beneficiaries, but allow premiums and copays to be reduced for beneficiaries who comply with specified healthy behaviors, such as completing physicals and/or health risk assessments. Indiana’s waiver proposal (HIP 2.0) builds on the state’s existing Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP), a pre-ACA Medicaid expansion program for adults that includes health savings accounts to which the state and individual contribute. The program offers enhanced account roll-overs to beneficiaries who complete appropriate preventive services.42 In general, pre-ACA Medicaid beneficiary incentive programs and MIPCD programs tend to offer extra rewards (such as cash, gift certificates, etc.) that go beyond the traditional Medicaid parameters. States that are incorporating healthy behavior incentives into their Medicaid expansion waivers under the ACA, however, are tying healthy behaviors to reduced or waived premiums and cost-sharing that are otherwise required. Overall, the Medicaid expansion waiver documents contain few details about the healthy behavior programs, and states are expected to develop the specific protocols for CMS approval.

Medicaid programs could encounter unique challenges in implementing healthy behavior incentives compared to private insurance programs that cover people at higher incomes. Low-income individuals face a range of economic and social barriers in their everyday lives that may make it difficult for them to participate in Medicaid incentive programs. For example, low-income populations may have difficulty affording transportation or child care to get to doctor appointments, educational classes, or weight loss programs. They may have insufficient access to phones or computers to call helplines or use web-based programs, or have difficulty affording health activities that may not be covered by Medicaid, but which would help them to achieve their health goals and earn financial incentives. Additionally, private insurance programs are likely to offer greater financial incentives, which could influence more substantial behavior change. Going forward, it will be important to monitor healthy behavior programs’ effects on Medicaid beneficiaries’ access to care, health care utilization, health outcomes, and costs, given the interest in this topic among MIPCD states and other non-MIPCD states.

Appendix

CALIFORNIA

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: March 2012

Initiative Title: Medi-Cal Incentives to Quit (MIQS) Project

First Year Grant Award: $1,541,583

Projected Number of Participants: 9,000

Description of Activities:

- Smoking cessation counseling through a Helpline

- Nicotine replacement therapy through the Helpline

- Training health care providers on the Ask, Advise, and Refer intervention and increased awareness of the incentive program

Beneficiary Incentive

- $20 gift card to pharmacies or grocery stores for calling the Helpline and participating in counseling sessions

- Free nicotine-replacement therapy (NRT) patches by calling the Helpline

- $10 gift card for every relapse-prevention call completed up to $40

- After the first program year, $10-40 to re-enroll for participants who did not quit or relapsed

CONNECTICUT

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: March 2013

Initiative Title: Connecticut Rewards to Quit

First Year Grant Award: $703,578

Projected Number of Participants: 28,771

Description of Activities:

- Counseling

- Access to a Quitline

- NRT and other medications

- Specific medications (ix. bupropion)

- Access to peer coaches

- Pregnant women have a pre- and postpartum program focused on either continued smoking cessation or relapse prevention after birth.

Beneficiary Incentive

- $5-15 for counseling visits, calls to the Quitline, and negative CO breathalyzer tests, with a maximum of $350 per 12-month enrollment period (max 2 enrollment periods/person)

HAWAII

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: February 2013

Initiative Title: Hawaii Patient Reward and Incentives for Supporting Empowerment Project (HI-PRAISE)

First Year Grant Award: $1,265,988

Projected Number of Participants: 2,500

Description of Activities:

- FQHCs test individuals at high risk for diabetes

- Diabetes education programs/self-management training

- Care coordination

- Health coaches

Beneficiary Incentive

- FQHCs can determine the form of incentive

- Tiered incentives for different activities (ex. attending diabetes management education or smoking cessation classes, achieving weight loss or improved blood test)

- Participants can receive up to $215 annually for each year the participant maintains enrollmenta

——–a FQHCs have flexibility to determine the form of the participant’s incentive (i.e. gift certificate, fee for gym membership, exercise classes, etc.).

MINNESOTA

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: November 2012

Initiative Title: Minnesota Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Diabetes

First Year Grant Award: $1,015,076

Projected Number of Participants: 1,800

Description of Activities:

- Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) self-management training

Beneficiary Incentive

- $25 debit card for attending first session

- Supports to address barriers to participation, including meals during sessions, transportation, and child care

- Participants assigned to receive either individual or individual plus group incentives

- $10-$100 for attendance and weight loss goal attainment

- $25 for follow-up clinic visit at the end of one year. • Maximum incentive amount per participant is $545

MONTANA

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: January 2012

Initiative Title: Medicaid Incentives to Prevent Chronic Disease

First Year Grant Award: $111,788

Projected Number of Participants: 726

Description of Activities:

- Adapted Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) self-management training

Beneficiary Incentive

- Tiered and incrementally increasing financial incentives for self-monitoring, reduction of fat and caloric intake, and achieving more than 150 minutes of moderately vigorous physical activity per week

- Maximum total cash incentive per participant is $315 annually

NEVADA

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: Feb-Sept 2013

Initiative Title: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases

First Year Grant Award: $415,606

Projected Number of Participants: 9,816

Description of Activities:

- Diabetes self-management education to adult beneficiaries

- YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program for those at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes

- Weight management program and support group for beneficiaries with a BMI >30

- For children at risk of heart disease, the Children’s Heart Center Nevada’s Healthy Hearts Program (nutritional counseling; exercise program; counseling and motivational coaching)

Beneficiary Incentive

- Points redeemable for rewards (through a web-based platform) on a tiered basis for participating in programs, efforts at behavior change, and achievement of improved health outcomes

- Maximum incentives for various activities range from $38-$355

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: May 2012

Initiative Title: Healthy Choices, Healthy Changes

First Year Grant Award: $1,669,800

Projected Number of Participants: 2,639

Description of Activities:

- Weight Management program (24-month period followed by a 12-month period). Participants choose between a gym membership; In SHAPE, a motivational health promotion program for persons with mental illness; Weight Watchers; or a combination of In SHAPE and Weight Watchers.

- Web-based decision support system to stimulate motivation to quit smoking. Then three options, which include combinations of prescriber referral for smoking cessation treatment, telephone-based cognitive behavioral smoking cessation therapy, and state Quit Line sessions

Beneficiary Incentive

- For both the weight management and smoking cessation programs, half of the beneficiaries will receive the program as described, and half will receive additional rewards

- Maximum incentive for the 24-month weight loss program: $3,097; 12-month weight loss program: $1,860; smoking cessation program: $415.

- $10 for completing the web-based decision support system

NEW YORK

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: June 2013

Initiative Title: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Disease Program

First Year Grant Award: $2,000,000

Projected Number of Participants: 6,800

Description of Activities:

Four programs:

- Smoking cessation

- Blood pressure control

- Diabetes management

- Diabetes onset prevention

Beneficiary Incentive

- Incentive group may be compensated for both process measures (ex. participating in counseling sessions, filling prescriptions) and outcome measures (ex. quitting smoking, losing weight, decreasing blood pressure) up to $250

- Comparison group receives $50 for participating

TEXAS

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: April 2012

Initiative Title: Wellness Incentives and Navigation (WIN) Project

First Year Grant Award: $2,753,130

Projected Number of Participants: 1,250

Description of Activities:

- Development of an individual wellness plan

- Wellness planning with a trained health navigator to help achieve personal health goals

- Flexible spending account to support specific health goals defined by the participant

Beneficiary Incentive

- $1,150/year flexible spending account for up to three yearsb

——–b TX indicated that money is not a primary form of incentive; however, participants receive monetary compensation for completing intake and yearly assessments. Participants are also able to request prevention- or treatment-related incentives associated with their health goals.

WISCONSIN

Projected/Actual Implementation Date: Sept 2012 – April 2013

Initiative Title: Striving to Quit (STQ)

First Year Grant Award: $2,298,906

Projected Number of Participants: 3,250

Description of Activities:

Two Programs:

- First Breath program: Pregnant women receive prenatal face-to-face or telephone-based smoking cessation counseling, and postpartum smoking cessation counseling for up to 12 months

- Tobacco Quit Line: Tobacco cessation services through a Quit Line

Beneficiary Incentive

- Control group participants: incentives for taking biochemical tests

- Treatment group participants: incentives for engagement in treatment and additional incentives for quitting smoking

- First Breath intervention group receives a maximum of $600 over course of pregnancy plus 12 months postpartum; control group receives $160

- Quit Line participants in the intervention group receive a maximum of $270 over six months; control group receives $80

SOURCE: Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013. http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf.

Endnotes

- For more information on MIPCD grants, see http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/MIPCD/. ↩︎

- Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, November 2013), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/MIPCD_RTC.pdf. ↩︎

- “Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed July 17, 2014, http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm?s_cid=ostltsdyk_govd_203. ↩︎

- Brian Ward, Jeannine Schiller, and Richard Goodman, “Multiple Chronic Conditions Among US Adults: A 2012 Update,” Preventing Chronic Disease 11, 130389 (April 2014), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.130389. ↩︎

- “Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ↩︎

- Elizabeth McGlynn, et al., “The Quality of Health Care Delivered to Adults in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine 348 (June 2003): 2635-2645, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa022615. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2011,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplement 60 (January 2011): 1-113, http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report (Washington, DC: AHRQ, 2010), http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhdr10/nhdr10.pdf. ↩︎

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report — United States, 2011,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplement 60 (January 2011): 1-113; Youfa Wang and May Beydoun, “The Obesity Epidemic in the United States – Gender, Age, Socioeconomic, Racial/Ethnic, and Geographic Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis,” Epidemiologic Reviews 29, no. 1 (January 20017): 6-28, http://epirev.oxfordjournals.org/content/29/1/6.full; Ali Mokdad et al., “Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000,” Journal of the American Medical Association 291, no. 10 (2004): 1238-1245, http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=198357. ↩︎

- See, for example: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., Examples of Consumer Incentives and Personal Responsibility Requirements in Medicaid (Hamilton, NJ: CHCS, May 2014), http://www.statecoverage.org/files/Consumer_Incentive_Matrix_060414.pdf. ↩︎

- “Preventive Health Assistance (PHA),” Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, accessed July 17, 2014, http://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/Medical/Medicaid/PreventiveHealthAssistance/tabid/221/Default.aspx ↩︎

- See, for example: Pat Redmond, Judith Solomon, and Mark Lin, Can Incentives for Healthy Behavior Improve Health and Hold Down Medicaid Costs? (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2007), http://www.cbpp.org/files/6-1-07health.pdf; Suzanne Felt-Lisk and Fabrice Smieliauskas, Evaluation of the Local Initiative Rewarding Results Collaborative Demonstrations: Interim Report (Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., August 2005), http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/PDFs/evaluationlocal.pdf; Joan Alker and Jack Hoadley, The Enhanced Benefits Rewards Program: Is it Changing the Way Medicaid Beneficiaries Approach their Health? (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, July 2008), https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/bahpaz41w5lkxxeey4p9; John Barth and Jessica Greene, Encouraging Healthy Behaviors in Medicaid: Early Lessons from Florida and Idaho (Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., July 2007), http://www.chcs.org/media/Encouraging_Healthy_Behaviors_in_Medicaid.pdf; Jessica Greene, Medicaid Efforts to Incentivize Healthy Behaviors (Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc., July 2007), http://www.chcs.org/media/Medicaid_Efforts_to_Incentivize_Healthy_Behaviors.pdf; Aimee Miles, “Medicaid to Offer Rewards for Healthy Behavior,” Kaiser Health News (April 11, 2011), http://www.kffhealthnews.org/Stories/2011/April/08/Medicaid-incentives.aspx; Carol Irvin, Healthy Indiana Plan: The First Two Years (Indianapolis, IN: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., July 15, 2010), http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/PDFs/health/healthyIndiana_Irvin.pdf; Hilltop Institute, Evaluation of the HealthChoice Program (Baltimore, MD: Hilltop Institute, March 2012), http://www.hilltopinstitute.org/publications/EvaluationOfTheHealthChoiceProgram-March2012.pdf; Michael Hendryx et al., Evaluation of Mountain Health Choices: Implementation, Challenges, and Recommendations (Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, August 2009), http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2009/08/evaluation-of-mountain-health-choices.html; Tami Gurley-Calvez et al., “Choice in Public Health Insurance: Evidence from West Virginia Medicaid Redesign,” Inquiry 48, no. 1 (February 2011): 15-33, http://inq.sagepub.com/content/48/1/15.full.pdf+html; January Angeles and Judith Solomon, Louisiana’s Medicaid Waiver Proposal: Is it the Right Fit for Louisiana? (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 2008), http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2218#_ftn20; Jim Saunders, “Florida Legislature Passes Massive Medicaid Overhaul,” Kaiser Health News (May 8, 2011), http://www.kffhealthnews.org/Stories/2011/May/08/Florida-Legislature-Passes-Massive-Medicaid-Overhaul.aspx; Judith Solomon, West Virginia’s Medicaid Changes Unlikely to Reduce State Costs or Improve Beneficiaries’ Health (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 2006), http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=336; Families USA, Mountain Health Choices: An Unhealthy Choice for West Virginians (Washington, DC: Families USA, August 2008). ↩︎

- “Preventive Health Assistance (PHA),” Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. ↩︎

- “Mountain Health Choices,” Mountain Health Trust, accessed August 11, 2014, http://www.mountainhealthtrust.com/mountainhealthchoices.aspx. ↩︎

- Indiana’s Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) is a pre-ACA Medicaid expansion program for uninsured adults ages 19-64 earning less than 100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($11,670 for an individual and $19,790 for a family of three in 2014). Individuals receive a $1,100 health savings account, to which the state and individual contribute. If beneficiaries complete all age and gender appropriate preventive services, all remaining account funds (both state and individual) are rolled over to the next year; however, if preventive services are not completed, only the individual’s prorated contribution (not the state’s) rolls over. Indiana has submitted a waiver to implement HIP 2.0, which builds on the original HIP program. HIP 2.0 will be an option for adults ages 19 to 64 with incomes up to 138% FPL. However, if the waiver is not approved, the state has submitted a contingency waiver to renew the current HIP program for another three years. See: “Healthy Indiana Plan,” Healthy Indiana Plan, accessed July 17, 2014, http://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/index.htm; “Governor Pence Unveils HIP 2.0 Plan to Provide Consumer-Driven Health Care Coverage for Uninsured Hoosiers,” Healthy Indiana Plan, accessed July 17, 2014, http://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/files/HIP_2.0_release_5.15.pdf; “HIP 2.0 Proposal,” Healthy Indiana Plan, accessed July 17, 2014, http://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/2442.htm. ↩︎

- See, for example: Florida’s Section 1115 demonstration waiver, Managed Medical Assistance (formerly titled Medicaid Reform): http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/fl/fl-medicaid-reform-ca.pdf; Indiana’s Section 1115 demonstration waiver, Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP): http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/in/in-healthy-indiana-plan-fs.pdf and HIP 2.0 waiver application: http://www.in.gov/fssa/hip/files/HIP_2_0_Waiver_(Final).pdf. ↩︎

- See, for example: Indiana’s Hoosier Healthwise program: http://provider.indianamedicaid.com/provider-specific-information/managed-care.aspx. ↩︎

- See, for example: Genevieve Kenney and Jennifer Pelletier, Medicaid Policy Changes in Idaho under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005: Implementation Issues and Remaining Challenges (Washington, DC: State Health Access Reform Evaluation, June 2010), http://www.shadac.org/files/shadac/publications/IdahoMedicaidDRACaseStudy.pdf; Michael Hendryx et al., Evaluation of Mountain Health Choices: Implementation, Challenges, and Recommendations (Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, August 2009), http://www.rwjf.org/en/research-publications/find-rwjf-research/2009/08/evaluation-of-mountain-health-choices.html. ↩︎

- See, for example: Suzanne Felt-Lisk and Fabrice Smieliauskas, Evaluation of the Local Initiative Rewarding Results Collaborative Demonstrations: Interim Report; The Commonwealth Fund, Feature: Public Programs are Using Incentives to Promote Healthy Behavior, October 2007, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/states-in-action/2007/oct/september-october-2007/feature/public-programs-are-using-incentives-to-promote-healthy-behavior; The Commonwealth Fund, Wisconsin: BadgerCare Plus Healthy Living Update, April 2008, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletters/states-in-action/2008/apr/april-may-2008/snapshots–short-takes-on-promising-programs/wisconsin–badgercare-plus-healthy-living-update. ↩︎

- As of July 1, 2014, Enhanced Benefits Reward$ Program participants are no longer be able to earn new credits for participating in healthy behaviors, however participants may redeem their credits until June 30, 2015. See: Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, Letter to Enhanced Benefits Reward$ Program Participants, July 31, 2013, http://www.fdhc.state.fl.us/medicaid/Enhanced_Benefits/EB_Program_Phase_Out_1st_Notice_07-31-2013.pdf. The MMA program was rolled out between May-August 2014. See: “Managed Medical Assistance,” Agency for Health Care Administration, accessed August 11, 2014, http://www.fdhc.state.fl.us/medicaid/statewide_mc/mmahome.shtml. In the renewed MMA Section 1115 waiver, the state will require managed care plans operating in MMA program counties to establish programs to encourage and reward healthy behaviors. These programs will be administered by the plans, and each plan must have, at a minimum, a medically approved smoking cessation program, a medically directed weight loss program, and a substance abuse treatment plan that meet all state requirements. See: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Letter from Cindy Mann to Justin Senior, July 31, 2014, http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/fl/fl-medicaid-reform-ca.pdf. For more information, see: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid Waivers: Florida Managed Medical Assistance (MMA), accessed August 11, 2014, http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/Waivers_faceted.html. ↩︎

- The enhanced benefit plan was comparable to the traditional Medicaid plan, but covered additional benefits such as weight management and nutritional education services. The basic benefit plan covered fewer services than the traditional Medicaid plan by limiting prescription drugs and not covering benefits such as tobacco cessation, diabetes education, and chiropractic and podiatry services. The Mountain Health Choices program operated under state plan amendments under the Deficit Reduction Act. ↩︎

- Associated Press, “New Rule to End West Virginia’s Medicaid Redesign,” The Register-Herald (May 19, 2010), http://www.register-herald.com/news/state_and__region/article_70fe5794-4176-50f7-a5c8-1d018f6503cc.html; Eric Eyre, “West Virginia Medicaid Redesign Cost State Money,” Charleston Gazette (December 23, 2012), http://www.wvgazette.com/News/201212230095; Doug Trapp, “Federal Rule Drastically Cuts Wellness Program in West Virginia,” American Medical News (November 12, 2010), http://www.amednews.com/article/20101112/government/311129997/8/. ↩︎

- Robert Kane et al., Economic Incentives for Preventive Care (Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, August 2004), http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/ecinc/ecinc.pdf. ↩︎

- See, for example: Pat Redmond, Judith Solomon, and Mark Lin, Can Incentives for Healthy Behavior Improve Health and Hold Down Medicaid Costs?; Jessica Greene, Medicaid Efforts to Incentivize Healthy Behaviors. ↩︎

- See Endnote 11. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See, for example: Kevin Volpp et al., “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation,” special article, New England Journal of Medicine 360, no. 7 (February 2009): 699-709, http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMsa0806819; Kevin Volpp et al., “Financial Incentive-Based Approaches for Weight Loss: A Randomized Trial,” Journal of the American Medical Association 300, no. 22 (December 2008): 2631-2637, http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/300/22/2631.full.pdf+html; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Funding Opportunity Announcement (Washington, DC: CMS, February 2011), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/MIPCD-Funding-Opportunity-Announcement.pdf; Robert Kane et al., “A Structured Review of the Effect of Economic Incentives on Consumers’ Preventive Behavior,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 27, no. 4 (November 2004): 327-352, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.002; Ron Goetsel and Nicolaas Pronk, “Worksite Health Promotion: How Much do we Really Know About What Works?,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 38, no. 2, supplement (February 2010): S223-S225, http://www.ajpm-online.net/article/S0749-3797(09)00754-5/abstract. ↩︎

- Texas received the largest first-year grant award ($2,753,130), while Montana received the smallest first-year grant award ($111,788). At the time of the interim evaluation, RTI did not have the data required to complete an analysis of states’ associated administrative costs, but plans to do so in future analyses. ↩︎

- Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- States are taking different approaches to defining their target populations of Medicaid beneficiaries with or at risk of chronic diseases. For example, some states are focusing on specific age groups, locations, or beneficiaries with particular health characteristics, diagnoses, or risk factors. Some states are focusing on, or running separate programs for, beneficiaries enrolled in managed care organizations (MCOs) and fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid. Other states are focusing on beneficiaries who receive care at specified providers, such as participating community mental health centers. ↩︎

- Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wisconsin changed its initiative from a clinical trial to a quality improvement project; however, it is maintaining its randomized two-group design. ↩︎

- Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation. ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, MIPCD Funding Opportunity Announcement (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, February 23, 2011), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/fact-sheet/MIPCD-Funding-Opportunity-Announcement.pdf. ↩︎

- Kathleen Sebelius, Initial Report to Congress: Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Evaluation. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Public Law 111-148, 111th Congress, Sec. 4108 (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act): http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. ↩︎

- For more information on these waivers, see: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Medicaid Expansion Through Premium Assistance: Arkansas, Iowa, and Pennsylvania’s Proposals Compared (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2014), https://modern.kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-through-premium-assistance-arkansas-and-iowas-section-1115-demonstration-waiver-applications-compared/; Robin Rudowitz, Samantha Artiga, and MaryBeth Musumeci, The ACA and Recent Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, February 2014), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-aca-and-recent-section-1115-medicaid-demonstration-waivers/; Alexandra Gates, Robin Rudowitz, and MaryBeth Musumeci, Medicaid Expansion in Michigan (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, January 2014), https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-expansion-in-michigan/. ↩︎

- See Endnote 15. ↩︎